Abstract

This essay investigates four exhibitions linked to Pop art that took place in former Yugoslavia in the 1960s: Olja Ivanjicki’s Pop Art (1964, Belgrade), New Figuration of the Belgrade Circle (Belgrade, 1966), and the two US-sponsored Pop Art (1966, Zagreb, Belgrade) and The New Vein: The Figure (Belgrade, 1969). The discussion explores the reception of Pop art in socialist Yugoslavia and the ways in which Yugoslav artists deployed the style as a vehicle to address political events, histories, and new phenomena, such as Yugoslavia’s orientation towards a market economy and the development of consumerism as a result of the country’s opening to the West. The essay reveals how the Yugoslav reception of Pop art was bound up with issues of national and political identities, aesthetics, and gender.

“Pop Art: Art or Scam?” This provocative headline in a 1964 Serbian weekly newspaper article captured the polarities in Yugoslav perceptions of Pop art in the mid-1960s, arguably the most quintessential US art movement.Footnote1 Heavily influenced by US consumerism and popular culture, it utilized symbols and images that defined the everyday lives of US Americans. Yugoslavs not only saw Pop art as an art form, but also as a vehicle for transferring US (capitalist) values to European cultures. This paper examines the making and the controversial reception of four major Pop art exhibitions that took place in Yugoslavia between 1964 and 1969: the first one is the Pop Art exhibition of female Serbian artist Olja Ivanjicki, who was responsible for placing the language of Pop art in the spotlight for Yugoslav art critics in 1964; the second exhibition is New Figuration of the Belgrade Circle (1966), which brought together five Yugoslav artists and forced Yugoslav art critics to address the influence of US Pop art; the third is Pop Art (1966), the first exhibition to bring major US Pop artists, such as Mel Ramos, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol, to Yugoslavia; and the fourth exhibition is The New Vein: The Figure, which elicited the most mature Yugoslav responses to US art in 1969.

Conventional historical narratives of post-WWII art are heavily slanted towards the US, consequently overlooking the artistic production and art writing elsewhere in the world, including by Yugoslav artists and critics.Footnote2 The purpose of this essay is therefore twofold: it will not only offer new transcultural perspectives on the reception of Pop art in the 1960s, but also reflect on the significance of Yugoslav art to the art of the 1960s, in particular New Figuration.

Pop art acquired new, specific meanings in the Yugoslav context. To understand the dynamics of the assimilation of Pop art in Yugoslav art writing and practice, it is useful to draw on translation theory. As argued by Lawrence Venuti, a translation never reproduces the exact original; rather, translating is a selective and creative act, involving de-contextualisation, transformation, and re-contextualisation of the foreign into the local culture.Footnote3 Depending on the translator’s values (social, political, aesthetic etc.), s/he can either stress the cultural difference of the foreign text or suppress it. As a result, the meaning of the original source may change, and its degree of assimilation may vary because, as the literary theorist George Steiner asserts, the new cultural setting is never an ideologically neutral space but “already extant and crowded.”Footnote4 Applying such theoretical insights to the analysis of the four abovementioned exhibitions, we treat US Pop art as a “source text” that could be read and translated by Yugoslav cultural brokers (art writers, curators, artists) into new terms and idioms that could be understood by their Yugoslav audiences.Footnote5

The shifts in Yugoslav attitudes to Pop art in the mid-1960s, from outright rejection to sympathetic positions, are underpinned by the changing socio-economic context. After the 1965 economic liberalisation and the development of the so-called market socialism (a market-based system) in Yugoslavia, the country entered a period of developing consumerism, which would favour the arrival of Pop art imagery, based on consumer goods and bright advertising. As Yugoslavia opened to the world market, developed its tourism industry, and increased its port activities, the standard of living improved, and US culture influenced everyday life. In other words, Yugoslavia was slowly experiencing its own consumer revolution (termed “socialist consumerism”) and became increasingly industrialized.Footnote6 Tito’s government granted its citizens more personal freedoms, and the “freedom to consume” new experiences, forms of behaviour, and goods, including cars, the latest household appliances, fashions, a great variety of products to choose from the shelves in shops, which were advertised by the country’s expanding marketing and entertainment industry.Footnote7

To some degree, it is possible to align the Yugoslav openness to Pop art with the country’s opening to the West. However, Pop art’s presence in Yugoslavia also complicated and exposed the idiosyncratic situation that critics and artists struggled to make sense of: they lived in a single-party socialist state, ordered in accordance with communist ideologies, which however had opened to the West in the 1950s and had, under that influence, gradually adopted the principles of a consumer society. It has been argued that Yugoslavia’s openness towards Hollywood, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, comic books, Pop art, Coca-Cola, and jeans were a small price to pay for the benevolence of Washington and other Western centres, compared to more important ideological concessions.Footnote8 But the effects of this strategic opening towards US influences and values meant that many Yugoslavs developed a love-hate relationship with Western liberalism and the comforts of a capitalist consumer society. Although many felt a fascination for Western consumer goods and images, animosity grew amongst older generations and conservative members of society who viewed such imports as symbols of the “decadent” capitalist West, able to corrupt the socialist value system.Footnote9 Therefore, as this essay will demonstrate, Yugoslav reactions to US Pop art exhibitions resulted in highly politicized interpretations.

Pop Art (Olja Ivanjicki), Belgrade, 1964

On 1 October 1964, a large and curious audience gathered in the small Graphic Collective Gallery in Belgrade to see the exhibition of Olja Ivanjicki, one of the first Yugoslav artists who whole-heartedly embraced the language of Pop. Her exhibition Pop Art was a sensation for local audiences and took place shortly after the artist’s return from the US, where she had spent a year as a Ford Foundation scholarship recipient (1962–63).Footnote10

Ivanjicki exhibited around fifteen works: objects and installations, which she referred to as “suitcases.” They revealed her fascination with the concept of the ready-made and were perhaps the closest a Yugoslav artist had come to Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines at the time. The art critic Pavle Vasić identified a shared perception between Ivanjicki and the US artists of the 1964 Venice Biennale, where Rauschenberg had won the first prize.Footnote11 In her deconstruction of Pop art, Ivanjicki enriched foreign influences with domestic elements:

I was eager to create the epitome of the moment; however, it would refer to our reality, un-American, the world of our own surroundings. So, I began my quest for things discarded in streets, in old forgotten suitcases, in attics, basements and drawers.Footnote12

Ivanjicki collected and packed away discarded objects, such as Yugoslav newspapers she found in the street, so as to “eternalize the very essence of the things packed.”Footnote13 The Russian General’s Suitcase (1963, ), however, differed from the rest as it was not simply concerned with the recycling of mass-produced materials. It represented the remnants of Ivanjicki’s past and her Russian family heritage, containing such intimate things as old photographs and passports. On this work, Ivanjicki commented: “Pop art came with a specific meaning to me, laden with a sense of history and the stories of people that had once owned all those things.”Footnote14 Ivanjicki’s version of Pop then differed from US Pop art’s detached, or mechanical use of mundane objects from consumer society and popular culture.Footnote15 In this sense, Ivanjicki’s work is not a simple assimilation of Pop art but may be best understood with Venuti’s concept of domestication, as explained above. Alternatively, it may also be seen through the translation concept developed by the Brazilian poets and translators Haroldo and Augusto de Campos, who described translation as a cannibalistic and liberating form, in which the translation “eats, digests, and frees itself from the original.”Footnote16

Figure 1. Olja Ivanjicki, The Russian General’s Suitcase (Kofer Starog Generala), 1963, object, 50 × 90 × 20 cm. Belgrade, Olga Olja Ivanjicki Foundation.

