Abstract

Purpose

Communication partner training is a recommended intervention for partners of people with acquired brain injury. In this paper we explore the past, present, and future of communication partner training (CPT) based on our 2023 Speech Pathology Australia national conference address.

Method

We focus on our research team’s contributions, and highlight research knowledge across stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and dementia. This work is anchored in the voice of people with communication disability. One partner in the CPT journey, Rosey Morrow, co-authors this paper.

Result

The CPT evidence base for acquired neurological conditions is growing, including in the areas of technology, co-design, and translation. However, knowledge and implementation gaps remain.

Conclusion

The future of CPT will require us to harness co-design and technology, whilst meeting the implementation challenges of complex systems to enable communication for all.

Introduction

This paper outlines most of the content in our keynote presentation from the 2023 Speech Pathology Australia national conference (in Hobart) on the past, present, and future of communication partner training, or CPT as we’ll call it. We address research knowledge in technology, co-design, and implementation across acquired brain injury including stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and dementia. The voice of people with communication disability is critical and as co-author, Rosemary (Rosey) Morrow brings her expert lived experience to the topic. She had a severe brain injury with aphasia, dysphagia, dysarthria, and cognitive-communication impairments. Her story is familiar and, of course, unique. Here, Rosey introduces her own past and we will return later in the article to reflect on her journey with CPT and her recovery.

In 2016 my life changed completely: I was T-boned by a car when I was riding my bicycle. Thankfully, I have no memory of it—it’s what I’ve been told by the police and family. I had post-traumatic amnesia for 38 days. My memory is still affected, and the 6 months around the accident are completely missing. Surprisingly, there have been many upsides to the accident—not that I thought so at the time: my thinking was moment to moment. Those closest to me knew what I’d lost and their projections of my future would have been shocking. The right side of my face drooped, I couldn’t move one side of my body, I had dysphasia, known as aphasia, cognitive-communication disorder (CCD), and my voice was almost non-existent. It was a far cry from what I had been: the magazines’ production editor of the Australian Financial Review. At the time, I didn’t “compare and contrast” my situation, I just got on with living. It took about 18 months after the accident to put it all together and that’s when, at the suggestion of my speech therapist, I saw a psychologist. My speech therapist was integral to many of the upsides I have experienced since that fateful day. After 5 months in hospital and rehab, I went home in January 2017. That’s when I came under Ryde Rehab’s Brain Injury Community Rehab Team and my life changed again.

Definition of CPT

Now we are grounded in the lived experience of communication disability, what do we even mean when we say CPT? A question I (EP) often ask in workshops could help us reflect on that. If I said there is a great new job for you, but you need be able to be able to use html code to get it, which one of the following would most help you to be successful and confident? The choice are: (a) a two-page handout; (b) the handout plus a quick explanation from an expert; or (c) the handout, video/live demonstration, practice with feedback and discussion, and monitoring your progress, including testing yourself. People rarely say (a) or (b). This exercise shows the importance of what we mean with regards to CPT, the clue is in the name—training—not just education alone. Professor Nina Simmons Mackie and colleagues defined CPT as “a form of environmental intervention in which people around the person with aphasia [such as family, friends, clinicians, broader staff, and volunteers] learn to use strategies and communication resources to aid the individual with aphasia” (or additionally, individuals with cognitive-communication impairment; Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2016, p. 2202). Essentially, the “learn to use” represents CPT being a skill, and training requires active learning elements to distinguish it from education.

Why do CPT? Why do we need it?

We know communication is challenging for people with communication support needs. Communication disability can often be an invisible disability and communication can also be difficult for people who communicate with individuals with communication support needs. The voice of people with communication support needs, their family, and clinicians as communication partners in the evidence base gives us some answers to this question. Here are a few examples.

In Nickbakht et al. (Citation2023), a person with dementia explains, “just chatting about the weather, it’s like there’s nothing wrong with me. But as soon as we get down to some nitty-gritty and I've got to think about stuff, it all just breaks down – pronunciations of the words … wrong words” (Results, 7.1, Theme 1, para 1).

For a person with aphasia, the challenge of communicating with staff is clear: “that doctor, who, yeah, who came to visit me regularly … She told me I had been lucky. Well, great. And I couldn’t … I thought, let her talk. I don’t understand … couldn’t. She kept talking and talking. So I just let her” (van Rijssen et al., Citation2023, p. 76).

According to a person with cognitive-communication impairment after TBI: “the case conference was chaos! No structure, and people kept raising their hands and almost interrupting each other … and I actually felt it was a little unprofessional. I had to keep track of who said this and who said this … it was really hard to keep up … Some of the things that were said, I do not know if I have processed quite right” (Christensen et al., Citation2023).

The voice of families reinforces the communication challenges and needs in different ways, including:

For a daughter of a man with global aphasia who is guest lecturer in my curriculum: “it’s just a game of charades. Sometimes I have to walk away when I can’t work out what he is saying. I did not get any training or help in how to communicate with Dad” (C. Brennan, personal communication, 2020).

For a caregiver of a person with dementia: “well, you can discuss but you have to lead the conversation because she very seldom carries on a conversation unless you start it, and then it’s more or less question and answer … she just doesn’t respond” (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012, p. 598).

For the daughter of a woman with aphasia in hospital: “in my mum’s case I think there were eight people in the ward(.) But(.) they didn’t communicate … they weren’t encouraged to communicate with each other, my mum would sit there all day and say nothing” (Clancy et al., Citation2020, p. 329).

The communication challenges and needs also extend to clinicians, who also require support to communicate well with people with communication disability as the following examples show.

“The pt [patient] is walking restlessly around in the unit … [She] can’t explain what she is looking for, what she says doesn’t make sense. … I explain that I am not sure what she is looking for several times, but she can’t understand that I [don’t] understand her” (staff member working in subacute brain injury ward, Nielsen et al., Citation2020, p. 452).

“I know that sounds really bad but if I’m in a hurry and I know what they’re saying is not urgent … I’ll just say that I’ve understood” (clinician working with people with aphasia in subacute/community setting, Carragher et al. Citation2021, p. 3008).

However, there is great will to provide quality communication support, for example, “a lot of time is spent on communication, where I feel that if I knew more about how to approach this, then I could do it much better for my clients …and much more effectively” (staff member working with people with TBI in inpatient setting, Christensen et al., Citation2023, p. 834).

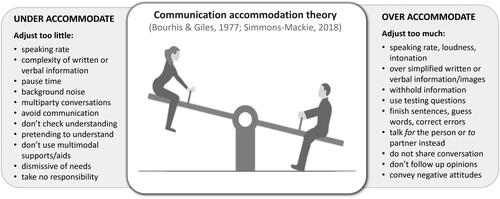

Communication accommodation theory

What does this communication and interaction challenge look like in more detail? Communication accommodation theory explains that, depending on how we view people’s competence and status, we can attempt to converge to be closer in speaking style, stay neutral, or even diverge to accentuate differences (Bourhis & Giles, Citation1977; Simmons-Mackie, Citation2018). This communication-based accommodation can be quite frustrating for people with invisible disability, and it is worth being clear about what we are trying to shape with CPT. outlines different ways communication partners can both under- and over-accommodate in their communicative interactions with people with communication support needs. For example, a communication partner may under-accommodate in a conversation with a person with auditory comprehension difficulties by failing to slow down their speech to enable increased understanding of the message. On the other hand, the communication partner could over-accommodate with their speech rate by talking to a person with dysarthria in a very slow, exaggerated rate, which may convey negative or discriminatory attitudes.

