Abstract

Entrepreneurship education is critical to many countries’ efforts to ameliorate youth unemployment. Embedding entrepreneurship content or skills into school subjects can contribute to these efforts. Although youth unemployment is especially rife in South Africa, its school curriculum does not include extensive entrepreneurship education. For these reasons, researchers have been investigating and proposing various ways to develop and expand entrepreneurship in the school curriculum. Previous studies have explored if and how entrepreneurship could potentially be purposely embedded in the South African Senior Phase Technology curriculum, finding positive potential for such an endeavour. Still, most studies have only explored the intended curriculum without considering their implementation in the enacted curriculum. Technology teachers’ voices—the enactors of the intended curriculum—were therefore overlooked. The current study explored the perceptions of experienced Technology teachers regarding the feasibility of embedding entrepreneurship education in the existing Senior Phase Technology curriculum. Technology teachers were invited to make practical suggestions for merging entrepreneurship into the Technology curriculum. A qualitative phenomenological strategy of inquiry was used. Purposive sampling resulted in 30 experienced Technology Education teachers from the North West province completing a questionnaire. Data were analysed thematically and several interesting findings emerged. Technology teachers were overwhelmingly supportive of embedding entrepreneurship in this subject, offering numerous practical and feasible suggestions in this regard. These suggestions could be used to strengthen the intended and enacted Technology curriculum in South Africa by making the learning therein more meaningful and life-relevant for learners.

Background and Purpose

Youth unemployment has been a severe problem for decades, yet it continues to rise. Granting this is a global issue, South Africa, in particular, struggles with this problem: in the second quarter of 2023, the youth unemployment rate, representing jobseekers between 15 and 24 years old, was reported to be 60.7% (Statistics South Africa, Citation2023). Contributing to this conundrum, more than 50% of unemployed persons reportedly do not have matric—the high school exit-level qualification in South Africa, also called Grade 12 (Statistics South Africa, Citation2023: 8). These statistics underscore the importance of endeavouring to address youth unemployment through education before learners leave school or reach Grade 12. As attendance is compulsory, school education seems the ideal space in which to attempt to address, or at least ameliorate, this problem. One of the focused efforts of the South African Department of Basic Education (DBE) to ameliorate the country’s youth unemployment problem is the expansion of entrepreneurship education in the school curriculum.

Entrepreneurship education has been implemented in the school systems of many countries worldwide, such as Kenya, Ghana and Mozambique (Robb et al., Citation2014) and across Europe (Val et al., Citation2017). Citing McGuigan (Citation2016), Du Toit and Gaotlhobogwe (Citation2018: 39) describe entrepreneurship education as ‘knowledge, skills and attitudes which contribute to entrepreneurial thinking and actions that learners can apply in their everyday lives, their future careers, their communities and/or their own new ventures’. The rationale for its inclusion in school education varies; however, many scholars agree that the knowledge, skills and attitudes associated with entrepreneurship education contribute value to learners’ learning by preparing them for life and the world of work (Bacigalupo et al., Citation2016; Du Toit, Citation2023; Grigg, Citation2021; McGuigan, Citation2016; Schoeninger et al., Citation2021). Knowledge about or for entrepreneurship includes content such as meeting the needs of target markets, qualities of successful products, calculations related to the costing and pricing of products or developing marketing plans (Du Toit & Ntimbwa, Citation2023; Khan et al., Citation2021). The list of skills developed in entrepreneurship education is extensive, but most often includes adaptability, problem-identification, problem-solving, collaboration, communication, creative thinking, innovation and learning from mistakes (Khan et al., Citation2021; Schoeninger et al., Citation2021). Attitudes associated with entrepreneurship education are often referred to as a problem-solving mindset, a ‘can-do approach’, or being passionate about the task (Du Toit & Ntimbwa, Citation2023). In other words, the learning embedded in entrepreneurship education holds many benefits for learners in their everyday lives, as well as in their future employment—whether they become entrepreneurs or not. Within this broad rationale, one fundamental motivation for its inclusion in schools is to contribute to reducing youth unemployment and poverty by fostering economic and employment growth (Du Toit & Gaotlhobogwe, Citation2018; Hutchinson & Kettlewell, Citation2015; Schoeninger et al., Citation2021; SAVision2020, Citation2016; Val et al., Citation2017; Walmsey & Wraae, Citation2022).

