ABSTRACT

The paper explores the historical and archaeological evidence for maternal and infant death in medieval Ireland. An overview of a range of historical sources including law tracts, medical documents, and folklore are investigated for insights concerning the treatment of pregnant women, abortion, post-mortem caesarean, and the nature of herbs that were administered to assist with female reproductive matters. This provides the context for a review of 15 earlier and later medieval burial grounds in Ireland that produced 30 burials in which an adult female was associated with one or more foetal or perinatal infants. The individuals are considered to have potentially died as a result of obstetric complications. The overall frequency and age-at-death profiles of the women and babies are investigated. This is followed by an attempt to interpret the circumstances of each case to determine whether the death had occurred during pregnancy, childbirth or shortly after birthing.

Introduction

In the modern world issues such as birth control, abortion and the decision to have children are all topics of much discussion and are connected to a variety of moral debates.Footnote1 While the context may be very different – effective contraception and safe abortions are available and mothers very rarely die due to pregnancy or childbirth in the Western world – medieval people would have faced similar concerns (Gottlieb Citation1993, 113–114). It is difficult to find direct evidence in the archaeological evidence in relation to contraceptives and abortion, although valuable insights can be gained from historical sources. Increasingly, archaeologists are turning their attention to the experiences of mothers and the physical bond that exists between them and their children. The impact of pregnancy on the female body, the emotions experienced at the loss of a baby, breastfeeding practices and the overall care they would have afforded their children are all topics that have been explored (see e.g. Gowland and Halcrow Citation2020). In addition, a new palaeodemographic technique has been devised that, when used in combination with traditional palaeopathological approaches, can enable an estimation of maternal mortality rates to be gained for past populations (McFadden and Oxenham Citation2019; McFadden, Van Tiel, and Oxenham Citation2020). Burials of women with an unborn or newly delivered baby can provide a poignant reminder of the hazards of pregnancy and childbirth in the past. Halcrow, Tayles, and Elliott (Citation2018) undertook a comprehensive global review of the evidence for archaeological mother-infant burials and demonstrated how these could include cases of death during pregnancy or shortly after birthing. The current paper will build upon this review and will explore the evidence of maternal and infant death in medieval Ireland.

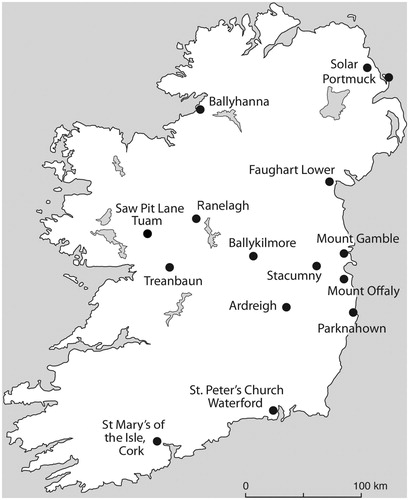

Maternal death, as defined by the World Health Organisation (Citation2019, 8), can be summarized as the death of a woman during pregnancy, regardless of duration, or within 42 days of delivery, with the death directly related to the pregnancy and not due to incidental causes. A direct maternal death is one clearly connected to the pregnancy, while an indirect one involves a previous condition that was aggravated by the pregnancy. The study investigates data collected from 15 burial grounds across Ireland containing the remains of one or more women who can be identified as potential direct maternal deaths (). A late medieval pregnant woman from the burial ground at Tonybaun, Co. Mayo, was excluded from the study because she displayed sharp force trauma to her cranium that had caused her death and was thus not a direct maternal death (Murphy Citation2004). Many of the sites were in use over protracted periods of time and the burials included range in date from approximately AD 450–1700, thereby spanning both the early and later medieval periods. The burial grounds were of a variety of forms, and included churchyards, the interior of ecclesiastical enclosures, and settlement cemeteries (see O’Sullivan et al. Citation2014). It is possible that local cultural influences would have impacted upon the people interred within each burial ground, but this is difficult to examine in the archaeological record. The later medieval population buried at Ardreigh, Co. Kildare (Moloney et al. Citation2012), for example, would have lived in an area largely controlled by the Anglo-Normans in the wake of their invasion in the late twelfth century, whereas those interred at Ballyhanna, Co. Donegal, would have lived in an area under Gaelic control (McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018). Women clearly conceived and birthed babies in all of these cultural groups but the stories of those who died when pregnant or during, or shortly after, the birthing process have been scattered in site-specific reports or publications. As such, this paper examines data derived from the osteoarchaeological and burial records in relation to unsuccessful pregnancies and births to gain insights concerning the risks associated with motherhood at this time. Information obtained from relevant historical sources is included to provide a context within which the osteoarchaeological findings may be further understood.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of the sites which contained the remains of one or more maternal-infant deaths (prepared by Libby Mulqueeny).

The methods used by all of the osteoarchaeologists whose data are referred to in the paper conformed to professional guidelines (e.g. Mitchell and Brickley Citation2017). Adult sex determination was based on sexually dimorphic morphological traits of the pelvis and skull (Phenice Citation1969; Ferembach, Schwidetzky, and Stloukal Citation1980). Adult age-at-death determination was derived from assessment of late fusing epiphyses (Scheuer and Black Citation2000), degenerative changes of the auricular surfaces (Lovejoy et al. Citation1985) and pubic symphyses (Brooks and Suchey Citation1990), as well as dental attrition (Brothwell Citation1981). The age-at-death values of the fetal and perinatal infants were obtained on the basis of the regression equations of Scheuer, Musgrave, and Evans (Citation1980) and the recommendations of Scheuer and Black (Citation2000). Preterm babies are defined as those with an age-at-death less than 37 weeks, and who probably would have been insufficiently developed to have survived in the past, while full term individuals are those aged around 37–42 weeks. The perinatal period is considered to last from around 24 weeks gestation to seven post-natal days, while the neonatal periods extends from birth to 28 days (Scheuer and Black Citation2000, 468).

Historical sources

In her review of Gaelic legal texts dating from the seventh century up until AD 1200, Ní Chonaill (Citationforthcoming) has uncovered a wealth of information in relation to children. The tracts indicate that procreation was an expected aspect of married life. Lawyers were concerned with the working conditions of pregnant women and, in one account, it was recommended that the duties of a pregnant servant should be covered by another, at the expense of the father of the child, for a period of one month prior to delivery and a further one month post-natal. Pregnant women were not to be deprived of the food they needed to keep them and their unborn child healthy (Ní Chonaill Citationforthcoming, 4); if a pregnant woman desired a morsel of food it could be taken without any penalty (Kelly Citation1995, 154). The tracts demonstrate an awareness of the danger of death at, or around, the time of childbirth and, indeed, the seventh-century Cáin Adomnáin infers that a death of this nature was a normal associated danger for a married woman. In general terms, the writings of the lawyers are indicative of concern for the well-being of the pregnant woman and the unborn child (Ní Chonaill Citationforthcoming, 6).

Some early medieval religious texts, particularly hagiographies and penitentials, suggest that not all pregnancies were welcomed, however, and abortions seem to have been practiced. The accounts refer to notable miraculous abortions occurring during the fifth and sixth centuries in the wake of a simple blessing from one of Ireland’s four abortionist saints – Ciarán of Saigir, Áed mac Bricc, Cainnech of Aghaboe and Brigid of Kildare (Callan Citation2012, 289). Other accounts are suggestive that abortion could be induced by physical means and was considered to be a relatively minor sin for which penance was required (Callan Citation2012, 292). The Irish Canons and the Old Irish Penitential both recognized that abortion posed a risk to a woman’s life, however, and those responsible for causing such a death were to undergo penance for a period of 12–14 years (Bieler Citation1963, 161, 272). If a married woman deliberately induced an abortion or killed her child her husband was legally entitled to divorce her (Kelly Citation1995, 84).

