ABSTRACT

This review assesses the empirical knowledge base on gender-based differences in access, use and benefits from rural climate services to analyse gender equality challenges and identify pathways for making climate services more responsive to the needs of rural women and men. While existing research is limited, the review identifies key gender-related factors and processes that influence inequalities in access and use. Differential access to group processes and to Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) can significantly limit women’s access to weather and climate information. Moreover, socio-cultural norms that define women’s and men’s labour roles can also influence the resources and decisions under women’s and men’s control, affecting their differing climate information needs and demand. Ways forward suggested by the literature concern inclusion of women’s groups and networks in communication channels and development of ICTs that respond to women’s preferences. Furthermore, meeting women’s climate information needs and pursuing cross-sectoral collaboration will be important to enhance action on climate information. Research opportunities include analyses of the potential for women’s and mixed-gender groups to enhance women’s access to climate information; evaluation of the communication processes that improve women’s understanding of climate information; and further connection with the body of knowledge on intra-household decision-making processes.

1. Introduction

While development of climate services for farmers has its roots in the development and application of seasonal climate forecasts to manage risk (Vaughan & Dessai, Citation2014), interest and investment have intensified in the past decade with the urgency of climate change and with the establishment of the UN Global Framework for Climate Services (GFCS) as an outcome of the World Climate Conference-3 (WCC-3) in 2009 (WCC-Citation3, Citation2009; Zebiak et al., Citation2014). Climate-related risk is a major obstacle to food security and rural prosperity. Climatic extremes, such as drought, floods or heat waves, can erode livelihoods through loss of productive assets, while the uncertainty associated with climate variability is a disincentive to investing in agricultural innovation (Carter & Barrett, Citation2006; Dercon, Citation1996; Maccini & Yang, Citation2009; Morduch, Citation1994; Simtowe, Citation2006). Because greenhouse gas forcing interacts with natural climate variability, farmers experience climate change not as a gradual trend but as shifts in the frequency and severity of extreme events. Within farming communities, the impacts of climate risk tend to exacerbate existing social inequality challenges (Arora-Jonsson, Citation2011; Carr & Thompson, Citation2014; Nelson, Meadows, Cannon, Morton, & Martin, Citation2002; Sultana, Citation2010). Evidence points to increasing risk from drought, flooding and heat waves in farming regions across much of the developing world (IPCC, Citation2012, Citation2014). Within an enabling environment, climate information and advisories allow farmers to understand risks, anticipate and manage extreme events, take advantage of favourable climate conditions, and adapt to climate change. Increasing investment in the quality and relevance of climate-related information is expanding the range of options available for making smallholder agriculture more resilient and prosperous in the face of climate risk.

Recognizing the challenge that social inequalities can pose to smallholder adaptation, climate service funders, implementers and researchers are raising concerns about the distribution of benefits – across gender lines and other social differences significant to socially- or economically-disadvantaged groups. Climate services can be a promising means of empowerment and resilience-building for rural women (Mittal, Citation2016; Rengalakshmi, Manjula, & Devaraj, Citation2018); however, they risk reinforcing the gender-based inequalities that are prevalent in other institutional structures if they fail to understand and effectively target the needs of both women and men (Carr & Onzere, Citation2017; Carr & Owusu-Daaku, Citation2016; Perez et al., Citation2015).

The paper reviews and assesses the existing empirical knowledge base on gender-based challenges in access, use and benefit from rural climate services in order to suggest pathways for achieving gender-responsive climate services. Specific objectives are to:( i) assess the evidence about gender-based trends and differences in access, use and benefits from climate services for smallholder farmers in the developing world; and based on this assessment, (ii) identify promising ways forward for making climate services more responsive to gender inequalities. Findings from the review highlight that gender trends in access, use and benefits can vary extensively across research sites; however, the existing research also indicates critical factors that can influence gender inequalities in access and use. Knowledge may be limited as it concerns benefits. Climate services can be gender-responsive by addressing these factors.

The following section presents the methods used for the literature review. The paper then explains the results from the review, according to gender dynamics surrounding climate services access, use and benefits. While the paper recognizes that other socioeconomic attributes such as ethnicity and seniority critically influence women’s and men’s capacities to access, use and benefit from climate services, it is important to highlight that the majority of literature reviewed analyses trends and differences between women and men without distinguishing different types of women and men. Accordingly, the review addresses gender’s inter-influence with other attributes as it arises in the body of studies. Following the presentation of results, potential pathways for achieving gender-responsive climate services are discussed. The paper then identifies knowledge gaps and opportunities for future research to promote gender-responsive climate services.

2. Methods

Climate services benefit a farmer or pastoralist when the information is accessed and used to modify climate-sensitive livelihood decisions in a manner that improves food security or some other objective (Vaughan, Hansen, Roudier, Watkiss, & Carr, Citation2019). Gender-related factors have the potential to influence the value of climate services by enabling or constraining the degree of benefit from improved management decisions, capacity to use information to improve management, or access to climate-related information. Correspondingly, the review groups the available empirical evidence into gender differences and trends in access, use and benefit.

The search is limited to empirical peer-reviewed publications and grey literature published from 2000 to 2018 that included results of women’s and men’s access, use and benefits from climate services, from the agricultural sector. Evidence from the publications identified were categorized and analysed as they addressed the following primary questions: (1) to what extent do gender differences in rates of access, use and benefit exist, and (2) what factors influence how women and men access, use and benefit from climate services? Concrete rates of access, use and benefits, as sought via question 1, can provide illuminating information for assessing to what extent gender differences exist. Then, question 2 is important for understanding the qualities of those differences, as well as the reasons for them. In addition to making use of online search engines such as Web of Knowledge, Science Direct, and Google Scholar, documents were identified via the authors’ professional networks. The grey literature included was limited to organizations that are known to have expertise in climate services, gender and evaluation, including the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

3. Results

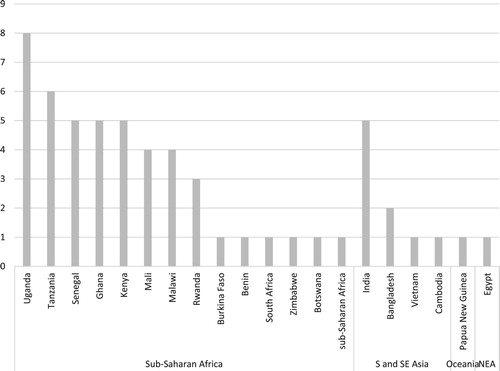

In total, 43 publications were included in the review. Almost all of the studies (37) address sub-Saharan Africa while eight studies address countries from South and Southeast Asia. Oceania and Northeast Africa are addressed minimally and in multi-country studies only.Footnote1 From the countries of the Sub-Saharan African region, Uganda is addressed most frequently in the literature (eight times), followed by Tanzania with six publications (See ). Senegal, Ghana and Kenya follow as frequent foci of research, each addressed five times.

presents the 43 studies, noting the category of gender information found (concerning access, use, and/or benefit), whether the research addresses one or both of the guiding questions mentioned above and the methods used. Most (37) of the publications address access, while 19 studies explore use. Benefits perceived from climate services is an area much understudied in the literature, addressed by just six publications.

Table 1. Studies included in the review.

