Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the characteristics of studies that included underrepresented speech-language pathologists (SLPs) as research participants.

Method

A scoping review was conducted using the principles of the transformative research paradigm, which promotes the meaningful involvement and empowerment of marginalised groups. Co-production with minority SLPs was facilitated. The search strategy was run in six databases, and the transformative checklist used for analysis.

Result

Twenty studies were included. Bilingual and male SLPs were among the most commonly included underrepresented SLPs. Most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 16), and used survey methods. The studies provided valuable insights into the experiences and practices of underrepresented SLPs, and yielded practical solutions to foster inclusion and diversity in the profession. Most studies demonstrated a transformative potential, but the active engagement of underrepresented SLP participants in the research cycle was rarely demonstrated.

Conclusion

This review calls for a shift in how and why research is conducted when including underrepresented SLP participants. Through the lens of the transformative research paradigm, we can rethink the broader aim of research and the role of researchers and participants. Using research as a platform to give visibility, voice, and agency to minority groups can stimulate change and equity in the profession.

Introduction

Globally, the most visible and influential speech-language pathology communities are those based in high-income English-speaking countries, such as Australia, the UK, and the USA, and are predominantly comprised of White, monolingual, able-bodied, middle-class women (Boyd & Hewlett, Citation2001; Richburg, Citation2022; Stapleford & Todd, Citation1998). Those in other contexts, especially in low- and middle-income countries where the need for speech-language pathology services is the highest (World Health Organization, Citation2022), are often influenced by service models developed in the more established Western communities (Staley et al., Citation2022; Wylie et al., Citation2018). The lack of diverse voices steering the profession, both locally and globally, raises concerns of inadvertently marginalising groups and perpetuating the same views and practices, thereby limiting the impact of speech-language pathology services and risking widening inequities.

There is increasing recognition of these issues, and initiatives are emerging to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion at all levels of the speech-language pathology profession. These efforts include the diversification of the workforce and their education at national or local scales, with a focus on workforce profiling analyses (Nancarrow et al., Citation2023; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2023), recruitment processes (Guiberson & Vigil, Citation2021), training approaches (Attrill et al., Citation2022), competence frameworks (Hopf et al., Citation2021), and leadership strategies (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, Citation2022). Initiatives also exist to transform clinical practice, such as by adjusting service delivery models to better meet the needs of marginalised clients (Abrahams et al., Citation2019). Beyond workforce, education, and practice-oriented efforts, scholars in the field of speech-language pathology are also increasingly adopting research practices that fundamentally acknowledge and aim to address issues of diversity and inclusion. These recent advancements reflect the broader development of equity-oriented health research for marginalised groups, such as found in studies promoting more inclusive and culturally appropriate research initiatives for Indigenous (Harfield et al., Citation2020; Jamieson et al., Citation2012; Laycock et al., Citation2011), Black (Allen et al., Citation2023; Thompson et al., Citation2024), Latinx (Demeke et al., Citation2023; Hernandez-Salinas et al., Citation2023), or LGBTQ+ communities (Hermosillo et al., Citation2022), as well as for persons with disabilities (Gréaux, Moro, et al., Citation2023). In speech-language pathology research, this is exemplified by the use of critical, emancipatory, and Indigenous frameworks and theories to enable the creation of knowledge that is culturally appropriate and responsive to systems of oppression faced by minority communities (Allison-Burbank & Reid, Citation2023; Faithfull et al., Citation2020; Horton, Citation2021; Hyter, Citation2021; Khamis-Dakwar & Randazzo, Citation2021; Meechan & Brewer, Citation2022; Nair et al., Citation2023; Privette, Citation2021; Skeat et al., Citation2022). It is also evidenced in methodological decisions, such as when using participatory designs that give voice and agency to traditionally marginalised groups (Newkirk-Turner & Morris, Citation2021; Roper & Skeat, Citation2022), being responsive to post-colonial contexts (Watermeyer & Neille, Citation2022), and promoting reflexivity to enhance researchers’ cultural awareness and responsiveness (Azul & Zimman, Citation2022). To complement these efforts, a better understanding of how research has been used as a platform to seek and amplify the voices of underrepresented speech-language pathologists (SLPs) will be valuable.

Research that includes underrepresented SLPs as participants, thereby giving them a platform to shape the evidence base that will inform tomorrow’s clinical practices, can be an effective and empowering mechanism to stimulate change towards diversity and inclusion in the profession. This viewpoint is well captured by the transformative research paradigm, which recognises that research is not neutral but rather a dynamic process that fundamentally engages with issues of social justice: It can challenge or perpetuate biases, empower or silence communities, advance or hinder equity (Mertens, Citation2007, Citation2017). Transformative research highlights the critical importance of engaging the marginalised members of our communities in ways that amplify their voices, value their knowledge, and address power inequities (Mertens, Citation2007, Citation2021; Sweetman et al., Citation2010). It also views the role of the researcher as a “social change agent” to achieve this goal, notably by challenging the status quo at all stages of the research cycle, from design to implementation and dissemination. To guide researchers to adopt the principles of transformative research, Sweetman et al. (Citation2010) developed a transformative checklist with 10 criteria indicative of the core epistemological, ontological, and methodological assumptions of this research paradigm (). To the best of our knowledge, the transformative research paradigm has not yet been explicitly introduced in speech-language pathology research.

Table I. The 10 criteria of the transformative checklist (Sweetman et al., Citation2010).

This scoping review adopts a transformative lens to investigate the characteristics of studies that included underrepresented SLPs as research participants. We aim to better understand the knowledge generated, as well as the research processes that have been used and the extent to which they could enable empowerment of underrepresented SLPs. Recommendations to guide future research, operationalise the transformative paradigm, and empower underrepresented SLPs are discussed.

Method

A scoping review was conducted following the framework provided by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), which stipulates six steps: (a) identify the research questions; (b) identify relevant studies; (c) study selection; (d) chart the data; (e) collate, summarise, and report the results; and (f) consultation. The sixth step, regarded as an optional and final step in Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), was recentred as a fundamental mechanism to operationalise the principles of the transformative research paradigm throughout the development of our scoping review. This comprehensive consultative process was completed in alignment with guidance from Westphaln et al. (Citation2021). Supplementary guidance from Peters et al. (Citation2015) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist for systematic scoping reviews (Tricco et al., Citation2018) were followed (Appendix 1, Supplementary Material).

Identify the research questions

This scoping review aimed to investigate the characteristics of studies that included underrepresented SLPs as research participants, and was guided by three research questions:

What are the main characteristics of research studies that included underrepresented SLPs in terms of participants’ characteristics, geographic distribution, publication years, and studies’ aims and designs?

Which insights do these studies provide on the perspectives, experiences, and practices of underrepresented SLPs?

To what extent do these studies align with the principles of transformative research, as informed by the 10 criteria of the transformative checklist ()?

Identify relevant studies

The search strategy was framed around two key concepts: speech-language pathology workforce and minority groups. The UN list of vulnerable groups (United Nations, Citationn.d.) and the UK list of protected characteristics (Government of the United Kingdom, Citationn.d.) were consulted to inform the search strategy and avoid any oversight on commonly marginalised communities. However, we recognise that our search strategy could have been further expanded, most notably by specifying groups of Indigenous Peoples such as Māori, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, or First Nations Peoples. Importantly, this highlights the need to be critical on how post-colonial biases may transpire in commonly used lists of minority groups, and gives impetus for more consultation with the representative organisations of minority communities in research. The keywords were further developed using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or equivalent headings, as well as those from other reviews on similar topics. Boolean, truncation, and proximity operators were used to construct and combine searches, and adjustments were made as required for individual databases. The search strategy was validated and run in collaboration with two librarians at the University of Cambridge Medical Library School Library. provides the list of keywords used in the search strategy. The search strategy developed for PsycInfo (via Ebsco) is provided in Appendix 2, Supplementary Material.

