ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to give an account of John Wallis’s analysis of sound symbolism in his English Grammar (1653), and to position this in the larger context of contemporary linguistic controversies concerning the search for a universal or philosophical language, as discussed both by other thinkers in the circle of the Royal Society and also by scholars on the continent of Europe. Although Wallis is usually taken to be a critical observer rather than an active participant in these debates, the paper will attempt to provide detailed evidence for his having been a previously unidentified source for the various alternative proposals for phonetic notation developed in John Wilkin’s philosophical language scheme (1688).

Introduction

John Wallis (1616–1703) is primarily known as a mathematician. At the start of the Civil War, he was appointed by the Parliamentarians to the Savilian chair of geometry at Oxford, after the previous occupant of the chair, a Royalist, had been ousted. However, Wallis wasn’t himself ousted in turn at the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, but continued successfully in his post, unlike many others in a similar position. It has to be said that Wallis was a clever political animal, and that he had many enemies who thought he was Machiavellian and untrustworthy. He was also very good at ‘networking’ with like-minded scholars, and he was one of the founding fellows on the Royal Society, which was formally inaugurated in 1661 under the patronage of Charles II.Footnote1

Wallis was a very active fellow of the Royal Society, and was fascinated by all aspects of the new sciences which were developing: mechanics, chemistry, theory of the tides and gravitation, and so on. He was what at the time was termed a ‘virtuoso’, someone interested in all things scientific and experimental – and it wasn’t just the scientific disciplines that interested him, but also the basic humanistic disciplines. He wrote tracts on logic, music and grammar, applying to these subjects the same rigour and method as he applied in his mathematical and experimental work. In this paper I will be examining how a figure with these interests and concerns understood the phenomenon of sound symbolism in language.

Wallis’s grammar: on ‘Soni rerum indices’

In his Grammatica Linguae Anglicanae (‘Grammar of the English Language’) published in 1653, he gave what has been termed the first systematic description of sound symbolism in any of the European vernaculars (Magnus Citation2013). The grammar was published in Latin, for the sake of foreigners who didn’t know the language but wanted to learn it. But what makes this grammar distinctive and ground-breaking, as Wallis himself claims, is that it is one of the first descriptions of English that does not simply force a vernacular language into the mould of Latin, but attempts to describe the patterns and structures of the English language in its own terms.Footnote2 As the Preface says:

I am well aware that others before me have made the attempt at one time or another, and have produced worthwhile contributions […] None of them, however, in my opinion, used the method which is best suited to the task. They all forced English too rigidly into the mould of Latin. For this reason I decided to employ a completely new method, which has its basis not, as is customary, in the structure of the Latin language but in the characteristic structure of our own.

When Wallis comes across what we now term phonæsthetic word structures in English, he gives a clear and systematic description of them. He first goes through the initial consonant clusters one-by-one, giving a brief indication of what the sounds convey, and an extensive list of words which have this as one element of their lexical meaning.

str-(stronger force) strong, strength, strike, strain …st-(less strong force) stand, stay, steady, sturdy, stiff …thr-(violent motion) throw, thrust, throb …wr-(distortion) wrest, wrestle, wring …sw-(silent or soft motion) sway, swim, swing …cl-(adherence) cleave, clasp, cling, clammy …sp-(scattering) spread, sprinkle, spill, spatter …sl-(silent motion, or softer sideways motion) slide, slip, slime, slow …sm-(silent motion) smooth, smug, smile, smirk, smart …

Thus for example the initial consonant cluster STR- carries the idea of ‘stronger force’, as in words such as strong, strength, strike, strain, etc. And SM- carries the idea of ‘silent motion’ as in smooth, smug, smile, smirk, and so on. He then does the same for word-final consonant clusters:

-ash(quick movement: clear) crash, rash, clash, slash …

-ush(quick movement: obscure) crush, rush, gush, slush …

-ingl(repeated action: smaller) jingle, tingle, twinkle …

-angl(repeated action: larger) jangle, tangle, mangle …

and for the vowels:

-a-clearness, liveliness, medium size

-i-acuteness, quickness, small size

-o-large size

-u-obscurity, silence

-oo-large quantity

After listing these sound-symbolic elements, Wallis shows how they work in a combinatorial fashion, which allows one to analyse whole words that are composed of more than one of them.

SMART

SM-silent motion

-AR-asperity of action

-Tsudden finish

SPARKLE

SP-scattering

-AR-acute crepitation

-K-sudden interruption

-Lfrequentative

Thus the English word SMART (in the sense of ‘a smart blow’) derives its meaning from an initial cluster SM-, indicating silent motion, a vowel -AR- indicating ‘asperity of action’, and a final voiceless dental – T, indicating sudden finish. A similar analysis reveals how the word SPARKLE derives its meaning in this way.

What Wallis does not include in his grammar, however, is any discussion of what he understands by this phenomenon, other than his insistence that the English language is particularly rich in it. In seventeenth-century terms, it is one of the excellencies of the language; one of the properties that characterise its particular genius. Wallis’s method is that of seventeenth-century empirical science, which is to allow the facts to speak for themselves. But it isn’t straightforward to spell out what Wallis thought the facts were saying, and there isn’t enough in the grammar itself to let us know.

What I shall attempt to do in this paper is to position Wallis’s account of sound symbolism in the larger context of various other contemporary linguistic debates in which Wallis was also deeply engaged. These include, most importantly, the search for a universal or philosophical language, which was the preoccupation of many of the leading scholars in the circle of the Royal Society. But this is not the only such area of debate: there are also theological issues which, for the seventeenth-century scholar, have a direct bearing on the matter, and other issues of a practical sort, such as the teaching of language to the deaf, and of a philosophical sort, concerning the relation of language and thought. My aim is not to address any of these various pieces of the background in great detail but simply to set the stage for understanding the view of sound symbolism held by Wallis.

