Abstract

Purpose

This paper contextualises a keynote address delivered at the 2022 Speech Pathology Australia National Conference in Melbourne, Australia. The paper aligns with the conference theme of Beyond Borders from the perspective of moving beyond borders of regular practice to develop strong partnerships and networks within our communities to advocate and support necessary change.

Method

Change or enhancement to current practice is necessary if we are to reduce current inequities in education experienced by many children in our communities, including those with communication challenges. Strengths-based and culturally responsive literacy approaches to supporting children within the context of their family and community are increasingly gaining support as we address this challenge. The Better Start Literacy Approach (Te Ara Reo Matatini), currently being implemented in junior school classrooms across New Zealand is described. It is one example of large-scale implementation of a strengths-based and culturally responsive early literacy approach, based on the science of reading.

Result

Data support the effectiveness of the Better Start Literacy Approach in significantly enhancing the foundational literacy skills of 5- and 6-year-old children, including those who commence school with lower levels of oral language ability.

Conclusion

Through establishing strong partnerships within communities, speech pathologists have much to offer in motivating systems level change to enhance early literacy success for all learners.

Introduction

Beyond Borders was a very timely theme for the Speech Pathology Australia 2022 National Conference. As state and international borders reopened following a lengthy period of COVID-19 pandemic travel restrictions, the theme reminded conference delegates of the power of in-person connections. Many people moved beyond their home borders to be physically present for the conference. Kanohi ki to kanohi: This is a Māori phrase referring to face-to-face communications. This concept is a core principle of Māori ways of doing and knowing. Face-to-face communication allows our senses to be engaged in the communication activity and supports the building of trusting and meaningful relationships (Ngata, Citation2017). Yet our digitally enhanced world creates opportunities to adapt, connect, and communicate in a multitude of ways. In speech pathology, we rightly embrace all forms of communication while being respectful of the value and power of kanohi ki to kanohi as we move beyond our borders and broaden our professional networks.

In my keynote conference address, I interpreted the conference theme from the perspective of challenging us to move beyond our borders of regular clinical practice—to move beyond the borders of our research labs, classrooms, speech clinics, health centres, or universities to connect and communicate in meaningful ways with our communities. It is through developing strong partnerships and networks within our communities, in culturally responsive ways, that we can best advocate and support necessary change. My focus in my address was on advocating for change to advance a shared global vision for a literate world for all peoples (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Citation2022).

The World Health Organization (Citation2020) recently highlighted the importance of building meaningful partnerships with our communities to advance literacy capacity building. In their call to action they stated:

We must reimagine the way(s) in which we communicate with communities and invest resources in accessible infrastructure, services, and comprehensive literacy capacity building. Governments and multilateral organizations must invest in transliteracy, ensuring that diverse communities have the resources and skills necessary to access, understand, and critically analyze and/or assess information, especially as it relates to their health and wellbeing. World Health Organisation (Citation2020).

Advocating for change or enhancement to current literacy teaching practices

An individual’s successful literacy achievement is a powerful and cumulative protective factor for positive life outcomes (Ritchie & Bates, Citation2013; Saha, Citation2006). We know that literacy is more than just learning to read and write. However, competency in basic reading skills is a powerful predictor of later reading and education achievement (Cunningham & Stanovich, Citation1997; Tunmer et al., Citation2006). Early literacy success supports more comprehensive literacy abilities that include critical literacy and multiliteracy skills (e.g. the ability to critically analyse information that may be presented in different formats, see Sharp, Citation2012). Such skills are vital to an individual’s education, health, and wellbeing in our rapidly advancing digital information world. The importance of comprehensive and critical health literacy skills was highlighted during the pandemic crisis (World Health Organization, Citation2020).

Advancing literacy achievement for all children is essential to address complex challenges of reducing current education and health inequities. Although global literacy rates are rising, very modest gains are being made to reduce education inequities for some subpopulations (e.g. children from low socioeconomic areas, see Hanushek et al., Citation2022). The literacy gap may indeed be widening for some children who have low literacy achievement in the early school grades (D’Agostino & Rodgers, Citation2017). Limited gains towards raising literacy achievement for those most in need has been further compounded through the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2021, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) estimated that more than 168 million children were unable to attend school in person for a full year due to school closures (UNICEF, Citation2021). Current analysis from data from 49 states across the United States of America suggests that the shift to remote and hybrid learning during 2020–2021 had “profound consequences for student achievement” (Goldhaber et al., Citation2022, p. 14). Achievement for students attending schools in areas of high poverty, who are English language learners, and students with disabilities has been particularly adversely impacted by COVID-19 pandemic school disruptions (Relyea et al., Citation2023). High levels of student absenteeism have also been reported globally, even when schools have reopened post school lockdown periods. Even relatively short periods of school lockdown such as those experienced in Tasmania, Australia, may have adversely affected learning experiences for children from low socioeconomic areas (Tomaszewski et al., Citation2023).

The impact of such severe disruptions to children’s learning threatens our ability to meet global education goals against the United Nations 2030 agenda for sustainable global development (United Nations, Citation2015). A literate population is necessary to support the realisation of all of the sustainable development goals. However, limited progress on literacy achievement goals particularly threatens our realisation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all (United Nations, Citation2015). There is a critical and urgent need then to ensure education systems can support large scale implementation of effective and evidence-based literacy approaches to help address these current global literacy challenges.