Table II. List of keywords used in the search strategy.

The systematic search was conducted on six databases on 29 June 2022: (a) MEDLINE (Ovid), (b) Web of Science, (c) PsycINFO, (d) CINAHL, (e) LLBA, and (f) AMED. Additionally, the Cochrane Library was searched. The grey literature was not searched since this review aimed to capture published research evidence only.

Study selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to identify the relevant literature. Peer-reviewed empirical studies with underrepresented SLPs and speech-language pathology students as participants were included. Underrepresented SLP participants were identified by any disclosed personal attributes that were evidenced or inferred minoritised in the workforce at country level, such as gender and gender identity, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, immigration status, socioeconomic status, or linguistic competence. Papers solely including majority SLPs, lacking the direct engagement with participants (i.e. secondary research), or only providing descriptive information about participants’ demographic characteristics with no primary intent to investigate or disaggregate other data from underrepresented SLPs were excluded. Papers published over the last 10-year period (2012–2022) in languages accessible by the research team (English, French, Greek, and Spanish) were included. Finally, papers using a range of empirical research designs (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods) were included but commentaries, opinion pieces, theoretical papers, blogs, clinical guidelines, book chapters, and theses were excluded.

Initial search results were screened for eligibility according to title and abstract screening on Rayyan, a free web tool designed to track decisions and facilitate collaboration between reviewers. MG screened 100% of the titles and abstracts, and KC screened a 20% random sample (n = 1,977). Following this blinded review process, only three papers were in disagreement between MG and KC, which resulted in a kappa score (κ = 1.00) indicating perfect agreement. Consensus on these three papers was reached through discussions. The full texts were then retrieved and reviewed collaboratively by MG and KC. The extraction of references, deduplication process, and reference management were conducted in EndNote 20.4.

Chart the data

A data charting form was developed for this review. The following characteristics were extracted for each included paper: author(s), title, year of publication, journal, country, aim(s) of the study, methodology and methods, participants’ characteristics, main outcomes, and additional remarks.

Collate, summarise, and report the results

The results were synthesised according to the three research questions. Firstly, descriptive statistics were calculated to identify trends in terms of participants’ characteristics, geographic distribution, and studies’ aims and designs. Secondly, the findings of the included studies were summarised to provide insights into the unique perspectives, experiences, and practices of underrepresented SLPs. Here, we only extracted the studies’ findings that reported on underrepresented SLP participants’ data so as to amplify their voices, and synthesised them according to the structure of the CHAT-ICF framework (see below). Thirdly, the transformative checklist developed by Sweetman et al. (Citation2010) was used to determine the extent to which these studies aligned with the principles of transformative research (). Here, we recognise that it would be unfair to expect the authors of included studies to have adhered to the tenets of the transformative research paradigm when they may not have aspired to do so. Our aim is rather to review these studies through this new lens to identify existing good practices, and inform recommendations to further enhance the transformative potential of future studies.

MG reviewed and extracted data for all papers. KC, FG, and VP were allocated a random sample of up to three papers to review. The randomisation process was weighed to maximise the overlap between the profiles of KC, FG, and VP and the study participants, hence allowing them to amplify and/or nuance the ideas voiced by individuals of similar underrepresented communities in the workforce (Westphaln et al., Citation2021). MG collated all responses and synthesised the findings. All authors contributed and provided feedback to drafts.

CHAT-ICF

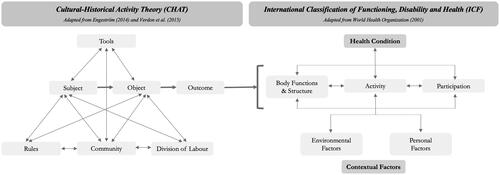

The CHAT-ICF framework is a theoretical framework developed to conceptualise the activities of professionals working in the field of disability and rehabilitation (Gréaux et al., Citation2024). This framework is comprised of two widely accepted frameworks: the Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT second generation; Engeström, Citation2014) and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; World Health Organization, Citation2001; ).

Figure 1. CHAT-ICF framework: Conceptualising the activities of professionals working in the field of disability and rehabilitation.

On one hand, CHAT enables the conceptualisation of SLPs’ clinical practice. Through CHAT, clinical practice is represented in the form of “activity systems” informed by seven aspects: (a) subject (the person undertaking the action), (b) object (the motivation for individuals to engage in an activity), (c) outcome (every activity system is working towards the achievement of an outcome), (d) tools (used by the subject to work towards attaining the object), (e) rules (the formal and informal principles or procedures by which an activity is governed), (f) community (social context or group to which the people in the activity system belong), and (g) division of labour (assignment of roles among people within the activity system). CHAT has already been used to investigate speech-language pathology practice in the field of inclusive education (Wakefield, Citation2007) and for linguistically and culturally diverse clients (Verdon et al., Citation2015).

On the other hand, ICF supports the conceptualisation of disability and has been used by clinicians and researchers in the field of speech-language pathology (Cunningham et al., Citation2017; Ma, Citation2018; McLeod & Threats, Citation2008; McNeilly, Citation2018). Through ICF, disability is conceptualised according to seven aspects: (a) health condition, (b) body functions (physiological functions of body systems), (c) body structures (anatomical parts of the body), (d) activities (execution of tasks or actions), (e) participation (involvement in life situations), (f) environmental factors (physical, social, and attitudinal environment), and (g) personal factors (background of an individual’s life and living, such as age, gender, race, lifestyle, education, etc.).

By merging the CHAT and ICF frameworks, a novel model is developed to conceptualise the activities of professionals working in the field of disability and rehabilitation. Adopting CHAT-ICF in the field of speech-language pathology, the clinician is positioned as the subject of an activity system whose desired outcome is to support individuals with speech-, language-, and communication-related disability. With CHAT-ICF, ICF becomes the extension of the outcome element of the CHAT framework, which allows elaboration of the subject’s activity system as directed towards—and interacting with—the more specific elements of disability. CHAT-ICF can support the conceptualisation of the complexity and dynamic nature of speech-language pathology practice by promoting the identification of dissonance and consonance between aspects of service delivery and the experiences of persons with disabilities. In turn, CHAT-ICF can be used to inform more integrated, person-centred, transformative, and equitable speech-language pathology services. CHAT-ICF has already been used to analyse the experiences and practices of bilingual and autistic SLPs (Gréaux, Gibson, et al., Citation2023; Gréaux, Katsos, et al., Citation2023). In this review, CHAT-ICF was used to synthesise the findings of studies according to the well-defined subjects (underrepresented SLP participants), and explore the extent to which being an underrepresented member of the speech-language pathology workforce can affect various aspects of their professional experiences and practices.

Collaboration and positionality

The protocol was published on an open access online platform and disseminated via social media for a 2-week consultation in June 2022.Footnote1 During this time, six individuals provided feedback, including three identifying as underrepresented SLPs. This consultation helped to confirm the suitability of a scoping review approach, identify the most relevant databases, refine the inclusion criteria, and complement keywords to the search strategy. Additionally, MG received funding from the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists’ (RCSLT) minor grant scheme to recruit and collaborate with KC, FG, and VP, all identifying as underrepresented SLPs, hence operationalising the principles of the transformative paradigm.