There are two further points about Wallis’s treatment of sound symbolism which need noting before we proceed. Firstly, although Wallis’s Grammar of the English Language occupies a single volume, it consists of two quite distinct and separate tracts. There is the English Grammar itself, an analysis of the language described in its own terms; and prefixed to it, with a separate title page, is a tract entitled De loquela ‘On speech’, which is a treatment of articulatory phonetics in quite general terms. It is what Wallis describes as a ‘grammatico-physical’ tract. A discussion of sound symbolism could in principle have been included in either of these tracts. Other seventeenth-century thinkers made an explicit point of approaching sound-symbolism from a non-language specific perspective. His contemporary Marin Mersenne’s discussion is a good example of this (Mersenne Citation1636: vol II, 65, 75–77). Like Wallis, Mersenne goes through a number of word-initial phonæsthemes one by one, indicating what their significance is. However, he says that he doesn’t need to complete the inventory, since the meaning of these sound elements is self-evident; any reader, regardless of what language they speak, just needs to listen to the sound and they will already know what it means. For Mersenne, and other like-minded thinkers, the way one understands the meaning involved in this phenomenon is, by very definition, independent of the language one speaks. But that assumption is not Wallis’s starting point.Footnote3 His treatment of sound symbolism belongs not in the general phonetic tract de Loquela; it forms part of the grammar of the English language. What Wallis is describing are language-specific patterns. So that is the first essential point for understanding Wallis’s treatment.

The second point to note is that Wallis was intellectually preoccupied with the phenomenon of sound symbolism, almost to the point of obsession and throughout his working life. This can be demonstrated from the way the grammar is expanded from edition to edition, as has been analysed by Miyawaki (Citation2001; see further Cram & Miyawaki, Citationforthcoming). There were five editions during Wallis’s lifetime: the first appeared in 1653, the final one in Citation1699. Over these editions, the grammar more than doubled in size overall. But the expansion isn’t uniform through the work. In the first edition, the section in which sound symbolism is treated formed only 13% of the whole. By the Citation1699 edition it had swollen to form 31% of it. Furthermore, following the Citation1699 edition, Wallis continued to make annotations and additions to a copy of the work which he had deposited in the Savilian Library at Oxford (now in the Bodleian Library, Savile Gg 1–3).

As Wallis expanded this section obsessively from edition to edition, he was clearly searching for a principled account of the phenomenon. But he didn’t leave any explicit statement of what his position on this controversial matter was. We need to reconstruct it – as is our present purpose.

Jan Amos Comenius: Panglottia

As a first point for comparison, we turn to the treatment of sound symbolism in a quite different context: the universal language scheme in Jan Amos Comenius’s Panglottia.Footnote4 Comenius is a controversial figure in the history of universal language schemes in Britain, since there has been dispute about the degree to which figures like Dalgarno and Wilkins were indebted to him.Footnote5 Comenius’s first published call for a universal language appeared in 1668 under the title Via Lucis, ‘The Way of Light’, but the title page of this work announced that the tract had been written over 20 years earlier, on a brief visit to London in 1640 (Comenius Citation1668). It is possible, but not certain, that manuscript copies of the work circulated in England in the interim. By 1668 the schemes devised by Francis Lodwick and George Dalgarno had already appeared in print, and it is not clear whether the sketch of the scheme in Via Lucis was revised in light of them. Furthermore Comenius’s scheme was only properly fleshed out in a subsequent work, which remained unpublished until the manuscript came to light again in 1966.Footnote6

However, these historical details do not affect the relevance of Comenius to our present purpose, which is to use his scheme as an orientation point. It is an example of a philosophical or universal language based purely on sound symbolic principles, of the sort that I have alluded to in connection with Mersenne. The outline of such a scheme is elegantly simple: it consists of nothing more than an ‘alphabet’ of phonæsthetic elements, plus a very simple syntax, which basically allows one to combine anything with anything. The scheme doesn’t allow any irregularities, or synonyms or polysemy. It is indeed so simple that one can effectively summarise its principles on two sides of a single postcard.

Comenius starts with the phonetic building blocks of the language. Under the heading ‘On the special ability of letters to denote certain things’, each of the vowels are first assigned a phonæsthetic value: the letter ‘i’ being naturally suited to express something slender, sharp, and long, and so on.

i is naturally suited to express something slender, sharp, and long

ecould express something pointed or wedge-shaped

asuggests vast, wide, and open

osuggests round-shaped

u suggests thick and blunt, square, or parallel

Likewise the consonants, ‘s’ expressing something sharp, resounding or jingling, and so on.

S & Cexpress something sharp, resounding or jingling

K(the opposite of these) denotes blunt and dull things

Rwould apply to hard and rough things

Lis a liquid letter, suitable for expressing liquid and flowing things

T & Dwould indicate small or large obstacles

Mis a mute letter

(Comenius Citation1966; trans. Dobbie Citation1989, 80)

All this is reminiscent of what Mersenne and others had previously written (Pavlas Citation2017).

What makes the Comenius scheme look attractive is the association of this set of building blocks with a simple combinatory syntax. The language has no complicated nominal and verbal morphology; no distinct inflectional and derivational endings. What it has are little sets of prefixes and affixes that can combine with nouns or verbs equally well. Thus for example there is a set of prefixes (which he calls prepositions when he first introduces them), each symbolised by one of the vowels, as follows:Footnote7

adenotes privation

idenotes diminution

udenotes augmentation

edenotes partiality

odenotes universality

These will combine with a noun such as LUS meaning ‘light’ to signify elements in a field of semantically related concepts which in received languages are expressed by words or phrasal expressions that are not similar either phonologically or morphologically:

(noun)LATINENGLISH

lusluxlight

a-lustenebraedark

i-lusumbrashadow

u-lusnimius splendourbrilliance

e-lusaliquantum lucis dim light

o-lustotalux total brightness

In the philosophical language, the form of the word directly indicates both its own internal semantic structure, and also its relation to other words which belong in the same semantic field.

