Abstract

Can a piece of cloth influence the way we live? Athleisurewear, a portmanteau of the words “athletic” and “leisure” has emerged as fashionable activewear which is worn for both exercising and as everyday casual wear. Athleisurewear consumers are inspired by the “fitspiration” movement where their intentions are to appear fit and healthy to the society they inhabit. Athleisurewear sales are forecast to surpass all other forms of casual apparel in the coming years. Motivated by these intriguing discussions, this report systematically reviewed 39 studies involving the athleisurewear trend which consisted of 9 journal articles, 5 conference papers, 2 book chapters, 1 thesis, 2 industry reports and 20 online fashion blogs/news. Commercially published academic literature on athleisurewear was scarce and identified the trend as under-researched. Yet much literature exists in gray literature sources which were fashion blogs/news. We suggest three main themes derived from these literatures: (1) Athleisurewear and fit-inspired lifestyle; (2) Enclothed cognition and athleisurewear; (3) Athleisurewear and the need for sustainability.

Introduction

What strange power there is in clothes.

∼Isaac Bashevis Singer∼

Singer, a Nobel Prize-winning author, asserts that there is great power and sway in the clothes we wear (Adam and Galinsky Citation2012, 1). A continuation of this assertion is emphasised in books such as Dress for Success by John T. Molly and television shows like What Not to Wear (Molly Citation1988; IMDB Citation2022). These books and TV shows highlight the power clothes have over others by creating favourable impressions for the wearer and the power clothes have over the wearer’s behavioural tendencies.

A remarkable resemblance to these assertations is seen in athleisurewear, a portmanteau word combining Athletic and Leisure (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). Athleisurewear apparel is fashionable sportswear worn for both exercising and non-exercising settings (Tascperformance Citation2022). Therefore, athleisurewear apparel is designed to integrate functionality of sportswear and aesthetic attributes of casual fashion wear.

What separates athleisurewear from activewear and other monikers of activewear (sportswear, athletic wear, gym wear) is that athleisurewear is clothing designed to be suitable for both exercising and everyday activities whereas activewear is clothes designed for recreational purposes only (Sarkar Citation2020; Tascperformance Citation2022; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Lexico Citation2022; Wilson Citation2018). A clear definition of athleisurewear and activewear is also available in the Oxford English dictionary which distinctively identifies the difference between athleisurewear and activewear (Lexico Citation2022). However, it is important to keep in mind that athleisurewear is a hybrid of activewear and casual fashion wear and hence, it comprises elements of activewear.

Demand for athleisurewear has been growing significantly which is expected to surpass all other forms of casual apparel in production, sales and consumption in the coming years (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). Hence, a number of studies have been carried out on the athleisurewear trend during the past decade (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Watts and Chi Citation2019; Kim, Jung, and Oh Citation2017; Patrick and Xu Citation2018; Clarke-Sather and Cobb Citation2019; Lyu Citation2018; dos Reis et al. Citation2018; Ganak et al. Citation2019; Yan et al. Citation2020; Liu Citation2020).

Prior literature traces the modern movement of athleisurewear to the 1970s (Tascperformance Citation2022). Yet athleisurewear apparel truly originated in the late nineteenth century (Thompson Citation2018). The onset of the trend was when the first shoes with rubber bottoms were manufactured for athletes in 1892. The rubber bottoms provided better traction on tennis courts and were increasingly seen being worn by tennis players outside of sports settings and therefore earned the name tennis shoes (Tascperformance Citation2022; Basyah Citation2020). In a similar period, universities in the USA became very popular for intramural sports and men who engaged in sports were seen wearing athletic clothes to class before or after practise (Thompson Citation2018).

In the 1920s, the polo shirt was designed for tennis players which provided more breathability over the existing then popular long-sleeved design (Thompson Citation2018; Weibe Citation2013). Later polo shirts were co-opted by polo players (Thompson Citation2018). Thereafter, relaxed silhouettes of sportswear fashion grew significantly (Weibe Citation2013; Basyah Citation2020). Today, few people will only think of polo shirts as being athleisurewear, yet these were the foundations that led to the athleisurewear trend.

Designers Coco Chanel and Jean Patou took fashionable sportswear mainstream. Chanel was identified for her excellent signature style designs that distinguishably reflected sports elements from hunting and horseback riding (Tascperformance Citation2022; Weibe Citation2013; Basyah Citation2020).

Later in the twentieth century, novel clothing designs began to emerge that catered to the needs of athletes. Shorts were designed for the gym, running shoes were designed for sprinters and these athletes wore running shoes and gym shorts outside of sports settings (Thompson Citation2018; Weibe Citation2013).

By the 1970s modern athleisurewear apparel emerged due to people engaging in more exercise and focusing on physical fitness (Guzzetta Citation2022). Fashion companies saw a growing opportunity and began innovations in fabric designs which were moisture-wicking properties, improved breathability, and odour-wicking technologies (Guzzetta Citation2022; Basyah Citation2020; Thompson Citation2018).

Despite the shift in consumer demand towards casual athleisurewear, the term athleisure was first used in the magazine Nation’s Business (Citation1979) and was used to describe clothing designed for people who wanted to look athletic (Merriam-Webster Citation2022; Poplin Citation2020; Tascperformance Citation2022), which could also be the rationale for most people tracing the athleisurewear trend to the 1970s.

Today’s athleisurewear trend is continuing to fulfil people’s desires to wear fashionable athleisurewear outside of the gym for everyday activities (Poplin Citation2020; Liu Citation2020; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). Increasing demand by consumers wanting their clothes to transition seamlessly from exercising to their social life or even work-life is also amplifying demand (Liu Citation2020; Kim, Jung, and Oh Citation2017). Hence, athleisurewear consumers demand clothes for not only exercising purposes but also to go out with friends and family, when returning to work or to perform a workout after or before work (Kim, Jung, and Oh Citation2017). This has led more people to embrace athleisurewear as their go-to casual attire (Kim, Jung, and Oh Citation2017; Liu Citation2020).

Wilson (Citation2003) emphasised that the clothes we wear are an extension of ourselves and communicate a message or a symbolic meaning of ourselves to others (Entwistle Citation2000). Hence, Barnard (Citation2002) states that when people wear specific clothes, they do so to communicate specific socially desirable characteristics to observers. We, therefore, suggest that humans’ deep relationship with the clothes they wear could justify the subconscious yet instinctive creation of the athleisurewear trend that has expanded globally.

Market analysts discuss the phenomena of athleisurewear enthusiasts as being motivated by the Fitspiration movement, where their intentions are to appear fit and healthy while actually living or pretending to live an active lifestyle (Kim, Jung, and Oh Citation2017; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). Reflecting this, there exists evidence that athleisurewear wearers are perceived by their audience as active, healthy and confident (Kim, Jung, and Oh Citation2017; Petriccione Citation2018; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). The wearers themselves were also unconsciously more comfortable, confident and had higher self-esteem than when dressed in traditional formal attire, suggesting that the psychological element of being more confident and of having higher self-esteem when wearing athleisurewear could further explain the increasing demand for athleisurewear among individuals (Kim, Jung, and Oh Citation2017; Petriccione Citation2018; Liu Citation2020; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020).

Athleisurewear, therefore seems to have an effect on the wearer’s psychological and behavioural tendencies. This phenomenon is theorized by Adam and Galinsky (Citation2012) in their theory of enclothed cognition which experiments with the systematic influence clothes have on the wearer’s psychological and behavioural tendencies. The theory asserts that the symbolic meaning associated with a type of clothing can influence the wearer’s behavioural tendencies. This could be seen in athleisurewear as athleisurewear consumers are seen to be motivated to live a specific type of a fit-inspired lifestyle by the clothes they wear.