Although Ivanjicki’s works are clearly more than an imitation of US Pop art, she explicitly declared herself to be a Pop artist in her announcement of the exhibition to the public, sent by Ivanjicki as a telegram to Belgrade’s popular newspaper Večernje Novosti on 28 September 1964: “I plan to arrive POP please wait for me at the Graphic Collective Gallery POP. On 1 October 1964, at 7 pm STOP Olja Ivanjicki – flowers are not mandatory.”Footnote17 Such a declaration was a highly unusual occurrence in Yugoslav art history, as previously artists’ identities were fashioned by the art critics. Ivanjicki’s playful dramatization of her arrival was a “Pop art” strategy, which embraced the telegram as a common form of communication to arouse the public’s interest. Ivanjicki presented herself as a “celebrity” and self-fashioned her own image as a young, mysterious, and exciting artist. The newspaper’s responded quickly, and the following day an interview was organized with the artist, which was promptly published. In it, Ivanjicki repeatedly stressed her new affiliation: “As you see, I've become a supporter of Pop art.”Footnote18

Pop art’s breakthrough in the Yugoslav press in 1964, then, was partly the result of the effort of a single Yugoslav artist, who brought this new artistic language home to Belgrade, a year after Rauschenberg had won the Grand Prize at the Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts in 1963, and three months after winning the Golden Lion for his silkscreen paintings at the 32nd Venice Biennale in June 1964. When Ivanjicki was asked by the reporter how long her exhibition would last, she responded enigmatically: “Ten days - no scandals.” Confused, the reporter followed up and Ivanjicki, foreseeing the potential shock effect of her exhibition, explained: “I hope that there will not be too many people, and that the audience will accept and understand Pop art, which is, truth be told, like all new things, a bit unusual.”Footnote19

According to newspaper reports, the public flocked to the gallery in large numbers so that “even a pin could no longer fit.”Footnote20 Poor ventilation, the hot air, and clouds of cigarette smoke did not deter this unusual gathering, which quickly turned into a heated debate between the artist and the public who enquired about Pop art and about what can be classified as art.Footnote21 Standing on the balcony of the gallery above the exhibition’s visitors, who fired question after question, Ivanjicki tried to defend her work. One visitor asked: “explain your Pop art, what exactly is it?” Another demanded: “how am I supposed to hang a suitcase on the wall?” A third asked: “what kind of art is that, when any one of us here could have made it?”Footnote22

The art critics filled the Yugoslav press with numerous negative, even mocking reviews. One critic mercilessly reduced the exhibition to a joke, warning visitors that “Going to the show, you will have to refrain from laughing.”Footnote23 Such responses were strikingly similar to the reception of Pop art in the US, where a portion of the public also saw it as some sort of joke and certain critics excluded it from serious consideration.Footnote24 Ivanjicki later gave an account of her experience during that time: “The rejection, public mockery, and countless other reactions caused by my exhibition created an atmosphere of a kind that will not be seen again in Belgrade in a long time. It seems that Pop art will not be easily forgotten.”Footnote25

One reason for the hostile reception of Ivanjicki’s exhibition may have been her gender. The idea that a woman should be at the forefront of the most progressive artistic trends in Yugoslavia would have been offensive to many critics in a generally male-dominated art world and patriarchal society. Ivanjicki’s treatment seems manifestly unfair in comparison with that of Robert Rauschenberg, whose works were quickly embraced by the Yugoslav public and critics.Footnote26 Another reason for the harsh criticism was the perception of Pop art as a threat to Yugoslav art and society as a whole. Unsurprisingly, the harshest reviews of Ivanjicki’s works were authored by art critics writing for the party paper Borba. Dragoslav Djordjević neglected to mention Ivanjicki by name or her exhibition altogether, focusing instead on a general diatribe against US Pop art, which he harshly dismissed as “neither popular, nor art.”Footnote27 Comparing it unfavourably to Dada, he wrote: “The inventory from the previous protests by the Dada movement is used once again in Pop art,” but “without the bitterness and nihilistic negation,” only “with a certain irony hidden under the mask of indifference.” For Djordjević, Pop art lacked originality and was “self-pleasing and self-contained,” and therefore he judged it to be a short-lived phenomenon “without any lasting consequences except for on the nerves of its observers.”Footnote28

Translation theorists often highlight the translator’s relation to their potential or desired readership: the translator should consider it his task to satisfy his readers’ expectations.Footnote29 With this in mind, Djordjević’s remarks, published in a paper that was read religiously by Communist party members, function as a reassurance that this undesired art from the US would soon disappear from leading galleries and museums in Yugoslavia and beyond. He did not mention any of the Pop artists by name, other than a brief reference to Rauschenberg and Johns in the last sentence. In doing so, Djordjević created an image of Pop artists as a foreign entity in the Yugoslav mind, preventing any further familiarization between the original source of translation and his readers.

Djordjević’s attack of Pop art in Borba was followed ten days later by the art critic Božidar Timotijević’s review, entitled “Pop art or the Vulgarization of Art,” which condemned Pop art as a representation of Western decadence. Speaking of an “invasion” and “conquest,” he cast Pop art as an enemy who had

entered Yugoslavia through a back door, was met by astonishment, dilemmas and clamour, as if it were not a normal consequence of events and directions in art that had already made themselves at home on our soil, events which had smoothly and without much resistance passed and had been gulped down by our starvelings seeking originality at any cost.Footnote30

Timotijević condemned both Ivanjicki and others for their fascination with Pop art, which he perceived as a lack of criticality towards it. Considering this to be an inevitable consequence of the Americanization of Yugoslav culture, he called for the public’s resistance to this foreign cultural import. Similar beliefs were shared by writers and cultural commentators in England at the time, such as Richard Hoggart, who in The Uses of Literacy (1957) pointed to the “decadent” Americanization of Britain and critiqued the mass-cultural diaspora hastening across the Atlantic to “ruin the morals of our nation’s young.”Footnote31 Timotijević turned the US Pop artists into a bizarre and deviant group of “young men who are perfectly content in their world made of neon, industrial goods, Coca-Cola, advertisements, and sex.”Footnote32 Such clichéd perceptions of the US as unsophisticated, morally corrupt, and vulgar were shared by other critics, who had attacked Ivanjicki for being “the one name exclusively tied to Pop art in Yugoslavia” and a harbinger of Western decadence.Footnote33

The offense caused by Ivanjicki’s affiliation with US Pop art becomes clear when we compare her Pop art exhibition with the (untitled) exhibition of the same artworks that took place six months earlier at the theatre Atelje 212 (Atelier 212) in Belgrade. It was seen by around 2,000 people but was not covered by the press and did not provoke any outrage from the public.Footnote34 The contrasting reactions to the two exhibitions of the same works suggest that it was Ivanjicki’s identification with US Pop art that resulted in hostile responses.Footnote35 Yugoslav critics were arguably most offended by the fact that an art movement embodying capitalism was apparently wholeheartedly adopted by a female Yugoslav (communist) artist. Ivanjicki’s new “foreign” identity and open declaration that she had now become a Pop artist was understood as an acceptance of US (counter)culture, as a testament to the allure of “decadent” US capitalism, and as a betrayal of Yugoslav Socialist Modernism supported by the state.

In stark contrast to the Yugoslav writers’ hostile attitudes towards Ivanjicki, an article written a year later by the US art critic David Binder for The New York Times offered a more favourable view.Footnote36 He focused on the fact that nobody in communist Yugoslavia wanted to buy Pop art. Referring to Ivanjicki as the leading Pop practitioner, he quoted her stating: “In the US, the Pop artists get money. Here, I get only newspaper articles.” This was a bold statement for a communist artist to make in 1960s Yugoslavia, especially when considering the fact that Ivanjicki lived and worked in a government-sponsored studio project. The article explained that Ivanjicki earned her living with “normal” paintings, and she had only succeeded in selling certain paintings that represented a “slightly modified” Pop. Ivanjicki, undeterred by the negative publicity or the lack of sales, continued to participate in neo-avant-garde developments, and even pioneered Performance art, Happenings and Body art in Yugoslavia during the 1960s.

New Figuration of the Belgrade Circle, Belgrade, 1966

The 1966 exhibition of works by Ivanjicki, Dušan Otašević, Dragoš Kalajić, Radomir Reljić, and Boleta Miloradović further elucidates the Yugoslav relationship with Pop art.Footnote37 It was curated by the Serbian art critic Djordje Kadijević, who identified a shared spirit amongst this group of young Belgrade artists. In 2001, the art historian Lidija Merenik retrospectively argued that together they represented the Serbian Pop art of the 1960s, which illustrates that later art historians have no objections to apply the term “Pop” to Yugoslav artists.Footnote38 Indeed, the exhibited artists were working in idioms close to Pop art; as we have seen above, Ivanjicki had adopted the term to describe her work and persona, and Otašević had called Pop art a “strong wind from America blowing through slumbering Europe,” indicating their admiration for the novelty of US Pop art.Footnote39

The Belgrade New Figuration employed aesthetics and techniques that relate to Pop art, in particular its playful nature and use of mass-media images, as a vehicle to challenge the traditions of fine art and address socio-political issues. They rejected the dominant understanding of “high culture” in Yugoslavia and the official Socialist Modernism or Socialist Aestheticism promoted by the state, while also reacting against the dominance of abstract art and Informel painting. Instead, they favoured a socially engaged art, which could at times be interpreted as ideological or political.Footnote40 Although their work displayed limited stylistic similarities, it was characterized by a collective turn to figuration, an active search for new forms of expression, as well as a reaction to the recent invasion of consumer culture in socialist Yugoslavia.

Rather than merely tracing stylistic and iconographic borrowings from US Pop art in New Figuration, it is arguably more productive to speak of a “confluence” of ideas. The paintings Ivanjicki exhibited in 1966 were radically different from her earlier work shown in 1964. They generally resonated with that of other contemporary US artists such as Andy Warhol, but also with diverse European artists who used the pictorial strategies of Pop as a form of critique of US hegemonic power, such as Wolf Vostell in Germany, Per Kleiva in Norway, or the Spanish collective Equipo Crónica. For example, Vostell’s deceptively titled picture Miss America (1968) is a shocking image critiquing the brutality and injustices of the Vietnam war. Similarly, Kleiva’s screenprint American Butterflies (1971) brings to mind newspaper photographs of the Vietnam war. Equipo Crónica’s work, such as The Surrender of Torrejón (1970), functions as an ironic critique of the Spanish-US relations, particularly the pact that enabled the US to establish four military bases in Franco’s Spain in return for economic aid.

