?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Using sample firms from eight energy-intensive industries included in the State Council of China’s Notice on the Pilot Work of Carbon Emission Trading from 2015 to 2019, this study examines the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure, and explores the moderating effect of political connection on this relationship. The baseline results show that environmental legitimacy pressure is positively associated with impression management of carbon information disclosure, and political connection moderates this relationship, that is, the positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure in politically-connected firms is stronger than that in non-politically-connected firms. The results are robust to various sensitivity tests. Further analyses show that (i) the positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure in non-state owned enterprises (non-SOEs) is stronger than that in SOEs, (ii) firms facing higher negative environmental legitimacy pressure have stronger motivation to conduct impression management of carbon information disclosure, (iii) firms facing environmental legitimacy pressure conduct both selective disclosure and expressive manipulation but they have stronger motivation to conduct expressive manipulation. This study extends the literature on impression management of carbon information disclosure. The findings in this study provide policy implications not only for China but also for countries with large carbon emission.

Introduction

On the one hand, legitimacy theory is widely employed to explain the motivation for firms’ carbon information disclosure. Environmental legitimacy pressure, as a key aspect of organizational legitimacy, is the primary factor to motivate firms to disclose carbon information. On the other hand, insiders have motivation to relieve firms’ legitimacy pressure by improving firms’ image of carbon management (i.e. impression management of carbon information disclosure). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies exploring the impact of environmental legitimacy pressure on firms’ impression management of carbon information disclosure. To fill this gap, we examine the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and firms’ impression management of carbon information disclosure using China’s eight energy-intensive industries as research samples.

China, as the largest emerging economy, offers us an interesting setting to explore the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure. First, the State Council issued The Thirteenth Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of China (henceforth, The Thirteenth Five-Year Plan) on October 27, 2016. The Thirteenth Five-Year Plan urges the government to establish an information disclosure system for greenhouse gas emission and to encourage firms to voluntarily disclose information on carbon emission. Since then, firms have been gradually increasing their awareness of climate change risks and improving the level of carbon information disclosure. However, due to the lack of a unified disclosure standard for carbon information, the quality of firms’ carbon information disclosure is still poor.

Second, China is formulating detailed and practical measures to reduce carbon emission, and has established the largest carbon trading market worldwide on December 19, 2017, which was only open to power generation sector during the early stage. The carbon dioxide emission in power generation sector was expected to reach 3.3 billion metric tons in 2020, accounting for approximately 30% of China’s carbon dioxide emission, and to exceed that in European Union’s market [Citation1]. In September 2020, China announced that it will peak carbon dioxide emission prior 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality prior 2060. Subsequently, the State Council issued The Guideline on Accelerating the Establishment of a Green, Low-carbon and Circulatory Economic System (henceforth, The Guideline) on February 22, 2021. The Guideline calls for an effort to improve resource-using efficiency, ensure the coordination between economic development and environmental protection, and control greenhouse gas emission effectively. Against such background, China Carbon Emission Trade Exchange was set up on July 16, 2021, which aims at peaking carbon dioxide emission and achieving carbon neutrality. Meanwhile, China plans to gradually expand the market to cover more energy-intensive industries and enrich the varieties and methods of carbon emission trading. As the government puts emphasis on the reduction of carbon dioxide emission, carbon information disclosure attracts attention in the academic community.

Third, due to the lack of appropriate regulation on carbon information disclosure in China, the level of Chinese firms’ carbon disclosure is still relatively low. As a form of non-financial information disclosure, carbon information disclosure is not required to be audited by an independent third-party, which provides an opportunity for firms to conduct impression management on carbon information disclosure. Firms might be subject to organizational legitimacy in their operation and, thus, might have incentives to conduct impression management on carbon information disclosure.

Our motivation for linking environmental legitimacy pressure to firms’ impression management of carbon information disclosure stems from the following considerations. First, information disclosure is not only a primary means for stakeholders to acquire information on corporate operation but also an indispensable means for insiders to influence stakeholders’ impression toward them [Citation2]. As a significant part of information disclosure, carbon information disclosure plays a similar role with financial information disclosure and is widely concerned by the market [Citation3,Citation4]. However, whether disclosing carbon information or not is a voluntary and strategic decision for firms [Citation5]. Investors have few channels to monitor firms’ carbon information disclosure behavior, which provides insiders with opportunities to manipulate carbon information disclosure [Citation6]. Thus, to best serve their own interests, insiders have motivation to disclose carbon information with impression management.

Second, impression management of information disclosure refers to the practices that insiders consciously try to change the impression of primary audience, such as shareholders, creditors, the government, suppliers, customers and other stakeholders, by strategically disclosing information [Citation7]. There are two commonly used impression management strategies for insiders. One is to express positive information clearly and the other is to express negative information ambiguously [Citation8]. Prior studies mainly focus on impression management of corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports. One stream of studies investigates its determinants, such as corporate governance [Citation9], directors’ gender [Citation10] and stakeholders’ perceptions [Citation11]. Another stream of studies examines its economic consequences, such as firm performance [Citation2] and the cost of equity capital [Citation12]. However, only a limited number of studies pay attention to impression management of carbon information disclosure. For example, Talbot and Boiral [Citation13] put forward the concept of impression management of carbon information disclosure and point out that impression management affects the quality of carbon information disclosure. They also illustrate the impression management strategies in carbon information disclosure by taking 21 energy firms as examples [Citation14]. Luo et al. [Citation15] document a positive association between external financing demands and the impression management of carbon information disclosure.

