ABSTRACT

Objective: A Delphi study was conducted to develop guidelines on considerations when providing sensitive and appropriate mental health first aid to a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer or questioning (LGBTIQ) person. These can be used in conjunction with existing guidelines when assisting a person who might be experiencing a mental health problem or crisis.

Methods: A systematic search of websites, books and journal articles was conducted to develop a questionnaire containing items about the knowledge, skills and actions needed for assisting an LGBTIQ person who is experiencing mental health problems. These items were rated over three survey rounds by an expert panel according to whether they should be included in the guidelines.

Results: Seventy-five mental health professionals who were part of the LGBTIQ community or who treated people from the LGBTIQ community participated in the study. Of the 209 items that were rated over the 3 rounds, 164 items were endorsed by at least 80% of panel members. These items formed the basis of the guidelines document that outlines what a person needs to consider when providing mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person with mental health problems.

Conclusion: This research highlighted the complexity of supporting an LGBTIQ person with mental health problems, but also provided specific advice on how to address these complexities. It is hoped that these guidelines will increase support, and decrease stigma and discrimination towards LGBTIQ people who are experiencing mental health problems. More specifically, the guidelines will be used to supplement the content of Mental Health First Aid training courses.

Abbreviations: LGBTIQ: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer or questioning; MHFA: mental health first aid

Background

People from the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex or queer (LGBTIQ)Footnote1 community (see for the definitions used in this research) are at a higher risk for mental health problems than their non-LGBTIQ peers (Corboz et al., Citation2008; King et al., Citation2008; Leonard et al., Citation2012; Skerrett, Kõlves, & De Leo, Citation2015). Gay men and lesbian women score higher on scales measuring psychological distress (King et al., Citation2003; Leonard et al., Citation2012) and experience higher prevalence of mood, anxiety and substance use disorders (Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, Citation2003) compared to heterosexual men and women. According to the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2008), lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) people (compared to heterosexual people) have a higher 12-month prevalence of affective disorders (19% vs. 6%), anxiety disorders (32% vs. 14%) and substance use disorders (9% vs. 5%). In an Australian study, bisexual participants had significantly higher depressive symptom scores than gay or lesbian participants, who had higher depression symptom scores than the heterosexual participants (Jorm, Korten, Rodgers, Jacomb, & Christensen, Citation2002). In addition, drug and alcohol misuse is 1.5 times more common in LGB people (King et al., Citation2008).

Table 1. Definitions used in this research.

There is less research investigating mental health problems in transgender and intersex people. Australian research indicates that 53% of transgender participants meet the diagnostic criteria for depression and 36–44% experience clinically relevant symptoms of depression. Eighteen per cent meet the criteria for a panic disorder and 17% for another anxiety disorder (Couch et al., Citation2007; Hyde et al., Citation2014). This rate of depression is higher than in another study of cisgender individuals from the gay and lesbian community, where 24% of the sample reported experiencing symptoms of depression in the last two weeks (Couch et al., Citation2007; Pitts, Mitchell, Smith, & Patel, Citation2006).

It is estimated that 1.7% of the population experience an intersex variation (Blackless et al., Citation2000). The methodology and results from research investigating mental health problems in people with an intersex variation vary greatly from study to study, rendering any conclusions about the mental health of people with intersex variation problematic (Wisniewski & Mazur, Citation2009). However, there is some indication that psychological distress has a significant impact on this population (D’Alberton et al., Citation2015).

Suicidal thoughts and behaviours and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) are also a concern within the LGBTIQ community. The level of suicidal ideation among Australian LGBT people is high, with 21–25% of transgender (Couch et al., Citation2007; Hyde et al., Citation2014) and 16% of gay, lesbian and bisexual (Pitts et al., Citation2006) people reporting suicidal ideation in the previous two weeks. Research indicates there may also be an increased risk of NSSI among LGBTIQ communities (King et al., Citation2008; Suicide Prevention Australia, Citation2009). An Australian intersex study (Jones et al., Citation2016) found that, of the participants who answered questions about mental health, 42% had thought about and 26% had engaged in NSSI due to issues related to having an intersex variation. In addition, 60% had thought about and 19% had attempted suicide due to issues related to having an intersex variation.

Two longitudinal studies of LGBTIQ young people found a positive relationship between victimisation (threats, insults and abuse) and poor mental health outcomes, and that social support negatively correlated with these outcomes, including suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Birkett, Newcomb, & Mustanski, Citation2015; Hillier et al., Citation2010). Therefore, reducing the stigma that can lead to victimisation and increasing the support given to an LGBTIQ person may help to improve their mental health (Crisp & McCave, Citation2007).

