ABSTRACT

Widespread concerns around the privacy impact of online technologies have corresponded with the rise of fly-on-the-wall television documentaries and public-by-default social media forums allowing parallel commentary. Although information about children has traditionally been regarded by society, law and regulation as deserving of particular protection, popular documentaries such as Channel 4′s ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 year olds’ raise questions as to whether such protections are being deliberately or inadvertently eroded in this technological ‘always-on’ online age. The article first describes the documentary series and the results of an analysis of related Twitter interaction. It considers responses to freedom of information requests sent to the public bodies involved in the series with the aim of establishing the ethical considerations given to the involvement of the children. The paper goes on to explore the privacy law context; the wider child law issues, the position of parents/carers and the impact of broadcast codes. It considers if lessons can be learned from how decisions in the medical context have dealt with issues of best interests in decision-making and in disclosure of information concerning the child. The paper concludes that additional legal and ethical safeguards are needed to ensure that the best interests of children are properly considered when images and information are exposed on broadcast and social media.

Introduction

‘Generation Z’ is a term used to categorise young people who have grown up with technology and the Internet, and who regard the use of social media websites as an integral part of their private and social lives. In this article, we are concerned with the youngest members of Generation Z who, although often very adept at using technology, may have little awareness of the impact of social media on their privacy. They can appear on social media because of the actions of others, such as parents posting photographs on a Facebook or Instagram page, or even opening a Twitter account for their baby.Footnote1 Where young children feature in fly-on-the-wall reality documentaries on broadcast media, however, they risk becoming the target of comment on social media outside of their immediate friends and family. This content is discoverable long after the original broadcast. We refer to them as ‘Generation Tagged’.

Over the last five to six years,Footnote2 hashtagsFootnote3 have been used increasingly by broadcasters in conjunction with television programmes as a way of encouraging interactive tweeting during broadcast (and thus an increase in viewer numbers and advertising revenue). Channel 4, for instance, used a hashtag in the series ‘The Undateables’, a reality programme which filmed adults with disabilities or learning difficulties as they went on dates. Recently, reality programmes have begun to feature ever younger children, sometimes under the mantle of behavioural advice or social experimentation, examples being ‘Boys and Girls Alone’,Footnote4 ‘Three Day Nanny’,Footnote5 ‘My Violent Child’,Footnote6 ‘Born Naughty?’Footnote7 and ‘Child Genius’ (criticised for the close-up filming of a child in tears).Footnote8 These programmes typically publish hashtags on the screen to encourage associated conversation on Twitter.

This type of programming has become so ubiquitous in such a relatively short period of time that one has to ask whether society is at risk of embedding a new privacy-intrusive norm. The associated legal and ethical governance framework has yet to catch up with an environment in which child welfare considerations applicable in ‘real-world’ care, education and medical environments are apparently easily overcome in the world of broadcast programming and related social media. As Townend has argued, there is now ‘less distance between producers, contributors and consumers of media, as categories become harder to distinguish’.Footnote9 Barendt comments that ‘[o]nline communication tends to permanence … so these communications are more likely to be seen by the public … and for a longer time, than similar communications in the traditional media’.Footnote10 Whilst it may be possible to judge the privacy impact at the point of publication/broadcast, harm may be caused in years to come, and that harm may alter in nature. We argue that there is a need for change, in the law, governance processes or both, in order to ensure that the interests of the child are better represented.

In order to consider these issues, we examine the documentary series ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds’, an example of the public depiction of young children alongside scientific and medical commentary designed for popular appeal. In addition, it encourages real-time interaction over Twitter by the publication of a hashtag. We describe the series and the results of an analysis of related Twitter interaction. Responses to freedom of information requests submitted to the university and health bodies which employed the scientists involved in the series, and to Channel 4 itself, are examined and the relevant sections of the broadcasting code explained. We review the position of children under data protection and privacy law, in the wider context of child law and under the broadcasting codes, in order to consider the effectiveness of these protections in relation to the series. We consider if lessons can be learnt from how decisions in the medical context have dealt with decision-making and disclosure of information in the child's best interests. Finally, the article suggests that additional legal and ethical safeguards are needed to ensure that the best interests of ‘Generation Tagged’ are properly considered when images and information are broadcast and exposed on social media.

The series

Channel 4 is a not-for-profit public service broadcaster in the UK and ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds’ is one of its highest-rated documentary series. In it, a number of specially selected children were brought together in a ‘rigged’ school and their interactions and behaviour filmed. Channel 4 refers to the series as ‘eavesdropping’ on the children's ‘secret world’.Footnote11 During broadcast, members of the watching public were encouraged to comment on the programme on Twitter using hashtags provided by Channel 4, such as #SLO5YO. On-screen commentary was provided by three scientistsFootnote12 who were watching and listening to the activities as they happened. Comments were made about the character types of the individual children, advice offered as to what certain children may need to do to change their behaviour, and reactions of amusement shown at the children's antics. It should be noted that this article makes no judgement on or criticism of the particular work of the scientists involved.

The programme categorises itself as ‘Science Entertainment’Footnote13 and it has to be said that some of the programme summaries have a tendency to read like soap opera plots.Footnote14 Indeed, Channel 4 describes the programme as lifting the lid ‘on the riveting, uncensored drama of life in the nursery’.Footnote15 The programme makers also emphasise the scientific aspects however, with the Wellcome TrustFootnote16 having provided a grant to the production company ‘to make the science and scientists an integral part of the format’.Footnote17 The series incorporated observations and scientific ‘tests’ designed by the production company with the help of the three scientists, who were described as being ‘embedded’ in the process of creating the programme and as observing the children's behaviour and developmental milestones.Footnote18 Remotely operated cameras were installed at the children's eye-level allowing close-ups of expressions, including those of happiness, distress, tears and strong affections, and each child was wired to a mic. This enabled the programme makers to observe the children in a detailed and constant manner:

The joy of the fixed rig [a network of robotic cameras installed in a location] is the intimacy of the footage it captures, and for us the key to this was the sound. Each of the children is wired up with a microphone and they remain on this same mic throughout their time with us. This means we can tune into every child at any time. And so can the scientists. We capture every word uttered, whispered or gasped – nothing passes undetected. This is what gives us such a privileged and unparalleled window onto their secret world including the unadulterated and innocent humour that this allows us to capture.Footnote19

The programme makers assert that any difficult behaviour was shown in context, never in a gratuitous manner and only if pertinent to ‘the story of the week’.Footnote21 It was however an expressed aim of the programme to show strong emotions:

We all have a bit of the devil in us and any parent knows their child isn’t angelic all the time. A really important aspect of the programme is showing the realities of life in the playground – it can be brutal out there – and there's no shame in feeling things strongly. Let's be clear, we're talking universal emotions here. Which of us hasn't experienced jealous rage, rejection, or the sting of criticism? These are not the preserve of children and its amazing how recognisable these emotions are to us when they are laid bare, uncensored and uncomplicated by layers of politeness and so-called manners.Footnote22

It has been reported that the series was inspired by the Bing Nursery at Stanford University,Footnote24 which provides a laboratory setting for faculty members to conduct research in child development. The news report went on to note however that ‘to adopt the idea for TV, though – as mere entertainment – was, and still is, a controversial one’.Footnote25

Twitter interaction

An important element of the programme's format, as is common with many television programmes in recent years, was the publication of a hashtag to enable the watching public to make real-time comments and engage in conversations about the programme's content. We undertook an informal empirical analysis of tweets (which may contain a margin of error) using Twitter's advanced search functionality to narrow down the tweets to the relevant hashtag (#SLO4YO, #SLO5YO, #SLO6YO) on the day of the broadcast, limiting the results to English-language only. We classified tweets as positive or negative, and those revealing personal data about the children. Negative tweets were located manually, and only negative tweets about the children themselves were counted (tweets negative about the programme itself, or the adults present on it, were ignored). We defined a negative tweet as one that discussed the children using expletives in a negative way, called them ‘annoying’ or used similar terms, or made assumptions about their future in a negative fashion. We classified a revealing tweet as one from any person that identified the child directly or indirectly, and revealed more information than was already present in the series. (Parents tweeting about their children in this way typically would reveal the surname of the child, where they lived and sometimes photos.)