Third, organizational legitimacy is an important determinant for firms’ behavior of carbon information disclosure [Citation16]. Environmental legitimacy pressure, as a key aspect of organizational legitimacy, is expected to drive the behavior of firms’ carbon information disclosure [Citation17]. Thus, we expect that insiders have motivation to relieve firms’ environmental legitimacy pressure by improving firms’ carbon management image.

To examine the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure, we use China’s eight energy-intensive industries as research samples, and create an indicator variable and a continuous variable to measure environmental legitimacy pressure from 2015 to 2019. Following Luo et al. [Citation15], we construct an index to measure the impression management of carbon information disclosure. The baseline results show a positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure, suggesting that firms with higher environmental legitimacy pressure conduct more impression management on carbon information disclosure. Next, we explore the moderating effect of political connection on the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure as prior studies find that political connection significantly affects firms’ carbon information disclosure [Citation18,Citation19]. Following extant studies, we create an indicator variable and a continuous variable to measure political connection. The results show that the positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure in politically-connected firms is stronger than that in non-politically-connected firms, suggesting that political connection moderates the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure.

Moreover, giving that state ownership is an influential factor for cooperate decisions in China, we divide the full sample into two sub-samples: state-owned enterprises (SOEs) vs. non-SOEs. The results show that the positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure in non-SOEs is stronger than that in SOEs. To further test the divergent effect of different types of environmental legitimacy pressure on impression management of carbon information disclosure, we divide environmental legitimacy pressure into positive, neutral and negative pressure ones. The results show that, when being subject to higher negative environmental legitimacy pressure, firms have stronger motivation to conduct impression management on carbon information disclosure. Finally, we examine the divergent effect of environmental legitimacy pressure on different impression management strategies of carbon information disclosure. We divide impression management strategies of carbon information disclosure into selective disclosure and expressive manipulation. The results show that firms facing environmental legitimacy pressure conduct both selective disclosure and expressive manipulation but they have stronger motivation to conduct expressive manipulation.

Our study makes three contributions to the literature. First, our study extends the literature on carbon information disclosure. Existing literature mainly focuses on the determinants of carbon information disclosure, and overlooks the impression management of carbon information disclosure. Our analyses fill this gap in the literature by exploring the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure.

Second, our study provides a deeper insight into the determinants of impression management of carbon information disclosure. Most of prior literature on insiders’ opportunistic behavior focuses on earnings management and impression management of financial information disclosure, and few pays attention to the manipulation of non-financial information disclosure, especially carbon information disclosure. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure and, thus, contributes to the literature on the determinants of impression management in non-financial reporting from the perspective of external legitimacy pressure.

Third, our study divides the impression management strategies of carbon information disclosure into selective disclosure and expressive manipulation, and demonstrates that firms have motivation to adopt different impression management strategies under different environmental legitimacy pressure. Thus, our study provides a framework for future studies to explore the impression management strategies of carbon information disclosure.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature and develops research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the sample, data, variable measurements and model constructions. Section 4 presents the empirical results. Section 5 concludes the paper.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure

Legitimacy theory is widely used by researchers to interpret firms’ information disclosure motivation [Citation20]. Organizational legitimacy is defined as the perception of the public that the actions of an organization are desirable, proper, or appropriate according to the generally accepted social norms and values [Citation21]. If there are actual or potential divergences between firm behavior and the generally accepted social norms and values, organizational legitimacy will be challenged, which subsequently results in organizational legitimacy pressure [Citation22]. Environmental legitimacy pressure is one of the primary components of organizational legitimacy pressure, it determines whether firms materially improve the quality of carbon footprint-related disclosure or strategically disclose carbon information [Citation17]. Accordingly, the existing studies have explored the relationship between organizational legitimacy pressure and carbon/environmental information disclosure. For example, He et al. [Citation23] argue that firms maintain organizational legitimacy via voluntary information disclosure, and find that the greater a firm’s external pressure is, the higher the level of a firm’s carbon information disclosure will be. Lewis et al. [Citation24] argue that CEO characteristics explain why firms facing similar institutional pressure adopt different environmental strategies, and find that, relative to firms led by lawyers, firms led by newly appointed CEOs and CEOs with MBA degrees are more likely to respond to the Carbon Disclosure Project. Li et al. [Citation16] demonstrate that environmental legitimacy significantly and negatively affects the likelihood of firms’ carbon disclosure.

The main purposes of firms’ carbon information disclosure include forming consensus on environmental protection among key stakeholders [Citation25], influencing public opinion [Citation26], acquiring environmental legitimacy [Citation27] and improving corporate reputation [Citation28]. If the negative news about CSR, such as water pollution and greenhouse gas emission, is widely reported by the media, firms will encounter environmental legitimacy pressure [Citation29]. In order to improve firms’ carbon management image and, thus, relieve firms’ environmental legitimacy pressure, insiders have motivation to conduct impression management on carbon information disclosure through selective disclosure or expressive manipulation [Citation30].

According to agency theory, given the information asymmetry and inconsistent interests between insiders and outsiders, the agency conflict between insiders and outsiders arises [Citation31]. The agency conflict affects insiders’ and outsiders’ behavior, especially when firms suffer from environmental legitimacy pressure [Citation32]. Firms with high media attention to environmental performance are usually subject to great environmental legitimacy pressure, which will increase the environmental legitimacy risks. Carbon information disclosure is instrumental in reducing the information asymmetry between insiders and outsiders, which in turn decreases agency conflicts and environmental legitimacy risks [Citation33]. As a result, insiders will conduct impression management on environmental information disclosure to ensure firms’ legitimacy [Citation34]. Based on their own interests, insiders have motivation to disclose large amounts of carbon information for the following reasons. First, carbon information disclosure ensures firms’ environmental legitimacy by meeting stakeholders’ requirements. Second, carbon information disclosure defends firms’ poor financial performance, which in turn relieves insiders’ operational responsibility. Third, while firms conduct green investment and management, insiders tend to disclose carbon information selectively in order to reduce the high cost of information disclosure and to deliver “low-carbon” signals to stakeholders [Citation35]. Besides, industry attribute is an important indicator of public visibility, and thus firms with serious pollution tend to attract more media attention and to suffer from tremendous environmental legitimacy pressure. As environmentally sensitive industries, the eight energy-intensive industries are subject to stricter requirements from environmental stakeholders. Therefore, in order to avoid antipathy of the public and to ensure firms’ environmental legitimacy, insiders have motivation to conduct impression management on carbon information disclosure. We, thus, propose our first hypothesis as follows:

