ABSTRACT

Before the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, mass tourism was the main driver for the unusual growth of tourist accommodations in World Heritage Cities (WHC). This paper investigates how the mass tourism pause due to the pandemic can be considered an opportunity for resetting cultural heritage policy and management practice in WHC. Selecting the Historic Centers of Siena and Florence as the case studies, we explain how the two cities experienced an unusual increase in tourist accommodation before the pandemic. By reviewing scenarios for the COVID-19 virus outbreak in Italy, we argue insights for a new cultural heritage policy and management framework that can effectively moderate mass tourism in WHC. Our findings suggest the new policies should be initiated based on a multi-sectoral and multi-level approaches in planning practice. By creating a dynamic tourism map on the macro level, international cultural heritage and tourism organisations may agree on policies that mitigate tourist flows in vulnerable WHC. On the micro-level, there is a demand for regional directives that monitor the growth of tourist accommodations in WHC. Furthermore, local communities’ engagement in decision-making may open new opportunities to work more collaboratively on the social or environmental challenges that exist in WHC.

Introduction

Some studies criticise the static and export-oriented view on heritage conservation and recommend abandoning the idea that cultural heritage is constantly under threat and needs more legal protection.Footnote1 However, the intensity and type of risks that threatening the cultural heritage sites’ tangible and intangible features can be varied and distinct, like climate change,Footnote2 natural hazardsFootnote3 and mass tourism.

Tourism is an industry with considerable economic benefits. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) report shows that international visitor arrivals had increased from 25 million in 1950 to 674 million in 2000. Such a rapid global increase has roughly doubled in the last two decades, and 1.5 billion international traveller arrivals were recorded in 2019.Footnote4 The UNWTO had also predicted a four percent increase in global tourist arrival for 2020.Footnote5 However, this projection was abolished due to the COVID-19 pandemic occurrence.

Cultural tourism has been introduced as an essential factor for local development in historic cities and rural areas.Footnote6 In this regard, designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site may maximise a site’s expected cultural and economic advantages. In addition, cultural tourism can support cultural heritage conservation practices, contribute to the transmission of cultural values, and encourage sustainable environmental practices.Footnote7 To promote cultural tourism, several studies have introduced various approachesFootnote8 and planning strategiesFootnote9 for the protection of tangible and intangible features in WHC.Footnote10 As correlations between cultural heritage and community strengthen the sense of place and identity,Footnote11 planning strategies for boosting the place image can attract more international or domestic visitors to the site.Footnote12 In terms of social benefits, a few studies explored how cultural heritage reputation is an essential component for visitor attraction and citizens’ quality of life.Footnote13

However, in the case of unsuitable management, mass tourism may impose overwhelming social and environmental impacts on local communities.Footnote14 Reports show that the World Heritage Committee has been troubled by several tourism-related challenges in WHC, basically in terms of social and environmental issues.Footnote15 The Committee, in its World Heritage Tourism Programme, declares that although cultural tourism is a driver for the sustainability and conservation of cultural and natural heritage sites, it should be managed effectively.

Mass tourism may be considered a consequence of Globalisation, where competitive global marketing has provided more low-cost and fast services to international tourism.Footnote16 Mass tourism refers to a destination that the citizens’ quality of life or visitors’ spatial experience has declined notably due to the excessive numbers of tourists on the site.Footnote17 Therefore, this phenomenon contrasts with cultural tourism objectives that aim to protect the cultural heritage values under the tourism economy’s shield.Footnote18 Mass tourism has generated new housing challenges in many European WHC in the last few years. The outcomes of a study in 2017 show that two in five European citizens suppose that mass tourism has transformed the intangible features in historic sites and acts as a threat to these sites’ function and sustainability. They believe that the fast increase in tourist accommodations due to mass tourism has led to housing issues and influenced local identity.Footnote19 For example, research in Barcelona showed that residents are forced to pay more when renting accommodation due to the high demand generated by mass tourism.Footnote20

Since the last year (2020), there has been growing concern about mass tourism impacts on the sustainability of European WHC. The well-known city of Florence, for instance, is one of these affected cities. In 2012, the Outstanding Universal Value of the Historic Centre of Florence’s statement was reviewed and revised by the Florence World Heritage and UNESCO Relationship Office at the Municipality of Florence based on a new format, which was suggested by the UNESCO Advisory Bodies, including ICOMOS, ICCROM, and IUCN. The World Heritage Committee reviewed the submitted document WHC-14/38 COM/8E. The Committee affirmed and approved the Outstanding Universal Value of the Historic Centre of Florence’s retrospective statement in its 38th session in June 2014. The new document recognises some of the most critical new threats to the Historic Centre of Florence’s integrity linked to the impact of mass tourism like a decrease in residents, an increase in traffic, and environmental pollution. In 2016, mass tourism impacts were recognised and mentioned again during the site management plan’s update.Footnote21

Since 2017, the World Heritage and UNESCO Relationship Office at the Municipality of Florence, in collaboration with Heritage Research Lab at the University of Florence, has launched a few projects to solve the mass tourism challenge and its impacts on the Integrity of the Outstanding Universal Value in the Historic Center of Florence. One of these projects, Study on the Load Capacity of the Historic Centre of Florence, aims to prove full awareness of the threat induced by mass tourism to the Historic Centre and the launch of moderation and regulatory measures.Footnote22 In this regard, the Atlas-World Heritage is another research project to address the challenges of mass tourism in five WHC in Europe, including Florence. Florence’s findings revealed that the city has remarkably undergone an unusual increase in low-quality and illegal tax-system tourist accommodations in recent years.Footnote23

Many WHC in Italy have been associated with mass tourism experiences in the last few years, which threaten the Outstanding Universal values at these sites and has brought housing challenges to these cities. This study considers the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to revise the housing policies in Italian WHC to ensure these cities remain socially sustainable in the post-pandemic time. We explore how the Historic Centers of Florence and Siena were affected by mass tourism and how it can help urban and regional planners enhance the city’s resilience and quality of life in the post-pandemic time.