Given the above findings, it is important to have public health interventions that address the risk of mental health problems in the LGBTIQ population. One such intervention is ‘mental health first aid’, which has been defined by Kitchener, Jorm, and Kelly (Citation2015, p. 12) as:

The help offered to a person developing a mental health problem, experiencing a worsening of an existing mental health problem or in a mental health crisis. The first aid is given until appropriate professional help is received or until the crisis resolves.

The Mental Health First Aid course has been extensively evaluated and found to increase mental health literacy, decrease stigmatising attitudes and increase supportive behaviours towards people with mental health problems (Hadlaczky, Hökby, Mkrtchian, Carli, & Wasserman, Citation2014).

Offering sensitive and appropriate mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person requires additional knowledge and skills to those provided in a standard Mental Health First Aid course, including understanding common challenges that LGBTIQ people face, understanding and using appropriate terminology, and knowing about specific community resources for LGBTIQ people with mental health problems (Crisp & McCave, Citation2007). The aim of this study was to develop a set of guidelines on considerations on how best to provide sensitive and appropriate mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person. These guidelines could then be used to supplement information in the Mental Health First Aid course or in conjunction with existing freely available guidelines on how to assist people with specific mental health problems or crises.

Methods

The Delphi research method (Dalkey, Citation1996; Jorm, Citation2015) is an expert consensus method that is used to develop best practice guidelines using practice-based evidence. Development of the current guidelines followed the protocol of similar Delphi studies (e.g. Bond, Chalmers, Jorm, Kitchener, & Reavley, Citation2015; Bond et al., Citation2016) and involved four steps: (1) expert panel formation, (2) literature search and survey development, (3) data collection and analysis and (4) guidelines development.

Step 1: Panel formation

This research involved recruiting an expert panel of professionals in the field of LGBTIQ mental health. A panel of 20 or more members generally produces stable results in a Delphi study (Jorm, Citation2015). Therefore, the aim was to recruit a minimum of 30 people, to allow for participant attrition over the course of the study. In previous similar Delphi studies, three types of expert panels were used – people with a lived experience, carers and mental health professionals. In this study, it was thought that it might be difficult to recruit enough panel members for these three different types of expert panels. Therefore, it was decided to recruit only an expert panel of professionals, while also assessing whether members of this panel had lived experience of a mental illness or were carers of someone from the LGBTIQ community.

Panel members had to be 18 years or over, and a mental health professional, support worker or a mental health educator. They also had to:

Work with LGBTIQ people

OR

Be a member of the LGBTIQ community

OR

Be a close family member of someone from the LGBTIQ community.

Panel members were recruited by sending advertising flyers to Mental Health First Aid Australian and international networks, Australian and international English-speaking LGBTIQ support groups, and MindOut’s network of LGBTIQ organisations. (MindOut is an Australian national LGBTI mental health and suicide prevention initiative of the National LGBTI Health Alliance.)

Step 2: Literature search and survey development

In order to inform the content of the initial survey, a systematic search of both the ‘grey’ and academic literature was conducted in January and February 2015 to gather statements about how to sensitively and appropriately help an LGBTIQ person with mental health problems. The ‘grey’ literature search was conducted using Google Australia, Google UK, Google USA and Google Books. The key search terms were communication guidelines LGBTIQ, assumptions about LGBTIQ people, LGBTIQ treatment barriers help seeking, (help OR support) someone to come out, (help OR support) someone questioning sexuality or gender. The academic literature search was conducted using PubMed and PsycINFO databases. Search terms for the academic literature search were (gay OR lesbian OR bisexual OR trans* OR intersex) AND (‘mental illness’ OR ‘mental health problem’) AND (help* OR assist* OR guideline OR ‘first aid’).