It is important to highlight the variation of data collection methods used across studies, as they can have important implications for the gender results reported by the publications. While the methods are not always made explicit in all of the publications, the unit of analysis tends to vary; this can determine the extent to which robust gender analysis is possible. In particular, gender analysis can be limited for those studies that collect information from the household head only. This is due to the tendency for women to assume the role of spouse or partner to the household head rather than household head themselves; consequently, research focused on the household head effectively excludes assessment of the situation of a significant group of women (Doss, Citation2001; Doss & Kieran, Citation2014). Furthermore, women household heads can often face a decision-making and bargaining context distinct from that of women non-household heads; the household and farm labour roles they carry out and the time limitations they experience due to unpaid household labour can differ, as well. These distinctions can have important implications for women farmers’ capacity to access, use and benefit from climate services. In this review, a small group of studies notes the unit of analysis as the household head (Coulibaly et al., Citation2015a; Coulibaly, Kundhlande, Tall, Kaur, & Hansen, Citation2015b; Rao, Hansen, Njiru, Githungo, & Oyoo, Citation2015; Tall, Kaur, Hansen, & Halperin, Citation2015a; Tall, Kaur, Hansen, & Halperin, Citation2015b). Recognizing the importance of intra-household gender dynamics, a few studies collect data from both women and men primary decision-makers or spouses from within each household (Ngigi, Mueller, & Birner, Citation2017; Twyman et al., Citation2014). While the present review paper does not assess the significance of data collection methods for research findings reported, it is important to keep in mind that varying data collection methods can make it difficult to compare studies directly when considering the results discussed below.

The next sections discuss trends found in the literature concerning gendered access, use and benefits from climate services. Each section begins with a review of women’s and men’s rates of access, use or benefits (guiding question 1), followed by discussion of influences on gendered access and use (guiding question 2). No publications were found that address factors influencing gendered benefits; thus, there is no assessment of this theme.

3.1. Gender differences in access

Whether farmers access particular climate-related information products is determined by the types of information products that national meteorological services and other providers make available, by access to the communication channels used to disseminate information, and by demand for the information (Vaughan et al., Citation2019). Demand conditions the likelihood that women and men will exercise agency to access the information. In this way, an important feedback loop exists between use and access. While a small group of the publications reviewed provides information related to gendered rates of access (see ), a significant portion of the research on gendered access focuses on factors that influence access to communication channels that are or could be used for climate services. Fewer analyses concern the demand aspect of access. Publications indirectly treat demand as it relates to the tendency to use climate information, addressed in Section 3.2.

3.1.1. Gendered rates of access

summarizes sex-disaggregated rates of access to particular types of weather and climate information found in publications included in the review. As several of these are baseline survey reports, they tend to not include significant analyses of the factors that might account for differences and similarities in rates of access by women and men. Further, it is important to note that all studies referenced in concern climate information commonly available; they were not carried out in the context of interventions designed to enhance smallholder access to weather and climate information.

Table 2. Types of climate information received by gender.

Although the data may suggest in some instances that men access weather and climate information more than women, the range of studies may be too narrow to support this as a generalization. For example, men may tend to access weather and climate information more than women across CCAFS Climate-Smart VillagesFootnote2 as demonstrated by baseline assessments in Uganda, Kenya and Senegal and, in several instances, the differences are significant (Twyman et al., Citation2014). In several research sites in Rwanda, men also tend to access different types of weather and climate information more than women (Coulibaly, Birachi, Kagabo, & Mutua, Citation2017). In contrast, studies in Tanzania and Malawi found that the rates of access between women and men household heads are often similar, although in a few cases men may access information more often (Coulibaly et al., Citation2015a; Citation2015b).

With respect to type of climate information, men significantly access information on droughts more than women across Climate-Smart Village sites in Kenya and Uganda (Twyman et al., Citation2014). Similarly, research across three agro-ecological zones in Kenya involving husbands and wives of the same household found that men tend to have more access to early warning information for events such as droughts and floods; however, women tend to have more access to weather forecasts (Ngigi et al., Citation2017).

While the studies presented in do not assess explanatory factors, other publications highlight factors that can reduce or exacerbate gender inequalities in access to climate services. These studies tend to be carried out within the context of interventions, and the gendered analyses focus on issues of access to group processes and to Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). It is important to note that each of the different communication channels discussed should not be considered as substitutes for each other; rather, each is appropriate for certain situations and types of climate information.

3.1.2. Biased institutions and differences in group participation and networks

Peer groups and networks can serve as important means for the flow of useful climate information (Meinke et al., Citation2006). Moreover, group-based approaches can help farmers share knowledge and build resilience to climate risk (Ngigi et al., Citation2017). Notwithstanding, several studies included in the review show that socio-cultural norms can define women’s and men’s responsibilities and the spaces where these are carried out; this can restrict women’s access to important public meeting spaces and activities where weather and climate-based advisories are shared. For instance, research in Tanzania and Burkina Faso demonstrates that women are often limited from participating in trainings and meetings where climate-based advisories are discussed due to norms that associate public meeting participation with men and restrict cross-gender interaction in public spaces (CICERO, Citation2017; Roncoli et al., Citation2009; Roncoli, Ingram, Kirshen, & Jost, Citation2003). Ethnicity can play a significant role as well, with gender-differentiated access to public meetings varying among ethnic groups (Roncoli et al., Citation2003). Furthermore, women’s capacity to access agro-meteorological advisories and weather and climate information is enhanced when services and information sources are located within the village, where women’s childcare and household responsibilities tend to take place (Rengalakshmi et al., Citation2018; Venkatasubramanian, Tall, Hansen, & Aggarwal, Citation2014; Zamasiya, Nyikahadzoi, & Mukamuri, Citation2017).

Moreover, Venkatasubramanian et al.’s (Citation2014) research in India suggests that farmers’ group requirements that disadvantage women can limit women’s access to weather-based agro-advisories. Participation in farmers’ clubs can facilitate enhanced knowledge and awareness of agro-meteorological advisory services; however, annual membership fees can be costly for resource-poor farmers, including women, thus limiting their opportunity to participate. This resonates with other agricultural research (e.g. Manfre et al., Citation2013; Mudege, Chevo, Nyekanyeka, Kapalasa, & Demo, Citation2015; Mudege, Mdege, Abidin, & Bhatasara, Citation2017) demonstrating that, while extension services may seek to enhance reach via coordination with producer associations or cooperatives, women may be underserved via this channel due to membership criteria based on land ownership and other capital requirements. Because customs that favour men over women for land inheritance result in women having formal land rights far less frequently than men, such membership requirements effectively exclude women from the technical information and training that farmers’ groups often make available. Furthermore, Rengalakshmi et al. (Citation2018) highlight that while men may share the climate forecast information and advisories accessed from the groups in which they participate with women, it may not be complete enough for women to comprehend and apply it in their farm management decision-making.

Despite the challenges of accessing farmers’ groups, India-focused publications also highlight that women can access information from agro-meteorological services through community and women’s self-help groups (Venkatasubramanian et al., Citation2014). Rengalakshmi et al. (Citation2018) note that a women-managed Village Knowledge Center and the incorporation of gender-sensitive group processes in communication channels has helped to stimulate women’s confidence in seeking weather and climate information in Tamil Nadu, India. Furthermore, women ‘communicators’ have played an important role in disseminating and enhancing the utility of climate information and weather-based agro-advisories for women (Rengalakshmi et al., Citation2018; Venkatasubramanian et al., Citation2014).

While women’s groups may serve as useful communication channels, other publications suggest that the type and scope of men’s networks can be more advantageous for sharing and accessing weather and climate information. For example, Ngigi et al.’s (Citation2017) study in Kenya demonstrates that men’s membership in social groups tends to be longer-lasting and the groups they belong to have a greater tendency to be mixed-gender in comparison to women, earning men a higher score on the study’s social capital index. Manfre and Nordehn’s (Citation2013) study in Kenya also notes that men’s networks may tend to be comprised of more diverse sources of information, such as agricultural contacts located outside of the village. Additionally, Ngigi et al.’s (Citation2017) research in Kenya indicates that husbands and wives who belong to social groups tend to have greater access to early warning information and to more sources of information; however, a greater proportion of husbands acquire climate information through social groups. The greater effectiveness and reach of men’s networks for sharing climate and weather information, as suggested by the above studies, aligns with another trend identified in other publications addressing Rwanda, Vietnam and Cambodia: while both women and men farmers share weather and climate information received through trainings and additional means with others, men may be more likely to share information beyond the family (e.g. with other farmers) (Clarkson, Dorward, Kagabo, & Nsengiyumva, Citation2017; Coulier, Citation2016; Coulier & Wilderspin, Citation2016).

