Abstract

During the Cold War Picasso’s Guernica was on loan at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Throughout this period, its interpretation was the subject of much debate. The museum was interested in situating the painting within its own narrative of twentieth-century art history, while, at the same time, the painting functioned as an icon in contemporary political struggles in the form of reproductions and pictorial versions. This article reviews some of these contradictory positions towards Picasso’s work during this intense “battle for the interpretation”.

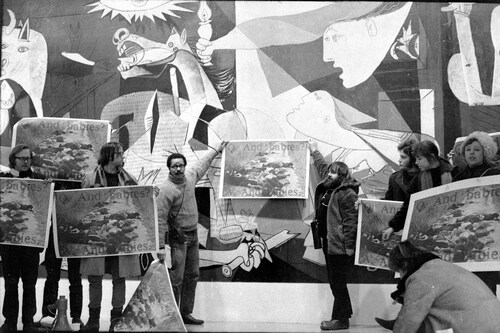

A photograph by Jan van Raay shows a group of protestors in the halls of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York on January 8, 1970. They are members of the Art Workers Coalition and Guerilla Art Action Group, two art collectives whose activities included pressurizing the city’s museums to reform their internal operations and improve the treatment of artists.Footnote1 The MoMA was one of their main targets, for reasons explained by members of the coalition themselves:

Its rank in the world, its Rockefeller-studded board of trustees with all attendant political and economic sins attached to such a group, its propagation of the star system and consequent dependence on galleries and collectors, its maintenance of a safe, blue-chip collection, and particularly, its lack of contact with the art community and recent art.Footnote2

The photograph shows the protestors in action, holding up copies of the And babies?- poster created for the event, during which they infiltrated the museum, read out a manifesto and laid wreaths in front of the painting. The activists had tried to get the museum involved in publishing the poster, but after much discussion, the institution decided to remain in the sidelines, arguing that it ought to confine its activities “to questions related to [its] immediate subject.”Footnote3 ()

Figure 1 Jan van Raay, Art Workers’ Coalition and the Guerilla Art Action Group protest in Front of Picasso’s “Guernica” at the Museum of Modern Art, with the AWC’s “And Babies?” poster, 1970. Photograph, Museum of Modern Art, New York © Jan van Raay/Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2022.

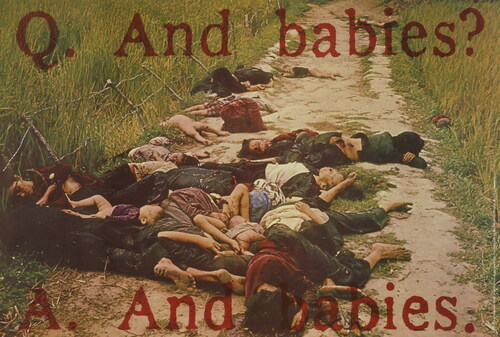

The image on the poster was taken by combat photographer Roland Haeberle and depicts the bodies of several dead women and children on a road. It documents the massacre that took place in the Vietnamese village of My Lai two years earlier, claiming the lives of more than three hundred civilians at the hands of the US military. Haeberle’s photograph reached a wide audience after it was published in Life magazine in 1969.Footnote4 A team of AWC members then incorporated the photograph into a huge poster with the dialogue from a press interview with a US war veteran emblazoned on it in large red letters: “Q: And Babies? A: And Babies.”Footnote5 ()

Figure 2 Art Workers' Coalition, Q. And babies? A. And babies., 1970. Offset lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Jon Hendricks, 2017.10 © 1970 Irving Petlin, Jon Hendricks, and Frazer Dougherty.

The message itself seems unequivocal, but the protesters’ reading of the painting is less clear. Pablo Picasso painted Guernica in 1937, during the Spanish Civil War. The painting had been commissioned by the Spanish Republican government and unveiled at the Spanish pavilion during the 1937 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (). The modest building representing Spain stood next to the imposing German pavilion and opposite the Soviet pavilion, a standoff that eloquently demonstrated the politically loaded climate surrounding the international exhibition that year. Picasso’s painting has direct connotations in this context: the Spanish pavilion was located right next to the pavilion designed by Hitler’s architect Albert Speer of Nazi Germany, whose air force had bombed Guernica ignoring the official declarations that had previously been made to assure the non-intervention of foreign powers in Spain’s Civil War. The iconography of Picasso’s painting made pointed references to the events, although the organizers of the Spanish pavilion had wanted to suppress such contents. The exhibition’s rules explicitly stated that “anything that might be viewed as a provocation by any government represented in Paris with a pavilion” was to be avoided, and that the focus should be instead on the “admirable efforts of the Spanish people to defend their independence and the cause of world peace.” It was hoped that this would rule out potential allusions to a “foreign government” at the Spanish pavilion.Footnote6 Yet, without the need to depict any flags or uniforms, Picasso’s painting conveyed a very clear message about the war Spain was experiencing. Indeed, the message was so direct that the National Socialist press immediately reacted and attempted to present the painting as a set of fragmentary, incomprehensible forms and figures.Footnote7

Figure 3 View of the Spanish Pavilion, International Exhibition of Arts and Techniques in Modern Life, Paris, 1937. Photograph © José Lino Vaamonde Valencia. Instituto Del Patrimonio Histórico Español, Madrid. Donación De J. Vaamonde Horcada (2001)/Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2022.