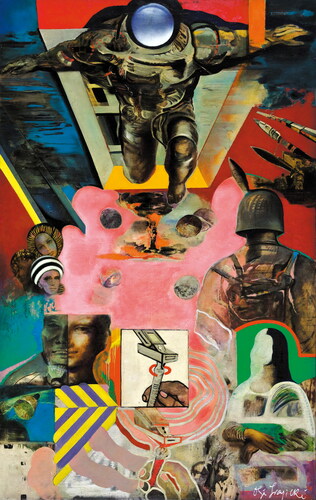

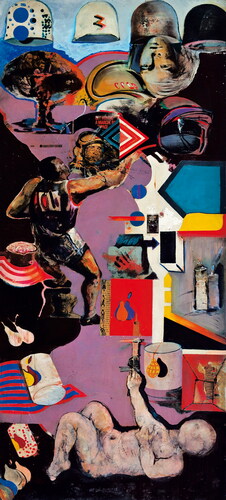

Ivanjicki’s works were also political. They focused on concerns over escalating Cold War conflicts, with references to themes of war and suffering: a nuclear explosion is depicted in the centre of Something in Life is as Sharp as a Razor Blade (1965, ), while in Small Mousetrap for Big Things (1965, ), a photograph of innocent people appears to emerge out of an atomic explosion. Further references include a painted USSR army helmet, a US American army soldier and the depiction of several missiles and hand grenades. These sombre motifs contrast with seemingly banal and more mundane themes: Ivanjicki depicts a schematic male hand holding a razor in Something in Life is as Sharp as a Razor Blade, whereas in Small Mousetrap for Big Things, she references women’s fashion through images taken from a women’s magazine advertisement of models wearing different hats.

Figure 2. Olja Ivanjicki, Something in Life is as Sharp as a Razor Blade (Nesto u životu je ostro kao žilet), 1965, oil on canvas, 220 x 143 cm. Belgrade, Olga Olja Ivanjicki Foundation.

Figure 3. Olja Ivanjicki, Small Mousetrap for Big Things (Mala mišolovka za velike stvari), 1965, oil on canvas, 105 x 65 cm. Belgrade, Olga Olja Ivanjicki Foundation.

An effective comparison can be made between Ivanjicki’s paintings and James Rosenquist’s monumental 23-panel painting F-111, a cornerstone of the Pop art movement dating from around the same time in 1964-5. The similarities in both subject matter and style are striking: Rosenquist had also contrasted images of doom (including the same nuclear mushroom cloud) and desire (in Rosenquist’s case this was cake, in Ivanjcki’s women’s fashion). Both artists use large sections of eye-grabbing flat planes of bold primary colours and patterns, and disorienting combinations of collaged everyday visual motifs that are placed on top of each other, as seen in advertising. While the scale of Rosenquist’s painting is unprecedented, Ivanjicki’s paintings were also unusually large: Something in Life is as Sharp as Razor Blade measures 220 × 143 cm, and Small Mousetrap for Big Things stands impressively at 300 × 100 cm. The dimensions perhaps referenced, much like Rosenquist’s, the large scale of advertising billboards that she would have seen during her visit to the US a few years earlier. The obvious similarities between their works respond to a shared desire to address the immediate reality and concerns central to many artists and their audiences globally at the time: the fear of nuclear war, consumerism, and the increasing interference of advertising in everyday life.

Dušan Otašević was one of the first Yugoslav artists to respond to the new forms of mass-production and consumerism, which by 1966 had begun to exert real influence on the way of life in Socialist Yugoslavia. Clean white, Otašević’s work (1969) displayed his fascination with advertising in Yugoslavia, most notably for hygiene products, such as soaps, detergents, and toothpaste. In this monumental work (200 × 500 cm), Otašević suggests a process of applying shaving cream in a sequence of images, with the foam growing in volume until it completely covers the brush. By turning to advertising, printed media, hand-painted artisan shop signs, street signage, comics, banners, and posters for inspiration, Otašević clearly distanced himself from the high art taught at the Academy, where he was still a student in 1966.Footnote41 In his own words: “Commercial art, which could be seen at the beginning of the formation of consumer society in our country [Yugoslavia], appealed to me because of its naïve immediacy and freedom from any knowledge about art.” Footnote42

Otašević’s works were the most radical in the Belgrade exhibition. Large in scale, they illustrated his fascination with everyday objects and mundane tasks, such as food and eating, cigarettes and smoking: Polyptych 1 (1966) represented the four stages of lighting a match. They addressed the visible “symptoms” of the Americanization of Yugoslav culture, such as the increasing popularity of cigarettes. As Otašević himself noted, he was inspired by Hollywood movies, where “all the heroes smoked.”Footnote43 Smoking featured heavily in his works, such as Diptych (1966) which features a closed mouth with a cigarette in one frame and an open mouth blowing out cigarette smoke in another. It was not only the content of his work that was unprecedented in Yugoslavia, but also his stylistic treatment, as evidenced by his flat, uniform application of bright primary colours and use of household paint on wood.

While his works referenced both Western trends and consumerism, they also highlighted the convergence between a new consumer culture—which developed from a different political and economic system than that in the US—and the Yugoslav uncertain attempts at realising it.Footnote44 Otašević’s fascination with the hand-painted signs of the few private businesses permitted in socialist Yugoslavia, such as bakeries and barber shops, was reflected in his own creative process, which differed from that of the Pop artists, who usually relied on mechanical reproductions. In contrast, Otašević did not eliminate the artist’s hand, but instead went through a meticulous process of sawing, welding and painting his artworks. Moreover, and in an ironic allusion to the notion of industrial processing and the consumption of artworks, Otašević referred to his own works as “Otašević processed goods.” One interpretation is that Otašević tried to invert Pop art’s approach, in order to challenge the capitalist association of work and production with dehumanisation, alienation, and reification.Footnote45 The art historian Branislav Dimitrijević argued that Otašević’s creative process was symbolic of the economic reforms of 1960s Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which set out to link aspects of capitalist production with socialist ideology (i.e. to overcome the capitalist fetishising of goods over labour, and link production and consumption in a more humane way).Footnote46 By placing his work in the wider Yugoslav socio-economic context, we can begin to understand Otašević’s work as distinct from that of his Western counterparts who used the style of Pop.

Another crucial difference between Otašević’s work and that of US Pop artists is that he did not represent branded goods, such as Coca-Cola bottles, but deliberately ignored the symbols of global consumerism and popular culture that had filled the Yugoslav media space by 1966. Rather, his artworks represented generic consumer goods and the mundane acts associated with them, such as licking an ice-cream in Yes Sir! (1966).Footnote47 Otašević’s works also featured prominent figures from the Yugoslav context, such as Tito and Lenin, which he turned into icons, using the language of Pop art. For instance, Towards Communism on Lenin’s Course (1967) portrays Lenin in a characteristic speech-giving pose, based on a poster that Otašević had obtained on a trip to the USSR. Lenin points towards the five-pointed communist star, painted on the left, while to the right a traffic sign prohibiting right turns was taken from the real world. By adapting Pop art’s expression into the Yugoslav communist narrative, i.e. depicting Lenin in the style of Pop art, Otašević opens up several lines of interpretation, ranging from playful humour, through intentional parody, to sharp criticism.Footnote48

A powerful example is Comrade Tito, White Violet, All Our Youth Loves You (1969, ), handcrafted from timber and aluminium panels. The President of Yugoslavia had first featured in a British Pop installation Collage of the Senses by Group 2 (Richard Hamilton, John Voelcker, John McHale) for the This is Tomorrow exhibition (Whitechapel Gallery, 1956). Group 2 had used a blown-up photograph of Tito to create their collage, while Otašević depicted Tito in an almost comic, cartoon-like manner in an arrangement that recalls a common scenography of socialist festivals celebrating Tito and the Party, such as the May Day Parade.Footnote49 Tito is flanked by references to the national flag and the communist party flag, with an “empty” five-pointed star (the symbol of the communist party) hovering above. Behind the composition is a heart-shaped panel with a repetitive flower motif, reminiscent of wallpaper. The title of the artwork is taken from a well-known patriotic song, expressing the people’s unconditional love of their leader, Tito.Footnote50 It is clear from a later quote by Otašević that his work was bound up with Yugoslav politics, as he openly stated how “some of my work from that period came into being as a result of my opposition to the ruling socialist ideology in Yugoslavia.”Footnote51 Given the kitsch aura of the work and the subsequent absence of any attempts at a heroic representation of Tito, the artwork was seen as an unofficial representation of the leader and was later (rightly) read as a critique of the system.Footnote52

Figure 4. Dušan Otašević, Comrade Tito, White Violet, Our Youth Loves You (Druže Tito, ljubičice bela, tebe voli omladina cela), 1969, painted wood, aluminium, 488 x 348 cm. Belgrade, Muzej Savremene Umetnosti.

