ABSTRACT

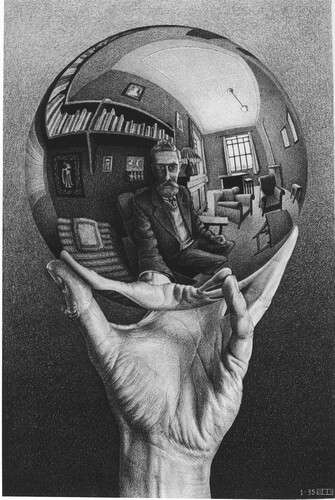

British and Irish practical theology has been exercised in its recent history about the apparent elusiveness of the Bible within practical theology. In this essay, I want to address how we might now move beyond the pathology of Bible and practical theology, to thinking about the ways in which the Bible may function normatively in practical theology. This was prompted by teaching reflexivity in a professional doctorate programme and noting the almost complete absence of the Bible from the literature on this topic. How is it that a book of mirrors and examinations, vigilance and virtue, powers and unveilings has been excluded from our reflexivity curriculum? As a case study of the Bible’s normativity, and inspired by using M. C. Escher mirrors in the classroom, this essay looks into five biblical mirrors to engage in a practical theological reading of Scripture that speaks to reflexivity and its conundrums. Through a variety of normative moves, I argue that the mirrors offer epistemological and ontological insights that show reflexivity to be a practice with its own theological integrity. This theological reflexivity is then worked out in a number of actions for the classroom and beyond.

Introduction

The issues at the heart of this essay arose from my experience of teaching professional doctorate (DTh) students at the University of Roehampton from the Autumn of 2018 onwards.Footnote1 The module was ‘Practical Theology: Advanced Methods and Approaches’; the topic was reflexivity; the resources were books and articles by leading practical theologians. What struck me when engaging with these resources was their lack of reference to the Bible. Actually, I did not notice this immediately, but it was when students were invited to reflect on Scripture in relation to theological reflection more broadly that these resonances between Scripture and reflexivity became apparent. This was a sign, perhaps, that I had become accustomed to not finding Scripture in such practical theological discussions.

One might ask why should I expect to find the Bible in a discussion of reflexivity? What does a postmodern epistemological practice have to do with the premodern implicit epistemologies of the Bible? What does Paris have to do with Jerusalem or Corinth? Will it not be an anachronistic enquiry? Am I asking questions of the Bible that the Bible does not want to answer? Or will it be a case of what I was warned against at the evangelical theological college I attended? That is, to take a detour through Scripture to eventually say what I was going to say anyway. I will leave the reader to make up their own mind.

On reflexivity, at first or even second glance, the Bible appears to be a fruitful source. It is a book of mirrors and examinations, of vigilance and virtue, of powers and unveilings that has a strong affinity with the reflexive impulse of practical theologians. For a theological discipline where reflexivity is such a fundamental characteristic, it would be odd indeed to ignore the voices of Scripture when thinking about reflexivity. This of course raises issues about the Bible’s normativity in practical theology, particularly the ways in which normativity is construed – a point I will return to later in the essay.

Reflexivity and the Bible is a case study of the larger issue of how the Bible is engaged in practical theology. Two initiatives in particular have been significant for this issue within the British context. The Bible in Pastoral Practice project ran in various forms from 2000–2005 as a joint venture of Cardiff University and Bible Society. The project brought together biblical scholars and practical theologians to address the ‘chasm’ between biblical studies and practical theology around the focal topic of pastoral practice (Ballard and Holmes Citation2005, xiv), subsequently disseminated through a series of publications (Dickson Citation2007; Ballard and Holmes Citation2005; Oliver Citation2006; Pattison, Cooling, and Cooling Citation2007; see also Ballard Citation2011). A special issue of Contact (the precursor to Practical Theology) entitled ‘The Bible as Pastor’, and guest edited by Paul Ballard, spoke similarly of ‘a deep uneasiness about the apparent gulf’ between biblical scholars and practical theologians to date. It also noted, however, an encouraging convergence between biblical scholars who wanted to ‘explore fresh ways of allowing the Bible to act as Scripture in the life of the Church’ and practical theologians wanting to ‘anchor pastoral practice and theory more firmly on theological foundations’ (Ballard Citation2006, 2). A second initiative was the formation in 2011 of the British and Irish Association for Practical Theology (BIAPT) Bible and practical theology special interest group, convened by myself and (at the time) Zoë Bennett.Footnote2 In some continuity with the Bible in Pastoral Practice project, the group’s first symposium in 2012 brought together practical theologians and some biblical scholars from different church backgrounds and traditions, who shared an unease about the uneasy relationship between the Bible and practical theology (Graham, Walton, and Ward Citation2005, 7). Some described the Bible’s place in practical theology as ‘the elephant in the room’ or even as the ‘the unwanted elephant in the room’.Footnote3 The group sought then and in future meetings to open up critical issues in the Bible / practical theology interface, with the aim of making a contribution to an ‘ongoing movement of rapprochement’ (Bennett Citation2013, 7). A number of publications informed by this group do just that (e.g. Bennett Citation2013; Briggs Citation2015; Briggs and Bennett Citation2014; Rogers Citation2016; Whipp Citation2012).

With some justification, then, a narrative of the ‘elusiveness of the Bible in practical theology’ has been developed (Ballard Citation2011; cf. Cartledge Citation2013). There is a danger, however, that such a narrative becomes self-perpetuating. There have been ‘green shoots’ of Bible engagement in a variety of ways through BIAPT conference keynote speakers and contributors, alongside the ongoing activity of the special interest group, as others have also noted (e.g. Rooms and Bennett Citation2019, 27, 154–5). Furthermore, searching the Practical Theology / Contact archive reveals more articles engaging the Bible than might be expected from this narrative. A simple search conducted in March 2023 found 24 articles and 9 book reviews with ‘Bible’ or ‘Scripture’ in the title or keywords, all of which were published from 2006 onwards, which may also say something about the influence of the two initiatives described above.Footnote4 Consequently, I suggest it is now time to move beyond this phase of pathologising Bible and practical theology to risk engaging with Scripture as practical theologians. This is my attempt here.

Reflexivity explored

Many types of reflexivity have been proposed (e.g. Finlay Citation2003, 6; Lynch Citation2000, 27f). Here I intend to explore reflexivity as it has typically been characterised within practical theology. Such reflexivity appears to have its roots in the postmodern turn of the late twentieth century, emerging from critiques of objectivist research paradigms in the social sciences in particular (Finlay Citation2003, 4; Robben Citation2012, 513). As a field that has borrowed heavily from the social sciences, reflexivity has now become a fundamental aspect of practical theology. It features in practical theology programme criteria, in most introductions to the subject and is lauded as a sign of high quality practical theological work.

Reflexivity can be characterised as follows. At its heart, reflexivity is about recognising my subjectivity as a researcher as a situated interpreter of contexts and practices, as someone embedded in wider social and power structures. It is about recognising the co-creation of knowledge between researcher and research participants and is a move towards greater openness and honesty about this dynamic (Rogers Citation2016, 28). Often confused with reflection by students, it is sometimes distinguished by the direction of its gaze – back upon oneself and the structures one inhabits (cf. Bennett et al. Citation2018, 40).

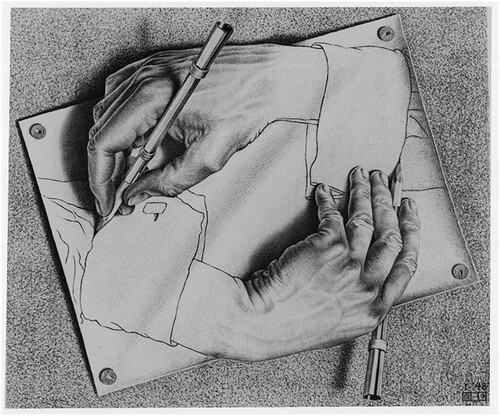

Rooting this exploration in my classroom context, my principal focus was on teaching reflexivity for qualitative fieldwork projects. An initial exercise was to look at two images to provoke discussion on the nature of reflexivity, both of which were sourced from a Google search on ‘reflexivity’ and portrayed different forms of mirroring ourselves (see and ). Unknown to me at the time, these images have often been associated with forms of reflexivity (Goldstein Citation1996; Lynch Citation2000, 28, 48). A key text for consideration was Jaco Dreyer’s chapter in Conundrums in Practical Theology, where he reflects on his role as a practical theologian in the South African context (Citation2016), utilising Pierre Bourdieu’s three dimensions of epistemic reflexivity or ‘bias’ (Dreyer Citation2016, 99f; Wacquant Citation1992, 39f). Other set texts on reflexivity were by Natalie Wigg-Stevenson (Citation2013) and Bennett et al. (Citation2018: Ch. 2).

