ABSTRACT

Women's contributions to rangeland cultivation in Tunisia and the effects of climate change upon their livelihoods are both policy blind spots. To make women's contributions to rangeland cultivation visible and to provide policy inputs based on women's needs and priorities into the reforms currently being made in the pastoral code in Tunisia, we conducted fieldwork in three governorates. We conducted focus groups and interviews with 289 individuals. We found that men and women are negatively affected by rangeland degradation and water scarcity, but women are additionally disadvantaged by their inability to own land and access credit and by drought mitigation and rangeland rehabilitation training that only target men. Women are involved in livestock grazing and rearing activities to a greater extent than is assumed in policy circles but in different ways than the men from the same households and communities. Understanding how women use rangelands is a necessary first step to ensuring that they benefit from rangeland management. Women's growing involvement in livestock rearing and agricultural production must be supported with commensurate social and economic policy interventions. Providing all farmers with appropriate support to optimize rangeland use is particularly urgent in the context of resource degradation accelerated by climate change.

Introduction

Livestock rearing is an important livelihood strategy for rural communities all over the world. Particularly in developing countries, livestock often serve as assets, capital, and “insurance policies” of rural people with poor access to formal financial institutions and high vulnerability to crop failures (Njuki & Sanginga, Citation2013). Livestock rearing can be an important component of building household and community resilience (Dumas et al., Citation2018). Livestock rearing tends to be a significant (if not the primary) livelihood activity for rural households and communities located in areas that are dry, or that have more extreme climates where crop cultivation is not as reliable (Archambault, Citation2016; Turner & Williams, Citation2002). Livestock may also be integral to crop production in some contexts and therefore to livelihood security (Debela, Citation2017; Fisher et al., Citation2000). In both dry and non-dry areas, livestock can serve as a reliable food source by providing milk and meat and as a support for agricultural work, for example by providing traction for carts and pulleys and manure for fertilization of crops, thereby serving as a security mechanism which allows households to earn income and build resilience (Archambault, Citation2016; Curry et al., Citation1996; Dumas et al., Citation2018; Fisher et al., Citation2000; Njuki & Sanginga, Citation2013; Thomas-Slayter, Citation1994; Turner & Williams, Citation2002). Livestock rearing and production is estimated to produce 33% of global agricultural GDP (Galie et al., Citation2018). Since 752 million of the world’s rural people own livestock and rearing livestock is often the primary means by which they earn livelihoods (FAO, Citation2013), livestock rearing may represent an even higher percentage of agricultural output in developing countries.

Livestock rearing is particularly important for pastoral populations inhabiting desert and dry climates. Although pastoral populations in dryland areas are some of the most resilient communities in the world, existing ecological stressors such as overgrazing and desertification that are at least partially associated with livestock production have been exacerbated by climate change in some contexts, including in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (Läderach et al., Citation2022). Consequently, an increasing number of dryland areas may be subjected to drought conditions in the future (Fraser et al., Citation2011). Dryland areas in some contexts may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change because of their low adaptive capacity and higher sensitivity to changes in temperature and precipitation (ibid.). By rendering grasslands and rangelands less productive, climate change will adversely affect dairy, meat and wool production (Calvosa et al., Citationn.d., p. 2). Thus, the livelihoods of the 2.5 billion people who inhabit dryland areas are particularly vulnerable to climate change (Fraser et al., Citation2011). Since the effects and outcomes of climate change have been demonstrated to be borne more heavily by women, often as a result of the household and societal division of labour, improving women’s ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions is critical (Alexander et al., Citation2011; Carr & Thompson, Citation2014). Climate change also interacts with structural barriers such as tenure insecurity, credit inaccessibility, limited access to agricultural inputs and improved technologies to the disadvantage of women (Carr & Thompson, Citation2014).

In some dry areas, a combination of climatic change and population growth have led to increased male and youth outmigration to cities and towns among rural populations who depend on rainfed agriculture (Abdelali-Martini & Hamza, Citation2014; Afifi et al., Citation2016; Kristensen & Birch-Thomsen, Citation2013; Radel et al., Citation2012). A report published by the International Centre for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas (ICARDA) of the proceedings from the International Conference on Food Security in Dry Lands held in Qatar in 2012 emphasized that populations that inhabit deserts and dry rural areas of the world are most likely to experience male outmigration to urban areas due to the effects of climate change and to subsequently witness the “feminization of agriculture,” a rise in the participation of women in agriculture, often borne of necessity (Pedrick, Citation2012). Other recent research affirm these trends (Abdelali-Martini & Hamza, Citation2014; Gartaula et al., Citation2010; Pattnaik et al., Citation2018). Male outmigration strongly influences women’s roles in agriculture, with associated implications for agricultural productivity and gender equity. Although the effects that climate change and male outmigration have upon women’s roles in agriculture and livestock production have been studied in several MENA countries, very little is known about these topics in the context of Tunisia. For example, the World Bank Atlas’s factsheet on gender and agriculture in Tunisia was last updated in 1994. We attempt to contribute to this topic with empirical research conducted in three rural communities in Tunisia. We examine the impacts of climate change on women and men in these communities, we document their strategies for responding to climate change along with the resources and services available to them, and we identify ways to build resilience within the context of increased involvement of women in rangeland cultivation and livestock rearing.

Study background

In Tunisia, rangelands occupy nearly 5.5 million hectares of land. They cover 80% of the arable land, and 35% of the total area of the country (Jaouad, Citation2009). About 3.7 million hectares of this total rangeland area are in the six arid governorates of southern Tunisia, which receive on average less than 200 mm of rain annually (Fetoui et al., Citation2021). The southern region of Tunisia accounts for about 800,000 hectares of arable land and about 17,000 hectares of forests. These arable lands and forests are mostly integrated within rangelands and around oases that help protect the land from desertification. Thus, almost all land in the dry regions in Tunisia are classified as rangelands. Over the past 30 years, the total area of rangeland has decreased by 30% (Jaouad, Citation2009). The expansion of intensive agriculture and the increase in size of livestock herds have resulted in a continuous reduction of the natural vegetation cover and consequent degradation of the physical environment and increased desertification (Croitoru & Daly-Hassen, Citation2015). Rangelands are critical for the livelihoods of livestock farmers in southern Tunisia. Farmers in this region owned 1.3 million sheep and 564,330 goats in 2018 (OpenGeoData Tunisie, Citation2018). However, the rangeland area in southern Tunisia is only capable of producing 10 to 20% of livestock feed requirements (Fetoui et al., Citation2021). Medenine and Tataouine, two communities selected for this study, are in southern Tunisia. Zaghouan is in northern Tunisia.

In addition to livestock production, rangelands in Tunisia are habitats for a diversity of flora and fauna of socio-cultural, environmental and economic importance. Forests and rangelands in Tunisia generate an estimated economic value of USD 500 million per year, equivalent to 14% of agricultural GDP in 2012 (World Bank, Citation2015). Rangelands and forests provide about 38% of incomes of households living close to them, and about 5 to 7 million working days per year, equivalent to 35,000 permanent jobs benefiting approximately 100,000 rural households (ibid). Rangelands also provide various ecosystem services including water retention, protection against desertification, carbon sequestration and biodiversity (ibid).

