?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Research focusing on climate change and cultural heritage informs heritage management and policy. Fatorić and Seekamp assessed this field up to 2015, highlighting the need for periodic reassessment of the field given the observed growth and research that documents how cultural heritage contributes to climate change mitigation and adaptation. Five years on, this systematic review reflects on the state of the art by evaluating 165 publications (2016–2020) about cultural heritage and climate change. We find the field continues to grow, and remains rich in disciplinary and methodological diversity, but predominantly represents research in and about Europe. The number of publications about integrating cultural heritage into adaptation and mitigation are increasing but remain relatively few compared to those about physical impacts on individual buildings or sites. The impact of climate change on intangible heritage has rarely been the sole focus of recent research. Although researchers are increasingly situating their research in a wider context of opportunities and barriers, vague timescales, and unspecific references to changes in the natural environment are additional limitations. This review also identified a lack of international collaboration, highlighting the urgent need for global cooperation and knowledge exchange on climate change and cultural heritage.

Introduction

Cultural heritage is an umbrella term for tangible and intangible aspects of society and culture that are valued. This includes monuments,Footnote1 groups of buildings and archaeological sites,Footnote2 as well as objects (and collections) and intangible cultural practices such as dance and storytelling.Footnote3 These forms of heritage shape individual and community identity, provide evidence for past events and contribute to wellbeing through engaging with them. Understanding the current challenges facing cultural heritage is important if it is to be conserved and passed onto future generations.

Natural environments are inherently dynamic and undergo constant change due to interactions and feedback between different parts of the Earth’s system. However, anthropogenic climate change, driven by the increase in CO2 to more than 410 ppm in 2020, has resulted in unprecedented rates of environmental change.Footnote4 As such, changes to the environment and environmental systems influence and impact heritage and its associated value(s).Footnote5 While some changes to environmental processes may contribute to or foster values ascribed to cultural heritage, others may induce, accelerate, or amplify loss.

Explicit discourse on cultural heritage and climate change first appeared in the literature in the 1990sFootnote6 and have since increasingly been a focus within these and related fields.Footnote7 In 2017, Fatorić and Seekamp conducted a systematic literature review of research published up to 2015 inclusive on climate change and cultural heritage.Footnote8 They showed that:

scholarly interest in the topic had increased over time but that the scope of research was predominantly European focused,

research was being undertaken in a diverse range of disciplines including physical science, social science and humanities and published in a wide range of journals but,

research needed to document the implementation of cultural heritage and resources adaptation to help inform and influence policy.

More recently, the literature has been reviewed by Sesana et al.Footnote9 for impacts of climate change on heritage value embedded in tangible aspects of heritage, focusing on hazards that will induce changes in material properties and understanding of the state of the art. This review represents an important synthesis of a wide range of research in several disciplines, but it does not include broader challenges and opportunities at the intersection of cultural heritage and climate change, including adaptation (and the relevant barriers), and the role of cultural heritage in enabling climate action.

These topics are increasingly gaining traction in the heritage sector: for example, the Climate Heritage Network (launched in 2018) brings together over 200 sector actors in a ‘voluntary, mutual support network of arts, culture and heritage organisations committed to aiding their communities in tackling climate change and achieving the ambitions of the Paris Agreement’.Footnote10 Similarly, the Emerging Conservation Professionals Network within the American Institute for Conservation has launched a podcast entitled Conservators Combating Climate Change,Footnote11 and the Scientific Symposium organised this year by the ICOMOS Advisory Committee will be on the theme Living Heritage and Climate Change. To support and inform these initiatives focused on policy and practice, an up-to-date understanding of the focus and characteristics of the body of relevant research within the field is needed.

These developments are set against the backdrop of increasing awareness of and emphasis on understanding bias and promoting diversity in an increasingly global society. In this context, the review published by Fatorić and Seekamp in 2017 is notable in that it included ‘meta’-characteristics of the literature, such as the geographic distribution of publications and the types of heritage they studied.Footnote12 Understanding these meta-characteristics of the literature, as a proxy for the community of researchers studying climate change and cultural heritage, provides evidence that informs efforts to diversify the field and promote equality and inclusion. A more recent review took a similar ‘scientometric’ approach to characterising this body of literature,Footnote13 covering up to 2020 in their selection criteria. However, as the authors only included literature meeting their keyword criteria in the titles, their review covers a smaller volume of literature than that of Fatorić and Seekamp, despite covering a longer time period, including publications focusing on both natural and cultural heritage and searching an additional database. Crucially, this title-limited search limits the inclusion of literature that does not include certain keywords in the title but does refer to the relevant themes (e.g. cultural heritage and climate change) in the body text. As a combination of these factors, it is difficult to draw conclusions from a comparison of these two reviews on the trajectory of the field.

In response to the need the state of the art of the field of cultural heritage and climate change, this study systematically evaluates the literature on cultural heritage and climate change published from 2016 to 2020 (inclusive) for its bibliographic characteristics and focus. The design of this review specifically attempts to produce findings comparable to the review undertaken by Fatorić and Seekamp covering the period prior to and including 2015, using thematic analysis and analysis of the meta-characteristics of publications to assess the extent to which research on cultural heritage and climate change has met their proposed agenda for change.

Material and Methods

A systematic literature review goes beyond a typical literature review: a systematic literature review’s main aim is not simply to be ‘comprehensive’ but to address a specific question, reduce bias in the selection and inclusion of studies, to appraise the quality of the included publications, and to objectively summarise them.Footnote14 They are also an important tool for informing policy,Footnote15 of which there are many examples relevant to climate change and cultural heritage, such as the UNESCO Policy document on the impacts of climate change on World Heritage propertiesFootnote16 and The Future of Our Pasts.Footnote17 Most importantly, they ‘need periodic updating to inform and support practice and policy and identify ongoing research needs ’.Footnote18

Publication Selection

To enable comparison to the previously published review by Fatorić and Seekamp (henceforth referred to as the ‘baseline review’), we have reproduced the process of publication selection previously used. Acknowledging the wide range of literature that is relevant to opportunities and challenges within the field of climate change and cultural heritage, this review thus incorporates papers that explicitly refer to both. We used the same procedure based on the Web of Science database.Footnote19 To capture relevant literature, we used five sets of English keywords, using the asterisk wildcard to include permutations of each phrase:

(a) ‘cultural resourc*’ AND ‘climat* chang*,’

(b) ‘cultural heritag*’ AND ‘climat* chang*,’

(c) ‘historic* heritag*’ AND ‘climat* chang*,’

(d) ‘heritag* site*’ AND ‘climat* chang*,’ and

(e) ‘historic* environment*’ AND ‘climat* chang*.’

This database search yielded 507 publications (including the permutations identified using wildcard asterisks in the search terms as above):

(a) Cultural heritage and climate change: 253

(b) Cultural resource and climate change: 45

(c) Heritage site and climate change: 152

(d) Historic environment and climate change: 49

(e) Historic heritage and climate change: 8

While the method of systematic review has many benefits in terms of the democratisation of identifying publications for potential inclusion, we acknowledge the limitations of this method and their implications. The limitations are primarily centred around the challenges of keyword use and identification in relevant publications.

A focus on a specific type (or types) of heritage. While additional search terms (e.g. queries specifically representing ‘intangible heritage’ or ‘built heritage’, in combination with climate change) were considered to include a wider range of types of heritage, preliminary searches revealed significant overlap in the search results with the existing search terms, or a very small number of search results. Additional search terms for specific types of heritage (e.g. earthen heritageFootnote20) were considered, but omitted to avoid potential inclusion of bias or overemphasis on particular types of heritage. Thus, the search terms were deemed by the authors to be widely encompassing and comprehensive, as well as enabling fairer comparison between this study and the baseline period (pre-2015 and 2016–2020, respectively).

Non-indexed sources. Web of Science indexes scholarly books, peer-reviewed journals, original research articles, reviews, editorials, chronologies, abstracts across 256 disciplines spanning the natural sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities. Despite its scale, there are inevitably publications that have not been indexed by Web of Science. Several examples of topical and high-quality publicationsFootnote21 were not included as they were not identified by the systematic review.

Publications within relevant special issues or volumes that did not meet the keyword search. Although collections of publications are very convenient for collating current research and perspectives on a topic, individual publications may not be identified during indexing due to their characteristics when considered as standalone publications from their context. This was evident in the case of a Special Issue (discussed in the results) on Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Urban Cultural Heritage, in which some articlesFootnote22 were included but othersFootnote23 were not, as they did not match the keywords above.