H1. Environmental legitimacy pressure is positively associated with impression management of carbon information disclosure, that is, firms facing higher environmental legitimacy pressure conduct more impression management on carbon information disclosure.

Moderating role of political connection

Political connection refers to the relations between firm’s executives/directors and government officials [Citation36]. Prior studies suggest that political connection can not only substitute for weak investor protection and unstable political situation [Citation37] but also can help firms obtain government resources [Citation38]. According to rent-seeking theory, the purpose of rent-seeking activities is to obtain rents, and political connection is an essential political resource for firms, which leads them to shirking environmental responsibility and, thus, worsens corporate environmental performance [Citation39]. Managers often spend a large amount of cost on rent-seeking activities to acquire a monopoly in the availability to some important resources or to conclude an implicit contract with the government [Citation40]. In China, corporate operation and development are constrained by an imperfect institutional environment and, thus, firms tend to seek rent from the government by building political connection. Although the goal of environmental legislation is to promote the coordination between economic development and environmental protection, local governments often relax environmental regulation to guarantee a seemingly sound economic performance; thus, the cost of firms’ environmental pollution and violation on environmental laws is relatively low [Citation41]. Moreover, regarding environmental issues, local governments impose soft constraints on politically-connected firms, which ultimately leads to a weak law enforcement and, hence, increases firms’ tendency to violate environmental laws [Citation41]. For example, Lei et al. [Citation42] point out that local governments mitigate the punishment of environmental violation for politically-connected firms and, consequently, firms’ environmental pollution is not effectively restrained.

However, according to legitimacy theory, the response of an organization to environmental legitimacy pressure depends on the level of environmental legitimacy pressure [Citation34]. There is a significant difference in the level of environmental legitimacy pressure between politically-connected and non-politically-connected firms. Media attention plays a vital role in guiding public opinion that is the primary source of environmental legitimacy pressure for a firm. Compared to non-politically-connected firms, politically-connected firms attract more media attention [Citation43]. In addition, political connection increases firms’ visibility and, thus, politically-connected firms are expected to take more social responsibilities and have a higher level of compliance with law and social norms [Citation44]. Therefore, compared to non-politically-connected firms, politically-connected firms have higher environmental legitimacy pressure than do non-politically-connected firms. We, thus, propose our second hypothesis as follows:

H2. Political connection moderates the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure, that is, the positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure in politically-connected firms is stronger than that in non-politically-connected firms.

Research design

Sample and data

In 2011, the State Council issued The Notice on the Pilot Work of Carbon Emission Trading (henceforth, The Notice). The purpose of issuing The Notice was to facilitate the establishment of carbon emission trading market which eventually covers eight major energy-intensive industries including electric power, chemicals, petrochemicals, aviation, paper making, nonferrous metal, steel, building materials. This study selects firms from these eight major energy-intensive industries that provide CSR reports from 2015 to 2019. After deleting firms with missing key variables and firms with special treatment, we obtain a panel data with 748 firm-year observations, including 134 observations in 2015, 136 observations in 2016, 152 observations in 2017, 161 observations in 2018, and 165 observations in 2019, respectively.

We manually collect information on environmental legitimacy pressure and carbon information disclosure. Specifically, we first obtain data on environmental legitimacy pressure by counting the number of environmental news in the China Economic News (CEN) database. Then, we obtain data on impression management of carbon information disclosure by reading the description on firms’ environmental performance presented in CSR reports which are collected from cninfo.com. The data on political connection is collected from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database and the Dongfang.com. Finally, financial information and data on corporate governance are collected from CSMAR database. Data management and analyses are performed using Stata 16.0.

Variable definition

Impression management of carbon information disclosure

Luo et al. [Citation15] have constructed a measurement index system for impression management of carbon information disclosure. The measurement index system includes 12 items covered by five categories including balance, comparability, accuracy, reliability and integrity. See for details.

Table 1. Measurement index system for impression management of carbon information disclosure.

Following Luo et al’ approach [Citation15], we design the measurement for impression management of carbon information disclosure in our setting by the following procedures. In the process of obtaining data on impression management, two raters read the information disclosed by firms using content analysis, and a third party reconciles any differences between them. Specifically, first, we carefully read the section of environmental disclosure presented in CSR reports and divide environmental disclosure into symbolic disclosure and substantive disclosure by judging whether the disclosure is “window dressing” or “real action”. If a firm uses simple or general descriptions, repeats the previous year’s statements, and presents information that is difficult to verify or easy to imitate, then, the environmental information disclosed by this firm is considered a symbolic disclosure. The following is an example of symbolic disclosure:

“The firm takes environmental protection, energy conservation and low-carbon production as a long-term development strategy…Against the background of reducing carbon emission nationwide, the firm actively responds to the national policy of addressing climate issues, develops renewable energy, and improves the efficiency in resource utilization.”

