Abstract

Living in the transformative age is one of disruption, change, and infinite opportunity. However, living in a cloud-based world with self-driving cars, advanced robotics, artificial intelligence, e-health, 3-D printing, and COVID-19 can also be somewhat daunting, challenging, and even confronting. As speech-language pathologists, researchers, educators, and advocates, we need to be agile, more creative and connected to data, experiences, and people. Now more than ever, these connections will enable transformation and ensure the future of our profession.

speech-language pathologists are now practising on a global scale, in multiple languages and unique contexts, and the education of our future workforce is critical. Over the past 10 years, there has been rapid growth in the number of speech-language pathology training programs delivered by universities in Australia, as well as a significant shift in the demand for services and changing employment opportunities. In Australia, the profession has been planning for the future; Making Futures Happen, Building a Future workforce, and re-developing our Professional Standards. But, are we really cognisant of the global challenges and opportunities for our profession? Do we really value global connectivity?

In this discussion paper, authentic examples and plausible scenarios are being used to explore the global transformation of the speech-language pathology profession. Each will highlight some of the political, economic, societal, cultural, and technological influences on speech-language pathology research, teaching, and practices that are driving development, change, and innovation. Readers will be challenged to consider how thinking globally, with a focus on context, translation, and connection will enable them to rise to the challenges we face today and forge new paths for the future.

Inspiration

In 2011, Professor Deborah Theordoros delivered the Elizabeth Usher Memorial lecture to a packed auditorium at the Darwin Convention Centre. If you weren't there, imagine a thousand speech-language pathologists buzzing with excitement from all the new things they had learned the previous day, chatting incessantly to old friends or colleagues and enjoying the endorphins of new ideas and relationships. Fortunately, I was at that lecture (probably not in the front row and it wasn’t my first national conference) but I certainly did remember it. What I remembered was the WOW factor. Theodoros presented telehealth and innovations for a novel service delivery model (Theodoros, Citation2012). I was impressed and I was excited! I can’t remember the title of the presentation, or all the details (though if I searched long and hard, no doubt I would find my notes somewhere), but what I do remember is that Theodoros showed the profession something I hadn’t seen before, a machine that was commercialised and enabled therapy to be delivered remotely. Then, I recall learning about the research and evidence that demonstrated that the device and telehealth worked, and I was impressed!

I am an avid reader, but I also enjoy learning from my colleagues by attending professional development opportunities, like conferences. This specific presentation is one that has stayed with me (haunted me, driven me, inspired me) and I knew it was a “game changer”.

However, nine years later (pre-pandemic) as I was preparing my first attempt to present the 2020 Elizabeth Usher Memorial lecture, I was reflecting on the fact that the game really hasn’t changed in all that time. Yes, teletherapy was emerging, and telehealth was a possibility for service delivery but there was resistance.

It’s not as good

There's not enough evidence

The technology is not reliable

Not everyone has a computer (or a machine)

It's more expensive

It’s time consuming

It’s not safe, and what about confidentiality?

I also wondered if the profession didn’t really need to embrace innovation. Why would we change, when what we already do works? So, in writing the 2020 lecture I was ready to challenge the speech-language pathology profession to embrace innovation, explore opportunities beyond, and look ahead to “stay relevant”. However, before I had the opportunity to deliver (hopefully) the most inspirational lecture of my career, the world as we knew it was turned upside down, and for the first time in the history of speech-language pathology in Australia, our national conference was cancelled.

The disruption occurred on a global scale. Humanity experienced the biggest disruption of the modern era, but this wasn’t disruption due to technology or data, this was disruption due to a health pandemic. COVID-19 was not only responsible for the cancellation of the conference, but it also transformed society globally—changing when, where and how we do things. Who would have predicted that? Fortunately, the speech-language pathology profession responded and embraced online therapy and telehealth—almost instantly! So, why didn’t we do this earlier? Why did it take ten years and a worldwide pandemic?

In the 2021 Elizabeth Usher Memorial Lecture, my second opportunity, I wanted to challenge the profession differently. In this paper, through sharing my experiences, I want to challenge the profession to continue to connect and transform by valuing global and cultural connections and responding more rapidly to advances in technology and “big data”.

The transformative era

Throughout history, major technological advances disrupted and trigger a change in society. The first industrial revolution (c1760–c1840) saw the transition from hand to machine manufacturing with the emergence of power generated from steam and water. The changes extended from manufacturing to production, distribution, and transport lending to radical societal changes and notable increases in population and living standards (Aggarwal, Citationn.d.). Then, in the late nineteenth century, and early twentieth century, the second industrial revolution was a period of technological advancement, where electricity, telegraph, and railway networks expanded. In 1876 Alexander Bell patented the telephone, the first commercially available car was sold in 1888, in 1904 Sydney power was turned on and the first television was demonstrated in San Francisco in 1927. Refer to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Industrial_Revolution for further details.

Arguably, the third industrial revolution began in the late 1900s and was known as the digital (and information) era. Further advances in electronic and information technology enabled production to become automated. In 1960 touchphone technology emerged, the first personal computer in 1971, and the World Wide Web was invented in 1989, which became accessible to the public in 1991 (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_Revolution for further details). Society has been adapting, changing, and evolving for years, centuries, all brought about by technology and scientific development that dramatically influenced how, when, and why we did things.

