Abstract

Purpose: Standardised testing tools within an Aboriginal Australian context have been found to produce inaccurate results due to language and cultural differences. The primary aim of the study is to compare Aboriginal children’s scores in urban NSW across two language assessment tools: the Early Language Inventory (ERLI) and the Australian English Communicative Development Inventory, short form (OZI-SF). These tools are vocabulary checklists for children aged approximately 12–30 months. OZI-SF is an Australian tool for mainstream use and ERLI has been developed with and for Aboriginal families, but not in urban contexts, so its suitability there is unknown, given the great cultural and linguistic diversity among Aboriginal people across Australia. The second aim is to identify which tool is more culturally appropriate for urban Aboriginal families through parent perspectives.

Method: Overall, 30 parents (of 31 children) participated in the study to complete the ERLI, and 14 parents from this sample completed both the ERLI and OZI-SF and interviews to explore child scores and parent perspectives, in a mixed methods approach.

Result: Aboriginal children (N = 14) scored higher on the ERLI than the OZI-SF. Gender and age were significant contributors to the scores as scores were higher for older children and higher for girls than boys. In answer to the second aim, four themes emerged to explain parental perspectives and their preference for the ERLI, which supported connection to culture and language.

Conclusion: Findings have implications for paediatric language assessments with urban Aboriginal families in clinical, educational and research settings.

Introduction

The development of language, cognition, intelligence, and academic abilities during childhood may be formally assessed using standardised tests. However, standardised tests can be subject to bias (Cole & Zieky, Citation2001; Nelson-Barber & Trumbull, Citation2007). Cole and Zieky (Citation2001) define bias in relation to standardised tests as differences in the final interpretation of a test score which have arisen through systematic error, and discuss how a lack of “fairness” in test items can underestimate the abilities of children whose backgrounds are different from the dominant culture.

In Australia, a particular minority group that is negatively impacted by the use of standardised tools for language are Aboriginal people. Aboriginal Australian contact languages and Aboriginal ways of speaking English tend to be neglected in assessment processes and tools (Angelo, Citation2013). Additionally, within Australia’s school system there is less support available for Aboriginal children who learn Standard Australian English as an additional language or contact language, in comparison to those from migrant families who learn English as a second language (Dixon & Angelo, Citation2014). There is also typically a lack of acknowledgement of the child’s skills in Aboriginal English or incorporation of these skills into everyday learning within the classroom environment. These differences result in cultural load and inexperience with assessment items and have been implicated in lowering Aboriginal participant scores on standardised assessments, as a standardised assessment requires a certain amount of culture-specific knowledge to perform well on the given test (Djiwandono, Citation2006).

As early as the first years of life, Aboriginal children may be assessed using standardised tools, in clinical assessments and in research. One key developmental area is language, specifically, early vocabulary. An assessment of a young child’s vocabulary development is critical for early intervention, as there is a relationship between early vocabulary knowledge and later academic success and cognitive development (Vagh et al., Citation2009; Short et al., Citation2017). Despite the importance of early intervention, few tools are available which are culturally relevant or adequate to assess Aboriginal children.

Children’s vocabulary development and its measurement

One of the most widely used tools for assessing receptive and expressive vocabulary worldwide is the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (CDI). The CDI is a parental questionnaire originally developed for monolingual American English speaking children to measure early language abilities, and normed through parent reports (Vagh et al., Citation2009; Fenson et al., Citation2000). The CDI assesses expressive and receptive vocabulary, word combinations and gesture use (Law & Roy, Citation2008; Hamilton et al., Citation2000; Fenson et al., Citation2007). It has been adapted to over 60 different languages and cultures, attempting to reflect and cater to linguistic and cultural diversity, in clinical practice and in research (Frota et al., Citation2016).

In assessment of early vocabulary development using the American CDI, Australian children, like UK children, had lower scores compared to American children (Hamilton et al., Citation2000). These results prompted the need for an Australian adaptation of the American CDI, now known as the Australian English Communicative Development Inventory – the OZI (Kalashnikova et al., Citation2016). The OZI is an authorised adaptation of the CDI and is a checklist consisting of 558 vocabulary items. In the norming study for the OZI, Australian children’s scores were higher on the OZI than the American CDI (Kalashnikova et al., Citation2016). There is now an authorised short-form version, the OZI-SF, with 100 vocabulary items (Jones et al., Citation2021).

Despite the adaptations, however, it is not yet known if items on these checklists fairly represent items frequently used in home environments of minority populations. For example, Australia’s diverse population may engage differently in the CDI through the use of the item beach as opposed to items river or dam (Vagh et al., Citation2009). Depending on location and community, some children have never experienced a beach and may lack the linguistic knowledge and experience to know this item on an assessment. For example, Aboriginal Australians living in the Hawkesbury region of Sydney tend to have more experience with Yarramundi River (Nepean Hawkesbury River) than the ocean. Even with the OZI as an Australian adaptation of the CDI, it is unclear how suitable it is for Aboriginal children, given differing worldviews evident across cultures (Goldstein et al., Citation2003) which are inherent in vocabulary.

In an attempt to accurately measure vocabulary development in Aboriginal English, the Early Language Inventory (ERLI – Jones et al., Citation2020) was developed. The ERLI checklist was designed in collaboration with Aboriginal communities and contains words that linguistically reflect varieties of Aboriginal English, Kriol, and traditional languages spoken in the Katherine region of the Northern Territory (NT). The ERLI is also an authorised adaptation of the CDI. As a short-form CDI adaptation, the ERLI contains 120 items and gestures. Some items are recognisable to urban Aboriginal people in Sydney e.g. river, kakka, indicating its possible relevance for urban Aboriginal communities. One of the notable differences between the OZI and the ERLI is the ability to indicate knowledge of an item in a separate column by providing additional word options, which is a feature the OZI does not provide. Typically, administration of the OZI excludes the use of Aboriginal English and Kriol language words, and does not score an item if it is known only in a second or third language, thus only assesses an Aboriginal child’s knowledge of Standard Australian English words (Dixon, Citation2013).