Meanwhile, if a firm uses factual statements, case descriptions, quantitative descriptions, and presents information that is verifiable and hard-imitable, then, the environmental information disclosed by this firm is considered a substantive disclosure. The following is an example of substantive disclosure:

“The firm has invested RMB 745 million in purchasing new equipment or developing new technology to improve the efficiency in resource utilization this year. By doing so, the firm has saved a total of 400 million kwh of electricity and 1,525 million tons of standard coal, which translates into a reduction of 747,700 tons of carbon dioxide emission.”

In the case of a symbolic disclosure, the value is set to 1 for symbolic disclosure and 0 for substantive disclosure; whereas, in the case of a substantive disclosure, the value is set to 1 for substantive disclosure and 0 for symbolic disclosure.

Second, we further divide impression management of carbon information disclosure into two types: selective disclosure and expressive manipulation. Selective disclosure refers that a firm does not disclose specific information on the performance of carbon emission reduction if it fails to meet relevant requirements. Expressive manipulation is a symbolic disclosure that uses simple qualitative descriptions. Then, we define the degree of selective disclosure as the ratio of the number of undisclosed items to the total number of items that should be disclosed (i.e. the 12 items presented in ), and define expressive manipulation as the ratio of the number of symbolically disclosed items (i.e. symbolic disclosures) to the number of all disclosed items as follows:

Finally, the degree of impression management of carbon information disclosure (C_imp) is obtained through geometric averaging:

(1)

(1)

Environmental legitimacy pressure

Media represents an appropriate source to assess firms’ environmental legitimacy pressure [Citation35]. Existing literature uses media coverage to measure firms’ environmental legitimacy pressure. For example, Kuo and Yi-Ju Chen [Citation45] classify media reports into neutral, negative, and positive ones, and use these types of media reports to proxy for environmental legitimacy pressure; Bansal and Clelland [Citation34] use the number of media reports to measure environmental legitimacy pressure. Following the above literature, we construct the measure for environmental legitimacy pressure by the following procedures. First, we collect media reports containing the keywords such as carbon, environment, energy, sustainable, for the sample firms. These media reports are obtained from CEN which is an authoritative database in China and covers more than 1,000 national and local newspapers. Then, we define an indicator variable, denoted by ELP_dum, which takes 1 if a firm is reported by media in a given year and 0 otherwise. Finally, we define a continuous variable, denoted by ELP, as the natural logarithm of one plus the number of media reports. ELP captures the intensity of environmental legitimacy pressure.

Political connection

Following prior literature (e.g. Fan et al. [Citation46], Luo and Liu [Citation47], Zhang et al. [Citation48]), we measure political connection as follows. First, we create an indictor variable to proxy political connection, denoted by PC. We trace the political connection status of the chairperson and/or chief executive officer (CEO) in a firm by examining whether he or she worked for or is working for governments, procuratorates, courts, party committees, standing committees of people’s congress, and standing committees of Chinese people’s political consultative conference. If so, PC takes 1, and 0 otherwise.

Second, we create two continuous variables to capture the strength of political connection of the chairperson and/or CEO in a firm, denoted by PCS1 and PCS2. In China, civil servants work for governments, procuratorates and courts have four hierarchies including section-level officials, division-level officials, department-level officials, and ministry-level officials. If the chairperson and/or CEO worked for or is working for governments, procuratorates or courts, we assign values to PCS1 according to the above four levels. Specifically, PCS1 is set to 1 if the chairperson and/or CEO was or is a section-level official, PCS1 is set to 2 if the chairperson and/or CEO was or is a division-level official, PCS1 is set to 3 if the chairperson and/or CEO was or is a department-level official, PCS1 is set to 4 if the chairperson and/or CEO was or is a ministry-level official, and PCS1 is set to 0 if the chairperson and/or CEO never worked for governments, procuratorates and courts. It is worth mentioning that the functions of governments, procuratorates and courts are significantly different from those of party committees, standing committees of people’s congress, and standing committees of Chinese people’s political consultative conference. The functions of the former ones focus on the administration of public affairs, legal supervision and judicial duties, while those of the later ones focus on inspection and legislation. People work for these committees are called representatives who have four hierarchies including county-level representatives, city-level representatives, province-level representatives and nation-level representatives. If the chairperson and/or CEO worked for or is working for party committees, standing committees of people’s congress, and standing committees of Chinese people’s political consultative conference, we assign values to PCS2 according to the above four levels. Specifically, PCS2 is set to 1 if the chairperson and/or CEO was or is a county-level representative, PCS2 is set to 2 if the chairperson and/or CEO was or is a city-level representative, PCS2 is set to 3 if the chairperson and/or CEO was or is a province-level representative, PCS2 is set to 4 if the chairperson and/or CEO was or is a nation-level representative, and PCS2 is set to 0 if the chairperson and/or CEO never worked for party committees, standing committees of people’s congress, and standing committees of Chinese people’s political consultative conference.

Finally, given that the four hierarchies of the officials working for governments, procuratorates and courts are equivalent to the four hierarchies of the representatives working for party committees, standing committees of people’s congress, and standing committees of Chinese people’s political consultative conference, we use the maximum value of either PCS1 or PCS2 to measure the strength of firms’ political connection, denoted by PCS. PC and PCS serve as the moderators in this study.

Control variables

There are several factors shown to affect a firm’s carbon information disclosure strategy. Following prior literature (e.g. Luo et al., [Citation15], Huang et al., [Citation2], Aerts and Cormier [Citation49]), we control for firm size (Size), leverage (Lev), return on assets (ROA), institutional investor ownership (InstOwn), market-to-book ratio (MTB), firm growth (Growth), the largest shareholder’s ownership (Top1), executive compensation (Pay), proportion of independent directors (IndpSize). See the detailed definition of control variables in .

Table 2. Variable definition.