Transformative like the word “transform” (its origin) has something to do with “change” and change can be challenging, particularly when the transformation or change arises from disruption. Disruption isn’t unfamiliar to Australians, just recently we have endured dramatic climatic events, world health crisis, world political upheaval, trade tensions, and of course rapid technological developments. Consider Apple Inc.© as an example. Since 2007, Apple has released 12 new models of the iPhone; since 2010, 21 different models of the iPad; and in the last 5 years six series of the iWatch. Each new model is a demonstration of advancement in technology that is enabling people to be connected now more than ever—to each other, devices, experiences, and data. All of these disruptions are driving change and challenging society to think and act differently, but as history suggests, disruption also creates opportunity.

The opportunity is the fourth industrial revolution, an era of transformation due to digitalisation, connected devices that are smaller, lighter, and smarter, data analytics, cloud computing, artificial intelligence as well as automation, and robotics (Schwab, Citation2016). Thought leaders have no doubt that we are now living a Transformative Age. Like the industrial revolutions before, technology is continuing to influence society in the same way (how, when, and where we do things) but with two key differences: (1) the speed at which changes occur, and (2) our increasing reliance on connectivity. Society is transforming and engaging in technology and data but as a profession is speech-language pathology keeping up?

In this discussion paper, I will situate the profession of speech-language pathology in the transformative era and highlight the value of global and cultural connections, as well as connecting with technology and data, to transform speech-language pathology education, clinical practice, research, and the profession. Schwab (Citation2016) argues that technology and big data may provide the fuel for this “fourth industrial revolution” but it will be the human element of transformation, that is, an individuals’ skills, hopes, visions, and passions, that will determine where we will get to and what will be achieved. I argue that these skills, hopes, visions, and passions come from valuing our connections and our profession.

Speech-language pathology profession in Australia

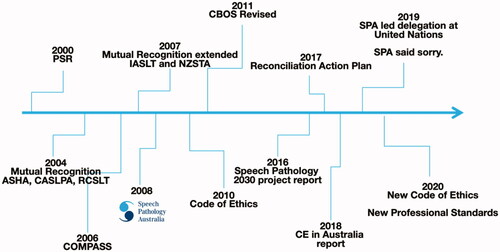

Speech-language pathology in Australia was founded in 1931 by Mrs. Elinor Wray and throughout the twentieth century, the profession emerged. Speech therapy was a recognised profession in Queensland in 1979 and the professional occupational standards were documented and launched 20 years later in 1994, the same year I graduated with a 3.5-year undergraduate degree at Cumberland College, the University of Sydney. Towards the end of the twentieth century, the association was re-named Speech Pathology Australia (SPA). A summary of the key developments in the profession over a 70-year period is provided in .

Table I. Key developments for the speech-language pathology profession in Australia throughout the twentieth century.

For further details on the history see the association wikipage entry (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speech_Pathology_Australia). As we entered the twenty-first century, the growth and development of the profession and association activities occurred at a more rapid pace (see for some of the key developments in the profession).

Figure 1. Key developments for the speech-language pathology profession in the twenty-first century.

In 2000, standards and procedures for professional self-regulation were established. In the early years, mutual recognition of professional training and standards was extended to the USA, Canada, UK, Ireland, and New Zealand. In 2016, the profession looked ahead and projected where we needed and/or wanted to be in 2030 (SPA, Citation2016) and in 2017, SPA established the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Committee and developed the first Reconciliation Action plan (SPA, Citation2017). In 2019, we advocated globally for people with communication and swallowing difficulties at the United Nations, and closer to home as a profession we said “sorry” (SPA, Citation2019). Just recently, SPA revised the code of ethics (SPA, Citation2020a) and launched new professional standards (SPA, Citation2020b). The profession in Australia is transforming at a rapid pace.

Speech-language pathology training in Australia

The future of any profession relies on education and training; education for a new and emerging workforce and ongoing training for the existing workforce. The first diploma course in speech therapy was established at the University of Queensland and the curriculum was developed by Elizabeth Usher in 1961. For many decades a small number of programs commenced, and speech therapists graduated from universities located in capital cities. In the mid-90s additional university degrees emerged in regional areas and the graduate entry masters’ programs were established. University curriculum and clinical education evolved, and SPA commenced formal accreditation of all speech-language pathology university training programs. However, the biggest changes in speech-language pathology training have occurred with the establishment of new training programs, which have grown exponentially in the past few years. See for a summary of speech-language pathology training program development in Australia.

Table II. A summary of key developments in speech-language pathology training programs in Australia.

Currently, the SPA website lists 38 university professional degree programs, three new programs commencing intake from 2022, and extending training programs to every state and territory in Australia.

So, in Australia, with a population of ∼25.5 million people, there are more than 11 000 speech-language pathologists, and the growth of the profession is supported by at least 35 professional degree programs and from 2022, will be offered by universities located in every state and territory of Australia. Whilst this change is a challenge (especially for clinical education) it is also important for employment growth in Australia and to support the development of the profession in the majority of world countries. The occupational projections for speech-language pathologists/audiologists expect an increase of 24.5% between May 2019 and May 2024. And, alongside physiotherapy (at 24.6%), speech-language pathology/audiology is the highest projected growth occupation in health/medicine in Australia (data retrieved from https://lmip.gov.au/default.aspx?LMIP/EmploymentProjections). However, internationally, the statistics are quite different.