Yet Aboriginal English, creole language varieties like Kriol, and Standard Australian English are all languages. Kriol is linguistically a “contact” language (arising historically from pidgin and creole languages) and today is spoken in many different varieties across northern Australia, from Queensland through to Western Australia. Kriol has similarities to Standard Australian English in its largely English-based lexicon, but also syntactic and semantic differences reflecting the grammar and semantics of traditional Aboriginal languages. Aboriginal English also exists in many different varieties across Australia, ranging from linguistically very different to Standard Australian English through to less obviously different varieties that are often not widely recognised as contact languages at all. Aboriginal English varieties are technically described by linguists as dialects of English (Dixon & Angelo, Citation2014). Popular understandings of the term “dialect”, however, as “inferior” are misleading and create a “blind spot” to Aboriginal English. Despite the linguistic distinctiveness between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities, there is ongoing invisibility of language, more specifically, the lack of recognition of contact languages spoken by Aboriginal communities (Sellwood & Angelo, Citation2013).

Within Aboriginal communities, the typical test language used, i.e. Standard Australian English, is often an obstacle to test success. A case in point is the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) test, which is administered to school years 3, 5, 7, and 9 across Australia. In the report on the 2012 NAPLAN, it was noted: “For the Northern Territory, Standard Australian English is not the first language for many Indigenous students and mean scores are lower in all five achievement domains than are mean scores for students with an English-language background” (ACARA, Citation2012: 71). This is a particularly important comment as it explicitly states that Aboriginal Australian children are scoring lower on standardised tests in all domains than non-Aboriginal Australian children. Angelo (Citation2013) argues that these testing results may not reflect knowledge of the topic being tested, but rather the child’s knowledge of Standard Australian English.

Across Australia, Aboriginal children speak a wide range of languages and dialects. As Butcher (Citation2008) explains, varieties of Aboriginal English can be similar to Standard Australian English, like a slightly different dialect, or considerably different and closer to Aboriginal-English creoles (i.e. English-based creole languages). These variations in language can make assessment of a young child’s vocabulary extremely challenging, especially to a clinician or researcher who is unfamiliar with the local variety of Aboriginal English and with local cultural norms in the Aboriginal community. Therefore, there is an important need for tools that are adequate for Aboriginal children speaking variants of Aboriginal English (Gonzalez & Nelson, Citation2018).

Cultural value is placed on storytelling in Aboriginal families, which highlights possible cultural differences which might make the OZI (and OZI-SF) less suitable for measuring Aboriginal children’s vocabulary. Storytelling promotes the development of expressive and receptive language and creates an environment for rich cultural context (Peck, Citation1989). Because storytelling is strong in Aboriginal Australian culture, the use and development of language is a powerful feature and provides prospects for children to grow as language learners (Peck, Citation1989; Short et al., Citation2017). Morrow (Citation1985) argues that storytelling increases achievement in oral communication and is key in Aboriginal Australian culture. What is the relationship between storytelling and a vocabulary checklist (an inherently Western construct focussed on one domain of language)? To be able to tell a story a child needs a rich vocabulary. If an Aboriginal child receives a low standardised test score, a clinician may wrongly infer that a child lacks a rich vocabulary when this may not actually be the case in the child’s home language(s) (e.g. Aboriginal English, were their home language skills also to be assessed). This perspective highlights the potential mismatch between children’s strengths in culture and home language in relation to an assessment tool like the OZI, which assesses only Standard Australian English skills (Djiwandono, Citation2006) and reflects only mainstream Australian cultural ideas.

The widespread acceptance that standardised tests objectively measure a person’s ability with accuracy, despite diverse backgrounds (Cole & Zieky, Citation2001; Ford & Helms, Citation2012) is a problematic assumption, especially for Aboriginal Australians, as many Aboriginal children in Australia are learning to speak variants of Aboriginal English at home (Butcher, Citation2008). Additionally, there is limited research concerning communication development in Aboriginal communities; therefore, abilities tend to be underestimated as Aboriginal populations Australia-wide are often under-sampled and tests are not normed with them (Ford & Helms, Citation2012).

Research in Aboriginal communities is important as findings can be translated into material effects that are key to reducing biases in standardised testing (Jackson-maldonado, Citation2013). Current practices for language assessment are increasingly relying on test-based tools which fail to acknowledge Aboriginal English and thus disadvantage these populations (Vagh et al., Citation2009; Angelo, Citation2013). Furthermore, these tools have not been normed on Aboriginal populations so there are no benchmarks for performance by Aboriginal children, and the only norms available are for non-Indigenous (and typically higher socioeconomic) populations. For example, Ford and Helms (Citation2012) argue that when using standardised tests on minority groups, such as African Americans, Latinos and Native Americans, their results are always compared to White populations either directly through comparison of tests scores or indirectly through tests scores that are normed. The generation of a separate tool capturing the full capacity of language abilities in Aboriginal communities has the potential to more accurately reflect a child’s language vocabulary scores and reduce biases.

Previous research suggests that in Australia there is a need for speech-language assessment tools that reflect cultural diversity and cultural appropriateness (Vagh et al., Citation2009; Butcher, Citation2008; Hamadani et al., Citation2010; Hamilton et al., Citation2000; Djiwandono, Citation2006; Nijenhuis et al., Citation2016; Short et al., Citation2017). Adaptation of a standardised questionnaire to reflect the cultural and linguistic aspects of Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory has demonstrated positive outcomes for Aboriginal children and been seen as culturally acceptable and relevant to Aboriginal parents (Aprano et al., Citation2016). The Northern Territory context, however, is very different culturally and socially from urban, southern Australian areas like greater Sydney. Sydney was the site of earliest impact of European invasion and colonisation and loss of traditional language. Sydney is also a community with under-recognised cultural and linguistic continuity, and cultural diversity and dynamism, with Aboriginal families from across NSW and Australia living alongside families from local Sydney groups (e.g. Dharug). Appropriate tools are needed for Aboriginal people living in urban areas, especially a tool that can offer benchmarks for what to expect at different child ages.