Prompted by Dreyer’s careful reflexive account and to address the conundrum he identifies, I offer a much less careful reflexive moment of my own. I am an evangelical practical theologian based at a public university in the UK where my teaching is with students engaged in a wide variety of Christian ministries. I have been a computer programmer, cross-cultural missionary in East Africa, Maths teacher and a researcher for Bible Society. The theological institutions I have studied at and worked at have had a significant influence on my theological formation, as has BIAPT; I belong to a charismatic community church; and the Bible forms a core part of my spirituality. I am committed to a critical pluralism of hermeneutical approaches, as well as to a critical realist position of epistemic relativism, ontological realism and judgemental rationality. I am from lower middle class origins, state-school educated, male, white, middle-aged and married with three children. And a cat.

In offering this condensed account as an exaggeration of reflexivity in some practical theology writing (when included), I cannot avoid two conclusions. Firstly, agreeing with Kate Fox, it would seem that such an account is often implicitly offered as a ‘protective mantra’ (Citation2004), in the sense that the reflexivity bit is done and will now ward off any critique of my positionality. Secondly, it is entirely my choice as to how vulnerable or great or exhaustive or otherwise I make myself in such an account. Beyond selectivity there is also ignorance – I may simply not be aware of my own ‘biases’ and locations, and their significance. Dreyer draws out this conundrum in his chapter by arguing that ‘reflexivity cannot heal the “epistemological wound” of researcher subjectivity, bias, and positionality’. Situated in ‘our horizons of understanding, we will never be able to escape from our subjectivities’, since we do not have a ‘God’s eye view’. Dreyer uses the image of a mirage in a desert to illustrate the illusion of thinking you can ‘objectify your subjectivity’ (Citation2016, 92).

Engaging scripture

With this conundrum in mind, I now want to reflect on what Scripture offers for our practices of reflexivity. How does the Bible invite reflexivity from its readers and in what ways does it enrich and/or challenge how we go about it? A few others have already started down this road, so Elaine Graham, Heather Walton and Frances Ward begin their account of ‘theology by heart’ through reflecting briefly on Psa. 139.13–18. They observe that the passage links ‘knowledge of the God of the heavens’ with ‘the inward working of the interior life’ – such an inward movement illustrates aspects of reflexivity where the metaphor of a book (v16) suggests that ‘the self can be read as a text’ which is ‘open to interpretation leading to enhanced self-awareness’ (Graham, Walton, and Ward Citation2005, 21). Zoë Bennett and Christopher Rowland have the most extended engagement with the Bible and reflexivity to date, with the stated aim of ‘becoming more critically self-aware in our lives’ where ‘the Bible may assist us in that’ (Citation2016, 10; cf. Bennett Citation2013, 20). This is done through engagement with apocalyptic unmasking in the book of Revelation, eschatology in the letters of practical theologian Paul, and a number of other texts, particularly 1 Cor. 13.12, from which the book takes its title, In a Glass Darkly. The authors are very clear that the Bible does not function as an authority for them, but as a catalyst, albeit one that is ‘an indispensable tool in Christian critical imagination’ (Citation2016, 8, 161). These examples point to the variety of overlapping ways that Scripture speaks to our practices of reflexivity. It may be through exhortation, exemplar, symbol, metaphor, concept, character formation, implied epistemology or others that resist typologising. These ways work differently hermeneutically and so their normative function may also be construed differently, as the rest of this essay aims to demonstrate. As a broad starting point, I take normativity to include what ought to be, where that ‘ought’ comes from, and how that ‘ought’ is encountered. I recognise there are useful typologies of, and distinctions between, normativities in practical theology (e.g. Ideström and Kaufman Citation2018, 174–5; Watkins Citation2020, 48–9), but have avoided identifying with these specifics here. My priority rather is to show how the Bible might work normatively for reflexivity in the passages considered, and so have deliberately used normative verbs that are flexible enough for that task (e.g. challenge, enrich, fund, inform, invite, offer, shape, speak). I will engage in some ‘tell’ when being reflexive about the Bible and normativity later.

Clearly it is not possible to engage with all of Scripture on reflexivity in this essay. Of necessity, I need to be selective. What caught my attention and imagination in the DTh class were the mirrors and the conversations they provoked. The key image was ‘Hand with Reflecting Sphere’ (1935) by M. C. Escher (see ) and no doubt was picked up by Google because it featured on the front cover of an older work of sociology on reflexivity (Ashmore Citation1989). The image is a self-portrait having the alternate title ‘Self Portrait in Spherical Mirror’ and is taken from the original lithograph, hence it is a reverse image (and therefore shows Escher’s right hand) (Escher in Het Paleis, Citationnd). The choice of image itself was fairly random at the time, but it served my pedagogical purpose of looking back at oneself along with one’s context, and inviting reflection on the reflection from students. With the classroom and In a Glass Darkly in mind, then, engaging Scripture in this essay will mean looking into a selection of biblical mirrors. My question becomes ‘How might Scripture inform my understanding of mirrors, of knowing myself, and so perhaps reflexivity? And will I need to change that question after looking?’

Depending on translation, there are five or six references to mirrors in the canonical books of the Bible in noun or verbal form (Ex. 38.8; Job 37.18; Isa. 3.23; 1 Cor. 13.12; 2 Cor. 3.18; Jas 1.23). The Old Testament references are not germane to my reflexivity questions, so that leaves 1 Cor. 13.12, 2 Cor. 3.18 and Jas 1.23 for me to consider. This methodological approach has similarities to Stephen Barton’s study on the metaphor of face in Paul, where he considers both Pauline mirrors (Citation2015, 145f). Stephen Pattison also examines the two Corinthian mirrors in his book length work on Saving Face in a chapter entitled ‘Seeing the Face of God in the Bible’ (Citation2013: Ch 5, esp. p107f). I am extending this approach to include the Jamesian mirror, as well as the book of Ecclesiastes and a saying of Jesus in Lk. 11.33–36. These latter two Bible texts make no mention of mirrors, so some further rationale is needed. Apart from both being highly visual texts, the justification for including Eccl. and Lk. 11 or indeed any other non-explicit mirror text is that all of Scripture may be understood as a mirror; a point hinted at in 2 Cor. 3 and made plain in Jas 1, as will become apparent. On this basis I could engage with a very wide range of passages in Scripture in order to respond to my reflexivity questions, and this is rather the aspiration of the essay – that the Bible as a whole has the potential to enrich and challenge fundamental categories within practical theology such as reflexivity. Within this overarching aspiration and the mirror focus, my selection of these two additional texts has also been guided by wanting to include some different biblical genres and both testaments. Further text specific rationale for inclusion is given in the relevant sections below.

1 Corinthians 13.12

Starting with the explicit mirror texts, I begin with 1 Cor. 13:12, given its apparent fecundity for questions of reflexivity, and include the surrounding text below:Footnote5

8 Love never ends. But as for prophecies, they will come to an end; as for tongues, they will cease; as for knowledge, it will come to an end. 9 For we know only in part, and we prophesy only in part; 10 but when the complete comes, the partial will come to an end. 11 When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child; when I became an adult, I put an end to childish ways. 12 For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known. 13 And now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; and the greatest of these is love.

Drawing together these biblical usages, what is the sense of the mirror that riddles? It is not a comment upon the supposed poor quality of ancient mirrors, in that they may distort what is seen, but rather that what is seen is only an image, and so is indirect, incomplete and partial (as the parallel with vv9-10 would suggest) (Fitzmyer Citation2008, 499; Hollander Citation2010, 397; Witherington Citation1995, 271). While God is not named in the text, it is evident from the context and OT allusions that it is God who we will see face to face in the eschaton and thus who is reflected dimly in the mirror (contra Smith Citation2022). The ‘I’ / ‘we’ language also makes clear that this partial seeing and knowing of God is the condition of all Christians in the ‘now’, including Paul.

