ABSTRACT

Migration can strengthen adaptation to climate change. The potential of migration-as-adaptation builds on a world of intensifying global mobility and global connectedness and the increasing possibility of geographically spreading risks. But what if mobility is impeded and connectivity disrupted? And what happens if geographically distant places face risks simultaneously due to the global and systemic character or multiplicity of crises? This paper points to fundamental gaps in research on migration-as-adaptation, which largely neglects the questions of adaptation limits. It argues that an understanding of the limits of migration-as-adaptation needs to address (1) migration as an inherent feature of social systems under stress, (2) the unequal and contested nature of adaptation goals, and (3) immobility, disconnectedness and simultaneous exposure as the core mechanisms that limit the adaptive potential of migration. The paper proposes a novel translocal-mobilities perspective to address the multi-scalar, multi-local, relational and intersectional dynamics of the limits of migration-as-adaptation. It formulates core questions for research on the limits of migration as adaptation. A comprehensive understanding will help the scientific community to build more realistic scenarios on climate change and migration and provide entry points for policies to avoid reaching adaptation limits and to mitigate negative consequences.

1. Introduction

Different forms of human migration – from voluntary adaptive migration to forced distress migration and displacement – are well-acknowledged as potential outcomes of households and communities dealing with climatic risks and hazards (Piguet, Citation2011; Boas et al., Citation2019; Borderon et al., Citation2019; McLeman et al., Citation2021; Horton et al., Citation2021). The assessment and interpretation of migration amid climate change can vary greatly (Sakdapolrak & Sterly, Citation2020). On the one hand, migration can be a sign of adaptation failure when risk-mitigation strategies of households fail or livelihoods collapse. In such cases, the last resort that households can draw on is often distress migration and involuntary displacement resulting in reduced levels of livelihood security and well-being (Hauer et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, migration can itself be a form of pro-active and successful adaptation: households can draw on migration to diversify risks and maintain well-being during a crisis, for example, by sending members to the city to buffer agricultural income loss through remittances in the context of a drought (Warner & Afifi, Citation2014). Early research and debates on the relationship have emphasized the former (El Hinnawi, Citation1985; Meyer, Citation2002), but the recognition that migration can function as a means of adaptation to climate change is growing (Black et al., Citation2011; Gemenne & Blocher, Citation2017; McLeman, Citation2016; Vinke et al., Citation2020) – not least since the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Party (COP 16) in Cancun, Mexico (Warner, Citation2012), and the publication of the influential UK Government’s 2011 Foresight report on Migration and Global Environmental Change (Foresight, Citation2011).

The underlying assumption of migration-as-adaptation is the notion of a world of intensifying global mobilities and global connectedness and of the possibility of geographically spreading risk. Migration is often considered to generate a triple-win situation with benefits at places of origin and destination as well as for migrants themselves (Castles & Ozkul, Citation2020). But what if mobility is impeded and connectivity disrupted through violent conflicts, financial crises or highly securitized border regimes? And what happens if geographically distant places are simultaneously facing risks due to the global and systemic character or multiplicity of crises such as climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic? While research on migration as an (adaptive) outcome of climatic risks and hazards is rapidly expanding, there is limited research that (a) starts with viewing migration as an inherent feature of social systems under stress and that (b) asks under what circumstances the adaptive potential of migration approaches its limits, and with what implications. This is particularly surprising as it is well-documented that migration – regardless of adaptation needs – is an integral part of rural livelihoods of people around the world (Kelly, Citation2013; Rigg & Vandergeest, Citation2012) and that the questions of the general limits of adaptation have been taken up by the IPCC assessment for almost a decade (IPCC, Citation2014).

The paper provides a conceptual framework that enables a comprehensive and systematic analysis of the limits of migration as adaptation and the consequences, building on a translocal-mobilities approach. It carves out the blind spots in current research on migration as adaptation and connects it to insights from research on the limits of adaptation. Such an understanding of the limits of migration-as-adaptation needs to address (1) migration as an inherent feature of most social systems, (2) the unequal and contested nature of adaptation goals, and (3) immobility, disconnectedness and simultaneous exposure as the core mechanisms that limit the adaptive potential of migration. It highlights core questions that needs to be addressed when operationalizing this framework.

2. Migration-as-adaptation

In the debate on the relationship between climate change and migration (Barnett & Adger, Citation2018; Brzoska & Fröhlich, Citation2016; Cattaneo et al., Citation2019; Ferris, Citation2020; Piguet, Citation2011), the idea of migration-as-adaptation has developed as a concept to counter the alarmist and apocalyptic narrative of environmental refugees (Black, et al., Citation2011; Foresight, Citation2011). Rather than seeing migrants as passive victims of climate change, the notion of migration-as-adaptation emphasizes human agency and highlights the potential positive contribution to adaptive capacity (e.g. through financial and social remittances) and its transformational potential (Barnett & Webber, Citation2010; Black et al., Citation2011; Kniveton, et al., Citation2012; Tacoli, Citation2009). There is ample evidence for the significance of migration-as-adaptation: 40% of the studies included in the review on smallholder climate-change adaptation in Asia, Africa and South America by Burnham and Ma (Citation2016) mentioned migration as a risk-mitigation strategy. In a meta-analysis on adaptation in Sub-Saharan African dryland by Wiederkehr et al. (Citation2018), who analysed 63 studies covering more than 6700 rural households, it is reported that one-quarter of rural households rely on migration as an adaptation strategy. An estimate by IFAD (Citation2017) states that every ninth person globally is dependent on remittances from international migrants for securing livelihoods. Considering that the majority of migrants move within national borders and that domestic migrants remit as well (Porst & Sakdapolrak, Citation2020), it can be assumed that the actual importance of remittances is even higher. While for some households remittances merely serve as a means for survival during “normal” times, during disasters and other crises, remittances are considered a stable source of income and as reducing the vulnerability of recipient households (Le De & Friesen, Citation2013; Mohapatra & Ozden, Citation2009; Savage & Harvey, Citation2007), as could be observed for households dealing with drought in Somalia (Plaza, Citation2019) or recovering from Hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua (Andersen & Christensen, Citation2009).

There is a growing body of literature addressing migration-as-adaptation (overview see Gemenne & Blocher, Citation2017; McLeman, Citation2016; Vinke et al., Citation2020). On a theoretical level, studies draw on concepts of vulnerability (McLeman & Smit, Citation2006) and/or resilience (Deshingkar, Citation2012) and analyse migration-as-adaptation against the backdrop of risk exposure and coping or adaptive capacity (Black, et al., Citation2013). Tacoli (Citation2011) highlights that migration in the context of environmental change is best understood as embedded in the wider context of livelihood strategies of individuals and households and is carried out based on their capabilities and assets. The scope of empirical studies on migration-as-adaptation is broad; they focus on different types of migration (Banerjee, Citation2016; Demoulin et al., Citation2013; Leyk et al., Citation2017; Maharjan et al., Citation2020; Nawrotzki et al., Citation2015a, Citation2016), remittances and diaspora (Musah-Surugu et al., Citation2018; Scheffran et al., Citation2012), and perception (van Praag, Citation2021), among other criteria.

