Abstract

The study of wounds in live cattle and carcass bruises can be used as welfare indicators at pre-slaughter stages (farm and transport). The knowledge about the aetiology for both wounds and bruises may develop strategies to reduce its prevalence, improve cattle welfare and decrease the economic losses related to partial condemnations. The current work assesses the presence of bruises in cattle carcasses. A total of 236 (51.08%) out of 462 cattle displayed bruises. Most bruises were small (46%), circular (26.8%)/irregular (48.9%), haemorrhagic (63.6%) and superficial (81.1%). The occurrence of bruises was influenced (p < .01) by sex, age, breed, production (beef or dairy), body condition score, cleanliness, sex at lairage pens and lairage time. Transport time and distance influenced neither wounds nor bruises (p > .05). From a practical point of view, the results of the current work highlight the role of farmers, personnel involved in cattle transport and slaughterhouse staff to control and optimise cattle welfare to decrease the occurrence of bruises. Because most bruising resulted from recent events, management measures, such as keeping cattle of the same sex, age, and body condition score in lairage pens, may decrease the occurrence and further economic losses associated with partial condemnations.

Occurrence of bruised carcass in cattle was over 50%.

Most bruises were small, circular/irregular, superficial and recent.

Sex and age were the largest risk factors of bruised carcasses.

Assessment of carcass bruises can be used as a welfare indicator.

HIGHLIGHTS

Introduction

A bruise can be defined as a lesion where tissues are crushed with a rupture of the vascular supply and an accumulation of blood and serum without discontinuity of the skin (Anderson and Horder Citation1979; INN Citation2002). Also, bruises present in the carcass are indicative of inadequate management of cattle and are used as an indicator of animal welfare (Romero et al. Citation2013). Bruises are usually caused by impact with blunt objects such as sticks, horns of other animals, farm structures or trucks structures among others (Mendonça et al. Citation2018). They can usually occur at different farm operations through movement to different areas of the farm (e.g. pushing, pressing), loading and unloading operations of animal transportation, resting in pens at the slaughterhouse or even during stunning in the slaughterhouse (Miranda-de la Lama et al. Citation2012).

Bruises do not seem to represent a microbiological hazard (Gill and Penney Citation1979) but they are still condemned by official veterinary inspectors as defined by law (European Union Citation2017). In addition, bruises are considered risk factors for quality problems in the meat carcass (i.e. dark-firm-dry meat) (Huertas et al. Citation2015). In cattle, some risk factors for bruising have been described in the literature, such as breed, age, sex, body condition score, handling of animals, geographical origin and slaughterhouse characteristics or transport conditions (Hoffman et al. Citation1998; Strappini et al. Citation2010; Romero et al. Citation2012; Huertas et al. Citation2015; Mendonça et al. Citation2018; Bethancourt-Garcia et al. Citation2019). Research about bruises in cattle carcasses has been carried out mainly in countries of North and South America (Mendonça et al. Citation2018; Bethancourt-Garcia et al. Citation2019). Since scarce information is available on the situation in the European Union, further research is necessary because some cattle production and management conditions are not comparable with those in other geographical areas. Thus, the objective of the present study was to assess the occurrence and risk factors of bruises in cattle carcasses in northern Portugal.

Materials and methods

Abattoir handling, slaughter practices and data collection

The present work evaluates the characterisation of bruises in cattle carcasses in a slaughterhouse located in the northern region of Portugal. The cattle were transported to the slaughterhouse in livestock trucks (approved by the national veterinary authority) for cattle transport. Due to the proximity of the farms to the slaughterhouse, most trucks are small (capacity of 3–4 adult cattle). The cattle that come from more distant localities arrive at the slaughterhouse in trucks of greater capacity (about 15 adult cattle). Unloading operations are made via the tailgate onto a slightly inclined concrete ramp. The cattle are then moved along a passageway into a lairage pen or slaughtered directly. The cattle rested in pens were required to negotiate a slight corner to enter the race from the holding pen. The race was about 15 m and straight, with a non-slip concrete floor and adequate illumination. Cattle were moved by batches from the race to the stunning box. The movement of cattle from the unloading to the pens and later (or directly) to the stunning box was not carried out with the use of electric prods. Once inside the stunning box, stunning (verified by veterinary meat inspector) is performed using a penetrating captive bolt.