Potential consequences of over- or under-accommodated communication

The consequences of these approaches to communication are significant, and include nurses directing or limiting conversations with people with aphasia (Hersh et al., Citation2016) and multidisciplinary teams viewing aphasia as something that disrupts their ability to provide usual patient care (Carragher et al., Citation2021). Communication disability can also be associated with adverse events in hospital (Bartlett et al., Citation2008), falls (Sullivan et al., Citation2020), and reduced participation in healthcare decision-making (Hemsley et al., Citation2013). Additionally, “elderspeak” can increase resistiveness to care and agitation, leading to increased use of antipsychotics (Savundranayagam et al., Citation2005). People with aphasia feeling unsupported during interpersonal communication can be connected to decreased opportunities for social interactions and intense feelings of loneliness (Harmon, Citation2020). Just to remind us of the intimacy of communication from one of my other research areas, we know that spouses of people with aphasia reported that their partner with aphasia was no longer able to express their feelings or engage in sexually intimate conversation (McLellan et al., Citation2014). Therefore, consequences of over- and under-accommodation can be significant.

Communication partner training programs

Have we done anything to tackle these issues with communication partners across stroke, brain injury, and dementia? Yes. We have early pioneering teams, programs, and CPT research and we highlight key programs in . Most key or published programs have been conducted in the field of aphasia, often post-stroke aphasia.

Table 1. A summary of prominent key communication partner training (CPT) programs across the stroke, brain injury, and dementia populations.

Evidence for CPT program efficacy across stroke, TBI, and dementia

We see evidence for benefits and efficacy of these and other CPT programs summarised in systematic reviews across populations of aphasia (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2016), cognitive-communication disorder (CCD) in TBI (Wiseman-Hakes et al., Citation2019), and CCD in dementia (Folder et al., Citation2024). Benefits, to varying degrees, include increased communication-partner knowledge, confidence, skills, and quality of life (QOL). For people with communication disability, CPT also supports increased activities, participation, confidence, identity, and QOL, with most studies exploring face-to-face CPT and a smaller evidence base existing for telehealth and online modes (Power et al., Citation2023). However, there are important cautions and work still to do. For example, many CPT studies have small numbers or are more focused on stroke or TBI in chronic stages and dementia in later stages. Little evidence exists in the right-hemisphere stroke population and there is often exclusion of culturally and linguistically diverse populations. Long-term follow-up assessment to determine if communication partners’ (CPs) knowledge or skills have been sustained is rare, with the exception of Togher et al. (Citation2013). CPT outcome measures vary across studies from independently rated observational scales (Togher et al., Citation2013), conversational analysis techniques (e.g. Beckley et al., Citation2013), and self-report measures (e.g. Power et al., Citation2021). Assessment can be challenging: to get reliability on rating scales, fine linguistic analysis can be clinically difficult, few measures have been co-designed with people with communication disability, and often knowledge, rather than skill, is assessed. We also have not specifically tested many proposed active training ingredients, although there are patterns of delivery and content components of CPT that appear common to higher-quality CPT research outcomes (see below). We also need more digital health and co-designed research. Sustained CPT implementation and scale-up can be hard as, unlike other interventions that may require access to the person with communication disability alone, CPT requires access and engagement of familiar and unfamiliar CPs as well.

CPT elements in published programs

O’Rourke et al. (Citation2018) compared key CPT programs for unfamiliar CPs with randomised control trial level evidence in stroke (SCA™), TBI (TBI Express), and dementia (MESSAGE), to understand any common elements and strategies used in the efficacious, high-quality programs that may be leveraged for more general training programs. O’Rourke et al. (Citation2018) found 10/12 strategy categories were common across populations, such as learning how to alter speaking style, fostering acknowledgement of competence, and learning how to provide multi-modality supports such as key words and visuals to reveal competence, enabling people with communication disability to express themselves. While common, many of the elements had population-specific nuances. For example, a common learning was around “choosing a conversation topic,” which in aphasia CPT focused on signalling a new topic and writing down key words; while for TBI CPT, it was clearly signalling a new topic and choosing personally relevant topics; and in dementia CPT, it was signalling the new topic and choosing topics that align with long-term memory strengths of the individual. We found 3/10 common negative behaviours for CPs to avoid, with the main one being testing questions (asking a question you know the answer to, then appraising the response from the person with communication support needs as right or wrong). Only three specific individual strategies were identical to all programs, including “use short simple sentences,” “give one piece of information at a time,” and “give time to respond.” Many people with communication disability have said to us they would be very happy even with that! Based on these findings, it may be possible to have a more generic CPT program, especially for staff who may interact with people with a variety of aetiologies. However, there are clearly still population-specific elements to consider and more in-depth work to be done on what are critical ingredients of CPT. From O’Rourke et al. (Citation2018) and the systematic reviews above, we have some knowledge of CPT delivery elements included in most of the efficacious programs that targeted skills improvement. Elements that are often present include:

knowledge through education;

demonstration (showing how to do a task, increasing awareness);

active practice (role-plays, trying out strategies, shaping behaviour);

reviewing own performance (reflective exercises and self-tests), getting feedback from others, monitoring over time; and

use of videos, experts, and cases.

Elements 2, 3, and 4 especially would distinguish education from training. For an example of what CPT could look like within a session with some of these elements, see the Supplementary Material.

CPT is recommended clinical practice in stroke, TBI, and dementia guidelines

Based on the evidence above, CPT is now recommended practice in clinical practice guidelines, including the Stroke Foundation Living Guidelines (Chapter 5, Stroke Foundation, Citation2021) for staff and family CPs of people with aphasia. However, the Stroke Guidelines are largely silent on CPT for right hemisphere communication impairment. CPT and CPT delivered through telehealth is recommended in the 2023 INCOG Brain Injury Guidelines (INCOG refers to an international panel of experts in cognitive rehabilitation in TBI; Cognitive Communication Recommendation #4a/f, Togher et al., Citation2023). The Australian dementia guidelines recommend CPT for staff and family, highlighting CPT among its 10 implementation priorities. We should be doing it, but as we know and have explored earlier, issues remain and there is evidence to create, especially around technology, co-design, and implementation. Therefore, our work is ongoing. We now highlight three very recent studies to increase the evidence base for CPT with students, families, and clinicians respectively.

Current CPT research

Firstly, focusing on training student health professionals, our team evaluated the efficacy of a 50-minute, online CPT program (introductory online SCA™, Aphasia Institute) combined with a 1-hour video-based (Zoom) active-learning workshop for 236 students from 11 allied health professions (Power et al., Citation2023). We used the Aphasia Attitudes, Strategies, and Knowledge survey (AASK; Power et al., Citation2021) to examine outcomes of the training on (a) aphasia knowledge, (b) communication strategy knowledge, and (c) attitudes (confidence, comfort) to interacting with people with and without aphasia. Students completed the assessment at four timepoints including at baseline, after the online module, after the workshop, and 6 weeks later. All timepoints were completed by 106 students. We observed a significant improvement in knowledge of aphasia and communication strategies, and confidence and comfort with talking with people with aphasia after the online training, which did not increase significantly after the workshop training (Power et al., Citation2023). A slight decline in some domains was observed at the follow-up, and skill performance was not evaluated—but we will return to that issue in the implementation section. Qualitative findings told us what stood out for students, including attitudes (“strong guidance and teaching in understanding that people with aphasia are competent and intelligent. … Before … I would have automatically assumed that healthcare decisions need to be made with other[s],” p. 314) and knowledge of effective communication techniques (“it … helped me learn about some effective techniques … I wouldn’t have known where to start,” p. 324). Participants also recommended future inclusion of the “lived experience or narrative of a real person living with aphasia [which] might stimulate greater engagement … and further stress the humanity at play” (Power et al., Citation2023, p. 325).