After the exhibition finished in Paris, Picasso’s mural toured various northern European capitals (Oslo, Copenhagen, and Stockholm), and in 1939 it was taken on a tour of various cities in the United States of America as part of the Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign organized by the American Artists Congress. Guernica’s final destination was New York, where it was scheduled to be displayed at the exhibition Picasso: Forty Years of His Art at the MoMA.Footnote8 () The artist wished to donate the painting to the Spanish state, but the escalation of the Spanish Civil War and the establishment of General Franco’s dictatorial regime in 1939 meant that this was not an immediate prospect. Guernica was to remain at the MoMA as an “extended loan from the artist” until 1981, when it was moved to the Museo del Prado in Madrid after Franco’s death (1975) and the restoration of democracy in Spain.Footnote9

A Canvas and a Political Icon

The painting continued to hold a strong political significance for certain North American activists in the 1960s, even though years had passed and the context was quite different. Campaigning to defend the innocent victims of armed conflict, the Angry Artists collective joined forces to collect signatures for a petition addressed to Picasso: they wanted him to have Guernica removed from the MoMA in protest against the US air strikes in Vietnam and the political actions of certain members of the museum’s patronage.Footnote10 This caused a whole raft of difficulties for Alfred Barr Jr, who was the first Director of the MoMA and served as the Director of Collections from 1947.Footnote11 Barr corresponded intensely with Picasso on the subject over the years, and, fortunately for him, the artist sided with the museum. “It does most good in America,” he said.Footnote12

This was not the first problem posed by the reception of Picasso’s work in the US. The painter was already an undisputed legend of twentieth-century culture, and he had openly declared his affiliation with the Communist Party, which he joined in 1944. His reasons came to light in a famous interview published in L’Humanité, which swiftly reached US audiences through the English translation in New Masses.Footnote13 Even though Picasso was not a US citizen, the director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, subsequently took it upon himself to gather all the information he could find about the artist “in view of the possibility that he may attempt to come to the United States.”Footnote14 There were even certain alternative images produced to political ends: after Picasso’s dove was used as the emblem for the 1949 World Peace Council in Paris, the anti-communist movement Paix et liberté—secretly supported by the CIA—distributed an alternative poster on various media with the title La colombe qui fait boum!, an ironic take on the reality of the pax sovietica.Footnote15

This climate became even more radicalized during the cultural purge promoted by Joseph McCarthy, who tried to label any leftist stance as “un-American.” George A. Dondero, the Republican representative from Michigan, best expressed this mindset in relation to the art world: “Modern art is Communistic because it is distorted and ugly, because it does not glorify our beautiful country, our cheerful and smiling people, and our material progress.”Footnote16 Of course, Picasso—whom Dondero called “the hero of all the crackpots in so-called modern art”Footnote17—was a primary target of these criticisms. Guernica’s tour of the US was frequently criticized in similar terms, with one newspaper headline referring to the exhibition of the painting in Chicago in 1939 as “Bolshevist Art Controlled by the Hand of Moscow.”Footnote18

Barr often found himself forced to make public statements refuting such claims, given that the MoMA collection was full of works by these “communists.”Footnote19 In an article published in 1953, Barr argued that a “radical style” does not necessarily imply “radical politics.” He also highlighted the potential consequences of this style in the US context in those years, claiming that the enemies of freedom of expression were not only communists but also “the fanatical pressure groups working under the banner of anti-communism.”Footnote20

Indeed, Barr had maintained an intense correspondence with direct contacts of Picasso during the 1940s, trying to arrive at a precise interpretation of the symbolism of each figure in the painting. This subject was even put to public debate in the Symposium on Guernica at the MoMA in 1947.Footnote21 The discussions were inconclusive, however, and naturally gave way to the neutral, apolitical narrative that was applied to Picasso’s Guernica from then on. The label, which was displayed next to the painting from the mid-1950s onwards, primarily offered basic information about the German bombing of the Basque city on April 27, 1937, and the unveiling of Picasso’s painting at the Paris International Exhibition that same summer. The final paragraph appeared to counteract the painting’s links with these historical facts: “There have been many and often contradictory interpretations of the Guernica. Picasso himself has denied it any political significance stating simply that the mural expresses his abhorrence of war and brutality.”Footnote22

This “universalist” interpretation, which avoids any specific historic allusions, could be considered part of the “de-Marxization of the American intelligentsia,” a process which, according to Serge Guilbaut,Footnote23 began around 1936 and was in full swing by the 1950s. By entering an institution like the MoMA in 1939, Guernica was joining a narrative about the history of art—one in which each work belongs to a place determined by certain influences and a context, allowing for a discussion of ideas such as evolution or style.Footnote24 Displayed on the gallery walls, the painting began to relate to Picasso’s other works, in particular Les demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), which Barr acquired for the museum in 1939. These two paintings would demonstrate the full cycle of the avant-garde movement. With Les demoiselles, we see Picasso beginning to break away from the traditional system of artistic representation, paving the way for Cubism; then finally the circle closes with Guernica, like the swan song of the European avant-garde and one last link in the artist’s work until that date. As Clement Greenberg wrote in 1957: “Guernica was obviously the last major turning point in Picasso’s development.”Footnote25

Exhibited in the MoMA, Guernica became a key reference for many New Yorkers and visitors to the city. The mural was a jolt to the senses for young painters including Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky, William Baziotes, and Willem de Kooning (whose native Rotterdam had been destroyed by air strikes during World War II).Footnote26 Many of these artists had a common interest in Spanish culture, which intensified with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, a conflict in which many figures of US culture became directly or indirectly involved.Footnote27 in the words of Robert Motherwell: “the Spanish Civil War was even more to my generation than Vietnam was to be thirty years later to its generation, and should never be forgot, even though la guerre est finie.”Footnote28 However, the “extreme modernist individualism” with which Motherwell identified himself would lead from political activism to an interpretation of Picasso’s work in formalist terms. “Guernica hangs in an uneasy equilibrium, between now disappearing social values, i.e., moral indignation at the character of modern life,” on the one hand, and purely artistic values on the other: “the Eternal and the Formal, the aesthetics of the papier collé.”Footnote29

