Abstract

Purpose: Yolŋu (First Nations Australians from North-East Arnhem Land, Northern Territory) and Balanda (non-Indigenous people) often encounter communication challenges at a cultural interface during the provision of health and education services. To address these challenges, our project co-created an educational process and resources to inform and facilitate intercultural communication. During interactive workshops, participants and researchers from different cultural backgrounds reflected on their communication practice together in small groups. Reflection and discussion during the workshops were supported by multi-media resources designed to be accessible and resonant for both Yolŋu and Balanda partners. Participants explored and implemented strategies during intercultural engagement within and beyond the workshop. In this article we explain our processes of co-creating intercultural communication education and share features of our educational process and resources that resonated with participants from both cultural groups.

Method: Our intercultural team of researchers used a culturally-responsive approach to Participatory Action Research (PAR) to co-create an intercultural communication workshop and multi-media resources collaboratively with 52 Yolŋu and Balanda end-users.

Result: Collaborating (the power and value of genuine collaboration and engagement throughout the process) and connecting (the meeting and valuing of multiple knowledges, languages and modes of expression) were key elements of both our methods and findings. Our processes co-created accessible, inclusive, collaborative spaces in which researchers and participants were actively supported to implement intercultural communication processes as they learned about them.

Conclusion: Our work may have relevance for others who are developing educational processes and resources for facilitating intercultural communication in ways that honour participants’ voices, challenge inaccessible systems, resonate with diverse audiences and create opportunities for research translation.

• Yolŋu are First Nations Australians from North-East Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia.

• Balanda is a term used by speakers of Yolŋu languages to refer to non-Indigenous people.

• First Nations Australians is used to include diverse Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. This term recognises the identities of First Nations peoples who hold unceded sovereignty over their lands and waters.

• The pronouns we, us and our are used to refer to the intercultural research team who are also authors (i.e. Emily, Gapany, Ḻäwurrpa, Yuŋgirrŋa and supervisors Anne, Lyn and Sarah). When sharing other people’s perspectives, or the voices of individual researchers, the text will specify whose voice is being shared.

Explanation of terms

Introduction

Intercultural communication happens when people from different cultural groups engage in interactions to co-construct meaning together (UNESCO, Citation2013). Intercultural communication is more than a two-way exchange between people, knowledge systems, cultures or languages. Instead, it is a dynamic and interactive process that people navigate in partnership together and that partners can only be competent in if they are competent together (UNESCO, Citation2013). Therefore, all partners’ perspectives need to be explored collaboratively when studying intercultural communication processes.

The purpose of our project was to collaboratively design an educational process and resources to inform and facilitate intercultural communication between Yolŋu (First Nations Australians from North-East Arnhem Land) and Balanda (non-Indigenous people). We understand intercultural communication as happening in a space called the cultural interface: a complex “multi-layered and multi-dimensional space of dynamic relations” (Nakata, Citation2007, p. 323). First Nations peoples in colonised Australia have everyday experiences of thinking and living in this space of many intersections, contradictions, ambiguities, possibilities, constraints, collaborative practices and contested meanings (Nakata, Citation2007).

In the community where we conducted this project, Yolŋu and Balanda often meet and communicate at a cultural interface during the provision of health and education services. First Nations Australians experience inequities in availability, accessibility and outcomes of health and education services; addressing and resolving these inequities requires engagement in genuine partnerships, collaborative action, recognition of First Nations Australian expertise and control, repositioning of power relationships, and development of intercultural communication skills (Kral, Fasoli, Smith, Meek, & Phair, Citation2021; Lowell, Citation2013; Osborne & Guenther, Citation2013; Staley et al., Citation2020).

It is well documented that a foundation of strong intercultural communication capabilities, at both personal and systemic levels, is required for provision of culturally responsive, equitable and high quality services (Lowell, Schmitt, Ah Chin, & Connors, Citation2014; Perso, Citation2012). However, less is known about how communication can be facilitated at the cultural interface in ways that are meaningful and useful for both Yolŋu and Balanda partners. This is what our project explored using two phases of collaborative research.

In Phase 1 of our research (Armstrong et al., Citationsubmitted), we explored intercultural communication at a cultural interface: interactions between Yolŋu families, Balanda staff and Yolŋu staff during early childhood assessment processes (including health, allied health, education and family support contexts). We connected Phase 1 research findings about intercultural communication processes to a place-based, Yolŋu metaphor (Armstrong et al., Citation2021; Armstrong et al., Citationsubmitted). In this metaphor, fresh and salt water meet like people from two different cultures communicating and our team use the water’s flow and currents to represent and explore intercultural communication processes.

This article focusses on Phase 2 of our project during which we used this water metaphor to share and build on our Phase 1 findings. We did this by co-creating intercultural communication education with Yolŋu and Balanda members of the participating community. The educational process we co-created consists of interactive workshops for reflection and discussion in small groups, prompted and supported by multi-media resources. In this article we will share features of this collaborative educational process which may be useful as people explore ways of connecting in their own intercultural contexts.

Our educational process engages participants in reflection as a way to deepen their understanding, develop skills and make changes to their intercultural communication in the present (during workshops) and in the future (in their practice). A systematic review of reflective practice in speech-language pathology literature (Caty, Kinsella, & Doyle, Citation2015) suggested the consideration of diverse modalities (e.g. group discussion, audio recordings, photographs, video, art works) to prompt discussion and support reflective activities. Our Phase 2 study explored the resonance of various modalities for supporting reflective practice of intercultural communication.

This article is like a parcel we are passing to you so you can learn more about ways of sharing research findings that are accessible, resonant and useful for communicators from different cultural backgrounds. We have prepared this parcel slowly and carefully together. We ask that you unwrap it slowly and carefully and preferably with someone else so you can discuss it together. Inside each layer is something for you to connect to. Every picture, every word, every story carries a message. As you open it up, and connect to each layer, you will see more clearly the story of our work coming from the inner layer deep inside that we call ḏandjaŋur and djinawaŋur. And that’s what we call bulay (treasure) or mulwaṯ (belongings) – something precious that we have considered and checked carefully with Yolŋu knowledge holders before sharing.

We want to communicate in an accessible and inclusive way so more people in the community where we work will be able to understand our research using different modalities and non-dominant languages (Booth, Armstrong, Taylor, & Hersh, Citation2019). Many readers will be familiar with the concept of “nothing about us without us” (Charlton, Citation1998; Pearson, Citation2015) which emphasises the rights of people who experience marginalisation or oppression to have control over their own voices and for those voices to be listened to, respected and acted upon. We applied this principle in co-creating intercultural communication education, aiming to “maintain (participant) relatedness to the work” (Martin/Mirraboopa, Citation2003, p. 213).

