ABSTRACT

Representations of motherhood are rare on Athenian painted pottery from the fifth century BC. This lack of representation is surprising given producing and caring for children was one of a woman’s key duties in ancient Athenian society, and other evidence demonstrates the close bonds women had with their children, especially infants who were all the more in need of care and attention. In this article we explore the entangled lives of mothers and the youngest children – infants – in fifth century Athens to understand reasons for this under-representation. Images of childcare in iconography are surveyed to determine how women and infants are characterised in both private and public spheres. The devaluation, demonisation and appropriation of mothering within the context of fifth century Athenian society is then discussed to understand the impact of the institutional apparatus of motherhood on the experience of mothering.

The god made the nursing of young children instinctive for women and gave her this task, and he allotted more affection for infants to her than to a man.

(Xenophon On Household Management 7.24)

Introduction

So proclaimed Xenophon of Athens, in his guide to household management, written in the fourth century BC. To the mind of Xenophon, and no doubt many of his peers, the primary role of citizen wives, divinely ordained, was the bearing and rearing of children. Legitimate heirs were essential for the perpetuation of the household and reproduction of the citizen body, so marriage and motherhood assumed a central importance in the lives of women (Pomeroy Citation1994, 60–2). Yet archaeological evidence of motherhood is often intangible. Iconography produced in fifth century BC Athens frequently depicts women, but it rarely illustrates mothers, leaving us to question: why was motherhood so under-represented, especially on painted pottery? It is an absence which is generally overlooked or unaccounted for in scholarship (for example see Beard Citation1991, 24; Keuls Citation1993, 110; Shapiro Citation2003, 104; Harlow Citation2010; Hackworth Petersen and Salzman-Mitchell Citation2012, 5). The lack of maternal imagery on pottery is particularly noteworthy given the interconnected nature of mother-infant identities as explored in current work on linked and entangled life courses (Gowland Citation2015, Citation2018). Our focus here is upon the rare occasions in which women are represented as mothers of infants. Xenophon’s rhetoric demonstrates that the special bond between mothers and younger children was recognised, so it is pertinent to question why it was not celebrated on Athenian painted pottery, given iconography characterises a society’s norms and demonstrates its ideals. In this article we outline the significance of the few scenes that do portray motherhood,Footnote1 and explore why accessing the experience of motherhood is so problematic, before investigating why mothering may have been marginalised in fifth century BC Athenian society.

Pregnancy, Childbirth and Breastfeeding

In becoming pregnant and ultimately a mother, a woman acquires a new embodied identity (Gowland Citation2018, 108). During pregnancy the life courses of mother and child are completely intertwined, and ‘the developing foetus becomes embodied through the performativity of the mother’ (Gowland Citation2018, 110; see too Bigwood Citation1991, 68). The entanglement is both biological and social. In ancient Athens, women’s experiences of pregnancy were apparently overwritten by masculine ideologies related to the perpetuation of the citizen body. Perikles’ 451 BC citizenship lawFootnote2 epitomised this, linking politics and motherhood, by decreeing that mothers, as well as fathers, had to be Athenian citizens for children to warrant citizenship. There are no representations of pregnancy on painted pottery, perhaps because this embodied experience was alien – and possibly threatening (Lee Citation2012, 24) – to the (male) artists that produced the images. Furthermore, the pregnant body went against Athenian society’s ideals of the desirable female body (Pepe Citation2018, 151). For men, pregnancy was insignificant in comparison to its hoped-for end result: the production of a new citizen.

Likewise, childbirth – except of divinities and immortals – is not depicted on Athenian pottery. Mortal birth is only depicted in funerary and votive contexts (Stewart and Gray Citation2000; Catoni Citation2005; Burnett Grossman Citation2007, 312; Beaumont Citation2012, 46). Birth is similarly neglected in the ancient texts (Bremmer Citation2020, 44). This no doubt related to the fact that birth belonged primarily to the private realm of women (Bremmer Citation2020, 44), as well as the pollution associated with non-divine childbirth (Parker Citation1983, 50; Reeder Citation1995, 337–8; Osborne Citation2011, 160; Bremmer Citation2020, 47).

Breastfeeding, similarly, is rarely depicted in Greek art, though representations were more common in the Greek cities of Sicily and southern Italy, and in Etruria (Bonfante Citation1997, 177–9; Laskaris Citation2008; Bosnakis Citation2013).Footnote3 The act of breastfeeding maintains the close bodily relationship between mother and child (Bigwood Citation1991, 69; Irigaray Citation1991, 38–9; Salzman-Mitchell Citation2012, 141, 145), as shown on a unique red-figure loutrophoros fragmentFootnote4 found in the Sanctuary of the Nymphe (bride) in Athens. The loutrophoros is a nuptial vessel; the fragment is remarkable for characterising the woman as both bride and mother, blurring the lines between the erotic and the maternal (Salzman-Mitchell Citation2012, 142, 145). A second example appears on a hydriaFootnote5 (water pot) illustrating a mythological episode in which Eriphyle suckles her infant son Alkmaion; the scene foreshadows Eriphyle’s later death at the hands of her son (Sutton Citation2004, 345). There is a stark contrast between Eriphyle’s nurturing of her son in the scene, and his subsequent matricide in the mythological narrative; the matricidal son affirms the patriarchal order (Irigaray Citation1991, 36). Some scholars (for example Beaumont Citation2012; Reboreda Morillo Citation2018) have suggested the breastfeeding motif was taboo in Athenian contexts, because the exposure of a breast rendered images sexualised and therefore inappropriate to be associated with respectable women in public contexts (Marshall Citation2017, 187). Exposed breasts may have communicated alternative messages, including to characterise weakness and vulnerability and to foreshadow peril (Bonfante Citation1997, 175), or to signify the animalistic practices of barbarians (Bonfante Citation1997, 185, 188). It may have been tied to fears of the female body because of its associations with ritual pollution, which were less apparent in Etruscan and post-Classical society (Laskaris Citation2008, 459).

It has been argued that the mothering of infants – particularly the act of breastfeeding – is rarely depicted on painted pottery, though it was common in literature from the time of Homer, because it was often the task of wet nurses, rather than mothers (Bonfante Citation1997, 184; Laskaris Citation2008, 461; Dasen Citation2011, 307–10; Beaumont Citation2012, 56–7; Räuchle Citation2017, 71–5; Marshall Citation2017, 188; Moraw Citation2021, 147). This presupposes that painted pottery was predominantly the preserve of families that had the resources to hire wet nurses, thus posing questions about the statuses of the women depicted (see Williams Citation1993). It also raises interesting questions about how motherhood was differentially experienced across the socio-economic spectrum in ancient Greece. We know from literature that even the most elite mothers could breastfeed their children: women use exposed breasts and reference to breastfeeding their children to make all the more emotional appeals in drama, possibly thereby being characterised as manipulative characters with a dangerous ability to nourish children, which men lacked (Marshall Citation2017). The lack of iconographic representation of breastfeeding perhaps relates instead to fears about the female body and taboos surrounding women’s nudity and breast milk (Bonfante Citation1997, 188; Laskaris Citation2008, 462). Viktoria Räuchle (Citation2017, 127) argues breastfeeding is linked to the physical, ‘animal’ elements of motherhood, which are overlooked when the experience of motherhood is obscured by social ideologies. Accordingly, the continued under-representation of the mother–child bond could relate to (male) anxieties about the otherness and dangers of women and the power they could derive from their reproductive and nourishing capabilities (Salzman-Mitchell Citation2012, 142).

Childcare on Painted Pottery

Mothers’ nurturing and socialisation of very young children is occasionally represented on red-figure pottery, illustrating acknowledgement of the particular interconnectivity of the life courses of mothers and infants.Footnote6 Here we focus on images that demonstrate close physical contact between a mothering figure and an infant which, we argue, highlight the intimacy and emotion that can be characteristic of the mother–child bond cross-culturally.

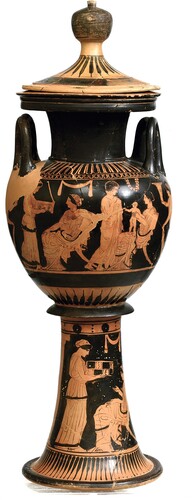

Bride

Scenes of marriage sometimes demonstrate recognition of a woman’s vital role to provide a legitimate heir, particularly those which combine the bride and mother in a single image. The schema, which occurs on pots used in weddings, portrays the seated bride, surrounded by attributes of the wedding, holding a baby boyFootnote7 as in (Kauffmann-Samaras Citation1987). The breastfeeding bride on the loutrophoros fragmentFootnote8 discussed above, belongs to this group. This conflation of the bride and mother expresses the wish for a fruitful marriage and reflects the bride’s transition to wife (Sabetai Citation1993, 49ff.; Waite Citation2016, 42; Sabetai Citation2019, 35ff.). Although the bride is represented in the domestic sphere, marriage and the production of a male heir became a public concern because they perpetuated the city–state as well as each household. The importance of the household and the family unit is demonstrated by one of these nuptial potsFootnote9 where a youth – presumably the groom stands () – before the bride (Sutton Citation2004, 338).

