ABSTRACT

Community-based adaptation (CBA) has become an increasingly popular mechanism for incorporating climate change adaptation into local development work. However, the term ‘community’ in CBA has been frequently used without rigorous reflection on its own meaning, boundary and governance, assuming that a moral license is intuitively granted. The article sets out to critically examine, through a study of the UNDP-GEF Small Grants Programme (SGP), how the concept of community is framed within the paradigm of CBA in Ethiopia and to what extent Ethiopian peasants articulate a shape of community that they consider they belong to. This article contributes to the field of community development in general, and specifically CBA, by exploring a fundamental difference between the governmental construction of community and the practices of community governance by citizens on the ground. Overall, I argue that communities are neither an actor nor a place, but the outcomes of a complex set of power-laden relationships, built on the unique mix of norms, customs, history and private interests. Community boundaries are therefore fluid with heterogeneity inside, and the individual perceptions of the community tend to be idiosyncratic. However, the definition of a community is frequently imposed upon in CBA practice, rather than generated by the groups themselves.

1. Introduction

Community-based adaptation (CBA) has become an increasingly popular concept for incorporating climate change adaptation into local development work in recent years (Reid, Citation2016). This trend is consonant with the rise of the term ‘community-based’ as a panacea for many developmental challenges encountered in climate change adaptation (Forsyth, Citation2013). Despite significant variation in structure and function, CBA schemes are, in general, designed to bring together the long-standing ideas of participatory development and the more recent conception of resilience and thereby finance and implement locally identified adaptation measures in response to climate change (Dodman & Mitlin, Citation2013; Ensor et al., Citation2018). Over the past two decades, this approach has spawned a growing variety of projects across the globe, particularly where the adaptive capacity is highly dependent on people’s livelihood strategies such as in Ethiopia (Dodman et al., Citation2010).

Today CBA is commonly imagined as a ‘magic bullet’ that ascribes adaptive capacity to a community in situ, based on the assumption that the community inherently has the skills, knowledge and networks to promote correct measures for their own environment and livelihoods. As a level of project governance, the community is perceived as practical, effective and even just in the field of international development (Huq et al., Citation2017). As IIED senior fellow Saleemul Huq and co-authors describe in the introduction to their collection of CBA case studies titled Enhancing Adaptation to Climate Change in Developing Countries Through Community-Based Adaptation: Think Globally and Act Locally:

CBA is a participatory, community-led and environmentally sustainable approach to climate change that seeks to strengthen the resilience of poor and vulnerable communities. The novelty of CBA is not only that it addresses the urgency of adaptation but also that it does so by placing local communities at the centre of adaptation decisions, needs and priorities thus recognising that community knowledge constitutes a more sustainable foundation for climate change adaptation and resilience. (Citation2017, p. 2)

Given the above considerations, the current paper offers an analysis of the SGP projects in rural Ethiopia regarding how the concept of community is framed and practised in the context of CBA. To this end, it seeks to address why the definition of a community is frequently imposed upon in CBA practice, rather than generated by the groups themselves. Section 2 reviews the literature to think critically about how the community is conceptualized in community development in general and in CBA specifically. Section 3 then outlines the research methods used for this study. This is followed by an analysis of the intention of the Ethiopian government to implement the SGP projects at the kebelle level from the historical and governance perspectives in Section 4, and how this intention works through a complex set of power-laden relationships around the locality in the Ethiopian peasantry in Section 5. The last section offers conclusions and an agenda for future research.

2. Rethinking the production of communities

How is ‘community’ being considered to promote and carry out adaptation measures in CBA? In this section, I address the need to think critically about how the community is conceptualized and practised in community development in general and in CBA specifically. First, communities are products of complicated sets of social, cultural, political and economic relationships. Second, the definition of a community is frequently imposed upon in CBA practice, rather than generated by the groups themselves. It is important to understand a critical perspective on the community in community development through contextually grounded academic research findings in order to reflect on the better implementation of CBA in practice.

Normative spaces for constructing community have emerged as a target of international development policies to provide a ‘good and appropriate’ local site for development practice (Norris et al., Citation2008). In line with this trend, the current framework of CBA aims to set up a locality to address how climate change affects its assets, capacities and environment (Ayers & Huq, Citation2009; McNamara & Buggy, Citation2017). Its difference from other standard adaptation projects is not in the intervention itself, but in the way the intervention is conceived, negotiated and implemented (Ensor & Berger, Citation2009). CBA requires development funders and practitioners to engage with indigenous knowledge, networks and practices of coping with various hazards in a locality. Communities are expected to play an important role in this process, and this is described as ‘putting communities in the driving seat’ in various kinds of CBA events and documents (Gogoi et al., Citation2014; Sharma, Citation2014; Sheikh, Citation2012; Strasser et al., Citation2015). It is widely assumed that communities have natural capacities for self-management and that this just has to be restored by manoeuvring them into position (McNamara et al., Citation2020).

In community development, however, administrative definitions of community are frequently imposed by practitioners or policymakers rather than constructed by the groups themselves (Jewkes & Murcott, Citation1996; Matarrita-Cascante & Brennan, Citation2012). Epistemological issues of defining community are inadequately addressed in much community development research as it is assumed that communities are simply geographical entities where people exchange goods and services and gives little regard to their cultural complexity (Ensor, Citation2011; Mosse, Citation1999). This tendency follows attempts to define community in terms of ‘common-being’ rather than ‘being-in-common’ (Nancy, Citation1991 in Welch & Panelli, Citation2007). Common-being is devised for administrative convenience, not considering the individual experience of interventions associated with singular being-in-common (Panelli & Welch, Citation2005). This simplistic approach is problematic and potentially dangerous. Projects fitting in this form of community development are mostly interested in making changes to the community’s socio-political structures and institutions to engage with participatory and democratic contents. On the ground, however, communities are envisaged through ‘the materiality of communities, their histories, their institutional relationships, and the political opportunity structures they can access’ (Staeheli, Citation2008, p. 36). The community does not emerge in a political vacuum but is continuously constituted, negotiated and compromised through the exercise of power (Beckwith, Citation2022; Perreault, Citation2003; Voydanoff, Citation2001). In the context of CBA, the community is also neither a given entity at a fixed scale nor comfortably uniform and complete (Yates, Citation2014). Rather than being a unified product, the community is a process defined by contradictions and multiple perspectives as well as elite control (Mansuri & Rao, Citation2004). However, administrative definitions of community are often built to brush off any contested socio-political relations and to conceal the various levels of vulnerability in order to streamline development interventions (Cleaver, Citation2001; Matarrita-Cascante & Brennan, Citation2012).

