Abstract

In the wake of the Paris climate conference which inscribes loss and damage as a permanent feature of the global climate regime, this paper examines the relevance of the global Loss and Damage agenda for national climate change policies. Through a structured review of the emerging policy and academic literature two primary challenges are highlighted: first, the difficulty in establishing formal attribution of loss and damage to anthropogenic climate change, and second in determining with clarity the limits to adaptation beyond which loss and damage can be described as unavoidable. In examining these two challenges, we arrive at a framework for national level policy that emphasises the underlying developmental potential of Loss and Damage. In offering this viewpoint, the narrative arc on Loss and Damage is expanded from a technical agenda towards one more attuned to existing policy and mechanisms at the local and national levels. A Comprehensive Risk Management approach is proposed as a practical framing for national and local policies to address loss and damage which could lead to addressing both the underlying and accumulating development failures and risk management capacities that shape loss and damage outcomes. This moves Loss and Damage from a reactive to a proactive responsibility and enables action now – not only once attribution and the limits to adaptation are derived.

1. Introduction

At COP 21 in Paris Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) agreed to “pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C” (UNFCCC, Citation2016, p. 22). However, the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) in which Parties communicate how they intend to contribute to the global temperature goal do not translate into a below 2°C world, let alone to efforts to reduce warming to 1.5°C – but rather to global average warming in the magnitude of 2.7°C by 2100 (UNFCCC, Citation2015). The IPCC has warned that failure to make “substantial and sustained” reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will increase the likelihood of severe and irreversible impacts (IPCC, Citation2014, p. 8) and consequent loss and damage. To minimize losses and damages to the extent possible will require the world’s largest emitters to ratchet up ambition beyond what is communicated in the INDCs, now known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Paris in that sense is the beginning, not the end of the collective effort to fight climate change. That said, while mitigation remains of paramount importance to limit future climate change, the fact remains that losses and damages will occur despite both mitigation and adaptation efforts (Klein et al., Citation2014).

The Paris Agreement has established loss and damage as a permanent feature of the global climate regime, which should open up space for, encourage and legitimise research on loss and damage. The term “loss and damage” in the context of climate change has its origins in the international climate negotiations under the UNFCCC. At the global level, loss and damage is often conceptualised as the impacts of climate change that are not avoided through mitigation and adaptation efforts (Roberts & Huq, Citation2015; Verheyen, Citation2012). This argument has underpinned calls for greater mitigation ambition, increased funding for adaptation as well as the establishment of Loss and Damage as a third pillar under the UNFCCC (Huq, Roberts, & Fenton, Citation2013; Kreft, Warner, Harmeling, & Roberts, Citation2013; Roberts & Huq, Citation2013). At the local level, loss and damage has been defined as the impacts of climate change that households and communities are not able to adapt to Warner et al. (Citation2012, Citation2013a). Verheyen (Citation2012) refers to the climate change impacts that can be avoided through mitigation and adaptation efforts as avoided loss and damage, those resulting from insufficient mitigation and adaptation efforts as unavoided avoidable loss and damage and those impacts that cannot be avoided as unavoidable loss and damage. For the purposes of this paper, “loss and damage” will be used to refer to actual or potential losses and damages incurred on the ground, whereas “Loss and Damage” will be used to refer to the loss and damage policy agenda.

The idea that climate change would eventually lead to losses and damages has been part of the global climate change agenda since before the UNFCCC was established (INC, Citation1991). Rising focus on loss and damage in negotiations under the UNFCCC has been underpinned by increasingly severe predictions of the magnitude and frequency of future climate change impacts barring significant emission cuts, coupled with the reality that climate change impacts are already yielding losses and damages throughout the world (Roberts & Huq, Citation2015; Warner & Zakieldeen, Citation2012). The Loss and Damage agenda has heightened discussions on historical responsibility, liability and compensation and as such is highly political. Media coverage of loss and damage has tended to focus disproportionately on these issues. However, as Hoffmaister, Talakai, Damptey, and Barbosa (Citation2014) argued in the wake of the establishment of the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts at the 19th Conference of the Parties (COP) loss and damage is about much more than compensation. Developing countries are also grappling with the challenges of addressing the impacts of climate change in the medium and long term including the loss of livelihoods and biodiversity, permanent and non-economic losses, migration and displacement and for some the loss of statehood (Hoffmaister, Talakai, Damptey, & Barbosa, Citation2014).

Loss and Damage is a materialisation of pre-existing risk and stands out from established climate change discourse and policy by recognising social (vulnerability and adaptation) and physical (hazard) pathways for action. The Paris Agreement suggests that enhanced understanding, action and support is needed in several areas related to addressing loss and damage, including comprehensive risk assessment and building the resilience of communities, livelihoods and ecosystems (UNFCCC, Citation2016). The IPCC in its Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation (SREX) shows that tools able to reduce or eliminate chronic risk can limit cumulative loss and damage and build resilience (Lavell et al., Citation2012). This positioning of Loss and Damage creates space to move beyond climate change determinism in policy and practice towards a comprehensive, development-centred paradigm for risk management. This paper will posit that a Comprehensive Risk Management Framework with development as its foundation and which addresses the root causes of vulnerability can contribute significantly to the resilience of communities, livelihoods and ecosystems. However, to implement comprehensive risk management approaches to avoid, minimise and address loss and damage national policy and decision-makers will need to better understand what loss and damage means for national policy and planning processes. This paper will unpack some of the key issues that will need to be considered by national actors as they develop and implement policies to avoid, minimise and address loss and damage. To do so, three tenets of the dynamic and evolving loss and damage agenda will be explored: attribution, the limits to adaptation and options for practical action.

2. Value and challenges of attributing loss and damage to anthropogenic climate change

Loss and damage results from a spectrum of weather events and climatic processes, from discrete events (referred to as “extreme events”) to those that result from slow onset processes that unfold and increase in magnitude over a long period of time (UNFCCC, Citation2012). Although the UNFCCC uses the term “loss and damage associated with climate change impacts”, the fact that it defines loss and damage as arising from both extreme events and slow onset processes naturally leads to the question of how loss and damage can be attributed to anthropogenic climate change. However, as James et al. (Citation2014) note the question of attributing loss and damage to anthropogenic climate change has been largely sidelined in the loss and damage negotiations.

The first issue when discussing attribution is the distinction between weather and climate. In the past, this distinction has been described as “climate is what you expect, weather is what you get” but Allen (Citation2003, p. 891) argues that in the twenty-first century, it is more often the case that “the climate is what you affect, the weather is what gets you”. While weather can be observed it is impossible to be certain of the exact nature of the climate or how it is changing (Allen, Citation2003). In order to determine whether or not human activity has affected the climate, it is first necessary to understand what the climate would have been without anthropogenic GHG emissions.

There are two levels of attribution when considering if loss and damage is the result of human interference with the climate system. The first is to attribute an individual weather event or climatic process to anthropogenic GHG emissions. The second is to attribute specific loss and damage impacts given a number of other potential intervening drivers. Most research to date has focused on the first question though there is emerging research focused on attributing observed impacts (see James et al., Citation2014). There is robust evidence linking slow onset processes such as increasing temperatures, sea level rise and glacial retreat to anthropogenic climate change (see Bindoff et al., Citation2013). However, other slow onset processes like salinisation and loss of biodiversity are influenced by a number of both anthropogenic and non-anthropogenic factors, making attribution more difficult to establish. Attributing extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, droughts and floods, is even more complex as natural variability plays a greater role (Parker et al., Citation2016).