Role of speech pathologists

Speech pathologists’ role in supporting children’s literacy development is strongly advocated (e.g. Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2011; Snow, Citation2016; Erickson, Citation2017). Children with communication challenges frequently demonstrate delayed early reading development placing them at risk for long term disadvantage (Schuele et al., Citation2007). For example, research investigations have identified literacy risk factors for specific subgroups of children with speech sound disorder. Children who have consistent, atypical speech error patterns are at particular risk for literacy problems, whereas children with inconsistent speech error patterns may be more at risk for spelling problems (Holm et al., Citation2008). Children who have childhood apraxia of speech (McNeill et al., Citation2009), and children with both speech and language disorder or a genetic disposition for dyslexia (Hayiou-Thomas et al., Citation2017) are at highentend risk for persistent literacy challenges.

Findings of Catts et al. (Citation2008) indicated that although classroom instruction advances reading development in children with speech and language disorder, it does not result in these children showing the accelerated reading growth necessary to overcome their early reading delays. They, therefore, reach much lower levels of reading achievement compared to their peers in the upper grades, which creates education inequities. McLeod et al. (Citation2019) analysed the reading and spelling achievement growth for children from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Their analysis showed this same type of pattern for preschool children with speech and language disorder. That is, they demonstrated delayed early literacy abilities compared to their peers, but showed similar growth trajectories in reading achievement over time. McLeod et al. (Citation2019) concluded that continued effort and research is necessary to better understand how to narrow the literacy gap between children affected by speech and language disorder and their peers. Ensuring young children with communication challenges show the type of accelerated early reading growth that can lead to sustained comprehensive literacy skills will require significant collective effort across professions and across communities. Speech pathologists have an important role in advocating and supporting such efforts to improve literacy outcomes for children with communication challenges.

Advocating for early literacy approaches based on the science of reading

Robust research evidence over many decades has consistently demonstrated the essential cognitive skills that support early reading and writing acquisition (e.g. Hoover & Tunmer, Citation2018). Children’s phonological awareness and their knowledge of how phonemes are represented by graphemes are essential to word recognition and spelling across alphabetic languages (Gillon, Citation2018). Children’s growing oral language competencies in oral narrative skills, vocabulary, and syntactic and morphological awareness all support their literacy achievement (e.g. Metsala et al., Citation2021; Nation & Snowling, Citation2004; Oakhill & Cain, Citation2012; Snowling & Hulme, Citation2021; Westerveld et al., Citation2008). Many well designed interventions to develop these cognitive skills in children at risk for reading problems in small group or individual sessions under experimental research conditions have proven effective in advancing both reading and spelling (e.g. Gersten et al., Citation2020; Gillon, Citation2018). However, evidence of accelerated gains in these children’s reading skills through general class teaching is less common. There is a critical need for large scale implementation of early literacy instruction that is based on the science of reading (Fien et al., Citation2021). Class teachers need to be well supported to implement literacy teaching instruction that has proven effective in advancing children’s foundational literacy skills. This is particularly the case for those children who have too frequently struggled with reading within mainstream education. Through developing strong partnerships with class teachers, speech pathologists are well positioned to support teachers in this endeavour (Snow, Citation2021). However, systems level changes may be required to ensure this is a core part of speech pathologists’ role and that they have the necessary background literacy practice knowledge to build the type of meaningful relationships with teachers that can lead to sustained change in literacy teaching practices (Serry & Levickis, Citation2021).

Comprehensive approaches to literacy instruction based on the science of reading may be referred to as multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), or response to intervention approaches. These types of approaches are specifically designed to facilitate literacy success for all learners, including those who are at greater risk for reading difficulties (e.g. Arias-Gundín & Llamazares, Citation2021; Leonard et al., Citation2019). They typically involve three tiers of evidence-based teaching support: Tier 1 involves quality teaching for all children, usually at the larger group or class level. Tier 2 consists of supplementary small group teaching focused on providing more intensive targeted support. Tier 3 is typically individualised support to meet a child’s specific literacy learning needs. Several issues, however, in the implementation of these approaches in real world settings require investigation (Fien et al., Citation2021; Gonzalez et al., Citation2022). Many speech pathologists are already actively involved in supporting these approaches. For example, in a recent American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) national survey of school based speech pathologists (ASHA, Citation2022), 55% of 2961 respondents indicated they were involved in supporting MTSS activities. Establishing these types of comprehensive approaches to early literacy instruction in ways that are culturally responsive (D'Aietti et al., Citation2020; Gillispie, Citation2021; Gonzalez et al., Citation2022; Hyter, Citation2022; Kourea et al., Citation2018; Macfarlane, Citation2004) and through authentic partnerships with communities (e.g. Burridge et al., Citation2012) is now critically important.

Braiding together differing knowledge streams

In addition to advancing the critical cognitive skills necessary for reading acquisition, recent research has highlighted the importance of ecological, psychological, cultural, and health factors that also influence children’s literacy achievement. These other influencing factors may be particularly important in supporting literacy achievement within diverse communities. For example, in a recent report, Alansari and colleagues (Citation2022) described the facilitators of success for students in New Zealand schools who identify as Māori or from the Pacific Islands. Their research highlighted ecological and psychological influences on students’ achievement. They found that Māori and Pacific learners are flourishing and thriving when they have: strong and positive motivational beliefs about learning; learning experiences that are culturally embracing, aspirational, and future oriented; strong and positive networks of support and role models, both in and out of school; strong home-school partnerships supporting their learning; a collective vision for student success in their communities; and school-wide conditions and teaching practices that are strength-based, ambitious, and contextually unique to their needs as Māori and Pacific students.