Furthermore, once one has this set of particles, one is not restricted to combine them only with Nouns, as just illustrated. They can equally well be combined with Verbs, with the same effect:

lalloquito speak

a-laltacereto be silent

i-lalsusurrareto whisper

u-lalclamareto shout

e-lalnarrareto tell/to narrate

o-lalomnia eloqui/garrire to be eloquent/to chatter

And it is not just Nouns and Verbs these prefixes will combine with, but also Adjectives and Adverbs, and in principle with any part of speech whatsoever.

The simplicity and mathematical power of combinatorial schemes such as this (and similar ones were devised by Francis Lodwick, Georg Harsdörffer and Athanasius Kircher) made them enormously appealing to the seventeenth-century mind.Footnote8 But the simplicity of these schemes was also their fatal flaw. They work very well for basic notions, but when extended to the full extent of a human language they became massively complicated and unwieldy. And they cannot handle most abstract concepts at all. As Wallis says he explained to George Dalgarno, when he started helping him with his universal language scheme in 1657: such schemes looked good in theory; they don’t work in practice (Wallis Citation1678).

We now have two useful triangulation points. Comenius’s scheme for a combinatorial language scheme based purely on universal sound symbolic elements, is thus a useful contrast with Wallis’s preoccupation with the language-specific patterns of sound symbolism in the English language. I now turn to a third kind of concern with sound symbolism in language, namely that of Jacob Böhme’s conception of the Language of Nature.

Jacob Böhme: the ‘language of nature’

The impact of Böhme in England should not be underestimated.Footnote9 Between 1647 and 1662 essentially the complete works of Jacob Böhme were published one-by-one in English translation, by John Elliston and John Sparrow, and in most cases these volumes appeared even before their first publication in German. But Böhme’s writings were taken up in several different ways by these English readers, for their own purposes. For Böhme himself, the language of nature was not a reconstructed language system, as many readers assumed, but rather a mystic way of reading both the book of nature and the book of revelation (Pektaş Citation2006, 151–157). For many of those wishing to construct a universal language, the task was seen as requiring the reconstruction of the primitive Adamic language, a reversal of the confusion of languages following the destruction of the tower of Babel. But Böhme’s thinking, which had its roots in Jewish cabbalistic tradition, derived not from the narrative of Babel but from that of the biblical account of creation in the very first verses of Genesis. According to the mystical cabbalistic tradition, creation happened when God first uttered the names of the letters, the letters being the primal elements of all things.Footnote10 The central doctrine of the signatures of things derives directly from this narrative of creation, for the names of the letters were literally written into the very essence of all things. The signatures of things can be read off by those in the appropriate state of mystic understanding. As Böhme says, in De signatura rerum (Citation1651: 4):

The greatest Understanding lieth in the Signature, wherein Man not only learns to know himself, but therein also he may learn to know the Essence of all Essences; for by the external form of all Creatures, by their instigation, inclination and desire, also by their sound, voyce and speech which they utter, the hidden Spirit is known.

And in another work, Mysterium Magnum, he says (Citation1654: 221):

[In the first age of mankind] men did understand the Language of nature, for all Languages did lye therein; but when this Tree of the one onely Tongue did divide it selfe in its properties and powers among the children of Nimrod, then the Language of nature (whence Adam gave names to all things, naming each from its property) did cease.

For Böhme, then, reading the Book of Nature does not mean learning a new language, but rather putting oneself back in Adam’s state of knowledge. And reading the Book of Revelation (the Bible) does not involve learning a new language either: it is a mystic way of reading, which can be done in whatever vernacular is closest to the reader.

There were any number of little groups of Böhme followers in England at this time,Footnote11 and some of Böhme’s readers would have understood his teachings, as they related to language, in a full-bloodedly mystic way. But there were also those who applied his ideas in a more literal-minded way, as they might apply to the project of constructing a philosophical language. One of the thinkers central to the latter group, whom we shall meet shortly in connection with John Wilkins, is Francis Mercurius van Helmont. Another is John Webster, to whom I now turn.

The Webster-Ward debate

The Webster-Ward debate is a small skirmish in a larger rethinking of the educational system at this time. In the 1650s there was a pamphlet war directed against the two English universities, attacking their curriculum on political and theological grounds. One central criticism raised in a pamphlet published by John Webster in 1654 was the failure of the universities to develop and teach a universal character (a written version of a philosophical language) based on the teachings of the mystic Jacob Böhme. ‘What a vast advancement had it been to the Republick of Learning’, he writes, ‘and hugely profitable to all mankind, if the discovery of the universal Character had been wisely and laboriously pursued and brought to perfection?’ And he then goes on to indicate, in his own florid style, that the kind of universal character he has in mind is one inspired by Böhme and the Rosicrucians:

I cannot (howsoever fabulous, impossible, or ridiculous it may be accounted of some) passe over with silence, or neglect that signal and wonderful secret (so often mentiond by the mysterious and divinely-inspired Teutonick [i.e. Böhme], and in some manner acknowledged and owned by the highly-illuminated fraternity of the Rosie Crosse) of the language of nature.

By a universal character Webster here must mean a scheme something like those being proposed by Mersenne, Comenius and others, even though he calls for it in the spirit of Böhme. That is certainly how the criticism was interpreted by his readers. A reply to his pamphlet was immediately written by Wallis’s colleague Seth Ward, and this appeared in the same year, with a preface penned by John Wilkins (Ward Citation1970). Ward replied point-by-point to all of Webster’s criticisms, including the question of language. Far from neglecting the project of a universal character, he says, there are in fact several persons at the university of Oxford who are quite far advanced in developing such a scheme. From the details Ward then gives, it is apparent that the scheme under development was not of the mystic kind that Webster had in mind, but one based on rational and mathematical principles, a Real Character. The point that Ward then goes on to make is a key one for our present purposes:

Such a Language as this (where every word were a definition and contain’d the nature of the thing) might not unjustly be termed a naturall Language, and would afford that which the Cabalists and Rosycrucians have vainely sought for in the Hebrew. (Ward Citation1654: 22)Footnote12

In distancing himself from Webster’s mystical approach to the idea of a universal character, Ward nevertheless insists that a Real Character based on rational principles, if correctly understood, will be seen to serve the same function as the universal character that Webster has in mind. And Ward uses the key term: the Real Character being developed by the university ‘might not unjustly be termed a natural language’. This point should be borne in mind, since we will meet a similar point of contact between the mystical and the rational approaches below.