Methodology

This study uses comparative case studies to improve the resilience and quality of life of WHCs in the post-pandemic time. Comparative case studies include the analysis of similar patterns across two or more cases that have a common goal. For this purpose, two Historic Centers of Florence and Siena were selected as the case studies. We collected data using a mixed-method, which includes the use of quantitative and qualitative data. In terms of the research process, we first explore how mass tourism has led to the unusual growth of illegal-tax system tourist accommodation in Florence and Siena. Our data collection tools are maps analysis, municipality statistics, and questionnaires in this step. In the following, we explain various theories about the reasons for the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus in Italy. We then completed this section by debating the different scenarios about the COVID-19 pandemic’s future, which created the opportunity to understand the relationships between illegal tourist accommodation and the risk of a virus outbreak in WHCs. Considering the social and environmental aspects of sustainability, we suggest policy insights for a novel management framework that may moderate mass tourism pressure and improve resilience and quality of life in WHC.

The Historic Centers of Florence and Siena

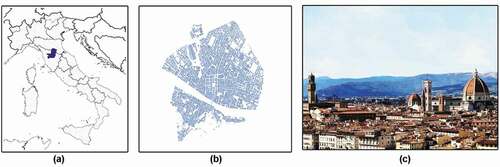

Florence is a city in Central Italy and the Tuscany region’s capital. In 2020, Florence’s population was estimated at 360.000 people, for Municipality core, and 708,000 for Metropolitan area. Florence’s residents have an average age of 42, lower than the Italian population’s average age, which is 45.7 years. The Historic Center of Florence can be regarded as an exceptional historical and cultural urban achievement, the outcome of long-lasting creativity, encompassing many sculptures, churches, historic buildings, and art masterpieces. Its 600 years of exceptional artistic activity can be observed in the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral, the Uffizi Palace, and the church of Santa Croce, followed by the works of Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, and Botticelli (). Florence had a remarkable impact on the development of Renaissance fine arts and architecture in Italy and Europe. With an area of 505 hectares, the Historic Centre of Florence was declared by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1982.Footnote24 While a candidate site needs to meet at least one of the ten selection criteria to be eligible for designation as a World Heritage Site, the Historic Center of Florence has met five criteria, which privilege it as an exceptional example in the world.

Figure 1. The historic city of Florence in Italy; (a) The Tuscany region in Central Italy; (b) The Historic Center of Florence; (c) The Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral.Footnote25

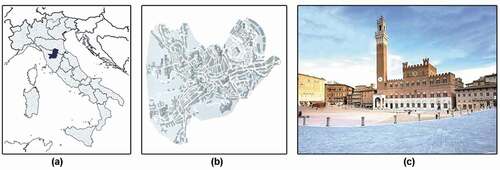

Siena is a historical city in Central Italy. Located in the Tuscany region, Siena is the province of Siena’s capital. In 2020, Siena’s population was estimated at 54.000 people, for Municipality, 120.000 with hinterland, and 58.2% of Siena’s residents have an age range between 18 to 64 years old.Footnote26 Siena is an excellent medieval city that has conserved its historical integrity and quality. Siena significantly impacted art, architecture, and city planning principles in Italy and Europe during the Middle Ages. The entire city of Siena was built around the Piazza del Campo (). Siena has conserved its Gothic features, which were acquired between the 12th and 15th centuries. In this period, Siena’s artists like the Lorenzetti brothers and Duccio influenced the art principles in Italy and Europe. With an area of 170 hectares, the Historic Center of Siena was declared by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1995. The Historic Center of Siena has met three UNESCO site selection criteria, which privilege it as a globally exceptional example. Siena and its Historic Center are viewed as popular tourist destinations for their outstanding cultural values. In 2008, the city was one of Italy’s most visited tourist destinations, with more than 163,000 international visitors. It is a city well-known for its medieval cityscape, museum, and arts.

Figure 2. The historic city of Siena in Italy; (a) The Tuscany region in Central Italy; (b) The Historic Center of Siena; (c) The Piazza del Campo.Footnote27

Tourism Statistics in the Tuscany Region

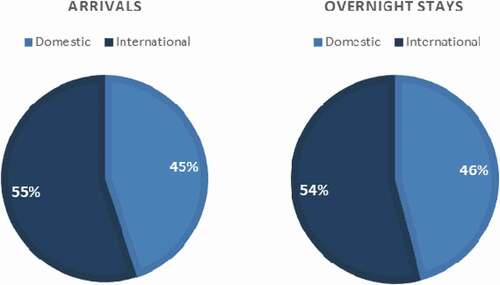

Each year, it is estimated that the number of overnight stays in official establishments surpasses 44.5 million in the Tuscany region. Considering the demand and increase in unofficial accommodation, this estimation may reach 90 million overnight stays in total. In the Tuscany region, tourist flows are divided equally between foreigners and domestics, while foreigners slightly outnumber Italians: 55% of arrivals and 54% of those present in total ().

Figure 3. Tourist flows in the Tuscany region.Footnote28

Statistics show that, on average, Italian visitors stay 3.6 nights in the region, and this length is 3.4 nights for foreigners. Also, the months in which there are notable inflows of travellers vary from April to October.Footnote29

Mass Tourism’s Impact on Florence

The statistics provided by Florence’s municipality show the city of Florence had a 28% increase in tourist presence from 2012 to 2019. This trend continued and exceeded by eight percent more in 2016 and 2017, and in just seven years 2012/2019 increases by almost 40%. The trend collapses in 2020 due to the effect of the pandemic. ().

