Abstract

Purpose

Optimising dysphagia service delivery is crucial to minimise personal and service impacts associated with dysphagia. However, limited data exist on how to achieve this in Singapore. This study aimed to develop prioritised enhancements that the speech-language pathology workforce perceived as needed to improve dysphagia services in Singapore.

Method

Using a concept mapping approach, 19 speech-language pathologists (SLPs) and 10 managers listed suggestions for dysphagia service optimisation. Within their groups, the collated suggestions were sorted based on similarity, and individually rated on a 5-point scale based on importance and changeability. Using cluster and bivariate analysis, clusters of similar suggestions and prioritised suggestions for service optimisation were identified.

Result

The SLPs and managers proposed 73 and 51 unique suggestions respectively. Six clusters were identified for each group, with similar themes suggesting agreement of service improvements. All clusters were rated as more important than changeable. The managers perceived services as easier to change. The SLPs and managers rated 37% (27/73) and 43% (22/51) of suggestions, respectively, as high priority, with similarities relating to workforce capacity and capability, support and services access, care transitions, and telehealth services.

Conclusion

Prioritised enhancements identified by SLPs and managers provide direction for dysphagia service optimisation in Singapore.

Introduction

Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) is a highly prevalent condition, with meta-analyses reporting rates of 36.5% in hospital settings, 42.5% in rehabilitation facilities, and 50.2% in residential aged care facilities (Rivelsrud et al., Citation2023). As it is widely associated with poor health and service outcomes (E. Jones et al., Citation2018; Paranji et al., Citation2017; Patel et al., Citation2018), optimisation of dysphagia service delivery is critical. In pursuit of understanding what is needed to optimise dysphagia services, studies exploring current practice patterns have found varied dysphagia practices among speech-language pathologists (SLPs) in the USA (Carnaby & Harenberg, Citation2013; Mathers-Schmidt & Kurlinski, Citation2003), Ireland (McCurtin & Healy, Citation2017; Pettigrew & O'Toole, Citation2007), and Australia (Rumbach et al., Citation2018). High degree of practice variability was also reported by international studies exploring SLPs’ practices within homogenous patient population groups and settings, such as the critical care setting across 29 countries (Rowland et al., Citation2023), the stroke population within the UK and Ireland (Archer et al., Citation2013), emergency departments (Lal et al., Citation2020), community-based settings (Howells et al., Citation2019b), and the stroke population within Australia (O. Jones et al., Citation2018). Varied dysphagia practices may imply deviation from clinical guidelines and recommendations (Archer et al., Citation2013), and can result in conflicting management plans and confusion regarding treatment recommendations among patients (Poon et al., Citation2023a). This can in turn impact dysphagia service delivery and affect the quality and safety of dysphagia care.

Similarly, studies of healthcare services within Australia, Ireland, the UK, and the USA have each reported dysphagia service inefficiencies associated with resource and funding constraints (Chen et al., Citation2022; Howells et al., Citation2019a; Lal et al., Citation2023), an insufficient speech-language pathology workforce (Eltringham et al., Citation2022; Howells et al., Citation2019a), and clinician skill mix issues (Archer et al., Citation2013; McCurtin & Healy, Citation2017; Pettigrew & O'Toole, Citation2007; Rumbach et al., Citation2018). For many services, a lack of convenient access to diagnostic tools, such as videofluoroscopy and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), remains a key barrier impacting the quality of diagnostic decisions (Howells et al., Citation2019b; Rangarathnam & Desai, Citation2020; Rumbach et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, although seamless care transition between service providers is integral for care continuation, breakdown during the transfer of dysphagia information is common (Horgan et al., Citation2020; Miles et al., Citation2016) and in certain settings, such as community care, the lack of locally-available healthcare professionals remains an ongoing barrier for care continuity once the patient leaves the hospital setting (Howells et al., Citation2019a).

Although it is widely acknowledged that involvement of healthcare professionals beyond speech-language pathology is integral for ensuring that optimal dysphagia care and supports are provided (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2004; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2012; Yang et al., Citation2023), research has identified a range of service barriers affecting this. For instance, emergency departments within Australia (Lal et al., Citation2023) and stroke units in England and Wales (Eltringham et al., Citation2022) have reported challenges in providing timely dysphagia-screening services due to reduced staffing, high workload demands, poor understanding of screening procedures and protocols among healthcare professionals, and high nursing staff turnover impacting staff education and training. These factors can lead to delayed and inappropriate screening services, which deviate from the recommended care standards of professional associations (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2019; Stroke Foundation, Citation2022), and can lead to poorer clinical and service outcomes (Sherman et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, late initiation of dysphagia referrals has also resulted in delayed dysphagia care (Eltringham et al., Citation2022). Therefore, to optimise dysphagia services, it is necessary to examine and address potential contributing barriers both within and outside of speech-language pathology departments.

Within Singapore, there has been limited research examining adult dysphagia service delivery until recently. A recent study surveyed 12 managers and 68 SLPs working in acute and subacute settings, which uncovered several service issues common to, and unique from, the international literature (Poon et al., Citation2023a). In terms of similarities, SLPs in Singapore reported challenges in providing dysphagia assessments and intervention due to funding and resource availability, high caseload demands, and an insufficient workforce (Poon et al., Citation2023a). These service limitations were also described by clinicians in India (Rangarathnam & Desai, Citation2020), Australia (Howells et al., Citation2019a; Rumbach et al., Citation2018), England and Wales (Eltringham et al., Citation2022), and the USA (Chen et al., Citation2022). Additionally, the clinicians in Singapore reported the lack of dysphagia knowledge and support among the healthcare team when collaborating to provide dysphagia care (Poon et al., Citation2023a), which is congruent with research based in Australia (Lal et al., Citation2023), New Zealand (Miles et al., Citation2016), and England and Wales (Eltringham et al., Citation2022).