In the USA, the numbers are different, but the ratios are similar. The USA has a population of ∼331 million people, and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) website reports more than 200 000 members. To support an expected occupational growth of 29% by 2030 (U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics, Citation2022), more than 270 colleges offer degrees in speech-language pathology (ASHA, Citationn.d.). However, both the numbers and ratios are drastically different when compared to the majority of world countries like Vietnam and China. Vietnam has an estimated population of 91.1 million and currently, there are just 66 Vietnamese trained speech therapists and three university training programs (Nguyen, McAllister, Hewat, & Woodward, Citation2017). China has a population of 1.44 billion people and an estimated 10 000 therapists but no formal speech-language pathology university training programs (Lin et al., Citation2016; Hao et al., Citation2015).

So, whilst in the USA, the UK, and Australia there is one speech-language pathologist for ∼2500–5000 people, in the majority of world countries, like Vietnam and China there is only one speech-language pathologist for every 1.3 million or more people. Vietnam and China are just two examples, what is clearly evident, is the world needs speech-language pathologists.

Valuing connectivity for the development of the profession worldwide

Speech-language pathology in the transformative era is certainly different from what it was 60, 40, or even 20 years ago, and in the past 2 years, the global pandemic has reinforced the importance of connectivity. Change and transformation of the profession come from us—individuals, speech-language pathologists, clinicians, educators, researchers, advocates, and entrepreneurs. I believe that if we value connectivity our skills, hopes, visions, and passions will drive change in education, clinical practice, and research to support people with communication and swallowing disabilities globally.

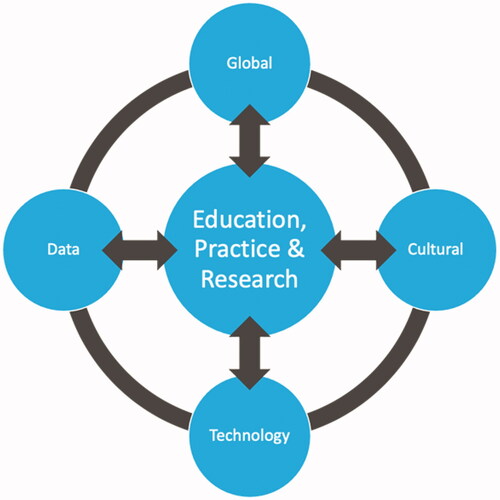

below provides a framework for the following discussion. Examples from my work will be used to illustrate how global and cultural practices and connections with technology and data have influenced and shaped my work practices in my local context. In sharing these stories, I hope to challenge readers to consider the disruption, change, challenges, and opportunities that our profession in Australia faces with:

globalisation and the development of the profession in the majority of world countries

our genuine commitment to supporting the health and well-being of indigenous Australia, and

rapid advances in technology and “big data”.

Global connections

There is no doubt that global connections lead to enhanced knowledge, skills, (challenges) and opportunities. Eighty years ago, the profession in Australia emerged with knowledge and skills brought across from United Kingdom post-World War II. Today, the ability to connect (easier and faster) and the rapid development of the speech-language pathology profession in the majority of world countries have and will continue to influence education, clinical practice, and research locally. Experiences working in global contexts, namely Vietnam and China, have profoundly impacted me, personally and professionally.

Connecting with Vietnam

Trinh Foundation Australia (TFA) was established in 2009 to support and coordinate Vietnam’s only speech therapy course which commenced in September 2010 in partnership with Pham Ngoc Thach University (PNTU) in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. TFA was initially a small group of volunteer speech-language pathologists and professionals from Australia who worked together with other volunteers to raise funds, coordinate activities, and support the development of speech therapy in Vietnam (see https://trinhfoundation.org for further details). In 2011, I was invited to teach an intensive course in stuttering as part of the first training program at PNTU and 12 months later, I continued working with TFA, staff, and students in Vietnam as part of a special study program supported by the University of Newcastle (UON). Five months living and working in Vietnam provided the opportunity to develop relationships, share research, clinical skills, and knowledge with colleagues in Vietnam, and establish partnerships—global connections. The engagement with TFA and various other organisations in Vietnam led to the integration of an international and intercultural stream within the speech-language pathology program at the UON.

These global connections led to the development of the NUSpeech model for international clinical placements (Hewat, Walters, Wenger, Laurence, & Webb, Citation2017). The impact and outcomes of NUSpeech for all stakeholders have been disseminated widely (Church & Hewat, Citation2015; Hewat, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Hewat, Unicomb, Dean, & Cui, Citation2018; Hewat, Walters, & Baldac, Citation2015; Hewat, Walters, & Wenger, Citation2016; Jitts, Citation2016).and the contribution to teaching and learning recognised with Dean’s Award for Teaching Excellence. To provide equitable learning opportunities and enable sustainability of the international placement program, $400 000 funding has been secured from Department of Foreign Affairs & Trading, New Colombo Plan to support outbound student mobility (see https://www.dfat.gov.au/people-to-people/new-colombo-plan for further details). Since 2012, 64 final year speech-language pathology students and 10 different faculty staff have been involved in clinical placements with 14 partner organisations in Vietnam, Singapore, Nepal, China, and Fiji. Interestingly, despite the impact of the global pandemic on international travel, the need hasn’t changed but technology has enabled international engagement opportunities to continue. Students can complete virtual placements and internships, with opportunities in countries throughout the Asia Pacific.