Four hundred sixty-two carcasses were randomly selected in an observational study from September to March 2020. Data regarding eartag, sex, age, production (beef or dairy), breed and body condition score (BCS) were registered. Data related to cattle transport (distance and time) and slaughterhouse management (lairage time, cattle distribution in pens by sex and cleanliness) were recorded, respectively.

Evaluation of post mortem carcass bruises

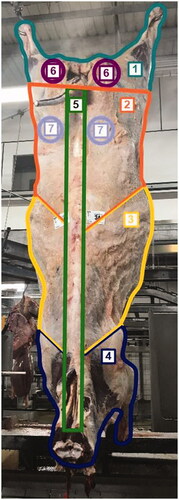

The identification and characterisation of bruises in cattle carcasses were recorded with the help of the official veterinary team, all of them with more than 15 years of experience in meat inspection. Carcass bruises were observed after the dehiding and before carcass-splitting along the slaughter-line, to observe the entire carcass easily. To evaluate the carcass bruises, the Australian Carcass Bruising Scoring System protocol (Anderson and Horder Citation1979) and the Chilean bruising carcass-grading standard (INN Citation2002) was adopted. For each carcass, the presence of bruises (yes or no) was recorded. If bruises were present, the number of bruises per entire carcass and the number of bruises at each carcass location were recorded according to the bruise scoring sheet as presented in Figure .

Figure 1. Location of carcass bruises. (1) Lateral side of thehind leg, (2) abdominal wall, (3) thoracic wall, (4) front leg, (5) loin, (6) Tuber ischiadicum and its muscular insertions, (7) Tuber coxae and its muscular insertions.

The evaluation of the body condition score was carried out based on the 1–5 point scale as defined in the literature (Klopčič et al. Citation2011) with some modifications. Briefly, the body condition score was classified into 3 categories. ‘thin’ category includes the 1st and 2nd scores, the ‘normal’ category includes the 3rd score and the ‘fat’ category included the 4th and 5th scores. The cleanliness of cattle arrived at the slaughterhouse was assessed according to the Red Meat Safety & Clean Livestock scheme (RMSC Citation2002) of the Food Standards Agency with some modifications. Summarily, cattle cleanliness was classified into 3 categories. The first and second categories proposed in the study correspond to the RMCL categories of 1st and 2nd, while 3rd category proposed corresponded to categories RMCL 3–5.

Then, data about bruise size, shape, colour and severity of each bruise presented in the carcass were registered as follows: (i) size (in cm): T1: ≥2 < 8; T2: ≥8 < 16; T3: ≥16; (ii) shape: irregular, circular or linear; (iii) colour: I1: red (indicates a recent bruise); I2: dark red or bluish (indicates an old bruise); I3: yellowish/orange/greenish (indicates very old bruise); (iv) Severity: P1: only subcutaneous tissue affected; P2: subcutaneous and muscle tissue affected; P3: subcutaneous and muscle tissue affected with fractures.

Data analysis

All data were entered into an SPSS 19.0 database (SPSS, IBM, New York, USA). The influence of sex, distribution of cattle by sex at lairage pens, breed, production (beef or dairy), body condition score, cleanliness of live cattle, transport duration and time of rest in pens on the occurrence of bruises were assessed by Chi-squared test (χ2). Statistical significance was set at p < .05. Risk factors of bruised carcasses were assessed by logistic regression. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to model the odds ratio (OR) and the confidence interval (C.I. 95%) of having more knowledge related to the variables.

Results and discussion

The study of carcass bruises can be used as welfare indicators at pre-slaughter stages (farm and transport) (Losada-Espinosa et al. Citation2018). Knowledge about the aetiology of bruises may develop strategies to reduce their prevalence, improve cattle welfare and decrease the economic losses related to partial condemnations (Mendonça et al. Citation2018). Thus, according to the best knowledge of the authors, this is the first report that evaluates the characteristics and risk factors of bruises in cattle carcasses in northern Portugal.