The COVID-19 pandemic also highlighted the influence of ecological and psychological factors to children’s learning outcomes. Children’s home learning environments, access to quality digital devices and internet connections, levels of parental engagement in supporting children’s learning, and parental expectations around children learning from home all influenced children’s achievement during the pandemic (e.g. Ribeiro et al., Citation2021). Gillon and Macfarlane (Citation2017) discussed a Braided Rivers approach (He Awa Whiria) to conceptualise the differing streams of knowledge that influence children’s literacy achievement. In this framework the importance of considering both Indigenous knowledges and the scientific reading literature (inclusive of differing research methodologies and diverse populations) is emphasised. Broadening our understanding of what helps facilitate learning success in diverse communities is important to successful engagement within these communities. In turn, successful engagement where researchers and literacy specialists are trusted and known is more likely to support larger scale implementation to either enhance or shift current literacy teaching practices.

Development of the Better Start Literacy Approach

The Better Start Literacy Approach (BSLA; Gillon et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Gillon, McNeill, Scott, Arrow et al., Citation2023) is one example of a MTSS approach for early literacy instruction. It is set within a strengths-based framework that is aligned with the New Zealand Ministry of Education’s response to intervention. The teaching content reflects the simple view of reading theoretical framework (for recent discussions of this framework see Hoover & Tunmer, Citation2018). It involves structured and explicit teaching strategies to develop the critical cognitive skills necessary for successful reading comprehension and writing development. Importantly, BSLA also includes consideration of the ecological, psychological, and cultural influences on children’s literacy learning. The development of BSLA involved several aspects including the following.

Community engagement

BSLA emerged from an extensive engagement strategy with communities across New Zealand as part of the Better Start National Science Challenge (Maessen et al., Citation2023). This challenge is a 10 year program of research (2015–2024) focused on key aspects to enhance children’s wellbeing. Following several consultation meetings across health and education communities, the importance of children’s successful learning and early literacy emerged as one of three major themes for research (children’s mental wellbeing and healthy weight emerged as two other major research themes). In particular, leaders within the Canterbury community called for research informed ways to accelerate children’s early literacy achievement. Due to the devasting and long-term impacts of the Canterbury earthquakes in 2011, children were entering school in some communities with low levels of oral language, and greater behavioural and emotional challenges. Many children born post-earthquakes had their entire 5 years of early learning prior to school entry significantly disrupted. Their families may have been displaced from their home and community, and put under significant stress due to the impact of the earthquake and continuous aftershocks. In one community, we found that 61% of 5-year-olds born in the year or following year of the earthquakes showed delayed oral language in areas critical for early literacy success (Gillon et al., Citation2019). This finding was consistent with other studies highlighting the impact of disasters on young children’s learning (Gomez & Yoshikawa, Citation2017).

Co-construction

Through a co-constructed and iterative process, we developed BSLA to not only be effective in enhancing children’s literacy skills, but also to be efficient. We sought out evidence from controlled research trials that indicated strategies that would support accelerated early literacy growth. This included evidence from earlier phonological awareness trials for children with speech and language disorder undertaken within the New Zealand and Australian education contexts (e.g. Gillon & Dodd, Citation1997; Gillon, Citation2000). We also carefully considered models of professional learning and development (PLD) for class teachers to avoid limited benefits being reported for teachers from PLD when implemented in real world settings (Piasta et al., Citation2017). We also sought to ensure the model could be sustainable for teachers and could be implemented in both rural and city schools.

We collaborated with junior school class teachers in design implementation. We wanted to ensure the approach could feasibly be implemented during their literacy curriculum teaching, but still adhere to sufficient intensity of instruction and use of explicit teaching strategies. This was an iterative process beginning with controlled pilot trials in seven schools in Christchurch. Following the successful outcomes of these trials and discussions with community leaders, we gained funding from the Ministry of Education for further controlled trials across 14 schools in both Auckland and Christchurch regions. Data demonstrating the success from these trials (Gillon et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Gillon, McNeill, Scott, Arrow et al., Citation2023) together with teacher, parent, school leader, and community voices strongly supporting the approach, we secured major funding to lead the national implementation of BSLA (2020–2023) through a government competitive procurement process.

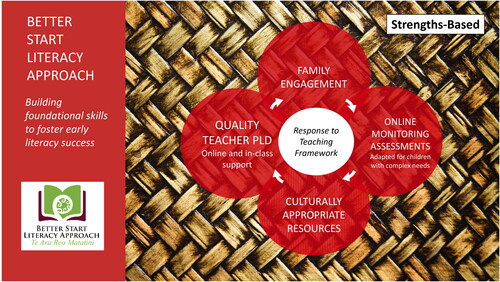

summarises key aspects of the Better Start Literacy Approach.

Strengths-based

BSLA is a strengths-based and inclusive approach to early literacy instruction. The metaphor of being supported by a woven mat (whāriki) seen in symbolises the interconnected nature of the influences that support children’s literacy development. The woven mat, or whāriki, and rāranga (weaving) is a taonga (treasure) for Māori with symbolic and spiritual meaning. It aligns with a Māori worldview of the importance of interdependent relationships, which places the child within the context of their family and community. Te Whāriki is the name of the early childhood curriculum in New Zealand (Ministry of Education, Citation2017) so the figure also depicts the importance of learning during the early years to lay strong foundations for formal literacy learning following school entry. Our strengths-based foundation for the approach focuses attention on what children can achieve and then on identifying next steps for learning. It is consistent with an international movement away from deficit-based and problem focused discourse to focusing on factors that influence successful outcomes (for a detailed discussion of the strengths-based framework, see Gillon, McNeill, Scott, Arrow et al., Citation2023).