Lone ‘Mothers’

Scenes showing lone ‘mothers’ are some of the most touching in the iconographic record of childcare. They illustrate lone women, who are in most cases presumably mothers,Footnote10 cradling their infant children, on occasion conceptualised in the act of helping them to take part in some activity: one ‘mother’Footnote11 helps her child to pick grapes from a vine. A standing woman, surrounded by signifiers of her domestic domain, awkwardly clasps the arm of a young boy on a lekythos (oil flask) in Oxford (),Footnote12 whilst a woman on a lekythos in AmsterdamFootnote13 holds an infant out in front of her, as if for inspection. The awkward poses of some of these infants perhaps results from the fact they are positioned to emphasise their genitals, to demonstrate the mother has dutifully provided a male heir to perpetuate her husband’s bloodline (Keuls Citation1993, 110; Lewis Citation2002, 17). This emphasis undoubtedly highlights the desire for perpetuation of the family; the production of a male heir was after all the wife’s crucial role within the household (Beard Citation1991, 24; Fantham et al. Citation1994, 104).Footnote14 The child on the Amsterdam lekythos holds out their hands towards their caregiver in supplication. A stool places the scene in the domestic environment. A seated woman holds a young, naked child similarly on a fragment in Athens,Footnote15 though it is difficult to understand the narrative of the wider scene given the state of preservation. Another fragmentFootnote16 shows a woman holding an infant close within the folds of her cloak. This scene, more than most, characterises the intimacy of the mother–child bond. A lone ‘mother’ occasionally takes care of multiple children: on an alabastronFootnote17 (perfume vessel) an infant sleeps on her shoulder and an older boy stands clutching her dress; on a lekythosFootnote18 she watches on, apparently gesturing in encouragement, to an older girl and an infant, who rides on the girl’s shoulders. The domestic setting of all the scenes is affirmed by attributes including chairs, stools, wool baskets, and hanging hair nets and mirrors. The scenes clearly affirm that the place for mothering, especially of the youngest juveniles (of both sexes), was in the household, screened from public view. This could suggest one of the reasons why mothering was so infrequently illustrated: because it was not a public concern.

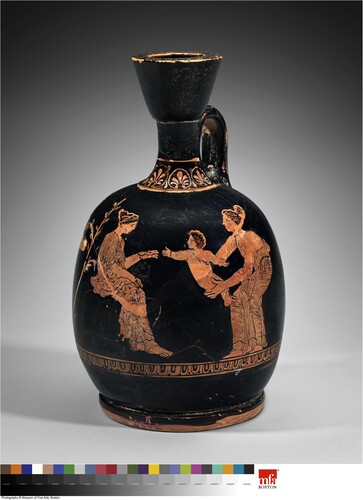

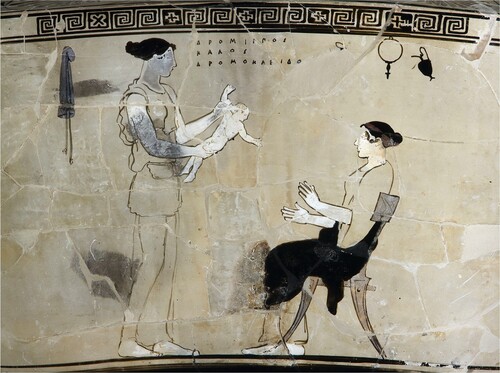

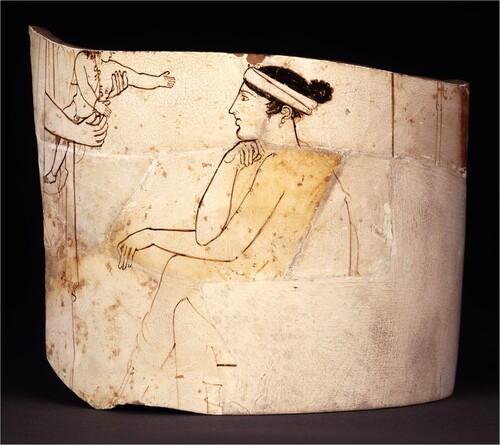

Mistress-Maid Passing

In scenes showing multiple women engaging in childcare identifying mothers is more problematic. A common motif demonstrating the ambiguity is one showing a standing woman – notionally a ‘maid’ or nurse, as sometimes indicated by her diminished stature, shorter hair and/or long-sleeved tunic (Massar Citation1995, 34–5) – passing an infant to, or receiving an infant from, a seated woman – typically identified as a mistress and thereby citizen mother. It is paralleled on grave stelai (gravestones) (Foley Citation2003, 133).Footnote19 On pots, at least, the scenes are typically placed in the domestic arena, emphasised by household attributes. On a hydria,Footnote20 a man watches a seated woman – presumably his wife – hand an infant to an attendant (Neils and Oakley Citation2003, 230; Sutton Citation2004, 340–1). An infant is passed over a wool basket on another hydria,Footnote21 juxtaposing the two predominant tasks of the dutiful citizen wife, as a producer of children and of household textiles (Bundrick Citation2008, 320). An infant on a lekythosFootnote22 is marked out as special by the elaborately-rendered string of protective amulets around his torso, and his mother – like the mother on the British Museum hydria – is notably enthusiastic in her gestures as she receives him into her arms. The mothers on three other lekythoiFootnote23 are remarkably less so, possibly in one case, discussed below, because the woman is deceased and therefore tragically unable to engage with the infant held out to her (,Footnote24 see also ). The ‘mother’ on a white-ground oinochoeFootnote25 (jug) is much more engaged with the child, gesturing with a toy towards the infant held by a ‘nurse’, whilst holding a mirror in her other hand. A stool places the scene in a domestic context, though the style and preservation of the vase hints at its suitability for a funerary context. The scenes demonstrate that the perspective afforded by painted pottery iconography is possibly on a relatively affluent motherhood, in which women could call upon the assistance of hired nurses or maids. This may have produced a notional disassociation between some mothers and ‘hands on’ mothering, which could contribute to the scarcity with which the practice was celebrated on painted pottery (see Moraw Citation2021).

Mothering in Groups

On occasion, iconography demonstrates that the mothering role could be shared by multiple women within the household; we can imagine it a multi-generational undertaking, though the ages of women are not rendered distinct in scenes on pottery. The well-known gravestone of Ampharete,Footnote26 showing a grandmother and her infant grandchild, demonstrates mothering was not only the preserve of mothers. Maria Sommer and Dion Sommer (Citation2015) have previously discussed how children could be ‘allo-parented’ in ancient Greece. Scenes that illustrate mothering in female groups are often a roll call of the key activities of the idealised, respectable Greek woman and wife, almost akin to an iconographic version of Xenophon’s manual about household management and women’s domestic roles. A hydriaFootnote27 shows one woman holding an infant, whilst two other women – not discernibly of different status – inspect jewellery in a casket and work with cloth. A sash and alabastron hanging in the field, and a stool indicate the domestic setting of the scene. On a fragmentary plateFootnote28 women make wreaths whilst caring for a child, again probably within the house. On another hydriaFootnote29 women play musical instruments including a lyre and pipes, and read from a scroll, whilst one cares for a child: the emphasis on work is replaced by a focus on entertainment in the domestic arena. It is the scarcity of motherhood in scenes of domesticity like these that is most noteworthy because motherhood alongside wool working and household management were women’s primary activities. Yet only three scenes show groups of women caring for infants; marginally more scenes show somewhat older and more mobile children amongst female groups in similar scenes, but the total is still negligible compared to the total of contemporary scenes showing wool working and beautification or adornment (see Guiraud Citation1985; Moraw Citation2021).

Families

Men rarely appear in domestic scenes of mothers and children since the household was largely the domain of women. Where men are present, they often regard rather than participate, generally standing on the periphery of the scene with a citizen staff orienting them to the outside world (Sutton Citation1981, 221; Massar Citation1995, 34, 37), as on a hydria discussed above.Footnote30 The wreath above the seated woman in this scene confirms her identity as wife and mother; it appears too in marriage scenes, hanging above the bride ().Footnote31 Family scenes, involving both parents, are rare on Athenian pottery (Sutton Citation1981, 216ff., Citation2004). A handful of images, on pyxides (cosmetic pots) used by women, appear to show family groupings. The assumption made is that we see the citizen household and that this is confirmed by the presence of children (Sutton Citation2004). One of these imagesFootnote32 depicts a youthful husband holding out a sprig to his seated wife (); three other women appear, one holding a child, one spinning and one carrying refreshments – here we have what appears to be the ideal household in action (Sutton Citation1981, 222). AnotherFootnote33 represents a man, leaning on a staff, with a fruit or ball of wool. Here the theme of courtship (generally interpreted as the hiring of a prostitute or courtesan) is seemingly adapted to the household, as indicated by the addition of children. As Robert Sutton (Citation2004, 327ff.) points out, in these images the household is conceptualised as a locus of economic industry and procreation, ensuring its continuation. The mother is primarily conceptualised as a producer (Massar Citation1995, 36). This is also demonstrated by a third pyxis.Footnote34 Domestic activities, including a seated woman with a child on her knee, are combined with what appears to be a departure; a bearded man and a youth appear both holding a spear, the youth is dressed in travelling attire, his identity as husband or son unclear. This emphasis on women as producers can be seen in wedding and funerary scenes as well as in images of departure.