3.1.3. Access to information through media and ICT

Interactive radio programming and ICTs are increasingly being used to communicate agriculture and climate information to smallholder farmers, with promising opportunities to reach farmers across great spatial scales (Davis, Tall, & Guntuku, Citation2014; Hampson et al., Citation2014; Mittal, Citation2016; Tall et al., Citation2014a). Although they may not be well-suited to purveying information at a climate timescale, ICTs may be particularly useful for communicating information at a weather timescale.

Despite the potential use of ICTs as a communication channel, findings from the review demonstrate that men tend to own communication assets such as radios and mobile phones more than women, thereby potentially limiting women’s access to climate information products via these means (CICERO, Citation2017; Coulibaly et al., Citation2017; Hampson et al., Citation2014; Kyazze, Owoyesigire, Kristjanson, & Chaudhury, Citation2012; Owusu, Yankson, & Frimpong, Citation2017; Tall et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Partey et al., Citation2018; Stats4SD, Citation2017). Lack of financial resources can limit women’s ownership and use of mobile phones (Blumenstock & Eagle, Citation2012; GSMA, Citation2012; Hampson et al., Citation2014; Scott, McKemey, & Batchelor, Citation2004; Wong, Citation2012). In addition, a four-country study of women’s mobile phone ownership and use finds that spousal disapproval can be a deterrent to women’s mobile phone ownership (GSMA, Citation2012). When women do access mobile technologies and radio programmes, they are more likely than men to confront challenges to using mobile devices and understanding the information transmitted due to gender inequalities in literacy, formal education and technical literacy (Caine et al., Citation2015;CICERO, Citation2017; GSMA, Citation2012; Partey et al., Citation2018; Owusu et al., Citation2017; Scott et al., Citation2004). Highlighting the significance of technical literacy, a few studies analysing ownership and use trends related to age indicate that younger individuals access ICTs more than older women and men (Chaudhury, Kristjanson, Kyagazze, Naab, & Neelormi, Citation2012; Cherotich, Saidu, & Omedo Bebe, Citation2012).

The literature reviewed also suggests that time limitations women experience as a result of their roles in household work and childcare may restrict their time available to listen to radio programs. For instance, cases in India, Senegal, Malawi, South Africa and Tanzania demonstrate the significance of time-labour burdens as barriers to women’s radio access (Archer, Citation2003; CICERO, Citation2017; Poulsen, Sakho, McKune, Russo, & Ndiaye, Citation2015; Tall et al., Citation2015a; Venkatasubramanian et al., Citation2014). Although a household radio may provide opportunities for shared listening among the family, research in Malawi and Tanzania demonstrates that men tend to listen to the radio more often than women (Hampson et al., Citation2014). In addition, a study in Rwanda shows that men are more likely to access educational radio programs (Coulibaly et al., Citation2017). Exceptions to this trend are found in Cambodia and in pastoralist communities in Tanzania (Coulibaly et al., Citation2015a; Coulier & Wilderspin, Citation2016; Tall et al., Citation2015b); concerning the latter, women spend more time in the home and have greater opportunity to listen to the radio in comparison to men. In recognition of the obstacles women confront in listening to the radio, an evaluation of an intervention in Tanzania recommends that weather and climate forecasts and advisories be transmitted several times during the day to facilitate more opportunities for women to access them (CICERO, Citation2017). Similarly, Caine et al. (Citation2015) find that mobile phones can be a convenient means of accessing information for women, who are often limited from other channels due to mobility and time constraints. In general, research on ICT-use in agriculture emphasizes that for services to be useful to women, they must incorporate time-saving mechanisms (USAID, Citation2012).

Furthermore, publications show that the daily activities that women and men carry out can influence their differing purposes for using mobile phones. For example, while men in Uganda may use mobile phones more for agricultural purposes, women are more likely to use mobile phones for both kinship maintenance and agriculture (Martin & Abbott, Citation2011). Highlighting the importance of women’s kin and friends for their information and asset-sharing, some studies demonstrate that women tend to share phones more than men and that they often access phones through friends and family (Blumenstock & Eagle, Citation2012; GSMA, Citation2012; Hampson et al., Citation2014; Stats4SD, Citation2017).

The literature highlights that women and men farmers may have differing means of accessing weather and climate information due to gender-based challenges in access to communication channels, particularly those concerning group processes and ICTs and media-based services. Although the existing research does not go into deeper analysis, the studies suggest that gender influences access to communication channels through the roles and responsibilities that women and men carry out in the household and community, their differences in asset ownership, and normative structures and institutions that work to favour men’s participation over women’s in extra-communal activities and organizations. The factors influencing gender trends in access are similar to those identified concerning use, but are also distinct. As the literature minimally addresses benefits, the studies that do so are included in the discussion of use.

3.2. Gender differences in use and benefit

While the studies included in the review minimally address the gender factors that influence benefits from climate services, a significant portion of the studies do analyse those factors that condition women’s and men’s use of weather and climate information (see ). In particular, these publications tend to emphasize how socio-cultural norms concerning gender labour roles and responsibilities can influence the productive resources and decision-making processes under women’s and men’s control; correspondingly, this dynamic affects women’s and men’s risk perceptions and concerns as well as the types of climate information that will be most useful to women and men (Carr & Owusu-Daaku, Citation2016; Carr, Fleming, & Kalala, Citation2016a; Carr, Onzere, Kalala, Rosko, & Davis, Citation2016b; Rengalakshmi et al., Citation2018; Tall, Kristjanson, Chaudhury, McKune, & Zougmore, Citation2014c). The studies also illustrate how gendered division of labour, resource control and decision-making power can influence women’s and men’s differential capacities to act on information (Carr, Citation2014; Carr, Citation2014; Carr et al., Citation2016b; Carr & Onzere, Citation2017; Carr & Owusu-Daaku, Citation2016; Coulibaly et al., Citation2015a; Poulsen et al., Citation2015; Poulsen et al., Citation2015; Roncoli et al., Citation2009; Sandstrom & Strapasson, Citation2017; Serra & McKune, Citation2016; Stats4SD, Citation2017; Tall et al., Citation2015b).

3.2.1. Gendered rates of use and benefit

Within the literature reviewed, there is a subset of studies that reports rates of women’s and men’s use of different types of weather and climate information (). While limited in number, the studies suggest that it is difficult to discern particular gendered patterns in use. Among four CCAFS Climate-Smart Villages at baseline, women and men in Kaffrine, Senegal, show similar rates of use of types of weather and climate information with the exception of drought early warning, for which a greater proportion of men than women report using this type of information for making change to their agricultural management strategies (Twyman et al., Citation2014). In addition, across the four sites, almost all women and men report use of onset of rainfall forecast information; only in Nyando, Kenya, did women report using the information slightly more than men. Coulibaly et al.’s (Citation2017) baseline study in Rwanda suggests that women and men tend to act on weather and climate information at similar rates across all provinces except for the Northern Province, wherein men show the tendency to report greater use. Clarkson et al.’s (Citation2017) monitoring and evaluation of the Participatory Integrated Climate Services for Agriculture (PICSA) in Rwanda demonstrates that, while both women and men demonstrate high rates of putting information accessed to use, significantly larger proportions of men report making changes in crop and non-agricultural enterprises. Similar proportions of women and men make changes in livestock enterprises (Clarkson et al., Citation2017). Additional PICSA monitoring and evaluation studies in other countries show heterogeneity in gender trends concerning use of information as well (Stats4SD, Citation2017). For the studies discussed thus far in this section, the sample size is limited to those men and women who had access to the climate or weather information or participated in the intervention.