Community is neither an actor nor a place. ‘They are, however, outcomes that affect and constrain future possibilities’ writes James DeFilippis (Citation2001, p. 789). A large group of scholars have explored how and to what extent community is formulated through a continual process of fabricating and refabricating multiple voices both inside and outside (Cloke et al., Citation1997; Ensor et al., Citation2018; Kothari, Citation2001; Li, Citation2007; Mackenzie & Dalby, Citation2003; Secomb, Citation2000). Considerable progress was made in deconstructing the concept to identify the production, operation and critique of community. In particular, geographers have extensively discussed that communities are products of complicated sets of social, political, cultural and economic relationships, presenting a wide range of diversity in terms of shape, function and capacity (DeFilippis, Citation2001; McNamara & Buggy, Citation2017; Nightingale, Citation2002; Panelli & Welch, Citation2005; Perreault, Citation2003; Staheli & Thompson, Citation1997). Communities are relational, concerned with the qualities of human relationships and social ties (Gusfield, Citation1978). However, communities are neither places where individuals perform as part of a unified group nor reflective of the existence of common bonds between individuals (Panelli & Welch, Citation2005). This is not only true of the production and reproduction of communities in general but is also true of the interventions made in the name of community interest in community development (Watts & Peet, Citation2004).

Community boundaries are therefore fluid (Manderson et al., Citation1998). The contradictory notion of community is that community still exists even when heterogeneity and disagreement are present inside (Panelli & Welch, Citation2005). There is a wide range of empirical studies problematizing the understanding of communities as harmonious, inclusive groups of people exhibited (Agrawal et al., Citation2008; Mansuri & Rao, Citation2004; Panelli, Citation2001; Panelli et al., Citation2006; Sharma & Nightingale, Citation2014). No community solely operates as a function of the internal attributes of people who belong there. Community is not simply a synthesis of the characteristics of those within them but the outcomes of a complex set of power-laden relationships both internally and externally, built on its unique mix of norms, customs, history, power dynamics and the environment (Cavaye & Ross, Citation2019; DeFilippis, Citation2001; Heller, Citation1989; Taylor, Citation2015; Yates, Citation2014). A system of parliamentary democracy is a telling example that practically exercises collective political power by institutionalizing the process of representing different constituencies and of entailing both internal and external contestations into policymaking. In this context, ‘governing through community’, as Tania Li (Citation2007) describes in The Will to Improve, is not simply concerned with imposing state control over a given socio-spatial arena. Rather, it is a way of making collective existence which means that issues are problematized in terms of features of communities and that solutions take the form of acting upon power dynamics across different levels of governance (Li, Citation2007). These power dynamics and heterogeneity within and between social groups are inevitable to the advantage of some and discriminate against others and often lead to conflicts over resources such as land and water. However, these aspects are often brushed over in development practice (Beckwith, Citation2022; Chu, Citation2018; Cleaver, Citation2001; Page, Citation2002).

Difference in the understanding of the term ‘community’ is revealed when the imposed definition of community is tested in the course of interventions against the notions of community of those envisaged as community members (Jewkes & Murcott, Citation1996). Among indigenous communities, appropriate definitions of community vary depending on context such as history, politics, gender, access to services and so on. This is a unique challenge when it comes to climate change adaptation because CBA is designed as a bottom-up approach that aims to increase the participation and agency of communities in the adaptation process. CBA considers effective adaptation as a community-led process that co-produces adaptation strategies and ensures the participation of different stakeholders in decision-making processes (McNamara & Buggy, Citation2017; Singh et al., Citation2021). However, it only challenges top-down and bottom-up binaries at the level of adaptation governance, arguing that co-producing adaptation solutions can facilitate more effective adaptation, not considering intracommunity challenges and heterogeneity.

Community is a paradox at the heart of CBA. Community is assumed to have natural capacities for self-management whilst the capacities need to be refined. Community is the key to providing a ‘good and appropriate’ local site whilst the locality requires approval from external experts. Community is something to be achieved whilst the achievement is different from the community that already exists (Li, Citation2007). To contain this paradox, CBA projects often attempt to

elide what currently exists with the improved versions being proposed, making it unclear whether talk of community refers to present or future forms. They locate the model for the perfected community in an imagined past to be recovered, so that intervention merely restores community to its natural state. Or they argue that they are not introducing something new, merely optimizing what is naturally present. (Li, Citation2007, p. 232)

This paradox of community indicates disparities between an idealized form of community ‘in the driving seat’ and actual community governance practised on the ground. These disparities frequently create space for government intervention and convince development funders and practitioners that they still have work to do – from defining a geographical space for constructing communities to directing communities on how they should look like.

In popular and policy terms, the community continues to be invoked as a vehicle via which numerous social and political challenges might be overcome (Welch & Panelli, Citation2007). In CBA, there is a rationale for the need to act in order to construct community, and this need may operate by individuals as well as by certain interest groups such as development funders, policymakers, administrators and local politicians. Hence, recommendations simply to replace the focus on community with a politics of difference will be easily ignored in the practical world of development decision-making (Matarrita-Cascante & Brennan, Citation2012; McNamara & Buggy, Citation2017). Those interest groups together with academics seeking research contracts will continue to return to the frustrating business of investigating easily-manageable communities as long as ‘community is an understandable dream’ (Young, 1990, p. 300 in Panelli & Welch, Citation2005).