A second CPT project is focused on people with dementia and their family or familiar CPs. This project, Dementia Connect, was born out of PhD student Naomi Folder’s clinical need for a step-by-step CPT program with active practice tasks for family of people with dementia. Her systemic review (Folder et al., Citation2024) showed that many current programs were outdated, unavailable, lacked active practice components, and were not co-designed by people with dementia. In her clinical practice, Naomi had previously used a CPT program for CCD after TBI (TBI Express/TBIconneCT) because it was available and it had cognitive communication elements, with discrete activities that she then adapted for dementia. We wanted to fast-track progress and modify a current evidenced-based CPT program for families of people with dementia living at home. Our co-design process has involved people with dementia, communication partners, speech-language pathologists, multidisciplinary clinicians, and an advisory group that included aged-care providers. Through our co-production workshops we have created a draft, modified CPT for family members of people with dementia living in the community that takes the strong structure, videos, and active tasks of our TBI work, tailoring it to dementia.

Our third example of current CPT projects includes one that showcases our interdisciplinary efforts to enhance communication between eye-care professionals and clients who have dual visual and communication impairments. Sonia Lau’s PhD seeks to ensure people with dual impairments receive equitable, person-centred care that promotes autonomy and optimal outcomes. Our CPT literature review revealed no studies involving eye-care professionals, with most CPT programs using visual stimuli as a compensatory communication strategy. In a recent survey of orthoptists, some participants expressed a lack of training and resources to support communication in their practice (Lau et al., Citation2024). To understand the issue more deeply, our team conducted a focus group with orthoptists and speech-language pathologists based on a previous pilot study (Kavelin et al., Citation2024). We found that the both speech-language pathologists and orthoptists identified a lack of interdisciplinary knowledge, along with specific resources and training to assist them working with individuals with dual vison and communication disability. Sonia will trial our new, free 2-hour brief online CPT program, interact-ABI-lity (outlined below), to help student- and recently-graduated orthoptists increase their communication knowledge. The team will obtain feedback for any vision-specific adjustments to the program.

So, what is the future for CPT?

CPT has come a long way, but our future vision goes beyond specific studies and evidence to concrete indicators of societal communication access and inclusion. We want to see a society where every person who interacts with a person with communication support needs will be skilled in acknowledging and revealing communication competence of their loved one, friend, client, customer—this indeed would be a national policy. We will have audits that demonstrate high rates of training received through multiple-service delivery modes (some of which we don’t even have yet), with effective communication observed with people with communication disability. People with communication needs and their CPs will feel safe, confident, understood, respected, and connected, and will contribute to and lead the training in ways that suit them. And, finally, speech-language pathologists will be highly respected partners in communication access and inclusion. How do we get there? We believe through leveraging human-centred technology, co-design, and implementation science that we can make our way to that vision. We now explore the past, present, and future of CPT in technology, co-design, and implementation science.

Leveraging human-centred technology for digital health in CPT

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Citation2022), digital health is an umbrella term referring to a range of technologies that enable collection and sharing of a person’s health information. The categories of digital health could include telehealth and telemedicine via phone or video; mobile health, including SMS and apps; online eHealth, including treatment websites or apps; wearable devices, such as fitness trackers; and eHealth records. It also includes electronic prescribing (pharmacy apps); clinical technology, including a variety of speech-generating devices; as well as robotics and artificial intelligence (AI), for example, generative language models such as ChatGPT. Overall, to date, the digital health technology utilised in CPT interventions has been largely face-to-face delivery with audiovisual technology supports. Telehealth has been used in TBI and aphasia CPT, largely pushed more recently as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Online hosted programs range from a series of instructive videos hosted on a YouTube platform (e.g. MESSAGE), more online semi-active learning modules, as well as bespoke adaptations constructed on university learning-management systems. Our journey started in 2006 with the beginning of TBI Express, a face-to-face training program with a focus on promoting more successful and enjoyable conversations through training CPs of people with severe brain injury (e.g. parents, partners, and friends) to share, facilitate, and organise conversation with positive questioning approaches (Togher et al., Citation2013).

For TBI Express, the major technology we used, aside from audiovisual equipment, was a cassette tape that participants used to record home practice conversations and then bring to sessions. TBI Express (Togher et al., Citation2013) was 35 hours of training over 10 weeks, including weekly 2.5-hour group sessions with peer interaction, 45-minute one-to-one sessions with the speech-language pathologist, plus 30-minute taped home-practice sessions. Training included education, modelling, role-play, and practice, plus feedback and self-monitoring. The 35 hours of training was synchronous, that is the same time each week, and all participants needed to be in the same room. Our quantitative rating data showed that compared with controls, participants who attended together as a dyad improved either their interaction and participation for the people with TBI or improved their conversational supports and acknowledgment of competence for the CPs. Improvements were still present 6 months later (Togher et al., Citation2013). People with brain injury that came by themselves, without a partner, did not achieve the same outcomes. It seemed you really needed both CPs and people with TBI there to observe improvement in communication rating scales.

The humble tape recorders were a successful technological strategy at the time (being around 2007) as everyone could work them, they were cheap, participants did not need to charge them often or to have a smartphone, and they also introduced a new feedback mechanism to participants. One CP said, “it was a brilliant idea with the taping because playing back was just an incredible eye-opener for S” (Togher et al., Citation2012, p. 1568). TBI Express helped CPs recognise their own role in supporting communication and the CP and person with TBI expanded their community participation; for example, one participant with TBI said “friends are talking more to me now … I think it’s … because I’m listening and I’m commenting and not saying the wrong things … I tend to go to more places than what I was” (p. 1568). However, there were challenges as one CP remarked it “got a bit boring sometimes [for us] … to come down every week” (p. 1568) as they travelled 2 hours each way to the specialised brain injury unit. In CPT, we often need both client and CP to attend. So, we needed to reconsider ways we could reach more people both in regional and rural areas but also those in cities who could not afford travel time or who had work commitments.

To address this issue, Dr. Rachael Rietdijk commenced a PhD with Leanne Togher and myself (EP) in 2011 to create a telehealth version of TBI Express called TBIconneCT (Rietdijk et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). It had the same aims and content as TBI Express, but the delivery was over a mainstream telehealth program of the time (Skype), which we compared with a face-to-face delivery of TBIconneCT. Telehealth delivery has both advantages and disadvantages depending on our clients and their context, so we sought to assess the feasibility of telehealth as a delivery mode in this research. While group calls are now ubiquitous for group conversations, at the time group calls were still not stable in Skype and we focused on the 1:1 training. TBIconneCT was 15 hours overall with 1:1 sessions that went for about 1.5 hours with a speech-language pathologist but no peer or group interaction. For home practice, participants used screen capture to record conversations rather than tape recorders. The speech-language pathologists and participants needed to be available at the same time for sessions (synchronous), however, this time, the same location was not required, which meant people could participate from all over Australia. From ratings of video data, participants who received TBIconneCT via Skype or face-to-face had significantly improved conversations or better supported conversations compared with a historic control group (Rietdijk et al., Citation2020a). There was mostly no difference in self-rated communication skills between Skype and face-to-face groups (Rietdijk et al., Citation2020b). Teledelivery was considered acceptable to most participants primarily because it enabled access to intervention, as one participant said: “one of the big things for me, via the use of Skype was how it overcame the barrier of distance” (Rietdijk et al., Citation2022, p. 128). The presence of technological issues was noted, although these were considered mostly minor: “at times there were some technical issues,um, in a couple of the sessions—not a big deal, but you’ve just gotta then take a little bit of time to fix them, um, and then that sort of disrupts the flow of conversation and information” (p.129). Increased telehealth technology confidence was also observed with one participant saying, “a good side effect of that was, we started talking with my granddaughter on Skype” (p. 128).