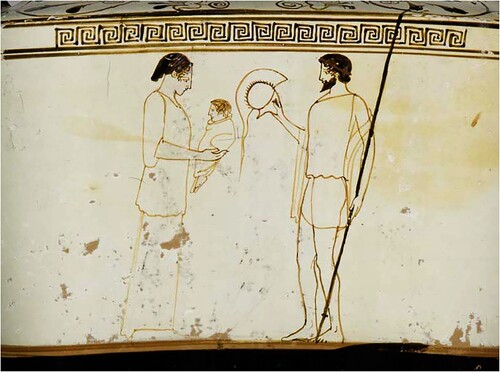

Warrior Departure

Warrior departure is a popular subject on pottery and in a handful of cases an infant appears in the scene (Porter Citation2019). By giving birth to a boy a woman fulfilled her role as a wife and mother, to produce future citizens. By arming and offering libations to the gods she prepared men for war. An amphoraFootnote35 (storage container) implicitly intertwines these roles. On one side a mother holds a naked infant, clearly identified as male, and on the reverse a bearded warrior stands, presumably ready for departure, with helmet, shield, and spear. Both the mother and child look towards the warrior as husband and father, but also as an embodiment of the future child. The rarity of these images has led some to conclude that they are mythological, in this case Hector and Andromache (Gardner Citation1888, 16), or in other scenes Amphiaraos and Eriphyle (Beazley Citation1928, 133). Amphiaraos is named on a hydriaFootnote36 which shows a departing warrior alongside a woman and child. On a cup,Footnote37 the chariot beside arming warriors, accompanied by a woman and child, similarly conjures the world of myth, referencing earlier black-figure scenes where the presence of women and children in images of departure places the emphasis firmly on the family and its continuity (Gooch Citation2021, 105–48). Myth and genre are conflated in these images.

On a white-ground lekythosFootnote38 a mother holds a swaddled infant beside a warrior holding a spear but with his helmet removed (). Here the warrior is departing not for war but from life to death and again the child represents the continuation of the family. The mother looks down towards her child, her gaze averted from her deceased husband, as she looks towards the future. Another white-ground lekythosFootnote39 places the departure beside a grave marker, the permanence of the parting poignantly signalled by the infant, clasped in its mother’s arms, reaching out to its father who places a hand on its arm. In these images of departure, the feminine and masculine realms of childbirth and warfare are contrasted (Lissarrague Citation1992, 181), a contrast which is continued in images of deceased mothers on grave markers, set in the public space of the cemetery, and on vases which locate the image beside the grave.

Mothering at the Grave

Images on white-ground funerary vases where a child reaches out for its mother clearly show the separation of the mother and child’s life courses. The gesture is echoed on grave stelai (Margariti Citation2016). Represented in the household – indicated by hanging mirror, jug, and hair net – a mother and baby reach out for one another for the last time underlining the poignancy of the fact that they cannot continue their lives together ().Footnote40 Although the funerary associations are not explicit in this case, other white-ground images are located beside the grave. In one image set at the grave side, the (male) infant fails to fully attract their mother’s attention; the mother already appears in another world, oblivious ().Footnote41 Here, the emphasis is on the child as an orphan (Margariti Citation2016). The child’s presence also underlines the maternal status of the mother, an identity which is represented far more in death than life. On grave stelai we can generally identify the deceased as a wife and mother who most likely died in childbirth or shortly afterwards; we therefore see a recognition of a mother’s death as a loss to both the family and city–state. A similar identification seems probable for the funerary vases just discussed.

Figure 6. Athenian white-ground lekythos, showing an infant being passed to a seated woman. Antikensammlung, Berlin F2443. © Antikensammlung, Berlin.

Figure 7. Athenian white-ground lekythos fragment, showing an infant reaching out to a woman seated on a grave marker. British Museum, London GR1905.7-10.10. © Trustees of the British Museum, London.

In other images on white-ground lekythoi the distinction between the deceased and living visitors to the grave side is harder to determine and the relationship between the figures is likewise not always clear (Waite Citation2000, 273–281; Gooch Citation2021, 313–343). A number of lekythoi show a woman, holding a child, beside a grave stele, on the other side of which there is a draped youth or man in all likelihood her husband.Footnote42 Where the figure is seated on the grave stele they are, in all probability, the deceased as confirmed by a white-ground lekythos in Zurich where a seated youth in travelling clothes shakes the hand of a woman (his wife) holding a child.Footnote43 This gesture of dexiosis (handshake between the living and the dead) is common on grave stelai (Davies Citation1985; Pemberton Citation1989). A woman holding a child sits on a stool beside the stele on another white ground lekythos,Footnote44 behind her a youth and woman are in conversation and before her a woman holds a funerary basket. Where figures hold offerings, they can be identified as visitors to the tomb, a role which was particularly associated with women. On a white-ground lekythos in AthensFootnote45 two women, one holding a child and vase, the other a funerary basket, visit the grave of another woman who sits on the stele ().

Figure 8. Athenian white-ground lekythos, showing a woman holding an infant beside at grave marker. National Archaeological Museum, Athens 25540 (Photo: Ilias Iliadis) © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D).

In sum, the evidence demonstrates the different contexts in which women are shown as mothers of young children, notably it is on funerary vases that the relationship received the most attention. An outline of all of the evidence demonstrates that depictions of women with young children were few and far between, and images of wool working and toilette far outnumber those showing women as mothers (Guiraud Citation1985). So, how do we account for the scarcity of images of child-rearing?

The Devaluation and Demonisation of Motherhood

François Lissarrague (Citation1992, 183) suggests that since mothering fell within the female domain it was of no interest to painters (see also Williams Citation1993, 97). Yet such a view is problematical when we consider their preoccupation with feminine images in general (Waite Citation2000). Furthermore, childbirth and child-rearing were central to the survival of the city–state, so attempts to devalue female roles in reproduction, and anxiety about those roles, surely contributed to the scarcity of images of childbirth and childrearing on painted pottery (Blundell Citation1995, 142). Such a devaluation was an inevitable consequence of the ethos of masculinity, which structured the Athenian democracy and demanded the superiority of the male (Keuls Citation1993). Scholars have suggested ‘uterus envy’ created a distaste for relying on women for their generative capabilities (Pepe Citation2012, 265). Women’s critical role in reproduction undermined the balance of power, upsetting the sexual asymmetry upon which the democracy was defined. Concerns about women’s power encroaching on that of men was present in Athens even before women’s importance increased as they became producers of citizens of the democracy. Pre-Classical laws imposed penalties on women who took steps to procure abortions without the permission of their husbands, thereby usurping men’s power. The right to sanction abortion, like the right to expose a new-born, was vested in the kyrios (male head of the household). Thus, laws sought to secure the rights of the father through control of the female body (Pepe Citation2012, 257, 260).

Attempts to Control Fertility

The tendency to devalue female roles in the perpetuation of the city–state represented a masculine attempt to procure some control over reproduction to offset male anxieties about legitimacy (Halperin Citation1990, 143–4). Attempts to control female fertility, and thereby women’s powers of reproduction, were evident in the promotion of early marriage and motherhood: marriage and subsequently pregnancy were recommended as the optimum remedies for treating various female ailments associated with a ‘wandering womb’, which could manifest from early maidenhood (Hippocrates Nature of Women 8.314–6; On Diseases of Women 2.126; King Citation1998, 36, 38). Rituals concerned with female fertility and reproduction such as the carefully controlled initiation rites at Brauron and the Thesmophoria were bound by city–state religion and thus also governed by civic (male) values (Demand Citation1994, 152–3). Male preoccupation with controlling women’s fertility reveals anxiety concerning female sexuality and woman’s lack of self-control, which could threaten the integrity, security, and reputation of the household and, later, the legitimacy of citizens (Demand Citation1994, 147).