In spite of the growing body of relevant literature, important aspects remain understudied:

First, the focus of studies on migration-as-adaptation as part of the broader climate-migration literature largely remains on (adaptive) migration that happens as an outcome of climate risks and hazards (McLeman et al., Citation2021). Most research on migration-as-adaptation neglects the “nested and tele-connected” (Adger et al., Citation2009, p. 150; Eakin et al., Citation2009) nature of vulnerabilities against climate-related risks and hazards. People’s livelihoods, and in turn their vulnerabilities, are rarely geographically bounded but often, and increasingly, spatially connected through migration, among other translocal relations (Etzold & Sakdapolrak, Citation2016; le Polain de Waroux, Citation2019; Runfola et al., Citation2016). Therefore, migration needs to be considered also as an integral part of livelihood systems and not merely as an outcome of risk exposure (Burnham & Ma, Citation2016; Tacoli, Citation2009). While there are a few exceptions, for example considering the role of labour migration for adaptation (e.g. Banerjee, Citation2016; Maharjan et al., Citation2020) and the interrelation between labour migration in the context of socio-ecological change (Wrathall et al., Citation2013, Citation2014), our understanding remains limited and further research needs to be undertaken (Burnham & Ma, Citation2016).

Second, since the publication of the Foresight Report (Citation2011), scholars have drawn attention to migrants at risk in (urban) places of destination (Adger et al., Citation2021; Findlay, Citation2011; Gänsbauer et al., Citation2017; Nawrotzki et al., Citation2015b; Siddiqui et al., Citation2020; Spilker et al., Citation2020) and have acknowledged the multilocal nature of migration-as-adaptation in the context of climate change (see Gemenne & Blocher, Citation2017). However, an integrated conceptualization of both places of origin and destination as parts of a spatially connected livelihood system under stress are rare (Sakdapolrak et al., Citation2016; Peth & Sakdapolrak, Citation2020; Porst & Sakdapolrak, Citation2020).

Thirdly, the Foresight Report (Citation2011) has also highlighted the need, and triggered efforts to address immobility in the context of environmental and climate change. The issue has evolved as a field of research in its own (Black & Collyer, Citation2014; Adams et al Citation2016; Farbotko & McMichael, Citation2019; Zickgraf, Citation2018, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Mallick & Schanze, Citation2020; Mallick et al., Citation2021; Ayeb-Karlsson et al., Citation2020; Pemberton et al., Citation2021) and not only as a residual category of migration. While early research in the field has emphasized involuntary immobility, which has been framed “trapped population” (Ayeb-Karlsson et al., Citation2020), empirical evidence indicates that immobility in the context of environmental change exists along a continuum between voluntary and involuntary (Adams, Citation2016; Mallick et al., Citation2021). Voluntary immobility, as Farbotko and McMichael (Citation2019) highlight for the case of the Pacific, can be considered as active adaptation strategy representing agency and resistance to dispossession in context of risk of relocation. The aspiration-(cap)ability framework (Carling, Citation2002; de Haas, Citation2021; Schewel, Citation2020) proves to be a useful analytical tool to distinguish and understand different types of immobility and the different structural and intrinsic factors shaping immobility. Blondin (Citation2020) points to the importance to consider “motility” (Kaufmann et al., Citation2004) – the actual and potential capacity to be mobile which is conceptualized depending on mobility options and access, mobility competences and skills as well as plans and aspirations – for the understanding of (im)mobility. Research on immobility has also placed a strong focus on individuals, but immobility in translocal household constellations has been neglected. The importance of considering intra-household dynamics, the relationship between (in)voluntary mobility of some households members and the (in)voluntary immobility of others has been highlighted by Reeves (Citation2011) and would be important to consider for immobility in the context of environmental change and climate change. Furthermore, research has to a large extent focused on immobility as an outcome of environmental risks. The implications of different forms of immobility for well-being and livelihood security in the context of climatic risks and hazards have not been addressed, and hence remain an important research gap to explore further.

Fourthly, the connectedness of migrants and their households at origin plays a central role for the notion of migration-as-adaptation (Nawrotzki et al., Citation2015c). It is well acknowledged that migration networks can facilitate further migration (Bardsley & Hugo, Citation2010), and there is evidence that this is the case in the context of environmental risks (Hunter et al., Citation2013). But the connectedness established through migration does also facilitate the flow of financial (Babagaliyeva et al., Citation2017; Musah-Surugu et al., Citation2018) and social remittances (Rockenbauch et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b) and thus can reduce sensitivity to climate risks and decreases the likelihood of further migration in this context (Nawrotzki et al., Citation2015c). This evidence points to the highly complex and context specific impacts of connectedness. Research has furthermore pointed out the deeply intertwined character of financial and social remittances (Peter, Citation2010, Peth & Sakdapolrak, Citation2020) and the reciprocal material and immaterial (social, emotional, symbolic) exchange between migrants and their households (Peth Citation2020). Studies on migration-as-adaptation mostly take the flow and absence of remittances as given (e.g. Banerjee, Citation2016) without addressing the mechanisms and determinants of these flows (Carling, Citation2008). There is limited understanding of the role of non-material dimensions of exchange (e.g. social and emotional support) for migration-as-adaptation. To our best knowledge, material and non-material dimensions of disconnectedness in the context of climatic risks and hazards have not yet been addressed as a specific research focus, rather than merely as the absence of remittances. Therefore the absence, discontinuation and disruption of connectedness (Belloni, Citation2020; Harper & Zubida, Citation2017) and their implications for migration-as-adaptation remains an important knowledge gap to be filled.

3. Limits of adaptation

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines adaptation as the “process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects, in order to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities” (IPCC, Citation2018b, p. 542). Expected rising levels of climate-related risks not only increase the need for adaptation to minimize their impact and avoid loss and damages (Magnan et al., Citation2020; Mechler et al., Citation2020), but also pose the question of limits of adaptation which human and natural systems might encounter (Adger et al., Citation2009; Barnett et al., Citation2013; Dow et al Citation2013a, Citation2013b; IPCC, Citation2014; Leal Filho & Nalau, Citation2018; Mechler et al., Citation2020). Limits of adaptation are points at which actors cannot secure their valued objectives (e.g. health, well-being, security, or a livelihood) against intolerable risks through adaptive actions (IPCC, Citation2018a; Leal Filho & Nalau, Citation2018). Intolerable risks are linked to tangible and intangible losses and damages, which “exceed a socially negotiated norm (e.g. the availability of clean drinking water) or a value (e.g. continuity of a way of life)” (Dow et al Citation2013a, p. 385) and which occur despite adaptive action. Two types of limits have been distinguished in the literature. “Hard” adaptation limits are points at which no adaptive action is possible to avoid intolerable risk. Hard limits are mostly bio-physical and relate to the natural system (e.g. loss of coral reefs due to temperature increase). “Soft” adaptation limits are reached due to options that are currently not available to avoid intolerable risks through adaptive action (IPCC, Citation2018a). Soft limits occur in the human system and are subject to change over time. They are linked to questions of agency and scale, as the capacity to adapt in order to prevent intolerable risks might be lacking on one scale (e.g. household at the local scale) but might be existenting on another scale (e.g. government on a national scale) (Barnett et al., Citation2015; McNamara et al., Citation2017). In practice, the differentiation between soft limits and adaptation barriers is often ambiguous (Barnett et al., Citation2015; McNamara et al., Citation2017). The challenge in analysing the limits of adaptation is that they can be defined in multiple ways (Felgenhauer, Citation2015). In contrast to the supposedly “immutable thresholds” in biological, technical and economic limits, Adger et al. (Citation2009) emphasize the importance of social limits of adaptation, which are endogenous to society and linked to ethics, knowledge, attitudes and culture. Place attachment (Adams, Citation2016) and loss of place and culture (Adger et al., Citation2009) for example are crucial for understanding the subjective limits for adaptation.