For my reflexivity questions, then, the first look into the mirror of 1 Cor. 13.12 does not offer a straightforward hermeneutical journey. It is not primarily for looking at myself but at God. It is a case of the Bible changing the focus of my (reflexivity) questions (Briggs Citation2015, 215). A closer second look suggests that 1 Cor. 13.12b may be significant, where knowing fully is linked to ‘even as I have been fully known’. The divine passive here underlines, as Fitzmyer argues, Paul’s view that ‘being known by God precedes all other knowledge’ (Citation2008, 500). The ‘I’ is the one who is known by God where ‘our knowledge of God will be a function of God’s knowledge of us’ (Spicq cited in Fitzmyer Citation2008, 500; cf. 1 Cor. 8.3, Gal. 4.9), where such knowledge is enabled by divine grace (Barton Citation2015, 147). This fits within the overall tenor of chapter 13, where over-realised ‘knowledge’ needs to cease as a Corinthian catchword; instead knowledge that is any knowledge at all is relational – an anticipation of seeing face to face – and characterised by agapē love. N. T. Wright goes so far as to describe Paul as offering an ‘epistemological revolution’, in contrast to the philosophies of his time, where ordinary human knowledge and wisdom is taken up into agape (Citation2013, 1355–6, 1361; cf. Barton Citation2015, 147; Bourdieu Citation1999, 614). Here we are nudging towards self-knowledge but not as originally expected.

2 Corinthians 3.18

Paul’s second use of mirror language in 2 Cor. 3.18 enables us to thicken this account further, given with preceding text (vv12-18) as follows:

12 Since, then, we have such a hope, we act with great boldness, 13 not like Moses, who put a veil over his face to keep the people of Israel from gazing at the end of the glory that was being set aside. 14 But their minds were hardened. Indeed, to this very day, when they hear the reading of the old covenant, that same veil is still there, since only in Christ is it set aside. 15 Indeed, to this very day whenever Moses is read, a veil lies over their minds; 16 but when one turns to the Lord, the veil is removed. 17 Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom. 18 And all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord, the Spirit.

Looking into the 2 Cor. 3.18 mirror, then, means to look at the face of Christ reflecting God’s glory, as is finally made explicit in 2 Cor. 4.6.Footnote6 In context, this face is revealed in the Scriptures by the Spirit. Looking at the face of Christ progressively transforms those that do so to ultimately bear his ‘image’. Here, Christ is both mirror and image. This transformation is by divine initiative (‘being transformed’), with the agency of the Spirit made very clear from its six mentions in chapter 3. This is also an internalised transformation, of the new covenant, written by the Spirit on the heart of those that gaze (v3; cf. Jer. 31.31–4; Rom. 12.2), in contrast to the ‘outer nature’ that is ‘wasting away’ (2 Cor. 4.16) (Barton Citation2015, 151–2; Keener Citation2005, 169).

In what ways, then, does 2 Cor. 3 thicken this account of mirrors for my reflexivity questions? There is less emphasis on the partiality of knowledge, but the mirror metaphor is still used to suggest indirect vision (Lambrecht Citation1983, 250). The two mirrors hold futurist and realised eschatologies (and epistemologies) in tension, or, alternatively, offer a ‘hermeneutics of clarity and obscurity’ (Mitchell Citation2010, 59). Collapsing this tension would indeed appear to be an attempt, in Dreyer’s words, to ‘objectify my subjectivity’ (Citation2016, 92). Knowledge is not explicitly in view in the second mirror until reading on to 2 Cor. 4.6 where the mirror shows ‘the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ’. This is underscored by divine Wisdom being understood at the time as a mirror perfectly reflecting God’s glory (Wis. 7.26) (Keener Citation2005, 170). Building on the relational nature of knowledge suggested by 1 Cor. 13, the mirror of 2 Cor. 3 pushes this further. Looking into the mirror transforms us because in turning to the Lord, I am now able to see (albeit as in a mirror) the face of Christ and the light and the knowledge and the glory that goes with that, which is not without effect. This is the light of new creation, as the Genesis allusion makes clear in 2 Cor. 4.6a (cf. 2 Cor. 5.17), which is transformative of all that we are, particularly knowledge of God and so of ourselves and of others. It is an epistemological recreation. David Ford spells out the ‘transformational grammar’ of this recreation as follows:

… the simplicity and complexity of facing: being faced by God, embodied in the face of Christ; turning to face Jesus Christ in faith; being members of a community of the face; seeing the face of God reflected in creation and especially in each human face, with all the faces in our heart related to the presence of the face of Christ … (Citation1999, 24–5)

We are not scientists, and human beings are not our subjects. We are theologians, and we enter into the lives and struggles of fellow human beings because we need to hold them before God and for God to hold them before us so that we can see them as they are, and allow them to help us to see ourselves anew for what we are (Citation2012, 106).

So the Spirit’s influence is necessary, not as a substitute for rationality in the presentation of the Gospel, but as a cure for moral vices which usually determine what kind of divine action human beings are willing to accept as plausible and persuasive. In Paul’s presentation the Spirit does not override human rationality, producing a belief in a truly irrational message. Rather that Spirit is involved here primarily in reorienting the moral life of those who are “chosen” (1:24), so that the message which would normally appear foolish can be seen and understood as wisdom (Citation2006, 34; cf. Wright Citation2013, 1362f).

James 1.23–24

Moving away from the Pauline corpus, the book of James provides our third mirror as follows (1.19–27):

19 You must understand this, my beloved: let everyone be quick to listen, slow to speak, slow to anger; 20 for your anger does not produce God’s righteousness. 21 Therefore rid yourselves of all sordidness and rank growth of wickedness, and welcome with meekness the implanted word that has the power to save your souls.

22 But be doers of the word, and not merely hearers who deceive themselves. 23 For if any are hearers of the word and not doers, they are like those who look at themselves in a mirror; 24 for they look at themselves and, on going away, immediately forget what they were like. 25 But those who look into the perfect law, the law of liberty, and persevere, being not hearers who forget but doers who act—they will be blessed in their doing.

26 If any think they are religious, and do not bridle their tongues but deceive their hearts, their religion is worthless. 27 Religion that is pure and undefiled before God, the Father, is this: to care for orphans and widows in their distress, and to keep oneself unstained by the world.

What then does the Jamesian mirror do for my understanding of reflexivity? The metaphor works differently to Paul’s; it is not about indirect knowledge of God and transformation is less explicitly in view; neither is the focus on the face of God (in Christ) in the mirror. Instead, the Jamesian mirror rather more indeterminately allows for a number of overlapping reflections; firstly of myself, secondly of the image of God inherent in me, and thirdly of Scripture, particularly Jesus’ teaching. Looking into the Jamesian mirror reveals who I am and my divine telos through the perfect law taught by Christ; it more straightforwardly conveys self-knowledge. For example, Søren Kierkegaard entitled his work that leads with an exposition of this very passage, For Self-Examination / Judge for Yourself! (Citation1990). Such self-knowledge, however, should be orientated to action – an insight close to the heart of practical theology.

Having said the metaphor works differently in James, it also ends up being similar to the Pauline mirrors via a different route. Once more, self-knowledge is about knowledge of oneself before God, and this is known and acted upon here according to both the written and incarnate Word (cf. Martin Citation1988, 55). Richard Bauckham captures this point in his reading of Kierkegaard’s reflections on Jas 1.22–27 as follows:

To know God is necessarily also to know oneself as an individual before God, as both loved and commanded by God, indebted and responsible to God. Thus to read Scripture as God’s word must mean to find oneself in it, given oneself and addressed by God (Citation1999, 3).

In rather greater contrast to Paul, the deception of sin is much more part of this mirror’s context (so 1.12–16, 22, 26). This deception is the disconnect between hearing and doing, between forgetting what has been seen and persevering (NRSV) or abiding by it (NASB). Remembering what is in the mirror in itself brings the freedom to act accordingly. James goes on to offer examples of forgetting and persevering respectively in vv26-27. Unlike the Corinthian mirrors, sin here is less about its epistemic impact but rather its impact on our practices (or lack thereof). Looking into this mirror will require vigilant self-examination of all that we do and do not do, including how we are reflexive.

Finally, Kierkegaard offers a valuable ‘in front of the text’ reading of the Jamesian mirror. What if I look only at the mirror and so forget to actually look into it? For Kierkegaard, in order to ‘look at oneself with true blessing in the mirror of the Word … The first requirement is that you must not look at the mirror, observe the mirror, but must see yourself in the mirror’ (Citation1990, 25). He goes on to make this a fairly polemical point about how a preoccupation with the whole apparatus of biblical studies (as understood then) can distract from actually being addressed by the Word. That is, ‘I very likely never come to see myself reflected’ (Citation1990, 26). I have been musing on whether the apparatus of reflexivity might pose the same danger analogously. Is it possible for the multiple frames of reflexivity to distract from looking into the mirror as well? Something like this is certainly recognised in the literature, for example, Daphne Patai characterises the proliferation of reflexivity talk as ‘too much time wading in the morass of our own positionings’ that undermines genuinely emancipatory research (cited in Pillow Citation2003, 175–6). Dreyer’s chapter from my DTh lesson warns of the seductive deception of reflexivity, when it claims to heal what cannot be healed by frames alone. How might this imagined Jamesian mirror catalyse our critique of reflexivity as currently practiced?

Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes is the first of two passages discussed in this essay that extends the mirror metaphor to Scripture as a whole, rather than to explicit textual instances. In addition to the reasons given earlier for selecting Ecclesiastes, it also appears to be the closest thing the Bible has to a fieldwork project, with the potential to goad our reflexive imaginations. While by no means a qualitative research companion, Ecclesiastes does spell out a form of participant-observer methodology (‘to seek and search out by wisdom’, v13a; also 1.17) and methods (‘I will make a test of pleasure’, 2.1–8; ‘weighing’, 12.9); lays out its rather extensive scope (‘all that is done under heaven’, 1.13a); is explicitly inductive and empirical; does not hide the contradictions and messiness of fieldwork; adopts a constructed persona in the text (so Qohelet / King over Israel, 1.12); and matters of reflexivity and epistemology are never far from the surface. Pick your biblical scholar on the last point; for example, Jennie Grillo notes the modern appearance of Ecclesiastes to contemporary readers because ‘it so persuasively conjures up a reflexive, self-conscious interiority’ (Citation2016, 2). Michael Fox argues that Ecclesiastes has an explicit epistemology, albeit ‘inchoate and unsystematic’, where the problem of epistemology is ‘one of the main concerns of [the] book’, if not indeed ‘the central one’ (Citation1999, 71).

Unlike the other biblical passages in this essay, the whole of Ecclesiastes is in view here. The very nature of the book – the reader’s rollercoaster ride from 1.1 to 12.14 – means it has to be taken as a whole. In a contradiction worthy of Ecclesiastes, however, I cannot include all the text of the book below. Instead, I have selected key passages from the (mostly) third person ‘frame narrator’ (1.1–11; 12.9–14) and the first person body of the book by ‘the Teacher’ or Qohelet (1.12–12:8):

The words of the Teacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.2 Vanity of vanities, says the Teacher, vanity of vanities! All is vanity. (Eccl. 1.1–2)

12 I, the Teacher, when king over Israel in Jerusalem, 13 applied my mind to seek and to search out by wisdom all that is done under heaven; it is an unhappy business that God has given to human beings to be busy with. 14 I saw all the deeds that are done under the sun; and see, all is vanity and a chasing after wind. (Eccl. 1.12–14)

9 Besides being wise, the Teacher also taught the people knowledge, weighing and studying and arranging many proverbs. 10 The Teacher sought to find pleasing words, and he wrote words of truth plainly.

11 The sayings of the wise are like goads, and like nails firmly fixed are the collected sayings that are given by one shepherd. 12 Of anything beyond these, my child, beware. Of making many books there is no end, and much study is a weariness of the flesh.

13 The end of the matter; all has been heard. Fear God, and keep his commandments; for that is the whole duty of everyone. 14 For God will bring every deed into judgment, including every secret thing, whether good or evil. (Eccl. 12.9–14)

Of course, intensity of the ‘I’ does not necessarily indicate a reflexive stance beyond that of a self-referential linguistic style. To make the reflexive case, some examples are needed – and there are plenty to choose from. Starting with 1.12, the first person voice adopts the made-up pseudonym ‘Qohelet’, variously rendered ‘the Teacher’ (NRSV, NIV) or ‘the Preacher’ (NASB). Qohelet then locates himself in the book as ‘king over Israel in Jerusalem’ (v12) who ‘acquired great wisdom, surpassing all who were over Jerusalem before me’ (v16; 2.9). With the majority of commentators, I take Qohelet to be a fictional Solomonic persona, adopted to serve the author’s theological purposes (Enns Citation2011, 17). Beyond location and persona, Qohelet time and time again shares his interior monologue with the reader. For example, in the NRSV, ‘I said’ is used ten times – ‘I said to myself’ four times (1.16, 2.1, 2.15a,b); ‘I said in my heart’ twice (3.17, 18); and he appears to be talking to himself in the remaining four instances as well. Other verbs such as ‘saw’ / ‘I have seen’, ‘found’, ‘consider(ed)’, ‘know’, and ‘thought’ also perform a similar confessional function (Crenshaw Citation1998, 205–6). Fox captures this reflexivity well:

Qohelet constantly interposes his consciousness between the reality observed and the reader. It seems important to him that the reader not only know what truth is, but also be aware that he, Qohelet, saw this, felt this, realized this. He is reflexively observing the psychological process of discovery as well as reporting the discoveries themselves (Citation1999, 79).

This is not the first apparent dead end in this essay. I want to step back from the more obvious reflexivity connections for a moment and start again somewhere else. I begin with hebel, variously translated as ‘vanity’ (NRSV), ‘meaningless’ (NIV), ‘absurd’ (Fox Citation1999) and ‘enigmatic’ (Bartholomew Citation2009). Literally ‘breath’ or ‘vapour’, it can be a chasing after the wind to grasp its shades of metaphorical meanings, as employed by Qohelet and the frame narrator. In my chase, I opt for ‘absurd’, following Fox, but recognise the similarity to the previous mirror of 1 Cor. 13 through Craig Bartholomew’s ‘enigmatic’. That hebel is critical to understanding Ecclesiastes is evident from its 38 occurrences and the inclusio it forms around most of the book in 1.2 and 12.8. ‘Utterly absurd’ in 1.2 is the frame narrator’s summary of Qohelet’s observations regarding the human condition (Enns Citation2011, 30–31). Not just meaningless, but a violation of meaning that speaks of life under the sun being twisted so to void it of significance (Fox Citation1989, 34, Citation1999, 49). Qohelet tells us of many things that are hebel including pleasure, toil, wisdom, justice, wealth and how death makes these things ultimately pointless. Permeating this hebel discourse, and of particular interest for reflexivity, are the twists and turns of Qohelet’s epistemological project. How does he know all is absurd? Not through the traditional sources of Israelite faith which are held at some distance in the book, but through a combination of observation, experience and reason mostly channelled for the reader via Qohelet’s ‘I’, with plenty of contradictions along the way. Indeed, the contradictions of life under the sun are the very substance of Qohelet’s absurd minority report by wisdom (Brueggemann Citation1997, 396). Knowledge is not immune from such contradictions. Qohelet realises the limitations of knowledge itself: it also is a chasing after the wind (1.17), uncertain (3.21, 6.12, 8.1), and even unattainable (7.24, 8.16–17, 11.5). There is a deep scepticism here of knowledge itself that ironically undermines his own claims to knowledge (Fox Citation1999, 85–6). All that is certain is that everything is absurd (Enns Citation2011, 119). Truly, it is the tragedy of the wise man par excellence who seeks wisdom but cannot find it.

Absurd may seem an apt description of seeking reflexive knowledge; of attempting to look back at myself like an epistemological game of Twister, not unlike Qohelet. It certainly captures something of the conundrum of reflexivity outlined by Dreyer earlier in the essay. There is more, however, that Ecclesiastes has to offer regarding (reflexive) knowledge, and this lies in the relationship between the frame narrator and the words of Qohelet. There are many interpretations of this relationship, but I will follow those who see the third person epilogue as intentionally of a piece with Qohelet, albeit with some friction between the two. The epilogist may even be the same author with their Qohelet mask removed.Footnote9 The epilogue is complimentary about Qohelet (v9-11), but at the same time offers an implied corrective to Qohelet’s conclusions (v12-14). The reader is invited to enter into Qohelet’s journey, but, as Enns argues, there is ‘something more’ to guide the reader from the broader faith tradition of Israel (Citation2011, 15–6). That is the same as it ever was, ‘Fear God, and keep his commandments’ (v13), wisdom and obedience, albeit expressed in the minimalist and distanced style of Ecclesiastes. It is given as a rule of faith for interpreting the book; in Fox’s language, it offers buffers and bounds for Qohelet’s wisdom (Citation1999, 95–6).

Some scholars see the frame and body of Ecclesiastes working even more closely together, with the frame confirming the deliberate ironic deconstruction of Qohelet’s assumed autonomous epistemology that leads only to hebel (e.g. Bartholomew Citation2009; Fisch Citation1988: Ch 9; O'Dowd Citation2007; Sharp Citation2008, 196–220).Footnote10 As mentioned previously, Qohelet’s ‘wisdom’ is largely derived from his ‘I’, with little place for wisdom that comes from the fear of the Lord (Bartholomew Citation2009, 87, 135). Two different wisdoms seem to be in view here. O’Dowd argues that Qohelet offers an ironic critique of this pseudo-wisdom through, for example, his rhetorical interactions with creation theology and interplay with Proverbs in particular (Citation2007, 80–83). On this reading, Ecclesiastes functions as a double-act rejection of such autonomy-derived wisdom showing this to be an epistemological dead-end that leads to the words of 7:23–24: ‘I said, “I will be wise,” but it was far from me. That which is, is far off, and deep, very deep; who can find it out?’ Ironic to the end, Qohelet without the mask mirrors the language of wider wisdom, where to fear God is the endpoint of wisdom and is indeed the whole duty of ‘man’. The proper study of mankind is therefore not man, ends the ironist (Fisch Citation1988, 175).