Policy and other grey literature. As policy literature is not always peer reviewed through the same processes as academic literature, it is not indexed by Web of Science. Thus, publications produced by public bodies and other non-academic organisations about policy and practice related to cultural heritage and climate changeFootnote24 are not included in this review. Thus, this review focuses on understanding state-of-the-art research, as represented by peer-reviewed and indexed publications, as an important part of developing ‘evidence-based’ policy and practice.

These limitations demonstrate the importance of correctly incorporating relevant keywords and phrases in publication metadata and full text to facilitate the collation of knowledge to inform policy and practice.

Exclusion Criteria

Criteria were defined to limit the publications: (1) non-English documents, (2) duplicate documents, and (3) documents that do not fully consider the topic of interest (i.e. do not focus on one of the five keyword combinations) in the text. From the 507 publications, 10 were excluded for being written in languages besides English, a further 61 excluded for being replicates, and 271 for not fully considering the topic of interest. This produced a subset of 165 publications, enabling a comprehensive overview of the relevant research and peer-reviewed literature during this period and a discussion of trends.

Publication Analysis

Following the analysis in the baseline review, two aspects of the publications were studied: bibliographic details and research focus. These aspects were determined for each publication in the final subset from bibliographic information as collated or reported by Web of Science and a detailed full-text reading, as appropriate. The bibliographic details of these publications were assessed by:

Publication details: title, journal, year of publication, discipline (as categorised in Web of Science based on the journal), type of publication (e.g. review, research article, etc.), bibliometrics (citations), open access status;

Author details: affiliations (type of institution and location, including indices of diversity and international collaboration), number of authors.

Discipline of primary author: we used the same set of disciplinary categories as in the baseline review but added Culture and Economics, while removing any for which we found no publications (Natural Resources and Health).

Methodological contribution: conceptual, editorial, review paper, case study. For continuity, the term case study is defined the same as the baseline review, which takes a broad view of what case study research includes, i.e. they are a particular instance or scenario used or assessed to illustrate a principle or interrogate a hypothesis

Two indices of diversity were calculated for authors and collaboration: one for institutional diversity and another for regional diversity. These indices are determined using the well-established Shannon diversity indexFootnote25:

The Shannon diversity index captures multiple scenarios of diversity well and allows them to be compared: for example, a publication with three authors with two affiliations and another with two authors with three affiliations between them are diverse in different ways, but a Shannon index allows them to be compared with a one-dimensional value.

In the baseline review, different aspects of each publication were assigned a primary singular category that was seen as representing the main descriptor (e.g. if a paper’s methodology was predominantly carried out using remote sensing data, the method was assigned as ’remote sensing’). However, to recognise the increasing importance of mixed methods and collaborative ways of working, we chose to not limit our categorisation of the focus and topic(s) to one category. Instead, within a category (e.g. methods), for each option (e.g. ’remote sensing’, ’modelling’, ’secondary data’) we applied a binary (Yes/No) categorisation to enable discussion of the co-occurrence of certain aspects (e.g. several research methods).

Publications were categorised by themes that emerged iteratively during preliminary analysis:

Region of focus: region(s) and continent(s).

Environmental drivers/changes in the natural environment: temperature, precipitation patterns (inc. RH and soil moisture), sea-level rise, ice mass change, biodiversity and ecosystem changes, and droughts and heat waves (inc. wildfires);

Types of heritage studied/considered: monuments/individual buildings, groups of buildings (urban/settlement), collections, sites (inc. archaeological sites), intangible; these additionally included an option for ‘Referred to’ when not a primary focus of the publication;

Timescales considered: non-specific, past (the twentieth century), near-future (first half of the twenty-first century), and far-future (up to the end of the twenty-first century); publications that studied time scales typically associated with anthropogenic climate change (e.g. papers focusing on long-term climate change throughout the Quaternary period) were not considered;

Research methods used: secondary data (including literature, not including remote sensing), modelling, field and lab studies, GIS/remote sensing, interviews or workshops, and questionnaires or surveys.

Benefits: knowledge, social/cultural, management and policy, resilience, and sustainability

Barriers: technical, knowledge and practice, institutional, and economic/financial

Results and Discussion

General Characteristics

We considered a total of 165 publications published between 2016 and 2020 that met the criteria. We found that more than double the number of publications were published in 2020 compared to 2016 (2020 = 51 publications; 2016 = 23 publications), and there was also a continual increase in the number of similar publications published pre-2015 as found in the baseline review. This indicates that research into the impacts of climate change on cultural heritage continues to be a growing field.

It is also important to note the >60% increase in publications between 2019 and 2020 (). It is difficult to assess if this figure is representative of a real growth in the field or instead caused by given the multiple and diverse impacts COVID-19 – with it being highlighted that some researchers were able to focus on writing up publications during lockdown periods, while others were faced with multiple challenges hindering their ability to progress with research. It will be important to trace the long-term impact of COVID on publications in this field with site closures and travel restrictions, as well as personal challenges, altering the amount and type of research that can be done during this period.

Table 1. Number of publications per year in the final analysis focused on cultural heritage and climate change from 2016 to 2020

Publication Type and Field

Publications were predominantly published in formats classified as journal articles (n = 139, 84%), compared with conference proceedings papers (n = 20, 12%) or book chapters (n = 6, 3%). This distribution of publication type has shown little change in the last 5 years indicating that academic journals are still the primary dissemination route for research focusing on the impact of climate change on cultural heritage. Of the publications considered within this research over half (n = 90) where available via an open access format (Green, Bronze, or Gold routes). This notable proportion of open access publications highlights the increasing move towards open science/research (e.g. Plan SFootnote26) for funding bodies to require research organisations to publish using open access publication routes. While publishing via open access routes can be costly for smaller institutions or organisations without funding for this purpose from research councils or similar bodies it does enable heritage practitioners and wider publics to access research at the forefront of the discipline.

Literature on cultural heritage and climate change is published in a remarkably diverse range of sources: over 100 different publication sources are represented across 165 publications. The sources with the greatest number of publications focusing on the impact of climate change on cultural heritage were as follows: Geosciences, Journal of Cultural Heritage, Climate and Sustainability (see ). Special issues were seen to have a notable impact on these figures. For example, each of these journals (except the Journal of Cultural Heritage) has published at least one Special Issue on a relevant topic:

Geosciences: Preservation of Cultural Heritage and Resources Threatened by Climate Change

Climate: World Heritage and Climate Change: Impacts and Adaptation

Sustainability: Cultural Heritage Conservation and Sustainability, Built Heritage and Sustainability

Table 2. The publication sources ranked by number of publications on cultural heritage and climate change. All sources with three or more publications present in the database are included. Asterisks indicate those known to have published Special Issues on relevant topics

The diversity of publication sources coupled with the low density of articles focusing on the impact of climate change on cultural heritage within these sources results in information on this topic being widely spread. While this means that individual articles might reach a broad audience, it also highlights the need to periodically collate this research to bring knowledge from across all involved disciplines together. Without this, relevant research might easily be overlooked by researchers who work on a similar topic but in a different field. The exception to this has been through the publication of special issues on the topic. These publications have resulted in multiple publications being published within a single journal. If these special issues can continue to successfully bring together research from multiple disciplines, they could be used to promote awareness and appreciation of the field.

Research addressing climate change and cultural heritage resources has continued to engage researchers from a wide range of disciplines and backgrounds, as was identified in the baseline review (). The top four disciplines of Climate and natural hazards (44%), Archaeology (16%), Architecture and built environment (14%), and Biodiversity and ecosystems (12%) remain the dominate disciplines. However, these categorisations can oversimplify research areas with, for example the Geosciences journal having highest number of publications but the discipline of Geology only being assigned one publication. This highlights the challenge of assigning single categories to research that is multi- or inter-disciplinary and perhaps indicates some of the challenges faced by researchers in the area when trying to assign their research to a specific discipline.

Table 3. Number of publications classified by their primary discipline (as derived from the Web of Science categorisations for each source)

The large range of publication sources and research fields indicates that this research speaks to a diverse audience and has the potential to be a truly interdisciplinary field. However, this breadth can be a double-edged sword: while this topic might engage researchers in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences, it also means that, as seen with the number of publication sources, findings can be disparate and difficult to find.

