Abstract

Purpose

This paper presents an analysis of interpersonal identity-based violence experienced by persons with communication disabilities in Iraq and the barriers reported to accessing supports. The use of communication accessible data collection tools is discussed as a means of enabling an inclusive response for multiple marginalised groups in relation to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 16 and 5.

Result

People with communication disabilities reported similar levels of interpersonal violence to those with disabilities of other types, characterised by high rates of deprivation and physical violence. Many participants did not seek support, but those that did were most likely to speak to a family member or friend, followed by consulting legal services. Barriers to accessing support were varied, with lack of transport being the most commonly reported. Satisfaction with research communication supports was high for all participants, including those with no communication difficulties, suggesting that the resources invested in communication access have benefits beyond those with communication disabilities.

Conclusion

Iraqi persons with communication disabilities, like those with other disabilities, face high levels of interpersonal violence. The use of communication supports in research addressing disability is likely to increase the representation of persons with communication disability in study samples and can benefit participants with other disabilities. This commentary paper, available in Arabic as a supplemental file, focusses on SDG 16 and also addresses SDG 5.

ملخص

غاية: تقدم هذه الورقة تحليلاً للعنف القائم على الهوية الشخصية الذي يعاني منه الأشخاص الذين يعانون من إعاقات التواصل في العراق والعقبات التي تم الإبلاغ عنها أمام الحصول على الدعم

تتم مناقشة استخدام أدوات جمع البيانات التي يمكن الوصول إليها للاتصال كوسيلة لتمكين استجابة شاملة للفئات المهمشة المتعددة فيما يتعلق بأهداف التنمية المستدامة (SDGs) 16 5,

النتائج: أبلغت النتائج عن مستويات مماثلة من العنف الشخصي لذوي إعاقات التواصل من أنواع أخرى، والتي تتميز بارتفاع معدلات الحرمان والعنف الجسدي. لم يسع العديد من المشاركين إلى الحصول على الدعم، ولكن أولئك الذين فعلوا ذلك كانوا على الأرجح يتحدثون إلى أحد أفراد الأسرة أو الأصدقاء ، تليها خدمات استشارية قانونية. كانت العوائق التي تحول دون الحصول على الدعم متنوعة، وكان نقص وسائل النقل هو الأكثر شيوعًا. كان الرضا عن دعم الاتصالات البحثية مرتفعًا لجميع المشاركين، بما في ذلك أولئك الذين لا يعانون من صعوبات في التواصل، مما يشير إلى أن الموارد المستثمرة في الوصول إلى الاتصالات لها فوائد تتجاوز أولئك الذين يعانون من صعوبات في التواصل

الخلاصة: يواجه الأشخاص العراقيون الذين يعانون من إعاقات في التواصل، مثل ذوي الإعاقات الأخرى، مستويات عالية من العنف الشخصي. من المرجح أن يؤدي استخدام وسائل التواصل في البحث الذي يتناول الإعاقة إلى زيادة تمثيل الأشخاص ذوي الإعاقة في التواصل في عينات الدراسة ويمكن أن يفيد المشاركين من ذوي الإعاقات الأخرى. هذه الدراسة، المتوفرة باللغة العربية كملف تكميلي، تركز على هدفين من أهداف التنمية المستدامة، وهي هدف رقم 16 والهدف رقم 5 أيضاً

Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a set of 17 interrelated goals adopted by the United Nations in 2015, have at their heart a central, transformative principle to “leave no one behind” in pursuing the agenda to “end discrimination and exclusion and reduce inequalities and vulnerabilities” (United Nations, Citation2015). This commentary focuses on peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG 16), specifically targets 16.1 and 16.3 which set out indicators regarding reducing exposure to violence, and increasing reporting by victims respectively. In addition the paper addresses gender equality (SDG 5), target 5.6, to “ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health”, which arguably extends to all relevant services for those exposed to identity-based violence.

