ABSTRACT

With climate change, many cultural landscapes will be lost or permanently altered. One approach to managing this is through international designation, through UNESCO, and the focus that it provides. National designations such as National Park status also offer a set of strategies for managing and adapting. This paper explores landscape designations in Japan and the UK focusing on the UNESCO World Heritage List. It is suggested that the UK’s dualistic governmental structures for landscapes prioritise some attributes over others. This is examined through the recent inscription of the Lake District as a World Heritage Property and counterpointed through looking at the recent Landscape Review also known as the Glover Report. A case study on a Japanese approach to landscape designation is explored to suggest alternative approaches. Both country’s relationship with international designation is discussed. Methodologies and theoretical approaches are examined with the conclusion that landscape change and loss are dealt with in Japan differently and arguably more effectively.

Introduction

This paper explores different approaches to landscapes and how they are designated as cultural heritage in the UK and Japan through the lens of the UNESCO World Heritage List. It is suggested that the UK and Japan have two distinct philosophical approaches to cultural heritage and that local perceptions of landscape, defined culturally and politically, result in very different concepts of heritage. In the UK approaches to cultural landscapes are fragmented through an institutionally and governmentally led dualistic view of places as either culture or nature. Arguably the distinction between what is cultural and what is natural is not defined in the same way in Japan. Why is this important? With climate change, we are looking at the loss and significant alteration of many landscapes. UNESCO designation is one strategy for trying to deal with this and ascribes a yardstick of value that can in some circumstances be compelling for galvanising action by local people and national governments. The Japanese Government Agencies take the UNESCO approach to value seriously and have spent much time, effort and resource on influencing international approaches to heritage. The UK Government, or perhaps more accurately the legislative framework for England, is now clearly less interested in an international approach to heritage than it was. The assertion here is that Japan is culturally much more able to deal with the concept of loss than is the UK, which seems to be poorly prepared for what is now inevitable. Both nations have at various moments in the history of UNESCO played a pivotal role in its formulation of approaches. Both are densely populated island nations with disproportionally large impacts on their own and other’s environments. Both are also struggling with re-defining their national identities and their relationships with their nearest neighbours. UNESCO provides a flawed but useful framework for agreeing internationally that heritage needs to be cared for. International standards are more than ever keenly important with the changes that climate change will bring.

Inscription of a place on the UNESCO World Heritage List is a long, arduous and expensive process. Why would anyone wish to set out on this path? If a place can pass the test of being viewed as having ‘universal value’, is it a path that makes sense in terms of change management? In both the UK and Japan, obtaining a UNESCO World Heritage List inscription is a bottom-up process, starting locally. World Heritage inscription remains a process that in many cases takes decades to complete. In the meantime, situations change and government policy over a decade shifts both practically and ideologically. In Japan and the UK, it could be argued, there are adequate protections for landscapes, cultural and natural heritage already in place without involving UNESCO.

For the UK, Brexit may be altering long-standing sureties about the treatment of cultural heritage. The current White Paper: Planning for the Future sets out a radical change to the planning system, but only offers a minor discussion of the consequences for either cultural heritage or landscapes, with cursory mentions of places on the World Heritage List and National Parks.Footnote1 Japan has a significant heritage protection bureaucracy in place but is firmly wedded to massive urban development and with it the concept of preservation through record. In Japan, the difference between tangible (built) and intangible (non-built) heritage is blurred, whereas in the UK there is a much more pronounced dividing line. There are similarities, however, there are also major differences in approach that reveal different conceptual frameworks. I will argue this is particularly true in the case of landscapes where there are long cultural dissimilarities, particularly in terms of splitting heritage into natural and cultural. It remains the case that the motivation for the inscription of landscapes on the World Heritage List in both instances seems to be different. Differences are also ideological. Here I reflect that approaches to World Heritage in the two countries suggest different attitudes that apply to all heritage and that despite some similarities in approach the two countries have different views of what heritage is and why it is important. With likely transformational change to a vast range of heritage through the effects of climate change on the horizon, there is a need to consider strategies for loss.Footnote2 Given that the Japanese approach to cultural heritage potentially incorporates loss, the proposition here is that researchers and practitioners in the UK, and elsewhere, should look more carefully at why this is the case in Japan, and how the Japanese approach can inform local thinking elsewhere.

As an archaeologist, my interests gravitate to the longue durée as reflected in landscapes. Through training and subsequent experiences as a professional and academic, I have a set of perspectives and biases. For much of my career, I have been interested in the development of landscapes, urban and rural, and the social forces behind them. My view is very much predicated on the idea that people shape and experience landscapes in an embodied way, from the basis of materiality.Footnote3 Working in local government in the East of England I latterly became responsible for aspects of natural environment management, trying to ‘conserve’ both natural and cultural heritage through the planning system. The natural heritage colleagues that I worked with in this area had different training, perspectives and biases to that of mine. Their concerns were perhaps more about the immediate and longer-term future, focusing on a crisis in the present – falling biodiversity. I agreed with them wholeheartedly, however, I felt though that it is difficult to influence the development of a landscape, or environment, unless you have a thorough understanding and experience of its history – and even then, there are too many variables to be confident that outcomes can be managed. There has been a tendency amongst ecologists to look at change as deviating from an idealised world that existed at an unspecified moment in the past, usually through the arrival of a new species or shifts of habitat for existing ones.Footnote4 The same is true of some practitioners of archaeological conservation, with the act of preserving a largely unknown archaeological resource seen as preferable to the act of ‘destruction’ through excavation and the making of a ‘record’. Holtorf makes the point that less preservation can mean more memory.Footnote5

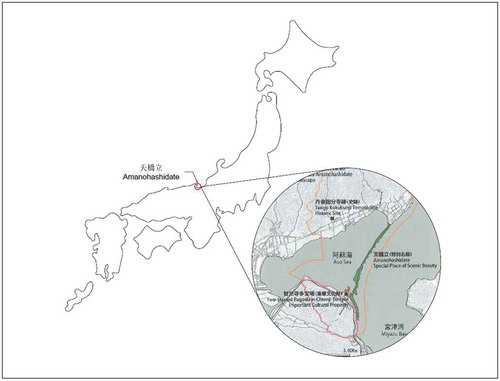

In February 2019 I travelled to Japan in part to attend a conference about the potential inscription onto the World Heritage List of a landscape with a beautiful sand bar separating two bays, Miyazu and Ine, on the Sea of Japan; this focal point is called Ama-no-hashidate. Here much of the cultural heritage is focused on this geomorphological feature (see ). The relationship between the sandbar and the surrounding cultural heritage, and with the works of art that portray Ama-no-hashidate create a continuum of meaning. It is a site of worship and reverence and of contemplation. It is also a classic landscape in that it privileges the view of a special place. For me it helped crystallise some disparate ideas. The landscape is sacred in both Shintō and Buddhist belief. There are many examples in the anthropological literature about the religious and ritual nature of people’s relationship with their environment going right back to the beginnings of the subject, with terms like animism being used to describe human relationships with the rest of the environment.Footnote6 Indeed, there is a huge literature also on the prehistoric evidence for human/environment relations.Footnote7 In accepting that the concept of heritage discourse is a specific historical and cultural context of a European and by extension global milieu how does Japan, or indeed any other non-European culture fit within this situation?Footnote8 Holtorf and Fairclough have suggested that a ‘New Heritage’ has emerged that is more focused on the interactions between people and their world and less on the objects of heritage.Footnote9 Is this really so new? Not in Japan.