Another figure now enters the scene. In a diary entry for 1657, Samuel Hartlib, the influential promoter of new scientific schemes, says that in Oxford, Dr Wallis and Dr Ward ‘are assisting a Scotchman to perfect his investigation of Real Characters’. The Scot in question was George Dalgarno.

George Dalgarno: on sematology

Dalgarno’s universal language scheme had appeared in Citation1661 under the title Ars Signorum, ‘The art of signs’ (reprinted in Cram & Maat Citation2001). He had at first collaborated with John Wilkins on the joint construction of a philosophical language, but after a difference of opinion as to the principles on which it should be based, he rushed into print with a scheme of his own. Sound symbolism does not play a major role in Dalgarno’s scheme at this stage, but in a subsequent work on teaching language to the deaf, Didascalocophus, or the Deaf and Dumb Man’s Tutor (Citation1680), he repositions his earlier work in a more elaborated framework of what, now writing in English, he calls ‘sematology’ (Citation1680: iii).

A running assumption made by Dalgarno, both here and in his unpublished papers, was that a philosophical language could be both ‘real’ and also ‘arbitrary’. In this he was outlining a view that Wallis arguably subscribed to but did not himself explicitly state. In schematic form, Dalgarno’s scheme can be represented as in .

Dalgarno’s overall term for his taxonomy of signs is Interpretation, a term which he borrows from the Aristotelian tract De Interpretatione. Sematology, which he defines as ‘a general name for all interpretation by arbitrary signs’, is one of three basic subcategories of this overall notion, and sits alongside Physiology, which concerns natural signs, when the internal passions are expressed ‘by such external Signs, as have a natural connexion by way of cause and effect with the passion they discover’, and Chrematology, which concerns supernatural signs, ‘when Almighty God reveals his will by extraordinary means, as dreams, visions, apparitions, etc’. Sematology, the study of arbitrary signs, further subdivides three-ways into: Pneumatology, interpretation by signs conveyed through the ear; Schematology, interpretation by figures conveyed to the eye; and Haptology, interpretation by signs conveyed through mutual contact, skin to skin. The further subdivisions need not concern us here.

This taxonomy of signs gives Dalgarno a means of introducing sound symbolism in a quite specific place. He positions it under Sematology, the interpretation of arbitrary signs, and he does so with a cross-reference to the discussion in Wallis’s grammar which was outlined above.

[A]ll languages, guided by the instinct of Nature, have more or less of Onomatopœia in them, and I think our English as much as any: For beside the naming the voices of Animals, and some other Musical Sounds, […] we extend it often to more obscure, and indistinct sounds. Take for example, wash, dash, plash, flash, clash, hash, lash, slash, trash, gash, &c. […] of which kind of words, The Learned and my worthy friend Dr Wallis has given a good account in his English Grammar.

Dalgarno here explicitly includes both onomatopoeia in the narrowest sense of imitations of physical sounds such as the voices of animals and also what we would nowadays call phonæsthemes, to use the term coined by J.R. Firth (Citation1930: chapter vi), e.g. dash, plash, flash, etc. These two rather different forms of sound symbolism are likewise treated together by Wallis, but without explicit comment.Footnote13 A second point about Dalgarno’s taxonomy of signs is that it establishes a parallelism between vocal signs and visual signs, of the sort used both in writing and in the language of the deaf, to which we will return.

John Wilkins: towards a phonetic real character

John Wilkins’s Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language (1668) is the most famous of all the seventeenth-century universal language schemes.Footnote14 It is an enormous volume of over 500 pages in folio, in comparison with Dalgarno’s slim volume in octavo. Wilkins thanks Wallis for advice on matters relating to phonetics, but it is striking that there is only cursory mention of sound symbolism in the volume, and this mention is a purely negative one. Wilkins says that he simply does not understand how a full language based on sound symbolism could be implemented.

It were exceeding desirable that the Names of things might consist of such Sounds, as should bear in them some Analogy to their Natures; and the Figure or Character of these Names should bear some proper resemblance to those Sounds, that men might easily guess at the sence or meaning of any name or word, upon the first hearing or sight of it. But how this can be done in all the particular species of things, I understand not; and therefore shall take it for granted, that this Character must be by Institution.

This exclusion of sound symbolism – at least of the sort invoked by Comenius and others – is a significant absence in light of his colleague Wallis’s obsession with the topic, but it is not one that appears to have been noted in the modern secondary literature.Footnote15 Wilkins does, however, touch upon another quite different and quite independent type of sound symbolism, which, as we shall see, turns out to have a Wallis connection.

Among a number of different ways in which his philosophical language can be written down, Wilkins discusses what can be seen as a ‘phonetic real character’; a sort of alphabet where each symbol gives articulatory directions for how the sound that it represents should be produced. This is what Gérard Genette terms articulatory phono-mimesis (1995: chapter 5). In what follows, I shall refer to these alphabets as phono-mimetic in Genette’s sense. In terms of Dalgarno’s taxonomy this is an iconic mapping from Pneumatology to Schematology, i.e. from articulatory phonetics onto visual representation. Both of these levels may be arbitrary, but the mapping itself may nevertheless be an iconic one (i.e showing their isomorphism).Footnote16 Wilkins offers two forms of a phonetic alphabet of this sort, one arbitrary and the other iconic. It is of course the iconic variety which will be of most interest to us. The first of Wilkins’s two phono-mimetic alphabets can be seen in .