As noted above, few of the publications reviewed address benefits to women and men farmers from use of climate services (), and those that do tend to address perceived benefits. As occurs with the information from studies on use, results concerning gendered benefits vary across studies. Except for Amegnaglo, Asomanin, and Mensah-bonsu (Citation2017), all those discussed here were carried out in the context of interventions. Research in Eastern Kenya (Rao et al., Citation2015) and in Benin (Amegnaglo et al., Citation2017) find that both women and men report willingness to pay for climate services, thus indicating similar benefits perceived, although the sample size of women in comparison to men is small for the Benin study. Similarly, an evaluation of climate services interventions in Tanzania and Malawi demonstrates that there are no significant differences in rates of perceived household benefits reported among men and women household heads in Tanzania; in contrast, male household heads in Malawi perceive more household benefits from climate services trainings, particularly concerning improved income and health care (Stats4SD, Citation2017). Monitoring and evaluation of PICSA trainings in Rwanda notes that high proportions of women and men report greater confidence in planning agricultural and non-agricultural enterprises and in discussing livelihood strategies with fellow farmers, with no significant gender differences (Clarkson et al., Citation2017). Although the data is limited, studies in India suggest that climate services benefit women farmers through increased capacity to make informed decisions and more active participation in agricultural decision-making processes (Mittal, Citation2016; Rengalakshmi et al., Citation2018).

The variations in gendered patterns in use of and benefits from climate services point to the need to understand underlying factors that influence how and when women and men act upon information received. The literature included in the review provides some insights into how factors such as socio-cultural norms, access to and control over resources and decision-making power can influence women’s and men’s proclivity to use climate services. Slightly more than half of the publications discussed below address research carried out in the context of interventions. More than the literature on access, findings concerning use address the influence of other socio-economic attributes, such as seniority and ethnicity, on gender.

3.2.3. Influences and constraints on use of information

Key to effective rural climate services is assessment of the suitability of weather and climate information products to livelihoods strategies (Vogel & O’Brien, Citation2006). To serve as a tool for resiliency-building, climate services must critically consider farmers’ needs for climate risk management. The literature reviewed shows that climate information needs can vary substantially according to gender, illustrating that norms that define women’s and men’s roles and responsibilities can significantly condition their resource access and influence the type of information that women and men find useful (Carr et al., Citation2016a; Carr et al., Citation2016b; Carr & Owusu-Daaku, Citation2016; Tall et al., Citation2014b). Tall et al.’s (Citation2014b) study in Kaffrine, Senegal shows that women farmers are more interested in information on droughts and rain cessation than men because social norms dictate that women labour on men’s plots before their own and must also wait to use men’s farming equipment; consequently, women tend to plant later. Similarly, research in Mali indicates that precipitation information may be minimally relevant to women groundnut producers due to gender norms that tend to prioritize men’s plots over their own and drive them to plant later (Carr et al., Citation2016b). In addition, Carr et al. (Citation2016b) highlight that the women may feel inhibited from using the precipitation data to its fullest extent due to repercussions they could experience if their increased production were to be seen as a threat to their husbands’ authority.

Emphasizing how seniority can influence the household responsibilities and decision-making roles that women and men assume, Carr and Owusu-Daaku’s research (Citation2016) also suggests that junior and senior women and men farmers in Mali can have differing interests in the information that advisory services provide due to the farmers’ varying prioritization of subsistence or market production (Carr & Owusu-Daaku, Citation2016). Another study (Carr et al., Citation2016a) in Ngetou Maleck, Senegal finds that junior and senior women farmers’ varying access to farming equipment, secondary income and farm animals influences the primary shocks and stresses they perceive; furthermore, their differential access to these key resources conditions the type of weather and climate information that is most useful for them. Moreover, because they have fewer domestic obligations, senior women in Senegal can often cultivate sooner than their junior counterparts; thus, climate information can be more relevant for the former.

Furthermore, studies included in the review suggest that the concerns and risks perceived by women and men smallholder farmers can critically influence their climate information needs. This aligns with other development literature that emphasizes how gender-specific household roles and responsibilities can condition risk perceptions among pastoralists and farmers (Cullen, Leigh Anderson, Biscaye, & Reynolds, Citation2018; Quinn, Huby, Kiwasila, & Lovett, Citation2003; Smith, Barrett, & Box, Citation2000; Smith, Barrett, & Box, Citation2001). For example, Rengalakshmi et al.’s study (Citation2018) in Tamil Nadu, India, highlights how women’s and men’s differing agricultural concerns and perceived risks can influence the relevance of the content of weather and climate information products to them. Men in the study site may be interested in the weather to address concerns regarding crop selection, an issue for which they tend to be the prime decision-makers; in contrast, women’s concerns for the harvest and the need for tree sub-products and crop residues to feed their goats can influence their interest in weather information. Similarly, Carr’s approach (Carr, Citation2014; Carr et al., Citation2016a; Carr et al., Citation2016b; Carr & Onzere, Citation2017) to understanding farmers’ weather and climate information needs focuses on assessing their shocks and stresses perceived as they relate to their livelihoods activities and concerns.Footnote3

While several publications highlight how gender dynamics can critically influence the types of weather and climate information that will be most relevant to women and men, others emphasize that differences in access to resources can limit women’s abilities to use climatic information. A study by Sandstrom and Strapasson (Citation2017) suggests that access and utilization of productive assets and inputs can be important preconditions for the use of climate information for women just as much as they are for men. Thus, the analysis highlights the significance of inequalities in meaningful access to inputs for gender-equitable action on climate information. Other studies find that women have less access to financial capital and productive assets (e.g. farming equipment and seeds) needed to be able to act on climate-based advisories (Carr, Citation2014; Carr et al., Citation2016b; Coulibaly et al., Citation2015a; Poulsen et al., Citation2015; Tall et al., Citation2015b). Carr et al. (Citation2016b) notes that in Mali even women household heads, who have greater decision-making power over rain-fed crops than women in male-headed households, are often constrained from acting on precipitation information due to lack of access to resources. Similarly, research in Malawi shows that women household heads more frequently report that lack of money is an obstacle to incorporating climate services training into decision-making on crop enterprisesFootnote4 (Stats4SD, Citation2017).

Furthermore, studies highlight that not only control of productive resources but also norms concerning women’s and men’s labour roles and participation in agricultural decision-making can condition differences in their capacities to act on climate information. In general, gendered household and farm labour roles can influence how women and men act upon weather and climate information and agro-meteorological advisories (Jost et al., Citation2016; Mittal, Citation2016; Venkatasubramanian et al., Citation2014). In particular, several publications indicate that women’s limited control of land and limited involvement in decision-making over rain-fed crops (or agriculture in general) can make climate information irrelevant for women (Carr, Citation2014; Carr et al., Citation2016b; Carr & Onzere, Citation2017; Carr & Owusu-Daaku, Citation2016; Poulsen et al., Citation2015; Roncoli et al., Citation2009; Serra & McKune, Citation2016). In addition, Carr and Onzere’s (Citation2017) research in Mali demonstrates that junior men’s ability to use climate information depends on their access to land and farming equipment controlled by senior men. In general, the study suggests that households of junior adults are less able to act on information. However, other research in Mali (Carr, Citation2014) adds a gendered intra-household dimension that complicates the finding regarding seniority, indicating that even when women may have their own plots of land, they have limited decision-making power regarding crop selection, often deferring to male household members’ authority; consequently, climate information can be less actionable for them. Furthermore, Carr and Onzere (Citation2017) highlight that agricultural decision-making can be more inclusive among partners in Mali, depending on ethnicity. For example, Malinke women may wield greater household decision-making power than those in other ethnic groups and have more opportunity to put climate information to use.