We further suggest that, as discussed by Cataldo et al. (Citation2021), people desire to have a model-like body that they see on social media and in fashion advertisements, which may also have influenced the creation of the athleisurewear trend. Therefore, consumers of athleisurewear are seen to be using athleisurewear to imagine themselves progressing towards achieving a model-like figure. This phenomenon is also discussed by Thompson (Citation2018) that the athleisurewear consumer grasps the status as a very healthy and active person. We, however, suggest that this desire could be an illusion for some consumers where they struggle with body identity issues as according to Kim, Jung, and Oh (Citation2017); Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths (Citation2020); and Cataldo et al. (Citation2021), some individuals are wearing athleisurewear as a means to appear active and healthy while pretending to live an active lifestyle.

An inherent characteristic of the fashion industry is its frequent shifts in trends and consumer demands. Yet, an unexpected phenomenon that led the industry towards significant uncertainty was the global Covid-19 pandemic (Salfino Citation2020; Bloomberg and Freund Citation2020).

Significant shifts in consumer behaviour were visible by March 2020 (Salfino Citation2020; Bloomberg and Freund Citation2020). Governments imposed countrywide lockdowns as a response to mitigate the transmission of the virus which required most people to work from home (Salfino Citation2020; Becker et al. Citation2021). As a result, consumers intuitively changed their traditional formal-work attire to more comfortable work-from-home outfits (Becker et al. Citation2021; Salfino Citation2020). People quickly embraced athleisurewear and it became their day-to-night outfits which were also suitable for zoom meetings (Salfino Citation2020). Athleisurewear also allowed consumers to comfortably enjoy evening Netflix and chill time (Salfino Citation2020; vid Bloomberg and Freund Citation2020; Becker et al. Citation2021).

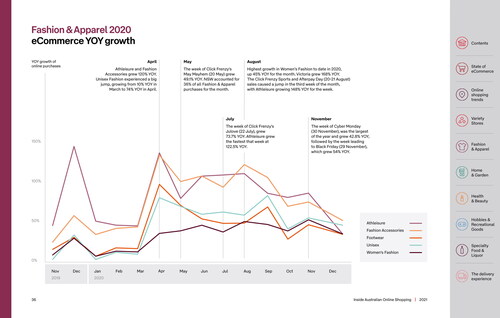

By December 2019, online athleisurewear and accessories purchases in Australia increased by 120% (refer to ) while the extensive year on year (YOY) growth of athleisurewear purchases surpassed all other types of fashion (refer to ) (Australia Post Citation2020; Australia Post Citation2021). The reports by Australia Post indicated that this growth was mainly due to an increase in homegrown athleisure brands and consumers shifting to online shopping in Australia. Similarly, the demand for online shopping further increased when the pandemic began which forced consumers to shop online as a result of retail outlet closure (Australia Post Citation2020; Australia Post Citation2021).

Figure 1 YOY growth of fashion and apparel in Australia. Source: Australia Post, Citation2021; Australia Post, Citation2020.

Therefore, we suggest that this growth rate seems to reflect the industry’s already growing demand for athleisurewear in Australia due to consumers becoming more health-conscious. Moreover, this demand for athleisurewear increased further during the pandemic as athleisurewear became congruent with the pandemic-influenced consumer behaviour (i.e. athleisurewear provided comfort and versatility in navigating work-from-home and leisure times during the pandemic). Therefore, consumers’ consumption of athleisurewear in Australia was further amplified.

A survey by J.P. Morgan on stimulus spending during the pandemic identified that consumers seek athleisurewear exceedingly (Salfino Citation2020). Wall Street Journal’s survey reported that 24% of respondents chose athleisurewear as the top-three categories they intend to spend their stimulus checks on (Forman and Lee Citation2020).

Allied Market Research’s industry report indicates that the US Athleisurewear market was worth $155.2 billion in 2019 and is expected to reach $257.1 billion by 2026 (Gosselin Citation2020). This reflects a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of 6.7% from 2019 to 2026 (Gosselin Citation2020).

Data analysed from 17,000 fashion brands in the USA confirmed that their athleisurewear orders increased by 84% since the start of the pandemic in 2019 (Bringé Citation2021). Similarly, the UK athleisurewear industry reported a five-times increase in women’s athleisurewear bottoms from April 2020 to December 2020 (Bringé Citation2021).

Research by 2020 Cotton Incorporated Lifestyle Monitor™ indicates that nearly half of all US consumers (48%) have replaced some of their denim jeans with activewear or athleisurewear bottoms, while 37% indicate that they prefer to wear athletic pants over denim jeans (Salfino Citation2020). Similarly, a survey by Monitor™ identified that among people who had to work outside of their home, 7 in 10 (70%) preferred a job that permitted them to wear a casual dress code over a formal dress code in the US (Salfino Citation2020).

Global marketing research intelligence firm, Fact.MR, discussed that athleisurewear has revolutionised the global casual clothing sector, where stretchy suits, smart sneakers and high-tech fabrics are increasingly being worn at the workplace (Salfino Citation2020; Fact.MR Citation2020).

This demand is further increased by fashionable athleisurewear garments consisting of advanced materials such as increased breathability, temperature-regulating and wrinkle-resistant technologies (Salfino Citation2020).

Monitor™ data also indicates that 4 in 5 consumers (82%) in the U.S. are looking for work clothes designed to be more versatile, meaning they can be worn for any place they intend to go throughout the day (Salfino Citation2020). Monitor™ also indicates that over one-third of workers (34%) preferred a job that permits them to wear an informal dress code than receiving an extra US $5000 (annual) in salary (Salfino Citation2020).

Athleisurewear was considered a megatrend even before the Covid-19 pandemic (Becker et al. Citation2021). The pandemic’s beginning brought uncertainty which slackened the growth of athleisurewear (refer to ), yet soon it turned out to be the silver lining of the athleisurewear trend.

On the contrary, a business consultancy firm, Boston Consultancy Group suggests that the following years could be the most tumultuous the fashion industry will experience (Bianchi et al. Citation2020; Salfino Citation2020). Significant fluctuations in demand for athleisurewear could be expected (refer to ). Similarly, market consultancy firm, NPD Group also indicated that women’s activewear purchased for both leisure activities (casual/everyday) and performance activities (athletics/exercises/sports) have declined in sales in 2019 (Salfino Citation2020). Brick and Mortar stores worldwide were forced to close, resulting in significant losses for fashion businesses that acquired a larger segment of company revenue from physical stores (Bringé Citation2021).

Prior to the pandemic, big brands such as NIKE, Lululemon, Adidas, and Puma focused on increasing brand visibility through sports clubs, sports leagues and event sponsorships (Becker et al. Citation2021). An intriguing shift in fashion marketing during the pandemic was that these companies invested more in online platforms and social media influencers to create brand visibility. Continuous event cancellations and empty stadiums even after lockdowns lifted in some parts of the world were the main reason (Becker et al. Citation2021).

Despite fascinating discussions on the athleisurewear trend and its consumers, no systematic literature review has ever been conducted on the athleisurewear trend and its consumers to date. Additionally, existing studies have identified the athleisurewear trend as an under-researched area (Chang, Yurchisin, and Shin Citation2019; Patrick and Xu Citation2018). Our development of a systematic literature synthesis on the athleisurewear trend also identified that there were only 18 commercially published papers specifically focused on the athleisurewear trend. This further identifies the problem of the athleisurewear trend as being under-researched.