Table 1. Tourist presence in FlorenceFootnote30

Although tourism is assumed to achieve sustainable development goals, it can also easily disrupt the WHC’s functionality and pose new societal and environmental pressures. In Florence, mass tourism has established a new trend in which city apartments are unusually changing to tourist accommodations.Footnote31 This phenomenon is a threat to the Outstanding Universal Value of Florence and has notably influenced the real estate market in the city. Mass tourism is a multi-dimensional and complex phenomenon that may threaten the inhabitants’ quality of life. Due to historic towns’ limited capacities, the unmanaged increase of international tourism has posed several environmental pressures to these places like transportation services and air pollution.Footnote32 Besides, mass tourism has driven new societal issues in World Heritage Sites regarding security concerns and citizens’ rights to the city.Footnote33 Accordingly, mass tourism can easily revoke the social, economic, and environmental functionalities in WHC, and in its worsening scenarios, it can raise social conflicts between residents and visitors.

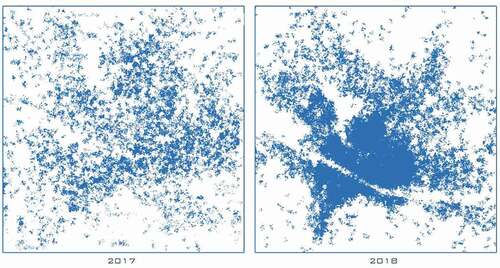

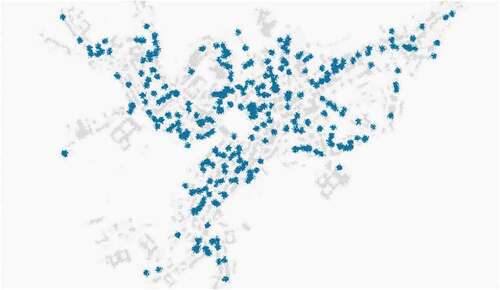

As the COVID-19 pandemic has appeared as a new management challenge, WHC needs a new management framework to moderate the risks and improve residents’ quality of life in tourist destinations.Footnote34 In Florence, the increase in tourism has led to the unusual growth in illegal tourism accommodations. shows how mass tourism consumes the city’s houses and infrastructures, generating a socially and environmentally fragile place.

Figure 4. Unusual process of emerging informal tourist dormitories in Florence.Footnote35

In Florence, mass tourism has been a significant factor in converting residential buildings into informal tourist accommodations. Many tourist dormitories have been founded based on an illegal tax system and inadequate health quality conditions. In addition to the housing challenges, monitoring the health quality of these illegal and rapidly growing accommodations can be challenging for city health organisations. By analysing the urban facades of dei Serragli in the Historic Center of Florence (), Ridolfi showed that almost 35% of each house’s space is allocated to tourist dorms.Footnote36 Taking the COVID-19 pandemic’s learning into consideration, this process’ continuity means more vulnerability of WHC to epidemics and pandemics, as the city health organisations have limited resources to monitor these places’ quality constantly.

Figure 5. The urban facade of dei Serragli in the Historic Centre of Florence. Red rectangles show the informal tourist dormitories.Footnote37

In December 2018, the Department of Architecture at the University of Florence designed a questionnaire to understand how residents perceive Florence’s image. The questionnaire was answered by 177 Florentine residents in the last week of the same December. Almost 70% of the participants believed finding affordable housing has been ‘difficult’ in Florence due to mass tourism and increased tourist accommodations ().

Table 2. Florentine residents’ image of the housing challengeFootnote38

The residents supposed that many work openings are limited to tourist services, and seasonal changes in visitor flows make it ‘difficult’ to find a secure job in the city. Therefore, the city’s tourist orientation has not been successful in meeting the surveyed group’s social expectations.

Mass Tourism’s Impact on Siena

According to the Municipality of Siena’s statistics service in 2019, the accommodation establishments in the Municipality of Siena are 340 with an accommodation capacity of 7,834 beds, of which 46% are in hotel facilities and 54% in non-hotel facilities. There were increases in tourist arrivals and presences in Siena. The city recorded arrivals equal to 524,204 (+2% compared to 2018) and presences equal to 1,103,788 (+4% compared to 2018). In 2019, the hotel occupancy rate, percentage of bed use increased by two percentage points compared to 2018 (). It is emphasised that the current data of the Tourist Observatory of the Municipality of Siena does not take into account the contribution provided by the new forms of hospitality. Starting from 1 March 2019, with the introduction of the obligation to register tourist rentals (private apartments for tourist purposes), the municipality, for the first time, surveys the flow of arrivals and presences of this type of accommodation.Footnote39

Figure 6. Unusual process of emerging informal tourist dormitories in Siena.Footnote40

By analysing the Historic Center of Siena’s urban facades (), Kokoshi showed that almost 31% of each house’s space is allocated to tourist dorms. Considering the COVID-19 pandemic learning, increasing illegal tourist accommodation means more vulnerability of WHC to epidemics and pandemics, as the city health organisations have limited resources to monitor these places’ health quality.