South Africa’s Education Efforts Towards Expanding Entrepreneurship Education in Schools

The DBE’s drive to expand entrepreneurship education in the South African school system has its foundations in the ‘Entrepreneurship in Schools’ Sector Plan (DBE, Citation2016). One of the Sector Plan’s key goals is to contribute to reducing the country’s high unemployment (Poliah, Citation2023). The Plan is currently being rolled out to strengthen the school curriculum through, amongst other initiatives, the inclusion of entrepreneurship as a cross-cutting theme in various subjects and school phases (Poliah, Citation2023). At the time of writing this article, some 13,215 schools had already implemented some of the entrepreneurship education initiatives informed by the Sector Plan (Morcowitz, Citation2023). These implementation efforts are, however, not static and continuously evolve towards improvement and expansion of the ideas. The current study, therefore, explores one way to potentially contribute to these efforts: expanding entrepreneurship education in Technology education.

The Potential of Technology Education to Contribute to Entrepreneurship Education

Several other countries on the African continent—for example, Botswana, Kenya and Namibia—have embraced entrepreneurship education as a means of reducing youth unemployment and have embedded entrepreneurship in their Technology and vocational subject curricula for this purpose (Du Toit & Gaotlhobogwe, Citation2018; McCarthy, Citation2023). The Senior Phase, offered to learners up to the mean age of around 16 years, is the ideal phase for expanding entrepreneurship education in South African Technology education, as many learners leave school before reaching the Grade 12 formal school exit level (McCarthy, Citation2023). The problem-based nature of Technology education and its contribution towards practical knowledge and skills development make this subject an ideal choice for expanding entrepreneurship education in the South African school curriculum (Du Toit, Citation2020). This notion is confirmed in view of the DBE’s goals of utilising entrepreneurship education to develop ‘learners into active citizens with a mindset geared towards acknowledging and actively engaging with the socio-economic problems surrounding them and their communities’ by developing learners’ entrepreneurial skills and competencies (Poliah, Citation2023: 31, 35).

The African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education has, to date, published three papers that explored the potential of Technology education to contribute to entrepreneurship education: Du Toit and Gaotlhobogwe (Citation2017) initially reported the potential of including entrepreneurship education in the South African and Botswana Technology curricula to address these countries’ issues of poverty and unemployment, particularly highlighting that product development could contribute to such a purpose. The same authors consequently published research that explored if and to what extent entrepreneurship education is included in the Technology curricula of South Africa and Botswana (Du Toit & Gaotlhobogwe, Citation2018: 40). They found some explicit and practical entrepreneurship education in the Botswana curriculum, but this critical content was inadequate in the South African curriculum (p. 42). These authors also found that content that could possibly be linked to entrepreneurship in the South African Technology curriculum is ambiguous and is often irrelevant to the lives of learners, which led to their conclusion that its entrepreneurial potential has been neglected in the current Technology curriculum (p. 45). Aiming to address some of the recommendations made in the previous two papers, Du Toit subsequently explored and developed proposals for including and effectively scaffolding entrepreneurship education in Senior Phase Technology education. As a result, she published a proposed conceptual framework for ‘threading a spinal cord of entrepreneurship education through the backbone of the design process’ in Technology education (Du Toit, Citation2020: 185-189). The studies concluded that South Africa’s intended Technology curriculum has the potential to develop entrepreneurship education based on the content knowledge, such as materials and processing of materials, and skills, such as problem-solving, creativity and communication, included in it. However, this potential is not fully achieved owing to a lack of relevant links between the products or systems that learners develop in Technology and entrepreneurial opportunities (Du Toit, Citation2020). Some efforts have therefore been made to explore how Technology education can contribute towards the Sector Plan of the DBE (Citation2016) for expanding entrepreneurship education in the South African curriculum.

However, the efforts to date were only focused on the intended curriculum, which is just one of three curriculum levels. The first level—the intended curriculum—describes the content and skills that are intended to be included in a subject and sometimes includes guidelines on how to facilitate such learning (McCarthy, Citation2023: 25; Thijs & Van den Akker, Citation2009: 10). In other words, it prescribes the teaching and learning that should take place in a particular subject. The second level is the enacted or implemented curriculum, which reflects how teaching and learning are practically implemented by teachers (McCarthy, Citation2023: 26; Thijs & Van den Akker, Citation2009: 10). The enacted curriculum, therefore, determines to a great extent how, or even if, the intended learning is actually realised in practice. The third curriculum level entails the attained curriculum—including how learners experienced the curriculum and an assessment (measured) of the learning resulting from enacting the intended curriculum (Thijs & Van den Akker, Citation2009: 10).