We were aware of many background facts about the three communities included in this study before undertaking the fieldwork. For example, we knew that residents of Zaghouan relied on crop production (olives, wheat and rapeseed) and livestock production to sustain livelihoods. Due to drier conditions in southern Tunisia, the potential for crop production for both food and fodder was much lower in Medenine and Tataouine so these communities were more dependent on livestock production. Milk-based products (butter and ghee) were more economically important than crop products (olive oil and dried figs) in Medenine. In Tataouine, crop production featured even less prominently as low water tables, soil erosion and desertification prevented crop cultivation. Instead, camel rearing as well as sheep and poultry production constituted the most viable economic activities. Due to their relatively higher dependence on rangelands for livestock production and consequently higher vulnerability to climate change, the southern governorates of Medenine and Tataouine were of particular interest in this study. The comparisons between the three communities – of reliance on rangelands for crop production and livestock systems – allowed us to identify some key issues and concerns for rangeland management in Tunisia.

Methods

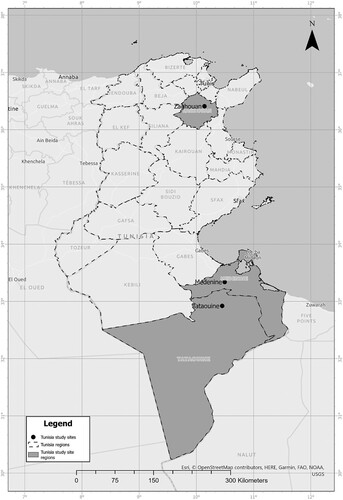

We carried out fieldwork in one northern rural community (Zaghouan) and two southern rural communities (Medenine and Tataouine) in Tunisia to understand the challenges and opportunities faced by women and men in rural areas where livestock rearing constitutes the main or a significant component of livelihood generation (see map of study areas, ). The three communities differ in socio-economic and ecological dynamics. While people in Medenine and Tataouine usually collect livestock feed from the rangelands, in Zaghouan they are more likely to harvest feed and forage from crops such as rapeseed, barley, and wheat. In Tataouine, livestock rearing is often carried out at a commercial scale: the average number of livestock owned by a household in Tataouine is 82, whereas on average the herd sizes are 13 in Medenine and 9 in Zaghouan. Taking a comparative approach toward the three communities enables us to identify diverse experiences not just of women’s involvement in livestock rearing but also gendered impacts and outcomes of climate change, rendering our recommendations relevant for a diverse array of dry and desert communities in the MENA region.

Rural communities rarely own cattle in Tunisia. In 2018, cattle represented only 7% of the livestock in Tunisia (Statista, Citation2002), and none of the three communities we studied owned cattle. Thus, when we refer to livestock in this paper, we are referring to sheep, goats, and camels, but not cattle. Although poultry is reared to a smaller extent in all three communities and may be counted as livestock, we found reliable data about poultry ownership difficult to procure because of their higher mortality rates compared to other livestock. Poultry was also consumed as meat much more frequently than other livestock, so poultry owners often could not provide us with precise data about flock size.

In our study, we also sought to understand the coping mechanisms employed by women and men farmers to contend with challenges in livestock rearing. A total of 289 individuals participated in the study between 2018 and 2020 as per and . In Tataouine, interviews were conducted in early 2020; but the COVID 19 pandemic prevented us from conducting focus groups there.

Table. 1. Interviews conducted in the three regions.

Table 2. Focus groups conducted in Medenine and Zaghouan.

The interviews with men and women farmers were designed to help us gather information about the size of livestock herds, women’s and men’s roles in agriculture and livestock rearing, patterns of land access and ownership by gender, as well as the perceptions among women and men of the impacts of climate change, and the coping strategies they employed to respond. Respondents were first asked if they had observed any ecological changes to the rangelands in the past decade and then asked to identify if and what they were doing (or trying to do) to respond to the identified changes. In some interviews, we provided a few examples of ecological changes (for example, changes in temperature and edaphic conditions, changes in precipitation patterns such as rains starting earlier or later in the year) and asked if respondents recognized any such changes in their communities in the past ten years.

Every effort was made to complete separate interviews with women and men spouses from the same households. However, this was often not possible because one spouse was away from home or otherwise occupied and unable to participate in the study. In total, 19 sets of spouses were interviewed. The rest of the interviews were conducted with only one head of household. Each interview lasted between one hour and 90 minutes.

The focus groups were gender-segregated to respect community norms and to ensure that women and men could participate more freely. Focus group participants were, therefore, not from the same household. Focus group questions were designed to improve our understanding of gender norms and agency and their implications for adoption of agricultural innovations and technologies and participation in community development and governance programmes. Each focus group lasted approximately two hours.

In addition, in each of the three regions, key informant interviews were conducted with two community leaders (one woman and one man) to understand the types of agricultural programmes and services available in each community as well as information about key crops, agricultural products, and access to markets. Each key informant interview lasted between one and two hours.

The lead author of this paper serves as a senior gender scientist for ICARDA. Recognizing a need to integrate gender more effectively into Tunisia’s livestock and rangeland management projects and policies, ICARDA brought together key government institutions, local communities, and international actors – under the auspices of the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock – to design practical research tools (interviews and focus groups) to guide research activities. The questions that emerged from this consultation guided our interviews and focus groups for this project, which were aimed at understanding women’s and men’s ownership and control of assets such as land and livestock, access to livelihood training and innovations, their respective roles in grazing of livestock, all within the context of understanding the impacts of climate change and coping strategies. Our premise was that assets, innovations, and trainings all contribute to women and men farmers’ resilience potential, and household and societal roles and responsibilities shape the ways through which climate change impacts rural livelihoods (Alexander et al., Citation2011; Carr & Thompson, Citation2014).

All interviews and focus groups were conducted in Arabic. Four local Tunisian researchers (three women and one man) with extensive experience in conducting qualitative research were recruited to conduct the interviews and focus groups. The primary author conducted in-person training sessions in Tunis to ensure common understanding among the research team of study goals, objectives, and interview and focus group questions. The four researchers worked in pairs to conduct the focus group discussions; one researcher took notes while the other facilitated the discussion.

Respondents to this study were recruited through the Regional Commission for Agricultural Development (CRDA). The gender focal point at the CRDA was particularly helpful in providing the research team with a diverse list of women farmers in the three study communities (for example, women who were married, widowed, divorced, involved in a cooperative, or a development project). The CRDA gender focal point is in an ideal position to do this because she deals directly with rural Tunisian women via training and capacity building activities. We attempted to interview spouses of all married women respondents. As previously noted, we conducted household interviews with 24 sets of spouses. Staff at the CRDA also enabled us to identity local leaders who were knowledgeable about rangeland cultivation, livestock rearing, and community gender dynamics in the three communities, and could be interviewed as key informants for this study.

To generate findings from this study, we used inductive theme identification and explanation building from the interview and focus group data. Inductive thematic analysis entails allowing the themes to emerge from the data (Leavy, Citation2022). We conducted a literature review and background research on gender and rangeland cultivation in Tunisia prior to embarking on fieldwork, but we did not approach the interviews or focus groups with preconceived issues or themes we expected to find based on the literature review. Instead, we allowed the themes and topics to emerge from the interviews and focus groups. We triangulated findings from the primary data (derived from farmer and key informant interviews and focus groups) and secondary (literature review) data to generate external validity for our findings.