A Christian reading of Ecclesiastes will want to bring ‘something more’ to the something more of the epilogue (Enns Citation2011, 28–9). The person and work of Christ is the hermeneutical prism for Christian understanding of the Scriptures. For Ecclesiastes, where death is such a dominant theme, resurrection casts a new light on all that is hebel. At the same time, I am convinced that a Christian theology of Scripture requires me to respect the carpe diem peaks and many hebel valleys of the Ecclesiastes landscape. On a buffers-and-bounds type reading, Ecclesiastes disrupts and affirms the three New Testament mirrors already considered. Resurrection relativises absurdity, but absurdity is still evident in all aspects of Christian experience, including my knowing. Ecclesiastes takes the partiality of knowledge to new places, stretching epistemological tension nearly to breaking point. He/they make space for epistemological despair that is not the final word in Christian wisdom, but there are also hints of virtues such as humility (regarding our knowledge of life under the sun) and confidence (gained from the fear of God) that have an ongoing trajectory in the narrative of Scripture (Bartholomew Citation2009, 277; Rogers Citation2016, 189–192). On an ironic reading, Qohelet and his frame accomplice work to bring the reader to despair of epistemological autonomy, pushing them instead to find genuine wisdom within the fear of God and obedience to him. Such an emphasis may match the other mirrors more closely, yet requires the reader to undertake a more goading journey, as well as raising questions about respect for Qohelet’s ironic landscape, comprised as it is of ‘deceitful hues and unstable, shifting contours’ (Sharp Citation2008, 219). Anthony Thiselton writes of Job and Ecclesiastes that their primary function is not as ‘raw-material for Christian doctrine’. Rather, it is ‘to invite or provoke the reader to wrestle actively with the issues, in ways that may involve adopting a series of comparative angles of vision’ (Citation1992, 65–66). Ecclesiastes offers rich resources for the practical theologian to wrestle with reflexivity, so complexifying their understanding and practice.

Luke 11.33-36

My final text, like Ecclesiastes, is also a non-explicit or implied mirror. It is a saying of Jesus:

33 “No one after lighting a lamp puts it in a cellar, but on the lampstand so that those who enter may see the light. 34 Your eye is the lamp of your body. If your eye is healthy, your whole body is full of light; but if it is not healthy, your body is full of darkness. 35 Therefore consider whether the light in you is not darkness. 36 If then your whole body is full of light, with no part of it in darkness, it will be as full of light as when a lamp gives you light with its rays.”

The text does seem to suggest a form of reflexive practice, particularly v35 which presents ‘an existential challenge to self-evaluation’ (Green Citation1997, 466; cf. Allison Citation1987, 78). The parallel passage in Mt. 6.22–23 omits the directive force of this Lukan verse, variously translated ‘consider’ (NRSV), ‘see to it then’ (NIV), or even ‘watch out’ (NASB). What is the substance of this apparent reflexive challenge in context? There is some controversy over what the lamp is in v33 (e.g. Garrett Citation1991, 95), but I take it to mean Jesus and the light of his ministry (Nolland Citation1993, 656). This is strongly indicated by the encounters preceding this passage, particularly immediately beforehand with Jesus announcing ‘something greater’ than the wisdom of Solomon and the proclamation of Jonah ‘is here!’ (11.31–32; see also 1.78–79; 2.32). The second lamp is the eye (v34), expressed in what was probably a proverbial saying at the time (Allison Citation1987, 62). The oddity of the eye being a lamp is explained by a premodern physiology that understood light to emanate from inside the body and shine out through the eye (‘extramission’), so the eye in that sense is a source of light like a lamp (Allison Citation1987; Green Citation1997, 465–466). How the two lamps relate to each other, however, is less clear. In agreement with Susan Garrett, I see the passage as operating with a metaphorical logic of lamps, eyes, light and darkness that is ‘primarily evocative than precisely referential’ (Citation1991, 95–6).Footnote11

At the heart of the passage is the healthy (haplous) or not healthy (ponēros) eye. The word used for ‘healthy’ literally means ‘single’, rather than double or triple, and while not normally used as a medical term, the parable genre and context indicate both a medical and ethical sense is intended (Garrett Citation1991, 99–100; Green Citation1997, 465; Nolland Citation1993, 657). The term ‘not healthy’ usually means ‘evil’, and here works in the same dual sense as ‘healthy’. ‘Evil’ also provides a linguistic link to the preceding ‘sign of Jonah’ discourse, where sign-seeking is the unhealthy eye behaviour of this ‘evil generation’ (11.29) (Green Citation1997, 462). The ethical sense of ‘healthy’ is attested to be in the overlapping virtue-like domains of sincerity, generosity, integrity, wholeheartedness, and singlemindedness; in Garrett’s terms, the healthy or ‘single eye’ belongs to the person who ‘focuses his or her eye on God alone’ (Allison Citation1987, 77; Garrett Citation1991, 94, 99; Green Citation1997, 466; Nolland Citation1993, 657).

With these points in mind, the two parables here overlap to speak of the eye that receives the light of Jesus’ ministry; of the light (or darkness) that flows out from the eye that reveals who a person is; of the need for a healthy eye that is single in being so focussed on Jesus that the disciple is ‘full of light’. The relationship between the two lamps might be explained by a two way intermingling of lights, although one needs to take care not to press the passage too hard. The difficult to interpret Lukan v36 appears to combine the two lamp sayings as summary and/or eschatological promise (‘will be’) and/or emphasising the salvific action of the light.Footnote12 The call for self-examination in v35 challenges would-be followers of Jesus to see if they are deceived about receiving his light – by themselves, others or Satan (Fowl Citation1998, 76–77); the latter particularly in the context of this passage (e.g. 11.14–26). Such deception is caused by taking one’s eye off the light of Christ, and is evidenced by the darkness within that the unhealthy eye reveals through certain behaviours. This state of deception is the opposite of the integrity that Jesus frequently calls for in the synoptics contrasting outward acts and inner states, such as good trees not bearing bad fruit (so Lk. 6.43–4; see also e.g. Lk. 11.44; Mt. 12.34; Mk. 7.15–23) (Allison Citation1987, 78). The passages immediately following regarding Jesus’ interactions with the Pharisees similarly emphasise the need to be clean both within and without (11.37–44), and the attendant dangers of hypocrisy also expressed in terms of dark and light (12.1–3).

Of the five mirrors considered, this saying of Jesus offers the most direct reflexive imperative. It is indicative of the many calls in Scripture to examine ourselves in relation to God (e.g. Lam. 3.40; 1 Cor. 11.28; 2 Cor. 13.5). Lk. 11.35 in particular is a reflexive challenge to disciples of Jesus not to confuse light and darkness, or to even consider masquerading darkness as light. But how does this relate to reflexive practice in qualitative research? New doctoral researchers in practical theology may feel talk of light, darkness and the deception of Satan is rather removed from the everyday experience of fieldwork. It is true that Luke 11:33–36 and contemporary theological fieldwork are distant in time and space; nevertheless, I suggest it is also true that they do speak to each other. My initial response, to which I will return later, is to say that reflexivity appears to have its own form as a Christian practice, and so this will carry over into all areas of the disciples’ life today, including fieldwork in theology where a healthy eye is much needed. In addition, I believe that a virtue account of reflexivity also offers a hermeneutical vehicle here.

A virtue account asks who is looking into the mirror (of Scripture). That is, what sort of person are they? A vigilant one, is Fowl’s answer to this question, based on his reading of the single eye where he develops its virtuous significance. I will follow his argument briefly here (Citation1998: Ch 3). Jesus’ imperative to consider the state of one’s eye requires ongoing vigilant attention, as the eschatological hint in v36 suggests (p77), particularly when considered with the other self-examination passages in the Bible. This vigilance about how believers read Scripture (in Fowl’s case) or how practical theologians read fieldwork settings (in my case) requires truthful, critical self-reflection both for oneself and one’s community. Such vigilance, like all genuine Christian virtues, is not an end in itself, but is to enable believers to better attend to God (p79). Fowl gives examples from Luke of characters who do or do not demonstrate the sort of singular vigilance called for, such as Zacchaeus (19:1–10), Simon the Pharisee and the woman ‘who was a sinner’ (7:36–50), and perhaps most explicitly the Pharisee and tax collector (18:9–14) (p79–80). He concludes, convincingly in my view, that all of the characters wish to see Jesus, but not all are appropriately attentive to him and do not display the self-knowledge of those who can ‘identify themselves as sinners’ (p81). For Fowl, this is the core content of vigilance, if it includes forming others to identify in this way; if this identity ‘injects a crucial element of provisionality into one’s interpretative practices’; if this identification is accompanied by ‘practices of forgiveness, repentance, and reconciliation’ (p81–83, 96).