Figure 7. The urban facade of the Historic Centre of Siena. Red rectangles show the informal tourist dormitories.Footnote41

The Outbreak of the Covid-19 Virus in Italy

After reports of several pneumonia samples in Wuhan in December 2019, a new Coronavirus was explored and termed COVID-19.Footnote42 The virus was never detected before its emergence in Wuhan in December 2019. The spread of dangerous respiratory COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020,Footnote43 and it has recorded more than 2.03 million deaths by January 2021.Footnote44 COVID-19 is a respiratory virus that spreads fundamentally through in-person contact (droplets of saliva, coughing, and sneezing). Touching surfaces infected with the virus and then touching the nose, eyes, or mouth before sanitising or washing hands is another known way of transmitting the COVID-19 virus.Footnote45

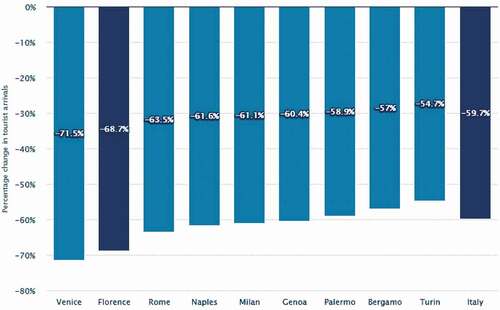

There are various speculations about how the COVID-19 virus spread in Italy and caused a national lockdown. Del Buono et al. (Citation2020) recognised seven factors as the most important determinants for the spread of the virus in Italy, including the average age of the population, the efficiency of the health systems in crisis, accessibility to personal protective tools, lack of risk plans, viral mutation, timely quarantines, and surveillance tests. They also highlighted the regional mobilities associated with the industries and tourist flows as supplementary possibilities for the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus in Italian regions.Footnote46 Murgante et al. (Citation2020) explained the high impact of COVID-19 on Italy in terms of geographical, planning, and medical perspectives. Besides the rapid mobility through the country’s fast trains, they added Nitrogen-related air pollutants as a potential factor for the virus outbreak in Northern Italy and the Po Valley area.Footnote47 In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has paused mass tourism impacts on WHC in Italy. shows that Italy has recorded a likely 60 percent decrease in its tourist arrivals in 2020. With −68.7%, Florence is the second Italian city in terms of minor tourist arrivals in 2020. Therefore, Italian WHC have an excellent opportunity to revise their own housing policies to support their residents’ expectations and welfare.

Figure 8. The COVID-19 pandemic impact on tourist arrivals in Italy in 2020.Footnote48

The World Health Organization and national health authorities have introduced detailed recommendations, like mask-wearing, social distancing, and sanitising hands to enhance personal safety. The national quarantines’ learning due to COVID-19 globally and in Italy highlights the tips below.

The novel virus’ origin can remain unknown for a long time, and it can be spread more rapidly through in-person interactions;

The virus diseases know no geographical boundaries and can spread rapidly in more regions;

Lack of health protocols and monitoring accelerates the incidence of the virus disease;

Preventive measures and directives are essential in reducing casualties.

WHC during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Many countries endeavour to control and slow the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus using various measures. These activities include quarantine, limiting social gatherings and on-site working, closing public leisure services like restaurants and pubs, and closing schools and universities.Footnote49 The COVID-19 pandemic’s key learning is the importance of social distancing to limit the spread of the virus, which may continue for an unknown period in the post-pandemic time due to the uncertainty ().

Table 3. The future of the COVID-19 pandemicFootnote50

As shows, there are different scenarios about the COVID-19 pandemic’s future, making it challenging to predict the return time to the routine. The pandemic is an excellent opportunity for the WHC in Europe to moderate the long-lasting housing issue in these sites and promote the health level of these cities in terms of novel risks. The implementation strategies for the protection of WHC have been limited to minimising citizen movements to the strict minimum to lessen transmission risks.Footnote51 However, WHCs require a novel management framework that enhances their resilience in terms of mass tourism and pandemic.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Florence implemented several strategies to manage the pressure of mass tourism in the city. Through novel regulations, the opening of new bar-restaurant activities has been limited in the Historic Center of Florence. This measure puts a three-year delay for the opening of food and beverage services. The Firenze Card is used as a promotional tool for spreading tourism in the whole city. The card allows entrance to 72 museums, historical monuments, villas, and gardens.Footnote52 Indeed, there is a lack of specific directives of regulation that restricts the activity of illegal tourist dormitories in the city. In other words, the post-pandemic era requires a robust management framework that protects public health in WHC by stopping the activity of illegal tourist accommodation.

Resetting Cultural Heritage Policies and Management of WHC in Post-Pandemic Time

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Italy was placed in fifth place in terms of international tourist arrivals by the UNWTO.Footnote53 Tourism development has been considered a potential tool for the protection of historical settlements in the Mediterranean region. For this purpose, Mediterranean countries have applied various strategies to develop cultural tourism activities. In Italy, for instance, the ‘Diffuse Hotel’ has been introduced as a strategy that allows travellers to visit Italy through a typical, historical, and comfortable hotel. It refers to a single hotel in which rooms are located separately to recover historical villages and towns. The European Community also encourages the establishment of ‘Spread Hotels’ to develop the economic capacity of depressed areas by financing refurbishment plans.Footnote54 However, this narrative is entirely distinct and challenging in WHC.

The increase in low-cost flights has dramatically brought international tourism flows to WHC, especially in Europe. Mass tourism has generated novel and important social outcomes, such as affordable housing problems. Many WHC like Florence, Venice, Pompeii, and Rome have developed measures to manage tourist arrivals in Italy. However, the site managers have gradually noticed that the implementation process is quite challenging and, in some cases, almost impossible. On the other hand, directing the visitor flows to other country areas has been implemented as a potential solution for managing mass tourism in WHC.Footnote55 However, it is unclear if this strategy has been effective enough to mitigate the mass tourism pressure on the WHC. In Florence, for example, the survey group believed that finding affordable housing is still ‘very difficult’ in this city. In this regard, many Italian scholars have argued that limiting the oversupply of tourist accommodations in WHC needs a new policy and management framework.Footnote56

After observing the first COVID-19 cases on 30 January 2020, Italy’s government commanded a national quarantine on 9 March 2020, limiting the inhabitants’ mobility except for essential needs, like food supplies, permitted work, and medical care.Footnote57 There are several scenarios about the causes of high infection and death rate in Italy due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Del Buono et al. (Citation2020) introduce some potential determinants for the virus’ rapid and unusual outbreak in Italy, namely community ageing, the health system’s efficiency, access to personal protective tools, viral mutation, disaster plans, timely quarantine, and less rate of testing. They also reflect the national mobility and visitor flow as supplementary causes for the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus in Italian regions.Footnote58 Besides, Nitrogen-related air pollutant is another speculation for the fast and sever spread of the virus in the country.

