Abstract

Purpose

Living alone is increasing and associated with health and social risks. Aphasia compounds these risks but there is little research on how living alone interacts with aphasia. This study is a preliminary exploration of this issue.

Method

Five people with aphasia who lived alone participated in two supported semi-structured interviews, with the second interview including sharing an artefact that held significance for living alone with aphasia. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed through reflexive thematic analysis.

Result

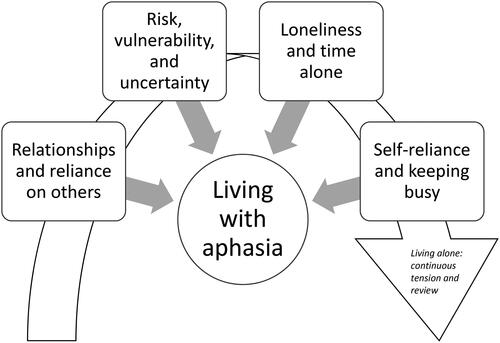

Four themes encompassed meaning-making about living alone with aphasia: relationships and reliance on others; risk, vulnerability, and uncertainty; loneliness and time alone; self-reliance and the need to keep busy. Participants had to continuously manage and renegotiate daily challenges around living alone with aphasia.

Conclusion

Living alone increases the risk of loneliness. For people with aphasia, the buffer against loneliness provided by social connection and meaningful activity may be more difficult to achieve because of communication challenges. While experiences vary, reliance on others, managing practical and administrative tasks, and negotiating risks are all important issues when alone. The intersection of living alone, loneliness, and living with aphasia needs more research, and more explicit clinical focus when discussing and planning intervention and support.

Introduction

The number of Australians living alone has increased markedly in recent decades, consistent with global trends of rising lone-person households (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016; United Nations, Citation2019). People who live alone make up approximately a quarter of Australian households, with the number of Australians projected to live alone by 2041 set to increase by up to 53% (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016; De Vaus & Qu, Citation2015). Contributing factors include Australia’s ageing population, increased life expectancy, declining birth rate, flexible aged-care home packages, and societal shifts on marriage, divorce, and family arrangements (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017; Department of Health, Citation2021; De Vaus & Qu, Citation2015). The relationship between an individual’s living arrangement and physical and mental health (Evans et al., Citation2019; Jensen et al., Citation2019; Smith & Victor, Citation2019; Valtorta et al., Citation2016), quality of life (Henning-Smith, Citation2016), and longevity (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2015) is well-documented in medical, allied health, and gerontological literature. Research indicates that people who live alone are at higher risk of adverse health and social outcomes such as social isolation, loneliness, and depression compared to those living with others (Snell, Citation2017; Victor et al., Citation2000).

Living alone is associated with detrimental health outcomes including increased risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, stroke, cognitive decline, depression, and premature mortality (Desai et al., Citation2020; Evans et al., Citation2019; Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2015; Jensen et al., Citation2019; Pantell et al., Citation2013; Smith & Victor, Citation2019; Valtorta et al., Citation2016). Individuals who live alone have poorer health outcomes following hospital discharge, including higher readmission rates, higher rates of nursing home admission, and increased use of outpatient services (Taube et al., Citation2016; Murphy et al., Citation2008) although perceived neighbourhood cohesion appears to be a protective factor (Jiang et al., Citation2023). The impact of living alone on mental health and psychosocial wellbeing is well researched, with mounting focus due to the COVID-19 pandemic and enforced periods of lockdown and social distancing (Smith & Lim, Citation2020).

The relationship between living alone, loneliness, and aloneness is complex. Although the terms are often used interchangeably, each has distinct features. Living alone is simply being the sole occupant of a household, an objective measure of an individual’s living arrangement (Victor et al., Citation2000). Aloneness is an objective measure of time spent alone in the absence of social contact (Pierce et al., Citation2003). Time alone or solitude may be a positive experience, enhancing personal reflection, creativity, or learning (Stanley et al., Citation2017). In contrast, excessive periods of time spent alone has been associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2015). Loneliness is subjective, an emotional response when the quality or quantity of social relationships is less than desired (Smith & Lim, Citation2020). Loneliness is theorised to be an evolutionary response for humans’ innate need for social connection (Cacioppo et al., Citation2014). It is important to note that although these concepts may be associated, they are often not significantly correlated in research (Coyle & Dugan, Citation2012; Perissinotto & Covinsky, Citation2014). Similarly, the circumstances in which an individual lives alone, personal preferences, and life experience determine whether the experience is viewed as positive or negative (Dale et al., Citation2012).

People who live alone with chronic health conditions and disability are particularly vulnerable to negative physical, psychological, and social health outcomes (Haslbeck et al., Citation2012). For example, Reeves et al. (Citation2014) explored the associations between living alone and acute stroke outcomes and found that people who lived alone took longer to reach hospital, received less thrombolytic therapy, and were less likely to return home. Stroke is a leading cause of mortality and disability and in Australia, in 2020, nearly 40 000 people experienced a stroke event (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2023). Approximately 30% of all stroke survivors will experience aphasia (Flowers et al., Citation2016) impacting to various degrees a person’s ability to speak, read, write, and/or understand language, while not affecting intelligence (Brady et al., Citation2016). Aphasia is known to negatively impact quality of life, with many people facing various day-to-day challenges involving communication (Harmon, Citation2020). While there is a large body of research on the lived experience of living alone amongst various populations (Bergland et al., Citation2016; Duane et al., Citation2013; Odzakovic et al., Citation2019; Segraves, Citation2004; Taube et al., Citation2016), research that specifically examines the experiences of people with aphasia who live alone is currently lacking (Sherratt, Citation2024). People with aphasia who live alone have been included in research studies more generally (for example, Manning et al., Citation2021; Worrall et al., Citation2011), however their experiences have not been explored in any depth. Moreover, recent timely consideration of the social determinants of health (O'Halloran et al., Citation2023) considered a range of issues potentially compounding life with aphasia (gender, education, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and social support) but did not include living situation. There is limited knowledge on how the situation of living alone impacts on life participation, how it shapes what people do or how they feel, and how aphasia may further impact everyday life.