My argument at the beginning of this section was that there is substantial overlap between vigilance for reading Scripture and vigilance for reading ourselves. That is, hermeneutical and reflexive vigilance have a lot in common. The vigilance characterised here by Fowl mingles with insights gained from this and previous mirrors considered regarding provisionality, sin and deception. Virtue, however, enables a different hermeneutical vehicle, where the particular character of Lukan vigilance, headlined in 11.35, can be taken forward in virtue form for contemporary improvisation of reflexive practice today.

Vigilance, of course, is not the only virtue emerging from Scripture that may aid reflexivity. Virtues have been named in the previous passages, such as love in 1 Cor. 13, a related form of vigilance in James 1, and humility and confidence in Ecclesiastes. That it is legitimate to speak of virtue in these biblical books has been argued by many scholars.Footnote13 Given the recognition of this substantial biblical virtue tradition, I think it highly likely that there is scope for further development of reflexive virtue. This is confirmed by the values and virtue language used in a number practical theology publications that may have a bearing on reflexivity (e.g. Bennett et al. Citation2018: esp. Ch 7; Paterson and Kelly Citation2013). My purpose here is not to flesh out a full-blown biblical virtue account of reflexivity, but rather to argue that it is legitimate and worthy of further development as it offers a valuable biblical and theological vehicle for the practice of reflexivity today.

Being normative about reflexivity (and vice versa)

Looking into these mirrors has been offered as a case study of the Bible’s normativity for practical theology, to see how the Bible might fund our thinking and practice of reflexivity. How these mirrors work together can be expressed in different (mixed metaphor) ways. Aural/oral metaphors speak of a multi-voiced account of reflexivity with both resonance and dissonance. Ethnographers, particularly of the theological kind, seek thicker descriptions, although more than description is in view here. Given the highly visual nature of the five passages, the clarity or otherwise of the mirrors may well be more apt language. My contention is that while each of the five passages inform reflexivity in their own particular way, there are resonant/thicker/higher resolution insights that can be identified, as the preceding section has hopefully demonstrated.

For me, the key insights are both epistemological and ontological. Our self-knowledge is a function of divine knowledge – of epistemic grace rather than works. This self-knowledge flows out of relationship with God faced in Christ through the Spirit, and it is a knowledge of self in relation to God and others. Looking into the mirrors reveals our epistemic condition. Our knowledge of ourselves-in-relation, like our knowledge of God, is partial because it is eschatological; is gained communally; and has a spiritual dimension and so is affected by sin. Ecclesiastes provides a ring in which to wrestle with this sometimes absurd partiality and/or warns us of the danger of knowledge apart from God. Looking into the mirrors to know God (through Scripture), and so know ourselves, also is transformative of who we are and so what we do. Its effect is to make us more like Christ, where this ontological change in itself will further illuminate our self-knowledge. The mirrors also show the need for developing reflexive virtue, including vigilance about our practices, and how (theoretical) frames might distract us from genuinely transformative self-knowledge. These insights then reframe the characteristics and conundrum of reflexivity represented (slightly unreliably) at the beginning of this essay, challenging some of the received wisdom on reflexivity in practical theology.

I do not see these mirrors as the last word in theological wisdom regarding reflexivity. There are many more riches to unearth in Scripture on this theme, as well as within the broader Christian tradition. But I think they do offer a pertinent word for current discourse around reflexivity in practical theology. Firstly, the Bible needs to better inform our reflexivity curriculum. As previously mentioned, there are examples of this in the literature, but currently they are few and far between. From these reflections on Scripture, I would argue that reflexivity has its own theological integrity; it is not just a loan practice from other disciplines. A number of theologians have spoken of ‘theological reflexivity’ (or similar), with a range of meanings. The most common of these centres on acknowledging and possibly critically operating according to one’s theological commitments in the conduct of theological research or pastoral care (e.g. Bunton Citation2019, 83). Others, such as Daniel Pilario, have laid out the implications of bringing ‘reflexivity discourse in the social sciences and philosophy into theology’ (Citation2018, 115). Wigg-Stevenson has drawn out the highly distinctive nature of reflexivity for fieldwork in theology, since ‘the academic fields of theology and anthropology/sociology are, respectively, disciplines that do and do not arise organically from the social practices they study’ (Citation2013, 3). The reflexive theologian is indeed often highly entangled in the practices of their fieldwork sites (Ideström Citation2018). Wigg-Stevenson has also explored theological epistemology in reflexive terms, asking ‘how is theology produced’ and ‘how ought it be produced’ (Citation2014, 168, cf. 115). All of these are valuable and important developments for theological reflexivity. But in this essay I want to push theological reflexivity a little further. It ought to include seeing how the Bible and our theological convictions shape our understanding and practice of what reflexivity should be. To be clear, this means being more explicit about how we norm our reflexivity. It is surprising that practical theologians, with a few exceptions, have not taken theological reflexivity this far. Examples of calls to do this come from Peter Bunton (Citation2019, 93) and more generally from John Swinton (Citation2012, 90) and Pete Ward (Citation2018, 165f). I am not going all Milbankian here; rather my argument in this essay is part of what I see as the theological ethnographic project to do fieldwork as a theologian (Scharen Citation2005, 141); to be more theological about practical theology (Ward Citation2017, 6). I do think that social science accounts of reflexivity, such as Bourdieu’s, are valuable and insightful, enriching my interpretations of the reality I am researching, its ideological distortions and the dynamics of knowledge production. Nevertheless, I am questioning how much of a genuine conversation practical theology is having with social science on reflexivity – it still seems rather one-sided at present.

Secondly, and unsurprisingly, what about the mirror metaphors? I begin with the three explicit mirrors. I find myself corrected pedagogically by engaging with Scripture on this matter. If I prioritise the historical and literary contexts of these biblical metaphors, then my use of mirrors for teaching reflexivity needs complexifying. Escher’s work may serve better as comparison than exemplar. Fairground allusions need challenging as well; the three explicit mirrors do not distort, nor present illusions or delusions, but they variously are partial in what they reveal and do transform the one looking. The two remaining mirrors of Ecclesiastes and Luke 11 are implied, in the sense that all of Scripture may be understood as a mirror, as argued previously. What does it mean for these implied mirrors or indeed any Bible passage to function as a mirror for the reader? The three explicit mirrors offer a strong clue. With varying emphases, they show God (in Christ) in relation to who we are, who we ought to be, and who we will be. Ecclesiastes and Luke 11 have demonstrated aspects of these mirror characteristics without actual mirrors, while I also see that these and other implied mirror passages may broaden what it means to look into the mirror. A number of scholars, however, have commented upon the inadequacy of mirror metaphors for reflexivity; that they are too simple or static or dualistic or narcissistic.Footnote14 They would have a point. But these biblical metaphors (or texts) are no ordinary mirrors, whether explicit or implied, as I have attempted to show, surpassing even the fairground. With their different nuances, these mirrors break down such objections, through the relational, self-involving and so kenotic act of looking.

Thirdly, I need to be reflexive about my normativity (cf. Ideström and Kaufman Citation2018, 180). I do not see the Bible as one theological resource amongst many within the Christian tradition, but as exercising authority for Christian theology in practice. How this authority and so normativity is construed, however, is according to the texts engaged, the contexts examined, and the hermeneutics employed. For reflexivity, such normativity has worked differently when, for example, looking at Qohelet’s goad to our reflexive imagination; or Paul’s transformative glory gazing; or Jesus’ imperative to self-examination. I recognise that all interpretations have degrees of provisionality. For the mirrors, I also recognise that metaphors in particular have some indeterminacy in their meaning and that more intentionally in-front-of-the-text readings may move beyond their historical meanings. The mirrors may indeed catalyse other metaphors and images to inform our reflexivity curriculum. For me, a critical pluralism of hermeneutical approaches means a ‘faithful improvisation’ of the texts is needed.Footnote15 This raises the question of what the canon of metaphors for reflexivity might be – are there any boundaries for the interpretative imagination? (e.g. is Kierkegaard’s reading legitimate?) Such questions range beyond the scope of this essay, but I do see the biblical mirrors as a normative source for theological reflection upon reflexivity, albeit only offering partial contours for reflexive practice that may be taken up in a variety of different ways, given the hermeneutical provisos identified.

