Abstract

Purpose: Improving language and literacy skills in preschoolers can lead to better life outcomes. One way speech-language pathologists (SLPs) can improve these skills in preschoolers is by supporting educators through professional development (PD). However, PD in early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings is a complex intervention. To improve preschoolers' language and literacy skills using PD, SLPs must first work with educators to change or increase educators' language and literacy-promoting behaviours. This paper aimed to describe educator behaviours and preschooler skills following a real-world language and literacy PD intervention facilitated by two community SLPs.

Method: Two pragmatic studies were conducted across four ECEC centres: (1) an observation study of 13 educators' self-reported language and literacy promoting behaviours, and (2) a non-randomised controlled trial investigating the language and literacy skills of 82 preschoolers as reported by their educators and parents/carers.

Result: After the intervention, educators rated themselves as performing language and literacy-promoting behaviours more frequently. Educators also rated the early reading skills of preschoolers more highly after the PD intervention, but not preschoolers' oral language or early writing skills. Parents/carers did not report any significant improvements in preschoolers' skills.

Conclusion: PD as an SLP intervention, whilst promising, showed mixed outcomes. Educator outcomes improved; however, preschooler outcomes were varied.

Introduction

Strong language and early literacy skills in the pre-school years impact future life outcomes (e.g. Snow, Citation2016). However, many Australian children do not have the prerequisite language and early literacy skills needed to begin formal schooling (Smith et al., Citation2021). In 2015, the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) indicated that around 15% of Australian children had developmentally “at risk” or “vulnerable” language and communication skills upon entry to formal schooling (Commonwealth Department of Education & Training, Citation2016). Consequently, methods to improve language and literacy skills in preschoolers need to be investigated.

High-quality early childhood education and care settings and child outcomes

One evidence-informed method that improves language and early literacy outcomes in preschoolers is high-quality early childhood education and care (ECEC) (Burchinal et al., Citation2008). To increase preschoolers' skills, ECEC settings must provide high levels of educator-child verbal interactions and intentional teachingFootnote1 of language and early literacy skills. Unfortunately, Australian ECEC settings predominantly deliver low levels of both and change is therefore required (Tayler, Citation2017). Such improvements should include increasing the verbal interactions and intentional teaching of language and emergent literacy skills provided by educators.

Professional development to improve language and literacy skills in children

Professional development (PD) is one way to improve educators’ verbal interactions and intentional teaching of language and early literacy skills. It is therefore a potentially useful intervention to consider. However, research investigating language and literacy-based PD provides mixed evidence for improved educator and child outcomes (e.g. Markussen-Brown et al., Citation2017). For example, a randomised controlled trial of a vocabulary-focussed PD delivered over a school year showed that educators used more intentional teaching strategies such as highlighting vocabulary and providing meaningful feedback to children following the intervention (Wasik & Hindman, Citation2020). Furthermore, children from the intervention condition learned more words and significantly improved on standardised measures of receptive and expressive vocabularyFootnote2 (Wasik & Hindman, Citation2020). In contrast, Pianta et al. (Citation2017) reported that their language and literacy PD interventions had no effects on children's language and literacy skills despite significant positive effects on educators' interactions with preschoolers.

PD as a complex intervention: the twin black boxes model

Complex interventions have multiple interrelated components (Craig et al., Citation2019). PD for educators is a complex intervention as it relies on two consecutive complex and interacting components to be successful (1) a positive change in practice for educators receiving the PD and (2) a subsequent positive change in children's learning outcomes (Dunst, Citation2015).

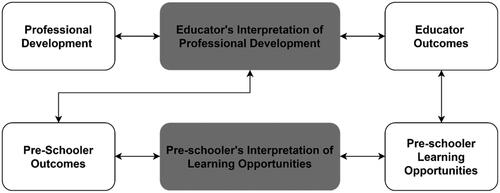

Timperley et al.’s (Citation2007) twin black boxes model is useful to conceptualise the complexity of PD. Following PD input, participating educators interpret and use new information and skills differently. A black box between PD input and educator change represents the educators' interpretation. The term “black box” references the idea that the educators' interpretation is not understood well, i.e. PD input does not necessarily result in the expected educator outcomes. Similarly, there is a second black box between child learning opportunities following educators' PD and subsequent child outcomes changes. This black box represents the largely unknown way a child interprets their learning opportunities.

Timperley et al.'s black boxes model was originally applied to school-based PD; however, we propose it also captures the challenges in ECEC settings. Therefore, we have modified Timperley et al.'s black boxes model to illustrate PD in ECEC settings in . Modifications included changing the terminology to reflect ECEC and an added arrow between preschooler outcomes and educators' interpretation of PD to formalise the relationship between changes in child outcomes and changes in educators' attitudes and beliefs which may influence their interpretation of PD (Dunst, Citation2015; Timperley, Wilson, Barrar, & Fung, Citation2007).

Figure 1. Modified version of Timperley et al.'s (Citation2007) black boxes model. Note: For this figure and subsequent figures, the changes from Timperley et al. (Citation2007) include words in the boxes, directionality of arrows, font and colour changes.