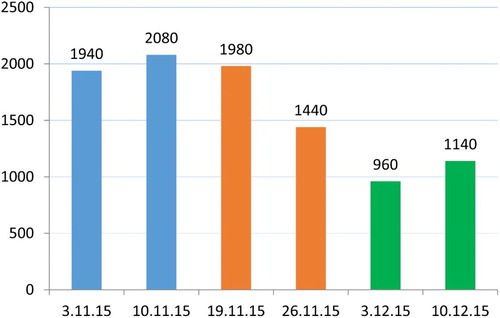

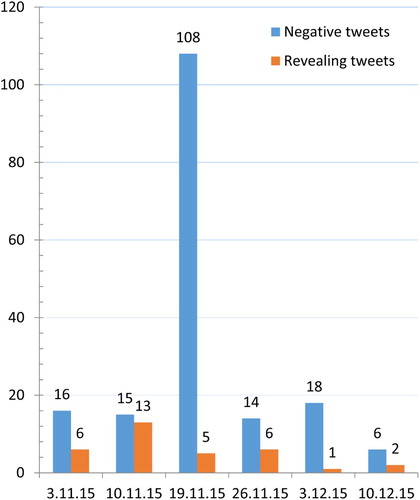

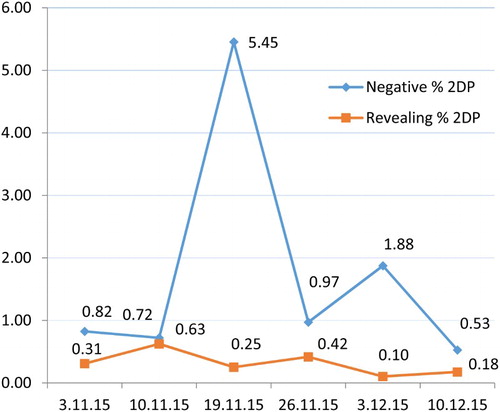

The results of the analysis are set out below. presents an overview of the data collected: the date of the relevant broadcast; the age group of the children featured; approximate number of tweets; numbers and percentages of negative and revealing tweets. These results are broken down in the subsequent tables. illustrates the total number of tweets analysed, and and indicate the numbers of negative and revealing tweets on the specified dates.

Table 1. Data overview

This analysis revealed that the percentage of negative and revealing tweets was small, ranging from 0.53 to 5.45% for negative tweets, and 0.10 to 0.63% for revealing tweets. It should be noted however that the episode broadcast on 19 November 2015 resulted in a significant increase in negative tweets (5.45%) aimed at two of the children in particular. This episode focused on the often fractious interactions between certain children. It included background family information (which may have been edited provocatively) likely to have stimulated negative comment, and a cake experiment which included gender comparisons. It can be speculated that the nature of these subject matters could have been a significant factor in generating the relatively large number of negative tweets.

In addition, although the percentage of negative tweets was small, the nature of some tweets could be regarded as potentially harmful to the privacy and dignity of the children as the following selection may demonstrate:

‘[ ] is a bully. Her mum really needs to learn some parenting skills.’ [19/11/2015]

‘I’m sorry but [ ]’s parents clearly need to do a better job. Never genuinely found a child to be so horrid and so young too.’ [19/11/2015]

‘Has no one identified that little boy as having autism? Seriously?’ [26/11/2015]

‘This [ ] is a fucking bitch, 5 or not’ [26/11/2015]

Revealing tweets were typically from proud parents or friends with little indication in them of malicious disclosure of personal information. Although revealing tweets were less than 1% of the total number of tweets using the hashtag on each date analysed, these tweets received a much higher number of ‘re-tweets’ than normal, so were likely to have had a much greater spread that their frequency would imply. This suggests that tweets containing personal information about the children featured in the series were of particular interest to Twitter users who were tracking the programme's hashtag.

The freedom of information requests

Background

Pursuant to the UK's Freedom of Information Act 2000, freedom of information requests were submitted to the university and health bodies which employed the scientists involved in the programme, and to Channel 4 itself. The aim of these requests was to ascertain what process of ethical consideration had been conducted under the institution's policies in relation to the research elements of the series and the involvement of the children, and in the case of Channel 4, how compliance with the UK broadcasting regulator's (Ofcom) Broadcasting Code in relation to the involvement of under 18s in programmes had been achieved.Footnote26

Ofcom's Guidance makes clear that broadcasters' obligations under the rules apply irrespective of parental consent.Footnote27 Parents ‘may only be able to see what they perceive to be the benefits of their child taking part in a programme, rather than any potential negative outcomes’.Footnote28 The Guidance notes that although young children may be able to indicate willingness (assent) to participate, they may not be able to put anxieties or uncertainties into words and may find it difficult to contradict an adult's suggestion to participate.Footnote29 Emphasis is given to the potential need for the involvement of experts to advise on the suitability of a child for inclusion in the programme and the impact of the ongoing production process.Footnote30

The Guidance also points out that a potential negative impact of participation is the social media and media attention that may be generated. Broadcasters are advised to consider the risks of bullying (including online bullying) and to give guidance on privacy settings on social media sites.Footnote31

Section 8 of the Ofcom Code relates to privacy, with rule 8.1 stating that any privacy infringement must be ‘warranted’: if the reason that the broadcaster believes the infringement is warranted relates to the public interest, ‘then the broadcaster should be able to demonstrate that the public interest outweighs the right to privacy’.Footnote32

A request for information was also sent to the Wellcome Trust (a charity not covered by the 2000 Act) but no response was received. No request was sent to the commercial production company, RDF Television, on the basis that Channel 4 remains responsible for compliance of its programmes with the broadcast code, whether or not made by it.

The responses

All three health and university bodies sent ‘information not held’ responses. This was on the basis that no ethics committees or similar had considered the involvement of the staff or children in the series, because the work had been done outside normal working time and/or the data associated with the series had not been accessed by the institution for research purposes.

Channel 4 refused the request and upheld the refusal after a request for internal review, relying on the so-called journalistic designation. Part VI of Schedule 1 to the 2000 Act states that the definition of a public authority which owes a duty of disclosure under the Act includes ‘The Channel Four Television Corporation, in respect of information held for purposes other than those of journalism, art or literature’ . The derogation in this Part has been interpreted widely, as confirmed by the Supreme Court in Sugar, and means that information held by Channel 4 for the purposes of journalism and creative output, even if also held for other purposes, is effectively exempt from disclosure under the Act.Footnote33 In its internal review response however, Channel 4 volunteered the statement that ‘we can confirm that the programme complied with Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code in addition to our own internal guidelines’.Footnote34 Channel 4′s own guidelines mirror and expand upon the Ofcom's guidelines and also state that, even if it is agreed that a child and his/her family can view a programme before transmission, editorial control will rest with Channel 4.Footnote35

As mentioned above, some information is provided on Channel 4′s website regarding the recruitment of the children (stated to involve a child psychologist) and the process of consent. Due to the exclusion of this area of Channel 4′s remit from the Freedom of Information Act however, it would not generally be possible to obtain further details regarding the methods used to comply with the codes, nor does the website indicate the potential for any concerns regarding the impact of comments on social media. It is of concern that the children's recruitment process was described by the production company as ‘casting’;Footnote36 although a colloquial term used to describe the process of deciding upon the right participants, it would seem to contrast (negatively we would argue) with the processes required for the recruitment of subjects in a scientific or medical context.