Persons with disabilities face an elevated risk of exposure to interpersonal violence (Hughes et al., Citation2012), including those with communication disabilities (Marshall & Barrett, Citation2018). For the purposes of this paper disability is conceptualised in line with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD, United Nations, Citation2006), to be an interaction between an impairment and barriers in the environment that prevent full participation on an equal basis with others. The term communication disability is distinguished to identify a subset of persons with disabilities who experience difficulties in understanding others or effectively and efficiently making themselves understood when using a preferred language. In Iraq, a country that has been subjected to two decades of near constant conflict, high levels of domestic violence against women have been documented (e.g. Mahmood, Citation2022), but data specific to persons with disabilities, including those with communication disabilities, are lacking. This is a critical gap, as although disability statistics in the country are contested (IOM, Citation2021), disability prevalence in complex emergency situations, such as experienced in Iraq, is likely to be higher than the global average of 15% (IASC, Citation2019). The data gap for persons with communication disabilities requires a particularly proactive response as this population is underrepresented in social science research in general, both through explicit exclusion as well as passively, due to exclusion criteria on the one hand and inaccessible data collection methods (i.e. high communication demands) on the other (Jagoe et al., Citation2021). This invisibility in research risks exacerbating exclusion from services and policies aimed at supporting victims of violence. For these reasons, addressing the communication demands in research on disability and interpersonal violence is critical if the needs of those with communication disabilities are to be considered. Universal Design is defined as design that may be accessed, understood and used by the widest range of people in the most natural manner, without the need for adaptation (Irish Disability Act, Citation2005). Applying this approach to communication access in disability research may allow for persons with communication disabilities to be more readily represented in social science research.

The purpose of this commentary is twofold: (a) to demonstrate, as “proof-of-concept” that the use of communication accessible data collection tools within “general” disability research (i.e. not specific to communication disability) functions to optimise the inclusion of persons with communication disabilities, while also being valued by other participants; (b) to present the findings on interpersonal violence and communication disability.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was gained from Heartland Alliance International Institutional Review Board – approved 5 June 2020 and Iraq Human Rights Commission – Mr Faisal Abdullah, Iraqi High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Method

This commentary draws on interview data from persons with communication disabilities who participated in a larger mixed methods study among persons with disabilities in three Iraqi cities. The study was conducted by Heartland Alliance International in collaboration with the Iraqi Alliance of Disability Organizations and explored experiences of identity based interpersonal violence for persons with disabilities, and barriers to accessing support. The term interpersonal, identity-based violence (IBV) was used to capture “violence carried out because of a person’s simultaneous and intersectional identities, [recognising] that violence against men and women with disabilities may manifest in ways which current, Western-centric definitions do not encompass” (James et al., Citation2022)

Data were collected in early 2021 through semi-structured interviews with individuals with disabilities. The larger project also comprised an online survey for service providers and focus group discussions but no participants had communication disabilities and the data is not reported here. Interview data were collected by six enumerators, all persons with disabilities, who worked in three gender-balanced pairs, recruited through plain language job adverts and local Organisations of Persons with Disabilities (OPDs). Participants were recruited through snowball sampling using networks known to enumerators, OPDs and the Iraqi Alliance of Disability Organisations. The data presented in this commentary are a subset of the participants engaged in the larger study, specifically those with communication disabilities, on four components of the semi-structured interview: (a) a set of demographic questions, (b) self-report of functional limitations (disability) using the Washington Group Short Set of Questions (Washington Group on Disability Statistics, Citation2020), (c) investigator designed questions on personal exposure to identity-based violence and (d) investigator designed questions on the services accessed and barriers experienced. A full description of the methodology is outlined in James et al. (Citation2022).

Accessible data collection tools and training of enumerators

Although this study was not focussed specifically on persons with communication disabilities, the study team were committed to ensuring that this heterogenous group could participate. Two measures were taken to facilitate participation: (a) development of communication accessible data collection tools, and (b) training of enumerators in how to use communication supports.