The existing research shows that gender critically influences women’s and men’s weather and climate information needs; it also conditions their capacities to use weather and climate information in their livelihood decision-making. Specifically, the literature reviewed demonstrates that the roles that women and men carry out can influence the productive resources and decisions under their control and consequently, their concerns and weather and climate information needs. Moreover, extreme resource limitations and restricted opportunity to participate in agricultural decision-making can inhibit women’s capacity to act on weather and climate information in some cases. This also has important repercussions for gender-differentiated demand for the information. The gender-influenced challenges to use weather and climate information, as well as those concerning access, are important areas of focus for the development of gender-responsive climate services.

4. Discussion

4.1. Pathways for making climate services more gender-responsive

Results from the literature review highlight that certain gendered processes and factors can condition women’s and men’s access to and use of climate services. As previously noted, evidence concerning benefits is limited. The findings suggest a few guideposts for developing more gender-responsive climate services (). The first three deal with gender-based challenges to access.

Table 3. Key factors and potential ways forward for the development of gender-responsive climate services.

Develop ICT-based communication channels appropriate to women’s needs. Gender-based constraints to access ICTs often disadvantage women; as a result, they can also have restricted access to routine weather information and advisories. Thus, it is critical that interventions targeting use of ICTs (1) consider local intra-household trends in accessing communication assets, (2) seek to understand the conditions through which women are able to access information via ICTs, and (3) use them to enhance climate services’ reach to women (). An example underway is the project, ‘Climate services for agriculture’ in Rwanda, which incorporates baseline research on men’s and women’s asset control and access to communication channels to design ICT or media-based communication tools that enable farmers to access climate information (Nsengiyumva, Kagabo, & Gumucio, Citation2018).

Include women’s groups and information-sharing mechanisms as communication channels. Institutional biases and differential access to formal group processes can constrain women’s access to technical information, trainings and planning processes related to weather and climate-based advisories and climate risk management. Including women’s groups and networks in climate information and rural advisory delivery may help National Meteorological Services (NMS) and agricultural extension services address this challenge (). Participatory Action Research (PAR) methodologies can be useful to identify group processes and information-sharing mediums suited to women’s access constraints, also (Tall et al., Citation2014a; Citation2014b).

Connect with local and civil society organizations to address socio-cultural norms that constrain women’s access. It is important that interventions recognize that enhancing women’s access to characteristically male groups and public sphere activities depends upon shifts in often deeply-entrenched socio-cultural norms and institutions. Collaboration with local partners and organizations () who are engaged in gender consciousness-building and who are cognizant of indigenous normative structures surrounding gender will be important in designing socially-relevant climate services (Cornwall, Citation2016).

There may be less documentation of potential ways forward concerning use of weather and climate information in livelihood planning. However, the existing research points to a few pathways.

Meet women’s climate information needs. The publications included in the review highlight how socio-cultural norms concerning labour roles can influence the resources and decisions under women’s and men’s control; this in turn affects the types of weather and climate information that are useful to women and men. For this reason, effective climate services must identify women’s and men’s information needs specific to their service area (). This resonates with other literature on information services that highlights how understanding gendered content preferences can be critical in designing interventions that are equally beneficial to women and men (Huyer, Citation2006; Nath, Citation2006). In addition, it will be critical to consider how women’s and men’s climate information needs vary according to seniority, ethnicity and other socio-economic aspects. Approaches such as the Livelihoods as Intimate Government (LIG) (Carr, Citation2013) can provide a useful methodology and framework for differentiating groups of women and men farmers according to assemblages of vulnerabilities, the livelihoods strategies and decisions in which they engage and their corresponding climate information needs (Carr et al., Citation2016a; Carr & Onzere, Citation2017). While an important pathway, it also constitutes a challenge similarly echoed in other climate services research: how to develop climate information products that account for context-specific gender-differentiated needs while scaling up climate services (Tall et al., Citation2014a).

Integrate climate services with rural development efforts that seek to overcome women’s resource and agency constraints. Limited resource control and lack of opportunity to participate in agricultural decision-making can significantly restrict women’s capacity to make full use of climate information and also act as a deterrent to women’s demand for information (). While it can be difficult for climate services alone to address the extreme challenges that more marginalized groups confront in acting on climate and weather information, coordination with other sectors can be key in enhancing the intended impacts of interventions to address such challenges (Carr & Onzere, Citation2017). Cross-sectoral collaboration resonates with Hansen, Mason, Sun, and Tall’s (Citation2011) observation that it may be necessary for climate services to identify opportunities for integrating climate services with larger programs or policies for the services to be truly actionable for farmers. Based on the existing research, it may be difficult to develop suggestions as to how to concretely implement this pathway; however, a robust understanding of how climate services can work in the context of rural development efforts that seek to overcome women’s structural resource constraints will be an important area for future research.

4.2. Knowledge gaps and research opportunities

Although the significance of gender to climate services is increasingly recognized as an important focus of investigation, the limited number of relevant studies identified for the review demonstrates that additional empirical research on the theme is paramount. The review indicates priority evidence gaps and research opportunities to address for the development of rural climate services that truly respond to gender-based challenges to access and use. Increased, nuanced understanding of gender differences in benefits will be important for assessing how climate services can contribute to an enabling environment for women’s empowerment. The first four themes concern key evidence gaps.

Regional. Although the significant amount of studies on sub-Saharan Africa is important, increased research in other regions is necessary, given varied climate change impacts and adaptation and resiliency needs of smallholder farmers in other parts of the world. This is especially critical considering the context-specific nature of gender dynamics.

Benefit and demand. A blatant gap exists concerning how women and men benefit from their use of climate services. Furthermore, while the literature reviewed suggests that women and men farmers’ demand for information can depend upon its relevance to their decision-making and risk management, more studies on gender-differentiated demand will be important in order to develop a more complete understanding of gender-based challenges, particularly as they concern access.

Assess the influence of climate services on women’s participation in decision-making. While acknowledging the resource constraints that women confront, it is important to note that a few studies suggest that access to weather forecasts helps women to make informed agricultural decisions (Mittal, Citation2016; Rengalakshmi et al., Citation2018). In the process, their increased role in agricultural decision-making has influenced a shift in gender roles, wherein men are no longer the sole decision-makers and women are seen as more than farm labourers (Rengalakshmi et al., Citation2018). More in-depth impact assessments concerning changes in women’s and men’s roles in agricultural and household decision-making due to their access to climate information products will be key to understanding how climate services can contribute to women’s empowerment.

‘Success stories’ of interventions that enhance women’s ability to act on weather and climate information. Similarly, little research exists that documents ‘success stories’ of women’s increased use of climate-related information in decision-making at a project level, including analyses of possible enabling factors and mechanisms. This contrasts with the existing knowledge base on gendered access, which includes studies of interventions and mechanisms that have contributed to women’s enhanced access (Tall et al., Citation2014a; Citation2014b; Venkatasubramanian et al., Citation2014). An important, related line of inquiry is whether women face more significant, gender-based structural constraints to take action on climate information, rather than to accessing the information.

Given the results of the review, four priority research questions and themes emerge for enhancing efforts to promote gender-responsive climate services.

Compare potentialities of mixed-gender and women’s groups. Research that evaluates the conditions under which mixed gender or female-dominated group processes are more effective for enhancing women’s access to climate information will be critical to clarifying potential pathways for designing gender-responsive climate services. Such research is important, given other research on women’s group participation that shows female-dominated natural resource management groups can perform worse than mixed or male-dominated groups, in part due to gender inequalities in access to productive resources (Mwangi, Meinzen-Dick, & Sun, Citation2011). However, in those cases where strict cultural norms limit male-female interaction in public, female-dominated natural resource management groups can be an important means to enable women’s meaningful participation in information-sharing and public decision-making processes.

