Abstract

Himalayan communities live in marginal environments. They are dependent on ecosystem services and thus highly exposed to climate variability and change. This study aimed to help understand how mountain communities perceive change, how change impacts their livelihoods, and how they respond to change. Forty focus group discussions and 144 in-depth interviews at the household level were conducted in 20 villages in northwest India and across Nepal. Perceptions of change were compared with actual climate records where available. Respondents considered rainfall patterns to be less predictable and had experienced an overall reduction in water availability, severely affecting their harvests. Increased temperatures were also reported, particularly at higher elevations. People responded to the changing conditions with a wide range of coping and adaptation mechanisms. However, many of these mechanisms will not be sustainable in view of the likely magnitude of future climate change, and they are also restricted to social groups with appropriate assets. The poor, lower caste families, women, and other marginalized groups are particularly vulnerable and less able to adapt. Targeted efforts are required to move from coping to adapting and to avoid inequalities between social groups increasing due to the different adaptive capacities.

1. Introduction

People living in mountainous areas in the developing world, including the Himalayas, generally face high levels of poverty as a result of remoteness, poor accessibility, and marginalization. They are highly dependent on ecosystem services, and often have limited political influence and economic opportunities (Hunzai, Gerlitz, & Hoermann, Citation2011). Many of the mountain ecosystems on which mountain communities depend are highly fragile and subject to both natural and anthropogenic drivers of change (Körner et al., Citation2005). Climate change is expected to exacerbate the existing challenges faced by mountain people and their environments (Macchi & ICIMOD Team, Citation2010; RSAS, Citation2002). The greater Himalayan region as a whole is very sensitive to climate change and has already experienced above-average warming particularly at higher elevations (Xu et al., Citation2009). According to a study by Nogues-Bravo, Araujo, Errea, and Martinez-Rica (Citation2007), the warming trend over mountain areas is likely to continue during the twenty-first century, particularly in the high-latitude and mid-latitude mountains in Asia, and at a greater rate than observed in the twentieth century.

Despite these projections, much uncertainty remains. Lack of consistent climate records in the Himalayan region and extreme spatial variation mean that most climate models are inadequate to produce scenarios at the local level. Conversely, adaptation is local and highly context specific. One way to overcome this is to focus on communities' perceptions of change and their inherent capacity to adapt. Analysing historical records and response strategies can be of great value in understanding the feasibility of planned adaptation initiatives (Adger, Huq, Brown, Conway, & Hulme, Citation2003; Agrawal & Perrin, Citation2008; Brooks & Adger, Citation2005; Füssel & Klein, Citation2006). What is more, the ability of a community to cope with current climate variability can be an important indication of their capacity to adapt to future climate change (Adger et al., Citation2003; Füssel & Klein, Citation2006). Thus, a better understanding is needed of the repertoire of responses of communities, whether traditional or innovative. This knowledge will provide an important basis for future adaptation planning, and will take advantage of and strengthen existing autonomous strategies to enhance the resilience of the rural poor (Agrawal & Perrin, Citation2008).

The general objective of the present study was to improve the understanding of mountain communities' vulnerability and adaptive capacity, and to formulate recommendations on how to increase their resilience to change, using rural communities in the western and central Himalayas as an example. The specific objectives were to identify people's perceptions of climate variability and change; to understand how people's livelihoods are affected by climate and socioeconomic change; to assess existing response strategies and their sustainability in view of future climate change; and to understand how vulnerability and adaptive capacity vary among different social groups.

2. Theory and methods

2.1. Adaptation and vulnerability to change in mountains

For the purpose of the study, people's response strategies to change were categorized as either coping or adaptation mechanisms. ‘Coping mechanisms’ are understood as ‘short-term actions to ward off immediate risk, rather than to adjust to continuous or permanent threats or changes’ (ICIMOD, Citation2009); and ‘adaptation mechanisms’ as a set of longer term ‘strategies and actions in reaction to or in anticipation of change taken by people in order to enhance or maintain their wellbeing’ (Goulden, Naess, Vincent, & Adger, Citation2009). Adaptation is an active adjustment, whereas ‘adaptive capacity’ is the potential of an individual, household, or community to adjust to change (Brown, Citation2010). In the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), ‘vulnerability’ is defined as ‘the propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected by the impacts of climate change. The definition of “vulnerability” encompasses various concepts including sensitivity or susceptibility to harm and the lack of capacity to cope and adapt to change’ (Citation2014a). Exposure and vulnerability to change are dynamic and vary across temporal and spatial scales depending on economic, social, geographic, demographic, cultural, institutional, governance, and environmental factors (IPCC, Citation2012). Adger and Kelly (Citation1999) suggest that an individual's social vulnerability is mainly determined by access to resources and diversity of livelihood strategies, as well as by the social status of individuals or households within a community. Collective social vulnerability is further determined by institutional and market structures, such as the prevalence of informal and formal social security and insurance systems, as well as by infrastructure and well-being. The ability to implement adaptation strategies requires assets, including entitlements to financial, social, and physical capital, as well as human and natural resources (Brooks & Adger, Citation2005). Entitlements are, in turn, determined by different broad categories of inequality; those relevant in the study area include gender, caste, economic status, and ethnicity. Thus, social status is another key determinant of adaptive capacity.