Legitimacy Concerns and Links to Democracy

The wife’s ultimate duty of producing an heir for the oikos (household) clearly had political implications for the whole polis (city–state) since citizen status was dependent on legitimacy, especially in the aftermath of Perikles’ 451 BC citizenship law. With the law dictating that citizens could only be those individuals born of two citizen parents, motherhood became more politically valuable from the mid-fifth century (Molas Font Citation2018, 121); thus, the democratic system fuelled anxieties concerning female chastity. Adultery posed a serious threat to the integrity of the oikos and had both political and economic implications for the legitimate transfer of citizenship and property rights (Du Boulay Citation1974; Carson Citation1990, 158; Just Citation1991, 69; Demand Citation1994, 147ff.). The consequent preoccupation with legitimacy accounts for the legal distinction between rape and adultery, as explored by Lysias in the law court speech On the Murder of Eratosthenes (1.32–3):

Those who use force deserve a less penalty than those who use persuasion … considering that those who achieve their ends by force are hated by the persons forced; while those who used persuasion corrupted thereby their victims’ souls, thus making the wives of others more closely attached to themselves than to their husbands, and got the whole house into their hands, and caused uncertainty as to whose the children really were, the husbands’ or the adulterers’.

Dangerous Women

Physical reproduction was a female concern, but it was unquestionably something men were apprehensive about because women’s reproductive capabilities could give them power (Demand Citation1994, 68). These apprehensions manifested in extreme preoccupation with mortal women’s fidelity and cautionary tales about mythical women killing their children.

Monstrous Mothers

Fear of the power motherhood granted women, as well as concerns about their innate wildness, surely accounts for the demonised mothers of myth and tragedy, who commit monstrous crimes, not least killing their children (Warner Citation1994, 4, 7; McHardy Citation2005). Medea and Prokne murder their children to extract revenge on their husbands Jason and Tereus; Althaea kills Meleager after he kills her brothers; Ino throws Melicertes into the sea as they flee her husband Athamas, in a fit of madness imposed by Hera; Agave mistakenly dismembers Pentheus in a Dionysiac frenzy.Footnote46 Like genre scenes of day-to-day motherhood, these monstrous mothers are very rarely depicted on painted pottery, at least not in the act of mothering (neither murderous nor mundane). When the women are shown in iconography it is generally in scenes illustrating other elements of their stories; only Prokne – the Athenian mother (Ajootian Citation2005) – is shown in the act of infanticide.Footnote47 Medea flees justice having murdered her children, and her actions were considered especially barbaric because she did not face the consequences (Golden Citation2003, 24; Pepe Citation2012, 261–2). Her (murderous) association with her children is not illustrated on any extant Athenian vases, though an Apulian (south Italian) red-figure kraterFootnote48 (mixing vessel) shows Medea sacrificing a boy at an altar. Althaea and Ino are not shown with their ill-fated children in any known vase painting scenes. Agave’s unwitting murder of Pentheus, or at least allusions to the murder and its aftermath, was illustrated on vases, infrequently: two fragmentary cups record the mythical filicide.Footnote49 We can imagine this message, about how monstrous and dangerous women could be, being eagerly received in a patriarchal society that repeatedly sought to devalue and control the roles of women to generate reassurance about female inferiority.

Appropriation of Motherhood

Since the Athenian city–state was underpinned by the moral and legal authority of men, the father-right (Arthur Citation1987, 81–2), it is hardly surprising that women’s part in reproduction and childbirth was belittled or even denied. The playwright Euripides in both Medea (573–5) and Hippolytus (616ff.) gives voice to the male unease concerning women’s essential maternal role: Jason muses on the possibility of an alternative method for begetting children whilst Hippolytus posits the purchasing of children, thereby ensuring women’s redundancy. To establish the superiority of the father the mother’s role in reproduction was usurped – she is made responsible for incubation rather than generation. In Aeschylus’ Eumenides (658–61) the god Apollo decrees: ‘She who is called the child’s mother is not its begetter, but the nurse of the newly sown conception’. Hence the popular metaphor of the woman as a field passively awaiting the male seed (Vernant Citation1983, 139–40; Demand Citation1994, 135). As Patterson (Citation1986, 65) points out Apollo’s argument justifies a patriarchal social order on the basis of patrilineal biology.

Apollo’s words find a biological basis in Anaxagoras’ embryological theory whereby men alone contributed the seed of life, and women were passive receptacles of it: in such a reading ejaculation equals parturition (Rousselle Citation1988, 30; Leitao Citation2012, 19ff.). Aristotle likewise perpetuated the idea that conception and generation were the domain of men (Demand Citation1994; Pepe Citation2012, 269). Although this viewpoint is less common in the Hippocratic Corpus, Yurie Hong (Citation2012, 75, 83) argues that mothers are still biologically alienated from their children through the competition between foetus and mother established in the Corpus. Medical texts clearly reveal an ambivalence about pregnancy and childbirth and as Hong (Citation2012, 71) points out these biological processes are mapped onto cultural discourses underpinning the social institution of motherhood. Demand (Citation1994, 146) argues there are few cases of parturient mothers and/or infants in medical texts because such patients were typically cared for by networks of women rather than formal doctors, who subsequently penned the medical texts.

Motherless Divine Births

The diminishment of the female role in reproduction was matched by a devaluation of women’s part in childbirth. It is significant that childbirth is not depicted on Athenian painted pottery, with the exception of births of goddesses and gods (Beaumont Citation2012, 48; Lissarrague Citation1992, 182–3). Athena springs, in adult form, from the head of her father Zeus,Footnote50 in a succession myth which appropriated the creative principle for the male (Zeitlin Citation1995; Cid López Citation2009, 1; Leitao Citation2012, 72). A motherless, childless, and masculinised goddess who epitomised the father-right was an apposite symbol for the Athenian city–state (Aeschylus Oresteia 736–38). Likewise, Aphrodite is born from the severed genitals of Uranus and rises from the sea, fully grown, as depicted on a pyxis in Ancona.Footnote51 Beaumont (Citation1998, 80) links the lack of representations of infant goddesses to a conception of the female body as defined by sexual status, bestowed by maturity. Gods, on the other hand, are depicted as children. The infant Dionysus is born from ‘a secret womb’ in Zeus’s thigh where he was placed after the death of his mortal mother Semele.Footnote52 Although Leitao (Citation2012) downplays the gendered dynamics behind the trope of male pregnancy, he goes on to suggest that in myth ‘men can become pregnant as a means of depriving women of power’ (176); in this way men are given reproductive capabilities (Keuls Citation1993, 34; Pepe Citation2012, 265–6). Pot painters also represented Erichthonius’ ‘birth’ from the earth.Footnote53 Räuchle (Citation2015) argues Ge and Athena are characterised as mothers in these images, and that the female mothering role is thereby not undermined. However, the presence of Ge only recognises a female role that is physically marginalised: the lower part of her body is inevitably absent as she emerges from the ground. Myths of autochthony, which underpinned the city–state, were clearly based on a denial of the maternal role (Pomeroy Citation1998, 128).Footnote54

Pederasty: ‘Men Making Men’

The mythic appropriation of the female preserve of childbirth found a real counterpart in the very definition of masculinity. Essential to the concept of masculinity in some cultures is the belief that a man is not born but made (Gilmore Citation1990, 14), and the making of men is a strictly male affair. In ancient Athens the institution of pederasty served to initiate this male ‘re-birth’, raising the eromenos (younger beloved) to manhood through his educational relationship with the erastes (older lover) (Foucault Citation1992, 185ff.; Pepe Citation2012, 269; Golden Citation2015, 50; Bremmer Citation2021, 177ff.).Footnote55 As David Halperin (Citation1990, 143) summarises: ‘Pederasty represents the procreation of males by males: after boys have been born, physically, and reared by women, they must be born a second time, culturally, and introduced into the symbolic order of “masculinity” by men’. Such acculturation ensured, as Nancy Demand (Citation1994, 138) points out, that society’s dominant (male) values were passed from one generation to the next. These ideas are by no means restricted to fifth century Athens and ethnographic parallels offer confirmation of male attempts to appropriate birth. Whitehead (Citation1992, 82) draws attention to the role of man-boy homosexual relationships in New Guinea. Similarly, Bloch (Citation1982, 214–19) describes how the initiation ceremony of circumcision, enacted by the Merina of Madagascar, is represented as an alternative, cleansing, birth carried out solely by men. Again, in the ancient Greek context, as Demand (Citation1994, 139–40) comments (women) giving birth to infants could not compare with (men) ‘giving birth’ to ‘real men’: ‘By abrogating “true” or “higher” birthing to themselves, men devalued female birthing: women were considered capable only of giving birth to other females and to incomplete males whose masculinisation men must complete through a rebirthing process’. Women may have been necessary for the reproduction of Athenian citizens, essential for the relentless years of warfare, but the hoplite (heavily-armed soldier), the ultimate symbol of masculinity, was clearly the product of the city–state.