The impact of aphasia on social networks from the acute through to chronic stages is already well documented (Cruice et al., Citation2006; Hilari & Northcott, Citation2017; Manning et al., Citation2021; Vickers, Citation2010). People with aphasia are reported to have fewer social contacts and participate in fewer social activities than their age-matched peers (Cruice et al., Citation2006). Communication breakdown, the stigma of disability, and adapting to life post-stroke all contribute to reduced social connections (Brown et al., Citation2013; Dalemans et al., Citation2010). Psychological distress and depression in people with aphasia are common (Hilari et al., Citation2010; Laures-Gore et al., Citation2020) with the incidence of depression at 12 months post-onset of aphasia documented at 62% (Kauhanen et al., Citation2000). Social factors, such as loneliness and reduced social networks, have been identified as the greatest predictors of distress for people with aphasia in the acute and chronic stages of recovery (Hilari et al., Citation2010). Studies identifying the key aspects of living successfully with aphasia emphasise the importance of meaningful social relationships and social participation (Brown et al., Citation2010). The benefits of aphasia group therapy and peer support groups in enhancing communication skills, providing social and emotional support, and facilitating recovery are well recognised (Azios et al., Citation2022; Hilari et al., Citation2019; Lanyon et al., Citation2018a; Vickers, Citation2010). Interestingly, recent longitudinal qualitative research (Ford et al., Citation2024) found that in the first year following onset of aphasia, people moved from an initial reliance on their inner circle of relationships, often a spouse or child living at home, to slowly venture beyond this to reconnect with broader networks; however, “early attempts at reconnection were often facilitated by inner circle relationships, particularly spouses” (p. 15). Of the seven participants in te study by Ford et al., the two who lived alone were both found to be disadvantaged socially: “without a support person to contact close others, solve practical issues when going out and even support conversations, people with aphasia faced more barriers and appeared to be at higher risk of isolation from friends” (Ford et al., Citation2024, p. 15).

Considering the greater risk of adverse health, psychological, and social outcomes for people who live alone (Desai et al., Citation2020; Evans et al., Citation2019; Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2015; Jensen et al., Citation2019; Mahoney et al., Citation2000); the increasing number of single-person households; and the recognised impact of aphasia on social networks, it is important to explore the intersection between living alone and aphasia. Therefore, this project aimed to start the process by exploring the experience of living alone with a sample of people with aphasia.

Method

This study used supported semi-structured, in-depth interviews (Lanyon et al., Citation2019); analysis was inductive and data-driven, and analysed for themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Considering the value of visual information when communicating with people with aphasia, data collection included a request for an artefact as a way to deepen the understanding of what might be important for people or to help them represent their feelings about living alone (Guillemin, Citation2004). The inclusion of participant-generated artefacts has also been used previously by Brown et al. (Citation2010) in their study of living successfully for people with aphasia. Their participants generated photographs of objects, people, places, and other items that represented their perspective of living successfully with aphasia. The use of artefacts in qualitative research provides an insight into a given phenomenon, and analysis of meanings about loneliness related to the artefact enhances the credibility and rigour through triangulation of data (Tong et al., Citation2007).

This study was part of an honours degree carried out in 2021. The second author was a student, who completed data collection and preliminary analysis under the supervision of the other authors of this paper: principal supervisor, an experienced qualitative researcher and aphasia therapist (first author); speech-language pathology clinician and academic (third author); and occupational therapy academic (fourth author), who has expertise in loneliness. The second author did not have a longstanding relationship with the participants prior to the study and she had participated in a workshop on supported qualitative interviewing run by the first author as part of her research preparation. Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants from the clinic attached to the university. Eligibility criteria for the study included people with chronic aphasia (of either stroke or progressive aetiology, at least 6 months post-onset); currently living alone; and able to attend and participate in two semi-structured interviews, either face-to-face or online (an option as a COVID-19 precaution). Clients at the clinic who met the eligibility criteria and had previously provided consent for their data to be used in research projects and/or to be contacted about other activities in the clinic were identified as potential participants. The third author, who also worked at the clinic, accessed consenting clients’ contact details through a secure database, in accordance with the university’s data management policy for the clinic. Five participants (two male, three female) were recruited for the study. Participant characteristics can be seen in .

Table I. Demographic information.

A measure of aphasia severity was taken from the clinic notes for each participant. This included the Aphasia Quotient (AQ) from the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB-R; Kertesz, Citation2007) for four of the participants and the Brisbane Evidence-based Language Test for one participant. Severity level did not preclude participation in the study, with supported conversation techniques (e.g. multi-modal communication) used to support participation throughout interviews (Kagan et al., Citation2001).

Ethics

This project was approved by the Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee (REMS: 2021-02474). Information and consent forms were presented in an aphasia-friendly format and supported communication techniques (Kagan et al., Citation2001) were used to ensure that participants were fully informed prior to written consent.