Evaluating professional development

Complex interventions require evaluation of their various interacting components (Craig et al., Citation2019). In PD, this translates to evaluating both educator change in promoting a targeted skill and the child's target skill (Schachter, Citation2015). Despite the importance of evaluating educator and child outcomes to determine if a PD intervention is effective, the literature around language and literacy PD in ECEC settings frequently evaluates only educator or child outcomes, seldom both (Schachter, Citation2015). Difficulty, expense, and feasibility are the hypothesised reasons why PD research may not include educator and child outcomes (Schachter, Citation2015). However, given PD is a recommended practice in Australia (Renshaw & Goodhue, Citation2020), it is important to evaluate educator and child outcomes to understand if these PD interventions are effective.

Pragmatic studies often evaluate complex interventions (Ford & Norrie, Citation2016). An important aspect of evaluating a complex intervention is considering if the intervention works in real-world everyday practices (Craig et al., Citation2019), and pragmatic studies can achieve this (Schliep, Alonzo, & Morris, Citation2017). In a pragmatic study, evaluation is completed by those most familiar with the target population and intervention (Berwick, Citation2005). Therefore, outcome measures should be collected using tools that can be incorporated into routine clinical practice (Glasgow & Riley, Citation2013).

Evaluation of educators: the first black box

Although educator outcomes are incorporated in most ECEC PD intervention studies, how they are best collected is still unclear. There are two main ways educator change is measured after PD: observation or self-assessment. Observational measures are mainly used, however Australian educators want their skills acknowledged before PD (Brebner, Attrill, Marsh, & Coles, Citation2017), which can be achieved with self-assessment.

Self-assessment encourages reflection and transparency, which are empowering to educators (Escamilla & Meier, Citation2018). Escamilla and Meier (Citation2018) argued that self-reflection is an important tool in supporting educators' meaningful and effective change. Further, educators who participate in self-assessment are more likely to change their practice (Buysse, Castro, & Peisner-Feinberg, Citation2010).

Evaluation of children: the second black box

Evaluation of children can be done using direct or indirect assessments. Direct assessments are useful because they are less prone to bias than indirect assessments (Schachter, Citation2015). The limitations of direct assessments are that they may not be sufficiently sensitive to show change in response to an intervention, may be time-consuming to administer, and often need to be completed by a specialist.

On the other hand, indirect assessments such as the Teacher Rating of Oral Language and Literacy (TROLL; Dickinson, McCabe, & Sprague, Citation2003) can be completed quickly by those most familiar with the children. This is important because child outcomes are commonly missing from empirical studies so investigating practical ways to collect data rapidly is essential. Although subjective, both educator and parent completed reports can be valid ways of measuring children's language and literacy skills (e.g. Cabell, Justice, Zucker, & Kilday, Citation2009; Krieg & Curtis, Citation2017). Sheridan, Knoche, Kupzyk, Edwards, and Marvin (Citation2011) used educators' ratings of preschoolers following a parent-training intervention and found that educators reported increases in preschoolers' language and literacy skills after the intervention and these ratings corresponded with standardised measures. Further exploration of educator and parent ratings of child language and pre-literacy abilities in the context of real-world PD interventions is needed.

A final benefit of indirect assessment relates to the first black box of educator learning. Evidence suggests that educators are more likely to continue using language and literacy-promoting behaviours if they see them as beneficial to the children with whom they work (Dunst, Citation2015). Therefore, an increase in educators' reports of preschoolers' skills after PD may suggest that the PD will have longer-lasting effects.

Aims and research questions

This paper aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a real-world 10-week language and literacy-based PD intervention. The intervention, known as the Training in Interaction, Communication and Literacy (TICL) program, was delivered to two ECEC centres. The following research questions were asked:

(1) Do educators who participate in TICL use language and literacy-promoting behaviours more frequently following completion of TICL?

(2) Does TICL result in improved preschoolers' language and literacy skills as measured by preschoolers' educators and parents/carers?

Method

Research design

This paper describes two pragmatic studies of TICL (Figure S1). The first study examined educator outcomes with a pragmatic observational approach. The second study evaluated preschooler outcomes with a pragmatic non-randomised controlled trial. Ethical approval was obtained from The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (Project number: 2015/676). The trial was prospectively registered in the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (Universal Trial Number: U1111-1173-9236).

Recruitment and demographics of the ECEC centres

TICL was delivered by a non-profit organisation using government funding to support children in a specific local government area. The organisation distributed flyers to all ECEC settings in that area, and four centres were recruited. Two ECEC centres were chosen to participate in TICL due to their availability in time periods mandated by the funder. The other two centres acted as control ECEC centres.

Two of the ECEC centres, one control and one TICL, were located in postcodes assigned an Index of Relative Socioeconomic Advantage and DisadvantageFootnote3 (IRSAD) decile of 1. Two centres were located in postcodes with IRSAD deciles of 2. Most residents in the local government area live in households where a language other than English is spoken, with Arabic (17.2%) and Vietnamese (7.2%) being most frequently used (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016a).