Essential to the success of the NUSpeech was the development and implementation of an international Stream embedded in the speech-language pathology curriculum at UON. The learning stream for students comprises an international clinical placement and completion of a directed elective course that explores different cultural understandings and conceptualisation of health and illness as well as speech-language pathology practices in developed and developing countries. Therefore, providing students with a platform to foster transformational learning and enable students to develop a deeper awareness and understanding of themselves, their beliefs, values, and how these interact and impact their experiences and clinical practice. As part of the course, students also undertake an individual learning project in collaboration with international partner organisations. In many instances, student projects evolve into practical resources, activities, and publications enabling further engagement and impact. For example, students have produced a promotional video, an online publication for the International Communication Project, a keyword sign instructional video in Vietnamese, and fact sheets about speech and language therapy and communication disability. This example reinforces the value of global connections to support innovative development in clinical education and curriculum development—as well as clinical practice internationally.

Since 2012, academics and speech-language pathologists in Australia have provided workshops, clinical expert sessions, and seminars to support the ongoing development of the graduates of the speech therapy program in Vietnam. In 2018 pre-COVID, TFA, with the support of a SPA Working with Developing and Under-served Communities grant, piloted the Beyond Borders Mentoring Program (BBMP). The BBMP was based on some initial research supporting the effectiveness of an online mentoring model used in physiotherapy (Westervelt et al., Citation2018) as well as the convenience and cost-benefits of electronic mentoring (Mahayosnand, Citation2000). Following the initial pilot program, the BBMP has successfully been provided each successive year. So, even in a COVID world, as individuals and a profession, we can still connect globally to support the development of the profession abroad. The outcomes of the BBMP are currently being formally evaluated and preliminary research related to the mentors’ experience was presented at the SPA virtual conference. Interestingly, the mentors highlighted how participation in the program and connecting with international colleagues led to changes in their own practice in Australia (Day, Hewat, & Webb, Citation2021). Notably, the vast array of presentations delivered at the virtual conference showcases the extent of global connectivity of our profession that will enable and support future growth and innovations in clinical practice and research.

Ten years on from my first visit to Vietnam, Dr. Le Khan Dien, one of the pioneers of SALT in Vietnam, recently completed his research doctorate where he undertook an extraordinary program of research to develop and validate an assessment for people with aphasia in Vietnam—The Vietnamese Aphasia Test. So, in response to another presentation facilitated by Wylie et al. (Citation2021) at the virtual conference, yes, it really does take ten years to create sustainable global partnerships.

Connecting with China

Early in 2015, I was contacted directly by the chief executive officer and president of a rapidly growing private speech therapy business, Orient Speech Therapy, in China. The connection was made through the chair of the Australian Business Chamber in Beijing. After a series of conversations online, I was asked if I could support the company to develop speech therapy services and training. As you will recall, China currently doesn’t have any formal speech-language pathology university programs, but an enormous need for speech therapists and speech therapy services. During this same period, I was engaging in a lot of personal development and self-reflection, drawing on thought leaders and global entrepreneurs. Perhaps it wasn’t a conscious thought at the time, but reflecting now, I know Richard Branson influenced my answer. I recall Branson’s response to transformation and innovation, “just say YES and work out how to do it later”. So, I said, “yes”, and in June 2015 travelled to China, and over the next few years, developed a speech therapy curriculum for the industry partner with existing links to universities and government regulatory boards. The curricula development was a reiterative process that emerged from intensive workshopping with local stakeholders with careful consideration of the company needs (growth, staffing, and clinical priorities), population needs, existing higher education programs, entry pathways, accessibility to learning, local context and learning culture, opportunities for future education for career development as well as international standards in speech therapy training and availability of resources to develop and deliver the courses.

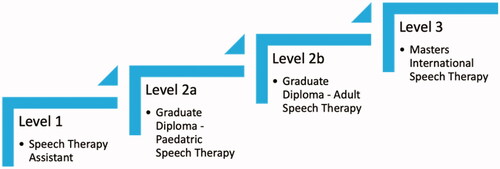

The proposed three-level stepped curricula were based on the UON program structure and aligned to Australian Qualification Framework standards (Australian Government Department of Education, Skills & Employment, Citation2019). The curricula include credit for learning from previous levels and offered a paediatric or adult specialisation to support faster workforce growth for specific workplaces. Level 3, Master of International Speech Therapy, is aligned to international professional standards. See below.

The speech therapy assistant training program (level 1) is mapped to international allied health (speech therapy) assistant standards and draws on course material and assessment processes at the UON. The program utilises a blended learning curriculum, whereby 60% of the content is delivered online in China through the company's internal training platform, which is supplemented by residential workshops (20%) and supervised work-based placements (20%). A key innovation of the program is the 13 discrete learning modules that together form the equivalent of four UON courses and completion of level 1 is recognised as credit-bearing for two elective courses in the bachelor's degree at UON through a learning validation process. The UON provides mentoring and consultation services to maintain quality standards. Following the development of the curricula roadmap, the content and delivery of the Level 1 program commenced and was endorsed by the UON following a rigorous quality audit process. The first cohort of 100 students completed the speech therapy assistant training course in China in 2019 and work is currently underway, through a collaboration between the industry and universities in Beijing, to further develop the level 2 and 3 curricula.

The innovative curricula developed in collaboration with an industry partner is an interesting concept for future development of the profession globally as “micro-credentialing” emerges in the higher education sector and business communities worldwide (Australia Government, Department of Education, Skills & Employment, Citation2021). There is certainly a belief that micro-credentials provide the best opportunity for future skill and knowledge development for a workforce transforming at a rapid pace.