Paintings about a Painting

The inclusion of Guernica in the history of art—with its impact on the interpretation of Picasso’s career and that of the artists from the New York school—is just one part of the process. Entrusted with preserving the original canvas, the MoMA also began to promote the dissemination of the artwork in the form of reproductions which could be purchased as postcards and posters or used as illustrations in a book. As a reproducible image, Guernica would be circulated widely, often for purposes that bore no relation to the history of art as understood by Barr. Reproduced in various forms, including posters, Guernica became a political icon with a life of its own outside the institutional setting of the museum. Hence, as Rocío Robles has noted, the painting is “doubly effective” when displayed in the MoMA: “As a work of art it becomes a protest sign, and as a poster that reproduces a work of art, it is sold in the museum.”Footnote30

As well as appearing on posters and banners in the context of numerous political demonstrations in the late 1960s, Guernica also became a motif for other artists. The painting was reimagined and inspired variations on the same theme as far away as South Africa, where Dumile Feni painted his African Guernica in 1967.Footnote31 Its influence could also be felt in Europe, for example in Antonio Recalcanti’s España. The piece, unveiled at the 1964 Salon de la Jeune Peinture, sought to portray Franco’s Spain through fragments of landscapes, people and a very significant allusion to Guernica.Footnote32

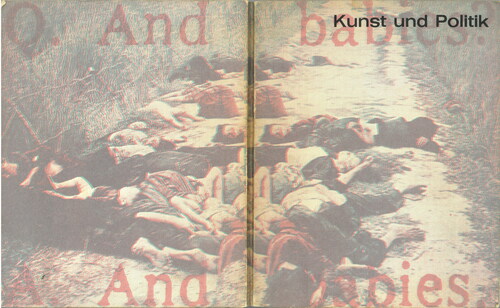

An interesting case in point here is the 1970 exhibition Kunst und Politik which was curated by Georg Bussmann and held at the Badischer Kunstverein in Karlsruhe. The cover of the exhibition catalogue features the same poster about the My Lai massacre that the AWC protestors were pictured holding up at the MoMA in January 1970. () Inside the catalogue is a written and visual reflection on Guernica, directly linking the artwork with the issues addressed by the New York artists during the Vietnam War. The introductory text reflects on the question of the social or political status of works of art, an issue that was high on the agenda in the late 1960s. Of course, Guernica is cited as an example: “Does a work of art as great, as universally human as Picasso’s Guernica have a political impact?”Footnote33 This issue brings us to other questions relating to democracy and access to education: Truth be told, would other works, such as Picasso’s etchings The Dream and Lie of Franco not be more politically impactful? Is there really a politically engaged audience for Guernica? The contemporary art world consists of a very small group of people—doesn’t that make it politically irrelevant?

Many of these questions had already been raised in the MoMA’s debates about the interpretation of Guernica. Meanwhile, Kunst und Politik contained more than just theoretical reasoning; it also included visual propositions relating directly to Picasso’s work. Paolo Baratella and Giangiacomo Spadari presented their Confrontation with the Historical Dynamic of Reality from the same year, 1970. The piece referenced classic and contemporary artists whose work touches on the subject of victims of war and repression, and revolutionary movements in contemporary history: for instance, Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat; The Third of May 1808 and other paintings by Francisco de Goya; Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People; one of George Grosz’s caricatures; and various fragments of Guernica.Footnote34 By bringing together wars from different eras in this series of fragments, the distance between them disappears so that they can easily be applied to the current situation.

Guernica 69

Kunst und Politik includes another interesting reinterpretation of Guernica by Equipo Crónica, a collective that contributed various works from the Guernica ‘69 series to the exhibition. The Valencian-born artists Manolo Valdés and Rafael Solbes began working as a collective in 1964 after founding the group with Juan Antonio Toledo, who soon left the group. Their paintings are based on historical artworks, both classic and contemporary, and they use these fragments as a springboard for creating new paintings full of irony and complex political significance. The artists explained that their objective was to achieve “objectification and realism” in the themes portrayed in their work. To achieve this, they eschewed personal interests and worked in a team, which they saw as a means of overcoming “the mythology of individualism” and “subjective expression as the intention of artistic activities.”Footnote35 Working as a collective therefore served not only a functional purpose; it also served as an ideological alternative to the “extreme individualism” of which the abstract expressionists spoke, and it was coherent with the idea of artwork based on the recontextualization of existing images.Footnote36 Equipo Crónica’s contribution to the exhibition in Karlsruhe included examples of artworks from the series entitled La recuperación (The Recovery), which incorporated images borrowed from the history of art, as well as three pieces from the Guernica 69 series, which had been exhibited in its entirety at the Grises gallery in Bilbao, in 1969.Footnote37 This series differs from others in that the paintings use a specific painting as their starting point, creating emblematic works of contemporary culture that are “loaded with significance.”Footnote38

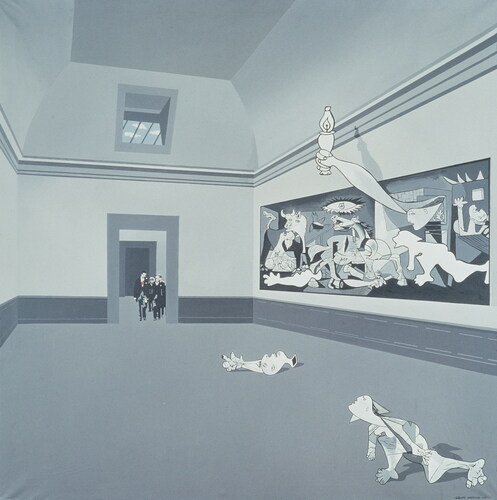

The most ambitious, most striking work in the series is La visita (The Visit), which shows Picasso’s mural on the right-hand wall of a gallery. () The room is a vast hall with high ceilings, cornice, and an extended arch that transitions into a flat roof. An elegantly dressed women enters the gallery through a doorway in the background. But her presence seems unwelcome to the figures on the wall, which are trying to flee from the painting in terror: the chest and arm from the lower section of the painting are lying on the floor, abandoned; the ungainly figure from the lower right section of Guernica has emerged and is prowling around the gallery, and the arm holding the torch has pulled free from the canvas. The architecture is particularly noteworthy: the room in which the painting is displayed, with its high, arched ceilings and cornice, has little in common with the perfectly rationalist “white cube” that the MoMA was at the time. The scene is more reminiscent of the galleries in the Museo del Prado, where the painting was eventually destined to be displayed at some point—although it does not copy any of the rooms in the Madrid museum to the letter.