Two aspects in the research are particularly important to consider in the context of migration-as-adaptation:

Firstly, the valued objective needs to be questioned: as Adger et al. (Citation2009) point out, limits of adaptation depend on the goals of adaptation, and these are dependent on the diverse and also possibly contradictory values of the actors involved. Assessing the limits of adaptation therefore necessitates the identification of valued objectives – adaptation goals that are at stake. Such identification must consider at what scale and spatial domain and for whom they are relevant, how and by whom they are prioritized, how the risks to these values are perceived, and how trade-offs are made and negotiated, and must also discern whether patterns and regularities can be found. Based on multiple West-African case studies Carr (Citation2020) shows that people seek to achieve well-being while preserving existing social systems with their meanings, order and privileges, and therefore the interlinkages between the material and social goals are crucial to understand adaptation. He further hypothesizes that “above very, very low material thresholds (i.e. starvation)” (Carr, Citation2019, p. 73), social goals are prioritized over material goals. In a study on limits of adaptation of farmers in Costa Rica, Warner et al. (Citation2015) present contradicting evidence where farmers prioritize livelihood security over preservation of identity. There is limited understanding of how valued objectives are interdependent and negotiated and what the implications are for adaptation decisions.

Secondly, further explorations are needed of the consequences of reaching the limits. As Dow et al (Citation2013a, p. 386) point out, the limits of adaptation are “not the end of the adaptation process”. Once limits are reached, actors must either live with and endure loss and damages, adjust attitudes towards valued objectives, or engage in transformational change to avoid intolerable risks (Feola et al., Citation2015; Osbahr et al., Citation2008). With regard to the limits of adaptation, the rationale and mechanisms of following one of the three pathways identified by Dow et al. (Citation2013a) and their implications remain under-researched.

4. A new research approach to the limits of migration-as-adaptation

Starting from the three basic rationales of migration as adaptation, that are (1) spatial risk diversification, (2) mobility as a strategy for coping and adaptation, and (3) connectedness through financial and social remittances, we argue that migration-as-adaptation is pushed to its limits by the interplay of three corresponding core mechanisms: (1) simultaneous and/or over-exposure, (2) immobility, and (3) disconnectedness. On the one hand, increasing climate-related risks and hazards in conjunction with other crises (e.g. economic crises, conflicts) can exceed the adaptive capacity of migration-dependent, translocally situated households to secure their livelihoods and other valued objectives. Limits are reached particularly in cases of extreme exposure to stress (over-exposure) or in cases where different, geographically distant parts of migrants’ households face stressors at the same time (simultaneous exposure). On the other hand, a household’s capacity to utilize the adaptive potential of migration can be impeded through exogenous factors as well as internal dynamics: for example, tightening of immigration regimes can reduce motility and undermine a household’s ability to send household members to seek livelihoods elsewhere (immobility); changes in the sense of belonging and moral obligations of migrants can impede a household’s ability to draw on connectedness in the form of financial support to deal with risks (disconnectedness). It is the interplay between the growing level of climate-related risks and hazards in conjunction with other crises and immobility (due to the lack of capability and/or the aspiration to migrate) and disconnectedness (due to the lack of capability and/or aspiration to keep relations) that has the potential to destabilize existing translocal livelihoods systems, in ways that can finally undermine their ability to secure livelihoods and other valued objectives. Thus, the limits of migration-as-adaptation are defined as the inability of migrants and their households to secure their livelihoods, well-being, and other valued objectives from intolerable risks through migration-related adaptive practices.

In order to further conceptualize these mechanisms and thus to decipher the limits of migration-as-adaptation, we propose a translocal-mobilities perspective. It synthesizes the concepts of translocality (Brickell & Datta, Citation2011; Etzold, Citation2017; Greiner & Sakdapolrak, Citation2013) and the politics of mobility (Cresswell, Citation2010; Sheller & Urry, Citation2006). Thereby, the translocal-mobilities perspective builds on previous insights from the application and further development of both conceptual strands in the field of environment and climate change, namely through the concepts of translocal social resilience (Peth, Citation2020; Porst, Citation2020; Rockenbauch, Citation2022; Sakdapolrak et al., Citation2016) and climate mobilities (Boas et al., Citation2022, Parsons, Citation2019). A translocal-mobilities perspective brings together two important perspectives: on one hand the understanding of the multiplicity of (im-)mobilities (e.g. migration of people, transfer of money and ideas) as product of unequal social relations embeddedness in “climate mobilities regimes” (Boas et al., Citation2022, p. 3371), which frames, manages and regulates mobilities in the context of environment and climate change. Therefore the question of mobility justice (Sheller, Citation2018) is a core concern for the understanding of the limits of migration-as-adaptation; on the other hand, this emphasises the tension between the embeddedness of people in certain places and the simultaneous connectedness and feed-back relations between geographically distant places (Peth, Citation2020; Peth et al., Citation2018). The limits of migration-as-adaptation are considered as constituted through social practices (Bourdieu, Citation1998). An emphasis is thereby placed on the relation between structure and agency in shaping immobility and disconnectedness of social actors, who are – due to unequally distributed tangible and intangible resources – unequally positioned in multiple (translocal) social fields and embedded in multiple and overlapping axes of social differentiation.

From a translocal-mobilities perspective, the livelihoods of migrants and their households at both places of destination and origin are understood as being parts of a single functional and social unit. In doing so, the multi-scalar (individual, household), multi-local (places of origin, places of destination) and relational (feedback processes) character of migration-as-adaptation is explicitly addressed. A translocal-mobilities perspective explicitly directs attention to the tele-coupling of livelihoods systems: stress and perturbation in one place influence livelihoods in other places. Furthermore, it is argued that translocal constellations are influencing and thus need to be considered for understanding capabilities and aspirations relating to immobility and disconnectedness (Carling, Citation2002; de Haas, Citation2021; Schewel, Citation2020). Voluntary immobility in the places of origin can be facilitated by translocal networks, which reduce the sensitivity to climatic risks (Nawrotzki et al., Citation2015c). Migrants in the places of destination can be forced to be immobile as translocal households are dependent on their support (Porst & Sakdapolrak, Citation2018), or kept in exploitative working conditions (Parsons & Brickell, Citation2020). A core of the assessment of the limits of adaptation is the identification of the material and social adaptation goals and the valued objectives that are considered to be at stake. The focus on translocal household constellations explicitly considers different positionalities, interests, needs, levels of acceptance and tolerance of risks of different members of such constellations. Unequal power relations, gender and intersectionality influence the negotiation of which risks to livelihoods goals and valued objectives are acceptable or tolerable, and of who benefits and bears the cost of (im-)mobility and (dis-)connectedness and with what consequences.