As demonstrated by Dwivedi et al. (Citation2011) and Kim et al. (Citation2018), for a particular research field to progress forward, it is critical to identify historical patterns to observe and recognise meaningful insights. These novel insights could lead to possible future developments and implications for that field of research. Similarly, systematic literature reviews have been considered as essential exercises to investigate and identify knowledge produced in a field of inquiry, its research gaps and possible implications for future developments (Pahlevan-Sharif, Mura, and Wijesinghe Citation2019; Grant and Booth Citation2009).

Hence, this research aims to systematically analyse existing literature on the athleisurewear trend to identify the scope of literature on this trend. We believe that it would allow us to identify existing research gaps and possible implications for future research developments.

Method

Based on the Cook, Mulrow, and Haynes (Citation1997) guidelines, a systematic review was conducted on the athleisurewear trend. Further for best achieving the purpose of a systematic review, we refer to Baumeister’s (Citation2013), advice to adopt a mindset of judge and jury instead of a lawyer’s. A judge and jury carefully evaluate the available evidence to render the fairest possible judgment where a lawyer’s approach is to make the best case for one side of the argument.

For the purpose of this study, a customised protocol was employed that consisted of (1) a comprehensive and systematic literature search strategy, (2) a pre-defined inclusion criteria for studies, and (3) a data collection process on the athleisurewear trend. This was conducted on 20th August 2020 and repeated on 16th November 2021. The purpose of the second search was to include grey literature to reduce publication bias and provide comprehensiveness and timeliness, which allowed a balanced picture of available evidence on the athleisurewear trend (Paez Citation2017).

The search strategy was implemented on the Web of Science, Science Direct, SAGE Journal, Google Scholar, Scopus, IBISWorld database and Google search. These databases were specifically utilised due to their up-to-date references and their significant recognition and utilisation by scholars and research experts in miscellaneous research fields.

Pre-defined criteria for the search strategy comprised the following and were repeated on all databases: (1) Specific keywords, athleisure and athleisurewear, were used to search for articles on the athleisurewear trend. We referred to the differences between athleisurewear vs. activewear and monikers of activewear (sportswear, gym wear, athleticwear) discussed by Sarkar (Citation2020), Tascperformance (Citation2022), Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths (Citation2020), and Lexico (Citation2022), where it is discussed that athleisurewear are fashionable clothes designed for both exercising and everyday activities whereas activewear is for recreational purposes only. We also referred to the definitions of the words, athleisure and activewear in the Oxford English dictionary which distinctively describes the difference between athleisurewear and activewear (Lexico Citation2022). Similarly, Chip Wilson (founder of LuluLemon also known as the “godfather of athleisurewear”) states that the terms athleisurewear and technical apparel (activewear) have become confused and conflated in the apparel space (Wilson Citation2018). He further states that both athleisurewear and technical apparel (activewear) are comprised of two vastly different markets, with different functions, different cultures, and different ways of looking at their consumer (Wilson Citation2018). Hence, we used specific keywords.

(2) No limitation was imposed on the year of publication, language, methodology or framework used and geographical location of the study.

(3) Cross-checked reference lists of the selected studies focused on athleisurewear trend. This allowed for an “all possible” search result outcome for the athleisurewear trend. Final search results from each database consisted of items; Web of Science (n = 7), Science Direct (n = 20), SAGE Journal (n = 3), Google Scholar (n = 1350), Scopus (n = 25) and IBISWorld (n = 26). Hence, search result items from all databases were (n = 1431) as of 20th August 2020. The search result conducted on 16th November 2021 was the same for all databases except for Google Search database which was manually conducted to included grey literature (n = 20). Therefore, search result for all databases were (n = 1451).

All identified items were screened in accordance with a set of inclusion criteria which required items to satisfy the following characteristics for inclusion in the systematic review: (1) Items were restricted to journal articles, book chapters, conference papers, industry reports and online fashion blogs to maintain reliability and accuracy of the review, (2) Items should include the keyword athleisure in either title, abstract, introduction, keyword section or in the full-text section, (3) The research study should focus on either the athleisurewear trend or athleisurewear consumers or contain literature on athleisurewear, (4) literature needed to be published in English, or be able to be translated into English, and (5) full-text needed to be available. Inclusion criteria were respectively implemented in the above order, which narrowed down the search result items to a total of n = 39 items to be included in the systematic review.

However, inclusion criteria were moderated for Google search as the search results were significant. Therefore, only 20 online fashion blogs were selected due to the repeating nature of literature found on online blogs. Hence the included study items were journal articles (n = 9), conference papers (n = 5), book chapters (n = 2), thesis (n = 1), industry reports (n = 2) and fashion blogs (n = 20). Items excluded from the search result were omitted due to: (1) Not being journal articles, conference papers, book chapters, theses, industry reports, not being fashion blogs, (2) not including athleisure as a keyword in the title, abstract or in the full-text section, (3) Not including literature relevant to the athleisurewear trend, or (4) not published in English and could not be translated into English (i.e. Two foreign language studies in Korean language were identified and run through Google Translate. Results were negative for both studies as it generated unreadable texts and objects).

The final sample of n = 39 included in the systematic review was screened for full text and assessed to be relevant to this study focused on the athleisurewear trend. All authors then screened the included studies and any disagreements on inclusion and exclusion were discussed and revised until reaching a consensus. Similarly, the data extraction process from the selected items was performed by reading the full text of all articles, book chapters, conference papers, the thesis, the industry report and the online blogs. The data extracted from each study were entered into a table. Data extraction focused on: (1) Research Objective, (2) Conceptual Framework, (3) Methodology, (4) Key Findings, (5) Main Themes, and (6) Future Research.

Discussion of the Empirical Findings

Commercially published study items identified on athleisurewear were only n = 18 which classifies athleisurewear as an under-researched area. However, most literature exists in grey literature sources, specifically in online fashion blogs which focus on the latest athleisurewear trends and news. We identified main themes derived from these literatures and categorised them into three segments: (1) Athleisurewear and fit-inspired lifestyle; (2) Enclothed cognition and athleisurewear; (3) Athleisurewear and the need for sustainability.

Athleisurewear and fit-inspired lifestyle

Athleisurewear has combined functional and performance attributes of activewear with aesthetic attributes of fashionwear to deliver trendy fashionable sportswear (Liu Citation2020; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Tascperformance Citation2022; Guzzetta Citation2022). The trend continues as consumers wear athleisurewear to almost every place, including the workplace (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Guzzetta Citation2022). Demand for athleisure footwear has also seen an increase in the past five years where individuals are wearing athletic footwear as daily wear (Kim, Jung, and Oh Citation2017; Ganak et al. Citation2019; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Yan et al. Citation2020; Thompson Citation2018).

Rising health consciousness among consumers is the key motivator behind the demand for athleisurewear (Chang, Yurchisin, and Shin Citation2019; Poplin Citation2020; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). These consumers are classified as Gen Y consumers aged 18 to 34 and are considered a key market segment for the growth of athleisurewear sales (Patrick and Xu Citation2018). Gen Y consumers who are athleisurewear enthusiasts believe in the fit-inspired lifestyle where their intentions are to appear fit and healthy while they may or may not live an active lifestyle (Salpini Citation2018; Guzzetta Citation2022; Thompson Citation2018; Poplin Citation2020; Cataldo et al. Citation2021). Hence, athleisurewear consumers are resilient followers of the fitspiration movement.