Understanding communities, in this paper, is about questioning governance, authority and representation among multiple and contradictory social groups and alliances. It is about revealing different power dynamics and how these dynamics affect the decision-making processes of a locality (Chu, Citation2018; Kothari, Citation2001). Reconceiving the community as a product of complicated sets of the social, cultural, political and economic relationship, rather than as an actor at a fixed scale, may complicate our understanding of CBA. Communities are, however, continuously fabricated and refabricated based upon the intersection of diverse flows of power-laden relationships across scales. The quality of these relationships is determined by characteristics such as history, culture and politics and in turn shapes the way the adaptation interventions are conceived, negotiated and implemented, not merely restoring the community to its natural state in isolation (Ensor, Citation2011). In other words, the way community is conceptualized determines the way the adaptive capacity of the community is developed. Taking this as its point of departure, this paper reviews the production of communities in CBA with the cases of the SGP project in rural Ethiopia.

3. Research methods

Drawing on the literature review and data collected from the field research, I examine how the concept of community is framed and enacted by the Ethiopian government and to what extent Ethiopian peasant farmers envisage, describe and articulate a shape and type of community that they consider they belong to and how these communities are contested in the context of CBA. This research has been reviewed by and received ethics clearance from University College London (UCL) through the UCL Research Ethics Committee (Reference number: 4996/001), and the research was conducted according to the given guideline.

Established in 1992, the SGP has been supporting community-led initiatives that aim to combat environmental problems around the world. The SGP has awarded grants to over 14,500 communities in over 125 countries worldwide (SGP, Citation2019). Funded by the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) and operated by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the SGP is a well-known CBA practice that provides financial (up to USD 50,000) and technical support directly to local villages during a project period of up to two years, claiming that the local ownership of development projects is key to achieving a higher level of adaptive capacity to climate change (Fenton et al., Citation2014; SGP, Citation2019).

The research is based on qualitative research involving the review of relevant literature and project documents, 8 months of participant observation, 7 focus group discussions and 73 semi-structured interviews (49 men and 24 women) with peasant farmers, government officials and SGP management personnel. Interviewees are all adults between ages of 18 and 55. I did not ask for their ethnicity for ethical reasons. Research participants were mostly recruited through local institutions and then a snowball technique was employed. The field research was conducted during my PhD research, mainly in 2014. The research was conducted in two rural villages – one in the Amhara region and one in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ (SNNP) region – to compare northern and southern Ethiopia. An initial four-month period of field research was spent in a kebelle in the Amhara region and the last four months in a kebelle in the SNNP region – which cannot be named for ethical reasons.

By employing these methods, I seek to better understand the intention of the Ethiopian government to have the SGP projects at the kebelle level and how the existing socio-political structures and institutions are contested around the locality. Kebelle is the lowest administrative unit in Ethiopia with an average population of 4000–6000 and is often understood as a village by international development practitioners. About the concept of community, I first asked research participants to introduce their kebelle, woreda and community, and describe people that they are (and not) close to, usually talk to and do everyday activities with (e.g. other gotts or kebelles). If I found they seem to be interested and enthusiastic to discuss further, I asked them about their definition, perception and understanding of community in the context of the SGP projects. All interviews were conducted in Amharic, an official and widely spoken language of Ethiopia. My Amharic was only fluent enough to carry out the first half of an interview, and the second half was interpreted by research assistants.

4. The political production of communities in Ethiopia

The introduction of CBA in Ethiopia is part of the master plan of decentralization. The plan is ostensibly designed to devolve power and authority away from the central government towards the local governments. In line with this plan, the implementation of the SGP projects in Ethiopia is marked by the advisory role afforded to external actors, no involvement of the government, and the daily management responsibilities placed in the hands of individuals elected within a local village (Chung, Citation2017). At the same time, the story of decentralization in Ethiopia is typical of countries in transition (Mehret Ayenew, Citation2002; Teferi Abate, Citation2004). There is a gap between the constitutional provisions of services and the practice of these provisions. The Ethiopian constitution promotes the decentralized governance system throughout its territory while the ruling political party – Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) between 1995and 2019 and the Prosperity Party since 2019 – practically controls the local municipalities through its party members (Mehret Ayenew, Citation2002). The federal policies are generally respected, but its principles get easily compromised by the working practices of the policies at the lower level of governance.

This has been the case with CBA. The CBA projects aim to enhance the role of ‘communities’ in climate change adaptation through promoting local values, knowledge and networks (Huq et al., Citation2017). Reconceiving the community as a product of complicated sets of power-laden relationships, rather than as an actor at a fixed scale, may complicate our understanding of CBA. However, success in climate change adaptation therefore highly depends on how the communities are conceived, constructed and practised. The Ethiopian government, however, has unilaterally determined the administrative definition of community as kebelle and imposed it on the SGP projects. This establishment has created a degree of difference between government and citizens in understanding the production, boundary and governance of the communities. It is important to understand this differentiation because the imposition of certain managerial scales in development practice often has political intentions and subsequently reinforces or alters the existing geometry of power by strengthening the control of some while disempowering others (Swyngedouw & Heynen, Citation2003), which in turn shapes development outcomes. To this end, this section examines the role of kebelle as the political legacy of the Ethiopian governance system as well as the current multi-layered structures of governance in rural Ethiopia.

From a view of the Ethiopian government, the administrative definition of community is kebelle. The role of kebelle in Ethiopia’s governance structures is highly important, particularly for the federal government to keep its influence on rural hinterlands where the capacity of the government is limited to reach. The concept of kebelle was initially implemented by the ‘Provisional Military Administrative Council’, known as the Derg, which ruled Ethiopia between 1974 and 1991, to organize every household in rural hinterlands. It was designed to carry out the rural development and land reform programmes and to ensure that taxes and other dues are properly collected (Young, Citation1997). The kebelle system was, however, quickly transformed into a highly effective apparatus of control and repression by the regime and started working as the extended arm of government to instil socialist ideas and political orders in the peasantry (Bahru Zewde & Pausewang, Citation2002). The system was also used to keep any grassroots and potential ‘anti-revolutionary’ activities under surveillance. Even after the EPRDF came to power, the kebelle system remained as the lowest level of government, which consolidates and extends the influence of the party throughout the country. It is claimed that one of the main objectives of the kebelle system is still to keep an eye on rural villages and to effectively disseminate government propaganda (Vaughan & Tronvoll, Citation2003). Ethiopian citizens are well aware of this security apparatus of the system from their experience and how their relations with the kebelle office may mediate access to resources such as land, improved seeds, fertilizers and health services (Chung, Citation2017).