Mountain areas in the developing world are undergoing rapid change and are exposed to the impacts of both climate change and economic globalization (O'Brien & Leichenko, Citation2000). In a mountain environment, both individual and collective social vulnerability and exposure to impacts associated with climate variability and change tend to be high. Mountain communities have a long history of adapting to extreme environmental conditions (Jodha, Citation1997), and have multiple livelihood strategies that build upon livelihood assets, in particular human, social, and natural capital. However, the speed of climate and socioeconomic change, together with mountain communities' lack of access to financial and physical capital, hampers their capacity to adapt (Macchi, Citation2011).

2.2. Why perceptions?

Hydro-meteorological data in the Hindu Kush-Himalayas (HKH) are extremely limited, and the marked microclimatic variations in elevation and aspect mean they are not representative of local climatic conditions (Singh, Bassignana-Khadka, Karky, & Sharma, Citation2011). There are very few hydro-meteorological stations, especially at higher elevations, and long-term weather data are inadequate. In addition, modelling exercises have limited use at the community level, as communities orient their responses to perceived changes rather than climate data or predictions. Following research in eastern Tibetan villages, Byg and Salick (Citation2009) considered that knowledge of local perceptions was fundamental for gaining a better understanding of the impact of climate change, and identifying issues that have previously been overlooked as a result of the uncertainty about magnitude and impacts of weather factors at a particular location and the fact that climate impact depends on ecological, social, and economic factors.

Communities whose lives and livelihoods are dependent on ecosystem services, particularly subsistence farmers, are aware of changes and have indigenous knowledge which may stretch back for decades, as shown in studies from the Himalayas (Chaudhary & Bawa, Citation2011; Chaudhary et al., Citation2011; Vedwan & Rhoades, Citation2001) and other regions of the world (Orlove, Roncoli, Kabugo, & Majugu, Citation2010; Thomas, Twyman, Osbahr, & Hewitson, Citation2007). Such knowledge can supplement scientific climate analysis and help improve the coarse spatial resolution of climate forecasts. Thus perceptions of climatic changes can help fill gaps in scientific weather data and can be indispensable to researchers and policymakers.

2.3. Study area

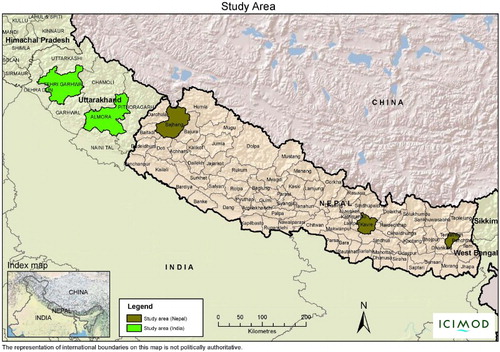

The study was conducted across 20 villages in northwest India (in Almora and Tehri Garhwal districts in Uttarakhand) and far-western, central, and eastern Nepal (in Bajhang, Kavre, and Terhathum districts) (). The livelihoods of the people living in these districts are mainly based on agriculture and livestock, and increasingly on labour migration. The selected villages varied in elevation (from 400 to 2400 masl) and accessibility to capture differences in coping and adaptive capacities ().

2.4. Adaptation policies in the study area

In recent years, most countries in the Himalayan region have developed climate change policies and adaptation plans (Singh et al., Citation2011), including Nepal and India. These policies and frameworks cover both the study areas in this report. The recently proposed draft constitution of Nepal states that each citizen shall have the right to adaptation and shall receive compensation for losses and damage caused by climate-related disasters (Tiwari, Balla, Pokharel, & Rayamajhi, Citation2012). Nepal's Climate Change Policy of 2011 stresses that communities who depend on natural resources for their livelihoods, such as those observed in this study, are particularly vulnerable to climate change and should benefit from any governmental efforts to mitigate or adapt to climate change (GON, Citation2011). India has developed a National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), which contains a specific National Mission for Sustaining the Himalayan Eco-system (GOI, Citation2008). All Indian states have been asked to prepare State Action Plans for Climate Change, and in 2012 the State of Uttarakhand prepared the ‘Uttarakhand Climate Change Action Plan’ in line with the NAPCC. The focus is on strengthening the resilience and adaptive capacities of communities, as well as on public and private infrastructure and conservation of the Himalayan ecosystem (GOU, Citation2012).

Notwithstanding the considerable effort at national and sub-national levels to formulate policies and frameworks aimed at strengthening the resilience and adaptive capacities of communities, concrete impacts at the local level of the study sites remain difficult to discern. Uttarakhand has been undertaking a range of initiatives across various sectors that support the building of community resilience, but as they have not been explicitly classified or recognized as aiming towards building adaptive capacity (GOU, Citation2012), it is difficult to measure their effectiveness in supporting local adaptation. In Nepal, several plans have been developed with a specific focus on local adaptation. In 2010, the government endorsed the National Action Plan for Adaptation (NAPA) to prioritize climate change vulnerabilities and adaptation measures (NAPA/MOE, Citation2010), and in 2011 the Local Adaptation Plan for Action (LAPA), to increase the efficiency of NAPA planning and implementation in local communities through a bottom-up, site-specific, and inclusive approach (LAPA/MOE, Citation2012; Watt, Citation2012). However, the challenge of implementing these plans at local level remains. The NAPA identifies weak governance, lack of infrastructure, limited financial resources, and lack of public awareness on climate-related disasters and climate change issues as the major barriers to absorbing the financial allocations for local-level adaptation (NAPA/MOE, Citation2010; Tiwari et al., Citation2012). Hence, while there is evidence of significant effort at both study sites in terms of national, sub-national, and even local planning, the operationalization of adaptation strategies at the local level remains a challenge, as does the monitoring and evaluation of individual interventions.