Data collection

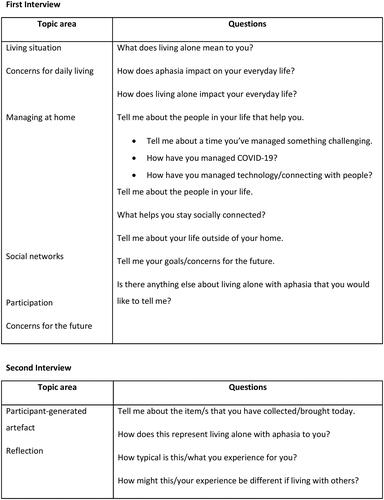

Data collection occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, but the border of Western Australia was closed to the rest of the country at this time so physical distancing was less restrictive than in other places. Participants were interviewed twice, approximately 1 week apart, through semi-structured, in-depth interviews. Interviews were conducted face-to-face in a private room at the university clinic, except for one participant who requested to be interviewed online via Zoom. Interviews were conducted by the second author. The interviews included some discussion beyond the topic guide. The times for the first interviews averaged 55 minutes (range 40–76 minutes) and for the second interviews averaged 30 minutes (range 18–40 minutes). Interviews were audio and video recorded to capture non-verbal communication and communicative attempts. Audio and video recordings were uploaded and stored on a secure drive, in accordance with the university’s data management policy, then deleted from the student researcher’s personal recording equipment. The first interview explored issues related to living alone with aphasia, using a topic guide to form the basis of questions (see ). The topic guide consisted of broad, open-ended questions with probes and prompts to elicit rich, descriptive accounts where possible and through amended questions and aphasia-friendly supports where needed (Lanyon et al., Citation2019). For the second interview, participants were asked to share an artefact (e.g. photo, drawing, written note, voice recording, newspaper article etc.) that was significant to them about living alone with aphasia. Discussion of the artefact formed the basis of the second interview, with open-ended questions used to explore thoughts, feelings, and significance of the artefact (see ). This was an opportunity for both the researcher and participant to reflect and further explore relevant topics in a relaxed conversational manner.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, including noting relevant non-verbal communication. During transcription, pseudonyms were allocated and identifying information was removed from transcripts. Transcripts were imported into NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation2018) to assist with the organisation and management of data. Initially, the second author read each transcript multiple times to be immersed in the data. After multiple readings, preliminary annotations were made, highlighting key thoughts, concepts, and reflections. A line-by-line analysis was completed for each transcript, with codes identified. Codes were grouped and reviewed to develop initial themes and subthemes across the dataset. The first author carried out a subsequent analysis of the dataset, reviewing and critically engaging with the material to explore the relationship of codes to themes and the latent levels of meaning, to produce the final analysis in discussion with the team (see ).

Rigour

This study followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ; Tong et al., Citation2007). Member checking was completed during interviews, with the student researcher summarising and reporting findings to participants to ensure understanding. Validation of understanding of the first interview was also carried out in the second. The inclusion of participant-generated artefacts in the study provided an additional source of data, enhancing depth of analysis and contributing to the credibility of findings.

Result

The five people who participated in this study were all living alone due to divorce. Bill, Simon, and Audrey were divorced prior to their aphasia, while Joyce and Karen divorced following their strokes. Despite this, and unsurprisingly, their stories, situations, and responses to living alone were highly individual but patterns were evident across the data. is an illustration showing the four identified themes: relationships and reliance on others; risk, vulnerability, and uncertainty; loneliness and time alone; self-reliance and keeping busy. While these themes are not exclusively experienced by people who live alone, our findings suggest that living alone entails extra layers of difficulty and tension that require continuous negotiation. We have captured this dynamic negotiation with the arrow that runs across these themes and around a circle that represents the experience of living with aphasia. In the current study, the way participants talked about life with aphasia reflected the important issues identified in previous research (Brown et al., Citation2010) that living well with aphasia involves keeping busy (doing things), meaningful relationships, striving for a positive way of life, and communication. Our focus in this study is on how living alone influenced or impacted life with aphasia. We discuss each theme and these tensions below.

Relationships and reliance on others

Living alone meant that relationships with others entailed more effort, time, or planning, either on the part of the person with aphasia or, by extrapolation, for the person who supported them from beyond the home. The extent of this effort varied with living situation and circumstance, and severity of aphasia. Participants reported social networks consisted of a range of people: family, friends, neighbours, and health professionals. For example, Joyce was a 75-year-old woman who used a wheelchair and lived in her own home but was socially connected to others in her retirement village. Her aphasia was mild and she could access social events within the complex and communicate her needs with reasonable certainty. Her time alone was something she could control as there were always others close by.

For all participants, social networks had diminished with their aphasia, with more time spent with a close circle of family and friends, and focused on routines such as managing household chores or helping with transport to medical and therapy appointments. For example, Audrey, who had primary progressive aphasia, said she avoided activities that would highlight her impairments (“my speech gives me hell”) so her main contact was her daughter. She reported: “Katie [daughter] cooks meals for me … she does my ironing … Katie rings me every night.” This suggested a strong reliance on her daughter, the key person sustaining Audrey’s current living situation. Equally, Simon relied heavily on his sister when he needed help; his children did not live far away but they were busy with their own young children and he did not see them often.

Having a structured routine seemed to be important for people to counter aloneness and to maintain connections with others beyond the home. Reasons for seeing people were often practical rather than strictly social. Joyce said: “I come up here [to the clinic] once a week to physio … then other appointments, doctor, dentist, at least once a week, then on Saturdays my sister comes around.” Karen also had routines around therapy appointments and support groups, but these did not meet her social needs. Seeing people outside of the home was an effort because of her hemiparesis, inability to drive, and dependence on taxis, public transport, or asking friends for lifts. Karen was relatively young when she had her stroke, and her non-fluent aphasia had a profoundly negative impact on her life, affecting her marriage, contributing to losing access to her children, and impacting her career. It also left her reliant on others for managing the day-to-day administration of living alone: reading and responding to mail, filling in forms, making appointments, and coping with telephone bookings and queries. She was continuously negotiating barriers. For example, over and above her difficulties using the telephone, Karen experienced difficulties with understanding accents when call centres were based offshore and this compounded her comprehension difficulties on the telephone: “Telstra, forget it! Forget it! You know it’s somewhere, Indian, then Philippines, and oh my God no! There’s a chat, chat but I can’t read, I can’t umm I can’t, it’s pidgin English and slow, you know.”

