Abstract

Purpose

The Foundations of Early Literacy Assessment – Northern Territory (FELA-NT) was funded, developed, and implemented as part of a strategy designed to address the English literacy learning needs of the Northern Territory’s Aboriginal student population. In this paper we question whether the FELA-NT English literacy learning benchmarks are representative of remote and very remote Aboriginal students since many speak English as an Additional Language (EAL) or Dialect (EAD).

Result

Using a new data set of scores from 72 Aboriginal students from remote, very remote, and outer-regional communities on the FELA-NT, we demonstrate that it is the student’s experience with Standard Australian English, not their remoteness, that impacts their early literacy development.

Conclusion

We use this example to illustrate how current practices and policies homogenise the Australian Aboriginal student population, silencing linguistic diversity in the process. We call for clinical practitioners and educators to shift their practices to assessments and tools that recognise children and youths’ diverse linguistic skills and pathways. We talk about what empowerment, participation, and inclusion might really mean in current Australian educational and clinical contexts. We argue here that we need to fundamentally rethink how we work with children with diverse language and literacy knowledge, skills, and backgrounds if we are to reduce inequalities (SDG 10), honour quality education (SDG 4), and support sustainable communities (SDG 11).

Across Australia, Aboriginal languages are considered vulnerable; many are in an active process of revitalisation. In the Northern Territory some Aboriginal languages are still spoken by all generations (e.g. Pitjantjatjara, Murrinhpatha) and this is to be celebrated and nurtured. Aboriginal Australian languages have a unique way of encapsulating the linguistic and cultural heritage of the world’s oldest living culture. However, neither Aboriginal language nor Aboriginal culture are broadly valued by the Australian education system (e.g. Marika, Citation1999; Wigglesworth et al., Citation2018). We see this in the lack of interpretive services available for Aboriginal people in health spaces (Ralph et al., Citation2017), and the dismantling of bilingual educational language programs (e.g. Devlin, Disbray & Devlin, Citation2017). Current Australian standardised testing practices and the subsequent decision making around test scores typically positions remote and multilingual Aboriginal students through a deficit lens rather than “building positive images of Indigenous children as learners” (Dockett et al., Citation2010, p. 1).

In this paper we question whether the norming data set of the Foundations of Early Literacy Assessment – Northern Territory (FELA-NT), a test funded and designed for Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory, are representative of remote and very remote Aboriginal students since many speak English as an Additional Language (EAL) or Dialect (EAD). We use this example to question Australia’s commitment to reducing inequity, as well as social and political inclusion, as stated in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG, United Nations, Citation2015) target 10.2, which strives to

“empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status”

and target 10.3:

Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard”.

We also use this example to consider how Australian health and education systems might honour SDG 11, target 11.4 to “protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage” (United Nations, Citation2015) if we want to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (SDG 4, United Nations, Citation2015).

Background

Australia’s first National Policy on Languages (Lo Bianco, Citation1987) recognised that for many of Australia’s remote Aboriginal peoples, English is effectively a foreign language, infrequently encountered in their community. The National Policy on Languages established diverse language learning pathways for multilingual Aboriginal children to learn in and through their first language, and to learn English as an additional language at school (Lo Bianco, Citation1987).

Following a meeting of all Australian Education Ministers in December 2019, the Mparntwe Educational Declaration agreed that the purpose of Australian schooling is to promote excellence and equity (Education Council, Citation2019). The Declaration committed all Australian governments to empowering Aboriginal people, and to “close the gap” for young Aboriginal Australians. Framing the goal for Aboriginal Australians in this way reinforced a focus on testing and a proliferation of new data-driven accountabilities. These have changed what counts, and what is counted as excellent and equitable outcomes. In considering the close the gap narrative (Education Council, Citation2019), we explore the appropriateness of interpreting the test performances of young Aboriginal English language learners against assessments designed for and standardised for monolingual English-speaking students. We consider how these practices work towards a national commitment to reduce inequality (SDG 10 United Nations, Citation2015) within Australia and SDG 4, target 4.1 to

ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes.

For more than a decade, Australian education policy makers have held schools accountable for ensuring all students achieve national minimum year level literacy expectations. This one-size-fits-all normative framing of Australia’s national curriculum and assessment regime leads policy makers to respond to the diversity of students’ language and literacy outcomes by focussing on groups who are judged to be underperforming (Cumming et al., Citation2020). This is particularly the case for Aboriginal students whose results are disaggregated in national reporting data sets (Ford, Citation2013).