Conclusion

It is surprising that images of child-care are comparatively rare on Athenian painted pottery; although in reality children must have occupied a great deal of women’s time, women are infrequently portrayed in the role of mother. In some cases, gods were produced without the need for mothers and in the mortal world, ideas prevailed that men were made (by other men) rather than produced by women. In fact, women’s ability to produce children was considered threatening, and something that needed to be strictly managed, all the more so as democracy opened up the right to rule to more and more citizens from broader socio-economic groups with each successive generation. Until mortal men could give birth to children themselves, as their gods did, however, women’s roles in producing the next generation could not be entirely dismissed, though for reasons we have explored here, their identities as the ones who raised children were largely effaced.

Shapes and Viewing

Images that depict women in the household (typically images of wool work and beautification) unsurprisingly appear most often on pots used by women at home, such as perfume and cosmetics containers and vessels used in domestic tasks or for household storage. Other images of women appear on specialised shapes used in marriage and death rituals. Scenes showing mothering are likewise concentrated on vessel shapes used by women, especially white-ground lekythoi associated with funerary contexts and pyxides used to store women’s cosmetics and jewellery. This suggests the primary audience for the ideological messages communicated – about the ideals of mothering and motherhood – were women. How far women influenced their design, or how far they offered a construction of normative femininity from a male perspective, is debated (Sutton Citation1981; Waite Citation2000; Gooch Citation2021). Where shapes that would have been used in the symposium – a drinking party for men, which citizen women did not attend – are represented, they overwhelmingly depict warrior departure tableaux. When this is not the case, it is possible that the scenes are mythic, rather than genre scenes intended to represent ‘day-to-day life’. Images of mythic motherhood (including Perseus and Danaë) and motherless divine births also appear most often on shapes used in sympotic contexts, their primary audience therefore being men.

A Female Perspective?

Images which were apparently conceptualised with female viewers in mind exemplify the contrast between motherhood as an institution and the experience of mothering. On the one hand these are normative images, which define the ideal of the mothering role. On the other hand, we may wonder how far it was possible to escape the dominant male gaze and allow for a positive female viewing experience in which women could read their own experience of mothering.Footnote56 It is this experience of mothering that is so hard to glimpse in the archaeological record (Kopaka Citation2009, 184; Gowland Citation2018, 116). Susanne Moraw (Citation2021) argues that the absence of motherhood on vases demonstrated a preference for beautification on the part of the female audience in fifth and fourth century Athens, but this presumes that female demand dictated the typology of the iconography, which is by no means a secure assertion.Footnote57 Given pottery was made by male potters immersed in social norms and values that were constructed by men, and internalised by women, it is very difficult to access an authentic female perspective on what motherhood meant in ancient Athens (Huebner and Ratzan Citation2021, 12).

Motherhood as an Institution: Mothering as an Experience

The disconnect between motherhood as an institution and mothering as an experience, as expounded in Adrienne Rich’s seminal work Of Woman Born (Citation2021), means that investigating depictions of motherhood is not the same as exploring what it means to be a mother in a given context. The oppressive institutional apparatus of motherhood, as dictated by a patriarchal society, plays such a significant role in moulding what mothering is that it influences and obscures the potentially empowering experience of it (O’Reilly Citation2004, 2). This experience is historically contingent (LaChance Adams and Lundquist Citation2013, 8, 14). When we are trying to access that (private) experience element relative to past societies the influence of the institution is all the more problematic because of the limited nature of the evidence available for consideration. On Athenian painted pottery and grave stelai, we get glimpses of the (bodily) experience of mothering: the intimacy of the mother–child relationship is apparent in scenes showing direct physical and eye contact.Footnote58 The predominant perspective we are permitted is, however, the institutional one mediated by Athenian patriarchal society. Maternity is, and was in ancient Athens, both a social concept and a bodily experience (Hong Citation2012, 71; Sánchez Romero and Cid López Citation2018, 1, 7; Moraw Citation2021, 146). As Dolors Molas Font (Citation2018, 128, 130) argues, ‘the condition of motherhood, rather than a biological fate determining women’s being, is an ideological-cultural construct charged with political meanings’ and that resulted in attempts to control the female body, particularly its reproductive capabilities (Blundell Citation1995, 44). This manifested in phenomena like monstrous mothers and motherless births in myth and a general lack of iconography celebrating women in day-to-day mothering roles.

Marginalised Maternity in Classical Athens

Ultimately, it can be said that childcare was rarely depicted on, and so not really celebrated by, painted pottery because it was not an ideological concern of its producers and primary consumers. Many of women’s activities, as they are attested in the literary evidence, barely – if at all – warranted depiction on painted pottery, for example cleaning, cooking, and nursing the sick (Demand Citation1994, 22–3). Women were important as producers of children, and thereby perpetuators of society, but their bond with their children was essentially immaterial in the phallocentric democracy of ancient Athens. This is paralleled by laws demonstrating disinterest in women as mothers and the bonds between mothers and their children (Pepe Citation2018, 154). Almost all children shown with women are male, demonstrating they are characterised as symbols of a job well done, illustrating a public recognition of a new citizen, which relegates the sentimentality of the mother–child bond to subsidiary importance (Räuchle Citation2017, 81–2). Like the playfulness of children, for example, the mother-infant bond was more often sentimentalised in death, but in general daily life it was not a primary concern because it did not serve the (men of the) state beyond the extent to which the mere existence of children and women did. The disembodiment of death meant women – their sexuality, wildness, and reproductive power – were no longer a threat to the stability of patriarchal society. Most depictions of women with children – and the depictions that demonstrate the most direct interactions between women and children – from Classical Athens are funerary (Lewis Citation2002, 39, 82). Motherhood was celebrated publicly when it was ideologically expedient to do so (Hackworth Petersen and Salzman-Mitchell Citation2012, 2–3): patriarchal Athenian society placed the primary value on producing (male) children, not necessarily on raising them, and that marginalised the value that was consequently conferred on motherhood and the mothers whose identities it defined.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Andrew Parkin, Jacob Parkin, and Sadie Pickup, as well as our reviewers, for comments received on the text. All errors of course remain our own. Gratitude is also due to the National Archaeological Museum (Athens), the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford), the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston), the Antikensammlung (Berlin) and the British Museum (London), especially Maria Chidiroglou, Rosanna van den Bogaerde and Judy Barringer, for help with sourcing images for this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sally Waite

Dr Sally Waite is a Senior Lecturer in Greek Art and Archaeology at Newcastle University. She has worked extensively with the Shefton Collection of Greek and Etruscan Art and Archaeology in the Great North Museum, and is co-editor of On the Fascination of Objects: Greek and Etruscan Art in the Shefton Collection (2016). Her research focuses on the iconography on Athenian red-figure pottery, particularly in relation to questions of gender. She is co-editor of Shoes, Slippers and Sandals: Feet and Footwear in Classical Antiquity (2019) and is currently Principal Investigator on an AHRC-funded project ‘Shining a Light on Women and Children in Antiquity’.

Emma Gooch

Dr Emma Gooch holds a PhD in Archaeology from Newcastle University. She is currently an Associate Lecturer in Classics at the same university. Her research explores identity and relationships in ancient Greece, with a focus on children and women. She is also interested in material culture, iconography, the household archaeology of the ancient Mediterranean, and connections between humans and animals in antiquity. She is currently working on editing her doctoral thesis for publication as a monograph, Experiencing Childhood in Ancient Athens: Material Culture, Iconography, Burials and Social Identity in the Ninth to Fourth Centuries BCE.

Notes

1 In preparing this article, we compiled an original database of red-figure and white-ground pottery examples showing women with infant children; the discussion presented throughout this article is based on analyses of that database. The starting point for the database was Waite (Citation2000).

2 Aristotle The Athenian Constitution 26.3; Plutarch Lives Pericles 37.2–5.

3 See red-figure fragment in the British Museum (1847,0806.58) showing a wet nurse breastfeeding (https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1847-0806-58).

4 Acropolis Museum NA-57-Aa1872 (see Sabetai Citation2019, Figure 2.2).

5 Berlin, Antikensammlung F2395, BAPD 7011.

6 This is seen too in kourotrophoi (terracotta figurines of women and children) deposited on the Acropolis in Athens from the Archaic period onwards (Beaumont Citation2012, 66), as well as further afield (Burn Citation2000). More varied maternal dedications have also been found on the Acropolis (Avramidou Citation2015).

7 Athens, National Museum 1250, BAPD 216152; Munich, Antikensammlungen 7578, BAPD 214883; Athens, Kerameikos Museum 2694, BAPD 276110.

8 Athens, Acropolis Museum NA-57-Aa1872 (see Sabetai Citation2019, Figure 2.2).

9 Athens, National Museum 1250, BAPD 216152.

10 The identity of these women as mothers is debated, they could also represent other female relatives or nursemaids (Räuchle Citation2017, 79 ff.; Moraw Citation2021, 148 ff.). They are typically identified as mothers here because of iconographic indicators including mirrors, sakkoi (hair coverings), kalathoi (wool baskets) and perfume vessels, which typically denote not only a feminine environment but also the free status of the women associated with them (Waite Citation2000).