Reflexivity and positionality were critical considerations in this research. All authors critically reflected on their identity, biases, assumptions, and privilege, and how these may influence their views and interpretations. Importantly, we also reflected on the complexity of our positionality and privilege. For example, all authors worked in Western English-speaking contexts recognising speech-language pathology as a profession with colonial influences (Abrahams et al., Citation2019; Ganek, Citation2021). Some identified as underrepresented SLPs but fundamentally appreciated that their experiences are not representative of others in similar groups in the profession. This led to unique implications for how each author related to the concepts of saviourism, humility, and self-subjugation. Reflexive practices enabled us to engage with and navigate this complexity, as well as raise awareness of our own responsibilities and limitations to contribute to this topic in speech-language pathology research. This was done by completing a reflexive diary and through group discussions (Guyan, Citation2017).

This study was initiated and led by MG, a White, female, bilingual (French, English) trained SLP and doctoral researcher in the UK. MG is interested in issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the speech-language pathology profession and more broadly in the rehabilitation and health sector, as well as in ways to optimise research methods to facilitate social change. KC is an autistic, non-heterosexual, White SLP working in the UK. She has interests in understanding the therapy professions through a social justice lens and co-production of research through inclusive practices. FG is a multilingual (English, Gujarati, Hindi) South Asian SLP practising in the UK, with clinical interests in promoting culturally appropriate dysphagia care. Her professional interests include encouraging greater recruitment and retention of minoritised SLPs. VP is a cisgendered, gay, male, South-East Asian SLP practising in New Zealand, with clinical interests in disrupting ableism in stuttering/stammering therapy and professional interests in amplifying the voices of minority SLPs alongside the diversification of the SLP community. NK is a bilingual (Greek, English) academic from a White, middle class, Greek background who moved to England for further studies and work. He has professional and personal interests in speech-language pathology service provision and professional development, including in multilingual contexts, and is married to a SLP. He collaborates with SLPs in research and public engagement activities. JG is an academic and a qualified SLP with personal and professional interests in disability and neurodiversity. JG is from a White, working class British background and speaks English (home language) and some Spanish (learned in adulthood). She is interested in intersectionality and inclusion in the speech-language pathology profession.

Result

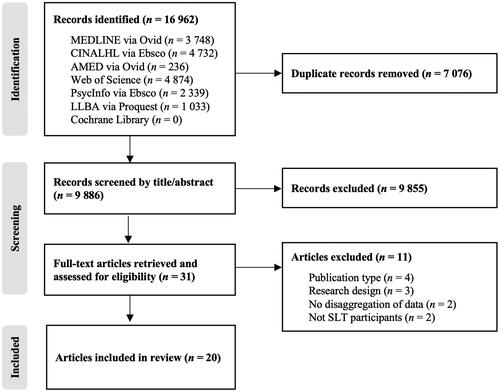

In total, 20 papers were included in this scoping review (). All papers were accessible in English, except for one paper written in Spanish (Nieva et al., Citation2020). details the characteristics of each included paper.

Figure 2. PRISMA flowchart adapted from Tricco et al. (Citation2018).

Table III. Characteristics of the studies included in this review.

Overview

Participants’ characteristics

Bilinguals were the most included underrepresented participants in speech-language pathology research, accounting for 40% of all included studies (n = 8). This was followed by five studies including participants with a mix of underrepresented attributes in the workforce, most notably through the amalgamation of ethnicity and/or linguistic status and/or socio-economic status and/or immigrant status. Three studies included male participants. Two studies included persons with disabilities, including one study with a clinician with hearing loss and another with speech-language pathology students who stutter. Finally, two studies included participants with ethnic minority backgrounds. There was an almost even distribution between studies with qualified SLPs (n = 11) and speech-language pathology students (n = 8), and one study included both.

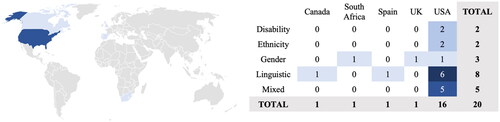

Geographic distribution

Most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 16), followed by one study in each of the following countries: Canada, South Africa, Spain, and the UK (). All countries are high-income countries except for South Africa, which is classified by the World Bank as an upper-middle income country.Footnote2

Figure 3. Map and table illustrating geographical and group distribution. Grey boxes indicate evidence towards the transformative criteria (deleting the mention of the white boxes because it should be self-explanatory). The map was produced on Microsoft Excel version 16.70 powered by Bing, Australian Bureau of Statistics, GeoNames, Microsoft, Navinfo, OpenStreetMap, TomTom, Zenrin (21.03.2023).

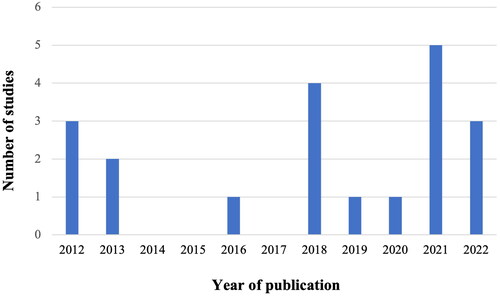

Publication years

The most prolific year of publication for studies including underrepresented SLP participants in the past decade was 2021 (n = 5). Relatively more studies were published in recent years, but there was no evidence indicating substantial changes overall ().

Study aims and designs

Four main categories of research aims were identified. These are described below and ordered from the highest to lowest potential fit with the transformative research perspective.

Firstly, four studies (20%) reported interventions to support underrepresented SLPs. These studies mostly targeted speech-language pathology students (n = 3) and those belonging to linguistic minority groups (n = 3). The most variety of research designs was observed among this category, from qualitative designs using mixed methods (Mahendra & Kashinath, Citation2022) to quantitative designs evaluating pre-post intervention effects (Wofford & Morrow-Odom, Citation2016).

Secondly, six studies (30%) sought to elicit the experiences and perspectives of underrepresented SLPs and speech-language pathology students on their clinical experiences and/or training. Among them, two studies included male SLP participants, two studies included SLP participants with disabilities, and two studies included SLP participants with mixed underrepresented attributes. Most followed a primarily qualitative research design (n = 4) and had a small sample size of three or fewer participants (n = 4).

Thirdly, two studies (10%) focused on a social construct related to the underrepresented attribute. One study elicited the views of speech-language pathology students about White privilege using a quantitative survey method (Ebert, Citation2013). The other study investigated the role of gender in the speech-language pathology profession using a primarily qualitative design (Litosseliti & Leadbeater, Citation2013).

Finally, the most prolific category of studies (40%) comprised eight studies investigating speech-language pathology service delivery or training with disaggragetion of data by SLPs with different attributes. All these studies followed a primarily quantitative research design using surveys. Most included qualified SLPs as participants (n = 6) and compared trends between bilingual and monolingual SLPs (n = 5).

Summary of the findings

The 20 included studies gave underrepresented SLPs and speech-language pathology students a platform to share their unique perspectives, experiences, and practices. Below is an overview of these findings, grouped according to the components of the CHAT-ICF framework ().

Subject

The complex and multidimensional facets of underrepresented SLPs’ identities and experiences were reported, highlighting the importance of challenging assumptions and reductionist views. Male SLPs expressed how their masculinity and sexuality could be questioned, and that they were often presumed as being gay (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021). Participants with disabilities described the complex interactions between their disability and mental health, which represented important considerations in their professional life (Hudock et al., Citation2018; Westby, Citation2021). Lastly, clinicians with linguistic and ethnic minority backgrounds often used an intersectional lens to express their experiences (Lowell et al., Citation2018).

The past experiences of underrepresented SLPs could play a significant role in their decision to become SLPs. For example, participants with disabilities revealed strong similarities with the personal factors of their clients with disabilities (ICF) and described how having had exposure to speech-language pathology as clients themselves facilitated their decision to seek a career in this field (Hudock et al., Citation2018; Westby, Citation2021). Participants with linguistic and ethnic minority backgrounds were motivated to join the profession to give back to their community and support them to achieve a better future (Lowell et al., Citation2018). This contrasted with male participants who were more likely to stumble into the profession (Du Plessis, Citation2018).