TBIconneCT still required a lot of clinician time. So we sought to enable even further scale-up of CPT to more people by introducing an online self-directed prework component that the person with brain injury and their CP completed prior to sessions. This evolving version of TBI Express and TBIconneCT is called convers-ABI-lity, one program in the Social Brain Toolkit (https://abi-communication-lab.sydney.edu.au/social-brain-toolkit/; Avramović et al., Citation2023). The clinician could then review the client’s prework prior to or within the video-conferencing sessions that both the person with TBI and their CP attended. Time needed for prework was estimated to be about 30 minutes per session. Therefore, the clinician’s direct time is further reduced to between 7–10 hours, enabled by interactive technology with accessibility accommodations in the online program. You still do need to meet the clinician at the same time for the clinician-mediated sessions, but the prework could all be completed asynchronously in a different location and time prior to meeting with the clinician. This concept of engaging with learning materials prior to the session, and then prioritising clinician-guided active intervention within the session is called flipped learning (Bredow et al., Citation2021).

Technology can be highly suited to increasing the engagement of prework done by clients at home, through guided modules and video-based delivery. In convers-ABI-lity, there are short videos to simply introduce concepts that in previous programs clinicians would have talked through. The technology platform enables us to create interactive learning tasks, such as watching a video and using a slider to rate who is in control of the conversation. Then, the client can see the responses of other people who have also completed the task to get relative feedback. In their prework, clients are able to take introduced learning, such as metaphors, even further. They can reflect on their own interactions, choosing the description that fits them, such as, “we feel we are on opposite teams.” Clients can then enter their own metaphors in the text box and the clinician can review all this information before the sessions, so freeing clinicians for a more specialised, direct training role. The bespoke technology allows for clients to videorecord themselves and upload the video to the platform so the clinician can watch it and provide feedback, which the client can then see like a video replay. The platform has an automated analysis component of talking time, plus the speech-language pathologist can provide real-time, brief annotation so the client gets specific feedback tied to behaviour they can see. We are currently trialling it in a limited rollout and we hope, once we finalise the business model for the training program, that it will be widely available.

While we built convers-ABI-lity we knew, however, there was a need for both a shorter and more general program to educate people about communicating with someone with an acquired brain injury, especially support workers or people who are not yet ready or available for a more intensive program such as convers-ABI-lity. So, a shorter program called interact-ABI-lity (https://abi-communication-lab.sydney.edu.au/courses/interact-abi-lity/) was developed as the world’s first self-guided program to educate about different communication changes that happen after brain injury. They include areas of cognitive-communication impairments but also aphasia, dysarthria, and communicating with people who use augmentative and alternative communication. It is delivered online only and constructed with a WordPress website, so costs are lower. It is designed for many types of CPs, including family, friends, support workers, students, and practicing professionals, and people with acquired brain injury may themselves find it useful. It takes about 2 hours and you can do it anytime, anywhere, and at your own pace. As interact-ABI-lity is self-directed, there is no in-built time with a speech-language pathologist. However, it might be used as a program where a speech-language pathologist may recommend it but also add on other active practice elements, as well, for training. Remember the student health professionals in our aphasia training who said they wanted to see more people with lived experience of communication disability and with different communication impairments? The interact-ABI-lity program responds to that feedback. It contains stories from people with lived experience of communication disability headlining the program (see video https://youtu.be/rifkwsVyh00) and they provide suggestions for what helps in communicating with people with acquired brain injury. The program contains teaching about communication after acquired brain injury, as well as strategies for successful interactions, quizzes to support learning, and a certificate of completion to help make the achievement more concrete for organisations.

The future of technology in CPT

We are maximising technology to support human-facilitated CPT. But what about the future? Three thoughts.

Firstly, technology, machine learning, and large language models are changing the way we live and will offer increased opportunities to enhance training. For example, newer AI systems with more accurate instant language translation may enable our programs to be completed by people who speak languages other than English, of course with cultural adaptations where appropriate. Secondly, as authors of the Social Brain Toolkit, we will need to keep up with new technology advances and be responsive to their integration. We have been examining the potential of automated analysis systems of video conversations of people with TBI and their CPs beyond speaking time; however, this needs more work to be accurate. Thirdly, AI avatar systems will further develop for use in CPT. It is already happening now in simple formats. One brief example is from Dementia Australia, Centre for Dementia Learning, called Talk with TED (from https://dementialearning.org.au/technology/talk-with-ted/). It is centred on providing safe and respectful communication practice for support staff of people living with dementia. Talk with Ted shows the potential for AI to enhance our ability to practice communication as the future starts to become the present.

Leveraging co-design in CPT

Another key element of contemporary research, if we are to achieve our future inclusive communication vision, is the co-design of healthcare interventions. The UK group INVOLVE defines co-design or Patient & Public Involvement (PPI) as research carried out “with” or “by” members of the public, not just “to,” “about,” or “for” them (NIHR, 2021). And in more detail PPI, also called co-design or co-production, is “a collaborative model of research that includes stakeholders such as patients, the public, donors, clinicians, service providers, and policy makers. It is a sharing of power, with stakeholders and researchers working together to develop the agenda design and implement the research and interpret, disseminate, and implement the findings” (Redman et al., Citation2021, p. 1). The outcome is said to be more relevant and feasible, with greater implementation and uptake due to this end user involvement. In a recent review of 23 other reviews on healthcare co-design outcomes, Slattery et al. (Citation2020) found that co-design is rarely documented or evaluated empirically or experimentally. Co-design can have positive outcomes, including more relevant research questions and design of materials/assessments, positive emotional responses from end users, learning skills for research, and better researcher relationships with community, along with increased recruitment. However, there are perceived challenges and negative outcomes, which include co-design being highly time-, funding-, and resource-intensive, with tension between rigour and end user preferences and end user feelings of tokenistic involvement (Slattery et al., Citation2020).

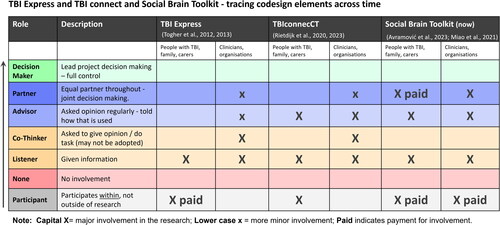

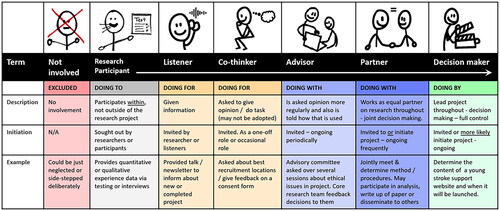

For our purposes here today, we consider co-design in terms of the level of involvement end users have had in research. Varying frameworks have been developed to conceptualise the degree of involvement of end users in research, as well as at which stages of the research. Here I focus on an adapted version of the overall involvement matrix of Smits et al. (Citation2020), which has roots in other frameworks such as Arnstein’s classic 1969 Ladder of Participation (Arnstein, Citation1969) and other similar models of involvement (Cook et al., Citation2017). The involvement matrix also used simple diagrams to represent involvement for consumers, which was especially attractive for illustrating different roles in research (https://www.kcrutrecht.nl/involvement-matrix/). We present a visual graphic of an adapted primarily involvement scale from this online resource, reproduced and adapted with kind permission of Associate Professor Marjolijn Ketelaar ().