The ECEC centres' environments

The environments of the centres were measured using the General Classroom Environment subscale from the Early Language and Literacy Classroom Observation Pre- Kindergarten Tool (ELLCO Pre-K; Smith, Brady, & Anastasopoulos, Citation2008) to ensure no substantial differences across centres that may have explained outcome changes. Each centre was scored pre- and post-TICL by the first author after approximately 2 hours of observation, including watching a range of activities. A Mann-Whitney U test was then run to determine if there were differences in the environments between the intervention and control ECEC centres. The environments were similar at pre-TICL (intervention Mdn = 3.29; control Mdn = 3.29), U = 2, z = 0, p = 1.000, and post-TICL (intervention Mdn = 3.50; control Mdn = 3.58), U = 2, z = 0, p = 1.000. A Wilcoxon's Sign Rank test was used to assess if there were any changes in the environment for each group pre to post. No significant changes were seen in the intervention centres from pre-TICL (Mdn = 3.29) to post (Mdn = 3.57), z = 0, p = 1.000 or in the control centres from post-TICL (Mdn = 3.29) to post (Mdn = 3.50), z = 0, p = 1.000.

Study one: addressing research question one

Participants

Educators working within the two TICL ECEC centres were invited to participate. Fourteen educators consented, however one educator resigned before completion. The teaching experience of the remaining 13 educators ranged from 6 months to 20 years (mean 4.8 years; SD = 6.5 years). Most educators reported having a 2-year Diploma in Early Childhood Education (n = 7), five educators had a 1-year Certificate III in Early Childhood Education, and one had a 3-year university degree.

Procedures

The 13 educators self-rated how frequently they used language and literacy-promoting behaviours pre- and post-TICL. Pre-ratings were conducted four weeks before TICL and post-ratings were collected one – four weeks after. TICL was delivered to one centre, and then seven months later it was delivered to the second centre. This was due to the availability of the two facilitating SLPs and the government funding time frame.

Outcome measure

All 13 educators self-rated the frequency of their language and literacy-promoting behaviours using the Interaction, Communication and Literacy Skills Audit (The ICL Skills Audit; El-Choueifati, Purcell, McCabe, Heard, & Munro, Citation2014). The ICL Skills Audit, as well as being a self-reflection tool for the intervention, is a valid, reliable, and evidence-based tool for educators teaching children aged 2–7 years. The reported intra-rater reliability for the ICL Skills Audit using percentage close agreement is 91−94% and inter-rater agreement is 68−80% close agreement (El-Choueifati et al., Citation2014).

Intervention

TICL was developed by SLPs from the non-profit organisation and the university (El-Choueifati, Munro, McCabe, Purcell, & Galea, Citation2010). It was designed using the principles of Dollaghan's E3BP triangle: (1) external evidence, (2) clinical judgement, and (3) client preferences and values (Dollaghan, Citation2007). External evidence was acquired through a systematic review (El-Choueifati, Purcell, McCabe, & Munro, Citation2012). The clinical judgement was the professional experiences of SLPs from the non-profit organisation and the university. The educators' preferences and values when teaching language and early literacy were gathered in a series of focus groups with Australian educators.

TICL included workshops and coaching sessions. Workshops ran at each TICL ECEC centre for approximately 60 minutes, once per week for 10 weeks and were facilitated by the same two SLPs. The workshops included information-giving, video examples, role play and group discussions (Table S1). Following each workshop, individual coaching sessions were also provided to each educator. Coaching sessions were guided by the educator's chosen goals based on the workshop content and lasted 15–45 minutes.

Table I. Characteristics of the preschoolers in the intervention and control groups pre-intervention.

TICL was designed to incorporate self-assessment of educators. The ICL Skills Audit is considered an inseparable part of TICL as it encourages self-reflection and highlights what content needs to be incorporated into workshops and coaching sessions.

Intervention fidelity

Several procedures encourage fidelity. Workshop and coaching sessions were delivered by SLPs familiar with TICL. Workshop and coaching logs and checklists were used by the facilitating SLPs as a fidelity self-report and were always 100%. Additionally, the first author observed three workshops and three coaching sessions (chosen at random) at both TICL centres to confirm that workshops and coaching plans were followed.

Study two: addressing research question two

Participants

The parents/carers of 86 preschoolers across the four ECEC centres provided informed written consent. Four preschoolers were excluded as follows: one preschooler had no date of birth provided, one preschooler was a recent refugee with no English exposure, and two preschoolers were unable to attend to the assessment and were referred on. In total, 82 preschoolers were available for assessment before TICL; 42 preschoolers in the TICL condition and 40 preschoolers in the control condition.

Parents completed a questionnaire about their children. Information from this questionnaire was then used to determine each preschooler's age, sex, attendance, and culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) background. A preschooler was determined to have a CALD background if their parent/carer reported (1) the preschooler was born in a country other than Australia and/or (2) the preschooler spoke a language other than English and/or (3) the preschooler lived in a household where a language other than English was spoken. Demographic characteristics were similar for the cohorts ().

Procedure

The language and literacy skills of the preschoolers were rated by their educators and parents/carers pre- and post-TICL. Pre-tests were collected four weeks before TICL, and post-tests were collected six months post-TICL. This timing was connected to which ECEC centre the preschooler was attending. As mentioned in study one, the two TICL centres received TICL seven months apart. For this study, each TICL ECEC centre was paired with a control ECEC centre and data collection for preschoolers from control ECEC centres matched their paired TICL ECEC centre's timing. Educators and parents/carers did not have access to pre-test ratings when completing their post-test ratings. Educators knew whether their ECEC centre was in the TICL/control condition. Parents/carers were told that educators from their child's ECEC centre might attend TICL or might not (control).