Further to the freedom of information requests, the authors were able to enter into direct correspondence with Channel 4 which volunteered a number of comments on an earlier draft of this article. Regarding compliance with Rules 1.28 and 1.29 of the Ofcom Code (which require due care to be taken for physical and emotional welfare and dignity of children irrespective of parental consent and that children must not be caused unnecessary anxiety or distress), Channel 4 said:

One of the ways [Channel 4] meets this obligation is to rely on, variously depending the circumstances, the individual and collective experience/expertise of scientists, the children’s teachers, GPs, chaperones, programme makers, commissioners and lawyers but also to engage, where appropriate, the services of appropriately qualified and experienced independent experts, and, in this case, expert child/family psychologists. If, in the view of an independent expert, it would not be appropriate to proceed with (or to continue to proceed with) a particular child contributor (and there may be many reasons for this) then we simply would not do so. Nor would we broadcast material if there was any real concern that doing so could result in harm to a child (now or in the future). While Channel 4 must retain editorial control the key to the success of this programme (and indeed others involving children) is that the process is consensual.Footnote37

Children, data protection and privacy

Data protection

Neither the UK's Data Protection ActFootnote39 nor the EU Data Protection DirectiveFootnote40 contains any specific provisions about the collection or processing of children's personal data. The new EU General Data Protection Regulation, once in force in 2018, will change the position somewhat.Footnote41 The Recitals to the Regulation state:

Children merit specific protection with regard to their personal data, as they may be less aware of the risks, consequences and safeguards concerned and their rights in relation to the processing of personal data. Such specific protection should, in particular, apply to the use of personal data of children for the purposes of marketing or creating personality or user profiles and the collection of personal data with regard to children when using services offered directly to a child.Footnote42

Article 8 of the Regulation requires that where ‘information society services’ (such as social networking sites) are being offered directly to a child, the processing of personal data of a child under the age of 16 shall be lawful only if consent has been given by those holding parental responsibility for the child. Member states are allowed to lower this threshold but not below 13.

Children's personal data has been ‘processed’ in a number of different ways due to their involvement with the ‘Secret Life’ series: by the production company in the selection process and the making of the programme; by the scientists involved in the commentary; by Channel 4, including by posting identifiable information on its website; by some parents when posting about their children on social media; potentially by other users of social media when commenting upon particular children; by social media companies providing the means for the commentary.

The Regulation does not appear to provide ‘Generation Tagged’ with significantly increased protection. We are not concerned with children who are old enough to take up online services offered directly to them (so falling under Article 8). As data protection laws before it have done, the Regulation continues to focus on valid consent for personal data processing, which in the case of the processing of personal data about a young child lacking capacity in connection with the filming and broadcast of reality television, will be the consent of the parent. The Ofcom code points out that parents may not have a full understanding of the short- and longer-term implications of their child's involvement. Data protection law could in any event be seen as a sub-set of privacy, and is often criticised for being a piece of technical legislation ‘more about the regulation of data flow than the protection of individuals’ privacy’.Footnote43 Provided consent has been given, data protection tells us little about whether the data processing should have happened. This highlights the need for society to decide how far it is acceptable for private moments from a child's life to become entertainment, and regulate accordingly.

In the future under the new Regulation, a child could attempt to exercise her ‘right to be forgotten’Footnote44 on the basis that she objects to future processing of her personal data or has withdrawn her consent, such as it was. How effective this would be against a volume social media provider such as Twitter, or in respect of the series itself, potentially still available on an on-demand service, remains to be seen. The original broadcaster may well raise a public interest justification for continued processing. It could be argued, in respect of tweets such as those set out above, that Twitter is not processing personal data at all, although if a risk of jigsaw identification could be shown (identification by piecing together information available on the Internet and from other sources), the definition of personal data in s1(1) of the Data Protection Act and also in article 4(1) of the new Regulation may well be satisfied. In any event, it is unclear what action Twitter could be forced to take; blocking searches on the child's name, deleting tweets mentioning the child and even blocking links to the series would all be possible but not necessarily sufficient to remove all copies of the information concerned. It is also unclear when a child could exercise their ‘right to be forgotten’ independently: as a teenager; when ‘competent’; at a certain age? The Regulation gives little guidance, merely stating that the right

is relevant in particular where the data subject has given his or her consent as a child and is not fully aware of the risks involved by the processing, and later wants to remove such personal data, especially on the internet.Footnote45

Privacy law

It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the many suggested definitions of privacy.Footnote51 Lipton has summarised the various definitions as a quasi-property right, a right related to personal autonomy, a right related to protection of one's identity, and a right related to bodily integrity.Footnote52 Yet privacy harms are difficult to determine and quantify: what damage has or might a child suffer from his or her depiction on ‘The Secret Life of 5 Year Olds’ or from comments made on social media, especially if he or she is unaware at the time? Channel 4 appear to claim in its direct comments on an earlier draft of this article that no real harm has occurred, or can occur, to a child featured in the series. However, as is explored below, children have distinct rights to respect for their privacy, irrespective of whether or not they were aware of an intrusion. The very nature of fly-on-the-wall reality programmes has the potential to create such intrusion. Recent media reporting has also indicated parental concern about ‘inaccurate’ editing of Child GeniusFootnote53 and regarding ‘nasty things’ written on Twitter in association with the broadcast of ‘The Secret Life of 5 Year Olds’.Footnote54

This section focuses upon misuse of private information (which was confirmed to be a tort in England and Wales by Tugendhat J in Vidal-Hall).Footnote55 The impact of privacy concerns in the context of child and medical law are explored in later sections. There is no tort that recognises a right to privacy in all respects. The tort in question protects ‘the right to control the dissemination of information about one’s private life’.Footnote56 The decision in Weller Footnote57 involved the publication by the Mail Online in the UK of un-pixelated photographs of the children of famous musician Paul Weller, twins aged 10 months and another child aged 16. The photographs showed the family engaged in everyday activities in a public place – shopping and sitting in a café – in Los Angeles. Dingemans J held, applying the grounds laid out in Murray,Footnote58 that there was a reasonable expectation of privacy; the photographs showed the emotions on the children's faces while on a family outing, ‘one of the chief attributes of their respective personalities’,Footnote59 and the newspaper knew that the photographs had been taken without parental consent. In terms of the balance between the children's Article 8 rights and the newspaper's rights to freedom of expression under Article 10, the judge came down in favour of the children, concluding that the publication of the photographs did not contribute to a debate of general interest.