2.5. Methods

The study was built on the assumptions that (a) climate variability and change is already noticeable to, and directly affecting the livelihoods of, the people in the study area; (b) climate variability is not a new phenomenon to mountain people and they have developed a wealth of traditional response strategies; (c) change in the Himalayas is driven by a variety of environmental and non-environmental drivers, not only climate; and (d) vulnerability to climate change is unevenly distributed across and within communities.

The following research questions guided the study:

How do different mountain communities perceive and interpret climate change and do these perceived changes correspond to observed climate data in the study area?

What are the major impacts of these changes on the communities' livelihoods?

How do mountain communities respond to the perceived changes and how sustainable are these response strategies in view of future climate change?

Are there any differences between social groups in terms of perceptions of change and the implications for livelihoods and adaptive capacity?

These questions were answered using the vulnerability and capacity assessment (VCA) approach (Macchi, Citation2011), a combination of the conceptual framework for vulnerability assessments (e.g. Füssel & Klein, Citation2006), and the sustainable livelihoods approach (DFID, Citation1999). The objective of the VCA approach is to identify the key vulnerabilities of mountain communities to change, and the livelihood assets and capacities they have to adapt (Macchi, Citation2011). The time frame in which the communities were asked to report the changes they have perceived varied between 10 and 20 years, depending on the age of the respondent.

The methods applied were mainly qualitative and consisted of focus group discussions (FGDs), semi-structured interviews at the household level, and participant observation. Climate data from hydro-meteorological stations were also analysed where available and compared with people's perceptions of change. A strong focus was placed on gender aspects, especially as with increasing male labour outmigration, women are becoming the main food producers in the Himalayas (Banerjee, Gerlitz, & Hoermann, Citation2011; Leduc, Citation2011).

The fieldwork was conducted between July 2010 and February 2011. Two FGDs were held in each of the 20 villages, 1 with women and 1 with men, and 144 in-depth interviews were carried out (32 in Almora and 32 in Tehri Garhwal districts in Uttarakhand, India; 32 in Terhathum, 32 in Bajhang, and 16 in Kavre districts in Nepal). Participants were selected on the basis of age, gender, and well-being.

3. Results

3.1. Communities’ perceptions of change

The key findings on perceptions of change are summarized in , disaggregated by district. Respondents across the study area reported a significant reduction in water availability. They felt that the amount and duration of rainfall had declined significantly over the past 5–10 years, with a stronger reduction reported in the west than in the east, and that precipitation events had become more erratic. Particularly the winter rains had become scarce or stopped completely over the past few years, and in many places at higher elevation snowfall had decreased significantly or been completely absent over the past 5–10 years. People consistently reported a delay in the onset of the monsoon, that the monsoon was more unpredictable, that the dry season was longer and more intense, and that water levels in springs and groundwater sources had dropped. New dry periods were being experienced, particularly during the rainy season, which had reduced harvests. Many respondents thought that the number of hot days had increased and the winters had become milder, and there was a perception of increasing temperature at higher elevations. In addition to the changes in climatic conditions, many respondents across the entire study area also reported increasing occurrences of crop pests and disease.

Table 1. Details of study villages.

Table 2. Summary of perceptions of change.

No difference was identified in terms of perception of change between different social groups or as a result of variations in accessibility. Younger women often found it more difficult to assess differences in climatic conditions as they had moved to the village through marriage and therefore did not have the necessary time horizon. Elderly people found it easiest to report on change, and many stressed the increase in temperature when compared to their childhood.

The respondents were insecure about the reasons for the changes in weather patterns. Many mentioned environmental reasons such as widespread deforestation and population growth, which has led to increased pollution. Some regarded the perceived changes as a punishment and believed that the gods had become angry. One farmer (aged 72) from Terhathum said ‘Earlier, everything was balanced. These days, the earth is upside down and the gods are rude with us.'

Similar results were found by Chaudhary and Bawa (Citation2011) in their study of local perceptions of climate change in Ilam district in eastern Nepal (close to Terhathum). They found that people reported the prevalence of heavy short-duration downpours, rising temperatures, diminishing water sources, and increasing crop pests. Their study also suggested that changes were perceived as being greater by people living at higher elevations. Scarce winter rainfall in the previous five to six years, along with untimely, unseasonal, and erratic rainfall, has been recorded in the middle and western Himalayas (Joshi & Joshi, Citation2011; Kelkar, Narula, Sharma, & Chandna, Citation2008; Vedwan & Rhoades, Citation2001). Kelkar et al. (Citation2008) found similar conditions in Uttarakhand, noting that residents had experienced a decline in snowfall and duration of snow cover – and a complete absence of snow has been observed in some villages in Kangchenjunga (Chaudhary et al., Citation2011).

3.2. Comparison of perceptions of change with observed climate records

Records from hydro-meteorological stations were analysed in order to compare the communities' perceptions of change with meteorological data. However, there is significant topographical and altitudinal variation within small areas in the Himalayas and data from individual stations provide only an indicative idea of the situation in the study villages, located some distance away. In addition, some of the measurements were incomplete, short, or suspected of containing errors. Nevertheless, the patterns from these stations can be used to some extent as proxies for local measurements to compare with the communities' perceptions of change. In Nepal, 30 years of records (1980–2009) were available from 3 hydro-meteorological stations (2 in Bajhang and 1 in Terhathum) and 17 years of records (1993–2009) from 1 station (Dhulikhel) in Kavre district, but data could not be obtained for Uttarakhand.