The hurdles for completing written or telephone-based administration caused stress and slowed down her ability to manage her personal affairs, including her healthcare. She relied on friends and health professionals to assist with her plans for her schedule, her finances and completing paperwork:

Karen: Well, it’s documents, helping … people. I can’t write and I can’t read.

Interviewer: So then how do you do that?

Karen: My friends. Or it’s documents, sign. No read, reading, so …

Risk, vulnerability, and uncertainty

Participants reported occasions when living alone put them at greater risk of adverse outcomes than if they were living with another person. Several people mentioned the risk of falls and miscommunication or inadequate information transfer when seeking medical attention. Simon lived in an apartment block. He reported falling at home and indicated that he had managed to pull himself up off the floor by holding on to his wheelchair. Nobody was around to help him at the time. Joyce reported frequent falls when alone at home, but she was at least checked on regularly being in the retirement village: “The last fall was in my bathroom, they found that. I went to my GP, and they’d check and they kept asking why I fell and I didn’t know so I just lost my balance.” Bill also recalled occasions when his falls at home resulted in hospitalisation:

I came here with [name of speech-language pathologist], I was supposed to go to her on Friday and I said “in the hospital now I had a fall.” I had to go to the hospital up there … 1 or 2 years ago, I think. I couldn’t walk, couldn’t talk. Yeah, 2 days and I left the third day. I let myself out.

Yes, but I was really in a bad way, with this [holds right arm affected by stroke] too. I don’t know what, it just got worse and worse and worse, and I thought this is not right [puzzled look, furrowed brow], I tried lying down and [shakes head] so I rang the ambulance, and they brought me to here but [speech-language pathologist] came to see me when I was here in hospital … I said I don’t know what’s wrong with me and they didn’t know either.

Aphasia also left people vulnerable when out and alone in non-health-related situations. For example, Karen said that normally people in shops or services were patient and sympathetic when she explained her aphasia: “groceries, okay. Erm … But I approach to assistants, “I have a stroke. And I have speech problem” … so as people it’s “relax, okay speech problem.”

However, she recalled a traumatic incident where this was not the case and where her aphasia left her unable to defend or advocate for herself:

Interviewer: And has there ever been a time either out or at home where there has been a difficulty that you couldn’t manage?

Karen: Oh, yes. Yup.

Interviewer: What kinds of things did you do?

Karen: Erm … there’s erm … long ago … 12 years ago or 13 years ago I was going to [name of a large home retail company] and a teller, young woman, erm … it’s chucked, chucked my purse, potential item, chuck on the floor … yeah, yes! And young woman threw onto the floor and it’s camera [pointing to the ceiling to indicate CCTV] it’s shift, there’s no camera at all because young woman ‘it’s good’ [gesture that she knew she was not being filmed] and security guard and manager [name of store], it’s me! Escorted! [laughs ironically] Escorted to outside so.

Interviewer: And no one was around to see that?

Karen: Daytime, nah. Young woman … it’s [growling noise to show frustration]. So, anyway it’s problems with me, it’s day to day problems.

Being alone with aphasia appeared to have increased uncertainty for participants beyond day-to-day events and contributed to shaping their circumstances. Joyce spoke about living in a large family home prior to her stroke but having to sell it afterwards—not necessarily what would have happened had she not found herself alone following her divorce. Karen, whose marriage broke down following her stroke, suggested that it was the aphasia and her communication problems that caused this breakdown, eventually resulting in a change in direction (“upside down, it’s my stroke”) including her losing her career and being alone: “it’s me, it’s aphasia. It’s all of it, my family and divorce, my ex-husband, very frustrated is my ex-husband to me and me, it’s very frustrating to ex-husband. So, it’s broken down because communication.”

For Karen, the combination of aphasia and living alone meant financial uncertainty and had entailed a long period of instability during the divorce process, during which she had to find ways to manage complex legal paperwork and felt particularly disadvantaged and unsupported. Audrey faced uncertainty with her primary progressive aphasia, but this was compounded because of being alone, and her reliance on her daughter to maintain care and plan for her into the future.

Loneliness and time alone

Neither Bill nor Joyce equated living alone with loneliness, despite indicating a preference to spend more time with family and friends. Bill spent much of his time alone at home and did not even find the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic to be onerous: “I just didn’t go out. I don’t talk anyway.” He found mask wearing exacerbated his communication difficulties and he chose to remain at home rather than wear masks in public: “I used to get so annoyed with the masks, I wouldn’t go out … I just wouldn’t go out because of the masks.”

Participants reported that most of the time spent alone at home involved activities such as watching television, reading, or listening to audio books. Simon, a 62-year-old man with quite limited expressive language, spent time alone practising speech and language skills using his iPhone and iPad apps. Practising these skills was important to him because he could work alone, without a communication partner. Simon selected these devices and apps as his chosen artefacts (see ). He used his phone and iPad to explain himself to others, but they also represented his pathway to improvement. When asked how he had been able to manage these devices, even with his right-sided upper limb paralysis, he proudly indicated that he had worked out how to access and use the apps by himself. Simon relied on his communication aids, such as mobile phone apps and text-to-speech function, when interacting with others: “I can’t [gestures talking] but I can [use mobile phone to compose message].” In contrast, Karen viewed her life as: “shit life since stroke.” Karen now equated living alone with loneliness, highlighted by her choice of a word as her artefact: “it’s a word, it’s ‘lonely.’ That’s it”. She said: “I think it’s lonely, I miss my children …. But now it’s [her twins] 18 years old, it’s gone away, little bird [gesturing flying away], so, yeah. It’s aphasia. It’s not spouses or partner.”