Whānau (family) and community engagement

The BSLA includes a clear strategy to engage children’s whānau (parents and extended family) in their children’s literacy learning, valuing parents’ efforts and time in supporting their child’s learning. Slides and videos are prepared for teachers to use or adapt and share within their community and at whānau workshops. This supports families in learning about BSLA, as well as providing practical ideas on how to support their children with reading at home.

Online assessments

BSLA incorporates purposely developed online monitoring assessments in the area of phoneme awareness, phonic knowledge, nonword reading, and spelling, tasks (Gillon, McNeill, Scott, Arrow et al., Citation2023) and an oral narrative story retell task with comprehension questions (Gillon, McNeill, Scott, Gath et al., Citation2023; Scott et al., Citation2022). These assessments have been specifically designed for class teachers to use in positive ways and to guide their teaching practice. The online tasks (iPad or computer accessed) are engaging for young children, ensure consistency of task presentation to the children, and incorporate a number of features to reduce teacher workload. Features include automated transcription and analysis of children’s story retell, automatic scoring of phoneme awareness and phonic knowledge tasks, and automatically generated reporting features for teachers to share electronically with other professionals, such as speech pathologists, and with parents. The assessment tasks can be adapted for children with complex communication needs (Clendon et al., Citation2022) to ensure these critical foundational cognitive skills for literacy are being monitored in all children. Periodic monitoring assessments (e.g. after 10, 20, or 30 weeks of BSLA teaching) are implemented during the child’s first 2 years at school.

Culturally appropriate teaching resources

Daily lesson plans (30 min) are provided to the teachers. These have been designed for implementation from school entry through to the end of children’s second year at school. Culturally relevant games are incorporated into the lesson plans as well as Māori phrases of encouragement and motivation. Key elements of the teaching content include structured and explicit teaching strategies to support children’s phoneme awareness, phonic and orthographic knowledge, morphological awareness, and the transference of this awareness to the reading and writing process. Vocabulary, oral narrative, and listening comprehension skills are explicitly taught through the context of quality children’s storybooks. Common Māori vocabulary (i.e. vocabulary children are likely to have been exposed to during early childhood education or in their communities) is incorporated into the stories and teaching activities. In addition, many of the recommended quality children’s storybooks have a New Zealand cultural focus. BSLA also includes differentiated small group reading instruction using newly developed decodable texts that reflect the New Zealand cultural context. Lead researchers of BSLA developed these texts for the Ministry of Education; these are aligned with BSLA lesson plans and the BSLA phonics scope and sequence (Arrow et al., Citation2021).

Quality teacher professional learning and development

BSLA has a strong framework for teachers’ and literacy specialists’ PLD related to research informed effective reading instructional practices. The PLD includes online learning via newly developed postgraduate micro-credential qualifications in BSLA. Speech pathologists and literacy specialists enrol in the Facilitator BSLA micro-credential, which focuses on supporting class teachers to implement BSLA. As part of this qualification, these facilitators engage in coaching teachers within the teachers’ class context. Teachers undertake the Teacher BSLA micro-credential, which focuses on implementing BSLA within the class context. This model ensures professionals involved in implementing or supporting BSLA have access to the same theoretical and teaching content, teaching resources, and assessment tasks. In addition, both the BSLA facilitators and teachers meet with the BSLA leaders through weekly online Zoom meetings.

Response to teaching framework

The approach is set within a multi-tiered system of support framework that we have referred to as a response to teaching framework. This includes the following tiers.

Tier 1

Following baseline assessments at school entry, children are engaged in BSLA. Structured lesson plans are provided for the first 2 years of children’s literacy instruction. Following the first 10 weeks of BSLA teaching (or approximately 40 BSLA 30-min Tier 1 lesson plans), teachers monitor children’s progress and select children for Tier 2 supplementary support.

Tier 2

Children identified for Tier 2 receive an additional 30 min daily small group lesson for a further 10 weeks (or until they have received approximately 40 Tier 2 BSLA structured lessons). Their progress is then reassessed and decisions for further support made.

Tier 3

This involves individual planning based on a learner’s need and response to Tier 1 and Tier 2 BSLA teaching activities. Alternatively, children who enter school with Tier 3 level of support already identified engage in BSLA teaching activities that have been adapted for their specific learning needs (Clendon et al., Citation2022).

Children’s progress following 10 weeks of BSLA teaching

Data from the controlled trials of BSLA, including effectiveness for children who enter school with lower levels of oral language, are published through open access journals (Gillon et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Gillon, McNeill, Scott, Arrow et al., Citation2023). Ethical approval has been granted for anonymised data collected from the online assessment website to be used for ongoing research purposes. This section provides examples of some current data that demonstrate the significant shifts in children’s achievement in response to 10 weeks of BSLA class teaching.

Phoneme awareness and phonic knowledge

summarise data pre- and post-10 weeks of Tier 1 BSLA teaching for the same cohort of children (N = 6762), who were all aged between 5 years 0 months and 5 years 3 months at school entry (mean age = 61.6 months; SD = 1.05). Of these children, 50.1% were female. Main ethnic groups comprised 51% NZ European, 23% Māori, 7% Pacific, and 12% Asian. Children were in schools from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds with a bias towards more children from schools in high deprivation areas. (A focus on children with greater learning needs was part of the initial phase of the national BSLA implementation plan).