In upholding the judgment and dismissing the Mail's appeal,Footnote60 Lord Dyson MR made the following points regarding children and the reasonable expectation of privacy:

a child does not have a separate right to privacy merely by virtue of being a child;Footnote61

in determining whether a child has a reasonable expectation of privacy, the factors listed at paragraph 36 of Murray – attributes of the claimant including age; the nature of the activity and where it happened; the nature and purpose of the intrusion; consent; and effect on the claimant – are relevant;Footnote62

in relation to a child too young to have an idea of privacy, the behaviour of the parents, and how they chose to conduct their family life, steps in as a factor;Footnote63

the parents' lack of consent will carry particular weight;Footnote64

the effect on a child cannot be limited to whether the child was physically aware of the photograph being taken or whether the child is personally affected by it;Footnote65

in determining whether a child's Article 8 rights are engaged, the court is required to accord primacy to a child's best interests.Footnote66

It is initially difficult to see any read-across from Weller to the position of the children in series such as ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds’. Although Weller determined that a child need not be aware of the privacy intrusion in order to succeed in a claim, the children featured in the series did participate with their parents' consent. In AAA, the child claimant's reasonable expectation of privacy was accorded less weight because of the mother's actions in putting certain information into the public domain.Footnote69 That case contrasts with both Murray and Weller, where both sets of parents had taken considerable steps to keep their children out of the limelight. Although the Court of Appeal in Murray accepted that children have rights to respect for their privacy distinct from that of their parents, and that the law should protect children from intrusive media attention, the extent of this protection may depend on whether such intrusion is objected to ‘on behalf of the child’.Footnote70 As Hancock argues, ‘Potentially the greatest threat to a child’s privacy can come from their own parents, able to sacrifice the rights of their children.’Footnote71 Therefore, it could even be the case that ‘Generation Tagged’ would be regarded as having no reasonable expectation of privacy at all because of the actions of others.

This would be a concerning outcome for society. ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds’ depicts a range of emotions and expressions in a much more comprehensive way than a single photograph. Many of the situations exposed in the series would be regarded by adults as intensely personal: expressions of love; kisses; grief. The comments made about the children's characters and how their behaviour should change would, in a medical or educational context, be subject to degrees of confidentiality. By publication of a hashtag, it would be reasonable to assume that some negative comment would result (as it did) which could adversely affect the privacy and dignity of the child, particularly as the information released about the children and the families creates a risk of jigsaw identification. In addition, what harm might occur if, for instance, a future employer sees that as a child, a job applicant was regarded as autistic or a bully? It may be too early to say. As Lipton has observed:

The Internet fundamentally challenges our perspectives on social, political, and economic behaviors every decade or so. Each shift requires decision makers to re-think basic assumptions about human interaction within progressively shorter timeframes.Footnote72

The wider child law context, the position of parents/carers and the protection of children in the broadcast media

We consider in this section the reasonable expectation of privacy as it relates to ‘Generation Tagged’ and question whether relying on parental consent can continue to be a fair and ethical way of protecting the best interests of the child when material on the Internet may have a long term effect i.e. beyond the age that the child becomes an adult.

A brief introduction to the wider child law context

The existing children’s rights framework in English law is not well equipped to protect children who are at risk of, or who have had, their privacy infringed by social or broadcast media or a mixture of the two. Children’s rights disputes in English law commonly feature a conflict between children's rights to autonomy and their rights to protection. Hence the framework is depicted by a clash between rights and welfare.Footnote76 In English law, children's autonomy rights have mainly been explored in the context of medical treatment. The leading case on children's rights, Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech AHA,Footnote77 established that the ‘parental right yields to the child’s right to make his own decisions when he reaches a sufficient understanding and intelligence to be capable of making up his own mind on the matter requiring decision’.Footnote78 The case therefore made it possible for under-16-year-olds to consent to medical treatment without needing to involve their parents.

Since Gillick, the autonomy interest of the child has been at the forefront of many legal, political and social debates, especially in relation to older children, who are considered to be Gillick-competent. In the medical context, the views of an under-16-year-old are given due weight if they are deemed to be Gillick-competent. Confidentiality has also has become increasingly respected as a result of Gillick and also re-emphasised by R (on the application of Axon) v Secretary of State for Health.Footnote79 It is discussed later in this paper whether any lessons can be learnt from the medical context.

Protection under international instruments

There are a number of international instruments that might be drawn upon in order to protect both the best interests and privacy rights of children. Most notable of these is the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Article 16 specifically addresses the right to privacy:

No child shall be subject to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his or her honour and reputation.

The child has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

The principle of ‘best interests’ of the child is also ‘a universal theme of various international and domestic instruments’Footnote82 including Article 3 of the UNCRCFootnote83 and Article 24(2) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, thus influencing EU secondary law including data protection.Footnote84 The concept of best interests is further explored in the section dealing with children and medical treatment below.

The following sections go on to consider the privacy concerns of ‘Generation Tagged’ within the existing children's rights framework.

Protecting children from publicity

As a result of the children's rights jurisprudence from the last few decades, courts have begun to recognise the need to protect children who are at risk of being harmed by publicity or by having their identity revealed, although where significant interests relating to freedom of publication and open justice have been in play (such as in Re S and Re W), the courts have tended to give greater weight to such interests when balanced against the child's Article 8 rights.Footnote85 In Rocknroll v News Group Newspapers, however, a case that did not involve such heavyweight publication or open justice interests, the court stated that publication of a photograph depicting the stepfather of Kate Winslet's children half-naked would risk the children being embarrassed and might cause them harm and distress, a factor which the court said may ‘tip the balance’ in the balancing exercise between the parties respective Article 8 and Article 10 rights.Footnote86 In PJS v News Group Newspapers,Footnote87 the Supreme Court allowed the celebrity claimant's appeal against the decision of the Court of Appeal to set aside an interim injunction to restrain the Sun on Sunday from publishing an article about the claimant's extra-marital sexual activity, holding that:

There is on present evidence no public interest in any legal sense in the story, however much the respondents may hope that one may emerge on further investigation and/or in evidence at trial, and it would involve significant additional intrusion into the privacy of the appellant, his partner and their children.Footnote88

First, not only are the children’s interests likely to be affected by a breach of the privacy interests of their parents, but the children have independent privacy interests of their own. They also have a right to respect for their family life with their parents. Secondly, by section 12(4)(b), any court considering whether to grant either an interim or a permanent injunction has to have ‘particular regard’ to ‘any relevant privacy code’. It is not disputed that the IPSO Code, which came into force in January, is a relevant Code for this purpose. This, as Lord Mance has explained, provides that ‘editors must demonstrate an exceptional public interest to over-ride the normally paramount interests of children under 16′.Footnote89

In the Rhodes caseFootnote90 the Supreme Court considered whether the tort of causing intentional physical and psychological harm identified in Wilkinson v Downton Footnote91 might be extended to prevent a father publishing a book containing details expressed in vivid language about his own traumatic past life which the mother considered might cause psychological harm to their 12-year-old son. In Wilkinson it is clearly recognised that the tort has three elements: a conduct element, a mental element and a consequence element. The first and second of these were relevant in Rhodes.Footnote92 The conduct (or words) in question must be directed toward the claimant with no reasonable excuse for doing so. In this case, although there was a dedication to the claimant, together with a passage addressed to him, the book was aimed at a wider audience. In any event these factors would need to be balanced against the legitimate interest of the defendant in telling his story.Footnote93

The Supreme Court considered the mental element of the tort in some depth. The view, expressed obiter, was that there must be an intention to cause at least severe mental or emotional distress.Footnote94 Ultimately it concluded that there was no basis for supposing that the appellant had any actual intention to cause psychiatric harm or severe emotional distress to the claimant.Footnote95

In relation to our concerns regarding the privacy interests of ‘Generation Tagged’, it appears that Rhodes is of little help. Whilst there might be a conduct element here (in that parents arguably may not have acted in the best interests of their child) there is certainly no intention to cause severe mental or emotional distress on the part of anyone involved in the making of the series.