Draft communication supports were developed for four components of the study procedure: (a) communication accessible informed consent form; (b) picture-supported version of the WG-SS including a visual response scale; (c) picture supports for discussion of services related to interpersonal violence; (d) picture supports for discussion of barriers to accessing supports. Each of these tools was reviewed and revised during a methods development workshop with enumerators (see Supplemental File 2 for examples of the revisions and the tools). None of the enumerators had communication disabilities, a notable limitation in the development of the materials. The workshop took place over 2.5 days and was facilitated in-person by three of the researchers (COR, EK and HA), with hybrid online input from other members of the team who were unable to travel due to the COVID-19 pandemic (CJ and LEJ). Interpretation from English into Iraqi Sign Language, Kurdish and Arabic was provided.

Training in the use of the communication supports was provided to the enumerators by one of the collaborators (CJ), a speech-language pathologist (speech and language therapist) with extensive experience in communication access and communication partner training. The training included a background to communication disability, the principles of supported conversation, and the use of the tools with people with different levels of education and literacy. Role-plays were used to establish skills in the use of the tools.

Participant sample

A total of 242 persons with a range of disabilities participated in the semi-structured interviews. All participants engaged in the same version of the interview, involving the use of the communication-accessible tools described above. To determine whether participants had a communication disability, each was asked “Using your usual language, do you have difficulty communicating, for example understanding or being understood?” (WGS, 2020). This commentary focuses on the analysis of two sub groups: (a) participants with a communication disability (COMM1), identified here as those respondents reporting at least “a lot of difficulty” in the communication domain of the WG-SS, and (b) participants reporting “some difficulty” (COMM2) in this communication domain. Difficulties related to communication were reported by 93 respondents (38.4% of the total sample), of whom 80 (86%) had other types of disabilities in addition to communication disability. Persons with communication disabilities who had “a lot of difficulty” communicating (i.e. COMM1) made up 8.3% (n = 20) of the total sample, with 30.2% (n = 73) reporting “some difficulty” (i.e. COMM2) in the communication domain (). The remaining 149 were persons with other disabilities (no communication impairment).

Table I. Participant characteristics.

Results

Reflections on communication accessible methods: Communication disability and beyond

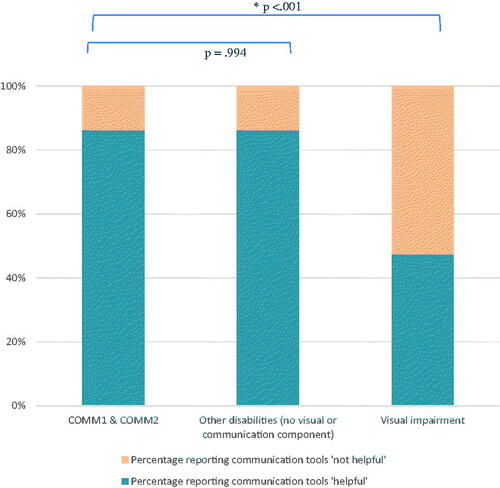

Given the additional resources require to develop communication accessible tools, we explored the response of all 242 participants to the accessible materials. The majority of participants reported that the communication supports were helpful (76.9%; n = 186). Benefits were reported by 68.8% (n = 64) of COMM1 and COMM2, and 81.8% (n = 122) of those with other disabilities (no communication impairment). This difference was significant at p < 0.05 (χ2 (1; n = 242) = 5.493; p = 0.019). The difference disappeared when visual impairment was accounted for (χ2 (1; n = 242) = 2.316; p = 0.128), suggesting, as would be expected, that the materials were significantly less helpful for those with visual impairment (). Nevertheless, 42.4% of people with a visual impairment reported finding the materials helpful, which may reflect additional explanation provided by enumerators to substitute for the visual support, or a desire by respondents to respond positively to the enumerator. Respondents who were illiterate were significantly more likely than those with any degree of education to find the picture supports helpful (χ2 (1; n = 242) = 3.968; p = 0.046), but education level for those with primary education or above was not associated with reported helpfulness of communication supports.