The Japanese and the UK systems of landscape management are, on the face of it, similar, but their cultural heritage approach to landscape is essentially different. A recent study in Japan that questioned university students with an interest in leisure pursuits in the outdoors found that hardly any could name a national park, but 70% of the participants were interested in visiting a World Heritage site.Footnote10 Though there is no comparative data in the UK it is reasonable to assume that the reverse would be true, with the exception of locations where the two designations have been applied to the same place, such as the Lake District. This may help to explain the difference in enthusiasm in the two countries for proposing new sites for listing. Japan is now a leading voice in UNESCO with much formal and informal influence.Footnote11 The UK’s enthusiasm for UNESCO has waned dramatically during the last few decades resulting in it following the US out of UNESCO on two occasions, perhaps reflecting the US’s, and by extension, the UK’s, distrust of international agencies more generally and of the concept of world government.Footnote12 On the latest occasion of US withdrawal, when President Donald Trump affirmed in 2017 that he would be ending its membership, the motivation was particularly egregious and demonstrated that the US potentially poses a major danger to UNESCO’s mission.Footnote13 The UK is also now in a parlous state with regard to international norms around conservation, with Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City World Heritage Site’s presence on the ‘at danger list’, largely due to competing cultural and economic agendas within national and local government that have been left unresolved for decades.

World Heritage and Cultural Landscapes

UNESCO defines heritage as ‘our legacy from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to future generations. Our cultural and natural heritage are both irreplaceable sources of life and inspiration’.Footnote14 Since 1992, UNESCO has recognised and promoted the term cultural landscape as a key form of heritage. During its 16th session, the World Heritage Committee adopted guidelines for cultural landscapes to be included in the List, expressly to widen the concept of World Heritage and provide more room for the nomination of heritage with different aspects.Footnote15 Prior to this, a mechanism was lacking for recognising that many sites display a combination of cultural and natural features, and that it is through the interplay of these that their ‘outstanding universal value’ lies.Footnote16

The inclusion of the concept of landscape in the lexicon of definitions available to the World Heritage Committee came about in part from the pressure to be more inclusive, but arguably the concept is in and of itself Eurocentric, despite its intended outcomes. Perceptions about the term are meshed with concepts of historical garden style in a British context, particularly the informal landscape style that was fashionable in the UK from the mid-18th century to the early 19th century. The direct intellectual legacy for the inclusion of the idea of landscape in this way dates to the British approach to historical geography exemplified in the mid-20th century by scholars such as W.G. Hoskins, C. Taylor and H.C. Darby that involved utilising historical documents to chart landscape change.Footnote17 Akagawa and Sirisrisak argue that the dualism inherent in separating out the cultural and the natural stems from the work of C.O. Sauer in the 1920s, who defined cultural landscape as being: ‘fashioned from a natural landscape by a cultural group. Culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium, the cultural landscape is the result. Under the influence of a given culture, itself changing through time, the landscape undergoes development, passing through phases and probably reaching ultimately the end of its cycle of development’.Footnote18 Whether Sauer was as influential as is being suggested is debatable, but it is certainly true that the division between the terms culture and nature became entrenched in many of the social sciences during the early to mid-20th century, coincident with the height of modernity. The separation of cultural and natural landscapes has latterly become a concern within UNESCO, where it is stated in the Report of the Expert Meeting on European Cultural Landscapes of Outstanding Universal Value that, ‘Nature conservation in Europe does not often integrate the protection and development of cultural landscapes’.Footnote19

Following on from Akagawa’s and Sirisrisk’s 2008 paper in which they noted a significant geographical imbalance in inscribing cultural landscapes onto the List – of 53 such sites at the time, 33 were located in either Europe or North America (66%), and only 10 (19%) in Asia and the PacificFootnote20 – there are now 119 cultural landscapes on the List, out of a total of 1121 properties. Of these, 54 (45%) are in Europe and 9 (8%) in North America, giving a combined total of (53%), with 28 (24%) in Asia and 7 (6%) in the Pacific, accounting for 35 (29%) of the total. A further 15 (13%) are in Africa and the smallest number 6 (5%) are located in South America. The distribution is still very biased but is moving in the right direction for Asia and the Pacific, though Africa and South America are both hugely underrepresented. Notably, there are now two Japanese sites inscribed under the cultural landscape’s category, Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range and Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine and its Cultural Landscape. The UK has inscribed five landscapes, the latest being the Lake District, the same number as China and Germany, but fewer than France and Italy, both with eight. Clearly, the concept of cultural landscapes is a popular one with many of the UNESCO signatories. This popularity does not seem to be waning as 2019 saw the inscription of eleven new landscapes, the second largest number in a year, following on from a bumper year in 2004 with 12 inscriptions.

Both Japan and the UK have incorporated the protection of landscapes into their conservation systems in a variety of forms, perhaps most successfully for the UK in terms of national parks, a concept invented in the United States in 1872 to protect Yellowstone, and essentially deriving from a romantic view of the landscape as wilderness. It has become a hugely popular idea that has been adopted globally.Footnote21 In the US, the concept was predominantly about the protection of the natural – First Nation cultural concerns were never central to the premise. Japan’s first national parks were created in 1931, but legal protection came in 1957 with National, Quasi-Natural and Prefectural Natural Parks designated as ‘natural areas of scenic beauty’.Footnote22 From 2004 Japan amended its Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties to include the category of cultural landscape and to widen the definition for landscape beyond ‘Places of Scenic Beauty’.Footnote23 In the UK, it was not until 1945 that the concept of protecting landscapes arrived, resulting in a White Paper from a post-war Labour Party under pressure from a diverse group of conservationists and outdoor leisure enthusiasts. This followed from the efforts of rambling groups, now epitomised by the mass trespass at Kinder Scout in 1932, that led eventually to the Hobhouse review.Footnote24 By 1949 the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act came into force. The key concern was access to the countryside for populations that were increasingly urban. In 2000, the European Landscape Convention was agreed, with the UK as a signatory. This has influenced how landscapes are managed in the UK, with an emphasis on landscape assessment, particularly shaped by the 2002 Countryside Agency Landscape Character Assessment: Guidance for England and Scotland (although the idea of landscape assessment has its antecedents in the work of the Countryside Commission in the 1980s and 90s).Footnote25 More recently Natural England, which replaced the short-lived Countryside Agency in 2006, continues to provide guidance on landscape character assessment and is clear on the cultural importance of landscapes, stating, for instance, that ‘Our landscapes vary because of, amongst other variables, their underlying geology, soils, topography, land cover, hydrology, historic and cultural developments, and climatic considerations.Footnote26 There is, however, a parallel system for Historic Landscape Characterisation funding and management responsibility for which lies with a different department: Historic England. Historic Landscape Characterisation was developed in Britain in 1993 by English Heritage, the then national heritage body for England, along with county councils (higher tier local authorities) to provide a complementary view to Landscape Character Assessment from an archaeological and historical perspective. Both approaches have been influential across Europe as methods for understanding and working within the concept of landscape, and their use is promoted by the European Landscape Convention which uses the concept of ‘character’ (meaning the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors) in its definition of landscape.Footnote27 Arguably Historic Landscape Characterisation is a more rigorous approach to understanding landscapes than the more visually focused Landscape Character Assessment, and in terms of usefulness as a planning tool, the charting of trajectories perhaps offers a more sustainable approach to change than the blunter instruments of ‘green infrastructure’, rewilding or ‘net gain’.Footnote28 The key point here though is not so much that one method is superior to the other, or indeed that they are complementary in practice, but rather that there are, and have been, throughout the last 30 to 40 years of landscape planning in the UK, two separate methodologies for understanding landscapes and making planning decision about them, promoted and run by two separate quangos – English Heritage and Natural England – who are related to two different government ministries, Department for Culture Media and Sport (DCMS, latterly), and the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). With the UK leaving the EU the kinds of protection afforded to cultural landscapes is a critical issue. For instance, the approach to nationally designated landscapes, National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, is a lens on thinking about landscape and environment more generally. Recent statements from the UK Government and its advisors have rightly focused on biodiversity and the quality of the natural environment.Footnote29 Clearly this is a key priority. However, there is almost no reference in these documents to the concept that designated landscapes and landscapes more generally in the UK are not only wildlife habitats, but also have long cultural histories.