It is now accepted that children deemed ‘Gillick competent’ have the right to protection of their private lives and to decide when to tell their story. In Re Roddy (A Child) (Identification: Restrictions on Publication),Footnote96 which attracted considerable publicity, Munby J stated of the child in question:

Angela, in my judgment, is of an age, and has sufficient understanding and maturity, to decide for herself whether that which is private, personal and intimate should remain private or whether it should be shared with the whole world … The decision … is for Angela: it is not for her parents, the local authority or the court.Footnote97

Parental responsibility is defined by s 3(1) of the Children Act 1989 as including ‘all the rights, duties, powers, responsibilities and authority which by law a parent of a child has in relation to the child and his property’. Parental responsibility is normally be held by the child's parents who can provide consent on behalf of the child. It is generally expected that those with parental responsibility act in the child's best interests. However, putting this into the context we are dealing with in this paper, and specifically the ‘Secret Life’ series, it is difficult to ascertain how parents with parental responsibility, who have provided consent, have acted in the best interests of their child.

In a later section, we explore the participation of children in social or non-therapeutic medical research. Such research is generally carried out for the public benefit which could indirectly benefit the individual child. As mentioned earlier, although the makers of ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds’ highlight the scientific aspects of the programme, it is described as ‘Science Entertainment’. The responses to our freedom of information requests indicate that no data from the series had been received or used in a research context by the academic and health bodies contacted. It is therefore hard to ascertain any significant countervailing factors that would override the child's best interests. ‘Generation Tagged’ may find themselves in the position of having no reasonable expectation of privacy (or it being accorded less weight) due to the decisions of those with parental responsibility and those who are entrusted with acting in their best interests.

Competing interests

Generally where there is a clash between the interests of the child and those with parental responsibility, it will only be possible to override the decision of someone with parental responsibility if court approval is sought. For instance, the courts have had to consider whether reporting restrictions should be put in place to protect a child, even where the parent has given consent. In Re Z (A Minor) (Identity: Restrictions on Publication),Footnote100 an injunction was granted by the Court of Appeal to prevent Channel 4 from broadcasting the identity of a child with special educational needs, who was attending a specialist medical unit, despite the permission of the mother being given. Hence the courts have an important role in protecting a child who is at risk of having their privacy infringed where their parents have given consent. The need to protect children in such situations has been recognised by Loughrey, who has stated that ‘it seems wrong to hold that parental actions, which are themselves an invasion of a child’s privacy, can modify the child’s expectation of privacy and so limit the degree of protection he can expect from the law’.Footnote101 This indicates that children might be at a greater risk if their parents are consenting on their behalf and are therefore the ones who are allowing their child's privacy to be infringed.

One possibility for a ‘Gillick competent’ child, whose parents have consented to their participation in a documentary such as ‘The Secret Life’, but where the child had not consented, would be for the child to seek leave to apply for a specific issue order or a prohibited steps order, according to s 8 of the Children Act 1989, or by using the inherent jurisdiction of the court. This suggestion has been made by Gilmore and Glennon in regards to medical or psychiatric assessments.Footnote102 This process could also potentially be used by children who want to override their parent's consent if they felt their privacy was being infringed. However, this is only really accessible to the ‘Gillick competent’ child since a younger child or a child who is not Gillick-competent will be unable to initiate proceedings and are reliant on an interested third party to act on their behalf. For example, if a parent permits publicity about a child, the other parent could seek a s 8 order to prohibit the publicity.

There are clear difficulties involved in protecting the interests of children, such as those featured in ‘The Secret Life’. Such children rely generally on parents to take decisions on the basis of their best interests. However, parents may not fully appreciate the risks of taking part in such a broadcast or there may be a clash of interests between parent and child. Parents may see only the lure of celebrity and possibly money, and be blind to other possible consequences. There is undoubtedly a need for a mechanism to ensure that the best interests of the child participants are effectively protected. This is examined later in this article.

In terms of the balancing exercise between a child's Article 8 rights and a publisher's or broadcaster's Article 10 rights, it has been argued that children are considered to have ‘virtually inviolable privacy rights’Footnote103 with intrusion justified only in ‘extreme cases’.Footnote104 To outweigh a child's right to privacy, there needs to exist an ‘appreciable benefit for the child’.Footnote105 In broadcast cases, material will be almost permanently and readily available with a simple search online, together with the associated social media commentary. Even if there is public interest in the publishing of images, the media needs to ensure that ‘the dominant interest is not how many magazine copies are sold but rather the child’s best interests’.Footnote106 In the context of programmes such as ‘The Secret Life’, absent payment, it is difficult to establish any direct benefit to the child. Unlike adults, children are very unlikely to derive any benefit from publication of information or broadcasts about themselves.

Smartt has argued that concerns about privacy do ‘not mean that children should never be photographed in public, as long as it is not detrimental to the child at the time of publication or in the future’.Footnote107 We consider that this statement represents too simplistic a view when put in the context of programmes such as ‘The Secret Life’, their associated social media activity and the longevity of material available on the Internet. The best interests of a child requires something more positive to the child to be weighed in the balance, rather than merely being non-detrimental which is neutral at most. We explore ‘best interests’ further in the next section.

The Ofcom Broadcasting Code mentioned above requires broadcasters to take ‘due care’ with the welfare of the child, irrespective of parental consent, and emphasises that privacy intrusion must be ‘warranted’. From the responses to the freedom of information requests received, it is difficult to determine how much weight was given to the privacy interests, both current and future, of the children involved. We would argue in addition that the Code itself does not reflect the considerable weight that should be given to the children's best interests, and the need for a strong and clear public interest to justify intrusion into a young child's privacy.

Again, we are left without a resolution here. There is a clearly stated intention that a child’s welfare and privacy should normally be regarded as the primary consideration. What is lacking is any way of ensuring that this happens in the face of parental consent.

Medical consent and ethical considerations

Welfare checklist approach

Within the meaning of the Children Act 1989Footnote108 anyone with parental responsibility can give valid consent to medical treatment on behalf of a child. Generally, where both parents hold parental responsibility the consent of one parent is enough. The underpinning principle of the Act is that the child’s welfare is the paramount consideration in any decision relating to her upbringing.Footnote109 A ‘welfare checklist’ provides a list of factors that might be considered in determining any question regarding the child's upbringing.Footnote110 This checklist includes the need to take into account, inter alia, the ascertainable wishes and feelings of the child (in light of his age and understanding);Footnote111 the physical, emotional and educational needs of the child;Footnote112 any harm which he has suffered or is at risk of suffering.Footnote113 Thus, any decision taken by parents regarding the medical treatment of their child must be taken with the child's welfare as the paramount consideration. This will extend not only to consent to medical treatment but to refusal of treatment where that refusal is in the child's best interests.Footnote114

It is useful to consider here some of the most difficult circumstances that might be faced by those making medical decisions of behalf of children who lack capacity. Those responsible for the care and treatment of a child in such circumstances have a duty to take decisions based on the best interests of that child. In most situations there is a presumption that preservation of life will be in the best interests of the patient. However, there exists a category of children and young people with life-limiting illness for whom this will not be the case. In such circumstances case law confirms that the ‘welfare principle’ is operative and the best interests of the child must be the paramount consideration, regardless of parental wishes, or indeed of those treating the child.Footnote115 This might well mean that withholding or withdrawing life sustaining treatment is determined as being in the best interests of the child.

In A NHS Trust v B,Footnote116 Holman J, utilised a ‘balance sheet’ to weigh the benefits and burdens of continuing with or withdrawing life sustaining treatment of MB, the young child concerned in the case. In this instance it was determined that the benefits of continued treatment and the quality of life that would be afforded to MB as a result outweighed the burdens of distress, discomfort and pain that accompanied that treatment. A similar approach was taken in Re K Footnote117 where the reverse was found and withdrawal of treatment determined to be in her best interests.