Model construction

To test the impact of environmental legitimacy pressure on impression management of carbon information disclosure (i.e. H1), we construct the following model:

(2)

(2)

Where C_imp is the dependent variable (i.e. impression management of carbon information disclosure), ELP_dum (ELP) is the independent variable (i.e. environmental legitimacy pressure), Control represents Control variable, Year and Industry refer to year and industry fixed effects. According to H1, we expect the coefficient, to be significantly positive.

To examine the moderating effect of political connection on the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure (i.e. H2), we construct the following model:

(3)

(3)

Where PC and PCS represent political connection, ELP_dum (ELP) × PC (PCS) is the interaction between ELP_dum (ELP) and PC (PCS). According to H2, we expect the coefficient, to be significantly positive.

Empirical results

Descriptive statistics

reports the descriptive statistics of the variables used in this study. The mean value of impression management of carbon information disclosure (C_imp) is 61.88, indicating that impression management on carbon information disclosure does exist, and its degree is relatively large. Its standard deviation is 31.46, indicating that there is a large variation in impression management of carbon information disclosure. These results are similar with those reported by Luo et al [Citation15]. The mean value of ELP_dum is 0.59, indicating that around 60% of the sample firms is subject to environmental legitimacy pressure. The mean value and standard deviation of ELP are 0.64 and 0.62, respectively, indicating that different firms have different level of environmental legitimacy pressure and they show a large variation in environmental legitimacy pressure. The mean value of PC is 0.29, indicating that around 30% of sample firms have political connection. The mean value and standard deviation of PCS are 0.86 and 1.44, respectively, indicating that firms show a large variation in the strength of political connection. The mean value of State is 0.65, indicating that SOEs account for about two-thirds of the sample firms. The statistical distributions of other control variables are shown in .

Table 3. Descriptive statistics.

Regression results

Baseline results

reports the multiple regression results of the impact of environmental legitimacy pressure on the impression management of carbon information disclosure. The estimated coefficients on ELP_dum and ELP are 9.779 and 9.619, respectively, and both are statistically significant at the 1% level. These results suggest that, when facing higher environmental legitimacy pressure, firms conduct more impression management on carbon information disclosure, which is consistent with the theoretical expectation of H1.

Table 4. Baseline results.

Moderating effect of political connection

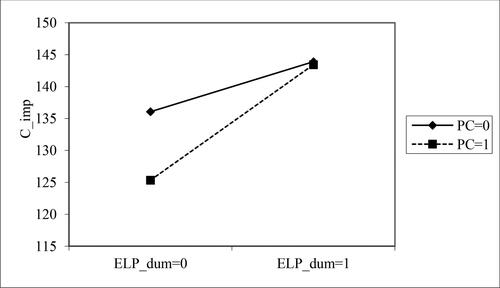

reports the moderating effect of political connection by estimating model (3). Column (1) and (2) show that the estimated coefficients on ELP_dum × PC and ELP × PC are 10.257 and 9.984, respectively, both are statistically significant at the 5% level. Column (3) and (4) show that, the estimated coefficients on ELP_dum × PCS and ELP × PCS are 3.100 and 3.201, and statistically significant at the 10% and 5% level, respectively. These results suggest that the positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure in politically-connected firms is stronger than in non-politically-connected firms, which is consistent with the theoretical expectation of H2.

Table 5. Moderating effect political connection.

For clarity, graphically illustrates the moderating effect of political connection (PC) on the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure (ELP_dum) and impression management of carbon information disclosure (C_imp). It can be seen from that the slope of the dash line (PC = 1) is larger than that of the solid line (PC = 0), suggesting that the positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure in politically-connected firms is stronger than that in non-politically-connected firms, which further supports H2.

Robustness tests

To ensure the robustness of our empirical results, we conduct robustness tests as follows.

Controlling firm fixed effects. To control for the potential unobservable omitted variables that might affect both environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure, we include additional firm fixed effect in our baseline model to account for time invariant heterogeneity across firms. The results in columns (1) and (2) in show that the coefficients on ELP_dum and ELP are 6.979 and 8.832, respectively, and both are statistically significant at the 1% level, consistent with the baseline results.

Logit model test. In the baseline model (a linear regression model), impression management of carbon information disclosure (C_imp) is a continuous variable, and the coefficients are estimated using ordinary least squares method. To check the robustness of the baseline results, we create an indicator variable to measure impression management of carbon information disclosure, denoted by C_imp_dum. C_imp_dum takes 1 if the value of impression management of carbon information disclosure is greater than the sample mean and 0 otherwise. We construct a logit model with discrete dependent variables, and then re-examine H1. The results in columns (3) and (4) in show that the estimated coefficients on ELP_dum and ELP are 0.666 and 0.626, respectively, and both are statistically significant at the 1% level. These results are consistent with those reported in the baseline model.

Inspection of the main industries. To check the robustness of the results of environmental legitimacy pressure on impression management of carbon information disclosure in the main energy-intensive industries, we select sample firms from steel, chemical, electric and nonferrous metal industries which generate serious environmental pollution. There are 647 firm-year observations in these industries, accounting for 86.5% of all sample firms. The results in columns (5) and (6) in show that the estimated coefficients on ELP_dum and ELP are 10.224 and 10.033, respectively, and both are statistically significant at the 1% level, consistent with the baseline results.

Table 6. Regression results of robustness test.