Tools

The lived experiences of underrepresented SLPs could inform their knowledge and skills, most notably through a certain intuition, appreciation, or integration of the personal and environmental factors that can regulate the experiences of their clients in their services (ICF). For example, bilingual SLPs demonstrated higher knowledge on bilingual development than their monolingual peers (D'Souza et al., Citation2012; Narayanan & Ramsdell, Citation2022; Nieva et al., Citation2020). Speech-language pathology students who stutter reported an increased awareness of avoidance strategies that clients who stutter use (Hudock et al., Citation2018), and a qualified practitioner with a hearing loss developed strategies to read non-verbal social cues (Westby, Citation2021). Evolving in a female-dominated environment made male SLPs more aware of different communication styles (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021; Du Plessis, Citation2018).

However, it is critical not to assume that lived experiences would automatically resonate with those of their clients with whom they may share similar personal or environmental factors (ICF), or transfer into professional competencies, and tailored support must be provided where needed. For example, bilingual SLPs self-reported lacking the skills to distinguish typical and atypical language or the confidence to interpret speech-language pathology jargon in another language (Núñez et al., Citation2021), but both could be successfully addressed through more formal training (Núñez et al., Citation2021; Wofford & Morrow-Odom, Citation2016). SLPs with disabilities may need support to try new techniques that expose their vulnerability (Hudock et al., Citation2018).

The lack of representation of minority groups in speech-language pathology clinical tools and education were well documented. For example, bilingual SLPs deplored the lack of assessment tools for bilingual clients (D'Souza et al., Citation2012; Núñez et al., Citation2021) and speech-language pathology students of colour reported the over-representation of White families in marketing and educational materials (Ebert, Citation2013). SLPs with linguistic and ethnic minority backgrounds highlighted concerns on current framings of cultural competence in speech-language pathology, and recommended a paradigm shift to promote self-awareness, cultural humility, multicultural training practices, and critical awareness of biases and inequities instead (Ebert, Citation2013; Hudnall, Citation2022; Lowell et al., Citation2018).

Rules

Underrepresented SLPs reported numerous societal and systemic barriers, such as biases or policies, that discriminated against them or their clients with similar personal factors or health conditions (ICF). For example, students who stutter could be advised against becoming SLPs (Hudock et al., Citation2018). SLPs with ethnic minority backgrounds could be given less credibility than their White colleagues (Ebert, Citation2013; Hudnall, Citation2022). Students with lower socioeconomic backgrounds could face barriers to admission into speech-language pathology programs (Fuse, Citation2018). Bilingual SLPs worried that having an accent could create barriers to their school admission and career prospects (Fuse, Citation2018). Male SLPs were confronted with beliefs they were unsuited for certain job requirements, such as playing with children, and feared facing accusations of sexual harassment when working in isolation with females (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021; Du Plessis, Citation2018; Litosseliti & Leadbeater, Citation2013). However, they also recognised that male privilege could benefit their careers, such as better job security, pay, credibility, and faster career progression (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021).

Recommendations were proposed to address discriminatory beliefs and rules in the profession. Male SLPs expressed the need for more guidelines to support and protect them, especially when working with children and young females (Du Plessis, Citation2018), as well as targeted actions to promote the recruitment of male SLPs (Litosseliti & Leadbeater, Citation2013). SLPs with linguistic and ethnic minority backgrounds called for shifts in service delivery models to better meet the needs of underserved clients (Lowell et al., Citation2018). In Mahendra and Kashinath (Citation2022), all underrepresented speech-language pathology students who participated in a yearlong mentoring program valued this opportunity, especially the chance to receive financial assistance and participate in research or community projects. Most students went on to secure funding and scholarships, or opportunities to join professional programs (Mahendra & Kashinath, Citation2022).

Community

The sense of community, inclusion, and belonging to the profession could be challenged for underrepresented SLPs. This was evidenced for SLPs with disabilities as they navigated their professional role while strongly relating to the clients’ position (Hudock et al., Citation2018). Male SLPs reported “sticking out like a sore thumb” (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021). SLPs with ethnic minority backgrounds even reported changing their linguistic register to facilitate their inclusion (Hudnall, Citation2022).

Support networks could nurture a sense of safety, belonging, and empowerment for underrepresented SLPs. For example, speech-language pathology students who stutter shared the benefits of reflecting on their placement experiences with peers (Hudock et al., Citation2018). Male SLPs expressed a desire to connect and find mentors in other males (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021). SLPs with ethnic minority backgrounds wished to initiate forums to spark conversations on racial and cultural differences with their peers (Hudnall, Citation2022). A professional learning community for bilingual SLPs led to feelings of validation and reduced isolation (Núñez et al., Citation2021).

Division of labour

Underrepresented SLPs expressed how their unique positionality shaped their relationships and interactions in the workplace. For instance, a practitioner with hearing loss expressed how parents and school staff had been more receptive to her advice for children with similar conditions since sharing her personal experiences (Westby, Citation2021). Male SLPs recognised that their gender could afford them more respect from other professionals (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021). On the contrary, SLPs with linguistic and ethnic backgrounds faced challenges, such as their clinical decisions being questioned by other professionals (Núñez et al., Citation2021), or being mistaken for being the speech-language pathology assistant (Hudnall, Citation2022).

Participants reported the importance of collaborating with others to inform and optimise the impact of their therapy. Bilingual SLPs mentioned that engaging families and school staff during interventions for bilingual children was pivotal (Nieva et al., Citation2020; Núñez et al., Citation2021), and reported positive experiences collaborating with other bilingual and monolingual SLPs (Epstein, Citation2012; Núñez et al., Citation2021). However, they often deplored the lack of bilingual SLPs, interpreters, and support staff (D'Souza et al., Citation2012; Núñez et al., Citation2021).

Practice

Many underrepresented SLPs expressed how their lived experiences could positively inform their clinical activities. Here, more overlap in personal factors (ICF) between the clinicians and their clients seemed to be associated with increased empathy and confidence, eventually benefiting rapport building and therapy outcomes. For instance, male SLPs indicated “connect(ing) with the boys really well” (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021, p. 10). Bilingual SLPs reported high confidence working with clients with similar backgrounds (Narayanan & Ramsdell, Citation2022; Parveen & Santhanam, Citation2021). SLPs with disabilities reported a strong empathy for clients with similar diagnoses (Westby, Citation2021), which would positively impact rapport building and engagement with clients. However, support may be needed as these high levels of empathy for the clients’ experiences could also trigger the SLPs’ own personal experiences and difficulties (Hudock et al., Citation2018).

Underrepresented SLPs also reflected on their therapy priorities. They often expressed the importance of integrating personal and environmental factors (ICF) in the process, as well as looking at the longer-term, deeper impact of therapy. For instance, a participant with linguistic and ethnic minority background expressed how her positionality made her aware of the importance to “go beyond assessment and treatment and focus on equality and advocacy” (Hudnall, Citation2022, p. 636). Others reported a strong desire to prioritise working with clients from underserved communities, and being more responsive to the personal needs of families with similar backgrounds (Lowell et al., Citation2018). Finally, a practitioner with hearing loss used her lived experiences to work on therapy goals that may not be targeted by traditional speech-language pathology approaches, such as working with children with disabilities on the development of positive self-identity (Westby, Citation2021).

Transformative research

To determine the extent to which these studies align with the principles of transformative research, the transformative checklist developed by Sweetman et al. (Citation2010) was used. A summary on how the authors considered the 10 transformative criteria is provided below (). Importantly, this mapping exercise allowed us to revisit these studies through a new lens, and was in no way a value judgement on the authors’ research outputs and practices. Our aim was rather to identify existing transformative practices in the studies that have enabled the inclusion of underrepresented SLPs in research, and inform recommendations to further enhance the transformative potential of future studies.