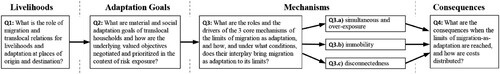

The analysis of the limits of migration-as-adaptation needs to address four core questions (): first, what is the differentiated role of migration and translocal relations for livelihoods and adaptation at places of origin and destination? (question 1). It is important to understand the patterns of migration (who moves where, when, and for what purpose) and how migration contributes to the way households deal with risks, while not neglecting the meaning and importance of migration beyond adaptation rationales. People are migrating not only to adapt, but for various other reasons (economic, social, cultural, political) and these have implications for the adaptive potential of migration (Porst & Sakdapolrak, Citation2018). Furthermore, migration is not the only strategy households use to deal with risks. Therefore, adaptation interrelates and competes with other rationales of migration, and migration interrelates and competes with other adaptation strategies.

Second, what are the material and social adaptation goals of translocal households and how are the underlying valued objectives negotiated and prioritised in context of risk exposure (question 2)? The valued objectives, the material and social goals of translocal households and their members need to be identified. Furthermore, the question of how they are negotiated and prioritised, how the risk to these values are perceived, and how trade-offs are produced and negotiated in the context of risk exposure needs to be addressed. Objective and subjective well-being (Stillmann et al., Citation2015; Western & Tomaszewski, Citation2016; White, Citation2010), different measures of livelihoods security as well as an understanding of how livelihoods create meaning and a sense of identity (Bebbington, Citation1999) and (re-)produce social order (Carr, Citation2019) must be considered.

Third, what are the roles and drivers of the three core mechanisms of the limits of migration-as-adaptation – (a) simultaneous and over-exposure, (b) immobility, and (c) disconnectedness – and how, and under what conditions, does the interplay between these mechanisms bring migration-as-adaptation to its limits (question 3)?

Mechanism 1 – Simultaneous and over-exposure: the limits of migration-as-adaptation are reached, first, when the degree of exposure to stress of one part of the translocal household and the resource needs to deal with its impact exceed the supporting capacity of the other part of the translocal household (Ayanlade et al., Citation2022 Black, et al., Citation2013); and/or second, when both parts of the households are exposed to stress simultaneously in multiple and systemic global crisis situations (e.g. due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Sydney C, Citationn.d)) and the spatial risk-diversification function of migration is undermined (Phillips et al., Citation2020).

Mechanism 2 – Immobility in the context of climatic risks: the limits of migration-as-adaptation are reached when spatial mobility as a coping and adaptation strategy is impeded or not opted for. Immobility can be driven by external political (e.g. border policy), economic (e.g. cost of mobility), social (e.g. migration networks) or physical (e.g. transport infrastructure) constraining and enabling factors as well as internal logics of practice such as place attachment (Adams, Citation2016) and gender norms (Lama et al., Citation2021). Depending on the degree of aspiration and capability (de Haas, Citation2021), motility (Blondin, Citation2020), immobility can take the form of voluntary, involuntary or acquiescent immobility (Carling, Citation2002; Schewel, Citation2020).

Mechanism 3 – Disconnectedness in the context of climatic risks: the limits of migration-as-adaptation are reached when social and emotional connectedness and the transfers of social and financial remittances between migrants and their households are absent, disrupted or discontinued. Disconnectedness can also be driven by external political (e.g. travel restrictions, remittance impediments), economic (e.g. economic downturn), social (e.g. migration networks) or physical (e.g. ICT infrastructure) constraining and enabling factors as well as internal logics of practice sense of belonging, family norms, filial obligations and expectations (Belloni, Citation2020; Harper & Zubida, Citation2017).

The fourth and last aspect of the analysis focuses on the consequences of reaching adaptation limits (question 4). What are the rationales of translocal households to follow a specific path as outlined by Dow et al. (Citation2013a) – endure loss and damages, adjust attitudes, or effect transformational change? How are these paths negotiated and with what consequences for which member(s) in the translocal household?

By addressing these four core questions through a translocal mobilities perspective new empirical case studies could account for the socio-spatialities of the underlying mechanisms that limit migration-as-adaptation and therefore fill a gap in migration, climate change and other studies. The concept is open for different research designs, however a mixed methods translocal / multilocal (Massey & Zenteno, Citation2000, Marcus Citation1995; Beauchemin, Citation2014) and comparative (Czaika & Godin, Citation2022) approach as well as a diachronic perspective are important. The core questions can serve as a basis for conceptual models and the elaboration of variables for empirical calibration. Given the specific national, regional or even local characteristics of migration systems, structural reasons for vulnerability and adaptation options, this likely needs to involve a high degree of contextualization. The recent insights of the large-scale COVID-19 crisis and its impacts on migrants and on vulnerable population groups have reinforced the necessary consideration of migration as an inherent feature of systems under stress (Guadagno, Citation2020; Ratha et al., Citation2020; Surhardiman et al., Citation2021). There is an urgent need for research to address the circumstances under which the adaptive potential of migration reaches its limits and what implications this can have.

5. Conclusion

In this article we highlighted blind spots in research on migration-as-adaptation and the need to closely engage with the question of the limits of adaptation. The proposed translocal-mobilities perspective allows to assess the mechanisms and consequences of reaching the limits of migration as adaptation, both in terms of their nature (e.g. adjustment of valued objectives, increasing poverty, more migration) and their magnitude (e.g. how many people would potentially choose more migration as a strategy). Adaptation research, hitherto often conceptualizing social entities such as communities and households as spatially bounded and largely unconnected entities, will be augmented by a strong theory of (social and economic) tele-coupling, enabling them to include the vast existing migration (systems) in concepts and studies of autonomous adaptation. Stakeholders involved in adaptation policy making will have a robust conceptual and methodological instrumentarium to include the limits, but also the potentials of migration for adaptation in their work and hence to improve the harmonization of planned and autonomous adaptation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Patrick Sakdapolrak

Patrick Sakdapolrak is professor for population geography and demography at the Department of Geography and Regional Research, University of Vienna. His research field is at the interface of population dynamics, environmental change and development processes, with a focus on the topics of translocal dynamics of climate mobilities.

Marion Borderon

Marion Borderon is a senior scientist at the Department of Geography and Regional Research, University of Vienna. Her work focuses on contributing to the development of concepts and methods for the spatial assessment of vulnerability and risk in the context of environmental transformation.