Conversely, regarding service issues unique to Singapore, recent research has reported a lack of national documents to guide dysphagia service provision (Poon et al., Citation2023a). This contrasts greatly to countries with mature speech-language pathology professions, such as Australia, the USA, and the UK, whose professional bodies (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2023; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2023; Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, Citation2023) have developed national clinical guidelines. Other service challenges unique to Singapore include language barriers when communicating with a linguistically-diverse group of foreign, paid, domestic caregivers; fragmented care transition across services due to the healthcare financing framework; and a complex referral process for subsidised patients (Lim et al., Citation2018; Poon et al., Citation2023a). Collectively, these findings suggest that dysphagia services in Singapore have both similar and unique service features and needs to other countries. Thus, solutions that are relevant in other countries may not be entirely appropriate to the Singapore community, and this needs to be further explored.

Moreover, recent studies examining dysphagia practice patterns and service delivery have focused on describing current service challenges (Eltringham et al., Citation2022; Howells et al., Citation2019a; Lal et al., Citation2023; Poon et al., Citation2023a), but have fallen short of proposing potential solutions or exploring how services could be changed to optimise dysphagia care. Considering the complex nature of the service issues identified in research to date, finding solutions will require consultation with service providers and consumers to ensure any proposed changes are both needed and relevant (Graham et al., Citation2018). Thus, the current study is a part of a larger body of work that seeks to understand SLPs’, managers’, patients’, and carers’ perspectives of optimal dysphagia care in Singapore, and identify dysphagia service enhancements required to meet their holistic needs. Specifically, the aim of this study was to identify and prioritise improvements that SLPs and managers perceived as important and changeable to enhance dysphagia care delivery within acute and subacute settings in Singapore. This information can be used to develop and implement service enhancements that address the needs of the speech-language pathology workforce.

Method

Concept mapping methodology, as described by Kane and Trochim (Citation2007), was selected for this study to help generate a prioritised list of dysphagia service enhancements. This methodology uses a systematic process to integrate, evaluate, and compare individual data. Furthermore, participants are involved in identifying and prioritising service changes, thus ensuring that the findings are relevant to the local speech-language pathology workforce (Graham et al., Citation2018). Ethical approvals were obtained from the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (Singapore) and The University of Queensland (Australia). All participants provided written informed consent and were offered a token financial payment (SGD $20) for their participation.

Participants

Singapore has 21 public/not-for-profit acute and subacute health facilities (Ministry of Health, Singapore, Citation2023), but not all health facilities provide adult dysphagia services (e.g. children’s hospital). Based on anecdotal reports, only 18 health facilities (eight acute general hospitals, one psychiatric hospital with acute and subacute units, and nine subacute community hospitals) provide adult dysphagia services. To ensure adequate representation across these facilities, emails were sent to the managers of speech-language pathology services and SLPs (via their managers) working in these 18 health services, inviting them to participate in this study. Snowball sampling was also encouraged to increase participation. Maximum variation sampling was used to ensure group heterogeneity.

As a few managers supervised dysphagia services in multiple locations, there were only 14 unique managers available for participation. Of this cohort, 10 managers (acute n = 4, subacute n = 4, mixed acute/subacute settings n = 2) participated in this study, representing 66.7% (12/18) of the healthcare facilities. Most managers were female (female n = 9, male n = 1) and had varied managerial experience ranging from less than 1 year to more than 10 years. No data exists regarding the exact number of SLPs providing dysphagia services in acute and subacute settings in Singapore. A total of 19 SLPs participated in this study (acute n = 8, subacute n = 3, and mixed acute/subacute settings n = 8), representing 33.3% (6/18) of the healthcare facilities. Most SLPs were female (female n = 18, male n = 1) and had between 3–21 years of clinical experience (average 7.4 years).

Concept mapping methodology

Concept mapping consists of six stages: (1) preparation, (2) statement generation, (3) structuring, (4) representation, (5) interpretation, and (6) utilisation (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007). However, only Stages 1–5 are reported in this paper as Stage 6 (utilisation) will occur later as part of a larger body of work being conducted by this research team. In Stage 6, the current data will be combined with the concept mapping findings from a prior study involving patients/carers (Poon et al., Citation2023b) to inform holistic service changes.

Stages 1 and 2: Preparation and statement generation

Stages 1 and 2 were conducted in the same session. Depending on the participants’ preferences, the sessions were conducted with single individuals or in small groups of either SLPs or managers, and via in-person meeting or videoconferencing. All managers attended the session individually via videoconferencing. For the SLPs, only one SLP attended the session individually in-person and the remaining 18 attended the session via videoconferencing (13 individually, one group of two, and one group of three). All sessions were conducted in English and the average session duration for the SLP and manager groups were 51 min (24–74 min) and 56 min (39–92 min), respectively.