In relation to the topic in hand, this ‘balance sheet’ approach is worthy of consideration. If the existing duty of the parents of the children involved in this series is to act in the best interests of their child, in accordance with the ‘welfare principle’ then it would seem on the face of it that the risks of permitting participation far outweigh the benefits. Channel 4 claim in its direct response quoted above that the experience for the children has been ‘enormously enriching’, although the evidence for this is difficult to discern. It is possible that harm might be caused, perhaps of a significant and long-lasting nature. It is hard to justify running this risk under the criteria of the ‘welfare checklist’ and this difficulty casts doubt upon whether the best interests of the child are served.

Confidentiality

When dealing with children, the medical profession has a duty to respect confidentiality in the same way as it does for adults. In the case of very young children, as we have seen, parents have a duty to take decisions in the best interests of their child. In these cases the doctor owes a duty of confidentiality to the child and her parents as a family unit. However, we need to consider the position of the parents. Do they owe a duty of confidentiality to their child? Might they in extreme circumstances be able to, for instance, talk to the press about the treatment of their child? This was the issue for the court in Re C (A Minor) (Wardship: Medical Treatment) where it was made clear that any discussion of C's case by her parents or carers would constitute a breach of confidence. In granting an injunction to prevent such a breach the court said:

the court is entitled and bound in appropriate cases to make decisions in the interests of the child which override the rights of its parents.Footnote118

C’s interest in protecting the confidentiality of personal information about himself must not be underestimated. It is all too easy for professionals and parents to regard children and incapacitated adults as having no independent interests of their own: as objects rather than subjects.Footnote119

Non-therapeutic medical research

Non-therapeutic research is defined in a medical context as research where the aim is to benefit future patients, not the person participating in the research.Footnote120 It might be possible to view ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds’, with its semi-scientific aspects, as a form of non-therapeutic research (although it is difficult to see at this stage how the research would have been justified if carried out in a traditional medical context bearing in mind that our freedom of information requests revealed that no research data have been received by the higher education and health bodies). It is beyond the scope of this article to conduct a complete review of the legal and ethical considerations relating to this type of research. It is however worth highlighting that, even within a traditional medical research context, the relevant standards and procedures continue to be challenged and debated. Bell argues that although the court has been prepared to widen the definition of best interests of the child beyond medical treatment to social and psychological factors,Footnote121 ‘caution should be exercised when taking principles from [such] cases and trying to make them fit a research situation’.Footnote122 She argues that, although in S vS,Footnote123 the House of Lords was prepared to allow a five-year-old child to undertake a paternity test provided the test was not ‘against the interests’ of the child, this case ‘goes against the grain’ of most other judgments.Footnote124

In relation to non-therapeutic research involving children, Driscoll is concerned about the tendency of frameworks to be ‘adult-centric’.Footnote125 Further, Lambert and Glacken conclude that

how children’s competence is assessed is less well articulated with literature illuminating its complexity by highlighting a number of influential variables. Ultimately, it often becomes the sole responsibility of each individual researcher to make this assessment.Footnote126

In contrast with the position of children, research involving mentally incapacitated adults is covered by statute.Footnote127 If the research is non-therapeutic, then it cannot be approved unless:

the research is intended to provide knowledge of the causes or treatment of, or of the care of persons affected by, the same or a similar condition;Footnote128the risk to the participant is likely to be negligible;the research will not interfere with the participant’s freedom of action or privacy in a significant way or be unduly invasive or restrictive.Footnote129

A number of elements from the above approaches to non-therapeutic research could well serve to improve the assent and oversight processes relating to the rights of children involved in fly-on-the-wall documentaries. We explore these in our concluding section.

General ethical considerations

In healthcare decision-making in relation to children, a duty of care is owed to the child by both medical practitioners and the child's parents. In the main, where the child lacks capacity, as the young children in this series do, decisions are taken in partnership and must be in the best interests of the child. In ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds’ there are a number of parties involved: the parents, the production company (RDF Television), Channel 4, University of Bristol, the MCR Cognition and Brain Unit at the University of Cambridge, Oxlease NHS Trust and the Wellcome Trust. Arguably all owed a duty of care to the child participants. Given the response to the freedom of information requests regarding ethics approval processes, it is difficult to say whether this ethical duty was considered and if so to comment on the extent of that consideration.

Further, there is the ethical underpinning of respect for the internationally agreed rights of the children involved which are both positive and negative in nature, in this particular context that prescribed under Article 3 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child which requires:

In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions … the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.

Finally, we return to compliance with legal frameworks. This has already been considered in some detail and the level of compliance must be questioned. It seems that there is much that those involved in the making of this series could learn from the ethical and legal frameworks that underpin medical decision-making. There are clear welfare analogies that emerge. Particularly interesting is the issue of the best interests of the child and long term harm. The four, five and six-year-olds involved may have suffered no immediate or obvious effects. The long view may well be different.

The governance and ethics process that underpin the broadcast of this series appear to contrast with the rigour of UK Health Research Authority requirements.Footnote132 The potential harms that flow from the involvement of these children in these programmes are considerable. This is heightened in light of the unstoppable nature of the dissemination of social media. Many of these children will be exercising their ‘right to be forgotten’ long into the future.

Conclusions and recommendations

As a result of our research into Generation Tagged, we have concluded that there appear to be significant issues with both the relevant law and oversight processes relating to images of and information about young children on broadcast and social media. Neither data protection law nor the tort of misuse of private information seem to deal with the fundamental question of whether the children should have been so exposed, instead relying to a large extent on the consent of parents. Although the broadcast code requires care to be taken over the physical and emotional welfare and the dignity of children irrespective of parental consent, this has not prevented sensitive aspects of a child’s life being exposed in the interests of ‘Science Entertainment’ . There is clearly some public interest in such programming. How would this public interest be judged however against the considerable weight that should be given to a child's best interests as confirmed recently in PJS?Footnote133 In addition, little consideration appears to have been given to the potential impact of the associated social media commentary, which in some circumstances may cause harm only in the future when the child becomes more aware.

The legal and ethical framework has failed to keep track with the changing nature of broadcast programming; it is now less ephemeral, often available for long after original broadcast on the Internet via on-demand services or repeated on various spin-off channels, with social media interaction making that broadcast part of the online record, and digital technologies and search tools giving access to information that an individual might have assumed was out of reach or hard to find. Broadcast media must now be regarded as part of the online record and regulated accordingly. Miller has said that:

the near free-for-all information collection and plundering of the dematerialised virtual or digital body stands in stark contrast to the ethical and legal weight placed on the material aspects of selves … the networked aspects of selves are increasingly open to collection, scrutiny and analysis, especially for commercial gain.Footnote134

We would argue that steps need to be taken to recognise this risk as regards the virtual exposure of young children on broadcast and social media, and lessons learnt from the way that the family and medical contexts deal with exposure of the ‘material body’.

There seems to be a lack of joined up thinking around the ‘welfare principle’. It is compartmentalised. In family matters there is a requirement that decisions taken make the welfare of the child paramount. This undoubtedly confers a duty to act in her best interests. The same is true in medical decision-making on behalf of children and others who lack capacity. This should be the case in relation to all decisions that have the potential to exploit and harm the vulnerable.