Harald Sterly

Harald Sterly is a senior scientist at the Department of Geography and Regional Research, University of Vienna. His research focuses on spatial and social aspects of the intersection of climate and environmental change and different forms of mobility and migration with a specific focus on outcomes of migration and translocal connectivities.

References

- Adams, H. (2016). Why populations persist: Mobility, place attachment and climate change. Population and Environment, 37(4), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-015-0246-3

- Adams, H., Adger, W. N., Ahmad, S., Ahmed, A., Begum, D., Lázár, A. N., Matthews, Z., Mofizur Rahman, M., & Streatfield, P. K. (2016). Spatial and temporal dynamics of multidimensional well-being, livelihoods and ecosystem services in coastal Bangladesh. Scientific Data, 3(1), Article 160094. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.94

- Adger, W. N., de Campos, R. S., Siddiqui, T., Gavonel, M. F., Szaboova, L., Rocky, H. M., Bhuiyan, M. R. A., & Billah, T. (2021). Human security of urban migrant populations affected by length of residence and environmental hazards. Journal of Peace Research, 58(1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320973717

- Adger, W. N., Dessai, S., Goulden, M., Hulme, M., Lorenzoni, I., Naess, L. O., & Wreford, A. (2009). Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Climatic Change, 93(3-4), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-008-9520-z

- Andersen, L. E., & Christensen, B. J. (2009). The static and dynamic benefits of migration and remittances in Nicaragua. Development Research Working Paper Series 05/2009 (Institute for Advanced Development Studies).

- Ayanlade, A., Oluwaranti, A., Ayanlade, O. S., Borderon, M., Sterly, H., Sakdapolrak, P., Jegede, M. O., Weldemariam, L. F., & Ayinde, A. F. (2022). Extreme climate events in sub-Saharan Africa: A call for improving agricultural technology transfer to enhance adaptive capacity. Climate Services, 27, Article 100311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2022.100311

- Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Kniveton, D., & Cannon, T. (2020). Trapped in the prison of the mind: Notions of climate-induced (im)mobility decision-making and wellbeing from an urban informal settlement in Bangladesh. Palgrave Communications, 6(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0443-2

- Babagaliyeva, Z., Abdulkhamid, K., Mahmadullozoda, N., & Mustaeva, N. (2017). Migration, remittances and climate resilience in Tajikistan. Working Paper Part I (Regional Environmental Centre for Central Asia).

- Banerjee, S. (2016). Understanding the Effects of Labour Migration on Vulnerability to Extreme Events in Hindu Kush Himalayas. Case Studies from Upper Assam and Baoshan County [PhD thesis]. University of Sussex.

- Bardsley, D., & Hugo, G. J. (2010). Migration and climate change: Examining thresholds of change to guide effective adaptation decision-making. Population and Environment, 32(2-3), 238–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-010-0126-9

- Barnett, J., & Adger, W. N. (2018). Mobile worlds: Choice at the intersection of demographic and environmental change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 43(1), 245–265. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060952

- Barnett, J., Evans, L. S., Gross, C., Kiem, A. S., Kingsford, R. T., Palutikof, J. P., Pickering, C. M., & Smithers, S. G. (2015). From barriers to limits to climate change adaptation: Path dependency and the speed of change. Ecology and Society, 20(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07698-200305

- Barnett, J., Mortreux, C., & Adger, W. N. (2013). Barriers and limits to adaptation: Cautionary notes. In S. Boulter, J. Palutikof, D. J. Karoly, & D. Guitart (Eds.), Natural disasters and adaptation to climate change (pp. 223–235). Cambridge University Press.

- Barnett, J., & Webber, M. (2010). Accommodating Migration to Promote Adaptation to Climate Change. Background Paper to the 2010 World Development Report. Policy Research Working Paper WPS 5270 (World Bank). Retrieved 14 July 2021. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/3757

- Beauchemin, C. (2014). A manifesto for quantitative multi-sited approaches to international migration. International Migration Review, 48(4), 921–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12157

- Bebbington, A. (1999). Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development, 27(12), 2021–2044. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00104-7

- Belloni, M. (2020). When the phone stops ringing: On the meanings and causes of disruptions in communication between Eritrean refugees and their families back home. Global Networks, 20(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12230

- Black, R., Arnell, N. W., Adger, W. N., Thomas, D., & Geddes, A. (2013). Migration, immobility and displacement outcomes following extreme events. Environmental Science & Policy, 27, S32–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.09.001

- Black, R., Bennett, S. R. G., Thomas, S. M., & Beddington, J. R. 2011. Migration as adaptation. Nature, 478(7370), 447–449. https://doi.org/10.1038/478477a

- Black, R., & Collyer, M. (2014). Populations ‘trapped’ at times of crisis. Forced Migration Review, 45 (February), 52–56. https://www.fmreview.org/crisis/black-collyer

- Blondin, S. (2020). Understanding involuntary immobility in the Bartang Valley of Tajikistan through the prism of motility. Mobilities, 15(4), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2020.1746146

- Boas, I., Farbotko, C., Adams, H., Sterly, H., Bush, S., van der Geest, K., Wiegel, H., Ashraf, H., Baldwin, A., Bettini, G., Blondin, S., de Bruijn, M., Durand-Delacre, D., Fröhlich, C., Gioli, G., Guaita, L., Hut, E., Jarawura, F. X., Lamers, M., … Hulme, M. (2019). Climate migration myths. Nature Climate Change, 9(12), 901–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0633-3

- Boas, I., Wiegel, H., Farbotko, C., Warner, J., & Sheller, M. (2022). Climate mobilities: Migration, im/mobilities and mobility regimes in a changing climate. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(14), 3365–3379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2066264

- Borderon, M., Sakdapolrak, P., Muttarak, R., Kebede, E., Pagogna, R., & Sporer, E. (2019). Migration influenced by environmental change in Africa: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Demographic Research, 41, 491–544. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2019.41.18

- Bourdieu, P. (1998). Praktische Vernunft. Zur Theorie des Handelns (Suhrkamp).

- Brickell, K., & Datta, A. (2011). Introduction: Translocal geographies. In K. Brickell & A. Datta (Eds.), Translocal geographies: Spaces, places, connections (pp. 1–20). Aldershot.

- Brzoska, M., & Fröhlich, C. (2016). Climate change, migration and violent conflict: Vulnerabilities, pathways and adaptation strategies. Migration and Development, 5(2), 190–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2015.1022973

- Burnham, M., & Ma, Z. (2016). Linking smallholder farmer climate change adaptation decisions to development. Climate and Development, 8(4), 289–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2015.1067180

- Carling, J. (2002). Migration in the age of involuntary immobility: Theoretical reflections and Cape Verdean experiences. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 28(1), 5–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830120103912

- Carling, J. (2008). The determinants of migrant remittances. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(3), 581–598. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grn022

- Carr, E. R. (2020). Resilient livelihoods in an era of global transformation. Global Environmental Change, 64, Article 102155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102155

- Carr E, R. (2019). Properties and projects: Reconciling resilience and transformation for adaptation and development. World Development, 122, 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.05.011

- Castles, S., & Ozkul, D. (2020). Circular migration: Triple win, or a new label for temporary migration. In G. Battistella (Ed.), Global and Asian perspectives on international migration (Global Migration Issues 4) (pp. 27–49). Springer.