Stage 1 began with briefing the participants about the concept mapping process, followed by a semi-structured interview. The purpose of the interview was to prepare the participants for Stage 2 (statement generation) of the concept mapping process, where they provided suggestions for service improvements. Thus, the interview questions were designed to facilitate broad reflections of their experiences of providing dysphagia services and not to elicit in-depth recounts of their experiences. Using this guiding principle, the research team developed an interview guide that incorporated broad questions asking participants to reflect on the types of dysphagia services offered within their settings, enablers and challenges in providing/managing dysphagia services, and experiences when facilitating care transitions across services and on discharge to patients’ homes (Supplementary Material). All interviews were conducted by the lead researcher (FP), a senior SLP with 10 years of experience working in Singapore health services. FP was acquainted with some participants on personal and/or professional levels, but no participant was in her direct reporting line. In Stage 2, immediately after the interviews, participants were asked “what needs to be changed about the current dysphagia services in order to achieve the ‘optimal’ or ‘ideal’ dysphagia service?”, and invited to suggest as many statements as possible in response to this question. These responses were then reviewed by the research team to remove duplicates and non-relevant statements, leaving a list of unique statements relating to service optimisation generated by each participant group.

Stage 3: Structuring

Approximately 5 months after Stage 2, participants completed Stage 3 individually, either in-person or via videoconferencing depending on their preferences. Each individual reviewed the set of unique statements from their cohort (SLPs or managers) and were asked to complete a set of tasks. First, they sorted the statements into groups based on similarity following three guidelines—(a) each statement could only be sorted into one group, (b) groups could comprise of one statement only, and (c) a single group containing all statements was not allowed. After this sorting task, each participant was asked to rate each statement using a 5-point scale regarding its perceived importance (0 = not important at all, 4 = extremely important), and changeability (0 = not changeable at all, 4 = extremely changeable).

Stages 4 and 5: Representation and interpretation

Data from the SLP and manager groups were analysed separately by the research team using R-CMap, a free and open-source software described by Bar and Mentch (Citation2017). First, the sorting data were analysed using multidimensional scaling to produce a two-dimensional point map and a stress value for each group. Hierarchical cluster analysis was then used to determine the number of statement clusters. The number of clusters and cluster themes for each group were determined by the research team through an iterative process of reviewing dendrogram structure arrangements and statements to ensure that each cluster contained conceptually similar statements, and that each cluster had a distinctive concept from other clusters.

Next, the importance and changeability scores for all statements within each cluster were analysed to produce average cluster ratings, that were then depicted in cluster rating maps for each group. These maps display: the (a) extent of similarity between statements, as commonly grouped statements are placed closer on the map; (b) extent of agreement of statements within a cluster, as smaller cluster size indicates greater agreement of statements within a cluster; (c) relationships between clusters, as conceptually similar clusters are situated closer to one another; and (d) relative cluster ratings, as clusters with more layers indicate higher cluster ratings. The relationship between importance and changeability cluster ratings for both groups is also displayed as pattern matching maps. Lastly, the importance and changeability ratings of each of the unique statements within each participant group were computed to generate bivariate go-zone plots.

The cluster themes, top-three rated clusters on the importance and changeability scales, and go-zone statements were compiled and emailed to the participants. Participants were offered the opportunity to clarify or request further information within 2 weeks of receiving the email. As no participant sought clarification or changes, the findings were finalised.

Result

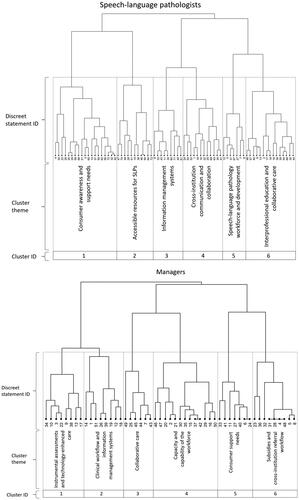

The SLP group generated 73 unique statements, while the manager group produced 51 unique statements for service optimisation in Singapore. The stress values of the two-dimensional point maps for the SLP and manager groups were 0.318 and 0.302, respectively, implying acceptable goodness of fit (Sturrock & Rocha, Citation2000). Hierarchical cluster analysis identified six clusters for each group (), and their cluster themes and characteristics are detailed in .

Table I. Cluster themes, theme descriptions, and example statements for the speech-language pathologist (SLP) and manager groups.

Comparison of statement clusters between both groups () revealed several similar themes, but with some subtle differences. First, both groups had a cluster of statements relating to consumer support needs (SLP: Cluster 1, manager: Cluster 5), such as having educational resources in different languages, however, the SLP group had an additional concept of increasing public awareness regarding dysphagia. Both groups also generated statements relating to accessible resources (SLP: Cluster 2, manager: Cluster 1), though the SLPs’ statements referred more to generic patient supports and resources such as access to interpreters and feeding utensils, whereas the managers focused on overarching service provision such as access to instrumental assessments and technology-enhanced service models. Statement clusters relating to information management (SLP: Cluster 3, manager: Cluster 2) were also found in both groups, but the manager group highlighted the need for systems that enhanced clinical workflow (e.g. triaging systems). Both groups also had statements that related to cross-institution communication and collaboration (SLP: Cluster 4, manager: Cluster 6). Within the manager group (Cluster 6), there was a strong focus on streamlining the patient subsidy system and similar statements were also suggested by the SLPs in Cluster 1, under consumer support needs. In both groups, improvements regarding the capacity and the capability of the workforce were identified (SLP: Cluster 5, manager: Cluster 4), with the SLPs’ statements pertaining to manpower and practice standardisation across speech-language pathology departments, whereas the manager group focused on interprofessional education and capacity development for all relevant professionals providing dysphagia services. Finally, both groups had statement clusters relating to collaborative care (SLP: Cluster 6, manager: Cluster 3), including the importance of having a team of professionals working seamlessly to provide optimal services.