Further analyses

(1) The effect of state ownership. The heterogeneity of state and non-state ownership is a notable feature for Chinese listed firms. Both SOEs and non-SOEs play an essential role in China’s economic development. Prior literature argues that SOEs and non-SOEs have different CSR performances for the following reasons [Citation50]. First, SOEs and non-SOEs have different business objectives. The objective of SOEs is not only to pursue profit but also to achieve a harmonious development among society, economy and environmental [Citation51]. However, non-SOEs have a stronger profit-orientation goal [Citation52] which is unfavorable for carbon information disclosure. Second, SOEs and non-SOEs have different resource endowments to deal with pressure. Relative to non-SOEs, SOEs are more likely to receive political support and financial resources from the government [Citation53] because the government has motivation to bail out SOEs [Citation54]. Third, SOEs have more accesses to finance because stock market regulators and the state-owned commercial banks may give preference to SOEs for political objectives [Citation55]. Moreover, non-SOEs are limited in their ability to deal with environmental issues due to the long-term resource shortage and financing distress [Citation56]. To acquire organizational legitimacy, non-SOEs have motivation to disclose environmental information with impression management. Based on the above analysis, it is necessary to further explore the differential impact of environmental legitimacy pressure on impression management of carbon information disclosure between SOEs and non-SOEs.

reports results. Column (1) and (2) show that the estimated coefficients on ELP_dum for SOEs and non-SOEs are 7.159 and 14.502, and statistically significant at the 5% and 1% level, respectively. Column (3) and (4) show that the estimated coefficients on ELP for SOEs and non-SOEs are 6.747 and 14.929, respectively, and statistically significant at the 5% and 1% level, respectively. Moreover, the empirical p-values obtained from Fisher’s Permutation tests are less than 5%. These results indicate that the positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure in non-SOEs is stronger than that in SOEs.

Table 7. Regression results for SOEs and non-SOEs.

(2) The effect of different types of environmental legitimacy pressure. Following Kuo and Chen [45] and Bansal and Clelland [Citation34], we further explore the effect of different types of environmental legitimacy pressure on impression management of carbon information disclosure. In terms of the types of environmental legitimacy pressure, if a media report conveys a firm’s commitment to environmental protection or highlights a firm’s positive environmental behavior, the news is considered to be positive; if a media report has no significant emotional effect on a firm’s environmental image, the news is considered to be neutral; if a media report conveys a firm’s behavior that damages the firm’s environmental image, the news is considered to be negative. A total of 991 relevant reports are selected, and each report is coded for whether its impact on a firm’s environmental image is positive, neutral or negative. Then, we calculate the natural logarithm of one plus each of the above types of environmental legitimacy pressure, denoted by PosNews, NeuNews and NegNews, respectively.

reports the results. Column (1) shows that the estimated coefficients on PosNews and NegNews are 5.795 and 16.868, and statistically significant at the 5% and 1% level, respectively; the estimated coefficient on NeuNews is 1.567, but not statistically significant. These results suggest that, when facing higher negative environmental legitimacy pressure, they have stronger motivation to conduct impression management on carbon information disclosure.

Table 8. The effect of different types of environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management strategies of carbon information disclosure.

(3) The effect of different impression management strategies of carbon information disclosure. Impression motivation determines impression management behavior. In order to build up a green impression, firms may conduct either protective impression management or acquired impression management. The former refers that firms adopt the strategy of selective disclosure (i.e. “reporting good news but not bad news”), and the latter refers that firms adopt the strategy of expressive manipulation (i.e. “inconsistency between words and deeds”). We further differentiate selective disclosure (CS_imp) and expressive manipulation (CE_imp), and rerun the baseline model using CS_imp and CE_imp as dependent variables.

reports the results. Column (2) and (3) show that the estimated coefficients on ELP_dum are 1.874 and 11.790, and statistically significant at the 5% and 1% level, respectively. These results suggest that environmental legitimacy pressure leads firms to conduct both selective disclosure and expressive manipulation, and that firms have stronger motivation to conduct expressive manipulation than to conduct selective disclosure. The results in columns (4) and (5) are consistent with the findings in columns (2) and (3).

Discussion and conclusion

Using firms in China’s eight energy-intensive industries from 2015 to 2019 as research samples, this study examines the impact of environmental legitimacy pressure on impression management of carbon information disclosure, and investigates the moderating effect of political connection. The results show that environmental legitimacy pressure is positively associated with impression management of carbon information disclosure, and political connection moderates this relationship, that is, the positive association in politically-connected firms is stronger than that in non-politically-connected firms. Further analyses show that (i) The positive association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure in non-SOEs is stronger than that in SOEs, (ii) firms subject to higher negative environmental legitimacy pressure have stronger motivation to conduct impression management of carbon information disclosure, (iii) firms subject to environmental legitimacy pressure conduct both selective disclosure and expressive manipulation but they have stronger motivation to conduct expressive manipulation than to conduct selective disclosure.

Our findings have two academic implications. First, this study contributes to the literature on non-economic consequences of environmental legitimacy pressure. Most of existing literature on environmental legitimacy pressure only focuses on its economic consequences. This study is the first to report an association between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure and, thus, extends the research on environmental legitimacy pressure.

Second, this study contributes to the literature on the determinants of impression management of carbon information disclosure. We explore the relationship between environmental legitimacy pressure and impression management of carbon information disclosure, and consider the moderating role of political connection on this relationship. This study offers a framework and expands research on the determinants of impression management of carbon information disclosure.

Our findings provide important policy implications not only for China but also for other countries with large carbon emission. First, this study helps the government better understand firms’ impression management on carbon information disclosure. Our findings show that firms with higher environmental legitimacy pressure will conduct more impression management on carbon information. Due to the lack of guidelines/standards for carbon information disclosure and independent auditing, manipulating environmental information disclosure is hard to be detected by external stakeholder and regulator. Impression management makes carbon information disclosure ineffective, which might cause resource misallocation and even harm the efficiency in carbon management of the whole society. Thus, regulators should issue detailed guidelines/standards for carbon information disclosure. Moreover, the moderating effect analysis suggests that political connection acts as a corporate shield which could protect a firm from being punished for the manipulation of carbon information disclosure. Thus, regulators should strengthen the regulation on firms’ impression management on carbon information disclosure in politically-connected firms.