- Cattaneo, C., Beine, M., Fröhlich C, J., Kniveton, D., Martinez-Zarzoso, I., Mastrorillo, M., Millock, K., Piguet, E., & Schraven, B. (2019). Human migration in the Era of climate change. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 13(2), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rez008

- Cresswell, T. (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1068/d11407

- Czaika, M., & Godin, M. (2022). Disentangling the migration-development nexus using QCA. Migration and Development, 11(3), 1065–1086. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2020.1866878

- de Haas, H. (2021). A theory of migration: The aspirations-capabilities framework. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(8), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4

- Demoulin F, Vanegas R and Henry S. 2013, August. Benefits of international migrations for socio-ecological resilience of rural households in the home country: Empirical evidences in two Ecuadorian provinces (Presented at the XXVII IUSSP International Population Conference, Busan – Korea. Retrieved 14 July, 2021, from https://epc2014.princeton.edu/papers/140196

- Deshingkar, P. (2012). Environmental risk, resilience and migration: Implications for natural resource management and agriculture. Environmental Research Letters, 7(1), Article 015603. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/7/1/015603

- Dow, K., Berkhout, F., & Preston, B. L. (2013a). Limits to adaptation to climate change: A risk approach. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5(3-4), 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.005

- Dow, K., Berkhout, F., Preston, B. L., Klein, R. J. T., Midgley, G., & Shaw, R. (2013b). Limits to adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 3(4), 305–307. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1847

- Eakin, H., Winkels, A., & Sendzimir, J. (2009). Nested vulnerability: Exploring cross-scale linkages and vulnerability teleconnections in Mexican and Vietnamese coffee systems. Environmental Science & Policy, 12(4), 398–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2008.09.003

- El Hinnawi, E. (1985). Environmental refugees. UNEP (Nairobi).

- Etzold, B. (2017). Mobility, space and livelihood trajectories. New perspectives on migration, translocality and place-making for livelihood studies. In L. de Haan (Ed.), Livelihoods and development – New perspectives (pp. 44–68). Brill Publications.

- Etzold, B., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2016). Socio-spatialities of vulnerability: Towards a polymorphic perspective in vulnerability research. Die Erde, 147(4), 234–251. https://doi.org/10.12854/erde-147-21

- Farbotko, C., & McMichael, C. (2019). Voluntary immobility and existential security in a changing climate in the Pacific. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 60(2), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12231

- Felgenhauer, T. (2015). Addressing the limits to adaptation across four damage-response systems. Environmental Science & Policy, 50, 214–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.03.003

- Feola, G., Lerner, A. M., Jain, M., Montefrio, M. J. F., & Nicholas, K. A. (2015). Researching farmer behaviour in climate change adaptation and sustainable agriculture: Lessons learned from five case studies. Journal of Rural Studies, 39, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.03.009

- Ferris, E. (2020). Research on climate change and migration where are we and where are we going? Migration Studies, 8(4), 612–625. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaa028

- Findlay, M. A. (2011). Migrant destinations in an era of environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 21, S50–S58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.004

- Foresight. 2011. Migration and Global Environmental Change. Final Project Report (London: The Government Office for Science. Retrieved 14 July 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287717/11-1116-migration-and-global-environmental-change.pdf

- Gänsbauer, A., Bilegsaikhan, S., Trupp, A., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2017). Migrants at risk. Responses of rural-urban migrants to the floods of 2011 in Thailand. TransRE working paper 6. Department of Geography, University of Bonn.

- Gemenne, F., & Blocher, J. (2017). How can migration serve adaptation to climate change? Challenges to fleshing out a policy ideal. The Geographical Journal, 183(4), 336–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12205

- Greiner, C., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2013). Rural–urban migration, agrarian change, and the environment in Kenya: A critical review of the literature. Population and Environment, 34(4), 524–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-012-0178-0

- Guadagno L. (2020). Migrants and the COVID-19 pandemic: An initial analysis Migration research series: no. 60 (International Organization for Migration). Retrieved 14 July 2021. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mrs-60.pdf

- Harper, R. A., & Zubida, H. (2017). Being seen: Visibility, families and dynamic remittance practices. Migration and Development, 7(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2017.1301303

- Hauer, M. E., Evans, J. M., & Mishra, D. R. (2016). Millions projected to be at risk from sea-level rise in the continental United States. Nature Climate Change, 6(7), 691–695. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2961

- Horton, R. M., de Sherbinin A., Wrathall D., & Oppenheimer M. (2021). Assessing human habitability and migration. Science, 372(6548), 1279–1283. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi8603

- Hunter, L. M., Murray, S., & Riosmena, F. (2013). Rainfall patterns and U.S. migration from rural Mexico. International Migration Review, 47(4), 874–909. http://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12051.

- IFAD. (2017). Sending Money Home: Contributing to the SDGs, one family at a time. IFAD. Retrieved 14 July 2021. https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/39135645/Sending+Money+Home+-+Contributing+to+the+SDGs%2C+one+family+at+a+time.pdf/c207b5f1-9fef-4877-9315-75463fccfaa7

- IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (International Panel on Climate Change). Retrieved 14 July 2021. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-PartA_FINAL.pdf

- IPCC. (2018a). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (International Panel on Climate Change). Retrieved 14 July 2021. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_Full_Report_High_Res.pdf

- IPCC. (2018b). Annex I: Glossary Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (International Panel on Climate Change). Retrieved 14 July 2021. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_AnnexI_Glossary.pdf

- Kaufmann, V., Bergman, M. M., & Joye, D. (2004). Motility: Mobility as capital. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(4), 745–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00549.x

- Kelly, P. F. (2013). Migration, agrarian transition, and rural change on Southeast Asia. Routledge.

- Kniveton, D. R., Smith, C. D., & Black, R. (2012). Emerging migration flows in a changing climate in dryland Africa. Nature Climate Change, 2(6), 444–447. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1447

- Lama, P., Hamza, M., & Wester, M. (2021). Gendered dimensions of migration in relation to climate change. Climate and Development, 13(4), 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1772708

- Leal Filho, W., & Nalau, J. (2018). Limits to climate change adaptation (climate change management). Springer.

- Le De, L., & Friesen, W. (2013). Remittances and disaster: A review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 4, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2013.03.007

- le Polain de Waroux, Y. (2019). Livelihoods through the lens of telecoupling telecoupling. In C. Friis and J. Ø. Nielsen (Ed.) Palgrave studies in natural resource management (pp. 233–249). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Leyk, S., Runfola, D., Nawrotzki, R., Hunter, L., & Riosmena, F. (2017). Internal and international mobility as adaptation to climatic variability in contemporary Mexico: Evidence from the integration of census and satellite data. Population, Space and Place, 23(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2047.