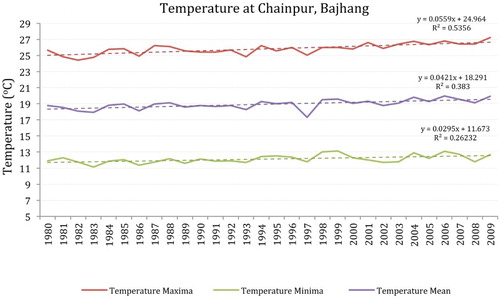

The precipitation data showed marked inter-annual variability and highly localized rainfall patterns, with no clear trends over the past 3 decades except for the station in Kavre district, which showed a decreasing trend in total annual precipitation over the 17-year time span. Winter rains were almost, or completely, absent in the two years preceding the study at all four stations. The year preceding the study (2009) had comparatively low overall rainfall and in some places drought-like conditions, which may have influenced people's perceptions. Temperature data were only available from one station (at 1300 masl in Chainpur, Bajhang) for 1980–2009. There was a marked increase in mean annual air temperature over that period, with an average increase of 0.05°C/year in the mean maximum temperature and 0.03°C/year in the mean minimum temperature (). This observation matches people's perception. The marked variability in precipitation and recent drier trend indicates that people's perceptions may also be strongly shaped by their experiences in the most recent years.

These findings are corroborated by Shrestha and Aryal (Citation2010), whose analysis of climate data from 49 stations in Nepal since 1977 confirms that precipitation data do not reveal any significant trend. Their study found an average annual temperature increase of 0.06°C/year in Nepal, with progressively greater warming rates at higher elevations and more pronounced warming in the winter than in other seasons.

3.3. Impacts of change on livelihoods and community well-being

Change can rarely be attributed to a single driver. The findings should, therefore, be interpreted as the result of multiple drivers of change, related to rapidly changing climatic, socioeconomic, and cultural conditions. The changes observed by the communities related mainly to food, water, and income security; workloads; and health.

The main impact of change perceived by the communities was a significant reduction in outputs of staple and cash crops, mainly due to reduced overall water availability and lack, or inappropriate timing, of precipitation, and increased occurrence of crop pests and diseases, which the communities attributed to changes in weather patterns, increased use of fertilizers, and monocropping. Other reasons for the decreasing outputs include fragmentation of landholdings, and fallowing of arable land due to a reduction in the agricultural workforce, particularly in migrant households (Jain, Citation2010; Leduc, Citation2011). Prolonged dry seasons result in a drastic reduction in the availability of grass and other sources of fodder, as well as in drinking water for livestock, forcing people, particularly women, to travel farther and longer to collect fodder and water or to lead animals to water sources. As a result, communities in Uttarakhand have steadily reduced the number of big ruminants over the past years. This change may also be linked to labour constraints, particularly in migrant households, as goats require less labour than big ruminants. The shift has had negative side effects. It is linked to the decreasing availability of manure for agriculture, further reducing agricultural productivity, and a decreased availability of animal power for cultivating the land, thus increasing workloads. ‘Now we try to plough our smaller fields with hand ploughs, while for larger fields we hire bulls’, reported a woman from Tehri Garhwal. Farmers from Uttarakhand reported that orange and apple trees had started to flower twice a year as a result of increasing temperatures, increasing the quantity but decreasing the quality of the fruit. Communities living close to rivers reported a drastic reduction in fish stocks due to lowering water levels as well as overfishing. The lack of fuelwood and reduction in non-timber forest products across the study area can only be indirectly linked to climate change. The main reason for the reduced availability is overexploitation. However, communities also claimed that forest regeneration had been harmed by water scarcity.

Food insecurity, which is generally precarious in most of the study area, particularly in far-western Nepal (FSMTF, Citation2010), had increased as a result of the reduced yields. Women from Uttarakhand reported increased food insufficiency leading to skipped meals. Some communities in Nepal reported that, with growing food scarcity, stress and mental tension had increased.

Respondents attributed some health problems, like increased incidences of heat stroke and vector-borne diseases, to the changing climatic conditions. Women in Kavre complained of increased headaches while working in the fields because of extreme temperatures. Communities also reported that the water quality was deteriorating and that the reduced availability of medicinal plants made them more reliant on expensive western health treatments. Finally, the presence of mosquitoes at higher elevations and/or during seasons when they previously were not present is potentially impacting on the health of the communities.

3.4. Community-based responses to change

Communities across the study area were responding to the changing conditions with a wealth of different strategies based on their local knowledge. Some strategies are new, others were developed in the past to deal with climate variability and other challenges, such as low agricultural productivity and limited economic opportunities. The most important response strategies to climate and socioeconomic change are summarized in .

Table 3. Community responses to climate and socioeconomic change.

The observed community-based strategies and actions can be classified as a mix of coping and adaptation. However, there is a continuum between these and it is difficult to strictly classify response strategies as one or the other.