Table IV. Transformative criteria of the included studies.

Did the authors openly reference a problem in a community of concern?

Nineteen papers (95%) openly referenced a problem in a community of concern. However, few papers referred to a problem directly relevant to or experienced by underrepresented SLPs. Instead, many referenced issues experienced by people with the same attributes in the wider community—often taking the stance of clients (Westby, Citation2021)—or issues that all SLPs face without consideration of the unique positionality of underrepresented SLPs (D'Souza et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, the sometimes superficial mention of a problem, such as acknowledging the “need for the recruitment and retention of historically under-represented groups in speech-language pathology” (Keshishian & McGarr, Citation2012, p. 174), could be complemented by deeper reflections on why this is needed to enhance the transformative stance of the authors.

Did the authors openly declare a theoretical lens?

Eight papers (40%) mentioned a theoretical lens to their research, such as gender theories (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021; Litosseliti & Leadbeater, Citation2013), intersectionality theories (Du Plessis, Citation2018), social theories (Hudnall, Citation2022), psychological and social theories (Hudock et al., Citation2018), grounded theory (Lowell et al., Citation2018), and racial theories (Ebert, Citation2013). Mahendra and Kashinath (Citation2022) declared transformative frameworks of emancipatory education to underpin their intervention for underrepresented speech-language pathology students, including culturally sustaining and equity pedagogies. The authors of studies using more quantitative research designs tended to show less engagement with theoretical lenses.

Were the research questions written with an advocacy stance?

Twelve papers (60%) worded their research questions and aims with an advocacy stance, which means that they were phrased in such a way that highlighted power differentials and/or authors’ ambition to address them. The authors eliciting the views and experiences of underrepresented SLPs often argued how these were fundamental perspectives to inform inclusive practice. For example, Hudnall (Citation2022, p. 631) documented the knowledge and lived experiences of SLPs from cross-cultural perspectives “to meaningfully critique and evolve practice standards” and Hudock et al. (Citation2018, p. 34) sought to better understand the experiences of speech-language pathology students who stutter to inform supervisors about “potential challenges” and “beneficial opportunities.” Other studies aimed to formulate recommendations for the recruitment and retention of underrepresented SLPs (Fuse, Citation2018; Keshishian & McGarr, Citation2012; Litosseliti & Leadbeater, Citation2013), or to improve the quality and effectiveness of service delivery for underserved clients (Nieva et al., Citation2020; Núñez et al., Citation2021; Santhanam et al., Citation2019).

Did the literature review include discussions of diversity and oppression?

Fourteen papers (70%) included discussions of diversity and oppression in their literature. Many authors acknowledged the lack of ethnic or linguistic diversity in the profession without articulating issues of oppression (D'Souza et al., Citation2012; Epstein, Citation2012; Keshishian & McGarr, Citation2012; Lowell et al., Citation2018; Santhanam et al., Citation2019). Issues of oppression were more often discussed about the clients’ perspective than the SLPs’, such as the risk for clients with ethnic or linguistically diverse backgrounds to lack access to quality services (Narayanan & Ramsdell, Citation2022; Nieva et al., Citation2020; Wofford & Morrow-Odom, Citation2016), or systemic barriers when seeking disability support for children in schools (Westby, Citation2021). Papers covering the lack of gender diversity in the profession engaged with the societal expectations and stereotypes of professionals, and their impact on male SLPs (Azios & Bellon-Harn, Citation2021; Du Plessis, Citation2018; Litosseliti & Leadbeater, Citation2013). A few papers discussed issues of oppression in speech-language pathology education for minoritised students, such as stereotypic teaching strategies on cultural and linguistic diversity (Hudnall, Citation2022), or biases against minoritised students within institutions (Fuse, Citation2018; Mahendra & Kashinath, Citation2022).

Did authors discuss appropriate labelling of the participants?

Only one paper (5%) demonstrated appropriate labelling of the participants. Mahendra and Kashinath (Citation2022, p. 528) reported that

[g]iven the complexity of race, ethnicity, and cultural identity and their intersectionality, we chose not to profile students or make assumptions about their cultural background. Instead, we explained the goals and requirements of this training program as intended to support diversifying the speech-language pathology pipeline, followed by an open application process inviting interested applicants to self-report demographic data and provide first-person narratives about why they considered themselves underrepresented in speech-language pathology.

Did data collection and outcomes benefit the community?

Seven papers (35%) demonstrated the benefits of data collection and outcomes to the community. Although the simple act to collect data and publish the findings is inherently valuable to the community, few papers demonstrated more direct transformative benefits of their research. All interventions reported a positive impact to the community of underrepresented SLPs, but their sustainability or long-term impact was often unclear. Mahendra and Kashinath (Citation2022) proposed the most transformative design for the benefit of speech-language pathology students from minoritised backgrounds by giving a stipend to complete the program that was personalised to the students’ interests and career goals. The bilingual SLPs in Núñez et al. (Citation2021) valued gaining access to clinical and research resources during the study. Parveen and Santhanam (Citation2021) and Santhanam et al. (Citation2019) reported financial incentives for participants.

Did the participants initiate the research, and/or were they actively engaged in the project?

In no study did the participants directly initiate the research, but the active engagement of participants was demonstrated in five studies (25%). Two studies sought the participants’ input to tailor the interventions’ content to their needs (Mahendra & Kashinath, Citation2022; Núñez et al., Citation2021). Two studies used member checks to validate the findings with the participants (Hudock et al., Citation2018; Núñez et al., Citation2021), and one built the participants’ capacity to disseminate findings (Mahendra & Kashinath, Citation2022).

Did the results elucidate power relationships?

Fifteen papers (75%) elucidated power relationships. Most authors did so by providing evidence on the lack of consideration, low resources, or oppressive systems that negatively impact the quality of care for clients with ethnic and linguistic minority backgrounds (Hudnall, Citation2022; Lowell et al., Citation2018; Narayanan & Ramsdell, Citation2022; Parveen & Santhanam, Citation2021). Others reported inequities and discrimination within the speech-language pathology workforce, such as issues of colour blindness (Ebert, Citation2013), higher workloads (Núñez et al., Citation2021), or structural gender inequalities influencing career progression (Litosseliti & Leadbeater, Citation2013). Few authors acknowledged issues of power within the research process itself. Azios and Bellon-Harn (Citation2021) described how gender differences between researchers and participants may have influenced their engagement. Hudnall (Citation2022) and Núñez et al. (Citation2021) provided authors’ positionality statements, which are helpful to understand their interests and potential biases. Finally, Hudnall (Citation2022) described an interview technique to manage power differentials: They used dialogic interviews to allow for more balanced interactions between the researcher and the participant as it was “necessary to understand power and neutrality as co-constructions” (p. 634).

Did the authors facilitate social change?

Eighteen papers (90%) indicated how authors worked towards social change. Most authors did so by providing evidence-based recommendations. Some recommendations were directly relevant to supporting underrepresented SLPs thrive in the profession, such as by providing advice for clinical supervisors who work with speech-language pathology students who stutter (Hudock et al., Citation2018) or highlighting the importance of male role models to other men in the profession (Litosseliti & Leadbeater, Citation2013). Others provided recommendations to better support underserved clients, such as seeking clinical materials that are responsive to clients’ cultures (Harris & Owen Van Horne, Citation2021) or encouraging clinical training for working with clients with linguistic and ethnic minority backgrounds (Parveen & Santhanam, Citation2021; Santhanam et al., Citation2019). It was often unclear if or how the authors intended to plan and see through the implementation of these recommendations.

Did the authors explicitly state use of a transformative framework?