The account of the ‘Cath Boinde’ (The Battle of the Boyne) in the Book of Lecan written between AD 1397 and 1418, but seemingly based on much earlier events, discusses how the unborn son of Eithne, the daughter of King Eohaidh Feidlech, was cut from his mother’s womb after she died as a result of deliberate drowning during the latter stages of her pregnancy (O’Neill Citation1905, 177). The story of Feidlech’s unusual birth also features in a story entitled the ‘Carn Furbaidi’ in The Rennes Dindshenchas (Stokes Citation1895, 39). Some researchers have interpreted this account as an indication that caesarean sections were performed (e.g. Joyce Citation1903, 622). The operation in the story was undertaken posthumously, however, and 13 historical documents are known that indicate the practice of ‘sectio in mortua’ (post-mortem caesarean section) occurred in France, Italy and Sweden from the thirteenth century onwards. The demand for the procedure appears to have been linked to concerns for the fate of the soul of the unborn, and therefore unbaptized, infant. The surgery was required to provide the foetus with a chance of salvation through baptism as well as, perhaps, life (Bednarski and Courtemanche Citation2011, 40–41, 63).

Laws were also in place to protect the wellbeing of an infant upon the death of its mother. If the child had not been weaned the onus was on the father to procure a wet nurse and Kelly (Citation1995, 86) notes an entry in the Corpus Iuris Hibernici that makes reference to: ‘distraint to enforce the removal of a child from the dead breast of its mother’.

Early historians of medicine in Ireland largely remain silent on the topic of pregnancy and childbirth. In his volume on Medicine in Antient Erin, for example, the eminent medical historian, Henry S. Wellcome (Citation1909, 42), simply states that ‘midwifery, as with the antient [sic] nations generally, was of a primitive and superstitious character’. Malcolm (Citation2005, 324) discussed the reference to banliaig, or female physicians, in the Brehon laws and noted that, while such individuals may have been midwives, it is likely their skills were more extensive. She observes how the urban guilds of barbers and surgeons admitted females, often the relatives of male members, and how it seems certain that Irish women would have served a variety of medical roles – as healers, herbalists, nurses and midwives – within their communities, despite the scant nature of the surviving evidence (Malcolm Citation2005, 324). The first herbal to concentrate on Irish flora – The Botanalogia Universalis Hibernica – published by John K’Eogh in 1735 includes numerous herbs that appear to have been used by women for a range of purposes, including to either promote menstruation or prevent excess bleeding; to help with conception; to prevent miscarriage; to facilitate labour; to expel the afterbirth; to cure afterbirth pains; to increase the flow of breastmilk; to ease engorged breasts and sore nipples; and to help with uterine conditions, including prolapse. The volume of entries suggest that women suffered from a range of issues, similar to those experienced by modern women, but measures were taken to address the problems experienced and presumably these plants would also have been used by earlier generations. Some 11 herbs are described as helping to expel a dead child from the womb, such as long birthwort, which, when drunk with pepper and myrrh, ‘expels the dead child, the afterbirth and all superfluities of the womb’ (Scott Citation1986, 30). Such references suggest that miscarriages and stillbirths were not uncommon and that attempts were made to encourage birthing so the life of the mother could be saved. While abortion may have been viewed as a sin (excepting the abortionist saints; see above) in medieval Ireland it seems feasible that herbs such as motherwort, that encourage delivery, might also have been used to induce abortion. Similarly, the information provided for black briony, honey-suckle and sow bread, which are each described as being very dangerous for pregnant women, could have been used to cause abortion. It is specifically stated in the entry for savin that it ‘causes abortion’ (Scott Citation1986, 34, 83, 106, 134, 142).

While limited historical accounts relating to pregnancy and childbirth in Ireland exist for the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, they tend to focus on the experiences of upper class women or those of recent settlers to Ireland. When lower class Irish women are mentioned it is usually in their capacity to deliver children with ease – a characteristic considered to be shared with other ‘barbarous’ people, including lower class English women – and this cannot, therefore, be treated as a reliable reflection of the historical reality (Lawrence Citation1988, 74–75; Tait Citation2003, 2–3). Writing in 1670, the English obstetrician, Percivall Willughby, amongst others, was of the view that the ‘wild Irish women’ deliberately fractured the pubic bones of new-born female infants to facilitate their ease of childbirth in the future (Lawrence Citation1988, 73)! An early obstetrical textbook – Speculum Matricis Hybernicum, or, The Irish Midwives Handmaid – by English-born man-midwife, James Wolveridge, was published in Citation1670 when he was practising as a physician in Cork, after having graduated from University College Dublin (Essen-Möller Citation1932, 312). The preface again notes the ease with which lower class Irish women gave birth and, in this instance, is thought to be part of a discourse used by man-midwives to differentiate between the experiences of upper, in this case English, and lower class females. This was then used to argue for the involvement of a man-midwife in the delivery of upper class infants (Murphy-Lawless Citation1991, 291–294).

Despite the chronological separation, oral history accounts recorded between 1935 and 1970 by the Irish Folklore Commission probably have more resonance with the experiences of childbirth by lower class women in medieval Ireland. These women would have given birth in their own homes and been attended by other women. The accounts suggest that it was traditional to give birth on a straw bed, which would have been hygienic and could have been burned or buried along with the afterbirth. The women reported that delivery in a kneeling position was favoured (Nic Suibhne Citation1992, 5–6). Various measures were undertaken to alleviate the pains of labour, including the administration of warm drinks and the ‘involvement’ of the father through the labouring woman wearing a piece of his clothing (Nic Suibhne Citation1992, 5–6). The father could also ‘share’ in the birth pains by undertaking heavy physical tasks, such as carrying buckets of water to and from the house or carrying a heavy stone around the house during his wife’s labour (O’Connor Citation2017, 266). Childbirth was considered to be a dangerous time for mother and baby because of a threat of being taken by the sí (fairies) and objects, including ancient artefacts, were used for apotropaic purposes. A good example of this is an amber bead with an ogham inscription (perhaps of considerable antiquity) from Ennis, Co. Clare, that was reportedly used for generations by the same family in at least the nineteenth century to ensure safe childbirth (Dowd Citation2018, 467–468).

This brief historical overview provides an indication that the risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth were appreciated by the medieval Irish and that concern was shown for the pregnant woman and the unborn baby. Abortions and post-mortem caesareans may have been practiced, as was the case elsewhere in Western Europe (see Gottlieb Citation1993, 118–119, 129). Undoubtedly, a range of herbs would have been used to assist with female reproductive matters since these would have been the main source of medicine available. Aspects of the information from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are largely biased and unreliable since they are written through a lens that includes both colonial and upper class perspectives. The more recent folklore accounts are probably more reliable and we can envisage it would have been a fairly regular and routine occurrence for women to have given birth in their own homes, supported by other women from their community. In the following sections the archaeological evidence for maternal death will be examined to see what insights can be gained in relation to pregnancies that did not have a successful outcome. The issues to be explored include the frequency of maternal death, the age-at-death of the women and infants who died, and the circumstances of their deaths.

Palaeodemographic features of maternal and infant deaths

Prevalence of maternal death

The remains of women who died when pregnant, or during or shortly after delivery, are a relatively rare discovery on archaeological sites and it can be challenging to estimate the maternal mortality rate, or women per 100,000 who died as a result of maternal death, in past populations (McFadden and Oxenham Citation2019, 141). A total of 15 burial grounds in Ireland produced some 30 burials in which an adult female was associated with one or more fetal or perinatal infants and who are considered to have potentially died as a result of obstetric complications (). It was possible to calculate the prevalence for 29 of the maternal deaths and this amount to 1.7% (29/1,759) out of the total number of adult female burials. The maternal death from Stacumny, Co. Kildare, was excluded from this count since the total number of adult females from the site is currently undetermined. A review of maternal deaths in early and later medieval Britain reported crude prevalence rates of 1.7% (11/654) and 0.3% (9/3035) respectively. The findings were considered to notably underrepresent the true prevalence of maternal deaths, however, particularly as the total figures included males and juveniles since the study was not focused solely on maternal death (Roberts and Cox Citation2003, 166, 253–254). The Proportion Maternal (PM) is a modern comparable statistic and it calculates the number of maternal deaths as a proportion of the total number of deaths of women of childbearing age (15–49 years) in a given time period (WHO Citation2019, 10). The highest PM occurs today in sub-Saharan Africa with a staggering 18.2%, whereas the figure for Europe is just 0.5% (WHO Citation2019, 35). It seems highly probable that the PM of 1.7% for medieval Ireland is wholly inaccurate, given the likelihood of inadequate nutrition, poor sanitation, and limited medical knowledge (see McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018). Given the references in medieval Irish literary accounts to the live birth of Eithne’s son after her death (Stokes Citation1895, 39; O’Neill Citation1905, 177) it seems possible that some infants were removed from their dead mother’s womb in an effort to save them (see Bednarski and Courtemanche Citation2011). Detailed archaeothanatological analyses could potentially identify mothers whose babies had been removed in this manner and is the subject of an ongoing research project (see Le Roy and Murphy Citation2020). An additional complication with the figures is that maternal death does not always involve the simultaneous death of the mother and baby, and one may outlive the other. As such, unless the deaths of mother and infant occurred at, or around, the same time they may not have been interred together and will therefore not be recognized archaeologically as mother-infant deaths (see Halcrow, Tayles, and Elliott Citation2018, 89).