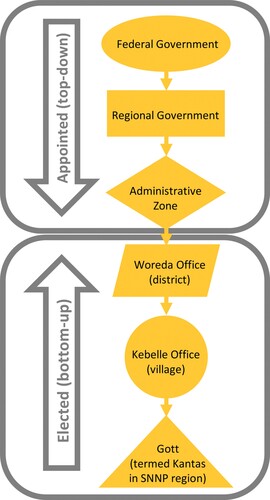

Decentralization in Ethiopia officially aims to modernize the fiscal and administrative systems across all levels of government and to deliver public services to citizens more effectively (Aalen, Citation2002; Abbink, Citation2011). As shows, Ethiopia is a federal republic with five administrative (federal to kebelle) and one local (gott) tiers of government. Down to the zonal level, cabinets are appointed by upper government officers, and from the woreda level downwards, representative councils are directly elected by the local population. However, being elected does not necessarily secure administrative independence, particularly at the woreda and kebelle levels, due to the financial and political relationships between the tiers, which will be teased out below. The process of decentralization is mainly focused on the delegation of administrative departments from federal, regional and zonal to woreda and kebelle governments, especially aiming to urbanize rural hinterlands (Yilmaz & Venugopal, Citation2008). In particular, the four most populous regions – Amhara, Oromia, SNNP and Tigray regions – of Ethiopia have been prioritised and received more financial support from the federal government to streamline this transition of responsibilities (Aalen, Citation2002).

Figure 1. Governance structures of Ethiopia (Chung, Citation2017).

The woreda governance system follows a form of the tripartite structure by which one head of administration, a council executive committee, and government bureaus are regulated (Yilmaz & Venugopal, Citation2008). While the elected head has out-and-out power as a chairperson, the council committee is comprised of three representatives from each kebelle under its jurisdiction as well as bureau chiefs. One of the main constitutional power and duties of the woreda is to prepare and execute budgets for both the woreda itself and kebelles within it on the basis of the local taxes and levies collected (Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2015).

The kebelle administration does not have the same institutional capacity as woreda offices although this is the first administrative tier of government that most ordinary Ethiopian citizens have contact with on an everyday basis (Chung, Citation2017). This is because the kebelle is not a budgetary unit. The woreda government receives block grants from a higher level of administration. This is to address the vertical imbalance in revenue versus expenditure between the federal and local governments, and this block grant is practically the most important source of income and is distributed based on population, levels of poverty as well as regional tax efforts (Watson, Citation2006).

In Ethiopia, revenue collection is still centralized, whereas expenditures are decentralized, which gives the federal government superior financial leverage overspending of local governments. In this context, any development plans at the kebelle level that require budgets need to be approved by the woreda office although the kebelle office is still accountable for preparing development plans, ensuring the local tax collection, organizing local labour and managing administrative tasks (Chung, Citation2017). This is why, despite the ambitious promotion of decentralization, most kebelle offices in Ethiopia are still heavily dependent on higher levels of government and has limited capacity to manoeuvre with administrative autonomy.

In many cases, the kebelle’s budgets are just enough to cover the salaries of its officers, and this condition undermines the managerial independence of the kebelle administration. As a Kebelle officer remarks,

This kebelle really needs electricity and roads to markets. We have been asking the woreda office for them for a long time. I came to this village three years ago. My predecessor told me that he had also asked the woreda many times. Sometimes I pay out of my own pocket for stationery in the office. I also do farm and animal husbandry for a living.

A woreda officer agrees on this situation when he explains,

It has been always like this. We have 17 kebelles and they all have similar problems. As a woreda in rural hinterlands, we have very limited budgets. Eventually, we will try to deliver what they have requested, but it takes time.

During the research, it was found that kebelle officers and leaders spend more time in the woreda office than in their own office and behave carefully and cautiously when they are with the woreda officers, speaking much less.

This circumstance is one of the reasons that the SGP has agreed with the Ethiopian government on implementing the SGP projects at the kebelle level. An SGP practitioner explains,

That is why we have decided to implement the SGP projects at the kebelle level. After discussing with the government and following the previous projects, we agreed that the kebelle has government officers who take responsibilities and assist us [development practitioners] while suffering from the lack of financial resources.

However, providing funding for a limited period does not necessarily bring institutional autonomy to its recipients. On the ground, many kebelles competed with each other within a woreda to host the SGP projects and, due to their limited capacity, needed help from the woreda officers in preparing the SGP project applications, which include a list of project activities with priority. The extent the woreda officers were involved in developing the application varied, but it was found that their understanding of the application process was more comprehensible than those of the kebelle officers in many instances. Even during the project period, a couple of woreda officers were regularly invited to the SGP meetings and often paid per diems. Their attendance had a great influence on local decision-making processes, particularly when some kebelle members opposed specific project activities that the kebelle leaders and officers previously agreed on in the project applications such as the closure of the community forest which is further described in the next section.

At the same time, each kebelle has rather complex governance structures in which formal and informal institutions are intricately interwoven (Vaughan & Tronvoll, Citation2003). Most kebelles operate a governance system that is made up of an elected head of the kebelle council, a council committee and a social court with three judges – mostly local priests – as well as one government officer and one police officer who are appointed by the woreda (Poluha & Rosendahl, Citation2012). The council committee members are representatives of gotts (neighbourhood), political party members, teachers, militias and state-initiated associations (e.g. women’s leagues, one-to-five networks and youth associations) (Chung, Citation2017). In particular, the ruling political party members are recognized as government messengers and usually work as leaders of state-initiated associations and often become the head of the kebelle.