One of the observed coping strategies was adjustment to the agricultural calendar in response to changing precipitation patterns, in particular delayed sowing of both the main winter and summer crops in rainfed fields. However, this practice has reportedly had a negative impact on yields due to the shortening of the growing season. It is also not applied every year, but depends on the specific yearly rainfall pattern. Another strategy is to re-sow the same or a different crop after an early season failure. In two villages in Terhathum, and one village each in Almora and Tehri Garhwal, cases were observed where farmers had ceased planting paddy completely due to lack of, or untimely, rainfall. In Uttarakhand, a shift was observed from big ruminants to smaller livestock, in particular goats, in response to reduced availability of fodder and water; but this may also lead to increased soil erosion and land degradation. In Nepal, fresh grass was replaced by dry grass and leaf litter for fodder for cows and buffaloes, which led to lower milk production. The response to increased infestations of crop pests and disease included traditional practices of spreading ash, cow urine, or salt, and crop rotation. However, farmers complained that ‘earlier such traditional methods were effective in controlling the pests, but now due to the increase in pest infestation, these methods have become ineffective’. As a result, those who can afford it increasingly rely on chemical pesticides. When agricultural yields are insufficient or harvests fail, people (particularly women) skip meals or buy food and essential goods from the market. They are often forced to take loans from local moneylenders at high interest rates as formal financial services are scarce, or, as a last resort, to sell assets ranging from livestock to property.

The observed adaptation strategies ranged from replacement of crop varieties or types with more climate resilient ones, to increased engagement in off-farm labour. In Bajhang, for example, upland rice, locally known as ghaiya dhan (an indigenous short-stalked rice variety that is traditionally grown on slopes without irrigation and thus requires less water than other varieties), was reintroduced by farmers from Rayal (950 masl) to replace the lamo dhan (long-stalked rice, which is preferred by the communities but requires more water) that they had stopped growing some 8–10 years previously due to lack of water. In a number of the study villages in Uttarakhand, communities have replaced rice with the traditional, but less favoured millet (mandua), as reportedly millet is more water stress tolerant than rice. Some farmers from these villages also planted madira (fodder grass) in parts of their rice fields in order to ensure that if the rice harvest failed, the madira would at least provide fodder for their livestock. In both Uttarakhand and Terhathum, ginger cultivation is increasing because it is believed to better withstand water and temperature stress, as well as fetching a higher price. Benefiting from rising temperatures, new crops have been introduced, and areas previously unfavourable for agriculture due to low temperatures are now being used as arable land. For example, farmers in Surma in Bajhang district at 2400 masl are now able to grow millet. Also, in some places, more than one crop cycle is possible per year. In Terhathum, fruit such as lychees and mangos, traditionally grown in Nepal's southern Terai lowlands, are now being grown in villages at higher elevations. Upward movement of plant species and a trend towards longer growing seasons in mountainous areas in the HKH region have also been described in the IPCC AR5 (IPCC, Citation2014c).

Changes in production technologies were also reported. Mulching is a traditional strategy employed to retain soil moisture. In Terhathum, farmers stated that they ploughed immediately after manuring in order to enhance soil moisture. In the same district, instead of sowing rice into a flooded seedbed, a ‘dry nursery’ technique was innovated. Seeds are now pre-soaked and covered with moist leaves and mulch for two to three days until germination starts. The newly germinated seedlings are then spread directly over the mulched fields. This practice has been quite effective and helps farmers to avoid the high mortality that takes place in normal seedbeds with severe moisture stress. Other technologies reported in Bajhang included soaking maize seeds in water before dibbling them deep into the ground in order to guarantee sufficient moisture for germination.

In Uttarakhand, traditional water-sharing systems, which had become diluted over the years, have been revived in response to reduced water availability. Fields are again being irrigated on a rotational basis using traditional irrigation channels. Fields located at the head of the channel are irrigated first followed by subsequent farms. This arrangement has helped the communities to better utilize their scarce water resources for irrigation. However, farmers whose fields are located at the bottom of the irrigation channels, and who belong to a lower economic stratum, are reportedly being forced to delay the sowing of rice by 15–30 days, which adversely impacts on their yields.

Communities across the study area have made efforts to diversify their livelihoods by collecting and selling non-timber forest products. For example, the collection of yarsagumba (Cordyceps sinensis), an extremely valuable material in eastern medicine, has become a major source of income for communities situated at higher elevations in Bajhang. Other livelihoods diversification approaches include increased involvement in wage labour, both on- and off-farm and within and outside the village. In Uttarakhand, many people, especially the youth, have shifted to non-farm-based livelihoods such as tourism-related activities. In Terhathum, some respondents took up carpentry and other trades as alternate sources of income. Labour migration was reported to be increasing in almost half of the studied villages. In the remaining villages, it was either uncertain whether an increase had occurred or there was no change reported. Most of the studied areas are traditionally migrant areas.

Analysing the different coping and adaptation strategies, it is striking that the vast majority continue to be land based. This implies a continuing high dependence of the livelihood systems in the study area on ecosystem services, which are already under stress and are expected to become increasingly so (Körner et al., Citation2005), rendering the communities vulnerable to future climate change. Overall, only a few non-land-based adaptation strategies were observed. Furthermore, most of the observed coping strategies had a short-term orientation and were reactive rather than anticipatory. Some, such as re-sowing after an early season crop failure or borrowing money, deplete livelihood asset bases, rendering people more vulnerable. It is therefore questionable whether or not the observed strategies will be sufficient to offset the predicted magnitude of climate change in the Himalayas.