Previously published research on this matter emphasised the need for practical suggestions to include, scaffold or unpack entrepreneurial learning in the Senior Phase curriculum, which will guide teachers in enacting teaching and learning towards implementing effective entrepreneurship education in Technology education (Du Toit, Citation2020; Du Toit & Gaotlhobogwe, Citation2018). Du Toit (Citation2020) asserted that ‘[i]t would also be advisable to consolidate the integration of entrepreneurship education by a close alignment with the interpreted and the implemented curriculum’ to enable Technology teachers to ‘encourage this valuable learning in their learners’ (p. 189). Considering that only one level of the curriculum has, as yet, been explored for expanding entrepreneurship education in Technology education, it is evident that further research is needed to contribute to our understanding of, and suggestions for, how entrepreneurial intentions can or might be enacted in practice in this subject. Bridging this gap was the purpose of the study reported in this paper. To provide insights regarding the feasibility of embedding and implementing entrepreneurship education in the enacted Senior Phase Technology curriculum, the current study, therefore, explored the perceptions of experienced Technology teachers, who were also invited to make practical suggestions for implementing or enacting entrepreneurship education in the Technology curriculum. Although research on the attained or assessed curriculum level is also lacking, it is not addressed in the current paper. However, it is recommended that future research explores this curriculum level with a similar purpose to the one explored in the current investigation.

Theoretical Underpinnings for the Study

The current study was conducted within the constructivist theoretical framework, as the researchers intended to describe how individuals (in this case, Technology teachers) might gain or create knowledge and learn from their encounters, in line with Olusegun’s (Citation2015: 66) descriptions. Technology teachers’ self-directed and collaborative efforts to construct knowledge and understanding regarding enacting entrepreneurship education in their subject were the focus of the investigation. Teachers’ inputs (or ‘voices’) as the co-constructors of knowledge were therefore valued and included to contribute insights in addressing the research problem. Including Technology teachers’ voices provided an opportunity to add insights on the enacted curriculum in this subject that would be ‘representative of the full range of perspectives and experiences in the field’ (Heimans et al., Citation2023: 105)—and provide insights that have not yet been explored.

The phenomenological research was approached with an interpretivist worldview, based on the belief that different people (in this case, Technology teachers) interpret and experience events differently, which results in different perspectives that should all be considered as contributing insights to the investigation, in line with explanations by Van der Walt (Citation2020). The ‘events’ in the current investigation were Technology teachers’ knowledge of entrepreneurship education and how they believed that it could be merged into Technology education, based on their experiences of the enacted curriculum in the subject. Therefore, the researchers conducting this study in the interpretivist paradigm were responsible for interpreting, explaining, understanding and defining the social reality of the participating Technology teachers in adherence to the recommendations of Van der Walt (Citation2020) for constructivist and interpretivist research.

Research Methods

An explorative qualitative investigation was used as part of a phenomenological inquiry strategy. The phenomenological research focused on Technology teachers’ personal experiences, understanding and perceptions of the phenomenon under investigation, namely implementing entrepreneurship education in the Senior Phase Technology curriculum. The research population encompassed all Technology teachers in South Africa’s North West Province with at least three years of teaching experience in the subject. From this population, 30 suitably experienced Senior Phase Technology teachers were purposely selected. One participant had 3–5 years of Technology teaching experience, another 10 participants had 5–10 years of experience, and the other 19 had Technology teaching experience exceeding 10 years. Convenience and accessibility informed the sampling decision. After obtaining the necessary permissions for conducting the research from national and provincial educational departments and ethical clearance from the tertiary institution where the study was scientifically approved (see below), participants were invited to participate. Those indicating their willingness to voluntarily participate were asked to complete informed consent forms before contributing to the data. Data were collected using a primarily qualitative questionnaire. The paper-based questionnaires, together with an explanation of the background of the research and informed consent forms, were presented to participants by an objective administrator. Participation was voluntary and data was provided anonymously.

The items in the questionnaires revolved around several aspects related to entrepreneurship education in the implemented or enacted Senior Phase Technology curriculum and included nine questions. Five questions required yes, no or maybe answers, and two others were Likert scale-type questions. However, all seven of these questions included a request that participants should provide a (qualitative) justification for their choices, which was the focus of the research. In the other two questions participating Technology teachers were asked to give their opinions or suggestions. Thematic data analysis was used to mine and interpret the qualitative data, which determined the findings from the questionnaire. The data were coded by hand, to explore ‘theories of knowing and an understanding of the phenomenon of interest’, as recommended by Saldañha (Citation2013: 61). In vivo and descriptive coding were applied sequentially, followed by applying colours to categorise codes and eventually developing themes from the categories. The trustworthiness of the analysis procedures and findings was established by applying the guidelines for the constructs of credibility, transferability, dependability and conformability recommended by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985), with support and input from the study supervisors. The current paper only reports on two main themes: (a) experienced Technology teachers’ perceptions regarding the feasibility of embedding entrepreneurship education in the existing Senior Phase Technology curriculum; and (b) an invitation for their suggestions for implementing or embedding entrepreneurship in the Technology curriculum.