11 Chous (jug): Erlangen, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität I321, BAPD 10227.

12 Ashmolean Museum G298, BAPD 211374.

13 Allard Pierson Museum 15002, BAPD 9024837.

14 The social transition between bride and wife only took place upon the birth of a woman’s first son (Lewis Citation2002, 13–5, 39; Sutton Citation2004, 338; Gherchanoc and Bonnard Citation2013; Hong Citation2016).

15 Cup: Agora Museum P13363, BAPD 25331.

16 Cup: Athens, National Museum 2.446, BAPD 46622.

17 Rhode Island School of Design 25.088, BAPD 207244.

18 Athens, National Museum 12771, BAPD 209182.

19 Beaumont (Citation2012, 57) argues the nurse figures apparently serve to elevate the status of the mother.

20 Harvard, Arthur M. Sackler Museum 1960.342, BAPD 8184.

21 London, British Museum E219, BAPD 217063.

22 Athens, National Museum 1304, BAPD 9025010.

23 Boston, Museum of Art 95.50; London, British Museum 1905, 7-10.10, BAPD 216338; Berlin, Antikensammlung F2443, BAPD 213940.

24 Manner of: the Meidias Painter. Oil flask (lekythos) with women and children Greek, Classical Period, about 425 B.C. Place of Manufacture: Greece, Attica, Athens Ceramic, Red Figure. Overall: 13.4 × 8.3 cm (5 1/4 × 3 1/4 in.). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Catharine Page Perkins Fund 95.50.

25 Sold in New York, BAPD 31854.

26 Athens, Museum of the Kerameikos P695 / I221 (see Margariti Citation2016, Figure 7).

27 On the market, BAPD 20342.

28 Athens, Private Collection, BAPD 275628.

29 Plovdiv, Regional Museum of Archaeology IV.13, BAPD 9032479.

30 Harvard, Arthur M. Sackler Museum 1960.342, BAPD 8184.

31 Athens, National Museum 1250, BAPD 216152.

32 Athens, National Museum 1588, BAPD 214326.

33 Athens, National Museum 1623a, BAPD 275745.

34 Manchester, University III.I.2, BAPD 212513.

35 London, British Museum E282, BAPD 206109.

36 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 03.798, BAPD 214154.

37 Athens, National Museum (Acropolis Collection) 2.336, BAPD 201753.

38 Berlin, Antikensammlung F2444, BAPD 209215.

39 London, British Museum 1928,2-13.2, BAPD 215518.

40 Lekythos: Berlin, Antikensammlung F2443, BAPD 213940. See similar scenes on BAPD 19427; BAPD 209182. See also stele: Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden I 1.1903/2.1 (see Margariti Citation2016, Figure 11).

41 Lekythoi: London, British Museum GR1905,7-10.10, BAPD 216338; Havana, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes 202, BAPD 19472. See also stele: (of Phylonoe) Athens, National Museum 3790 (see Margariti Citation2016, Figure 1).

42 New York Market, BAPD 25910; Gotha, Schlossmuseum 57, BAPD 216743.

43 University L545, BAPD 216757 (Shapiro Citation1991, 654).

44 Los Angeles, County Museum A5933.50.24, BAPD 216747.

45 National Museum 25540, BAPD 216765.

46 Mormo was a quintessential monstrous mother; a mother who ate her own children and subsequently transformed into a demon that targeted other mothers and their infants at and around the time of birth (Foley Citation2003, 119). She is not characterised in vase iconography.

47 Red-figure cup fragment: H. Kahn Collection HC599, BAPD 12957. Cup tondo: Munich, Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek 2638 / 9191, BAPD 212468. Prokne is also shown with her son Itys and her sister Philomela on the tondo of another red-figure cup (Paris, Louvre G147, BAPD 204894); the scene presumably presages her killing Itys. There is a statue group of Prokne and Itys from the Athenian Acropolis (Athens, Acropolis Museum 1358, https://www.theacropolismuseum.gr/en/statue-prokne-and-itys). Barringer (Citation2005) argues that Prokne’s geneaology is of significance in such a context and sees the murder of Itys as symbolic of Prokne’s self-sacrifice and loss in response to her betrayal at the hands of a foreign husband – see too Räuchle (Citation2015).

48 Munich, Antikensammlungen 3296, BAPD 9036835.

49 Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum AP 2000.02, BAPD 11686; Rome, Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia 2268, BAPD 13059.

50 See for example: pelike: London, British Museum E410, BAPD 205560. See also: LIMC II (Athena 343-359); Arafat (Citation1990, 32ff., 187); Beaumont (Citation1998, 76).

51 Museo Archeologico Nazionale 3131, BAPD 211902. See also: Arafat (Citation1990, 30ff.); Beaumont (Citation1998, 77).

52 Krater fragment: Bonn, Akademisches Kunstmuseum 1216.19, BAPD 12464; lekythos: Boston, Museum of Fine Art 95.39, BAPD 206036. See Arafat (Citation1990, 39ff., 187); Beaumont (Citation1998, 72); Leitao (Citation2012, 58ff.).

53 See for example: Hydria: London, British Museum E182, BAPD 206695; stamnos (mixing jar): Munich, Antikensammlungen 2413, BAPD 205571; cup: Berlin, Antikensammlung F2537, BAPD 217211; calyx krater: Palermo, Museo Archeologico Regionale 2365, BAPD 217525. See Arafat (Citation1990, 51ff., 188); Beaumont (Citation1995, 344). For the myth of Erichthonius see Reeder (Citation1995, 250ff.).

54 Eradication of the woman’s reproductive role is also evident in mythology, in the birth of Helen of Sparta from an egg (see lekythos: Berlin, Pergamonmuseum F2430, BAPD 10222), and the creation of Pandora (see calyx krater: London, British Museum E467, BAPD 206955).

55 For the pederastic relationship as imaged on painted pottery see Dover (Citation1978) and Lear and Cantarella (Citation2010).

56 On the possibilities for a female gaze in antiquity, see: Hackworth Petersen (Citation1997) and Barrow (Citation2018).

57 On vase painting as a response to demand from female consumers, see: Sutton (Citation1981).

58 See Cohen (Citation2011, 473–5) on gestures as a means of communicating emotional bonds, including by kourotrophoi votives. These close bonds between mothers and children are also apparent in literature, for example in Euripides’ Ion and Trojan Women, and law court speeches demonstrate women were typically devoted to their children and invested in furthering their interests (Harlow Citation2010, 19). Plato (Laws VII.790c-d) remarks upon the importance of nursing and cradling infants.

References

Ancient Sources

- Aeschylus. Eumenides. Lloyd-Jones, H. (trans.) 1982. Aeschylus: Oresteia. London: Duckworth.

- Aristotle. The Athenian Constitution: Rackham, H. (trans.) 1935. Aristotle: Athenian Constitution, Eudemian Ethics, Virtues and Vices (Loeb Classical Library 285). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Euripides. Medea: Kovacs, D. (ed. and trans.) 1994. Euripides: Cyclops, Alcestis, Medea (Loeb Classical Library 12). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Euripides. Hippolytus: Kovacs, D. (ed. and trans.) 1995. Euripides: Children of Heracles, Hippolytus, Andromache, Hecuba (Loeb Classical Library 484). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Euripides. Trojan Women: Kovacs, D. (ed. and trans.) 1999. Euripides: Trojan Women, Iphigenia Among the Taurians, Ion (Loeb Classical Library 10). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Euripides. Ion: Kovacs, D. (ed. and trans.) 1999. Euripides: Trojan Women, Iphigenia Among the Taurians, Ion (Loeb Classical Library 10). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Hippocrates of Cos. Nature of Women: Potter, P. (ed. and trans.) 2012. Hippocrates, Volume X: Generation, Nature of the Child, Diseases 4, Nature of Women and Barrenness (Loeb Classical Library 520). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Hippocrates of Cos. On Diseases of Women: Potter, P. (ed. and trans.). 2018. Hippocrates, Volume XI: Diseases of Women 1–2 (Loeb Classical Library 538). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Lysias. On the Murder of Eratosthenes: Lamb, W. R. M. (trans.) 1930. Lysias (Loeb Classical Library 244). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Plato. Laws: Bury, R.G. (trans.) 1926. Plato: Laws, Volume II, Books 7–12 (Loeb Classical Library 192). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Plutarch. Lives Pericles: Perrin, B. (trans.) 1916. Plutarch: Lives, Volume III (Loeb Classical Library 65). Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Xenophon. On Household Management: M. R. Lefkowitz and M. B. Fant (trans.). 1992. Women’s Live in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook in Translation (second edition). London: Duckworth.