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in vulnerability and adaptive capacity

Overall, people in all the study districts thought that they were mostly negatively impacted by climate variability and change. Water scarcity, unpredictable weather events, and increasing crop pests were identified as among the biggest challenges. The adverse impacts of change on livelihood systems were generally perceived to be stronger in the west than in the east, and food insecurity was also more marked in the west. In all areas except Kavre (which is much more accessible), the diversity of livelihood options is low and highly dependent on natural resources and ecosystem services. Limited accessibility and high costs mean that there is a lack of basic infrastructure in many of the villages including, in Nepal, limited access to electricity. In Bajhang, road infrastructure was rudimentary, with as much as seven hours walking distance to the next motorable road, which severely limits economic opportunities. Access to markets becomes even more of an issue during the rainy season, as the roads are frequently disrupted by landslides. Across the study area, access to financial services from formal institutions, including insurance, is highly constrained, and where it exists there are often issues with implementation and equity. All this suggests a high level of individual and collective social vulnerability to change in the studied communities, which increases with inaccessibility and marginalization.

The adaptive capacity of the communities was also generally low, but varied between social groups. Different levels of economic prosperity greatly influenced the adaptive capacity of the respondents in the study area. The poorest households were highly dependent on agriculture and therefore strongly exposed to impacts associated with climate variability and change. The landholdings of the poor (if they owned any) also tended to be smaller and less viable than those of people with higher incomes. The educational background of the poorer farmers was also generally lower. In Uttarakhand, for example, only 35% of the respondents in the extremely poor category were literate, compared to 51% in the wealthiest category. When returns from agriculture are insufficient, lack of education limits the ability to find skilled employment. The poorest households were also the ones with the fewest migrants and thus with the least access to financial remittances, which, combined with very low incomes (approximately 20 USD per month in Tehri Garhwal, Uttarakhand), resulted in low savings and thus low economic resilience to shocks. Across the study area, lack of financial capital and limited human capital made it difficult for the respondents to diversify their livelihoods, for example, by growing cash crops or by setting up a small business. They also found it difficult to obtain loans due to the lack of collateral.

Women at the study sites in both countries have limited legal rights over the resources they manage, including land and other productive resources (Leduc, Citation2011). In Nepal, unmarried women have to return their share of parental property upon marriage (if they have received any) (World Bank & DFID, Citation2006). Also, women in the study area generally have very low levels of formal education and there is a large literacy gap between men and women. The lowest female adult literacy rate in the study area was in Bajhang, with a 40% literacy rate in 2011 (GON, n.d.; preliminary results from the 2011 census) compared to 73% for men. The remuneration for wage labour is also significantly lower for women than for men. In Terhathum, women earn half as much as men for the same type of work. Moreover, the coping strategies (e.g. re-sowing after an early season failure or fetching water and fodder from farther away) are mostly implemented by women, increasing their workloads. The findings also suggest that, as agricultural returns decrease, there is increasing pressure on men, particularly those from poorer families, to become involved in off-farm activities. In Nepal, 44% of all households have one or more household members (mostly young men) working elsewhere (FSMTF, Citation2010). This places a burden on both the migrant family member, who is often working under difficult conditions far away from home, and those left behind, particularly women, children, and the elderly, whose workloads increase. On the other hand, as mentioned above, remittances can act as a safety net and render those who have access to them more resilient to stress.

Besides well-being and gender, the still prevalent Hindu caste system also influences vulnerability and adaptive capacity. Dalits (those traditionally regarded as ‘untouchable’) in the study area were found to either own no land or to have comparatively small plots with low agricultural productivity. Traditionally, they work in low esteemed trades or as wage labourers in other people's fields. Some Dalits are still part of the haliya system, under which they receive one meal a day in return for wage labour on other people's fields. Of the nine Dalit households interviewed in Nepal, only five owned land; all five plots were comparatively small, and only one had access to irrigation. The situation was similar in Uttarakhand, where Dalits had disproportionately small landholdings of inferior productivity. This renders Dalit households food insecure and highly dependent on wage labour opportunities, which have become limited with declining agricultural productivity. Indigenous groups were only part of the study in eastern Nepal. Although generally better off than Dalits, many cited discrimination as a reason for poverty and said that they lacked education and marketable skills, limiting their capacity to diversify their livelihoods and adapt to change.

Overall, given that the potential to implement adaptation strategies requires access to resources (e.g. the potential to migrate or to engage in off-farm activities), the study indicates that those belonging to the lowest economic stratum and living in the most remote areas are the least able to adapt. Conversely, wealthier and better-educated households living close to market centres tend to be the most resilient to shocks, as they generally own bigger areas of land and higher numbers of livestock; have more diversified income sources; and have more strongly developed formal and informal safety nets.

4.2. Conclusions and recommendations

The findings reveal that the livelihoods of the studied communities are already affected by climate variability and change. Change has been noticed by people regardless of their social group. Water stress is perceived to be more severe in the west than in the east. Increasing water scarcity and erratic rainfall events, as well as increases in crop pests and disease, have had negative repercussions on yields, exacerbating already existing food, water, and income insecurity. However, some changes also bring opportunities, such as suitable climates for certain crops or more than one crop cycle per year at higher elevations. The communities' perceptions of change were largely consistent with the recorded climate data, particularly recent data. Nevertheless, there is still great uncertainty regarding future climate change in the Himalayas. Enhancing the knowledge base through coordinated research will be key for reducing uncertainty and enabling the development of targeted adaptation measures that tackle specific climate risks.