Methodological Contribution

The publications reviewed in this paper were predominantly case study-based (n = 128; 78%) with 19 conceptual papers, 14 reviews and 4 editorials. This prevalence of case study publications was also observed in the baseline review, in which 69% of publications where case study based. The case study publications predominantly investigated risks or implications of changes to climate to a given cultural heritage site. There were also a notable number of studies that addressed the impact of climate change on intangible forms of cultural heritageFootnote27). These publications continue to improve and enhance the management and conservation practices for cultural heritage – but as inherent with a case study approach, are limited in focus to one–or a couple–of heritage resources making it difficult to make broader generalisations.

Both conceptual and review publications tended to collate publications on a specific topic to make broader statements relating to policy or research. These publications have been overrepresented within regards to citations. Most publications considered within this study have low citation rates () with more than half (n = 91) having one or fewer average citations per year. The relatively low citation rate of most papers within the field could be due to the broad range of academic fields and publication sources, making it more difficult for researchers to find and cite relevant research. However, it could also be due to variation in citation cultures from discipline to discipline.Footnote28

Of the four most highly cited papers, three were reviews or conceptual papers:

‘Energy retrofits in historic and traditional buildings: A review of problems and methods’,Footnote29 2017–22 average cites per year

‘Are cultural heritage and resources threatened by climate change? A systematic literature review’Footnote30 (the baseline review), 2017–14 average cites per year

‘Climate Change and Sustaining Heritage Resources: A Framework for Boosting Cultural and Natural Heritage Conservation in Central Italy’,Footnote31 2020–10 average cites per year

Table 4. Grouped average number of citations per year for the set of publications

Authors

Publications included 495 authors with affiliations in 46 countries or political regions (hereafter referred to as regions).

Most publications, as represented by the affiliations of the first authors, are based in universities (n = 123, 75%) and other research institutes (n = 24, 15%). In contrast, only a small number of first authors had industry (n = 6), museum (n = 5), or governmental (n = 5) affiliations (each of these represents 3%); in some cases, these authors also held academic affiliations, although it was not their primary affiliation. However, of the publications with more than one author, 50% included at least one co-author with a non-university affiliation. This demonstrates that although researchers in academics may be in positions to lead a large amount of research that results in these publications, a much broader range of types of organisations are involved in cultural heritage and climate change research than solely universities.

There is also a notable diversity in the authorship of publications. However, the authorship of the publications in this study indicates that there is much greater institutional diversity compared to regional diversity: publications were more likely to include authors affiliated to several institutions but with the institutions based within the same political region. As can be observed on , the indices of institutional diversity ranged from 0.5 and 2 (median = 0.69), with only 15 publications having an institutional index equal to their regional diversity (those points on the triangle edge, e.g. having a similar level of diversity of institution and region). Some notable examples of highly collaborative publications include Xiao et al.,Footnote32 Brooks et al.Footnote33 and Ravankhah et al.Footnote34; similar metrics were found for publications by Hall,Footnote35 bolstered by their numerous international affiliations.

Figure 1. Shannon diversity indices for institutional diversity and regional diversity. These demonstrates that collaboration between different institutions within a single region is far more common than international collaboration

In contrast, 110 publications had a regional diversity index = 0 (representing no regional diversity, i.e. all authors were affiliated to institutions in the same country or political region) with a median = 0. The 3rd quartile (the index value for which 75% of the data are below) is equal to 0.56.

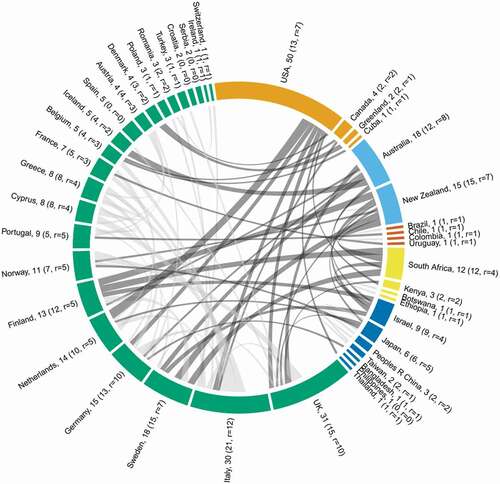

To further understand patterns of international collaboration, a chord diagram was produced (). The number of publications which had at least one co-author from a region was represented by the fraction of the circumference allocated to each region. These diagrams should be interpreted as showing instances of collaboration: since they are two-way relationships between a region, a single publication may result in more than one instance of collaboration, since more than two regions might be involved. If a publication only includes an author or author(s) from a single region the solid unlinked portion of each coloured bar for the respective region represents the number of publications (equal to the number of instances). Of the 165 publications, 110 included an author or authors from a single region, 39 included authors from two regions, and 15 included authors from three or more regions. Overall, 223 instances of international collaboration were noted, of which 62 (27%) were intercontinental collaboration. One hundred and seven (48%) of the total instances were entirely within European regions (either mono-regional or between European regions).

Figure 2. Number of instances of authorship for publications on cultural heritage and climate change from 2016–2020, colour-coded by continent. darker links = intercontinental. Nomenclature: Country name, Total publications (Number of publications with international collaboration, r = number of regions)

The USA was the most frequent region represented by instances of publication (50). However, in consideration that its population is about half that of the European continent, it can be observed that European countries have a far greater proportion of publications per capita than the USA, providing evidence that climate change and cultural heritage is primarily being dealt with as a question of European interest. Oceania (specifically New ZealandFootnote36 and AustraliaFootnote37) are represented in 33 instances. Authors based in North AmericanFootnote38 (excluding those in the USA), Asian,Footnote39 African,Footnote40 and South AmericanFootnote41 institutions are relatively rare, primarily being represented on five or fewer instances per region, except for South Africa and Israel (n = 12 and n = 9, respectively, bolstered by the many affiliations of Hall,Footnote42 and Japan (n= 6Footnote43).

It is also interesting to evaluate which regions are collaborating with others (on the assumption that co-authorship on a publication fairly reflects research collaboration. For example, despite the largest number of instances of publication, the USA was only involved in 13 instances (26% of its total instances) of international collaboration, with only 7 regions, primarily the Netherlands,Footnote44 Germany,Footnote45 Italy,Footnote46 and the UK.Footnote47

Regions Studied and Research Locality

Most research in studies focused on a specific region (n = 114; 70%) reflecting the current dominance of case study approaches to this research. Twelve studies (9%) undertook research in two or more specific regions while eight studies where undertake both at a continental and global scale.

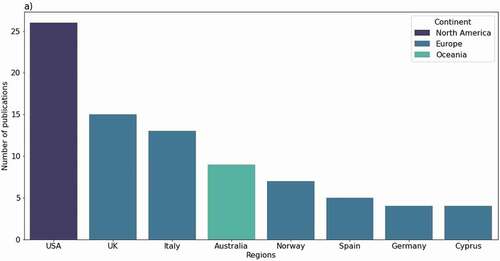

Of the research that was undertaken in a specific region, regions within Europe were the most common (n = 82) as shown in and . However, as a single region, the USA was the most frequently studied region (n = 26). It is notable that of the 165 studies, only 8 focused on Asia, 5 on Central and South America, three on Africa and four on the Polar regions. This Western bias in research has previously been noted,Footnote48 with these results indicating this bias has not substantially changed over the past 5 years. It should be noted that these results are likely to be influenced by the first exclusion criteria (publications in English – although this would only increase the reviewed publications by up to 10 additional sources, subject to the other exclusion criteria), and the choice of database. The inclusion of publications in additional databases, such as China Academic Journals Full-text Database and Duxiu, could help address this Western focus and could be a point for further research for researchers with access to such databases.

Figure 3. The region of focus of reviewed publications grouped by continent (n > 3). Note, some publications had multiple regions (n = 12) and publications that were unsituated (n = 19) or had a global, continental, or oceanic focus (n = 20) were not included

Table 5. The region of focus for all reviewed publications, grouped by continent. Note, some publications had multiple regions (n = 12) and publications that were unsituated (n = 19) or had a global, continental, or oceanic focus (n = 20) were not included

In addition, there were a notable number of studies that were unsituated (n = 19; 12%). These tended to address high-level policyFootnote49 or identify common challenges in addressing climate change impacts on heritage.Footnote50 Oceans was the research area of focus in four papersFootnote51 indicating the current bias towards research on cultural heritage on land.