The current work studied the occurrence of bruised carcass in 462 cattle after dressing. Data regarding cattle characteristics are presented in Table . The cattle population studied consisted, on average, of females of Holstein–Friesian breed intended for milk production in which 236 (51.08%) cattle out of 462 presented at least one bruise. According to the total number of bruises per carcass, 107 (45.33%) presented 1 bruise; 85 (36.02%) presented 2 bruises; 29 (12.29%) presented 3 bruises; 13 (5.51%) presented 4 bruises and only 2 (0.85%) carcasses displayed 5 bruises. By carcass side, a total of 189, 177 and 47 bruises were observed in the left, right and spine respectively. Bruises were observed in all carcass locations under study with special relevance of site number 6 (Tuber ischiadicum and its muscular insertions), 7 (Tuber coxae and its muscular insertions) and 5 (loin), accounted 56.17%, 14.77% and 11.38% of the total of carcass bruises respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of cattle under study.

Most research reported a higher prevalence of bruises in carcasses than the results of this study (Miranda-de la Lama et al. Citation2012; Strappini et al. Citation2012; Huertas et al. Citation2015; Youngers et al. Citation2017) although others research displayed lower occurrence values (Strappini et al. Citation2010). These differences may be associated with factors such as the bruise record scheme used, observers’ experience, its location or speed of the slaughter line. In addition, these results must be carefully observed since factors such as small sample size (preliminary study) or regional characteristics such as beef cattle management at the farm or autochthonous breeds may be difficult to compare with previous reports. Regarding regional characteristics, most of the dairy cattle of Portugal are located in the area under study. However, beef production in northern Portugal is characterised by specific beef cattle production characterised by the existence of thousands of small-sized farms (usually family micro-farms) composed of 1 or 2 steers that are raised up to 9–10 months-old for home consumption (Avillez et al. Citation1998).

According to the characteristics of bruises, 197 were classified as small, 182 as medium and 34 as large. Regarding the shape, 115 were circular, 210 were irregular and 48 were linear. The study of the age of bruises indicated that 273 were considered as I1, 100 as I2 and 40 as I3. Based on the bruise depth, 348 were classified as P1, 64 as P2 and only 1 was associated with a fracture (P3). These results indicate most bruises are small-sized, superficial and circular and/or irregular in shape (Strappini et al. Citation2009, Citation2012) and are mainly located in the topside round, rumploin, sirloin and dorsal midline in accordance with other reports (Huertas et al. Citation2015; Youngers et al. Citation2017). Because the occurrence of lineal bruises (usually associated with hits by sticks) were scarce, the results suggest there was proper handling of cattle during the pre-slaughter operations.

Regarding bruise age, most of them were red as previously reported (Knock and Carroll Citation2019) indicating that they were sustained recently. Therefore, other research (Strappini et al. Citation2013) reported that almost 70% of bruises in dairy cattle assessed at post-mortem inspection could be traced back to events encountered at the abattoir with about 40% of bruising sustained in the hour prior to slaughter. Our results regarding colour (bruise age) together with the size and depth suggest recent events. The fact that more bruises displayed a circular or irregular shape along with the recent red colour, suggests that bruises are likely related to handling at the slaughterhouse (Strappini et al. Citation2013).

However, it is important to remark that the association of bruise age with any specific stage of production is difficult since there are no criteria that define the time period of ‘recent’.

The study of bruised carcasses according to the characteristics of the cattle and their management (Tables and ) revealed that the factors studied (sex, distribution of cattle in pens by sex, breed, intended production, body condition score, cleanliness and rest time at pens) influenced the number of bruises in carcasses (p < .001).

Table 2. Number of cattle carcasses with at least one bruise.

Table 3. Evaluation of carcass bruises by logistic regression.