All ethical considerations stipulated by the DBE and the University’s Faculty of Education Research Ethics Committee were judiciously followed. The ethics approval number for the study was NWU-00257-22-A2.

Next, the findings emerging from the study for the two themes noted previously are described and discussed in relation to the existing literature.

Findings and Discussion

The current study intended to contribute to bridging the gap in existing research on the implementation of entrepreneurship in the enacted Senior Phase Technology curriculum. Therefore, the perceptions of experienced subject experts regarding the feasibility of embedding entrepreneurship education in the existing Senior Phase Technology curriculum were explored and are reported here. In addition, based on these subject experts’ experience of enacting the intended Senior Phase Technology curriculum, they were invited to make feasible suggestions for implementing or embedding entrepreneurship in the Technology curriculum, the second theme reported here.

Technology Teachers’ Perceptions Regarding the Feasibility of Embedding Entrepreneurship Education in the Senior Phase Technology Curriculum

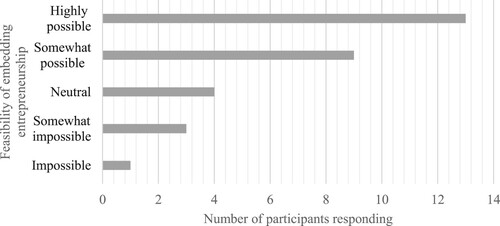

Most of the participants believed that it is possible (31%), or even highly possible (45%), to implement entrepreneurship into the existing Senior Phase Technology curriculum without too much trouble (). Only one participant believed that this would be an impossible task and three others felt that it would be somewhat possible. This finding indicates that most Technology educators might be willing to embrace and adopt entrepreneurship education as part of Technology education should the curriculum be adapted in this manner. Against the background of few teachers having focused training for entrepreneurship education and an existing lack of pedagogical guidance for such education (Du Toit, Citation2020; Du Toit & Gaotlhobogwe, Citation2018), this finding was interpreted as positive, indicative of teachers’ willingness to contribute to more meaningful learning for their Technology learners (McCarthy, Citation2023: 64).

Figure 1. Experienced Technology teachers’ perceptions of the feasibility of embedding entrepreneurship education into the existing Senior Phase Technology curriculum

Showing similar positive support for this notion, 97% of the participating teachers (n = 29) also agreed that it would be beneficial to equip Technology learners with entrepreneurship skills before they possibly exited the school system at the end of Grade 9, the last year in the Senior Phase of the South African school system. These teachers’ positive attitudes towards embracing entrepreneurship education, particularly in the Senior Phase of Technology education, were qualified by their answers to the open-ended questions. It emerged that these Technology teachers believed that including entrepreneurship in Technology education would contribute to creating jobs or income opportunities and thereby contribute to reducing unemployment in South Africa, as is evident from the following responses: Participant 10 noted that ‘Learners need to develop the skills and mindset to create their own job opportunities and if entrepreneurship skills are developed they will be able to be self-sustainable’; Participant 14 opined that learners would be enabled to ‘create products or create self-employment or employment’; and Participant 4 explained that ‘Entrepreneurship skills are needed in our country so that we can assist the government to improve [the] economy by giving skills to our learners’. This evidence points towards participants’ belief that entrepreneurship education can contribute to ameliorating the problem of youth unemployment in South Africa and that the Technology curriculum holds promise to support its implementation. In particular, their positive viewpoints regarding the potential synergy between Technology education and entrepreneurship education are based on skills development (such as critical thinking and problem-solving) and product development (i.e. learners making a product that is sellable). This finding, therefore, supports the arguments of Du Toit and Gaotlhobogwe (Citation2018) that ‘[c]ombining entrepreneurship knowledge and skills with Technology product development [can] create opportunities to generate income or employment’ (p. 40) and ‘[a]lthough entrepreneurship is not a cure for youth unemployment, several studies have linked entrepreneurship education to reducing unemployment, through skills development and the creation of opportunities for self-employment’ (p. 37).