Table 1. Summary details of adult female age-at-death values and numbers of maternal deaths.

Maternal age-at-death

The age-at-death of females who suffered maternal deaths can provide insights concerning sociocultural practices relating to marriage and reproductive practices. No definite adolescents appear to have died as a result of obstetric complications in any of the burial grounds and for this reason, as well as the difficulties associated with determining the sex of pubertal adolescents, they were not included in the counts of females of childbearing age. The lack of adolescent maternal deaths is perhaps surprising given information about fosterage practices in historical accounts. When fosterage ended for girls they were expected to either marry or join a religious order but there is some ambiguity as to the age at which this happened, with one text suggesting 14 years of age, and another inferring the period of fosterage was completed at the age of 17 years (Kelly Citation2014, 2; Ní Chonaill Citationforthcoming, 27). It is thought the details of child-rearing outlined in early law tracts relating to fosterage are probably equally applicable to children who were raised with their biological families (Ní Chonaill Citationforthcoming, 11). A number of sixteenth and seventeenth-century English writers suggested that Irish girls physically matured earlier than their English counterparts and were married at the age of 10–12 years, with Luke Gernon stating in the 1620s that they ‘are womene at thirteene and old wives at thirty’. As discussed above, such accounts arise within a genre in which English settlers are viewed as superior to the Irish and they are not considered to be entirely reliable (Lawrence Citation1988, 66–68). The absence of definite adolescent maternal deaths in the burial grounds is suggestive that such young marriage was not practiced and the upper age for the end of fosterage (17 years) may have been more typical. Previous studies have suggested that in medieval Western Europe the first child would have commonly been born in the latter part of the first year of marriage (Gottlieb Citation1993, 115). A modern study of maternal morbidity and mortality in 144 countries, however, has suggested that adolescents are generally not at substantially greater risk of maternal death compared to women aged in their twenties so perhaps Irish medieval females of this age generally survived pregnancy and childbirth. Modern research has demonstrated that the risk of maternal death is higher for younger girls aged less than 15 years (Nove et al. Citation2014, 163), which is again suggestive that Irish medieval females were unlikely to have married at 14 years of age. It is perhaps possible that young adolescents who died when pregnant were treated in a different way to older individuals that makes them invisible in the archaeological record but there is no evidence in the historical sources to suggest that such a differentiation may have occurred.

Age-at-death data was available for 24 of the women and it was apparent that the vast majority of individuals, some 87.5% (21/24), were young adults with an age-at-death of 18–35 years (). SK 505a from Solar, Co. Antrim, was identified as being on the cusp of adulthood with an age-at-death of 16–22 years (Buckley Citation2002, 81), but technically should also be placed within the 18–35 year category because of the greater degree of overlap with the older age group. Similarly, Sk 263 from Ranelagh, Co. Roscommon, was a very young adult with an age-at-death of 17–23 years (Murphy, Loyer, and Drain Citation2020, 69). Only three middle-aged females were identified in the review – F 1226 from Ardreigh, Co. Kildare (Troy 2016 pers. comm.), and SK 60B from Ballyhanna, Co. Donegal (McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018, 68), both of whom were aged 35–50 years, and an individual described as a ‘mature female’ (presumably equating to a woman in her 30s or 40s) from St. Peter’s Church, Waterford (Power Citation1997, 768). In the modern world women aged over 35 years have a notably higher risk of maternal death than younger women of childbearing age (Nove et al. Citation2014, 160). It is quite surprising therefore that more maternal deaths of middle-aged women are not present in the archaeological record, particularly since women of this age group are well represented in the majority of more substantial populations included in the study (see ). Until menopause it would be expected that women had the ability to conceive regularly. Perhaps the paucity of middle-aged females in the corpus is an indicator that poor female health or extended breastfeeding practices reduced fertility or indeed that medieval Irish women controlled their reproductive capabilities, as is hinted at in the historical sources (see above).

Table 2. Summary of the demographic details of the 30 maternal and infant deaths and positions of the babies.

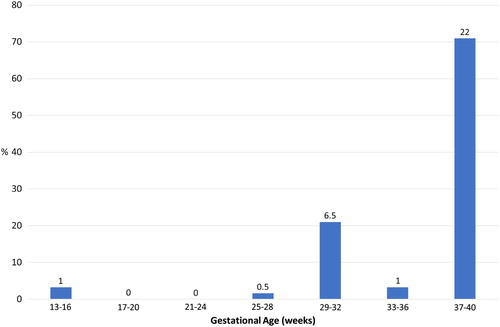

Infant age-at-death

In relation to the 31 infants associated with adult females, nine (29.0%) were aged less than 37 weeks gestation at death, and therefore preterm, with the remaining 22 babies (71.0%) considered to be full term or neonatal. A probable set of twins recovered from Ballyhanna, Co. Donegal, were aged 36 (SK 986) and 37 (SK 978) gestational weeks but they are both included in the full-term category on the basis of the age-at-death of the larger infant (McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018, 66–67). The youngest individual was a foetus from Ardreigh, Co. Kildare, who had died at the age of just 16 weeks gestation, during the early stages of the second trimester of pregnancy (F 5833) (Troy Citation2010, 102).

When the age distribution was examined further it is evident that the first (29–32 weeks) and final thirds (37–40 weeks) of the third trimester were the times of highest risk of death (). The peak in death during the third trimester is not unexpected and most modern maternal-infant deaths occur between the start of the third trimester and the first week post-natal. Reviews of modern maternal deaths in developing countries consistently find that haemorrhage, hypertensive disorders and eclampsia, sepsis/infection, obstructed labour and unsafe abortions are the main contributors. The first and second days after birthing have been shown to be a time of particularly high risk for the mother (e.g. Ronsmans and Graham Citation2006, 1193; Say et al. Citation2014, 326). When the haemorrhage category has been scrutinized in more detail for modern women it has been found that two-thirds of such deaths are caused by post-partum bleeding (Say et al. Citation2014, 327), that may have arisen because of trauma at delivery, although it more commonly occurs because the uterus does not contract down after delivery (Chamberlain Citation2006, 560). Puerperal pyrexia particularly vexed eighteenth- and nineteenth-century doctors in Britain and would undoubtedly have been a major problem in earlier periods. It would have started several days after birth and ended in a pelvic abscess, a septic thrombophlebitis which led to septicaemia, or peritonitis that arose when bacteria had travelled up the fallopian tube (Chamberlain Citation2006, 559). It is possible that the early third trimester deaths may be related to conditions such as placenta praevia, which causes a low implanted placenta to peel off as the lower portion of the womb is pulled up in later pregnancy, and can be accompanied by profuse bleeding (Chamberlain Citation2006, 561). It is perhaps significant that two of the three middle-aged women – F 1226 from Ardreigh, Co. Kildare, and SK 60B from Ballyhanna, Co. Donegal – had died during the early third trimester since modern studies tend to suggest that women over 35 years are more susceptible to pregnancy complications, including placenta praevia (Jolly et al. Citation2000, 2433). Unfortunately, it was not possible to examine the position of SK 60A from Ballyhanna, Co. Donegal, in utero but SK 60B was recorded as having a notably androgenous pelvis so, if she had gone into premature labour, the birthing process may not have been able to progress, with the obstructed labour resulting in the death of both the woman and her unborn baby (Murphy Citation2015, 109).