It may never be possible to determine the extent to which anthropogenic forcing contributes to a given weather event (Allen, Citation2003). However, it is possible to determine the extent to which anthropogenic forcing increases the likelihood of a given weather event. Pall et al. (Citation2011) developed a framework for probabilistic event attribution whereby they evaluated the extent to which anthropogenic GHG emissions increased the flood risk in England and Wales in the fall of 2000 (very likely greater than 20% and likely greater than 90%). However, the study analysed only hydrometeorological factors and conditions and did not account for other factors that could have contributed to the increased risk, such as the built environment (Pall et al. Citation2011). In another study, Stone and Allen (Citation2005) used a fractional attributable risk framework to determine that the European heat wave of the summer of 2003 was made twice as likely because of anthropogenic forcing. In a related study, Stott, Stone, and Allen (Citation2004) found that anthropogenic forcing was responsible for 75% of the increased risk of the 2003 European heat wave.

Although attribution science is evolving (see James et al., Citation2014), attributing climate change to anthropogenic causes remains challenging (Hegerl, Zwiers, & Tebaldi, Citation2011). There are a number of challenges associated with observing changes in extreme events, including the availability and quality of data, which vary by event and by region (Seneviratne et al., Citation2012). For example, there are significant gaps in data management, monitoring climate parameters, developing climate scenarios and assessing the impacts of climate change in most African countries (Niang et al., Citation2014). Even when there are sufficient data it can be difficult to determine when a weather event begins and ends (Allen et al., Citation2007). In addition, extreme weather and changes in extreme weather have complex causes (Allen et al., Citation2007; Hegerl, Zwiers, & Tebaldi, Citation2011; Hulme, Citation2014) which will need to be better understood to enhance the robustness of climate models used in attribution studies (Anon, 2012 in Hulme, Citation2014). Attribution studies have also been critiqued because they fail to acknowledge the political, social and economic context in which an event takes place (Hulme, Citation2014). Indeed, a range of factors contribute to loss and damage including – but not limited to – poverty levels (Allen et al., Citation2007).

Understanding how anthropogenic factors have contributed to a weather event or climatic process could help decision-makers implement policies and actions to reduce the likelihood of an extreme event happening in the future (Stone & Allen, Citation2005; Stott et al., Citation2010). Attribution studies can also therefore enhance understanding of how loss and damage occurs. If anthropogenic climate change is only partly responsible for local loss and damage from a weather event or climatic process, then efforts should be made to understand and address the other contributing factors. However, in order for appropriate policies to be implemented the uncertainties and probabilities of attribution studies would need to be properly communicated and decision-makers would need to be able to understand and respond to the information provided (Parker et al., Citation2016).

Although it will likely be a long time before courts accept attribution studies as a basis for awarding compensation (Hulme, Citation2014), in the future attribution could help states and other actors seek financial support for the cost of adjusting to cope with the impacts of climate change. For example, the Government of Kiribati recently purchased 20 km2 of land on Vanua Levu, Fiji’s second largest island at a cost of 8.77 million USD (Caramel, Citation2014). Relocation of its entire citizenry to the newly purchased territory – located 2000 km away from Kiribati – will be an expensive undertaking that the Government of Kiribati will not be able to bear on its own. Establishing attribution with the aim of seeking resources to cope with the impacts of individual extreme events will be even more difficult. Given the difficulty of attributing increased intensity of tropical cyclone activity to anthropogenic GHG emissions (Bindoff et al., Citation2013), countries like the Philippines would have a much more difficult time seeking compensation for events like the super-storm Haiyan of 2013.

While attribution has a role to play in Loss and Damage, it should not be a pre-requisite for global action to help developing countries address loss and damage. Hulme, O'Neil, and Dessai (Citation2011) argue that the international community has an ethical obligation to help build resilience and institutional capacity to address weather-related risks. Rather than investing in measures to address loss and damage that can be attributed to climate change, support should be given to those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change – be they attributable to anthropogenic factors or not (Hulme, Citation2013). In addition, while finding ways and means of addressing the long-term impacts of climate change such as loss of statehood migration, displacement remains critical, focus on compensation can divert attention away from some of the key issues facing policy-makers in developing countries today (Hoffmaister et al., Citation2014). These include – among other things – exploring, developing and implementing a range of tools to avoid, minimise and address loss and damage within comprehensive risk management frameworks (Roberts, van der Geest, Warner, & Andrei, Citation2014; Roberts & Huq, Citation2013; Warner, van der Geest, & Kreft, Citation2013a).

3. Understanding the limits of adaptation

Loss and Damage is often associated with the limits to adaptation. Research on loss and damage at the local level found that in many cases, the impacts of climate change overwhelmed the capacity of households to cope and adapt (Warner & van der Geest, Citation2013). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report maintains that the limits to adaptation occur when a society is no longer able to meet its objectives, secure its values (Klein et al., Citation2014) and avoid intolerable risk (Agard et al., Citation2014) through adaptation. Intolerable risk are threats to core social objectives such as health, welfare, security and sustainability which cannot be avoided through adaptation (Dow et al., Citation2013; Klein et al., Citation2014; Klinke & Renn, Citation2002). Determination of whether or not a risk is acceptable, tolerable or intolerable depends on the viewpoint of the actor making that decision (Dow et al., Citation2013; O’Brien, Citation2012). The limits of adaptation are therefore influenced by how stakeholders perceive risk, define the problem and implement solutions (Moser & Ekstrom, Citation2010) which are, in turn, influenced by the values of those in power (Adger et al., Citation2009). Strategies considered successful for some may not be seen the same way by others, and may, in fact, impose additional and locally unacceptable loss and damage (O’Brien, Citation2009). This is not only a question of identifying an appropriate level of compensation to offset losers from loss and damage but opens up questions about the value frameworks that make sense of knowledge and observations to describe what is gained, maintained or lost through adaptation as adaptation meets its multiple limits.

Even within specific value systems, the limits of adaptation are multiple. The IPCC differentiates between hard limits, whereby, “no adaptation options are possible to avoid intolerable risk”, and soft limits, in which adaptation options exist to avoid intolerable risk but are currently not available (Agard et al., Citation2014, p. 2). Evidence of hard limits to adaptation has been documented in the coastal region of Bangladesh where rising salinity levels have rendered cultivation of even the most saline tolerant varieties of rice impossible (Rabbani, Rahman, & Mainuddin, Citation2013). Soft limits to adaptation were documented in a Kenyan study and include inadequate investment in education as a barrier to livelihood diversification in the wake of flooding, which subsequently reduced agricultural productivity (Opondo, Citation2013). Research suggests that the limits to adaptation can be deferred, and in the case of soft limits, eliminated altogether, through targeted development interventions. Moser and Ekstrom (Citation2010) identify a range of policy options for a comprehensive approach to overcoming what they refer to as the barriers to adaptation, including the development of new institutions and management frameworks and altering land-use practices. The integration of risk management outcomes with development policy is similarly championed in the emerging literature on resilience (DFID, Citation2011; Mitchell, van Aalst, & Silva Villaneuva, Citation2010; Roberts, Andrei, Huq, & Flint, Citation2015) and a revitalised sustainable development agenda (UN General Assembly, Citation2015).

When the hard limits of adaptation are reached and policy options from within a specific development pathway have been exhausted, external support will be necessary to augment the pathways and enable new adaptation options. Some have described adaptation that is associated with a change in the underlying development pathway/scope or approach as transformation (Eriksen, Inderberg, O'Brien, & Sygna, Citation2015; O’Brien, Citation2012; Pelling, Citation2011). Research on transformation is so far limited though evidence suggests that deliberative transformation (O’Brien, Citation2012) will take time and commitment, and may require considerable public and political will, including that of international development partners. This scenario places the humanitarian sector in a novel position. While this transition is underway loss and damage will continue to unfold as the limits to adaptation are more clearly expressed. The humanitarian imperative requires action but this must move from simply supporting those at risk and suffering loss to a more proactive position where humanitarian action can contribute to moving development pathways towards less risky futures. This agenda opens new questions of risk management tools. How can risk transfer, risk retention, response and reconstruction policy and practice better engage with the precepts and practices of development?