Through collaborative development of this article, we addressed the challenge of finding ways of communicating about intercultural research that are “culturally appropriate, useful and informative” (AIATSIS, Citation2020, p. 23); linguistically and technologically accessible; share deep and complex concepts; resonate with diverse intercultural audiences; and have the potential to facilitate change. We recognise the tensions in writing about intercultural research (Fisher et al., Citation2015) and we endeavour to navigate them responsibly together as an intercultural team. We have used a multi-voiced way of writing that represents our collaborative research processes (Cahill & Torre, Citation2007). This reflects our intention to go beyond inclusion of Yolŋu participants and researchers as advisors and consultants (Nakata, Citation2007) and to instead work as a team throughout all phases of research including analysis, theorising and publishing. We have written using words that we use to talk about our research so that the findings are accessible to more of the people who contributed to this project.

In this article we explain our process of collaborative resource creation and share the ways in which our educational process and resources resonated with Yolŋu and Balanda participants (Phase 2). We hope this article facilitates and enacts intercultural communication through our writing and through your reading. We want our communication to be inclusive and creative in how it challenges us all with different ways of thinking. We want our resources to guide all of us with strategies for connecting with each other.

Research setting

We conducted this research in Galiwin’ku – a remote Yolŋu community with a population of over 2200 people (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], Citation2016). Galiwin’ku is on an island in the Arafura Sea, 520 km from Darwin and accessible by aeroplane or boat. Some researchers live full-time on the island and others visited to work together on the project (for 2−8 weeks at a time over 4 years, with Northern Land Council research permits).

In Galiwin’ku, 94% of the population are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people (ABS, Citation2016). Yolŋu cultural knowledges and practices are strong and Yolŋu languages are spoken across all generations. The most common language in the community is Djambarrpuyŋu (ABS, Citation2016), which is also the most frequently reported First Nations Australian language being spoken in Australian homes (Simpson & Wigglesworth, Citation2019). Dhaḻwaŋu, Galpu, Golpa, Golumala, Gumatj, Dätiwuy, Ḻiya’gawumirr, Ḻiya’dhalinymirr, Wangurri, Warramiri and Gupapuyŋu are also understood and spoken in Galiwin’ku. Yolŋu sign language is used in everyday interactions (Lowell & Gurimangu, Citation1996). Less than 5% of people in this community speak English at home (ABS, Citation2016) but many health and education services are delivered predominantly in English.

Method

Collaborative research team

Our project’s intercultural and multilingual team of Yolŋu and Balanda researchers worked collaboratively – djäma räl-manapanmirr: collecting, analysing, checking and re-checking data together; co-creating resources; and putting all of our names on our work as authors. Each researcher contributed specialist skills and knowledges. We centred Yolŋu ways of knowing, being and doing because this research was conducted in a Yolŋu community where Yolŋu hold authority, and as a team we endeavoured to implement a decolonising approach to research (Ireland, Maypilama, Roe, Lowell, & Kildea, Citation2021). Throughout all phases of the project, we prioritised relationships and reflexivity, which are recognised as essential for genuine collaboration in intercultural research (Nicholls, Citation2009).

It is important to begin by introducing ourselves so you know something about the lenses through which we researchers understand our work. Emily Armstrong is an Australian researcher, PhD candidate and speech-language pathologist from a convict and white-settler family who have been in Australia for eight generations. Dorothy Gapany Gumbala is a Gupapuyŋu–Daygurrgurr woman, great-grandmother and retired bilingual educator from Galiwin'ku, Elcho Island in North-East Arnhem Land. Associate Professor Ḻäwurrpa Elaine Maypilama (research supervisor) is a Warramiri woman from Galiwin’ku, an educator and a researcher recognised for her high level of expertise in culturally responsive research. Yuŋgirrŋa Dorothy Bukulatjpi is a Yolŋu researcher from the Warramiri clan and a senior woman in Galiwin’ku community. Associate Professor Anne Lowell (research supervisor) is a non-Indigenous researcher, originally trained as a speech-language pathologist, who has worked on collaborative qualitative research with Yolŋu for over 30 years. Professor Lyn Fasoli and Doctor Sarah Ireland are non-Indigenous academics and researchers supervising this work as part of Emily’s PhD candidature. The research process was guided by a Ŋaraka-ḏälkunhamirr Mala (Backbone Committee) of advisors including senior members of the local Yolŋu community who advised researchers and contributed to data and analysis through regular discussion.

Research design

Our project followed research guidelines developed by experienced Yolŋu researchers from Galiwin’ku community (Garŋgulkpuy & Maypilama, Citation2005; Yalu Marŋgithinyaraw, Citation2012). During the planning phases of the project, the Ŋaraka-ḏälkunhamirr Mala (Backbone Committee) and members of the community’s Regional Council Local Authority emphasised the importance of achieving action and change through research (Christie, Citation2006; Maypilama, Garŋgulkpuy, Christie, Greatorex, & Grace, Citation2004). We have been researching intercultural communication through methods that involve intercultural communication so talking about intercultural communication and doing intercultural communication were happening in tandem.

Phase 1

In the first research phase (Armstrong et al., Citationsubmitted), we explored Yolŋu and Balanda participant perspectives on intercultural communication using video-reflexive ethnography (Iedema et al., Citation2019; Lowell et al., Citation2005; Lowell & Gurimangu, Citation1996) – i.e. participants analysed recordings of their own interactions. Phase 1 case studies were five different early childhood assessment interactions (in health, allied health, education and family support service contexts). We connected Phase 1 research findings about intercultural communication processes to a place-based, Yolŋu metaphor (Armstrong et al., Citation2021; Armstrong et al., Citationsubmitted).

Development of draft resources to share Phase 1 findings

Before beginning Phase 2 of data collection, researchers (Emily, Ḻäwurrpa, Gapany and Yuŋgirrŋa) developed first draft multi-media resources integrating Phase 1 findings using the metaphor. Example resources are pictured in the findings section of this paper.

We developed the first drafts of text and photograph based resources online during the early months of the Australian COVID-19 pandemic (March–June 2020) when Emily and Yolŋu colleagues were separated by 3570 kms. Gapany and Ḻäwurrpa accessed an online digital meeting platform (Zoom) with technical support from Anne (see ). We met regularly online and recorded our researcher reflections and discussions, which form part of our findings shared in this article.