Below the kebelle level administration, the governance structures vary depending on the region with no paid government officer. For example, there is no formal sub-kebelle structure in the Oromia and Afar regions whereas the kebelle is sub-divided into gotts (called kantas in the SNNP region) in other regions including Amhara and SNNP regions where this research took place. In a gott, there is generally one elected leader with two deputies appointed by the leader with an average of 30–60 households (Chung, Citation2017). They, mostly men, represent the interests of the gott at the kebelle level meetings. Compared to the kebelle system, it is in a shape of kinship-based networks or close neighbourhoods that often work together for their livelihoods (Tronvoll & Hagmann, Citation2012). A farmer describes his gott by saying, ‘My brother lives over there with his wife and three children. We often work on our bamboo tree farms together. We often eat together. We are from the same father’. Ordinary villagers casually gather through these informal and kinship-based institutions and actively exchange their opinions and information. However, their voices are selectively addressed in the kebelle systems since its council committee is usually led by the kebelle leaders, who can be characterized as local elites that tend to be older, richer and more educated with better access to the woreda offices. It was found that the SGP project and activities that many villagers are interested in are widely discussed within the kebelle although important decisions are still made by these elite groups in support of the kebelle and woreda officers.

There are different types of community practised by different activities of the SGP project, and the communities are the outcomes of a complex set of power-laden relationships, both internally and externally (DeFilippis, Citation2001). Community is not a place where individuals perform as part of a unified group, and common bonds between individuals are fluid, built on its unique mix of norms, customs, history and private interests (Ensor et al., Citation2018; Panelli & Welch, Citation2005). This is not only true of the production of communities in general but also true of the interventions made in the name of community interest in CBA (Ensor, Citation2011; Watts & Peet, Citation2004). However, built on the political legacy of the Ethiopian governance system, the administrative definition of community was determined as kebelle and imposed on the SGP projects. This imposition may have reinforced the existing geometry of power relations and local perception and roles of kebelle in community governance in the locality. Epistemological issues of community governance are inadequately addressed in the SGP project in Ethiopia as it is assumed that communities are simply administrative entities where people exchange goods and services and gives little regard to their political and institutional complexity.

5. Individual perceptions of community in rural Ethiopia

The ability to identify what kind of assistance is needed and who could provide it are key components of subsistence farming. The Ethiopian peasant farmers particularly need this ability to survive in a country where the government lacks the capacity to provide basic services to its own people. The country’s previous agrarian crises were mostly imposed from outside of the peasantry such as the consequence of contradictions in state policy, the politicization of agriculture and agricultural reforms, and the redefinition of state-peasant relations (Clapham, Citation1990; Dessalegn Rahmato, Citation2009). Relatively speaking, what has not received much consideration is how these peasant farmers are organized, particularly at which scale they build resilience against the potential threats to their livelihoods. In Ethiopia, there are both open-ended and programme-specific definitions of community due to the widespread popularity of CBA and a multitude of development projects at the local level. Through the promotion of decentralization, the different principles of community development are entrenched in the way peasant farmers are organized and controlled by the state depending on the region. This spills over into their identities and perceptions of their own communities. Hence, this section is focused on individual descriptions of community, based on the lived experience of Ethiopian peasant farmers.

From a linguistic point of view, a word ‘community’ in Amharic – the official language of the Ethiopian state – is understood differently depending on where it is used. Mahibereseb is the word for ‘community’ and is originated from the word ‘society’, mahiber, and the word ‘socialism’, mahiberesebawinet (Chung, Citation2017). Both words were introduced during the Derg regime. This polysemy is also found in Swahili – the Bantu language spoken in East Africa – for instance. Jamil refers to both community and society, and the meaning of society generally springs to mind first in the rural peasantry. It is also the case in Ethiopia that many rural peasant farmers, particularly in the northern part, do not catch the word ‘mahibereseb’ instantly but do understand the word ‘mahiber’ without any clarification (Chung, Citation2017). Due to this language issue, many research participants understood CBA as a ‘society-based’ or ‘civil society-based’ adaptation project, which led people to have different understandings of whom they work with for the project. A local priest suggests that if the SGP project was introduced as ‘kebelle-based’, it might have caused less confusion on the ground as ‘mahibereseb’ is not a very commonly used word, particularly in northern Ethiopia.

Community easily becomes a problematic category in a country where the top-down hierarchy is firmly established. Most people in rural Ethiopia regard whatever comes from outside as yebalal akal (‘orders from above’ in Amharic) (Vaughan & Tronvoll, Citation2003) including any messages, people or even development projects. A local leader of a women’s league shows that she thinks that the SGP project was implemented by the state when she says, ‘If there is another [SGP] project coming, I would like to ask our government for a medical centre and electricity’. Moreover, a leader of a gott confuses the state with the political party when he says,

We meet regularly on every Sunday and discuss our problems. If the party [EPRDF] does not lead our kebelle, show the way to go and become a light of us, I do not think organising people and solving the problems is possible. If the state helps, nothing will be difficult.

It was found that the principle of CBA – ‘putting communities in the driving seat’ – was more commonly shared and practised by the elite and youth association members who actively seek to engage in the kebelle-level activities rather than ordinary villagers.

Community is more institutionally understood when it comes to a specific programme. A kebelle officer defines community as ‘the organisational status such as women’s leagues and youth associations’. This perspective focuses on a network of individuals who interact within formal and informal institutions (Gusfield, Citation1978). A former leader of a women’s league also explains, ‘I was the leader of women’s league. The community is a group of people that gather and work together like a women’s league. That is my community’ and then adds, ‘The women’s league is now more active than my time. It is good to be together. Women should participate in the meetings and speak in public without being shy’. This is related to community as collective power, referring to a group of people who share similar interests as a potential lever for social change and carry out institutionally organized activities together (Heller, Citation1989).