Only two papers (10%) explicitly stated the use of a transformative framework. Mahendra and Kashinath (Citation2022) implemented a yearlong mentoring program that facilitated equitable access to education and career opportunities for underrepresented speech-language pathology students. Núñez et al. (Citation2021) enquired about the areas of professional development needs of bilingual SLPs, and used this information to facilitate a community of practice for bilingual SLPs to empower them in their practices. Other papers, especially interventions, showed high potential to facilitate social change but a transformative framework was not centred in the authors’ narrative (Epstein, Citation2012; Wofford & Morrow-Odom, Citation2016).

Discussion

This scoping review has unpacked the characteristics of research studies that included underrepresented SLP participants in the past decade. Grounding this review in the transformative research paradigm has enabled us to revisit this specific set of studies through a new lens, one which centres the empowerment and agency of underrepresented SLPs as participants in research (Mertens, Citation2017, Citation2021). We now discuss five key contributions from our findings and their implications for future research.

Firstly, the transformative research paradigm made us rethink the how and why we do research, notably by reconsidering the roles of researchers and participants as agents of social change (Mertens, Citation2021). The checklist developed by Sweetman et al. (Citation2010) proved to be a tangible tool to introduce researchers and SLPs to the tenets of this paradigm. It can be used to inform study design, critically analyse or report research, and guide reflexivity on theoretical frameworks, assumptions, and levels of community engagement to determine the extent to which studies promote inclusion and challenge the status quo. In the present review, this checklist enabled us to identify good practices of transformative research, independently of whether the authors were positioned in this paradigm. For instance, most authors clearly identified an issue in a community of concern (Mahendra & Kashinath, Citation2022); facilitated social change, especially through the production of evidence-based recommendations (Litosseliti & Leadbeater, Citation2013); and elucidated power relationships in the results of their studies (Ebert, Citation2013; Hudnall, Citation2022). These good practices can inspire future research and be complemented by others to enhance their transformative potential. We particularly encourage speech-language pathology researchers to co-design and facilitate the active engagement of underrepresented SLPs at different stages of the research cycle (Page et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, by elaborating and reporting plans to implement their suggested recommendations, researchers can stimulate actions and drive social change.

Secondly, the included studies provided a valuable platform to improve visibility to the unique perspectives, experiences, and practices of underrepresented SLPs. Mapping the studies’ findings onto the CHAT-ICF framework allowed us to capture this evidence in a novel way, and to illustrate the unique positionality of underrepresented SLPs to transform practice with consideration to how elements of their activity systems (CHAT) resonated with the experiences of their clients (ICF). Using reflexivity, we noted cross-cutting trends relevant to many groups of underrepresented SLPs. This information can guide clinicians and researchers towards more inclusive practices. For example, the importance of intersectionality and contextual factors that regulate the experiences of underrepresented SLPs emphasised the need to tailor person-centred support, interventions, and recommendations (Mahendra & Kashinath, Citation2022; Núñez et al., Citation2021). We also collected evidence on the societal and systemic barriers that can hinder their sense of agency and empowerment, especially through unconscious biases, stigma, and discrimination (Ebert, Citation2013). To avoid undue burden on minority groups, awareness and meaningful training should be provided with a focus on cultural humility (Lekas et al., Citation2020) and decoloniality (Pillay et al., Citation2023), and accountability mechanisms put in place to distribute responsibility towards issues of diversity across the speech-language pathology workforce and to support positive reinforcement by the leadership (Weisinger et al., Citation2021). Researchers can also contribute by investigating these issues or integrating these considerations in their study designs (Gopal et al., Citation2021).

Thirdly, this review shed light upon the voices that are currently missing in research and that should be of particular focus in future research. It is encouraging to note the number of studies on bilingual (Santhanam et al., Citation2019) and male SLPs (Du Plessis, Citation2018), but other groups of underrepresented SLPs received considerably less attention or were altogether absent (such as LGBTQ+ SLPs, Indigenous SLPs, or SLPs with disabilities with a range of other underlying conditions or neurodivergences). Furthermore, our review confirmed the lack of geographic diversity in speech-language pathology research, which was largely contextualised in the USA and other high-income English-speaking countries (Abrahams et al., Citation2022). As a research community, it is essential for us to reflect on whose voices are amplified and centred and whose are attenuated and marginalised, and to do so at different scales (locally, nationally, and globally). Creating safe spaces to listen to, acknowledge, discuss, and respond to the concerns articulated by diverse demographics, especially if done with the principles of the transformative research paradigm, can shape the evidence base that will inform the future of our profession, instigate innovation, and instil equity (Mertens, Citation2021).

Fourthly, it was encouraging to see the use of various research designs and mixed methods in the studies that have been included, especially since a variety of tools is needed to tackle complex issues of social justice (Mertens, Citation2007). The use of Indigenous or co-produced conceptual frameworks and methods can meaningfully contribute to the empowerment of minority groups by enabling the knowledge creation around concepts that matter to them, and reflect and respect their worldview (Armstrong et al., Citation2023; Purdy, Citation2020). For example, the Kaupapa Māori research approach can promote Māori culture and knowledge in speech-language pathology research in Aotearoa, New Zealand (Brewer, Citation2016; Brewer et al., Citation2014; McLellan et al., Citation2014; Meechan & Brewer, Citation2022). Researchers are encouraged to be guided by the pressing issues articulated by minority members of our community to formulate the most relevant research questions and identify the best suited methods. There is increasing recognition about the value of qualitative research methods to better understand and respond to the needs of the speech-language pathology community (Hersh et al., Citation2022), and to unpack the experiences and practices of underrepresented SLPs (Gréaux, Gibson, et al., Citation2024; Gréaux, Katsos, et al., Citation2023). Quantitative researchers also have a critical responsibility to be aware of the power differentials that can be perpetuated within their methods. This is particularly relevant as we noticed that the authors using quantitative research designs tended to show less engagement with their theoretical lenses. For example, consulting underrepresented SLPs can help to identify the factors and variables that are important to them, to caution against assumptions made about them and their relations, or to formulate hypotheses that align with their priorities, so that stereotypes and prejudice are not reinforced (Walter & Andersen, Citation2013).

Lastly, our review showed that research is yet to catch up with the current priorities on issues of diversity, inclusion, and equity that have gained momentum in the field of speech-language pathology in recent years. Indeed, only 20 studies were identified in our review, and the rate of publication has not significantly changed over the past decade. We encourage research funders, professional bodies, journal editors, and individual researchers to consider ways to facilitate research by, with, and for underrepresented groups in the profession. For example, those in influential roles could implement accountability mechanisms (such as reporting guidelines or publications quota) to accelerate the amplification of underrepresented SLPs’ voices. Speech-language pathology university programs also need to consider how they can strengthen their processes and policies to promote the recruitment, retention, and well-being of underrepresented speech-language pathology students.

Limitations

It is possible that relevant studies may have been missed if the inclusion of underrepresented speech-language pathology participants was not obvious from the articles’ title and abstract. Our search strategy could have been expanded, notably by specifying certain Indigenous groups such as Māori, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, and First Nations Peoples. Furthermore, the language limitations may have meant that we could not access certain studies. We recognise that the narrative used in this review contributes to (and reinforces) the contemporary conceptualisations of minority, diversity, inclusion, and equity that have been largely shaped by scholars in Western contexts with privileged roles in the speech-language pathology profession and academia. This can be partly explained as an artefact of the review methods, with our contribution reflecting and perpetuating the narrative used in the included papers, but nonetheless important to call out and challenge in future research. Finally, the scope of this review was focused on studies with underrepresented SLPs as research participants only, and excluded conceptual or methods papers and did not account for the profile of researchers. This means that this scoping review provides an overview of only a portion of the current speech-language pathology research efforts aiming to advance inclusion, diversity, and equity.