The various consonants to be represented can be seen at the centre of the table; in column 9; and across the top are the vowels with which each of the consonants can combine, on the left with the vowel preceding, and on the right with the vowel following. The composite symbols thus represent syllables. This is a clear and rational form of phonetic script, but it is not strictly an iconic one: the strokes and squiggles invented to represent the various articulatory components are each individually quite arbitrary.Footnote17

Wilkins’s second form of phono-mimetic alphabet (see ) does however attempt to be a fully iconic one, in the narrow sense of the term.

In this case the table consists of a set of pictorial images showing a cross-section of the vocal apparatus. Each vocal sound is represented by an image which indicates its manner of production: the position of the tongue and the lips, the direction of the airstream, and whether the vocal cords are vibrating. At the top right-hand corner of each cell in the diagram one can see a symbol which represents this information in a highly stylised but still iconic way, as can be seen in , which shows the cells for the sounds from the middle of the table representing the sounds DH, TH and NG.

These symbols are designed to be actual pictures, albeit stylised and schematic, of the articulatory positions and settings by which the sound is produced. To use Wilkins’s own words about this form of representation: ‘It hath in the shape of it some resemblance to that Configuration which there is in the Organs of speech upon the framing of several Letters. Upon which account it may deserve the name of a Natural Character of the Letters’ (Wilkins Citation1668, 375). This is precisely what Genette means by a phono-mimetic alphabet: one where the symbols are constructed in such a way as to give an iconic representation of the articulatory manner in which the sound represented is produced. It is also precisely what critics like John Webster had been demanding the universities should be promoting.

Now, for an informed contemporary reader there is a semi-concealed but unambiguous allusion that Wilkins is unmistakably making here. All of the images in this table are of a man with his hair uncovered, except the one right in the middle of the page who is wearing what looks like a turban, and who is representing the articulation of the voiceless dental fricative TH. For many years I have shown this page to friends and colleagues and asked: why a turban? and why the voiceless fricative TH? Might it be because this is an English phoneme which speakers of many European languages find difficult to pronounce? The answer turns out to be a less complicated one. The template for Wilkins’s images is copied directly from a book which had appeared in 1667, while the Essay was being prepared for the press, namely Francis Mercurius van Helmont’s Alphabetum naturae.Footnote18 The match between Van Helmont’s cross-section of the vocal organs and those of Wilkins is immediate to the eye (see ).

Figure 5. Phono-mimetic image from Wilkins’s essay (1668: 378), to the left, and van Helmont’s Alphabetum Naturae (Citation1667), to the right.

What looks like a turban in Wilkins’s image for the sound TH is clearly an explicit cross-reference to the headband in van Helmont’s images, on which is written the name of the letter being represented. There is thus a message encoded into this page of the Essay which Wilkins would have expected his informed readers to pick up, and which parallels the reply that Ward made to Webster in connection with their dispute about the ‘language of nature’. What is being worked out here rationally and experimentally is what the Cabbalists and the Rosicrucians have vainly sought in the mystic analysis of Hebrew (cf. Ward Citation1654: 22, quoted above).

Having myself for many years missed this cross-reference from Wilkins to van Helmont, I find some small comfort in the fact that modern scholars who have worked in detail on van Helmont’s Natural Alphabet of Hebrew seem to have missed seeing it thus obliquely copied by Wilkins. I should add, in passing, that modern commentators on van Helmont seem unable to make sense of his articulatory phonetics. This applies even to Gérard Genette, who is generally reliable. He uses van Helmont’s Alphabetum Naturae as a paradigm example of articulatory phono-mimesis, but he confesses that he can’t fully understand the articulatory positions that some of the images are meant to represent, blaming this on his own possible incompetence.Footnote19 The reason why he finds this perplexing is that van Helmont’s images of the Hebrew letters do not describe the articulation of the individual sounds of the language, but rather the pronunciation of the names of the letters.Footnote20 In this he is of course following the Cabbalistic tradition. The only modern scholar that I know of who has given a coherent linguistic account of van Helmont’s Alphabetum Naturae is Joachim Gessinger in his excellent book Gessinger (Citation1994, 633–640).

Wilkins got the pictorial model for his phono-mimetic alphabet from van Helmont, but that is not the source for the phonetic script itself, those schematic diagrams of articulation in the top right of each cell of the table (which in this case do indeed represent the power rather than the name of the letter). This was also borrowed – and from none other than John Wallis, as emerges from a final piece of evidence, deriving from the dispute between Wallis and William Holder about the teaching of language to the deaf.

In 1678 John Wallis had an acrimonious exchange of pamphlets with William Holder (Wallis Citation1678, Holder Citation1678). The dispute was ostensibly about who had succeeded in teaching a surdo-mute boy to speak, but an equally important issue was their relative supremacy in advising Wilkins on matters of phonetics in connection with the Essay. The boy in question was Alexander Popham, who was from a wealthy family living at Littlecote House, a few miles south of Oxford. Popham was profoundly deaf and would have been legally debarred from inheriting any property if this had further made him unable to speak and write. Consequently in 1659 the family sent the boy to William Holder, who undertook the task of teaching him to speak. According to Holder’s own account, he succeeded in this, but had to leave Alexander’s education unfinished when he moved elsewhere. A couple of years later, in 1662, Wallis was then asked to teach language to Alexander. According to Wallis, he had to start from scratch, as Alexander could not say or understand a single word, but through Wallis’s instruction he became capable of speaking and understanding English.