This perception of community reminds us that community can be used as a tool of exclusion as well as inclusion. Opposing a particular developmental activity is sufficient enough to create conflicts in the political sphere by drawing a distinction between ‘the friend’ and ‘the enemy’ (Schmitt, Citation1932). For instance, in the Amhara region’s project, the youth association strongly opposed the closure of community forest, which was one of the highly prioritized activities in the SGP. Its members tend to have less private land and need access to the forest to feed their livestock. Their opinions were not heard in the kebelle meetings, and those who spoke out on behalf of the youth association were later beaten up by the police officer and became hostile to the entire SGP project. In the meantime, some of the youth members, who are the political party members and/or the children of the elite, remained active in other project activities although they stood up together against the closure of community forest. A youth association member explains,

The youth groups are marginalised and disadvantaged in our kebelle and we are subjected to various financial problems. We have inherited very small plots of land, and many of us are unemployed. There are some of my friends who have already migrated to cities in search of other jobs.

In contrast, a kebelle leader complains, ‘There are some youngsters who disturb our kebelle. We agreed the ideas of development and no one opposed them except those youngsters’.

The individual perception of community is also influenced by personal milieu and aspirations and is variable depending on the situation (Heller, Citation1989). Dining with friends and family is, for instance, an important part of Ethiopian culture (Howard, Citation2010). A young man who has no private land and so needs to go to cities regularly such as Addis Ababa for manual labour says, ‘Community? I do not have much education. But, for me, as a member of the Amhara ethnic group. They are my supporters’ and adds, ‘Addis is a big city. People are from everywhere and I don’t know them. Community means a group of people who eat and drink together. I often eat alone there’. He felt alienated in Addis Ababa – a melting pot of diverse ethnic groups as the country’s capital and has a population of more than 10 million. His definition of community shows that communities are relational, concerned with the qualities of human relationships and social ties (Gusfield, Citation1978) and that resource sharing and mutual support are representative of intimate relationships.

There is difference in the perception of community between northern and southern Ethiopia. As illustrates, most interviewees consider the scale of community as either gott or kebelle in the northern part. This is partially because northern Ethiopia is historically a kinship-based society in which people used to share the corporate ownership of land (Pausewang, Citation1990). Moreover, the concept of kebelle has been enforced by the Derg and then the EPRDF over the last 40 years. In particular, there was a tendency for those who have social and political positions in the kebelle or gott such as leaders, priests and militias to choose kebelle as the scale of community and for ordinary citizens to choose gott. The reason is that those with the positions generally have a greater chance of having contact with kebelle officers and policemen and of discussing issues at the kebelle level meetings.

Table 1. Administrative scale of community in local people’s perception/Unit: persons (Chung, Citation2017).

In contrast, fewer interviewees consider gott as the scale of community in southern Ethiopia. The southern part is traditionally clan-based societies with more than 50 ethnic groups. After being subsumed by the Abyssinian Empire in the nineteenth century, administrators were sent to the southern region to replace local clan leaders as its land is more fertile and has better climate for agriculture (Pausewang, Citation1990). They later established peasant associations run by the state during the Derg regime. This history of being colonized, albeit internally, has shaped the general perceptions of people. During the focus group discussions, most participants chose the country as the scale of community while a few opted for family or gott. This result is significantly different from the interview answers. Attendees at the focus group discussions included the kebelle officers, local leaders and militias, and this might have influenced their decision. This shows how a milieu of southern Ethiopia has been shaped by the internal colonization and has in return featured people’s ethos and behaviour in public.

In summary, the individual perceptions of community in the Ethiopian peasantry are found to be idiosyncratic, shaped by not only personal milieu and aspirations but also social and historical dimensions of society. The research addresses not only how the Ethiopian peasant farmers envisage, describe and articulate a shape and type of community that they consider they belong to but also the sense of community that shapes their behaviour in public. It demonstrates that their perceptions of the community are varied and tend to be different among villagers in the context of CBA, depending on how the SGP project and its particular activities affect their livelihoods.

The imposition of certain managerial scales may have reinforced the existing geometry of power, deteriorating the adaptive capacity of some youth association members in the northern village. Such practice in CBA imposes the contradictions between the rationality of government and their ability to regulate dynamics of social relations that open the terrain of contestation and debate between people with different interests and claims, ultimately shaping development outcomes. This differentiation certainly affects the adaptive capacity of different social groups as some youth association members left the village, heading to cities in search of other jobs.

6. Conclusion

In this article, I contribute to the field of community development in general, and specifically CBA, by exploring a fundamental difference between the governmental construction of community and the practices of the community by citizens on the ground, through an analysis of the SGP projects in rural Ethiopia. It is important to understand this differentiation because the imposition of certain managerial scales in development practice often has political intentions and subsequently reinforces or alters the existing geometry of power around the locality by strengthening the control of some while disempowering others, which in turn shapes development outcomes. Commonly, epistemological issues of defining community are inadequately addressed due to the assumption of considering communities as simply administrative entities with little regard to their political and institutional complexity.

The approach adopted in this article not only presents political accounts of CBA but also offers an original perspective on the structure called ‘a community’ in development practice. The individual perceptions of community in the Ethiopian peasantry are found to be idiosyncratic, shaped by social, political and historical dimensions of society. However, the administrative definition of community was determined as kebelle and imposed on the SGP projects by the Ethiopian government, built on the political legacy of its governance system. Such practice in CBA imposes the contradictions between the rationality of government and their ability to regulate dynamics of social relations that open the terrain of debate between citizens with different interests. This imposition reinforces the existing geometry of power and undermines the principles of CBA since Ethiopian citizens are well aware of this security role of the kebelle and how their relations with it may mediate access to resources.

