Abstract

Purpose

This scoping review advocates for integrated approaches to the architectural design of education and health environments for children and young people, driven by diverse stakeholder perspectives.

Result

Limited empirical research specifically focuses on children and young people’s direct involvement in architectural design decision-making processes. Few studies specifically include those experiencing communication disability, or articulate universal strategies to facilitate accessible consultation processes. Despite international agreement of the importance of children and young people’s participation in decision-making (e.g. Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs]), there is limited application in architectural design consultation. Development of consistent guidance supporting inclusive, accessible co-design processes for all potential users and decision-makers is crucial.

Conclusion

It is necessary to integrate perspectives of those habitually marginalised or excluded from consultation processes, including children experiencing communication disability or with alternative communicative preferences. Doing so amplifies the imperatives articulated in the SDGs, specifically those relating to inclusivity and representativeness in decision-making (SDG 16.7), and designing and building inclusive, safe, child and disability-friendly environments (SDG 4a). This article addresses good health and well-being (SDG 3); quality education (SDG 4); sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11); peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG 16).

Introduction

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a global call to action requiring nations to actively implement strategies that promote inclusion, equality, and prosperity. Goals include providing quality education (SDG 4), good health and well-being (SDG 3), representative decision-making (SDG 16.7), and sustainable communities (SDG 11) (United Nations, Citation2015).

Children’s views about the built environments which they inhabit are noticeably absent in existing literature. Within this limited literature, few studies articulate whether or how they support inclusion of diverse views, particularly when modifications to standard consultative processes may be necessary. While 90% of students with disability in Australia attend mainstream schools (AIHW, Citation2020), few are explicitly included in schoolbuilding decision-making or consultation processes. Architecture (also referred to as building/s or built environment in this article) has a direct impact on users’ abilities to move, see, hear, and communicate effectively. Consequently, the accessibility of built environments may be impeded for some users, such as children experiencing communication disability, who already experience significant barriers to their perspectives being sought and acted upon, daily (Lyons et al., Citation2022).

Inclusive architecture, however, actively promotes built environments that everyone can identify and interact with; enabling equal, confident, and independent participation and contribution. This article adopts the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, United Nations, Citation1989) definition of children as incorporating people under 18 years of age. Children have the right to contribute to the design of their school, health, and community environments, with several studies demonstrating techniques to facilitate their involvement (e.g. Könings et al., Citation2017; Robinson & Notara, Citation2015; Woolner et al., Citation2010). Despite the UNCRC advocating for all children’s right to be included in decision-making about matters affecting them, their participation in architectural consultation, briefing, design, and service delivery processes remains limited.

Co-design facilitates processes that extend seeking children’s contribution to design, to cultivate empowered, participatory, and heroic “protagonists” (Iversen et al., Citation2017, p. 27). Inclusive co-design with and for children, requires intentionality to support the participation of all stakeholders, particularly those whose communicative abilities may require adjustments to traditional consultation methods (Isele & Mussi, Citation2021).

This scoping review provides evidence that, in the published literature relating to the design of built environments supporting children’s education, health, and wellbeing: (1) the perspectives of children with communication disability are largely absent; and (2) diverse methods are required to ensure inclusive stakeholder consultation. The article concludes by proposing that inclusive co-design practices with children experiencing communication disability, can be enabled through architectural applications which are strategically aligned with focus SDGs.

Children experiencing communication impairment

More than 1.2 million Australians experience communication disability, with varying levels of impairment and children under the age of 12 make up at least 11% of Australians experiencing communication disability (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2015). Children experience communication disability with known and unknown origins, including with speech, language, voice, fluency, and/or hearing. Communication disabilities in children may also be underdiagnosed. For example, the prevalence of students who meet communication disability diagnostic criteria such as developmental language disorder (DLD), but remain undiagnosed, likely affects “around two students in every classroom”, making this a “hidden disability” that is “hiding in plain sight” (Tancredi, Citation2020, p. 203). Underdiagnosis implies that when general consultation processes with children do occur, it is likely that children with communication disability are unintentionally involved, even if they are not explicitly identified or supported as participants.

Whether specifically seeking participation from children and young people who experience communication disability or not, the minimum standard for ensuring children’s Article 12 rights to have their views sought and taken seriously, must be met (United Nations, Citation1989). Consequently, all consultation about children’s environments should already intentionally embed inclusive principles from the outset, through purposefully inviting and supporting their participation, therefore resulting in enhanced understanding of the perspectives of diverse future users of these spaces.

Perspectives in architectural design consultation

This review used systematic processes to investigate: How do studies that seek children’s perspectives on the architectural design of their future education, health, or wellbeing environments, include children with communication disability?