Figure 1. Screenshot of researchers using an online meeting platform to develop first-draft text and photo resources during lockdowns in the COVID-19 pandemic.

We recorded audio-visual resources using simple and available technology (e.g. a hand-held audio recorder and a small, unobtrusive camera with tripod). We recorded in locations and languages suitable to participants – often in comfortable spaces outside participants' homes or in local workplace meeting spaces. We also collected natural objects from the beach in Galiwin’ku to use as tactile resources to support participant engagement with key concepts.

Phase 2

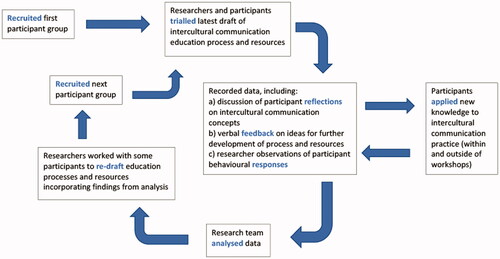

In Phase 2, the focus of this article, we built on Phase 1 findings using participatory action research (PAR) (Kindon, Pain, & Kesby, Citation2007) to co-design an intercultural communication educational process and resources with Yolŋu and Balanda end-users. Phase 2 consisted of iterative cycles of action and reflection (Kindon et al., Citation2007) as illustrated in . Each participant group engaged in one cycle of reflection and action using draft intercultural communication educational processes and resources.

Figure 2. Iterative cycles of action and reflection during co-creation of intercultural communication educational process and resources.

During each cycle, we re-drafted and updated educational processes and resources based on data analysis before sharing them with the next group of participants (see ). Researchers reinforced and expanded features of the educational process that we observed to be effective prompts for deepening participant reflections and facilitating effective intercultural communication within workshops. Some participants were actively involved in re-drafting (e.g. changing the order in which concepts were presented, making new audio-visual recordings, editing Yolŋu language text).

PAR was chosen for Phase 2 of the research because its orientation encourages creative collaborative techniques (McMenamin & Pound, Citation2019) and “demands methodological innovation” (Kindon et al., Citation2007, p. 13) to respond pragmatically to emerging findings and needs (Chevalier & Buckles, Citation2019). PAR’s collaborative approach to facilitating reflection, communication, action, social transformation and change (Baum, Citation2016; Kindon et al., Citation2007) supported us as researchers in meeting our responsibilities to respond to identified needs in the community and to create tangible benefit and positive impact for those participating in the research (AIATSIS, Citation2020).

Ethics

This project was approved by Charles Darwin University Human Research Ethics Committee (H18063) and supported by the Northern Territory Government Department of Education Research Subcommittee (Ref 14505) and by the Galiwin’ku Regional Council Local Authority (11 April 2018), representing local community members.

Participants

Phase 1 findings about intercultural communication were relevant and of interest to people communicating across a broad range of contexts and so Phase 2 participants included Yolŋu and Balanda staff and/or clients of local health, education and community service contexts across all age groups. Fifty-two adults participated in seven group discussions and 17 individual discussions. Of total participants (n = 52), 27 were Balanda, 24 were Yolŋu and 1 was a First Nations Australian person from another region. All Phase 2 participants were over 18 years old and, after the project was explained in their preferred language, gave their informed consent to participate.

We recruited 16 participants from Phase 1 and the remaining 36 participants were Yolŋu and Balanda community members purposively recruited through community networks or workplaces (e.g. health, education or community services organisations) due to their interest or expertise in intercultural communication. Three researchers (Emily, Gapany and Yuŋgirrŋa) and five research supervisors (Anne, Ḻäwurrpa, Lyn, Sarah and Sally) were included in participant numbers because our perspectives were also recorded as data through the project’s participatory action research process.

Data collection

We conducted seven cycles of action and reflection within our PAR process (see ) in the form of seven collaborative group workshops, augmented by data from an additional 17 discussions with individual participants. Discussions (40 minutes−2 hours) were conducted in local workplace meeting spaces, mostly face-to-face but sometimes online or by phone (due to COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns or travel restrictions). Researchers provided refreshments (food and drinks) and supported participants with transport to attend meetings, as is appropriate in this cultural context.

We conducted discussions using a Yolŋu conversational approach, waŋanhamirr bala-räliyunmirr (back and forth discussion): engaging, talking, listening, observing, and responding. Together, researchers and participants talked about, and listened to, the dhuḏi dhäwu – the deep story about the roots of intercultural communication processes. The importance of sharing and understanding deeper meaning, rather than superficial messages, has been emphasised by Yolŋu researchers in this community before (Baṯumbil, Citation2012; Lowell, Maypilama, & Gundjarranbuy, Citation2021), particularly in relation to the “full and deep and true stories” (Lowell et al., Citation2021, p. 175) required for effective health education. We have used the word resonance to describe participant responses that demonstrated connection to the deeper meanings of concepts and understanding of the relevance of those concepts to their own intercultural communication practice.

Recorded data included participant reflections on concepts that resonated with them; participant feedback on features of resources that could be built upon or changed to make them more meaningful, more accessible or more useful; and researcher observations of participants’ behavioural responses, particularly how they communicated interculturally with each other during the PAR process. We audio-recorded all except one discussion, which was recorded with written notes only due to participant preferences.

Paying close attention to language is essential for valuing and understanding multiple perspectives when analysing interactions (Charmaz, Citation2014) and for following ethical and effective processes for research with Yolŋu (Yalu Marŋgithinyaraw, Citation2012). Participants and researchers chose which languages they preferred to speak during all research activities. We recorded data in Yolŋu languages and English with a roughly even split reflecting the balance of Yolŋu and Balanda participants. Yolŋu and Balanda researchers worked together on meaning-based interpretation (Lyons et al., Citation2022; Mitchell et al., Citation2021) and transcription in English.

Data analysis

We used regular reflective discussions between researchers to analyse data collaboratively throughout PAR cycles. After each discussion with participants, researchers discussed and made notes on concepts raised by participants and researcher analyses of these concepts. We also talked about and noted our observations of, and analyses of, participant responses to draft educational processes and resources.

Researcher discussions were an accessible, meaningful and comfortable process for our team to conduct collaborative analysis during PAR. Processes of collaborative analysis require allocation of sufficient time (our analysis process was ongoing from March 2020–June 2021), use of a variety of accessible mediums, high levels of engagement and commitment (McMenamin & Pound, Citation2019) and strong relationships between researchers to support each other through tensions and challenges of reflexive processes (Cahill based on work with the Fed up Honeys, Citation2007).