Japan too has separate agencies that are responsible for both natural and cultural landscapes, and as mentioned above, it was an early adopter of the idea of national parks. However, the concept of nature arguably, such as used in geography, was imported into Japan through the influence of European geography; in ancient Japan, people viewed natural landscapes as created by and inhabited by Kami and the will of Kami controlled the cultural domain.Footnote30 With the Meiji restoration (1868) and the national programme to modernise Japan, an occidental model of nature/culture dualism was partially adopted. This mode of thinking has dominated many academic and public spheres of discourse, but not that of cultural heritage, where an older perspective has survived. Arguably the strong interest in the country’s cultural heritage is a way of continuing to create a national identity and is therefore linked to nationalism. Nihonjinron is a term describing the post-war discourse regarding the nature of Japaneseness and has been interpreted as a kind of cultural nationalism.Footnote31 The relationship between globalisation, cultural identity and the increasing ubiquity of the English language in international discourse has been discussed by Yoshino noting that there is not only enthusiasm for speaking English within Japan, but there is also a current of opinion that worries about the domination of English. There is a kind of secondary imperialism implicit in its widespread adoption that intimates through speaking English the Japanese adopt ‘Anglo-Saxon’ views of the world and internalise them.Footnote32 Cultural heritage provides a foil to the potential of cultural domination from outside of Japan.

Structural Reinforcement of the Culture/nature Dualism

The UK Government’s Landscapes Review seeks to address concerns for the future of designated landscapes in England.Footnote33 I had a small involvement in the Glover Review, as it was known, visiting Julian Glover at DEFRA Headquarters in April 2018 with a small contingent from local government. Glover had been asked by Michael Gove, then Secretary of State for the Environment, to lead the review. Glover is an ex No. 10 Downing Street Special Advisor (SPAd), an author, journalist and Associate Editor of the London Evening Standard. Essentially this was a review of designated landscapes in England, consisting of National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). It was commissioned as a response to the Government’s 25 Year Plan to Improve the EnvironmentFootnote34 and the panel had reviewed some 2500 submissions from organisations and individuals after a general consultation and several public meetings. The emphasis throughout the Landscapes Review was on natural beauty and to a lesser extent biodiversity. What is notable within the document is the lack of reference to culture, cultural heritage, cultural landscapes, historic environment or archaeology, though there is a clear interest in farming regimes and in the potential for Environment Land Management Schemes (ELMS). It seemed to me that the Landscape Review was in sharp contrast to the rationale for the Lake District’s, one of the National Parks being reported on in the Landscape Review, recent inscription on the World Heritage List. The Lake District’s outstanding universal value consisted of its glacial origins shaped by a distinctive agro-pastoralist tradition, the artistic and literary movements inspired by the landscape and the fact that it was a landscape that had been a catalyst for important developments in the national and international systems of landscape protection.Footnote35

Clearly the cultural is very much at the heart of the approach to the heritage of the Lake District, as is the term cultural landscape. Why the stark difference in approach between the two documents, given that they are close to contemporary? The answer, on the surface at least, is because they were undertaken by two different government departments with very different and non-aligned perspectives on landscapes. These differences pose the question regarding who makes decisions in the UK about landscape at a policy level, and more fundamentally, who is tasked with drawing together the spectrum of opinions and expertise and how they go about it. There is a lack of a consistent approach to our most iconic and valued landscapes in the UK, and in particular an apparent almost complete lack of interest in the cultural component of these places displayed not only in the Landscape Review but also by Natural England, under whose remit protection of these landscapes largely fall, and its parent ministry DEFRA. This is particularly strange when we consider the wealth of expertise in the UK focused on cultural landscapes. Why are these two worlds now so separate? In local government, there has also generally been a strong separation between the natural and the cultural, but in recent years this has become financially unsustainable. Examining UK landscape conservation and comparing it with the way that landscapes are viewed and conserved in Japan provides a different lens. Both nations have similar problems to contend with and take different approaches. Both can be critiqued on a number of levels. What had gone wrong with the Landscape Review process?

Ama-no-hashidate

As discussed above, in February 2019 I took part in a conference in Miyazu City exploring the next steps in promoting the Cultural Landscape of Miyazu-Ama-no-hashidate Important Cultural Landscape’s inclusion on the Japanese tentative list for inscription on The World Heritage List. This landscape contains a number of designated Cultural Properties, including: Ama-no-hashidate (itself designated as a Special Place of Scenic Beauty); the Shrine located at the Atsumatsu, the widest part of the sandbar; the Kasamatsu Park where the scene can be viewed at its best; the Two-Storied Pagoda (CE 1501) at Chionji Temple (CE 901–923) designated as an Important Cultural Property; the Tango Kokubunji Temple Site (c. CE 710–794), and the Nariaiji Temple Site (CE 704), both designated as Historic Sites. There are also closely associated objects that have been designated as National property, such as the painting by the artist Sesshu Toyo (CE 1420–1506) in the Kyoto National Museum.

Ama-no-hashidate is a sand bar topped by pine trees on the north coast of Kyoto Prefecture, Sea of Japan, separating Miyazu and Ine bays in what was historically Tango Province (see ). The area is famous for its scenic settings of magnificent mountains and hills set against seascapes. Arguably Ama-no-hashidate epitomises the scenery of the Japanese Sea. An enthusiasm for the scenic has long artistic and aesthetic roots in Japanese culture, with traditions of drawing and painting views associated with the coast dating back to the Heian period (CE 794–1192). Inspiration from sea scenes has influenced concepts of design associated with arts beyond the graphic, including the core concepts behind Japanese gardens and ultimately Zen gardens, which are influenced by the paintings of the Song Dynasty.Footnote36 The earliest reference to Ama-no-hashidate is in the form of an uta-awase poetry contest held by the Emperor Murakami in CE 966. In this discipline the poet creates a work that includes both graphic motifs and written characters to express harmony between the different forms.Footnote37 By the end of the CE 10th century it was being used as a central motif in the gardens of the aristocracy, most prominently that of Onakatomi Sukechika (CE 954–1038). The retirement residence of the Emperor Sutoku (CE 1119–1164) possessed a garden itself called Ama-no-hashidate, with the great sandbar modelled as a central feature.