The exhibited work of the third artist, Dragoš Kalajić, commented on the all-pervasiveness of mass culture and intrusion of mass-media (film, television, advertising) in everyday life at the time. In 72.5% Diary 178 (1964), Kalajić depicted forty-eight separate television-like or comic-book rectangles, referencing the invasion of media in daily life and the accumulation of new impressions. The inclusion of “diary” (dnevnik) in the painting’s title may reference either the television news programme, the daily newspaper of the same name in Serbia and Slovenia (founded in 1942 and 1951 respectively), or the act of keeping a diary (in this case in the form of a painting), since the word dnevnik in Serbo-Croatian and Slovenian denotes both things. Each frame tells a separate story: some are filled in with bold colours, signs or symbols, such as the red star of the Yugoslav flag or the heart symbol. Other frames feature the cover of the fashion magazine ELLE, a map of Serbia, a nuclear explosion, and a rich amalgamation of abstract images and patterns. The art critic Ješa Denegri described his work at the time as a “painting-essay,” in which Kalajić consciously disregarded his own subjective affinities and became an objective “reporter” striving for “a noble and conscious depersonalisation” rather than a personal view of contemporary events.Footnote53

Despite the strong stylistic and thematic affinities with Pop art, both the exhibition’s curator Kadijević and some of the exhibited artists openly aligned their work with the European revival of figuration in the 60 s, referred to as New Figuration, which they believed to be superior to the work of Pop artists, as they appear in the US. It is important to note that, unlike recent art historians, such as Merenik, who applied the stylistic category of Pop art to these artists, Kadijević rejected this label in 1966. Kalajić had just graduated from the Accademia delle Belle Arti in Rome, which allowed him to forge strong links with the Italian New Figuration. Similarly, Otašević later also positioned his work within the European context: “I did not declare myself a Pop artist, although my works from that period do feature some elements of American Pop art. I felt closer to European New Figuration because of its more complex choice of topics.”Footnote54

The term New Figuration (Nouvelle Figuration) was first used by the French critic Michel Ragon in 1961, who had promoted it as a supposed “third way” between abstraction and the Nouveau Réalisme promoted by Pierre Restany, which maintained closer ties with Dada than with Pop art.Footnote55,Footnote56 The first New Figuration exhibition, Une Nouvelle Figuration, was conceived by the gallerist Mathias Fels in Paris in 1961, at a time when “the Parisian galleries completely shunned everything that was not abstract.”Footnote57 Instead, Fels brought together an international and heterogeneous group of young figurative artists, such as Nicolas de Staël, Asger Jorn, Alberto Giacometti, Karel Appel, Francis Bacon, Enrico Baj, Paul Rebeyrolle, and Jean Dubuffet. The movement was not limited to Europe, as the art historian Patrick Frank has recently shed light on the movement’s presence in Buenos Aires.Footnote58 Belgrade’s New Figuration emerged in 1963, thus making it contemporaneous with other leading art centres in Europe and beyond.

The Yugoslav’s rejection of the Pop art label (with the notable exception of Ivanjicki) is even more remarkable when we consider that during the 1960s in neighbouring Hungary, local art historians such as Lászlo Bekein had unanimously labelled most (non-socialist realism) figurative artistic tendencies as “Pop.”Footnote59 Was this a sign, then, that the Yugoslavs did not wholly buy into the idea of New York having replaced Paris as the capital of modern art? Did they join the many other Eastern European artists who, as argued by Piotr Piotrowski, “still believed that the capital city of international contemporary art was Paris.”Footnote60 In the preface of the exhibition catalogue,Footnote61 Kadijević compared the Yugoslav and European New Figuration, arguing that they responded to the perceived frivolity and lack of criticality of US Pop art:

With few exceptions, in the works of our representatives of New Figuration there has never been such extreme radicalism in denying tradition and finding bizarre modes of expression as we can find in American Pop art. As an expression of the specific conditions of a highly developed industrial civilization, American Pop art symbolically expresses a painful powerlessness to defend the work of art from the aggression of the banal, utilitarian industrial object that oppresses it and that threatens to take up the dominant position in the hierarchy of values. The European artist, however, looks at the previously mentioned relationship between the object and the work of art with a curiosity that is filled with malicious schadenfreude at the order of the contemporary world. He seems, in contrast to his American contemporaries, to start from a deliberate reduction of a work of art to a banal object, enjoying its dethronement.Footnote62

Yugoslav artists were not interested in simply capturing, elevating or glorifying the banal reality or ordinary things in life to the level of high art, but wished to comment on changes in the world, whilst also dethroning high art itself and revolting against earlier painting conventions.Footnote63 As put by Kadijević, “the object itself (that is, its artistic projection on the canvas) is not the end goal of New Figuration painting,” instead, the painted object is symbolic of the “contradictions of the contemporary world,” and filled with “fear, revolt and irony.”Footnote64 Kadijević saw this as the direct result of the Yugoslav artists’ interest in existentialism, and asserted that the work of the Belgrade Circle was more aligned with the existential question that was present in European figuration but neglected by US Pop artists.Footnote65

Another reason why Kadijević and other critics aligned the Yugoslav artists’ work with Paris as opposed to New York, may have been the publication of Lucy Lippard’s influential book Pop Art, popularized in Yugoslavia by its translation into Serbo-Croatian in 1966. Crucially, while Lippard acknowledged Pop art’s presence in places other than the US and Britain, she and other art historians of the period, such as Suzi Gablik, dismissed these practices as “unconvincing,” “imitative” and “incompetent,” claiming that Pop art was uniquely American and British.Footnote66 A similar view was voiced by the art historian Marco Livingstone in 1990: “Pop could flourish only in highly industrialized societies, and therefore there has been no direct pendant to this movement in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe or the communist China.”Footnote67 While even as late as 2003, Pop art was still described as a Western phenomenon, as in Tilman Osterworld’s Taschen book Pop Art: “Pop is entirely a Western cultural phenomenon, born under capitalist, technological conditions of an industrial society.”Footnote68 Back in 1966, Lippard brashly asserted that “Hard-core Pop art is essentially the product of a long-finned, big breasted and one-born-every-minute American society.”Footnote69 In keeping with this reading, Kadijević disregarded Pop art for “inappropriately disrespecting the aesthetic sanctities that are the basis of the traditions of Western European art,” referring to Pop art’s glorification of popular culture and kitsch.Footnote70

However, Kadijević’s attempt at distancing the Belgrade Circle from Pop art was countered by other Yugoslav critics at the time, who pointed out the obvious similarities with US Pop art. Writing for the art journal Umetnost (Art), Slobodan Ristić asserted that Otašević’s work was more aligned with US Pop art than with European Figuration, since it possessed an ambiguity much like that of the Pop artists.Footnote71 Ristić argued that Otašević made it difficult for the viewer to discern whether his work should be understood as a form of irony, as a veiled revolt, or simply as a neutral art without any illusions or allusions.Footnote72 Similarly, the art critic Marija Pušić wrote of Pop art’s influence on the work of Otašević, in particular Pop art’s ironic or sarcastic intonation. She argued that Pop art’s influence was instrumental in introducing a novel relationship between the author (artist) and the banal or ordinary objects represented–the “subtexts” that impregnate the artworks.Footnote73 Pušić further commended Otašević for his new take on Claes Oldenburg’s humour and his oversized depiction of everyday objects. Otašević’s originality, she asserted, lies in his immediacy of observation and ability to communicate ideas into signs with irony and clarity, such as the passing of time through the life and fate of a matchstick in Polyptych I. As pointed out recently by Dimitrijević, this work actually echoed Roy Lichtenstein’s mini-narrative Step-on Can with Leg (1961), which depicted the daily ritual of opening a pedal bin in a sequence of two serial comic-book style frames.Footnote74

