Abstract

This paper reports on a research project aimed at investigating ways in which fashion activism and making can be used to catalyze positive socio-economic change and activate legacies within a local community. The project focused on a neighborhood in London with a previously strong industrial profile in fashion and textiles, and now challenged by concerns regarding deprived youth, skills shortage, decline in local manufacturing, and high unemployment rates. To tackle such challenges, this participatory action research project comprised a range of fashion activism interventions. The project was developed through a partnership between a Higher Education Institution and local government and contributed to activating change from within the system. The approach adopted is defined as “middle-up-down” as it bridges bottom-up initiatives activated by grassroots communities with top-down services delivered by support organizations. The outcomes of the project are discussed in relation to the key themes emerging from the project evaluation: sustainability awareness, empowerment and skills development, career pathways, and community engagement. In demonstrating how a “quiet” form of activism can be used as an embedded and situated approach to co-designing meaningful social innovations within the local community, the paper also outlines the limitations of the project and recommendations for future work.

Introduction

This paper reports on a research project developed in partnership between a Higher Education Institution (HEI) – London College of Fashion, UAL – and a local government department – London Borough of Waltham Forest – as part of a major initiative aimed at supporting the delivery of arts and cultural events. Adopting a design activist approach, the project team engaged, through fashion and making, with schools, businesses, and local residents to develop and retain creative talent in the borough and address issues affecting the community, such as deprived youth, skills shortage, and high unemployment rates.

The project focused on Waltham Forest, a North-East London borough, which is ethnically diverse. In fact, 68% of the total population is from black, Asian and minority ethnic groups (BAME), and the diverse social fabric of the borough is a result of many residents being born outside the UK, primarily from Pakistan, Poland, Romania, Jamaica and India (London Borough of Waltham Forest Citation2017). Although income in Waltham Forest is lower than the London average and inequality is evident in employment and pay across BAME groups, we are witnessing a sharply growing rate of new businesses and of self-employment; the number of new businesses and start-ups increased by around 47% in recent years (A New Direction Citation2019). In 2015 Waltham Forest was ranked 35th in England for multiple deprivation out of 326 local authorities (London Borough of Waltham Forest Citation2020). Several neighborhoods in Waltham Forest are in the top 10% of the most deprived in England, with significant economic divisions within the ward (William Morris Big Local Plan Citation2010). Waltham Forest has a population slightly younger than average, with 33% of residents aged 0–24 years as compared to 31% in London overall. This allows for initiatives and developments to engage with the potential young talent pool.

Heritage craftsmanship has underpinned the local fashion and textile industry since the 14th century and drives grassroots making initiatives in Waltham Forest and East London; this shows signs of revival of fashion manufacturing, reversing a trend of decades of decline (BOP Consulting Citation2017). Within the borough is located the William Morris Gallery, a museum dedicated to the life and works of William Morris, a world-renowned designer and early socialist from the 19th century who was a major contributor to the British Arts and Crafts movement. Besides well-established design businesses and start-ups, there is also a growing number of creative initiatives led by local residents, revealing more untapped talent which needs surfacing (A New Direction Citation2019). In East London, fashion contributes £1.4 billion to London’s economy, employs more than 36,000 people working in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) focused on advertising, retail, design, manufacturing and distribution, and the industry is growing faster than in the rest of the capital (Harris et al. Citation2021). These fashion businesses comprise of clothing retail or fabric merchants () followed by designers, manufacturers, and specialized crafts such as embroidery, beadwork, and leatherwork (A New Direction Citation2019). Furthermore, Walthamstow is in the top 8% of all UK Parliamentary Constituencies when it comes to the number of people employed in the fashion industry.

The challenges for the local fashion industry to grow are highlighted by a study conducted by non-profit organization A New Direction (Citation2019) and which provides the evidence base for a local partnership plan setting the vision for making Waltham Forest a place where fashion businesses and people thrive. The creative workforce can be seen as unrepresentative of the diversity of the local area; there is an absence of visible opportunities for the Asian community and the many people with a background in textiles wanting to return to work. Amongst young people, there is a growing consciousness of waste and ethical considerations in fashion. The local community adopts a “make do and mend” or “reduce, reuse and recycle” approach to sustainability which is primarily driven by economic necessity and only secondarily by environmental, social, and cultural concerns (A New Direction Citation2019). There is a lack of connectivity across the local fashion industry which is made up of small businesses and discrete initiatives, leaving the makers and manufacturers feeling isolated. This highlights the need for a supportive infrastructure to nurture collaborations between designers and makers. A growing attraction to fast fashion over craftsmanship has led to the disappearance of specialist technical skills and shortage of skilled workforce. There is a need to retain and protect the remaining existing skilled workforce and to upskill new potential employees to maintain the rich cultural fabric of the borough.

Within this context, a participatory action research project was initiated with the aim to investigate ways in which fashion activism and making can be used to catalyze positive socio-economic change and activate legacies within the local community. To achieve this aim, collaborative making activities were conducted, engaging members of the local community to nurture their social agency and a culture of fellowship, whilst also demonstrating ways in which fashion can contribute to shaping better lives. To this end, cross-sector collaborations were activated and a long-term partnership between London College of Fashion, UAL (LCF) and London Borough of Waltham Forest (LBWF) was established around aligned strategic objectives and shared plans towards activating positive socio-economic change and creating tangible legacies within the borough with the aim to make it a better place to live and work.