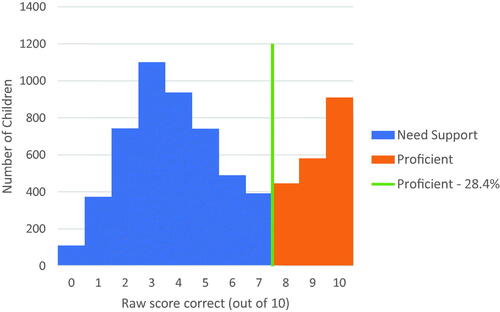

Figure 2. Initial phoneme identity baseline assessment (n = 6819). All children were aged between 5y0m and 5y3m at time of assessment, with 28.4% of children reaching proficiency on this task.

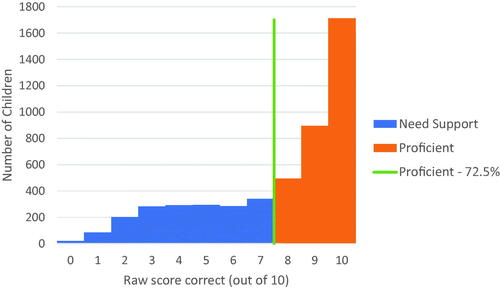

Figure 3. Initial phoneme identity 10 week assessment (n = 4905) for the school entry cohort. Following 10 weeks of Tier 1 BSLA teaching, 72.5% of this cohort reached proficiency.

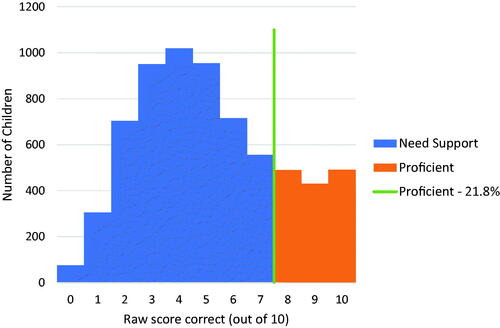

Figure 4. Phoneme blending baseline assessment (n = 6772). All children were aged between 5y0m to 5y3m, with 21.8% being proficient on this task at school entry.

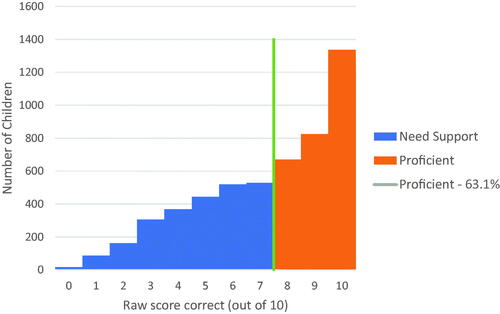

Figure 5. Phoneme blending 10 week assessment (n = 4905) for the school entry cohort who were aged 5y0m–5y3m at baseline assessment. Following 10 weeks of Tier 1 BSLA teaching, 63.1% of this cohort reached proficiency.

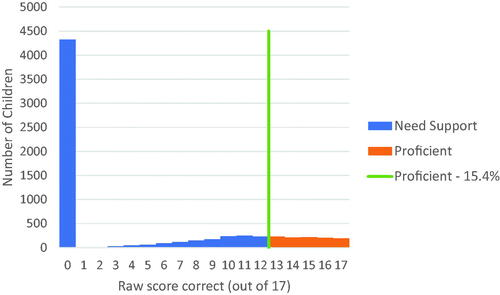

Figure 6. Phoneme grapheme knowledge set 2 (n = 6749) baseline assessment. Set 2 contains more complex phoneme grapheme matches (e.g. ch, sh, th) and is implemented if children reach proficiency on set 1. All children were aged between 5y0m and 5y3m, with 15.4% of the cohort being proficient on this task at school entry.

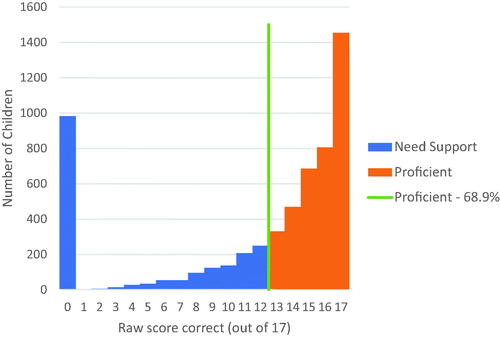

Figure 7. Phoneme grapheme knowledge set 2 10 week assessment (n = 5723) for the children who were aged between 5y0m and 5y3m. Following 10 weeks of BSLA Tier 1 teaching, 68.9% were proficient on this task.

Gillon, McNeill, Scott, Arrow et al. (Citation2023) provide details of the online task assessment tasks. and relate to children’s performance on the BSLA online phoneme identity task. This task requires children to select a target word from a choice of three pictures, e.g. “Which word starts with d?” (moon, duck, whale). A score of 8, 9, or 10 correct is significantly above chance level and we identified this as the proficiency level for the task. shows 28% of children are proficient at this task at school entry and wide variability in performance is evident. suggests that this wide variability can be dramatically reduced following just 10 weeks of teachers implementing BSLA teaching. shows 72.5% of the children were proficient at the 10 week assessment point.

and relate to children’s performance on the phoneme blending task. Children heard a word segmented by phonemes and were then required to point to one of three pictures to indicate the word they heard. For example, “Click on the picture you think I am saying: /keik/” (cake, cape, ring). A score of 8, 9, or 10 correct is significantly above chance level and we identified this as the proficiency level for this task. shows that at school entry 21.8% of children are proficient on this task. After 10 weeks of BSLA Tier 1 teaching this improves to 63.1%.

and illustrate the children’s achievement on the phoneme grapheme knowledge task (set 2). Children were asked to select the grapheme (from a choice of six) that represented the phoneme they heard. Set 2 contains phoneme grapheme matches for the following letters: ch, b, i, f, r, g, e, sh, k, u, j, w, o, a, v, th, h. This task is only administered if children are proficient in set 1, which contains less complex grapheme phoneme matches (e.g. m, p, t, d). Not surprisingly, only a few children reached proficiency (80% or more correct) on this task (15.4% of children). However, after 10 weeks of BSLA teaching 68.9% of children had reached proficiency. These data suggest a very rapid rate of growth in children’s knowledge of the relationship between phonemes and graphemes.