In the next section, we describe the nature of women’s and men’s participation in livelihoods dependent on livestock rearing and rangeland cultivation (defined in this study as agriculture or crop production for food or fodder) in the three communities included in our study. We tried to understand women’s participation in livestock rearing, as well as gender patterns in ownership and control of assets (namely land and livestock) in the study areas. We also tried to understand any shifts in gender roles owing to changing climatic conditions; their implications for people’s lives; coping mechanisms adopted by women and men to respond to changes in climatic conditions; and opportunities and constraints they face in accessing and adopting new innovations in agriculture that had been introduced in their communities in the past five years.

We organized findings from our study in the order in which the issues emerged during the fieldwork. Although we present our findings from the study under specific headings, we ask that the reader approach the themes and sub-themes with their interrelatedness and mutual inclusivity in mind.

Findings and discussion

We provide an overview of our findings and their implications in this section drawing from interviews and focus groups discussions (summarized in and below). We only identify the type of research instrument when drawing from focus groups and key informant interviews; otherwise all reported findings are drawn from household interviews.

Table 3. Overview of findings from household interviews conducted in three research sites.

Table 4. Overview of findings from focus groups conducted in Medenine and ZaghouanTable Footnotea.

Women’s participation in rangeland cultivation and livestock rearing

We found that women in Medenine were more actively involved in all rangeland cultivation activities than in Zaghouan. This may be because Medenine experiences higher levels of male outmigration as well as more off-farm work opportunities for men, which women may not be able to access at par with men due to cultural norms of seclusion prevalent in most rural communities in the MENA region that discourage women from associating with non-related men and working in mixed-gender environments (see, for example, Najjar et al., Citation2018b). Thus, while 93% (N = 30) of wome respondents in Medenine indicated that they were involved in all agricultural activities (namely, planting, plowing, pruning, harvesting), 84% (N = 19) of women respondents in Zaghouan said the same. In Tataouine, none of the women respondents (N = 30) indicated being involved in these activities (see ). The low levels of women’s involvement in agriculture in Tataouine may be attributable to limited crop production in the community and much higher reliance on livestock as the mainstay of local livelihoods. Lower levels of male outmigration from Zaghouan corresponded with higher levels of men's participation and lower levels of women’s participation in agricultural activities. The higher levels of women’s participation in agriculture in Medenine may also be a consequence of the finding (discussed in more detail later in the paper) that Medenine is more dependent on rangelands for grazing livestock than Zaghouan, where crop production is more feasible. Participants in Medenine also reported a lack of youth engagement in agriculture and a reduction in size of livestock herds over the years due to increases in feed prices and limited availability of labour. Thus, although grazing livestock is traditionally considered a male activity and women did not report grazing as a key activity in Medenine, men from the same community identified grazing as increasingly becoming women’s responsibility. Women respondents in Medenine did report grass collection, which entails collection of alternative feed from rangelands, as an important activity carried out by women. In Tataouine, men were deemed solely responsible for camel rearing while women, especially if the herd size was smaller, took on responsibility for goats and poultry rearing.

Women and men respondents in all three communities, namely Medenine, Tataouine and Zaghouan, identified feeding and milking livestock, processing dairy products, and cleaning of barns as activities carried out more exclusively by women. Women and men respondents in both communities identified men as almost exclusively responsible for marketing, particularly for selling and purchasing livestock, feed, and other inputs such as fertilizer. However, both women and men respondents noted that women in Medenine were also increasingly performing these market roles, albeit to a lesser extent than the men in their families. This is also probably a consequence of male outmigration and declining participation for men (including youth) in agriculture in Medenine. This resonates with our finding that the average age for men farmers in Medenine was 57 years versus 45 years for women.

Asset ownership and decision-making power

Since livestock rearing and production depends on access to or ownership of land, we attempted to identify patterns of land access, ownership and control based on gender for two types of land (private plots and collective lands). Our findings reveal that private plots are mostly owned by men in the three communities. Since individual land plots are inherited intergenerationally primarily by men (and often in undivided form), we found that some men may own land jointly with other male members of the extended household (father, siblings or cousins, for example) but rarely with spouses or women relatives: “When we talk about inheritance in southern Tunisia we do not talk about the law or religion, we talk about customs: sisters want to preserve natal relations with their brothers and avoid conflict over property and resources, as such they do not claim their legal or religious rights to land,” explained a key informant from Tataouine. These findings are consistent with other countries in the MENA region (see, for example, Najjar et al., Citation2018b for findings from Morocco and Najjar et al., Citation2020 for findings from Egypt).

Nonetheless, women and men respondents in the three areas reported being able to access and use land for farming and grazing, irrespective of the gender of the owner. We defined land use as the ability to farm, graze livestock and collect livestock feed. Our findings from these communities suggest that women contribute significantly to livestock and farming despite their limited ownership of land. This finding may also explain why women have more equitable access with men to rangelands collectively owned by communities.

Households owned an average of fewer than 15 head of livestock in Medenine and Zaghouan compared to 82 head on average in Tataouine. Unlike land, larger numbers of women owned livestock in both communities, either independently or jointly with their spouses. Thus, while 30% (N = 30), 52% (N = 21) and 83% (N = 30) of men respondents reported owning livestock in Medenine, Zaghouan, and Tataouine respectively, the corresponding rates were 17% (N = 30) in Medenine, 26% (N = 19) in Zaghouan and 80% (N = 30) in Tataouine for women respondents. In Zaghouan women mostly owned sheep (63%, N = 19) while they were more likely to own goats in Tataouine and Medenine (63%, N = 30 and 73%, N = 30) respectively. Goats are cheaper to rear since they can thrive on less expensive feed. Women who owned livestock had either inherited them from parents, purchased livestock independently or with a family member with their own savings, received them as gifts from spouses or from a livestock development project. These findings about women’s ownership of livestock in Tunisia resonate with those from Egypt (Najjar et al., Citation2020) which emphasize that “there is a much stronger entrenched perception of land as a male asset than livestock (p.14).” However, a different scenario presents itself for camels, which are only reared in the Tataouine site and owned exclusively by men. We found only one woman who owned camels in Tataouine. Findings that women were more likely to own smaller livestock, particularly goats, were also reported elsewhere in previous studies in the MENA region (for example, see Najjar et al., Citation2019b for findings from Jordan).

Women also had significant agency over livestock acquisition and use, which we define as the ability to decide to buy, sell, butcher, or trade livestock. Male respondents in both communities reported joint-decision making with their spouses much more frequently for livestock than for land. This study in Tunisia revealed other details specific to the region and type of livestock. For example, both men and women were more likely to report joint-decision-making for goats than for sheep. Households in Tataouine were the least likely to report joint decision-making, especially with regard to camels, which were almost exclusively controlled by men. Additionally, women and men respondents provided different reasons for consulting with their spouses about decisions relating to livestock. Men explained that they consulted with their spouses about livestock because their spouses did most of the feeding and tending of livestock. However, women were more likely to justify consulting with their husbands in order to abide by traditional patriarchal social norms of male household headship: “I consult with my husband for any big or small issue. Even if I want to get water, before he leaves to work, I tell him that I will be getting water today. We discuss to make decisions, but the final decision belongs to my husband.” These findings suggest that “jointness” in decision making may mean different things to women and men (see also similar findings by Acosta et al., Citation2019) and may not translate into equity in decision making. Similar findings have been reported from other recent studies on gender patterns in land and asset ownership in the MENA region (see, for example, Najjar et al., Citation2020). Our findings in Tunisia also urge us to recommend that future research on gender and asset ownership consider various forms of sole and joint ownership (with, for example, spouses, family members, and friends) through which women and men may own and control assets. We simultaneously encourage researchers to be cognizant that joint ownership does not necessarily imply equal ownership (Doss et al., Citation2014; Jacobs and Kes Citation2015).