Figure 2. Synthesised from the involvement matrix (https://www.kcrutrecht.nl/involvement-matrix/) adapted and used with kind permission from Associate Professor Marjolijn Ketelaar.

Firstly, we start with the Not Involved element, which is where end users are excluded or absent from any of the broader research processes. Then, Research Participant is the general foundation role for many end users, which is to be a participant in research. Participants participate within, but not outside of, the research data collection. They do not have input into decisions, methods, or analysis. Participants are sought out by researchers who are recruiting, and participants may provide quantitative or qualitative perspectives on an issue, service, or product. However, this is not generally considered involvement or co-design. From here, the Listener is really someone we are doing the research for. They are given information, often via an invited talk or newsletter, that informs them about an upcoming, current, or completed project. A Co-Thinker has some more involvement than a Listener, but we are still doing research for them and they may be asked to give a one-off opinion, such as asking stroke survivors who identify as culturally and linguistically diverse on best community recruitment pathways.

With the final three columns, we are in co-design territory, with roles of Advisor and Partner doing research with, not for, these end users. An Advisor is often invited to be on an advisory committee that meets periodically and is asked their opinions more regularly. They are also told how that opinion is used. A Partner is further involved frequently as an equal core member of the research team throughout, being invited to this role or initiating it. Partners may attend most meetings; provide input into methods, analyses, or results; and be involved in dissemination, such as authoring papers and presentations. The final involvement role is the Decision Maker, where end users initiate and lead the project with full control and researchers contribute as supporting team members. As Decision Makers, the endusers, for example, young stroke survivors, may determine the content of a young stroke support website and its launch date.

There have been some examples of co-design in CPT. The majority of this work was not formally written up in detail. Some studies in aphasia and dementia have small-scale co-design elements but the majority are not documented. We have attempted to trace our development of increasing involvement over time, based on our TBI-based research on the involvement matrix (see ).

From TBI Express to Social Brain Toolkit and convers-ABI-lity

For TBI Express in 2007–2009, involvement of people with CCD and TBI and their communication partners was as Participants (i.e. the bottom row of ), who we paid significant reimbursements for travel. People with lived experience of TBI were Listeners, too, as we tailored our dissemination on the progress and outcomes of the CPT research in community organisations, such as the Synapse Brain Injury newsletter, and consumer conferences. As Participants, you saw earlier that people with TBI and partners provided us feedback in a qualitative study that greatly helped shape our training and the manuals, so while we did get a lot of end user input this was not co-design as such. However, we were more engaged with clinicians in TBI Express, as myself (EP) and Rachael Rietdijk were clinicians running the project and we determined, with the research team, the direction, content, and research processes as well as dissemination. But the involvement was not with a cross-section of clinicians, hence the Xs are small and in brackets. Mostly clinicians were involved as Listeners through presentations and publications, but we engaged clinicians as Co-Thinkers to refine the TBI Express manuals based on their clinical experience. We also engaged with filmmakers to make six videos, using actors, on positive and less positive conversations based on participant scripts to maximise implementation. It was innovative, but still not really co-design.

If we look at TBIconneCT several years later, people with lived experience of CCD and TBI and their partners participated as Participants by receiving treatment and providing quantitative data from the measures of conversation and self-rated communication abilities, as well as detailed qualitative data on acceptability and feasibility. They were also Listeners, as we continued tailored dissemination with the brain-injury consumer organisations. But this time we attempted to include end users more formally in a small advisory committee that consisted of a man with brain injury, his mother, and several clinicians in public and private services. For clinicians, they were again involved as Listeners through our dissemination, Co-Thinkers to give specific feedback on manuals for telehealth, and as Advisors on the advisory group. It might be a bit dubious by now whether Rachael and I were still clinicians inputting at a partner level or on the dark, dastardly other side as researchers. The little x represents there was not a total absence of clinician input at this level, and we are edging more into co-design! While co-design is important, just participating in research is still critical—to build our evidence base and allow for participation in research in different roles as people are able! Rosey describes her participant role in TBIconneCT and its meaning for her.

Because my thoughts were scrambled, Jason diagnosed cognitive communication disorder. Emma suggested I take part in TBIconneCT. The ideas in my head were coherent to me, however when they came out they weren’t. I found people’s responses confusing and had great difficulty in moderating my temper when they didn’t understand what I thought were rational concepts. My family and friends saw this anger as part of the loss of my brain-speech filter. I had to learn to filter my thoughts before I spoke. The filter that we all learn as infants, then take for granted as we get older, didn’t just reappear. Apart from the temper displays, I said things that were totally “out there.” They seemed harsh, even to people close to me. I still have trouble with this. Hence, my joining TBIconneCT, of which I was a face-to-face participant, and Inez was my communication partner. A therapist came weekly and did exercises. Our homework was to video a conversation between Inez and me. After a couple of weeks, my daughter questioned the worth of the program, saying she thought it was too basic for me and I didn’t need it. So, I had to work out what I’d gained from the course and I realised she was wrong—it was giving me a lot of confidence in coping with the outside world. Up to that point, I was confident with my family because we were close but I avoided talking on the phone, to people I didn’t know, to friends who were not close, or to anyone at night—even family. She hadn’t seen what was lacking in my speech abilities in the wider world. As soon as I said it gave me confidence, she was sold. Inez learnt how to support me in conversations; she said she learnt when to be patient and give me time to think, when to jump in and help, and how to prompt me to help me find what was in my head before expressing it. In her words: “it was as much as about learning those skills as a journey of understanding how mum’s brain and communication now worked.” On a personal level, TBIconneCT gave me a lot. I understood it to be part of Rachel Rietdijk’s PhD thesis so was pleased to be a small part of that. Some other participants were doing it online but I was happy to do it face-to-face as I wasn’t sure I’d be able to handle the technology. Michelle, the therapist, gave me a lot of ideas. They seemed obvious after she’d said them but I needed to have them pointed out; things such as writing a script before ringing anyone on the phone. I only had to do this a few times before my confidence returned, as I realised the people I was talking to couldn’t compare what I sounded like to “the old Rosey.” Friends and family made allowances for me.

For the Social Brain Toolkit, in the last two columns of , we definitely stepped it up several notches, with a variety of end users and experts involved from the planning and grant phase right the way through to the dissemination phase. Additionally, some 40 people, such as Rosey, were involved periodically in different elements of the development of the toolkit. People with lived experience of CCD and brain injury and their communication partners were involved as Participants in giving their opinions about the development of convers-ABI-lity and interact-ABI-lity as online modular programs (Avramović et al., Citation2023). They were also involved and paid at recommended volunteer rates for their input into key implementation challenges and potential solutions for these new online CPT tools (Miao et al., Citation2022). Several people with TBI and their communication partners, not just one, were part of our advisory group. One advisory group member advocated for the Social Brain Toolkit to be widely distributed and paid for by the NSW state government by writing to his local minister, eventually receiving an encouraging reply from the health minister at the time, Brad Hazzard.

Several other Social Brain Toolkit implementation participants then went on to occupy the Partner role for one aspect of the project and contributed to the publication (Miao et al., Citation2022). Clinicians were also participants in many of the same projects, from designing the online CPT modules to being paid to trial convers-ABI-lity in full as clinicians, providing the program in their practice with clients. They were part of the advisory group and some clinicians also had input into key implementation challenges and potential solutions and, like people with lived experience, co-authored publications in the dissemination of the implementation studies of the project. There were many other stakeholders and endusers involved and I’ll outline some of these critical partnerships later. Overall, you can see a growing increase in end user involvement within our research, not yet making full Partner or Decision Maker all the time but a definite positive increase. However, remember that this was funded research, and such level of involvement could be challenging for small PhD studies not integrated into such projects. In the end, this higher level of involvement we reached is now described by Rosey and she speaks about her experience as a Partner in co-design and dissemination.