In addition, it emerged that Participants 2 and 7 believed that including entrepreneurship education in the Technology curriculum would expand the subject’s beneficence to more learners, especially learners who are not academically inclined, as those learners could potentially combine Technology content and skills with entrepreneurship education to create an income. This finding demonstrates that the mistaken belief that Technology is not an academic subject but rather a practical, primarily skills-based subject persists—worryingly—even among some subject teachers, as revealed in these two responses. It echoes similar findings in Botswana by Gaotlhobogwe (Citation2010: 184). Technology education in other countries, such as England, is regarded as an academic subject (Vandeleur, Citation2010). Senior Phase Technology education in South Africa is, indeed, also an academic subject. It fits entirely into the description in this regard put forward by PAVLOVA (Citation2018, p.830), who states that ‘TE [technology education] is an academic subject or learning area that aims to provide practical, hands-on, technical learning experiences that stimulate creativity and imagination in primary and secondary school students to solve real and relevant problems’. Nevertheless, the incorrect perception unfortunately still emerges, because it is a hands-on subject that includes practical application and implementation of learnt skills, disregarding the depth and value of learning embedded therein. As a result, some people still believe that it is the last resort for learners who fail academically, framing the subject as ‘less than’ other academic subjects.

Participant 15 also commented that an amalgamation of entrepreneurship and Technology education might increase learners’ motivation in Technology education when describing that ‘including entrepreneurship education in Technology education might lead to learners starting to enjoy and pursue the subject even more’. Participant 25 made similar comments. This finding echoes literature asserting that learners’ motivation can be enhanced by establishing connections between classroom instruction and real-world contexts in which entrepreneurial skills can be applied (Du Toit & Gaotlhobogwe, Citation2018). In addition, it supports the notion of learner motivation stemming from meaningful learning. In other words, when learners experience that Technology education has application potential in their own lives, for example, that they can use its content or skills to generate their own income possibilities, they will experience learning in the subject as being more meaningful, which, in turn, will increase their motivation to participate in and learn in the subject. Including such an adjustment would bring the current Technology curriculum closer to the subject’s original vision that it would include life-relevant, meaningful learning supported by the development of a range of skills, including entrepreneurship skills (Reddy et al., Citation2003).

The current study’s findings imply that experienced Technology teachers believe that it is feasible to embed and implement entrepreneurship education within the existing Senior Phase Technology curriculum and that these teachers believe that such inclusion will be beneficial for learners in the South African context.

The second theme from the study reported here explored the suggestions of experienced Technology teachers for the ways in which entrepreneurship education could be embedded, implemented or realised in the Senior Phase Technology curriculum.

Teachers’ Suggestions for Implementing Entrepreneurship in the Technology Curriculum

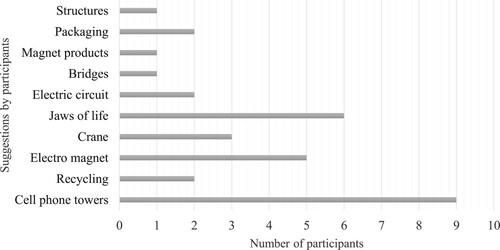

The current South African Technology school curriculum is viewed as content-dense or overloaded with topics, and teachers often lament how difficult it is to cover all of the content therein, together with the intended skills development (Umalusi, Citation2015: 12). For these reasons, it is improbable that additional content (such as entrepreneurship) can just be added to the existing Technology curriculum (McCarthy, Citation2023: 61). The time allocated per week per subject in the curriculum is also finely managed, with Senior Phase Technology only having 2 hours a week to complete all of the intended learning (DBE, Citation2011: 7). The necessary compromise to avoid content congestion could be attained if repetitive or unnecessary learning content in the Senior Phase Technology curriculum could be replaced with entrepreneurship education content or, alternatively, if teachers could identify existing content in the Technology curriculum that could be smoothly and effortlessly linked with entrepreneurship (McCarthy, Citation2023: 67). For example, existing products that learners have to design, develop and make in the curriculum can be linked to those products’ entrepreneurial (or income-generating) potential. This argument served as the foundation to invite experienced Technology teachers to make suggestions for implementing entrepreneurship into the Senior Phase Technology curriculum without contributing to the already existing curriculum overload. The suggestions of participants are shown in .

Figure 2. Experienced Technology teachers’ suggestions for combining entrepreneurship with existing Senior Phase Technology curriculum content

The existing content in the Senior Phase Technology curriculum that participants cited most for linking with entrepreneurship education was (1) cell phone towers, (2) the jaws-of-life and (3) electromagnets (). The participants believed that the learning content about the triangulation of structures in the cell phone tower project and the curriculum’s allowance for creativity in its design as part of a project (DBE, Citation2011: 16) would link well with entrepreneurship education. The cell phone tower project is problem based in that it ‘must involve disguising the tower so that it blends in with the environment, avoiding visual pollution’ and requires both individual and group work (DBE, Citation2011: 16). Learners could, therefore, potentially harness the construction skills, together with creativity and collaboration skills which they develop in this Technology project, to generate ideas to improve current cell phone tower designs, create novel tower designs, and so forth, which can create income or employment opportunities when combined with entrepreneurial knowledge and skills (McCarthy, Citation2023: 68).