Our analysis in the Historic Centers of Florence and Siena reveals how illegal tax-system tourist accommodations increased unusually in these two cities before the COVID-19 pandemic. This process has affected residents’ social welfare in terms of finding affordable housing in these cities. Besides, many of these tourist dormitories are working under the illegal tax system. Our study shows a lack of regional directives in Italian WHC that ban these accommodations’ activities. The rapid growth of illegal accommodations implies that health institutions cannot monitor their health status. It means that in addition to the housing challenge, public health is a secondary concern for the rapid growth of illegal accommodations in WHC. Finally, accommodating many tourists in the WHC means less social distancing in public spaces in the post-pandemic time. Hence, according to the pandemic’s learning, one may consider how mass tourism continuity can expose WHC to infectious diseases.

To enhance the WHC’s resilience and quality of life in the post-pandemic time, two simultaneous actions should be performed at the local and international levels. The Italian government’s performance to prioritise the citizens’ safety over economic interests could be followed as a public strategy for supporting social welfare and ensuring health safety in WHC. In this regard, related cultural heritage and tourism international organisations, like UNESCO and UNWTO, need to agree on policies that reduce low-cost transportation services to WHC suffered by mass tourists. Although such legislation can significantly reduce international tourist arrivals in WHC, it is unclear to what extent airlines and the tourism sectors tend to follow the new regulations, specifically in difficult economic situations, like the COVID-19 pandemic. On the micro-level, WHC requires participatory policies that stop the illegal tourist accommodation’s activity. Such a limitation by itself has a significant role in decreasing international tourism arrivals to the city. However, community engagement is understood as comprising a one-way, top-down educative process. The issue with this approach is that it does not encompass a two-way comprehension of heritage values, especially from the vision of communities that inhabit and engage with it daily.Footnote59 Therefore, to avoid ‘a general top-down policy’, the important consideration on the micro-scale should be reflecting the local community’s voice in the decision-making process, besides the upscaling of the inter-disciplinary skills to implement them.Footnote60 This micro-scale engagement may open new opportunities to work more collaboratively on other social or environmental challengesFootnote61 from a broader vision, making WHCs more resilient. For instance, in addition to improving housing challenges and converting the illegal tax-system tourist accommodations to city apartments, this approach may help health institutions dedicate their resources to monitoring city hotels more effectively. Nevertheless, to what degree are property landlords ready to devote economic interests to public welfare in WHC is an unanswered question.

Conclusion

Before the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, mass tourism was a common challenge in many European WHC. In Italy, this phenomenon has led to the unusual growth of illegal tax-system tourist accommodations, making it difficult for residents to find affordable housing. This study reflects the mass tourism pause due to the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to enhance the resilience and quality of life of WHCs in the post-pandemic time by resetting policy and management practices in WHC. By explaining the reasons for the unusual growth of tourist accommodations in Florence and Siena, we argued how this trend’s continuity might threaten the quality of life in WHC in post-pandemic time.

We recommend that new cultural heritage policies adopt a multi-sectoral and multi-level approach to moderate the long-lasting issue of mass tourism in WHC effectively. While macro-level policies need the agreement of international organisations, new cultural heritage policies should reflect the local communities’ voice at the micro-level. This two-way communication may open new opportunities to work more collaboratively on other social or environmental challenges in WHC in post-pandemic time.

Nevertheless, the recession due to the COVID-19 pandemic will remain the main barrier, which means this approach’s success depends on to what extent the tourism industry (at the macro-level) and property owners (at the micro-level) are ready to accept this shift.

Authors’ contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmadreza Shirvani Dastgerdi

Ahmadreza Shirvani Dastgerdi is a Visiting Fellow at the Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. He obtained his Ph.D. in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Florence in Italy. His research is focused on the sustainable management of cultural heritage resources.

Giuseppe De Luca

Giuseppe De Luca is a Full Professor of Urban Planning and the director of the Department of Architecture at the University of Florence in Italy. His research is focused on cultural heritage policy and spatial transformation.

Notes

1. Legnér and Leijonhufvud, “A Legacy of Energy Saving,” 40–57.

2. Dawson et al., “Proposed Policy Guidelines for Managing Heritage at Risk Based on Public Engagement and Communicating Climate Change,” 1–20; Orr, Richards, and Fatorić, “Climate Change and Cultural Heritage,” 1–43; Stucchi et al., “Assessment of Climate-Driven Flood Risk and Adaptation Supporting the Conservation Management Plan of a Heritage Site,” 22; and Bekele, Tolossa, and Woldeamanuel, “Local Institutions and Climate Change Adaptation,” 147.

3. Dastgerdi et al., “Heritage Waste Management,” 76–89

4. World Tourism Organization, UNWTO Tourism Highlights.

5. World Tourism Organization, “International Tourism Growth Continues to Outpace the Global Economy,” 2.

6. Pedersen, Managing Tourism at World Heritage Sites, 16–17.

7. Di Giovine, The Heritage-Scape; and Bandarin, World Heritage, 36–40.

8. Dawson, “Values in Heritage Management,” 259–261.

9. Dastgerdi and De Luca, “Religious Differences and Radical Spatial Transformations in Historic Urban Landscape,” 191–203.