For athleisurewear consumers, the concept of a fit-inspired healthy lifestyle is associated with several contributing factors (e.g. healthy diet, constant exercising, positive mental and physical health, responsible consumption) (Salpini Citation2018; Guzzetta Citation2022; Thompson Citation2018; Poplin Citation2020; Cataldo et al. Citation2021; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Griffiths and Stefanovski Citation2019; Griffiths et al. Citation2018; Jong and Drummond Citation2016; Vaterlaus et al. Citation2015). Hence, athleisurewear consumers consider these behaviours as essential qualifiers to becoming a consumer of athleisurewear.

Since athleisurewear consumers share commonalities with fitspiration lifestyle, it motivates them to adhere to attitudes and behaviours that reflect fitness and wellbeing (Griffiths and Stefanovski Citation2019; Griffiths et al. Citation2018; Jong and Drummond Citation2016; Vaterlaus et al. Citation2015). Hence, wearing athleisurewear may trigger certain emotions or behaviours associated with the fit-inspired athleisurewear lifestyle (e.g. self-esteem, confidence, feeling of athleticism, healthy eating patterns and responsible consumption) (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Griffiths and Stefanovski Citation2019; Griffiths et al. Citation2018; Jong and Drummond Citation2016; Vaterlaus et al. Citation2015).

An intriguing discussion is that athleisurewear consumers thought that exercising is a gateway to the athleisurewear lifestyle and only once they start engaging in exercise they felt as though they had permission to wear athleisurewear (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). Athleisurewear consumers believe embracing the fitspiration lifestyle allows them to be of healthy mind and body, increase self-esteem, gain social recognition and allow them to be seen as trendsetters, hence they consume athleisurewear (Patrick and Xu Citation2018; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Guzzetta Citation2022; Thompson Citation2018).

An individual wearing athleisurewear is therefore associated with engaging in frequent physical activity. However, the physical appearance of the wearer’s body has a significant impact on this assumption (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). Therefore, athleisurewear consumers perceived that if a person wearing athleisurewear does not have an athletic (thin-fit) body image, he/she might be on a journey toward achieving a thin-fit body image (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Guzzetta Citation2022; Thompson Citation2018; Poplin Citation2020).

Similarly, mental health is crucial in achieving a healthy lifestyle as perceived by athleisurewear consumers (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Guzzetta Citation2022; Thompson Citation2018). Therefore, they believe athleisurewear wearers have positive emotional and mental states such as self-confidence, friendliness, happiness, self-discipline, commitment, and diligence (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020).

Other prominent characteristics of athleisurewear consumers are their concern towards environmental and social issues than any other type of fashion consumer (Salpini Citation2018; Guzzetta Citation2022; Thompson Citation2018; Poplin Citation2020; Cataldo et al. Citation2021; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Griffiths and Stefanovski Citation2019; Griffiths et al. Citation2018; Jong and Drummond Citation2016; Vaterlaus et al. Citation2015). We suggest that this may be due to their behaviours of being responsible and believing in a healthy lifestyle which the surrounding environment and the social environment they inhabit should bring into line.

Athleisurewear consumers are also seen to have the ability to influence the social environment they inhabit to embrace the lifestyle they live (Guzzetta Citation2022; Thompson Citation2018; Poplin Citation2020; Cataldo et al. Citation2021). We suggest that this may be because followers of the fit-inspired lifestyle are significantly reliant on social media for information about living a healthy lifestyle (Cataldo et al. Citation2021; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). Since Gen Y consumers who are also athleisurewear consumers are high users of social media, they are significantly influenced to follow athleisurewear lifestyle while influencing one another (Cataldo et al. Citation2021; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). This is also another phenomenon of the extremely increasing demand for athleisurewear.

While athleisurewear consumers seem to be fit and healthy or on a journey toward an active lifestyle, fit-inspired lifestyle sometimes seems to be an illusion for consumers as they pretend to live an active lifestyle while dealing with body identity issues (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). A qualitative study by Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths (Citation2020) on athleisurewear consumers, discussed that people have been struggling to keep up with the so-called fit-inspired lifestyle which made them depressed, angry and unable to perform well at work. A feeling of guilt seems to be the reason. Referring to Guzzetta (Citation2022), Thompson (Citation2018) and Poplin (Citation2020), we suggest athleisurewear consumers seems to be influenced to live a fit-inspired lifestyle due to the thin-fit body image they see on social media which is unrealistic to achieve in real life and sometimes might affect their mental and physical well-being.

Enclothed cognition and athleisurewear

The term enclothed cognition describes the systemic influence clothes have on the wearer’s psychological process and behavioural tendencies. Theory of enclothed cognition derives from embodied cognition (Adam and Galinsky Citation2012).

Theory of embodied cognition suggests that experiencing a type of physical activity (e.g. dancing, change of body posture) or perceptual experience (e.g. scent, cold, warmth) is stored in human memory as abstract concepts and the brain assigns symbolic meanings to these experiences (Barsalou Citation1999; Barsalou Citation2008; Glenberg Citation1997; Niedenthal et al. Citation2005). Thus, physical experiences can elicit associated abstract concepts and mental stimulation through symbolic meaning (Adam and Galinsky Citation2012).

For example, research suggests that the physical experience of cleaning oneself is associated with the abstract concept of moral purity (Zhong and Liljenquist Citation2006). Hence, physical cleaning influences a person’s judgments of morality through its symbolic meaning (Schnall, Benton, and Harvey Citation2008). A person experiencing physical warmth leads to increased feelings of interpersonal warmth (Williams and Bargh Citation2008). A person nodding while listening to a persuasive message increases his/her susceptibility to persuasion (Wells and Petty Citation1980).

Similarly, experiencing clean scents increases one’s tendency to reciprocate trust and offer charitable help (Liljenquist, Zhong, and Galinsky Citation2010). A person adopting an expansive body posture affects a sense of power and related action tendencies despite not being in a powerful role (Huang et al. Citation2011).

Adam and Galinsky (Citation2012) suggest that similar to physical experience, wearing clothes also triggers associated abstract concepts and corresponding symbolic meanings. Thus, the experience of wearing a piece of clothing exerts an influence over the wearer’s psychological process by activating associated abstract concepts through its symbolic meaning.

An experiment was conducted by using a Stroop test to evaluate the influence clothes have on an individual’s performance of attention-related tasks. A Stroop test is a colour and word test where the task is to identify the colour instead of the word (e.g. the word red is printed in blue, hence the answer is blue) (Jensen Citation1965). Each student was randomly given a white lab coat mentioned as a doctor’s coat or mentioned as a painter’s coat. Students had a higher performance rate in the Stroop test if they wore the white lab coat mentioned as a doctor’s coat compared to students who wore the same white coat but were mentioned as a painter’s coat. Students who did not physically wear the white coat did not have a higher performance rate. Adam and Galinsky (Citation2012) further discuss that students’ performance varied due to the differences in symbolic meaning associated with the doctor’s coat and painter’s coat. However, these variations were visible only when students physically wore the coats. Hence, they discuss the systematic influence of clothes on the wearer’s psychological and behavioural tendencies as a result of the associated symbolic meaning of the clothes.

Embodied cognition and enclothed cognition may function in similar ways. Yet, there exists a significant difference. In embodied cognition, the connection between the physical experience and its associated symbolic meaning is direct as the symbolic meaning always directly stems from the experience itself (Adam and Galinsky Citation2012).

In enclothed cognition, however, the process is indirect. The symbolic meaning is only achieved when the article of clothing is worn, and this means that the symbolic meaning derives from wearing the clothes. Therefore, it is not achieved until an individual physically wears and thus embodies the clothes. Therefore, enclothed cognition involves the co-occurrence of two independent variables: (a) the symbolic meaning of the clothes and (b) an individual is physically wearing the clothes (Adam and Galinsky Citation2012). We acknowledge the theory of enclothed cognition put forward by Adam and Galinsky (Citation2012) and suggest the systematic influence athleisurewear has on the wearer’s psychological process and behavioural tendencies.