Valuing the international collaborations and connection, the internationalisation of the speech-language pathology curriculum and the NUSpeech model for international clinical placements both provided yet another opportunity for the transformation of students learning. In 2019, supported by the industry partner and UON, the first clinical internship for speech-language pathology students was offered in China. Four international students, two originally from Malaysia, one from Singapore, and one from Hong Kong completed 4 weeks of clinical internship placement in Shenzhen, China. All students were fluent in either Cantonese or simplified Mandarin as well as English and had the opportunity to deliver speech-language pathology practices in both languages. This is an unprecedented opportunity that enabled the students to develop skills and competencies for future practice in other languages and cultures similar to their home countries or within multi-lingual communities here in Australia.

Engaging in a program of research in partnership with colleagues in China was the natural progression and following the successful implementation and evaluation of treatment for early stuttering in China, a community of practice for stuttering in the Asia Pacific region was established in 2021. The community of practice now includes colleagues from China, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Australia.

Cultural connections

Ten years ago, TFA approached me to support the delivery of an education program in Vietnam and six years ago, Orient Speech Therapy approached me to support the development of speech therapy practices and education in China. One year ago, amidst the pandemic, lock downs, and restricted travel, the University of Newcastle was approached by a representative of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community to see if speech-language pathology students could undertake clinical placements in Kempsey to address the “speech issues” of children at an Aboriginal pre-school. My initial thought was “we need to do this”, whilst here in Australia we have one speech-language pathologist for every 2500 people, we still have many underserved communities. My second thought was “I want to make this happen”, to genuinely do whatever my role, skills, and experiences can contribute to improving the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. And, my third thought was “we said we would do this”, in 2019 as a profession we said “sorry” and committed to working closely with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to improve communication and swallowing difficulties. And, of course, I said—yes! I knew if we could be culturally responsive and develop partnerships that focus on capacity building and sustainability with international communities, then we could do the same in Australia.

Although only a very new partnership, this example highlights the importance of cultural connections and demonstrates how global connections can be influenced and enhanced work in local contexts. In April 2021, the Guyati, Garraka wa Witing Speech Pathology Project was established. Guyati Garraka wa Witing means Talk, Mouth, and Lips in Dunghutti language, a name that was gifted by community elders. The project was enabled through a partnership between Gunnawirra, Dailgur and Scribbly Gums pre-schools and the community in Kempsey, the UON, and a benefactor, the Vonwiller Foundation (University of Newcastle, Citation2021). Students are supported by scholarships to complete final year clinical placements at the preschools in Kempsey. The education practices are similar but the opportunity to apply concepts, knowledge, and skills in practice is different, with a focus on Indigenous cultural learning, safety, and responsiveness. The development and nurturing of the partnerships and cultural connections have provided the opportunity to embed genuine Indigenous learning in the curriculum. In this example, change was necessary and driven by the community, societal, and government needs but it was also the SPA Reconciliation Action Plan (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2017), and apology to Aboriginal and Torres Islander peoples (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2019) that led to further innovations in education and practice.

At UON we have been working towards indigenisation of our curriculum, we have also supported Aboriginal and Torres Islander students to enroll in and continue studies in the bachelor of speech-language pathology program. Currently, 17 Aboriginal and Torres Islander students are enrolled in the Bachelor of Speech Pathology (hons) and the first-ever scholarship was recently awarded to an Aboriginal and Torres Islander student to provide additional support to complete the degree.

Connecting with technology and data

Connecting with the world and connecting with culture (maintaining and nurturing these connections) has only been possible, particularly through the pandemic, with the support of technology and data. However, where are we heading next? What might the future look like?

In modern civilisation, we have experienced multiple industrial revolutions and technological developments from steam technology to motor vehicles to personal computers, tablets, and smartphones. All of these innovations changed how we lived and how we connected, as a society. Undoubtedly, the technology revolution of the transformative era can make lives better if we understand the power of data and the possibilities of innovations. According to the World Economic Forum, there will be significant technological advancements called “tipping points” in the next four years (Yoon, Citation2020). By 2025, it is predicted that

1 trillion devices will be connected to the internet

every individual will have eight connections to the internet

3D liver transplants will be possible, and

driverless cars will make up 10% of all vehicles on roads in the USA.

Transforming education, research, and practice

Education and development for a global speech-language pathology workforce is my passion. So, where are the opportunities? How are education, research, and practice transforming? and What are the challenges for our profession in the future?

In Australia, graduates can work as a speech-language pathologists after completing an accredited bachelor, or bachelor honours, or graduate entry master degree program (SPA, Citationn.d.). Internationally, allied health assistant degrees (some specialised in speech therapy) are available and in many majority of world countries, short courses in paediatric or adult speech therapy degrees are emerging. There is also the possibility of a 3-level stepped curriculum developing in China and opportunities for micro-credentialing.

Education is already transforming how we deliver teaching and learning. There are already many different curricula and different delivery modes used in universities throughout Australia, including transitional pedagogies like the 3SL Scaffolding student success in Learning (O’Donnell, Wallace, Melano, Lawson, & Leinonen, Citation2015; Unicomb, Walters, Hewat, Spencer, & Webb, Citation2019), distance learning and residential schools (McCormack, Easton, & Morkel-Kingsbury, Citation2014). If you google “online speech-language pathology degrees” today, you’ll find five different programs available online in Australia and 17 in the USA. Blended, online, and digital learning, synchronous and asynchronous learning are now commonplace in a university environment. However, still emerging is a shift towards free massive open online courses (https://www.mooc.org) and transnational education (Henderson, Barnett, & Barrett, Citation2017). That is, a university education program that may be delivered across two (or more) countries, 2 years in one country and 2 years in another, or delivered in one country but endorsed with the quality assurance provided by a university in a different country. So, the mode of delivery, when and how courses and programs are delivered is rapidly changing.