Understand what combination of communication processes best enable women to understand and act on information. Existing studies are useful in highlighting trends in and barriers to women’s and men’s ICT access and use; notwithstanding, research that analyses when ICTs or face-to face training and discussion is more useful to women will help identify more gender-responsive communication channels. While ICTs may be helpful for particular types and timescales of information, other channels might be better suited to enable women’s understanding and use of complex forms of information. This is key, considering that studies in the review suggest that women can face challenges to understanding and interpreting the technical information that constitutes forecasts and climate data (Carr et al., Citation2016b; Coulier, Citation2016; Kyazze et al., Citation2012; Venkatasubramanian et al., Citation2014). Venkatasubramanian et al.’s research (Citation2014) in India also indicates that women may appreciate the opportunity to speak in-person with information intermediaries, such as village meteorological office representatives and local NGOs.

Understand how gender interacts with other socioeconomic attributes to shape access preferences and information needs. Studies show that socio-economic attributes such as life-stage (Chaudhury et al., Citation2012; Cherotich et al., Citation2012), seniority (Carr et al., Citation2016a; Carr & Owusu-Daaku, Citation2016) and ethnicity (Roncoli et al., Citation2003) can intersect critically with gender and influence women’s and men’s household decision-making roles and access to group processes, among other important factors for effective access and use of climate services. Approaches such as the LIG (Carr et al., Citation2016a; Carr & Onzere, Citation2017) can permit differentiation of types of women and men farmers and identification of their information needs and delivery preferences.

Increase linkages with the body of knowledge on intra-household decision-making. Research demonstrates that the household decision-making context may constitute a complex arena wherein spouses contest and consult each other (Carr, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Farnworth, Stirling, Chinyophiro, Namakhoma, & Morahan, Citation2017). While there exist a few studies in the review that recognize livelihood management as a process of negotiation and contestation involving different household members, more research that analyses the intra-household decision-making processes surrounding the use of climate information for agricultural and household planning will be important to develop interventions that enhance action on information (Carr et al., Citation2016a; Carr & Onzere, Citation2017).

5. Conclusions

The existing knowledge base on gender differences in access, use and benefit from rural climate services may be limited, and general findings can highlight the context-specific nature of gender trends. Nonetheless, the literature reviewed illustrates key factors and processes that can influence gender inequalities in access and use. The evidence concerning benefits is particularly scarce. Gender-based differences in access to group processes and to ICTs can limit women’s access to weather and climate information. Furthermore, socio-cultural norms that define gendered labour roles can influence the resources and decisions under women’s and men’s control, thereby conditioning the types of climate information that are useful to women and men. Factors related to the gender division of labour, resource control and decision-making power can also influence women’s and men’s differing capacities to use weather and climate information to manage risks and make changes in livelihood planning.

From the understanding of principal gender-based challenges, it is possible to suggest priority areas for improving practice and achieving gender-responsive climate services. Development of ICTs appropriate to women’s needs and inclusion of women’s groups in communication channels can help enhance women’s access to climate and weather information. Moreover, linkages with local and civil society organizations will be important in addressing socio-cultural normative structures that restrict women’s access. Meeting women’s climate information needs is also a critical pathway for enabling women’s use of weather and climate information in livelihood planning. Furthermore, collaboration with robust initiatives on sustainable rural development will be key for overcoming the extreme resource and decision-making constraints faced by some women.

Addressing critical knowledge gaps and pursuing associated research opportunities is requisite for designing climate services that respond to gender inequalities. Important evidence gaps exist concerning how gender influences climate services access and use in other regions besides sub-Saharan Africa. Additional research is also necessary regarding gender-based benefits from climate services and gendered trends in demand. More documentation and analyses of gender-differentiated benefits and impacts will be particularly key to developing a fine-tuned understanding of how climate services can contribute to women’s empowerment (e.g. enhanced voice in decision-making). Critical research questions moving forward concern how women’s and mixed-gender groups may differentially enable women’s enhanced access to climate information, and which combination of communication processes can promote women’s understanding of information. Moreover, it will be important for future research to continue to connect with the knowledge base on intra-household decision-making processes and seek to understand how gender interacts with other socioeconomic attributes for better identification of gender-based climate information needs.

Such combined efforts on the part of researchers, practitioners and funders will be critical to ensuring that climate services truly serve the needs and interests of women and men smallholder farmers most vulnerable to climate-related risk. Current knowledge on gender-based challenges to access, use and benefit from climate services begins to identify pathways and opportunities for the development of gender-responsive rural climate services. More nuanced knowledge development will be important in order to understand the enabling environment necessary for climate services to contribute to women’s empowerment. In this way, climate services can contribute to adaptation strategies that do not just avoid exacerbating gender inequalities, but aim to reduce them.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the comments of consortium members of the Climate Information Services Research Initiative (CISRI) on an earlier draft of this paper. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. Many thanks to Alison Rose for her previous comments and for her inputs on tables developed, as well. This work was implemented as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), which is carried out with support from the CGIAR Trust Fund and through bilateral funding agreements. For details please visit https://ccafs.cgiar.org/donors. The views expressed in this document cannot be taken to reflect the official opinions of these organizations. It also contributes to the USAID-funded Learning Agenda on Climate Services https://www.climatelinks.org/projects/learningagendaonclimateservices

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Tatiana Gumucio is a Postdoctoral Research Scientist based at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI), at Columbia University, New York. Her research analyses how social differences such as gender, ethnicity and race influence smallholder farmers’ risk perceptions, climate information needs and capacities to respond and adapt to climate variability and change. She seeks to inform effective and equitable decision-making and programme development related to climate in the agricultural and food security sectors. She holds a PhD in anthropology from the University of Florida.

James Hansen is a Senior Research Scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI), at Columbia University, New York, where he has worked since 1999. Since 2010, he has also worked with the CGIAR research program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), where he leads the Flagship on Climate Services and Safety Nets. His research focuses on finding practical, equitable and scalable solutions to the challenges of making smallholder livelihoods more resilient through improved climate risk management, climate services, climate-related insurance and food security management. He holds PhD in Agricultural and Biological Engineering from the University of Florida. He has served as Editor of Agricultural Systems.

Sophia Huyer is Gender and Social Inclusion Leader at the CGIAR Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security Programme (CCAFS) as well as Director of Women in Global Science and Technology (WISAT) based in Brighton, Ontario. Recent publications include the chapter ‘ICT in a changing climate: A path to gender transformative food security’ in Taking Stock: Data and Evidence on Gender Digital Equality published by EQUALS Research at UNU Macau, and the introduction to a special issue on Gender, Agriculture and Climate Change in Gender, Technology and Development. Currently, she is Guest Editor on a special issue of Climatic Change on Gender Transformative Climate-Smart Agriculture: An Action Framework.

Dr. Tiff van Huysen has a PhD in ecosystem ecology and biogeochemistry. She recently graduated from the MA Program in Climate and Society at Columbia University, having returned to school to pursue her interest in working at the interface of physical and social science. Since graduating from the MA program, she has contributed to publications on the intersection of gender and the provision of climate services for smallholder farmers as part of a consultancy with the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), served as a Guest Editor for a special issue of Climate Risk Management on the scalability of climate services for smallholder farmers, co-authored a publication on the role of the Green Climate Fund in Africa for the journal Climate Policy, taught a course on climate change for The Earth Institute Center for Environmental Sustainability, contributed to a ClimaSouth Project concept note on the establishment of a climate change Center of Excellence in Egypt and is co-authoring a primer on the environmental sustainability of food and farming (to be published by Columbia University Press). She was also guest lecturer and teaching assistant for the MA Program in Climate and Society and the Summer Ecosystem Experiences for Undergraduates (SEE-U) agroecology class at Columbia University. Prior to returning to school to pursue her MA degree, Tiff worked for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service managing an applied research programme.