The participants’ suggestions to link the jaws-of-life Technology learning content with entrepreneurship education () were based on similar ideas. The jaws-of-life learning incorporates content on pneumatic- and hydraulic systems and control, in simple terms, moving mechanisms (DBE, Citation2011: 15). It links this learning to the broad Technology focus of considering technologies’ impact on people and the environment (DBE, Citation2011: 10). Entrepreneurial learning is increasingly associated with value creation beyond only the financial. Du Toit (Citation2023: 4) notes that ‘[t]he value of the competencies, mindset and skills development embedded in entrepreneurship education have broader relevance than only for self-directed employment or value creation’. Expanding the argument, the United Nations (Citation2020, n.p.) notes that entrepreneurship not only creates jobs and contributes to economic growth but ‘can also help find practical business solutions to social and environmental challenges’, underscoring its broader value-creation purpose, but also highlighting its links to problem-based learning. Building on the same notion, Schoeniger et al. (Citation2021: 4) define entrepreneurship as ‘the self-directed pursuit of opportunities to create value for others’. This solid connection to value creation—like the requirement that learners consider the impact of their designs and ideas on others or the environment—underscores the potential for linking entrepreneurship, which shares these goals with Technology education, at this point in the existing Senior Phase curriculum. The jaws-of-life Technology content learning, together with the skills development associated with problem-based learning, as well as the shared value-creation purpose with entrepreneurship, could be used by learners to design and make novel problem-solving products that can create various types of value in learners’ lives after school—be it in life or their future careers. Embedding entrepreneurship education in Technology education, therefore, contributes to the transferability of Technology education to learners’ lived lives (McCarthy, Citation2023: 68).

Electromagnets, the Technology content cited third-most by participants for merging with entrepreneurship (), is part of a project that combines several Technology topics in designing a creative solution to a problem (DBE, Citation2011: 19). The project includes the development of several twenty-first-century skills envisaged by the Technology curriculum, including problem-solving skills, planning skills, teamwork skills, evaluation skills and communication skills, in combination with various Technology topics such as magnetism, electrical circuits, drawing skills, properties of metals, and more (DBE, Citation2011: 19). These wicked problems, which have many possible solutions (Wiek et al., Citation2014: 434), are ideal opportunities for developing learners’ critical thinking and collaboration skills and linking learning to real-world issues. Approaching Technology education in this manner and linking the project to entrepreneurship so that learners can understand how solving a problem creates additional opportunities for economic or other types of value, will make learners’ learning more meaningful and enhance their motivation to learn and participate in the subject.

Interestingly, the cell phone tower, jaws-of-life and electromagnet projects are all in the Grade 7 Technology curriculum. Grade 7 is the first of three years of the Senior Phase in the South African school system. Furthermore, an international Senior Phase Technology curriculum benchmarking investigation (Umalusi, Citation2015: 35) found that topics such as the cell phone tower and the jaws-of-life offer learning ‘contexts that are not relevant to the lives of learners … [and] should be removed from the CAPS. Changing these contexts will make [the] project work less prescriptive, allowing more room for creativity and originality’. Similarly, McCarthy (Citation2023: 69) noted that numerous other projects in the Senior Phase Technology curriculum have fewer limitations and, therefore, more potential to merge those with entrepreneurship. One example of such a life-relevant project, based on a wicked problem, is the ‘emergency shelter for disaster victims’ (DBE, Citation2011, p.20). It was unclear why the participants did not include these ‘wider options’ as suggestions.

The participating experienced Technology teachers were, therefore, invited to suggest novel ideas for possible content that could be included in Technology (perhaps in future curriculum adaptations) and which could be merged effectively with entrepreneurship education. The researchers believed that asking this open-ended question would give the participants a more substantial ‘voice’ than only limiting them to the existing curriculum content, which has been criticised for not being relevant to the learners’ realities.

Most participating Technology teachers suggested that learners make useful, life-relevant products. These suggestions included that learners make door mats, toys, steam engine cars, carpentry products or household tools (McCarthy, Citation2023: 69). Other participants suggested more general ideas, including robotics or machinery production. Another interesting sub-theme that emerged from participant responses was their suggestions that would require learners to deliver a service in addition to designing and developing a product—for example, baking, cooking, buying, selling and having a mobile tuckshop stand. Most of these products and services can be based on existing Technology content, such as material properties (DBE, Citation2011: 24) or processing (DBE, Citation2011: 36), for example. There is, therefore, still extensive unlocked potential to link existing Technology content with novel applications, which will make it more life-relevant for learners and open up entrepreneurship potential.