After completing all cycles of data collection, action and reflection, the research team reviewed both participant data and researcher reflections and collaboratively discussed and recorded key concepts in both Djambarrpuyŋu and English languages to develop the story of our work that we are sharing through this article.

Result

In this section of the article we describe our intercultural communication educational process and resources. We share findings about the features that resonated with participants as evidenced by participant reflections and feedback, observations of participant engagement, and researchers’ reflections. In this project, the outputs and the processes of creating them are interwoven and so we explain them together.

We have co-created an interactive workshop facilitated by Yolŋu and Balanda researchers working together because participant feedback indicated that two of the most valuable aspects of the research experience were: (1) opportunities to observe and be part of enacted intercultural communication and (2) opportunities to discuss concepts with people from different cultural backgrounds. During our workshop, reflection and discussion are prompted by multi-media resources which include: audio-recordings and text in multiple languages; photographs of land and water in Arnhem Land; tactile resources in the form of collected natural objects; and videos recorded in the research setting. Our study found that multiple mediums provided multiple ways for different people to access, connect with, and enact key concepts about intercultural communication.

Djämamirriyam ga waŋanhamirr nhä limurr ga marŋgithirr ga maḻŋmaram bala gurrupana wirripuwurruŋgala: Enacting and discussing what we’ve found out to give the process to others

As researchers and resource co-creators, we have tried not to separate theory and practice in our processes. We don’t want to just talk about intercultural communication but we want to show the richness and complexity of the processes by doing intercultural communication when we share our work. We enacted our intercultural communication research findings in a workshop designed to give the process to others so they can feel and understand how it works, Yolŋu to Balanda and Balanda to Yolŋu. Some participants said that watching and listening to how Yolŋu and Balanda researchers interact interculturally was the most powerful and meaningful part of the educational process for them, during both in-person interactions and online interactions.

During our interactive workshops, participants were hearing intercultural communication concepts expressed in two languages: English and a Yolŋu language. These concepts were embedded in a Yolŋu metaphor. Participants could see and feel that metaphor in the land and water through photographs, videos and natural objects. Participants had the opportunity to discuss all these elements with researchers from different cultural groups and this helped them deepen their understanding and reflect on how they could apply what they were learning. As one participant said, the educational process “gave us an ability to connect to not only the ideas but the meaning behind the ideas”.

I don’t think we really knew how much we didn’t know until we saw that other layer. And that other layer is the physical realness of it, not just the description or what you’re told or read. So then it’s about connection – the resources enabled us to feel and be part of this. They forced us to move to that deeper level. Balanda participant

We found that Yolŋu ways of communicating holistically do not fit easily with Balanda structures. Balanda organisations often structure time in short blocks to meet specific goals, for example: allocating one workplace meeting to try to come to an agreement regarding a complex issue; 20 minute academic conference presentation time-slots; social media video length limits. In contrast, Yolŋu connections hold everything together holistically and need to be told together, requiring more time.

When Yolŋu are sharing information in various formats, there are things we (Ḻäwurrpa, Yuŋgirrŋa and Gapany) have to talk about before we share. First we need to say who we are, where we come from, how we are connected to you, the experiences we are drawing on, and what permissions we have to share the knowledge we are discussing. These connections are not merely a frame that can be edited down to meet time frames and structures imposed by another culture. The educational process we co-constructed honours these connections and prioritises time for them to be discussed.

When workshop participants discussed intercultural communication, they were using terminology that was more closely related to feeling and impact than to description. They were connecting to our work and reflecting on how to change their behaviour in their own intercultural communication. During subsequent meetings with participants, researchers noticed changes in participant intercultural communication behaviours to be more aligned with what we had discussed during research activities (e.g. changes to language use and power dynamics in intercultural team meetings). This finding, demonstrating change as an outcome of research, is consistent with principles of reciprocity, as Yuŋgirrŋa explained:

You are getting something from Yolŋu and we expect you to act on it: act on what we are giving you from our talking, from our thinking, from the words we are saying.

Lakaram ga dhäwu ga dharaŋan dhäruk djinawapuy: Sharing and understanding the inner meaning of stories through our languages and words

For Yolŋu, dhäruk (languages) are key to identity (Lowell et al., Citation2019) and are connected to bäpurru (clans) and yirralka (ancestral homelands) – so languages are connected to the places the water flows through in the metaphor used in our resources. Yuŋgirrŋa explained:

We talk like Warramiri because we live by the sea. My mother, my father and my eldest sister challenged me (Yuŋgirrŋa) to speak my own language when I was young. They were talking to me in Warramiri language but I only decided to speak it when I was older. It was in my ŋayaŋu (inner being) and it sort of bubbled up. … For different clans, language is already in our ŋayaŋu (inner being). That’s what I feel.

In a remote Yolŋu community, living First Nations Australian languages meet a colonising language, English, and bring our attention to communication at every moment. Not sharing a common first language meant that our multilingual, intercultural research team were analysing the meanings within words, in both Yolŋu languages and English, all the way through the research process. This was a time-consuming yet valuable process for establishing shared intercultural understandings between researchers, and between researchers and participants.

For our resources to be accessible to speakers of both languages, we needed to develop equivalent and meaningful ways to describe complex concepts in two very different languages. Researchers discussed words and concepts in both languages while we were creating first drafts of resources. Emily, who has been learning Yolŋu languages throughout the research process, shared her screen through an online meeting platform and typed in Djambarrpuyŋu and English. Ḻäwurrpa and Gapany read from the screen and told Emily when the Djambarrpuyŋu words needed corrections.

We decided to use Djambarrpuyŋu language recordings, with English subtitles, in most of our multi-media resources because Djambarrpuyŋu is the language which most people in this community use and understand. However, when researchers and participants preferred to speak their own languages in recorded resources (e.g. Warramiri; Galpu), we encouraged them to do so. Written literacy levels in Yolŋu languages are varied and screen subtitles in Djambarrpuyŋu were inaccessible for many Yolŋu participants. Balanda participants were able to read English subtitles easily.

After selecting a language to use, we had several other choices to make about which words to choose from that language. For Yolŋu, everyone and everything in the natural world belongs to either Yirritja or Dhuwa moieties. When we shared our intercultural communication metaphor about fresh water meeting salt water, we used Yirritja words to talk about Yirritja water, because Ḻäwurrpa and Yuŋgirrŋa chose the metaphor and they are Yirritja. When Gapany joined our research team, she asked her husband Maratja, who is ŋäṉḏi-pulu (mother clan) and a djuŋgaya (executor, manager) for these stories, to come to hear about the research metaphor. Maratja gave his support for this research and helped Ḻäwurrpa choose suitable Yirritja words.