The focus of the bid is the sandbar as the centrepiece of a cultural landscape. Currently, the site itself and some of the viewing areas, such as Kasamatsu Park, are nationally owned but managed by Kyoto Prefecture. The sandbar is threatened by erosion exacerbated through climate change. The pine trees that grow on the bar require careful maintenance and there is an army of willing volunteers who help to manage other growth and maintain the pines through props and replacing dead or diseased trees. The prefecture possesses a management plan for the continuing maintenance of the sandbar and its flora. The temple of Chionji also has its own conservation management plan. Kyoto Prefecture has the coordinating role and is responsible for developing future management and conservation plans .

The concept of the focused landscape is central to the bid to place the landscape on the Japanese tentative list. The sandbar holds a special significance and has key resonances throughout a range of arts. It is also a sacred place with Shintō and Buddhist religious places surrounding and focused on the sandbar. This reflects the fusion of the two religions, a common theme in Japan’s World Heritage Sites. The Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range was inscribed on the List in 2004. Here the foci are three sacred sites, Yoshino and Omine, Kumano Sanzen and Koya-san, linked by pilgrim routes connecting the ancient capital cities of Nara and Kyoto. With the surrounding forests, mountains and abundant streams, rivers and waterfalls, the sites form a cultural landscape.Footnote38 As with Ama-no-hashidate, there are foci, this time multiple, that in part define the landscape. In the justification for inclusion of the landscape on the List, the role of Shintō as a religion of ‘worshiping nature’ is cited as a factor.Footnote39 The interplay between Shintō and Buddhism is another key factor, as is the influence that the focal sites had on art and architecture. The area is designated as a national park and Prefectural Natural Park, providing protection for plants and animals. Temples and Shrines are maintained by the respective religious organisations and financial support and regulation come from local and central government. Notably, reverence of the landscape is bound up in rituals associated with particular places, such as the stretches of cherry trees at Yoshinoyama and Kimpusen-ji Hondo where they are central to an annual ritual in the spring of offering blossoms to the local deity. Key here is that religion plays a central role in the protection and conservation of the landscape as a whole, though this is overlain by regulation and law. The same is true of another recent Japanese inclusion on the List, the Sacred Island of Okinoshima and Associated Sites in the Munakata Region, where protection of the pristine island is largely achieved through religious reverence.Footnote40 Further than the achievement of preservation and continuing conservation, this spiritual aspect colours the whole approach to these places. Also relevant is that there is one government body responsible for most landscapes, and indeed all heritage in Japan – the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Although there are structural distinctions between the government departments responsible for the cultural and natural designations there does not appear to be a lack of a focused and holistic agenda for the development of landscape designations. As with most coastal locations this place is set to be affected by climate change and the survival of the sandbar is now a geoengineering challenge .

Dualism and Classification

Landscapes and environment are often conflated and are subject to competing agendas. At the same time most landscapes, and the cultural heritage contained within them, are impacted by market forces. To break these issues down further, the archaeological, traditional, historical, environmental, architectural, place-making and economic, to name a selection, can be individually subject to different forces and to diverse ideological positions. Packaging conservation and protection of valuable elements of this spectrum into an overly pressurised and under-resourced system of management and an antagonistic set of legal procedures found, for instance, within the UK planning system often results in winners and losers. Dichotomies between the natural and the cultural add a further level of complexity. This split between the non-human and the human misrepresents the reality that human agency has impacted on all of the environment.Footnote41

Why is a concept of World Heritage important? Given its potentially Eurocentric framework and its roots in colonial processes, it is still key that we define ways of engaging with a range of cultural heritage in terms of a universal measure, but with a focus on the particular. We have seen over the last decade an erosion and fragmentation of systems for protecting and supporting cultural landscapes and cultural heritage. The US withdrawal from UNESCO in 2017 seems to have been for a number of reasons – money, the US Government owed 550,000 USD – and Palestine’s inclusion 7 years earlier in 2011,Footnote42 but the effect was to fragment and reduce the activities UNESCO could carry out. The manner and processes of making World Heritage bids also vary in different locations, ensuring that UNESCO is a confusing and baroque system, even to the insiders involved. In the UK, it could be argued that for many years there has been an economically driven view of the World Heritage List,Footnote43 which furthered a fiscally driven review of its approach to the List in 2006–7. This almost singularly economic and fiscal viewpoint is clear through DCMSs decision to commission Price Waterhouse Cooper to investigate the costs and benefits of World Heritage Site status in the UK.Footnote44 It is notable that they did not ask UK academic experts in this area to examine the issue, which may be viewed as a gauge for how heritage is viewed more generally within government; indeed, in January 2021 DCMS launched its ‘Culture and Heritage Capital Project’, specifically aimed at measuring the economic value of heritage and culture.Footnote45 Successive UK governments and by extension local governments have, therefore, taken a transactional view of heritage and landscape. This can be seen, for example, in the case of the most recent member of the tentative list being elevated to the UK’s preference for inscription, the Welsh Slate Landscape of Gwynedd, where the partnership leading the bid highlights on their website a report by an accountancy firm on the economic cost-benefit analysis in favour of inscription.Footnote46 Heritage is, in the UK, viewed almost entirely through a lens of economic development.

As mentioned above natural heritage is dealt with conceptually and administratively through different governmental frameworks to that of cultural heritage. In the UK, this governance and administrative division is systemic, though there has been some crossover. The epistemological problematics run deep. We can all certainly agree that the conservation of biodiversity is in crisis globally and the UK suffers particularly from this degradation.Footnote47 The threat of extinction or eradication and the inclination to preserve biodiversity has a long history, for instance in the work of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), or the World Wildlife Fund. The politics of nature conservation has an equally long and fraught history which continues to throw up competing agendas and complex issues of priorities, threats, potential futures, econometric approaches to biodiversity and the survival of species, humanity included.Footnote48 The extent to which economistic methods and perspectives have become the norm in ecological and environmental conservation work has progressed at pace in recent years.Footnote49 At the heart of this trend lie the problematics of valuation. Terms such as natural capital, eco-services and green infrastructure conceptualise biodiversity and wildlife as a product that can then be assigned an economic value; it is this that is exemplified in the Dasgupta Review,Footnote50 and is currently being echoed in the UK Government’s Culture and Heritage Capital Project.

Cultural landscapes can be hard to define in a pithy manner, requiring a reading of anthropological, archaeological, historical and socio-political scope. This is important operationally as these landscapes can seem, within a functionalist or fiscally focused mindset, to be problematic to value. For instance, in the UK both Historic England and Natural England have travelled down the path of trying to provide hard economic data on the ‘contribution’ that cultural and natural heritages make to the local, regional and national economy. Ideas such as natural capital feed directly into this kind of conceptual framework. Feelings, traditions, indeed ontology do not fit well into governmental decision-making and these aspects can be difficult (though not impossible) to package, and hence to commodify. Landscape managers thus may now find it easier to revert to hard-headed fiscal realism than to try to make any other kind of argument, particularly an attempt to argue on the basis of non-metric information. On this, the Landscape Review has some cogent advice, that national landscapes should be supported by a National Landscapes Service.Footnote51 Sounds good, but is further centralisation of governance and administration within another quango in London going to solve these problems? It may help strategically, perhaps, but the political and administrative structures that end up caring for these places are important. Bureaucracy can be easily vilified, but perhaps more consensus at a local level should be the focus, backed by central and regional agencies. International agreements and standards also play a key role. The great hope that the panel has for funding non-destructive land-management systems is through farming subsidies. Part of the focus on subsidy comes out of a value system that does not distribute resources but pools them. However, farm subsidies do not result in good landscape-level strategies. At best they will separate the wealthy and engaged farming businesses from the more destructive and this might eventually cause some change through peer pressure. Our atomising legal structures for preserving heritage in the UK will not be significantly uplifted or enabled through such a system. The essence of the problem arguably lies deeper in our society than such a fix might suggest. However, recognition of a multi-scalar value system that can be applied to landscapes is long overdue, whether they be designated as World Heritage, National Parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, or a good view. Breaking them down into valuable and non-valuable components is problematic, but that is the task that the planning system is meant to deal with.Footnote52