The Northern Territory Department of Education ([NT DoE], Citation2020) reported that 43% of the jurisdiction’s diverse student population identify as Aboriginal, and 49% of all students learn English as an additional language or dialect. English is not widely spoken in very remote communities and thus is learned as a foreign language (Freeman & Staley, Citation2018; Wilson, Citation2014). The varied linguistic environments of multilingual children, and the differing amount and quality of English input that the second language learners receive, influences their English language development (Paradis & Jia, Citation2017). Wilson (Citation2014) in reviewing Aboriginal education in the Northern Territory also reported a close correlation between remote Aboriginal students’ language background and their national English reading comprehension test scores. Consequently, it is questionable whether the current system-wide English literacy benchmarks are representative of remote and very remote Aboriginal students early English literacy learning milestones.

The FELA-NT is a system-wide assessment tool for monitoring Northern Territory students’ development of the early English literacy skills theorised to underlie and support word recognition skills (i.e. decoding). Implemented in 2018, the FELA-NT assesses phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, phonics knowledge, and word knowledge and was designed as a move to addresses educational disadvantage and close the gap. FELA-NT presents mastery level expectations for Kindergarten (∼ 5 years) to Year 3 (8–9 years). The test manual states that if the relevant foundational skills are not mastered at critical points, then FELA results provide “red flags” (Neilson, Citation2016). This information is intended to help teachers provide targeted and timely support to students learning these foundational literacy skills.

Mastery level expectations for Year 3 were based on the observed average performance of Darwin-based (referred to as Urban in this data set) students (n = 63) who participated in a FELA-NT trial (Neilson, Citation2016). Although FELA-NT was also trialled in four remote Aboriginal schools in the Northern Territory, those results were not included in the determination of FELA-NT’s mastery levels (benchmarks). Neilson (Citation2016) noted that “it seemed highly likely that we were dealing with different sub-populations, and it was judged that the urban data was more likely to support fair generalisations to other similar Australian populations than the data from the remote communities” (p. 54). The FELA-NT was funded, developed, and implemented as part of a strategy designed to address the English literacy learning needs of the Northern Territory’s Aboriginal students. However, it had norms developed only from urban school students to ensure the mastery year level benchmarks would be relevant and representative of mainstream national English literacy achievement expectations.

In this paper, we question whether these early literacy benchmarks are representative of remote and very remote Aboriginal students’ early English literacy learning milestones given remote and very remote Aboriginal students comprise almost one third of the Northern Territory student enrolment (NT DoE, Citation2020). Further, 88% of very remote Aboriginal students learn Standard Australian English as an additional language or dialect at school (Wilson, Citation2014).

Method

This study (approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Melbourne) investigated the influence of remoteness and language background on Year 3 Aboriginal students’ performance on the FELA-NT. Remoteness indicators were derived from the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+) (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], Citation2016) in the national census data. The Northern Territory has three categories: outer-regional, remote, and very remote. The FELA-NT was administered to 72 Year 3 Aboriginal students from eight schools in five regions of the Northern Territory including outer-regional, remote, and very remote schools.

Parents were asked to identify their child’s first language (L1) and students’ language backgrounds were grouped using Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority ([ACARA], Citation2014) categories of English language learners. This study included: 21 Aboriginal students who speak Standard Australian English (SAE) as their L1, 27 Aboriginal English speakers who learn English as an Additional Dialect (EAD) (i.e. students who speak Aboriginal English as their L1), 19 Aboriginal language and 5 Kriol speakers who learn English as an Additional Language (EAL).

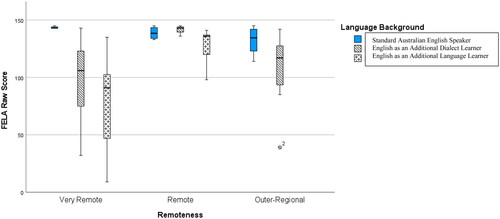

The descriptive statistics associated with FELA-NT test performances across the three language background groups are reported in . On average, the SAE group achieved the highest scores (M = 135.10), the EAD group had the next highest mean (M = 104.01) and EAL (M = 88.58) students had the lowest group score on average. presents the distribution of total FELA-NT scores by level of remoteness and language background. The SAE students from remote and very remote communities performed on par with their SAE peers who attend urban schools indicating that remoteness alone did not explain the early literacy outcomes of these students.