Future research

Researchers wanting to address issues of social justice and promote equity are encouraged to familiarise themselves and ground their projects in the transformative research paradigm (Mertens, Citation2017). The use of participatory and mixed methods, as well as co-design approaches, are equally important to instigate social change (Mertens, Citation2007; Sweetman et al., Citation2010). We need more research centring the experiences and practices of underrepresented SLPs (Gréaux, Gibson, et al., Citation2024; Gréaux, Katsos, et al., Citation2023) and evaluating interventions that are tailored to their needs, as was done in Mahendra and Kashinath (Citation2022) and Núñez et al. (Citation2021). Finally, it would also be timely to elaborate a research agenda to identify priorities and articulate a common vision to drive inclusion and equity for minoritised communities in the speech-language pathology profession, considering the perspectives of clinicians and the communities that they serve. To catalyse change, this agenda should include diverse voices (including a range of stakeholders from different contexts and with diverse backgrounds), be endorsed and supported by professional and research authorities, and facilitate the coordination of research projects and distribution of resources within and between countries.

Conclusion

This review calls for a shift in how and why research is conducted when including underrepresented SLP participants. Through the lens of the transformative research paradigm, we can rethink the broader aim of research and the role of researchers and participants as they engage in a power-full and value-able platform towards social change. Research promoting the inclusion and empowerment of diverse voices, especially those that have traditionally been marginalised, can create positive change to stimulate equity in the speech-language pathology profession, with cascading benefits to service provision and society.

Appendix 2_PsycInfo (via Ebsco) search strategy.docx

Download MS Word (18.1 KB)Appendix_1_PRISMA Extended checklist for scoping reviews_R2.docx

Download MS Word (23.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all SLPs, identifying as minority or majority in their professional community, who contributed valuable feedback and suggestions to inform the protocol of this scoping review. The authors also wish to thank Isla Kuhn and Eleanor Barker, librarians at the University of Cambridge Medical School, who provided feedback on the protocol, and support with the development and running of the search strategy.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 OSF link: https://osf.io/nzwx6/.

2 The levels of income indicated in this paper follow the classification produced by the World Bank, which is accessible on this webpage: https://data.worldbank.org/country

References

- Abrahams, K., Kathard, H., Harty, M., & Pillay, M. (2019). Inequity and the professionalisation of speech-language pathology. Professions and Professionalism, 9(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.3285

- Abrahams, K., Mallick, R., Hohlfeld, A., Suliaman, T., & Kathard, H. (2022). Emerging professional practices focusing on reducing inequity in speech-language therapy and audiology: A scoping review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-01953-0

- Allen, H., Callender, C., & Thompson, D. (2023). Promoting health equity: Identifying parent and child reactions to a culturally-grounded obesity prevention program specifically designed for Black girls using community-engaged research. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 10(3), 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030417

- Allison-Burbank, J. D., & Reid, T. (2023). Prioritizing connectedness and equity in speech-language services for American Indian and Alaska Native children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 54(2), 368–374. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_LSHSS-22-00101

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Armstrong, E., McAllister, M., Coffin, J., Robinson, M., Thompson, S., Katzenellenbogen, J., Colegate, K., Papertalk, L., Hersh, D., Ciccone, N., & White, J. (2023). Communication services for First Nations peoples after stroke and traumatic brain injury: Alignment of Sustainable Development Goals 3, 16 and 17. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25(1), 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2145356

- Attrill, S., Davenport, R., & Brebner, C. (2022). Professional socialisation and professional fit: Theoretical approaches to address student learning and teaching in speech-language pathology. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(5), 472–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2021.2014965

- Azios, J. H., & Bellon-Harn, M. (2021). Providing a perspective that’s a little bit different": Academic and professional experiences of male speech-language pathologists. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2020.1722237

- Azul, D., & Zimman, L. (2022). Innovation in speech-language pathology research and writing: Transdisciplinary theoretical and ethical perspectives on cultural responsiveness. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(5), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2084160

- Boyd, S., & Hewlett, N. (2001). The gender imbalance among speech and language therapists and students. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 36(S1), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.3109/13682820109177878

- Brewer, K. M. (2016). The complexities of designing therapy for Māori living with stroke-related communication disorders. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 129(1435), 75–82.

- Brewer, K. M., Harwood, M. L. N., McCann, C. M., Crengle, S. M., & Worrall, L. E. (2014). The use of interpretive description within Kaupapa Māori research. Qualitative Health Research, 24(9), 1287–1297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314546002

- Cunningham, B. J., Washington, K. N., Binns, A., Rolfe, K., Robertson, B., & Rosenbaum, P. (2017). Current methods of evaluating speech-language outcomes for preschoolers with communication disorders: A scoping review using the ICF-CY. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 60(2), 447–464. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_JSLHR-L-15-0329

- D'Souza, C., Bird, E. K.-R., & Deacon, H. (2012). Survey of Canadian speech-language pathology service delivery to linguistically diverse clients. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology/Revue Canadienne D’Orthophonie et D’Audiologie, 36(1), 18–39.

- Demeke, J., Ramos, S. R., McFadden, S. M., Dada, D., Nguemo Djiometio, J., Vlahov, D., Wilton, L., Wang, M., & Nelson, L. E. (2023). Strategies that promote equity in COVID-19 vaccine uptake for Latinx communities: A review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 10(3), 1349–1357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01320-8

- Du Plessis, S. (2018). Male students’ perceptions about gender imbalances in a speech-language pathology and audiology training programme of a South African institution of higher education. The South African Journal of Communication Disorders = Die Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Kommunikasieafwykings, 65(1), e1–e9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajcd.v65i1.570

- Ebert, K. D. (2013). Perceptions of racial privilege in prospective speech-language pathologists and audiologists. Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Populations, 20(2), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1044/cds20.2.60

- Engeström, Y. (2014). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139814744

- Epstein, L. (2012). Dimensions of building clinical training teams in the Spanish-bilingual preschool classroom. Perspectives on Administration and Supervision, 22(1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1044/aas22.1.28

- Faithfull, E., Brewer, K., & Hand, L. (2020). The experiences of Whānau and Kaiako with speech-language therapy in Kaupapa Māori education. MAI Journal: A New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship, 9(3), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.20507/MAIJournal.2020.9.3.3

- Fuse, A. (2018). Needs of students seeking careers in communication sciences and disorders and barriers to their success. Journal of Communication Disorders, 72, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2018.02.003

- Ganek, H. (2021, September 7). Colonialism in speech-language pathology: Moving forward. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmjgh/2021/09/07/colonialism-in-speech-language-pathology-moving-forward/

- Government of the United Kingdom. (n.d). Types of discrimination (‘protected characteristics’). Retrieved May 15, 2022, from https://www.gov.uk/discrimination-your-rights

- Gopal, D. P., Chetty, U., O'Donnell, P., Gajria, C., & Blackadder-Weinstein, J. (2021). Implicit bias in healthcare: Clinical practice, research and decision making. Future Healthcare Journal, 8(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.7861/fhj.2020-0233

- Gréaux, M., Gibson, J. L., & Katsos, N. (2024). `It’s not just linguistically, there’s much more going on’: The experiences and practices of bilingual paediatric speech and language therapists in the UK. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.13027

- Gréaux, M., Katsos, K., & Gibson, J. L. (2023). “I’m in a unique position to make a difference”: The experiences and practices of autistic speech and language therapists. Preprint. 1–33. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/6wj2p

- Gréaux, M., Moro, M. F., Kamenov, K., Russell, A., Barrett, D., & Cieza, A. (2023). Health equity for persons with disabilities: A global scoping review on barriers and interventions in healthcare services. International Journal for Equity in Health, 22(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-023-02035-w