- Magnan, A. K., Schipper, E. L. F., & Duvat, V. K. E. (2020). Frontiers in climate change adaptation science: Advancing guidelines to design adaptation pathways. Current Climate Change Reports, 6(4), 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-020-00166-8

- Maharjan, A., de Campos, R. S., Singh, C., Das, S., Srinivas, A., Bhuiyan, M. R. A., Ishaq, S., Umar, M. A., Dilshad, T., Shrestha, K., Bhadwal, S., Ghosh, T., Suckall, N., & Vincent, K. (2020). Migration and household adaptation in climate-sensitive hotspots in south Asia. Current Climate Change Report, 6, 1–16.

- Mallick, B., Rogers, K. G., & Sultana, Z. (2021). In harm’s way: Non-migration decisions of people at risk of slow-onset coastal hazards in Bangladesh. Ambio, (5), 114–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01552-8

- Mallick, B., & Schanze, J. (2020). Trapped or voluntary? Non-migration despite climate risks. Sustainability, 12(11), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114718.

- Marcus, G. E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523

- Massey, D. S., & Zenteno, R. (2000). A validation of the ethnosurvey: The case of Mexico-U.S. Migration. The International Migration Review, 34(3), 766–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791830003400305

- McLeman, R. (2016). Conclusion: Migration as adaptation: Conceptual origins, recent developments, and future directions. In A. Milan, B. Schraven, K. Warner, & N. Cascone (Eds.), Migration, risk management and climate change: Evidence and policy responses (Global migration issues 6) (pp. 213–229). Springer.

- McLeman, R., & Smit, B. (2006). Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Climatic Change, 76(1-2), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-005-9000-7

- McLeman, R., Wrathall, D., Gilmore, E., Thornton, R., Adams, H., & Gemenne, F. (2021). Conceptual framing to link climate risk assessments and climate-migration scholarship. Climatic Change, 165(1-2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03056-6.

- McNamara, K. E., Westoby, R., & Smithers S, G. (2017). Identification of limits and barriers to climate change adaptation: Case study of two islands in Torres Strait, Australia. Geographical Research, 55(4), 247–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12242

- Mechler, R., Singh, C., Ebi, K., Djalante, R., Thomas, A., James, R., Tschakert, P., Wewerinke-Singh, M., Schinko, T., Ley, D., Nalau, J., Bouwer L, M., Huggel, C., Huq, S., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Surminski, S., Pinho, P., Jones, R., Boyd, E., & Revi, A. (2020). Loss and damage and limits to adaptation: Recent IPCC insights and implications for climate science and policy. Sustainability Science, 15(4), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00807-9

- Meyer, N. (2002). Environmental refugees: A growing phenomenon of the 21st century. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 357(1420), 609–613. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2001.0953

- Mohapatra, S., & Ozden, C. (2009). Migration and Remittances in South Asia. The Service Revolution in South Asia (World Bank, Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit, South Asia Region). pp 199–223.

- Musah-Surugu, I. J., Ahenkan, A., Bawole, J. N., & Darkwah, S. A. (2018). Migrants’ remittances. A complementary source of financing adaptation to climate change at the local level in Ghana. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 10(1), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-03-2017-0054

- Nawrotzki, R. J., Riosmena, F., Hunter, L. M., & Runfola, D. M. (2015a). Undocumented migration in response to climate change. International Journal of Population Studies, 1(1), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.18063/IJPS.2015.01.004

- Nawrotzki, R. J., Riosmena, F., Hunter, L. M., & Runfola, D. M. (2015b). Climate change as migration driver from rural and urban Mexico. Environmental Research Letters, 10(11), Article 114023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/114023

- Nawrotzki, R. J., Riosmena, F., Hunter, L. M., & Runfola, D. M. (2015c). Amplification or suppression: Social networks and the climate change – Migration association in rural Mexico. Global Environmental Change, 35, 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.002

- Nawrotzki, R. J., Runfola, D. M., Hunter, L. M., & Riosmena, F. (2016). Domestic and international climate migration from rural Mexico. Human Ecology, 44(6), 687–699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-016-9859-0

- Osbahr, H., Twyman, C., Adger, W. N., & Thomas, D. S. (2008). Effective livelihood adaptation to climate change disturbance: Scale dimensions of practice in Mozambique. Geoforum, 39(6), 1951–1964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.07.010

- Parsons, L. (2019). Structuring the emotional landscape of climate change migration: Towards climate mobilities in geography. Progress in Human Geography, 43(4), 670–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518781011

- Parsons, L., & Brickell, K. (2020). The spirit in the machine: Towards a spiritual geography of debt bondage and labour (im)mobility in Cambodian brick kilns. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 46(1), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12393

- Pemberton, S., Furlong B, T., Scanlan, O., Koubi, V., Guhathakurta, M., Hossain, K., Warner, J., & Roth, D. (2021). ‘Staying’ as climate change adaptation strategy: A proposed research agenda. Geoforum, 121, 102–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.02.004

- Peter, K. B. (2010). Transnational family ties, remittance motives, and social death among Congolese migrants: A socio-anthropological analysis. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.41.2.225

- Peth, S. A. (2020). Migration and Translocal Resilience: A multi-sited analysis in/between Thailand, Singapore and Germany [PhD thesis]. University of Bonn.

- Peth, S. A., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2020). Resilient family meshwork. Thai–German migrations, translocal ties, and their impact on social resilience. Geoforum, 114, 19–29. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.05.019

- Peth, S. A., Sterly, H., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2018). Between the village and the global city: The production and decay of translocal spaces of Thai migrant workers in Singapore. Mobilities, 13(4), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2018.1449785

- Phillips, C.A., Caldas, A., Cleetus, R., Dahl, K. A., Declet-Barreto, J., Licker, R., Merner, L. D., Ortiz-Partida, J. P., Phelan, A. L., Spanger-Siegfried, E., Talati, S., Trisos, C. H., & Carlson, C. J. (2020). Compound climate risks in the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Climate Change, 10(7), 586–588. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0804-2

- Piguet, E. (2011). Migration and climate change. Cambridge University Press.

- Plaza S. 2019. Migration, remittances and diaspora resources in crisis and disaster risk finance (The World Bank). Retrieved 14 July 2021. https://www.preventionweb.net/news/view/69687

- Porst L. 2020. Translocal resilience in a changing environment. Rural–urban migration, livelihood risks, and adaptation in Thailand [PhD thesis]. University of Bonn.

- Porst, L., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2018). Advancing adaptation or producing precarity? The role of rural-urban migration and translocal embeddedness in navigating household resilience in Thailand. Geoforum, 97, 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.10.011

- Porst, L., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2020). Gendered translocal connectedness: Rural–urban migration, remittances, and social resilience in Thailand. Population, Space and Place, 26(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2314.