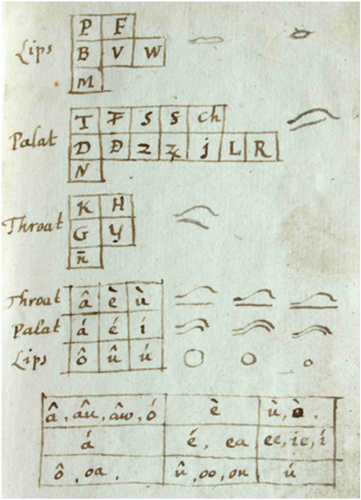

The details of the subsequent dispute about who was to be credited with the success of this educational experiment need not concern us here. What is relevant, however, is that a small leather-bound notebook has recently come to light at Littlecote House which contains a graduated manual for teaching language to the deaf.Footnote21 This is written in Wallis’s own hand, and is clearly made for the use of Alexander Popham; the first page is inscribed ‘Alexander Popham, His book’, and is conveniently dated ‘6 November 1662’. On page 2 of the notebook is the set of tables with the various consonants and vowels of the English language. And beside each of these tables we find diagrams that should look familiar; they are small line-drawings of the articulatory positions required for the pronunciation of the sounds in question ().

Figure 6. A page from the notebook devised by Wallis for teaching Alexander Popham to speak. Image courtesy of Warner Leisure hotels.

Closer study of the similarities between the stylised phono-mimetic symbols that Wallis is here using in 1662 and the schematic diagrams deployed by Wilkins in his second phonetic alphabet confirms that the one must have served as the model for the other. Furthermore Wallis’s invention of the phono-mimetic alphabet had a longer afterlife, since Wilkins’s two phono-mimetic alphabets themselves served as the model for the ‘organic and universal alphabets’ developed by Charles de Brosses in the following century.Footnote22

Conclusion

In order to reconstruct Wallis’s view of sound symbolism I have attempted to introduce a set of seventeenth-century concerns with language all of which impinge on the way people understood how signs work. Taken individually and separately, as they sometimes are, each of these perspectives on its own will seem simplistic and naive to a modern reader. But once these are assembled together, a rich and interesting discussion emerges.

John Wallis had a delicately nuanced view of the role of sound symbolism in language. He had radical doubts whether a full philosophical language could be made exclusively from sound symbolic elements, but he was nevertheless obsessively preoccupied with collecting specimens of language-specific sound symbolism. He thought that some sound symbolic elements occur in all human languages, and was of the chauvinistic opinion that English was better than all other languages in this respect. Most importantly, he thought that a fundamental principle of iconicity was not incompatible with a fundamental principle of arbitrariness in the way signs and languages work.Footnote23 Wallis, like Dalgarno, clearly thought that a proper understanding of the balance between iconicity and arbitrariness was the key to understanding language itself – the linguistic equivalent to finding the philosopher’s stone in chemistry. Since he kept on and on searching throughout his life, he was not convinced that he had yet found it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Cram

David Cram is an Emeritus Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford. By background and teaching experience he is a theoretical linguist, but his primary research interest has been in the history of ideas about language, with a special focus on the seventeenth century. His latest book, co-authored with Jaap Maat, is John Wallis on Teaching Language to a Boy Born Deaf: The Popham Notebook and Associated Texts (Cram and Maat 2017).

Notes

1 This article is a revised version of a paper first presented at the conference ‘Towards a History of Sound-Symbolic Theories’, organised by Luca Nobile at Dijon in 2014.

2 For the larger context of Wallis’s grammar, see Funke (Citation1941), Padley (Citation1985), 190–215 and Cram (Citation1994, Citation2009). His description of sound symbolism was picked up not just by other thinkers in Britain but also on the continent by philosophers such as Leibniz (see Gensini Citation1991, 218–221).

3 It is worth mentioning that Wallis certainly knew Mersenne’s account of sound symbolism, which is to be found in his two-volume work on the theory of music, since he produced a tract of his own on music theory and cites Mersenne in detail. But there is no mention of sound symbolism in any of Wallis’s discussions of music theory.

4 For an up-to-date survey of the place of philosophical language in Comenius’s thought, see the article by Pavlas in this volume and the background references there given. For more specific details, see in particular his analysis of the role of Mersenne as a source for Comenius’s system (Pavlas Citation2017), and his discussion of the relation between Comenius and Leibniz (Pavlas Citation2023).

5 For differing views on the impact of Comenius’s universal language scheme see DeMott (Citation1955) and Salmon (Citation1979), 131–9; for earlier views on Comenius more generally, see Cram (Citation1989) and Přívratská (Citation1990).

6 Comenius (Citation1966); trans. Dobbie (Citation1989).

7 Wallis does not himself further discuss the relation between the semantic value of these prepositions and the phonæsthetic value of the vowels used to represent them, although this was a central feature of other contemporary schemes, such as Comenius’s philosophical language; see his Panglottia, trans. Dobbie (Citation1989), 90–91.

8 The clockwork calculating machine had recently been invented, by Blaise Pascal in 1642, and these schemes looked like just the sort of algebraical software that would go with this new hardware.

9 For a general introduction to Böhme’s thought see Pektaş (Citation2006); on the reception of his ideas in Britain, see Nate (Citation1995); on the larger context of occultism at this period, see Vickers (Citation1984).

10 On the linguistic aspects of this tradition, see the milestone work by Gershom Scholem (Citation1970). Note that in this tradition it is the names of the letters that God utters, not the simple phonetic value of the letters.

11 On these English sects, notably a network centred on Anne Conway, see Coudert (Citation1978), (Citation1999).

12 Ward follows this remark with a number of mocking paragraphs written in a parody of the florid style of the Cabbalists and Rosicrucians (Ward Citation1654: 22–23).

13 To my knowledge there is nowhere that Wallis himself explicitly categorises sound symbolism of both these sorts as ‘arbitrary’, but the more I work on Dalgarno the more confident I am that on this point he is in effect acting as Wallis’s mouthpiece.

14 On the larger background to Wilkins’s scheme, see Maat (Citation2004), Maat & Cram (Citation2006) and Lewis (Citation2007).

15 An exception is the work of Isermann (Citation1996) & (Citation2007).

16 In the nineteenth century this form of phonetic representation came to be known as Visible Speech, a term coined and popularised by Alexander Melville Bell (Citation1867).