Literature Review

Within this research context, design activism was deemed as a suitable approach to activate change in the local fashion industry towards sustainability. Design activism can be defined as “design thinking, imagination and practice applied knowingly or unknowingly to create a counter-narrative aimed at generating and balancing positive social, institutional, environmental and/or economic change” (Fuad-Luke Citation2009, 27). Adopting a design activist approach in this context meant becoming “agents of appropriate change” or “catalysts for systematic transformation” (Banerjee Citation2008). This implies going beyond the well-recognized role of the designer facilitator (supporting on-going initiatives) and expanding the role of the designer to become an activist (aimed at making things happen) to contribute to social innovation and sustainability (Manzini Citation2014). Fuad-Luke (Citation2017) argues that design activism creates alternatives that challenge existing power structures and links marginalized communities with those in power. Moreover, adopting a design anthropological approach, Pink (Citation2015) links “slow activism” with co-design to enable resilient futures, and Turnstall (Citation2018) argues for the need to go beyond t-shirts, badges, and others forms of activist messaging, and instead focus on the values systems that are foundational of community organizing.

In this project, fashion was the medium engaged with for a specific form of design activism. “Fashion activism” is an emerging approach, adopted by an increasing number of designers in several projects. Fashion activism can imply individual or collective action and be embraced by social movements; in fact, activists generally do not take action just for their own benefit but are mostly driven by values of solidarity and by an ambition to bring about social change. Being a fashion activist implies challenging the designer’s ego and listening to people’s needs so that the most effective action can emerge from within communities. Fashion activism manifests itself both in consumers wearing clothes to express their own values and in the values-led actions taken by fashion designers and brands to fight for social justice, environmental stewardship, economic prosperity and cultural regeneration (Burns Citation2019). Historically, activists and social movements have been successful in countering the negative impacts of fashion, including the logics of speed and growth on which the capitalistic fashion system has been grounded. In recent times, movements like Fashion Revolution and XR Fashion Action have gained currency and recognition in activating positive social change within the fashion industry. Bruggeman (Citation2018) advocates for the need to envision a more meaningful, inclusive, and resilient future of fashion that does more justice to society, by redefining the value systems by which we live and work and reconsidering how we engage with each other and with the material resources of the earth.

Many fashion activists are creating garments that are part of solutions to larger societal, economic, health and political problems (Friedman Citation2016). Sarah Corbett (Citation2017) highlights that not only extroverts but also introverts can be activists, engaging in craft activities in everyday life to bring about social change. In line with the recently revived interest in Do-It-Yourself (DIY) craft culture, Fiona Hackney (Citation2013) argues for the emergence of a new, historically conscious, socially engaged amateur practice as a form of “quiet activism” that gives people agency and fosters social relations. Otto Von Busch (Citation2008) is concerned with civic engagement and the empowerment of “fashion-abilities”. Fashion activism can also be linked to DIY to create person-product attachment and with participatory design processes to open up opportunities for change of attitudes and behaviors towards clothing (Hirscher and Niinimäki Citation2013). In her work, Hirscher (Citation2013; Citation2020) conducts participatory workshops using “half-way” products to facilitate a process of co-designing and making clothes; this results in consumers developing new skills and becoming “prosumers” (i.e. producers and users) of their own garments. For instance, in Italy, the “Make Yourself…” project led by the “Mode Uncut” network activated a process of social making of clothes in a “makershop” (i.e. a combination of a makerspace and pop-up shop), bringing together “diverse locals” to generate different clothing concepts and bringing about diverse types of value for local fashion production (Hirscher, Mazzarella, and Fuad-Luke Citation2019). In New Zealand, Jennifer Whitty and Holly McQuillan initiated “The Wardrobe Hack”, an individual and modifiable set of self-determined actions, inactions, tasks and exercises designed to deliver power into the hands, minds and bodies of all users of fashion. Several projects led by researchers at Centre for Sustainable Fashion, UAL (CSF) have adopted a fashion activism approach, as discussed by Mazzarella, Storey, and Williams (Citation2019). For instance, in “I Stood Up”, Dilys Williams (Citation2018) created the conditions for a series of garment making and wearing taking place over time with diverse participants, including first time voters and members of the UK Parliament realizing visual representations of issues of public concern. The “CUT” project led by Francesco Mazzarella leverages the power of fashion activism, co-creation, and storytelling to shift the prevailing narrative around youth violence and provides educational and employment opportunities for young people in fashion (Mazzarella and Schuster Citation2021). The “Fashion Ecologies” project by Kate Fletcher (Citation2018) approaches fashion activism and sustainability through the lens of localism, as a way of engaging people with fashion in alternative ways, giving them power and responsibility towards the things that affect their lives. The above-mentioned projects, to varying degrees, embrace a collective voice, and are based on actions of standing up and speaking truth to power; although they can be considered as micro-sites of activism, they contribute to fostering macro-changes in society and people’s perception of the fashion system.

Within this research context, it is also important to highlight that an infrastructure is needed to sustain community-led activist interventions and make them sustainable over time. In this regard, we are witnessing a trend in which Universities are increasingly playing a key role in driving social innovations within the local urban contexts in which they are based (Fassi et al. Citation2019). For example, LCF has established the “Better Lives” agenda, which means using fashion to drive change, build a sustainable future, and improve the way we live. In particular, the Social Responsibility team at LCF has extensive experience in working with women in prison to aid their rehabilitative journeys, by giving them professional skills and qualifications in fashion and textiles and supporting them upon release. Furthermore, in light of its upcoming move to East London, the College has developed a program of public and community engagement activities, driving transformation, regeneration and innovation in the local area. This is opening up strategic opportunities and connections with organizations and communities across East London to take place ahead of the College’s move, rather than “parachuting” into a new area without any engagement with or relevance for the local community.

Methodology

The research project discussed in this paper comprised a range of fashion activism and community engagement initiatives. The project involved an in-depth investigation of qualitative data collected from purposively selected groups of people participating in the research. In line with Kemmis and McTaggart (Citation2003), Participatory Action Research (PAR) was chosen as a methodology driving the project as it involves in situ collection of socially and culturally rich data and links theory to practice. A collaboration between the researcher and participants was activated to explore socio-economic issues within a specific research context and enable the development of interventions, innovations, or practices to address the very same issues.