Our research findings showed that, in both Yolŋu languages and English, as people mature there are changes in the kinds of words we use and the depth of meaning we understand. While co-creating resources, researchers had long discussions with many different research participants and advisors to choose levels of language that would be accessible and convey the depth of meaning represented in our research findings. With feedback and input from participants, we balanced our use of words used by young Yolŋu parents with our use of gurraŋay dhäruk (Yolŋu academic language, used by senior people). In English we chose language that participants found relevant and useful to intercultural work in Galiwin’ku workplaces. For broader dissemination of our research findings (including this article), we have aimed to balance the languages which participants and researchers speak with the languages that wider audiences understand and listen to.

We found that for deep learning and deep understanding, people need to be able to have conversations about concepts in their own languages. As participants explained, many people feel uncomfortable about an imbalance in the length of discussions during meaning-based interpretation. For example, a short statement in English may take many more words to interpret thoroughly into a Yolŋu language, and vice versa. We found that processes of intercultural communication about deeper meanings require partners to sit with feeling uncomfortable, have confidence in their relationships, and support each other by investing time, discussing content in detail, and trusting in the high-level skills of qualified interpreters.

Lakaram ga dhäwu ga dharaŋan wuŋali mala ga nininyŋur rrumbal: Sharing and understanding stories through photographs and natural objects

Wuŋali mala dhuwal wäŋa mala ga gapu, dhiyal gali Ḻuŋgurrma (photographs of land and water in North-East Arnhem Land) ga nininyŋur rrumbal (and natural objects) made our resources colourful and interesting and they communicated much more than that. As suggested by participants, we co-created a set of cards to support reflection and discussion about each category within the metaphor while keeping the story connected as a whole. Photographs of how water flows in North-East Arnhem Land provided this visual connection.

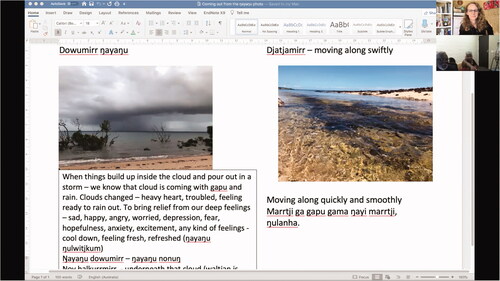

We decided together on photographs that matched the meaning and feeling of our intercultural communication research concepts. Using screen sharing in an online meeting platform, we searched and discussed photos Emily had taken during her travels in Arnhem Land (see ). Gapany gave an example of how we chose a photo (see ) to represent a research category from our Phase 1 findings:

Figure 3. Emily's photograph we chose to communicate the concept: Ŋayaŋuŋur ga dhawaṯthun – Nhaltjan nhe dhu milkunhamirr ga lakaranhamirr nhunapinya nhe (Coming out from within us – Showing and expressing yourself to open up the story).

The picture shows dark clouds and it’s starting to rain. It’s never just normal rain coming from the cloud but it comes from a direction, it comes from someone’s place. Water’s coming. The tide’s coming in, touching the mangrove trees. When rain and water are coming together – it’s dark and it’s heavy rain coming towards us – we feel it’s coming out from within us. That’s how we feel – that’s why we chose this picture to communicate the idea, it’s about showing and expressing yourself to open up a story.

Using an online meeting platform (Zoom) to select pictures and co-design resources was a new way of working together for our research team. This was challenging for us all but we built on our existing relationships and it was effective, as Ḻäwurrpa explained:

When we (Ḻäwurrpa, Yuŋgirrŋa and Gapany) first started, we struggled. And through the reality of doing djäma (work) on a computer – it’s now helping. Same when you (Emily) first saw gapu dhäwu (water story) and took pictures – you struggled to find the meaning of it. … But we tried that way (Zoom) – we made it easier, both our work together – so it’s keeping us strong.

When we shared photographs with participants, we found that photos carry many layers of meaning and connections for both Yolŋu and Balanda in different ways, depending on the lenses people see through. Some participants told us that the photos in our resources gave them a feeling straight away, and that the feeling helped them to understand intercultural communication concepts more deeply. Some Yolŋu participants became emotional while looking at photographs of familiar places, thinking about their personal connection to the story behind that photograph and remembering and missing family from that place. Gapany explained:

Pictures really help us (Yolŋu) to understand because wherever a photo is taken, the people from that area have a story about that place. The story is there for us to understand and it has a deeper meaning. When we see a picture we think of the people who are connected to that place. You can see that gapu (water) and it can speak to you because it’s your gapu (water). That wäŋa (place) is your wäŋa (place). And it helps to understand, to share yuwalk dhäwu (real stories).

Photographs and natural objects in our resources helped Balanda participants to understand how fundamentally Yolŋu are connected to the land, the fresh water and the salt water. As Gapany explained:

We (Yolŋu) sing a song from the fresh to the salt water in the songlines. It’s in the language and the identity of who we are. That’s where we can see each other and connect to each other. The pictures of the land and the water bring out the identity which is where we Yolŋu communicate from.

The photos and natural objects we used in our resources connected the research concepts to a holistic metaphor represented in the landscape. They also reminded participants of the importance of environment and place in intercultural communication processes. We decided to use natural objects as tactile resources to facilitate participant reflection on one aspect of our intercultural communication metaphor. We collected stones, shells and driftwood on the beaches in Galiwin’ku (see ) to share concepts about how communication is shaped by individual peoples’ experiences, like objects which have travelled in the sea are shaped by the water. A friend, Guymun, collected pandanus and coloured it with natural dyes from the local environment then wove a basket for us (see ) to keep our nininyŋur rrumbal (natural objects) in.

When they were exploring our multi-media resources, we encouraged participants to hold natural objects in their hands and to reflect on the meaning and personal connections they felt. We noticed that participants paused while they held and explored the stones, shells and driftwood. Participants were still and quiet and spent time reflecting individually. One Balanda participant commented:

That’s good because it’s tactile. … It’s tactile and that has a story to tell. So what’s the story? … You can use objects to provide a different type of language. A different type of being in contact with each other. Which helps again, to create words, and describe something. … through experience (we can create) an opportunity … to be connected to country. Balanda participant

Wuŋili marraŋ videoyu ga mayali dhawaṯmaraŋ ga gakal dhuwali: Capturing videos to reveal your real meaning

We recorded video resources during fieldwork in Galiwin’ku (for a brief example, see Supplementary material). Researchers and participants video-recorded natural, unscripted and unstructured discussions about key research concepts, in peoples’ preferred languages. We were aware of tensions and uneven power in editing processes during co-creation of resources because editors decide how the story is put together. Research team members who are not comfortable with computers were supported to engage with the editing process by working collaboratively with other reseachers, giving detailed instructions.