Heritage as an idea can be viewed as an assemblage, or perhaps a matrix of people, concepts, feelings, animals, plants and things complexly interconnected.Footnote53 There has been a so-called ontological turn in the social sciences and humanities, whereby different groups, or communities, may be seen to inhabit different ‘worlds’.Footnote54 This creates a fundamental problem for local and central government departments and there are profound implications for professionals, policymakers and training in these subjects.Footnote55 The term heritage is related, etymologically, to patrimony which signifies possessions, property and traditions inherited and to be passed on. Harrison has provided a thorough and critically detailed perspective on the subject of heritage. In so doing, he focused on a key theme, the abundance of heritage, in what he describes as the late-modern world, leading onto the relationship between heritage and modernity and the role of uncertainty in its expansion. He argues that current times are in part characterised by a hugely expanded quantum of heritage, where almost anything can be perceived as ‘heritage’ alongside an increasingly sophisticated bureaucracy for recording and managing aspects of the past.Footnote56 A western notation of value has often dominated the categorisation of heritage, in part through the operation of the World Heritage Committee, and he links the growth in heritage to a number of crises and shifts in society associated with globalisation, deindustrialisation and anxiety arising through experiences of economic uncertainty. Harrison notes that heritage is not primarily about the past but rather may relate to negotiations in and around the present and what the future may look like.Footnote57 What UNESCO would consider as cultural heritage does not include natural heritage reflecting that agency’s formulation. Other agencies at regional or national levels may have formulated different categories, orders, listings and priorities. Within the UNESCO formulation, the concept and the system for dealing with heritage is almost always perceived and discussed as a positive quality; also implied is a sense of threat, loss or vulnerability. An industry has developed to identify, preserve, manage and exhibit the many forms of heritage which are important to the way that globalised contemporary societies view themselves and indeed operate.Footnote58 The history of classification and what it can end up telling us about values and hegemony is fruitful ground for further inquiry here and may lead to a better exploration of the power structures involved and how these can be negotiated.Footnote59 The role of nostalgia and sentimentality in heritage is a further clearly relevant theme for further enquiry. The recent preoccupation with certain versions of the British past, though not necessarily the material aspects of that past can, for example, be seen in the politics around Brexit.Footnote60

The history of heritage management in Japan is a long and interesting one. Akagawa discusses the relationship between Japanese heritage conservation policy and practices, national identity and nationalism, how they link to national interest and provide a key element of foreign policy and diplomacy.Footnote61 We can see this clearly, for instance, in the case of the sacred Island of Okinoshima, a focus of Shintō worship that lies between Japan and Korea in the Genkai Sea. It has been a place marking the passage between Japan and Korea for almost 1600 years. It is bound up inextricably in the Japanese foundation myths described in the CE 8th century history The Kojiki.Footnote62 As a result, it is layered with meanings and symbols and, as well as reflecting East Asian cultural interaction and closeness, equally represents a contested seascape and a focus of conflict between Korea and Japan.Footnote63 Okinoshima was inscribed on the World Heritage list in the summer of 2017 after a long and resource-intensive campaign. It represents an unusual choice both for the Japanese state cultural authorities and for UNESCO as it has been forbidden for women to visit, and latterly is forbidden to anyone apart from a handful of priests. Akagawa suggests that since the end of the Cold War, Japan has been effectively utilising its heritage to position itself both strategically in Asia, but also to mark its presence on the international scene. These mixed motivations include commercial interests but there is an aim, more generally, to be viewed as a ‘good global citizen’ serving the interests of humanity more widely. Hence, Okinoshima seems to fulfil a layered, though in some cases contradictory, set of objectives.

UNESCO places much stock in the concept of authenticity. Clearly it is a difficult term to both define and then to utilise in an operational context. The word derives from the Latin authenticus, meaning original. It is cognate with ‘true’ and ‘sincere’ and its use in a modern context, since the 18th century, has developed alongside romanticism. It does not provide a value per se but rather may be thought of as the condition of an object in relation to specific qualities – a work of art, say, or a monument, need to be recognised in their context and the relevant values derived as such. Importantly, Assi argues, authenticity cannot be added to the subject but can be revealed only so far as it exists. Values are, instead, subject to cultural and educational factors, and may change through time.Footnote64 Authenticity is arguably a Eurocentric term referring to materially original or genuine artefacts.Footnote65 Use of the term dates back to the Venice Charter 1964 which provided guidance on a number of heritage-related terms including historic monuments, conservation, restoration, historical sites, excavations, and publication.Footnote66 Japan did not become a signatory to the World Heritage Convention until 1992. Its active participation is marked by the hosting of the Nara Conference on Authenticity in 1994 resulting in The Nara Document on Authenticity.Footnote67 This is arguably Japan’s most significant contribution to the development of the idea of World Heritage and hence more generally to cultural heritage, along with its subsequent involvement in the formulation of legal instruments for the safeguarding of intangible or immaterial heritage.Footnote68 The document represents a major reprisal of the concept of authenticity as a working model for the management of heritage. It aimed to widen the bureaucratic recognition of cultural diversity and the multiplicity of ways that heritage can be conceived and protected in a range of cultural contexts. It is commonly seen as recognising cultural differences between East and West. Notably, Japan’s long history of conservation dating back to the Nara period (c. CE 8th century), as exemplified by the Shōsōin (正倉院), a treasury belonging to the Imperial Family and found at Tōdaji (東大寺) Temple, Nara, which contains a range of artefacts, some from locations as distant as Persia. Much of the approach to heritage within the Nara Document comes out in the Japanese approach to heritage conservation more generally, elements of which date back at least to the Meji Restoration.Footnote69 The Nara Document marks a turning point in UNESCO’s view regarding the relationship between tangible and intangible heritage, establishing that the two were inseparable.Footnote70 Even with this broadening in scope, the term authenticity still remains problematic. It can be argued that authenticity can be deconstructed into three main aspects: the pragmatic – functional, what things do; the natural – what they are or are made from; and the historical – where they originate and what their subsequent biography consists of.Footnote71 We can look at the epistemology of the concept to help with situating it, as Graves-Brown does, through examining cases of medieval religious forgeries and making a link, via Kopytoff,Footnote72 between authenticity, value and, ultimately, commodity; then also connecting these concepts to experience. The Nara Document identifies an issue: ‘It is … not possible to base judgements of values and authenticity within fixed criteria. On the contrary, the respect due to all cultures requires that heritage properties must be considered and judged within the cultural contexts to which they belong’.Footnote73