Based on these premises, the project was developed in two phases:

The first phase was a residency undertaken by the first author of this paper at Waltham Forest Town Hall with the aim of identifying a suitable scope for the project, detailing its outputs and expected outcomes, as well as defining the project timeline and budget. In order to do this, ethnographic methods (i.e. participant observations and unstructured interviews) were adopted in consultation with people from diverse departments within the local council (Culture, Education, Business Growth, and Regeneration), and partnerships with local organizations (schools, fashion manufacturing businesses, social enterprises) were established to deliver the project. Following Malinowski (Citation1987), ethnography took place through the researcher’s immersion in the context to observe people in their natural environment for an extended period and discover the perspectives of local community members. Throughout the ethnographic investigation, field notes were written to capture the researcher’s comments, and insights were gathered from the interaction with the participants, paying a great deal of attention also to contextual elements.

The submission and review of a detailed project proposal were followed by the second and main phase of the project, funded by different departments within the local council (i.e. the Great Place scheme, Business Growth, Regeneration, and Culture). This consisted of a range of PAR interventions with local schools, manufacturing businesses and community members. Given the word limitations of this paper, we will focus only on the community engagement activities undertaken through this project.

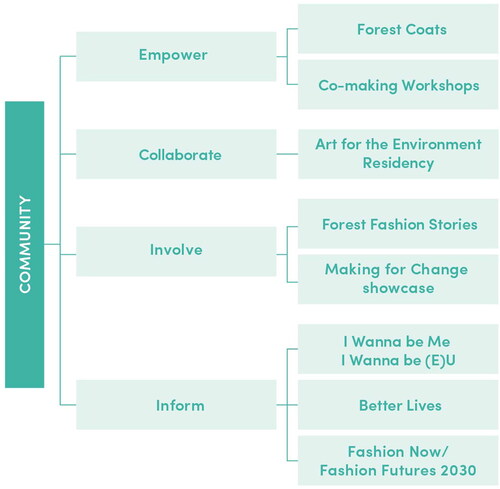

Multiple data collection methods were adopted throughout the project to address the research aim and objectives, as summarized in . The activities varied in length and level of engagement with community members. For instance, “I Wanna be me, I Wanna be (E)U” was a performance taking place in one day but anticipated by three days of workshops for LCF students to design and make a fashion collection. “Forest Fashion Stories” was a drop-in workshop delivered over a weekend, following two months of planning and production. The “Better Lives” symposia were two evening events delivered after two months needed for planning and promotion. The co-making workshops were a series of six events delivered over a period of three months, following one month of organization and communication. “Forest Coats” was an eight-week-long workshop series, which required two months of planning, communication, and participant recruitment. The “Art for the Environment Residency” entailed the setting up of a brief, selection of an artist who responded to the call out, and then conducted a month-long community engagement workshop culminating in a week-long project showcase. The exhibitions “Fashion Now/Fashion Futures 2030” and “Making for Change: Waltham Forest” were open to the public for three weeks each, but required three to four months for curation, production, and promotion.

Table 1. Multiple data collection methods adopted throughout the project.

provides a breakdown of the 1160 participants (including members of the public) who engaged in the activities delivered throughout the project. The number of participants and their level of engagement varied significantly between the different activities. Six-hundred people (mostly local residents) participated in the drop-in workshops delivered as part of the “Forest Fashion Stories”, contributing their ideas and thoughts over a short period of time. Over one-hundred people visited each of the two exhibitions, interacting with the showcased content for a period varying from ten to thirty minutes approximately. “Forest Coats” was the activity with the lowest number of participants (i.e. eighteen), but this is because this workshop series was targeted only to a particular group of women who actively engaged with the design and making of garments over a long period (i.e. eight weeks), collaborating in depth with the project team.

Table 2. Number of participants in the diverse community engagement activities of the project.

Data analysis

Over the course of the project, large amounts of qualitative data were collected, in a range of formats, such as field notes, post-it notes, audio recordings, and photographs. The data was thematically analyzed by the first author of this paper, through a manual and iterative process, to synthesize data in relation to codes, make comparisons between identified themes and draw conclusions from the findings (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). ATLAS.ti software was used for manual coding, so that raw data (such as audio transcripts, research reports, feedback questionnaires, and online survey responses collected through the project activities) were imported for analysis. In the thematic analysis, codes emerged from the data through an inductive process (Sadler Citation1981) following the impact evaluation framework developed by the National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO Citation2018). Frequently recurring codes were clustered into themes, and software-generated word clouds were used to validate the themes. As a result of the impact evaluation process, the outputs (i.e. the goods, services or products being delivered) and outcomes (i.e. single, measurable changes) produced were outlined for each step of the PAR.

Results

This section reports on the results of the community engagement activities undertaken throughout the project. Local residents participated in a number of collaborative activities, through which they developed making skills, gained social agency and contributed to fashion sustainability. Adopting the Spectrum for Public Participation developed by the International Association of Public Participation (IAP22 Citation2014) as a framework, the different activities were classified into various levels of community engagement (). The lowest level includes activities whose purpose was merely to inform audiences or visitors; the subsequent level aimed at involving community members in some of the project activities; the next level was based on active collaboration; the highest level of community engagement led to achieving empowerment.

Fashion activism for awareness raising

The fashion activist interventions in the lowest level of community engagement aimed at raising people’s awareness of sustainability issues in the fashion industry.

An exhibition on fashion’s present and future relationship with nature

The “Fashion Now/Fashion Futures 2030” exhibition drew from work initially developed by CSF for the “Fashioned from Nature” exhibition at the V&A Museum, and brought it to the gallery space of a newly established fashion hub (“Arbeit Studios Leyton Green”), with the aim of raising local people’s understanding of how every element of fashion comes from nature.