The need for more diverse collaborations has also been highlighted by the continued dominance of European and North American researchers focusing on cultural heritage within their respective domains. This demonstrates that the call to address gaps in ‘traditional knowledge for preservation and adaptation’Footnote52 and the relationship between diverse knowledge systems and climate change remains open. Without addresses the Western dominance within this field of research, the field risks informing climate change policy using evidence that primarily reflects the types of heritage, climate, and values of European and North American communities.

Types of Heritage Considered or Studied

Sixty-four per cent of the publications considered a single type of heritage. Twenty-one per cent of publications studied two in combination. As shown in , most publications studied heritage sites (n = 85, including cultural landscapes and archaeological sites) and individual buildings or monuments (n = 69).

Table 6. The number of publications considering different types of heritage: percentages are shown relative to the total number of publications (n = 165). The main foci are not mutually exclusive

Within the 31% of publication that considered two or more types of heritage, it was most common that individual buildings and monuments were discussed in their contexts of heritage sites and/or urban settlements/areas. In addition to being referred to by fewer publications, intangible heritageFootnote53 and collections,Footnote54 were only rarely considered on their own, instead being considered together one or more other types of heritage.

Drivers/changes in the Natural Environment

Forty-one per cent of publications (n = 67) discuss the relationship of cultural heritage with climate change without referring to specific drivers or changes in the natural environment. The common drivers considered are precipitation (n = 44; including humidity and soil moisture) storms and extreme events (n = 40), and temperature (n = 36). Less frequently, publications considered sea level rise (n = 30), biodiversity and ecological systems (n = 25), heat and drought (n = 13, including wildfires), and ice mass change (n = 9).

When specific drivers are considered, publications typically explicitly consider between one or two drivers. 36 publications (22%) consider a single environmental driver, while 39 publications (24%) consider two. Only 23 publications (14%) consider three or more.

When considered together, the most common combination of drivers considered was sea level rise and temperature, perhaps acknowledging that these two phenomena strongly influence many other changes in the natural environment. With regard to sea level rise, this may be prevalent as at least 38 publications (23%) deal directly with coastal heritage and communities in their subject matter. Relative to their overall representation in the set of publications, storms and other extreme events are least likely to be studied in conjunction with other natural environmental drivers of change but could pose high magnitude impacts to cultural heritage. This is likely a result of the nature of extreme events: although they can be considered as part of the same global environmental system and change that drives other aspects of climate change, they are distinct in their frequency of occurrence and potential severity of impact.

Timescales Considered

Echoing the general nature of discussions around drivers of climate change, most publications (61%, n = 101) do not consider explicit time scales, instead referring to change or impacts in a non-specific. When time scales are explicitly considered, publications either consider only the past (12%, n = 20) or the future (21%, n = 34; including near- and far-future). Publications that consider both past and future time scales (e.g. future change relative to a baseline) are a minority: 10 in all (17%).

This introduces barriers to translating research into policy emerges from the nonspecificity of timescales considered or studied in the literature. Policy is evaluated against targets and metrics set in accordance with specific time periods (e.g. UNESCO’s 2030 Agenda); without evidence tied to specific timescales and horizons, the literature on climate change and cultural heritage cannot fully be integrated.

Research Methods Used

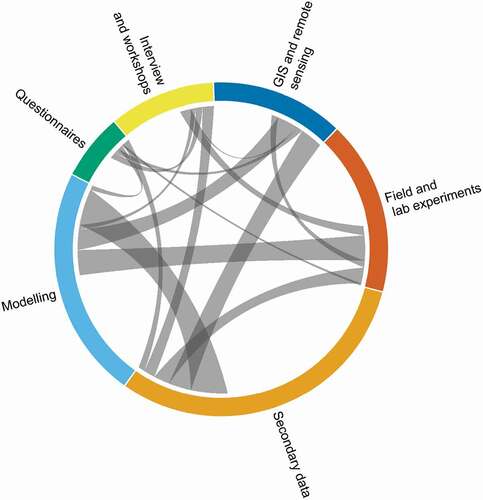

Overall, quantitative research methods and the use of secondary literature and/or data dominate the literature (). 79 publications made use of secondary literature and/or data (48%Footnote55), while 88 publications made use of at least one quantitative method (modelling, field and laboratory experiments, and remote sensing/GIS). On their own, the most common techniques were modelling (29%, n= 48Footnote56) and field or laboratory investigation (24%, n= 40Footnote57), followed by remote sensing/GIS (15%, n= 25Footnote58). In contrast, traditionally social science methods were relatively less often employed: 15% of publications used interviews and/or workshops (n= 25Footnote59) and 8% used questionnaires or surveys (n= 14Footnote60).

Figure 4. Chord diagram representing instances of research methods used in 165 publications on cultural heritage and climate change published from 2016–2020. The thickness of links indicates the relative proportion of ‘co-instance’ of these methods being used. Note that instances are not mutually exclusive: thus, publications that employed three or more research methods (n = 9) will produce several instances

Most publications used only one research method (65%, n = 107). While this may be a result of publishing models of index sources (i.e. often subject or method-specific, limited in length and scope), it points towards discordance in a field that claims to have interdisciplinarity at its core.Footnote61 When several methods are used in combination (as shown in the chord diagram in ), this is rarely a combination of the methods typically used by physical sciences (modelling, experiments, etc.) and social science methods (interviews, etc). Studies that have coupled these methods include Kittipongvises et al.Footnote62 who used GIS with household surveys to assess the flooding risk to UNESCO World heritage sites in Thailand, and Hutton and AllenFootnote63 who used workshops, surveys, and GIS to map the role of traditional ecological knowledge to minimise the risk of storm surges and tidal flooding on coastal reservations in the USA. More widely, the field is increasingly being called to provide evidence for the role of cultural heritage in addressing climate change; in this regard, using mixed methods and using qualitative methods should be fostered to incorporate perception and attitudes towards cultural heritage and climate change, particularly towards managed loss and resource allocation.

Despite the call for ‘interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, and transdisciplinary approaches to cultural heritage management, preservation, and adaptation due to the inherent complexity of the processes involved’,Footnote64 the methodologies in the literature published in the last 5 years, indicates that from a methodological viewpoint, these types of collaboration are not happening. If they are, this interdisciplinary work is not translating into peer-reviewed and indexed literature, resulting in fewer opportunities for sharing best practice and fostering further collaboration. Such collaborations could provide exciting and innovative developments, exploring the impacts of climate change on the numerous heritage values associated with cultural heritage resources.

Benefits and Barriers Identified

The increasing emphasis on research to have impact beyond furthering academic discourse is seen in this study. In the baseline study, only 10 papers reported additional benefits to undertaking their research (). However, we found that 49 papers (30%) identified a diverse range of benefits to undertaking research about climate change and cultural heritage. Across the four themes, the specific benefit most mentioned (n = 9) was improvement in integrated understanding of systems,Footnote65 enabling heritage to be placed in its wider social, economic, and environmental context. The importance of studies in mobilising public interest and social change was also highlighted by a few studies,Footnote66 with the most recent papers tending to highlight resilience-focused benefits.Footnote67

Table 7. Benefits of research on cultural heritage and climate change identified in the review

A significant increase was also seen in the number of papers identifying barriers to reducing climate change impacts on cultural heritage and incorporating it into adaptation and mitigation (). In the baseline study, few publications reported such barriers (10 papers). In comparison, we found 88 papers identified a range of barriers. Technical barriers were most cited as providing a barrier (n = 40). For example, Hall and RamFootnote68 highlight that how climate change can impact heritage can seem like a black box and Guzman et al.Footnote69 state that the monitoring tools associated with the implementation of World Heritage Sites lack the ability to fully assess the complexity of climate change. The most cited specific challenge was related to regulatory and policy challenges (n = 23), with BertolinFootnote70 highlighting issues in the flow of information and knowledge between international and local management levels; Chim et al.Footnote71 calling for the need for policy to be more flexible and Hassan et al.Footnote72 indicating the need for stronger enforcement systems. The range of barriers identified suggests that practitioners and policy makers, as well as researchers from complementary disciplines, should be involved throughout all stages of research.