This essay has been a venture as a practical theologian engaging Scripture; it is a biblical and theological reflection upon pedagogical practice, as well as a meta-reflection on the field of practical theology and its practice regarding normativity and reflexivity. Meta-reflections are not the everyday activity of practical theology, but they serve a purpose to clarify or complexify why we are doing what we are doing, how we are doing it and even if we should be doing it. This venture has some overlap with theological interpretation of Scripture, which is about the capacity of Scripture ‘to speak in the present tense across time and space’ with a focus on ‘interpretation oriented to the knowledge of God’ (Green Citation2011, 3–5; Vanhoozer Citation2005, 24). Mark Cartledge, however, argues for a distinctly practical theological reading of Scripture, comprising at least five dimensions which are similar to the approach I have taken in this essay. Two in particular stand out: being hermeneutically reflexive and intentionally bringing contemporary questions to the text (Citation2015, 45–46). This essay is part of an ongoing conversation within contemporary practical theology regarding the practice (and characterisation) of practical theological interpretation of the Bible; I look forward to seeing how the conversation develops further. Now, however, it is time to turn to action.

Reflexivity in action

So what difference does this make? To borrow from Brueggemann’s typology of the Psalms (Citation1995, 9f), I find that I have experienced disorientation and reorientation in these reflections on reflexivity. As narrated, this has arisen from noting the near absence of the Bible in the reflexivity literature, the challenges of social science accounts, and engaging with the Scriptures for myself and with doctoral students. How might I and possibly others reorientate their practice and teaching of reflexivity? The key reorientation for me is that of my self-knowledge being derivative of my knowledge of God, and its eschatological orientation. Such knowledge is rooted in the everyday life of faith, through confession, repentance, prayer, worship, Bible reading, communion and many other spiritual practices (cf. Rae Citation2007, 163). Reflexivity is not as new to the Christian tradition as it may at first appear; Paris, Jerusalem and Corinth are on talking terms.

Four particular actions for the classroom (where this all started) and beyond have emerged from these reflections for me, and my hope is that readers may find others as well. Firstly, I have needed to discover the no-ordinary-mirrors of Scripture in order to complexify my teaching of reflexivity. I have now placed Escher alongside the peculiar mirrors of Scripture in the classroom, allowing for a critical interaction between the two. I have sometimes also encouraged students to identify their own reflexivity metaphors and images, leading to discussions of the normative power they exert.

Secondly, looking into the mirrors has drawn out a number of spiritual practices for theological reflexivity. Other theologians have also noted how certain spiritual practices are also reflexive practices (e.g. Bennett and Rowland Citation2016, 155f; Campbell-Reid Citation2018, 98; Pilario Citation2018, 120). This points to the wider spiritual turn for qualitative research in theology, which calls for a ‘reimagining [of] the theological character of qualitative research practice’ (Campbell-Reed and Scharen Citation2013, 234; cf. Watkins Citation2022). Looking into the mirrors offers a biblical theological rationale for reflexive spiritual practices within the growing number of reimagined research methods.

I am working through how these spiritual practices will take shape in my research and pedagogical practice. I would not be the first to encourage students to pray within and over their research, although this does not sit easily with the norms of the (post)modern academy. Exposure to examples of reimagined methods in the classroom will be important; on prayer, this might include the practice of prayer within theological action research (Butler Citation2020) or waiting upon the leading of the Holy Spirit in focus groups (Arthur Citation2022). Confession, repentance and the language of sin also has its place in the reflexivity curriculum, given the impacts of sin revealed in the mirrors, both individually but also in terms of sinful structures. There is a need to move beyond the ‘empty confessions’ that I modelled earlier in this essay,Footnote16 towards inculcating more genuine and integrated forms of theologically reflexive confession. There are no short cuts here, but I suggest it will include learning when and how to speak as ‘I’, guided by reflexive virtues such as love, humility and confidence. There is something also to learn from the genre of Christian confession, which Todd Whitmore identifies as writing ‘that uses the self to testify to God and the world God has made’ (Citation2021, 76). Christopher Brittain draws on Augustine’s Confessions to argue that ethnography ‘contributes to the presentation before God of the church’s present reality’ (Citation2012, 132). This notion of confession writing appears to have much in common with the ‘community of the face’ discussed in 2 Cor. 3; in addition, Qohelet’s project ‘to seek and to search out by wisdom all that is done under heaven’ (Eccl. 1.13) can be read as a form of vicarious confession in this sense.

Thirdly, asking the right questions of ourselves is critical for reflexive practice, particularly given the emphasis on self-examination in the biblical mirrors. I have used the helpful set of starter questions in Invitation to Research in Practical Theology as a class activity to guide and enrich students’ reflexive practice (Bennett et al. Citation2018, 42). Although I appreciate that questions do not necessarily need to use theological terms to be theological, I have added more theologically explicit questions around how our knowledge of God (and so ourselves-in-relation) might aid reflexive practice. Such questions enable self-examination of student horizons, and, undertaken as a group activity, approximate the communal dimension of theological reflexivity. I have argued that reflexive virtues are vehicles for the mirror theologies discussed, so key questions include ‘What do reflexive virtues (e.g. vigilance, humility) look like in the context of your project?’

Fourthly, I have argued that in order to know oneself truly, one must look into the mirror of the Word. This includes practical theologians. BIAPT Bible and practical theology group meetings have been doing this for many years; i.e. reading the Bible together with minimal agenda to illuminate issues within practical theology. Inspired by this example, I have been setting aside time for students to do this in class as well. Retrospectively, I realise this practice is also recommended by the mirrors. While costly in time, such Bible reading creates space for thinking theologically about practical theology, including reflexivity, via a spiritual practice familiar to most students. This classroom exercise also allows for internalising the word in practical theology formation (a prominent theme for two of the mirrors); has the benefit of being communal; and also lends itself to generating further images and metaphors which include other senses. One of the passages now included in this exercise is Ecclesiastes, which also is likely to have been intended for pedagogical use originally (e.g. Eccl. 12.12). This book can provoke reflection on epistemological assumptions and limits, as well as questions of representation in terms of how ‘I’ is located and written. Taken alongside insights from the other mirrors, it raises questions as to what genre of representation is appropriate for fieldwork in theology. The anthropologist, James Bielo, argues that theologians may need to develop their own genres of ethnographic writing, calibrating their authorial imagination to the telos of their work. He challenges theological ethnographers to consider ‘witnessing, rebuke, confession, prophecy, prayer’ as more suitable genres (Citation2018, 154–155). If so, the Bible will prove invaluable for this task.

That is enough words. The last word, then, is for the title to become a question. How will practical theologians look into the biblical mirror(s) and what difference will it make to our reflexive practices?

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my DTh Practical Theology classes at the University of Roehampton for drawing out the issues that this essay addresses. Thanks also to numerous colleagues who offered comments on papers and drafts of this essay. I am also grateful to the anonymous peer reviewers whose insightful comments sharpened the final version of the essay.

M. C. Escher’s “Hand with Reflecting Sphere” and “Drawing Hands” © 2023 The M. C. Escher Company – The Netherlands. All rights reserved. www.mcescher.com.

The Scripture quotations contained herein are from The New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Anglicized Edition, copyright © 1989, 1995 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. All rights reserved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrew P. Rogers

Andrew Rogers is Associate Professor of Practical Theology at the University of Roehampton. He co-convenes an ecumenical open access degree programme in Theology, Mission and Practice, and also teaches on the DTh in Practical Theology. Andrew also co-convenes the BIAPT Bible and practical theology special interest group. His research interests include Bible and practical theology; faith, place and planning; and diaspora church demographics and ecclesiology. He is the author of Congregational Hermeneutics: How Do We Read? (Routledge, 2016) and has contributed a chapter on biblical studies to the Wiley Blackwell Companion to Theology and Qualitative Research (2022).

Notes

1 This essay has been developed from papers presented at the BIAPT 2019 annual conference and the 2021 Scandinavian-British Research Colloquium.

3 From the unpublished symposium report.

4 This will be an underestimate, as some relevant articles are missed by these criteria, and Contact does not appear to use keywords. I have not included articles / book reviews from JATE (previously BJTE) prior to 2018.

5 All Bible quotations are taken from the NRSV (Anglicised), unless indicated otherwise.

6 ‘seeing’ is preferable to the alternative translation of ‘reflecting’ the glory of the Lord, as it makes more sense of the contrast in the passage (Martin Citation2014, 215; Lambrecht Citation1983, 246f).