By examining five contemporary fashion items (i.e. a pair of shoes, a t-shirt, a pair of jeans, a dress, and a bag), the “Fashion Now” installation showed how we relate to nature across a five-stage fashion lifecycle, from design to make, acquire, and wear through to discard. The installation, based on familiar elements of the fashion world (such as Instagram, purchase receipts, illustration, and video), showed that our interaction with these items frequently reveals an unequal partnership between fashion and nature. For the visitors, therefore, the installation raised questions around ways to develop a healthier relationship with nature in our fashion choices. Moreover, the “Fashion Futures 2030” installation explored what fashion and nature might look like within four future scenarios, based on environmental, economic, social, cultural, and technological changes taking place across the world. The fashion future scenarios (named “Living with Less”, “Hyper Hype”, “Safety Race”, and “Chaos Embrace”) were developed through research by CSF, with contributions from Forum for the Future, and were conceived not as predictions, but as stories of how the future might unfold. The visitors were encouraged to answer an online survey to envisage the effects their fashion habits would have on the environment and find out which of the four scenarios would be the most suitable to them. As stated in an online survey by one visitor, “the exhibition highlighted the responsibility we all have towards building a more responsible fashion industry, either as consumers or as practitioners”.

Two symposia on fashion activism education and legacies

The two “Better Lives” symposia constituted another element of the project aimed at awareness raising. The first event was focused on the theme of “education” and aimed at discussing work undertaken by LCF in educating the next generation of fashion designers, communicators, and entrepreneurs. Alongside a panel debate, a pop-up exhibition was curated as an opportunity to showcase students’ projects and demonstrate their contribution to shaping better lives. Responding to briefs set up by industry partners, the students were guided through a process of thinking and making together, working in teams, and collaborating with the local community. As a result, they developed fashion activist interventions, which took a variety of formats, such as a fanzine (showcasing alternative clothing practices and celebrating the network of craftspeople and small-scale businesses that are vital for Waltham Forest’s fashion ecosystem), a jacket (with fabric insertions embedding messages written by school pupils during a series of creative workshops exploring a range of sustainability issues within the fashion industry) and a report (outlining the vision for a closed loop system for pre-consumer textile waste whilst also creating pathways for collaboration and skill sharing among local fashion designers and makers). The second symposium – which took place towards the end of the project – was aimed at discussing the impacts and legacies activated through the research beyond its timeframe and funding. The symposium evidenced the role of the fashion activist catalyzing local community engagement, the values driving the project, the skills developed through design and making activities, as well as the challenges and opportunities for fashion activist interventions like these to build long-lasting legacies in terms of sustainability and social innovation. Amongst such legacies, the symposium evidenced the importance of strategic collaborations activated with local schools, the vision for an innovative Wash Lab to be established in East London offering sustainable laundering and finishing techniques for denim, and the multiple education and career progression routes which were paved through the project. Based on feedback collected through online surveys from the attendees, both symposia contributed to raising people’s awareness of the project, amplifying their understanding of sustainability, including diverse – especially social – approaches to the topic, and demonstrating fashion’s contribution to shaping better lives. Some people highlighted that participation in the symposia contributed to feeding their hope towards sustainability, making them feel empowered, inspiring creative ideas, and gaining valuable contacts for potential collaborations. For instance, one attendee stated: “I found out about a project that I had very little prior knowledge of, although it was within my creative field” and for another participant, the main take-away from one of the symposia was “the diversity of the concept of sustainability in fashion”.

A performance on the impacts of Brexit on the fashion industry

“I Wanna be me, I Wanna be (E)U” was an interactive live art performance, inspired by catwalk shows, aimed at exploring and expressing issues of fast fashion, global trade, waste, and the socio-economic impacts of Brexit (the UK leaving the European Union) on the fashion industry (). Through three days of making workshops, four LCF students upcycled pre-consumer waste fabrics into a fashion collection. Consisting of ten different styles – all in the colors of the European flag, blue and yellow – the collection was embedded with messages taken from a protest against Brexit, which took place in the streets of London in March 2019. Five styles were conceived to represent the workers of the fashion industry, who were wearing blue aprons with statements related to Brexit. The other five outfits were more eccentric, to represent the luxurious over-consumers of fashion. “I Wanna be me, I Wanna be (E)U” was the first project activity to be delivered. The catwalk show was performed by non-models in an abandoned supermarket (later to become a fashion hub), still equipped with empty shelves and check-out tills, as an apocalyptic space to let the audience contemplate a post-Brexit scenario in which goods may no longer be easily accessible. The models/performers engaged with the audience by giving away some messages created by LCF students using the cut-up technique, rearranging and collaging newspapers articles to create new texts as provocations to reflect on the socio-economic implications of Brexit on the fashion industry. The performance was followed by a panel debate between an academic, an artist, a fashion manufacturer, and a representative of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Textiles and Fashion. Overall, the event shone a light on fashion’s activist and environmentalist agenda within a Brexit context, and proved to be an inspiring way to get an overview of a highly complex and broad-ranging set of issues. In fact, Brexit poses a real concern for UK fashion employers as it limits access to markets and movement of skilled workers coming from European Union countries. Nevertheless, Brexit was also deemed by some participants as an emergency, a forced opportunity to envision a micro, local utopia, a new vision for a better world based on new synergies across a diversity of local stakeholders and new lifestyles and innovation processes that could lead to wellbeing, as stated by one panelist:

“Until now, the fashion world has seemed to be about what we wear and consume. More importantly, it is also about humans celebrating being alive in each present moment. For this idea to continue, we need to lift our heads upwards and to imagine worlds beyond the runway. The obsession with maximizing profits at the point of sale is a strategy that is long past its sell-by date”.