Table 8. Barriers and challenges to research on cultural heritage and climate change identified in the review

Conclusions

Our systematic review of literature on climate change and cultural heritage revealed a field that has produced a rich and complex range of research from 2016 to 2020 that has continued to grow in scale since 2015. It is our ambition that it can set a framework for enabling reflection in the field of cultural heritage and climate change, inspiring similar reviews in future. This review has shown that several aspects of the field have not changed significantly from the period preceding and inclusive of 2015: the field continues to grow, the literature predominantly represents research by those in the USA and Europe studying their respective heritage and is undertaken and published by a very broad range of disciplines across the physical sciences, social sciences, and humanities and their respective journals. However, this diversity may also be seen as a double-edged sword: the literature is disparate and may be difficult to find, let alone synthesise. Perhaps in response to the call made by Fatorić and Seekamp in 2017,Footnote73 research on the implementation of cultural heritage into adaptation and mitigation strategies is growing. However, this body of research is still relatively small compared to extent of research focusing on the physical impacts of climate change on individual buildings, monuments, or sites. The review has also shown that the impact of climate change on intangible heritage has rarely been the sole focus of recent research (). Enabling and encouraging research to be driven by individuals in a wider range of organisations, such as NGOs, communities, and governmental organisations and private corporations, could be a way to strengthen the presence of this topics of intangible heritage and adaptation and mitigation in the literature.

As with most cultural heritage research, the study of the intersection between cultural heritage and climate change is collaborative: however, this review has identified that this is typically limited to institutions within the same geopolitical region. Among these collaborations, the use of a single method was very common. These siloed approaches do not lend themselves to truly transformational and interdisciplinary advances in the field, nor produce opportunities for global knowledge exchange and synergy. The significance of several publications having emphasised a lack of coordination and collaboration as a barrier to improving the response to climate change (Section 3.9) in the context of cultural heritage suggests a willingness and real desire to improve this within the research community. This could be achieved by collating understanding, sharing best practice, scaling up research, and participating in knowledge exchange facilitated by frameworks, agreements, and research networks.

To encourage and facilitate the translation of research into evidence-based and concrete strategies, this review has attempted to collate an up-to-date understanding of the focus and characteristics of the field of cultural heritage and climate change. The challenges facing cultural heritage in the face of climate change are real and complex, requiring research to produce knowledge and insight that can be transformed into practical management strategies and tangible recommendations for policy and practice. And yet, a significant amount of literature on cultural heritage and climate change approaches the latter in a vague and nebulous manner, with neglecting to discuss specific drivers of change in the natural environment and considering change generally, without reference to specific timescales. This vagueness in approach have been found to limit the translational potential of research in an archaeological context.Footnote74 Further work is needed to understand the impact of this on implementing effective policy practices, especially in the context of climate change policy, driven by time-based agendas and targets. In contrast, a much larger proportion of publications in this review (as compared to those pre-2015) identify the benefits of their research to knowledge, society, heritage management, and resilience more broadly: this embedded and strategic approach suggests the field is ready to take on the urgent challenges ahead.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Scott Allan Orr

Dr Scott Allan Orr is a Lecturer in Heritage Data Science at the UCL Institute for Sustainable Heritage. An engineer with broad interests, his research within heritage science primarily uses data-driven approaches to assess environmental impacts on the historic built environment, the use of non-destructive tools in building surveys, and incorporating value and perception into scientific evaluations. His research emphasises a holistic approach to considering the historic built environment in its context. He is the Deputy Programme Director of the MSc Data Science for Cultural Heritage, on which he teaches modules about heritage data visualisation, heritage science, and digital technologies for the historic built environment.

Jenny Richards

Dr Jenny Richardsis a Supernumerary Teaching Fellow in Physical Geography at St John's College, Oxford University, and a researcher at the School of Geography and the Environment. Her research focuses on interactions between the environment and heritage with a specific interest in the impacts of climate change. She holds a DPhil from Oxford University and an MRes from UCL, both in Science and Engineering in Arts, Heritage and Archaeology.

Sandra Fatorić

Dr Sandra Fatorić is a researcher with the TU Delft’s Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment and LDE Centre for Global Heritage and Development. Over the past decade, she has been working at the interface of social and earth sciences and has been increasingly interested in climate adaptation policy, values-based decision making, cultural heritage management, and coastal planning and conservation. She obtained a Ph.D. in Geography and MSc in environmental studies from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

Notes

1. Fatorić and Seekamp, “Are cultural heritage,” 240-241.

2. UNESCO, Protection of the World Cultural, 2.

3. UNESCO, Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, 5.

4. Tans and Keeling, Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide.

5. Richards, Orr, and Viles, “Reconceptualising the relationships between heritage and environment.”

6. Rowland, “Climate change”; and Rowland, “Accelerated climate.”

7. Cassar and Pender, Climate change and the historic environment; and Brimblecombe, Grossi, and Harris, “Climate change critical.”

8. Fatorić and Seekamp, “Are cultural heritage,” 240-241.

9. Sesana et al., “Climate change impacts on cultural heritage.”

10. Climate Heritage Network, “Climate Heritage Mobilization.”

11. “Conservators Combating Climate Change.”

12. See note 1 above.

13. Maldonado-Erazo et al., “Scientific mapping.”

14. Petticrew, “Systematic reviews.”

15. Gough, Oliver, and Thomas, Learning from research.

16. UNESCO, Policy document.

17. Climate Change and Heritage Working Group, The Future of our Pasts.

18. Fatorić and Seekamp, “Are cultural heritage,” 240-241.

19. see note 1 above.

20. Richards et al., “Deterioration risk of dryland earthen heritage”; and Ashtari, “Facing climate change.”

21. e.g. Harkin et al., “Impacts of climate change on cultural heritage”; Martens, “Mitigating climate change effects”; Fluck and Wiggins, “Climate Change, Heritage Policy and Practice in England.”

22. Brimblecombe, Hayashi, and Futagami, “Mapping Climate Change”; and Sardella et al., “Risk Mapping.”

23. Pender and Lemieux, “The road not taken.”

24. e.g. Future of Our Pasts; Fluck, Climate Change Adaptation Report; and Historic Environment Scotland, Climate Risk Assessment

25. Shannon, “A mathematical theory of communication.”

26. cOAlition S, Accelerating the transition.

27. e.g. Pieroni, “The changing ethnoecological cobweb of white truffle.”

28. Adler, Ewing, and Taylor, “Citation statistics.”

29. Webb, “Energy retrofits in historic and traditional buildings.”

30. See note 1 above.

31. Dastgerdi et al., “Climate Change.”

32. Xiao et al., “Optimizing historic preservation under climate change.”

33. Brooks et al., “African heritage in a changing climate.”

34. Ravankhah et al., “Integrated Assessment of Natural Hazards.”

35. Hall et al., “Climate change and cultural heritage”; and Hall and Ram, “Heritage in the intergovernmental panel.”

36. e.g. Chim et al., “Land Use Change Detection”; Hassan et al., “Climate change and world heritage.”

37. e.g. Forino, MacKee, and von Meding, “A proposed assessment index”; and Goldberg et al., “The role of Great Barrier Reef tourism operators.”

38. e.g. Dawson and Levy, “From Science to Survival”; and Anaf, Pernia, and Schalm, “Standardized Indoor Air Quality Assessments.”

39. e.g. Kittipongvises et al., “AHP-GIS analysis for flood hazard assessment”; and Serdeczny, Bauer, and Huq, “Non-economic losses from climate change.”

40. e.g. Debeko et al., “Human-climate induced drivers of mountain grassland over the last 40 years in Sidama, Ethiopia”; and Ombati, “Ethnology of Select Indigenous Cultural Resources.”

41. e.g. Oliveira et al., “Historic building materials from Alhambra”; Prieto et al., “Impacts of climate change on the functional deterioration of heritage buildings in South Chile”; and Fourment et al., “Local Perceptions, Vulnerability and Adaptive Responses to Climate Change and Variability.”

42. see Hall, “Heritage, heritage tourism and climate change”; and Hall et al., “Climate change and cultural heritage.”

43. e.g. Bosher et al., “Dealing with multiple hazards”; Guzman, Fatorić, and Ishizawa, “Monitoring Climate Change in World Heritage Properties”; and Brimblecombe, Hayashi, and Futagami, “Mapping Climate Change.”