Figure 6 Equipo Crónica, Guernica 69. La visita, 1969. Acrylic on canvas, 120 x 120 cm, Colección Lucio Muñoz, Madrid © Index Fototeca/Bridgeman Images, DACS 2022.

This rather strange, unsettling image can be understood as part of Equipo Crónica’s unwavering mission to comment on the current state of affairs by way of referencing historical artworks. Around this time, news spread to the media that the Francoist government was making advances to Picasso and attempting to gain his support for the new Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (Museum of Contemporary Art) that was being planned for Madrid.Footnote39 Over the following decade, these relatively spontaneous advances gave way to an official strategy by the Spanish regime to return Guernica to Spain, where it was ultimately intended to reside. The government’s argument was straightforward: if the MoMA had adopted a deliberately ambiguous interpretation of the mural, concluding that it lacked “any political significance” other than a general loathing of “war and brutality,” then there was nothing to stand in the way of the painting being repatriated to Franco’s Spain. “To quote the author himself, this famous work of contemporary art has no political significance,” Spanish Consul General in New York City, Ángel Sanz-Briz, explained in a letter in 1964. He concluded that this hotly debated work of art posed no element of “political hostility” for the Spanish regime, which he stressed was not the subject addressed by the mural.Footnote40 This claim was followed by a series of attempts to initiate the repatriation process for the painting, and despite plans to put this plan into action discreetly, the press caught wind of the news very quickly.Footnote41 Clearly there had been a general shift in the interpretation of Picasso’s work in Spain, similar to the neutralizing process that was underway in the US. In the 1940s, the rejection of Picasso’s work by Spanish critics was radical.Footnote42 Two decades later, however, the Spanish context had changed enough so that, in a completely different process, the official interpretations were moving closer to the depoliticized readings put forward by the American formalist critics.Footnote43 Jutta Held has described the conversion of an image into a political symbol as a never ending process, since it will always be contested: “The opposing side will try to incorporate it within its own political strategy, to appropriate or at least to neutralize it”.Footnote44 This is exactly what happened to Guernica in Franco’s Spain.

“In the heart of Spain, the heart of Madrid, Guernica will be a beacon for the whole world to see,”Footnote45 one of the official curators of the regime, Luis González Robles, said around this time. Eventually, he took the subject up directly with Picasso, who quickly turned to his lawyer Roland Dumas to make his views on the matter clear. “I do not want the Guernica to enter Spain while Franco is still alive. It is my masterpiece. I hold it dearer than anything else. Nothing else matters to me,”Footnote46 he wrote. His point was made, and the press aired his response, dashing the hopes of the Francoist government.

Equipo Crónica’s painting alludes to these events.Footnote47 As such, it has been described as a kind “fantasy” that tells a fictitious narrative about a possible scenario that was considered in the late 1960s.Footnote48 Its political and artistic implications are very clear. Two other paintings from the Guernica 69 series are included in the Kunst und Politik exhibition catalogue. The first one is El embalaje (Packaging), which depicts a parcel with the top right section torn open, revealing the light bulb and horse from Picasso’s Guernica. () The painting plays with the composition of the mural, providing a glimpse of its contents through this solitary fragment. It underscores the idea of a journey and turns the horse’s dramatic movement into a protest against Picasso’s artwork being adopted and neutralized by Franco’s government. The second painting, Después de la batalla (After the Battle), depicts characters from Picasso’s painting strewn across a Spanish landscape, as if alluding to its ruin in the wake of the Spanish Civil War.

Figure 7 Equipo Crónica, Guernica 69. El embalaje, 1969. Acrylic on canvas, 120.5 x 119.5 cm, Fundación La Caixa, Barcelona © DACS 2022.

Guernica 69 is structured around a series of basic elements: it is a collaborative project in which a fictitious narrative unfolds in the form of a series of artworks that relate to the political climate of the time in a very immediate way. Explaining their work and how the collective came about, the members of Equipo Crónica cite the emergence of Pop art and the end of the “short-lived glory of the post-informal alternative, known at the time as Nueva Figuracion.”Footnote49 In this context, the collective distanced themselves from the “triumph of Pop art,” a movement they criticized for its “colonial character,” which they perceived as “an invasion” in those times and obscuring what they considered as “more serious” experiences that people were having in Europe. Instead of following the work of American artists, whose works were interpreted in formalist terms in Europe,Footnote50 Equipo Crónica aimed at a collective and social work, with a complex meaning. They they achieved this with various techniques, such as the creation of fictitious, ironic, and complex narratives, which made it impossible for the work to become merely decorative.Footnote51 Their fundamental reference in this sense was the work of Eduardo Arroyo, who was exiled in Paris at the time. In his work with Gilles Aillaud and Antonio Recalcanti—for example, Une passion dans le désert (1964) or Vivre et laisser mourir ou la fin tragique de Marcel Duchamp (1965) Arroyo offers a critical, narrative, sequential model of art, which is deliberately set apart from the US model.Footnote52 Based on these models, Guernica 69 can be seen as an attempt to re-politicise the interpretation of Picasso’s painting in the context of the Cold War conflicts.