The current study’s findings indicate that participants’ suggestions mirror the general perception that linking entrepreneurship education with product development will be beneficial (McCarthy, Citation2023: 70), indicating these teachers’ mindset that entrepreneurship (primarily) creates economic value. There is nothing wrong with that relatively narrow mindset, as economic value created through entrepreneurship translates into income generation or job creation, which will contribute to ameliorating youth unemployment in South Africa. Therefore, embedding entrepreneurship in Technology education will move the subject closer to its originally intended goals, as reported by Reddy et al. (Citation2003).

Nevertheless, there seems to be a need for teacher training on the broader value-creation purpose of entrepreneurship, which includes (but is not limited to) social and environmental value (Du Toit, Citation2023: 4; Schoeninger et al., Citation2021: 4). In turn, if teachers are more knowledgeable regarding entrepreneurship education’s broader value-creation purpose, and can implement it in their classrooms and explain it to their learners, it will open up many more opportunities for learners to transfer Technology learning into solving real-life issues, contributing meaningfully to their communities. Technology education holds vast potential to contribute increasingly meaningful and valuable learning, especially if merged with entrepreneurial learning, and more research is necessary to explore how this can be attained.

Limitations of the Study

The study only focussed on the Senior Phase Technology intended and enacted curriculum and did not address the attained curriculum, which should be done in subsequent studies. Furthermore, only teachers from one South African province were invited to participate, so the findings are not generalisable. Participants’ foundational understanding of what entrepreneurship education entails was not established at the onset of the study. Yet, considering that all the participants were experienced in Technology education, we should not disregard their voices, especially when suggesting options to make Technology education more meaningful.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Youth unemployment continues to be a critical problem in South Africa, yet the country’s school curriculum does not include much entrepreneurship education compared with other African countries. Therefore, the current study explored how entrepreneurship education can be embedded in the enacted Senior Phase Technology education curriculum. The study built on prior investigations that explored the potential of the intended Senior Phase Technology curriculum for the same purpose. Collectively, these studies increasingly highlight the potential of Technology education to contribute to entrepreneurial learning and provide more valuable and meaningful learning to learners in the South African context. The current study shows how adding the voices of experienced Technology teachers—the enactors of the intended curriculum—can contribute to scaffolding efforts towards implementing this endeavour. The perceptions of participating Technology teachers support the feasibility of embedding entrepreneurship education in the existing Senior Phase Technology curriculum. The participants also support the Senior Phase Technology curriculum’s potential to be extended or refined with some novel practical suggestions for implementing or embedding entrepreneurship content or skills in the Technology curriculum. Most of these suggestions will contribute to supporting learners, who might develop Technology learning into entrepreneurial opportunities to generate income or self-directedly create their own jobs, using the knowledge and skills they developed in Technology education. The findings of this study contribute valuable insights and practical suggestions that can be implemented towards the attainment of the DBE’s goals of developing and expanding entrepreneurship across all subjects and phases in the South African school curriculum. Additionally, the benefits associated with such merged learning show that it will contribute to ameliorating youth unemployment when learners are taught how to use Technology knowledge and skills in combination with entrepreneurship to create various types of value—for themselves and their communities.

Future research should explore Technology teachers’ mindsets regarding entrepreneurship and potential contributions to strengthening the subject in depth. In addition, more research is needed to analyse and compare the viewpoints of female and male Technology teachers on these issues.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., & Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The entrepreneurship competence framework, EUR 27939 EN. Publication Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2791/593884

- DBE (2011). Curriculum and assessment policy statement (CAPS): Senior phase Grades 7–9 Technology. Government Printing Works.

- DBE (2016). Entrepreneurship in schools. Government Printing Works.

- Du Toit, A. (2020). Threading entrepreneurship through the design process in Technology education. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 24(2), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/18117295.2020.1802153

- Du Toit, A. (2023). Appraising the entrepreneurial mindset of university lecturers. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 27(S1), 1–16.

- Du Toit, A., & Gaotlhobogwe, M. (2017). Benchmarking Technology curricula of Botswana and South Africa: What can we learn? African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 21(2), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/18117295.2017.1328834

- Du Toit, A., & Gaotlhobogwe, M. (2018). A neglected opportunity: Entrepreneurship education in the lower high school curricula for Technology in South Africa and Botswana. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 22(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/18117295.2017.1420007

- Du Toit, A., & Ntimbwa, M.C. (2023). An evaluation of the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in secondary schools in Tanzania. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 22(9), 501–519. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.22.9.27

- Gaotlhobogwe, M. (2010). Attitudes to and perceptions of design and technology students towards the subject: A case of five junior secondary schools in Botswana. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Wales Institute, Cardiff School of Education.