- Ratha, D, De, S, Kim, E. J., Plaza, S, Seshan, G and Yameogo, N. D. 2020. Migration and Development Brief 33: Phase II: COVID-19 Crisis through a Migration Lens (Washington, DC: KNOMAD-World Bank). Retrieved 12 December 2022. https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/Migration%20%26%20Development_Brief%2033.pdf

- Reeves, M. (2011). Staying put? Towards a relational politics of mobility at a time of migration. Central Asian Survey, 30(3-4), 555–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2011.614402

- Rigg, J., & Vandergeest, P. (2012). Revisiting Rural Places: Pathways to Poverty and Prosperity in Southeast Asia. Challenges of Agrarian Transition in Southeast Asia (ChATSEA) (University of Hawaii Press).

- Rockenbauch, T. (2022). Networks, translocality, and the resilience of rural livelihoods in Northeast Thailand [PhD thesis]. University of Bonn.

- Rockenbauch, T., Sakdapolrak, P., & Sterly, H. (2019a). Do translocal networks matter for agricultural innovation? A case study on advice sharing in small-scale farming communities in northeast Thailand. Agriculture and Human Values, 36(4), 685–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09935-0

- Rockenbauch, T., Sakdapolrak, P., & Sterly, H. (2019b). Beyond the local – Exploring the socio-spatial patterns of translocal network capital and its role in household resilience in Northeast Thailand. Geoforum, 107, 154-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.09.009

- Runfola, D. M., Romero-Lankao, P., Leiwen, J., Hunter, L., Nawrotzki, R., & Landy, S. (2016). The influence of internal migration on exposure to extreme weather events in Mexico. Society & Natural Resources, 29(6), 750–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1076918

- Sakdapolrak, P., Naruchaikusaol, S., Peth S, A., Porst, L., Rockenbauch, T., & Tolo, V. (2016). Migration in a changing climate. Towards a translocal social resilience approach. Die Erde, 147(2), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.12854/erde-147-6

- Sakdapolrak, P and Sterly, H. (2020). Building Climate Resilience through Migration in Thailand. Migration Information Source. Retrieved 14 July 2021. www.migrationpolicy.org/article/building-climate-resilience-through-migration-thailand

- Savage, K., & Harvey, P. (2007). Remittances during crises. Implications for humanitarian response hpg. Briefing Paper 26 (Humanitarian Policy Group).

- Scheffran, J., Marmer, E., & Sow, P. (2012). Migration as a contribution to resilience and innovation in climate adaptation: Social networks and co-development in northwest Africa. Applied Geography, 33, 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.10.002

- Schewel, K. (2020). Understanding immobility: Moving beyond the mobility bias in migration studies. International Migration Review, 54(2), 328–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918319831952

- Sheller, M. (2018). Mobility justice: The politics of movement in an age of extremes (Verso).

- Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006). The New mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38(2), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37268

- Siddiqui, T., Szaboova, L., Adger, W. N., de Campos, R. S., Bhuiyan, M. R. A., & Billah, T. (2020). Policy opportunities and constraints for addressing urban precarity of migrant populations. Global Policy, 12(S2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12855

- Spilker, G., Nguyen, Q., Koubi, V., & Böhmelt, T. (2020). Attitudes of urban residents towards environmental migration in Kenya and Vietnam. Nature Climate Change, 10(7), 622–627. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0805-1

- Stillmann, S., Gibson, J., McKenzie, D., & Rohorua, H. (2015). Miserable migrants? Natural experiment evidence on international migration and objective and subjective well-being. World Development, 65, 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.07.003

- Surhardiman, D., Rigg, J., Bandur, M., Marschke, M., Miller, M. A., Pheuangsavanh, N., Sayatham, M., & Taylor, D. (2021). On the coattails of globalization: Migration, migrants and COVID-19 in Asia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(1), 88–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1844561

- Sydney C. (n.d). COVID-19, a risk multiplier for future distress migration and displacement? The COVID-19 pandemic, migration and the environment. Retrieved 12 December 2022: https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/blogs/covid-19-risk-multiplier-future-distress-migration-and-displacement

- Tacoli, C. (2009). Crisis or adaptation? Migration and climate change in a context of high mobility. Environment and Urbanization, 21(2), 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247809342182

- Tacoli C. (2011). Migration and global environmental change. CR2: The links between environmental change and migration: a livelihoods approach (Foresight). Retrieved 14 July 2021. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20121206060716/http://www.bis.gov.uk/assets/foresight/docs/migration/case-study-reviews/11-1191-cr2-links-environmental-change-and-migration-livelihoods.pdf

- van Praag, L. (2021). Can I move or can I stay? Applying a life course perspective on immobility when facing gradual environmental changes in Morocco. Climate Risk Management, 31, Article 100274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100274

- Vinke, K., Bergmann, J., Blocher, J., Upadhyay, H., & Hoffmann, R. (2020). Migration as adaptation? Migration Studies, 8(4), 626–634. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaa029

- Warner, B. P., Kuzdas, C., Yglesias, M. G., & Childers, D. L. (2015). Limits to adaptation to interacting global change risks among smallholder rice farmers in northwest Costa Rica. Global Environmental Change, 30, 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.11.002

- Warner, K. (2012). Human migration and displacement in the context of adaptation to climate change: The Cancun adaptation framework and potential for future action. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 30(6), 1061–1077. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1209j

- Warner, K., & Afifi, T. (2014). Where the rain falls: Evidence from 8 countries on how vulnerable households use migration to manage the risk of rainfall variability and food insecurity. Climate and Development, 6(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2013.835707

- Western, M., & Tomaszewski, W. (2016). Subjective wellbeing, objective wellbeing and inequality in Australia. PLoS ONE, 11(10), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163345.

- White, S. C. (2010). Analysing wellbeing: A framework for development practice. Development in Practice, 20(2), 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520903564199

- Wiederkehr, C., Beckmann, M., & Hermans, K. (2018). Environmental change, adaptation strategies and the relevance of migration in Sub-Saharan drylands. Environmental Research Letters, 13(11), Article 113003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aae6de

- Wrathall, D., Bury, J., Carey, M., Mark, B., McKenzie, J., Young, K., Baraer, M., French, A., & Rampini, C. (2014). Migration amidst climate rigidity traps: Resource politics and social–ecological possibilism in Honduras and Peru. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104(2), 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2013.873326

- Wrathall, D., Oliver-Smith, A., Sakdapolrak, P., Gencer, E., Fekete, A., & Reyes M, L. (2013). Problematising loss and damage. International Journal of Global Warming, (2), 274–294. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGW.2015.071962

- Zickgraf, C. (2018). Immobility. In R. McLeman & F. Gemenne (Eds.), Routledge handbook on environmental displacement and migration (pp. 71–84). Routledge.

- Zickgraf, C. (2019a). Keeping people in place: Political factors of (im)mobility and climate change. Social Sciences, 8(8), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8080228

- Zickgraf, C. (2019b). Climate change and migration crisis in Africa. In C. Menjívar, M. Ruiz, & I. Ness (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of migration crises part IV climate and environment. Oxford University Press.