Exposure to interpersonal violence for persons with communication disabilities

Exposure to violence was similar (χ2 (2; n = 242) = 2.338; p = 0.311) across the sample, with 65% (n = 13) of COMM1, 80.8% (n = 59) of COMM2, and 78.5% (n = 117) of those with other disabilities reporting previous or current exposure to violence. Comparative data are limited, but these prevalence rates are higher than most of the available data on domestic violence against women in Iraq which range from 26% (World Health Organization, Citation2021) to 38.7% during COVID-19 lockdowns (Mahmood, Citation2021), with other figures as high as 61.6% (Lafta & Hamid Citation2021).

The types of violence experienced were similar for COMM1 and COMM2 with deprivation and physical violence being the most common types reported by both groups (). The category of deprivation violence included any affirmative responses to the question “Has anyone in your life ever prevented your access to things you need to survive, or prevented you from doing things you wanted to?”. Examples included being locked up or prevented from leaving the house, prevented from attending community events, prevented from getting married). Women with communication difficulties of any degree experienced higher rates of violence than those without communication difficulties but this difference was non-significant (χ2 (2; n = 111) = 0.5581; p = 0.455021).

Table II. Reported exposure to violence.

Accessing support: Types of support sought and barriers to access for people with communication disabilities

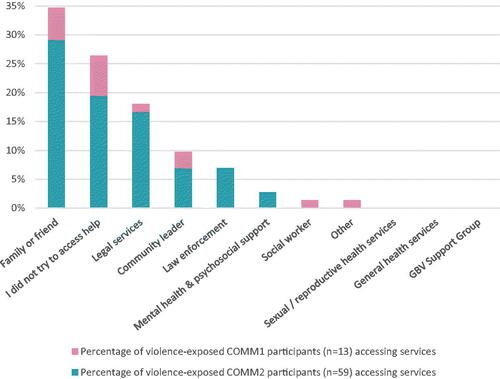

Participants who reported exposure to violence were asked about what support they had sought or would seek. Speaking to a family member or friend was the most frequent support reported, followed by consulting legal services or speaking to a religious or community leader (). Over 25% of COMM1 and COMM2, who had experienced violence, reported that they did not, or would not, try to access support.

Figure 2. Percentage of participants with a communication disability (COMM1) and reporting some communication difficulty (COMM2) seeking supports (of those who experienced violence).

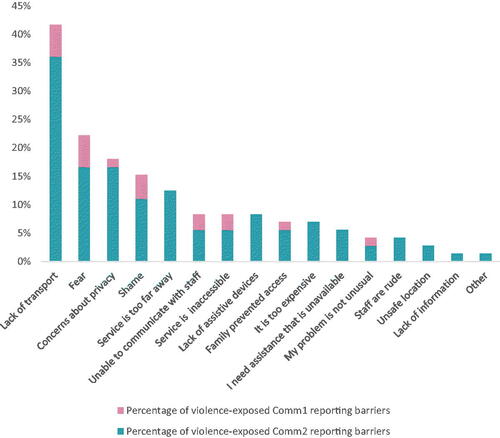

The majority (93%; n = 67) of COMM1 and COMM2 participants had experienced, or feared, barriers in accessing services following exposure to violence. The most frequently reported barriers were a lack of transport, followed by fear and concerns about privacy (). Difficulties communicating with staff were reported by a minority of COMM1 (15.4%; n = 2) and COMM2 (6.8%; n = 4).

Summary and conclusion

Violence against persons with disabilities represents an obstacle to the goals of equality, development and peace. Participants with different degrees of communication difficulty experienced similarly high rates of exposure to interpersonal violence compared to participants with other types of disabilities. Many respondents reported not seeking help, however, when sought, the most frequent supports were informal, such as speaking to friends and family. Barriers to accessing support included a lack of transport, fear and concerns about privacy. These finding suggest a need for service providers to be more proactive in reaching this population and working to create safe spaces and engender trust.