Outcome measure

The preschoolers' language and early literacy skills were rated by their educators using the Teacher Rating of Oral Language and Literacy (TROLL; Dickinson et al., Citation2003). The TROLL was chosen because the norming sample consisted of low-income, high-risk children and is designed to be used without training making it ideal for a pragmatic study. The TROLL has three subscales (1) oral language, (2) reading and (3) writing and is reported to be a valid and reliable measure (Dickinson et al., Citation2003).

The TROLL has previously been used to detect changes in children's skills following language and early literacy PD for ECEC educators (Dickinson et al., Citation2003). Children's TROLL scores were significantly higher if their teachers participated in PD compared with children whose teachers did not participate in PD. These results suggest that the TROLL is sensitive enough to measure change following PD.

To determine if any changes in preschoolers' language and literacy skills were generalised to the home environment, parents were also asked to complete the TROLL (Table S2). The authors of the TROLL report that parents can also use the TROLL and that it may be useful for bilingual children to see how their skills are developing at home where a language other than English may be used.

Table II. Self-reported scores pre-intervention and post-intervention for educators on the ICL Skills Audit.

Attrition and missing data

Prior to the intervention, 82 preschoolers were available for assessment and 58 of those preschoolers were available post-intervention, representing 29% attrition. Attrition of preschoolers was greater for the first pair of TICL and Control centres. During this time, 19 preschoolers (9 TICL, 10 Control) left their centres between pre- and post-collection of the outcome measures. Of these, 18 preschoolers (9 TICL, 9 Control) moved to formal schooling and 1 preschooler moved to a different centre and was lost to follow-up. Attrition was lower for the second TICL and Control centres, 5 preschoolers (4 TICL, 1 Control) were lost to follow-up. In total, 22 preschoolers (10 TICL, 12 Control) were available at pre- and post-intervention from the first TICL and Control ECEC centres and 36 preschoolers (19 TICL, 17 Control) were available at pre- and post-from the second TICL and Control centres.

Chi-square and t-tests revealed no significant differences in attrition due to intervention, sex, or CALD status (p > 0.05). There was a significant difference in attrition due to age, t (80) = 3.807, p = 0.001 which was expected as older preschoolers left to commence formal schooling. After attrition, the mean age of the TICL ECEC centres reduced from 48.5 months (SD 5.5) to 46.7 months (SD 3.6) and the mean age of the control ECEC centres reduced from 48.4 months (SD 7.5) to 46.5 months (SD 6.2) p = 0.331. No significant differences between the preschoolers in the intervention and control groups were found in terms of age after attrition p = 0.857.

Intervention

As described above, TICL was delivered to the educators of the two TICL centres. All preschoolers also received instruction per the Early Years Learning Framework (Australian Government Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations, Citation2009).

Data analysis

SPSS statistical software (version 24, IBM) was used for all analyses. The educator measures were analysed using Wilcoxon's Signed Rank Test to determine change in frequency of behaviours (pre-intervention versus post-intervention scores) on the ICL Skills Audit. A non-parametric statistical test was used due to the small sample size and because visual inspection of the ICL Skills Audit data revealed distribution was mainly across 3–4 points of the scales (De Winter & Dodou, Citation2010). Effect sizes for the educator outcomes were computed by dividing the standardised test statistics (z) by the square root of the number of observations to obtain r values (Fritz, Morris, & Richler, Citation2012) and interpreted as small (0.10–0.29), medium (0.30–0.49) and large (>0.50) (Cohen, Citation2013).

For the preschooler measures, gain scores were used to measure change. Independent samples t-tests were used to determine changes in performance on the TROLL scores following the TICL intervention. Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s d and interpreted as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5) and large (d = 0.8) (Cohen, Citation2013).

Result

Study one: educators' language and literacy-promoting behaviours

Educators self-reported more frequent use of language and literacy-promoting behaviours following TICL (). There was a statistically significant median increase in overall score on the ICL of 44 points, z = −3.18, p < 0.001, r = 0.62. Educators' self-reported scores significantly increased in four skill areas (Skill Areas 1, 2, 3 & 6) with large effect sizes.

Study two: preschoolers' language and early literacy skills

Pre-intervention

For educator ratings, there were no significant differences between groups for TROLL total score t(79) = −0.865, p = 0.390, TROLL oral language score t(79) = −0.803, p = 0.425, TROLL reading score t(79) = −1.036, p = 0.303 or TROLL writing score t(56)= −0.807, p = 0.423. Similarly, for parent ratings there were no significant differences between groups for TROLL total score t(74) = 0.501, p = 0.618, TROLL oral language score t(74) = −0.066, p = 0.947, TROLL reading score t(74) = 0.585, p = 0.560, or TROLL writing score t(74) = 0.722, p = 0.473.

Post-intervention

The preschoolers from the Control centres, from pre- to post-intervention, did not show a statistically significant change in their total educator-reported TROLL scores (M = 6.10, SD = 6.6) or on any of the subtest scores (oral language, reading and writing) (all p's> 0.05). By comparison, the preschoolers from the TICL ECEC centres demonstrated a statistically significant change in their total TROLL score (M = 13.6, SD = 10) and in their reading subtest score (M = 6.5, SD = 5.1). These results are shown in .