The content of any curriculum needs to be contemporary, meet the needs of the speech-language pathology profession and also ensure graduates have the knowledge, skills, and competencies to meet future workforce demands. Students enroll in bachelor's degree programs for four years, but in the transformative era, a lot can change in that period of time alone. Content should also account for the changing demographics of the population (including globalisation and ageing), as well as ensure graduates can support the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in culturally safe and responsive ways. In Australia, the National Disability Insurance Scheme, and certainly worldwide the increasing recognition and focus on supporting people with disability, neurodiversity, and Autism are notable. Speech-language pathology worldwide is an ever-changing and expanding scope of practice (Ward, Citation2019) and curriculum developers need to be cognisant of these changes. The workforce, how we work, and who we work with are also evolving with the emergence of allied health assistants. Additionally, the new professional standards (SPA, Citation2020b) will have a profound influence on the content and structure of the speech-language pathology curriculum in the coming years. Graduates need to have the knowledge skills and competencies to use and apply existing and new technology and innovations in research and practice. In speech-language pathology, in Australia, we are emerging in the private sector; comparatively in China, where there are limited public speech-language pathology services available, the private sector offers the fastest growth opportunity.

Essential to any speech-language pathology curriculum is clinical education, or what is often referred to as work-integrated learning (WIL). The 2018 Clinical Education in Australia report (SPA, 2018) identified ways to explore with members of the profession innovative clinical education opportunities. Only three years ago, speech-language pathologists in Australia discussed scenarios for new ways of providing clinical education, including a peer-supervision learning model with a final year student as the supervisor, tele-supervision, project-based placements, and simulation. The private sector was identified as a future opportunity for clinical education. These are all innovative to a degree, however not innovative enough in this transformative age of disruption. It is certainly evident that Simulation-based Learning (Hewat et al., Citation2020; Hill et al., Citation2020; Penman, Hill, Hewat, & Scarinci, Citation2020) will provide a significant proportion of work integrated learning opportunities in university programs. Telehealth and tele-supervision, particularly with the transformation we have seen in the past 2 years of the COVID pandemic, are also now commonplace in clinical practice and clinical education. However, virtual reality (Bryant, Brunner, & Hemsley, Citation2020) and avatars (Beilby, Citationn.d.) are emerging. The use of virtual reality allows users to learn by hearing, seeing, and interacting. Students in virtual reality are immersed in learning and this arguably reduces cognitive lead and enhances motivation. At the University of Newcastle in New South Wales, virtual reality has been used to teach students how to conduct an oromusculature assessment with young children (Start Beyond, Citationn.d.), and at Curtin University in Western Australia, an avatar “Jim” has been used to support student training across many health disciplines in relation to empathy (Beilby, Citationn.d.). So, clinical education is shifting rapidly in this transformative era.

So, here are the challenges:

When will speech therapy assistants become part of our profession?

Will micro credentialing form part of our training in the future?

Can all learning occur online?

Does content of curriculum match SPA visions for future?

How do we fit everything in?

Will the profession accept simulation, avatars and virtual reality as primary means of clinical education?

How will universities and the profession respond to the new professional standards?

Technology and data transform clinical practice and research drives changes in clinical practice but arguably sometimes not fast enough. In a transformative era—with global and cultural influences and rapid advances in technology and the emergence of big data—we need to respond, change, or adapt as we have throughout the 2020–2021 global pandemic.

In my travels globally and in researching for this lecture, I’ve seen and explored many novel and innovative approaches and advances in clinical practice. I’ve seen the emergence of global speech therapy, where speech-language pathologists in one country are providing services and support for individuals in another country. I’ve also seen telepractice emerge and grow at a rapid rate. One of the largest teletherapy firms in the USA is a publicly listed company with a network of over 2000 health practitioners including speech-language pathologists (https://www.presencelearning.com). The use of virtual reality, augmented reality, and extended reality in practice is also emerging (e.g. Vaezipour, Aldridge, Koenig, Theodoros, & Russell, Citation2021), along with 3D printed food and dysphagia management (e.g. Hemsley, Palmer, Kouzani, Adams, & Balandin, Citation2019). The use of robotics to support people with complex communication needs is not new (Pennisi et al., Citation2016), but the technology is changing at a rapid pace. Voice banks are available for people with progressive diseases that impact communication (Yamagishi, Veaux, King, & Renals, Citation2012). However, the biggest potential influence on clinical practice and research are in artificial intelligence and “big data” (Tal, Citation2020). Data is collected from all of the billions and trillions of connections over the internet, each and every day, capturing information that will feed into advances and innovation in the future. So, here are the challenges:

Can helping professions, like speech-language pathology, be automated?

Will technology and data change the nature of our workforce?

What impact will “big data” have on our practices?

Will text overtake talk?

When will technology, research and clinical practice from majority world countries start to influence our research and practices?

Conclusion

As a profession, we are moving forward. Teaching and learning practice is changing and innovative. The profession's response to the disruption of the pandemic transformed how, when, and where we work. Assessment and treatment practices moved online and telehealth was accepted by the speech-language pathology profession and the community. Professional development opportunities increased with podcasts, synchronous and asynchronous virtual meetings, and education platforms, and in 2021 SPA hosted a virtual national conference. Online education became part of the norm, rather than the exception or novelty. Meetings and conferences have virtual solutions and we are valuing and embracing these new ways of working.