17 More precisely, to use a distinction developed by Roman Jakobson on the basis of the Peircean theory of signs (Jakobson Citation1965, 26–31, cf. Fischer and Nänny Citation1999, xvi-xvii), these symbols are not ‘iconic images’, although they do fall into the larger and looser category of ‘iconic diagrams’, on the grounds that each distinct phonetic contrast is represented by a single [arbitrary] symbol differentiated by its spatial orientation. I am grateful to Luca Nobile for discussion of this point.

18 Van Helmont’s full title runs: Alphabeti verè naturalis Hebraici brevisssima delineatio, but contemporaries used the short-title Alphabetum naturae. It was reviewed in Philosophical Transactions, 1668, 2: 603–604.

19 ‘Certaines de ces positions laissent perplexe, mais il faut sans doute en accuser l’incompétence du lecteur’ (Genette Citation[1976] 1995, 73). Coudert and Corse’s analysis and translation of Van Helmont’s Coudert (Citation2007) does not, oddly, include any linguistic explanation of the phono-mimetic images, and consequently the problem which Genette notices seems not to have presented itself.

20 Thus the image for the letter aleph (see above) clearly depicts the tongue making contact with the hard palate to form the lateral consonant ‘l’ of the name of the letter ALEPH; this is not an articulation needed for the open vowel [a] alone, which is the alleged value or power of this letter.

21 For the full text of the Popham Notebook, together with the pamphlets exchanged between Wallis and Holder in 1678, see Cram and Maat (Citation2017).

22 See de Brosses (Citation1765): vol. I, chapter V ‘De l’alphabet organique et universel’; on the indebtedness of de Brosses to Wilkins’s Essay, see Coulaud (Citation1981), 300 and Nobile (Citation2005): cx. I am grateful to Luca Nobile for this reference and for helpful correspondence on a number of issues relating to this paper.

23 On the balance between these two principles, compare what his contemporary John Locke has to say in his Essay (1690, book 3, chapter 2, §8): ‘Tis true, common use, by a tacit Consent, appropriates certain Sounds to certain Ideas in all Languages; which so far limits the signification of that Sound, that unless a Man applies it to the same Idea, he cannot speak properly’. On the larger history of this issue, see Joseph (Citation2000).

References

- Bell, Alexander Melville. 1867. Visible Speech: The Science of Universal Alphabetics, or Self-Interpreting Physiological Letters, for the Writing of All Languages in One Alphabet. London: Simpkin and Marshall.

- Böhme, Jacob. 1651. De Signatura Rerum: Or the Signature of All Things. London: Gyles Calvert.

- Böhme, Jacob. 1654. Mysterium Magnum: Or, an Exposition of the First Book of Moses Called Genesis. London: Humphrey Blunden.

- Brosses, Charles de. 1765. Traité de la formation méchanique des langues et des principes physiques de l’étymologie. Paris: Saillant Vincent Desaint.

- Comenius, Jan Amos. 1668. “Linguae universalis ratio.” In Via Lucis, 74–81. Amsterdam: Christophorum Cunradum.

- Comenius, Jan Amos. 1966. Panglottia. In De Rerum Humanorum Emendatione Consultatio Catholica, part V, vol. II, 147-204. Prague: Academica Scientiarum Bohemoslavaca. [Trans. Archie M.O. Dobbie. 1989. Panglottia. Shipton-on-Stour: Drinkwater].

- Coudert, Allison P. 1978. “Some Theories of a Natural Language from the Renaissance to the Seventeenth Century.” Studia Leibnitiana Sonderheft 7: 56–114.

- Coudert, Allison P. 1999. The Impact of the Kabbalah in the 17th Century: The Life and Thought of Francis Mercury Van Helmont, 1614–1698. Leiden and New York: Brill.

- Coudert, Allison P. 2007. The Alphabet of Nature by E.M. van Helmont. Translated with an Introduction and Annotations. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

- Coulaud, Micheline. 1981. “Les mémoires sur la matière étymologique de Charles de Brosses.” Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 199: 287–352.

- Cram, David. 1989. “J.A. Comenius and the Universal Language Scheme of George Dalgarno.” In Symposium Comenianum 1986, edited by Marie Kyralová & Jana Přívratská, 181–187. Prague: Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences.

- Cram, David. 1994. “Universal Language, Specious Arithmetic and the Alphabet of Simple Notions.” Beiträge zur Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft 4: 1–21.

- Cram, David. 2009. “John Wallis’s English Grammar (1653): Breaking the Latin Mould.” Beiträge zur Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft 19 (1): 177–201.

- Cram, David and Jaap Maat. 2001. George Dalgarno on Universal Language: The Art of Signs (1661), The Deaf and Dumb Man’s Tutor (1680), and the Unpublished Papers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cram, David, & Jaap Maat. 2017. John Wallis on Teaching Language to a Boy Born Deaf: The Popham Notebook and Associated Texts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cram, David, & Masataka Miyawaki. Forthcoming. John Wallis on Etymology, Sound Symbolism; with a Critical Edition of Chapter 14 ‘On Etymology’ of the Grammatica Linguæ Anglicanæ. Münster: Nodus.

- Dalgarno, George. 1661. Ars Signorum, Vulgo Character Universalis Et Lingua Philosophica. London: J. Hayes.

- Dalgarno, George. 1680. Didascalocophus or the Deaf and Dumb Mans Tutor. Oxford: at the Theater.

- Debus, Allen G. 1970. Science and Education in the Seventeenth Century. The Webster-Ward Debate. London and New York: MacDonald and American Elsevier.

- DeMott, Benjamin. 1955. “Comenius and the Real Character in England.” Publications of the Modern Language Association 70 (5): 1068–1081. https://doi.org/10.2307/459887.

- Dobbie. 1989. Panglottia. Shipton-on-Stour: Drinkwater.