Sources

- Ajootian, A. 2005. “The Civic Art of Pity.” In Pity and Power in Ancient Athens, edited by R. Hall Sternberg, 223–252. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Arafat, K. W. 1990. Classical Zeus: A Study in Art and Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Arthur, M. 1987. “From Medusa to Cleopatra: Women in the Ancient World.” In Becoming Visible. Women in European History, edited by R. Bridenthal, C. Koonz, and S. Stuard, 78–105. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Avramidou, A. 2015. “Women Dedicators on the Athenian Acropolis and Their Role in Family Festivals: The Evidence for Maternal Votives Between 530–450 BCE.” Cahiers « Mondes Anciens » 6, doi:10.4000/mondesanciens.1365.

- Barringer, J. M. 2005. “Alkamenes’ Prokne and Itys in Context.” In Periklean Athens and Its Legacy: Problems and Perspectives, edited by J. M. Hurwit, J. M. Barringer, and J. J. Pollitt, 163–176. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Barrow, R. J. 2018. Gender, Identity and the Body in Greek and Roman Sculpture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beard, M. 1991. “Adopting an Approach II.” In Looking at Greek Vases, edited by T. Rasmussen, and N. Spivey, 12–37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beaumont, L. A. 1995. “Mythological Childhood: A Male Preserve? An Interpretation of Classical Athenian Iconography in its Socio-Historical Context.” Annual of the British School at Athens 90: 339–365.

- Beaumont, L. A. 1998. “Born Old or Never Young? Femininity, Childhood and the Goddesses of Ancient Greece.” In The Sacred and the Feminine in Ancient Greece, edited by S. Blundell, and M. Williamson, 71–95. London: Routledge.

- Beaumont, L. A. 2012. Childhood in Ancient Athens: Iconography and Social History. London: Routledge.

- Beazley, J. D. 1928. Greek Vases in Poland. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bigwood, C. 1991. “Renaturalizing the Body (With the Help of Merleau-Ponty).” Hypatia 6 (3): 54–73. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1991.tb00255.x.

- Bloch, M. 1982. “Death, Women and Power.” In Death and the Regeneration of Life, edited by M. Bloch, and J. Parry, 211–230. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blundell, S. 1995. Women in Ancient Greece. London: British Museum Press.

- Bonfante, L. 1997. “Nursing Mothers in Classical Art.” In Naked Truths: Sexuality and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology, edited by A. O. Koloski-Ostrow, and C. L. Lyons, 174–197. London: Routledge.

- Bosnakis, D. 2013. “L’allaitement maternel: une image exceptionnelle dans l’iconographie.” Les dossiers d’archéologie 356: 58–59.

- Bremmer, J. N. 2020. “Pregnancy and Birth in Ancient Greece: A Thick Description.” In Pregnancies, Childbirths, and Religions Rituals: Normative Perspectives, and Individual Appropriations. A Cross- Cultural and Interdisciplinary Perspective from Antiquity to the Present. Proceedings of the International Workshop., edited by G. Pedrucci and C. Bergmann, 39–54. Rome: Scienze e Lettere .

- Bremmer, J. N. 2021. Becoming a Man in Ancient Greece and Rome. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Bundrick, S. D. 2008. “The Fabric of the City: Imaging Textile Production in Classical Athens.” Hesperia 77 (2): 283–334. doi:10.2972/hesp.77.2.283.

- Burn, L. 2000. “Three Terracotta Kourotrophoi.” In Periplous: To Sir John Boardman from his Pupils and Friends, edited by G. R. Tsetskhladze, A. M. Snodgrass, and A. J. N. W. Prag, 41–49. London/New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Burnett Grossman, J. 2007. “Forever Young: An Investigation of Depictions of Children on Classical Attic Funerary Monuments.” In Constructions of Childhood in Ancient Greece and Italy. Hesperia Supplements 41, edited by A. Cohen, and J. B. Rutter, 309–322. Princeton: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

- Carson, A. 1990. “Putting Her in Her Place: Woman, Dirt and Desire.” In Before Sexuality: The Construction of Erotic Experience in the Ancient World, edited by D. M. Halperin, J. J. Winkler, and F. I. Zeitlin, 135–169. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Catoni, M. L. 2005. “Le regole del vivere, le regole del morire.” Revue archéologique 39: 27–53. doi:10.3917/arch.051.0027

- Cid López, R. M. 2009. Madres y maternidades: construcciones culturales en la civilización clásica. Colección Alternativas 32. Oviedo: KRK Ediciones.

- Cohen, A. 2011. “Picturing Greek Families.” In A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds, edited by B. Rawson, 465–487. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Dasen, V. 2011. “Childbirth and Infancy in Greek and Roman Antiquity.” In A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds, edited by B. Rawson, 291–314. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Davies, G. 1985. “The Significance of the Handshake Motif in Classical Funerary Art.” American Journal of Archaeology 89 (4): 627–640. doi:10.2307/504204.

- Demand, N. 1994. Birth, Death and Motherhood in Classical Greece. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Dover, K. J. 1978. Greek Homosexuality. London: Harvard University Press.

- Du Boulay, J. 1974. Portrait of a Greek Mountain Village. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Fantham, E., et al. 1994. Women in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Foley, H. 2003. “Mothers and Daughters.” In Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past, edited by J. Neils, and J. H. Oakley, 113–137. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

- Foucault, M. 1992. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Volume 2. Translated by R. Hurley. London: Penguin.

- Gardner, P. 1888. “Hector and Andromache on a Red-Figured Vase.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 25: 65–85. doi:10.2307/624209.

- Gherchanoc, F., and J.-B. Bonnard. 2013. “Mères et maternités en Grèce ancienne.” In Dossier: Mères et maternités en Grèce ancienne. Metis 11. L’Éditions de l’École des hautes études en sciences sociales, edited by F. Gherchanoc, and J.-B. Bonnard, 7–27. Athens/Paris: Daedalus.

- Gilmore, D. D. 1990. Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Golden, M. 2003. “Childhood in Ancient Greece.” In Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past, edited by J. Neils, and J. H. Oakley, 13–29. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

- Golden, M. 2015. Children and Childhood in Classical Athens. Revised ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Gooch, E. L. 2021. “The Material Culture and Extended Life Course of Children in Ancient Greece: An Inter-Disciplinary Exploration of Identity.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Newcastle University.

- Gowland, R. 2015. “Entangled Lives: Implications of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease Hypothesis for Bioarchaeology and the Life Course.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 158: 530–540. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22820.

- Gowland, R. 2018. “Infants and Mothers: Linked Lives and Embodied Life Courses.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Childhood, edited by S. Crawford, D. Hadley, and G. Shepherd, 104–122. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Guiraud, H. 1985. “La vie quotidienne des femmes à Athènes : à propos de vases attiques du Ve siècle.” Pallas 32: 41–57. doi:10.3406/palla.1985.1158.

- Hackworth Petersen, L. 1997. “Divided Consciousness and Female Companionship: Reconstructing Female Subjectivity on Greek Vases.” Arethusa 30 (1): 35–74. doi:10.1353/are.1997.0006.

- Hackworth Petersen, L., and P. Salzman-Mitchell. 2012. “Introduction: The Public and Private Faces of Mothering and Motherhood in Classical Antiquity.” In Mothering and Motherhood in Ancient Greece and Rome, edited by L. Hackworth-Petersen, and P. Salzman-Mitchell, 1–22. Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Halperin, D. M. 1990. One Hundred Years of Homosexuality and Other Essays on Greek Love. London: Routledge.

- Harlow, M. 2010. “Family Relationships.” In A Cultural History of Childhood and the Family, Volume I: In Antiquity, edited by M. Harlow, and R. Laurence, 13–29. Oxford: Berg.

- Hong, Y. 2012. “Collaboration and Conflict: Discourses of Maternity in Hippocratic Gynecology and Embryology.” In Mothering and Motherhood in Ancient Greece and Rome, edited by L. Hackworth-Petersen, and P. Salzman-Mitchell, 71–96. Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Hong, Y. 2016. “Mothering in Ancient Athens: Class, Identity, and Experience.” In Women in Antiquity. Real Women Across the Ancient World, edited by S. L. Budin, and J. Macintosh Turfa, 673–682. London/New York: Routledge.

- Huebner, S. R., and D. M. Ratzan, eds. 2021. Missing Mothers: Maternal Absence in Antiquity. Interdisciplinary Studies in Ancient Culture and Religion 22. Leuven: Peeters.

- Irigaray, L. 1991. The Irigaray Reader. Edited by M. Whitford. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Just, R. 1991. Women in Athenian Law and Life. London: Routledge.