The present study will help identify whether the ERLI or OZI-SF is more suitable for urban Aboriginal communities and increase understanding about early communication development for Aboriginal children living in greater Sydney. The suitability of ERLI (or OZI-SF) for urban Aboriginal children is as yet unknown, and cannot be assumed, given the great linguistic and cultural diversity among Aboriginal people in urban areas like greater Sydney. The present study seeks information as to how adaptations may need to be made to ERLI to ensure it is suitable to urban (western Sydney) Aboriginal families.

Aim of the study

The research questions in this study are:

RQ1. How do urban Aboriginal children score on the ERLI compared to the OZI-SF?

RQ2. What are parent perspectives on cultural suitability of the ERLI and OZI-SF for the Aboriginal community?

Due to the diversity in Aboriginal communities, there are competing hypotheses.

Hypotheses

Firstly, urban Aboriginal families in greater Sydney generally use Aboriginal English at home. It is anticipated, therefore, that Aboriginal children will score higher on the ERLI than the OZI-SF, as the ERLI contains items which reflect Aboriginal English word variants (including some which, though ERLI was developed in the NT, are recognised and used in western Sydney, e.g. tidda or sis for “sister”). ERLI also encourages children’s knowledge of local equivalents to be reported, for any item. On the other hand, there is diversity among urban Aboriginal children’s home language backgrounds (with some families including non-Indigenous parents, and parents who speak other languages) and diversity in the extent of urban Aboriginal children’s experience with Standard Australian English in other settings, such as early education and care. The relative familiarity of items on the current NT-adaptation of ERLI is unknown for an urban population, prior to this study. This raises at least the possibility that urban Aboriginal children in western Sydney may score higher on the OZI-SF than the ERLI, or not score higher on ERLI than OZI-SF.

Method

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at Western Sydney University (approval H13749). Given the COVID-19 restrictions, an amendment was approved to add audio-recorded verbal consent where written informed consent was difficult to obtain from parents who did not have a home computer. All participants were informed that participation was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time.

Design

This study employed a concurrent triangulation mixed methods approach (Creswell, Citation2009) whereby participants reported children’s vocabulary scores on the ERLI (Jones et al., Citation2020) and OZI-SF (Jones et al., Citation2021) in addition to completing a qualitative semi-structured interview over phone/Zoom. For the quantitative component of the study, the dependent variable was the children’s vocabulary scores on the ERLI and the OZI-SF, and the predictor variables were the checklist tool (ERLI/OZI-SF), child age, and gender. The focus of the qualitative component of this study method was to ask questions that might illuminate which tool was culturally more appropriate for urban Aboriginal communities based on the parent’s or carer’s perspective.

Participants

Convenience sampling was used. Parents/carers (N = 30) were members of a local playgroup or from the primary researcher’s social networks, or contacts through an Aboriginal organisation. Most of the parents/carers were female; one was male. The age ranged from approximately 25 to 75 years old. Children (N = 31) were 11 boys and 20 girls and ranged in age from 8 to 48 months (M = 33, SD = 12). Four of the children’s parents indicated speech-language and/or hearing concerns. Parents reported being from a range of Aboriginal communities, including Gamilaraay, Dharug, and Wiradjuri nura (country). The interviews were logistically facilitated by a local Aboriginal community member (from the playgroup) who interacted with parents and carers of Aboriginal children. Participants identified as Aboriginal or were the primary carer of an Aboriginal child living in western Sydney, including the Blue Mountains. Parents and carers were recruited whose children were aged between eight months and three years. All families indicated that the primary spoken language at home was either Standard Australian English or Aboriginal English. Recruitment of families occurred through the process of collaborating with local Aboriginal community organisations that offered playgroup and early education programs, using email and word of mouth communication.

A total of 30 primary carers participated in this study. Fourteen parents and carers were surveyed about their child’s first words using both the ERLI and OZI-SF tools and these parents were also interviewed to discuss their preferences between the ERLI and OZI-SF and the tools’ cultural relevance to Aboriginal communities. A further sixteen completed only the ERLI. Interviews were carried out with 14 parents/carers (rather than 30), following published guidelines on a sample of this approximate size (Guest et al., Citation2006) and since saturation appeared to have occurred within the first 14 parents/carers.

Materials

Two checklists, the ERLI (Jones et al., Citation2020) and the OZI-SF (Jones et al., Citation2021), were used to assess each Aboriginal child’s vocabulary. The ERLI tool offers, for each item, translation equivalents in Standard Australian English and Aboriginal English, north Australian Kriol, and the space for a parent/carer to write in traditional Aboriginal language words (or words from any other language the child has at home) under optional sections “what do you say at home?” and “what language is that?” This allows for multilingualism and diversity. Aboriginal families in western Sydney are from a great many Indigenous nations of Australia. Although parents/carers in western Sydney are more likely to have a variety of Aboriginal English at home than a variety of Kriol, both languages are English-based contact languages and share some words (e.g. kakka). In recognition of this linguistic overlap between Aboriginal English and Kriol, and the diversity of families in western Sydney, the Kriol equivalents column was left in, in case it was useful to parents/carers. Standard Australian English equivalents were also accepted on the OZI-SF; for example if the child used the word jacket instead of coat the child still received credit for that item. No children were excluded from the study. In addition to measuring communication, the checklists provided information about participant demographics regarding parent education, children’s pre-school participation, language background, history of ear infections, and any concerns regarding the child’s hearing and/or speech.