The limits to adaptation are influenced by a variety of factors. Past decisions about economic development, technology use, social norms and behaviour influence the speed at which societies the limits to adaptation are reached (Preston, Dow, & Berkhout, Citation2013) and can also facilitate or hinder transformation (Pelling, O’Brien, & Matyas, Citation2014). Poverty reduces adaptation options and hastens the rate at which the limits of adaptation are reached. However, in both developing and developed countries adaptation frontiers are determined by social, cultural and economic factors. Wealth can enable technology (infrastructural and organisational) to extend the adaptation frontier as soft limits are overcome, but can also compound risks if new investments are exposed and indirect impacts increase.

The limits to adaptation can also be a signal that adaptation itself needs to be done better. Adaptation deficits – the gap between the level of adaptation needed and that which is implemented – can result in high levels of loss and damage (Burton, Citation2009). Addressing adaptation deficits to slow the rate at which countries reach the adaptation frontier – defined as a safe operating space for adaptation beyond which intolerable risks occur (Preston et al., Citation2013) – and incur loss and damage requires both adjusting development pathways and a more concrete engagement with risk management in both developing and developed country contexts. However, national decision-makers need more information about where the limits to adaptation lie (both in time and in space) in order to develop and implement appropriate policies and actions (Huq et al., Citation2013; Warner et al., Citation2012). Empirical studies in a number of climate change and development contexts are needed to begin to develop a picture of where the limits of adaptation may lie in relation to potential adaptation and development pathways. Given finite resources and opportunity costs a delicate balance between adaptation (avoiding loss and damage) and policies that address loss and damage when the limits of adaptation have been exceeded will be needed. Policy choices that can be used to make more transparent trade-offs between investing in development, adaptation and addressing residual loss and damage will be required. This will help legitimate decisions on resource investment that have required governments to facilitate private actors or directly engage in resource transfers and interventions that benefit different social and geographically defined groups.

4. Addressing loss and damage through comprehensive risk management

The global Loss and Damage agenda is already encouraging national decision-makers to develop and implement measures that avoid, minimise and address losses and damages to weather events and climatic processes regardless of their cause. The outcome of COP 18 in Doha recommended that Parties undertake a range of actions – in the context of national and regional priorities and circumstances – from assessing the risk of loss and damage to designing and implementing country-driven risk management strategies and implementing comprehensive risk management approaches (UNFCCC, Citation2013). Developing a comprehensive approach to loss and damage does not require the wholesale invention of new approaches, rather the integration of an existing, but so far fragmented, and too often competing, set of tools. The first task for establishing a clear Loss and Damage policy agenda is to review the existing tools, which then needs to be brought together with analysis and policy proscriptions to help overcome the institutional barriers to integration. Each country will need to determine the balance of risk management approaches appropriate for its social, economic and political context, including public and political levels of risk and loss tolerance, and the type of weather events and climatic events it will need to respond to. A combination of approaches that both avoid and minimise loss and damage where possible and support those at risk in situations where loss and damage cannot be avoided will be needed (Roberts et al., Citation2014; UNFCCC, Citation2012; Warner et al., Citation2010). Warner et al. (Citation2013c) suggest a layered approach in which different types of risks are addressed by different approaches.

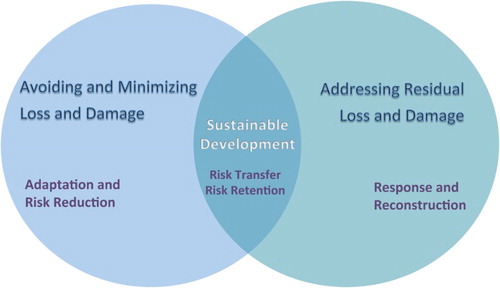

This section provides a first, general survey of those risk management tools available to national-level policy-makers that could form the basis for national, Comprehensive Risk Management Frameworks and suggests how they could be targeted to reduce vulnerability. This includes tools within and beyond the adaptation frontier. describes the range of tools that fall within the scope of a Comprehensive Risk Management Framework, and their role in avoiding, minimising and addressing residual losses and damages. Adaptation and risk reduction are integral to avoiding and minimising losses and damages and efforts to maximise their effectiveness must be integrated into comprehensive risk management frameworks. Risk transfer tools, like insurance; and risk retention measures, like social safety nets, can shift the burden of loss and damage and limit secondary and indirect effects and span a spectrum from avoiding and minimising loss and damage to cushioning the blow when losses and damages cannot be avoided. Response and reconstruction also play a critical role in addressing residual loss and damage that cannot be avoided. All these tools are important in containing the secondary and indirect losses of climate change, including lost market share or local inflationary effects arising from damaged infrastructure.

5. A comprehensive risk management framework for addressing climate change

The need to develop comprehensive risk management frameworks to avoid, minimize and address loss and damage is not novel (see UNFCCC, Citation2013). However, most responses to climate change tend not to include analyses of the root causes of vulnerability (Ribot, Citation2014). Positioning sustainable development at the centre of comprehensive risk management frameworks and ensuring that policy measures target the most vulnerable is essential to addressing the root causes of vulnerability and building resilience to limit future loss and damage to human societies. The Comprehensive Risk Management Framework is a series of tools and measures that come together to reduce vulnerability and build resilience of households at the micro-level and countries at the macro-level. The Framework builds on a foundation of sustainable development and each risk management measure implemented subsequently should aim to reduce vulnerability including through targeting interventions and increasing the participation of the most vulnerable in the development, planning and implementation of tools to address climate change.

6. Sustainable development

It is widely recognised that the impacts of climate change are not evenly distributed and that developing countries are poised to experience more losses and damages as a proportion of their income than developed countries (UNISDR, Citation2015). The paradox is that while the impacts of climate change can impede development, development plays a key role in efforts to address climate change. That said, policy-makers in developing countries are already overwhelmed with efforts to alleviate poverty, ensure a secure food supply and access to energy as well as to meet transportation needs – among other development priorities – which in many cases take priority over policies to address climate change (Halsnæs & Verhagen, Citation2007). However, loss and damage can slow economic growth, threaten food security and reinforce poverty cycles (Burton, Citation2009; Goklany, Citation2006; Oliver-Smith, Cutter, Warner, Corendea, & Yuzva, Citation2012) and thus it needs to be avoided to the extent possible in order to ensure that development can progress. Development is integral to ensuring that climate change policies and plans are successful and thus approaches to avoid, minimise and address loss and damage will need to be implemented in the broader context of achieving social and economic development (Le Blanc, Citation2009). Sustainable development policies should also be robust enough to facilitate development in a wide range of possible future climate change scenarios (Osman-Elasha, Citation2006).

Development in the context of climate change will need to transcend business as usual approaches which can exacerbate vulnerability to climate change impacts (Oliver-Smith et al., Citation2012; Schipper & Pelling, Citation2006). While facilitating economic and social development is important, reducing vulnerability is an essential component of the Comprehensive Risk Management Framework and integral to avoiding, minimising and addressing loss and damage. Without truly understanding and addressing the root causes of vulnerability resilience building efforts will also not be successful in the long term. Depending on who is vulnerable and why the Comprehensive Risk Management Framework may also include tools to address chronic issues such as poor housing and infrastructure, lack of access to education, sanitation and health services (Oliver-Smith et al., Citation2012). Most responses to climate change seek to understand who is vulnerable to climate change rather than understanding why vulnerability arises or how the conditions for vulnerability are created (Ribot, Citation2014). Ribot (Citation2014, p. 689) proposes two “causal chains” for vulnerability analysis: one to look at how access to assets is shaped and another to look at how entitlements are shaped through influence in the political economy. Empowerment plays a key role in reducing vulnerability. The most vulnerable often lack the knowledge, skills and time to engage with and influence the political economy through which their lives are shaped (Ribot, Citation2014). Loss and Damage should therefore be a clarion call for a critical revision of inequitable and unsustainable development priorities and mechanisms.