- Guiberson, M., & Vigil, D. (2021). Speech-language pathology graduate admissions: Implications to diversify the workforce. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 42(3), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740120961049

- Guyan, K. (2017). Reflexivity: Positioning yourself in equality and diversity research. Research and Data Briefing. Equality Challenge Unit. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/reflexivity-positioning-yourself-equality-and-diversity-research

- Harfield, S., Pearson, O., Morey, K., Kite, E., Canuto, K., Glover, K., Gomersall, J. S., Carter, D., Davy, C., Aromataris, E., & Braunack-Mayer, A. (2020). Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), 79–79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-00959-3

- Harris, S., & Owen Van Horne, A. (2021). Speech-language pathologist’s race, but not caseload composition, is related to self-report of selection of diverse books. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 6(5), 1263–1272. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_PERSP-20-00280

- Hermosillo, D., Cygan, H. R., Lemke, S., McIntosh, E., & Vail, M. (2022). Achieving health equity for LGBTQ+ adolescents. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 53(8), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20220706-05

- Hernandez-Salinas, C., Marsiglia, F. F., Oh, H., Campos, A. P., & De La Rosa, K. (2023). Community health workers as puentes/bridges to increase COVID-19 health equity in Latinx communities of the Southwest U.S. Journal of Community Health, 48(3), 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01182-5

- Hersh, D., Azul, D., Carroll, C., Lyons, R., Mc Menamin, R., & Skeat, J. (2022). New perspectives, theory, method, and practice: Qualitative research and innovation in speech-language pathology. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(5), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2029942

- Hopf, S. C., Crowe, K., Verdon, S., Blake, H. L., & McLeod, S. (2021). Advancing workplace diversity through the culturally responsive teamwork framework. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(5), 1949–1961. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-20-00380

- Horton, R. (2021). Critical perspectives on social justice in speech-language pathology. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7134-7

- Hudnall, M. (2022). Self-reported perspectives on cultural competence education in speech-language pathology. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(2), 631–638. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-20-00338

- Hudock, D., Yates, C., & Vereen, L. G. (2018). A Mixed-Methods observational pilot study of student clinicians who stutter. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 3(4), 30–57. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp3.SIG4.30

- Hyter, Y. (2021). The power of words: A preliminary critical analysis of concepts used in speech, language, and hearing sciences. In R. Horton (Ed.), Critical perspectives on social justice in speech-language pathology (pp. 60–83). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7134-7

- Jamieson, L. M., Paradies, Y. C., Eades, S., Chong, A., Maple‐Brown, L., Morris, P., Bailie, R., Cass, A., Roberts‐Thomson, K., & Brown, A. (2012). Ten principles relevant to health research among Indigenous Australian populations. The Medical Journal of Australia, 197(1), 16–18. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja11.11642

- Keshishian, F., & McGarr, N. S. (2012). Motivating factors influencing choice of major in undergraduates in communication sciences and disorders. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(2), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.645250

- Khamis-Dakwar, R., & Randazzo, M. (2021). Deconstructing the three pillars of evidence-based practice to facilitate social justice work in speech language and hearing sciences. In R. Horton (Ed.), Critical perspectives on social justice in speech-language pathology (pp. 130–150). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7134-7.ch007

- Laycock, A., Walker, D., Harrison, N., & Brands, J. (2011). Researching indigenous health: A practical guide for researchers. Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute.

- Lekas, H.-M., Pahl, K., & Fuller Lewis, C. (2020). Rethinking cultural competence: Shifting to cultural humility. Health Services Insights, 13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920970580

- Litosseliti, L., & Leadbeater, C. (2013). Speech and language therapy/pathology: Perspectives on a gendered profession. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(1), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00188.x

- Lowell, S. Y., Vigil, D. C., Abdelaziz, M., Edmonds, K., Goel-Sakhalkar, P., Guiberson, M., Fleming Hamilton, A., Hung, P.-F., Lee-Wilkerson, D., Miller, C., Rivera Perez, J. F., Ramkissoon, I., & Scott, D. (2018). Pathways to cultural competence: Diversity backgrounds and their influence on career path and clinical care. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 3(14), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp3.SIG14.30

- Ma, E. P. M. (2018). The use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in clinical research, practice, and education: A Hong Kong perspective. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 3(17), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp3.SIG17.86

- Mahendra, N., & Kashinath, S. (2022). Mentoring underrepresented students in speech-language pathology: Effects of didactic training, leadership development, and research engagement. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(2), 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-21-00018

- McLellan, K. M., McCann, C. M., Worrall, L. E., & Harwood, M. L. N. (2014). “For Māori, language is precious. And without it we are a bit lost”: Māori experiences of aphasia. Aphasiology, 28(4), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.845740

- McLeod, S., & Threats, T. T. (2008). The ICF-CY and children with communication disabilities. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 10(1-2), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549500701834690

- McNeilly, L. G. (2018). Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework to achieve interprofessional functional outcomes for young children: A Speech-language pathology perspective. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 65(1), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2017.08.025

- Meechan, R. J. H., & Brewer, K. M. (2022). Māori speech-language therapy research in Aotearoa New Zealand: A scoping review. Speech, Language and Hearing, 25(3), 338–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2021.1954836

- Mertens, D. M. (2003). Mixed methods and the politics of human research: The transformative-emancipatory perspective. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (pp. 135–164). Sage.

- Mertens, D. M. (2007). Transformative paradigm: Mixed methods and social justice. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(3), 212–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689807302811

- Mertens, D. M. (2017). Transformative research: Personal and societal. International Journal for Transformative Research, 4(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijtr-2017-0001

- Mertens, D. M. (2021). Transformative research methods to increase social impact for vulnerable groups and cultural minorities. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211051563

- Nair, V. K., Farah, W., & Cushing, I. (2023). A critical analysis of standardized testing in speech and language therapy. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 54(3), 781–793. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_lshss-22-00141

- Nancarrow, S., McGill, N., Baldac, S., Lewis, T., Moran, A., Harris, N., Johnson, T., & Mulcair, G. (2023). Diversity in the Australian speech-language pathology workforce: Addressing Sustainable Development Goals 3, 4, 8, and 10. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25(1), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2023.2165149

- Narayanan, T. L., & Ramsdell, H. L. (2022). Self-reported confidence and knowledge-based differences between multilingual and monolingual speech-language pathologists when serving culturally and linguistically diverse populations. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 7(1), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_PERSP-21-00169

- Newkirk-Turner, B. L., & Morris, L. R. (2021). An unequal partnership: Communication sciences and disorders, Black children, and the Black speech community. In R. Horton (Ed.), Critical perspectives on social justice in speech-language pathology (pp. 180–196). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7134-7.ch009

- Nieva, S., Aguilar-Mediavilla, E., Rodríguez, L., & Conboy, B. T. (2020). Competencias profesionales para el trabajo con población multilingüe y multicultural en España: Creencias, prácticas y necesidades de los/las logopedas/Professional competencies for working with multilingual and multicultural populations in Spain: Speech-language therapists’ beliefs, practices and needs. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y Audiología, 40(4), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rlfa.2020.09.002

- Núñez, G., Buren, M., Diaz-Vazquez, L., & Bailey, T. (2021). Bilingual supports for clinicians: Where do we go from here? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52(4), 993–1006. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_LSHSS-20-00176

- Page, G. G., Wise, R. M., Lindenfeld, L., Moug, P., Hodgson, A., Wyborn, C., & Fazey, I. (2016). Co-designing transformation research: Lessons learned from research on deliberate practices for transformation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 20, 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.09.001

- Parveen, S., & Santhanam, S. p. (2021). Speech-language pathologists’ perceived competence in working with culturally and linguistically diverse clients in the United States. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 42(3), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740120915205