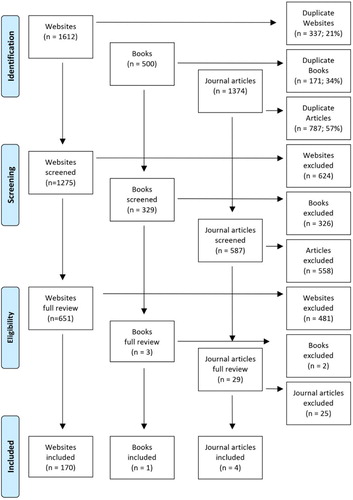

Based on previous similar Delphi studies (e.g. Langlands et al., Citation2008a), the first 50 websites, books and journal articles for each search term were retrieved and reviewed for relevant information, after duplicates were excluded. The decision to only examine the first 50 websites, books and journal articles for each search term is based on previous Delphi studies that found that the quality of the resources declined rapidly after the first 50 (Kelly, Jorm, Kitchener, & Langlands, Citation2008). Steps were taken to minimise the influence of Google’s searching algorithms at the time of the search, including: clearing the search history in Google’s settings to minimise the influence of past searches, signing out of any Google profiles to minimise any targeted search results or advertising based on the demographic data of the author responsible for conducting the search, disabling any location features that would influence results based on geographic location and ensuring that ‘Any country’ was deselected from the search result settings so that only local ‘Pages from [country]’ results were shown. Any links appearing on the websites were also reviewed. Websites, articles and books were excluded if they did not address mental health problems or distress, did not address LGBTIQ issues specifically or were clinical in focus with no relevance to a member of the public in a first aid situation. The content of 170 websites, one book and four journal articles was analysed to develop the Round 1 survey. summarises the results of the literature search.

A working group, consisting of staff from Mental Health First Aid Australia and the University of Melbourne, translated the relevant information from the literature search into helping statements that were clear, actionable and contained only one idea. The statements were used to form the Round 1 survey that was administered to the expert panel via SurveyMonkey. The panel members were asked to rate each of the helping statements, using a 5-point scale (‘essential’, ‘important’, ‘don’t know/depends’, ‘unimportant’ or ‘should not be included’), according to whether or not they thought the statement should be included in the guidelines.

Step 3: Data collection and analysis

Data were collected in three survey rounds administered between September 2015 and January 2016. In Round 1, panel members completed the survey developed using the literature search, and also had the opportunity to provide qualitative data in the form of comments or suggestions for new helping statements.

After panel members completed a survey round, the statements were categorised as follows:

Endorsed. The item received an ‘essential’ or ‘important’ rating from 80% to 100% of members of the panel.

Re-rate. The item received an ‘essential’ or ‘important’ rating from 70% to 79% of panel members.

Rejected. The item did not fall into either the endorsed or re-rate categories.

Panel members’ comments were thematically analysed and the working group created new items from these comments to cover helping ideas that were not included in the first survey. This new content was translated into clear and actionable statements for the Round 2 survey.

Panel members were given a summary report of Round 1 that included a list of the items that were endorsed and rejected, as well as the items that were to be re-rated in Round 2. The report included the panel percentages of each rating, as well as the panel member’s individual scores for each item to be re-rated. This allowed the panel members to compare their ratings with each expert panel’s consensus rating and consider whether to maintain or change their answer when re-rating an item in the next round.

The procedures for Rounds 2 and 3 were the same as described above, with several exceptions. Round 2 included new items from the Round 1 comments, as well as items to be re-rated. There was no opportunity for comments in Round 2 or Round 3, and if a re-rated item did not receive an ‘essential’ or ‘important’ rating by 80% or more panel members, it was rejected. Round 3 consisted of any new items in Round 2 that needed to be re-rated, according to the above criteria.

Step 4: Guidelines development

All of the endorsed statements were written, by the first author, into the guidelines document. This was done by grouping similar items and re-writing them into continuous prose for ease of reading. Where possible, statements were combined and repetition was deleted. Original wording of the items was retained as much as possible. Some items were given examples and explanatory notes to clarify the advice. The working group reviewed this draft to ensure that the structure and the language were appropriate for the target audience of the guidelines. The draft guidelines were then given to panel members for final comment, feedback and endorsement.

Ethics, consent and permissions

This research was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Ethics Committee. Informed consent, including permission to report individual participant’s de-identified data, was obtained from all participants by clicking ‘yes’ to a question about informed consent in the Round 1 survey.

Results

Complete data for all three rounds of the survey were collected from 75 panellists (mean age = 44; SD = 12; range = 18–66). Panellists were from Australia (n = 67), U.S.A (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 2), UK (n = 2) and Ireland (n = 1). See for the characteristics of the panellists and for the retention rates across the three rounds.

Table 2. Characteristics of panellists who completed all three rounds.

Table 3. Retention rates across all three rounds.

A total of 209 items were rated over the 3 rounds to yield a total of 164 endorsed items and 45 rejected items. presents the information about the total number of items rated, endorsed and rejected over the three rounds.