Fashion activism for citizens’ involvement

This section reports on an interactive exhibition and a series of drop-in workshops involving community members to express their engagement with fashion, especially in their local area.

An exhibition engaging the community in experiencing the outcomes of the project

To conclude the year-long project, the “Making for Change: Waltham Forest” exhibition was aimed at providing an opportunity for visitors to experience the outcomes of all the project’s activities and understanding fashion’s contribution to activating positive change in the borough (). A key curatorial aim was to create an accessible and inclusive space for a variety of audiences, from the local community to academics and industry professionals. The projects represented in the showcase were grouped in three thematic areas (i.e. “Education”, “Manufacturing”, and “Community”). Within each area, the projects were communicated through a multitude of media to show three key elements: the artefact, the story, and portraits of the makers. In particular, the “Education” section manifested as an interactive table on which five teaching resources (i.e. the “Activating Change” Collaborative Unit brief, “A Store of the Future” Innovation Challenge pack, the “Fashion Futures 2030” toolkit, the “Fashion Club” workshop series, and the “Fashion London” curriculum) were showcased either through print or digital media. The work presented in the “Manufacturing” section included craft tools, fabric samples, finished garments, an interactive installation engaging the visitors to comment on a range of policy recommendations for sustainable fabric manufacturing, and three short films documenting the residencies undertaken by LCF researchers hosted by local fashion and textiles businesses. The “Community” section showcased the outputs (e.g. paper-based designs, fabric samples, upcycled garments, and an art installation) of a number of participatory making activities which involved local community members. Further enhancing the inclusivity of the exhibition was the “feedback board” asking the question: how can fashion and making activate positive change in your community? Visitors were invited to leave comments and suggestions on the board, as per this quote: “The project contributed to instilling pride and innovation into our community and amplifying capacities and confidence of those who may otherwise be overlooked”. From the start of the curation of the showcase, sustainability was a priority. The furniture of the exhibition was designed and produced – through laser cutting – using DufayLife (100% recycled cardboard); at the end of the exhibition, 70% of the furniture was gifted to tenants of Arbeit Studios Leyton Green for re-use, and some of the project participants collected the signage and photos to replicate elements of the installation in their own spaces. Based on feedback collected from the visitors through an online survey, the exhibition was effective in showcasing the outcomes of the project to local residents, triggering their creativity and encouraging them to carry on similar projects and start new ones, such as collective craft workshops in the communal area of Arbeit Studios Leyton Green. It also demonstrated to the fashion community the crucial role of fashion activism and showcased how it can be used to create positive social change.

Community workshops demonstrating fashion as a social act

The activities delivered as part of “Forest Fashion Stories” were aimed at encouraging the sharing of ideas across age groups, communities, and cultures, and demonstrating fashion’s role in our personal, social and cultural lives.

Over six-hundred people (mostly local children with their parents) participated in the drop-in workshops delivered as “Forest Fashion Stories” at the Walthamstow Garden Party (). Participants were given t-shirt paper templates as well as coloring and collaging materials and created over 250 slogan t-shirt designs communicating different messages that are important to them as individuals and in relationship to the environment we live in. Many children enjoyed being photographed proudly showing the t-shirts they had designed as unique ways to express what fashion means to them (e.g. “Be Yourself”, “Dare to be Different”, “Pride”) and environmental issues they care about (e.g. “Save the Ocean”, “Love Animals”, “Buy Second-hand Clothes”). A few participants kept their t-shirt designs, whilst most of the designs were added to a washing line display which grew throughout the two days of the Garden Party. Visitors to the event were also asked to write down their answers to questions in relation to their relationship with fashion, and what they think the fashion hotspots in their local area are. Although some participants at first did not feel very creative, in the end they all found their own way to express themselves and kept engaged in the making activities, as stated by one participant: “This workshop is brilliant. It is just a simple activity, but it makes you think a lot”.

Fashion activism for citizens’ collaboration

This section reports on the fashion activist’s role to trigger collaboration with community members to express their cultural identity and diversity, through garments.

An artist in residence collaborating with community members to celebrate their cultural identity and diversity

The “Art for the Environment Residency” (AER) was conducted as an extended making workshop aimed at testing – at a micro, local scale – a new system of creative education. Selected for the AER program, a UAL graduate employed community outreach and arts education to encourage members from the Waltham Forest community to repurpose existing objects into artworks that address identity issues. The artist encouraged the participants to undertake research alongside her, collecting garments that are significant to their identities and styling them to create new artworks. As an output of the residency, an exhibition was curated to showcase the work produced to celebrate the cultural identity and diversity within Waltham Forest. The artist in residence addressed two of her identity strata – her Jewish heritage and her manufactured digital persona – and visualized them against two future scenarios (). Using multiple media (i.e. film, photogrammetry, bioplastic materials, second-hand mannequins, and her own clothes), the artist acknowledged the differences and inherent separateness in possible future realities the two personas may soon face. Two of the community participants deeply engaged in collaboration with the artist to develop artworks that were highly personal, as highlighted by the artist in residence in the project evaluation questionnaire: “Working with them made me think about what kinds of bodies we design clothes for, and what kinds of needs and support for project development a community like Leyton might have”.

Fashion activism for citizens’ empowerment

The fashion activist interventions in the highest level of community engagement aimed at empowering people through gaining self-confidence, developing skills, and connecting with fellow community members.