Qualitative interviews occurred immediately after the checklists were completed. The interviews were semi-structured to gather information from the parent or carer on their views regarding cultural appropriateness of each checklist (see Supplementary material for semi-structured interview schedule). This information was obtained through a number of interview questions that explored the experience the child had with each item in the home environment to investigate the cultural applicability of each tool. For example, “was there a preference for either checklist?” and “Which checklist do you think is better for Aboriginal communities?”

Procedure

All participants received information forms prior to study commencement. Interviews were adapted from face-to-face interviews to phone and zoom video calls due to COVID-19 restrictions. Interviews were delivered adaptively in Standard Australian English and Aboriginal ways of speaking English depending on whether the parent/carer being interviewed was the Aboriginal parent (several parents had a non-Aboriginal partner) as the primary researcher was an Aboriginal woman from western Sydney. The style of interviewing was similar to that described for the methodology of yarning or clinical yarning (Lewis et al., Citation2019) in that informal, responsive, reciprocal conversations facilitated deep and safe connections with Aboriginal parents who freely shared their views and knowledge. Together the ERLI and the OZI-SF took a total of 25–45 minutes to complete, as a conversation. If interviews occurred over the phone, images of the tools were sent via text just prior to the interview to familiarise the parent with the words on the checklists, and during Zoom, screenshares took place. During the interviews the researcher and parent went through the checklist items one-by-one and the child received credit if it was indicated that they used and/or understood the item, in any language(s). Parents also engaged in informal conversation with the researcher as they completed the checklist tools (except for a small number who had completed the checklists prior to interview). Once the checklists were complete the researcher engaged in further conversation (semi-structured interview) with the parent about their perspectives on each checklist. All interviews were completed by the primary investigator who was familiar with the ERLI and OZI-SF checklists and experienced in interaction with parents of young Aboriginal children.

Different strategies were employed to cater for those that had restricted time to attend an interview and alternate methods were used when necessary, as when for example the tools were sent via email with instructions on how to complete each checklist. In such cases, once the checklists were completed, the interviewee received a phone call to discuss their perceptions for the qualitative aspects of the mixed-methods design. All interviews reflecting the qualitative components occurred within the playgroup setting, over the phone or via Zoom meetings.

Qualitative interviews were recorded and transcribed, with participants’ consent, and transcripts were examined using inductive thematic analysis. Through the six stages identified by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), repetitions and similarities were sought to identify themes. The first step was familiarisation and noting any initial analytic observations in the transcripts. Next, coding commenced by labelling important elements within the data. Codes included: Resonate, culturally appropriate, and separation between cultures/languages. Third, the transcripts were analysed for any significant patterns to generate themes, such as “speaking black or speaking white”. Step four involved re-evaluating the current themes to confirm each theme suited the context. Finally, after reviewing data and potential themes, there were four themes under the overarching theme of “vocabulary development and cultural identity” to identify the overall reasons for participant checklist preference. All participants have received pseudonyms to de-identify.

Result

Quantitative results

Comparison of children’s ERLI and OZI-SF scores

For the 14 children whose parent/carer completed both checklists (ERLI, OZI-SF), a paired samples t-test was conducted to compare scores. As the two tools differed in total number of words (total OZI-SF = 100; total ERLI = 120) each child’s raw scores were first converted into a percentage before statistical analysis.

Data screening was conducted using R (https://www.r-project.org/) to check for normality. Assumptions were met using the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality (Happ et al., Citation2018; Zimmerman, Citation2003). Results indicated there was a normal distribution (W = .970, p = 0.875). There were no outliers.

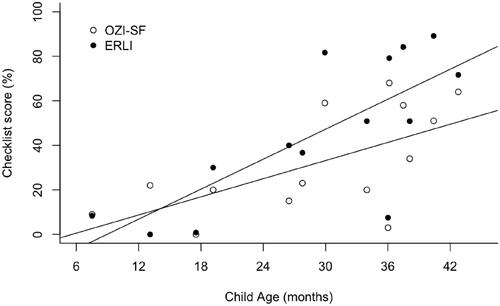

The mean ERLI score (M = 45.1, SD = 32.6, N = 14) was significantly higher than the mean OZI-SF score (M = 31.9, SD = 23.6, N = 14), t(13) = −3.225, p = 0.007. The effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.86) was evident in the mean difference of −13.2, 95% CI [−22.1, −4.4]. is a scatterplot which plots two checklist percentage scores for each child, and the linear relationship between age and scores for OZI-SF (open circles) and ERLI (filled circles). The steeper line relates to the ERLI scores. shows that for most children scores on the ERLI were higher than scores on the OZI-SF, and also illustrates in this cross-sectional study the scores that were reported, by child age. As seen in , urban Aboriginal children generally started to display ceiling effects on ERLI at the oldest ages; children used about 110 items (out of 120) by age 2;6 to 3 years.

Correlation between children’s scores on ERLI and OZI-SF

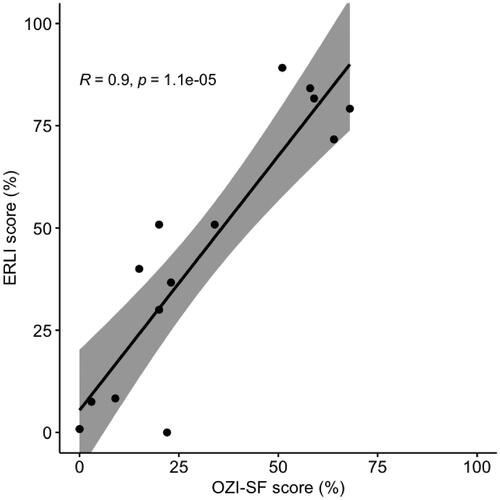

A Pearson’s product-moment correlation was run to assess the relationship between children’s scores on the ERLI and OZI-SF using an alpha level of 0.05. As shown in , scores on the ERLI and the OZI-SF were significantly strongly correlated, r(12) = 0.90, N = 14, p < 0.001. A partial correlation was conducted to control for Age; this also yielded a statistically significant correlation r(11) = 0.83, N = 14, p < 0.001.