The endorsed items formed the basis of the guidelines document entitled Considerations when providing mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person, available from www.mhfa.com.au/resources/mental-health-first-aid-guidelines (Mental Health First Aid Australia, Citation2016). The main themes and subthemes of the guidelines are:

Understanding LGBTIQ experiences – this section explains the concepts of sexuality and gender and outlines the assumptions that the first aider should avoid, for example, assumptions about a person’s gender or sexuality based on the way they dress or act.

Mental health problems in LGBTIQ people – this section considers the risk factors for mental health problems that are specific to LGBTIQ people and the relationship between LGBTIQ experiences and mental health problems.

Talking with an LGBTIQ person – this section highlights the importance of using appropriate, non-stigmatising language when supporting an LGBTIQ person, including the use of gendered and non-gendered pronouns. It outlines how to talk and ask questions about LGBTIQ experiences and includes a section on what to do if the first aider encounters difficulties while talking to the person.

Supporting the LGBTIQ person – this section includes advice on how to show and provide practical support to an LGBTIQ person experiencing mental health problems. It includes specific advice when the person experiences discrimination and stigma, discloses their LGBTIQ experience, ‘comes out’, or is an adolescent.

Treatment seeking for mental health problems – This section includes information about the barriers an LGBTIQ person may experience with regard to treatment seeking and some of the ways to help the person seek treatment.

The final draft of the guidelines was provided to panel members who completed all three rounds of the survey for final comments and endorsement. All panel members endorsed the guidelines without suggesting any changes.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to use the Delphi method to develop guidelines on additional considerations when providing sensitive and appropriate mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person. These guidelines for assisting an LGBTIQ person are similar in concept to other mental health first aid guidelines setting out the cultural considerations for a specific cultural group of people, for example, Aboriginal Australians (Chalmers et al., Citation2014; Hart, Jorm, Kanowski, Kelly, & Langlands, Citation2009). Specifically, the guidelines include important information that a mental health first aider needs to know about LGBTIQ experiences, and the experience of mental health problems in LGBTIQ people. They also provide guidance on appropriate actions to take in order to support an LGBTIQ person with mental health problems.

This research highlights the diversity of LGBTIQ communities and individuals, and this diversity can lead to a complexity in providing mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person. These guidelines address specific issues in providing mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person by highlighting the common assumptions people make about LGBTIQ people and their experiences, and recommending specific actions to take when supporting an LGBTIQ person with mental health problems. For example, the guidelines highlight that an LGBTIQ service may not be experienced in the particular LGBTIQ experience of the person (e.g. transgender or bisexual experience). Also, it is noted that although an LGBTIQ service may be available, the LGBTIQ person may prefer to attend an LGBTIQ-friendly, ‘mainstream’ service. Specific guidance given to the mental health first aider includes knowing the potential barriers to help-seeking and working with the LGBTIQ person to find appropriate services.

These guidelines also provide guidance on the use of appropriate language and include what actions to take in situations that are common to LGBTIQ people, for example, if the person is experiencing distress related to ‘coming out’, discrimination or stigma. They also include a section on what to do if the person is an adolescent, as many LGBTIQ people first explore their identity during adolescence.

Language and terminology

The way humans view themselves is, at least in part, a result of the interactions they have with others, and most of these interactions involve conversations (Bucholtz & Hall, Citation2005). This study highlights the importance of using appropriate, non-stigmatising language when providing support to an LGBTIQ person with mental health problems as evidenced by the endorsement of the following items: By using appropriate and inclusive language you can help the person to feel safe and comfortable about disclosing information that may be relevant to their distress AND Any attempts to get language and terminology correct are likely to be appreciated by the LGBTIQ person.

While language was acknowledged as important in these guidelines, it was also recognised by one panel member that for non-LGBTIQ people (and indeed for some LGBTIQ people) it can be difficult to ‘wrap your head around’ some of the LGBTIQ concepts and that ‘LGBTIQ people totally get this (the difficulty of understanding LGBTIQ concepts), [LGBTIQ people] are only asking [others] be aware and try to get it [right] … ’. It was also acknowledged by other panel members that language varies from group to group (e.g. nationality, age group or cultural group) and that showing care and concern is more important than getting language exactly right. For example, one panel member said, ‘I think technical language knowledge is less important than a willingness to stand alongside someone and be self-aware and respectful.’ Another said, ‘The first aider is best served by coming from a position of empathy and care and it is ok to make mistakes, just be mindful to apologise and learn from them.’ These guidelines provide practical advice on what terminology to use and to avoid, including the use of pronouns and how to ask questions appropriately. It is hoped that the guidelines will increase people’s comfort level by providing practical advice, but also acknowledging that it is okay to make mistakes and that demonstrating care and concern is most important.