Figure 1. Foundations of Early Literacy Assessment - Northern Territory raw scores by category of remoteness and language background.

Table I. Mean Foundations of Early Literacy Assessment - Northern Territory scores by student language background.

A one-way between groups ANOVA was performed to test if student language background had a statistically significant effect on total FELA-NT scores. The assumption of normality was evaluated and determined to be within acceptable limits for skew < |2.0| and kurtosis < |9.0| (Schmider et al., Citation2010; ). The Welch and Brown-Forsythe tests were used because these tests are robust for testing models that violate assumptions of homogeneity of variances and equality of sample size.

Result

Both the Welch and Brown-Forsythe tests found a statistically significant difference among the groups Welch F(2, 37.91) = 23.58, (p < 0.001) and Brown-Forsythe F(2, 51.07) = 13.86, p < 0.001). A Games-Howell post hoc test found that the mean FELA-NT total scores for both the EAD and EAL groups were statistically significantly different from the SAE group ().

Table II. Mean difference between the Foundations of Early Literacy Assessment - Northern Territory scores by students speaking SAE with students from EAD and EAL backgrounds.

These analyses found that the FELA-NT test performances of students learning English as an Additional Language (EAL) or Dialect (EAD) were on average different (with statistical significance) from Aboriginal students speaking Standard Australian English as their L1. This study indicates that the diversity of students’ performance is due to students’ language background.

Discussion

Rather than problematise the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students, this research presents a within-population analysis of Aboriginal students’ test performances. Students’ language background impacted significantly on their assessment outcomes – those who were Standard Australian English speakers performed to year level expectations regardless of remoteness. Overlooking the influence of students’ language background is not a new development. For example, Wilson (Citation2014) in his review of Aboriginal education in the Northern Territory noted that the influence of student language background was a “factor missing from the analysis in the draft report” (p. 56). The final review recognised the need to consider language background as a key factor when determining approaches to adopt in the education of Aboriginal children.

Our findings suggest that the foundational early English literacy milestones are typically being acquired later by Year 3 Aboriginal students who speak an Aboriginal language, Kriol or Aboriginal English as their first language when compared to their SAE-speaking peers. Research with multilingual learners has shown that English language learners can master early English literacy skills at the same rate as their English-speaking peers in the primary grades (e.g. Lesaux & Siegel, Citation2003; Limbos & Geva, Citation2001) in schools where all children are provided with intensive and systematic instruction in both oral English and early reading skills (Gersten et al., Citation2007).

To meet SDG 4, target 4.6, to “ensure that all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women, achieve literacy” (United Nations, Citation2015), further research into the teaching and learning of foundational early English literacy skills in the remote and very remote Northern Territory Aboriginal education contexts is required. The diversity of Aboriginal English language learners’ test performances is a reflection of the fact that these learners are proceeding along different learning pathways which do not conform with a one size fits all framework.

The ACARA says students who are not achieving minimum standards do not have the foundational skills needed to succeed at schooling and beyond. Because Australian educational systems are designed around minimum standards, it creates a normative framing whereby diversity and difference is seen as a problem to be fixed. Lo Bianco and others (see Devlin et al., Citation2017), have argued this leads to a focus on English instruction in pursuit of common year level norms. If we truly seek educational excellence, equity, and inclusion for multilingual Aboriginal learners (SDG 4, United Nations, Citation2015), and if we want to “ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome” (SDG 10, target 10.3, United Nations, Citation2015), then we need to ensure Australia’s Aboriginal languages are valued and taught in schools (see Wigglesworth et al., Citation2018). We also need more research regarding the developmental milestones of linguistically diverse student groups.

We can no longer set the same benchmarks for all student groups. To reduce inequity as stated in SDG 10, targets 10.3 and 10.2 (United Nations, Citation2015) we need to engage in research to develop nuanced evidenced-based practice that better meet the diverse learning needs and trajectories of linguistically diverse English language learner groups. We call for research and action around English language learner pathways for Aboriginal students to meet SDG 11, target 11.4, to “strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage” (United Nations, Citation2015).

Summary and conclusion

To advance SDG 4, SDG 10 and SDG 11 (United Nations, Citation2015), we need a change of perspective regarding the assessment of Aboriginal students and their English language learning. The power of assessment is unlocked when it is “informative for teaching and beneficial for learning” (Macqueen et al., Citation2019, p. 281). To truly empower Aboriginal students and reduce inequalities of outcome, we must first recognise that most of the remote Aboriginal students in the Northern Territory are multilingual.