Loss and Damage should not be seen as a mechanism for gaining finance to enable risk producing development approaches to persist. Here, lies both the opportunity and risk of Loss and Damage for sustainable development. This will likely place emphasis on institutional reform to enable more holistic development policy, to support development that can integrate risk management into everyday development decision-making with a view to slowing down or reversing the accumulation of vulnerability and environmental degradation. In this way, Loss and Damage calls for a revitalisation of the originating core values of the sustainable development agenda – the coupling of human well-being and ecological integrity. It indicates the importance of integrating risk management into policies and projects aimed at transitioning to a more sustainable development from global production and consumption chains to local livelihoods. These possibilities begin to sketch out aims for transformation.

7. Avoiding and minimising loss and damage: adaptation and risk reduction

The Comprehensive Risk Management Framework suggests that targeted approaches to avoid and minimise loss and damage from climate change impacts should build on sustainable development. Like sustainable development, these tools should be aimed at reducing vulnerability.

7.1. Adaptation

Global temperatures have already risen 0.85°C relative to pre-industrial levels (4, 2015) and there is mounting evidence that historical emissions have already locked in 1.5°C warming (World Bank, Citation2014). Adaptation should therefore be a key component of comprehensive risk management frameworks and approaches to avoid and minimise loss and damage should be implemented alongside those to address loss and damage that cannot be avoided.

Adaptation actions will be more successful if they address the underlying drivers of vulnerability. This entails understanding why and how people are vulnerable to climate variability and climate change, who has experienced loss and damage and why (Burton, Huq, Lim, Pilifosova, & Schipper, Citation2002), a process already described above. Such structural vulnerability is aligned with structural poverty so that to vulnerability national adaptation strategies need to focus on poor people, not just poor countries and the interests of the two are not always aligned (Kates, Citation2000). Integrating risk reduction into adaptation could better target adaptation interventions to the most vulnerable (Schipper & Pelling, Citation2006).

Implementing adaptation strategies has costs that not all households are able to bear (Pelling, Citation2011), leaving some to implement “erosive” coping strategies – like removing children from school or selling livestock – which can impede development and exacerbate poverty (Warner et al., Citation2012, p. 65). Adaptation actions therefore need to be scaled up and better targeted to reach the most vulnerable, including women and the poor and landless (Warner et al., Citation2012). Based on the premise that women play a key role in the resilience of a household and that women themselves are more resilient when empowered CARE is supporting community-based adaptation initiatives in several communities in West Africa with established village savings and loan associations (VSLAs) (CARE, Citation2011). Participation in VSLAs empowers women and builds the resilience of the household by enabling women to purchase seeds and invest in livestock production and other income earning activities (CARE, Citation2011). While these initiatives are important, it is equally important that such initiatives engage with and empower local governments. Although interventions by non-government organisations may be successful at empowering individuals, if local governments are under-funded local representation and democracy can be undermined (Manor, 2005 in Ribot, Citation2014). This could have repercussions for reducing vulnerability and building resilience in the long term.

7.2. Risk reduction

Risk reduction is essential to sustainable development (UNISDR, Citation2015) and an integral part of the Comprehensive Risk Management Framework. Risk reduction measures are best used to reduce the risk from the impacts of extreme climatic events that are low in magnitude but occur frequently (UNFCCC, Citation2012). However, risk reduction can also be effective at avoiding loss and damage from extreme events of a high magnitude that incur infrequently. For example, early warning systems, improved cyclone forecasting and evacuation programmes, along with cyclone shelters, were credited with the much lower death toll from 2007’s Cyclone Cidr (3406) compared to the number of deaths (140,000) that resulted when a cyclone of similar magnitude hit coastal Bangladesh in 1991 (Paul, Citation2009).

If not properly planned and maintained efforts aimed at reducing risk can, in fact, increase the risk of loss and damage from future climate change impacts (White et al., Citation2004). As in adaptation an understanding of both the current and future risks and the local needs is essential. Political will is also essential to ensure that every effort is made to avoid loss and damage before it occurs. Providing relief after an event is often more politically appealing (Schipper & Pelling, Citation2006; Seck, Citation2007) than implementing policies beforehand that would help communities avoid loss and damage in the first place (Cutter et al., Citation2012).

Although there are many examples of successful risk reduction efforts, there is still a tendency in risk reduction to treat the symptoms rather than the underlying drivers of vulnerability (Schipper, Citation2009). While vulnerability and poverty are not necessarily synonymous with one another, the poor generally experience greater losses from climate change as a proportion of their income (White et al., Citation2004). That said, there is growing awareness of the importance of linking risk reduction with social protection measures to address poverty and other underlying drivers of vulnerability (O’Brien et al., Citation2012). The SREX outlined risk reduction measures which can address the underlying causes of vulnerability while reducing poverty, which include enhancing access to basic services and empowering communities to influence national decision-making processes (Lal et al., Citation2012). Community-based risk reduction approaches aimed at empowering community members to implement risk reduction approaches using existing knowledge and social structures are being increasingly employed (Reid et al., Citation2009). Increasing the participation of women and other socially marginalised groups in local disaster preparedness committees in rural Nepal has increased the understanding of these individuals of the risks they face and how to address them while making risk reduction measures more inclusive of the needs and priorities of these groups (Mercy Corps Nepal, Citation2009). These kinds of approaches help address two of the drivers of vulnerability to climate change, marginalisation and disempowerment, and in doing so can help build resilience to climate change (Cutter et al., Citation2012).

8. From avoiding and minimising to addressing loss and damage: risk retention and risk transfer

It will not be possible to avoid and minimise all losses and damages arising from the impacts of climate change and as already elucidated above, there are real limits to adaptation. Alongside broader sustainable development policies that integrate climate change and targeted policies to avoid and minimise loss and damage, developing countries will also need to implement policies that help the poorest and most vulnerable cope with and build resilience to climate change impacts and associated losses and damages that cannot be avoided. Risk retention and risk transfer measures can both avoid and minimise loss and damage and address residual impacts of climate change. In fact, sometimes the same tools – such as social safety nets – can do both.

8.1. Risk transfer

Risk transfer tools including financial insurance, microinsurance, microfinance and risk pooling transfer some of the risk of loss and damage and can reduce the financial burden of adapting to climate change. Although in the absence of intervening public policy, these tools can result in a net movement of resources away from those at risk and thus not only the costs of the premiums themselves but the opportunity costs of investing in insurance need to be taken into account in designing policies (Barnet, Barret, & Skees, Citation2008). The private sector could play a role to reduce the cost of implementing risk transfer tools through the provision of knowledge and expertise in both assessing and managing the risks of climate change including through risk modelling (Surminski & Eldrige, Citation2015).