Specific considerations

These guidelines also provide specific considerations a mental health first aider may have when supporting an LGBTIQ person, namely when the LGBTIQ person has experienced discrimination and stigma, and when the LGBTIQ person is an adolescent. Discrimination and stigma are experienced by a significant number of LGBTIQ people (Birkett et al., Citation2015; Hillier et al., Citation2010), and therefore, these guidelines provide information and advice on supporting an LGBTIQ person if they are experiencing mental health problems due to discrimination and stigma. The guidance given involves informing the LGBTIQ person about potential actions they can take and offering to support them if they choose to take action. The emphasis is on allowing the LGBTIQ person to make their own choices and take control of any actions they deem suitable. This approach is in line with other mental health first aid advice (Kitchener, Jorm, & Kelly, Citation2013). It is also hoped that these guidelines will increase the public’s knowledge about mental health problems in LGBTIQ people. Although not the primary goal of these guidelines, they will add to public health interventions that aim to reduce discrimination and resultant mental health problems in LGBTIQ people.

Strengths and limitations

Seventy-five experts on mental health problems in LGBTIQ people participated in this research to develop guidelines on what someone needs to consider when providing mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person. This number of panel members is higher than in other similar Delphi studies utilising one panel of experts (e.g. 28 panel members in a study to develop guidelines for supporting an Aboriginal person with mental health problems (Hart, Jorm, Kanowski, et al., Citation2009) and 37 panel members to develop guidelines for supporting an Aboriginal adolescent (Chalmers et al., Citation2014)), indicating that this is a topic of particular interest and need.

There are a few limitations to this study that are worth mentioning. First, key actions may have been omitted because panel members may have been asked to rate statements that were beyond their expertise. Furthermore, while panel members are able to provide comments in Round 1 of the survey, they were not able to discuss their comments and opinions with others. Panel members may have held biases or made incorrect assumptions that were unchallenged because there was no opportunity for discussion. Our search strategy of extracting only the first 50 websites, books and journal articles may have also been a limitation. However, steps were taken to minimise this limitation during the search. Furthermore, allowing panel members to write in missing statements minimised this limitation. Also, this is a rapidly evolving area, so some panel members may have been responding with what they felt was an ‘expert’ view, but which may have been out of date or not representative of what is current ‘best practice’. Another limitation was that there was research on the mental health of intersex people (Jones et al., Citation2016) that was released after the completion of the Round 1 survey and therefore was not included in the guidelines.

The Delphi method has historically involved the use of one expert panel, often professionals working in the area of study (Hasson, Keeney, & McKenna, Citation2000). However, recent work in the mental health field has included multiple expert panels, including consumer and carer experts, allowing for lived experience expertise to influence the development of guideline (e.g. Bond et al., Citation2015, Citation2016). This current study only utilised one expert panel – professionals. While this had the potential of excluding lived experience expertise, both the lived experience of mental health problems and LGBTIQ experiences were represented in the professional panel. For example, almost a quarter of the panel members had experienced mental health problems and 60% identified as lesbian, gay or bisexual.

Future research

Given the prevalence of mental health problems in LGBTIQ young people, research to develop guidelines for the prevention of mental health problems in LGBTIQ adolescents would be useful. Also, given that these guidelines are for English-speaking Western countries, it would be helpful to use the Delphi method to develop guidelines for specific cultural groups of LGBTIQ people, such as Indigenous peoples. Finally, any training that is developed using these guidelines should be evaluated.

Conclusion

This project used the consensus of 75 experts to develop guidelines on important considerations for providing mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person. This research highlighted the complexity of supporting an LGBTIQ person with mental health problems, but also provided specific guidance on how to address these complexities. It is hoped that these guidelines will help increase support, and decrease stigma and discrimination of LGBTIQ people who are experiencing mental health problems.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the participants who generously shared their time and expertise with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Although not traditionally included, in this article, LGBTIQ also includes people who are asexual. The initials are used individually when referring to specific groups of people, for example, LGB refers to lesbian, gay and bisexual people only.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2008). National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of results (Document 4326.0). Canberra: Author.