- Grigg, R. (2021). EntreCompEdu, a professional development framework for entrepreneurial education. Education + Training, 63(7/8), 1058–1072. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2020-0166

- Heimans, S., Biesta, G., Takayama, K., & Kettle, M. (2023). ChatGPT, subjectification, and the purposes and politics of teacher education and its scholarship. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 51(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2023.2189368

- Hutchinson, J., & Kettlewell, K. (2015). Education to employment: complicated transitions in a changing world. Educational Research, 57(2), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2015.1030848

- Khan, N., Oad, L., & Aslam, R. (2021). Entrepreneurship skills among young learner through play strategy: A qualitative study. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 9(2), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2021.927

- Lincoln, Y.S., & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. In N.K. Denzin, & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research. Sage.

- McCarthy, F. (2023). Embedding effective entrepreneurship education in the South African Senior Phase Technology Education curriculum. Masters thesis, North-West University, Boloka. https://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/42097

- McGuigan, P.J. (2016). Practicing what we preach: Entrepreneurship in entrepreneurship education. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 19(1), 38–50.

- Morcowitz, S. (2023, August 11). Creating effective entrepreneurial education in South Africa. Paper presentation. Allan & Gill Gray Entrepreneurial Schools Think Tank: Growing the Entrepreneurial Capacity of a Nation, Honeydew, South Africa.

- Olusegun, B.S. (2015). Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 5(6), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.9790/7388-05616670

- Pavlova, M. (2018). Sustainability as a transformative factor for teaching and learning in technology education. In Handbook of technology education (pp. 827–842). Springer. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-44687-5_57

- Poliah, R. (2023, August 11). Contextualising entrepreneurship within the broader context of the curriculum roadmap. Paper presentation. Allan & Gill Gray Entrepreneurial Schools Think Tank: Growing the Entrepreneurial Capacity of a Nation, Honeydew, South Africa.

- Reddy, V., Ankiewicz, P., De Swardt, E., & Gross, E. (2003). The essential features of Technology and Technology education: A conceptual framework for the development of OBE (Outcomes Based Education) related programmes in Technology education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 13, 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022386602537

- Robb, A., Valerio, A., & Parton, B. (Eds) (2014). Entrepreneurship education and training: Insights from Ghana, Kenya, and Mozambique. World Bank Studies. World Bank. http://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0278-2

- Saldañha, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 2nd ed. Sage.

- SAVision2020. 2016. Global Entrepreneur Monitor Report: An alarmingly low level of entrepreneurial activity in spite of high unemployment. http://savision2020.org.za/global-entrepreneur-monitor-report/

- Schoeniger, G., Herndon, R., Houle, N., & Weber, J. (2021). The entrepreneurial mindset imperative, Entrepreneurial Learning Initiative (ELI). https://elimindset.com/newly-published-white-paper-theentrepreneurial-mindset-imperative/

- Statistics South Africa (2023). Quarterly Labour Force Survey—QLFS Q2:2023, 15 August 2023. www.statssa.gov.za

- Thijs, A., & Van den Akker, J. (2009). Curriculum in development. Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development. https://fji.oer4pacific.org/id/eprint/183

- Umalusi (2015). Senior Phase: International Benchmarking of the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) with respective international qualifications (pp. 1–44). Umalusi Council of Quality Assurance in General and Further Education and Training.

- United Nations (2020). Formulating a National Entrepreneurship Strategy. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). https://unctad.org/topic/enterprise-development/entrepreneurship-policy-hub/1-Entrepreneurship-Strategy

- Val, E., Gonzalez, I., Iriarte, I., Beitia, A., Lasa, G., & Elkoro, M. (2017). A design thinking approach to introduce entrepreneurship education in European school curricula. The Design Journal, 20(1), S754–S766. http://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1353022

- Vandeleur, S. (2010). Indigenous technology and culture in the technology curriculum: Starting the conversation. A case study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Rhodes University, South Africa.

- Van der Walt, J. (2020). Interpretivism–constructivism as a research method in the humanities and social sciences – More to it than meets the eye. International Journal of Philosophy and Theology, 8(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v8n1a5

- Walmsey, A., & Wraae, B. 2022. Entrepreneurship education but not as we know it: Reflections on the relationship between critical pedagogy and entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(3), 1472–8117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100726

- Wiek, A., Xiong, A., Brundiers, K., & Van der Leeuw, S. (2014). Integrating problem- and project-based learning into sustainability programs. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 15(4), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-02-2013-0013