So, in this transformative era of rapid change, we’ve shown that we can adapt and change practice, and we’ve also learned that disruption creates opportunities. The COVID pandemic disrupted practice and shifted service delivery to telehealth in a 12-month period, and innovation we heard about 10 years ago! Let’s not wait 10 years for another external event to trigger change, instead, look for opportunities that might create or enable change. For me, the opportunities came through global and cultural connections, through looking at technology, and through thinking about the data that is collected every minute of every day. I challenge you and the profession to also value connectivity and embrace transformation.

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aggarwal, M. (n.d.). History of the industrial revolution. Retrieved from https://www.historydiscussion.net/history/industrial-revolution/history-of-the-industrial-revolution/1784

- American Speech and Hearing Association. (n.d.). Planning your education in CSD. Retrieved from https://www.asha.org/Students/Planning-Your-Education-in-CSD/

- Australia Government, Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2021). Supporting micro-credentials in the training system. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/skills-reform/skills-reform-overview/supporting-microcredentials-training-system

- Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2019). Review of the Australian qualifications framework final report 2019. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-reviews-and-consultations/resources/review-australian-qualifications-framework-final-report-2019

- Australian Government. (n.d.). Labour market information portal. Retrieved from https://lmip.gov.au/default.aspx?LMIP/EmploymentProjections

- Beilby, J. (n.d.). The empathy simulator – Communication training in a virtual learning environment. Retrieved from https://acen.edu.au/innovative-models/project/the-empathy-simulator-communication-training-in-a-virtual-learning-environment/

- Bryant, L., Brunner, M., & Hemsley, B. (2020). A review of virtual reality technologies in the field of communication disability: implications for practice and research. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 15, 365–372. doi:10.1080/17483107.2018.1549276

- Church, E., & Hewat, S. (2015). An exploration of student’s perspectives and experiences of the South East Asia learning stream. Paper presented at APEC-SLP, Guangzhou, China.

- Day, S., Hewat, S., & Webb, G. (2021). Impact of a cross-cultural, cross-continental online mentoring program for recently graduated speech-language therapists (SLTs) in a majority world country. Paper presented at the Speech Pathology Australia National Virtual Conference, Online.

- Hao, G., Mccrea, E., Mcneilly, L., & Wang, R. (2015). CISHA: The history and development of the Chinese International Speech, Language and Hearing Association. Perspectives on Global Issues in Communication Sciences and Related Disorders, 5, 12–20. doi:10.1044/gics5.1.12

- Hemsley, B., Palmer, S., Kouzani, A., Adams, S., & Balandin, S. (2019). Review informing the design of 3D food printing for people with swallowing disorders: constructive, conceptual, and empirical problems, In HICSS 52: Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 5735–5744). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i at Manoa. doi:10.24251/HICSS.2019.692

- Henderson, M., Barnett, R., & Barrett, H. (2017). New developments in transnational education and the challenges for higher education professional staff. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 21, 11–19. doi:10.1080/13603108.2016.1203366

- Hewat, S. (2015a). Curriculum development in speech pathology: International stream. Paper presented at Asia Pacific Educators Collaboration in Speech Pathology Meeting, Guangzhou, China.

- Hewat, S. (2015b). Curriculum development in speech pathology for ‘global graduate attributes’. Paper presented at the QS APPLE Conference, Melbourne, VIC.

- Hewat, S., Penman, A., Davidson, B., Baldac, S., Howells, S., Walters, J., … Hill, A. (2020). A framework to support the development of quality simulation-based learning programmes in speech-language pathology. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 55, 287–300. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12515

- Hewat, S., Unicomb, R., Dean, I., & Cui, G. (2018). Treatment of childhood stuttering using the Lidcombe program in mainland China: Case studies. Speech, Language & Hearing, 23, 55–65. doi:10.1080/2050571X.2018.1511106

- Hewat, S., Walters, J., & Baldac, S. (2015). Work readiness: The global speech language pathologist. Facilitated Roundtable discussion presented at APEC-SLP, Guangzhou, China.

- Hewat, S., Walters, J., & Wenger, T. (2016). Assessable international clinical placements: Students’ perceptions. Paper presented at the Speech Pathology Australia National Conference, Perth, WA.

- Hewat, S., Walters, J., Wenger, T., Laurence, A., & Webb, G.L. (2017). NUSpeech: A model for international clinical placements in speech-language pathology. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 19, 157–162.

- Hill, A.E., Ward, E.C., Heard, R., McAllister, S., McCabe, P., Penman, A., … Walters, J. (2020). Simulation can replace part of speech-language pathology placement time: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 23, 92–102. doi:10.1080/17549507.2020.1722238

- Jitts, C. (2016). Speech pathology in Vietnam: A student’s perspective. Speakout, August, 33.

- Lin, Q., Lu, J., Chen, Z., Yan, J., Wang, H., Ouyang, H., … O'Young, B. (2016). A survey of speech-language-hearing therapists' career situation and challenges in mainland China. Folia Phoniatrics Logopaedics, 68, 10–15. doi:10.1159/000442284

- Mahayosnand, P.P. (2000). Public health E-mentoring: An investment for the next millennium. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 1317–1318.

- Marr, B. (n.d.). What really is the 4th industrial revolution and what does it mean for you. Retrieved from https://bernardmarr.com/what-really-is-the-4th-industrial-revolution-and-what-does-it-mean-for-you/

- McCormack, J., Easton, C., & Morkel-Kingsbury, L. (2014). Educating speech-language pathologists for the 21st century: Course design considerations for a distance education Master of Speech Pathology program. Folia Phoniatrics Logopaedics, 66, 147–157. doi:10.1159/000367710

- Nguyen, T.N.D., McAllister, L., Hewat, S., & Woodward, S. (2017). A successful partnership for the development of speech and language therapy education in southern Vietnam. Vietnam Medical Journal, 160–167.