US Pop Art Arrives in Yugoslavia: Pop Art in Zagreb and Belgrade, 1966

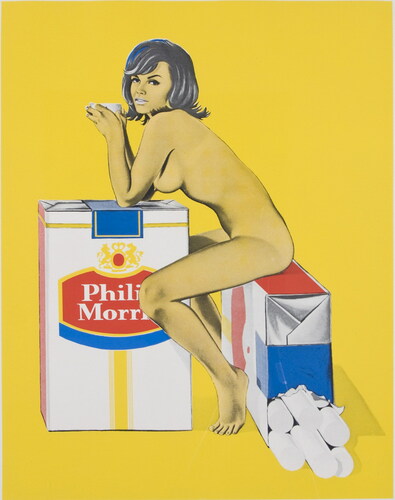

In March 1966, just a few weeks following the exhibition New Figuration of the Belgrade Circle, Yugoslavia became the first Eastern European country to host an exhibition of US Pop art. Pop Art was first shown in Zagreb’s Gallery of Contemporary Art (8–22 March) and then in Belgrade’s Museum of Contemporary Art (25 March–8 April).Footnote75 While the Belgrade catalogue consisted of only four pages, the Zagreb catalogue included a preface written by the Croatian art historian Boris Keleman. In an attempt to place Pop art within a wider art historical context and relate it to the kind of art with which the Yugoslav public was already familiar, Keleman concluded that Pop art “neither rejects abstraction nor means a return to figuration, it has already conquered a new area where earlier development is not devalued.”Footnote76 The exhibition featured a total of thirty-three eye-popping works, predominantly screen prints and a few lithographs, by an all-male line up of eleven major British (Peter Phillips, Gerald Laing, Allen Jones) and US American (Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine, Tom Wesselmann, James Rosenquist, John Wesley, Mel Ramos, and Allen D’Arcangelo) Pop artists. What set this exhibition apart from most other US art exhibitions shown in Yugoslavia was that it was commissioned and sponsored by the cigarette manufacturer Philip Morris, rather than by a US gallery or museum. It was dominated by imagery drawn from popular culture, including images of pin-up girls, comics, advertising images of consumer products, such as cars, TV’s and, of course, Phillip Morris cigarettes, aligning with Richard Hamilton’s proclamation of Pop art as “young, sexy and Big Business.”Footnote77

The exhibition was conceived and curated by the US art historian and critic Max Kozloff, which is somewhat ironic, because Kozloff had a personal dislike of most Pop art.Footnote78 He had previously criticized Pop art collectors and art galleries for embracing “the pin-headed and contemptible style of gum chewers, bobby soxers, and worse, delinquents,”Footnote79 and his later seminal essay “American Painting During the Cold War” for Artforum magazine discussed the US use of art in terms of cultural imperialism within the context of Cold War politics.Footnote80 Kozloff was therefore not only an observer “exposing the ties between power and paint,”Footnote81 but he was actively involved in promoting Pop art on the world stage,Footnote82 and was thus an active participant in what he later called America’s benevolent propaganda.

The artworks that Kozloff selected were characterized by an ambivalence and ambiguity towards consumer society and a disinterested engagement with consumerism and mass media images. Mel Ramos’ Miss Comfort Crème (1965) depicted an idealized nude woman leaning against a tube of Comfort Crème; a similar interest in the eroticised imagery in advertising can be seen in Wesselmann’s images of nude girls, which resemble pin-up girls or models from magazine centrefolds. Andy Warhol’s three screen-prints Jackie I, II and III (1965) focused on images of the grieving widow at John F. Kennedy’s funeral ceremony, taken from newspapers and magazines. Lichtenstein’s work took images from comic strips and blew them up to huge formats; Dine depicted fragments of ever-growing consumerism, such as cut-outs of women’s fashion magazines; Rosenquist and Phillips displayed an interest in industry and industrial products, such as propellers and various car parts; D’Arcangelo’s works depicted nonsensical road and traffic signs. The sleek, colourful and appealing prints represented a radically different version of Pop art from the earlier Neo-Dada works by Rauschenberg and Johns, or the assemblage “suitcases” of Ivanjicki.

This was the first artistic sponsorship by Philip Morris, which intended to use the artistic collaboration to promote its products and penetrate into new markets, as well as to reinforce its brand as part of avant-garde culture, promoting freedom of expression and US capitalism to countries abroad.Footnote83 Indeed, several artworks of the Pop Art exhibition “advertised” the company’s products: Mel Ramos’ screen-print Tobacco Rose () featured a pin-up woman sitting on a pack of Philip Morris cigarettes, while Jim Dine placed a cut-out of Marlboro cigarettes at the centre of his screen-print Awl. The company’s investment in Pop Art was worthwhile, as Philip Morris became the leading cigarette provider in Europe and Latin America where these works of art had toured.Footnote84

Figure 5. Mel Ramos, Tobacco Rose, 1965, screen print on paper, 60.96 x 50.8 cm. Washington D.C, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Rochelle Leininger for the Mel Ramos Estate.

An official letter, found in The Archive of Yugoslavia, from the American Embassy to the Yugoslav Commission for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries reveals that the US proposed the exhibition and that the Yugoslav Commission initially rejected it, indicating that its exhibition plans for 1966 had already been fixed and that a venue was not available. In the margins of the letter, a handwritten note by a member of the Commission reads: “Check with Protić [Miodrag B. Protić, the Director of Belgrade’s Museum of Contemporary Art], so that we can agree on an answer. Of course, there cannot be any involvement from our side.”Footnote85 As this exhibition was fully sponsored by Philip Morris, the Yugoslav Commission probably questioned the appropriateness of collaborating with a capitalist corporation and helping it to shape public taste in art in Yugoslavia, making this the actual reason for its initial rejection.

The exhibition happened thanks to Protić, who accepted the exhibition for the Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) and stipulated its showing in other Yugoslav centres (Zagreb, Ljubljana, and Skopje). The fact that the venue and the question of funding did not, in the end, present any insolvable problems suggests that the actual reason for the Commission’s initial rejection may have been ideological. By contrast, Protić seized the opportunity to shape the reputation of the new MoCA (which had only been inaugurated on 20 October 1965) as a “mecca” of Western modern art by admitting leading US Pop artists and their vibrant, young and exciting artworks into its spaces.

In comparison to the previous negative reception of Ivanjicki’s Pop Art exhibition, the Yugoslav press responded more favourably to Pop Art in 1966, especially its artistic value. Even though the exhibition catalogue clearly acknowledged the corporate giant Philip Morris as the sponsor, this fact was only mentioned by the Yugoslav art critic Irina Subotić, who also curated the exhibition in Belgrade’s MoCA. Other critics did not pay attention to the sponsorship. In an interview in 2017, Subotić explained that, while she was aware of the exhibition’s sponsor, for her, the political, commercial or propagandist aspects of the exhibition were of secondary importance to its artistic value and educational role in introducing the Yugoslav public to the most recent artistic practices happening outside their country.Footnote86

A recurring theme in Yugoslav responses to the artworks in Pop Art was the belief that they represented a critical reflection on a society dominated by advertising and mass media, rather than a celebration of it. Regardless of the artists’ intention, Yugoslav art critics decidedly rejected Pop art’s ambiguity and irony. Instead, Yugoslav art critics domesticated US Pop art by imbuing it with new meanings and forcibly imprinting their own beliefs, rather than attempting to come to terms with its original meanings and intentions.

In their reflections on the Pop Art exhibition, the Yugoslav art writers translated Pop art as a struggle against capitalism, where Pop artists were unable to defend themselves from the production-consumption cycle, which had come to dominate their lives. Subotić noted that although the Pop artists responded to certain phenomena of the modern world such as automatization, mechanization, urbanization, etc. with a dose of humour and irony, they did not manage to hide “a certain fear of the total destruction of the core of humanity.”Footnote87 Similarly, the art critic Djordje Kadijević understood Pop art’s detached use of consumer goods as art-forms to be a warning against the dangers of mass production culture and the effects of consumerism.Footnote88 An irony was “detected” in Roy Lichtenstein’s artworks by the art critic Bogdan Tirnanić, which he understood to be directed both towards the comic as a means of mass communication, as well as the world it depicted.Footnote89 In other words, Yugoslav writers made Pop art “acceptable” to their receiving culture by setting up Pop art works as possessing a critical take on the US/capitalist way of life, and leaving no space for any other interpretation of their work as complacent, passive, and especially not as celebratory.

Other critics adopted a different, foreignizing strategy in their translations of Pop art. Dragoslav Djordjević, who had previously used Ivanjicki’s exhibition as an opportunity to criticize US Pop art, returned with a more favourable review of the 1966 exhibition. Almost as an apology for his previous attack of Pop art, Djordjević explains how Pop art had been a heated topic of discussion in Yugoslavia at a time when information about it was limited.Footnote90 While he had previously dismissed Pop art as a short-lived phenomenon, now he stated the exact opposite: “[Pop art] is truly popular because its source and refuge can be found in the same place, in life,” and “we cannot deny Pop art its modernity and actuality, and a historically justified place in the history of art.”Footnote91

Why did Djordjević change his position between 1964 and 1966? The art historian Radina Vučetić pointed out that Djordjević, a conservative art critic writing for the party paper Borba, had a limited understanding of the contemporary movements but an instinct for knowing the appropriate moment to attack US art.Footnote92 She therefore attributes his favourable review of Pop art in 1966 to an equally favourable moment for US-Yugoslav relations, as Tito’s reforms towards market socialism, further decentralization and self-management sent a clear message to the US that Yugoslavia was increasingly distancing from the Soviet model. While this is a valid point, we must not forget the difference between the two exhibitions: in 1964, Pop art had been adopted by a Yugoslav artist, which was understood as a threat to the Yugoslav sense of artistic identity and communist values that Djordjević defended.Footnote93 Djordjević was writing from an equally ideological standpoint in his seemingly positive review of the 1966 Pop Art exhibition of US artists. In fact, by employing a “foreignizing” approach in his interpretation of the artworks, he emphasized the cultural differences between Yugoslavia and the US, stressing the strangeness of Pop art’s presence in Yugoslavia, and thus preventing its full assimilation in the local context. In other words, Pop art is acceptable as long as it can be clearly identified as foreign. Djordjević maintains that the rise of Pop art is specific to the US and that it is completely out of context in Yugoslavia, echoing the previously mentioned art writers Lucy Lippard and Suzi Gablik. Djordjević calls Pop art an “artistic expression of a highly developed technical civilization of the twentieth century,” an art made for today’s “over-busy and disinterested modern man,” who has “very little free time to visit galleries or museums, attend concerts or read the Classics,” since, according to Djordjević, “free time today is one of the most expensive articles of mass consumption.”Footnote94 In other words, Pop art was not intended for his supposedly refined Yugoslav readers but the other “less fortunate” lowbrow souls who are the product of capitalism and the US way of life.