Table II. Artefacts chosen by participants.

The impact of COVID-19 restrictions and lockdowns exacerbated Karen’s feelings of loneliness and depression: “honestly, it’s … I’m depressed, you know, it’s very hard, so I was TV, it’s mental health, this is me, I’m depressed last year, yeah.” Prior to the pandemic, Karen was volunteering at a second-hand clothes shop. This stopped during the periods of lockdown and was no longer an option. Karen’s communication difficulties contributed to, and compounded, an already difficult context of loss and caused practical difficulties in social settings resulting in feelings of frustration and isolation:

Yeah, it’s very hard, it’s frustrated and umm at the beginning, it’s last 15 years ago my friends, distance. So, distance with me and now it’s I’m lonely, yeah, that’s it, lonely and this is me. I can’t do [gestures talking] crowded and very, very noisy so, I like umm you know, one friend, face-to-face or different friends, you know five people so yep. I have lonely, is alone.

Self-reliance and keeping busy

For Joyce, living alone was a positive experience, enabling a level of independence and autonomy despite her disabilities: “I’ve always been very independent so the effect [of living] on my own doesn’t bother me … I have as much convenience as I want.” However, Joyce valued her relationships with others. Her choice of artefacts, her family tree, ancestry documents, and family photos, demonstrated her connection with others in a context where she spent so much time by herself. Joyce only became interested in researching her family ancestry once she started living alone: “it’s something I do now that I’ve got, maybe more time.” Connection to family was important, despite them living overseas. Joyce still took trouble to maintain a circle of established friends beyond her retirement village. She was comfortable using public transport, but she described how geographic distance prevented her from seeing friends regularly: “I’ve got other friends as well but they’re all near [name of suburb]. So, because I live in [name of suburb] it’s another half hour for them.” Joyce valued her ability to travel independently but she experienced challenges with public transport, such as additional travel time, resulting in fatigue:

Trouble is, because I don’t walk and I need the chair … public transport is good, I like to get about on buses and trains and all sorts of things, but the private ones, they’re a bit small … minibuses, they can’t take my chair. All I can do is get taxis … I’m getting quite good at getting buses, but it takes two hours to get [friend’s suburb] to my home. This is it. I’m not getting any younger and it’s tiring.

Well, I don’t talk to anyone … just go in, don’t talk to them, say at the post office, all the things I get at the post box, office. All I do is hand them the thing, get them, and pay whatever, $100, $300 [gestures swiping bank card], without saying a word really.

A common way to keep busy was by attending aphasia and stroke support groups at various times through the recovery journey. The level of success with this option varied. Joyce, who had mild communication difficulties, connected with broader stroke-related support groups, rather than those that were aphasia specific:

I didn’t find it much use. No, because I’m strong. I went to two meetings I think, they, I don’t know, I just found that they weren’t all on the same wavelength [laughs]. It’s hard, it takes a lot of energy to talk to people and I just thought “I don’t think I’m interested,” which is probably a bit snobbish. I go to the stroke group at the hospital. I think that’s better. Some of the people have been through as much as me.

For Bill, who attended aphasia support groups regularly, seeing other people with aphasia helped shape his outlook about his own communication difficulties: “there’s a lot of people out there that have no words and they were good before so I’m thankful for just a little bit.” Aphasia support groups were important to Bill, despite having difficulties articulating the reason he continued to attend: “I keep going along, I’ve never missed one … I keep going, don’t know why … there must be some reason that I go there but I don’t know why.”

Audrey found it increasingly difficult to keep busy. She said: “I don’t do anything. Well, I don’t go anywhere much and birthdays and umm birthdays.” She described how she used to attend various arts and crafts clubs, although could no longer do so due to increasing disability: “yes I quilted and drawing, yeah and art.” She also enjoyed reminiscing about hobbies and childhood memories, as highlighted by her choice of artefacts, saying: “yes … and I wish I could do it again.” Audrey shared her memory book, a scrapbook created by her daughter with various photos, memories, and trinkets from her life. She also shared her communication book, created by her speech-language pathologist. Audrey’s artefacts suggested a desire to continue the hobbies and activities she once enjoyed. Karen also kept busy with various hobbies and interests, some supported by her applications to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS): “I have art classes so it’s NDIS funding. Umm … I have swimming … it’s not funding, NDIS.” She was also looking for a new volunteering role: “I had, I have support co-ordinator, [name of company] and a social work, a woman came to my place and I have potential, it’s a volunteer, soup kitchen or whatever but I’m … social worker is waiting to me.”

Before his stroke, Simon travelled a great deal, including taking a caravan around Australia. He used to enjoy speedway and racing cars, but now watched racing on television. Simon’s social activities had been outdoors prior to his stroke but he was now increasingly indoors, although he had recently started going to a men’s shed (but he also said he found it hard to communicate with people there). He used a gym that was attached to his apartment block (wheelchair-based exercises), attended health appointments and therapy sessions, and spent a lot of time home alone practising his communication skills: “before I can’t, now I can … before none, a little bit now, before none.” Simon’s chosen artefacts were his mobile phone and iPad apps because it was through these that he managed his interactions, for example, a text-to-speech function and visuals such as photos, maps, and emails to support his communication. However, his options were restricted, and his aphasia was profoundly challenging:

Interviewer: What does living alone mean for you?

Simon: Hard … hard.

Interviewer: What makes it hard?

Simon: Hard … people, I can’t … [points to mouth] people, I can’t.