7 There is not space to look at the debates here, but see Allison who argues against this view (Citation2013, 335f), contra to the arguments of Davids (Citation1982), Martin (Citation1988) and Moo (Citation2015).

8 For example, respectively, Kolia (Citation2020, 34); Rudman (Citation2001); O'Dowd (Citation2007, 83); Sheriffs (Citation1996, 179f); Sharp (Citation2008, 212); O'Dowd (Citation2007, 83, Citation2013, 197, 208); Brueggemann (Citation1997, 393, 398); and Fisch (Citation1988, 158).

9 Some, like Fox, posit an epilogue (v9–12) and a separate postscript (v13–14) added later (Citation1999, 363).

10 ‘Ironic deconstruction’ is given as one type of reflexivity in Finlay’s social science textbook (Citation2003, 14f).

11 Similar use of imagery can be found in 2 Cor 4.4, one of the earlier mirrors considered (Garrett Citation1991, 96).

12 E.g. respectively Nolland (Citation1993, 658); Garrett (Citation1991, 103) and Schweizer (Citation1984, 196), contra Nolland (Citation1993, 658); Garrett (Citation1991, 95, 103) also Nolland (Citation1993, 658).

13 For example, of Ecclesiastes, see Brown (Citation2021, 63) and Christianson (Citation2002); of Pauline writing, see Wright (Citation2013, 1374); of James, see Perkins (Citation1995, 105–7, 122) and Davids (Citation1982, 54).

14 So Bennett and Rowland (Citation2016, 152), Bolton with Delderfield (Citation2018, 21, 133, 136), Bennett et al. (Citation2018, 37–38).

15 This phrase has become widespread in recent years, but my main engagement has been with N. T. Wright’s use (Citation1992, 139f).

16 Pilario’s term (Citation2018, 116), drawing on Bourdieu and Wacquant (Citation1992, 194).

References

- Allison, Dale C. Jr. 1987. “The Eye is the Lamp of the Body (Matthew 6.22–23=Luke 11.34–36).” New Testament Studies 33 (1): 61–83. doi:10.1017/S0028688500016052.

- Allison, Dale C. Jr. 2013. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on The Epistle of James. London: T&T Clark.

- Arthur, Sheryl. 2022. “An Elim Community Pneumatologically Engaged in Corporate Theological Reflection.” In Evangelicals Engaging in Practical Theology: Theology that Impacts Church and World, edited by Helen Morris, and Helen Cameron, 192–200. London: Routledge.

- Ashmore, Malcolm. 1989. The Reflexive Thesis: Wrighting Sociology of Scientific Knowledge. London: University of Chicago Press.

- Ballard, Paul H. 2006. “The Bible as Pastor (Special Issue).” Contact: Practical Theology and Pastoral Care 150 (1): 1–54. doi:10.1080/13520806.2006.11759042.

- Ballard, Paul. 2011. “The Use of Scripture.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Practical Theology, edited by Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore, 163–172. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ballard, Paul H., and Stephen R. Holmes, eds. 2005. The Bible in Pastoral Practice: Readings in the Place and Function of Scripture in the Church. London: Darton, Longman and Todd.

- Bartholomew, Craig G. 2009. Ecclesiastes. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

- Barton, Stephen C. 2015. “The Metaphor of Face in Paul.” In Conception, Reception and the Spirit: Essays in Honour of Andrew T. Lincoln, edited by J. Gordon Mcconville, and Lloyd K. Pietersen, 136–153. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books.

- Bauckham, Richard. 1999. James: Wisdom of James, Disciple of Jesus the Sage. London: Routledge.

- Bennett, Zoë. 2013. Using the Bible in Practical Theology: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Bennett, Zoë, Elaine Graham, Stephen Pattison, and Heather Walton. 2018. Invitation to Research in Practical Theology. London: Routledge.

- Bennett, Zoë, and Christopher Rowland. 2016. In a Glass Darkly: The Bible, Reflection and Everyday Life. London: SCM.

- Bielo, James S. 2018. “An Anthropologist is Listening: A Reply to Ethnographic Theology.” In Theologically Engaged Anthropology, edited by J. Derrick Lemons, 140–155. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bolton, Gillie, and Russell Delderfield. 2018. Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development. London: SAGE.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1999. “Understanding.” In The Weight of the World: Social Suffering in Contemporary Society, edited by Pierre Bourdieu. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loïc J. D. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Oxford: Polity Press.

- Briggs, Richard. 2015. “Biblical Hermeneutics and Practical Theology: Method and Truth in Context.” Anglican Theological Review 97 (2): 201–217. doi:10.1177/00033286150970020.

- Briggs, Richard, and Zoë Bennett. 2014. “Review Article – Using the Bible in Practical Theology: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives.” Theology and Ministry 3. Accessed March 19, 2023. https://theologyandministry.webspace.durham.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/303/2022/09/TheologyandMinistry3_7.pdf.

- Brittain, Christopher C. 2012. “Ethnography as Ecclesial Attentiveness and Critical Reflexivity: Fieldwork and the Dispute Over Homosexuality in the Episcopal Church.” In Explorations in Ecclesiology and Ethnography, edited by Christian Scharen, 114–137. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Brown, William P. 2021. “Virtue and its Limits in the Wisdom Corpus: Character Formation, Disruption, and Transformation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Wisdom and the Bible, edited by Will Kynes, 45–64. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brueggemann, Walter. 1995. The Psalms and the Life of Faith. Minneapolis, MN: Fortess Press.

- Brueggemann, Walter. 1997. Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress.

- Bunton, Peter. 2019. “Reflexivity in Practical Theology: Reflections from Studies of Founders’ Succession in Christian Organisations.” Practical Theology 12 (1): 81–96. doi:10.1080/1756073X.2019.1575039.

- Butler, James. 2020. “Prayer as a Research Practice?: What Corporate Practices of Prayer Disclose About Theological Action Research.” Ecclesial Practices 7 (2): 241–257. doi:10.1163/22144471-BJA10021.

- Campbell-Reed, Eileen R., and Christian Scharen. 2013. “Ethnography on Holy Ground: How Qualitative Interviewing is Practical Theological Work.” International Journal of Practical Theology 17 (2): 232–259. doi:10.1515/ijpt-2013-0015.

- Campbell-Reid, Eileen R. 2018. “Reflexivity – A Relational and Prophetic Practice.” In What Really Matters: Scandinavian Perspectives on Ecclesiology and Ethnography, edited by Jonas Ideström, and Tone Stangeland Kaufman, 77–98. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

- Cartledge, Mark J. 2013. “The Use of Scripture in Practical Theology: A Study of Academic Practice.” Practical Theology 6 (3): 271–283. doi:10.1179/1756073X13Z.00000000017.

- Cartledge, Mark J. 2015. The Mediation of the Spirit: Interventions in Practical Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Christianson, Eric S. 1998. A Time to Tell: Narrative Strategies in Ecclesiastes. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Christianson, Eric S. 2002. “The Ethics of Narrative Wisdom: Qoheleth as a Test Case.” In Character and Scripture: Moral Formation, Community and Biblical Interpretation, edited by William P. Brown, 202–210. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Crenshaw, J. L. 1998. “Qoheleth's Understanding of Intellectual Inquiry.” In Qohelet in the Context of Wisdom, edited by A. Schoors, 205–224. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Davids, Peter. 1982. Commentary on James. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Dickson, Ian. 2007. “The Bible in Pastoral Ministry: The Quest for Best Practice.” The Journal of Adult Theological Education 4 (1): 103–121. doi:10.1558/jate.v4i1.103.

- Dreyer, Jaco S. 2016. “Knowledge, Subjectivity, (De)Coloniality, and the Conundrum of Reflexivity.” In Conundrums in Practical Theology, edited by Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore and Joyce Ann Mercer, 90–109. Leiden: Brill.

- Dunn, James D. G. 1997. Jesus and the Spirit: A Study of the Religious and Charismatic Experience of Jesus and the First Christians as Reflected in the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Enns, Peter. 2011. Ecclesiastes. Grand Rapid, MI: Eerdmans.

- Escher In Het Paleis. nd. “Hand with Reflecting Sphere.” Accessed May 9, 2022. https://www.escherinhetpaleis.nl/showpiece/hand-with-reflecting-sphere/?lang=en.

- Finlay, Linda. 2003. Reflexivity: A Practical Guide for Researchers in Health and Social Sciences. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Fisch, Harold. 1988. Poetry with a Purpose: Biblical Poetics and Interpretation. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.