The cluster rating maps confirmed six distinctive cluster concepts for each group, though some clusters were more highly related than others (Supplementary Material, ). For example, in the SLP group, Clusters 1 (consumer awareness and support needs) and 2 (accessible resources for SLPs) were closer together indicating that they were more related, while Clusters 3 (information management systems) and 5 (Speech-language pathology workforce and development workforce and development) were maximally distanced, indicating significantly distinctive concepts.

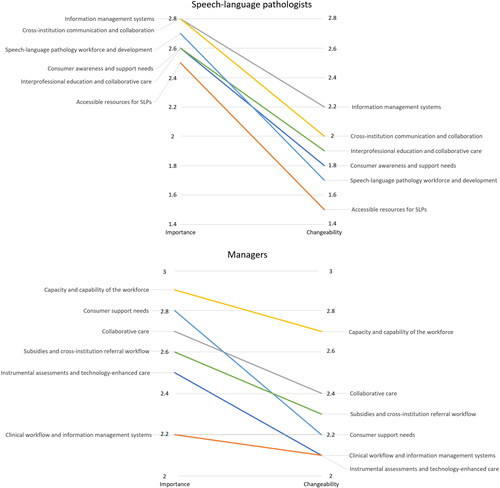

The pattern matching maps for both groups are provided in . As indicated by the negative gradient of the lines linking importance and changeability scores for each cluster, participants perceived all clusters of service enhancement as more important than changeable and the least important clusters were also the most challenging to change. Furthermore, the managers viewed services as easier to change compared to the SLPs. The top three important clusters rated by the SLP group were information management systems, cross-institution communication and collaboration, and speech-language pathology workforce and development, whereas the manager group perceived the top three important clusters as capacity and capability of the workforce, consumer support needs, and collaborative care. Both groups had identified workforce capacity and development as a highly important aspect of service enhancement. Regarding changeability, the top three clusters rated as easiest to change by the SLP group were information management systems, cross-institution communication and collaboration, and interprofessional education and collaborative care, while the manager group perceived the three easiest to change clusters as capacity and capability of the workforce, collaborative care, and subsidies and cross-institution referral workflow. Both groups had identified cross-institution processes and collaborative care as aspects of service enhancement that were highly changeable.

Figure 2. Pattern matching maps comparing importance and changeability of each cluster for the speech-language pathologist (SLP) and manager groups.

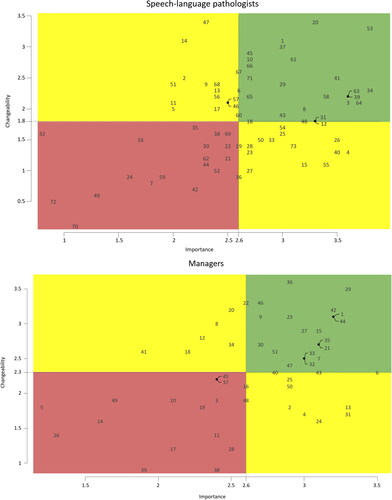

The bivariate go-zone plots of the SLP and manager groups are provided in . Of primary interest for this paper is the group of statements that fell within the upper right quadrant (go-zone) as these statements were rated as both highly important and highly changeable. For the SLP group, 27 statements (37% of all statements) fell within the go-zone and the most highly rated statement on both variables was Statement 53, “everyone should use the same modified consistencies terminologies.” Whereas, for the manager group, 22 statements (43% of all statements) fell within the go-zone and the most highly rated statement on both variables was Statement 29, “there should be more interprofessional education and collaboration opportunities.”

Figure 3. Go-zone plots comparing importance and changeability of each statement for the speech-language pathologist and manager groups.

Note. The numbers represent statement IDs (e.g. number 53 means Statement ID 53).

The 27 go-zone statements identified by the SLP group came from all six clusters (), with the greatest number of statements coming from Cluster 1 (consumer awareness and support needs, n = 7), Cluster 3 (information management systems, n = 7), and Cluster 4 (cross-institution communication and collaboration, n = 6). Similarly, the 22 go-zone statements identified by the manager group came from all six clusters, with the greatest number of statements coming from Cluster 4 (capacity and capability of the workforce, n = 8; ). Comparison of go-zone statements of both groups revealed a number of common suggestions (see statements with asterisks in and ), including ensuring educational resources are accessible for patients and carers, providing available and accessible telehealth services, having access to patients’ previous medical notes, having access to a directory of speech-language pathology services in Singapore, using the same modified consistencies terminology, improving communication between services, simplifying referral processes, hiring more SLPs and assistants to provide services, providing collaborative care management, and improving dysphagia knowledge and skills among the healthcare team.

Table II. Twenty-seven go-zone statements rated as both highly important and highly changeable by the speech-language pathologist (SLP) group.

Table III. Twenty-two go-zone statements rated as both highly important and highly changeable by the manager group.