- O’Donnell, M., Wallace, M., Melano, A., Lawson, R., & Leinonen, E. (2015). Putting transition at the centre of whole-of-curriculum transformation. Student Success, 6, 73–79. doi:10.5204/ssj.v6i2.295

- Penman, A., Hill, A., Hewat, S., & Scarinci, N. (2020). “I felt more prepared and ready for clinic”: Connections in student and clinical educator views about simulation-based learning. Australian Journal of Clinical Education, 7, 1–21. doi:10.53300/001c.17204

- Pennisi, P., Tonacci, A., Tartarisco, G., Billeci, L., Ruta, L., Gangemi, S., & Pioggia, G. (2016). Autism and social robotics: A systematic review. Autism Research, 9, 165–183. doi:10.1002/aur.1527

- Schwab, K. (2016). The 4th industrial revolution: What it means, how to respond. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/

- Speech Pathology Australia. (n.d.). University accreditation. Retrieved from https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Resources_for_the_Public/University_Programs/University_Accreditation/SPAweb/Resources_for_the_Public/University_Programs/Accreditation.aspx?hkey=3ebeb9e4-8ea4-48dc-8df9-b0d1706d6132

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2016). Speech Pathology 2030 - making futures happen. Melbourne: Author. Retrieved from https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/whats_on/Speech_Pathology_2030/SPAweb/What_s_On/SP2030/Speech_Pathology_2030.aspx?hkey=3fad1937-a20e-4411-8b46-369f61570456

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2017). Reconciliation action plan. Retrieved from https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/About_us/Reconciliation/Reconciliation_Action_Plan_-_Innovate/SPAweb/About_Us/Reconciliation/RAP-Innovate.aspx?hkey=fbdb991a-9a1d-4ab3-a4c9-33f01b3ee22f

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2019). Apology to aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Retrieved from https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/About_us/Reconciliation/Formal_Apology/SPAweb/About_Us/Reconciliation/Apology.aspx?hkey=dfd8894c-0a41-428b-a243-0c3fe349210b

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2020a). Speech Pathology Australia code of ethics 2020. Retrieved from https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Members/Ethics/Code_of_Ethics_2020/SPAweb/Members/Ethics/HTML/Code_of_Ethics_2020.aspx?hkey=a9b5df85-282d-4ba9-981a-61345c399688

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2020b). Professional standards for speech pathologists in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Resources_For_Speech_Pathologists/Professional_Standards/SPAweb/Resources_for_Speech_Pathologists/CBOS/Introducing_the_Professional_Standards.aspx?hkey=a8b8e90f-a645-44d7-868a-061f96e0d3d3

- Start Beyond. (n.d.). Speech pathology VR: The University of Newcastle. Retrieved from https://www.startbeyond.co/case-studies/voma-speech-pathology-vr

- Tal, D. (2020). How the first artificial general intelligence will change society: Future of artificial intelligence P2. Retrieved from https://www.quantumrun.com/prediction/first-artificial-general-intelligence-society-future

- Theodoros, D. (2012). A new era in speech-language pathology practice: Innovation and diversification. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14, 189–199. doi:10.3109/17549507.2011.639390

- U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics. (2022). Occupational outlook handbook. Speech-Language Pathologists. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/speech-language-pathologists.htm

- Unicomb, R., Walters, J., Hewat, S., Spencer, E., & Webb, G. (2019). Scaffolding for student success in learning (3SL): A framework for teaching and learning in speech pathology. Poster presented at the Speech Pathology Australia National Conference, Brisbane.

- University of Newcastle. (2021). University of Newcastle partnering to close the gap. Retrieved from https://www.newcastle.edu.au/newsroom/community-and-alumni/university-of-newcastle-partnering-to-close-the-gap

- Vaezipour, A., Aldridge, D., Koenig, S., Theodoros, D., & Russell, T. (2021). “It’s really exciting to think where it could go”: a mixed-method investigation of clinician acceptance, barriers and enablers of virtual reality technology in communication rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation,14, 1–13. doi:10.1080/09638288.2021.1895333

- Ward, E.C. (2019). Elizabeth Usher memorial lecture: Expanding scope of practice - inspiring practice change and raising new considerations. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21, 228–239. doi:10.1080/17549507.2019.1572224

- Westervelt, K., Hing, W., Mcgovern, M., Banks, L., Carney, C., Kunker, K., … Crane, L. (2018). An online model of international clinical mentoring for novice physical therapists. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 26, 170–180. doi:10.1080/10669817.2018.1447789

- Wylie, K., Owusu, N., Staley, B., Gibson, R., Rochus, D., Roman, R, Chafcouloff, E., and Bortz, M. (2021). Does it really take ten years? Creating sustainable global partnerships. Workshop presented at the Speech Pathology Australia National Virtual Conference, Online.

- Yamagishi, J., Veaux, C., King, S., & Renals, S. (2012). Speech synthesis technologies for individuals with vocal disabilities: Voice banking and reconstruction. Acoustical Science & Technology, 33, 1–5. doi:10.1250/ast.33.1

- Yoon, S. (2020). 17 Ways technology could change the world by 2025. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/17-predictions-for-our-world-in-2025/