The relationship between ERLI scores and child age and gender

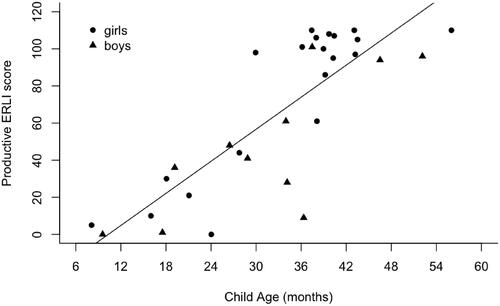

For this analysis, the dataset involved 30 children, by parent report from the 14 parents who had completed both the ERLI and OZI-SF plus the 16 parents who had just completed the ERLI.) A multiple regression was performed to analyse the relationships between child age, child gender and productive vocabulary scores, R = 0.733, R2 adjusted = 0.714, F(2, 28) = 38.61, p < .001, indicating that age and gender together explain 71% of the variance in ERLI scores. The results indicated that age (t(28) = 8.09, p < .001), and gender (t(28) = −2.46, p = 0.0204) are significant contributors to productive vocabulary scores ().

Qualitative results

Speaking black or speaking white?

Participants discussed the preferred checklist and the reasons for their choices. All participants openly expressed which checklist had words that they were more likely to use at home. Responses varied from Minjarra

“I think they are pretty even”,

to Yarran

“I think more words stood out on the Aboriginal one, that I, that my kid, was able to recognize”.

Participants also reported that there was a distinction between talking in an Aboriginal way and talking in a Standard Australian English way, Minjarra

“because we have a different way of speaking and my kid can actually distinguish when to use what language”,

Birrani further confirms recognition of the difference and states

“yeah a lot of the pidgin words, ‘cos where I grew up and how I grew up and how I spoke is very much on that side of things”,

And Killara,

“I had to think more about the Australian one [OZI-SF], the words that were used and the words that I use at home, because and when you’re thinking about it, it’s totally different when you’re saying it to your little one, it’s just natural to be saying those words ‘cos you’re brought up with them”.

Minjarra provides an in depth look into how these differences are thought of when they are explicitly faced:

“in the English one, I mean, like, I guess for me I shook my head at those words, like I mentally shook my head at those words, like um, are you for real, who uses some of those words in a black house”.

Minjarra then follows up with,

“words that, yeah I think it’s just that words are much more familiar to what would be spoken in a First Nation house even in one that doesn’t speak language still has pidgin language that’s spoken.”

These extracts highlight the idea that participants are aware that they speak differently at home with their children. The specific choice of words selected by the participants identifies the reasons behind the preferred tool.

Shades of meaning

Important elements that demonstrate the reasons why a tool is preferred, as well as the nuances associated with this choice, are expressed through the extracts by Minjarra, Waru, and Jandamarra. Subtle differences are discussed with the word choices on each tool, as by Minjarra

“the Kriol, with those words, bird, birdie, birdibirdi, it allows for progression” and Waru “the first one [ERLI] because they have more options in how they sound out a word”,

“in our household definitely, so I mean I think at the moment ‘cos he is still so young, like, we are not saying things like mop, comb, oven, ummmm pudding, like we don’t even use that word, I thought that was a European word?”

Killara,

“And becoming a mum, because there just words that we used when we were little. When we were children all the time and not even realising now that we are using them with our children and that they are words that we used as kids”.

Not white not right

Here there are two major aspects that are entwined. The first is the way one feels when people use Aboriginal ways of speaking English within and outside the Aboriginal community. As is reflected in the quotes it is interpreted that there is a sense of a dominant white culture in an Australian context.

Ngarra states,

“yep my kid she’s the two year old, I do the same, like yeah, I ummm like I said I just go on the words they use and what my daughter and that use at home, you know ‘cos I don’t wanna teach them a bad word, you know what I mean!”.

Ngarra’s comment shows that if individuals in Australia do not conform to one way of speaking then it is considered “bad” (by some Aboriginal parents). This is reflected through Ngarra’s statement that she changes the way she talks as she identifies her way of talking might teach the children “bad words”. Again, Waru reinforces that this is a common feeling amongst Aboriginal people as she describes

“people mock the way I talk and I’m like “shuddap, I’ll talk the way I want” and “I think they were more dominant towards the English way of speaking”.

These extracts identify that using Aboriginal English word choices does not conform to the societal expectations for Standard Australian English. The second feature allows the participants to express their thoughts on maintaining cultural identity while also voicing which tool is culturally appropriate for the Aboriginal community. For instance,

Jandamarra

“[ERLI] because of the options, the word options and even just the different ways of the English words and also options of the Kriol words”.

Birrani states,

“the first checklist [ERLI] ‘cos you wanna keep the culture, you wanna keep things that date back, you don’t wanna change things and they become forgotten and I think that is a big key, especially within Indigenous communities now is not losing these essential parts of the culture”.

Participants indicate that having connection to culture through language is an important part of Aboriginal identity.

Birrani

“yes, that we want to find out more about our history because it’s like, because your background is who you are, and it’s a big part of who you are going to become, and it’s a big part of your identity”.

Jarra and and Yindi confirm how important language is in maintaining culture,

Jarra

“there is a few on there, that’s why I didn’t mark most of them down ‘cos I have trouble with ummm, so I am slowly getting into learning a bit more language so my son can learn it”.