10. Joudifar and Olgaç Türker, “A ‘Reuse Projection Framework’ Based on Othello’s Citadel and Cultural Tourism,” 23–31; and Mısırlısoy, “Towards Sustainable Adaptive Reuse of Traditional Marketplaces,” 186–202.

11. Dawson, “Valuing Heritage (Again).”

12. Dastgerdi and De Luca, “Boosting City Image for Creation of a Certain City Brand.”

13. Dastgerdi and De Luca, “Strengthening the City’s Reputation in the Age of Cities,” 3–7.

14. World Heritage Committee, “Adoption of Retrospective Statements of Outstanding Universal Value, 38 COM 8E.”

15. Bandarin, World Heritage.

16. Alderighi and Gaggero, “Flight Availability and International Tourism Flows,” 2–5.

17. Dodds and Butler, “The Phenomena of Overtourism,” 519–528; Dastgerdi and De Luca, “The Riddles of Historic Urban Quarters Inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List,” 152–163; and Goodwin, “The Challenge of Overtourism,” 1–5.

18. De Luca et al., “Sustainable Cultural Heritage Planning and Management of Overtourism in Art Cities,” 3929.

19. Gurran and Phibbs, “When Tourists Move In?” 80–92.

20. Leadbeater, “Anti-Tourism Protesters in Barcelona Slash Tyres on Sightseeing Buses and Rental Bikes.”

21. Francini, “The Management Plan of the Historic Centre of Florence.”

22. Francini and Bocchio, “Monitoring of the Management Plan of the Historic Centre of Florence.”

23. Heritage Research Lab, “ATLAS WORLD HERITAGE – Heritage in the Atlantic Area Sustainability of the Urban World Heritagesites.”

24. World Heritage Centre, “Historic Centre of Florence.”

25. World Heritage Centre.

26. City Population, “Siena.”

27. World Heritage Centre, “Historic Centre of Siena.”

28. Statista, “Tourist Overnight Stays in Florence 2020.”

29. Tuscany Tourist Board, “Tuscany Regional Survey.”

30. Municipality of Florence, Statistica Del Turismo.

31. Dastgerdi, De Luca, and Francini, “Reforming Housing Policies for the Sustainability of Historic Cities in the Post-COVID Time,” 1–12.

32. Koens, Postma, and Papp, “Is Overtourism Overused?” 1–15.

33. Pechlaner, Innerhofer, and Erschbamer, Overtourism: Tourism Management and Solutions, 1–10.

34. De Luca et al., “Sustainable Cultural Heritage Planning and Management of Overtourism in Art Cities,” 1–11.

35. Inside Airbnb, “Florence.”

36. Ridolfi, “Tra Globale e Locale, Come Cambia Lo Spazio Urbano per Effetto Della Turistificazione Deregolamentata.”

37. Ridolfi.

38. Dastgerdi and De Luca, “Joining Historic Cities to the Global World,” 1–14.

39. Siena Free, “2019 Data on Tourism in the Municipality of Siena Published.”

40. Kokoshi, “Gentrification e Turistificazione. La Realtà Della Città Di Siena.”

41. Kokoshi.

42. Shah et al., “Guide to Understanding the 2019 Novel Coronavirus,” 646–652; and Tan et al., “A Novel Coronavirus Genome Identified in a Cluster of Pneumonia Cases,” 61–62.

43. Remuzzi and Remuzzi, “COVID-19 and Italy.”

44. Worldometer, “Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic.”

45. Ministero della Salute, “What Is a Novel Coronavirus?”

46. Del Buono et al., “The Italian Outbreak of COVID-19.”

47. Murgante et al., “Why Italy First?” 1–44.

48. Statista, “Estimated Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) on Tourist Arrivals in Selected Italian Cities in 2020.”

49. Beall, “COVID-19: Why Social Distancing Might Last for Some Time.”

50. Moghadam, “The Course of the Epidemic and Possible Scenarios.”

51. International Transport Forum, “Re-Spacing Our Cities For Resilience.”

52. See note above 34.

53. World Tourism Organization, “International Tourism Highlights, 2019 Edition.”

54. Tagliabue, Leonforte, and Compostella, “Renovation of an UNESCO Heritage Settlement in Southern Italy,” 1060–1068.

55. Borodovskaya and Gaiduk, “New Approach of Solving the Problem of Overtourism in Italy,” 517.

56. Cuccia, Guccio, and Rizzo, “The Effects of UNESCO World Heritage List Inscription on Tourism Destinations Performance in Italian Regions,” 494–508.

57. Italian Ministry of Health, “Containment Measures in Italy.”

58. Del Buono et al., “The Italian Outbreak of COVID-19,” 1116–1118.

59. Ripp and Rodwell, “The Geography of Urban Heritage,” 240–276.

60. Rodwell, “The Historic Urban Landscape and the Geography of Urban Heritage,” 180–206.

61. Guest, “Heritage and the Pandemic,” 4–18.

Bibliography

- Alderighi, M., and A. A. Gaggero. “Flight Availability and International Tourism Flows.” Annals of Tourism Research 79 (November 2019): 102642. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.11.009.

- Bandarin, F. World Heritage: Challenges for the Millennium. Paris, France.: UNESCO World Heritage Centre Paris, 2007.

- Beall, A. “COVID-19: Why Social Distancing Might Last for Some Time.” London, 2020.

- Bekele, F., D. Tolossa, and T. Woldeamanuel. “Local Institutions and Climate Change Adaptation: Appraising Dysfunctional and Functional Roles of Local Institutions from the Bilate Basin Agropastoral Livelihood Zone of Sidama, Southern Ethiopia.” Climate 8, no. 12 (December 15, 2020): 149. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8120149.