Searches were conducted in October 2021 and updated in April 2022. EBSCO databases in education, health, medicine, psychology, and architecture were searched for combinations of design (e.g. participatory/co-design/charrette), children (e.g. student/youth/child/adolescent/teenager), and architecture (e.g. built-environment/building/architecture), resulting in 385 studies across 14 databases. Titles and abstracts of each record were screened, to identify empirical studies aligned with the following inclusion criteria: (1) relating to education and/or school and/or health and/or wellbeing; (2) involving children and/or school-aged students and/or young people; (3) including architecture and/or built environment and/or physical environment; and (4) incorporating stakeholder consultation.

Given the dearth of prospective studies, a broad view of each inclusion criteria was applied. Studies were excluded if the full text was a duplicate (n = 164), or not available in English (n = 1). Independent screenings of all records were calibrated, and discrepancies were deliberated, by both authors. After screening, 27 studies remained for full-text screening, of which an additional eight studies were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Full-text analyses were conducted on the final set of 19. Only four of these publications specifically referenced disability, inclusive communication, or non-verbal communication during architectural design consultation (Könings et al., Citation2017; Martins & Gaudiot, Citation2012; Robinson & Notara, Citation2015; Woolner et al., Citation2010). The sections that follow provide an overview of the implicit and explicit strategies used across these studies, that provide support for the involvement of children experiencing communication disability.

Strategies for including diverse perspectives

Children and adults were identified as stakeholders in each analysed study. Some studies identified children with disability based on impairment or health condition (e.g. autism, speech, and hearing). Other studies inferred disability or additional communication considerations within recruitment descriptions (e.g. proportion of children with learning difficulties or additional languages). Studies also included personal and/or cultural support workers (e.g. Indigenous representatives; interpreters/sign language users), parents/community members, and school staff – these participants were either: (1) stakeholders; (2) supporting inclusion of participants (e.g. interpreters); (3) speaking on behalf of target participant groups (e.g. parents interpreting non-verbal children’s communication, community elders); or (4) identified with target group characteristics (e.g. older deaf children). Diverse perspectives from multiple stakeholders were endorsed as beneficial to design consultation.

While stakeholder participation varied through design phases (e.g. who is involved, to what extent), facilitating their engagement at key times provided critical and empowering opportunities for child participants. Some engagements occurred over multiple sessions, using diverse methods with participant groups (depth), while others engaged more participants on fewer occasions (breadth). Some consulted with sub-groups for specific insights (width), or during pre-design recruitment consultation, for tailored strategies (appropriateness). Certain studies consulted with participants during all design phases, including dissemination. An additional strategy that increased inclusion without placing undue strain (e.g. time, financial) on particular stakeholder groups (e.g. children experiencing communication disability), was the inclusion of stakeholder subgroups in components of participatory design.

Ensuring consultation methods are accessible for all participants – especially those with additional communication needs – is critical to supporting the empowerment of otherwise marginalised or excluded groups, to ensure inclusive, accessible design. Benefits of incorporating perspectives of children with disability included: understanding the complexity of their needs; strengths-based positioning as valuable contributors and experts of their own experience; and ensuring equity and empowerment in consultation participation. The studies used various data collection methods, including: surveys/questionnaires, interviews, focus groups, drawings, photo elicitation, mapping, embedding within educational curriculum, creative workshops, student-as-researcher/action-research, observation, and spatial walk-throughs. Some inclusive strategies were intentionally embedded, such as inviting non-language (neither written nor spoken) responses or using visual methods. Where an intention to apply the approach in other contexts was identified in studies, the absence of guidelines for engaging with different stakeholders (particularly those often invisible in co-design/consultation), was noted.

As evidenced above, few publications about the design of built environments for children and young people, described intentionally incorporated strategies to support the participation of children experiencing communication disability. The SDGs offer a way to design inclusively with diverse users, rather than focussing exclusively on the end-product. Consequently, the next section documents the alignment of focus SDGs to contextualised architectural applications, and maps the key insights extrapolated from the limited pool of existing publications, to these.

Sustainable development goals and architectural applications

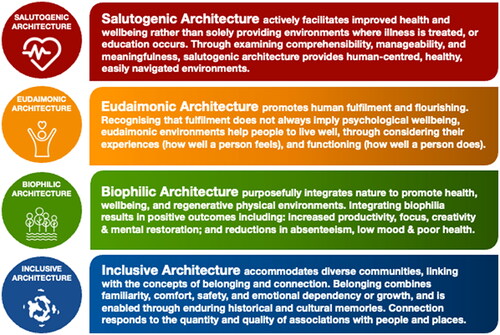

Four SDGs (SDG 3, SDG 4, SDG 11 and SDG 16) were considered appropriate to the research focus. Four distinct architectural design applications – Inclusive, Biophilic, Salutogenic, and Eudaimonic Architecture – were selected to align to the focus SDGs, and then contextualised accordingly as illustrated in .

Finally, key insights about the inclusion of children with communication disabilities in architectural design consultation, were extrapolated from the analysed studies and mapped to the architectural applications and SDGs (as outlined in ).Table I. Key insights mapped to the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and architectural design applications (ADAs).