Our findings support the assertion in the literature that communication difficulties are often hidden in the “multiple disabilities” category (e.g. Wylie et al., Citation2013). Here, 90% of those with communication disabilities also had impairments in at least one other WGQ-SS domain. This population therefore faces a double risk of invisibility in data – a risk of being excluded due to data collection methods, and of being hidden in the analysis.

Intentionally developing data collection tools that enable participation of those at the margins addresses inclusion more broadly, demonstrating Universal Design in action. When used by trained enumerators, such materials are helpful for a majority of people with different types of impairments, and persons who are illiterate. Communication-accessible materials take time and expertise to develop, as well as requiring training to be used effectively by enumerators or other staff. The findings of our study suggest that the resource investment is likely off-set by the benefits experienced by participants, including and beyond those with communication difficulties. Speech-language pathologists are well placed to advise on the design and use of such materials.

Reducing all forms of violence (SDG 16) and achieving gender equality (SDG 5) entails inclusion of persons with disabilities in prevention of, and responses to, interpersonal violence. Ensuring that persons with communication disabilities are represented in research on interpersonal violence, and thereby considered in the design of prevention efforts and response services, demands inclusive and accessible research methods. Approaches that centre communication accessibility have an important role to play in ensuring that disability-related data includes those with communication difficulties and leaves no one behind.

Suppplemental_File_2.pdf

Download PDF (227.8 KB)_____Supplemental_File_1.pdf

Download PDF (699.1 KB)Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Government of Ireland. (2005). Disability Act. Dublin, Ireland: Stationary Office. https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2005/act/14/enacted/en/html

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M.A., Jones, L., Wood, S., Bates, G., Eckley, L., … Officer, A. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 379, 1621–1629. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61851-5

- IASC. (2019). Guidelines on inclusion of persons with disabilities in humanitarian action. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2020-11/IASC%20Guidelines%20on%20the%20Inclusion%20of%20Persons%20with%20Disabilities%20in%20Humanitarian%20Action%2C%202019_0.pdf

- IOM. (2021). Persons with disabilities and their representative organizations in Iraq: Barriers, challenges, and priorities. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/OPDs%20report%20English.pdf

- Jagoe, C., McDonald, C., Rivas, M., & Groce, N. (2021). Direct participation of people with communication disabilities in research on poverty and disabilities in low and middle income countries: A critical review. PLoS One, 16, e0258575. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258575

- James, L.E., O’Reilly, C.F., & Jagoe, C. (2022). The many faces of violence: A mixed methods study of identity-based violence among persons with disabilities in Iraq. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Lafta, R.K., & Hamid, G.R. (2021). Domestic violence in time of unrest, a sample from Iraq. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 37, 205–220. doi:10.1080/13623699.2021.1958477

- Mahmood, K.I., Shabu, S.A., M-Amen, K.M., Hussain, S.S., Kako, D.A., Hinchliff, S., & Shabila, N.P. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 related lockdown on the prevalence of spousal violence against women in Kurdistan region of Iraq. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37, NP11811–NP11835. doi:10.1177/088626052199792

- Marshall, J., & Barrett, H. (2018). Human rights of refugee-survivors of sexual and gender-based violence with communication disability. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 44–49. doi:10.1080/17549507.2017.1392608

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Treaty Series, 2515, 3. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-withdisabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. (2020). The Washington Group Short Set on Functioning. https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/question-sets/wg-short-set-on-functioning-wg-ss/

- World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/341337

- Wylie, K., McAllister, L., Davidson, B., & Marshall, J. (2013). Changing practice: Implications of the World Report on Disability for responding to communication disability in under-served populations. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 1–13. doi:10.3109/17549507.2012.745164