Discussion

This study provides insights into the experiences of five people with aphasia who lived alone, an initial exploration of an under-researched group to highlight the specific issues that they face. As Stanley et al. (Citation2017) noted, living alone does not necessarily equate with being lonely, but their research highlighted the importance of having a balance of social connection and keeping busy to mitigate time spent alone. For people with aphasia, the buffer against loneliness provided by social connection and activity may be more difficult to achieve because of communication challenges. This vulnerability may be compounded if post-stroke physical impairments or inability to drive make leaving the house harder. Stanley et al. (Citation2017) also noted their participants’ negative attitude to “sitting around,” which they associated with being old and bored (p. 238). Sitting at home may be more likely for people after a stroke, perhaps with a hemiplegia or when in a wheelchair, as for Joyce and Simon, for example. Even when sitting at home, people with aphasia have fewer choices in keeping busy, for example, not necessarily being able to enjoy reading a book or having a conversation on the telephone as they did before. Our study demonstrated, both in the interviews and through the artefacts, that participants sought activity to keep busy and had routines in place such as through attending aphasia supports or volunteering. Keeping busy appears to help manage loneliness but also provides a sense of agency in a context where aphasia can so easily leave people dependent on others. Interestingly, where people experience stigma related to a chronic condition, such as aphasia, they may express that agency and control by actively withdrawing from social situations (Haslbeck et al., Citation2012) and those living alone, without a partner to encourage them to participate, may be at greater risk of this (Ford et al., Citation2024).

Some participants reported the importance of support groups, but community aphasia groups do not necessarily suit everyone (Lanyon et al., Citation2018b). Keeping connected was crucial for wellbeing (Azios et al., Citation2022; Hilari et al., Citation2019; Lanyon et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Vickers, Citation2010) and for managing practical and administrative tasks. Participants relied on family beyond the home or external agencies to assist with personal care, home maintenance and food delivery. All participants reported they wished to spend more time with family and friends suggesting that it may be more difficult for this group, even when supported by others, to feel optimally connected. In the context of living with the consequences of stroke, of difficulties with transport, of previous divorce, and restrictions from pandemic-related lockdowns, participants conveyed a sense of loss of family, career, social networks and participation in activities once enjoyed. Given low mood and depression are common sequelae of aphasia (Kauhanen et al., Citation2000), it is important for speech-language pathologists to be aware of the living situation of their clients, of potential chronic loneliness, and of their networks and options for support. Ultimately, this should be an important influence on the direction of intervention.

This study also highlighted participants’ concerns that living alone put them at risk of adverse outcomes, such as falls and miscommunications when seeking medical attention. Living alone is a well-documented risk factor for falls (Lage et al., Citation2023) and people with aphasia may be at greater risk of falls (Sullivan et al., Citation2023) as well as of adverse events more generally during a hospital admission (Hemsley et al., Citation2013). Therefore, being at the intersection of living alone and having aphasia should alert health professionals to be aware of the greater potential risks, not to limit people’s choices but rather to support their ability to live safely at home. For example, training health professionals, such as physiotherapists, in supported communication (Kagan et al., Citation2001) may assist their ability to discuss falls prevention with people with aphasia. Several participants noted difficulties conveying their health concerns without a family member or friend to advocate for them and this context is also recognised as challenging for health professionals (Carragher et al., Citation2021). We would recommend that speech-language pathologists explicitly consider people’s living situation when discussing and planning intervention to gauge how it might impact over time, and perhaps ask directly about loneliness when addressing strategies for participation. Working closely with other team members, such as an occupational therapist, would be useful when considering ways to engage in meaningful activity to manage time alone. Given the seriousness of loneliness for health and wellbeing, these actions are important.

This research had some limitations. This was a small project and the five participants recruited for this study were all living in a metropolitan area, living alone due to divorce, attending a clinic associated with a university, and therefore connected to services. Having two opportunities for interview and inclusion of an artefact was useful, but there were aspects of people’s experiences that could be explored in more depth, and talking with significant others would offer a different perspective. One participant had a diagnosis of primary progressiveaphasia rather than post-stroke aphasia. This was not specifically addressed in this study but experiences of living alone with a progressive aphasia are likely to require more investigation.

Conclusion

Living alone does not necessarily equate with loneliness but it increases the risk of loneliness. We identified four themes: relationships and reliance on others; risk, vulnerability, and uncertainty; loneliness and time alone; self-reliance and keeping busy. While these themes are not exclusively experienced by people who live alone, our findings suggest that living alone entails extra layers of difficulty and tension that require continuous negotiation. Living alone with aphasia compounds and complicates the extra considerations already required when there is no partner or other caring person in the home. The buffer against loneliness provided by social connection and meaningful activity may be more difficult to achieve when living with aphasia. While experiences vary, people with aphasia may be more reliant on others to manage the many language-based practical and administrative tasks required to live alone. Over and above the physical sequelae of their strokes, people with aphasia may be more vulnerable and at risk of adverse events because of difficulties with self-advocacy, and be less able to benefit from the activities they do engage in because of communication barriers.

In summary, the intersection of living alone, loneliness, and living with aphasia needs more research (Sherratt, Citation2024). We need to better understand daily challenges, and service access and provision for this group, as well as the specific experiences of family and friends who provide support from a distance. It would be useful to understand more about how living alone with aphasia intersects with age, gender, aphasia severity, comorbidity, financial situation, returning to the workforce, and so on. In addition, more work is needed to understand the context of risk for this group and how this can be addressed, without diminishing the agency and independence so important for people. It may also be important to develop more nuanced understanding of the relationship between living alone, aloneness, loneliness, and social isolation in the context of aphasia so that services can be tailored to people’s needs and adjusted to changes over time. The stories reported in this study provide a useful start for clinicians and service providers to recognise and address the intersections, and potential health and psychosocial implications, for people with aphasia who live alone.