Impacts of climate change upon livelihoods

Almost everyone we interviewed for this study observed changes in the rangelands such as rising temperatures, reduced precipitation, soil erosion and other manifestations of climate change in the past ten years. We asked women and men from the three communities to reflect upon effects in their lives and livelihoods due to these changes. We also asked them if gender roles had changed owing to the effects caused or exacerbated by climate change. Irrespective of gender, respondents reported that climate change has led to reduced crop yields and crop failure, reduced purchasing power due to higher dependence on purchased feed, reduced grazing time due to higher temperatures and degradation of rangelands, reduced work opportunities in the rangelands, greater fatigue among women due to the extra work involved in fetching fodder from farther locations, and a loss of interest and hope in rangeland cultivation and livestock production as viable livelihoods, particularly among young people.

Both women and men respondents reported that although women’s greater involvement in activities such as grazing and gathering grass as livestock feed had become more noticeable in Medenine in recent years, women in Zaghouan had also become more actively engaged in agriculture and livestock rearing because of male outmigration. Men from the three communities were reported to be leaving in greater numbers in recent years for off-farm opportunities in the cities, in manufacturing, for example. Men respondents from all three communities noted that the land available for rangeland cultivation and livestock rearing had shrunk because of increased tree planting, particularly of olive trees, which many farmers had resorted to in order to slow down soil erosion and desertification, especially in Tataouine. They reported that tree planting was a labour – and capital-intensive activity, often entailing hiring of men labourers fulltime for a stretch of 20 or more days. Although tree planting helps slow down soil erosion and desertification, it simultaneously leads to a reduction in rangeland available for livestock grazing and feed collection. Thus, in addition to having to pay labourers for planting trees, farmers who adopted tree planting as a means to prevent the further degradation of rangelands, also ended up having to purchase more livestock feed from the market in all three communities.

Coping strategies employed by women and men

The MENA region is extremely vulnerable to climate change. It is projected to experience a 10 to 30% decrease in precipitation in the coming years, leading to a subsequent decline in groundwater replenishment and severely overexploited aquifers (Haddad & Shideed, Citation2013; Sowers et al., Citation2011; Schilling et al., Citation2020). The combined effects of reduced precipitation and higher temperatures are expected to affect agricultural production negatively (Haddad & Shideed, Citation2013; Sowers et al., Citation2011). The MENA region is already the most water-stressed region in the world. In more than half the countries in the MENA region, average per capita water availability is lower than the water scarcity threshold (Sowers et al., Citation2011). Since agriculture as an industry is a major consumer of water, water scarcity will have dire effects upon the region’s agricultural productivity (Waterbury, Citation2013; Haddad et al. Citation2011; Schilling et al., Citation2020).

Although the effects of climate change upon agriculture are well documented for the MENA region, far less is known about the impacts of climate change on livestock production. To the best of our knowledge, coping responses to climate change employed by those who rely on livestock in Tunisia for their livelihoods have not previously been researched and documented. We attempted to understand general and gendered coping mechanisms that have emerged as a response to climatic changes in the three communities we studied in Tunisia. Women and men respondents reported similar changes in the climate: hotter summers, increased drought incidence, erratic rainfall, and reduced rainfall. The outcomes of such changes identified by the men who participated in our study included reduced oil yield from olives; erosion and degradation of rangelands; reduced profitability of agriculture; higher dependency on purchased feed; and inability to irrigate olive trees adequately, resulting in higher tree deaths. Men respondents also reported having to irrigate more often at night in order to avoid uncomfortably high temperatures and evaporation of water during daytime. Women and men respondents reported having to walk farther away from home and spending more time collecting feed for livestock since rangelands had become less productive. Men often grazed their livestock so far from home that they had to sleep elsewhere overnight, with negative consequences for their health and concerns for their safety. Due to norms of propriety and gendered caregiving responsibilities, women were not at liberty to explore this option even when there were no men in the households who could graze livestock. Women and men respondents reported trying to reduce water use in various ways (reusing bath water to water crops, for example); looking for alternative water sources; and storing more food in anticipation of reduced yields, lower incomes; and decreasing herd size and cultivation area.

Study respondents also mentioned feeding livestock more often in their stalls to protect them from dehydration and overheating instead of allowing them to graze outdoors. As one respondent noted, “Even the goats feel the heat.” Whereas goats and sheep were left free to graze and defecate in the rangelands previously, higher temperatures were forcing farmers not just to feed livestock and keep them in their stalls for longer periods but also to bathe them occasionally to protect them from overheating. Since women were more likely to be responsible for collecting livestock feed, bathing livestock and cleaning the stalls in which sheep and goats are sheltered, these changes have considerably increased women’s workloads in recent years.

In addition to collecting feed and stall cleaning, our findings revealed that significant numbers of women graze livestock in all three communities: 43% (N = 30), 42% (N = 19) and 80% (N = 30) respectively of women respondents in Medenine, Zaghouan and Tataouine indicated participating in grazing. Such findings contradict misperceptions held in policy circles, including those expressed in the stakeholder workshop preceding our study, that women rarely carry out livestock grazing activities. Failing to consider women’s needs and priorities in formulating policy about rangelands not only deprives women of voice and representation in policymaking, but also deprives rangeland management policy of women’s insights and knowledge.

Focus groups (FGs) conducted in Medenine and Zaghouan revealed that women are interested in participating in consultation meetings on how to improve the management of rangelands. Women respondents identified practicing the following measures to improve the quality of rangelands: leaving the land fallow for longer periods of time; creating and maintaining alternating grazing and fallow zones; avoiding grazing during the flowering period; and cultivating feed on areas designated as farming plots rather than on rangelands (these responses were generated via 5 FGs with women (1 in Zaghouan and 4 in Medenine), N = 52). Male respondents in Medenine (4 FGs, N = 38) reported following the same measures as women. They also reported cultivating barley (1 FG Zaghouan, N = 11) in rangelands for livestock to graze on and planting olive trees (1 FG Zaghouan, N = 11) to control erosion and desertification.