Yindi

“and I feel that they need to learn those things because once the Elders kind of you know, they start getting older and passing away and stuff, these children aren’t going to know nothing”.

Fear of discrimination because we talk different

The final theme focusses on reports regarding participants’ thoughts about having a fear of being discriminated against if they do not talk to the ideas of what “normalises” societies. This notion is explicitly stated through Killara when responding to a question about the way her children speak,

“I don’t want them to be discriminated against, I want them to have a connection to their people, but I also want them to be in a society without being discriminated against”.

Killara further illustrates that her fear of discrimination runs deep as she then justifies her previous comment by expanding with the following:

“but I do I think that it’s good to be learning both because I don’t want them to be different but I don’t want them to be less attached to their own people, I want them to learn their language but I also want them to be in… able to speak um Australian as well so that they… what’s the word for it when their umm cohesive with everybody”.

Discussion

The current study focussed on exploration of vocabulary scores of Aboriginal children in urban NSW as determined by parent report on the ERLI and OZI-SF. The primary aim was to identify which checklist is more suitable to Aboriginal communities. The answer was sought through the children’s quantitative scores and parent/carer perspectives on each checklist via qualitative interviews. The implications of this study have the potential to either support the need for the ERLI as a culturally relevant tool or to indicate that the current standardised tool, OZI-SF, is sufficient for Aboriginal communities.

Results support the argument for the need for a culturally appropriate tool. Results supported the hypothesis that Aboriginal children scored higher on the ERLI than they did on the OZI-SF. This finding is consistent with previous research by Dixon (Citation2013) and Wigglesworth and Billington (Citation2013) demonstrating that Aboriginal children tend to score lower on standardised tests that are currently designed and normed for mainstream populations, such as the OZI-SF (Angelo, Citation2013; Dixon, Citation2013).

The second (competing) hypothesis that Aboriginal children will perform better on the OZI-SF than the ERLI was not supported. There may be several reasons for this finding, but it is suggested that perhaps this result underscores the error in assuming that a mainstream tool will be a suitable fit for urban Aboriginal populations that may appear “mainstream” in many aspects of life (e.g. as when adults code-switch to use Standard Australian English at work) but who use Aboriginal English at home, including some words from heritage languages (e.g. languages of greater Sydney and New South Wales such as Dharug, Gamilaraay, and Wiradjuri). This speaks to the concept of invisibility of Aboriginal languages, particularly Aboriginal English, as current assessment tools typically do not recognise or allow for Aboriginal English variants within the instrument. Through the qualitative interviews the suggestion of invisibility also exists as dominant discourses marginalise the way Aboriginal people feel when speaking Aboriginal English.

The concern that the words on the ERLI may not be transferable to urban families, was explored with care. Parents indicated, indirectly through child vocabulary scores, that many words were recognised by many of the urban families. This result is consistent with the observation that within the vocabulary of Aboriginal English there seems to be a noticeable sharing of linguistic material between NT and NSW, some of which relates to the historical development of contact languages in Australia (O'Shannessy & Meakins, Citation2016). In the qualitative interviews parents also explicitly indicated that many words on the ERLI tool resonate with them.

Findings further support previous literature exploring standardised testing through formal assessment processes and the lack of cultural sensitivity. Previous studies identified that children from culturally and linguistically diverse populations scored lower on standardised tests (Angelo, Citation2013; Dixon & Angelo, Citation2014; Hamilton et al., Citation2000; Siegel, Citation2007). This is also mirrored in parents’ comments regarding dominant ways of speaking and a fear of discrimination for using Aboriginal English variants. Despite the attempts that parents note to change the way of speaking from a fear of using a “bad” word, however, parents still continue to teach their children the same word variants. These extracts demonstrate the conflict the participants hold when engaging in tasks, such as speaking a specific way to their own children in Aboriginal ways of speaking English. Therefore, this further illustrates the need for a culturally appropriate tool to keep cultural connection safe while maintaining cultural identity and connection to country through language. These extracts also illuminate how the parent’s speech influences the child’s home vocabulary development. Through this process speech patterns that involve Aboriginal ways of speaking English are consolidated until the child learns to code switch. Learning to code-switch between Aboriginal English and Standard Australian English takes time developmentally and is dependent on the child’s social and educational experiences (e.g. home language varieties of the family, and the child’s participation in pre-school and school). This perspective is indirectly confirmed as the results showed that these Aboriginal children, aged up to 3 years, performed better on the ERLI than the OZI-SF.

Participants also discussed the concerns of speaking in a “standard white way” in the themes of Not white not right and fear of discrimination because of talking different. Aboriginal families speaking variants of Aboriginal English have expressed concerns about potential discrimination if their children do not speak Standard Australian English. Fear of discrimination reflects dominant discourses creating disempowerment for Aboriginal people (Dobusch, Citation2017).

Urban Aboriginal children generally started to display ceiling effects on ERLI at the oldest ages; children used about 110 items (out of 120) by age 2;6 to 3 years. On closer inspection, the 10 items that were left unticked differed between families. It was not the case that there was a clear list of items that might be inappropriate for urban Aboriginal families in western Sydney. Even though ERLI was developed in the Northern Territory, parents reported local Sydney or NSW equivalents on several items, such as (b)rrrrrrrrrrr, instead of wuduwudu or nguyunguyu to put a child to sleep. In the same way, parents reported using gestures (handsigns) for items originally developed in the NT context including come here (52% of parents), what (38%), and sha/shoo (66%). If NSW equivalents for these words and gestures had been supplied on the ERLI form, in recognition format, it seems likely that more parents would have ticked these items, as they are in common use in the community (according to the first author). Adjustments to the ERLI checklist, to provide more local (Sydney, NSW) equivalents for words and gestures on the ERLI checklist, are planned for implementation and further research in the near future.