Circumstances of death

It was surprisingly difficult to interpret the circumstances of death in many of the cases, largely due to issues of poor preservation in addition to a lack of information from the archaeological record for the precise position of the infant remains in relation to those of the adult female. In the following sections an attempt is made to sub-divide the cases into those of individuals who had died when pregnant or possibly during childbirth (n = 19), during childbirth (n = 5) and shortly after birthing (n = 6).

Death when pregnancy or possibly during birthing

In the majority of cases (80.0%; 24/30) it is considered probable the woman had died when still pregnant or perhaps during childbirth. It should be noted, however, that in ten instances the only evidence that this was the case were excavation notes which indicated that fetal remains had been recovered from the abdominal region of an adult female. As Lynch (Citation2012, 50) notes in relation to SK 16 and SK 17 from Sawpit Lane, Tuam, Co. Galway, without in situ examination of the position of the infant, it is impossible to be certain that it had remained in utero as opposed to having been delivered and subsequently placed on the mother’s abdomen in the grave. The enlarged and unstable nature of a newly delivered abdominal area, however, makes it feasible that the baby would have been buried with its head on the mother’s chest meaning that the neonatal remains are unlikely to be fully concentrated in the abdomen. Furthermore, as discussed below, definite post-partum babies and young children appear to have been typically positioned in this manner with the head either on, or adjacent to, the adult chest (Murphy and Donnelly Citation2018, 132–136). Examination of the positions of the infants in the remaining cases is helpful for reconstructing the nature of their deaths and those of their mothers although potential movement of the fetus during decomposition processes needs to be considered.

The in utero baby is surrounded by fluid within the amniotic sac that provides a buoyant and stable environment in which it can develop (Coad and Dunstall Citation2011, 184–185). When a pregnant woman dies the infant body is surrounded by the decomposing tissues of the uterine environment. It is also positioned adjacent to the mother’s decomposing gastrointestinal tract, liver and other major abdominal organs. The non-vital womb is therefore a potentially unstable environment due to the build-up of gases and breakdown of soft tissues as part of decomposition processes (see Clark, Worrell, and Pless Citation1997, 155). These factors mean that a degree of caution needs to be exercised when attempting to interpret the position of a fetus in utero on the basis of archaeological skeletal remains. The larger and more mature the fetal skeleton is, however, the less likely it is to have been subject to substantial movement during decomposition.

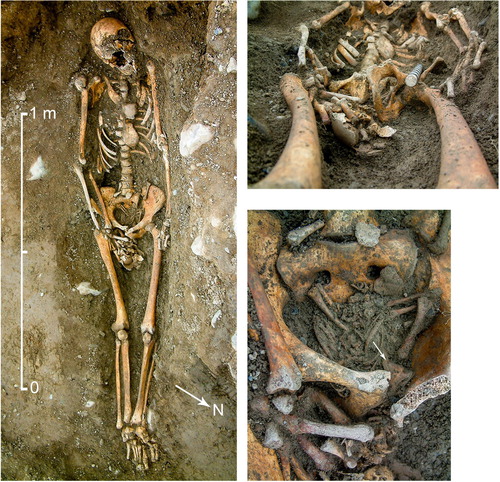

In some 88.9% (8/9) of the cases of pregnancy, where it was possible to examine the position of the infants in utero, they appear to have been in cephalic presentation in preparation for delivery. An infant of 38–41 weeks gestation (Skeleton CCLIII) from Mount Gamble, Co. Dublin, was exceptionally well preserved and it was possible to determine that it had been in cephalic position (right occiput transverse), in an oblique lie. The head was low in the mother’s pelvis and it is possible, but not certain, that the birthing process had commenced. No clear cause for the maternal and infant death was evident. Possible evidence of trauma or degenerative changes on the woman’s lumbar vertebrae may have impeded the delivery but this is by no means definite (Le Roy and Murphy Citation2020, 216–221; O’Donovan Citation2016, 29; O’Donovan and Geber Citation2010, 235) ().

Figure 3. An infant of 38–41 weeks gestation (Skeleton CCLIII) from Mount Gamble, Co. Dublin, lying in cephalic position with the right occiput transverse, in an oblique lie (photograph courtesy of Edmond O’Donovan).

An unborn preterm infant of 16 weeks gestation (F 5833) from Ardreigh, Co. Kildare, appears to have been lying in an oblique position in utero with the head positioned at the inferior aspect of the maternal sacrum and the legs overlying the right side of the third sacral vertebra (Troy Citation2010, 102). Given the very immature status of this individual, however, it is difficult to be certain this is a true representation of the position of the infant at death. An infant of 30–32 weeks gestation (SK 65b) from Portmuck, Co. Antrim, was only partially excavated due to the position of its mother’s grave (SK 65a) within an unexcavated section. The bones recovered were suggestive the baby had been positioned in a transverse lie in which the head lay to the right side of the mother’s pelvis and the right limbs were positioned inferiorly (Murphy Citation2006, 71).

It was difficult to interpret the position of C 943, an infant of 35–40 weeks, associated with C 827 a young adult female from Ballykilmore 6, Co. Westmeath, which was recovered in two discrete blocks. The first group comprised skeletal elements from the cranial vault, pelvis and lower limbs and was located within the maternal pelvic cavity. A partial articulated foetal skeleton, comprising the head and thorax, was subsequently discovered some 15 cm to the south and just below the level of the maternal pelvis. Osteological analysis indicated the two groups of remains definitely derived from a single infant. It was suggested the fetal remains may have been ‘flushed from the womb’ during decomposition but the body was deposited in an earthen environment and appears to have been covered with soil quite quickly which may have impeded this level of movement (see below). An animal burrow separated the two parts of the infant body and it is possible this may have been responsible for its disturbance (see Channing and Randolph-Quinney Citation2006, 124–126).

Death during birthing

In two of the cases of infants in cephalic position – SK 339 from Ballyhanna, Co. Donegal (39 weeks gestation) and SK 1699A from Faughart Lower 116, Co. Louth (28–36 weeks gestation) – the infant’s head was considered to have been positioned very low within the mother’s pelvic inlet which was interpreted as an indication of death during labour (Bowen and Dawkes Citation2011, 73; McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018, 68; Le Roy and Murphy Citation2020, 221–224). If this interpretation is correct then SK 1694A from Faughart Lower 116, Co. Louth, may have gone into premature labour. In the modern world pre-term birth is associated with 5–18% of pregnancies and can be caused by a multitude of factors – intra-amniotic infection; defective decidual haemostasis; premature decidual senescence; a breakdown of maternal-fetal tolerance; decline in progesterone levels, as well as maternal physical and mental stress – all of which produce a physiological response that can potentially trigger the onset of labour (Romero, Dey, and Fisher Citation2014).

The head of C 957, of 38–40 weeks gestation, from Ballykilmore 6, Co. Westmeath, was extruded through the mother’s (C 955) pelvic inlet (Channing Citation2009, 54) (). While there is a possibility this situation may have arisen as a consequence of decomposition processes it seems more feasible that death had occurred when the fetus had been partially delivered. Indeed, Sayer and Dickinson (Citation2013, 287) have convincingly argued how ‘coffin birth’ is likely to be a very rare archaeological phenomenon. They note how forensic cases of such deliveries are usually unrelated to decomposition processes but rather arise because of unusual circumstances in relation to the manner of the mother’s death. Furthermore, they observe how the soil infill of a typical medieval Christian burial would have prohibited the extrusion of a fetus; the implication being that potential coffin births can physically only occur within a burial environment that contains voids (see Duday Citation2009; Viva, Cantini, and Fabbri Citation2020). C 955 had been buried in an extended supine position within an earthen grave pit (Channing Citation2009, 55) and there is a possibility the body was shrouded which may have enabled the creation of a small void between the upper legs which could perhaps have facilitated a coffin birth. However, a possible explanation that might account for a partial delivery is evident; a photograph clearly shows that the fetal body remained within the mother’s pelvis and its left scapula appears to abut the posterior aspect of her left pubic bone. As such, it can tentatively be suggested that this was a case of shoulder dystocia in which one or both of the infant’s shoulders became stuck within the mother’s pelvis thereby preventing its birth. This form of obstructed delivery generally arises when there is a discrepancy between the size of the pelvic inlet and the foetal shoulders and it occurs with a frequency of 0.2–3% of modern births. It is particularly common in modern diabetic mothers who tend to have larger infants characterized by substantial shoulder and extremity circumferences, a low head-to-shoulder ratio, high percentages of body fat and thick upper extremity folds (Gherman et al. Citation2006, 658). No attempt appears to have been made to deliver the baby post-mortem and the pair appear to have been interred without further physical intervention. Indeed, a possible act of tenderness may be witnessed through the position of the bones of the mother’s right hand which appears to have been deliberately set resting on the baby’s head.