When considered alongside the SDGs, the application of inclusive, biophilic, salutogenic, and eudaimonic architecture strengthens the participatory design of health and educational built environments, when they are designed inclusively with and for children and young people. This scoping review demonstrates that, while few studies explicitly described how they supported the inclusive design of built environments with children and young people, those studies that did, provide valuable groundwork which architects and designers can respond to and build upon. While people may require different modifications to ensure fully inclusive consultation processes, those already embedding consultation with children offer further insights to others working in this space. Addressing this scarcity of exemplars (also identified by Hall, Citation2017) will help to scaffold the future involvement of children and young people, in the design of their built environments.

Summary and conclusion

Limited research specifically considers and incorporates inclusive strategies to support the participation of children who experience communication disability in architectural design consultation. Inclusive co-design with and for children involves more than simply inviting them to the table. It requires active facilitation of all stakeholders’ involvement, including those whose communicative abilities necessitate modifications to traditional consultation processes. Facilitating consultation that is not wholly reliant on verbal or written communication, empowers and promotes the inclusion of end-users for whom conventional consultation methods are inaccessible. Advancing the SDGs requires explicit focus on diverse stakeholder and decision-maker’s involvement, when developing built environments for young people.

Findings from this scoping review suggest that despite broad international agreement supporting the inclusion of children’s views in decisions affecting them (e.g. UNCRC Article 12; SDG 16.7), there remains a disconnect between systematic integration of these agendas into architectural consultation and decision-making. The practice of those currently engaging and publishing in this field, presents exciting new opportunities that bring together architectural design and inclusive consultation with all young people, with or without disability. The examples considered in this paper propose different ways to include children experiencing communication disability within different stages of built environment design consultation, and specifically when responding to critical international priorities such as the SDGs.

However, additional work is required to ensure inclusive, accessible, and sustainable design that meaningfully engages all potential users, becomes standard practice. Scaffolded guidance for engaging children in inclusive co-design of their own built environments (priority of SDG 4(b) and SDG 16.7) must be developed. To design inclusively with diverse stakeholders, it is necessary to identify who is consulted, and how to effectively consult with them. To ensure effective and inclusive consultative processes in the future, those who hold pieces of this knowledge (such as speech-language pathologists, inclusive educators, and researchers) must actively share their critical insights with architects, designers and others working in these spaces, to build capacity and guide future directions. The co-design of health, wellbeing, or education environments require a change in mindset, to ensure that authentic, efficient, supportive, and empowering places are designed with, not just for, children, their families, and their communities.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Abbe Winter who provided editing support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- AIHW. (2020). People with disability in Australia 2019. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/people-with-disability-in-australia-in-brief/contents/about-people-with-disability-in-australia-in-brief

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2015). 4430.0‐Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings, 2015. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Hall, T. (2017). Architecting the ‘third teacher’: Solid foundations for the participatory and principled design of schools and (built) learning environments. European Journal of Education, 52, 318–326. doi:10.1111/ejed.12224

- Isele, P.C., & Mussi, A.Q. (2021). Inclusive architecture: Landscape codesign in children’s playgrounds. Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 15, 429–436. doi:10.17265/1934-7359/2021.08.004

- Iversen, O.S., Smith, R.C., & Dindler, C. (2017). Child as protagonist: Expanding the role of children in participatory design. In P. Blikstein & D. Abrahamson (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2017 conference on interaction design and children (pp. 27–37). New York, NY: ACM.

- Könings, K.D., Bovill, C., & Woolner, P. (2017). Towards an interdisciplinary model of practice for participatory building design in education. European Journal of Education, 52, 306–317. doi:10.1111/ejed.12230

- Lyons, R., Carroll, C., Gallagher, A., Merrick, R., & Tancredi, H. (2022). Understanding the perspectives of children and young people with speech, language and communication needs: How qualitative research can inform practice. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24, 547–557. doi:10.1080/17549507.2022.2038669

- Martins, L.B., & Gaudiot, D.M. (2012). The deaf and the classroom design: A contribution of the built environmental ergonomics for the accessibility. Work, 41, 3663–3668. doi:10.3233/WOR-2012-0007-3663

- Robinson, S., & Notara, D. (2015). Building belonging and connection for children with disability and their families: A co-designed research and community development project in a regional community. Community Development Journal, 50, 724–741. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsv001

- Tancredi, H. (2020). Meeting obligations to consult students with disability: Methodological considerations and successful elements for consultation. Australian Educational Researcher, 47, 201–217. doi:10.1007/s13384-019-00341-3

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. https://www.ohchr.org/en

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- Woolner, P., Clark, J., Hall, E., Tiplady, L., Thomas, U., & Wall, K. (2010). Pictures are necessary but not sufficient: Using a range of visual methods to engage users about school design. Learning Environments Research, 13, 1–22. doi:10.1007/s10984-009-9067-6