Second, the findings in our study are helpful for investors to identify and invest in firms with an accurate carbon footprint. Most investors use the carbon information disclosed by firms to evaluate firms’ performance of carbon management. This study demonstrates that firms conduct impression management on carbon information disclosure to relieve environmental legitimacy pressure, which biases investors’ evaluation on firms’ carbon management. Thus, when evaluating firms’ performance of carbon management, investors need to identify firms’ impression management strategies, i.e. symbolic disclosure or expressive manipulation. The measurement index system for impression management of carbon information disclosure constructed by this study suggests that investors should pay attention to the twelve indicators (see details in ) to improve their ability to identify firms’ impression management on carbon information disclosure.

Third, with increasingly stringent environmental regulations, firms committing to protecting environment are more likely to obtain organizational legitimacy. However, impression management of carbon information disclosure is only a short-term rather than a long-term strategy for firms. Thus, firms with a sustainable development philosophy should improving carbon performance by investing in “real green” activities.

This study nevertheless has some limitations. First, the samples used in this study are obtained from eight energy-intensive industries. Since energy-intensive industries comprise only a particular type of industries, future research should examine whether our conclusions regarding impression management of carbon information disclosure are applied to other types of industries. Second, this study has only examined the external determinant of impression management of carbon information disclosure from the perspective on environmental legitimacy pressure. Thus, further work is needed to explore internal determinants such as firm characteristics, managers’ personal background, and corporate governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author, Wei Liu, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wang K, Liu YY. Review and prospect of China’s carbon market in 2020. J Beijing Inst Technol. 2020;22(2):10–19.

- Huang YX, Yao Z. Corporate social responsibility reporting, impression management and firm performance. Econ Manag. 2016;38(1):105–115.

- Peters GF, Romi AM. Does the voluntary adoption of corporate governance mechanisms improve environmental risk disclosures? Evidence from greenhouse gas emission accounting. J Bus Ethics. 2014;125(4):637–666. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1886-9.

- Luo L, Tang Q. Does voluntary carbon disclosure reflect underlying carbon performance? J Cont account Econ. 2014;10(3):191–205. doi:10.1016/j.jcae.2014.08.003.

- Depoers F, Jeanjean T, Jérôme T. Voluntary disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions: Contrasting the carbon disclosure project and corporate reports. J Bus Ethics. 2016;134(3):445–461. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2432-0.

- Chen H, Wang HY, Jing X. Corporate carbon disclosure in China: content definition, measurement methods, and current status. Account Res. 2013;314(12):18–24+96.

- Leary MR, Kowalski RM. Impression management: a literature and two component model. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(1):34–47. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.34.

- Allen MW, Caillouet RH. Legitimation endeavors: Impression management strategies used by an organization in crisis. Commun Mon. 1994; 61(1):44–62. doi:10.1080/03637759409376322.

- Zhang ZY, Qiu JT. Accounting conservatism, corporate governance and social responsibility report impression management. Financ Theory Pract. 2017; 38(3):77–83.

- García-Sánchez IM, Suárez-Fernández O, Martínez-Ferrero J. Female directors and impression management in sustainability reporting. Int Bus Rev. 2019;28(2):359–374. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.10.007.

- Diouf D, Boiral O. The quality of sustainability reports and impression management. AAAJ. 2017;30(3):643–667. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-04-2015-2044.

- Dhaliwal DS, Li OZ, Tsang A, et al. Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity Capital: the initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Account Rev. 2011;86(1):59–100. doi:10.2308/accr.00000005.

- Talbot D, Boiral O. Strategies for climate change and impression management: a case study among canada’s large industrial emitters. J Bus Ethics. 2015;132(2):329–346. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2322-5.

- Talbot D, Boiral O. GHG reporting and impression management: an assessment of sustainability reports from the energy sector. J Bus Ethics. 2018;147(2):367–383. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2979-4.

- Luo X, Zhang Q, Zhang S. External financing demands, media attention and the impression management of carbon information disclosure. Carbon Manage. 2021:1–13. doi:10.1080/17583004.2021.1899755.

- Li D, Huang M, Ren S, et al. Environmental legitimacy, green innovation, and corporate carbon disclosure: Evidence from CDP China 100. J Bus Ethics. 2018;150(4):1089–1104. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3187-6.

- Hrasky S. Carbon footprints and legitimation strategies: symbolism or action? Acc Audit Account J. 2012;25(1):174-198. doi:10.1108/09513571211191798.

- Li XY, Shi YY. Green development, quality of carbon information disclosure and financial performance. Econ Manag. 2016;38(7):119–132.

- Fisman R. Estimating the value of political connections. Am Econ Rev. 2001;91(4):1095–1102. doi:10.1257/aer.91.4.1095.

- Mahadeo JD, Oogarah-Hanuman V, Soobaroyen T. Changes in social and environmental reporting practices in an emerging economy (2004–2007): exploring the relevance of stakeholder and legitimacy theories. Account Forum. 2011;35(3):158–175. doi:10.1016/j.accfor.2011.06.005.

- Suchman MC. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad Manage Rev. 1995;20(3):571–610. doi:10.2307/258788.

- Mei XH, Ge Y, Zhu XN. Research on the influence mechanism of environmental legitimacy pressure on corporate carbon information disclosure. Soft Sci. 2020;34(8):78–83.

- He P, Shen H, Zhang Y, et al. External pressure, corporate governance, and voluntary carbon disclosure: Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2019;11(10):2901. doi:10.3390/su11102901.