Being a participant in TBIconneCT and a guest lecturer led to me becoming a co-designer of the Social Brain Toolkit. Not only was I a participant, I offered to proofread journal articles, which I saw as the meeting of my professional skills and my personal experience of having a TBI. My communication partner was Marie, a friend who is an academic in education. Once again, I felt fulfilled: I was to be part of a study where people with first-hand experience not only contributed, but steered the outcome of the research. We helped create a toolkit that can be used by people who acquire a brain injury and it can be used when they need it because it is online. Some participants said they had had to wait for 6 months or more before they got into a speech therapy program. Communication partners are vital to helping brain-injured people communicate. They need easy access, so building an online version (convers-ABI-lity) along with a short version (interact-ABI-lity) maximises opportunities for partners to get the training that is essential. This should happen in the early days. As time went on, I transcribed what was said in the discussion groups and proofread the articles. I am an author on research papers along with other people with lived experience, clinicians, and researchers. I saw this as a contribution to therapists who had helped in my recovery, therefore it was a small way to give back. I only understood the gravity of my contribution when the Social Brain Toolkit was launched in 2022. It’s an extraordinary resource that gets to the heart of the situation—it focuses on people who cannot communicate and their close others to remedy this situation.

Our co-design partnerships

I sat down to reflect on all our partnerships over this journey—there are many and they are diverse! For the Social Brain Toolkit, we are increasing partnerships with people with lived experience and their family and friends, as well as speech-language pathologists but also other multidisciplinary clinicians. The Social Brain Toolkit has partnered with Brain Injury Australia from grant to dissemination and liaised with Synapse, the brain injury support organisation. Funders and insurance partners, such as iCare, have been involved, including in early planning phases through to workshops to maximise the success of the research and steering group meetings. We have partnered throughout with Changineers, a social enterprise with expertise in creating digital education solutions and pedagogy. They created our platform for convers-ABI-lity with innovative video-based elements. We also had multidisciplinary digital health experts contribute. We have engaged with health services, especially private clinicians and people with expertise in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). This scheme is a national Australian insurance scheme that provides individualised funding for people with significant, permanent disability. Together we created an NDIS template documentation with the aim to improve implementation of convers-ABI-lity. Finally, but not least, forays into digital health services and products require keen consideration of the value proposition of the program, plus a business model to enable the CPT to be sustainable with regular technological and evidence upkeep and modification. In fact, ironically, we are actually Participants ourselves in research about product commercialisation by the University of Sydney Business School, who sit in on all our steering meetings. The metaparticipation is fun and interesting!

There are many clinical and research teams striving to aim for greater involvement of people with lived experience and other stakeholders in research and services. We need funding to do it well and with true co-design philosophy, and to consider discrete Co-Thinker roles for people who do not wish to/cannot be involved too much—we need to be realistic about the time. As Hersh et al. (Citation2021) say “conducting PPI [co-design] in a meaningful way can be time-consuming, particularly when working with people with aphasia … and, therefore, researchers must believe the benefits of PPI are worth investing the extra time needed” (Hersh et al., Citation2021, p.10). Partnerships will be built more into formal organisational structures in the future.

The future of CPT co-design

The future of co-design, though, is built on the past and our relationships we establish over time. Here Rosey speaks about her ongoing partnership with me, and why that has been important.

What was also instrumental was Emma asking me to speak to her students a year after I’d first done it. It’s impossible to quantify how much confidence this restored. My life had completely fallen apart in 2016 and it took the bike accident to make me realise how confident I had been. I’d taken for granted that I was a positive, assured, independent person. When those things are instantly removed, it takes a lot of incremental steps to restore any semblance of them. I am grateful that I’ve been speaking to Emma’s students for 6 years. Their questions are fascinating. I’m so used to having a TBI that there are things I assume people will know—it’s good to be reminded that not everyone has the knowledge of what happens with a traumatic brain injury. So another upside of the accident is that I have become a guest lecturer to more than 450 university students. Emma received feedback from them last year and passed on the relevant bits. This was a huge dose of positive feedback—the students were glowing in their praise of having people with first-hand experience of brain injury tell them what it’s like.

Implementation and CPT

All the discussed information above is only as good as our implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation is essentially the process of putting recommendations into professional practice, but it is definitely not simple for clinicians in a challenging, complex health system. The evidence-to-practice gap is critical as we know it takes a long time for knowledge to get into practice, with 17 years being the often quoted but potentially oversimplified number (Hanney et al., Citation2015). However, we also know that health outcomes can depend on best practice. For example, hospitals that do provide evidence-based stroke management get significantly better health and recovery outcomes for their clients (Hubbard et al., Citation2012), and we also know from above that CPT is recommended and has positive outcomes.

The question is, then, are we doing CPT? Most past studies are self-reported surveys as opposed to more rigorous audits, but many show less than 50% of clinicians report providing evidence-based CPT in aphasia (e.g. Chang et al., Citation2018; Johansson et al., Citation2011) and TBI populations (Behn et al., Citation2020), with no recent data for dementia with the exception of primary progressive aphasia where 85% of clinicians report providing CPT (Volkmer et al., Citation2019). Use of published programs was low in stroke and TBI, with only up to 20% of clinicians using published CPT programs and few with fidelity (Behn et al., Citation2020; Chang et al., Citation2018).

Why are we struggling and what helps and hinders our CPT implementation? Best practice in implementation science research is that we establish the local barriers to implementation and then we target them with evidenced-based strategies for behaviour change (Smith et al., Citation2020). Barriers could exist at the clinician level (e.g. increasing their CPT skills), the intervention itself (e.g. it does not fit into our workflow), the inner system/context (e.g. a hospital’s resource or culture), or the outer context (e.g. community awareness, policy setting, even COVID-19). We use the refined Theoretical Domains Framework of Mitchie et al. (see Cane et al., Citation2012), based on psychological behaviour change theories, which consists of 14 domains that can help or hinder implementation. Here are some examples from our survey studies and recent systematic synthesis of aphasia research (Behn et al., Citation2020; Chang et al., Citation2018; Shrubsole et al., Citation2023). The most frequently cited domain is difficulties with Environmental Context and Resources, which may affect our opportunity to do CPT. The reasons can include: that it is hard to access CPs, such as family; clinicians lack time or easily accessible CPT resources/materials; clinicians may have competing tasks/pressures; the fast-paced nature of the acute setting can be hard; the timing of offering CPT, when people are ready for it, after a big event like an acquired brain injury is difficult; or there may be a lack of supportive organisational culture and a lack of funding/reimbursement. On top of that, there are often no policies in workplaces to facilitate the CPT nor systems to monitor if it is being done (Behn et al., Citation2020; Chang et al., Citation2018). Facilitators of what helps are often the absence of those barriers, such as good access to family or having training materials available, which is why our research team have always published our programs in detailed manuals and created supporting videos to assist implementation. But the key facilitators are often what is inside us as speech-language pathologists. That is, that we believe CPT is our role, that clients will be able to communicate more successfully following CPT, and we often believe that providing CPT is rewarding (Behn et al., Citation2020; Chang et al., Citation2018; Shrubsole et al., Citation2023).