The high occurrence of bruises observed in female cattle, according to what has been reported in the literature (Strappini et al. Citation2010; Mendonça et al. Citation2018; Bethancourt-Garcia et al. Citation2019), can be associated with the high proportion of sample females. However, some hormonal interference in the behaviour has been suggested (Riley et al. Citation2014). Regarding the age of cattle, the lower occurrence of bruises in the youngest cattle could be associated with the type of management of the area under study, in which steers are usually raised isolated. Other authors indicated that the presence of bruises is related to acquired life experience (Hoffman and Lühl Citation2012; Šímová et al. Citation2016). Thus, it may explain the lower prevalence of bruises observed in beef cattle since they are usually raised under extensive management. The presence of horns has been associated with a higher carcass bruise occurrence (Mendonça et al. Citation2016; Youngers et al. Citation2017). However, contrary results were observed in this study in which Portuguese autochthonous cattle are characterised by the presence of large horns.

The body condition score was revealed as an important factor regarding the presence of bruises in carcasses (Sánchez-Hidalgo et al. Citation2019) in relation to a lower fat coverage (Strappini et al. Citation2010) Thus, the worse the body condition score, the higher the number of carcass bruises. Furthermore, carcass from cattle classified as thin presented at least 2 bruises per carcass.

The higher odds of bruises in dirty cattle observed are also in accordance as reported (Knock and Carroll Citation2019) suggesting deficient welfare conditions on the farm. However, the fact that most bruises are classified as recent events (and not related to pre-slaughter events), the association of cleanliness at ante mortem inspection and carcass bruises could be related to the transportation throughout curvy roads where cattle fall or bump against trailer surfaces during transport getting dirty. Because most cattle are slaughter rapidly after arrival at the slaughterhouse, it may explain the higher odds of dirty animals in cattle in which bruises are mainly classified as recent events.

Although it was not studied, poor body condition score, lack of cleanliness and high occurrence of bruises have been associated with the existence of previous health problems such as mastitis or laminitis (Sánchez-Hidalgo et al. Citation2019).

Transport has been referred to as a risk factor of bruised carcasses (Huertas et al. Citation2018). The absence of a relationship between transport and bruises (p > .05), contrary to as reported in most studies, may be associated with regional cattle management and the small sample studied. Cattle from livestock markets are more bruised associated with multiple loading and unloading operations (Strappini et al. Citation2012). However, most of the farms in this study are near the slaughterhouse, and the cattle are loaded onto the farm and transported and unloaded directly to the slaughterhouse. Furthermore, this may explain this lack of influence of transport time in this study, supporting the previous results (shape and colour) in which bruises detected are probably due to handling at slaughterhouse.

In addition, other research (Huertas et al. Citation2015) concluded that the high occurrence of bruises could be associated with the lack of trained personnel and the lack of maintenance of the trucks. Thus, the set of factors previously described (proximity to the slaughterhouse, short travel time, low number of loads and unloads or low heads number in trucks) together with the compulsory training of drivers and certification of livestock transport vehicles by the veterinary national authority could also explain the results. Also, the low rate of bruising in carcasses subjected to a long journey could be associated with animal transport companies with experienced drivers as suggested by other authors (Bethancourt-Garcia et al. Citation2019).

At the slaughterhouse, it was observed that cattle of the same sex that rested in pens were more likely to present bruises in carcasses than those in mixed pens. Mixing cattle of different farms, age and sex is a common practice in transport and lairage that may lead to increased stress due to changes in the environment and in the individual hierarchy (Warriss Citation1990). Thus, the increase in social interaction and hierarchical behaviours could explain the high occurrence of bruises in cattle of same-sex in pens.

Conclusions

The study and characterisation of bruises in cattle carcasses is an important indicator to assess welfare during pre-slaughter stages and farm management. The results of the current work in the sample of cattle studied indicated an occurrence of bruises over 50%. Most bruises are characterised by small size, circular or irregular shape and haemorrhagic. The low occurrence observed in comparison with other reports indicates adequate cattle management in pre-slaughter operations such as loading, transport and unloading at the slaughterhouse. The main characteristics of the cattle that influenced the presence of bruised carcasses were sex, age, breed and body condition score. Regarding management, cleanliness, lairage time and keep cattle of same-sex in pens also influenced the occurrence of bruises.