Figures and tables.docx

Download MS Word (34.2 KB)Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Household and family projections Australia, 2016-2041 (Cat. No. 3236.0). ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs.nsf/mf/3236.0

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017). Australian demographic statistics, 2016. (Cat. No.3101.0). ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs.nsf/0/1cd2b1952afc5e7aca257298000f2e76

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Heart, stroke and vascular disease: Australian facts. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-diseases/hsvd-facts

- Azios, J. H., Strong, K. A., Archer, B., Douglas, N. F., Simmons-Mackie, N., & Worrall, L. (2022). Friendship matters: a research agenda for aphasia. Aphasiology, 36(3), 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2021.1873908

- Bergland, A., Tveit, B., & Gonzalez, M. (2016). Experiences of older men living alone: A qualitative study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(2), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1098759

- Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2016(6), CD000425. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage Publications.

- Brown, K., Davidson, B., Worrall, L., & Howe, T. (2013). Making a good time”: the role of friendship in living successfully with aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15(2), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2012.692814

- Brown, K., Worrall, L., Davidson, B., & Howe, T. (2010). Snapshots of success: An insider perspective on living successfully with aphasia. Aphasiology, 24(10), 1267–1295. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687031003755429

- Cacioppo, J., Cacioppo, S., & Boomsma, D. (2014). Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cognition and Emotion, 28(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.837379

- Carragher, M., Steel, G., O'Halloran, R., Lamborn, E., Torabi, T., Johnson, H., Taylor, N. F., & Rose, M. L. (2021). Aphasia disrupts usual care: the stroke team’s perceptions of delivering healthcare to patients with aphasia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(21), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1722264

- Coyle, C. E., & Dugan, E. (2012). Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 24(8), 1346–1363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264312460275

- Cruice, M., Worrall, L., & Hickson, L. (2006). Quantifying aphasic people’s social lives in the context of non‐aphasic peers. Aphasiology, 20(12), 1210–1225. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030600790136

- Dale, B., Soderhamn, U., & Söderhamn, O. (2012). Life situation and identity among single older home-living people: a phenomenological-hermeneutic study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health Well-Being, 7. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v7i0.18456

- Dalemans, R., de Witte, L., Wade, D., & van den Heuvel, W. (2010). Social participation through the eyes of people with aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45(5), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.3109/13682820903223633

- De Vaus, D., & Qu, L. (2015). Demographics of living alone. (Australian Family Trends No. 6). Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Department of Health. (2021). Australian Government response to the final report of the royal commission into aged care quality and safety. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/tenalizedt-government-responseto-the-final-report-of-the-royal-commission-into-aged-care-quality-and-safety

- Desai, R., Leung, W. G., Fearn, C., John, A., Stott, J., & Spector, A. (2020). Living alone and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 97, 102312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2020.101122

- Duane, F., Brasher, K., & Koch, S. (2013). Living alone with dementia. Dementia (London, England), 12(1), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301211420331

- Evans, I., Llewellyn, D., Matthews, F., Woods, R., Brayne, C., & Clare, L., CFAS-Wales Research Team. (2019). Living alone and cognitive function in later life. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 81, 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.12.014

- Flowers, H., Skoretz, S., Silver, F., Rochon, E., Fang, J., Flamand-Roze, C., & Martino, R. (2016). Poststroke aphasia frequency, recovery, and outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(12), 2188–2201.e2188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.03.006

- Ford, A., Douglas, J. M., & O'Halloran, R. (2024). From the inner circle to rebuilding social networks: A grounded theory longitudinal study exploring the experience of close personal relationships from the perspective of people with post stroke aphasia. Aphasiology, 38(2), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2023.2185480

- Guillemin, M. (2004). Understanding illness: Using drawings as a research method. Qualitative Health Research, 14(2), 272–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303260445

- Harmon, T. (2020). Everyday communication challenges in aphasia: descriptions of experiences and coping strategies. Aphasiology, 34(10), 1270–1290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1752906

- Haslbeck, J., McCorkle, R., & Schaeffer, D. (2012). Chronic illness self-management while living alone in later life. Research on Aging, 34(5), 507–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027511429808

- Hemsley, B., Werninck, M., & Worrall, L. (2013). That really shouldn’t have happened”: people with aphasia and their spouses narrate adverse events in hospital. Aphasiology, 27(6), 706–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2012.748181

- Henning-Smith, C. (2016). Quality of life and psychological distress among older adults: The role of living arrangements. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35(1), 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464814530805

- Hilari, K., Behn, N., Marshall, J., Simpson, A., Thomas, S., Northcott, S., Flood, C., McVicker, S., Jofre-Bonet, M., Moss, B., James, K., & Goldsmith, K. (2019). Adjustment with aphasia after stroke: Study protocol for a pilot feasibility randomised controlled trial for SUpporting wellbeing through PEeR Befriending (SUPERB). Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0397-6

- Hilari, K., Northcott, S., Roy, P., Marshall, J., Wiggins, R. D., Chataway, J., & Ames, D. (2010). Psychological distress after stroke and aphasia: the first six months. Clinical Rehabilitation, 24(2), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509346090

- Hilari, K., & Northcott, S. (2017). Struggling to stay connected”: Comparing the social relationships of healthy older people and people with stroke and aphasia. Aphasiology, 31(6), 674–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2016.1218436

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

- Jensen, M., Marott, J., Holtermann, A., & Gyntelberg, F. (2019). Living alone is associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: 32 years of follow-up in the Copenhagen Male Study. European Heart Journal - Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes, 5(3), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcz004

- Jiang, Y., Li, M., & Chung, T. (2023). Living alone and all-cause mortality in community-dwelling older adults: The moderating role of perceived neighborhood cohesion. Social Science & Medicine, 317, 115568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115568

- Kagan, A., Black, S., Duchan, J., Simmons-Mackie, N., & Square, P. (2001). Training volunteers as conversation partners using “Supported Conversation for Adults with Aphasia” (SCA): A controlled trial. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 44(3), 624–638. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2001/051)

- Kauhanen, M., Korpelainen, J., Hiltunen, P., Määttä, R., Mononen, H., Brusin, E., Sotaniemi, K. A., & Myllylä, V. V. (2000). Aphasia, depression, and non-verbal cognitive impairment in ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 10(6), 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1159/000016107

- Kertesz, A. (2007). Western aphasia battery–revised. Pearson.