Athleisurewear literature reflected that wearers of athleisurewear had adherence to a particular lifestyle (fit-inspired lifestyle). Therefore, wearing athleisurewear motivated consumers to engage in behaviours and emotions related to the fit-inspired lifestyle (e.g. feeling of high self-esteem, confidence, feeling of athleticism, healthy eating patterns, responsible consumption, constant exercising, positive mental and physical health) (Salpini Citation2018; Guzzetta Citation2022; Thompson Citation2018; Poplin Citation2020; Cataldo et al. Citation2021; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Griffiths and Stefanovski Citation2019; Griffiths et al. Citation2018; Jong and Drummond Citation2016; Vaterlaus et al. Citation2015).

Athleisurewear consumers also expressed that athleisurewear acts as a mechanism towards achieving a healthy lifestyle and allows them to engage in frequent exercise (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). Athleisurewear consumers who lived with a larger body perceived that an essential prerequisite to wearing athleisurewear was to lose weight and start progressing toward the thin-fit body ideal (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020).

Athleisurewear consumers, therefore, articulated that wearing athleisurewear was a reward system that allowed them to be healthier. The feeling of athleticism when wearing athleisurewear also encouraged participants to engage in the role of an athlete and therefore perform more exercises (Salpini Citation2018; Guzzetta Citation2022; Thompson Citation2018; Poplin Citation2020; Cataldo et al. Citation2021; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Griffiths and Stefanovski Citation2019; Griffiths et al. Citation2018; Jong and Drummond Citation2016; Vaterlaus et al. Citation2015).

Athleisurewear consumers also articulated that the fit-inspired lifestyle associated with the trend influenced them to be in a positive mental state. Consumers expressed that wearing athleisurewear made them more disciplined, committed and hardworking (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020).

We suggest that since the athleisurewear trend is highly associated with the fit-inspiration lifestyle, consumers who are wearing athleisurewear are influenced to engage in behaviours associated with the trend as a means to embrace the fit-inspired lifestyle. Hence, we suggest that the symbolic meaning of athleisurewear is associated with the characteristics of the fit-inspired lifestyle as perceived by athleisurewear consumers. Therefore, we suggest that the symbolic meaning associated with athleisurewear is not limited to self-esteem, confidence, feeling of athleticism, healthy eating patterns, responsible consumption, constant exercising, positive mental health and other fitness and wellbeing behaviours. However, as expressed by athleisurewear consumers, they elicit these behaviours only when wearing athleisurewear (Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020). Hence, as Adam and Galinsky (Citation2012) explained, the theory of enclothed cognition may be evident in athleisurewear with the co-occurrence of the two independent variables, (1) symbolic meaning associated with the clothes (2) individual physically wears the clothes.

While the experiment by Adam and Galinsky (Citation2012) presented convincing evidence for the theory of enclothed cognition, Burns et al. (Citation2019) was unable to repeat the study and generate evidence on higher performance while wearing a lab coat. Burns et al. (Citation2019), however, do not attempt to claim that clothing has no behavioural impact on the wearer but call for a more effective experiment into the theory of enclothed cognition.

Athleisurewear and the need for sustainability

The fashion industry is considered the second most polluting industry in the world (second only to the oil industry) (Grappi, Romani, and Barbarossa Citation2017). Fast fashion, which has created the issue of clothing overproduction, overconsumption, microfiber pollution, and significant consumption of natural resources for fabric production are only a few ways the fashion industry pollutes the environment (Grappi, Romani, and Barbarossa Citation2017; Yan et al. Citation2020; Diddi et al. Citation2019; Kozar and Hiller Citation2013; Lee and Sanders Citation2016). Likewise, microfiber pollution is increasingly harming the environment as two-thirds of the textile industry products are made using synthetic fibres (that release non bio-degradable microfibers), thereby contributing to global climatic change (Yan et al. Citation2020).

Similarly, only 25% of fashion garments are recycled, while the rest pollutes the environment by amplifying landfill waste (Lee and Sanders Citation2016; Becker-Leifhold Citation2018; Niinimäki and Hassi Citation2011; Tokatli Citation2007). Despite concerns about waste pollution, industry production has been doubling every year (Bianchi and Birtwistle Citation2010). Clothes are, therefore, thrown away to landfill even before they are sold or consumed (Bianchi and Birtwistle Citation2010). Similarly, clothing consumption rate is expected to increase by 63% with regards to present global apparel consumption rate (Todeschini, Cortimiglia, and De Medeiros Citation2020). The increase will result in 63 million tons to 102 million tons of apparel by 2030 (Todeschini, Cortimiglia, and De Medeiros Citation2020).

Simultaneously, demand for athleisurewear grows exponentially and is expected to surpass all other forms of apparel in terms of sales, consumption and production (Yan et al. Citation2020; Lipson, Stewart, and Griffiths Citation2020; Thompson Citation2018). It is therefore expected to represent a significant portion of fashion industry apparel which could be 75% of all apparel (Petriccione Citation2018).

Due to the increasing demand for athleisurewear and the present issue of environmental pollution by the fashion industry, discussions are made on athleisurewear and environmental pollution. Ritch (Citation2015), Lyu (Citation2018) and dos Reis et al. (Citation2018) discuss integrating sustainable production of athleisurewear to tackle this issue. Strategy discussed by Lyu (Citation2018) talks about recycling used wool or other types of non-decaying landfills to produce sustainable athleisurewear garments.

Similarly, prominent sustainability trends and initiatives already exist within the fashion industry to effectively tackle the issue of environmental pollution. Some of these are circular economy, collaborative consumption, sharing economy, recycling, upcycling (use of recycled materials to create superior long-lasting products), fashion library (clothing subscription services that allow consumers to own the garment for a limited time), second-hand selling, use of sustainable raw materials, zero waste production approaches, capsule wardrobe (consumers intent to consume fewer clothes as possible), and lowsumerism (consumers committed to consuming fewer clothes as possible) (Todeschini, Cortimiglia, and De Medeiros Citation2020; Roncha and Radclyffe-Thomas Citation2016; Sorensen and Jorgensen Citation2019; Lam, Yurchisin, and Cook Citation2016; Hwang and Griffiths Citation2017).

Despite these sound strategies in the fashion industry, the level of environmental pollution continues at an alarming rate. A closer look reveals that the fashion industry and its businesses do not consider sustaining the environment as crucial (Tolliver, Keeley, and Managi Citation2020; Grappi, Romani, and Barbarossa Citation2017; Yan et al. Citation2020; Diddi et al. Citation2019). Rather the industry is focused on profit maximisation and catering to the everchanging demands of fashion consumers (Todeschini, Cortimiglia, and De Medeiros Citation2020).

The industry is therefore, predominantly controlled by the demands and behaviours of fashion consumers making fashion consumers a key motivator for sustainability as fashion businesses are merely practising sustainability to cater to the demand from fashion consumers wanting more transparency and sustainability from fashion businesses.

However, most existing research is focused on informing the fashion industry and its businesses on practising sustainability while the focus should be on informing fashion consumers about attaining sustainability. We suggest that this may be the issue for not attaining sufficient levels of sustainability within the fashion industry.

Since fashion consumers are identified as a key driver of sustainability in the fashion industry (Moretto et al. Citation2018), we suggest that athleisurewear consumers may provide an opportunity to implement effective consumption changes within fashion communities as the demand for athleisurewear is expected to surpass all other forms of apparel (75% of all apparel) and these consumers are also motivated by fit-inspired lifestyle while eliciting behaviours of responsible consumption. Additionally, for athleisurewear consumers to live the so-called fitspiration lifestyle, it is crucial that the environment they inhabit permits that.