These data also highlight the importance of moving beyond school entry screening assessments, which historically have emphasised deficit perspectives of subgroups who show poor performance at school entry. Rather, by focusing on assessment data 10 weeks after research informed early literacy instruction, attention is turned to celebrating the growth children make in response to teaching. In addition, children who would benefit from increased teaching intensity can be identified early and provided with Tier 2 teaching support. Gillon et al. (Citation2020) showed children entering school with lower oral language frequently do need Tier 2 support, but when this support is based on the science of reading and is of sufficient intensity these children can show accelerated progress and approach levels similar to their peers towards the end of their first year at school. Importantly, the research showed that starting early with evidence-based class literacy instruction matters. Regardless of whether children had typical language profiles, speech sound disorder, or both speech and language disorder all groups of learners who received BSLA teaching first showed stronger reading and spelling performance at the end of their first school year compared to children with similar profiles who commenced BSLA second (about 12 weeks later; Gillon et al., Citation2019).

Social return on investment

The data from the controlled trials of BSLA and data currently being collected through the national implementation are very encouraging. Independent economic analysis of the Better Start Literacy Approach (Impact Lab GoodMeasure Report, Citation2021) highlights the potential long-term social value from ensuring children have strong foundational literacy skills. The report identified that measurable benefits as a proportion of BSLA costs is 3820% or, for every dollar invested in the BSLA, there was a $38.00 social value return on investment. This is based on the expected spiralling positive education, health, and economic benefits associated with early literacy success and the reduction in adverse social behaviours associated with persistent reading problems.

Summary

Early literacy success is key to reducing current education inequities. Systems level change within education may be necessary to ensure large scale implementation of early literacy instructional approaches that are based on the science of reading and are implemented in culturally responsive and strengths-based ways. Such approaches need to be co-constructed with communities and provide the necessary supports to teachers, literacy specialists, and speech pathologists to ensure fidelity and sustainability of the approach within local teaching contexts and communities. The Better Start Literacy Approach is one example of such an approach currently being implemented nationally in New Zealand. Collectively, data from controlled research trials and ongoing nationally collected data from in-school implementation suggest these types of approaches can significantly enhance children’s early literacy achievement. Such approaches are helpful for all children, but may be particularly important for children who enter school with lower levels of oral language ability. Essential to such outcomes is strong involvement and support from community, and well-funded government support.

Through moving beyond our professional borders and collaborating in culturally responsive and strengths-based ways with educators, other professionals, community leaders and government leaders, the profession of speech pathology has much to offer to the realisation of a literate world for all peoples.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my co-leader in the development of the Better Start Literacy Approach, Professor Brigid McNeill, School of Teacher Education at the University of Canterbury. I would also like to acknowledge our BSLA team leaders and colleagues who have contributed knowledge and expertise to the development of BSLA: Professor Angus Hikairo Macfarlane, Tufulasi Taleni, Dr Amy Scott, Associate Professor Sally Clendon, Associate Professor Marleen Westerveld, Associate Professor Alison Arrow, Dr Lisa Furlong, Dr Andy Vosslamber, Dr Angela Swan, Jen Smith, Rachel Maitland, and Dr Megan Gath. I would also like to acknowledge the support of our BSLA Advisory Group: Distinguished Professor William Tunmer, Professor James Chapman, Distinguished Professor Laura Justice, Professor Ilsa Schwarz, and Lynne Harata Te Aika. I also acknowledge the work of our BSLA team of faciliatator mentors (Dr Jo Walker, Nicole Plummer, Catherine Fairhall, and Amy Fleming), BSLA school facilitators, class teachers, school leaders, research assistants, project mangager, and data analyst.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alansari, M., Webber, M., Overbye, S., Tuifagalele, R., & Edge, K. (2022). Conceptualising Māori and Pasifika Aspirations and Striving for Success (COMPASS). New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

- ASHA: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2022). 2022 Schools survey report: SLP caseload and workload characteristics. https://www.asha.org/Research/memberdata/Schools-Survey/

- Arias-Gundín, O., & Llamazares, A. G. (2021). Efficacy of the RTI model in the treatment of reading learning disabilities. Education Sciences, 11(5), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050209

- Arrow, A., Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A. (2021). Ready to read phonics plus project. End of year report November 2021. University of Canterbury, Child Well-being Research Institute. Accessible online Early Literacy Initiative Ready to Read Phonics plus Project: https://www.betterstartapproach.com/our-research

- Burridge, N., Whalan, F., & Vaughan, K. (Eds.). (2012). Indigenous education: A learning journey for teachers, schools and communities. In Indigenous education (Vol. 86). Springer Science & Business Media.