During PAR cycles, participants gave feedback on what resonated with them in video resources and what they would like more information about. Based on participant responses, researchers re-edited draft videos and then took new versions back to those who were filmed to seek consent before sharing new versions. We also recorded new videos to meet needs identified by Phase 2 participants.

Our videos guided audiences through our research findings by combining words, voices, facial expressions, body language, environment, movement, and text on a screen. We found that video was a powerful way to connect all these elements together to send a holistic message by showing communication processes happening in context. When we shared videos with participants, we received feedback that our approach to recording made the resources feel real and authentic because participants could see who was speaking, where they were and how they communicated with others in unscripted conversation. For example, one Balanda participant said the videos “made me feel like I could actually be part of it”.

We found that video is particularly useful for exploring concepts during intercultural work when there are no direct translations of some words and we need to explore their meaning in more depth to establish shared understanding. As Yenhu, a research advisor on our Ŋaraka-ḏälkunhamirr Mala (Backbone Committee) said to Emily:

Waku (daughter) come, next time you’re having a conversation, get the video. Make a video of two Yolŋu having a conversation in Yolŋu dhäruk (languages) about these ideas. Because there is no one word for ‘intercultural’ in our languages, in Djambarrpuyŋu or any of our Yolŋu languages. … In language, in conversation, it’s better if we do video taking. Because to get that description right, it has to come up with the expressions, it has to come up with the actions. Because sometimes we can say a word, but we need to capture that expression in that word to make it stronger. To make it more meaningful. To make it more alive! To make it so you know where the wording is heading, where it is taking you. Yenhu, Research Advisor

Video has been effective for sharing our research metaphor because it shows the flow of water and the flow of communication – both are dynamic and moving. Participants could see and hear the flow of communication on videos that show people speaking about their own perspectives in their own voices and languages. People who are watching can easily recognise who is speaking and they know that person was prepared to have their face connected to the message. Showing who shares the message communicates that they think it is an important and true message to share which is a kind of proof or verification.

We found that watching and hearing water flow helps people feel calm and reflect on themselves. The places where videos were filmed were important and were noticed by most participants. Video gives people context about where the research was conducted – the environment, the community, the people. Places and settings can have a lot of specific meaning to Yolŋu that Balanda may not be aware of. In a Yolŋu context, there are complex and important processes of recognising ownership and sharing with appropriate permission.

We developed processes for informed consent with respect for Yolŋu control over their Intellectual Property and Yolŋu sovereignty over their lands and waters. Such processes have made our resources stronger and give us more confidence in sharing them. We adapted western academic forms to include informed consent processes for use of places in video resources to convey specific messages, for example seeking consent from djuŋga-djuŋgaya mala (executors, managers) for lands and waters on which we filmed.

While these consent processes are now something I (Emily) am becoming aware of, I could not follow them independently. These processes will always need to be navigated in partnership with Yolŋu researchers because experienced Yolŋu are the only ones who understand the complex laws and protocols in which we are working.

Discussion

This project enacted a complex process of collaboration and connection at a cultural interface (Nakata, Citation2007) through djäma rrambaŋi (working together) all the way. Our aim was to co-create an educational process and multi-media resources designed to inform and facilitate intercultural communication in a Yolŋu community. We found that our educational process and resources have broad relevance to, and resonance with, Yolŋu and Balanda staff and clients of health, education and community services across age groups in this community. In this section we discuss implications of our findings for practice as well as for future research.

We have shared findings about our processes of räl-manapanmirr (collaborating) and key features of our educational process and multi-media resources that participants connected with – dhä-manapanmirr. As we (the research team) developed new understandings, we changed our processes to enact our findings about intercultural communication and we saw and heard participants do the same. We facilitated intercultural communication by creating opportunities for participants to engage with each other and to value multiple knowledges, multiple languages and multiple worldviews at the same time. This research translation process was supported by key features of our PAR design: being inclusive of multiple ways of understanding and expressing; paying attention to relationships and dialogue; and emphasising collaborative knowledge production and knowledge performance (McMenamin & Pound, Citation2019; Pain, Kindon, & Kesby, Citation2007).

Drawing on symbolic interactionism (Charmaz, Citation2014), we approached this work with an understanding that the way people interpreted their experiences with our educational process and resources would influence how they behaved in response. We have analysed how participants from two different cultural groups responded to and connected with multi-media resources to facilitate intercultural communication. We found that participants engaged with our resources through multiple senses. The ways they interpreted and responded to the resources were different depending on who they are, who they were communicating with, their knowledges and their past and present experiences. When developing resources, team members from the same cultural and linguistic backgrounds as end-users are essential because they can interpret how people respond to the messages they receive.

Use of metaphor drawn from local First Nations Australian knowledges has previously been demonstrated as a culturally meaningful way to develop understanding of concepts and processes in First Nations Australian communities (e.g. Amery et al. (Citation2020); Mitchell et al. (Citation2021)). Our study reinforces the value of local metaphor for intercultural communication with First Nations Australian peoples. Additionally, we demonstrated that a Yolŋu metaphor, communicated through multiple mediums, is also effective for building deeper understandings for non-Indigenous people who work in First Nations Australian communities.

Similar to learning approaches proposed by Nakata, Nakata, Keech, and Bolt (Citation2012), our educational process and resources provided language and tools to actively support participants to engage in “open, exploratory and creative enquiry” (Nakata et al., Citation2012, p. 121) into the complexities of communication at the cultural interface. Navigating interactions at a cultural interface requires us all to encounter layers of complex meaning and to have our ways of understanding the world disrupted by communication partners who hold different knowledges and perspectives. Realising “the conceptual limits of your own thinking” (Nakata et al., Citation2012, p. 121) can be both challenging and fascinating.

We wanted all participants to feel connected to the collaborative work we were doing and to remain engaged in the project’s complex processes of intercultural communication. We carefully considered how people could be “brought to the encounter … (with) complex and contested knowledge spaces” (Nakata et al., Citation2012, p. 136) through our process and resources. We mindfully incorporated both Balanda and Yolŋu knowledges, practices and languages in our resources and this created opportunities for participants to develop new understandings while maintaining connection and feeling included in the collaboration. We hope that you, as a reader, can become part of this ongoing process of intercultural communication too.