Athleisurewear consumers also have the ability to influence the social environment they inhabit as they are heavy users of social media for information sharing and gathering. Similarly, athleisurewear consumers seek to be a part of the business where they are demanding a place to have a conversation regarding political, social, and economic issues that fashion businesses can address.

We suggest that considering the athleisurewear consumers’ adherence to the fit-inspired lifestyle, they may be effective drivers of sustainability within the fashion industry since their behaviours suggest responsible consumption. Nevertheless, it is important to consider that athleisurewear consumers are also consumers of fast fashion. Therefore, they are directly responsible for the environmental pollution issues. However, it is seen that athleisurewear consumers are seeking more and more responsible fashion consumption options but lack adequate sustainable consumption knowledge.

Conclusion

The athleisurewear trend is expanding on a significant level globally. While published literature on athleisurewear is still sparce, much literature exists in the grey literature sources (e.g. online fashion blogs/news). We proposed three themes derived from these literatures which are (1) athleisurewear and fit-inspired lifestyle, (2) enclothed cognition and athleisurewear and (3) athleisurewear and the need for sustainability.

Literature suggested that consumers of athleisurewear have a strict adherence to fit-inspired lifestyle. We therefore attempted to discuss the effects athleisurewear may have on the wearer’s psychological and behavioural tendencies by acknowledging the theory of enclothed cognition. Literature suggested that the occurrence of enclothed cognition to be evident within athleisurewear consumers, where they are influenced to elicit behaviours and emotions of a fit-inspired lifestyle while wearing athleisurewear.

Further, we suggest that a need for sustainability is evident as existing literature suggests that the athleisurewear trend is expected to surpass all other forms of apparel in the following years and the fashion industry has already been identified as the second most polluting industry in the world. We also discuss that fashion consumers are a key motivator behind the sustainability initiatives within the fashion industry and the industry itself does not consider sustaining the environment as crucial. We further suggest that an opportunity may be found among athleisurewear consumers to tackle this issue due to their behavioural tendencies toward responsible consumption and their concern towards the social and ecological environment they live in, greater than any other segment of fashion consumers.

Limitation of the Review

This systematic review was limited to literature published in journal articles, conference papers, book chapters, a thesis, industry reports and online fashion blogs.

We also acknowledge the bias which could be in the theory of enclothed cognition put forward by Adam and Galinsky (Citation2012). The level of influence may vary from person to person and the behavioural tendencies may vary with external and internal forces of the social and ecological environment of the wearer. Hence, the occurrence of enclothed cognition may not be consistent.

Future Research Direction

We applied the theory of enclothed cognition put forward by Adam and Galinsky (Citation2012) and discussed the systematic influence athleisurewear has on the wearer’s psychological and behavioural tendencies to elicit behaviours and emotions of fitness and wellbeing. We further suggest that athleisurewear consumers might be a significant opportunity to achieve sufficient sustainable consumption levels within the fashion industry due to their higher levels of concern towards the environment than other types of fashion consumer and because athleisurewear is expected to grow significantly while surpassing other forms of apparel in production and consumption. Therefore, we suggest the following research directions:

Continuously update the athleisurewear systematic literature review from this paper to keep it current.

Develop hypotheses on athleisurewear consumers based on this paper and the theory of enclothed cognition by Adam and Galinsky (Citation2012).

Using this model as a theoretical framework, undertake a large-scale quantitative survey of athleisurewear consumers (informed by 1 and 2 above) to identify:

What motivates athleisurewear consumers to purchase athleisurewear, and

Whether, and if so, to what degree, athleisurewear consumers are influenced by athleisurewear garments to elicit behaviors of a fit-inspired lifestyle.

Whether, and if so, to what degree, athleisurewear consumers could be motivated to influence the fashion industry to better practice sustainability in manufacturing in order to mitigate environmental pollution and slow the effect of climatic change.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Himesh Perera

Himesh Perera is a PhD scholar at Swinburne University of Technology Australia, with a research focus on the fashion industry and circular economy. He is currently dedicated to transitioning the athleisurewear industry towards a circular economy to combat climate change. His work aims to develop sustainable solutions for the industry that will reduce waste and pollution while promoting economic growth. [email protected]

Lester W. Johnson

Lester W. Johnson is a professor in the School of Business, Law and Entrepreneurship at Swinburne University of Technology, Australia. His wide research interests lie in the empirical examination of business topics. In 2004 he was named one of three inaugural fellows of the Australia New Zealand Marketing Academy (ANZMAC) and was recently awarded an Order of Australian Medal (OAM) for services to tertiary education. [email protected]

Gordon E. Campbell

Gordon E. Campbell is a marketing lecturer at Swinburne University of Technology. He is a qualitative ethnographic researcher specialising in health behaviours and consumer behaviour, currently attached to the TITAN Project, a global collaboration investigating the effect of an immune-stimulating treatment drug targeting HIV. Prior to joining Swinburne, Gordon had an extensive career as a marketing executive with the Eastman Kodak Company. [email protected].

Jill Bamforth

Jill Bamforth is a management lecturer at Swinburne University of Technology. She has published in the areas of entrepreneurship and sustainability. More recently she has turned her attention to how organisations can build consumer trust. [email protected].

References

- Adam, H., and A. D. Galinsky. 2012. “Enclothed Cognition.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48 (4): 918–925. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.008.

- Australia Post. 2020. 2020 eCommerce Industry Report. https://auspost.com.au/content/dam/auspost_corp/media/documents/2020-ecommerce-industry-report.pdf.

- Australia Post. 2021. 2021 eCommerce Industry Report. https://auspost.com.au/content/dam/auspost_corp/media/documents/ecommerce-industry-report-2021.pdf.

- Barnard, M. 2002. Fashion as Communication. London: Routledge Publishing.

- Barsalou, L. W. 1999. “Perceptual Symbol Systems.” The Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22 (4): 577–609. doi:10.1017/s0140525x99002149.

- Barsalou, L. W. 2008. “Grounded Cognition.” Annual Review of Psychology 59: 617–645. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639.

- Basyah, J. 2020. “The History of Athleisurewear.” Crfashionbook. https://www.crfashionbook.com/fashion/a33323685/history-athleisure-sportswear-fashion/.

- Baumeister, R. F. 2013. “Writing a Literature Review.” In The Portable Mentor, 119–132. New York: Springer.

- Becker, S., A. Berg, S. Kohil, and A. Thiel. 2021. “Sporting Goods 2021: The Next Normal for an Industry in Flux.” Mckinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/sporting-goods-2021-the-next-normal-for-an-industry-in-flux.

- Becker-Leifhold, C. V. 2018. “The Role of Values in Collaborative Fashion Consumption: A Critical Investigation through the Lenses of the Theory of Planned Behaviour.” Journal of Cleaner Production 199: 781–791. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.296.

- Bianchi, C., and G. Birtwistle. 2010. “Sell, Give Away, or Donate: An Exploratory Study of Fashion Clothing Disposal Behaviour in Two Countries.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 20 (3): 353–368. doi:10.1080/09593969.2010.491213.

- Bianchi, F., P. Dupreelle, F. Krueger, J. Seara, D. Watten, and S. Willersdorf. 2020. “Fashion’s Big Reset.” Bcg. https://www.bcg.com/en-us/publications/2020/fashion-industry-reset-covid.