Lack of gender equity and nepotism in rangeland policy and programmes

Women frequently reported that their needs were ignored in rangeland development projects and programmes. Some respondents also reported nepotism in the delivery of projects and programmes. As an example, respondents spoke of a project called PRODESUD (Programme for Agro-pastoral Development and Promotion of Local Initiatives in the South-East), which provides (among other services) farmers with feed as compensation for keeping their lands fallow for the season (mentioned by 1 FG in Medenine, N = 10). While endorsing the value of the PRODESUD project to farmers and the rangelands, both women and men repondents noted that the beneficiaries had been selected based on nepotism and were often not the neediest farmers in the community. PRODESUD is a large project (worth USD 36 million) funded via loans from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and administered collaboratively by the Government of Tunisia’s Ministry of Agriculture in collaboration with the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS). In Tunisia, PRODESUD provides support in five areas: basic infrastructure provision (roads, wells, water and soil conservation); integrated socio-territorial management via community-based agricultural development groups; improvement of livestock supplies and value chains; local initiatives and micro-enterprises; and general programme management and implementation services. Our finding about how nepotism may have compromised the potential of PRODESUD is noteworthy because it does not appear to have been captured in formal evaluations of the project (see, for example, IFAD, Citation2012) which document other shortcomings such as its inability to adequately contribute to the recovery of rangelands or to account for existing social inequalities based on gender and class. The PRODESUD project’s failure to include women was noted repeatedly by the women who participated in our study. It was also corroborated in the formal evaluation of the project carried out in June 2012 by the IFAD’s Independent Office of Evaluation, which emphasizes repeatedly that despite the PRODESUD project’s explicit commitment to gender equality and balance, it failed to benefit women even remotely equitably with men. At completion, PRODESUD reported a total of 46,164 beneficiaries, of whom only 1,915 were women (IFAD, Citation2012). In other words, only 4.14% of PRODESUD’s beneficiaries were women. The same evaluation notes that the proportion of women who participated in some training events of PRODESUD may have been somewhat better, but the absence of gender-disaggregated data about project baselines and outcomes made any progress in women’s inclusion and empowerment impossible to determine. Women’s presence in decision-making roles of the agricultural development groups was also deemed “incipient” by the 2012 IFAD evaluation. Women participants in the focus groups we conducted in both Medenine and Zaghouan emphasized that PRODESUD as well as other rangeland support projects almost exclusively targeted men.

Women participants in the focus groups we conducted listed the following measures as critical for improving livestock production in their communities: support for digging wells (mentioned in 2 FGs with women in Medenine and 2 FGs in Zaghouan, N = 44) and subsidizing feed (mentioned in all FGs with women N = 63); protecting rangelands (mentioned in all FGs with women N = 63) and allowing farmers to graze their livestock on larger tracts of land (they emphasized that although tree planting reduced soil erosion, trees also had the effect of reducing the rangeland available for grazing); providing women with financial and technical support (mentioned in all FGs with women, N = 63) for livestock rearing and dairy production; and introducing measures to control fires on rangelands and to reduce theft of livestock. In addition to prioritizing the protection of rangelands to enable grazing, men respondents also identified the importance of planting cactus as livestock feed (mentioned in 2 FGs with men in Zaghouan, N = 22), creating tree and shrub canopies to provide shade for livestock to rest under (mentioned in 1 FG with men in Medenine, N = 10), improving access to labour to compensate for youth outmigration, and locating feed markets closer to grazing areas to reduce transportation costs (mentioned in 1 FG with men in Medenine, N = 10). Although men did not explicitly identify support for women to participate in livestock rearing and dairy production as a priority, it was clear from our focus group and interview findings that women were already actively engaged in livestock rearing and dairy production, and they were articulating clear needs and priorities for optimizing their productivity. That women’s needs and priorities were frequently ignored or trivialized in rangeland management projects and policies was emphasized repeatedly by women participants in our study.

Access to support services and training

We asked study participants about whether they had access to services such as credit, agricultural extension advice and training, and agricultural innovations. We asked them to indicate whether having access to such services helped them improve their livelihoods and manage stress. We found that very few households accessed credit: only 25% (N = 160, total number of interviews with men and women in the three regions) mentioned having loans. Although most respondents were aware of the availability of credit from lending institutions, they had not considered taking a loan. About 18% (N = 160, total number of interviews with men and women in the three region) of respondents were unaware of the availability of credit.

Study respondents identified religious reasons (that Islam forbids charging and paying interest on loans), the lack of formal land titles to serve as collateral, lack of guarantors for loans, fear of the consequences of failing to repay, lack of stable incomes, and lack of new ideas for generating livelihoods as major reasons for being unwilling or unable to access credit. Women respondents noted being particularly affected by lack of titles to land. As described previously, women in these communities seldom owned land. As one woman respondent noted, “Opportunities to acquire bank loans for private projects are non-existent because women do not own land.”

Agricultural innovations and extension services can alleviate the impacts of climate change and strengthen the resilience of farming communities. Yet, 70% (N = 30) and 81% (N = 21) of men respondents in Medenine and Zaghouan reported not receiving a single visit from extension agents in the past year. In Tataouine, 13% (N = 30) of men respondents were unable to remember ever having met an extension agent. The corresponding numbers for women were even more striking: 93% (N = 30) in Medenine and 95% (N = 19) in Zaghouan reported receiving no visits from extension agents in the past year. In Tataouine, 20% (N = 30) of women respondents were unable to remember ever having met an extension agent.

Since Tunisian culture strongly endorses sex-segregation in social settings, we asked respondents to indicate whether they preferred extension agents of a specific gender. We found that 65% (N = 81, total number of interviews with men in the three regions) of men respondents and 59% (N = 79, total number of interviews with women in the three regions) of women respondents were indifferent to the gender of the extension agent, but 25% (N = 79, total number of interviews with women in the three regions) of women respondents expressed a clear preference for women extension agents. Our findings suggest that although extension agents of any gender, provided they are sensitive and responsive to women’s needs, should be able to serve women effectively, women extension agents may, for cultural and practical reasons, be better suited to reach women with extension advice and training. As one respondent noted: “I prefer a woman extension agent because I feel I can be more comfortable and express myself better with a woman extension agent.” There were also generational differences among women respondents when it came to indifference to the gender of the extension agent or preference for women agents. Young unmarried women were more likely than any other group of women to prefer women extension agents, often due to cultural norms and taboos: “My parents will not accept that I meet with a man. They would prefer that a woman gives advice and training.”

We also asked respondents to identify the types of agricultural extension training they needed. The training prioritized by all respondents correlated well with the training that was already offered by agricultural extension services, for example, on livestock rearing, feeding and disease prevention; bee keeping; organic farming, and tree pruning and disease prevention. One notable exception based on gender was the training on drought and water management, which appear to have been provided almost exclusively to men. While 7% (N = 30) and 5% (N = 19) of women respondents in Medenine and Zaghouan expressed an interest in receiving this type of training, not a single woman respondent reported having received this training in either community. Men respondents also identified as important certain types of training that had not been offered, which included training on credit management (acquiring and repaying loans) and on tree planting and cultivation methods that are compatible with protecting and preserving rangelands. Men respondents also wanted training in cheese making, which is currently only offered to women, to also be made available to men. Both women and men respondents in the three communities requested training in marketing of agricultural products, which was not offered at all presently.

Due to the availability of medicinal and aromatic plants on rangelands, women expressed an interest in acquiring training on distillation techniques for making essential oils and essences. Respondents wanted to pursue these activities as a means of reducing pressure on rangelands through diversification of livelihood options and income streams. Several women expressed a desire to start businesses based on extracting and distilling medicinal and aromatic oils, but they emphasized that they lacked both the business training and adequate knowledge of using plants for medicinal and other therapeutic purposes: “All the information I have are second hand from my husband or from my neighbours. I would like to obtain scientific information from the experts.” Similarly, men respondents expressed an interest in learning skills such as tree planting and pruning, bee keeping, and olive oil harvesting and marketing, that were compatible with rangeland preservation, but that could also lead to livelihood diversification.

When asked to recall the last time each of the respondents had attended a training session, the majority (52%, N = 160, total number of interviews with men and women in the three regions) indicated that they had never attended a training session. Surprisingly, more men on average (57%, N = 30 in Medenine and 71%, N = 21 in Zaghouan and 80%, N = 30 in Tataouine) than women (33%, N = 30 in Medenine, 53%, N = 19 in Zaghouan and 23%, N = 30 in Tataouine) indicated never having attended a training session. This is likely an outcome of the purposive sampling for the study, since we prioritized selecting women respondents who had participated in rangeland development projects. Some of the training sessions women had attended were in skills such as childcare and household water and waste management that are deemed gender appropriate and culturally relevant, which may also explain why more women than men indicated that they had attended training sessions.