Discussion

This study consulted SLPs and managers to identify and prioritise service changes to enhance dysphagia care within acute and subacute settings in Singapore. Despite generating statements separately, both groups identified similar issues from all aspects of services, reflecting a shared understanding of issues to address in Singapore. More importantly, both groups generated similar suggestions and rated them as highly important and easy to change to enhance dysphagia services in Singapore. Hence, the combined data from the two groups offers a clear future direction on how to develop and implement services that address the expectations and needs of the local speech-language pathology workforce.

Both SLPs and managers highlighted the need to expand workforce capacity and capability by hiring more SLPs and assistants to provide services, improving dysphagia knowledge and skills among healthcare teams, and providing collaborative management. The need to improve these areas is not unexpected given the growing demand for dysphagia services to meet the annual increase in dysphagia prevalence reported within the literature (Leder & Suiter, Citation2009; Leder et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, it has been suggested that the incidence of dysphagia increases with age (Bhattacharyya, Citation2014; Cohen et al., Citation2020), thus, as the world’s population ages (United Nations Population Division, Citation2019), the demand for dysphagia services across health systems globally is likely to grow exponentially with time. A possible solution to this issue is to utilise allied health assistant delegation models to improve service access and delivery (Schwarz et al., Citation2020; Ward, Citation2019). For example, a study conducted in Australia reported that delegating certain clinical tasks (e.g. screening) to assistants alleviated the SLPs’ workload to manage more clinically complex and/or urgent tasks (Schwarz et al., Citation2020). Realising the potential of such delegation models may have been the reason for prioritising the need to hire more assistants within speech-language pathology services in Singapore. Moreover, as dysphagia services are heavily supported by other healthcare professionals, it is necessary to increase workforce capacity and capability of other professions as services continue to expand. This has been highlighted as a key service barrier by studies conducted in a range of countries, including Singapore, where clinicians reported issues relating to multidisciplinary collaboration and support, such as poor understanding of the SLP role and inappropriate referrals (Egan et al., Citation2020; Eltringham et al., Citation2022; Lal et al., Citation2023; Miles et al., Citation2016; Poon et al., Citation2023a).

In addition, both SLP and manager groups prioritised improving care transitions across services by enhancing communication, having access to patients’ clinical records, having a directory of speech-language pathology services in Singapore, and simplifying referral processes. These findings further validate the results of a recent local survey, in which more than 34 of the 68 (>50%) participating SLPs working in the acute and subacute settings reported experiencing challenges with care transitions (Poon et al., Citation2023a). The need to improve care transitions is also echoed by the international community with clinicians describing delayed and limited access to community and outpatient dysphagia services (Egan et al., Citation2020; Steele et al., Citation2007) and breakdown in the handover of information between services (Horgan et al., Citation2020; Miles et al., Citation2016). A potential solution to enhance communication between services is the use of an electronic discharge summary. This modality is known to increase accessibility, timeliness, and accuracy of information transfer as well as clinician and patient satisfaction (Motamedi et al., Citation2011; Newnham et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, the participants in this study also advocated for increased access to patients’ medical records, which further highlighted their need for improved information sharing. The prioritised suggestions of having a directory of speech-language pathology services and simplifying referral processes are more specific to the Singapore context, and these are likely related to the unique local service barriers surrounding the healthcare financing framework and referral process for subsidised patients living in Singapore (Lim et al., Citation2018; Poon et al., Citation2023a). Improving care transition is critical, as issues in this area can adversely affect service delivery, compromise care quality, and lead to increased clinical workload (King et al., Citation2013; Poon et al., Citation2023a). This aspect is especially important in Singapore as more patients are likely to be transferred from acute to subacute healthcare facilities for ongoing care due to the Ministry of Health’s focus on community-based healthcare provision (Ministry of Health, Singapore, Citation2016).

Both SLPs and managers also identified the need to increase consumers’ access to support and educational resources. This reflects findings of the Singapore-based survey in which 38 of the 68 (56%) SLPs reported experiencing challenges when providing dysphagia education due to language barriers, poor understanding of a dysphagia diagnosis by patients and caregivers, and difficulties scheduling patient/caregiver education sessions (Poon et al., Citation2023a). Similarly, patients and caregivers living in other countries have shared that they received impractical, complex, and conflicting dysphagia care information (Govender et al., Citation2017; Miles et al., Citation2016; Nund et al., Citation2014) with limited post-discharge dysphagia support (Helldén et al., Citation2018), which has resulted in confusion regarding care plans and poor therapy participation (Govender et al., Citation2017; Miles et al., Citation2016). Given these issues, it is not surprising that patients and caregivers face unanticipated difficulties and dysphagia care burden (Greysen et al., Citation2017; Rangira et al., Citation2022), which further validates the need for increased access to support and educational resources. A potential solution, as suggested by the SLPs and managers in this study, is the creation of an online dysphagia resource library. This resource library would allow consumers to have access to support and educational materials at their convenience, and assist in overcoming the organisational and time constraints associated with scheduling education sessions. Once again, the unique local issue relating to dysphagia education with a linguistically diverse group of foreign domestic caregivers is acknowledged in this study. To address this, the managers and SLPs recommended for dysphagia educational materials to be developed in various languages to ensure accessibility of information to optimise education and patient care.