- Kauffmann-Samaras, A. 1987. “Mère” et enfant sur les lébétès nuptiaux à figures rouges Attiques du Ve s.av.J.C.” In Ancient Greek and Related Pottery. Proceedings of the Third Symposium on Ancient Greek and Related Pottery in Copenhagen. , edited by J. Christiansen, and T. Mellander, 286–299. Copenhagen: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

- Keuls, E. 1993. The Reign of the Phallus. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- King, H. 1998. Hippocrates’ Woman: Reading the Female Body in Ancient Greece. New York: Routledge.

- Kopaka, K. 2009. “Mothers in Aegean Stratigraphies? The Dawn of Ever-Continuing Engendered Life Cycles.” In FYLO. Engendering Prehistoric ‘Stratigraphies’ in the Aegean and the Mediterranean, Aegaeum 30. Proceedings of the International Conference, University of Crete, Rethymno, 2–5 June 2005, edited by K. Kopaka, 183–196. Liège/Austin: Université of Liège and University of Texas.

- LaChance Adams, S., and C. Lundquist. 2013. “Introduction: The Philosophical Significance of Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Mothering.” In Coming to Life: Philosophies of Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Mothering, edited by S. LaChance Adams, and C. R. Lundquist, 1–28. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Laskaris, J. 2008. “Nursing Mothers in Greek and Roman Medicine.” American Journal of Archaeology 112 (3): 459–464. doi:10.3764/aja.112.3.459.

- Lear, A., and E. Cantarella. 2010. Images of Ancient Greek Pederasty: Boys Were Their Gods. London: Routledge.

- Lee, M. M. 2012. “Maternity and Miasma: Dress and the Transition from Parthenos to Gunē.” In Mothering and Motherhood in Ancient Greece and Rome, edited by L. Hackworth-Petersen, and P. Salzman-Mitchell, 23–42. Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Leitao, D. D. 2012. The Pregnant Male as Myth and Metaphor in Classical Greek Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lewis, S. 2002. The Athenian Woman: An Iconographic Handbook. London: Routledge.

- Lissarrague, F. 1992. “Figures of Women.” In A History of Women in the West, edited by P. Schmitt Pantel, 139–229. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Margariti, K. 2016. “A Mother’s Gaze: Death and Orphanhood on Classical Attic Grave Reliefs.” BABESCH 91: 87–104. doi:10.2143/BAB.91.0.3175645.

- Marshall, C. W. 2017. “Breastfeeding in Greek Literature and Thought.” Illinois Classical Studies 42 (1): 185–201. doi:10.5406/illiclasstud.42.1.0185.

- Massar, N. 1995. “Images de la Famille sur les Vases Attiques à Figures Rouges à l’Époque Classique (480–430 av. J.C.).” Annales d’Histoire de l’Art et d’Archéologie 17: 27–38.

- McHardy, F. 2005. “From Treacherous Wives to Murderous Mothers: Filicide in Tragic Fragments.” In Lost Dramas of Classical Athens, edited by F. McHardy, J. Robson, and D. Harvey, 129–150. Exeter: Exeter University Press.

- Molas Font, M. D. 2018. “Motherhood, Gender and Identity in the Athenian Polis.” In Motherhood and Infancies in the Mediterranean in Antiquity, edited by M. Sánchez Romero, and R. M. Cid López, 123–134. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Moraw, S. 2021. “Absent Mothers by Choice: Upper Class Women in Classical Attic Vase Painting.” In Missing Mothers: Maternal Absence in Antiquity. Interdisciplinary Studies in Ancient Culture and Religion 22, edited by S. R. Huebner, and D. M. Ratzan, 143–166. Leuven: Peeters.

- Neils, J., and J. H. Oakley, eds. 2003. Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

- O’Reilly, A., ed. 2004. From Motherhood to Mothering: The Legacy of Adrienne Rich’s ‘Of Woman Born’. Albany: University of New York Press.

- Osborne, R. 2011. The History Written on the Classical Greek Body. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Parker, R. 1983. Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Patterson, C. 1986. “Hai Attikai: The Other Athenians.” Helios 13 (2): 49–67.

- Pemberton, E. G. 1989. “The ‘Dexiosis’ on Attic Gravestones.” Mediterranean Archaeology 2: 45–50.

- Pepe, L. 2012. “Pregnancy and Childbirth, or the Right of the Father. Some Reflections About Motherhood and Fatherhood in Ancient Greece.” Rivista di diritto ellenico 2: 255–274.

- Pepe, L. 2018. “The (Ir)Relevance of Being a Mother. A Legal Perspective on the Relationship Between Mothers and Children in Ancient Greece.” In Motherhood and Infancies in the Mediterranean in Antiquity, edited by M. Sánchez Romero, and R. M. Cid López, 151–158. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Pomeroy, S. B. 1994. Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves. London: Pimlico.

- Pomeroy, S. B. 1998. Families in Classical and Hellenistic Greece. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Porter, N. 2019. “Images of Warrior Departure on Athenian Painted Pottery 600–400 BC.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Newcastle University.

- Räuchle, V. J. 2015. “The Myth of Mothers as Others: Motherhood and Autochthony on the Athenian Akropolis.” Cahiers Mondes Anciens 6, https://doi.org/10.4000/mondesanciens.1422.

- Räuchle, V. 2017. Die Mütter Athens und ihre Kinder: Verhaltens- und Gefühlsideale in Klassischer Zeit. Berlin: Reimer Dietrich.

- Reboreda Morillo, S. 2018. “Childhood and Motherhood in Ancient Greece: An Iconographic Look.” In Motherhood and Infancies in the Mediterranean in Antiquity, edited by M. Sánchez Romero, and R. M. Cid López, 135–150. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Reeder, E. D., ed. 1995. Pandora: Women in Classical Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rich, A. 2021. Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

- Rousselle, A. 1988. Porneia: On Desire and the Body in Antiquity. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Sabetai, V. 1993. “The Washing Painter: A Contribution to the Wedding and Genre Iconography.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Cincinnati.

- Sabetai, V. 2019. “The Transformation of the Bride in Attic Vase-Painting.” In The Ancient Art of Transformation: Case Studies from Mediterranean Contexts, edited by R. M. Gondek, and C. L. Sulosky Weaver, 33–51. Oxford/Philadelphia: Oxbow Books.

- Salzman-Mitchell, P. 2012. “Tenderness or Taboo: Images of Breast-Feeding in Greek and Latin Literature.” In Mothering and Motherhood in Ancient Greece and Rome, edited by L. Hackworth-Petersen, and P. Salzman-Mitchell, 141–164. Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Sánchez Romero, M., and R. M. Cid López. 2018. “Motherhood and Infancies: Archaeological and Historical Approaches.” In Motherhood and Infancies in the Mediterranean in Antiquity, edited by M. Sánchez Romero, and R. M. Cid López, 1–11. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Shapiro, H. A. 1991. “The Iconography of Mourning in Athenian Art.” American Journal of Archaeology 95 (4): 629–656. doi:10.2307/505896.

- Shapiro, H. A. 2003. “Fathers and Sons, Men and Boys.” In Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past, edited by J. Neils, and J. H. Oakley, 85–111. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

- Sommer, M., and D. Sommer. 2015. Care, Socialization and Play in Ancient Athens: A Developmental Childhood Archaeological Approach. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Stewart, A., and C. Gray. 2000. “Confronting the Other: Childbirth, Aging and Death on an Attic Tombstone at Harvard.” In Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, edited by B. Cohen, 248–274. Leiden: Brill.

- Sutton, R. F. 1981. “The Interaction Between Men and Women Portrayed on Attic Red-Figure Pottery.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Sutton, R. F. 2004. “Family Portraits and Recognizing the ‘Oikos’ on Attic Red-Figure Pottery.” Hesperia Supplement 33: 327–350.

- Vernant, J. P. 1983. Myth and Thought Among the Greeks. London: Routledge.

- Waite, S. 2000. “Representing Gender on Athenian Painted Pottery.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Newcastle University.

- Waite, S. 2016. “An Attic Red-Figure Kalathos in the Shefton Collection.” In On the Fascination of Objects: Greek and Etruscan Art in the Shefton Collection, edited by J. Boardman, A. Parkin, and S. Waite, 31–62. Oxford/Philadelphia: Oxbow Books.

- Warner, M. 1994. Managing Monsters: Six Myths of Our Time. London: Vintage.

- Whitehead, H. 1992. “The Bow and the Burden Strap: A New Look at Institutionalized Homosexuality in Native North America.” In Sexual Meanings: The Cultural Construction of Gender and Sexuality, edited by S. B. Ortner, and H. Whitehead, 80–115. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Williams, D. 1993. “Women on Athenian Vases: Problems of Interpretation.” In Images of Women in Antiquity, edited by A. Cameron, and A. Kuhrt, 92–106. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Zeitlin, F. I. 1995. “Signifying Difference: The Myth of Pandora.” In Women in Antiquity: New Assessments, edited by R. Hawley, and B. Levick, 59–74. London: Routledge.