The most hostile review of Pop Art, provocatively entitled “Pop art (that’s right!) in Belgrade” was written by the Croatian art critic and Informel painter Eugen Feller for the newspaper Republika (The Republic). Unlike Djordjević, who wished to keep US Pop art at a distance but still had some words of praise for it, Feller fiercely attacked the presence of Pop art in Yugoslavia and its effects on the Yugoslav public, even going as far as to compare it to the Asian flu or the English smallpox, which “has gotten under the Yugoslav skins.”Footnote95 He warned that “we are not aware that this Pop art is not just Pop art, but a mentality, a view on the world, on life, on society.”Footnote96 Feller placed US Pop art and its dehumanising aspects in direct opposition with the Yugoslav environment and aspirations. His stance powerfully highlights Yugoslavia’s problematic relationship with US culture, which is often regarded as insidious to imperialistic influence with the potential threat of subjugating the Yugoslav sense of identity and their moral, cultural and societal worldview.

Considering the highly sexualized content of the exhibition, it might seem surprising that only one art critic (indirectly) addressed issues of gender and sexuality in his review. The art critic Tirnanić argued that the works of Mel Ramos parody US advertising firms. He underlined their “artistic banality and their simplified psychology of acting on the consumer,” alluding to the use of sexualized women and sex appeal in advertising to sell products, as exemplified in Ramos’ Tobacco Rose ().Footnote97 In contrast, the other art critics consciously ignored the US artists’ overt references to and use of sex appeal, clearly geared towards the male gaze. Considering socialism’s repression of sex and sexuality and the fact that such images of nude women were not (yet) a normal or everyday occurrence in Yugoslav media, art or visual culture, it is perhaps understandable why Yugoslav critics decided to overlook the problem. It is no coincidence that around the same time several Yugoslav artists became increasingly critical of socialism’s repression of sex (as well as capitalism’s commodification of it), such as the black wave filmmaker Dušan Makavejev in his film WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971).Footnote98

However, if we dig a little deeper, we may identify another factor that would have made it difficult for Yugoslav writers to address such images. Namely, as argued by the historian Patrick Patterson, advertising in Yugoslavia increased dramatically by the mid-1960s and attempted to emulate circumstances and values that prevailed in the West by centring around the woman’s sex appeal.Footnote99 In his study of advertising in Yugoslavia, Patterson alluded to one such example: an advert for a “Castor Končar” washing machine created in 1969. It featured an attractive young woman looking up at the reader alluringly, leaning against a washing machine with one shapely leg extended to the side.Footnote100 When placed in the Yugoslav context, therefore, Ramos’ works exposed Yugoslavia’s increasingly idiosyncratic and conflicting environment, which not only tolerated, but also encouraged the growth of a “consumer society.” Since the East began to resemble the West, and Yugoslav art writers lived and worked in a male-dominated socialist establishment that increasingly catered to the purchasing power of men, the idea of the woman as the object of the male gaze was not too distant from the idea of the woman as an object of consumption.

The New Vein: The Figure 1963–1968, Belgrade, 1969

The debate on the superiority or dominance of European vs. US art was also strongly present in the reception of the 1969 touring exhibition The New Vein: The Figure 1963–1968, which was sponsored by The International Art Program of the National Collection of Fine Arts at the Smithsonian Institution. The exhibition was conceived by Constance M. Perkins, an art history professor at the Occidental College in Los Angeles, who also curated art exhibitions and lectured for the US State Department to explore the meanings of figurative art in the context of the predominance of Abstract Expressionism.Footnote101 The first stop on the exhibition’s itinerary was Belgrade’s MoCA (30 December 1968–3 February 1969), where, according to Vučetić, the exhibition was extended due to its popularity.Footnote102 After Belgrade, the exhibition went to Cologne, Baden-Baden, Geneva, Brussels, Vienna, and Milan. It included an impressive collection of Pop art works in a variety of mediums – one of the highlights was Andy Warhol’s brightly coloured monumental diptych of Marilyn Monroe (Marilyn x 9). The exhibited artworks revealed even more of US American society and the “American way of life” than the previous Pop art exhibition, prompting Yugoslav artists to make highly critical comments on US capitalist consumer culture and its aggressive foreign policy.

The exhibition included seventeen US artists: George Segal, John N. Battenberg, Robert Nelson, Richard Boyce, John Paul Jones, Joseph Raffael, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann, James Gill, Paul Harris, Lester Johnson, Richard Diebenkorn, Frank Gallo, Robert Cremean, Robert Hausen, and Edward Higgins. They exhibited a total of forty-eight paintings and sculptures, which signified a return to the figure in US art. The exhibition’s catalogue included several essays by US critics. Of particular interest is the essay by the art historian Edward F. Fry, which displayed a nationalist and narcissistic belief in the artistic superiority of the US, with New York as its centre:

Continental Europe has made a negligible contribution to contemporary painting and sculpture since World War II. The primary centre of innovatory ideas has been New York for the past twenty-five years.Footnote103

As argued by Fry, the exhibition was meant to show to Europe that the US was at the forefront of artistic trends. Most importantly, the US curators argued that the exhibited artworks were a testament to a new intellectual climate in the US, in which artists engaged with existentialist thought and philosophy. The argument sought to counter the Eurocentric view that US Pop art was shallow and therefore inferior to European Figuration, which had already engaged with existentialist philosophy.Footnote104

But how successful were the artworks on display in The New Vein: The Figure in communicating these ideas to European audiences? Despite the US curators’ great hopes for the exhibition’s popularity in Yugoslavia, the art critic Stevan Stanić, writing for the party paper Borba, claimed that the Yugoslav curiosity for Pop art and New Figuration had already waned, since the public had already been exposed to “Pop” art in the work of several Yugoslav artists, including Ivanjicki and Kalajić.Footnote105 Stanić seized the opportunity to express his concerns over the “quick, much too quick relationship that had developed between our [Yugoslav] art and American art.”Footnote106 The art critic had no words of praise for these Yugoslav artists influenced by US art, instead he contemptuously called their efforts an “ersatz” Pop art: “a limp, deflated surrogate.”Footnote107 In an attempt to further distance the US Pop artists from his readers, Stanić presented them as coming from an “alien” metropolis: “after all, these artists live in loud and exciting skyscrapers, in feverish flashy urban environments and there are many reasons for their art in the American environment.”Footnote108

The distinguished art critic and professor Lazar Trifunović, writing for the widely read Serbian art magazine Umetnost (Art), was equally critical. However, his review was not as ideologically driven as Stanić’s; rather, Trifunović compared the exhibition to New Images of Man (1959, Museum of Modern Art, New York), an earlier (unsuccessful) exhibition of figurative art curated by Peter Selz. He therefore questioned the revival of the human figure and its meanings in 1969, noting that US curators “were, understandably, motivated by their cultural-political propaganda in Europe.”Footnote109 Trifunović doubted that the new tendencies of US art in the 1960s meaningfully changed the position of the figure and its aesthetic and philosophical connotations. Moreover, Trifunović made clear that he was no longer convinced that the US represented the ideals of freedom and individuality. Perhaps referencing Rauschenberg’s earlier success at the Venice Biennale in 1964, which had been interpreted by many as the “scandalous” outcome of US cultural imperialism, Trifunović’s review railed against the art system:

As never before, the period following the Second World War was characterized by confusion, bought awards and bribed art critics, made-to-order movements and ideas, brutal gallery politics and tactics, state and political propaganda, an atmosphere that jeopardizes the artists’ freedom and the ethics of art.Footnote110