Co-making workshops to learn craft skills

A series of six co-making workshops were facilitated by three LCF graduates at the social enterprise Forest Recycling Project (FRP) with the aim to provide community members with the opportunity to learn making skills and contribute to fashion sustainability (). At the first workshop, participants brought garments that they had at home and that needed mending, and explored different methods of repair, from embroidery to upcycling. One participant stated: “I have learnt to darn something, and now I can finally wear my favorite trousers again”. At the second workshop, using different types of food waste (from avocados to onions), members of the local community came together to create naturally dyed fabrics. The third event was a zero-waste pattern cutting workshop which encouraged participants to work hands-on on fabrics and eliminate waste when producing garments. By participating in the workshops, a total of forty-four local residents developed making skills as a way to enhance their social agency and their contribution to fashion sustainability. The workshops highlighted the positive impact of craft on people’s wellbeing, especially due to the pleasure of making things by hand, the satisfaction of achieving something, and the joy of making things together with others. Furthermore, each ticket sold paid for another workshop that was then delivered to a group of marginalized volunteers referred by a charity partner. The volunteers would have not had the opportunity to enjoy the same experience as paying customers otherwise.

An upcycling programme to build communities and inspire social change

Amongst all the project’s activities, the one which contributed the most to real empowerment was “Forest Coats”, which used fashion and making with the aim of building communities and inspiring social change. Part of a wider initiative led by the Social Responsibility team at LCF, “Forest Coats” was an eight-week program for eighteen women (with low levels of sewing skills) to learn how to upcycle pre-consumer waste fabrics into children’s jackets which were made either for their own children or for donation to the local community (). The program was led by a relatively high number of teaching staff per participant (1:3) and sessions were taught using hand-stitching and domestic sewing machines, ensuring that all skills learnt could be replicated by the women at home. Through the program, eighteen children’s jackets were produced and customized through beadwork or messages embroidered inside the pockets. These were worn by children at a fashion show to celebrate the successful outcomes of the project. “Forest Coats” was successful as it effectively used locally available assets: pre-consumer waste fabrics sourced from a local social enterprise, a simple pattern created by a local designer (leaving room for customization), and the assistance of a local maker. The program created a safe space for local women to come together, build self-confidence through learning new skills and feel less isolated and more connected with fellow community members, as stated by one participant in the project evaluation questionnaire: “The project has given me the confidence to think about the future. Stress really affects my health very badly, so engaging in a laid back, but exciting project has been perfect for me”. “Forest Coats” also led to unexpected outcomes: three women (from less advantaged backgrounds) participating in the project gained employment, and this, in turn, had a positive impact on their self-confidence and their ability to pave their own futures. Another woman became not only a participant in the project, but played the role of an assistant tutor, helping others during the sessions. Building on the learning from this experience, one LCF graduate who led the delivery of the program, has changed her business model – initially registered as a limited company – to a community interest company, so that she can continue delivering workshops for marginalized women referred by the local council. Building on the success of this project, other iterations of “Forest Coats” were organized, and to assist in the delivery of the workshops, one woman who had participated in the project was hired to train the new participants in the skills she had previously gained. The choice of the tutors was strategically made to provide employment opportunities to local residents and ensure long-lasting engagement with the community for the delivery of the project. Furthermore, multi-media instructions (using text, visuals, and video) were produced as a tangible legacy from the project, ensuring that the women can become independent in making their own garments beyond the timeframe of the project.

Outcomes

The process of thematic analysis of the data collected enabled the outcomes of the project to emerge. These were clustered into four key themes (i.e. sustainability awareness, empowerment and skills development, career pathways, and community engagement) which are explained in the following sections.

Sustainability awareness

The local community increased its awareness of the contribution of fashion activism towards sustainability and social innovation. Data revealed that the participants gained a better understanding of how they could approach fashion in more sustainable ways, within their borough. In particular, “I Wanna be me, I Wanna be (E)U” demonstrated fashion’s activist and environmentalist agenda within a Brexit context, and the “Better Lives” symposia highlighted how fashion can contribute to shaping better lives. Community members participating in the “Art for the Environment Residency” gained experience in using fashion to express their personal identity and cultural diversity within the context of climate emergency.

Empowerment and skills development

Through a series of co-making workshops and the “Forest Coats” program, members of the local community gained skills in creative repair, natural dying, zero-waste pattern cutting, embroidery, and garment construction. Having built capabilities, people felt empowered, more hopeful and this, in turn, enhanced their self-confidence. For instance, two women, after participating in “Forest Coats”, have bought domestic sewing machines for themselves, and are practicing and refining their skills at home. The journey of empowerment was particularly evident in one young lady who improved her skills and confidence exponentially within just a few months through engagement in the project’s activities. In fact, she first attended the co-making workshops delivered by the project team, she then facilitated her own workshop within the familiar environment of the social enterprise FRP, and was subsequently hired to deliver workshops with hundreds of people at a local public event. Finally, she created and showcased her own artwork as part of the “Art for the Environment Residency”.

Career pathways

Three women (from less advantaged backgrounds) participating in the “Forest Coats” program gained employment: two as LCF technicians, and one was hired by a local sustainable fashion brand. This achievement had significant implications for them to gain self-confidence and pave their own futures. The project also provided University graduates with an additional source of income for the delivery of workshops, exhibition invigilation, photoshoots, and other activities. One LCF graduate, who established her sustainable fashion brand in one of the studios in Leyton Green, embedded her life in Waltham Forest’s community and is contributing to the commercial sector of the borough. Furthermore, building on the learning from the “Forest Coats” project, she decided to switch her business model into that of a community interest company, making long-term plans to continue delivering creative workshops for less advantaged people.

Community engagement

Based on feedback received, the project participants gained social agency and became more connected with fellow community members; some people also expressed that they felt less isolated upon participation in the project’s activities. “Forest Coats” offered a safe space away from everyday life challenges for the women to engage in making activities; as a result, they were able to reduce their negative emotions and increase their wellbeing. Participation in a number of exhibitions and symposia has meant that the local community was able to engage with the work of LCF staff and students prior to the opening of a new campus in East London. Furthermore, the community expressed willingness in getting involved in future projects. Finally, it was motivational and empowering for the participants to see their work showcased as part of the final project exhibition in their local community.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper discussed a participatory action research project which explored ways in which fashion activism can be used to listen and respond to locally experienced issues and trigger participation across a wide range of public and institutional organizations. The project presented in this paper exemplifies a fashion activism approach adopted to engage with communities in a range of collaborative making activities aimed at developing and retaining creative talent in the borough and addressing locally experienced issues, such as deprived youth, skills shortage, fashion manufacturing decline, and high unemployment rates.