- Catts, H. W., Bridges, M. S., Little, T. D., & Tomblin, J. B. (2008). Reading achievement growth in children with language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(6), 1569–1579. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0259)

- Clendon, S., Scott, A., Gillon, G., & McNeill, B. (2022). Assessment for learning: Adapting phoneme awareness assessment for children with complex communication needs [Paper Presentation]. American Speech-Language-Hearing-Association Convention New Orleans, USA. Nov 17–19, 2022

- Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 934–945. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.934

- D’Agostino, J. V., & Rodgers, E. (2017). Literacy achievement trends at entry to first grade. Educational Researcher, 46(2), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17697274

- D'Aietti, K., Lewthwaite, B., & Chigeza, P. (2020). Negotiating the pedagogical requirements of both explicit instruction and culturally responsive pedagogy in Far North Queensland: Teaching explicitly, responding responsively. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 50(2), 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2020.5

- Erickson, K. A. (2017). Comprehensive literacy instruction, interprofessional collaborative practice, and students with severe disabilities. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26(2), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJSLP-15-0067

- Fien, H., Chard, D. J., & Baker, S. K. (2021). Can the evidence revolution and multi-tiered systems of support improve education equity and reading achievement? Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S105–S118. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.391

- Gersten, R., Haymond, K., Newman-Gonchar, R., Dimino, J., & Jayanthi, M. (2020). Meta-analysis of the impact of reading interventions for students in the primary grades. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 13(2), 401–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2019.1689591

- Gillispie, M. (2021). Culturally responsive language and literacy instruction with native American children. Topics in Language Disorders, 41(2), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0000000000000249

- Gillon, G. T. (2000). The efficacy of phonological awareness intervention for children with spoken language impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 31(2), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461.3102.126

- Gillon, G. T. (2018). Phonological awareness: From research to practice (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Gillon, G., & Dodd, B. (1997). Enhancing the phonological processing skills of children with specific reading disability. European Journal of Disorders of Communication, 32(2 Spec No), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.1997.tb01625.x

- Gillon, G., & Macfarlane, A. H. (2017). A culturally responsive framework for enhancing phonological awareness development in children with speech and language impairment. Speech, Language and Hearing, 20(3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2016.1265738

- Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Denston, A., Scott, A., & Macfarlane, A. (2020). Evidence-based class literacy instruction for children with speech and language difficulties. Topics in Language Disorders, 40(4), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0000000000000233

- Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A., Arrow, A., Gath, M., & Macfarlane, A. (2023). A Better Start Literacy Approach: Effectiveness of Tier 1 and Tier 2 support within a response to teaching framework. Reading and Writing, 36(3), 565–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10303-4

- Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A., Denston, A., Wilson, L., Carson, K., & Macfarlane, A. H. (2019). A better start to literacy learning: Findings from a teacher-implemented intervention in children’s first year at school. Reading and Writing, 32(8), 1989–2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9933-7

- Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A., Gath, M., & Westerveld, M. (2023). Retelling stories: The validity of an online oral narrative task. Child Language Teaching and Therapy Early Therapy, 39 (2), 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/02656590231155861

- Goldhaber, D., Kane, T. J., McEachin, A., Morton, E., Patterson, T., & Staiger, D. O. (2022). The consequences of remote and hybrid instruction during the pandemic [No. w30010]. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w30010/w30010.pdf

- Gomez, C. J., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). Earthquake effects: Estimating the relationship between exposure to the 2010 Chilean earthquake and preschool children’s early cognitive and executive function skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38, 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.08.004

- Gonzalez, J. E., Durán, L., Linan-Thompson, S., & Jimerson, S. R. (2022). Unlocking the promise of multitiered systems of support (MTSS) for linguistically diverse students: advancing science, practice, and equity. School Psychology Review, 51(4), 387–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2105612

- Hanushek, E. A., Light, J. D., Peterson, P. E., Talpey, L. M., & Woessmann, L. (2022). Long-run trends in the U.S. SES–Achievement gap. Education Finance and Policy, 17(4), 608–640. https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00383

- Hayiou‐Thomas, M. E., Carroll, J. M., Leavett, R., Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2017). When does speech sound disorder matter for literacy? The role of disordered speech errors, co‐occurring language impairment and family risk of dyslexia. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 58(2), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12648

- Hoover, W. A., & Tunmer, W. E. (2018). The simple view of reading: Three assessments of its adequacy. Remedial and Special Education, 39(5), 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518773154

- Holm, A., Farrier, F., & Dodd, B. (2008). Phonological awareness, reading accuracy and spelling ability of children with inconsistent phonological disorder. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 43(3), 300–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820701445032

- Hyter, Y. D. (2022). Engaging in culturally responsive and globally sustainable practices. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(3), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2070280

- Impact Lab GoodMeasure Report. (2021). Better start literacy approach national implementation Impack lab report. https://www.betterstartapproach.com/our-research

- Kourea, L., Gibson, L., & Werunga, R. (2018). Culturally responsive reading instruction for students with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 53(3), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451217702112

- Leonard, K. M., Coyne, M. D., Oldham, A. C., Burns, D., & Gillis, M. B. (2019). Implementing MTSS in beginning reading: Tools and systems to support schools and teachers. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 34(2), 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/ldrp.12192

- Macfarlane, A. (2004). Kia hiwa rā! Listen to culture: Māori students’ plea to educators. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

- Maessen, S. E., Taylor, B. J., Gillon, G., Moewaka Barnes, H., Firestone, R., Taylor, R. W., Milne, B., Hetrick, S., Cargo, T., McNeil, B., & Cutfield, W. (2023). A better start national science challenge: supporting the future wellbeing of our tamariki E tipu, e rea, mō ngā rā o tō ao: grow tender shoot for the days destined for you. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2023.2173257