- Borodovskaya, A., and L. D. Gaiduk. “New Approach of Solving the Problem of Overtourism in Italy.” 2019.

- Buono, M., G. Del, G. Iannaccone, M. Camilli, R. Del Buono, and N. Aspromonte. “The Italian Outbreak of COVID-19: Conditions, Contributors, and Concerns.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 95 (April 2020): 1116–1118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.003.

- City Population. “Siena.” Accessed January 14, 2021. https://www.citypopulation.de/en/Italy/toscana/siena/052032__siena/

- Cuccia, T., C. Guccio, and I. Rizzo. “The Effects of UNESCO World Heritage List Inscription on Tourism Destinations Performance in Italian Regions.” Economic Modelling 53 (2016): 494–508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2015.10.049.

- Dastgerdi, A. S., and G. De Luca. “The Riddles of Historic Urban Quarters Inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List.” International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR 12, no. 1 (2018): 152–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v12i1.1315.

- Dastgerdi, A. S., and G. De Luca. “Boosting City Image for Creation of a Certain City Brand.” Geographica Pannonica 23, no. 1 (2019a): 23–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.5937/gp23-20141.

- Dastgerdi, A. S., and G. De Luca. “Strengthening the City’s Reputation in the Age of Cities: An Insight in the City Branding Theory.” City, Territory and Architecture 6, no. 1 (December 2019b): 2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-019-0101-4.

- Dastgerdi, A. S., and G. De Luca. “Joining Historic Cities to the Global World: Feasibility or Fantasy?” Sustainability 11, no. 9 (May 9, 2019c): 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092662.

- Dastgerdi, A. S., and G. De Luca. “Religious Differences and Radical Spatial Transformations in Historic Urban Landscape.” Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage (March 18, 2020): 191–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.6092/.1973-9494/10626.

- Dastgerdi, A. S., G. De Luca, and C. Francini. “Reforming Housing Policies for the Sustainability of Historic Cities in the Post-COVID Time: Insights from the Atlas World Heritage.” Sustainability 13, no. 1 (December 27, 2020): 174. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010174.

- Dastgerdi, A. S., F. Stimilli, C. Pisano, M. Sargolini, and G. De Luca. “Heritage Waste Management: A Possible Paradigm Shift in the Post-Earthquake Reconstruction in Central Italy.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 10, no. 1 (November 29, 2019): 76–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-07-2019-0087.

- Dawson, M. “Values in Heritage Management. Emerging Approaches and Research Directions: By Erica Avrami, Susan MacDonald, Randall Mason, David Myers, Los Angeles, Getty Conservation Institute, 2019.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 12, no. 2 (April 3, 2021a): 259–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2021.1927579.

- Dawson, M. “Valuing Heritage (Again).” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 12, no. 2 (April 3, 2021b): 117–119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2021.1923392.

- Dawson, T., J. Hambly, W. Lees, and S. Miller. “Proposed Policy Guidelines for Managing Heritage at Risk Based on Public Engagement and Communicating Climate Change.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice (August 12, 2021): , 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2021.1963573.

- De Luca, G., A. S. Dastgerdi, C. Francini, and G. Liberatore. “Sustainable Cultural Heritage Planning and Management of Overtourism in Art Cities: Lessons from Atlas World Heritage.” Sustainability 12, no. 9 (May 11, 2020): 3929. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093929.

- Di Giovine, M. A. The Heritage-Scape: UNESCO, World Heritage, and Tourism. United Kingdom: Lexington Books, 2008.

- Dodds, R., and R. Butler. “The Phenomena of Overtourism: A Review.” International Journal of Tourism Cities 5, no. 4 (December 9, 2019): 519–528. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-06-2019-0090.

- Francini, C. “The Management Plan of the Historic Centre of Florence.” Florence, 2016.

- Francini, C., and C. Bocchio. “Monitoring of the Management Plan of the Historic Centre of Florence.” Florence, 2018.

- Goodwin, H. “The Challenge of Overtourism.” Responsible Tourism Partnership, 2017.

- Guest, K. “Heritage and the Pandemic: An Early Response to the Restrictions of COVID-19 by the Heritage Sector in England.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 12, no. 1 (January 2 ,2021): 4–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2020.1864113.

- Gurran, N., and P. Phibbs. “When Tourists Move In: How Should Urban Planners Respond to Airbnb?” Journal of the American Planning Association 83, no. 1 (January 2, 2017): 80–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2016.1249011.

- Heritage Research Lab. “ATLAS WORLD HERITAGE - HERITAGE in the Atlantic Area Sustainability of the Urban WORLD Heritagesites - HERITAGE Research Lab at the University of Florence and Florence WORLD HERITAGE and UNESCO Relationship Office at the Municipality of Florence.” Florence, 2019.

- Inside Airbnb. “Florence.” 2019. http://insideairbnb.com/florence/

- International Transport Forum. “Re-Spacing Our Cities For Resilience.” 2020.

- Italian Ministry of Health. “Containment Measures in Italy.” 2020. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/home.html

- Joudifar, F., and Ö. O. Türker. “A ‘Reuse Projection Framework’ Based on Othello’s Citadel and Cultural Tourism.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 11, no. 2–3 (July 2, 2020): 202–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2020.1746876.

- Koens, K., A. Postma, and B. Papp. “Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context.” Sustainability 10, no. 12 (November 23, 2018): 4384. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124384.

- Kokoshi, J. “Gentrification E Turistificazione. La Realtà Della Città Di Siena. University of Florence. Degree Thesis in Pianificazione Della Città, Del Territorio E Del Paesaggio, Supervisor Prof. G. De Luca. Unversità Di Firenze.” University of Florence, 2020.