Figure 4. The head of C 957, of 38–40 weeks gestation, from Ballykilmore 6, Co. Westmeath, extruded through the mother’s (C 955) pelvic inlet. It seems feasible that death had occurred when the fetus had been partially delivered and that labour may have been obstructed due to shoulder dystocia (photographs courtesy of John Channing).

Two possible examples of unsuccessful births of babies in the breech position were also present. The potential difficulties of the vaginal birthing of a baby in this position are recognized in the modern world and a high proportion of such infants are birthed by means of elective caesarean sections (see e.g. Daskalakis et al. Citation2007). Vaginal birthing can result in obstructed labour and maternal death because of rupture of the uterus. It can also result in a prolonged labour which leaves the mother more susceptible to post-partum haemorrhage or sepsis (Hofmeyr Citation2004, 62). A modern study of 400 women in Greece, who had opted for planned vaginal birthings of breech infants, found that 17.1% ended in emergency caesareans; in just over half of the cases labour dystocia prevented vaginal birth (Daskalakis et al. Citation2007, 165). The abdomen and lower limbs of Skeleton CCCCVI, an infant of approximately 40 weeks gestation, recovered from the burial ground at Mount Offaly, Co. Dublin, lay inferior to the mother’s (Skeleton CCXVII) pelvis, while the thorax lay within the pelvic cavity and the head, although not visible in the photograph, had presumably been positioned in the vicinity of the mother’s lumbar vertebrae. The left pubic bone of the adult female overlay the lumbar vertebrae of the infant so it was clearly partly in utero (Conway Citation1999, 32). Skeleton CCXVII had been buried in an extended supine position within a grave pit but the remains were in a very poor state of preservation so it was impossible to ascertain if a shroud was present that might have facilitated a coffin birth. The amount of the baby presented, however, would make post-mortem birthing within the space afforded by a shroud seem improbable. C 447, an infant of 38–40 weeks gestation, from the Ballykilmore 6, Co. Westmeath, burial ground also appears to have been partly birthed at death (Channing Citation2009, 53). In this case, however, only the fetal head was positioned within the pelvic cavity and the post-cranial remains were described as being in a state of disarray below the maternal pelvis (C 443). The cranial remains were in a good state of preservation and appear to have neatly collapsed in upon one another which is suggestive of decomposition within the confines of the womb as opposed to ex utero. It was not possible to determine whether C 443 had been shrouded. As was the case for the other breech case, since so much of the infant’s body was presented, it seems unlikely that sufficient space would have existed within the confines of an extended supine shrouded body interred in an earthen grave to facilitate a coffin birth. Presumably in both cases the women had suffered from prolonged obstructed labours related to the breech positions of the babies and that they, and their infants, had both eventually died as a result of maternal exhaustion and haemorrhage.

Death post-partum

Six (20.0%) of the burials appear to have been those of a probable mother and newly birthed infant(s). A full-term infant was described as having been ‘laid out on the ribs and pelvis’ of an associated adult female (E520:B33) at St. Peter’s Churchyard, Waterford (Power Citation1997, 768). F 5633, an infant of 36–38 weeks gestation from Ardreigh, Co. Kildare, was buried in an extended supine position, with the head to the west, adjacent to the right humerus of F 1505 (Troy 2016, pers. comm.). An infant of around 40 weeks gestation from Mount Offaly, Co. Dublin, had been buried with the head lying on the left side of the chest of an adult female (contexts unknown) (Conway Citation1999, 32). Similarly, an infant of 38 weeks gestation (Burial 004) was buried lying with its head on the left side of the chest of an adult female (Burial 003) at Parknahown 5, Co. Laois (O’Neill Citation2009, 234). The careful positioning of the infants so they were orientated in the same manner as the associated adult is a feature of other double burials in medieval Ireland which contain combinations of only adults, children alone or adults with older children (Murphy and Donnelly Citation2018). It seems reasonable to interpret the burial of an adult female and new-born infant as those of a mother and her child who both died in the aftermath of the birthing process. It also needs to be born in mind, however, that definite examples of double burials containing the remains of an adult male and a new-born infant have also been discovered. The remains of an infant of 40 weeks gestation (SK 34), for example, were found associated with a middle-aged male (SK 33) at Stacumny, Co. Kildare. The baby was orientated in the same direction as the man and was lying with its head on the left side of the lower part of his chest. The male skeleton displayed pronounced bilateral compression and it is possible that he and the infant had been wrapped together inside a single shroud (Murphy Citation2016; ). A middle-aged male (SK 876) was buried with a neonatal infant of 43 gestational weeks (SK 877) at Ballyhanna, Co. Donegal. The infant’s head followed the same orientation to the west as that of the adult and lay on the man’s left shoulder (McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018, 66; Murphy and Donnelly Citation2018, 137). As such, in the absence of aDNA testing, the maternal relationship between adult females and new-born infants in double burial configurations cannot be considered definitive.

Figure 5. The remains of an infant of 40 weeks gestation (F 34) found associated with a middle-aged male (F 33) at Stacumny, Co. Kildare. The male skeleton displayed bilateral compression and it is possible that he and the infant had been wrapped together inside a single shroud (photograph courtesy of Eoin Halpin).

SK 978 from Ballyhanna, Co. Donegal, appears to have survived the birth of baby twins (SK 986 and SK 979), only for all three of them to have died, possibly soon after (Murphy Citation2015, 109–111; McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018, 66–67). SK 986 had an age-at-death of 36 weeks, while SK 979 was aged at 37 weeks and, in the modern world, they would be considered to have reached full term since the intrauterine environment is no longer considered sufficient to continue sustaining the growth of twins after 36–37 weeks (Piontelli Citation2002, 25). The size discrepancy between the infants is suggestive that SK 979 had been afforded an advantageous situation in the womb, in relation to the distribution of amniotic fluid or differences in blood flow, relative to the smaller SK 986 (Piontelli Citation2002, 43). SK 978 was a very petite young adult, with an estimated living stature of only 144.4 cm (4′9″), and it is possible that, in the absence of modern medical intervention, the birthing of twin babies was simply too much for her and they all died as a result of a difficult birth. Even in the modern world, twins form a high proportion of prenatal and perinatal deaths and both present in the favourable vertex position in only 40% of cases and even then there can be complications. Following the birth of the first twin the second twin has more room to move around and frequently changes position, making a vaginal birth impossible (Piontelli Citation2002, 22, 52). The babies were positioned to the left of the mother; the head of SK 986 rested on her upper abdomen, while the head of SK 979 was laid lower on her abdomen. The impact of decomposition on the infant bodies is difficult to assess but the size of the babies, which should have limited their movement, in addition to their near parallel, transverse position, seems more compatible with an ex utero position. SK 986 lay prone, however, which may seem incompatible with this interpretation although it is possible the infant body had rolled over during the decomposition of the adult. If we accept that the twins had died after birth then the mother’s arms appear to have been deliberately arranged so that she cradled both babies and her right hand was placed on top of SK 979. In the event that the babies were in utero, the mother’s right hand had deliberately been placed on top of her pregnant abdomen.

Skeleton XXXVIII, an infant of 30–31 weeks gestation, was recovered at Mount Gamble, Co. Dublin, lying in an extended supine position with the head to the east between the femora of adult female, Skeleton XL, who was very poorly preserved (O’Donovan Citation2016, 29–30; O’Donovan and Geber Citation2010, 235). She appeared to have been buried in an extended supine position with the head to the west in a simple earthen grave. The infant burial was interpreted as a possible coffin birth and this is perhaps feasible if the mother had been wrapped in a shroud (see discussion above in Sayer and Dickinson’s Citation2013 paper). The infant skeleton displayed notable bilateral compression and the left arm appeared tightly flexed at the elbow so that the hand was positioned towards its shoulder and it is possible it had been shrouded.Footnote2 As such, it may have been deliberately placed between the woman’s legs in a position that mimicked the normal birth position or, alternatively, was accidentally placed within the grave with the head to the east rather than the west.