Guernica Goes Pop

The artists play with collective authorship in these works of art, developing various pieces assembled in series to allow for a more complex treatment of subjects than individual paintings. In the words of the artists themselves: “For us, working in series is the perfect way to combine the specific with the dynamic, dialectical treatment of the general.”Footnote53 Specifically, Guernica 69 presented itself as “an opportunity to reflect on the process of transformation of an image and its significance.”Footnote54

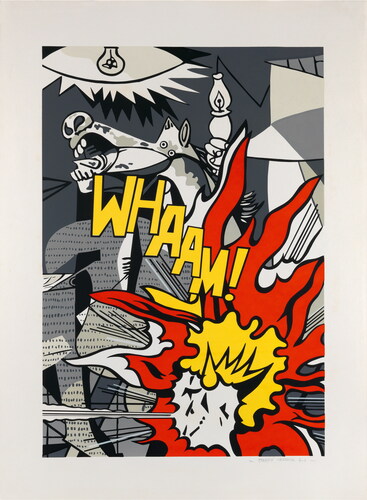

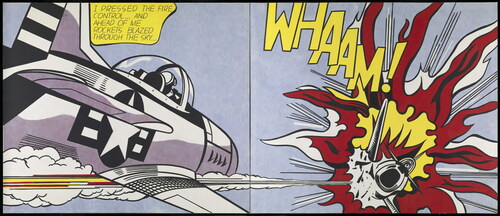

Building upon historical works of classical twentieth-century art to generate fictitious narratives, Equipo Crónica occupied a ground that could be related to European Narrative Figuration, a movement with which they were directly associated.Footnote55 However, other Equipo Crónica works inspired by the Guernica 69 series allow different links to be made. The 1971 lithograph Guernica, for example, shows a fragment of Picasso’s painting—the horse, the large lightbulb and part of the hand holding the lamp—beneath an explosion of red and yellow and the word “Whaaam!” () It is not difficult to make out the reference to one of the iconic works of US Pop art here: the Whaam! diptych painted by Roy Lichtenstein in 1962. Lichtenstein’s painting is a large-scale, decontextualized version of a panel from All American Men of War, a comic set in World War II, depicting an enemy aircraft being blown up by a North American fighter jet. ()

Figure 8 Equipo Crónica, Guernica, 1971. Serigraph, 75.3 x 55.4 cm, Institut Valencià d'Art Modern, Valencia © DACS 2022.

Figure 9 Roy Lichtenstein, Whaam!, 1963. Acrylic paint and oil paint on canvas, 30 x 12.9 cm, Tate, London © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein/DACS 2022.

In 1960s Spain, Lichtenstein was schematically defined as creator of “gigantic comic strips,”Footnote56 someone who made the kind of art found in “children’s magazines.”Footnote57 From the early 1960s, however, he also painted Pop art versions of avant-garde works, including works inspired by Picasso’s portraits and still life paintings, such as Femme au chapeau (1962) and Woman with a Flowered Hat (1963).Footnote58 This was quite a provocative move. In those years, Picasso was synonymous with the avant-garde art and therefore served as an alternative to commercial and mass art. “The alternative to Picasso is not Michelangelo, but kitsch,”Footnote59 Clement Greenberg wrote in 1939. Even Greenberg recognized that the exhibitions of the Malaga-born artist’s work drew large crowds, as far as he was concerned, this was a misleading phenomenon: “We must not be deceived by superficial phenomena and local successes.”Footnote60

Picasso’s popularity is precisely what attracted Lichtenstein, who was one of the many regular visitors to Picasso’s exhibitions. A visit to the MoMA in 1939 made a lasting mark on the artist at the beginning of his career; he was particularly taken with Guernica on this visit and would see the painting again two years later at an exhibition in Columbus, Ohio.Footnote61 These experiences, combined with the increasing presence of Picasso’s artwork in everyday life through reproductions in books, posters and postcards, prompted Lichtenstein to start thinking about using this reproducible work as an artistic motif. “A Picasso has become a kind of popular object—one has the feeling there should be a reproduction of a Picasso in every home,”Footnote62 the artist said in 1967.

In his own words, Lichtenstein’s intention was to create an “oversimplified” version of Picasso’s work,Footnote63 to reduce the “original” avant-garde images to reproducible “clichés”.Footnote64 However, Lichtenstein never produced his own take on Guernica, a painting that definitely lent itself to reproductions both in the pedagogical field and in political activism. Equipo Crónica’s Guernica might be the version of Picasso’s work that Lichtenstein avoided. Its starting point is the most politicized artwork of Picasso’s entire oeuvre, which Equipo Crónica brought into the contemporary context of the 1960s.Footnote65 Like Lichtenstein, they regard Guernica as an artwork with “a certain value as a symbolic cliché.” But they add new layers of meaning, using various techniques—“decontextualization, anachronism, illogical collages, etc.”—to generate an effect of “Brechtian alienation”:Footnote66 the image is not “transparent” and clear, but rather complex and satirical, harboring various layers of meaning. With purely visual media, the different versions of Guernica provide food for thought: Picasso’s work is not just a work of art from the past that belongs to art history; it is also a Pop icon that can be filled with color with the addition of a comic strip explosion, like in Lichtenstein’s vision. In the words of Jessica Morgan, “Equipo Crónica’s work politicizes Picasso through its ambiguous connection to American pop culture’s iteration of violence.”Footnote67 A number of questions beg to be asked here: does the use of Lichtenstein’s imagery imply that this is an American explosion, linking Guernica to the Vietnam War as the members of AWC intended? Or is this a historical reference to a comic from World War II? Or is it a nod to the outbreak of war in 1936 that inspired Picasso’s painting? All these anachronisms are part of the painting’s message, which is ambiguous and open but highly critical, because it implies that the painting remains politically active, in direct opposition to the views held up (for different reasons) by the American formalists and the Francoist bureaucrats.