World Heritage Diverging

Lynn Meskell’s recent historical examination of UNESCO and World Heritage helps to contextualise the approaches to various heritages taken since the institution’s inception in 1945.Footnote74 Meskell takes us through a number of historical stages beginning with what she describes as a late 1940s post-war utopian vision for what UNESCO could achieve: steering the fate of civilisation. This vision is in significant part attributed to Julian Huxley (brother of Aldous): ‘in many ways (Huxley) embodies a bygone age of belief in utopian social engineering, development and progress, cultural internationalism and a voracious intellectualism that were all tied up with the end of empire. His is often called a “planetary utopia”, nothing less than a global vision for an ideal polity through the creation of a united world culture. The past constituted what Huxley would call, “a unified pool of tradition”, for the human species’.Footnote75 The concept of universal value can thus be explained in its historical context. From these lofty but none-the-less colonial beginnings, aims, to say nothing of vision, later become much muddier with national interests and international politics unsurprisingly coming to the fore.Footnote76 Meskell also charts a sort of schism between the study of archaeology and the practice of World Heritage inscription. Prior to the 1972 World Heritage Convention UNESCO had been mainly concerned with the rescue of archaeological sites, such as the massive landscape-scale rescue and engineering programmes undertaken to mitigate the destruction of Nubian sites and monuments by the construction of the Aswan High Dam.Footnote77 A similar trajectory from heroic rescue to bureaucratic preservation/conservation can be chartered in the subject’s history in a number of influential countries, not least the UK and Japan. Nostalgia and the notion of a lost modernity are notable as now influencing politics, policy and the cultural context for heritage.

Latterly, post 1972, UNESCO focused on the inscription of World Heritage and on the bureaucracy of creating and enforcing the List. This lacks a heroic narrative, numerous failures of conservation can be itemised as national bodies neglect their responsibilities under the convention, perhaps most notably the case of Venice.Footnote78 Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City clearly is a national failure in the UK, but UNESCO itself and ICOMOS have had a significant role to play here too. The World Heritage Committee placed Liverpool on the List in 2012 at around the time the Liverpool Waters development was gaining planning support from the local authority, against the advice of English Heritage (now Historic England). A delegation from the World Heritage Committee warned it would cause significant damage to the authenticity of the site and placed the site on the endangered list.Footnote79 Notably, the then UK government did not exercise their power to call in the planning application to be examined by the Secretary of State. The situation remains deadlocked. Alone it may explain the UK Government’s lacklustre attitude to UNESCO.

There is a particularly acute problem with the concept of authenticity as it is associated with urban World Heritage Sites.Footnote80 Perhaps in part, this is due to difficulties with multi-scalar values and issues of diversity of foci. Sites are inscribed based on their outstanding universal value and this needs to be of such importance that it transcends national boundaries; with urban World Heritage Sites, for instance, in the UK, significant management problems are brought about through a conflict between a preservationist ethos at the core of the World Heritage designation and the attempts by local government and developers to extract economic and social benefits through the planning system. This has led to difficulties with articulating what authenticity might be in these situations and to ICOMOS seeking to develop its own framework in 2011 for historic urban landscapes, and to get tough with national and local governments not following their proscriptions.Footnote81 Pendlebury et al. suggest that this is an endemic problem within the UK as demonstrated by the World Heritage Committee’s concerns regarding Bath and Edinburgh in addition to Liverpool.Footnote82 They further imply that tensions between the UK and the Committee came to the fore in Liverpool first, where it seems to have been apparent at the time of the nomination that significant and extensive development was both anticipated and seen as desirable by the UK authorities. This harks back to a long-running tension between conservation and modernist inclinations that can be seen as early as the Athens Charters of the early 1930s, the Restoration Charter of 1931, and the Charter of International Modernism of 1933 – revised in the Venice Charter 1964 that became the cornerstone of ICOMOS doctrine.Footnote83 For instance, tourism, as it is now practiced, was not foreseen in the 1972 Convention; where the focus was very much on cultural and natural heritage objectives for their own sake and not on utilising the badge as a marketing tool.Footnote84 Latterly this has become critical and examples abound.

UNESCO’s role can be viewed as a hangover of modernism and indeed late colonial thinking. Interestingly, as with colonialism itself, Japan was late to the party. As Meskell points out, UNESCO’s appeal to one-worldism and universality was attractive in the aftermath of the second world war but such concepts of common goals and the possibility of progress perhaps now seem naïve and are being hampered by the resurgent biases of nation-states. It is important to understand its history and its admirable ability to adapt to new conditions, which is perhaps its most enduring legacy, but without heritage being closely connected to communities, it is difficult to see how it can remain relevant.Footnote85

Conclusion

Japan has made a virtue of its exceptionalism within the context of UNESCO. That is not a path open to many other nations and has not led to harmonious relations with its neighbours. A number of the properties recently put forward for inscription on the List by the Agency for Cultural Affairs seem at some level aimed at causing regional international tension, though the reverse is also arguably true for China and Korea. The Sacred Island of Okinoshima and Associated Monuments is in this category, but the most internationally controversial Japanese inscription is probably the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining, inscribed in 2015, which, to Korean and Chinese eyes, is a celebration of the historical processes leading to the formation of Japanese Imperialism. In this sense perhaps Japan and the UK are not so different? Brexit and its weaponisation of a nostalgic view of British history have been particularly vicious in its discourse towards continental neighbours. It does portent the possibility that future heritage locations and perhaps cultural landscapes may be utilised to add to this narrative.

At the start of my exploration described here, I was interested in looking at the feasibility of inscribing new sites in England on the World Heritage List. Two sites were in my mind, Happisborough on the northeast coast of Norfolk where there is evidence for human activity dating back 900,000 yearsFootnote86 and the Norfolk Broads. The visit to Ama-no-hashidate was about looking for other ways of considering the process but also of conceptualising heritage. These three sites, at either end of Eurasia, are all likely to be affected directly by sea level rises due to climate change. Loss is inherent within the concept of heritageFootnote87; here in these three cases perhaps loss needs to be at the forefront of further work towards inscription?

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Simon Kaner, and all at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Culture, for supporting the trip to Japan in 2018 and for subsequently discussing and reading through this paper. Also, thanks to Professor Akihiro KINDA for welcoming me to the Ama-no-hashidate Conference and for discussions on Japanese cultural landscapes; and to the cultural heritage division of Kyoto Prefecture. Thanks also to Natasha Hutcheson for reading through and suggesting stylistic changes and especial thanks to James Hutcheson for drawing the map of Japan. Thanks too to Mike Dawson for discussions on the paper in advance of submission and to the two anonymous peer reviewers whose suggestions have improved it. All mistakes and misunderstandings are of course my responsibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andy Hutcheson

Andy Hutcheson is a Research Fellow with the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Culture. He is an archaeologist with interests in cultural heritage and its relationship with natural heritage and in the history of UNESCO. He is also interested in the relationship between institutions and complexity in pre- and proto-history and is currently developing a project looking at aspects of the Eurasian 'Axial Age'.

Notes

1. Ministry for Housing, Community and Local Government, Planning for the Future.

2. Holtorf, Averting loss and DeSilvery and Harrison, Anticipating Loss

3. Tilley and Cameron-Daum An Anthropology of Landscape.

4. DeSilvey and Harrison, Anticipating Loss, 4.

5. Holtorf 2006,103; Holtorrf 2015, 406

6. Tylor, Primitive Culture.

7. Bradley, An archaeology of natural places.

8. Holtorf and Fairclough, ‘The New Heritage’, 197.

9. Ibid., 198.

10. Oshita and Koizumi, ‘Recognition of national parks’.

11. Meskell, A future in ruins, 133.

12. Meek, ‘The Health Transformation Army’, 12.

13. Meskell, A future in ruins, 199.

14. UNESCO 2020, World Heritage.

15. Akagawa and Sirisrisak, ‘Cultural Landscapes in Asia’, 178.

16. Fowler, World Heritage Cultural Landscapes, 3.

17. Hoskins, The Making of the English Landscape; Darby, Domesday Geography; Akagawa and Sirisrisak,’Cultural Landscapes’, 178-179.