While we still lack norms to better understand vocabulary development specifically among Aboriginal communities in urban regions, the findings of the current study suggest developmental patterns worthy of future research. There appear to be gender differences in vocabulary measures (as seen in ) in that girls scored slightly higher than boys at equivalent ages. These findings add to the literature as they provide evidence that there may also be gender effects in communication development among Australian Aboriginal children. This would be consistent with findings for Australian children in general, from the OZI and OZI-SF norming study (Jones et al., Citation2021; Kalashnikova et al., Citation2016), where girls were observed to have slightly vocabulary higher scores than boys, at younger ages.

Overall, the quantitative results and qualitative themes emerging in this study reflect the way the parents feel about cultural applicability of each tool. The qualitative interviews complement the quantitative findings of this integrated mixed methods approach, as the reasons behind child scores and parent preferences were explained. Together, these approaches found that, overall, children scored better on the ERLI and that parents had a more positive experience completing the ERLI checklist, as parents were able to identify with words they use at home.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the small sample size in the quantitative component. A second limitation was due to the pandemic situation of COVID-19, when parents completed the written checklist before having the interview in some cases. When this happened, Aboriginal ways of speaking English were not always reflected in the responses. A potential reason for this is parents’ differing experience with written forms of Aboriginal English. Parents who completed the checklists via email (Jandamarra) had noted they did not understand how to read some of the words until it was pronounced over the phone. This challenge already had an impact on word selection as when completing the ERLI parents did not circle a small amount of the Kriol word options, despite this limitation, when discussed with parents, a majority indicated verbally that they “knew the Kriol word option” (reflected in the above extracts) and were just unable to read the different utterances. These experiences highlight the importance of administering the ERLI verbally, within a conversation between professional and parent, and not just asking the parent to complete the written form. For clinical use, this suggests a useful development the ERLI team may consider is an audiovisual app version of the tool, to circumvent the problem of unfamiliar spellings of contact language words (in Kriol and Aboriginal English varieties).

Another possible limitation to this study is the concept of “insider” (Dew, McEntyre, & Vaughan, Citation2019). The first author is an Aboriginal woman from the Dharug community in western Sydney. Having shared lived experiences with the participants there was a mutual understanding of the participants’ perspectives, which initially impacted on the extraction of information for “outsiders” in the qualitative interviews. On the other hand, the first author’s identity as a local Aboriginal person had many advantages such as contacts with local Aboriginal population, Elders and community organisations, and the current research project being from the perspective and interpretation of an Aboriginal person, and ultimately, successfully inviting participant experiences in a “safe” way.

Quantitative and qualitative findings suggest the ERLI can be an appropriate tool for urban Aboriginal families. Future research with a larger dataset would be of value to produce norms for urban Aboriginal communities and benefit clinical settings (for example, local Aboriginal medical services).

Conclusion

This study expands on current literature as the majority of research involving Aboriginal Australian peoples has not investigated children’s vocabulary production. In relation to Closing the Gap in health, there is an important need for an assessment tool that is adequate for urban Aboriginal families who speak Aboriginal English at home, and which can track developmental progression. The present study yields promising data as it suggests the ERLI has the potential to be an effective method of vocabulary assessment in young Aboriginal children in urban regions of NSW, with minor modifications to offer local equivalents for some items. The study also indicates that, as long as the written items are discussed in a conversation, the ERLI is a practical tool for collaborating with urban Aboriginal parents in NSW, as it includes familiar items from Aboriginal English, and has a clear straightforward parent-report format.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the families who participated in the research, as well as the Merana Aboriginal Community Association for the Hawkesbury Inc. This research received ethics approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Western Sydney University (approval number H13749).

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2045357.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Angelo, D. (2013). Identification and assessment contexts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander learners of standard Australian English: Challenges for the language testing community. Papers in Language Testing and Assessment, 2, 67–102. Retrieved from http://www.researchgate.net/publication/274393074

- Aprano, A.D., Silburn, S., Johnston, V., Robinson, G., Oberklaid, F., & Squires, J. (2016). Adaptation of the ages and stages questionnaire for remote Aboriginal Australia. Qualitative Health Research, 26, 613–625. doi:10.1177/1049732314562891

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) (2012). 2012 National assessment program literacy and numeracy. Achievement in reading, persuasive writing, language conventions and numeracy. National Report.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Butcher, A. (2008). Linguistic aspects of Australian Aboriginal English. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 22, 625–642. doi:10.1080/02699200802223535

- Cole, N.S., & Zieky, M.J. (2001). The new faces of fairness. Journal of Educational Measurement, 38, 369–382. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3984.2001.tb01132.x

- Creswell, J.W. (2009). The research Design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). California: Sage Publications.

- Dew, A., McEntyre, E., & Vaughan, P. (2019). Taking the research journey together: The insider and outsider experiences of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal researchers. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 20, 1–17. doi:10.17169/fqs-20.1.3156

- Dixon, S., & Angelo, D. (2014). Dodgy data, language invisibility and the implications for social inclusion: A critical analysis of Indigenous student language data. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 213–233. doi:10.1075/aral.37.3.02dix

- Dixon, S. (2013). Educational failure or success: Aboriginal children's non-standard English utterances. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 302–315. doi:10.1075/aral.36.3.05dix

- Djiwandono, P.I. (2006). Cultural bias in language testing. TEFLIN Journal, 17, 81–89. doi:10.15639/teflinjournal.v17i1/85-93

- Dobusch, L. (2017). Diversity discourses and the articulation of discrimination: The case of public organisations. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43, 1644–1661. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1293590

- Fenson, L., Marchman, V.A., Thal, D.J., Dale, P.S., Reznick, J.S., & Bates, E. (2007). MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventories: User’s guide and technical manual (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Brookes Publishing.