The Battle for the Interpretation

The journalist and CIA agent Thomas Wardel Braden once spoke about “the battle for Picasso’s mind” to sum up what North American agency was planning in the field of culture: to set up a counter front that pitted Western intellectuals against the Soviet model.Footnote68 The activities of these agents did little to change Picasso’s personal opinions. But as this essay has shown, there was indeed a real “battle for the interpretation” of his work, which took on new meanings in the context of the power struggles during the Cold War.

This story allows us to observe a whole series of tensions that affected not only the course of art history, but also the management of the painting’s material conservation and its circulation in the form of reproductions. During the late 1960s, Alfred H. Barr Jr was under pressure from two sides with regard to Picasso’s painting. On the one hand, there was pressure from the radical New York artists who were urging the painter to withdraw the mural from the museum because of the links that some of the museum’s patrons maintained with the US arms industry. And at the other extreme, there was General Franco’s government, which was trying to depoliticize Picasso’s work and place it in a museum that sought to show how open Spain’s regime was. Equipo Crónica’s Guernica series is a collectively produced narrative series of paintings that tells the fictitious history of what might have happened to Picasso’s painting in the context of the Cold War, a time when the painting became a political icon as well as a reproducible image—one that could become an impactful icon in the political struggle but could also turn into a rather banal cliché.

All these examples demonstrate how Guernica ceased to be tied to a specific historic event and began to lend itself to broader interpretations instead.Footnote69 On the subject of the Guernica 69 series, Tomás Llorens has pointed out the contradiction between “the initial explicit motivation,” which prompted Picasso to paint his painting in 1937, and its “current fate as a museum-worthy piece.”Footnote70 There are essentially two factors to this process of reinterpreting Picasso’s mural: one is its availability for public viewing in the halls of a museum, and the other is the possibility for the painting to be reproduced, either manually or mechanically, allowing it to live on outside the confines of the museum.

Liberated from its ties with a single historical event, Guernica became an icon that encapsulated violence and barbarism in the broader sense. The painting consequently became the object of contradictory interpretations, which sought to adapt it to the political context of the Cold War. This process developed through theoretical texts and new images—for instance, those created in Narrative Figuration or Pop art in its various guises. Across the board, Picasso’s painting opened itself up to a complex form of temporality. Looking to the past, art historians have compared Guernica with the apocalyptic miniatures produced in the Middle Ages; in this sense, it could be regarded as an example of modern Medievalism.Footnote71 As we have seen in this essay, the painting’s significance also stretched beyond 1936 and the Spanish Civil War. If only in an anachronistic way, Guernica continued to serve as a meaningful image for the conflicts that followed in the second half of the twentieth century.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Javier Ortiz-Echagüe

The paper was first presented at the 108th CAA Annual Conference, Chicago, 12–15 February 2020.

Notes

1 Julie Ault, Alternative Art New York 1965–1985 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002). On the role of Guernica in this context, see: Francis Frascina, “Artists’ Protests: Guernica and Vietnam War,” in Manuel Borja-Villel and Rosario Peiró, The Travels of Guernica (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2020), 223–242.

2 Lucy Lippard, “The Art Workers’ Coalition: Not a History” (Studio International, 1970) in Get the Message? A Decade of Art for Social Change (New York: E. P. Dulton, 1984), 11–12.

3 Deborah Wye, Committed to Print: Social and Political Themes in Recent American Printed Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1988), 68.

4 Hal Wingo, “The Massacre at My Lai,” Life (December 5, 1969): 36–45; see also “Americans Speak Out on the Massacre at My Lai,” Life (December 19, 1969): 46–47.

5 “Transcript of Interview of Vietnam War Veteran on His Role in Alleged Massacre of Civilians at Songmy,” The New York Times (November 25, 1969): 16.

6 Cited in Josefina Alix, Pabellón español, Exposición Internacional de París, 1937 (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 1987), 29. Unless otherwise stated, all translations in this article are by Isabel Adey.

7 Werner Spies, “Guernica und die Weltausstellung Paris 1937,” in Kontinent Picasso: Ausgewählte Aufsätze aus zwei Jahrzehnten (Munich: Prestel, 1988), 62–99.

8 On the political significance of the painting beyond the specific context of its creation, see: Jutta Held, “How do the Political Effects of Pictures Come About? The Case of Picasso’s Guernica,” The Oxford Art Journal, 11:1 (1998): 33–39.

9 Javier Tusell, “Guernica Comes to the Prado,” in Picasso’s Guernica: History, Transformations, Meanings, ed. Herschel B. Chipp (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988), 180–190. And more recently: Genoveva Tusell, El Guernica recobrado. Picasso, el franquismo y la llegada de la obra a España (Madrid: Cátedra, 2018).

10 “A request from Angry Arts to support the withdrawal of Guernica from the Museum of Modern Art, New York,” April 1967. In: https://guernica.museoreinasofia.es/en/document/request-angry-arts-support-withdrawal-guernica-museum-modern-art-new-york (accessed January 20, 2021). For the broader context, see: Francis Francina, “Guernica: Intellectuals, Dissent and the USA,” in The Art Workers’ Coalition, ed. Dario Corbeira (Madrid: Brumaria, 2010), 186.

11 Sam Hunter, The Museum of Modern Art, New York: the History and the Collection (New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1984), 22.