Further research is required to explore the application and resonance of our workshop and multi-media resources in other intercultural communication contexts. In future, the workshop will be offered to groups who are interested in exploring the intercultural communication education that we have co-created. Our research outputs centre Yolŋu knowledges and so need to be understood through discussion with Yolŋu, in a way that also benefits the Yolŋu community who co-created them, rather than being shared as stand-alone resources. Reciprocity requires that when we develop new understandings in partnerships with others, we share them with the people who helped us to develop them. For both researchers and practitioners, it is important to apply the principle of ‘nothing about us without us’ by sharing knowledge in ways that people can understand it, connect to it, and make their own informed choices about acting on it.

For First Nations peoples around the world, “fragmentation has been the consequence of imperialism” (Smith, Citation2012, p. 71). In both research and practice, non-Indigenous systems fragment holistic ways of understanding and communicating to fit imposed Western structures, timelines and frameworks (as we have done to fit our processes and findings into subheadings in this journal article, for example). We have navigated these challenges in our research in ways that may not be practical within the current communication restrictions of many workplaces. Our findings demonstrate that these systemic workplace restrictions and structural inequities need to change.

Processes of co-creating resources with intercultural teams may require non-Indigenous team members to “intentionally restrain” (Mitchell et al., Citation2021, p. 215) lenses brought from outside the community in order to optimise exploration and understanding of concepts based on First Nations Australian languages and knowledges – for example, restraining biomedical health perspectives (Mitchell et al., Citation2021) or resisting neoliberal narratives of education (Osborne & Guenther, Citation2013). For Balanda, recognising our own lenses and challenging our own knowledge systems are steps towards decolonising systems.

In order to facilitate intercultural communication, practitioners must commit to collaborative long-term engagement at personal and systemic levels and be activists for changing dominant, non-inclusive systems (Baum, Citation2016). Both the methods and findings shared in this article demonstrate the importance of working through intercultural communication challenges together and continuing to do our best together. Ŋunhi limurr dhu maḻŋmaram gumurr-ḏal, limurrdja dhu marrtji rrambaŋi, ŋuliwitjan gumurr ḏälkurr – when we come across challenges, we find a way through our struggles together.

Conclusion

Räl-manapanmirr ga dhä-manapanmirr (collaborating and connecting) were the central principles of both our methods and findings. Yolŋu and Balanda have contributed to our work with knowledge from their rich experiences communicating at cultural interfaces in health, education and community services. Together, we co-created an educational process and multi-media resources to inform and facilitate intercultural communication. During the educational process, participants explored concepts, practiced strategies, and reflected together on how they could apply those concepts and strategies to strengthen their ongoing communication, for example during the provision of health and education services. Through sharing our work, we endeavour to expand intercultural spaces and processes to include, encourage and support more people from different cultural understandings to collaborate and connect.

In research and practice, räl-manapanmirr djäma – collaborative intercultural work requires us all to challenge dominant narratives and advocate for systemic change to accommodate and value different understandings and different ways of communicating. Successful intercultural communication actively supports partners from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds to feel included and connected to the dynamic processes we are all navigating together. Intercultural communication is something we can’t do alone, we can only do it together – djäma rrambaŋi.

Facilitating_intercultural_communication_-_project_introduction.mp4

Download MP4 Video (67.1 MB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the participants and research advisors who contributed to this collaborative work and remained engaged and supportive throughout the long process. Yalu Aboriginal Corporation, Galiwin’ku, shared their work space with members of our team when we needed it for researcher meetings. Alice McCarthy at Yalu Aboriginal Corporation provided support for Yolŋu researchers who would not otherwise have access to mobile phones or computers to communicate with team members. A/Prof Sally Hewat contributed to this research process as one of Emily’s PhD supervisors.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2070670.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). 2016 Census: QuickStats: Galiwinku. Retrieved 4 September 2021 from http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC70106

- AIATSIS. (2020). AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research. https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/aiatsis-code-ethics.pdf

- Amery, R., Wunungmurra, J.G., Gondarra, J., Gumbula, F., Raghavendra, P., Barker, R., … Lowell, A. (2020). Yolŋu with Machado-Joseph disease: Exploring communication strengths and needs. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22, 499–510. doi:10.1080/17549507.2019.1670863

- Armstrong, E., Bukultjpi, Y., Gumbala, D. G., Hewat, S., Lowell, A., Maypilama, Ḻ. E., Fasoli, L., & Ireland, S. (2021). Exploring intercultural communication processes to facilitate culturally responsive practice. [Workshop]. Speech Pathology Australia National Conference, Darwin NT/online.

- Armstrong, E., Maypilama, Ḻ., Bukulatjpi, Y., Gapany, D., Fasoli, L., Ireland, S., … Lowell, A. (submitted). Understanding and exploring intercultural communication through a Yolŋu (First Nations Australian) metaphor.

- Baṯumbil. (2012). We need the story from the roots: Improving chronic disease education for Yolŋu, Yalu Marŋgithinyaraw. http://yalu.cdu.edu.au/healthResources/index.html

- Baum, F.E. (2016). Power and glory: Applying participatory action research in public health. Gac Sanit, 30, 405–407. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.05.014

- Booth, S., Armstrong, E., Taylor, S.C., & Hersh, D. (2019). Communication access: Is there some common ground between the experiences of people with aphasia and speakers of English as an additional language? Aphasiology, 33, 996–1018. doi:10.1080/02687038.2018.1512078

- Cahill based on work with the Fed up Honeys, C. (2007). Participatory data analysis. In S. Kindon, R. Pain, & M. Kesby (Eds.), Participatory Action Research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place (pp. 181–187). London: Routledge.

- Cahill, C., & Torre, M.E. (2007). Beyond the journal article: Representations, audience, and the presentation of Participatory Action Research. In S. Kindon, R. Pain, & M. Kesby (Eds.), Participatory Action Research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place (pp. 196–205). London: Routledge.

- Caty, M.E., Kinsella, E.A., & Doyle, P.C. (2015). Reflective practice in speech-language pathology: A scoping review. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 411–420. doi:10.3109/17549507.2014.979870

- Charlton, J.I. (1998). Nothing about us without us: Disability oppression and empowerment. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London: SAGE.