Proposals for reform

There needs to be additional governance and oversight of the broadcast and related online media industry. Our suggestions for this are set out below:

The appointment of a ‘Children’s Commissioner for Media, Broadcast and the Internet’ to ensure that the interests of children who lack the capacity to consent to participation are independently and impartially represented and protected;

Consideration to be given to the creation of an ‘amicus brief’ for young children in the position of those in ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds’. This independent expert would be required to consent to the involvement of the child in the series (in addition to the consent of the parents being obtained) and tasked with considering not only the immediate risks but those that could arise in the future, for instance on social media. In the event of a disagreement between the expert and the parent, the expert would have the right to bring an application to court on behalf of the child;

The Ofcom Broadcasting Code to be amended to reflect the ‘welfare principle’ as mentioned above. In a similar way to non-therapeutic medical research, the Code needs to go much further in order to respect the child as informed decision-maker irrespective of parental permission, detect subtle signs of refusal and specify strategies to ensure that children can withdraw, stop or change their mind about participation;

The ethical review process within academic and medical bodies to be strengthened to ensure that no research-related activity of staff, particularly when involving children, falls outside the process;

Parents of young children and the ‘amicus brief’ to have a right to veto the broadcast of elements of a programme that could damage the privacy or dignity of the child now or in the future. Currently, parental consent appears to be somewhat of a fallacy as it is given before filming commences and parents are specifically unable to veto the final broadcast that depicts their children. In the event of a disagreement between the expert and the parent, the expert again should have the right to bring an application to court on behalf of the child. This process mirrors Townend's call for a highly developed consent process, going beyond the minimum legal requirements and which pays attention to the emotional impact of participation and requires both permission to film and secondary permission to use the material;Footnote135

Consideration to be given to amending the journalistic exemption in the Freedom of Information Act to require public-service broadcasters to provide information about their compliance with broadcasting codes and other legal requirements in relation to child welfare.

This article ends with a final challenge for society. As we are beginning to understand the long-term implications of Internet publication, now is the time for us all to step back to consider whether we want private childhood moments to become eternal public entertainment and the subject of social media public comment. Further research into the implications of the availability for a number of years of this type of information, taking into account the inevitable changes to social media and to identify any effects in the longer term on the children involved, would be of vital assistance in this regard.

Notes

1 Courtney Shea, ‘The rewards and risks of giving babies social media accounts' thestar.com(28 January 2016) www.thestar.com/life/parent/2016/01/28/the-rewards-and-risks-of-giving-babies-social-media-accounts.html

2 Michael Schneider, ‘New to Your TV Screen: Twitter Hashtags' 21 April 2011, www.tvguide.com/news/new-tv-screen-1032111/

3 Oxford English Dictionary: ‘(on social media web sites and applications) a word or phrase preceded by a hash and used to identify messages relating to a specific topic; (also) the hash symbol itself, when used in this way.’

4 Moira Petty, ‘Violence, bullying and tears: How on earth could “respectable” parents let their children enter Channel 4's 'cruel' experiment?' Mail Online (4 February 2009) www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-1135379/How-earth-respectable-parents-let-children-enter-Channel-4s-cruel-experiment.html

5 Channel 4, ‘The Three Day Nanny' television series, first broadcast July 2015, www.channel4.com/programmes/the-three-day-nanny

6 Channel 5, ‘My Violent Child’ television series, first broadcast February 2015, www.channel5.com/shows/my-violent-child

7 Channel 4, ‘Born Naughty' television series, first broadcast May 2015, www.channel4.com/programmes/born-naughty

8 Rebecca Hardy, ‘Car crash television at its worst: How star of Channel 4's Child Genius was reduced to tears in front of millions – while his parents are critical of its makers' Mail Online (16 August 2014) www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2726418/A-child-genius-left-sobbing-millions-parents-betrayed-Channel-4.html

9 Judith Townend, ‘Layers of Consent’ (2014) 11(3) Ethical Space: The International Journal of Communications Ethics 25, 27.

10 Eric Barendt, Anonymous Speech (Hart Publishing, 2016) 92.

11 ‘Programme Information: The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds' Channel4.com (22 October 2015) www.channel4.com/info/press/programme-information/the-secret-life-of-4-5-and-6-year-olds

12 Professor Paul Howard-Jones (Educational Neuroscientist, Bristol University); Dr Sam Wass (Developmental Psychologist, MCR Cognition & Brain Unit, Cambridge); Dr Elizabeth Kilbey (Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Oxleas NHS Trust).

13 ‘Teresa Watkins interview [Executive Producer, RDF television]’ Channel4.com, Press, News & Video (22 October 2015) www.channel4.com/info/press/news/teresa-watkins-interview

14 ‘Five-year-olds Emily and Alfie rekindle their fond friendship, and are both due to play sheep. When Emily has serious stage fright, Alfie offers to wipe her tears away and reminds her he’ll be by her side. Elvin lands the important role of narrator, but the responsibility soon begins to weigh heavily on his shoulders. As performance day arrives, the week's ups and downs must be put to one side as the children take to the stage in front of family and friends, with just one chance to get it right’: Programme Information (n 11).

15 Programme Information (n 11).

16 Wellcome Trust Press Release, ‘Exploring “The Secret Life of Four Year Olds”’ (6 February 2015) www.wellcome.ac.uk/News/Media-office/Press-releases/2015/WTP058612.htm

17 Programme Information (n 11).

18 Teresa Watkins interview (n 13).

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 ‘The Secret Life of 5 Year Olds – Biogs', Channel4.com (3 November 2015) www.channel4.com/info/press/news/the-secret-life-of-5-year-olds-biogs

24 Stanford University, Bing Nursery School home page https://bingschool.stanford.edu/

25 Jenny Johnston, ‘What children REALLY do when parents aren’t around: Eye-opening show reveals hilarious (and tear-jerking) behaviour of four-year-olds filmed by hidden cameras', Mail Online (31 October 2015) www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-3295342/What-children-REALLY-parents-aren-t-revealed-eye-opening-documentary.html

26 The Ofcom Broadcasting Code, Section One; Protecting the Under-Eighteens, Rules 1.28 (due care for physical and emotional welfare and dignity of children irrespective of parental consent) and 1.29 (children must not be caused unnecessary anxiety or distress) http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/broadcasting/broadcast-codes/broadcast-code/protecting-under-eighteens/; Ofcom Guidance on Rules 1.28 and 1.29, http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/broadcast/guidance/831193/updated-code-guidance.pdf

27 Ofcom Guidance on Rules 1.28 and 1.29, http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/broadcast/guidance/831193/updated-code-guidance.pdf

28 Ibid, 7.

29 Ibid, 6.

30 Ibid, 5.

31 Ibid, 8.

32 Ofcom Broadcasting Code, 1 July 2015, Section Eight: Privacy, rule 8.1 http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/broadcasting/broadcast-codes/broadcast-code/privacy/

33 British Broadcasting Corporation v Sugar and another (No 2) [2012] 2 All ER 509.

34 Channel 4 Producers Handbook, Working & Filming with Under 18's Guidelines www.channel4.com/producers-handbook/c4-guidelines/working-and-filming-with-under-18s-guidelines

35 Ibid.

36 RDF Television, ‘The Secret Life of 4, 5 and 6 Year Olds' Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/thenurseryC4/

37 Statement by Channel 4 (personal email correspondence 5 August 2016).

38 Ibid.

39 Data Protection Act 1998 c 29.

40 95/46/EC.

41 Regulation (EU) 2016/679.

42 Ibid, Recital (38).

43 Paul Bernal, Internet Privacy Rights (Cambridge University Press, 2014) 223.

44 Regulation (n 41) article 17 ‘Right to erasure (“right to be forgotten”)’ which gives individuals a right to require data controllers to erase their personal data in certain circumstances, such as where they withdraw consent and no other legal ground for processing applies, together with an obligation on the controller to inform third parties that the data subject has requested erasure of links to, or copies of, the data (a broader right than that created by the CJEU in C-131/12 Google Spain; Mario Costeja Gonzalez [2014] EMLR 27).