Risk transfer tools are especially effective at addressing loss and damage from low magnitude extreme weather events that occur infrequently as it may not be possible to avoid these events in a cost-effective manner (Warner et al., Citation2013b; Warner et al., Citation2013c). Insurance can provide a cushion against climate change impacts, preventing households from spiraling further into poverty (Quereshi & Reinhard, Citation2014; Warner et al., Citation2010). However, research has shown that risk transfer should be part of a comprehensive risk management framework that includes risk reduction and cautious risk taking to minimise moral hazard dilemmas in which insurance encourages investment in places at risk (Quereshi & Reinhard, Citation2014; Warner et al., Citation2013b; Warner, Zissener, et al., Citation2010). Risk retention policies like social safety nets also play a key role. The R4 Resilience Initiative combines risk transfer, risk reduction, risk retention while incentivising risk taking to protect smallholder farmers from systemic risks such as drought in Ethiopia and Senegal (WFP and Oxfam America, Citation2014). While the project has helped reduce the vulnerability of insured farmers to drought by allowing them to invest in agricultural improvements and increase savings, research has found that significant improvements in living standards would require investments in irrigation and livelihood diversification (Oxfam America, Citation2014). Given this, there may be scope for integrating the initiative into broader development processes.

There is only so much that individual farmers and households can do to increase their resilience to climate change. At some point broader, national policies will be needed. Risk transfer tools can also be implemented at the national level to reduce the risk of loss and damage to a country. Regional risk pooling instruments can allow countries to respond more effectively in the wake of a climatic event (Lal et al., Citation2012) and in doing so can reduce human suffering and the set backs to development (Warner et al., Citation2013a). Through regional initiatives such as the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF SPC, Citation2015) and the African Risk Capacity (ARC, n.d.) donors cover the cost of premiums to member countries which receive payouts when agreed upon thresholds are exceeded. Through the Africa Risk Capacity (ARC) countries choose the level of risk they wish to insure themselves against and the corresponding premiums. In order to qualify, each country must complete a contingency plan that outlines how the payouts will be spent in order to reduce risk and build resilience to future events (ARC, n.d.). ARC offers the greatest benefit, however, when countries have a well-targeted, large-scale social safety net such as an employment guarantee scheme (Clarke & Hill, Citation2012). In order to most effectively reduce vulnerability and build resilience, approaches to address loss and damage must be integrated within comprehensive risk management frameworks that include both risk transfer, where appropriate, and risk retention policies like social safety nets.

8.2. Risk retention

The term risk retention has its origins in the insurance industry but has been increasingly used in the global climate regime in recent years. In this sense, risk retention is used to refer to a suite of measures through which an actor (usually a national government) retains the risk of climate change impacts (as opposed to transferring the risk with tools like insurance) but cushions the blow through social protection measures, contingency funds and other measures (UNFCCC, Citation2012). These tools have financial costs, but can lessen the economic burden of climate change impacts for at risk individuals and communities and can also help countries stay on track to meet development goals (UNFCCC, Citation2012).

Risk retention policies like social safety nets can be used to build resilience to the inevitable impacts of slow onset processes like sea level rise while contingency funds can offset the financial burden of extreme events that are less predictable (UNFCCC, Citation2012). Many countries have already implemented risk retention policies, which have successfully helped reduce the vulnerability of the poorest to climate change impacts (Murray et al., Citation2012). The Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP) in Ethiopia provides chronically food insecure households with up to six months of food and cash transfers per year in exchange for labour on public works projects such as building schools and roads, digging wells and constructing embankments (WFP, Citation2012). While the food and cash transfers help poor and vulnerable households meet their immediate needs, the public works projects can built the resilience of the larger community in the long term (Del Ninno, Subbaro, & Milazzo, Citation2009). Research has found that in order to effectively build resilience, risk retention policies should be implemented long before climate change impacts hit (UNFCCC, Citation2012) and targeted to ensure they meet the needs of the most vulnerable (Ahmed, Citation2007). This will require both an understanding of the potential magnitude and location of the impacts of climate change given a range of temperature scenarios as well as who will be vulnerable to said impacts and why.

9. Addressing residual loss and damage: response, recovery and reconstruction

9.1. Response, recovery and reconstruction

When other measures fail, response, recovery and reconstruction will be needed to help households and communities cope with loss and damage and contain the impacts of climate change to prevent cascading effects. Response and recovery often comes in the form of humanitarian assistance in the aftermath of extreme events, which can reduce suffering in the short term and promote rehabilitation and reconstruction in the longer term (Cutter et al., Citation2012). However, as already discussed above response can divert both national and international resources from other efforts – such as attaining development goals (see Schipper & Pelling, Citation2006). While emergency responses to extreme events have improved in developing countries, poverty reduction programmes aimed at reducing vulnerability have been slower to “take off” (Burton, Citation2009, p. 91). Prevailing vulnerability can also slow the process of recovering from loss and damage after it is incurred (Lavell et al., Citation2012). In addition, there is also a danger that when significant loss and damage is incurred and a state of emergency is declared, triggering a response, the weather event or climatic process can be blamed rather than the social conditions that created the vulnerability that led to such high levels of loss and damage (Lavell et al., Citation2012). Where resources are scarce response and reconstruction can also become a formal risk management strategy enabling the inflow of external resources that are not available for risk management pre-disaster (Pelling, Citation1998). The response to the Indian Ocean tsunami in Aceh is often cited as a positive example of response. In the wake of the tsunami there was a large amount of funding available for the response and humanitarian agencies had more staff on the ground than is normally the case with response efforts which allowed for cash transfers to be disbursed quickly (Fan, Citation2013). This empowered survivors to drive their own recovery and begin to rebuild their lives in their own way allowing them to re-gain control over their lives at a time when so much was lost (Fan, Citation2013).

After response, which ideally comes immediately after loss and damage is incurred, reconstruction will be needed to rebuild communities affected by a weather event or climatic process. Reconstruction entails repairing, rebuilding or restoring infrastructure and other assets that have been damaged while rehabilitation entails restoring the functions of public services, businesses, repairing housing or other infrastructure and returning production facilities to operation (Cutter et al., Citation2012). Unfortunately, reconstruction efforts frequently rebuild the same conditions that existed prior to the event, which replicate the same level of exposure and may create the conditions for a similar (if not greater) level of loss and damage from future climatic events (Jha, Barenstein, Phelps, Pittet, & Sena, Citation2010). In addition, reconstruction efforts that do not take into account the needs and priorities of the community can re-build houses but fail to provide homes (Petal et al., 2008 in Cutter et al., Citation2012, p. 301) and can in some cases increase vulnerability (Ingram, Franco, Rio, & Khazai, Citation2006). Viewing reconstruction as a process rather than an outcome can help ensure that vulnerability is addressed rather than focusing simply on re-building infrastructure (Cutter et al., Citation2012).

In recent years, the mantra “building back better” has gained momentum in reconstruction efforts (see Fan, Citation2013). First used to describe the response to the Indian Ocean tsunami in Aceh, building back better has more recently been described as something to aspire to as the Philippines rebuilds following the super-storm Haiyan and in the wake of the 2015 earthquake in Nepal. Building back better entails re-building infrastructure to be more climate resilient and ensuring livelihoods are re-gained and livelihood opportunities improved (UNOCHA, Citation2014). However, it could also mean reforming risk governance to improve infrastructure, enforce building codes and ensure that the poor and vulnerable have access to safe housing (Martinez-Solimán, Citation2015). The rehabilitation of livelihoods is also an important component of the recovery process and one that can reduce the risk from future climatic events (Nakagawa & Shaw, Citation2004). Response, recovery and reconstruction are the last tools to be employed in the arsenal of the Comprehensive Risk Management Framework but like the other measures should part of a process to reduce vulnerability, build resilience and in doing so, to reduce loss and damage from future climate change impacts.