12 “As Picasso said to you: ‘It does most good in America’, and specially now. I do not believe one minute that Picasso is going to withdraw the painting,” Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler to Alfred H. Barr Jr, April 20, 1967. Available at: https://guernica.museoreinasofia.es/en/document/daniel-henry-kahnweilers-letter-alfred-h-barr-jr-dated-20-april-1967 (accessed January 20, 2021).

13 Pablo Picasso, “Why I Became a Communist,” New Masses (October 24, 1944), 11.

14 Gijs Van Hensbergen, Guernica. The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon (London: Bloomsbury, 2005), 185. Also see: Gertje Utley, Picasso: The Communist Years (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 111–112, and Sarah Wilson, “Loyalty and Blood. Picasso’s FBI File,” Picasso and the Politics of Visual Representation: War and Peace in the Era of the Cold War and Since, ed. Jonathan Harris and Richard Koeck (Liverpool: Tate Liverpool Critical Forum, 2013), 129–145.

15 Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War. The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (New York: The New York Press, 2000), 68. This first dove would be followed by many others. See: Gertje Utley, Picasso: The Communist Years, 117–133.

16 Cited in William Hauptman, “The Suppression of Art in the McCarthy Decade,” Artforum 1 (1973): 48.

17 Cited in Gijs Van Hensbergen, Guernica. The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon, 192.

18 Chicago Herald and Examiner (August 17, 1939), cit. in Herschel B. Chipp, Picasso’s Guernica, 166.

19 Alfred H. Barr Jr, “Is Modern Art Communistic?” (New York Times, December 14, 1952), in Defining Modern Art (New York: Abrams, 1986), 214.

20 “I said that the attacks were for the most part on the radical style of the pictures, but the radical politics of some of the artists was also mentioned,” Alfred H. Barr Jr, “Artistic Freedom” (College Art Journal, Spring 1953), in Defining Modern Art, 225.

21 On this subject see: Andrea Giunta, “The Power of Interpretation (or How MoMA Explained Guernica to its Audience),” Artelogie 10 (2017): http://journals.openedition.org/artelogie/953 (accessed January 20, 2021).

22 Alfred H. Barr Jr, Picasso: 75th Anniversary Exhibition (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1957), 75. This same text appears on the museum placard, as shown by the photograph shown in Genoveva Tusell, El Guernica recobrado, 84.

23 Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art. Abstract Expressionism, Freedom and the Cold War (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1983), 36.

24 Herschel B. Chipp, Picasso’s Guernica, 166–168; and, more recently, Rocío Robles, Informe Guernica: sobre el lienzo de Picasso y su imagen (Madrid: Ediciones Asimétricas, 2019), 37–38.

25 Clement Greenberg, “Picasso at Seventy-Five,” Arts Magazine (October 1957), in The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993), 32.

26 Gijs Van Hensbergen, Guernica. The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon, 154–177.

27 See Adam Hochschild, Spain in our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939 (Boston: Mariner Books, 2017).

28 Barbaralee Diamonstein, “Inside New York’s Art World: An Interview with Robert Motherwell,” Partisan Review (Summer 1979): 381.

29 Robert Motherwell, “The Modern Painter’s World” (Dyn 6, November 1944), in The Writings of Robert Motherwell (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 30.

30 Rocío Robles, Informe Guernica, 49.

31 John Peffer, Art and the End of Apartheid (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 49–50. I would like to thank Tenley Bick for this reference.

32 Jacopo Galimberti, Individuals Against Individualism: Art Collectives in Western Europe (1956-1969) (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2017), 178–179.

33 P. F. Althus, in Kunst und Politik (Karlsruhe: Badischer Kunstverein, 1970) n.p.

34 Kunst und Politik, no. 12.

35 “Equipo Crónica (Solbes, Toledo, Valdés),” in La postguerra. Documentos y testimonios, vol. 2, ed. Vicente Aguilera Cerni (Madrid: Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, 1975), 11.

36 The trend is very typical of those years, and the bibliography on this subject is extensive: Robert C. Hobbs, “Rewriting History: Artistic Collaboration Since 1960,” in Cynthia Jafee, Artistic Collaboration in the Twentieth Century (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1984), 64–87; Itzhak Goldberg, “Entre le politically correct et l’artistically correct, ou l’art collectif et la politique font-ils bon ménage?,” in Jean-Paul Ameline, Face à l’histoire 1933–1996: l’artiste moderne devant l’événement historique (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1996), 364–373; Charles Green, The Third Hand. Collaboration in Art from Conceptualism to Postmodernism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001). On the subject of Equipo Crónica in particular, see: Jacopo Galimberti, Individuals Against Individualism, 219–234.

37 Kunst und Politik, no. 49-51. The full series consists of 18 works, which are included in: Michèle Dalmace, Equipo Crónica. Catálogo razonado (Valencia: IVAM, 2001), 108–142. Also see Crónica del Guernica, ed. Fernando Castro Flórez (Valencia: IVAM, 2006).

38 Equipo Crónica, “Datos sobre la formación del Equipo Crónica,” Equipo Crónica (Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura, 1981), 21.

39 Genoveva Tusell, El Guernica recobrado, 68–75. On the history of this museum, see: María Dolores Jiménez-Blanco, Arte y Estado en la España del siglo XX (Madrid: Alianza, 1989), 131–213.

40 Communiqué from the Spanish Consul General in New York, Ángel Sanz-Briz, to the General Directorate of Cultural Relations on May 28, 1964, cited in Genoveva Tusell, El Guernica recobrado, 83.

41 J. M., “Guernica à Madrid?,” Le Monde (October 24, 1969); “Franco invites Picasso to return to Spain,” The Times (October 23, 1969); “Franco Favors the Return of Picasso and Guernica,” The New York Times (October 29, 1969). This reference and others can be found in: Genoveva Tusell, El Guernica recobrado, 68–75.