18. Akagawa and Sirisrisak, 179; Sauer and Leighly, Land and life.

19. Akagawa and Sirisrisak, 178-179; UNESCO, ‘Twentieth Session WHC’, 5.

20. Akagawa and Sirisrisak, 181.

21. Gissibl et.al., Towards a global history of national parks.

22. Hiwasaki, ‘Toward sustainable management of National Parks’, 3.

23. Akagawa and Sirisrisak, 187.

24. Hey, ‘Kinder Scout’; Glassby, Mass Trespass on Kinder Scout.

25. Countryside Commission, Landscape Assessment Guidance.

26. Tudor, An approach to landscape character assessment, 7.

27. Fairclough and Herring, ‘Lens, mirror, window’, 186.

28. Ibid., 187.

29. DEFRA, A Green Future; Glover, Landscape Review.

30. Senda, ‘Japan’s traditional view of nature’.

31. Akagawa, Heritage Conservation, 3.

32. Yoshino, ‘English and nationalism’, 136.

33. Glover, Landscape Review.

34. DEFRA, A Green Future.

35. UNESCO, The English Lake District.

36. Weiss, Zen landscapes, 97.

37. Ito, ‘The Muse’, 204.

38. UNESCO, Sacred sites and pilgrimage routes.

39. C.f. Breen and Teeuwen, Shintō in History.

40. Kaner et. al., Okinoshima.

41. Harrison, ‘Beyond ”Natural” and ‘Cultural’ Heritage; Morel and Bankes-Price, ‘Pathways to Engagement’.

42. New York Times 12 October 2017: The US will withdraw from Unesco, Citing its ‘Anti-Israel Bias’

43. Pendlebury et. al., ‘Urban World Heritage Sites’.

44. Price Waterhouse Cooper, ‘The Costs and Benefits of World Heritage’.

45. Valuing Culture and Heritage Capital: a framework towards informing decision making. DCMS.

46. TBR, ‘An assessment of the current and potential economic impact of heritage’; Gweynedd, ‘Wales Slate: The Nomination’.

47. DEFRA, A Green Future.

48. Latour, Politics of Nature; MacDonald, ‘Business, Biodiversity and New “Fields” of conservation’; MacDonald, ‘The Devil is in the (Bio)diversity’; Beithoff and Harrison, ‘From ark to bank’.

49. Wilhusen and MacDonald, ‘Fields of green’; Turner et.al., ‘Natural capital accounting perspectives’.

50. The Economics of Biodiversity: the Dasgupta Review. HM Treasury.

51. Glover, Landscape Review, 12.

52. C.f. MHCLG, Planning for the Future.

53. Labrador and Silberman, ‘Introduction’, 4

54. Thomas, ‘The future of archaeological theory’; Pickering, ‘The ontological turn’.

55. Labrador and Silberman, 5.

56. Harrison, Heritage.

57. Ibid.

58. Ibid., 3-7.

59. Foucault, The Order of Things.

60. Campanelle and Dassù, ‘Brexit and Nostalgia’.

61. Akagawa, Heritage Conservation, 1.

62. Heldt, The Kojiki.

63. Kaner et.al., Okinoshima.

64. Assi, ‘Searching for the Concept of Authenticity’, 60-61.

65. Rodwell, Conservation and Sustainability, 8.

66. ICOMOS 1965, The Venice Charter.

67. ICOMOS 1994, The Nara Document on Authenticity.

68. Akagawa, Heritage Conservation, 2.

69. Ibid., 47.

70. Ibid., 115.

71. Graves-Brown, ‘Authenticity’.

72. Kopytoff, ‘The cultural biography of things’.

73. ICOMOS 1994; Graves-Brown, ‘Authenticity’.

74. Meskell, A future in ruins.

75. Ibid., 3.

76. Ibid, 115.

77. Ibid., 33-37.

78. Ibid., 91-93.

79. UNESCO, ‘World Heritage Committee places Liverpool on List of World Heritage in Danger’.

80. Pendlebury et. al., ‘Urban World Heritage Sites’.

81. Ibid.

82. Ibid.

83. Rodwell, ‘The Unesco World Heritage Convention’, 68.

84. Ibid.

85. Meskell, A future in ruins, 223-224.

86. Ashton et. al., ‘Hominin Footprints’.

87. DeSilvery and Harrison, ‘Anticipating Loss’.

Bibliography

- Akagawa, N. Heritage Conservation and Japan’s Cultural Diplomacy: Heritage, National Identity and National Interest. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Akagawa, N., and T. Sirisrisak. “Cultural Landscapes in Asia and the Pacific: Implications of the World Heritage Convention.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 14, no. 2 (2008): 176–191. doi:10.1080/13527250701853408.

- Ashton, N., S. G. Lewis, I. De Groote, S. M. Duffy, M. Bates, R. Bates, P. Hoare, et al. “Hominin Footprints from Early Pleistocene Deposits at Happisburgh, UK.” Plos One 9, no. 2 (2014): e88329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088329.

- Assi, E. “Searching for the Concept of Authenticity: Implementation Guidelines.” Journal of Architectural Conservation 6, no. 3 (2000): 60–69. doi:10.1080/13556207.2000.10785280.

- Bradley, R. An Archaeology of Natural Places. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Breen, J., and M. Teeuwen, eds. Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami. London & New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Breithoff, E., and R. Harrison. “From Ark to Bank: Extinction, Proxies and Biocapitals in Ex-situ Biodiversity Conservation Practices.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26, no. 1 (2020): 37–55. doi:10.1080/13527258.2018.1512146.

- Campanella, E., and M. Dassù. “Brexit and Nostalgia.” Survival 61, no. 3 (2019): 103–111. doi:10.1080/00396338.2019.1614781.

- Countryside Commission. Landscape Assessment Guidance. Cheltenham: Countryside Commission, 1993.

- Darby, H. C. The Domesday Geography of Eastern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971.

- Dasgupta, P. “The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review.” UK Government, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport. “Valuing Culture and Heritage Capital: A Framework Towards Informing Decision Making.” UK Government, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/valuing-culture-and-heritage-capital-a-framework-towards-decision-making/valuing-culture-and-heritage-capital-a-framework-towards-informing-decision-making

- Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment. London: UK Government, 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/693158/25-year-environment-plan.pdf

- DeSilvey, C., and R. Harrison. “Anticipating Loss: Rethinking Endangerment in Heritage Futures.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26, no. 1 (2020): 1–7. doi:10.1080/13527258.2019.1644530.

- Fairclough, G., and P. Herring. “Lens, Mirror, Window: Interactions between Historic Landscape Characterisation and Landscape Character Assessment.” Landscape Research 41, no. 2 (2016): 186–198. doi:10.1080/01426397.2015.1135318.

- Foucault, M. The Order of Things. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Fowler, P. J. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes 1992-2002. Paris: UNESCO, 2003.