We know there is some preliminary feasibility of implementing CPT in stroke, TBI, and dementia (Douglas & MacPherson, Citation2021; Nielsen et al., Citation2023; Shrubsole et al., Citation2021), with some studies using tailored implementation strategies to locally-identified barriers. The research is mostly in healthcare settings and with unfamiliar CPs, such as staff. Dr. Kirstine Shrubsole and team (Shrubsole et al., Citation2021) found that implementation readiness can vary over time and that it is iterative, needing several rounds of implementation, review, and planning to increase behaviour change. Few CPT studies really look at longer-term sustainability, which is the real test of implementation. There are many studies currently occurring where we are working hard to reduce the implementation gap. More on that below.

But a slight diversion. I had an interesting question on implementation on my sabbatical trip with Professor Ian Graham, an implementation scientist in Canada. We were talking about CPT implementation, and he said, “well, how do you know if the clinician “passes” in providing CPT? How do you know if the communication partner then “passes” using support communication supports? If we were to audit for it, what should we see written in the file, if it is?” Interesting. I sketched out what I thought were the invisible and more obvious larger elements of CPT (see ) and this was handy because in my implementation work in CPT with Dr. Kirstine Shrubsole, we had to work out a way to determine if evidence-based CPT was being done beyond a “yes/no” answer, which is harder than you think.

The work of O’Rourke et al. (Citation2018), cited above, and data in systematic reviews have provided us with some ideas of what may be important CPT elements from successful CPT studies. However, it is still an area for research to investigate further. Therefore, in our recent Stroke Foundation-funded CPT implementation study for families of people with aphasia (Shrubsole et al., Citation2023), CPT was considered “done” if there was: (a) an offer of CPT, if appropriate; (b) a CPT assessment, just like we would in naming treatment to show change; and (c) CPT that consisted of demonstration, practice, and feedback, with (d) a follow-up assessment, if possible. We were using a file audit to determine whether implementation had occurred, so that meant that all this had to be documented in clinical files as well. We conducted a pilot, pragmatic step-wedge cluster randomised control trial (cRCT). Basically, we had three services and we randomised when they would get their staggered start of a tailored implementation behaviour change package to increase use of aphasia CPT with families. We wanted to see if our CPT implementation approach was feasible and potentially effective. Due to small patient and site numbers in this pilot study, complicated by COVID-19, it was not possible to calculate an intervention effect, but there was an increase in the proportion of carers being offered CPT after the intervention. Staff focus groups revealed challenges to implementing CPT, such as reduced patient and carer readiness to receive CPT, discomfort being videorecorded, and organisational factors such as workforce barriers and lack of access to carers due to COVID-19 restrictions. However, staff were positive about CPT being regarded more highly within their work environment and reported that CPT was more consistently provided.

The future of CPT implementation

There are many avenues to consider for future implementation of CPT and it is still an embryonic and very challenging field for CPT research. We will need to influence systems and policy and policy-makers at a national level if we are to maximise best practice. One issue that may affect how we are able to scale our CPT research and implementation has been raised in our previous study on provision of CPT to multidisciplinary student health professionals (Power et al., Citation2023). We included self-reporting to measure changes in knowledge of aphasia and strategies, as well as attitude of CPs. But we did not directly assess each participant’s ability to demonstrate all CPT skills in a conversation with a person with aphasia. In considering the limitations of our self-report measure, we also had to consider what resources it would have taken to assess the skills of every CP directly, including people with aphasia. We were able to highlight issues around the sustainability of resourcing to directly assess CPs. We also considered the feasibility and sustainability of the direct involvement of people with lived experience of aphasia in not only the CPT training element, but also in baseline and outcome assessment to establish CPs’ skills in supporting conversation. In our study, we had 236 participants commence. While some did not complete all elements of the study, we had to be prepared that they would have. To enable us to assess their skills in this research, the 236 participants would need four assessment conversations with people with aphasia, as well as people with aphasia having practice conversation with students within the training. This scenario would mean 944 conversation samples to rate, equating to over 315 hours, some needing to be rated by two people. People with aphasia would need to be available for 300 hours’ worth of time, plus any carers. We would then need to add time to both of these for training, debriefing, and administration. As my colleague Dr. Lucette Lanyon said, “that’s a workforce,” and I believe based on the co-design principles outlined above, one that should be paid, like simulated patients would be. It is very, very resource-intensive. And so, back to the technology-based ideas for increasing use of immersive AI, avatar-based simulations for training and assessment, such as in Talk with Ted and automated video-based AI analysis techniques. We need to work out how to do that, or we need to have a self-report assessment measure that we have determined is highly correlated and predictive of communication supports skills so we could use that in place of rated conversations. A final aspect of future implementation needs is having a ready synthesis of evidence-based knowledge to promote best practice and providing that information to clinicians in a one-stop shop. Currently, I am leading an international group of CPT clinical researchers to create the CPT Central website that will be available later in 2024 and have all key evidence-based knowledge about the major CPT assessments, interventions, and implementation strategies across the three main neurological populations.

Key messages for CPT

There is, currently, a relatively high level of evidence for CPT, recommended in clinical practice guidelines (CPG) for stroke, brain injury, and dementia with programs for each population available or emerging. This evidence base reflects decades of research and clinical practice centring on reflecting, respecting, and responding. We have high aspirations for a vision of communication access and inclusion relating to CPT for all people with communication support needs and their communication partners. Even if we do not work purely in adult neurological practice, we all will likely have a vested interest in our own CPT success and vision for the future and for paediatric practice where we also train communication partners. We should be real though—CPT can clearly be challenging to implement; the research can be hard to do and translating that into practice for clinicians can be demanding. CPT does not reach everyone by a long shot, and we know this can affect people very badly. However, I (EP) am confident we can continue to leverage technology now and in the future; we can co-design with critical interdisciplinary, consumer, and organisational partnerships and do high-level advocacy. We can enhance individual and system-based implementation and drive changes in health and society. It will take persistence and creative solutions we have not even thought of yet, but we can strive towards a future of a communicatively inclusive and skilled society. On this, I leave the last words to Rosey:

It was only in writing this talk that I’ve understood the chasm I’ve crossed—where I’ve come from and where I am now. I’ve progressed from a paralysed, whisper-quiet person to a participant in a speech-therapy program, to a guest lecturer, then a co-designer of an intervention, and co-author on published research papers. I saw each part as contributing to those who had helped me, but I am so proud that my contribution will help others. I am one cog in a very large, very vital wheel. As speech therapists, you hold the key to the brain-injured person’s locked-in, non-verbal world. No matter how hard the physical or medical environment, you can train their close others to help them communicate by understanding what’s going on in the brain-injured person’s head, and how they can help them communicate with the wider world. So, please, keep striving for best practice in your work with brain-injured people; teach their communication partners how to help them unlock their mind. Speech therapists were critical in my recovery and you can be the same vital link in a brain-injured person’s life.

Power and Morrow 2024 suppl file.docx

Download MS Word (17.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The knowledge shared today is a product of long-term relationships with many research colleagues, clinicians, students, and people with lived experience of communication disability.