ORCID

Tatiana Gumucio http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9389-2703

James Hansen http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8599-7895

Sophia Huyer http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6267-8667

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Several of the publications were multi-country studies, including countries from different regions. One publication (Caine et al., Citation2015) referred to sub-Saharan Africa without significantly identifying countries.

2 Climate Smart Villages are territories distinguished by high-climatic risk and wherein CCAFS partners have established strong links with local communities. (https://ccafs.cgiar.org/climate-smart-villages#.WyO5cUxFxXI).

3 This is the Livelihoods as Intimate Government (LIG) (Carr, Citation2013) approach, discussed further in Section 4.

4 Men reported unfavourable season more frequently than women as a barrier to implementing information (Stats4SD, Citation2017).

References

- Amegnaglo, C. J., Asomanin, K., & Mensah-bonsu, A. (2017). Contingent valuation study of the benefits of seasonal climate forecasts for maize farmers in the Republic of Benin, West Africa. Climate Services, 6, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cliser.2017.06.007

- Archer, E. R. M. (2003). Identifying underserved end-user groups in the provision of climate information. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 84(11), 1525–1532. doi: 10.1175/BAMS-84-11-1525

- Arora-Jonsson, S. (2011). Virtue and vulnerability: Discourses on women, gender and climate change. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 744–751. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.005

- Blumenstock, J. E., & Eagle, N. (2012). Divided we call: Disparities in access and use of mobile phones in Rwanda. Information Technologies & International Development, 8(2), 1–16. doi: 10.4018/jiit.2012040101

- Caine, A., Dorward, P., Clarkson, G., Evans, N., Canales, C., & Stern, D. (2015). Review of mobile applications that involve the use of weather and climate information: Their use and potential for smallholder farmers. CCAFS Working Paper no.150. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/69496/CCAFSwp150.pdf;sequence=1

- Carr, E. R. (2008a). Between structure and agency: Livelihoods and adaptation in Ghana’s Central region. Global Environmental Change, 18, 689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.06.004

- Carr, E. R. (2008b). Men’s crops and women’s crops: The importance of gender to the understanding of agricultural and development Outcomes in Ghana’s Central region. World Development 36, 900–915. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.05.009

- Carr, E. R. (2013). Livelihoods as Intimate Government: Reframing the logic of livelihoods for development. Third World Quarterly 34(1), 77-108, doi: 10.1080/01436597.2012.755012

- Carr, E. R. (2014). Assessing Mali’s Direction Nacionale de la Météorologie Agrometeorological advisory Program: Preliminary report on the climate science and farmer use of advisories. Washington, DC: USAID.

- Carr, E. R., Fleming, G., & Kalala, T. (2016a). Understanding women's needs for weather and climate information in agrarian settings: The case of Ngetou Maleck, Senegal. Weather, Climate and Society, 8, 247–264. doi: 10.1175/WCAS-D-15-0075.1

- Carr, E. R., & Onzere, S. N. (2017). Really effective (for 15% of the men): Lessons in understanding and addressing user needs in climate services from Mali. Climate Risk Management, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2017.03.002

- Carr, E. R., Onzere, S. N., Kalala, T., Rosko, H. M., & Davis, J. ((2016b)). USAID / Mali climate change adaptation Activity (MCCAA) Behavioral baseline survey: Final synthesis report. Washington, DC: USAID.

- Carr, E. R., & Owusu-Daaku, K. N. (2016). The shifting epistemologies of vulnerability in climate services for development: The case of Mali's agrometeorological advisory programme. Area, 48(1), 7–17. doi: 10.1111/area.12179

- Carr, E. R., & Thompson, M. C. (2014). Gender and climate change adaptation in Agrarian Settings. Geography Compass, 8(3), 182–197. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12121

- Carter, M. R., & Barrett, C. B. (2006). The economics of poverty traps and persistent poverty: An asset-based approach. The Journal of Development Studies, 42(2), 178–199. doi: 10.1080/00220380500405261

- Chaudhury, M., Kristjanson, P., Kyagazze, F., Naab, J. B., & Neelormi, S. (2012). Participatory gender-sensitive approaches for addressing key climate change-related research issues: Evidence from Bangladesh, Ghana, and Uganda. Working Paper 19. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from https://ccafs.cgiar.org/sites/default/files/assets/docs/ccafs-wp-19-participatory_gender_approaches.pdf

- Cherotich, V. K., Saidu, O., & Omedo Bebe, B. (2012). Access to climate change information and support services by the vulnerable groups in semi-arid Kenya for adaptive capacity development. African Crop Science Journal, 20(s2), 169–180.

- CICERO. (2017). Evaluating user satisfaction with climate services in Tanzania 2014–2016: Summary report to the Global Framework for Climate Services Adaptation Programme in Africa.

- Clarkson, G., Dorward, P., Kagabo, D. M., & Nsengiyumva, G. (2017). Climate services for agriculture in Rwanda: Initial findings from PICSA monitoring and evaluation. CCAFS Info Note. Wageningen, Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from https://cgspace.cgiar.org/rest/bitstreams/145713/retrieve

- Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: What works? Journal of International Development, 28(3), 342–359. doi: 10.1002/jid.3210

- Coulibaly, J. Y., Birachi, E. A., Kagabo, D. M., & Mutua, M. (2017). Climate services for agriculture in Rwanda: Baseline survey report. CCAFS Working Paper no. 202. Wageningen, Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from www.worldagroforestry.org/downloads/Publications/PDFS/RP17108.pdf

- Coulibaly, J. Y., Kundhlande, G., Tall, A., Kaur, H., & Hansen, J. (2015b). What climate services do farmers and pastoralists need in Malawi? Baseline study for the GFCS adaptation program in Africa. CCAFS Working Paper no. 112. Wageningen, Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from www.wmo.int/gfcs/sites/default/files/projects/Climate%20Services%20Adaptation%20Programme%20in%20Africa%20-%20Building%20Resilience%20in%20Disaster%20Risk%20Management%2C%20Food%20Security%20and%20Health/WP%20112_Baseline%20Malawi.pdf

- Coulibaly, J. Y., Mango, J., Swamila, M., Tall, A., Kaur, H., & Hansen, J. (2015a). What climate services do farmers and pastoralists need in Tanzania? Baseline study for the GFCS Adaptation Program in Africa. CCAFS Working Paper no. 110. Wageningen, Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/67192/CCAFS_WP110?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Coulier, M. (2016). ACIS Project Baseline Survey Report – Vietnam. CCAFS-ICRAF-CARE.

- Coulier, M., & Wilderspin, J. (2016). ACIS project – Baseline report Cambodia. CCAFS-ICRAF-CARE.

- Cullen, A. C., Leigh Anderson, C., Biscaye, P., & Reynolds, T. W. (2018). Variability in cross-domain risk perception among smallholder farmers in Mali by gender and other demographic and attitudinal characteristics. Risk Analysis, 1–17. doi: 10.1111/risa.12976

- Davis, A., Tall, A., & Guntuku, D. (2014). Reaching the Last Mile: Best practices in leveraging ICTs to communicate climate information at scale to farmers. CCAFS Working Paper no. 70. Wageningen, Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/41731/CCAFS%20WP%2070.pdf

- Dercon, S. (1996). Risk, crop choice, and savings: Evidence from Tanzania. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 44, 485–513. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1154463 doi: 10.1086/452229

- Doss, C. (2001). Designing agricultural technology for African women farmers: Lessons from 25 years of experience. World Development, 29(12), 2075–2092. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00088-2

- Doss, C., & Kieran, C. (2014). Standards for collecting sex-disaggregated data for gender analysis: a guide for CGIAR researchers. Retrieved from https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10947/3072/Standards-for-Collecting-Sex-Disaggregated-Data-for-Gender-Analysis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Farnworth, C. R., Stirling, C. M., Chinyophiro, A., Namakhoma, A., & Morahan, R. (2017). Exploring the potential of household methodologies to Strengthen gender equality and improve smallholder livelihoods: Research in Malawi in maize-based systems. Journal of Arid Environments, 149(February 2018), 53–61. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2017.10.009.