45 Regulation (n 41) Recital (65).

46 Rynes v Urad pro ochranu osobnich udaju [2014] All ER (D) 174 (Dec); Criminal proceedings against Lindqvist (Case C-101/01) [2003] All ER (D) 77 (Nov).

47 95/46/EC (n 40).

48 WP 163, 0189/09/EN, Opinion 5/2009 on online social networking, 6.

49 Regulation (n 41) Recital (18).

50 Ibid: the Regulation applies to controllers or processors which provide ‘the means' for processing personal data for household or personal activities.

51 See Daniel J Solove, ‘A Taxonomy of Privacy’ (2006) 154(3) University of Pennsylvania Law Review 477.

52 Jacqueline Lipton, Rethinking Cyberlaw (Edward Elgar, 2015) 141.

53 Julia Llewellyn Smith, ‘I think Mummy could push me harder’ The Daily Telegraph (London, 6 August 2016).

54 Kathryn Knight, ‘What your little sweethearts really think of each other!’ Daily Mail (London, 11 July 2016) www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3683600/What-little-sweethearts-REALLY-think-s-parent-love-know-children-not-truly-enchanting-new-TV-reveals-heart-warming-hilarious-answers.html (accessed 7 September 2016).

55 Vidal-Hall and others v Google Inc [2014] 1 WLR 4155, [70].

56 Campbell v MGN Ltd [2004] 2 AC 457, 51.

57 Weller v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2014] EWHC 1163 (QB).

58 Murray v Express Newspapers plc [2009] Ch 481.

59 Weller (n 57) 170–71.

60 Weller and Ors v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2016] 3 All ER 357.

61 Ibid, [29].

62 Ibid, [29].

63 Ibid, [20].

64 Ibid, [35].

65 Ibid, [36].

66 Ibid, [38].

67 Ibid, [40].

68 Ibid, [41].

69 AAA v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2012] EWHC 2103 (QB) [119].

70 Murray (n 58) [57].

71 Holly Hancock, ‘Weller & Ors v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2015] EWCA Civ 1176: Weller Case Highlights Need for Guidance on Photography, Privacy and the Press' (2016) 8(1) Journal of Media Law 17, 29.

72 Jacqueline Lipton ‘We the Paparazzi: Developing a Privacy Paradigm for Digital Video’ (2010) 95 Iowa Law Review 919.

73 Paul Wragg ‘Protecting Private Information of Public Interest: Campbell's Great Promise, Unfulfilled’ (2015) 7(2) Journal of Media Law 225, 249.

74 Eric Descheemaeker, ‘The Harms of Privacy’ (2015) 7(2) Journal of Media Law 278, 300.

75 Eric Barendt, ‘Problems with the “Reasonable Expectation of Privacy” Test’ (2016) Journal of Media Law 9 doi: 10.1080/17577632.2016.1209326

76 Emma Cave, ‘Adolescent Consent and Confidentiality in the UK’ (2009) 16 European Journal of Health Law 309, 310.

77 [1986] AC 112.

78 Ibid, 186.

79 [2006] 88 BMLR 96.

80 Cave (n 76) 321.

81 Joan Loughrey, ‘Can You Keep a Secret? Children, Human Rights, and the Law of Medical Confidentiality’ (2008) 20(3) Child and Family Law Quarterly 312.

82 Lord Kerr in ZH (Tanzania) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2011] 2 All ER 783, [46].

83 Article 3(1): In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.

84 2000/C 364/01. Article 24(2): In all actions relating to children, whether taken by public authorities or private institutions, the child's best interests must be a primary consideration.

85 For example see In Re S (a child) (Identification: Restrictions on Publication) [2004] 1 AC 593; In Re W (Identification: Restrictions on Publication) [2006] EWHC 2733 (Fam); In Re M and N (Minors) (Wardship: Publication of Information) [1990] Fam 211; Re Steadman [2009] EWHC 935 (Fam).

86 [2013] EWHC 24 (Ch) [39]. [2013] EWHC 24, [36]–[37], [39]

87 PJS v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2016] 2 WLR 1253.

88 Ibid, [44] (Lord Mance).

89 Ibid, [72].

90 OPO and another v Rhodes [2015] 4 All ER 1.

91 [1895–99] All ER Rep 267.

92 OPO (n 90), [73].

93 Ibid, [75].

94 Ibid, [88].

95 Ibid, [89].

96 [2003] EWHC 2927.

97 Ibid, [56], [59].

98 Cave (n 76) 323.

99 Ibid.

100 [1996] 1 FLR 191.

101 Loughrey (n 81) 322.

102 Stephen Gilmore and Lisa Glennon, Hayes and Williams' Family Law (Oxford University Press, 2012) 445.

103 Professor David E Morrison and Michael Svennevig, The Public Interest, the Media and Privacy (A report for the British Broadcasting Corporation, March 2002) http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/guidelines/editorialguidelines/research/privacy.pdf

104 Ibid.

105 Alexander Carter-Silk and Claire Cartwright-Hignett, ‘A Child's Right To Privacy: “Out of a Parent's Hand”’ (2009) 20(6) Entertainment Law Review 212.

106 Ibid.

107 Ursula Smartt, Media and Entertainment Law (Routledge, 2011) 68.

108 Children Act 1989 s 2.

109 Ibid.

110 Ibid, s 1(3).

111 Ibid, s 1(3)(a).

112 Ibid, s 1(3)(b).

113 Ibid, s 1(3)(e).

114 Re T (A Minor) (Wardship: Medical Treatment) [1997] 1 WLR 242.

115 Re C (A Minor) (Medical Treatment) [1998] Lloyd's Rep Med 1 (Fam Div); Portsmouth Hospital NHS Trust ex p Glass [1999] FCR 363.

116 A NHS Trust v B [2006] EWHC 507 (Fam).

117 Re K (A Minor) [2006] 99 BMLR 98.

118 Re C (A Minor) (Wardship: Medical Treatment) [1990] Fam 39.

119 R (S) v Plymouth City Council [2002] 1 WLR 2583 [47].

120 Leanne Bell, Medical Law and Ethics (Pearson, 2013) 239.

121 Re Y [1997] Fam 110; Simms v Simms [2003] 1 All ER 669.

122 Bell (n 120) 247.

123 [1972] AC 24.

124 Bell (n 120) 246.

125 Jenny Driscoll, ‘Children's Rights and Participation in Social Research: Balancing Young People's Autonomy Rights and Their Protection’ (2012) 24(4) Child and Family Law Quarterly 452, 454.

126 Veronica Lambert and Michele Glacken, ‘Engaging with Children in Research: Theoretical and Practical Implications of Negotiating Informed Consent/Assent’ (2011) 18(6) Nursing Ethics 781, 798.

127 The Mental Capacity Act 2005.

128 Ibid, s 31(5)(b).

129 Ibid, s 31(6).

130 Ibid, ss 32(2)(3)(4).

131 Ibid, s 32(5).

132 The National Research Ethics Service governs local research ethics committees; regulations require both clinical and non-clinical research to come before a committee: NHS Health Research Authority Homepage www.hra.nhs.uk/news/dictionary/nres/

133 PJS (n 87).

134 Vincent Miller, The Crisis of Presence in Contemporary Culture: Ethics, Privacy and Speech in Mediated Social Life (Sage, 2015).

135 Townend (n 9) 28.