When designing for social change, it is imperative to ensure that investments and interventions lead to real empowerment and building capabilities so that communities become self-sustainable and resilient and not merely reliant on the design activist leading the project. With this in mind, the ambition behind the project was to contribute to activating long-term legacies within the local community, beyond the funding and timeframe of the research. In this project, social change could have been activated from within or outside the system. A more disruptive approach could have been adopted, for instance through formalized campaigning, such as in the work of Fashion Revolution or XR Fashion Action; however, this would have been likely unsuccessful in this context, given that the project was funded by a local council. Hence, a “quiet” form of activism was adopted, as an embedded and situated approach to co-designing meaningful social innovations within the local community. Adopting fashion as the medium for a specific form of design activism, the first author of this paper acted as a catalyst for residents to think and do things differently, being an outsider to the local community, whilst at the same time having insider know-how as he was a former resident of Waltham Forest. To enable the project to be conducted from an insider’s point of view, with first-hand understanding of the participants’ day-to-day realities and their diverse social worlds, it was crucial to establish inclusive relationships with the local community members and gather rich insights and direct knowledge of their experiences. This dual position of outsider/insider had perhaps a beneficial effect in activating positive change within the borough. Moreover, within the wide range of approaches to fashion activism, a “middle-up-down” approach was preferred in this project; this means that bottom-up initiatives activated by grassroots communities were bridged with top-down services delivered by local government and other support organizations.

The project has evidenced itself as long-lasting through the mentoring of former University students, encouraging them to take over the delivery of further co-making workshops and the “Forest Coats” program, so that the project can continue and flourish self-sufficiently. The project contributed to raising people’s awareness of fashion sustainability and empowering them through building capabilities and helping them to pave their own career pathways, as well as enhancing community engagement and partnership building. The project also showed a wide array of formats in which fashion activism can manifest itself (from fashion artefacts, workshops, live art performances, panel debates through to exhibitions) to raise people’s awareness of sustainability-related issues in the fashion system and co-create social, cultural, economic, and environmental value. A model for an HEI to collaborate with a local government was piloted, and provides an opportunity to deepen the partnership, but could also be scaled out to other boroughs to contribute to place-making. Furthermore, whilst enabling change in others, the fashion activist leading the project (and first author of this paper) also undertook a process of change in himself and in his own way of engaging with making practices within a social context. In fact, the project contributed to reinforcing the values by which the fashion activist was driven to lead this project; that means a commitment to revitalize cultural heritage, tackle social inequalities, make local economies flourish, and enhance environmental stewardship.

Limitations and recommendations for future work

Although the project enabled the gathering of interesting findings and created positive impacts, several limitations were experienced throughout the process. The short-term nature of the evaluation process meant that it was not possible to measure any longer-term impacts of the project. It is important to highlight that this is a recurring issue in any social innovation projects; in fact, social impacts require a very long time to become manifest, often beyond the project’s timeframe. Furthermore, the outcomes of the project are mostly intangible and difficult to measure using quantitative metrics; however, there is evidence of several long-lasting legacies being activated within the local community, as previously discussed. Another limitation identified is the relatively small number of people who responded to the online surveys; however, the survey responses were complemented by in-depth qualitative data collected using other methods, such as participant observations. It is also important to acknowledge that activating change from within the system – as a partnership between an HEI and local government – implied facing significant institutional barriers. In fact, the project demonstrated the true nature of working as a design activist within an academic institution. This involves having to complete numerous administrative tasks, handle several legal and financial issues, undertake complex evaluation procedures and continuous reporting to different stakeholders and audiences.

As next steps, the approach devised and implemented for the project could be further developed and tested in other contexts to build a transferable model of working that contributes to place-making. It is also recommended that local governments and HEIs collaborate and take joint actions to support businesses, strengthen existing networks and enable local people and organizations to thrive. In such contexts, it is also important for the education partner to map out and better understand all the different programs existing across different government departments and consider how they could be joined up or better developed. Finally, we hope that this paper will inspire the reader about the many ways in which fashion activism can be used as a tool to engage, through making, with local communities, and activate positive socio-economic change, from within or outside the system, and contribute to shaping a more sustainable future.

Acknowledgements

The “Making for Change: Waltham Forest” project was part-funded by the Sheepdrove Trust, London Borough of Culture 2019, London Borough of Waltham Forest, and Great Place: Creative Connections, a programme supported by Arts Council England and the National Lottery Heritage Fund. We would also like to express infinite gratitude to all the project participants who gave their invaluable contribution to activating positive change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Francesco Mazzarella

Dr Francesco Mazzarella is Senior Lecturer in Fashion and Design for Social Change at London College of Fashion, UAL. Francesco’s research spans the fields of fashion activism, craftsmanship, design for social innovation, sustainability, and place-making. Previously, Francesco was AHRC Design Leadership Fellow Research Associate at Imagination, Lancaster University, supporting design research for change. Francesco’s doctoral research project explored how service design can be used to activate textile artisan communities to transition towards a sustainable future. [email protected]

Sandy Black

Sandy Black is Professor of Fashion and Textile Design and Technology at Centre for Sustainable Fashion, a University of the Arts London research centre. Current research interests include design-led and interdisciplinary research (areas including fashion, textiles, technology, culture, industry, and sustainability) and the role of creative entrepreneurship, design, and new business models in addressing issues of sustainability in the fashion and textiles sectors. [email protected]

References

- A New Direction 2019. Waltham Forest Fashion District: Partnership Plan. London, UK: A New Direction.