- Chevalier, J.M., & Buckles, D.J. (2019). Participatory action research: Theory and methods for engaged inquiry. Taylor & Francis Group, ProQuest Ebook Central. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

- Christie, M. (2006). Transdisciplinary research and Aboriginal knowledge. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 35, 78–89. doi:10.1017/S1326011100004191

- Fisher, K., Williams, M., FitzHerbert, S., Instone, L., Duffy, M., Wright, S., Suchet-Pearson, S., Lloyd, K., Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr-Stubbs, M., Ganambarr, B., Maymuru, D., & Bawaka Country. (2015). Writing difference differently. New Zealand Geographer, 71, 18–33. doi:10.1111/nzg.12077

- Garŋgulkpuy, J., & Maypilama, L. (2005). Methodology for Yolŋu research. http://learnline.cdu.edu.au/yolngustudies/docs/Garnggulk_methodology_for_Yolngu_research.pdf

- Iedema, R., Carroll, K., Collier, A., Hor, S-y., Mesman, J., & Wyer, M. (2019). Video-reflexive ethnography in health research and healthcare improvement: Theory and application. London: CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9781351248013

- Ireland, S., Maypilama, E.L., Roe, Y., Lowell, A., & Kildea, S. (2021). Caring for Mum On Country: Exploring the transferability of the Birthing On Country RISE framework in a remote multilingual Northern Australian context. Women and Birth, 34, 487–492. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.017

- Kindon, S., Pain, R., & Kesby, M. (Eds.). (2007). Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place. London: Routledge.

- Kral, I., Fasoli, L., Smith, H., Meek, B., & Phair, R. (2021). A strong start for every Indigenous child (OECD Education Working Papers, Issue 251). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/a-strong-start-for-every-indigenous-child_ebcc34a6-en

- Lowell, A. (2013). "From your own thinking you can’t help us": Intercultural collaboration to address inequities in services for Indigenous Australians in response to the World Report on Disability. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 101–105. doi:10.3109/17549507.2012.725770

- Lowell, A., Brown, I., Marrŋanyin, B., Flack, M., Christie, M., Snelling, P., & Cass, A. (2005). Sharing the true stories: Improving communication between health staff and Aboriginal patients, Stage 1, Interim project report. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health. https://www.cdu.edu.au/centres/stts/home.html

- Lowell, A., & Gurimangu, N. Y. (1996). Communication and learning at home: A preliminary report on Yolngu language socialisation. In M. Cooke (Ed.), Aboriginal languages in contemporary contexts: Yolngu Matha at Galiwin'ku (pp. 109–152). DEETYA Project Report.

- Lowell, A., Maypilama, E.L., & Gundjarranbuy, R. (2021). Finding a pathway and making it strong: Learning from Yolŋu about meaningful health education in a remote Indigenous Australian context. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 32(Suppl 1), 166–178. doi:10.1002/hpja.405

- Lowell, A., Maypilama, Ḻ, Guyula, Y., Guyula, A., Fasoli, L., … Godwin-Thompson, J. (2019). Ŋuthanmaram djamarrkuḻiny’ märrma’kurr romgurr: Growing up children in two worlds. Retrieved 22 January 2022 from www.growingupyolngu.com.au

- Lowell, A., Schmitt, D., Ah Chin, W., & Connors, C. (2014). Provider Health Literacy, cultural and communication competence: Towards an integrated approach in the Northern Territory. http://www.cdu.edu.au/health-wellbeing/indigenous-health-literacy

- Lyons, R., Armstrong, E., Atherton, M., Brewer, K., Lowell, A., Maypilama, Ḻ… Watermeyer, J. (2022). Cultural and linguistic considerations in qualitative analysis In R. Lyons, L. McAllister, C. Carroll, D. Hersh, & J. Skeat (Eds.), Diving deep into qualitative data analysis in communication disorders research. J&R Press.

- Martin/Mirraboopa, K. B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist re-search. Journal of Australian Studies, 27, 203–214. doi:10.1080/14443050309387838

- Maypilama, Ḻ., Garŋgulkpuy, J., Christie, M., Greatorex, J., & Grace, J. (2004). Yolŋu longgrassers on Larrakia land. https://www.cdu.edu.au/centres/yaci/resources.html

- McMenamin, R., & Pound, C. (2019). Participatory approaches in communication disorders research. In R. Lyons & L. McAllister (Eds.), Qualitative research in communication disorders: An introduction for students and clinicians. J & R Press, Ltd.

- Mitchell, A.G., Diddo, J., James, A.D., Guraylayla, L., Jinmarabynana, C., Carter, A., … Francis, J.R. (2021). Using community-led development to build health communication about rheumatic heart disease in Aboriginal children: A developmental evaluation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 45, 212–219. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.13100

- Nakata, M. (2007). Disciplining the Savages: Savaging the Disciplines. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Nakata, N.M., Nakata, V., Keech, S., & Bolt, R. (2012). Decolonial goals and pedagogies for Indigenous studies. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society, 1, 120–140.

- Nicholls, R. (2009). Research and Indigenous participation: Critical reflexive methods. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 12, 117–126. doi:10.1080/13645570902727698

- Osborne, S., & Guenther, J. (2013). Red dirt thinking on power, pedagogy and paradigms: Reframing the dialogue in remote education. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 42, 111–122. doi:10.1017/jie.2013.19

- Pain, R., Kindon, S., & Kesby, M. (2007). Participatory action research: Making a difference to theory, practice and action. In S. Kindon, R. Pain, & M. Kesby (Eds.), Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place (pp. 26–32). London: Routledge.

- Pearson, L. (2015, 3rd August). Nothing about us, without us. That’s why we need Indigenous-owned media. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/aug/03/nothing-about-us-without-us-thats-why-we-need-indigenous-owned-media

- Perso, T. F. (2012). Cultural responsiveness and school education: With particular focus on Australia’s First Peoples – A review & synthesis of the literature. http://ccde.menzies.edu.au/CCDE-Publications-2012

- Simpson, J., & Wigglesworth, G. (2019). Language diversity in Indigenous Australia in the 21st century. Current Issues in Language Planning, 20, 67–80. doi:10.1080/14664208.2018.1503389

- Smith, L.T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). London: Zed Books.

- Staley, B., Armstrong, E., Amery, R., Lowell, A., Wright, T., Jones, C., … Hodson, J. (2020). Speech-language pathology in the Northern Territory: Shifting the focus from individual clinicians to intercultural, interdisciplinary team work. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 22, 34–39.

- UNESCO. (2013). Intercultural competences: Conceptual and operational framework. UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002197/219768e.pdf

- Yalu Marŋgithinyaraw. (2012). Doing research with Yolŋu. Retrieved 22 January 2022 from http://yalu.cdu.edu.au/healthResources/research.html