Declaration of interest

EP was paid for the Keynote presentation and to produce this article. EP is an author of TBI Express, TBI Connect and Social Brain Toolkit programs, where she currently does not receive monetary reward, but this may change into the future. RM acknowledges she was paid via gift vouchers for her participation in TBI Connect as a research participant.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arnstein, S. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Digital health. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/digital-health

- Avramović, P., Rietdijk, R., Kenny, B., Power, E., & Togher, L. (2023). Developing convers-ABI-lity: Using a collaborative approach to create a digital health intervention for conversation skills after brain injury. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e45240. https://doi.org/10.2196/45240

- Bartlett, G., Blais, R., Tamblyn, R., Clermont, R. J., & MacGibbon, B. (2008). Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L'Association Medicale Canadienne, 178(12), 1555–1562. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.070690

- Beckley, F., Best, W., Johnson, F., Edwards, S., Maxim, J., & Beeke, S. (2013). Conversation therapy for agrammatism: Exploring the therapeutic process of engagement and learning by a person with aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(2), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00204.x

- Beeke, S., Sirman, N., Beckley, F., Maxim, J., Edwards, S., Swinburn, K., Best, W. (2013). Better conversations with aphasia: An e-learning resource. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/short-courses/search-courses/better-conversations-aphasia-e-learning-resource

- Behn, N., Francis, J. J., Power, E., Hatch, E., & Hilari, K. (2020). Communication partner training in traumatic brain injury: A UK survey of speech and language therapists’ clinical practice. Brain Injury, 34(7), 934–944. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1763465

- Bourhis, R., & Giles, H. (1977). The language of intergroup distinctiveness. In H. Giles (Ed.), Language, ethnicity, and intergroup relations (pp. 119–135). Academic Press.

- Boylstein, C., & Hayes, J. (2012). Reconstructing marital closeness while caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s. Journal of Family Issues, 33(5), 584–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11416449

- Bredow, C. A., Roehling, P. V., Knorp, A. J., & Sweet, A. M. (2021). To flip or not to flip? A meta-analysis of the efficacy of flipped learning in higher education. Review of Educational Research, 91(6), 878–918. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211019122

- Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

- Carragher, M., Steel, G., O'Halloran, R., Torabi, T., Johnson, H., Taylor, N. F., & Rose, M. (2021). Aphasia disrupts usual care: the stroke team's perceptions of delivering healthcare to patients with aphasia. Disability and rehabilitation, 43(21), 3003–3014. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1722264

- Chang, H. F., Power, E., O'Halloran, R., & Foster, A. (2018). Stroke communication partner training: A national survey of 122 clinicians on current practice patterns and perceived implementation barriers and facilitators. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(6), 1094–1109. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12421

- Christensen, I., Power, E., Togher, L., & Norup, A. (2023). Communication is not exactly my field, but it is still my area of work: Staff and managers’ experiences of communication with people with traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 32(2S), 827–847. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJSLP-22-00074

- Clancy, L., Povey, R., & Rodham, K. (2020). Living in a foreign country: Experiences of staff-patient communication in inpatient stroke settings for people with post-stroke aphasia and those supporting them. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(3), 324–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1497716

- Connect the Communication Disability Network. (2007). Conversation Partner Toolkit, Tool 1.16.

- Cook, T., Boote, J., Buckley, N., Vougioukalou, S., & Wright, M. (2017). Accessing participatory research impact and legacy: Developing the evidence base for participatory approaches in health research. Educational Action Research, 25(4), 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2017.1326964

- Douglas, N. F., & MacPherson, M. K. (2021). Positive changes certified nursing assistants’ communication behaviors with people with dementia: Feasibility of a coaching strategy. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(1), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00065

- Folder, N., Power, E., Rietdijk, R., Christensen, I., Togher, L., & Parker, D. (2024). The effectiveness and characteristics of communication partner training programs for families of people with dementia: A systematic review. Gerontologist, 64(4), gnad095. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnad095

- Hanney, S. R., Castle-Clarke, S., Grant, J., Guthrie, S., Henshall, C., Mestre-Ferrandiz, J., Pistollato, M., Pollitt, A., Sussex, J., & Wooding, S. (2015). How long does biomedical research take? Studying the time taken between biomedical and health research and its translation into products, policy, and practice. Health Research Policy and Systems, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-13-1

- Harmon, T. G. (2020). Everyday communication challenges in aphasia: Descriptions of experiences and coping strategies. Aphasiology, 34(10), 1270–1290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1752906

- Hemsley, B., Werninck, M., & Worrall, L. (2013). That really shouldn’t have happened”: People with aphasia and their spouses narrate adverse events in hospital. Aphasiology, 27(6), 706–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2012.748181

- Hersh, D., Godecke, E., Armstrong, E., Ciccone, N., & Bernhardt, J. (2016). Ward talk”: Nurses’ interaction with people with and without aphasia in the very early period poststroke. Aphasiology, 30(5), 609–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2014.933520

- Hersh, D., Israel, M., & Shiggins, C. (2021). The ethics of patient and public involvement across the research process: Towards partnership with people with aphasia. Aphasiology, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2021.1896870

- Hubbard, I. J., Harris, D., Kilkenny, M. F., Faux, S. G., Pollack, M. R., & Cadilhac, D. A. (2012). Adherence to clinical guidelines improves patient outcomes in Australian audit of stroke rehabilitation practice. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(6), 965–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.01.011

- Johansson, M. B., Carlsson, M., & Sonnander, K. (2011). Working with families of persons with aphasia: A survey of Swedish speech and language pathologists. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.486465

- Kagan, A. (1998). Supported conversation for adults with aphasia: Methods and resources for training conversation partners. Aphasiology, 12(9), 816–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687039808249575

- Kavelin, M., Power, E., & French, A. (2024). He just looked like he couldn’t learn, whereas he just couldn’t see”: Exploring clinician experiences working with people who have co-occurring communication and visual impairment. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2024.2309741

- Lau, S., Power, E., & French, A. (2024). Perspectives of orthoptists working with patients with communication impairments. British and Irish Orthoptic Journal, 20(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.22599/bioj.321

- Lock, S., Wilkinson, R., & Bryan, K. (2001). SPPARC: Supporting partners of people with aphasia in relationships and conversations. Winslow Press.

- McLellan, K. M., McCann, C. M., Worrall, L. E., & Harwood, M. L. N. (2014). For Māori, language is precious. And without it we are a bit lost”: Māori experiences of aphasia. Aphasiology, 28(4), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.845740

- Miao, M., Power, E., Rietdijk, R., Debono, D., Brunner, M., Salomon, A., Mcculloch, B., Wright, M. R., Welsh, M., Tremblay, B., Rixon, C., Williams, L., Morrow, R., Evain, J.-C., & Togher, L. (2022). Coproducing knowledge of the implementation of complex digital health interventions for adults with acquired brain injury and their communication partners: Protocol for a mixed methods study. JMIR Research Protocols, 11(1), e35080. https://doi.org/10.2196/35080

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. (2021). Briefing notes for researchers. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/briefing-notes-for-researchers-public-involvement-in-nhs-health-and-social-care-research/27371

- NHMRC Partnership Centre for Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People – Guideline Adaptation Committee. (2016). Clinical practice guidelines and principles of care for people with dementia. Author. https://cdpc.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Dementia-Guideline-Recommendations-WEB-version.pdf

- Nickbakht, M., Angwin, A. J., Cheng, B. B. Y., Liddle, J., Worthy, P., Wiles, J. H., Angus, D., & Wallace, S. J. (2023). Putting "the broken bits together": A qualitative exploration of the impact of communication changes in dementia. Journal of Communication Disorders, 101, 106294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2022.106294

- Nielsen, A. I., Jensen, L. R., & Power, E. (2023). Meeting the confused patient with confidence: Perceived benefits of communication partner training in subacute TBI. Brain Injury, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2022.2158224

- Nielsen, A. I., Power, E., & Jensen, L. R. (2020). Communication with patients in post-traumatic confusional state: Perception of rehabilitation staff. Brain Injury, 34(4), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1725839