10. Conclusion

Although Loss and Damage has its origins in the global climate change negotiations, it is set to have increasing meaning and value at the national policy level especially in the wake of its inclusion in the Paris Agreement as a separate article to adaptation. This increasing legitimisation and recognition of loss and damage will ideally also open up space for funding empirical research to better understand what loss and damage means for national policy processes. Conceptually and programmatically much of the scope for developing policies to address loss and damage can draw from existing tools and frameworks as discussed above. But Loss and Damage provides a new and potentially considerable motivation for reducing and responding to risk and loss, and it reflects the reality that environmental hazards are increasingly being associated with anthropogenic climate change by the public, in policy discourse and also by science.

Loss and Damage as presented reinforces existing and long-standing calls from the disaster risk reduction community for holistic approaches to addressing climate change. A response is offered that highlights the importance of increasing mitigation ambition and funding for adaptation at the global level and developing and implementing comprehensive risk management frameworks to avoid, minimise and address loss and damage at the national and sub-national levels. Loss and Damage highlights the importance of adaptation as a tool for avoiding loss and damage but also draws attention to the fact that there are limits to adaptation. To translate the global Loss and Damage agenda for national policy processes will require a better understanding of the limits to adaptation and how the adaptation frontier can be extended. Loss and Damage also provides momentum for development-centred framings for risk management. Waiting for formal attribution is not realistic and while risk is driven by increasing vulnerability and exposure rooted in development processes it is development that must also be a site for adjustment – and potentially for transformation – if loss and damages are to be managed. A development-centred approach similarly responds to the knowledge that loss and damage will arise once the limits of adaptation capacity are reached. Enhancing development could defer the limits of adaptation

While addressing climate change through the development and implementation of comprehensive risk management frameworks is not novel, a focus on reducing vulnerability, centred on sustainable development is a new way of framing the response to Loss and Damage. The Comprehensive Risk Management Framework will need to begin with a robust understanding of who is vulnerable and especially why. Development interventions will need to be targeted to the most vulnerable. Tools to address specific climate change impacts while targeting the most vulnerable should then be layered on top of Comprehensive Risk Management Frameworks. Adaptation and risk reduction tools should be designed for Non-government organisations should work closely with and strengthen local government to ensure that local representation and democracy are stable and support empowerment of the most vulnerable. There are limits to what can be achieved through adaptation and risk retention but there are some approaches that span the spectrum between avoiding and minimising and addressing the residual impacts of climate change. Risk retention approaches like social safety nets will be needed country-wide to prevent the poor and most vulnerable from spiraling further into poverty and are especially effective at addressing slow onset processes of climate change. Risk transfer approaches, like insurance products, can be used to avoid and minimise loss and damage from extreme events that occur infrequently but must be combined with other tools like social safety nets and incentivised risk taking behaviour to effectively build resilience. When losses and damages cannot be avoided and rebuilding and reconstruction are necessary efforts must be made not to rebuild the same conditions as before the onset of an extreme weather event or climatic process. Involving the affected households and communities is one way to ensure that the needs of the most vulnerable are met in these processes. Finally, national governments will also need to consider what the impacts of climate change will mean for patterns of migration and displacement. While outside of the purview of this paper it would remiss not to mention.

The Comprehensive Risk Management approach proposed here is one potential response to the call for a development-centred approach for avoiding, minimising and addressing loss and damage. This opens scope that goes far beyond an administrative and legal mandate for recording and accounting climate change associated loss and damage to feed into international frameworks for compensation – important though this is. Within the proposed Framework, Loss and Damage can strengthen fundamental arguments within risk management, for addressing the root causes of risk, for greater involvement of science and technology and for national frameworks to support development-centered risk management. These agendas were established in the Hyogo Framework for Action, 2005–2015, and have been strengthened in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. A Comprehensive Risk Management Approach that can link loss and damage to risk reduction and development and be a motivation for joined up programming can also help to bridge between the Sendai Framework and the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) agenda, showing how existing risk management and response mechanisms can also reduce risk and support development pathways to be more resilient. However, it is clear that sustainable development policies will need to transcend business as usual to ensure that the conditions that give rise to vulnerability are addressed to avoid loss and damage amongst the vulnerable and poor and build resilience where losses and damages cannot be avoided.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments as well as Koko Warner and Helen Adams for their insightful feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adger, W. N., Dessai, S., Goulden, M., Hulme, M., Lorezoni, I., Nelson, D. R., … Wreford, A. (2009). Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Climatic Change, 93, 335–354. doi: 10.1007/s10584-008-9520-z

- African Risk Capacity. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.africanriskcapacity.org/documents/350251/371107/ARC_Overview_Brief_EN.pdf

- Agard, J., Schipper, L., Birkmann, J., Campos, M., Dubeux, C., Nojiri, Y., … St. Clair, A. (2014). WGII AR5 glossary. In C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, … L. L. White (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 1757–1776). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Ahmed, S. S. (2007). Social safety nets in Bangladesh. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/BANGLADESHEXTN/Resources/295759-1240185591585/BangladeshSocialSafetyNets.pdf

- Allen, M. (2003). Liability for climate change: Will it ever be possible to sue anyone for damaging the climate? Nature, 421, 891–892. doi: 10.1038/421891a

- Allen, M., Pall, P., Stone, D., Stott, P., Frame, D., Min, S.-K., … Yukimoto, S. (2007). Scientific challenges in the attribution of harm to human influence on climate. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 155(6), 1353–1400.

- Barnett, B. J., Barrett, C. B., & Skees, J. (2008). Poverty traps and index-based risk transfer products. World Development, 36(10), 1766–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.10.016

- Bindoff, N. L., Stott, P. A., AchutaRao, K. M., Allen, M. R., Gillett, N., Gutzler, D., … Zhang, X. (2013). Detection and attribution of climate change: From global to regional. In T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. … P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 867–952). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Burton, I. (2009). Climate change and the adaptation deficit. In E. L. Schipper, & I. Burton (Eds.), The Earthscan reader on adaptation to climate change (pp. 89–95). London: Earthscan.

- Burton, I., Huq, S., Lim, B., Pilifosova, O., & Schipper, E. L. (2002). From impact assessment to adaptation priorities: The shaping of adaptation policies. Climate Policy, 1, 45–149.

- Caramel, L. (2014, July 1). Besieged by the rising tides of climate change, Kiribati buys land in Fiji The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jul/01/kiribati-climate-change-fiji-vanua-levu

- CARE. (2011). The resilience champions: When women contribute to the resilience of communities in the Sahel through savings and community-based adaptation. Retrieved from http://www.care-international.org/files/files/Rapport_Resilience_Sahel.pdf

- CCRIF SPC. (2015). Understanding CCRIF: A collection of questions and answers. Retrieved from http://www.ccrif.org/sites/default/files/publications/Understanding_CCRIF_March_2015.pdf

- Clarke, D. J., & Hill, R. V. (2012). Cost-benefit analysis of the African risk capacity facility. Retrieved from http://www.foodsecurityportal.org/sites/default/files/arc_cost_benefit_analysis_clarke_hill.pdf

- Cutter, S., Osman-Elasha, B., Camptell, J., Cheong, S-M., McCormick, S., Pulwarty, R., … Ziervogel, G. (2012). Managing the risks from climate change at the local level. In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, … P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (pp. 291–338). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Del Ninno, C., Subbaro, K., & Milazzo, A. (2009). How to make public works work: A review of the experiences. SP Discussion Paper No. 0905. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/SOCIALPROTECTION/Resources/SP-Discussion-papers/Safety-Nets-DP/0905.pdf

- DFID. (2011). Defining disaster resilience: A DFID approach paper. London: Author.