Risk factors that increased the likelihood of bruised carcasses were sex (female), age (over 1 year-old), poor body condition and lack of cleanliness. Despite the fact that the transport of cattle to the slaughterhouse is described as a risk factor for bruised carcasses, the present work displayed contrary results. This is probably associated with the management of cattle in the study area, the close location of the farms to the slaughterhouse and the small sample size.

From a practical point of view, the results of the current work highlight the role of farmers, drivers and slaughterhouse staff in order to control the welfare of cattle to decrease the occurrence of bruises.

Since most of the bruises were considered as recent events, it suggests that they are related to handling in the slaughterhouse. The fact that most bruises are circular may be indicative that slaughterhouse staff moves cattle from pens to the stunning room quickly to increase the number of cattle slaughtered per day. This suggests that if cattle were handled with care and patience, the bruising rate could decrease, increasing the economic benefit due to less partial condemnations. In addition, some management measures such as keeping cattle of different sex, similar age, and similar body condition score in pens may decrease the occurrence and greater economic losses associated with partial condemnations.

It is important to remark some limitations of the present study, such as the small sample size, the regional characteristics of cattle management, the existence of previous health issues or the number of previous movements among farms/markets that can influence the occurrence of bruises.

Ethical approval

The present manuscript does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Author contributions

A.E. designed the work, P.T.-T carried out the sample collection, P.T.-T and A.E. performed the laboratorial analysis, J.G.-D. carried out the statistical analysis, J.G.-D. wrote the manuscript, J.G.-D. and A.E. proofread the manuscript provided critical feedback in shaping the research and manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Juan García-Díez), upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson B, Horder JC. 1979. The Australian Carcass Bruise Scoring System [visual appraisal of damage]. Queensland Agri J. 105:281–287.

- Avillez F, Jorge M, Trindade JJC, Ferreira H, Costa J. 1998. In: Monke E, Avillez F, Pearson S. Editors. Small farm agriculture in Southern Europe: CAP reform and structural change. London (UK): Routledge; p. 31–64.

- Bethancourt-Garcia JA, Vaz RZ, Vaz FN, Silva WB, Pascoal LL, Mendonça FS, Vara CC, Nuñez AJC, Restle J. 2019. Pre-slaughter factors affecting the incidence of severe bruising in cattle carcasses. Livest Sci. 222:41–48.

- European Union. 2017. Regulation 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on official controls and other official activities performed to ensure the application of food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection products, amending Regulations (EC) No 999/2001, (EC) No 396/2005, (EC) No 1069/2009, (EC) No 1107/2009, (EU) No 1151/2012, (EU) No 652/2014, (EU) 2016/429 and (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Council Regulations (EC) No 1/2005 and (EC) No 1099/2009 and Council Directives 98/58/EC, 1999/74/EC, 2007/43/EC, 2008/119/EC and 2008/120/EC, and repealing Regulations (EC) No 854/2004 and (EC) No 882/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Council Directives 89/608/EEC, 89/662/EEC, 90/425/EEC, 91/496/EEC, 96/23/EC, 96/93/EC and 97/78/EC and Council Decision 92/438/EEC. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/625/oj.

- Gill CO, Penney N. 1979. Microbiology of bruised tissue. Appl Environ Microbiol. 38(6):1184–1185.

- Hoffman LC, Lühl J. 2012. Causes of cattle bruising during handling and transport in Namibia. Meat Sci. 92(2):115–124.

- Hoffman DE, Spire MF, Schwenke JR, Unruh JA. 1998. Effect of source of cattle and distance transported to a commercial slaughter facility on carcass bruises in mature beef cows. J Am Vet Med Ass. 212:668–672.

- Huertas S, Kempener R, van Eerdenburg F. 2018. Relationship between methods of loading and unloading, carcass bruising, and animal welfare in the transportation of extensively reared beef cattle. Animals. 8(7):119.

- Huertas SM, van Eerdenburg F, Gil A, Piaggio J. 2015. Prevalence of carcass bruises as an indicator of welfare in beef cattle and the relation to the economic impact. Vet Med Sci. 1(1):9–15.