- Leadbeater, C. “Anti-Tourism Protesters in Barcelona Slash Tyres on Sightseeing Buses and Rental Bikes.” 2017. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/news/bus-attack-in-barcelona-adds-to-fears-as-tourism-protests-grow/

- Legnér, M., and G. Leijonhufvud. “A Legacy of Energy Saving: The Discussion on Heritage Values in the First Programme on Energy Efficiency in Buildings in Sweden, C. 1974–1984.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 10, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 40–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2018.1531646.

- Ministero della Salute. “What Is a Novel Coronavirus?” 2020. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/malattieInfettive/dettaglioFaqMalattieInfettive.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=230

- Mısırlısoy, D. “Towards Sustainable Adaptive Reuse of Traditional Marketplaces.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 12, no. 2 (April 3, 2021): 186–202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2020.1784671.

- Moghadam, A. “The Course of the Epidemic and Possible Scenarios.” 2020. https://www.bbc.com/persian/science-54892637

- Municipality of Florence. “Statistica Del Turismo.” 2019. http://www.cittametropolitana.fi.it/turismo/statistica-del-turismo/

- Murgante, B., G. Borruso, G. Balletto, P. Castiglia, and M. Dettori. “Why Italy First? Health, Geographical and Planning Aspects of the Covid-19 Outbreak.” Preprints (2020). doi:https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202005.0075.v1.

- Orr, S. A., J. Richards, and S. Fatorić. “Climate Change and Cultural Heritage: A Systematic Literature Review (2016–2020).” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice (July 29, 2021): 1–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2021.1957264.

- Pechlaner, H., E. Innerhofer, and G. Erschbamer. Overtourism: Tourism Management and Solutions. New York: Routledge, 2019.

- Pedersen, A. Managing Tourism at World Heritage Sites: A Practical Manual for World Heritage Site Managers. Paris: UNESCO, 2002.

- Remuzzi, A., and G. Remuzzi. “COVID-19 and Italy: What Next?” The Lancet 395, no. 10231 (April 2020): 1225–1228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9.

- Ridolfi, V. “Tra Globale e Locale, Come Cambia Lo Spazio Urbano per Effetto Della Turistificazione Deregolamentata. Il Caso Del Quartiere Oltrarno a Firenze, Degree Thesis in Pianificazione Della Città, Del Territorio e Del Paesaggio, Supervisor Prof. G. De Luca.” Unversità di Firenze, 2018.

- Ripp, M., and D. Rodwell. “The Geography of Urban Heritage.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 6, no. 3 (July 3, 2015): 240–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2015.1100362.

- Rodwell, D. “The Historic Urban Landscape and the Geography of Urban Heritage.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 9, no. 3–4 (October 2, 2018): 180–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2018.1517140.

- Shah, A., R. Kashyap, P. Tosh, P. Sampathkumar, and J. C. O’Horo. “Guide to Understanding the 2019 Novel Coronavirus.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 95 (2020): 646–652. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.02.003.

- Siena Free. “2019 Data on Tourism in the Municipality of Siena Published: Arrivals + 2%, Presences + 4%.” 2020. http://www.sienafree.it/turismo/319-turismo/116170-pubblicati-dati-su-turismo-nel-comune-di-siena-relativi-al-2019-arrivi-2-presenze-4

- Statista. “Estimated Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) on Tourist Arrivals in Selected Italian Cities in 2020.” 2021a. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1119718/impact-of-the-coronavirus-on-tourist-arrivals-in-selected-italian-cities/

- Statista. “Tourist Overnight Stays in Florence 2020.” Statista. Accessed October 1, 2021b. https://www.statista.com/statistics/722442/number-of-tourists-in-florence-Italy/

- Stucchi, L., D. F. Bignami, D. Bocchiola, D. Del Curto, A. Garzulino, and R. Rosso. “Assessment of Climate-Driven Flood Risk and Adaptation Supporting the Conservation Management Plan of a Heritage Site. The National Art Schools of Cuba.” Climate 9, no. 2 (January 23, 2021): 23. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cli9020023.

- Tagliabue, L. C., F. Leonforte, and J. Compostella. “Renovation of an UNESCO Heritage Settlement in Southern Italy: ASHP and BIPV for a ‘Spread Hotel’ Project.” Energy Procedia 30 (2012): 1060–1068. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2012.11.119.

- Tan, W. J. Z. X., X. Zhao, X. Ma, W. Wang, P. Niu, W. Xu, G. F. Gao, and G. Z. Wu. “A Novel Coronavirus Genome Identified in A Cluster of Pneumonia Cases—Wuhan, China 2019-2020.” China CDC Weekly 2, no. 4 (2020): 61–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2020.017.

- Tuscany Tourist Board. “Tuscany Regional Survey.” Florence. Accessed December 28, 2020. http://www.toscanapromozione.it/uploads/documenti/TuscanyRegionalSurveyGent.pdf

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Historic Centre of Siena.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed October 1, 2021. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/717/

- World Heritage Centre. “Historic Centre of Florence.” Accessed April 25, 2020. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/174/

- World Heritage Committee. “Adoption of Retrospective Statements of Outstanding Universal Value, 38 COM 8E.” Paris, 2014.

- World Tourism Organization. UNWTO Tourism Highlights: 2017 Edition. 2017 Editi ed. Madrid: World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284419029.

- World Tourism Organization. “International Tourism Highlights, 2019 Edition.” 2019. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284421152

- World Tourism Organization. “International Tourism Growth Continues to Outpace the Global Economy.” 2020. https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-growth-continues-to-outpace-the-economy

- Worldometer. “COVID-19 CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC.” 2021. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/