- Lage, I., Braga, F., Almendra, M., Meneses, F., Teixeira, L., & Araújo, O. (2023). Older people living alone: A predictive model of fall risk. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136284

- Lanyon, L., Hersh, D., Bickford, J., Baker, J., Nang, C., Rose, M., & Worrall, L. (2019). Using in-depth, semi-structured interviewing. In R. Lyons & L. McAllister (Eds.) Qualitative research in communication disorders: An introduction for students and clinicians (pp. 285–312). J&R Press.

- Lanyon, L., Worrall, L., & Rose, M. (2018a). What really matters to people with aphasia when it comes to group work? A qualitative investigation of factors impacting participation and integration. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(3), 526–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12366

- Lanyon, L., Worrall, L., & Rose, M. (2018b). Exploring participant perspectives of community aphasia group participation: from “I know where I belong now” to “Some people didn’t really fit in. Aphasiology, 32(2), 139–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2017.1396574

- Laures-Gore, J., Dotson, V., & Belagaje, S. (2020). Depression in poststroke aphasia. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(4), 1798–1810. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00040

- Mahoney, J. E., Eisner, J., Havighurst, T., Gray, S., & Palta, M. (2000). Problems of older adults living alone after hospitalization. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 15(9), 611–619. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06139.x

- Manning, M., MacFarlane, A., Hickey, A., Galvin, R., & Franklin, S. (2021). I hated being ghosted’ - The relevance of social participation for living well with post-stroke aphasia: Qualitative interviews with working aged adults. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 24(4), 1504–1515. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13291

- Murphy, B. M., Elliott, P. C., Le Grande, M. R., Higgins, R. O., Ernest, C. S., Goble, A. J., Tatoulis, J., & Worcester, M. U. (2008). Living alone predicts 30-day hospital readmission after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation: Official Journal of the European Society of Cardiology, Working Groups on Epidemiology & Prevention and Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology, 15(2), 210–215. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f2dc4e

- Odzakovic, E., Kullberg, A., Hellström, I., Clark, A., Campbell, S., Manji, K., Rummery, K., Keady, J., & Ward, R. (2019). It’s our pleasure, we count cars here’: an exploration of the ‘neighbourhood-based connections’ for people living alone with dementia. Ageing and Society, 41(3), 645–670. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19001259

- O'Halloran, R., Renton, J., Harvey, S., McSween, M. P., & Wallace, S. J. (2023). Do social determinants influence post-stroke aphasia outcomes? A scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 46(7), 1274–1287. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2023.2193760

- Pantell, M., Rehkopf, D., Jutte, D., Syme, S. L., Balmes, J., & Adler, N. (2013). Social isolation: a predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. American Journal of Public Health, 103(11), 2056–2062. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301261

- Perissinotto, C. M., & Covinsky, K. E. (2014). Living alone, socially isolated or lonely–what are we measuring? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(11), 1429–1431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2977-8

- Pierce, L., Wilkinson, L., & Anderson, J. (2003). Analysis of the concept of aloneness as applied to older women being treated for depression. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 29(7), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.3928/0098-9134-20030701-06

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo (Version 12). Qualitative data software. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysissoftware/home

- Reeves, M. J., Prager, M., Fang, J., Stamplecoski, M., & Kapral, M. K. (2014). Impact of living alone on the care and outcomes of patients with acute stroke. Stroke, 45(10), 3083–3085. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006520

- Segraves, M. (2004). Midlife women’s narratives of living alone. Health Care for Women International, 25(10), 916–932. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330490508622

- Sherratt, S. (2024). People with aphasia living alone: A scoping review. Aphasiology, 38(4), 712–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2023.2227403

- Smith, B., & Lim, M. (2020). How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation. Public Health Research & Practice, 30(2). https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp3022008

- Smith, K., & Victor, C. (2019). Typologies of loneliness, living alone and social isolation, and their associations with physical and mental health. Ageing and Society, 39(8), 1709–1730. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000132

- Snell, K. (2017). The rise of living alone and loneliness in history. Social History, 42(1), 2–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071022.2017.1256093

- Stanley, M., Richard, A., & Williams, S. (2017). Older peoples’ perspectives on time spent alone. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(3), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12353

- Sullivan, R., Hemsley, B., Harding, K., & Skinner, I. (2023). ‘Patient unable to express why he was on the floor, he has aphasia.' A content thematic analysis of medical records and incident reports on the falls of hospital patients with communication disability following stroke. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders (IJLCD), 58(6), 2033–2048. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12916

- Taube, E., Jakobsson, U., Midlöv, P., & Kristensson, J. (2016). Being in a Bubble: the experience of loneliness among frail older people. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(3), 631–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12853

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). Database on household size and composition 2019. United Nations.

- Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S., & Hanratty, B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart (British Cardiac Society), 102(13), 1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790

- Vickers, C. P. (2010). Social networks after the onset of aphasia: The impact of aphasia group attendance. Aphasiology, 24(6-8), 902–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030903438532

- Victor, C., Scambler, S., Bond, J., & Bowling, A. (2000). Being alone in later life: loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 10(4), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259800104101

- Worrall, L., Sherratt, S., Rogers, P., Howe, T., Hersh, D., Ferguson, A., & Davidson, B. (2011). What people with aphasia want: Their goals according to the ICF. Aphasiology, 25(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2010.508530