44. e.g. Ghahramani, McArdle, and Fatorić, “Minority Community Resilience and Cultural Heritage Preservation”; Xiao et al., “Optimizing historic preservation under climate change.”

45. e.g. Ponti et al., “Analysis of Grape Production”; and Heilen, Altschul, and Lüth, “Modelling Resource Values.”

46. e.g. Seekamp and Jo, “Resilience and transformation of heritage sites”; and Dastgerdi et al., “Climate Change.”

47. e.g. Brooks et al., “African heritage in a changing climate”; and Dawson et al., “Coastal heritage.”

48. e.g. Fatorić and Seekamp, “Are cultural heritage,”240-241; and Sesana et al., “Climate change impacts on cultural heritage.”

49. e.g. Hall and Ram, “Heritage in the intergovernmental panel.”

50. e.g. Samuels, “Transnational turns for archaeological heritage.”

51. e.g. Perez-Alvaro, “Climate change and underwater cultural heritage”; Smith, Fox, Lee, “Changes in Air Temperature”; Anderson et al., “Sea-level rise and archaeological site destruction”; and Henderson, “Oceans without History.”

52. Fatorić and Seekamp, “Are cultural heritage” 240-241.

53. e.g. Bayliss and Ligtermoet, “Seasonal habitats, decadal trends in abundance”; Feinberg, “Uprooting wine”; and Pieroni, “The changing ethnoecological cobweb of white truffle.”

54. e.g. Turhan, Akkurt, and Arsan, “Impact of climate change on indoor environment”; Melin et al., “Simulations of Moisture Gradients in Wood”; and Anaf, Pernia, and Schalm, “Standardized Indoor Air Quality Assessments.”

55. e.g. Hall and Ram, “Heritage in the intergovernmental panel”; Orr et al., “Wind-driven rain and future risk to built heritage”; Bosher et al., “Dealing with multiple hazards”; and Dawson et al., “Coastal heritage.”

56. e.g. Boinas, Guimarães, and Delgado, “Rising damp in Portuguese cultural heritage”; Menéndez, “Estimators of the Impact of Climate Change”; and Heilen, Altschul, and L., “Modelling Resource Values and Climate Change Impacts.”

57. e.g. Wu et al., “Realization of biodeterioration to cultural heritage protection”; Mosoarca et al., “Failure analysis of historical buildings”; and Prieto et al., “Response of subaerial biofilms growing on stone-built cultural heritage.”

58. e.g. Cigna et al., “Understanding geohazards in the UNESCO WHL site of the Derwent Valley Mills”; Reimann et al., “Mediterranean UNESCO World Heritage at risk from coastal flooding and erosion”; and Kittipongvises et al., “AHP-GIS analysis for flood hazard assessment.”

59. e.g. Pieroni, “The changing ethnoecological cobweb of white truffle”; Carmichael et al., “A Methodology for the Assessment of Climate Change Adaptation Options”; Sesana et al., “Adapting Cultural Heritage to Climate Change Risks”; Bayliss and Ligtermoet, “Seasonal habitats, decadal trends in abundance and cultural values of magpie geese”; and Trõger, “Societal Transformation, Buzzy Perspectives Towards Successful Climate Change Adaptation.”

60. e.g. Lubelli, van Hees, and Bolhuis, “Effectiveness of methods against rising damp in buildings”; Fatorić and Seekamp, “A measurement framework to increase transparency in historic preservation decision-making”; and Weber et al., “Balancing the dual mandate of conservation and visitor use.”

61. Douglas-Jones et al., “Science, value and material decay.”

62. Kittipongvises et al., “AHP-GIS analysis for flood hazard assessment.”

63. Hutton and Allen, “The Role of Traditional Knowledge in Coastal Adaptation Priorities.”

64. See note 1 above.

65. e.g. Jacobs, Boronyak, and Mitchell, “Application of Risk-Based, Adaptive Pathways to Climate Adaptation Planning”; and Samuels and Platts, “An Ecolabel for the World Heritage Brand.”

66. Samuels, “The cadence of climate”; and Wright, “Maritime Archaeology and Climate Change.”

67. e.g. Pioppi et al., “Cultural heritage microclimate change”; Rivera-Collazo, “Severe Weather and the Reliability of Desk-Based Vulnerability Assessments”; and Seekamp and Jo, “Resilience and transformation of heritage sites.”

68. Hall and Ram, “Heritage in the intergovernmental panel.”

69. Guzman, Fatorić, and Ishizawa, “Monitoring Climate Change in World Heritage Properties.”

70. Bertolin, “Preservation of Cultural Heritage and Resources Threatened by Climate Change.”

71. Chim et al., “Land Use Change Detection and Prediction in Upper Siem Reap River.”

72. Hassan et al., “Climate change and world heritage.”

73. See note 1 above.

74. Rockman and Hritz, “Expanding use of archaeology in climate change response.”

Bibliography

- Adler, R., J. Ewing, and P. Taylor. “Citation Statistics: A Report from the International Mathematical Union (IMU) in Cooperation with the International Council of Industrial and Applied Mathematics (ICIAM) and the Institute of Mathematical Statistics (IMS).” Statistical Science 24, no. 1 (2009): 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS285.

- Anaf, W., D. L. Pernia, and O. Schalm. “Standardized Indoor Air Quality Assessments as a Tool to Prepare Heritage Guardians for Changing Preservation Conditions Due to Climate Change.” Geosciences 8, no. 8 (2018): 276. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8080276.

- Anderson, D. G., T. G. Bissett, S. J. Yerka, J. J. Wells, E. C. Kansa, S. W. Kansa, K. N. Myers, R. Carl Demuth, and D. A. White. “Sea-level Rise and Archaeological Site Destruction: An Example from the Southeastern United States Using DINAA (Digital Index of North American Archaeology).” PLoS ONE 12, no. 11 (2017), e0188142. Edited by Peter F. Biehl. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188142.

- Ashtari, M. N. “Facing Climate Change: The Importance of Protecting Earthen Heritage Traditional Knowledge.” 2020 ICOMOS 6 ISCs Joint Meeting Proceedings 68-77, (2020).

- Bayliss, P., and E. Ligtermoet. “Seasonal Habitats, Decadal Trends in Abundance and Cultural Values of Magpie Geese (Anseranus Semipalmata) on Coastal Floodplains in the Kakadu Region, Northern Australia.” Marine and Freshwater Research 69, no. 7 (2018): 1079. doi:https://doi.org/10.1071/mf16118.

- Bertolin, C. “Preservation of Cultural Heritage and Resources Threatened by Climate Change.” Geosciences 9, no. 6 (2019): 250. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9060250.

- Boinas, R., A. S. Guimarães, and M. P. Q. D. João. “Rising Damp in Portuguese Cultural Heritage—a Flood Risk Map.” Structural Survey 34, no. 1 (2016), 43–56. Edited by Vasco Peixoto de Freitas and João M.P.Q. Delgado. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/ss-07-2015-0034.

- Bosher, L., D. Kim, T. Okubo, K. Chmutina, and R. Jigyasu. “Dealing with Multiple Hazards and Threats on Cultural Heritage Sites: An Assessment of 80 Case Studies.” DPM 29, no. 1 (2019): 109–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/dpm-08-2018-0245.

- Brimblecombe, P., C. M. Grossi, and I. Harris. “Climate Change Critical to Cultural Heritage.” In: Gökçekus H., Türker U., LaMoreaux J. (eds) Survival and Sustainability (2010): 195–205. Environmental Earth Sciences. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-95991-5_20

- Brimblecombe, P., M. Hayashi, and Y. Futagami. “Mapping Climate Change, Natural Hazards and Tokyo’s Built Heritage.” Atmosphere 11, no. 7 (2020): 680. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11070680.

- Brooks, N., J. Clarke, G. W. Ngaruiya, and E. E. Wangui. “African Heritage in a Changing Climate.” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 55, no. 3 (2020): 297–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270x.2020.1792177.

- Carmichael, B., G. Wilson, I. Namarnyilk, S. Nadji, J. Cahill, S. Brockwell, B. Webb, D. Bird, and C. Daly. “A Methodology for the Assessment of Climate Change Adaptation Options for Cultural Heritage Sites.” Climate 8, no. 8 (2020): 88. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8080088.

- Cassar, M., and R. Pender. “Climate Change and the Historic Environment.” Report. UCL, 2003.