- Dow, K., Berkhout, F., Preston, B. L., Klein, R. J. T., Midgley, G., & Shaw, M. R. (2013). Commentary: Limits to adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 3, 305–307. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1847

- Eriksen, S., Inderberg, T. H., O'Brien, K., & Sygna, L. (2015). Introduction: Development as usual is not enough. In T. H. Inderberg, S. Eriksen, K. O'Brien & L. Sygna (Eds.), Climate change adaptation and development: Transforming paradigms and practices (pp. 1–18). London and New York: Routledge.

- Fan, L. (2013). Disaster as opportunity? Building back better in Aceh, Myanmar and Haiti, HPG Working Paper. London: Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8693.pdf

- Goklany, I. M. (2006). Integrated strategies to reduce vulnerability and advance adaptation, mitigation, and sustainable development. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 12(5), 755–786. doi: 10.1007/s11027-007-9098-1

- Halsnæs, K., & Verhagen, J. (2007). Development based climate change adaptation and mitigation—Conceptual issues and lessons learned in studies in developing countries. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 12(5), 665–684. doi: 10.1007/s11027-007-9093-6

- Hegerl, G., Zwiers, F., & Tebaldi, C. (2011). Patterns of change: Whose fingerprint is seen in global warming. Environmental Research Letters, 6(4), 1–6. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/044025

- Hoffmaister, J. P., Talakai, M., Damptey, P., & Barbosa, A. S. (2014). Warsaw International Mechanism for loss and damage. Loss and Damage in Vulnerable Countries Initiative. Retrieved from http://www.lossanddamage.net/4950

- Hulme, M. (2013). Can (and Should) “Loss and Damage” be attributed to climate change. Retrieved from http://www.fletcherforum.org/2013/02/27/hulme/

- Hulme, M. (2014). Attributing weather extremes to ‘climate change’: A review. Progress in Physical Geography, 38(4), 499–511. doi: 10.1177/0309133314538644

- Hulme, M., O’Neil, S. J., & Dessai, S. (2011). Is weather event attribution necessary for adaptation funding? Science, 334, 764–765. doi: 10.1126/science.1211740

- Huq, S., Roberts, E., & Fenton, A. (2013). Commentary: Loss and damage. Nature Climate Change, 3 (November), 947–949. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2026

- INC. (1991). Vanuatu: Draft annex relating to article 23 (Insurance) for INcludion in the revised single text on elements relating to mechanisms, A/AC.237/WGII/Misc.13.

- Ingram, J., Franco, G., Rio, C. R., & Khazai, B. (2006). Post-disaster recovery dilemmas: Challenges in balancing short-term and long-term needs for vulnerability reduction. Environmental Science and Policy, 9(7–8), 607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2006.07.006

- IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Core Writing Team: R.K. Pauchauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Geneva: Author.

- James, R., Otto, F., Parker, H., Boyd, E., Cornforth, R., Mitchell, D., & Allen, M. (2014). Characterizing loss and damage from climate change. Nature Climate Change, 4, 938–939. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2411

- Jha, A. K., Barenstein, J. D., Phelps, P. M., Pittet, D., & Sena, S. (2010). Safer homes, stronger communities: A handbook for reconstructing after natural disasters. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Kates, R. (2000). Cautionary tales: Adaptation and the global poor. Climatic Change, 45(1), 5–17. doi: 10.1023/A:1005672413880

- Klein, R. J. T., Midgley, G. F., Preston, B. L., Alam, M., Berkhout, F. G. H., Dow, K., & Shaw, M. R. (2014). Adaptation opportunities, constraints, and limits. In C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, … L. L. White (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 899–943). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Klinke, A., & Renn, O. (2002). A new approach to risk evaluation and management: Risk-based, precaution-based, and discourse-based strategies. Risk Analysis, 22(6), 1071–1094. doi: 10.1111/1539-6924.00274

- Kreft, S., Warner, K., Harmeling, S., & Roberts, E. (2013). Framing the loss and damage debate: A conversation starter by the loss and damage in vulnerable countries initiative. In O. C. Ruppel, C. Roschmann, & K. Ruppel-Schlichting (Eds.), Climate change: International law and global governance, Volume II: Policy, diplomacy and governance in a changing environment (pp. 829–842). Munich: Novos.

- Lal, P. N., Mitchell, T., Aldunce, P., Auld, H., Mechler, R., Miyan, A., … Zakaria, S. (2012). National systems for managing the risks from climate extremes and disasters. In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, … P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (pp. 339–392). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Lavell, A., Oppenheimer, M., Diop, C., Hess, J., Lempert, R., Li, J., … Myeong, S. (2012). Climate change: new dimensions in disaster risk, exposure, vulnerability, and resilience. In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, … P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (pp. 25–64). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Le Blanc, D. (2009). Climate change and sustainable development revisited: Implementation challenges. Natural Resources Forum, 33, 259–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-8947.2009.01250.x

- Martinez-Solimán, M. (2015). Building back better in Nepal (15 May 2015). Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2015/5/15/Building-back-better-in-Nepal.html

- Mercy Corps Nepal. (2009). Community-based disaster risk reduction good practice: Kailali disaster risk reduction initiatives. Kathmandu: Author. Retrieved from http://www.preventionweb.net/files/10479_10479CommunityBasedDRRGoodPracticeR.pdf

- Mitchell, T., van Aalst, M., & Silva Villaneuva, P. (2010). Assessing progress on integrating disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation in development processes. Strengthening Climate Resilience Discussion Paper No. 2. Brighton: Institute for Development Studies. Retrieved from http://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/123456789/2511#.VzhOBmPlEqQ

- Moser, S. C., & Ekstrom, J. A. (2010). A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(51), 22026–22031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007887107

- Murray, V., McBean, G., Bhatt, M., Borsch, S., Cheong, T. S., Erian, W. F., … Suarez, A. G. (2012). Case studies. In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, … P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (pp. 487–544). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Nakagawa, Y., & Shaw, R. (2004). Social capital: A missing link to disaster recovery. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 22(1), 5–34.

- Niang, I., Ruppel, O. C., Abdrabo, M. A., Essel, A., Lennard, C., Padgham, J., & Urquhart, P. (2014). Africa. In V. R. Barros, C. B. Field, D. J. Dokken, M. D. Mastrandrea, K. J. Mach, T. E. Bilir, … L. L. White (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part B: Regional aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 199–1265). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- O’Brien, K. (2009). Do values subjectively define the limits to climate change adaptation? In W. N. Adger, I. Lorenzoni, & K. L. O’Brien (Eds.), Adapting to climate change: Thresholds, values, governance (pp. 164–180). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- O’Brien, K. (2012). Global environmental change II: From adaptation to deliberate transformation. Progress in Human Geography, 36(5), 667–676. doi: 10.1177/0309132511425767

- O’Brien, K., Pelling, M., Patwardhan, A., Hallegatte, S., Maskrey, A., Oki, T., … Yanda, P. Z. (2012). Toward a sustainable and resilient future. In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, … P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (pp. 437–486). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Oliver-Smith, A., Cutter, S. L., Warner, K., Corendea, C., & Yuzva, K. (2012). Addressing loss and damage in the context of social vulnerability and resilience policy, Brief No. 7. Bonn: United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security. Retrieved from http://www.ehs.unu.edu/file/get/10570.pdf

- Opondo, D. O. (2013). Erosive coping after the 2011 floods in Kenya. International Journal of Global Warming, 5(4), 452–466. doi: 10.1504/IJGW.2013.057285

- Osman-Elasha, B. (2006). Project AF14: Assessments of impacts and adaptations to climate change. Environmental strategies to increase human resilience to climate change: Lessons for Eastern and Northern Africa, Final Report. Washington, DC: International START Secretariat.