- Bloomberg, and Freund, J. 2020. “Lululemon Shares Hit an All-Time High on Strength of Work at Home Wear.” Fortune. https://fortune.com/2020/05/21/lululemon-stock-lulu-shares-all-time-high-coronavirus-work-at-home-clothing-athleisure-2020-covid-19/.

- Bringé, A. 2021. “The Rise of Athleisure in the Fashion Industry and What It Means for Brands.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescommunicationscouncil/2021/05/03/the-rise-of-athleisure-in-the-fashion-industry-and-what-it-means-for-brands/?sh=5ac9cb2b3ae0.

- Burns, D., M. Fox, E. L. Greenstein, M. Olbright, G, and Montgomery, D. 2019. “An Old Task in New Clothes: A Preregistered Direct Replication Attempt of Enclothed Cognition Effects on Stroop Performance.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 83: 150–156. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2018.10.001.

- Cataldo, Ilaria, Ilaria De Luca, Valentina Giorgetti, Dorotea Cicconcelli, Francesco Saverio Bersani, Claudio Imperatori, Samira Abdi, Attilio Negri, Gianluca Esposito, and Ornella Corazza. 2021. “Fitspiration on Social Media: Body-Image and Other Psychopathological Risks among Young Adults. A Narrative Review.” Emerging Trends in Drugs, Addictions, and Health 1: 100010. doi:10.1016/j.etdah.2021.100010.

- Chang, H., J. Yurchisin, J. Shin, and S. H. 2019. “An Examination of Elderly Female Consumers’ Body Shapes, Activewear Preferences and Exercise Behaviour.” Paper presented at the International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings.

- Clarke-Sather, A., and K. Cobb. 2019. “Onshoring Fashion: Worker Sustainability Impacts of Global and Local Apparel Production.” Journal of Cleaner Production 208: 1206–1218. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.073.

- Cook, D. J., C. D. Mulrow, and R. B. Haynes. 1997. “Systematic Reviews: Synthesis of Best Evidence for Clinical Decisions.” Annals of Internal Medicine 126 (5): 376–380. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-126-5-199703010-00006.

- Diddi, S., Yan, R. N. Bloodhart, B. Bajtelsmit, V, and McShane, K. 2019. “Exploring Young Adult Consumers’ Sustainable Clothing Consumption Intention-Behaviour Gap: A Behavioural Reasoning Theory Perspective.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 18: 200–209. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2019.02.009.

- dos Reis, B. M., L. S. Ribeiro, R. A. L. Miguel, J. M. Lucas, M. M. R. Pereira, J. Carvalho, and M. J. dos Santos Silva. 2018. “Sustainable Consumption of Fashion Leisure Products: Wool Fabrics and Lifestyle.” Paper presented at the Global Fashion Conference Proceedings.

- Dwivedi, Y. K., N. P. Rana, H. Chen, and M. D. Williams. 2011. “A Meta-Analysis of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology.” Paper presented at the International Working Conference on Governance and Sustainability in Information systems. Managing the transfer and diffusion of it.

- Entwistle, J. 2000. “Fashion and the Fleshy Body: Dress as Embodied Practice.” Fashion Theory 4 (3): 323–347. doi:10.2752/136270400778995471.

- Fact.MR. 2020. “Functional Workwear Apparel Market Forecast, Trend Analysis & Competition Tracking - Global Market Insights 2020 to 2030.” Fact.MR. https://www.factmr.com/report/338/functional-workwear-apparel-market.

- Forman, L., and J. Lee. 2020. “Lululemon’s Surge Could Have Long Legs; Shares of the Athleisure Retailer Should Continue to be a Relatively Accessible Beneficiary of the At-Home Fitness Trend Amid the Pandemic.” The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/lululemons-surge-could-have-long-legs-11589470142.

- Ganak, J., L. Summers, O. Adesanya, T. Chi, and Y. N. Tai. 2019. “The Future of Fashion Sustainability: A Qualitative Study on U.S. Female Millennials’ Purchase Intention towards Sustainable Synthetic Athleisure Apparel.” Paper presented at the International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings.

- Glenberg, A. M. 1997. “What Memory is For.” The Behavioral and Brain Sciences 20 (1): 1–55. doi:10.1017/s0140525x97000010.

- Gosselin, V. 2020. “Athleisurewear: A Trend Movement in the Fashion and Sportswear Industries.” Heuritech. https://www.heuritech.com/articles/trends/athleisure-wear/.

- Grant, M. J., and A. Booth. 2009. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information and Libraries Journal 26 (2): 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

- Grappi, S., S. Romani, and C. Barbarossa. 2017. “Fashion without Pollution: How Consumers Evaluate Brands after an NGO Campaign Aimed at Reducing Toxic Chemicals in the Fashion Industry.” Journal of Cleaner Production 149: 1164–1173. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.183.

- Griffiths, S., and A. Stefanovski. 2019. “Thinspiration and Fitspiration in Everyday Life: An Experience Sampling Study.” Body Image 30: 135–144. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.07.002.

- Griffiths, S., D. Castle, M. Cunningham, S. B. Murray, B. Bastian, and F. K. Barlow. 2018. “How Does Exposure to Thinspiration and Fitspiration Relate to Symptom Severity among Individuals with Eating Disorders? Evaluation of a Proposed Model.” Body Image 27: 187–195. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.10.002.

- Guzzetta, M. 2022. “Athleisure Used to Be Just an Outfit. Here’s How It Became a Lifestyle.” Inc. https://www.inc.com/magazine/201906/marli-guzzetta/athleisure-athletic-wear-clothing-apparel-brands-tracksuit-yoga-pants.html.

- Huang, L., A. D. Galinsky, D. H. Gruenfeld, and L. E. Guillory. 2011. “Powerful Postures versus Powerful Roles: Which is the Proximate Correlate of Thought and Behavior?” Psychological Science 22 (1): 95–102. doi:10.1177/0956797610391912.

- Hwang, J., and M. A. Griffiths. 2017. “Share More, Drive Less: Millennials Value Perception and Behavioural Intent in Using Collaborative Consumption Services.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 34 (2): 132–146. doi:10.1108/JCM-10-2015-1560.

- IMDB. 2022. “What Not to Wear.” IMDB. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0393009/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0.

- Jensen, A. R. 1965. “Scoring the Stroop Test.” Acta Psychologica 24 (5): 398–408. doi:10.1016/0001-6918(65)90024-7.

- Jong, S., and T. Drummond, M. J. N. 2016. “Exploring Online Fitness Culture and Young Females.” Leisure Studies 35 (6): 758–770. doi:10.1080/02614367.2016.1182202.

- Kim, C. S., B. H. Bai, P. B. Kim, and K. Chon. 2018. “Review of Reviews: A Systematic Analysis of Review Papers in the Hospitality and Tourism Literature.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 70: 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.023.

- Kim, S. N., H. J. Jung, and K. W. Oh. 2017. “The Effects of Lifestyles on Pursuing Benefits and Purchase Intention of Athleisure Wear.” Fashion & Textile Research Journal 19 (6): 723–735. doi:10.5805/SFTI.2017.19.6.723.

- Kozar, J., and M. Hiller, C. K. Y. 2013. “Socially and Environmentally Responsible Apparel Consumption: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours.” Social Responsibility Journal 9 (2): 315–324. doi:10.1108/SRJ-09-2011-0076.

- Lam, H. Y., Y. Yurchisin, S. C. Cook. 2016. “Young Adults’ Ethical Reasoning Concerning Fast Fashion Retailers.” Paper presented at the International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings.

- Lee, K., and E. Sanders, E. A. 2016. “Hanji, the Mulberry Paper Yarn, Rejuvenates Nature and the Sustainable Fashion Industry of Korea.” Green Fashion 1: 159–184.