- Chim, K., J. Tunnicliffe, A. Shamseldin, and T. Ota. “Land Use Change Detection and Prediction in Upper Siem Reap River, Cambodia.” Hydrology 6, no. 3 (2019): 64. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology6030064.

- Cigna, F., A. Harrison, D. Tapete, and K. Lee. “Understanding Geohazards in the UNESCO WHL Site of the Derwent Valley Mills (UK) Using Geological and Remote Sensing Data.” In Fourth International Conference on Remote Sensing and Geoinformation of the Environment (RSCy2016), edited by D. G. Kyriacos Themistocleous, S. M. Hadjimitsis, and G. Papadavid. Paphos, Cyprus: SPIE, 2016. doi:https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2240848.

- Climate Change and Heritage Working Group. The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action. Paris, France: ICOMOS, 2019.

- Climate Heritage Network. “Climate Heritage Mobilization.” Accessed 17 May 2021. http://climateheritage.org/.

- cOAlition S. Accelerating the Transition to Full and Immediate Open Access to Scientific Publications. Strasbourg, France: Science Europe, 2019.

- Emma H., and Natalya S.“Conservators Combating Climate Change A New Podcast Series by the American Institute for Conservation’s Emerging Conservation Professionals Network.” News in Conservation, International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works 80 (2020): 52–55.

- Dastgerdi, A. S., M. Sargolini, S. B. Allred, A. Chatrchyan, and G. De Luca. “Climate Change and Sustaining Heritage Resources: A Framework for Boosting Cultural and Natural Heritage Conservation in Central Italy.” Climate 8, no. 2 (2020): 26. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8020026.

- Dawson, P., and R. Levy. “From Science to Survival: Using Virtual Exhibits to Communicate the Significance of Polar Heritage Sites in the Canadian Arctic.” Open Archaeology 2, no. 1 (2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2016-0016.

- Dawson, T., J. Hambly, A. Kelley, W. Lees, and S. Miller. “Coastal Heritage, Global Climate Change, Public Engagement, and Citizen Science.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, no. 15 (2020): 8280–8286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1912246117.

- Debeko, D., A. Angassa, A. Abebe, A. Burka, and A. Tolera. “Human-climate Induced Drivers of Mountain Grassland over the Last 40 Years in Sidama, Ethiopia: Perceptions versus Empirical Evidence.” Ecological Processes 7, no. 1 (2018). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-018-0145-5.

- Douglas-Jones, R., J. J. Hughes, S. Jones, and T. Yarrow. “Science, Value and Material Decay in the Conservation of Historic Environments.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 21 (2016): 823–833. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2016.03.007.

- Fatorić, S., and E. Seekamp. “Are Cultural Heritage and Resources Threatened by Climate Change? A Systematic Literature Review.” Climatic Change 142, no. 1–2 (2017): 227–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1929-9.

- Fatorić, S., and E. Seekamp. “A Measurement Framework to Increase Transparency in Historic Preservation Decision-making under Changing Climate Conditions.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 30 (2018): 168–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2017.08.006.

- Feinberg, R. “Uprooting Wine.” Food, Culture & Society 23, no. 5 (2020): 551–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2020.1807800.

- Fluck, H. “Climate Change Adaptation Report.” Technical report 28/2016. Swindon, UK; 2016. https://research.historicengland.org.uk/Report.aspx?i=15500

- Fluck, H., and M. Wiggins. “Climate Change, Heritage Policy and Practice in England: Risks and Opportunities.” Archaeological Review from Cambridge 32, no. 2 (2017): 159–181.

- Forino, G., J. MacKee, and J. von Meding. “A Proposed Assessment Index for Climate Change-related Risk for Cultural Heritage Protection in Newcastle (Australia).” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 19 (2016): 235–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.09.003.

- Fourment, M., M. Ferrer, G. Barbeau, and Q. Hervé. “Local Perceptions, Vulnerability and Adaptive Responses to Climate Change and Variability in a Winegrowing Region in Uruguay.” Environmental Management 66, no. 4 (2020): 590–599. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01330-4.

- Ghahramani, L., K. McArdle, and F. Sandra. “Minority Community Resilience and Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Case Study of the Gullah Geechee Community.” Sustainability 12, no. 6 (2020): 2266. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062266.

- Goldberg, J., A. Birtles, N. Marshall, M. Curnock, P. Case, and R. Beeden. “The Role of Great Barrier Reef Tourism Operators in Addressing Climate Change through Strategic Communication and Direct Action.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26, no. 2 (2017): 238–256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1343339.

- Gough, D. A., S. Oliver, and J. Thomas. Learning from Research: Systematic Reviews for Informing Policy Decisions: A Quick Guide. London, UK: The Alliance for Useful Evidence, 2013.

- Guzman, P., S. Fatorić, and M. Ishizawa. “Monitoring Climate Change in World Heritage Properties: Evaluating Landscape-Based Approach in the State of Conservation System.” Climate 8, no. 3 (2020): 39. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8030039.

- Hall, C. M. “Heritage, Heritage Tourism and Climate Change.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 11, no. 1 (2016): 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2015.1082576.

- Hall, C. Michael, T. Baird, M. James, and Y. Ram. “Climate Change and Cultural Heritage: Conservation and Heritage Tourism in the Anthropocene.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 11, no. 1 (2016): 10–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873x.2015.1082573.

- Hall, C. Michael, and Y. Ram. “Heritage in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Reports: A Lexical Assessment.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 11, no. 1 (2016): 96–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873x.2015.1082572.

- Harkin, D., M. Davies, E. Hyslop, H. Fluck, M. Wiggins, O. Merritt, L. Barker, M. Deery, R. McNeary, and K. Westley. “Impacts of Climate Change on Cultural Heritage.” MCCIP Sci. Rev 16 (2020): 24–39.

- Hassan, K., J. Higham, B. Wooliscroft, and D. Hopkins. “Climate Change and World Heritage: A Cross-border Analysis of the Sundarbans (Bangladesh—india).” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 11, no. 2 (2018): 196–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1516073.

- Heilen, M., J. H. Altschul, and L. Friedrich. “Modelling Resource Values and Climate Change Impacts to Set Preservation and Research Priorities.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 20, no. 4 (2018): 261–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2018.1545204.

- Henderson, J. “Oceans without History? Marine Cultural Heritage and the Sustainable Development Agenda.” Sustainability 11, no. 18 (2019): 5080. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185080.

- Historic Environment Scotland. Climate Risk Assessment for the Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site. Edinburgh, UK, 2019. https://www.historicenvironment.scot/archives-andresearch/publications/publication/?publicationId=c6f3e971-bd95-457c-a91daa77009aec69

- Hutton, N. S., and T. R. Allen. “The Role of Traditional Knowledge in Coastal Adaptation Priorities: The Pamunkey Indian Reservation.” Water 12, no. 12 (2020): 3548. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/w12123548.

- Jacobs, B., L. Boronyak, and P. Mitchell. “Application of Risk-Based, Adaptive Pathways to Climate Adaptation Planning for Public Conservation Areas in NSW, Australia.” Climate 7, no. 4 (2019): 58. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7040058.

- Kansa, C., S. W. Kansa, M. R. Kelsey Noack, C. DeMuth, and D. A. White. “Sea-level Rise and Archaeological Site Destruction: An Example from the Southeastern United States Using DINAA (Digital Index of North American Archaeology).” PLoS ONE 12, no. 11 (2017), e0188142. Edited by Peter F. Biehl. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188142.

- Kittipongvises, S., A. Phetrak, P. Rattanapun, K. Brundiers, J. L. Buizer, and R. Melnick. “AHP-GIS Analysis for Flood Hazard Assessment of the Communities Nearby the World Heritage Site on Ayutthaya Island, Thailand.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 48 (2020): 101612. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101612.

- Lubelli, B., R. P. J. van Hees, and J. Bolhuis. “Effectiveness of Methods against Rising Damp in Buildings: Results from the EMERISDA Project.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 31 (2018): S15–S22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.03.025.

- C. P. Maldonado-Erazo, José Á.-G., María de la Cruz del Río-Rama and Amador D.-S. “Scientific Mapping on the Impact of Climate Change on Cultural and Natural Heritage: A Systematic Scientometric Analysis.” Land 10, no. 1 (2021): 76. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010076.