Table III. Descriptive statistics and between-group differences in gain scores for educator-rated TROLL Scores.

Parents/carers' ratings of preschoolers from Control and TICL ECEC centres had no significant change from pre- to post-intervention in their total TROLL scores or on any of the TROLL subtest scores (all p's> 0.05). These results are shown in Table S2.

Discussion

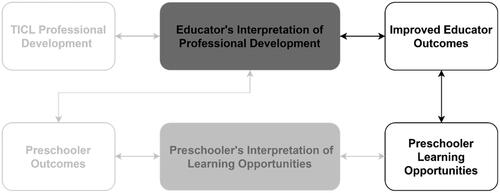

This paper aimed to find out if TICL, a real-world PD intervention, was effective in changing educator behaviours and, subsequently, preschoolers' language and early literacy skills. We viewed PD as a complex intervention and used a pragmatic approach to answer the questions: (1) Do educators who participate in TICL use language and literacy-promoting behaviours more frequently after TICL? (2) Does TICL result in improved preschoolers' language and early literacy skills as measured by their educators and parents/carers? Guided by a modified version of Timperley et al.'s (Citation2007) twin black boxes model () we identified that educators were pivotal as key stakeholders in answering both questions. After the intervention, educators rated themselves as using language and literacy-promoting behaviours more often and also scored children's oral language and early literacy skills higher. In contrast, parents/carers did not report the same increase in early literacy skills. The fact that educators reported an increase in their own skills and the early reading skills of preschoolers after TICL suggests that TICL may be effective in improving educator and preschooler outcomes, but further research is needed to confirm if preschoolers' skills improved using more objective measures.

The ensuing discussion reflects on how the findings add empirical information supporting viewing PD as a complex intervention. We address how these results inform our modified version of Timperley et al.'s (Citation2007) black boxes model and consider what this means for future evaluation of PD. The findings are unique for three reasons. First, we studied a real-world PD intervention that includes educator outcomes as part of routine practice. Second, it included both educator and parent ratings of preschooler outcomes before and after language and literacy-focussed PD in ECEC settings. Finally, it is considered within a new paradigm, PD as a complex intervention.

Educator outcomes

Educators reported significant increases in their use of language- and literacy- promoting behaviours in four of the six Skill Areas (): Skill Areas 1 (Developing positive and responsive adult-child interactions), 2 (Explicit literacy instruction), 3 (Develop storytelling skills) and 6 (Developing responsive family involvement) but not in Skill Areas 4 (Encouraging all children in a group to participate) and 5 (Being able to foster peer-to-peer interactions). Skill Areas 4 and 5 were only targeted for one PD workshop session whereas the other Skill Areas were targeted during two or three workshops (Table S1), indicating that duration and intensity may have been a factor in educators' interpretation of the PD. Both duration and intensity have repeatedly been shown to be important in improving educator outcomes following PD (e.g. Markussen-Brown et al., Citation2017).

Figure 2. Educator outcomes within the modified twin black boxes model Timperley et al. (Citation2007).

The absence of significant changes in self-reported skills across Skill Areas 4 and 5 is also interesting given educators were subject to biases, including reporting bias, and the Hawthorne effect (Levitt & List, Citation2011) both pre- and post-intervention. The Hawthorne effect refers to participants modifying their behaviour due to observation. Educators were aware their self-reports were being collected and thus were likely to inflate their skills rating on the ICL. Before TICL, educators rated themselves as using target behaviours frequently across all six areas () but significant self-reported changes were only seen in the four skill areas targeted during more than one workshop. This is consistent with previous research by Norman, Pearce, and Eastley (Citation2021) who used the same tool. They found that educators rated themselves highly prior to a PD intervention but still reported significant changes post-PD. Overall, the results from Study One suggest that while self-rating behaviours are inherently biased, change in educators' scores may provide a nuanced measure. Future research should compare educators' rating changes with more objective measures.

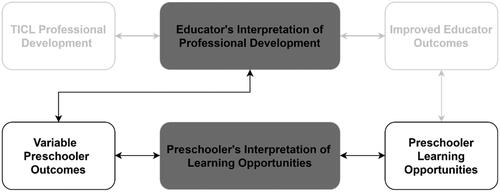

Preschooler outcomes

Regarding early literacy skills, educators reported an increase in preschoolers' early reading skills as measured by the TROLL (looking at and listening to books, alphabetic knowledge, letter-sound knowledge, word recognition) but not their early writing skills (writing name, letters, words etc.) and parents/carers did not report an increase in any early literacy skills. These early writing results make sense as the intervention did not emphasise writing explicitly. However, the difference in the educators’ early reading ratings compared with the parents’/carers’ ratings warrants further exploration to determine which group of raters were accurate. Currently, it is not possible to determine if (1) preschoolers’ early reading skills did not improve but educators perceived that they did, or (2) preschoolers’ early reading skills did improve but parents did not perceive the change.

There were no significant gains in oral language skills as rated by educators or parents/carers. This was surprising given oral language skills make up a substantial amount of the TICL PD intervention (Table S1). Moreover, educators reported an increase in the frequency of their use of language-promoting behaviours. Therefore, these results suggest either a failure to translate educator outcomes into preschooler learning opportunities or that preschoolers’ interpretation of their learning opportunities did not result in a significant change in skills.