Trifunović was equally cynical in his consideration of Pop art. He coined the term “active [practice of] indifference” to explain the relationship between Pop art, which, “does not judge, criticize, or morally teach,” and the surrounding world. Instead, Trifunović concluded that Pop art was the Socialist Realism of America, since in its indifferent identification with the means of mass culture, Pop art “essentially glorifies the lacquered arts of healthy white teeth, firm breasts, nylon tights, delicious soups, fake smiles and justice that prevails.”Footnote111 In the last part of his review, Trifunović “talked back” to the cultural chauvinism that marks Edward F. Fry’s catalogue essay, mentioned above. Trifunović asserted that it was “full of incorrect claims and nonsense” which only served to glorify one way of thinking, based on US nationalism. A parallel can be drawn here between Trifunović’s response and that of the British painter and art critic Patrick Heron, who in 1966 had felt compelled to defend European and British art in light of the cultural chauvinism of the US art critics Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried, asking “is the rest of the world supposed to shrug this sort of nonsense off with a smile?”Footnote112 Fry’s statement, Trifunović concluded, “is symptomatic of the ignorance that can occur with large nations and powerful states.”Footnote113

Instead, Trifunović pointed to the international spirit and universal character of modern art, which cannot be bound by national borders. Unlike the Eurocentric positions by the Yugoslav critics, discussed earlier, Trifunović did not attempt to dismiss US art in favour of European art. Instead, he believed that national borders should no longer play any role thanks to the increased opportunities of exchange.Footnote114 According to Trifunović, The New Vein: The Figure lacked inner conceptual unity and elicited contempt amongst the Yugoslavs and the imputation of “cultural propaganda” and US imperialism.

To conclude, the way the Yugoslav art world (curators, writers, artists) negotiated the arrival of US art in the 1960s was bound up with national identity, ideological issues, artistic and, to a lesser degree, gender issues. If, on the one hand, the assimilation of Pop art paralleled Yugoslavia’s rapprochement to the US, Yugoslav critics were not uncritical of it. A clearly Eurocentric perspective underpinned their assessments of Pop art, and they preferred to compare Yugoslav artists working in Pop idioms with European New Figuration rather than Pop. From a historiographical perspective, the Yugoslav assimilation of Pop art offer new case studies, which clearly deserve to be integrated into the history of the European reception of post-war US art. Effectively, Pop art’s reception in Yugoslavia reveals the polarities and tensions between those who welcomed and adopted the cultural, linguistic, behavioural, and political attitudes of Western Europe and the US; and those who were highly critical of foreign capitalist influences, starkly resisting and challenging the import of new systems, cultures and identities that they felt were being imposed on them. Moreover, Yugoslav art of this period should not simply be understood as derivative of US Pop art, but as an outcome of the Yugoslav artists re-contextualisation of the pictorial language of Pop art into their own practice in the pursuit of their own agendas, not dissimilar to other Western European artists, such as Vostell, Kleiva, or Equipo Crónica.

Notes

1 Anon. “Pop-Art, Umetnost ili Prevara [Pop-Art, Art or Scam],” Ilustrovana Politika, June 16, 1964, 28.

2 David Hopkins, After Modern Art: 1945-2000 (Oxford: University Press, 2000), 2.

3 Lawrence Venuti, Translation Changes Everything: Theory and Practice (London: Routledge, 2013), 13.

4 George Steiner, “The Hermeneutic Motion,” in Lawrence Venuti (ed.), The Translation Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 2000), 188.

5 Peter France, “Translation: The Serva Padrona,” Art in Translation, 2:2, (2010): pp. 119-129. DOI: 10.2752/175613110X12706508989334

6 Branislav Dimitrijević, “Pop Art and the Socialist ‘Thing’: Dušan Otašević in the 1960s,” in Tate Papers, no.24, Autumn 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/24/pop-art-and-the-socialist-thing-dusan-otasevic-in-the-1960s

7 Tvrtko Jakovina, “Povijesni uspijeh šizofrene države: modernizacija u Jugoslaviji 1945-1974 [The Historical Success of the Schizophrenic State: Modernisation in Yugoslavia 1945-1974],” in Ljiljana Kolesnik (ed), Socijalizam i Modernost. Umjetnost, kultura, politika 1950-1974 [Socialism and Modernity. Arts, Culture, Politics 1950-1974] (Zagreb: Muzej suvremene umjetnosti, 2012), 37; Ljiljana Kolešnik, “Delays, overlaps, irruptions: Croatian art of the 1950s and 1960s,” in Different Modernisms, Different Avant-gardes: Problems in Central and Eastern European Art After World War II (Tallinn: Eesti Kunstimuseum, 2009), 302.

8 Radina Vučetić, Koka-kola socijalizam [Coca-Cola Socialism] (Belgrade: Glasnik, 2015), 416.

9 David Crowley, “Pop Effects in Eastern Europe Under Communist Rule,” in J. Morgan and F. Frigeri (eds.) The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop (London: Tate Publishing, 2015), 33.

10 Ivanjicki’s trip was planned to be six months long. She extended her stay for another six months and travelled across the US with two Polish artists. Ivanjicki met President John F. Kennedy at a reception of Ford scholarship holders in Washington D.C. Ivanjicki also attended the opening of the famous "Space Needle" in Seattle on April 21, 1962, built for the 1962 Century 21 Exposition (also known as the Seattle World's Fair) whose theme was “The Age of Space”. Interview with Suzana Spasić, the Director of the Olga Olja Ivanjicki Foundation, February 1, 2021.

11 Pavle Vasić, “Izložba Olje Ivanjicki [Exhibition of Olja Ivanjicki],” Politika, October 8, 1964, 11.

12 Sue Hubbard, Olja Ivanjicki: Painting the Future (London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2009), 54.

13 Ibid., 54.

14 Ibid., 54.

15 Ibid.,15.

16 Cited in France, “Translation: The Serva Padrona,” 124.

17 D. Krajčinović, “Sudbina izložbe - rešena u autobusu [The Exhibition’s Destiny - Solved on the Bus],” Večernje Novosti, 29 September, 1964, 7. Translated by me. Original text reads: “Imam nameru da doputujem POP Molim da me sačekate u Grafičkom kolektivu POP Na dan 1. oktobra 1964. u 19 časova STOP Olja Ivanjicki - cveće nije obavezno.”

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 D. Gajer, “Faraon nije bio instalater: slikarka Olja Ivanjicki postigla je cilj [The Pharaoh Was Not a Plumber: Painter Olja Ivanjicki Achieves Her Goal],” Politika Ekspres, 7 October 1964, 8.

21 Hubbard, Olja Ivanjicki: Painting the Future, 281.

22 Olga Bosnić, “Večernji razgovor o pop artu: Olja Ivanjicki pred sudom publike [Evening Discussion of Pop Art: Olja Ivanjicki Before the Public],” Politika, October 7, 1964, 11.

23 Gajer, “The Pharaoh Was Not a Plumber: Painter Olja Ivanjicki Achieves Her Goal,” 8.

24 Gablik and Russell, Pop Art Redefined (New York: Frederick A Praeger Publishers, 1969), 10.

26 Dragoslav Djordjević, “Peta medjunarodna izložba grafike [The Fifth International Graphic Art Biennale],” Borba, September 10, 1963, 7.

27 Dragoslav Djordjević, “Uz jednu izložbu Pop Arta [Alongside a Pop Art Exhibition],” Borba, 8 October 1964.

28 Ibid.

29 France, “Translation: The Serva Padrona,” 121.

30 Božidar Timotijević, “Pop Art ili Vulgarizacija Umetnosti [Pop Art or the Vulgarisation of Art],” Borba, 18 October, 1964, 9.

31 Hopkins, After Modern Art, 98.

32 Timotijević, “Pop Art or the Vulgarisation of Art,” 9.

33 Ibid., 9.

34 An interview with Irina Subotić, by Stefana Djokic, 17 May 2019, Belgrade, Serbia.

35 Anon. “Svako ima pravo da se zabavlja: Poznati Beogradjani o Pop Art izložbe Olje Ivanjicki [Everyone Has the Right to Entertain Themselves: Famous Belgrade Citizens on Olja Ivanjicki’s Pop Art Exhibition],” Politika Ekspres, 5 October 1964, 8.

36 David Binder, “Pop Artist in Belgrade Finds Buyers (Sob) Scarce,” The New York Times, October 24, 1965, 85.

37 Otašević was about to graduate from Belgrade’s Academy of Fine Arts, Ivanjicki was the oldest of the group and once again the only female member, Kalajić had at the time lived and worked in Rome where he had forged strong links with the Italian New Figuration, while Radomir Reljić and Boleta Miloradović were both young and relatively unknown artists at the time.

38 Lidija Merenik, Ideološki Modeli: Srpsko Slikarstvo 1945-1968 [Ideological Models: Serbian Painting 1945-1968] (Belgrade: Margo-art, 2001), 118.

39 Vučetić, Coca-Cola Socialism, 253.

40 Merenik, Ideological Models: Serbian Painting 1945-1968, 122.

41 Piotr Piotrowski, In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989 (London: Reaktion Books, 2009), 303.

42 Jessica Morgan and Flavia Frigeri (eds.), The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop (London: Tate Publishing, 2015), 157.