In popular and policy terms, the community continues to be invoked as a vehicle via which numerous developmental challenges might be overcome. Governance of CBA organizes climate change adaptation by drawing on indigenous knowledge, networks and practices of coping with various hazards in a locality. Without understanding a complex set of power-laden relationships within the community, the current SGP framework may further marginalize those who are already vulnerable and exacerbate the inclusion and exclusion of different community members, consequently deteriorating their adaptive capacity to climate change. Climate change has unequal impacts, and CBA projects that aim to manage these impacts need to be aware of these unequal vulnerabilities that are caused by the complicated sets of social, cultural, political and economic relationships around the communities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jin-ho Chung

Jin-ho Chung is Research Associate of the Transport Studies Unit at the University of Oxford. His research focuses on climate change adaptation, human migration/mobility, urban development and social equity. Trained in political economy and resilience studies, Jin-ho's approach has been interdisciplinary and collaborative, drawing from collaborations with academics, policymakers and civil society, aiming at improving the relationships between science, policy and practice. Jin-ho completed his PhD in Geography at University College London (UCL).

References

- Aalen, L. (2002). Ethnic federalism in a dominant party state: The Ethiopian experience 1991-2000. Chr. Michelsen Institute, Development Studies and Human Rights.

- Abbink, J. (2011). Ethnic-based federalism and ethnicity in Ethiopia: Reassessing the experiment after 20 years. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5(4), 596–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2011.642516

- Agrawal, A., McSweeney, C., & Perrin, N. (2008). Local institutions and climate change adaptation. Social development notes, 113. World Bank.

- Ayers, J., & Huq, S. (2009). Community-based adaptation to climate change: An update. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

- Bahru Zewde, & Pausewang, S. (2002). Ethiopia: The challenge of democracy from below. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Beckwith, L. (2022). No room to manoeuvre: Bringing together political ecology and resilience to understand community-based adaptation decision making. Climate and Development, 14(2), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2021.1904811

- Cavaye, J., & Ross, H. (2019). Community resilience and community development: What mutual opportunities arise from interactions between the two concepts? Community Development, 50(2), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2019.1572634

- Chu, E. K. (2018). Urban climate adaptation and the reshaping of state–society relations: The politics of community knowledge and mobilisation in Indore, India. Urban Studies, 55(8), 1766–1782. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016686509

- Chung, J. (2017). Politicised communities: Community-based adaptation to climate change in the Ethiopian highlands. University College London.

- Clapham, C. (1990). Transformation and continuity in revolutionary Ethiopia. Cambridge University Press.

- Cleaver, F. (2001). Institutions, agency and the limitations of participatory approaches to development. In B. Cooke & U. Kothari (Eds.), Participation: The new tyranny? (pp. 36–55). Zed Books.

- Cloke, P., Goodwin, M., & Milbourne, P. (1997). Rural Wales: Community and marginalisation. University of Wales Press.

- DeFilippis, J. (2001). The myth of social capital in community development. Housing Policy Debate, 12(4), 781–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2001.9521429

- Dessalegn Rahmato. (2009). The peasant and the state: Studies in agrarian change in Ethiopia 1950s-2000s. Addis Ababa University Press.

- Dodman, D., & Mitlin, D. (2013). Challenges for community-based adaptation: Discovering the potential for transformation. Journal of International Development, 25(5), 640–659. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1772

- Dodman, D., Mitlin, D., & Co, J. R. (2010). Victims to victors, disasters to opportunities: Community-driven responses to climate change in the Philippines. International Development Planning Review, 32(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2009.10

- Ensor, J. (2011). Uncertain futures: Adapting development to a changing climate. Practical Action.

- Ensor, J., & Berger, R. (2009). Community-based adaptation and culture in theory and practice. In W. N. Adger, I. Lorenzoni, K. L. O’Brien, W. N. Adger, I. Lorenzoni, & K. L. O’Brien (Eds.), Adapting to climate change (pp. 227–239). Cambridge University Press.

- Ensor, J., Park, S. E., Attwood, S. J., Kaminski, A. M., & Johnson, J. E. (2018). Can community-based adaptation increase resilience? Climate and Development, 10(2), 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2016.1223595

- Fenton, A., Gallagher, D., Wright, H., Huq, S., & Nyandiga, C. (2014). Up-scaling finance for community-based adaptation. Climate and Development, 6(4), 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.953902

- Forsyth, T. (2013). Community-based adaptation: A review of past and future challenges. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 4(5), 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.231

- Gogoi, E., Dupar, M., Jones, L., Martinez, C., & McNamara, L. (2014). How to scale out community-based adaptation to climate change. DfID, UK. https://www.gov.uk/research-for-development-outputs/how-to-scale-out-community-based-adaptation-to-climate-change

- Gusfield, J. R. (1978). Community: A critical response. Harper & Row.

- Heller, K. (1989). The return to community. American Journal of Community Psychology, 17(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00931199

- Howard, S. (2010). Ethiopia – Culture smart! The essential guide to customs & culture. Kuperard.

- Huq, S., Ochieng, C., Orindi, V. A., & Owiyo, T. (eds.). (2017). Enhancing adaptation to climate change in developing countries through community-based adaptation: Think globally and act locally. ACTS Press.

- Jewkes, R., & Murcott, A. (1996). Meanings of community. Social Science & Medicine, 43(4), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00439-4

- Kothari, U. (2001). Power, knowledge and social control in participatory development. In B. Cooke & U. Kothari (Eds.), Participation: The new tyranny? (pp. 139–152). Zed Books.

- Li, T. (2007). The will to improve: Governmentality, development, and the practice of politics. Duke University Press.

- Mackenzie, A. F. D., & Dalby, S. (2003). Moving mountains: Community and resistance in the Isle of Harris, Scotland, and Cape Breton, Canada. Antipode, 35(2), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00325

- Manderson, L., Kelaher, M., Williams, G., & Shannon, C. (1998). The politics of community: Negotiation and consultation in research on women’s health. Human Organization, 57(2), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.57.2.3055x1568856377t

- Mansuri, G., & Rao, V. (2004). Community-based and -driven development: A critical review. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 3209. World Bank.