- Banerjee, B. 2008. “Designer as Agent of Change: A Vision for Catalysing Rapid Change.” Paper Presented at the Changing the Change Conference, Turin, July 10–12.

- BOP Consulting 2017. “The East London Fashion Cluster Strategy and Action Plan.” Accessed 6 September 2021. https://www.fashion-district.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/East-London-Fashion-Cluster-Draft-and-Strategy-Plan.pdf

- Bruggeman, D. 2018. Dissolving the Ego of Fashion: Engaging with Human Matters. Arnheim: ArtEZ Press.

- Burns, L. 2019. Sustainability and Social Change in Fashion. New York: Fairchild Books.

- Corbett, S. 2017. How to Be a Craftivist: The Art of Gentle Protest. London, UK: Unbound.

- Fassi, D, et al. 2019. Universities as Drivers of Social Innovation – Theoretical Overview and Lessons from the “Campus” Research. New York, NY: Springer.

- Fletcher, K. 2018. “The Fashion Land Ethic: Localism, Clothing Activity and Macclesfield.” Fashion Practice 10 (2): 139–159. doi:10.1080/17569370.2018.1458495.

- Friedman, V. 2016. “Fashion’s Newest Frontier: The Disabled and the Displaced.” Accessed 11 February 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/21/fashion/solution-based-design-disabled-refugees.html?_r=1

- Fuad-Luke, A. 2009. Design Activism: Beautiful Strangeness for a Sustainable World. London, UK: Earthscan.

- Fuad-Luke, A. 2017. “Design Activism’s Teleological Freedoms as a Means to Transform our Habitous.” Accessed 18 March 2021. http://agentsofalternatives.com/?p=2539

- Hackney, F. 2013. “Quiet Activism and the New Amateur: The Power of Home and Hobby Crafts.” Design and Culture 5 (2): 169–193. doi:10.2752/175470813X13638640370733.

- Harris, J, et al. 2021. Business of Fashion, Textiles & Technology: Mapping the UK Fashion, Textiles and Technology Ecosystem, London, UK: University of the Arts London.

- Hirscher, A.-L. 2013. “Evaluation and Application of Fashion Activism Strategies to Ease Transition towards Sustainable Consumption Behaviour.” Research Journal of Textile and Apparel 17 (1): 23–38. doi:10.1108/RJTA-17-01-2013-B003.

- Hirscher, A.-L. 2020. “When Skillful Participation Becomes Design: Making Clothes Together.” PhD diss., Aalto University.

- Hirscher, A.-L, and K. Niinimäki. 2013. “Fashion Activism through Participatory Design.” Paper Presented at the 10th European Academy of Design Conference – Crafting the Future, Gothenburg, April 17-19.

- Hirscher, A.-L., Mazzarella F., and A. Fuad-Luke. 2019. “Socializing Value Creation through Practices of Making Clothing Differently: A Case Study of a Makershop with Diverse Locals.” Fashion Practice 11 (1): 53–80. doi:10.1080/17569370.2019.1565377.

- IAP2 2014. “What is the Spectrum of Public Participation?” Accessed 2 June 2020. https://sustainingcommunity.wordpress.com/2017/02/14/spectrum-of-public-participation/

- Kemmis, S, and R. McTaggart. 2003. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry, 2nd ed. London, UK: Safe Publications Ltd.

- London Borough of Waltham Forest 2017. “Connecting Communities Strategy.” Accessed 2 June 2020. http://www.walthamforest.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Connecting-Communities-Strategy.pdf

- London Borough of Waltham Forest 2020. “Statistics about the Borough.” Accessed 2 June 2020. https://www.walthamforest.gov.uk/content/statistics-about-borough

- Malinowski, B. 1987. Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Manzini, E. 2014. “Making Things Happen: Social Innovation and Design.” Design Issues 30 (1): 57–66. doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00248.

- Mazzarella, F., H. Storey, and D. Williams. 2019. “Counter-Narratives towards Sustainability in Fashion – Scoping an Academic Discourse on Fashion Activism through a Case Study on the Centre for Sustainable Fashion.” The Design Journal 22 (sup1): 821–833. doi:10.1080/14606925.2019.1595402.

- Mazzarella, F., and A. Schuster. 2021. Cut. London, UK: University of the Arts London.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

- NCVO 2018. “How to Develop a Monitoring Evaluation Framework.” Accessed 2 June 2020. https://knowhow.ncvo.org.uk/how-to/how-to-develop-a-monitoring-and-evaluation-framework

- Pink, S. 2015. “Ethnography, Codesign and Emergence: Slow Activism for Sustainable Design.” Global Media Journal: Australian Edition 9 (2): 1–10.

- Sadler, D. R. 1981. “Intuitive Data Processing as a Potential Source of Bias in Educational Evaluation.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 3 (4): 25–31. doi:10.3102/01623737003004025.

- Turnstall, D. 2018. “Design’s Role in Activism can go Deeper Than Posters and T-Shirts” Accessed 22 February 2022. https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/designs-role-in-activism-can-go-deeper-than-posters-and-t-shirts/

- Von Busch, O. 2008. “Fashion-Able: Hacktivism and Engaged Fashion Design.” PhD diss., University of Gothenburg.

- William Morris Big Local Plan. 2010. “William Morris Big Local Plan.” Accessed 2 June 2020. http://www.wmbiglocal.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/William-Morris-Big-Local-Plan-08-10.pdf

- Williams, D. 2018. “Fashion Design as a Means to Recognize and Build Communities-in-Place.” She Ji. The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 4 (1): 75–90. doi:10.1016/j.sheji.2018.02.009.