It was interesting that educators rated preschoolers’ early reading skills as higher after TICL but not their oral language skills. It may be that preschooler oral language learning opportunities did not increase post-TICL substantially beyond what would be expected from participating in the EYLF curriculum. Curriculum can be a powerful intervention (Tayler, Citation2017) and TICL’s effects on preschoolers’ learning opportunities may not have been sufficient to see change in preschoolers’ language outcomes above the standard EYLF curriculum.

Another possibility is that the preschooler oral language outcomes provide more insight into educators’ interpretation of the PD than the actual preschooler outcomes. Kirkby, Keary, and Walsh (Citation2018) found that Australian educators valued the role of intentional teaching of oral language skills more highly following a collaboration with SLPs. This represented a substantial shift from the traditional view of some educators that oral language development best occurs solely through child-led play. In the same study, educators reported paying more attention to discrete oral language skills such as prepositions following the intervention. Similarly, TICL may have shifted how educators viewed their direct role in developing oral language skills causing them to scrutinise oral language skills and possibly rate them differently to how they rated them before TICL. Australian ECEC educators receive very little content about language structure in their formal training to become an educator (Weadman et al., Citation2021). Thus, increased knowledge of oral language following TICL may also have influenced their ratings.

A final consideration is that dosage may have contributed to the differences in educators' ratings of preschoolers' language and early literacy skills. Educators may have focussed on developing early literacy skills during their coaching sessions and/or used more literacy-promoting behaviours six months after TICL before post-rating scores were collected. Covering a broad range of language and early language skills over the 10-week intervention period may have resulted in an attenuated dosage of oral language. Pianta et al. (Citation2017) similarly focussed on a wide range of oral language skills in their PD and also found no significant improvement in preschoolers’ language skills. However, in contrast, Wasik and Hindman (Citation2020) focussed exclusively on vocabulary in their PD with subsequent improvement in preschoolers’ vocabulary skills. It was beyond the scope of this pragmatic study to investigate dosage but there is evidence that dosage affects child outcomes in the context of PD (e.g. Markussen-Brown et al., Citation2017) and would be worthy of further consideration.

Limitations

This research occurred within a real-world context and thus had real-world constraints. The studies were restricted to one local area and had relatively few ECEC centres, educators, and preschoolers. It was also not possible to have an independent rater evaluate the ECEC environments. Additionally, there was high attrition of preschoolers due to one iteration of TICL being delivered at the end of the school year and preschoolers subsequently leaving to attend formal schooling. Both the small sample size and the time frame were unavoidable due to the funding constraints however future research should include an independent rater of ECEC environments and/or interrater reliability checks

The decision not to have the control group of educators complete the ICL Skills Audit was deliberate because the ICL Skills Audit was viewed as an intervention on its own and an inextricable part of TICL. However, having no control group means we also cannot determine whether the educators would have rated themselves more highly due to familiarity with the ICL skills audit or the passage of time. Elek, Gray, West, and Goldfeld (Citation2021) used the ICL Skills Audit as an outcome measure following a literacy-based PD and found both observed and self-reported ratings improved, but not significantly from a control group of educators. The small sample size of educators here also means we cannot delineate whether the educators' varied levels of formal education prior to TICL influenced outcomes. Future research needs to clarify the role of the ICL Skills Audit in the TICL PD.

Our primary child measure, the TROLL, also had several limitations. Although the TROLL content broadly aligned with the TICL content, it may not have measured the specific oral language targets of TICL precisely enough. In their meta-analysis and systematic review, Brunsek et al. (Citation2020) found that author-created assessments that explicitly matched child outcomes to PD content demonstrated more positive associations than more general assessments. The TROLL was selected because educators and parents could use it without training. However, although it has been used to evaluate a PD program previously, it is unclear whether it was sensitive to change for bilingual and CALD children. Its use by parents was also recommended for bilingual children (Dickinson et al., Citation2003); however, we however we could not find any research validating its use in this way. Additionally, parents were not given specific instructions on how to use the tool and in what language to rate their child's skills if their child spoke a language other than English. Thus, some parents may have reported on their child's skills in English even if this underestimated their abilities in another language. Choosing a different parent rating tool with more published data, particularly for bilingual children, warrants future research.

Clinical implications and future directions

The pragmatic studies outlined in this paper suggest both clinical implications and recommendations for future evaluations of PD interventions. Most importantly, the results support viewing PD as a complex intervention. Further, the fact that educator outcomes unanimously improved but preschooler outcomes were variable fits within our modified version of Timperley's twin black box model (2007), suggesting that an interruption may have occurred between educator and preschooler outcomes.

SLPs looking to facilitate PD within an ECEC setting need to consider evaluating educator and child outcomes as part of routine practice to determine if the PD is useful. This is not a novel recommendation (Schachter, Citation2015); however, the black boxes model presented in this paper provides a more complete picture of where PD interventions may go from being effective to ineffective. For example, the findings here suggest that TICL was effective in changing educator outcomes and possibly some preschooler outcomes but that future iterations of the intervention may need to look at strengthening the oral language components of the program. It is likely that the black boxes not only represent the unknown processes that occur as part of educator and preschooler learning after PD but also act as a filter. This may mean teaching the content differently, increasing the duration or intensity of some of the content, or focussing on teaching educators different ways of improving oral language skills in preschoolers. Future research should manipulate various features of TICL to determine if this improves preschooler outcomes.