- Matarrita-Cascante, D., & Brennan, M. A. (2012). Conceptualizing community development in the twenty-first century. Community Development, 43(3), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2011.593267

- McNamara, K. E., & Buggy, L. (2017). Community-based climate change adaptation: A review of academic literature. Local Environment, 22(4), 443–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2016.1216954

- McNamara, K. E., Clissold, R., Westoby, R., Piggott-McKellar, A. E., Kumar, R., Clarke, T., Namoumou, F., Areki, F., Joseph, E., Warrick, O., & Nunn, P. D. (2020). An assessment of community-based adaptation initiatives in the Pacific Islands. Nature Climate Change, 10(7), 628–639. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0813-1

- Mehret Ayenew. (2002). Decentralization in Ethiopia. In B. Zewde & S. Pausewang (Eds.), Ethiopia: The challenge of democracy from below (pp. 130–148). Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Nancy, J.-L. (1991). The in-operative community (P. Connor & L. Garbus, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press.

- Mosse, D. (1999). Colonial and contemporary ideologies of ‘community management’: The case of tank irrigation development in South India. Modern Asian Studies, 33(2), 303–338. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X99003285

- Nightingale, A. (2002). Participating or just sitting in? The dynamics of gender and caste in community forestry. Journal of Forest and Livelihood, 2(1), 17–24.

- Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

- Page, B. (2002). Urban agriculture in Cameroon: An anti-politics machine in the making? Geoforum: Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 33(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(01)00022-7

- Panelli, R. (2001). Narratives of community and change in a contemporary rural setting: The case of Duaringa, Queensland. Australian Geographical Studies, 39(2), 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8470.00137

- Panelli, R., Gallagher, L., & Kearns, R. (2006). Access to rural health services: Research as community action and policy critique. Social Science & Medicine, 62(5), 1103–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.018

- Panelli, R., & Welch, R. (2005). Why community? Reading difference and singularity with community. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 37(9), 1589–1611. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37257

- Pausewang, S. (1990). Ethiopia: Options for rural development. Zed Books.

- Perreault, T. (2003). Changing places: Transnational networks, ethnic politics, and community development in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Political Geography, 22(1), 61–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(02)00058-6

- Planel, S., & Bridonneau, M. (2015). Glocal Ethiopia: Scales and power shifts. EchoGéo, 31. https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.14219

- Poluha, E., & Rosendahl, M. (2012). Contesting good governance: Crosscultural perspectives on representation. Routledge.

- Reid, H. (2016). Ecosystem- and community-based adaptation: Learning from community-based natural resource management. Climate and Development, 8(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2015.1034233

- Secomb, L. (2000). Fractured community. Hypatia, 15(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2000.tb00319.x

- Schmitt, C. (1932). The concept of the political. University of Chicago Press.

- Sharma, A. (2014). Why community ‘based’ adaptation to climate change is not enough. IIED. https://www.iied.org/why-community-based-adaptation-climate-change-not-enough

- Sharma, J. R., & Nightingale, A. (2014). Conflict resilience among community forestry user groups: Experiences in Nepal. Disasters, 38(3), 517–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12056

- Sheikh, A. T. (2012). NEWS: Looking ahead to the 6th Community-Based Adaptation (CBA) Conference. Presented at the 6th Community-Based Adaptation (CBA) Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Singh, C., Iyer, S., New, M. G., Few, R., Kuchimanchi, B., Segnon, A. C., & Morchain, D. (2021). Interrogating ‘effectiveness’ in climate change adaptation: 11 guiding principles for adaptation research and practice. Climate and Development, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2021.1964937

- Small Grants Programme (SGP). (2019). Mission and history. Small Grants Programme (SGP). https://sgp.undp.org/about-us-157/mission-and-history.html

- Staeheli, L. (2008). More on the ‘problems’ of community. Political Geography, 27(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.09.004

- Staheli, L., & Thompson, A. (1997). Citizenship, community and struggles for public space. The Professional Geographer, 49(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00053

- Strasser, R., Worley, P., Cristobal, F., Marsh, D. C., Berry, S., Strasser, S., & Ellaway, R. (2015). Putting communities in the driver’s seat. Academic Medicine, 90(11), 1466–1470. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000765

- Swyngedouw, E., & Heynen, N. C. (2003). Urban political ecology, justice and the politics of scale. Antipode, 35(5), 898–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2003.00364.x

- Taylor, M. E. (2015). The political ecology of climate change adaptation: Livelihoods, agrarian change and the conflicts of development. Routledge.

- Teferi Abate. (2004). ‘Decentralised there, centralised here’: Local governance and paradoxes of household autonomy and control in north-East Ethiopia, 1991–2001. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 74(4), 611–632. https://doi.org/10.3366/afr.2004.74.4.611

- Tronvoll, K., & Hagmann, T. (eds.). (2012). Contested power in Ethiopia: Traditional authorities and multi-party elections. African Social Studies Series.

- Vaughan, S., & Tronvoll, K. (2003). The culture of power in contemporary Ethiopian political life. Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

- Voydanoff, P. (2001). Conceptualizing community in the context of work and family. Community, Work & Family, 4(2), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/713658928

- Watson, E. (2006). Making a living in the postsocialist periphery: Struggles between farmers and traders in Konso, Ethiopia. Africa, 76(1), 70–87. https://doi.org/10.3366/afr.2006.0006

- Watts, M., & Peet, R. (2004). Liberation ecologies. Routledge.

- Welch, R., & Panelli, R. (2007). Questioning community as a collective antidote to fear: Jean-Luc Nancy’s ‘singularity’ and ‘being singular plural’. Area, 39(3), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2007.00755.x

- Yates, J. S. (2014). Power and politics in the governance of community-based adaptation. In J. Ensor, R. Berger, & S. Huq (Eds.), Community-based adaptation to climate change: Emerging lessons (pp. 15–34). Practical Action Publishing. https://doi.org/10.3362/9781780447902

- Yilmaz, S., & Venugopal, V. (2008). Local government discretion and accountability in Ethiopia, Working paper, 8–38. International studies program, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University.

- Young, J. (1997). Peasant revolution in Ethiopia the Tigray people’s liberation front 1975-1991. Cambridge University Press.