- Lexico. 2022. “Oxford English and Spanish Dictionary, Synonyms, and Spanish to English Translator.” Lexico. https://www.lexico.com/.

- Liljenquist, K., Zhong, C. B. Galinsky, and A. D. 2010. “The Smell of Virtue: Clean Scents Promote Reciprocity and Charity.” Psychological Science 21 (3): 381–383. doi:10.1177/0956797610361426.

- Lipson, S., M. Stewart, S, and Griffiths, S. 2020. “Athleisure: A Qualitative Investigation of a Multi-Billion-Dollar Clothing Trend.” Body Image 32: 5–13. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.10.009.

- Liu, N. 2020. Activewear Designs and Innovations. Latest Material and Technological Developments for Activewear. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing.

- Lyu, S. 2018. “Athleisure Hanbok.” Paper presented at the International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings.

- Merriam-Webster. 2022. “The ‘Athleisure’ Trend. Athleisure: Words We’re Watching.” https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/athleisure-words-were-watching.

- Molly, J. T. 1988. Dress for Success. New York: Peter H., Wyden Publishing.

- Moretto, A., L. Macchion, A. Lion, F. Caniato, P. Danese, and A. Vinelli. 2018. “Designing a Roadmap towards a Sustainable Supply Chain: A Focus on the Fashion Industry.” Journal of Cleaner Production 193: 169–184. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.273.

- Nation’s Business. 1979. Nation’s Business: A General Magazine for Businessmen. Vol. 1, Wilmington, NC: Published Collections Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Chamber of Commerce of the United States, 42–44.

- Niedenthal, P., M. Barsalou, L. W. Winkielman, P. Krauth-Gruber, S, and Ric, F. 2005. “Embodiment in Attitudes, Social Perception, and Emotion.” Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc 9 (3): 184–211. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_1.

- Niinimäki, K., and L. Hassi. 2011. “Emerging Design Strategies in Sustainable Production and Consumption of Textiles and Clothing.” Journal of Cleaner Production 19: 1876–1883. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.04.020.

- Paez, A. 2017. “Gray Literature: An Important Resource in Systematic Reviews.” Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 10 (3): 233–240. doi:10.1111/jebm.12266.

- Pahlevan-Sharif, S., P. Mura, and S. N. R. Wijesinghe. 2019. “A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews in Tourism.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 39: 158–165. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.04.001.

- Patrick, K., and Y. Xu. 2018. “Exploring Generation Y Consumers’ Fitness Clothing Consumption: A Means-End Chain Approach.” Journal of Textile and Apparel, Technology and Management 10: 1–15.

- Petriccione, A. 2018. “Fashion vs. Function: A Look at New Opportunities for Fashionable and Functional Travel Wear.” Advertising & Society Quarterly 19 (3). doi:10.1353/asr.2018.0029.

- Poplin, C. 2020. “Fashion History Lesson: The Origins, and Explosive Growth of Athleisure.” Fashionista. https://fashionista.com/2020/01/the-history-of-athleisure.

- Ritch, E. L. 2015. “Consumers Interpreting Sustainability: Moving beyond Food to Fashion.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 16: 193–215.

- Roncha, A., and N. Radclyffe-Thomas. 2016. “How TOMS ‘One Day without Shoes’ Campaign Brings Stakeholders Together and co-Creates Value for the Brand Using Instagram as a Platform.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 20 (3): 300–321. doi:10.1108/JFMM-10-2015-0082.

- Salfino, C. 2020. “Why Growth in Athleisure is the Pandemic’s Silver Lining.” Sourcing Journal. https://sourcingjournal.com/topics/lifestyle-monitor/coronavirus-athleisure-bcg-klaviyo-american-eagle-offline-aerie-npd-226232/.

- Salpini, C. 2018. “The State of Sports Retail: How Athleisure Keeps Changing the Game.” Retail Dive. https://www.retaildive.com/news/the-state-of-sports-retail-how-athleisure-keeps-changing-the-game/518126/.

- Sarkar, P. 2020. “Difference between Activewear and Athleisure.” Online Clothing Study. https://www.onlineclothingstudy.com/2017/11/difference-between-activewear-and.html#:∼:text=Activewear%20is%20casual%2C%20comfortable%20clothing,perfect%20for%20travelling%20and%20walking.

- Schnall, S., J. Benton, and S. Harvey. 2008. “With a Clean Conscience: Cleanliness Reduces the Severity of Moral Judgments.” Psychological Science 19 (12): 1219–1222. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02227.x.

- Sorensen, K., and J. J. Jorgensen. 2019. “Millennial Perceptions of Fast Fashion and Second-Hand Clothing: An Exploration of Clothing Preferences Using Q Methodology.” Social Sciences 8 (9): 244. doi:10.3390/socsci8090244.

- Tascperformance. 2022. “When Did the Athleisure Trend Start?” Tascperformace. https://www.tascperformance.com/blogs/articles/when-did-the-athleisure-trend-start.

- Thompson, D. 2018. “Everything You Wear is Athleisure.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/10/bicycle-bloomers-yoga-pants-how-sports-shaped-modern-fashion/574081/.

- Todeschini, B., V. Cortimiglia, M. N. De Medeiros, and J. F. 2020. “Collaboration Practices in the Fashion Industry: Environmentally Sustainable Innovations in the Value Chain.” Environmental Science & Policy 106: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2020.01.003.

- Tokatli, N. 2007. “Global Sourcing: Insights from the Global Clothing Industry: The Case of Zara, a Fast Fashion Retailer.” Journal of Economic Geography 8 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbm035.

- Tolliver, C., A. R. Keeley, and S. Managi. 2020. “Drivers of Green Bond Market Growth: The Importance of Nationally Determined Contributions to the Paris Agreement and Implications for Sustainability.” Journal of Cleaner Production 244: 118643. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118643.

- Vaterlaus, J., M. Patten, E. V. Roche, C. Young, and J. A. 2015. “#Gettinghealthy: The Perceived Influence of Social Media on Young Adult Health Behaviors.” Computers in Human Behavior 45: 151–157. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.013.

- Watts, L., and T. Chi. 2019. “Key Factors Influencing the Purchase Intention of Activewear: An Empirical Study of US Consumers.” International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 12 (1): 46–55. doi:10.1080/17543266.2018.1477995.

- Weibe, J. 2013. “Psychology of Lululemon: How Fashion Affects Fitness.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/12/psychology-of-lululemon-how-fashion-affects-fitness/281959/.

- Wells, G., and L. Petty, R. E. 1980. “The Effects of Overt Head Movements on Persuasion: Compatibility and Incompatibility of Responses.” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 1 (3): 219–230. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp0103_2.

- Williams, L., and E. Bargh, J. A. 2008. “Experiencing Physical Warmth Promotes Interpersonal Warmth.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 322 (5901): 606–607. doi:10.1126/science.1162548.

- Wilson, C. 2018. “Why the Word ‘Athleisure’ is Completely Misunderstood.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/chipwilson/2018/04/18/why-the-word-athleisure-is-completely-misunderstood/?sh=d2fbcfa46971.

- Wilson, E. 2003. Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Yan, S., Henninger, C. E. Jones, C, and McCormick, H. 2020. “Sustainable Knowledge from Consumer Perspective Addressing Microfibre Pollution.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 24 (3): 437–454. doi:10.1108/JFMM-08-2019-0181.

- Zhong, C., and B. Liljenquist, K. 2006. “Washing Away Your Sins: Threatened Morality and Physical Cleansing.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 313 (5792): 1451–1452. doi:10.1126/science.1130726.