We need to move away from the discriminatory policies and practices which apply standards designed for students from monolingual speaking backgrounds to students learning English as an additional language or dialect in foreign language contexts. A more nuanced approach to assessing early language and literacy skills is crucial, and the assessment measures used to determine educational progress must promote both equity and excellence for all (Education Council, Citation2019).

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016). Defining remoteness areas. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Latestproducts/1270.0.55.005Main%20Features15July%202016

- Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2014). English as an additional language/dialect teacher resource. https://tinyurl.com/ep4u48m3

- Cumming, J., Goldstein, H., & Hand, K. (2020). Enhanced use of educational accountability data to monitor educational progress of Australian students with focus on Indigenous students. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 32, 29–51. doi:10.1007/s11092-019-09310-x

- Devlin, B., Disbray, S., & Devlin, N. (2017). History of bilingualism in the Northern Territory. Singapore: Springer.

- Dockett, S., Perry, B., & Kearney, E. (2010). School readiness: What does it mean for Indigenous children, families, schools and communities? Canberra: Australian Institute for Health and Welfare. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/school-readiness-what-does-it-mean-for-indigenous/related-material

- Education Council (2019) Alice springs (Mparntwe) education declaration. Melbourne: Education Services Australia. https://www.dese.gov.au/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration/resources/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration

- Ford, M. (2013). Achievement gaps in Australia: What NAPLAN reveals about education inequality in Australia. Race Ethnicity and Education, 16, 80–102. doi:10.1080/13613324.2011.645570

- Freeman, L.A., & Staley, B. (2018). The positioning of Aboriginal students and their languages within Australia’s education system: A human rights perspective. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 174–181. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1406003

- Gersten, R., Baker, S. K., Shanahan, T., Linan-Thompson, S., Collins, P., & Scarcella, R. (2007). Effective literacy and English language instruction for English learners in the elementary grades: A practice guide. Washington, DC: Institute of Educational Sciences. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED497258.pdf

- Lesaux, N.K., & Siegel, L.S. (2003). The development of reading in children who speak English as a second language. Developmental Psychology, 39, 1005–1019. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1005

- Limbos, M.M., & Geva, E. (2001). Accuracy of teacher assessments of second-language students at risk for reading disability. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34, 136–151. doi:10.1177/002221940103400204

- Lo Bianco, J. (1987). National policy on languages. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

- Marika, R. 1999. The 1998 Wentworth lecture. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 1, 3–9. https://aiatsis.gov.au/publication/117084

- Macqueen, S., Knoch, U., Wigglesworth, G., Nordlinger, R., Singer, R., McNamara, T., & Brickle, R. (2019). The impact of national standardized literacy and numeracy testing on children and teaching staff in remote Australian Indigenous communities. Language Testing, 36, 265–287. doi:10.1177/0265532218775758

- Neilson, R. (2016). FELA foundations of early literacy assessment manual. Jamberoo, Australia: Roslyn Nielson.

- Northern Territory Department of Education (NT DoE). (2020). Annual report 2019–20. Darwin: Northern Territory Government. https://education.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/943959/doe-annual-report-2019-2020.pdf

- Paradis, J., & Jia, R. (2017). Bilingual children’s long‐term outcomes in English as a second language: Language environment factors shape individual differences in catching up with monolinguals. Developmental Science, 20, e12433. doi:10.1111/desc.12433

- Ralph, A. P., Lowell, A., Murphy, J., Dias, T., Butler, D., Spain, B., Hughes, J. T., Campbell, L., Bauert, B., Salter, C., Tune, K., & Cass, A. (2017). Low uptake of Aboriginal interpreters in healthcare: Exploration of current use in Australia's Northern Territory. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 733. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2689-y

- Schmider, E., Ziegler, M., Danay, E., Beyer, L., & Bühner, M. (2010). Is it really robust? reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption. Methodology, 6, 147–151. doi:10.1027/1614-2241/a000016

- United Nations (2015). Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- Wigglesworth, G., Simpson, J., & Vaughan, J. (2018). Language practices of Indigenous children and youth: The transition from home to school. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Wilson, B. (2014). A share in the future: Review of Indigenous education in the Northern Territory. Melbourne: Northern Territory Department of Education. https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A65033