- INN - Instituto Nacional de Normalización. 2002. Norma Chilena Oficial NCh. 1306. Canales de bovino - Definiciones y tipificación. Chile https://ecommerce.inn.cl/nch1306200244552 (Access on 21/07/2021)

- Klopčič M, Hamoen A, Bewley J. 2011. Body condition scoring of dairy cows. Domžale (Slovenia): University of Ljubljana.

- Knock M, Carroll GA. 2019. The potential of post-mortem carcass assessments in reflecting the welfare of beef and dairy cattle. Animals. 9(11):959.

- Losada-Espinosa N, Villarroel M, María GA, Miranda-de la Lama GC. 2018. Pre-slaughter cattle welfare indicators for use in commercial abattoirs with voluntary monitoring systems: a systematic review. Meat Sci. 138:34–48.

- Mendonça FS, Vaz RZ, Cardoso FF, Restle J, Vaz FN, Pascoal LL, Reimann FA, Boligon AA. 2018. Pre-slaughtering factors related to bruises on cattle carcasses. Anim Prod Sci. 58(2):385–392.

- Mendonça FS, Vaz RZ, Leal WS, Restle J, Pascoal LL, Vaz MB, Farias GD. 2016. Genetic group and horns presence in bruises and economic losses in cattle carcasses. SCA. 37(6):4265–4273.

- Miranda-de la Lama GC, Leyva IG, Barreras-Serrano A, Pérez-Linares C, Sánchez-López E, María GA, Figueroa-Saavedra F. 2012. Assessment of cattle welfare at a commercial slaughter plant in the northwest of Mexico. Trop Anim Health Prod. 44(3):497–504.

- Riley DG, Gill CA, Herring AD, Riggs PK, Sawyer JE, Lunt DK, Sanders JO. 2014. Genetic evaluation of aspects of temperament in Nellore–Angus calves. J Animal Sci. 92(8):3223–3230.

- RMSC. 2002. Red meat safety & clean livestock. London (UK): Food Standards Agency; [accessed 2021 April 10]. https://www.foodstandards.gov.scot/downloads/Red_meat_safety_and_clean_livestock.pdf

- Romero MH, Gutiérrez C, Sánchez JA. 2012. Evaluation of bruises as an animal welfare indicator during pre-slaughter of beef cattle. Rev Col Cien Pec. 25:267–275.

- Romero MH, Uribe-Velásquez LF, Sánchez JA, Miranda-de La Lama GC. 2013. Risk factors influencing bruising and high muscle pH in Colombian cattle carcasses due to transport and pre-slaughter operations. Meat Sci. 95(2):256–263.

- Sánchez-Hidalgo M, Rosenfeld C, Gallo C. 2019. Associations between pre-slaughter and post-slaughter indicators of animal welfare in cull cows. Animals. 9(9):642.

- Šímová V, Večerek V, Passantino A, Voslářová E. 2016. Pre-transport factors affecting the welfare of cattle during road transport for slaughter–a review. Acta Vet Brno. 85(3):303–318.

- Strappini AC, Frankena K, Metz JHM, Gallo B, Kemp B. 2010. Prevalence and risk factors for bruises in Chilean bovine carcasses. Meat Sci. 86(3):859–864.

- Strappini AC, Frankena K, Metz JHM, Gallo C, Kemp B. 2012. Characteristics of bruises in carcasses of cows sourced from farms or from livestock markets. Animal. 6(3):502–509.

- Strappini AC, Metz JHM, Gallo C, Frankena K, Vargas R, De Freslon I, Kemp B. 2013. Bruises in culled cows: when, where and how are they inflicted? Animal. 7(3):485–491.

- Strappini AC, Metz JHM, Gallo CB, Kemp B. 2009. Origin and assessment of bruises in beef cattle at slaughter. Animal. 3(5):728–736.

- Warriss PD. 1990. The handling of cattle pre-slaughter and its effects on carcass and meat quality. Appl an Behaviour Sci. 28(1–2):171–186.

- Youngers ME, Thomson DU, Schwandt EF, Simroth JC, Bartle SJ, Siemens MG, Reinhardt CD. 2017. Case study: prevalence of horns and bruising in feedlot cattle at slaughter. Prof Animal Sci. 33:35–139.