There is scant literature about educator and parent ratings of preschoolers' skills before and after language and literacy-based PD interventions. As key stakeholders, their views are essential. Educators' ratings of preschooler skills are particularly relevant as they provide information about both black boxes in our modified model (). Tracking small changes in preschoolers’ skills relating to PD content is likely to strengthen educators' behaviours (Schachter, Gerde, & Hatton-Bowers, Citation2019). Thus, rating scales may be a clinically useful measure given they provide helpful information and are quick to administer. Future research needs to investigate how well educators' ratings align with more objective measures of preschoolers' performance. Ideally, a combination of objective and subjective data should be used to determine the effectiveness of an intervention.

Figure 3. Preschooler outcomes within the modified twin black boxes model Timperley et al. (Citation2007).

Conclusion

Reframing PD as a complex intervention provides insight into how PD should be evaluated. The evidence presented in this paper that educators reported an increase in preschoolers' early reading skills is promising, especially when combined with educators' improved self-assessment of their skills. Taken together, these results may indicate that the PD intervention achieved two important objectives theorised to be necessary for successful PD: (1) educators reported improvements in their own practices, and (2) educators reported improvements in preschoolers' early reading skills (Dunst, Citation2015). Future research should ascertain whether these reported improvements match objective measures such as direct testing of preschooler outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (352.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the educators, ECEC centres, parents/carers, preschoolers, and speech-language pathologists who took part in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Intentional teaching is when educators make purposeful and thoughtful choices and participate in actions designed to improve a particular child skill (Department of Education, Citation2009)

2 Standardised outcome measures included the the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition (PPVT-4: Dunn & Dunn, Citation2007) and the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test – Fourth Edition (EOWPVT-4: Martin & Brownell, Citation2011)

3 IRSAD deciles, which range from 1 to 10, are assigned to Australian postcodes based on economic and social conditions, with a decile of 1 given to the most disadvantaged postcodes (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016b)

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016a). 2016 Census QuickStats: Canterbury Bankstown. Retrieved from https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/LGA11570?opendocument

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016b). Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA) 2016 technical paper. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/2033.0.55.0012016?OpenDocument

- Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. (2009). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/national-quality-framework-early-childhood-education-and-care/resources/belonging-being-becoming-early-years-learning-framework-australia

- Berwick, D.M. (2005). Broadening the view of evidence-based medicine. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 14, 315–316. doi:10.1136/qshc.2005.015669

- Brebner, C., Attrill, S., Marsh, C., & Coles, L. (2017). Facilitating children's speech, language and communication development: An exploration of an embedded, service-based professional development program. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 33, 223–240. doi:10.1177/0265659017702205

- Brunsek, A., Perlman, M., McMullen, E., Falenchuk, O., Fletcher, B., Nocita, G., … Shah, P.S. (2020). A meta-analysis and systematic review of the associations between professional development of early childhood educators and children's outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 217–248. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.03.003

- Burchinal, M., Howes, C., Pianta, R.C., Bryant, D., Early, D., Clifford, R., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Predicting child outcomes at the end of kindergarten from the quality of pre-kindergarten teacher-child interactions and instruction. Applied Developmental Science, 12, 140–153. doi:10.1080/10888690802199418

- Buysse, V., Castro, D.C., & Peisner-Feinberg, E. (2010). Effects of a professional development program on classroom practices and outcomes for Latino dual language learners. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 194–206. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.10.001

- Cabell, S.Q., Justice, L.M., Zucker, T., & Kilday, C.R. (2009). Validity of teacher report for assessing the emergent literacy skills of at-risk preschoolers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40, 161–173. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2009/07-0099)

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Burlington: Elsevier Science.

- Commonwealth Department of Education and Training. (2016). Australian early development census national report 2015: A snapshot of early childhood development in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.aedc.gov.au/resources/detail/2015-aedc-national-report

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2019). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: New guidance. Medical Research Council, UK. https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/

- De Winter, J.C., & Dodou, D. (2010). Five-point Likert items: t Test versus Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 15, 1–12. doi:10.7275/bj1p-ts64

- Dickinson, D.K., McCabe, A., & Sprague, K. (2003). Teacher rating of oral language and literacy (TROLL): Individualizing early literacy instruction with a standards-based rating tool. The Reading Teacher, 56, 554–564. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20205246

- Dollaghan, C. A. (2007). The handbook for evidence-based practice in communication disorders. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

- Dunn, L., & Dunn, D. (2007). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Fourth Edition (PPVT-4)). Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessments.

- Dunst, C.J. (2015). Improving the design and implementation of in-service professional development in early childhood intervention. Infants & Young Children, 28, 210–219. doi:10.1097/iyc.0000000000000042

- El-Choueifati, N., Munro, N., McCabe, P., Purcell, A., & Galea, R. (2010). TICL – The triad of success leading to positive outcomes in language and pre-literacy for children. Paper presented at the World Congress of the International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics, Athens, Greece.