- Oxfam America. (2014). Oxfam evaluation summary February 2014: Managing risks to agricultural livelihoods: Impact evaluation of the HARITA Project in Ethiopia (2009–2012). Retrieved from http://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/managing-risks-to-agricultural-livelihoods-impact-evaluation-of-the-harita-program-in-tigray-ethiopia-20092012/

- Pall, P., Aina, T., Stone, D. A., Stott, P. A., Nozawa, T., Hilberts, A. G. J., … Allen, M. R. (2011). Anthropogenic greenhouse gas contribution to UK autumn flood risk. Nature, 470, 382–385. doi: 10.1038/nature09762

- Parker, H., Boyd, E., Cornforth, R. J., James, R., Otto, F. E. L., & Allen, M. R. (2016). Stakeholder perceptions of event attribution in the loss and damage debate. Climate Policy. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2015.1124750

- Paul, B. K. (2009). Why relatively fewer people died? The case of Bangladesh’s Cyclone Sidr. Natural Hazards, 50, 289–304. doi: 10.1007/s11069-008-9340-5

- Pelling, M. (1998). Participation, social capital and vulnerability to urban flooding in Guyana. Journal of International Development, 10(4), 469–486. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1328(199806)10:4<469::AID-JID539>3.0.CO;2-4

- Pelling, M. (2011). Adaptation to climate change: From resilience to transformation. London and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Pelling, M., O’Brien, K., & Matyas, D. (2014). Adaptation and transformation. Climatic Change, 128(1–2). doi: 10.1007/s10584-014-1303-0

- Preston, B. L., Dow, K., & Berkhout, F. (2013). The climate adaptation frontier. Sustainability, 5, 1011–1035. doi: 10.3390/su5031011

- Quereshi, Z., & Reinhard, D. (Eds.). (2014). Microinsurance learning sessions 2014: New opportunities in a growing market. Munich: Munich Re Foundation.

- Rabbani, G., Rahman, A., & Mainuddin, K. (2013). Salinity-induced loss and damage to farming households in coastal Bangladesh. International Journal of Global Warming, 5(4), 400–415. doi: 10.1504/IJGW.2013.057284

- Reid, H., Alam, M., Berger, R., Cannon, T., Huq, S., & Milligan, A. (2009). Community based adaptation to climate change: An overview. Participatory Learning and Action, 60, 11–38.

- Ribot, J. (2014). Cause and response: Vulnerability and climate in the Anthropocene. Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(5), 667–705. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.694911 doi: 10.1080/03066150.2014.894911

- Roberts, E., Andrei, S., Huq, S., & Flint, L. (2015). Resilience synergies in the post-2015 development agenda. Nature Climate Change, 5, 1024–1025. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2776

- Roberts, E., van der Geest, K., Warner, K., & Andrei, S. (2014). Loss and damage: When adaptation is not enough. Environmental Development, 11, 219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2014.05.001

- Roberts, E., & Huq, S. (2013). Loss and damage: From the global to the local, IIED Policy Brief. Retrieved from http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17175IIED.pdf

- Roberts, E., & Huq, S. (2015). Coming full circle: The history of loss and damage under the UNFCCC. International Journal of Global Warming, 8(2), 141–157. doi: 10.1504/IJGW.2015.071964

- Schipper, E. L. F. (2009). Meeting at the crossroads? Exploring linkages between climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. Climate and Development, 1(1), 16–30. doi: 10.3763/cdev.2009.0004

- Schipper, E. L. F., & Pelling, M. (2006). Disaster risk, climate change and international development: Scope for, and challenges to, integration. Disasters, 30(1), 19–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2006.00304.x

- Seck, P. (2007). Links between natural disasters, humanitarian assistance and disaster risk reduction: A critical perspective. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme.

- Seneviratne, S. I., Nicholls, N., Easterling, D., Goodess, C. M., Kanae, S., Kossin, J., … Zhang, X. (2012). Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment. In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, … P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (pp. 109–230). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Stone, D. A., & Allen, M. R. (2005). The end-to-end attribution problem: From emissions to impacts. Climatic Change, 71, 303–318. doi: 10.1007/s10584-005-6778-2

- Stott, P. A., Gillett, N. P., Hegerl, G. C., Karoly, D. J., Stone, D. A., Zhang, X., & Zwiers, F. (2010). Detection and attribution of climate change: A regional perspective. WIREs Climate Change, 1, 192–211.

- Stott, P. A., Stone, D. A., & Allen, M. R. (2004). Human contribution to the European heat wave of 2003. Nature, 432, 610–614. doi: 10.1038/nature03089

- Surminski, S., & Eldrige, J. (2015). Observations on the role of the private sector in the UNFCCC’s loss and damage of climate change program. International Journal of Global Warming, 8(2), 213–230. doi: 10.1504/IJGW.2015.071955

- UNFCCC. (2012). A literature review on the topics in the context of thematic area 2 of the work programme on loss and damage: A range of approaches to address loss and damage associated with the Adverse Effects of Climate Change FCCC/SBI/2012/INF.14.

- UNFCCC. (2013). Report of the Conference of the Parties on its eighteenth session, held in Doha from 26 November to 8 December 2012. FCCC/CP/2012/8.Add.1.

- UNFCCC. (2015). Synthesis report on the aggregate effect of the intended nationally determined contributions. FCCC/CP/2015/7.

- UNFCCC. (2016). Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015. FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1.

- UN General Assembly. (2015). Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015: Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E

- UNISDR. (2015). Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction 2015: Making development sustainable: The future of disaster risk management. Geneva: Author.

- UNOCHA. (2014). Philippines: The challenge of ‘building back better’ (7 February 2014). Retrieved from http://www.unocha.org/top-stories/all-stories/philippines-challenge-’building-back-better’

- Verheyen, R. (2012). Tackling loss and damage. Bonn: Germanwatch.

- Warner, K., & van der Geest, K. (2013). Loss and damage from climate change: Local level evidence from nine vulnerable countries. International Journal of Global Warming, 5(4), 367–386. doi: 10.1504/IJGW.2013.057289

- Warner, K., van der Geest, K., & Kreft, S. (2013a). Pushed to the limit: Evidence of climate change-related loss and damage when people face constraints and limits to adaptation, Policy Report No. 11. Bonn: United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS). Retrieved from: http://i.unu.edu/media/unu.edu/news/40704/LossDamage_Vol21.pdf

- Warner, K., van der Geest, K., Kreft, S., Huq, S., Harmeling, S., Kusters, K., & de Sherbinin, A. (2012). Evidence from the frontlines of climate change: Loss and damage to communities despite coping and adaptation, Policy Report No. 9. Bonn: United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS). Retrieved from: http://unu.edu/publications/policy-briefs/evidence-from-the-frontlines-of-climate-change-loss-and-damage-to-communities-despite-coping-and-adaptation.html

- Warner, K., Kreft, S., Zissener, M., Höppe, P., Bals, C., Loster, T., … Oxley, A. (2013b). Insurance solutions in the context of climate-related loss and damage. UNU-EHS Publication Series, Policy Brief No. 6. Bonn: UNU-EHS. Retrieved from http://www.ehs.unu.edu/article/read/insurance-solutions-in-the-context-of-climate-change-related

- Warner, K., Yuzva, K., Zissener, M., Gille, S., Voss, J., & Wanczeck, S. (2013c). Innovative Insurance Solutions for Climate Change: How to integrate climate risk insurance into a comprehensive risk management approach, Report No. 12, Bonn: Munich Climate Insurance Initiative. Retrieved from http://www.ehs.unu.edu/article/read/innovative-insurance-solutions-for-climate-change-how

- Warner, K., & Zakieldeen, S. (2012). Loss and damage due to climate change: An overview of the UNFCCC negotiations. London: European Capacity Building Initiative. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordclimatepolicy.org/publications/documents/LossandDamage.pdf