The SLPs and managers in this study also advocated for accessible telehealth services. The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated the rapid and widespread uptake of dysphagia telehealth services globally (Ward et al., Citation2022), but recent studies conducted in Singapore suggested poor adoption of dysphagia telehealth services by clinicians, with up to 35% of the SLPs surveyed providing the service in 2021 (Peh et al., Citation2023; Poon et al., Citation2023a). Despite this, there are suggestions that SLPs in Singapore are now ready to adopt this service modality, given the associated clinical, logistic, and infrastructure service barriers have become significantly less pronounced after the pandemic (Peh et al., Citation2023). This shift in perception is corroborated by the findings of the current study, with SLPs prioritising telehealth service models. Importantly, international studies have also supported the use of telehealth to provide dysphagia care due to its many benefits, including increased service efficiency, better clinical outcomes, and higher cost savings compared to traditional care models (Ward et al., Citation2022). Given these benefits, increasing access to telehealth services is likely to optimise dysphagia care, especially as telehealth becomes part of regular healthcare delivery due to the growing emphasis on digital health internationally.

Limitations

There are several limitations to be considered. Due to self-select sampling, the findings reflect the views of those who have participated and not of every clinician in Singapore. However, maximum variation sampling was used to recruit clinicians of diverse backgrounds and the stress values of the concept maps confirmed acceptable representation of data (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007; Sturrock & Rocha, Citation2000). In addition, clinicians employed by community services were excluded from this study, hence, their views and needs were not considered, and could be explored in future studies to confirm and extend these findings.

Conclusions

SLPs and managers in Singapore identified similar issues that require change across all aspects of dysphagia services, and generated a set of comparable prioritised service enhancements that are needed to improve dysphagia services in Singapore. Many of these identified issues and service changes are similar and applicable to other countries. This data provides clear future directions for dysphagia service enhancement and implementation in Singapore. However, while the viewpoint of SLPs and managers is key information to guide change, this must also be synthesised with consumer perceptions. As such, these findings will be combined with results of another concept mapping study involving patients and carers (Poon et al., Citation2023b) to help drive an agenda that improves dysphagia services and addresses the holistic needs of clinicians, patients, and carers in Singapore.

Supplemental Material

Download PNG Image (1.1 MB)SG provider concept map_SUPP MAT_Interview_24 Nov2023.docx

Download MS Word (15.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all SLPs and managers who participated in this study for their valuable contributions, and Dr Jasmine Foley for her support in the concept mapping methodology.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2004). Preferred practice patterns for the profession of speech-language pathology. www.asha.org/policy

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2023). ASHA practice policy. https://www.asha.org/policy/

- Archer, S. K., Wellwood, I., Smith, C. H., & Newham, D. J. (2013). Dysphagia therapy in stroke: A survey of speech and language therapists. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(3), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12006

- Bar, H., & Mentch, L. (2017). R-CMap—An open-source software for concept mapping. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60, 284–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.018

- Bhattacharyya, N. (2014). The prevalence of dysphagia among adults in the United States. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery: Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 151(5), 765–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599814549156

- Bray, B. D., Smith, C. J., Cloud, G. C., Enderby, P., James, M., Paley, L., Tyrrell, P. J., Wolfe, C. D., & Rudd, A. G, SSNAP Collaboration. (2017). The association between delays in screening for and assessing dysphagia after acute stroke, and the risk of stroke-associated pneumonia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 88(1), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2016-313356

- Carnaby, G. D., & Harenberg, L. (2013). What is “usual care” in dysphagia rehabilitation: A survey of USA dysphagia practice patterns. Dysphagia, 28(4), 567–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-013-9467-8

- Chen, B. J., Suolang, D., Frost, N., & Faigle, R. (2022). Practice patterns and attitudes among speech-language pathologists treating stroke patients with dysphagia: A nationwide survey. Dysphagia, 37(6), 1715–1722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-022-10432-6

- Cohen, S. M., Lekan, D., Risoli, T., Jr., Lee, H. J., Misono, S., Whitson, H. E., & Raman, S. (2020). Association between dysphagia and inpatient outcomes across frailty level among patients ≥ 50 years of age. Dysphagia, 35(5), 787–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-019-10084-z

- Egan, A., Andrews, C., & Lowit, A. (2020). Dysphagia and mealtime difficulties in dementia: Speech and language therapists’ practices and perspectives. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(5), 777–792. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12563

- Eltringham, S. A., Bray, B. D., Smith, C. J., Pownall, S., & Sage, K. (2022). Are differences in dysphagia assessment, oral care provision, or nasogastric tube insertion associated with stroke-associated pneumonia? A nationwide survey linked to national stroke registry data. Cerebrovascular Diseases (Basel, Switzerland), 51(3), 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1159/000519903

- Govender, R., Wood, C. E., Taylor, S. A., Smith, C. H., Barratt, H., & Gardner, B. (2017). Patient experiences of swallowing exercises after head and neck cancer: A qualitative study examining barriers and facilitators using behaviour change theory. Dysphagia, 32(4), 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9799-x

- Graham, J. E., Middleton, A., Roberts, P., Mallinson, T., & Prvu-Bettger, J. (2018). Health services research in rehabilitation and disability-The time is now. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 99(1), 198–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.06.026

- Greysen, S. R., Harrison, J. D., Kripalani, S., Vasilevskis, E., Robinson, E., Metlay, J., Schnipper, J. L., Meltzer, D., Sehgal, N., Ruhnke, G. W., Williams, M. V., & Auerbach, A. D. (2017). Understanding patient-centred readmission factors: A multi-site, mixed-methods study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 26(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004570