- Lewis BW, Walls JL, Dowell GWS. Difference in degrees: CEO characteristics and firm environmental disclosure. Strat Mgmt J. 2014;35(5):712–722. doi:10.1002/smj.2127.

- Testa F, Boiral O, Iraldo F. Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders pressures encourage greenwashing? J Bus Ethics. 2018;147(2):287–307. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2960-2.

- Cho CH, Patten DM. The role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: a research note. Account Organ Soc. 2007;32(7–8):639–647. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2006.09.009.

- Luo L, Lan YC, Tang Q. Corporate incentives to disclose carbon information: Evidence from the CDP global 500 report. J Int Financ Manage Account. 2012;23(2):93–120. doi:10.1111/j.1467-646X.2012.01055.x.

- Ben‐Amar W, McIlkenny P. Board effectiveness and the voluntary disclosure of climate change information[J]. Bus Strat Env. 2015;24(8):704–719. doi:10.1002/bse.1840.

- Shen HT, Feng J. Public opinion supervision, government regulation and enterprise environmental information disclosure. Account Res. 2012;292(2):72–78+97.

- Huang RB, Chen W, Wang KH. External financing demand, impression management and corporate green-bleaching. Comp Econ Soc Syst. 2019;203(3):81–93.

- Jensen MC, Meckling WH. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ. 1976;3(4):305–360. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X.

- Li DY, Huang M, Zhou ZF. The influence of organizational legitimacy on corporate carbon information disclosure: Evidence from CDP China 100. Res Dev Manag. 2016;28(5):44–54.

- Giannarakis G, Zafeiriou E, Arabatzis G, et al. Determinants of corporate climate change disclosure for European firms. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Mgmt. 2018;25(3):281–294. doi:10.1002/csr.1461.

- Bansal P, Clelland I. Talking trash: Legitimacy, impression management, and unsystematic risk in the context of the natural environment. Acad Manage J. 2004;47(1):93–103. doi:10.2307/20159562.

- Connelly BL, Certo ST, Ireland RD, et al. Signaling theory: a review and assessment. J Manag. 2011;37(1):39–67. doi:10.1177/0149206310388419.

- Peng MW, Luo Y. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: the nature of a micro-macro link. Acad Manage J. 2000;43(3):486–501. doi:10.2307/1556406.

- Yao S. Political connections, environmental information disclosure and environmental performance: Based on data from listed companies in China. Finan Trade Res. 2011;22(4):75-85.

- Lin RH, Xie ZX, Li Y, et al. Environmental information disclosure: a perspective of resource dependence theory. J Public Admin. 2015;12(2):30–41.

- De Villiers C, Naiker V, Van Staden CJ. The effect of board characteristics on firm environmental performance. J Manag. 2011;37(6):1636–1663. doi:10.1177/0149206311411506.

- Choi CJ, Lee SH, Kim JB. A note on countertrade: contractual uncertainty and transaction governance in emerging economies. J Int Bus Stud. 1999;30(1):189–201. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490066.

- Fang Y, Guo JJ. Effectiveness of environmental information disclosure policy in China: a study based on Capital market reaction. Econ Res J. 2018;53(10):158–174.

- Lei QH, Luo DL, Wang J. Environmental regulation, political relevance and enterprise value: Evidence from china's listed companies. J Shanxi Univ Financ Econ. 2014;36(9):81–91.

- Yi FP, Xu EM. Corporate social responsibility and corporate political connection: a case study of China's listed companies. Econ Manage Res. 2014;(5):5–13.

- Greening DW, Gray B. Testing a model of organizational response to social and political issues. Acad Manage J. 1994;37(3):467–498. doi:10.2307/256697.

- Kuo L, Chen VYJ. Is environmental disclosure an effective strategy on establishment of environmental legitimacy for organization? Manag Decis. 2013;51(7):1462–1487. doi:10.1108/MD-06-2012-0395.

- Fan JPH, Wong TJ, Zhang T. Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and Post-IPO performance of China's newly partially privatized firms. J Financ Econ. 2007;84(2):330–357. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.03.008.

- Luo XY, Liu W. Political connections and corporate environmental violations: Evidence from the IPE database. J Shanxi Univ Financ Econo. 2019;41(10):85–99.

- Zhang W, Zhang S, Li BX. Political connection, M&a characteristics and M&a performance. Nankai Manage Rev. 2013;16(2):64–74.

- Aerts W, Cormier D. Media legitimacy and corporate environmental communication. Account Organ Soc. 2009;34(1):1–27. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2008.02.005.

- Tan X. Industry competition, state ownership and corporate social responsibility information disclosure: an analysis based on signaling theory. Ind Econ Res. 2017;88(3):15–28.

- Atkinson AB, Stiglitz JE. Lectures on public economics: Updated edition. Princeton Univ Press;Princeton, 2015.

- Liu X, Zhang C. Corporate governance, social responsibility information disclosure, and enterprise value in China. J Clean Prod. 2017;142(2):1075–1084. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.102.

- Li Q, Luo W, Wang Y, et al. Firm performance, corporate ownership, and corporate social responsibility disclosure in China. Bus Ethics Eur Rev. 2013;22(2):159–173. doi:10.1111/beer.12013.

- Brandt L, Li H. Bank discrimination in transition economies: ideology, information, or incentives? J Comp Econ. 2003;31(3):387–413. doi:10.1016/S0147-5967(03)00080-5.

- Aharony J, Lee CWJ, Wong TJ. Financial packaging of IPO firms in China. J Account Res. 2000;38(1):103–126. doi:10.2307/2672924.

- Kong DM, Liu SS, Wang YN. Market competition, state ownership and government subsidies. Econ Res. 2013;48(2):55–67.