42 Genoveva Tusell, El Guernica recobrado, 25–41.

43 Jorge Luis Marzo, ¿Puedo hablarle con libertad, Excelencia? Arte y poder en España desde 1950 (Murcia: CENDEAC, 2010), 57.

44 Jutta Held, “How do the Political Effects of Pictures Come About? The Case of Picasso’s Guernica,” 38.

45 Cited in Pierre Cabanne, Pablo Picasso / His Life and Times (New York: Morrow, 1977), 522.

46 Roland Dumas, Dans l’oeil du Minotaure: le labyrinthe de mes vies (Paris: Cherche Midi, 2013), 88.

47 Two versions of the painting are shown in: Michèle Dalmace, Equipo Crónica. Catálogo razonado, 112–113. The painting from the Kunst und Politik exhibition catalogue is La visita II, which differs from the first version in various respects: In La visita I there are prison bars on the upper window, the perspective is slightly different, and a group a people can be seen entering through the doorway, rather than just one woman. The Minister for Information and Tourism, Manuel Fraga, can be recognized among the official delegation entering the room. This version underscores the fictitious presence of the painting in Franco’s Spain.

48 Ricardo Marín Viadel, Equipo Crónica. Pintura, cultura y sociedad (Valencia: Institució Alfons el Magnànim, 2009), 53.

49 Equipo Crónica, “Datos sobre la formación del Equipo Crónica,” 19.

50 “What is the cultural intention of Lichtenstein? Talking about painting. While Equipo Crónica’s appears, at first glance, completely different; the first visual impact of their works is of scenes of violence, and this impact appears to go semantically beyond the bounds of the limits of high-culture's conditions in order to allude directly to social tensions, just as they appear in the street,” Tomás Llorens, Equipo Crónica, 89.

51 See Carlos Antonio Areán, “Introducción al Pop-Art,” Hogar y arquitectura. Revista bimestral de la obra sindical del hogar 53 (julio-agosto 1963), 63: “If we discount the sublime creations of its four or five outstanding figures, it [Pop Art] will end up becoming pure decoration and will have a fate as sad as the one that befell geometric abstraction’s most thoughtless epigones”.

52 “Ce que je refuse totalement, c’est l’idée de pop art,” he told Jean-Paul Amelie and Bénédicte Ajac. See: “Entretien avec Eduardo Arroyo” (November 2, 2007), in Figuration narrative. Paris 1960–1972 (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux / Centre Pompidou, 2008), 285.

53 “Equipo Crónica (Solbes, Toledo, Valdés),” in La postguerra. Documentos y testimonios, vol. 2, 12.

54 “Guernica 69”, in Equipo Crónica (Madrid: Juana Mordó, 1976), 11.

55 See, for example, Pierre Couperie, Bande dessinée et figuration narrative (Paris: Musée des arts décoratifs, 1967). Recent exhibitions have considered Equipo Crónica’s work in this context: Figuration narrative. Paris 1960-1972 (Paris: Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 2008).

56 Valeriano Bozal, “De la nueva figuración al pop-art,” Cuadernos hispanoamericanos. Revista mensual de cultura hispánica 181 (1965): 58.

57 Barbara Rose, “Crónica desde Nueva York,” Goya. Revista de Arte 53 (March-April 1965): 322.

58 Iria Candela, “Picasso in Two Acts,” in Roy Lichtenstein: a Retrospective (London: Tate, 2012), 37.

59 Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (Partisan Review, Fall 1939), in The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 1, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1988), 14.

60 “We must not be deceived by superficial phenomena and local successes. Picasso’s shows still draw crowds, and T. S. Eliot is taught in the universities; the dealers in modernist art are still in business, and the publishers still publish some ‘difficult’ poetry. But the avant-garde itself, already sensing the danger, is becoming more and more timid every day that passes,” Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” 11.

61 Iria Candela, “Picasso in Two Acts,” 37.

62 John Coplans, “Talking to Roy Lichtenstein,” Artforum (May 1967), in Pop Art. A Critical History, ed. Steven Henry Madoff (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 201.

63 “I think Picasso the best artist of the century, but it is interesting to do an oversimplified Picasso—to misconstrue the meaning of his shapes and still produce art […]. It’s a kind of ‘plain-pipe-racks Picasso’ I want to do—one that looks misunderstood and yet has its own validity. A lot of it is just plain humor,” John Coplans, “Talking to Roy Lichtenstein,” Artforum (May 1967), in Pop Art. A Critical History, 201.

64 On this idea, see: Hal Foster, First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 62–108.

65 Their work could be categorised as “political pop”, which Jessica Morgan speaks about in: “Political Pop: An Introduction,” in The World Goes Pop, ed. Jessica Morgan and Flavia Frigeri (London: Tate Publishing, 2015), 16. See also: International Pop, ed. Darsie Alexander (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2015).

66 Equipo Crónica, “Datos sobre la formación del Equipo Crónica,” 20–21.

67 Jessica Morgan, “Political Pop,” 27.

68 Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War, 438. For more on this subject see: Lynda Morris, “The Battle for Picasso’s Mind,” in Picasso and the Politics of Visual Representation, ed. Jonathan Harris and Richard Koeck, 27–49.

69 “Following its tour of the United States Guernica had finally settled at MoMA for the New York art world to reassess it calmly as an image of a catastrophic world war that had finally been survived. It slowly moved from the condition of witness and prophecy back into the safer realm of artefact and history. Strangely, no longer harnessed to a single historical event, Guernica had finally released from its role as war reporter and propaganda machine. The period of its most enduring legacy was about to begin”, Gijs Van Hensbergen, Guernica. The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon, 155.

70 Tomás Llorens, Equipo Crónica (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1972), 43.

71 Alexander Nagel, Medieval Modern. Art Out of Time (London: Thames & Hudson, 2012), 15.