The communities' response strategies to climate variability and change are a mix of coping and adaptation strategies. Most are highly dependent on natural resources and ecosystem services, and are thus susceptible to future climate change. A majority of the responses have a short-term orientation and are reactive rather than anticipatory. In addition, many of the identified coping strategies deplete the livelihood asset base, and may render a household more vulnerable if another shock occurs. Hence, it is questionable whether these strategies will be sufficient to withstand the predicted magnitude of future climate change in the Himalayas. Appropriate longer term adaptation strategies, including land- and non-land-based options that build on mountain communities' knowledge, need to be developed, rather than focusing on short-term responses, which may reinforce vulnerability over the longer term. In this context, it will be crucial that adaptation strategies are based on women's knowledge and capacities, as women are, or are becoming, the main food producers in the Himalayas.

The study also found that vulnerability varies between different social groups, and that many response strategies are restricted to those with access to the livelihood assets required to adapt to change. Poverty has been identified as being the most important determinant for vulnerability. Many of the poor reported that lack of entitlement to financial, human, and physical capital limited their options to cope with or adapt to changing conditions. Vulnerability has been found to be particularly high where poverty intersects with discrimination, whether because of gender, caste, or ethnicity. This is also confirmed by the IPCC AR5, which states that heightened vulnerability is ‘the product of intersecting social processes that result in inequalities in socioeconomic status and income as well as in exposure. Such processes include, for example, discrimination on the basis of gender, class, ethnicity, age and (dis)ability’ (IPCC, Citation2014b, p. 7). Thus, in order to enhance mountain peoples' resilience to change, the underlying causes of vulnerability need to be addressed, in particular, poverty and social inequality, limited livelihood options and accessibility, and political and economic marginalization.

Finally, even though great efforts have been made recently in terms of formulating adaptation policies in the study areas, there is a need to raise awareness among policymakers about the high vulnerability of mountain communities and fragility of mountain ecosystems, and to ensure that adaptation policies appropriately reflect these specific characteristics and needs. Given that mountain areas are generally still politically and economically marginalized, it will also be crucial that sufficient resources are allocated for the operationalization of these policies, in order to foster pathways to anticipatory and targeted adaptation and increased resilience of the most vulnerable.

References

- Adger, W.N., Huq, S., Brown, K., Conway, D., & Hulme, M. (2003). Adaptation to climate change in the developing world. Progress in Development Studies, 3(3), 179–195. doi: 10.1191/1464993403ps060oa

- Adger, W.N., & Kelly, P.M. (1999). Social vulnerability to climate change and the architecture of entitlements. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 4(3–4), 243–266.

- Agrawal, A., & Perrin, N. (2008). Climate adaptation, local institutions, and rural livelihoods (IFRI Working Paper #W081-6). Ann Arbor: International Forestry Resources and Institutions Program, School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Michigan.

- Banerjee, S.J., Gerlitz, Y., & Hoermann, B. (2011). Labour migration as a response strategy to water hazards in the Hindu Kush–Himalayas. Kathmandu: ICIMOD.

- Brooks, N., & Adger, W.N. (2005). Assessing and enhancing adaptive capacity. In B. Lim & E. Spanger-Siegfried (Eds.), Adaptation policy frameworks for climate change: Developing strategies, policies and measures (pp. 165–181). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, K. (2010). Resilience and adaptive capacity. Climate Change and Development Short Course: Presentation. Norwich: UEA International Development.

- Byg, A., & Salick, J. (2009). Local perspectives on a global phenomenon – climate change in eastern Tibetan villages. Global Environmental Change, 19, 156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.01.010

- Chaudhary, P., & Bawa, K.S. (2011). Local perceptions of climate change validated by scientific evidence in the Himalayas. Biology Letters. doi:1098/rsbl.2011.0269

- Chaudhary, P., Rai, S., Wangdi, S., Mao, A., Rehman, N., Chhetri, S., & Bawa, K.S. (2011). Consistency of local perceptions of climate change in the Kangchenjunga Himalayas landscape. Current Science, 101, 1–10.

- DFID. (1999). Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. London: Author. Retrieved March 22, 2011, from http://www.eldis.org/vfile/upload/1/document/0901/section1.pdf

- FSMTF. (2010). The food security atlas of Nepal. Kathmandu: Food Security Monitoring Task Force WFP, Nepal Development Research Institute.

- Füssel, H.-M., & Klein, R.J.T. (2006). Climate change vulnerability assessments: An evolution of conceptual thinking. Climatic Change, 75, 301–329. doi: 10.1007/s10584-006-0329-3

- GOI. (2008). National adaptation programme for climate change India. New Delhi: Prime Minister's Council on Climate Change. Government of India. Retrieved June 1, 2014, from http://www.moef.nic.in/downloads/home/Pg01-52.pdf

- GON. (2011). Status of climate change in Nepal. Kathmandu: Ministry of Environment, Government of Nepal.

- GON. (n.d.). e-popinfo Nepal. Population Division, Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal. Retrieved June 6, 2014, from http://demo.via.net.np/epopinfo/districts/details/id/68

- GOU. (2012). State action plan on climate change. Revised Version. Uttarakhand: Author. Retrieved June 1, 2014, from http://www.uttarakhandforest.org/Data/SC_Revised_UAPCC_27june12.pdf

- Goulden, M., Naess, L.O., Vincent, K., & Adger, W.N. (2009). Accessing diversification, networks and traditional resource management as adaptations to climate extremes. In W.N. Adger, I. Lorenzoni, & K.L. O'Brien (Eds.), Adapting to climate change: Thresholds, values, governance (pp. 448–464). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hunzai, K., Gerlitz, J., & Hoermann, B. (2011). The specificity of mountain poverty: Regional analysis of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal and Pakistan. Kathmandu: ICIMOD.