- GSMA. (2012). Striving and surviving: Exploring the lives of women at the base of the pyramid. Australian AID; USAID. Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/GSMA_mWomen_Striving_and_Surviving-Exploring_the_Lives_of_BOP_Women.pdf

- Hampson, K. J., Chapota, R., Emmanuel, J., Tall, A., Huggins-Rao, S., Leclair, M., & Hansen, J. (2014). Delivering climate services for farmers and pastoralists through interactive radio: scoping report for the GFCS Adaptation Programme in Africa. CCAFS Working Paper no. 111. Wageningen, Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/65728/WP%20111.pdf

- Hansen, J. W., Mason, S. J., Sun, L., & Tall, A. (2011). Review of seasonal climate forecasting for agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Experimental Agriculture, 47(2), 205–240. doi: 10.1017/S0014479710000876

- Huyer, S. (2006). Understanding gender equality and women's empowerment in the knowledge society. In N. Hafkin, & S. Huyer (Eds.), Cyberella or Cinderella? Empowering women in the knowledge society (pp. 15–47). Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

- IPCC. (2012). Summary for Policy makers. In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, … P. M. Midgley (Eds.). Managing the risks of extreme events and Disasters to Advance climate change adaptation (pp. 1–19). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/special-reports/srex/SREX_FD_SPM_final.pdf

- IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (Eds.)]. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC. http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

- Jost, C., Kyazze, F., Naab, J., Neelormi, S., Kinyangi, J., Zougmore, R., & Kristjanson, P. ((2016)). Understanding gender dimensions of agriculture and climate change in smallholder farming communities. Climate and Development, 8(2), 133–144. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2015.1050978

- Kyazze, F. B., Owoyesigire, B., Kristjanson, P., & Chaudhury, M. (2012). Using a gender lens to explore farmers’ adaptation options in the face of a changing climate: Results of a pilot study in Uganda. CCAFS Working Paper No. 26. Wageningen, Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/23017/CCAFS-WP-26.pdf?sequence=1

- Maccini, Y., & Yang, D. (2009). Under the weather: Health, Schooling, and economic Consequences of early-life rainfall. American Economic Review, 99(3), 1006–1026. doi:10.3386/w14031 doi: 10.1257/aer.99.3.1006

- Manfre, C., & Nordehn, C. (2013). Exploring the Promise of information and communication Technologies for women farmers in Kenya. Washington, DC: USAID.

- Manfre, C., Rubin, D., Allen, A., Summerfield, G., Colverson, K., & Akeredolu, M. (2013). Reducing the gender gap in agricultural extension and advisory services: How to find the best fit for men and women farmers. Modernizing Extension and Advisory Services Discussion Paper. USAID Feed the Future.

- Martin, B. L., & Abbott, E. (2011). Mobile phones and rural livelihoods: Diffusion, uses, and perceived impacts among farmers in rural Uganda. Information Technologies & International Development, 7(4), 17–34.

- Meinke, H., Nelson, R., Kokic, P., Stone, R., Selvaraju, R., & Baethgen, W. (2006). Actionable climate knowledge: From analysis to synthesis. Climate Research, 33, 101–110. doi: 10.3354/cr033101

- Mittal, S. (2016). Role of mobile phone-enabled climate information services in gender-inclusive agriculture. Gender, Technology and Development, 20(2), 200–217. doi: 10.1177/0971852416639772

- Morduch, J. (1994). Poverty and vulnerability. The American Economic Review, 84(2), 221–225. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2117833

- Mudege, N. N., Chevo, T., Nyekanyeka, T., Kapalasa, E., & Demo, P. (2015). Gender norms and access to extension services and training among potato farmers in Dedza and Ntcheu in Malawi. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 22(3), 291–305. doi: 10.1080/1389224X.2015.1038282

- Mudege, N. N., Mdege, N., Abidin, P. E., & Bhatasara, S. (2017). The role of gender norms in access to agricultural training in Chikwawa and Phalombe, Malawi. Gender, Place & Culture, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2017.1383363

- Mwangi, E., Meinzen-Dick, R., & Sun, Y. (2011). Gender and sustainable forest management in East Africa and Latin America. Ecology and Society, 16(1), 17. Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss1/art17/ doi: 10.5751/ES-03873-160117

- Nath, V. (2006). How can ICTs positively influence the lives of disadvantaged women groups: Working towards the optimum ICT-impact model. In N. Hafkin & S. Huyer (Eds.), Cyberella or Cinderella? Empowering women in the knowledge society (pp. 191–206). Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Nelson, V., Meadows, K., Cannon, T., Morton, J., & Martin, A. (2002). Uncertain predictions, invisible impacts, and the need to mainstream gender in climate change adaptations. Gender and Development, 10(2), 51–59. doi: 10.1080/13552070215911

- Ngigi, M. W., Mueller, U., & Birner, R. (2017). Gender differences in climate change adaptation strategies and participation in group-based approaches: An intra-household analysis from rural Kenya. Ecological Economics, 138, 99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.03.019

- Nsengiyumva, G., Kagabo, D. M., & Gumucio, T. (2018). Exploring pathways for gender-responsive climate services in Rwanda. Poster presented at the Gender Summit-14 Africa, Kigali, Rwanda. Retrieved from https://ccafs.cgiar.org/publications/exploring-pathways-gender-responsive-climate-services-rwanda#.W6f3pfZFxXI

- Owusu, A. B., Yankson, P. W. K., & Frimpong, S. (2017). Smallholder farmers’ knowledge of mobile telephone use: Gender perspectives and implications for agricultural market development. Progress in Development Studies, 18(1), 1–16.

- Partey, S. T., Dakorah, A. D., Zougmore, R. B., Ouedraogo, M., Nyasimi, M., Kotey, G., & Huyer, S. (2018). Gender and climate risk management: Evidence of climate information use in Ghana. Climatic Change. doi: 10.1007/s10584-018-2239-6

- Perez, C., Jones, E. M., Kristjanson, P., Cramer, L., Thornton, P. K., Förch, W., & Barahona, C. (2015). How resilient are farming households and communities to a changing climate in Africa? A gender-based perspective. Global Environmental Change 34, 95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.06.003

- Poulsen, E., Sakho, M., McKune, S., Russo, S., & Ndiaye, O. (2015). Exploring synergies between health and climate services: Assessing the feasibility of providing climate information to women farmers through health posts in Kaffrine, Senegal. CCAFS Working Paper no. 131. Wageningen, Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/68141/CCAFS%20WP%20131.pdf?sequence=1

- Quinn, C. H., Huby, M., Kiwasila, H., & Lovett, J. C. (2003). Local perceptions of risk to livelihood in semi-arid Tanzania. Journal of Environmental Management 68, 111-119. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4797(03)00013-6

- Rao, K. P. C., Hansen, J., Njiru, E., Githungo, W. N., & Oyoo, A. (2015). Impacts of seasonal climate communication strategies on farm management and livelihoods in Wote, Kenya. CCAFS Working Paper No.137. Wageningen, Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Retrieved from https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/68832/CCAFS%20WP%20137.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y