- Helldén, J., Bergström, L., & Karlsson, S. (2018). Experiences of living with persisting post-stroke dysphagia and of dysphagia management – A qualitative study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 13(sup1), 1522194. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1522194

- Hesselink, G., Flink, M., Olsson, M., Barach, P., Dudzik-Urbaniak, E., Orrego, C., Toccafondi, G., Kalkman, C., Johnson, J. K., Schoonhoven, L., Vernooij-Dassen, M., & Wollersheim, H, On Behalf of the European HANDOVER Research Collaborative. (2012). Are patients discharged with care? A qualitative study of perceptions and experiences of patients, family members and care providers. BMJ Quality & Safety, 21(1 Suppl), i39–i49. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001165

- Horgan, E., Lawson, S., & O'Neill, D. (2020). Oropharyngeal dysphagia among patients newly discharged to nursing home care after an episode of hospital care. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 189(1), 295–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-019-02061-0

- Howells, S. R., Cornwell, P. L., Ward, E. C., & Kuipers, P. (2019a). Dysphagia care for adults in the community setting commands a different approach: Perspectives of speech–language therapists. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(6), 971–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12499

- Howells, S. R., Cornwell, P. L., Ward, E. C., & Kuipers, P. (2019b). Understanding dysphagia care in the community setting. Dysphagia, 34(5), 681–691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-018-09971-8

- Jones, E., Speyer, R., Kertscher, B., Denman, D., Swan, K., & Cordier, R. (2018). Health-related quality of life and oropharyngeal dysphagia: A systematic review. Dysphagia, 33(2), 141–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9844-9

- Jones, O., Cartwright, J., Whitworth, A., & Cocks, N. (2018). Dysphagia therapy post stroke: An exploration of the practices and clinical decision-making of speech-language pathologists in Australia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(2), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2016.1265588

- Kane, M., & Trochim, W. M. (2007). Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412983730

- King, B. J., Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A. L., Roiland, R. A., Polnaszek, B. E., Bowers, B. J., & Kind, A. J. (2013). The consequences of poor communication during transitions from hospital to skilled nursing facility: A qualitative study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(7), 1095–1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12328

- Lal, P. B., Wishart, L. R., Ward, E. C., Schwarz, M., Seabrook, M., & Coccetti, A. (2020). Understanding speech pathology and dysphagia service provision in Australian emergency departments. Speech, Language and Hearing, 25(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2020.1833469

- Lal, P. B., Wishart, L. R., Ward, E. C., Schwarz, M., Seabrook, M., & Coccetti, A. (2023). Understanding barriers and facilitators to speech-language pathology service delivery in the emergency department. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25(4), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2071465

- Leder, S. B., & Suiter, D. M. (2009). An epidemiologic study on aging and dysphagia in the acute care hospitalized population: 2000–2007. Gerontology, 55(6), 714–718. https://doi.org/10.1159/000235824

- Leder, S. B., Suiter, D. M., Agogo, G. O., & Cooney, L. M. Jr. (2016). An epidemiologic study on ageing and dysphagia in the acute care geriatric-hospitalized population: A replication and continuation study. Dysphagia, 31(5), 619–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-016-9714-x

- Lim, M. L., Yong, B. Y. P., Mar, M. Q. M., Ang, S. Y., Chan, M. M., Lam, M., Chong, N. C. J., & Lopez, V. (2018). Caring for patients on home enteral nutrition: Reported complications by home carers and perspectives of community nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(13–14), 2825–2835. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14347

- Mathers-Schmidt, B. A., & Kurlinski, M. (2003). Dysphagia evaluation practices: Inconsistencies in clinical assessment and instrumental examination decision-making. Dysphagia, 18(2), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-002-0094-z

- McCurtin, A., & Healy, C. (2017). Why do clinicians choose the therapies and techniques they do? Exploring clinical decision-making via treatment selections in dysphagia practice. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2016.1159333

- Miles, A., Watt, T., Wong, W. Y., McHutchison, L., & Friary, P. (2016). Complex feeding decisions: Perceptions of staff, patients, and their families in the inpatient hospital setting. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 2, 2333721416665523. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721416665523

- Ministry of Health Singapore. (2016). April 13). Speech by Minister for Health, Mr Gan Kim Yong, at the MOH Commitee of Supply debate 2016 [Press release]. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/speech-by-minister-for-health-mr-gan-kim-yong-at-the-moh-committee-of-supply-debate-2016

- Ministry of Health Singapore. (2023). Health facilities [Data set]. https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/singapore-health-facts/health-facilities

- Motamedi, S. M., Posadas-Calleja, J., Straus, S., Bates, D. W., Lorenzetti, D. L., Baylis, B., Gilmour, J., Kimpton, S., & Ghali, W. A. (2011). The efficacy of computer-enabled discharge communication interventions: A systematic review. BMJ Quality & Safety, 20(5), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2009.034587

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2019). Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: Diagnosis and initial management (NICE Guideline NG128). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng128

- Newnham, H., Barker, A., Ritchie, E., Hitchcock, K., Gibbs, H., & Holton, S. (2017). Discharge communication practices and healthcare provider and patient preferences, satisfaction and comprehension: A systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 29(6), 752–768. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzx121