- ICIMOD. (2009). Local responses to too much and too little water in the greater Himalayan region. Kathmandu: Author.

- IPCC. (2012). Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. Special report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Retrieved September 29, 2014, from http://www.ipcc-wg2.gov/SREX/images/uploads/SREX-All_FINAL.pdf

- IPCC. (2014a). Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report. Summary for Policy Makers. Retrieved June 1, 2014, from http://ipcc-wg2.gov/AR5/images/uploads/IPCC_WG2AR5_SPM_Approved.pdf

- IPCC. (2014b). Livelihoods and poverty. Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the IPCC 5th Assessment Report. Chapter 13. Final Draft. Retrieved May 23, 2014, from http://ipcc-wg2.gov/AR5/images/uploads/WGIIAR5-Chap13_FGDall.pdf

- IPCC. (2014c). Asia. Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the IPCC 5th Assessment Report. Chapter 24. Final Draft. Retrieved June 1, 2014, from http://ipcc-wg2.gov/AR5/images/uploads/WGIIAR5-Chap24_FGDall.pdf

- Jain, A. (2010). Labour migration and remittances in Uttarakhand. Kathmandu: ICIMOD.

- Jodha, N.S. (1997). Mountain agriculture. In B. Messerli & J.D. Ives (Eds.), Mountains of the world: A global priority (pp. 313–336). New York: The Parthenon Publishing Group.

- Joshi, A.K., & Joshi, P.K. (2011). A rapid inventory of indicators of climate change in the middle Himalaya. Current Science, 100(6), 83–833.

- Kelkar, U., Narula, K.K., Sharma, V.P., & Chandna, U. (2008). Vulnerability and adaptation to climate variability and water stress in Uttarakhand State, India. Global Environmental Change, 18, 564–574. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.09.003

- Körner, C.H., Ohsawa, M., Spehn, E., Berge, E., Bugmann, H., Groombridge, B., … Watanabe, T. (2005). Mountain systems. In R. Hassan, R. Scholes, & N. Ash (Eds.), Millennium ecosystem assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being: Current state and trends (Vol. 1, pp. 681–716). Washington, DC: Island Press.

- LAPA/MOE. (2012). National framework on Local Adaptation Plan for Action. Kathmandu: Ministry of Environment, Government of Nepal.

- Leduc, B. (2011). Mainstreaming gender in mountain development – from policy to practice. Kathmandu: ICIMOD.

- Macchi, M. (2011). Framework for community-based climate vulnerability and capacity assessment in mountain areas. Kathmandu: ICIMOD.

- Macchi, M., & ICIMOD Team. (2010). Mountains of the world – ecosystem services in a time of global and climate change. Kathmandu: ICIMOD.

- NAPA/MOE. (2010). National Adaptation Programme of Action to climate change. Kathmandu: Ministry of Environment, Government of Nepal.

- Nogues-Bravo, D., Araujo, M.B., Errea, M.P., & Martinez-Rica, J.P. (2007). Exposure of global mountain systems to climate warming during the 21st century. Global Environmental Change, 17, 420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.11.007

- O'Brien, K., & Leichenko, R.M. (2000). Double exposure: Assessing the impacts of climate change within the context of economic globalization. Global Environmental Change, 10, 221–232. doi: 10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00021-2

- Orlove, B., Roncoli, C., Kabugo, M., & Majugu, A. (2010). Indigenous climate knowledge in southern Uganda: The multiple components of a dynamic regional system. Climatic Change, 100, 243–265. doi: 10.1007/s10584-009-9586-2

- RSAS. (2002). The Abisko agenda: Research for mountain area development (Ambio Special Report 11). Stockholm: Author.

- Shrestha, A.B., & Aryal, R. (2010). Climate change in Nepal and its impact on Himalayan glaciers. Regional Environmental Change, 11(1), 65–77. doi:10.1007/s10113-010-0174-9

- Singh, S.P., Bassignana-Khadka, I., Karky, B.S., & Sharma, E. (2011). Climate change in the Hindu–Kush Himalayas: The state of current knowledge. Kathmandu: ICIMOD.

- Thomas, D.S.G., Twyman, C., Osbahr, H., & Hewitson, B. (2007). Adaptation to climate change and variability: Farmer responses to intra-seasonal precipitation trends in South Africa. Climatic Change, 83, 301–322. doi: 10.1007/s10584-006-9205-4

- Tiwari, K.R., Balla, M.K., Pokharel, R.K., & Rayamajhi, S. (2012). Climate change impact, adaptation practices and policy in Nepal Himalaya. Helsinki: United Nations University, UNU-Wider.

- Vedwan, N., & Rhoades, R. (2001). Climate change in the western Himalayas of India: A study of local perception and response. Climate Research, 19, 109–117. doi: 10.3354/cr019109

- Watt, R. (2012). Linking national and local adaptation planning: Lessons from Nepal. Case study 3, The Learning Hub. Brighton: IDS.

- World Bank, & DFID. (2006). Unequal citizens. Gender, caste and ethnic exclusion in Nepal. Summary. Kathmandu: Author.

- Xu, J., Grumbine, R.E., Shrestha, A., Eriksson, M., Yang, X., Wang, Y., & Wilkes, A. (2009). The melting Himalayas: Cascading effects of climate change on water, biodiversity and livelihoods. Conservation Biology, 24, 520–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01237.x