Men indicated attending trainings related to feeding and rearing of cows and small ruminants, bee keeping, shearing sheep wool with machines, forming and running SMSAs (Mutual Agricultural Services Companies) and GDAs (Agricultural Development Groups), dealing with water scarcity, organic farming, and dairy and poultry production. Women received some of the same training as men but some sessions – typically for skills such as cheesemaking and other food processing techniques, which were traditionally deemed “women’s work” – were not available to men. One woman who attended a training about forming and managing farmers’ cooperatives explained that a group of women who attended the session formed their own SMSA cooperative: “The cooperative trainings were a useful experience. The location was close to our house, so we could spend about two hours daily for a month while managing our workloads at home. We learned a lot about communication techniques, food processing and storage methods, as well as about forming and managing a cooperative. We gained confidence as a result of the training and started our own SMSA cooperative.”

Adoption of agricultural innovations in the past five years

We asked respondents to identify the most useful innovations that had entered their communities in the past five years. We defined innovations as Phills et al. (Citation2008) do: as “a product, production process, technology, a principle, an idea, a piece of legislation, a social movement, intervention, or some combination of them.” Both women and men respondents listed machinery of various kinds, the practice of leaving rangelands fallow in order to sustain and regenerate them, new goat and sheep breeds, organic farming, vaccination of livestock, distillation of medicinal and aromatic plant oils, the introduction to the rangelands of forage crops, concentrated livestock feed, and the establishment of cooperatives as the most useful innovations to have entered their communities in the past five years. Only men respondents identified irrigation technologies, soil analysis, improved cow breeds, fertilizers, and hydroponics. This may have been a consequence, as noted earlier, of the exclusion of women from training about irrigation technologies as well as men’s greater familiarity with and connections to state-run organizations such as soil analysis centres. Women identified agricultural extension training itself as a useful innovation alongside technologies such as milking machines and olive harvesting machines that enabled them to better fulfill traditional gender roles and responsibilities.

Both women and men respondents justified their rationale for identifying these innovations as “most useful” based on improved production, increased income, and reduced workloads. Men respondents also valued some of these innovations (organic farming, hydroponics, distillation of essential oils, for example) for their ability to create new livelihood opportunities.

More than three quarters of all respondents (82.5%, N = 160, total number of interviews with men and women in the three regions) reported adopting at least one of the innovations that had entered the three communities in the past five years and been deemed “most useful” in our study. Men and women were evenly distributed among the other 17.5%, (N = 160, total number of interviews with men and women in the three regions) of respondents who did not adopt any of the innovations that had been introduced to their communities in the past five years. Most of the innovations that had been adopted centered around machinery (sheep shearing machines, for example). New goat breeds and leaving rangelands fallow were other innovations adopted widely within the three communities we conducted fieldwork in. Using crushed date kernels as feed for livestock and camel breeding were innovations identified exclusively in Tataouine. There were no marked gender differences in innovations adopted or perceived as useful, except that men almost exclusively reported adopting irrigation technologies while women almost exclusively reported adopting mechanized olive harvesting. Also, only women perceived extension programmes and training as useful innovations.

Conclusion

Findings from our study revealed that both men and women are negatively affected by rising temperatures, reduced precipitation, soil erosion and other manifestations of climate change, but they bear the costs and effects of climate change in different ways, often based on socially ascribed gender roles and responsibilities. Men appear to bear more of the financial stress of new costs incurred by responding to the effects of climate change, such as hiring labour to plant trees and purchasing feed from the market. Women, on the other hand, undertake more of the manual labour and drudgery associated with responding to climate change via activities such as collecting forage, feeding, bathing and cleaning up after livestock.

We found that rangeland farmers, irrespective of gender, do not have adequate access to agricultural extension services, credit services and banking institutions, and training to support income generation and livelihood diversification. Although all farmers have been negatively affected by the effects of climate change, women often experience additional challenges due to gender norms and cultural practices. For example, our findings suggest that since women rarely own land, they face more challenges than men do in accessing loans and credit due to their inability to offer individual land titles as collateral. Women also have weaker access than men to extension services and training in skills deemed masculine, such as irrigation and other drought-mitigation strategies. Our findings established that rural women in Tunisia are more actively involved in grazing livestock, and more broadly in livestock rearing and agricultural production, than is assumed in practitioner and policy circles. Women’s growing involvement in livestock rearing and agricultural production must be supported with commensurate social and economic policy interventions. Providing both women and men farmers with appropriate supports to optimize rangeland cultivation and productivity is particularly urgent and important in the context of resource degradation accelerated by climate change.

In their study about women’s participation in farming in rural China, de Brauw et al. (Citation2008) identify two types of feminization of agriculture: labour feminization and managerial feminization. Labour feminization refers to women taking on an increased amount of farm work, often to compensate for the outmigration of men in the household or to men’s increased participation in non-farming economic activities. Managerial feminization refers to women playing a more prominent and visible role in agricultural decision-making alongside gaining greater access to financial and social resources to optimize agricultural productivity. Based on the findings from their study, de Brauw et al. (Citation2008) arrive at the conclusion that rural China was experiencing more labour feminization than managerial feminization. In other words, women were contributing increasing amounts of labour to agriculture without experiencing a commensurate increase in access to resources or authority to make decisions about farming. Abdelali-Martini and Dey de Pryck (Citation2015) arrive at a similar conclusion about women’s growing participation in farming in northwestern Syria. The studies in China and Syria observed women’s participation in crop production. Our findings about women’s contribution to livestock rearing and rangeland cultivation in Tunisia suggest that in addition to contributing increasing amounts of labour to livestock rearing, women are also participating to a limited extent in decision-making about livestock such as sheep and goats and rangeland management through forums such as cooperatives. Optimizing women’s ability to contribute their insights and knowledge about rangeland management and to voice their priorities and needs should be a priority for government agencies, NGOs and international agricultural and development organizations interested in the sustainable management and development of rangelands.

Our findings revealed that in recent years rural households in Tunisia were rearing smaller numbers of livestock than they had in the past. Farmers attributed the decrease in herd size to higher mortality of livestock from heat and dehydration and reduced availability of grazing area, shade, fodder, and water. Fodder production is important for rural populations that are dependent on rangelands for farming and livestock rearing because it allows farmers to mitigate the risks of food shortages for humans by maintaining the health and productivity of livestock (Ayantunde et al., Citation2017). Thus, while preventing further degradation of rangelands is vital for enabling farmers to continue food and forage production, our findings suggest that creating access to fodder markets and providing subsidies to enable farmers to purchase fodder are also important as complementary measures to ensure that livestock have fodder supplies and that rangelands are occasionally allowed to remain fallow to regenerate.

Because women are known to be more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, they also benefit more from access to risk mitigation strategies and tools (Bageant and Barrett, Citation2017; Chanamuto & Hall, Citation2015). Our findings from rural Tunisia suggest that women are often unable to access innovations which may mitigate the effects of climate change at par with men. Skills and training related to drought and irrigation, for example, are targeted almost exclusively to men. It is crucial that women gain access to drought management and adaptation training at par with men. Alongside increasing women’s access to such training, it is important to create more visibility and social acceptance for women in roles such as irrigation, grazing and marketing that are deemed masculine. This will enable more women to participate in rangeland cultivation and livestock rearing on a more equal footing with men and to voice their concerns and priorities in policy dialogues.