Conclusions

It is a challenging task to gain a true understanding of the experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and the post-partum period for women in medieval Ireland. The historical sources provide some insights but there is a tendency to focus on the unusual or for the information to be potentially biased towards the upper classes in Early Modern British Colonial society. The archaeological data is also potentially problematic in that it is only possible to identify cases of maternal death that involved the simultaneous, or near simultaneous, death of a mother and her infant(s). The prevalence of 1.7% (29/1,759) for maternal deaths is notably low especially when considering that the corresponding rate for modern-day sub-Saharan Africa is 18.2% (WHO Citation2019, 35). It seems that many of the women and their babies who died soon after the birthing process remain invisible in the archaeological record and that new combined palaeodemographic and palaeopathological approaches are the only way that the true rates of maternal mortality will be ascertained (see McFadden and Oxenham Citation2019). The absence of adolescent maternal deaths is suggestive that girls did not marry until after the age of 17 years. As such, the suggestion from the historical sources of younger marriage at around 14 years seem unlikely (Ní Chonaill Citationforthcoming, 27) since one might imagine these younger adolescents would be more visible as maternal deaths in the archaeological record. The vast majority of maternal deaths had occurred in women of 18–35 years (87.5%; 21/24), with only three middle-aged women represented. Young adulthood would therefore seem to have been the peak time during which women bore children or at least experienced fatal pregnancies. Modern studies have indicated that women aged greater than 35 years are at increased risk of obstetric complications (Nove et al. Citation2014, 160); if this age cohort was bearing large numbers of babies one would expect their greater representation in the archaeological record of maternal deaths. This finding is suggestive that women may have been exerting a degree of control over their reproductive capabilities that reduced their ability to get pregnant on a regular basis until they reached menopause.

The majority of infants were full-term/neonatal at death (71.0%; 22/31), and the first (29–32 weeks) and final thirds (37–40 weeks) of the third trimester were the times of highest risk of maternal death. The peak in death during the third trimester, and in the days following delivery, is not unexpected and correlates with the situation for modern women (Ronsmans and Graham Citation2006, 1193; Say et al. Citation2014, 326). Preservation and recording issues hampered the deconstruction of the maternal death in a number of cases and are a reminder of the necessity of having a trained osteoarchaeologist working on burial excavations. Nevertheless, it was possible to sub-divide the cases into those of individuals who had probably died when (1) pregnant or possibly during childbirth, (2) during childbirth or (3) shortly after birthing. In the majority of cases of pregnancy, where the position of the baby was determinable (88.9%; 8/9) it was in a cephalic position ready to be born. Two breech presentations (Mount Offaly and Ballykilmore 6), that appear to have ended in obstructed labour, were also identified, while delivery of an infant in cephalic position from Ballykilmore 6, Co. Westmeath, may have been unsuccessful as a result of shoulder dystocia. It is clear the women of medieval Ireland would have suffered from a similar range of obstetric complications to those experienced by modern women that can now thankfully be resolved through medical intervention, including caesarean sections. The loss of these women and their babies, in many cases after a difficult labour with great suffering, would no doubt have been a sadly familiar tragedy for Irish medieval families and communities.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Professor Rebecca Gowland, Durham University, and Dr Siân Halcrow, University of Otago, for the invitation to participate in the Wenner-Gren Anthropological Association-funded Mother-Infant Nexus workshop held in summer 2017 at Durham University, where this research was first presented. I very much appreciate the help of John Channing, John Channing Archaeology; Dr Jonny Geber, University of Edinburgh; Edmond O’Donovan, Edmond O’Donovan & Associates; and Carmelita Troy, Rubicon Heritage Services Ltd., who generously answered my queries and/or permitted me to include their images within this paper. Thanks are also due to Eoin Halpin for granting me stewardship of the Stacumny archive. The Ranelagh Osteoarchaeology Project was funded by Transport Infrastructure Ireland and I am grateful to Martin Jones for permission to include information from Ranelagh in this paper before it has been made publicly available. My midwife friend, Claire Myers, kindly gave me her expert opinion on the physical relationship between SK 978 and infants SK 979 and SK 986 from Ballyhanna. I am also very grateful to Professor Marc Oxenham, Australia National University/University of Aberdeen and Dr Colm Donnelly, Queen’s University Belfast, for their very helpful comments on the text. Libby Mulqueeny, Queen’s University Belfast, kindly prepared the illustrations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eileen M. Murphy

Eileen Murphy is Professor of Archaeology in the School of Natural and Built Environment, Queen’s University Belfast. Her research focuses on human skeletal populations recovered from prehistoric Russia and all periods in Ireland. She is particularly interested in the use of approaches from bioarchaeology and funerary archaeology to help further understanding of the lives and experiences of people in the past. Her recent books include co-editorship of Children, Death and Burial: Archaeological Discourses (2017 with Mélie Le Roy), and Across the Generations: The Old and the Young in Past Societies (2018, with Grete Lillehammer). She is the founding editor of Childhood in the Past.

Notes

1 Quote – Poem IX, verse 7 – poem attributed to Gormlaith. The poem is included in a compilation of Irish Bardic Poetry dating from approximately the thirteenth to the mid-seventeenth centuries (Bergin Citation1970, 312).

2 The descriptive terminology of Sprague (Citation2005, 86–89) was followed in relation to flexion as follows – semi-flexed: the angle is between 0° and 90°; flexed: the angle is greater than 90°; tightly flexed: the angle approaches 180°.

References

- Bednarski, S., and A. Courtemanche. 2011. “‘Sadly and with a Bitter Heart’: What the Caesarean Section Meant in the Middle Ages.” Florilegium 28: 33–69.

- Bergin, O. 1970. Irish Bardic Poetry: Texts and Translations. Dundalk: Dundalgan Press (reprint).

- Bieler, L., ed. 1963. The Irish Penitentials (Scriptores Latini Hiberniae 5). Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Bowen, P., and G. Dawkes. 2011. E3801 Faughart Lower, Co. Louth: Final Excavation Report of Phase 2 Excavations, A1/N1 Newry-Dundalk Link Road, Area 15, Site 116 (Vol. I). Report prepared for the National Roads Authority/ Transport Infrastructure Ireland (Digital Repository of Ireland, The Discovery Programme, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.bg25mv84h).

- Brooks, S. T., and J. M. Suchey. 1990. “Skeletal Age Determination Based on the os pubis: A Comparison of the Acsádi-Nemeskéri and Suchey-Brooks Methods.” Human Evolution 5: 227–238.

- Brothwell, D. R. 1981. Digging up Bones. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Buckley, L. 2002. “Appendix 2: The Human Skeletal Remains,” pp. 71–82 in D. P. Hurl, “The Excavation of an Early Christian Cemetery at Solar, County Antrim, 1993.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 61: 37–82.

- Buckley, L., C. Ní Mhurchú, A. Matthews, V. Park, N. Carty, O. Rouard, L. Swift, and H. Foster. 2011. Skeletal Report, pp. 78–209 in Bowen, P. and Dawkes, G., E3801 Faughart Lower, Co. Louth: Final Excavation Report of Phase 2 Excavations, A1/N1 Newry-Dundalk Link Road, Area 15, Site 116 (Vol. 2). Report prepared for the National Roads Authority/Transport Infrastructure Ireland (Digital Repository of Ireland, The Discovery Programme, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.bn99pn52z).

- Callan, M. B. 2012. “Of Vanishing Fetuses and Maidens Made-again: Abortion, Restored Virginity, and Similar Scenarios in Medieval Irish Hagiography and Penitentials.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 21: 282–296.

- Chamberlain, G. 2006. “British Maternal Mortality in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 99: 559–563.