43 Ibid., 157.

44 Branislav Dimitrijević, “Pop Art and the Socialist ‘Thing’: Dušan Otašević in the 1960s.” inTate Papers no.24,https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/24/pop-art-and-the-socialist-thing-dusan-otasevic-in-the-1960s, accessed May 2022.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 Branislav Dimitrijević, Dušan Otašević: Popmodernizam, Retrospektivna izložba 1965-2003 [Dušan Otašević: Popmodernism, A Retrospective Exibition 1965-2003] (Belgrade: Muzej savremene umetnosti, 2003), 110.

49 Ibid., 112.

50 Ibid., 112.

51 Morgan and Frigeri (eds.), The EY Exhibition, 138.

52 Ibid., 212. 212.

53 Ješa Denegri, “Nova Figuracija Beogradskog Kruga [New Figuration of the Belgrade Circle],” Umetnost, 1966, 66.

54 The EY Exhibition, 130.

55 I. Chilvers and J, Glaves-Smith (eds.). A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art (Oxford: University Press, 2015) https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199239665.001.0001/acref-9780199239665-e-1942

56 In turn, the French Les Nouveaux Réalistes were very popular in Slovakia during the 1960s because of the close relation of local artists to Pierre Restany. See Piotr Piotrowski, “Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s?,” Baltic Worlds, 3-44 (2015): 12. http://balticworlds.com/why-were-there-no-great-pop-art-curatorial-projects-in-eastern-europe-in-the-1960s/

58 See: Patrick Frank, Painting in a State of Exception: New Figuration in Argentina, 1960–1965 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2016).

59 See Katalin Timár, “Is Your Pop Our Pop? The History of Art as Self-Colonizing Tool,” ARTMargins Online (March 2022) https://artmargins.com/is-your-pop-our-pop-the-history-of-art-as-a-self-colonizing-tool/.

60 Piotrowski, “Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s?,” 10-16.

61 While the exhibition included a total of fifteen paintings by five artists, the slim exhibition catalogue contained no reproductions and as a result only a few of the exhibited artworks can be traced today. Therefore, the discussion in this paper is lamentably incomplete and will largely focus on only three of the five exhibited artists–Ivanjicki, Kalajić and Otašević—as the exhibited works of Bole Miloradović and Radomir Reljić are currently untraceable.

62 Djordje Kadijević, Nova Figuracija Beogradskog Kruga [New Figuration of the Belgrade Circle] (Belgrade: Galerija Kulturnog Centra, 1966), exhibition catalogue.

63 Piotr Piotrowski, “Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s?,” in Annika Öhrner (ed.), Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop: Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies (Huddinge: Sodertorn University, 2017), 26.

64 Kadijević, New Figuration of the Belgrade Circle.

65 Ibid.

66 Lucy Lippard, “New York Pop,” in Pop Art (London: Thames and Hudson Limited, 1970), 69.

67 Quoted from Marco Livingstone, Pop Art: A Continuing History (London: Thames Hudson, 1990), 141.

68 Tilman Osterwold, Pop Art, (Köln: Taschen, 2003).

69 Lippard, Pop Art, 11.

70 Ibid.

71 Slobodan Ristić, “Dušan Otašević,” Umetnost, Belgrade, July-September 1972, 55.

72 Ibid.

73 Marija Pušić, “Nova Figuracija Beogradskog Kruga [New Figuration of the Belgrade Circle],” Oslobodjenje, Sarajevo, 20 February, 1966.

74 Dimitrijević, Dušan Otašević, 16.

75 Politika, 25 March, 1966.

76 Boris Keleman, Pop Art (Zagreb: Galerija Suvremene Umjetnosti, 1966). Exhibition Catalogue.

77 Full quote reads: “Pop Art is: Popular, Transient, Expendable, Low cost, Mass produced, Young, Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big business.” Richard Hamilton, 1957. http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/display/witty-sexy-gimmicky-pop-1957-67

78 Kozloff once likened his encounter with Lichtenstein’s art in 1969 to “glugging a quart of quinine water followed by a Listerine chaser.” Quoted in “Max Kozloff: A Phenomenological Solution to ‘Warholism’ and its Disenfranchisement of the Critic’s Interpretive and Evaluative Roles,” in Sylvia Harrison (ed.), Pop Art and the Origins of Post-Modernism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001), 150.

79 Kozloff wrote this in response to Lichtenstein’s debut 1962 solo exhibition of Pop paintings at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York. Quoted in Titia Hulst, “The Vicissitudes of Taste: The Market for Pop,” Journal for Art Market Studies, 2 (2017), 10.

80 Max Kozloff, “American Painting During the Cold War,” Artforum (May 1973): 43–54.

81 Jennifer Liese, “May 1973 (Max Kozloff in Artforum three decades ago),” Artforum International; New York Vol. 41, Iss. 9, (May 2003): 42.

82 The same artists and artworks were also on show in an exhibition entitled 11 Pop Artists: The New Image at the Galerie Friedrich + Dahlem in Munich in 1966.

84 Jelena Stojanović, “Hladnoratovsko Oko. Jednog proleća, jedna izložba u muzeju savremene umetnosti u Beogradu [The Cold War Eye. One Spring, One Exhibition in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade],” in Dejan Sretenović (ed.), Prilozi Muzeja Savremene Umetnosti [Contributions for The Museum of Contemporary Art] (Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade, 2016), 273.

85 Arhiv Jugoslavije [The Archive of Yugoslavia], 559, F-100-222, August 27, 1965. Translated by me. Original text reads: “Videti sa Protićem, pa da se dogovorimo u vezi odgovora. Naravno, nikakvog našeg angažovanja ne može biti.”

86 An interview with Irina Subotić, by Stefana Djokic, 17 May 2019, Belgrade, Serbia.

87 Irina Subotić, “Američki Pop Art [American Pop Art],” Umetnost, Belgrade, 1966.

88 Djordje Kadijević, “Talas sa Zapada [A Wave from the West],” NIN, 10 April, 1966.

89 Bogdan Tirnanić, “Na Margini Svakodnevnog [On the Margin of the Everyday],” Mladost, April 27, 1966.

90 Dragoslav Djordjević, “Još jednom o pop-artu [Once More on Pop Art],” Borba, 10 April, 1966.

91 Ibid.

92 Vučetić, Coca-Cola Socialism, 257.

93 This is known as the Sociological Turn, a term introduced by the translation scholars Claudia Angelelli and Sergey Tyulenev. Claudia Angelelli, “The Sociological Turn in Translation and Interpreting Studies,” Translation and Interpreting Studies 7 (2): 125-128; and Sergey Tyulenev, Translation and Society: An Introduction (London: Routledge, 2014).

94 Djordjević, “Once More on Pop Art.”

95 Eugen Feller, “Pop Art (Dabome!) i u Zagrebu [Pop Art (That’s Right!) in Zagreb],” Republika, 1966, 257.

96 Feller, “Pop Art (Dabome!) i u Zagrebu,” 257.

97 Tirnanić, “On the Margin of the Everyday.”

98 David Crowley, “The Future is Between Your Legs: Sex, Art and Censorship in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia,” in Monuments Should Not Be Trusted ed. Lina Džuverović (Nottingham: Nottingham Contemporary, 2016), 35.

99 Patrick Hyder Patterson, Bought & Sold: Living and Losing the Good Life in Socialist Yugoslavia (London: Cornell University Press, 2011), 69.

100 Ibid., 91.

101 Jasmina Čubrilo, “An Insight into the Reception of American Art in Yugoslavia 1965-1991,” in Hot Art, Cold War – Southern and Eastern European Writing on American Art 1945-1990 ed. Claudia Hopkins and Iain Boyd Whyte (London: Routledge, 2021), 236.

102 Vučetic, Coca-Cola Socialism, 244.

103 Edward F. Fry, “National Styles and International Avant-garde,” in The New Vein: The Figure 1963-1968 (Belgrade: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 1969), exhibition catalogue, 35.

104 Alexander Sesonske, “Art and Ideas: America, 1968,” in The New Vein: The Figure 1963-1968, 33.

105 Stanić, “Američka Nova Figuracija [American New Figuration],” Borba, 7 January, 1969.

106 Ibid.

107 Ibid.

108 Ibid.

109 Lazar Trifunović, “Savremena Američka Umetnosti [Contemporary American Art],” Umetnost (Belgrade, February–March 1969). Belgrade.

110 Ibid.

111 Ibid.

112 Patrick Heron, “The Ascendancy of London in the Sixties,” Studio International 272, no. 884 (December

1966): 281. Quoted in David Hopkins, “A ‘Special Relationship’: British and American Art 1945-1989,” in Claudia Hopkins and Iain Boyd Whyte (eds), Hot Art, Cold War – Western and Northern European Writing on American Art 1945–1990 (London: Routledge, 2021), 7.

113 Trifunović, “Savremena Američka Umetnosti.”

114 Ibid.