- El-Choueifati, N., Purcell, A., McCabe, P., Heard, R., & Munro, N. (2014). An initial reliability and validity study of the interaction, communication, and literacy skills audit. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 260–272.

- El-Choueifati, N., Purcell, A., McCabe, P., & Munro, N. (2012). Evidence-based practice in speech language pathologist training of early childhood professionals. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 6, 150–165. doi:10.1080/17489539.2012.745293/

- Elek, C., Gray, S., West, S., & Goldfeld, S. (2022). Effects of a professional development program on emergent literacy-promoting practices and environments in early childhood education and care. Early Years, 42(1), 1–16. doi:10.1080/09575146.2021.1898342

- Escamilla, I.M., & Meier, D. (2018). The promise of teacher inquiry and reflection: Early childhood teachers as change agents. Studying Teacher Education, 14, 3–21. doi:10.1080/17425964.2017.1408463

- Ford, I., & Norrie, J. (2016). Pragmatic trials. New England Journal of Medicine, 375, 454–463. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1510059

- Fritz, C.O., Morris, P.E., & Richler, J.J. (2012). Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141, 2–18. doi:10.1037/a0024338

- Glasgow, R.E., & Riley, W.T. (2013). Pragmatic measures. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45, 237–243. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.010

- Kirkby, J., Keary, A., & Walsh, L. (2018). The impact of Australian policy shifts on early childhood teachers' understandings of intentional teaching. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26, 674–687. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2018.1522920

- Krieg, S., & Curtis, D. (2017). Involving parents in early childhood research as reliable assessors. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25, 717–731. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1350293x.2017.1356601

- Levitt, S.D., & List, J.A. (2011). Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3, 224–238. doi:10.1257/app.3.1.224

- Markussen-Brown, J., Juhl, C.B., Piasta, S.B., Bleses, D., Højen, A., & Justice, L.M. (2017). The effects of language- and literacy-focused professional development on early educators and children: A best-evidence meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38, 97–115. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.07.002

- Martin, N.A., & Brownell, R. (2011). Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (Fourth Edition (EOWPVT-4)). Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publications.

- Norman, T., Pearce, W.M., & Eastley, F. (2021). Perceptions of a culturally responsive school-based oral language and early literacy programme. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 50, 158. doi:10.1017/jie.2019.25

- Pianta, R., Hamre, B., Downer, J., Burchinal, M., Williford, A., Locasale-Crouch, J., … Scott-Little, C. (2017). Early childhood professional development: Coaching and coursework effects on indicators of children's school readiness. Early Education and Development, 28, 956–975. doi:10.1080/10409289.2017.1319783

- Renshaw, L., & Goodhue, R. (2020). National early language and literacy strategy: Discussion paper. ARACY. Retrieved from https://earlylanguageandliteracy.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/National-Early-Language-and-Literacy-Discussion-Paper-2020.pdf

- Schachter, R.E. (2015). An analytic study of the professional development research in early childhood education. Early Education and Development, 26, 1057–1085. doi:10.1080/10409289.2015.1009335

- Schachter, R.E., Gerde, H.K., & Hatton-Bowers, H. (2019). Guidelines for selecting professional development for early childhood teachers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47, 395–408. doi:10.1007/s10643-019-00942-8

- Schliep, M.E., Alonzo, C.N., & Morris, M.A. (2017). Beyond RCTs: Innovations in research design and methods to advance implementation science. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 11, 82–98. doi:10.1080/17489539.2017.1394807

- Sheridan, S.M., Knoche, L.L., Kupzyk, K.A., Edwards, C.P., & Marvin, C.A. (2011). A randomized trial examining the effects of parent engagement on early language and literacy: The getting ready intervention. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 361–383. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2011.03.001

- Smith, J., Levickis, P., Neilson, R., Mensah, F., Goldfeld, S., & Bryson, H. (2021). Prevalence of language and pre‐literacy difficulties in an Australian cohort of 5‐year‐old children experiencing adversity. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 56, 389–401. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12611

- Smith, M.W., Brady, J.P., & Anastasopoulos, L. (2008). Early language & literacy classroom observation pre-K Tool (ELLCO Pre-K). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

- Snow, P.C. (2016). Elizabeth Usher Memorial Lecture: Language is literacy is language - Positioning speech-language pathology in education policy, practice, paradigms and polemics. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18, 216–228. doi:10.3109/17549507.2015.1112837

- Tayler, C. (2017). The E4Kids Study: Assessing the effectiveness of Australian early childhood education and care programs. Overview of findings at 2016. Melbourne Graduate School of Education. Retrieved from https://education.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2929452/E4Kids-Report-3.0_WEB.pdf

- Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2007). Teacher professional learning and development: Best evidence synthesis iteration (BES). Ministry of Education Wellington. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/48727127.pdf

- Wasik, B.A., & Hindman, A.H. (2020). Increasing preschoolers' vocabulary development through a streamlined teacher professional development intervention. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 50, 101–113. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.11.001

- Weadman, T., Serry, T., & Snow, P, La Trobe University, Bendigo Campus, Victoria. (2021). Australian early childhood teachers' training in language and literacy: A nation-wide review of pre-service course content. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 46, 29–56. doi:10.14221/ajte.2021v46n2.3