- Firth, John Rupert.1930. Speech. London: Ernest Benn. [Reprinted in The tongues of men and Speech, 139–211. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fischer, Olga, & Max Nänny. 1999. “Introduction: Iconicity as a Creative Force in Language Use.” In Form Miming Meaning, edited by O. Fischer & M. Nänny, xv–xxxvi. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins.

- Funke, Otto. 1941. Die Frühzeit der englischen Grammatik: Die humanistische-antike Sprachlehre und der national-sprachliche Gedanke im Spiegel der frühneuenglischen Grammatiker von Bullokar (1586) bis Wallis (1653). Bonn: Herbert Lang and Cie.

- Genette, Gérard. [1976] 1995. Mimologics. Translated by Thaïs E. Morgan; With a Foreword by Gerald Prince. Lincoln/London: University of Nebraska.

- Gensini, Stefano. 1991. Il Naturale e il Simbolico: Saggio su Leibniz. Rome: Bulzoni.

- Gessinger, Joachim. 1994. Auge und Ohr: Studien zur Erforschung der Sprache am Menschen 1700–1850. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Helmont, Van, & Francis Mercurius. 1667. Alphabeti verè naturalis Hebraici brevisssima delineatio. Sulzbach: Abraham Lichtenthaler.

- Holder, William. 1678. A Supplement to the Philosophical Transactions of July, 1670: With Some Reflexions on Dr. John Wallis, His Letter There Inserted. London: Henry Brome.

- Isermann, Michael M. 1996. “Rational Representation or Secret Analogy? Some Remarks on the Philosophical Language of John Wilkins.” Beiträge zur Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft 6: 53–77.

- Isermann, Michael M. 2007. “Letters, Sounds and Things: Orthography, Phonetics and Metaphysics in Wilkins’s Essay (1668).” Historiographia Linguistica 34: 213–256. https://doi.org/10.1075/hl.34.2-3.03ise.

- Jakobson, Roman. 1965. “Quest for the Essence of Language.” Diogenes 51: 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/039219216501305103.

- Joseph, John. 2000. Limiting the Arbitrary: Linguistic Naturalism and Its Opposites in Plato’s Cratylus and Modern Theories of Language. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Kemp, J. Alan. 1972. John Wallis’s Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman.

- Lewis, Rhodri. 2007. Language, Mind, and Nature: Artificial Languages in England from Bacon to Locke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maat, Jaap. 2004. Philosophical Languages in the Seventeenth Century: Dalgarno, Wilkins, Leibniz. Dordrect: Kluwer.

- Maat, Jaap, & Cram. David. 2006. “Universal Language Schemes in the Seventeenth Century.” In Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, edited by Keith Brown. Vol 13, 259–264. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Magnus, Margaret. 2013. “A History of Sound Symbolism.” In The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics, edited by Keith Allan, 191–208. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mersenne, Marin. 1636. Harmonie universelle, contenant la theorie et la pratiqve de la mvsiqve. Paris: Sebastien Cramoisy.

- Miyawaki, Masataka. 2001. “John Wallis on Sound Symbolism: One Aspect of Seventeenth-Century Morphophonemics.” Studies in the Humanities: A Journal of the Senshu University Research Society 69: 199–223.

- Nate, Richard. 1995. “Jacob Böhme’s Linguistic Ideas and Their Reception in Seventeenth-Century England.” Beiträge zur Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft 5: 185–202.

- Nobile, Luca. 2005. Il ‘Trattato della formazione meccanica delle lingue e dei prinicipi fisici dell’etimologia’ (1765) di Charles de Brosses: un caso di materialismo linguistico-cognitivo nell’età dei lumi. Edizione italiana, introduzione critica e commento. Rome: La Sapienza.

- Padley, George A. 1985. Grammatical Theory in Western Europe 1500-1700. Trends in Vernacular Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pavlas, Petr. 2017. “‘The Best of All Possible Languages’: Marin Mersenne as a Source of Comenius’s Combinatorial Approach to Language Planning.” Acta Comeniana 31: 23–41.

- Pavlas, Petr. 2023. “Two Hostile Bishops? A Reexamination of the Relationship Between Peter Browne and George Berkeley Beyond Their Alleged Controversy.” Intellectual History Review 33 (4): 629–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496977.2023.2272110.

- Pektaş, Virginie. 2006. Mystique et Philosophie: Grunt, Abgrunt et Ungrund chez Maître Eckhart et Jacob Böhme. Amsterdam: B.R. Gruner.

- Přívratská, Jana. 1990. “On Comenius’ Universal Language.” In History and Historiography of Linguistics, edited by H.-J. Niederehe & E.F.K. Koerner, 349–356. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Salmon, Vivian. 1979. The Study of Language in Seventeenth-Century England. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Scholem, Gershom.1970. “Der Name Gottes und die Sprachtheorie der Kabbala.” In Judaica, 7–70. Vol. III. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Vickers, Brian. 1984. “Analogy Vs. Identity: The Rejection of Occult Symbolism, 1580-1680.” In Occult and Scientific Mentalities in the Renaissance, edited by Brian Vickers, 95–163. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wallis, John. 1653. Grammatica Linguæ Anglicanæ. Oxford: Leonard Lichfield.

- Wallis, John. 1678. A Defence of the Royal Society. London: Thomas Moore.

- Wallis, John. 1699. Opera Mathematica. Vol. 3. Oxford: E Theatro Sheldoneano. [5th edition of the English Grammar in vol. 3, Opera quædam miscellanea].

- Ward, Seth. 1654. Vindiciae Academiarum, containing, some briefe animadversions upon Mr Websters Book, stiled, The Examination of the Academies. Oxford: Leonard Lichfield. [Facsimile in Debus 1970, pp. 193–259].

- Webster, John. 1653. Academiarum examen, or, The examination of academies. London: Giles Calvert. [Facsimile in Debus 1970, pp. 67–110].

- Wilkins, John. 1668. An Essay Towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language. London: S. Gellibrand and J. Martyn.