- Gissibl, B., S. Höhler, and P. Kupper. „Towards a Global History of National Parks. „ In Civilising nature: national parks in global historical perspectiveedited by B. Gissibl, S. Hohler and P. Kupper. New York: Berghahn Books, 2012.

- Glasby, G. Mass Trespass on Kinder Scout in 1932: And the Founding of Our National Parks. Bloomington: Xlibris Corporation, 2012.

- Glover, J. Landscapes Review. London: DEFRA, 2019.

- Graves-Brown, P. “Authenticity.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, edited by P. Graves-Brown, R. Harrison, and A. Piccini. Oxford: OUP, (2013): 219–231.

- Gwynedd, C. “Wales Slate: The Nomination.” 2016. http://www.llechi.cymru/en/The-Nomination/HeritageAtWork.aspx

- Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches. Abingdon: Routledge, 2013.

- Harrison, R. “Beyond “Natural” and “Cultural” Heritage: Toward an Ontological Politics of Heritage in the Age of Anthropocene.” Heritage & Society 8, no. 1 (2015): 24–42. doi:10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000036.

- Heldt, G. The Kojiki: An Account of Ancient Matters. Translated by Heldt. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

- Hey, D. “Kinder Scout and the Legend of the Mass Trespass.” Agricultural History Review 59, no. 2 (2011): 199–216.

- Hiwasaki, L. “Toward Sustainable Management of National Parks in Japan: Securing Local Community and Stakeholder Participation.” Environmental Management 35, no. 6 (2005): 753–764. doi:10.1007/s00267-004-0134-6.

- Holtorf, C. “Can Less Be More? Heritage in the Age of Terrorism.” Public Archaeology 5, no. 2 (2006): 101–109. doi:10.1179/pua.2006.5.2.101.

- Holtorf, C., and G. Fairclough. “The New Heritage and Re-shapings of the Past.” In Reclaiming Archaeology, edited by A. González-Ruibal, 197–210. Abingdon: Routledge, 2013. doi:10.4324/9780203068632.ch15.

- Holtorf, C. “Averting Loss Aversion in Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21, no. 4 (2015): 405–421. doi:10.1080/13527258.2014.938766.

- Hoskins, W. G. The Making of the English Landscape. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1955.

- ICOMOS. The Venice Charter. Paris, 1965.

- ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity. Paris: ICOMOS, 1994.

- Ito, S. “The Muse in Competition: Uta-awase through the Ages.” Monumenta Nipponica 37, no. 2 (1982): 201–222. doi:10.2307/2384242.

- Kaner, S., N. C. G. Hutcheson, and A. R. J. Hutcheson. Okinoshima: The Universal Value of Japan’s Sacred Heritage. London: Springer, forthcoming.

- Kopytoff, I. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by A. Appadurai, 70–73. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1986.

- Labrador, A. M., and N. A. Silberman. The Oxford Handbook of Public Heritage Theory and Practice. Oxford University Press. Oxford: O.U.P, 2018.

- Latour, B. Politics of Nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- MacDonald, K. “Business, Biodiversity and New ‘Fields’ of Conservation: The World Conservation Congress and the Renegotiation of Organisational Order.” Conservation & Society 8, no. 4 (2010): 256–275. doi:10.4103/0972-4923.78144.

- MacDonald, K. I. “The Devil Is in the (Bio)diversity: Private Sector “Engagement” and the Restructuring of Biodiversity Conservation.” Antipode 42, no. 3 (2010): 513–550. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00762.x.

- Meek, J. “The Health Transformation Army: What Can the WHO Do?” London Review of Books 6, no. July (2020): 11–16.

- Meskell, L. A Future in Ruins: UNESCO, World Heritage, and the Dream of Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government. Planning for the Future: White Paper August 2020. London: UK Government, 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/907647/MHCLG-Planning-Consultation.pdf

- Morel, H., and V. Bankes Price. “Pathways to Engagement: The Natural and Historic Environment in England.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 10, no. 3–4 (2019): 1–21. doi:10.1080/17567505.2019.1671692.

- Oshita, K., and K. Koizumi. “Recognition of National Parks Compared with World Heritage Sites in Japan among Japanese University Students with Interest in Leisure Sports Activities.” Journal of Japan Society of Sport Industry 29, no. 3 (2019): 191–198. doi:10.5997/sposun.29.3_191.

- Pendlebury, J., M. Short, and A. While. “Urban World Heritage Sites and the Problem of Authenticity.” Cities 26, no. 6 (2009): 349–358. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2009.09.003.

- Pickering, A. “The Ontological Turn: Taking Different Worlds Seriously.” Social Analysis 61, no. 2 (2017): 134–150. doi:10.3167/sa.2017.610209.

- Price Waterhouse Coopers. The Costs and Benefits of World Heritage Site Status in the UK Full Report. 2007. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/78452/PwC_fullreport.pdf

- Rodwell, D. Conservation and Sustainability in Historic Cities. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

- Rodwell, D. “The Unesco World Heritage Convention, 1972–2012: Reflections and Directions.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 3, no. 1 (2012): 64–85. doi:10.1179/1756750512Z.0000000004.

- Sauer, C. O., and J. Leighly. Land and Life. Berkeley: Univ of California Press, 1963.

- Senda, M. “Japan’s Traditional View of Nature and Interpretation of Landscape.” GeoJournal 26, no. 2 (1992): 129–134. doi:10.1007/BF00241206.

- TBR. “An Assessment of the Current and Potential Economic Impact of Heritage.” 2015. http://www.llechi.cymru/SiteElements/Dogfennau/GwyneddHeritageReport/PN03414OGwyneddHeritageFinalReportv8ExecutiveSummaryEnglish.pdf

- Thomas, J. “The Future of Archaeological Theory.” Antiquity 89, no. 348 (2015): 1287–1296. doi:10.15184/aqy.2015.183.

- Tilley, C., and K. Cameron-Daum. An Anthropology of Landscape: The Extraordinary in the Ordinary. London: UCL Press, 2017.

- Tudor, C. An Approach to Landscape Character Assessment. London: Natural England, 2014.

- Turner, K., T. Badura, and S. Ferrini. “Natural Capital Accounting Perspectives: A Pragmatic Way Forward.” Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 5, no. 1 (2019): 237–241. doi:10.1080/20964129.2019.1682470.

- Tylor, E. B. Primitive culture: Researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art and custom. 1871.

- UNESCO. “Twentieth Session, WHC-96/CONF.202/INF.10 Report of the Expert Meeting on European Cultural Landscapes of Outstanding Universal Value.” 1996. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1142

- UNESCO. “Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range.” 2004. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1142

- UNESCO. “World Heritage Committee Places Liverpool on List of World Heritage in Danger.” 2012. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/890/

- UNESCO. “The English Lake District.” 2017. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/422

- UNESCO. “World Heritage Landing Page.” 2020. http://whc.unesco.org/en/about/

- Weiss, A. S. Zen Landscapes: Perspectives on Japanese Gardens and Ceramics. London: Reaktion books, 2013.

- Wilshusen, P. R., and K. I. MacDonald. “Fields of Green: Corporate Sustainability and the Production of Economistic Environmental Governance.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49, no. 8 (2017): 1824–1845. doi:10.1177/0308518x17705657.

- Yoshino, K. “English and Nationalism in Japan: The Role of the Interecultural-communication Industry.” In Nation and Nationalism in Japan, edited by S. Wilson, 135–145. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, 2013.