- Channing, J. 2009. E2798: Final Report of N6 Kilbeggan to Kinnegad Dual Carriageway: Archaeological Resolution – Ballykilmore 6, Ballykilmore Townland, Co. Westmeath (final report vol. 1). Report prepared for the National Roads Authority/ Transport Infrastructure Ireland (Digital Repository of Ireland, The Discovery Programme, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.v4065r193).

- Channing, J. 2014. “Ballykilmore, Co. Westmeath: Continuity of an Early Medieval Graveyard.” In The Church in Early Medieval Ireland in the Light of Recent Archaeological Excavations, edited by C. Corlett, and M. Potterton, 23–38. Dublin: Wordwell Ltd.

- Channing, J., and P. Randolph-Quinney. 2006. “Death, Decay and Reconstruction: the Archaeology of Ballykilmore Cemetery, County Westmeath.” In Settlement, Industry and Ritual (Archaeology and the National Roads Authority Monograph Series No. 3), edited by J. O’Sullivan, and M. Stanley, 115–128. Dublin: Wordwell Ltd.

- Clark, M. A., M. B. Worrell, and J. E. Pless. 1997. “Postmortem Changes in Soft Tissues.” In Forensic Taphonomy: The Postmortem Fate of Human Remains, edited by W. D. Haglund, and M. H. Dorg, 151–160. London: CRC Press.

- Coad, J., and M. Dunstall. 2011. Anatomy and Physiology for Midwives. 3rd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

- Conway, M. 1999. Director’s First Findings from Excavations in Cabinteely (Margaret Gowan & Co. Ltd Transactions Volume 1). Dublin: Margaret Gowan & Co. Ltd.

- Cosgrave, U. 2010. Stacumny House, Celbridge, Co Kildare. 97E0119 (Ext), Stacumny, Excavation Report. Unpublished report prepared for ADS Ltd.

- Coughlan, J. 2009. Appendix 16. Human Skeletal Report, pp. 295–331 in Muñiz Pérez, M., E2123: N6 Galway to East Ballinasloe. Final Report – Treanbaun, Co. Galway – Bronze Age Site and Early Medieval Burials and Enclosure. Report prepared for the National Roads Authority/ Transport Infrastructure Ireland (Digital Repository of Ireland, The Discovery Programme, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.9p29cr13n).

- Daskalakis, G., E. Anastasakis, N. Papantoniou, S. Mesogitis, N. Thomakos, and A. Antsaklis. 2007. “Cesarean vs. Vaginal Birth for Term Breech Presentation in 2 Different Study Periods.” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 96: 162–166.

- Delaney, F. 2012. “Archaeological Excavation Report. 10E0117 – Sawpit Lane, Tuam, Co. Galway. Early Medieval Graveyard and Enclosure.” Eachtra Journal 16, http://eachtra.ie/index.php/journal/issues/16/.

- Dowd, M. 2018. “Bewitched by an Elf Dart: Fairy Archaeology, Folk Magic and Traditional Medicine in Ireland.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 28: 451–473.

- Duday, H. 2009. The Archaeology of the Dead: Lectures in Archaeothanatology. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Essen-Möller, E. 1932. “A Rare Old Irish Medical Book.” Irish Journal of Medical Science 7: 312–314.

- Ferembach, D., I. Schwidetzky, and M. Stloukal. 1980. “Recommendations for Age and Sex Diagnoses of Skeletons.” Journal of Human Evolution 9: 517–549.

- Geber, J. 2005. “Osteological Report on the Human Skeletal Material from Mount Gamble, Townparks, Swords, Co. Dublin.” Unpublished report prepared for Margaret Gowen & Co. Ltd.

- Gherman, R. B., S. Chauhan, J. G. Ouzounian, H. Lerner, B. Bernard Gonik, and T. Murphy Goodwin. 2006. “Shoulder Dystocia: The Unpreventable Obstetric Emergency with Empiric Management Guidelines.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 195: 657–672.

- Gottlieb, B. 1993. The Family in the Western World from the Black Death to the Industrial Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gowland, R., and S. Halcrow, eds. 2020. The Mother-Infant Nexus in Anthropology: Small Beginnings, Significant Outcomes. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Halcrow, S. E., N. Tayles, and G. E. Elliott. 2018. “The Bioarchaeology of Fetuses.” In The Anthropology of the Fetus: Biology, Culture, and Society (Fertility, Reproduction and Sexuality 37), edited by S. Han, T. K. Betsinger, and A. B. Scott, 83–111. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Hofmeyr, G. J. 2004. “Obstructed Labor: Using Better Technologies to Reduce Mortality.” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 85 (Supplement 1): S62–S72.

- Hurl, D. P. 2002. “The Excavation of an Early Christian Cemetery at Solar, County Antrim, 1993.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 61: 37–82.

- Jolly, M., N. Sebire, J. Harris, S. Robinson, and L. Regan. 2000. “The Risks Associated with Pregnancy in Women Aged 35 Years or Older.” Human Reproduction 15: 2433–2437.

- Joyce, P. W. 1903. A Social History of Ancient Ireland. Vol. 1, 2nd ed. Belfast: The Gresham Publishing Co. Ltd.

- Keating, D. 2009. An Analysis of the Human Skeletal Remains from Parknahown 5, Co. Laois (A015/060) (Vol 3). E2170: M7 Portlaoise-Castletown/M8 Portlaoise-Cullahill Motorway Scheme – Report on the Archaeological Excavation of Parknahown 5, Co. Laois. Report prepared for the National Roads Authority/ Transport Infrastructure Ireland (Digital Repository of Ireland, The Discovery Programme, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.cn700j93q).

- Kelly, F. 1995. A Guide to Early Irish Law (Early Irish Law Series Volume 3). Dublin: School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Kelly, F., ed. 2014. Marriage Disputes: A Fragmentary Old Irish Law-Text (Early Irish Law Series Volume 6). Dublin: School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Lawrence, A. 1988. “The Cradle to the Grave: English Observations of Irish Social Customs in the Seventeenth Century.” The Seventeenth Century 3: 63–84.

- Lehane, J., M. Muñiz Pérez, J. O’Sullivan, and B. Wilkins. 2010. “Three Cemetery-Settlement Excavations in County Galway at Carrowkeel, Treanbaun and Owenbristy.” In Death and Burial in Early Medieval Ireland in the Light of Recent Archaeological Excavations (Research Papers in Irish Archaeology 2), edited by C. Corlett, and M. Potterton, 139–156. Dublin: Wordwell.

- Le Roy, M., and E. Murphy. 2020. “Archaeothanatology as a Tool for Interpreting Death During Pregnancy: A Proposed Methodology Using Examples from Medieval Ireland.” In The Mother-Infant Nexus in Anthropology: Small Beginnings, Significant Outcomes, edited by R. Gowland, and S. Halcrow, 211–234. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Lovejoy, C. O., R. S. Meindl, T. R. Pryzbeck, and R. P. Mensforth. 1985. “Chronological Metamorphosis of the Auricular Surface of the Ilium: A New Method for the Determination of Adult Skeletal Age at Death.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 68: 15–28.

- Lynch, L. G. 2012. “Appendix 1: Osteoarchaeological Report.” pp. 32–75 in F. Delaney, “Archaeological Excavation Report. 10E0117 – Sawpit Lane, Tuam, Co. Galway. Early medieval graveyard and enclosure.” Eachtra Journal 16 (http://eachtra.ie/index.php/journal/issues/16/).

- Malcolm, E. 2005. “Medicine.” In Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia, edited by S. Duffy, 323–325. London: Routledge.

- McFadden, C., and M. F. Oxenham. 2019. “The Paleodemographic Measure of Maternal Mortality and a Multifaceted Approach to Maternal Health.” Current Anthropology 60: 141–146.

- McFadden, C., B. Van Tiel, and M. F. Oxenham. 2020. “A Stabilized Maternal Mortality Rate Estimator for Biased Skeletal Samples.” Anthropological Science 123: 113–117.

- McKenzie, C. J., and E. M. Murphy. 2018. Life and Death in Medieval Gaelic Ireland: The Ballyhanna Skeletons. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Mitchell, P. D., and M. Brickley, eds. 2017. Updated Guidelines to the Standards for Recording Human Remains (Chartered Institute for Archaeologists/ British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology). Reading: CIfA and BABAO.