More generally, we found that most of the training about drought management focused on supplementary and alternative irrigation techniques and practices. Other complementary drought mitigation and management strategies such as the introduction of cacti, including as livestock feed, and other drought tolerant crops and animal breeds are not presently being explored by the agricultural extension and training programmes in Tunisia. These are worth exploring in the future.

Just as women expressed interest in learning skills that were traditionally only offered to men, we found that many men are interested in learning skills such as cheesemaking that were traditionally only offered to women. Since livelihood diversification and rangeland protection are shared priorities for rural Tunisians, irrespective of gender, it is also important for men to have opportunities to pursue livelihood opportunities that were traditionally deemed “women’s work” without experiencing social stigma or censure. The recommendations we make in this paper are particularly timely given the reforms currently being made to the pastoral code in Tunisia (Werner et al., Citation2018) to address the severe economic, social, environmental, and cultural costs of rangeland degradation across the country.

Acknowledgements

Funding provided by CGIAR Research Program Livestock and the CGIAR Research Initiative on Livestock Climate and System Resilience (LCSR) (including all the donors and organizations which globally support the CGIAR system) (http://www.cgiar.org/about-us/our-funders/) has made this study possible. The authors are grateful for the participants’ generosity and time, as well as all the members of the local collection team and the data analysis team.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dina Najjar

Dina Najjar is a senior gender research scientist at the Sustainable Intensification and Resilient Production Systems Program (SIRPSP), the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), Rabat, Morocco. A socio-cultural anthropologist by training, she focuses on the link between gender equality and policies; agricultural technologies and delivery systems; rural employment and migration; adaption to climate change and productive assets, including access to land and ownership, in the Middle East and North Africa. Her geographical expertise includes Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Sudan. She has also conducted research in Uzbekistan, Kenya, Ethiopia and India.

Bipasha Baruah

Bipasha Baruah is a professor and Canada Research Chair in Global Women's Issues at Western University. Professor Baruah earned a PhD in environmental studies from York University, Toronto, in 2005. She specializes in interdisciplinary research at the intersections of gender, economy, environment and development. Most of her current research aims to understand how to ensure that a global low-carbon economy will be more gender equitable and socially just than its fossil-fuel-based predecessor. She is the author of a book and more than 100 peer-reviewed articles, book chapters and other works. Professor Baruah serves frequently as an expert reviewer and advisor to Canadian and intergovernmental environmental protection and international development organizations. The Royal Society of Canada named her to The College of New Scholars, Artists and Scientists in 2015.

References

- Abdelali-Martini, M., & Dey de Pryck, J. (2015). Does the feminisation of agricultural labour empower women? Insights from female labour contractors and workers in northwest Syria. Journal of International Development, 27(7), 898–916. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3007

- Abdelali-Martini, M., & Hamza, R. (2014). How do migration remittances affect rural livelihoods in drylands? Journal of International Development, 26(4), 454–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.2896

- Acosta, M., van Wessel, M., Van Bommel, S., Ampaire, E. L., Twyman, J., Jassogne, L., & Feindt, P. H. (2019). What does it mean to make a ‘joint’decision? Unpacking intra-household decision making in agriculture: Implications for policy and practice. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(6), 1210–1226.

- Afifi, T., Milan, A., Etzold, B., Schraven, B., Rademacher-Schulz, C., Sakdapolrak, P., … Warner, K. (2016). Human mobility in response to rainfall variability: Opportunities for migration as a successful adaptation strategy in eight case studies. Migration and Development, 5(2), 254–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2015.1022974

- Alexander, P., Nabalamba, A., & Mubila, M. (2011). The link between climate change, gender and development in Africa. The African Statistical Journal, 12, 119–140.

- Archambault, C. S. (2010). Women left behind? Migration, spousal separation, and the autonomy of rural women in Ugweno, Tanzania. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 35(4), 919–942. https://doi.org/10.1086/651042

- Archambault, C. S. (2016). Re-creating the commons and re-configuring maasai women’s roles on therangelands in the face of fragmentation. International Journal of the Commons, 10(2), 728–746. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.685

- Ayantunde, A., Yameogo, V., Traore, R., Kansaye, O., Kpoda, C., Saley, M., Descheemaeker, L., & Barron, J. (2017). Improving livestock fodder production through greater inclusion of women and youth: Results from the “realizing the full biomass potential of mixed crop-livestock systems in rapidly changing Sahelian agro-ecological landscapes” project. Water, Land and Ecosystems Briefing Series, 10, n.p.

- Bageant, E. R., & Barrett, C. B. (2017). Are there gender differences in demand for index-based livestock insurance? The Journal of Development Studies, 53(6), 932–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1214717

- Briggs, J., Sharp, J., Hamed, N., & Yacub, H. (2003). Changing women’s roles, changing environmental knowledges: Evidence from upper Egypt. The Geographical Journal, 169(4), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0016-7398.2003.00095.x

- Calvosa, C., Chuluunbaatar, D., & Fara, K. (n.d.). Livestock and Climate Change. IFAD Thematic Paper, 1-19.

- Carr, E. R., & Thompson, M. C. (2014). Gender and climate change adaptation in agrarian settings: Current thinking, new directions, and research frontiers. Geography Compass, 8(3), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12121

- Chanamuto, N. J. C., & Hall, J. G. (2015). Gender equality, resilience to climate change, and the design of livestock projects for rural livelihoods. Gender & Development, 23(3), 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2015.1096041

- Croitoru, L., & Daly-Hassen, H. (2015). Vers une gestion durable des écosystèmes forestiers et pastoraux en Tunisie: Analyse des bénéfices et des coûts de la dégradation des forêts et parcours. Direction Générale des Forêts/MARHP, Banque Mondiale.

- Curry, J., Huss-Ashmore, R., Perry, B., & Mukhebi, A. (1996). A framework for the analysis of gender, intra-household dynamics, and livestock disease control with examples from Uasin Gishu District, Kenya. Human Ecology, 24(2), 161–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02169125

- Daley, E., Kisambu, N., & Flintan, F. (2017). RANGELANDS: Securing pastoral women’s land rights in Tanzania. Rangelands Research Report. International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

- Debela, B. L. (2017). Factors affecting differences in livestock asset ownership between male and female-headed households in Northern Ethiopia. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(2), 328–347. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2016.9

- de Brauw, A., Li, Q., Liu, C., Rozelle, S., & Zhang, L. (2008). Feminization of agriculture in China? Myths surrounding women’s participation in farming. The China Quarterly, 194(194), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741008000404

- de Haas, H., & van Rooij, A. (2010). Migration as emancipation? The impact of internal and international migration on the position of women left behind in rural Morocco. Oxford Development Studies, 38(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600810903551603

- Doss, C., Meinzen-Dick, R., & Bomuhangi, A. (2014). Who owns the land? Perspectives from rural Ugandans and implications for large-scale land acquisitions. Feminist Economics, 20(1), 76–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.855320

- Dumas, S. E., Maranga, A., Mbullo, P., Collins, S., Wekesa, P., Onono, M., & Young, S. L. (2018). “Men Are in front at eating time, but Not when It comes to rearing the chicken”: Unpacking the gendered benefits and costs of livestock ownership in Kenya. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 39(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572117737428

- Fetoui, M., Frija, A., Dhehibi, B., Sghaier, M., & Sghaier, M. (2021). Prospects for stakeholder cooperation in effective implementation of enhanced rangeland restoration techniques in southern Tunisia. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 74, 9–20.