- McLeod, S., Harrison, L. J., & Wang, C. (2019). A longitudinal population study of literacy and numeracy outcomes for children identified with speech, language, and communication needs in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.07.004

- McNeill, B., Gillon, G., & Dodd, B. (2009). Phonological awareness and early reading development in childhood apraxia of speech (CAS). International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 44(2), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820801997353

- Metsala, J. L., Sparks, E., David, M., Conrad, N., & Deacon, S. H. (2021). What is the best way to characterise the contributions of oral language to reading comprehension: Listening comprehension or individual oral language skills? Journal of Research in Reading, 44(3), 675–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12362

- Ministry of Education. (2017). https://tewhariki.tki.org.nz/en/key-documents/te-whariki-2017/the-whariki/

- Nation, K., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Beyond phonological skills: Broader language skills contribute to the development of reading. Journal of Research in Reading, 27(4), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2004.00238.x

- Ngata, W. (2017). Kanohi ki te kanohi: Face-to-face in digital space. He Whare Hangarau Māori: Language, Culture & Technology, 178–183. https://www.waikato.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/394920/chapter23.pdf

- Oakhill, J. V., & Cain, K. (2012). The precursors of reading ability in young readers: Evidence from a four-year longitudinal study. Scientific Studies of Reading, 16(2), 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2010.529219

- Piasta, S. B., Justice, L. M., O'Connell, A. A., Mauck, S. A., Weber-Mayrer, M., Schachter, R. E., Farley, K. S., & Spear, C. F. (2017). Effectiveness of large-scale, state-sponsored language and literacy professional development on early childhood educator outcomes. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 10(2), 354–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2016.1270378

- Petscher, Y., Cabell, S. Q., Catts, H. W., Compton, D. L., Foorman, B. R., Hart, S. A., Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., Schatschneider, C., Steacy, L. M., Terry, N. P., & Wagner, R. K. (2020). How the science of reading informs 21st-century education. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(Suppl 1), S267–S282. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.352

- Relyea, J. E., Rich, P., Kim, J. S., & Gilbert, J. B. (2023). The COVID-19 impact on reading achievement growth of Grade 3–5 students in a U.S. urban school district: Variation across student characteristics and instructional modalities. Reading and Writing, 36(2), 317–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10387-y

- Ribeiro, L. M., Cunha, R. S., Andrade E Silva, M. C., Carvalho, M., & Vital, M. L. (2021). Parental involvement during pandemic times: Challenges and opportunities. Education Sciences, 11(6), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060302

- Ritchie, S. J., & Bates, T. C. (2013). Enduring links from childhood mathematics and reading achievement to adult socioeconomic status. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1301–1308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612466268

- Saha, S. (2006). Improving literacy as a means to reducing health disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(8), 893–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00546.x

- Schuele, C. M., Spencer, E. J., Barako-Arndt, K., & Guillot, K. M. (2007). Literacy and children with specific language impairment. Seminars in Speech and Language, 28(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-967928

- Scott, A., Gillon, G., McNeill, B., & Kopach, A. (2022). The evolution of an innovative online task to monitor children’s oral narrative development. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 903124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903124

- Serry, T., & Levickis, P. (2021). Are Australian speech-language therapists working in the literacy domain with children and adolescents? If not, why not? Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 37(3), 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659020967711

- Sharp, K. (2012). Breaking down the barriers: Using critical literacy to improve educational outcomes for students in 21st-century Australian Classrooms. Literacy Learning : The Middle Years, 20(1), 9–15.

- Snow, P. C. (2016). Elizabeth usher memorial lecture: Language is literacy is language–Positioning speech-language pathology in education policy, practice, paradigms and polemics. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18(3), 216–228. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2015.1112837

- Snow, P. C. (2021). SOLAR: The science of language and reading. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 37(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659020947817

- Snowling, M. J., & Hulme, C. (2021). Annual research review: Reading disorders revisited–the critical importance of oral language. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 62(5), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13324

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2011). Literacy position statement. Speech Pathology Australia. Position Statements (speechpathologyaustralia.org.au).

- Tomaszewski, W., Zajac, T., Rudling, E., Te Riele, K., McDaid, L., & Western, M. (2023). Uneven impacts of COVID-19 on the attendance rates of secondary school students from different socioeconomic backgrounds in Australia: A quasi-experimental analysis of administrative data. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.219

- Tunmer, W. E., Chapman, J. W., & Prochnow, J. E. (2006). Literate cultural capital at school entry predicts later reading achievement: A seven year longitudinal study. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 41(2), 183–204.

- UNICEF. (2021). COVID-19: Schools for more than 168 million children globally have been completely closed for almost a full year, says UNICEF. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/schools-more-168-million-children-globally-have-been-completely-closed

- UNESCO. (2022). Literacy: Promoting the power of literacy for all. UNESCO. https://www.unesco.org/en/literacy

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. (A/RES/70/1). https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf

- Westerveld, M. F., Gillon, G. T., & Moran, C. (2008). A longitudinal investigation of oral narrative skills in children with mixed reading disability. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 10(3), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14417040701422390

- World Health Organization. (2020). Statement from the ‘civil society’ track of the 3rd Global Infodemic Management Conference. WHO. https://www.who.int/news/item/10-12-2020-statement-from-the-civil-society-track-of-the-3rd-global-infodemic-management-conference

- World Vision. (2023). Towards literacy for everybody. WORLDVISION. https://www.worldvision.com.au/towards-literacy-for-everybody