- Martens, V. V. “Mitigating Climate Change Effects on Cultural Heritage?” Archaeological Review from Cambridge 32, no. 2 (2017): 123–140.

- Melin, C. B., C.-E. Hagentoft, V. M. Kristina Holl, and R. Kilian. “Simulations of Moisture Gradients in Wood Subjected to Changes in Relative Humidity and Temperature Due to Climate Change.” Geosciences 8, no. 10 (2018): 378. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8100378.

- Menéndez, B. “Estimators of the Impact of Climate Change in Salt Weathering of Cultural Heritage.” Geosciences 8, no. 11 (2018): 401. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8110401.

- Mosoarca, M., A. I. Keller, C. Petrus, and A. Racolta. “Failure Analysis of Historical Buildings Due to Climate Change.” Engineering Failure Analysis 82 (2017): 666–680. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2017.06.013.

- Oliveira, M. L. S., B. F. Carolina Dario, H. Z. Tutikian, C. C. O. A. Ehrenbring, and L. F. O. Silva. “Historic Building Materials from Alhambra: Nanoparticles and Global Climate Change Effects.” Journal of Cleaner Production 232 (2019): 751–758. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.019.

- Ombati, M. “Ethnology of Select Indigenous Cultural Resources for Climate Change Adaptation: Responses of the Abagusii of Kenya.” In The Anthropocene: Politik—Economics—Society—Science, 125–151. Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3319-97562-7_6.

- Orr, S. A., M. Young, D. Stelfox, J. Curran, and H. Viles. “Wind-driven Rain and Future Risk to Built Heritage in the United Kingdom: Novel Metrics for Characterising Rain Spells.” Science of the Total Environment 640–641 (2018): 1098–1111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.354.

- Pender, R., and D. J. Lemieux. “The Road Not Taken: Building Physics, and Returning to First Principles in Sustainable Design.” Atmosphere 11, no. 6 (2020): 620. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11060620.

- Perez-Alvaro, E. “Climate Change and Underwater Cultural Heritage: Impacts and Challenges.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 21 (2016): 842–848. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2016.03.006.

- Petticrew, M. “Systematic Reviews from Astronomy to Zoology: Myths and Misconceptions.” BMJ 322, no. 7278 (2001): 98–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7278.98.

- Pieroni, A. “The Changing Ethnoecological Cobweb of White Truffle (Tuber Magnatum Pico) Gatherers in South Piedmont, NW Italy.” Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 12, no. 1 (2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-016-0088-9.

- Pioppi, B., I. Pigliautile, C. Piselli, and A. L. Pisello. “Cultural Heritage Microclimate Change: Human-centric Approach to Experimentally Investigate Intra-urban Overheating and Numerically Assess Foreseen Future Scenarios Impact.” Science of the Total Environment 703 (2020): 134448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134448.

- Policy Document on the Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Properties. Paris, France: UNESCO, 2008.

- Ponti, L., A. Gutierrez, A. Boggia, and M. Neteler. “Analysis of Grape Production in the Face of Climate Change.” Climate 6, no. 2 (2018): 20. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cli6020020.

- Prieto, A. J., K. Verichev, A. Silva, and J. de Brito. “On the Impacts of Climate Change on the Functional Deterioration of Heritage Buildings in South Chile.” Building and Environment 183 (2020): 107138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107138.

- Prieto, B., D. Vázquez-Nion, E. Fuentes, and A. G. DuránRomán. “Response of Subaerial Biofilms Growing on Stone-built Cultural Heritage to Changing Water Regime and CO2 Conditions.” International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 148 (2020): 104882. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2019.104882.

- Ravankhah, M., R. De Wit, A. V. Argyriou, A. Chliaoutakis, M. J. Revez, J. Birkmann, M. Zuvela-Aloise, A. Sarris, A. Tzigounaki, and K. Giapitsoglou. “Integrated Assessment of Natural Hazards, Including Climate Change’s Influences, for Cultural Heritage Sites: The Case of the Historic Centre of Rethymno in Greece.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 10, no. 3 (2019): 343–361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-019-00235-z.

- Reimann, L., A. T. Vafeidis, S. Brown, J. Hinkel, and S. J. T. Richard. “Mediterranean UNESCO World Heritage at Risk from Coastal Flooding and Erosion Due to Sea-level Rise.” Nature Communications 9, no. 1 (2018). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06645-9.

- Richards, J., R. Bailey, J. Mayaud, H. Viles, Q. Guo, and X. Wang. “Deterioration Risk of Dryland Earthen Heritage Sites Facing Future Climatic Uncertainty.” Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (2020): 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73456-8.

- Richards, J., S. A. Orr, and H. Viles. “Reconceptualising the Relationships between Heritage and Environment within an Earth System Science Framework.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 10, no. 2 (2019): 122–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-08-2019-0099.

- Rivera-Collazo, I. C. “Severe Weather and the Reliability of Desk-Based Vulnerability Assessments: The Impact of Hurricane Maria to Puerto Rico’s Coastal Archaeology.” The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 15, no. 2 (2019): 244–263. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2019.1570987.

- Rockman, M., and C. Hritz. “Expanding Use of Archaeology in Climate Change Response by Changing Its Social Environment.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, no. 15 (2020): 8295–8302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1914213117.

- Rowland, M. J. “Climate Change, Sea-level Rise and the Archaeological Record.” Australian Archaeology 34, no. 1 (1992): 29–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.1992.11681449.

- Rowland, M. J. “Accelerated Climate Change and Australia’s Cultural Heritage.” Australian Journal of Environmental Management 6, no. 2 (1999): 109–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.1999.10648457.

- Samuels, K. L. “The Cadence of Climate: Heritage Proxies and Social Change.” Journal of Social Archaeology 16, no. 2 (2016): 142–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469605316639804.

- Samuels, K. L. “Transnational Turns for Archaeological Heritage: From Conservation to Development, Governments to Governance.” Journal of Field Archaeology 41, no. 3 (2016): 355–367. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2016.1174031.

- Samuels, K. L., and E. J. Platts. “An Ecolabel for the World Heritage Brand? Developing a Climate Communication Recognition Scheme for Heritage Sites.” Climate 8, no. 3 (2020): 38. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8030038.

- Sardella, A., E. Palazzi, J. von Hardenberg, C. Del Grande, P. De Nuntiis, C. Sabbioni, and A. Bonazza. “Risk Mapping for the Sustainable Protection of Cultural Heritage in Extreme Changing Environments.” Atmosphere 11, no. 7 (2020): 700. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11070700.

- Seekamp, E., and J. Eugene. “Resilience and Transformation of Heritage Sites to Accommodate for Loss and Learning in a Changing Climate.” Climatic Change 162, no. 1 (2020): 41–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02812-4.

- Serdeczny, O. M., S. Bauer, and S. Huq. “Non-economic Losses from Climate Change: Opportunities for Policy-oriented Research.” Climate and Development 10, no. 2 (2017): 97–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1372268.

- Sesana, E., A. Gagnon, C. Bertolin, and J. Hughes. “Adapting Cultural Heritage to Climate Change Risks: Perspectives of Cultural Heritage Experts in Europe.” Geosciences 8, no. 8 (2018): 305. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8080305.

- Sesana, E., A. S. Gagnon, C. Ciantelli, J. Cassar, and J. J. Hughes. “Climate Change Impacts on Cultural Heritage: A Literature Review.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change12, no. 3 (2021): e710.

- Shannon, C. E. “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” The Bell System Technical Journal 27, no. 3 (1948): 379–423. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x.

- Smith, S. M., S. E. Fox, and K. D. Lee. “Changes in Air Temperature and Precipitation Chemistry Linked to Water Temperature and Acidity Trends in Freshwater Lakes of Cape Cod National Seashore (Massachusetts, USA).” Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 227, no. 7 (2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-016-2916-x.

- Tans, P., and R. Keeling. “Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide.” Accessed on 3 June 2021 https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/

- Trõger, S. “Societal Transformation, Buzzy Perspectives Towards Successful Climate Change Adaptation: An Appeal to Caution.” In Climate Change Management, 353–365. Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28591-7\19.

- Turhan, C., G. G. Akkurt, and Z. D. Arsan. “Impact of Climate Change on Indoor Environment of Historic Libraries in Mediterranean Climate Zone.” International Journal of Global Warming 18, no. 3/4 (2019): 206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/ijgw.2019.10022707.

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Paris, France: UNESCO, 1972.