- Fisher, M. G., Warner, R. L., & Masters, W. M. (2000). Gender and agricultural change: Crop-livestock integration in Senegal. Society & Natural Resources, 13(3), 203–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/089419200279063

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2013). Tackling climate change through livestock: A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- Fraser, E. D. G., Dougill, A. J., Hubacek, K., Quinn, C. H., Sendzimir, J., & Termansen, M. (2011). Assessing vulnerability to climate change in dryland livelihood systems: Conceptual challenges and interdisciplinary solutions. Ecology and Society, 16(3), n.p.

- Galie, A., Teufel, N., Korir, L., Baltenweck, I., Webb Girard, A., Dominguez-Salas, P., & Yount, K. M. (2018). The women’s empowerment in livestock index. Social Indicators Research, 142(2), 799–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1934-z

- Gartaula, H. N., Niehof, A., & Visser, L. (2010). Feminisation of agriculture as an effect of male out-migration: Unexpected outcomes from Jhapa District, Eastern Nepal. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 5(2), 407–412.

- Haddad, N., Duwayri, M., Oweis, T, Bishaw, Z., Rischkowsky, B., Hassan, A. A., & Grando, S. (2011). The potential of small-scale rainfed agriculture to strengthen food security in Arab countries. Food Security, 3, 163–173.

- Haddad, N., & Shideed, K. (2013). Mainstreaming adaptation to climate change into the development agenda. In M. V. K. Sivakumar, R. Lal, R. Selvaraju, & R. Hamdan (Eds.), Climate change and food security in West Asia and North Africa (pp. 301–315). Springer.

- IFAD. (2012). PRODESUD Project Completion Report Validation. Independent Office of Evalution: International Fund for Agricultural Development.

- Jacobs, K., & Kes, A. (2015). The ambiguity of joint asset ownership: Cautionary tales from Uganda and South Africa. Feminist Economics, 21(3), 23–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2014.926559

- Jaouad, M. (2009). Economic importance, potentials and performance of Tunisian meat sector: Red meat supply response and its determinants. New Medit, N 2, 31–36. https://newmedit.iamb.it/share/img_new_medit_articoli/254_31jaouad.pdf.

- Kristensen, S., & Birch-Thomsen, T. (2013). Should I stay or should I go? Rural youth employment in Uganda and Zambia. International Development Planning Review, 35(2), 175–201.

- Läderach, P., et al. (2022). Strengthening Climate Security in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Position Paper No. 2022/3. CGIAR FOCUS Climate Security.

- Leavy, P. (2022). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. Guilford Publications.

- Najjar, D., Baruah, B., & Al-Jawhari, N. (2019b). Decision-making power of women in livestock and dairy production in Jordan. International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA).

- Najjar, D., Baruah, B., Aw-Hassan, A., Bentaibi, A., & Kassie, G. T. (2018b). Women, work, and wage equity in agricultural labour in Saiss, Morocco. Development in Practice, 28(4), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1449813

- Najjar, D., Baruah, B., & El Garhi, A. (2019a). Women, irrigation and social norms in Egypt: “The more things change, the more they stay the same?”” Water Policy, 21.

- Najjar, D., Baruah, B., & El Garhi, A. (2020). Gender and asset ownership in the old and new lands of Egypt. Feminist Economics, 26(3), 119–143.

- Najjar, D., Baruah, B., & Garhi, A. (2018a). Women and land ownership in Egypt: Continuities, contradictions, and disruptions, Chapter 3. In Y. Emerich, & L. Saint-Pierre (Eds.), Access to land and social issues: Precarity, territoriality, identity (pp. 59–86). McGill-Queen’s University Press (MQUP).

- Njuki, J., & Sanginga, P. C. (2013). Gender and livestock: Key issues and opportunities. In Women, livestock ownership and markets: Bridging the gender gap in eastern and Southern Africa (pp. 1–8). Routledge.

- Open GeoData Tunisie. (2018). Goat Count in Southern Provinces in Tunisia. https://opengeodata-ageos-tunisie.hub.arcgis.com/datasets/evolution-du-cheptel-des-caprins-1993-2018/explore?filters=eyJnb3V2ZXJub3JhdCI6WyJUYXRhb3VpbmUiLCJNZWRuaW5lIiwiR2FiZXMiLCJLZWJlbGkiXX0%3D&location=33.786767%2C9.565336%2C6.87&showTable=true.

- Pattnaik, I., Lahiri-Dutt, K., Lockie, S., & Pritchard, B. (2018). The feminization of agriculture or the feminization of agrarian distress? Tracking the trajectory of women in agriculture in India. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 23(1), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2017.1394569

- Pedrick, C. (2012). Strategies for combating climate change in drylands agriculture: Synthesis of dialogues and evidence presented at the International Conference on Food Security in Dry Lands, Doha, Qatar, November, 2012. The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) and CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), Aleppo, Syria and Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Phills, J. A., Deiglmeier, K., & Miller, D. T. (2008). Rediscovering social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 6(4), 34–43.

- Radel, C., Schmook, B., Mcevoy, J., Mendez, C., & Petrzelka, P. (2012). Labour migration and gendered agricultural relations: The feminization of agriculture in the ejidal sector of Calakmul. Mexico. Journal of Agrarian Change, 12(1), 98–119.

- Schilling, J., Hertig, E., Tramblay, Y., & Scheffran, J. (2020). Climate change vulnerability, water resources and social implications in North Africa. Regional Environmental Change, 20(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01597-7

- Sowers, J., Vengosh, A., & Weinthal, E. (2011). Climate change, water resources, and the politics of adaptation in the Middle East and North Africa. Climatic Change, 104(3–4), 599–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-010-9835-4

- Statista. (2002). Number of heads of livestock in Tunisia from 2014 to 2018, by type. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1185948/number-of-livestock-in-tunisia-by-type/.

- Strategies for Combating Climate Change in Drylands Agriculture. (2012). Report prepared for conference of the parties united nations framework convention on climate change (COP18). CGIAR, CCAFS, ICARDA, Qatar National Food Security Program.

- Thomas-Slayter, B. (1994). Land, livestock, and livelihoods: Changing dynamics of gender, caste, and ethnicity in a Nepalese village. Human Ecology, 22(4), 467–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02169389

- Turner, M., & Williams, T. (2002). Livestock market dynamics and local vulnerabilities in the Sahel. World Development, 30(4), 683–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00133-4

- Waterbury, J. (2013). The political economy of climate change in the Arab Region. Arab Human Development Report Research Paper Series. United Nations Development Programme.

- Werner, J., et al. (2018). A new pastoral code for Tunisia: Reversing degradation across the country’s critical rangelands. ICARDA/ Direction Générale des Forêts (DGF), Ministère de l’Agriculture et des Ressources Hydrauliques et de la Pêche.

- World Bank (WB). (2015). http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/762871468113330972/pdf/PID-Print-P151030-10-03-2016-1475515550080.pdf.

- Ye, J., Wu, H., Rao, J., Ding, B., & Zhang, K. (2016). Left-behind women: Gender exclusion and inequality in rural-urban migration in China†. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 43(4), 910–941. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1157584