- Nund, R. L., Ward, E. C., Scarinci, N. A., Cartmill, B., Kuipers, P., & Porceddu, S. V. (2014). Carers’ experiences of dysphagia in people treated for head and neck cancer: A qualitative study. Dysphagia, 29(4), 450–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9527-8

- Paranji, S., Paranji, N., Wright, S., & Chandra, S. (2017). A nationwide study of the impact of dysphagia on hospital outcomes among patients with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 32(1), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317516673464

- Patel, D. A., Krishnaswami, S., Steger, E., Conover, E., Vaezi, M. F., Ciucci, M. R., & Francis, D. O. (2018). Economic and survival burden of dysphagia among inpatients in the United States. Diseases of the Esophagus: Official Journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus, 31(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/dox131

- Peh, H. P., Yee, K., & Mantaring, E. J. N. (2023). Changes in telepractice use and perspectives among speech and language therapists in Singapore through the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 58(3), 802–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12823

- Pettigrew, C. M., & O'Toole, C. (2007). Dysphagia evaluation practices of speech and language therapists in Ireland: Clinical assessment and instrumental examination decision-making. Dysphagia, 22(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-007-9079-2

- Poon, F. M. M., Ward, E. C., & Burns, C. L. (2023a). Adult dysphagia services in acute and subacute settings in Singapore. Speech, Language and Hearing, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2023.2240988

- Poon, F. M. M., Ward, E. C., & Burns, C. L. (2023b). Identifying prioritised actions for improving dysphagia services in Singapore: Insights from concept mapping with patients and caregivers. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12977

- Rangarathnam, B., & Desai, R. V. (2020). A preliminary survey of dysphagia practice patterns among speech-language pathologists in India. Journal of Indian Speech Language & Hearing Association, 34(2), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.4103/jisha.JISHA_20_19

- Rangira, D., Najeeb, H., Shune, S. E., & Namasivayam-MacDonald, A. (2022). Understanding burden in caregivers of adults with dysphagia: A systematic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(1), 486–501. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-21-00249

- Rivelsrud, M. C., Hartelius, L., Bergström, L., Løvstad, M., & Speyer, R. (2023). Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults in different healthcare settings: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Dysphagia, 38(1), 76–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-022-10465-x

- Rowland, S., Mills, C., & Walshe, M. (2023). Perspectives on speech and language pathology practices and service provision in adult critical care settings in Ireland and international settings: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2032346

- Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. (2023). RCSLT Home. https://www.rcslt.org/

- Rumbach, A., Coombes, C., & Doeltgen, S. (2018). A survey of Australian dysphagia practice patterns. Dysphagia, 33(2), 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9849-4

- Schwarz, M., Ward, E. C., Cornwell, P., Coccetti, A., D'Netto, P., Smith, A., & Morley-Davies, K. (2020). Exploring the validity and operational impact of using allied health assistants to conduct dysphagia screening for low-risk patients within the acute hospital setting. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(4), 1944–1955. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00060

- Sherman, V., Greco, E., & Martino, R. (2021). The benefit of dysphagia screening in adult patients with stroke: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association, 10(12), e018753. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.018753

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2012). Dysphagia clinical guideline. https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Members/Clinical_Guidelines/spaweb/Members/Clinical_Guidelines/Clinical_Guidelines.aspx?hkey=f66634e4-825a-4f1a-910d-644553f59140

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2023). Practice guidelines. https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Members/Clinical_Guidelines/spaweb/Members/Clinical_Guidelines/Clinical_Guidelines.aspx?hkey=f66634e4-825a-4f1a-910d-644553f59140

- Steele, C., Allen, C., Barker, J., Buen, P., French, R., Fedorak, A., Day, S., Lapointe, J., Lewis, L., & MacKnight, C. (2007). Dysphagia service delivery by speech-language pathologists in Canada: Results of a national survey. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 31(4), 166–177. https://cjslpa.ca/files/2007_CJSLPA_Vol_31/CJSLPA_2007_Vol_31_No_04_Winter.pdf#page=7

- Stroke Foundation. (2022). Clinical guidelines for stroke management. https://informme.org.au/guidelines

- Sturrock, K., & Rocha, J. (2000). A multidimensional scaling stress evaluation table. Field Methods, 12(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X0001200104

- United Nations Population Division. (2019). Robabilistic population projections based on the World Population Prospects 2019 [Data set]. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Probabilistic/Population/

- Ward, E. C. (2019). Elizabeth Usher memorial lecture: Expanding scope of practice – Inspiring practice change and raising new considerations. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(3), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2019.1572224

- Ward, E. C., Raatz, M., Marshall, J., Wishart, L. R., & Burns, C. L. (2022). Telepractice and dysphagia management: The era of COVID-19 and beyond. Dysphagia, 37(6), 1386–1399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-022-10444-2

- Yang, S., Park, J.-W., Min, K., Lee, Y. S., Song, Y.-J., Choi, S. H., Kim, D. Y., Lee, S. H., Yang, H. S., Cha, W., Kim, J. W., Oh, B.-M., Seo, H. G., Kim, M.-W., Woo, H.-S., Park, S.-J., Jee, S., Oh, J. S., Park, K. D., … Choi, K. H. (2023). Clinical practice guidelines for oropharyngeal dysphagia. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine, 47(1 Suppl), S1–S26. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.23069