- Fenson, L., Pethick, S., Renda, C., Cox, J.L., Dale, P.S., & Reznick, J.S. (2000). Short-form versions of the MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventories. Applied Psycholinguistics, 21, 95–115. doi:10.1017/S0142716400001053

- Ford, D.Y., & Helms, J.E. (2012). Overview and introduction: testing and assessing African Americans: “unbiased” tests are still unfair assessing African Americans: Past, present, and future problems and promises. Journal of Negro Education, 81, 186–189. doi:10.7709/jnegroeducation.81.3.0186

- Frota, S., Butler, J., Correia, S., Severino, C., Vicente, S., & Vigário, M. (2016). Infant communicative development assessed with the European Portuguese MacArthur–Bates communicative development inventories short forms. First Language, 36, 525–545. doi:10.1177/0142723716648867

- Goldstein, M.H., King, A.P., & West, J.M. (2003). Social interaction shapes babbling: Testing parallels between birdsong and speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100, 8030–8035. doi:10.1073/pnas.1332441100

- Gonzalez, S.L., & Nelson, E.L. (2018). Behavioral sciences measuring Spanish comprehension in infants from mixed Hispanic communities using the IDHC: A preliminary study on 16-month-olds. Behavioral Sciences, 8, 117–113. doi:10.3390/bs8120117

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and validity. Field Methods, 18, 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Hamadani, J.D., Baker-Henningham, H., Tofail, F., Mehrin, F., Huda, S.N., & Grantham-McGregor, S.M. (2010). Validity and reliability of mothers’ reports of language development in 1-year-old children in a large-scale survey in Bangladesh. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 31, S198–S206. doi:10.1177/15648265100312S212

- Hamilton, A., Plunkett, K., & Schafer, G. (2000). Infant vocabulary development assessed with a British communicative development inventory: Lower scores in the UK than the USA. Journal of Child Language, 27, 689–705. doi:10.1017/S0305000900004414

- Happ, M., Bathke, A.C., & Brunner, E. (2018). Optimal sample size planning for the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney-Test. Austrian Science Fund, 1, 1–20. doi:10.1002/sim.7983

- Jackson-Maldonado, D., Marchman, A.M., & Fernald, L.C.H. (2013). Short-form versions of the Spanish MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventories. Journal of Applied Psycholinguistics, 34, 837–868. doi:10.1017/S0142716412000045

- Jones, C., Collyer, E., Fejo, J., Khamchuang, C., Rosas, L., Mattock, K., … Dwyer, A. (2020). Developing a parent vocabulary checklist for young Indigenous children growing up multilingual in the Katherine region of Australia's Northern Territory. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22, 583–590. doi:10.1080/17549507.2020.1718209

- Jones, C., Kalashnikova, M., Khamchuang, C., Best, C.T., Bowcock, E., Dwyer, A., … Short, K. (2021). A short-form version of the Australian English communicative development inventory. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 6, 1–11. doi:10.1080/17549507.2021.1981446

- Kalashnikova, M., Schwarz, I.C., & Burnham, D. (2016). OZI: Australian English communicative development inventory. First Language, 36, 407–427. doi:10.1177/0142723716648846

- Law, J., & Roy, P. (2008). Parental report of infant language skills: A review of the development and application of the communicative development inventories. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13, 198–206. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00503.x

- Lewis, T., Hill, A.E., Bond, C., & Nelson, A. (2019). Yarning: Assessing propa ways. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 19, 14–18.

- Morrow, L.M. (1985). Retelling stories: A strategy for improving young children's comprehension, concept of story structure, and oral language complexity. The Elementary School Journal, 85, 647–661. doi:10.1086/461427

- Nelson-Barber, S., & Trumbull, E. (2007). Making assessment practices valid for indigenous American students. Journal of American Indian Education, 46, 132–147. doi: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ794264

- Nijenhuis, T.J., Willigers, D., Dragt, J., & Van Der Flier, H. (2016). The effects of language bias and cultural bias estimated using the method of correlated vectors on a large database of IQ comparisons between native Dutch and ethnic minority immigrants from non-western countries. Intelligence, 54, 117–135. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2015.12.003

- O'Shannessy, C., & Meakins, F. (2016). Australian language contact in historical and synchronic perspective. In O'Shannessy, C., & Meakins, F. (Eds.), Loss and renewal: Australian languages since colonisation: (pp. 3–26). Berlin, Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Peck, J. (1989). Using Storytelling to promote language and literacy development. The Reading Teacher, 43, 138–141. doi: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20200308

- Sellwood, J., & Angelo, D. (2013). Everywhere and nowhere: Invisibility of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contact languages in education and Indigenous language contexts. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 250–266. doi:10.1075/aral.36.3.02sel

- Short, K., Eadie, P., Descallar, J., Comino, E., & Kemp, L. (2017). Longitudinal vocabulary development in Australian urban Aboriginal children: Protective and risk factors. Child Care Health Development, 43, 906–917. doi:10.1111/cch.12492

- Siegel, J. (2007). Creoles and minority dialects in education: An update. Language and Education, 21, 66–86. doi:10.2167/le569.0

- Vagh, S.B., Pan, B.A., & Mancilla-Martinez, J. (2009). Measuring growth in bilingual and monolingual children's English productive vocabulary development: The utility of combining parent and teacher report. Journal of Child Development, 80, 1545–1563. doi: 137.154.19.149 doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01350.x

- Wigglesworth, G., & Billington, R. (2013). Teaching creole-speaking children: Issues, concerns and resolutions for the classroom. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 234–249. doi:10.1075/aral.36.3.01.wig

- Zimmerman, D.W. (2003). A warning about the large-sample Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Understanding Statistics, 2, 267–280. doi:10.1207/S15328031US0204_03