- Moloney, C., L. Baker, J. Millar, and D. Shiels. 2012. Guide to the Excavations at Ardreigh, County Kildare. Dublin: Rubicon Heritage and Kildare County Council.

- Muñiz Pérez, M. 2009. E2123: N6 Galway to East Ballinasloe. Final Report – Treanbaun, Co. Galway – Bronze Age Site and Early Medieval Burials and Enclosure. Report prepared for the National Roads Authority/ Transport Infrastructure Ireland (Digital Repository of Ireland, The Discovery Programme, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.9p29cr13n).

- Murphy-Lawless, J. 1991. “Images of ‘Poor’ Women in the Writing of Irish men Midwives.” In Women in Early Modern Ireland, edited by M. MacCurtain, and M. O’Dowd, 291–303. Dublin: Wolfhound Press.

- Murphy, E. M. 2004. “Osteological and Palaeopathological Analysis of Human Remains Recovered from Tonybaun, Co. Mayo.” Unpublished report prepared for Mayo County Council.

- Murphy, E. M. 2006. “Osteoarchaeological and Palaeopathological Report on the Human Remains from Portmuck, Co. Antrim.” Unpublished report prepared for the Environment and Heritage Service DOE: NI.

- Murphy, E. M. 2015. “Lives Cut Short – Insights from the Osteological and Palaeopathological Analysis of the Ballyhanna Juveniles.” In The Science of a Lost Medieval Gaelic Graveyard – The Ballyhanna Research Project (TII Heritage 2), edited by C. J. McKenzie, E. M. Murphy, and C. J. Donnelly, 103–120. Dublin: Transport Infrastructure Ireland.

- Murphy, E. M. 2016. “Preliminary Analysis of Human Remains from Stacumny, Co. Kildare.” Unpublished report, Queen’s University Belfast.

- Murphy, E., and C. Donnelly. 2018. “Together in Death: Demography and Funerary Practices in Contemporary Multiple Interments in Irish Medieval Burial Grounds.” In Across the Generations: The Old and the Young in Past Societies (AmS-Skrifter 26; SSCIP Monograph 8), edited by G. Lillehammer, and E. Murphy, 119–142. Stavanger: University of Stavanger. https://doi.org/10.31265/ams-skrifter.v0i26.214.

- Murphy, E., J. Loyer, and D. Drain. 2020. Osteoarchaeological Analysis of the Human Remains from Ranelagh, Co. Roscommon (Licence No. 15E0136). Report prepared for Transport Infrastructure Ireland and Roscommon County Council.

- Ní Chonaill, B. forthcoming. “Child-centred law in Medieval Ireland.” In The Empty Throne: Childhood and the Crisis of Modernity, edited by R. Davis, and T. Dunne. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/3812/.

- Nic Suibhne, F. 1992. “‘On the Straw’ and Other Aspects of Pregnancy and Childbirth from the Oral Tradition of Women in Ulster.” Ulster Folklife 38: 1–13.

- Nove, A., Z. Matthews, S. Neal, and A. Virginia Camacho. 2014. “Maternal Mortality in Adolescents Compared with Women of Other Ages: Evidence from 144 Countries.” The Lancet Global Health 2: e155–e164.

- O’Connor, A. 2017. “‘Women’s Folklore’: Traditions of Childbirth in Ireland.” Bealoideas: The Journal of the Folklore of Ireland Society 85: 264–268.

- O’Donovan, E. 2016. “Archaeological Excavations on Mount Gamble Hill: Evidence for a New Early Medieval Church in Swords?” In Medieval Dublin 15, edited by S. Duffy, 13–38. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- O’Donovan, E., and J. Geber. 2010. “Excavations on Mount Gamble Hill, Swords, Co. Dublin.” In Death and Burial in Early Medieval Ireland in the Light of Recent Archaeological Excavations, edited by C. Corlett, and M. Potterton, 227–238. Dublin: Wordwell Ltd.

- O’Neill, J. 1905. “Cath Boinde.” Eriu 2: 173–185.

- O’Neill, T. 2007. “The Hidden Past of Parknahown, Co. Laois.” In New Routes to the Past (Archaeology and the National Roads Authority Monograph Series No. 4), edited by J. O’Sullivan, and M. Stanley, 133–140. Dublin: National Roads Authority.

- O’Neill, T. 2009. E2170: M7 Portlaoise-Castletown/M8 Portlaoise-Cullahill Motorway Scheme – Report on the Archaeological Excavation of Parknahown 5, Co. Laois (Vol 1: Text). Report prepared for the National Roads Authority/ Transport Infrastructure Ireland (Digital Repository of Ireland, The Discovery Programme, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.d21844297).

- O’Sullivan, A., F. McCormick, T. R. Kerr, and L. Harney. 2014. Early Medieval Ireland AD 400–1100: The Evidence from Archaeological Excavations. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy.

- Phenice, T. W. 1969. “A Newly Developed Visual Method of Sexing the os Pubis.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 30: 297–301.

- Piontelli, A. 2002. Twins: From Fetus to Child. London: Routledge.

- Power, C. 1995. “A Medieval Demographic Sample.” In Excavations at the Dominican Priory St Mary’s of the Isle, Cork, edited by M. F. Hurley, and C. M. Sheehan, 66–83. Cork: Cork Corporation.

- Power, C. 1997. “Human Skeletal Remains.” In Late Viking Age and Medieval Waterford, edited by M. F. Hurley, O. M. B. Scully, and S. W. J. McCutcheon, 762–817. Waterford: Waterford Corporation.

- Roberts, C., and M. Cox. 2003. Health and Disease in Britain: From Prehistory to the Present Day. Stroud: Sutton Publishing.

- Romero, R., S. K. Dey, and S. J. Fisher. 2014. “Pretem Labor: One Syndrome, Many Causes.” Science 345 (6198): 760–765.

- Ronsmans, C., and W. J. Graham. 2006. “Maternal Mortality: Who, When, Where, and Why.” The Lancet 368: 1189–1200.

- Say, L., D. Chou, A. Gemmill, Ö Tunçalp, A.-B. Moller, J. Daniels, A. Metin Gülmezoglu, M. Temmerman, and L. Alkema. 2014. “Global Causes of Maternal Death: A WHO Systematic Analysis.” The Lancet Global Health 2: e323–e333.

- Sayer, D., and S. D. Dickinson. 2013. “Reconsidering Obstetric Death and Female Fertility in Anglo-Saxon England.” World Archaeology 45: 285–297.

- Scheuer, L. S., and S. Black. 2000. Developmental Juvenile Osteology. London: Academic Press.

- Scheuer, J. L., J. H. Musgrave, and S. P. Evans. 1980. “The Estimation of Late Fetal and Perinatal Age from Limb Bone Length by Linear and Logarithmic Regression.” Annals of Human Biology 7: 257–265.

- Scott, M., ed. 1986. An Irish Herbal. The Botanalogia Universalis Hibernica. Wellingborough: The Aquarian Press.

- Sprague, R. 2005. Burial Terminology: A Guide for Researchers. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

- Stokes, W., ed. 1895. “The Prose Tales in the Rennes Dindshenchas.” Revue Celtique 16: 31–83.

- Tait, C. 2003. “Safely Delivered: Childbirth, Wet-nursing, Gossip-Feasts and Churching in Ireland c.1530–1690.” Irish Economic and Social History 30: 1–23.

- Troy, C. 2010. Final Report on the Human Remains from Ardreigh, Co. Kildare (Volume 1: Report). Unpublished report prepared for Headland Archaeology Ltd.

- Viva, S., F. Cantini, and P. F. Fabbri. 2020. “Post Mortem Fetal Extrusion: Analysis of a Coffin Birth Case from an Early Medieval Cemetery Along the Via Francigena in Tuscany (Italy).” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 32: 102419.

- Wellcome, H. S. 1909. Medicine in Antient Erin: An Historical Sketch from Celtic to Mediaeval Times. London: Burroughs Wellcome & Co.

- Wolveridge, J. 1670. Speculum Matricis Hybernicum, or, The Irish Midwives Handmaid Catechistically Composed by James Wolveridge, M. D.; With a Copious Alphabetical Index. London: Rowland Reynolds.

- World Health Organisation. 2019. Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva: World Health Organisation.