- Birkett, M., Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2015). Does it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(3), 280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.275

- Blackless, M., Charuvastra, A., Derryck, A., Fausto-Sterling, A., Lauzanne, K., & Lee, E. (2000). How sexually dimorphic are we? Review and synthesis. American Journal of Human Biology, 12(2), 151–166. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(200003/04)12:2<151::AID-AJHB1>3.0.CO;2-F

- Bond, K. S., Chalmers, K. J., Jorm, A. F., Kitchener, B. A., & Reavley, N. J. (2015). Assisting Australians with mental health problems and financial difficulties: A Delphi study to develop guidelines for financial counsellors, financial institution staff, mental health professionals and carers. BioMed Central Health Services Research, 15(218). doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0868-2

- Bond, K. S., Jorm, A. F., Miller, H. E., Rodda, S. N., Reavley, N. J., Kelly, C. M., & Kitchener, B. A. (2016). How a concerned family member, friend or member of the public can help someone with gambling problems: A Delphi consensus study. BioMed Central Psychology, 4(6). doi:10.1186/s40359-016-0110-y.

- Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7(4/5), 585–614. doi: 10.1177/1461445605054407

- Chalmers, K., Bond, K., Jorm, A., Kelly, C., Kitchener, B., & Williams-Tchen, A. (2014). Providing culturally appropriate mental health first aid to an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander adolescent: Development of expert consensus guidelines. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(6). doi:10.1186/1752-4458-8-6.

- Cochran, S. D., Sullivan, J. G., & Mays, V. M. (2003). Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.53

- Corboz, J., Dowsett, G., Michell, A., Couch, M. A., Agius, P., & Pitts, M. (2008). Feeling queer and blue: A review of the literature on depression and related issues among gay, lesbian, bisexual and other homosexually active people. A report from The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University, prepared for beyondblue: The national depression initiative. Melbourne: La Trobe University, Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society.

- Couch, M. A., Pitts, M. K., Patel, S., Mitchell, A. E., Mulcare, H., & Croy, S. L. (2007). TranZnation: A report on the health and wellbeing of transgender people in Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University.

- Crisp, C., & McCave, E. L. (2007). Gay affirmative practice: A model for social work practice with gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24(4), 403–421. doi: 10.1007/s10560-007-0091-z

- D’Alberton, F., Assante, M. T., Foresti, M., Balsamo, A., Bertelloni, S., Dati, E., … Mazzanti, L. (2015). Quality of life and psychological adjustment of women living with 46, XY differences of sex development. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(6), 1440–1449. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12884

- Dalkey, N. (1996). The Delphi method: An experimental study of group opinion. Santa Monica, CA: Rand.

- Hadlaczky, G., Hökby, S., Mkrtchian, A., Carli, V., & Wasserman, D. (2014). Mental health first aid is an effective public health intervention for improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour: A meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(4), 467–475. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.924910

- Hart, L., Jorm, A., Kanowski, L., Kelly, C., & Langlands, R. (2009). Mental health first aid for Indigenous Australians: Using Delphi consensus studies to develop guidelines for culturally appropriate responses to mental health problems. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 9(4). doi:10.1186/1471-244X-9-47.

- Hart, L., Jorm, A., Paxton, S., Kelly, C., & Kitchener, B. (2009). First aid for eating disorders. Eating Disorders, 17(5), 357–384. doi: 10.1080/10640260903210156

- Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 1008–1015.

- Hillier, L., Jones, T., Monagle, M., Overton, N., Gahan, L., Blackman, J., & Mitchell, A. (2010). Writing themselves in 3: The third national study on the sexual health and wellbeing of same sex attracted and gender questioning young people. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University.

- Hyde, Z., Doherty, M., Tilley, P., McCaul, K., Rooney, R., & Jancey, J. (2014). The first Australian national trans mental health study: Summary of results ( C. U. School of Public Health Ed.). Perth: Curtin University.

- Jones, T., Hart, B., Carpenter, M., Ansara, G., Leonard, W., & Lucke, J. (2016). Intersex: Stories and statistics from Australia (O. B. Publishers Ed.). Cambridge: Open Books Publishers.

- Jorm, A. (2015). Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(10), 887–897. doi: 10.1177/0004867415600891

- Jorm, A., Korten, A., Rodgers, B., Jacomb, P., & Christensen, H. (2002). Sexual orientation and mental health: Results from a community survey of young and middle-aged adults. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), 423–427. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.423

- Kelly, C. M., Jorm, A. F., & Kitchener, B. A. (2009). Development of mental health first aid guidelines for panic attacks: A Delphi study. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 9(49). doi:10.1186/1471-244X-9-49.

- Kelly, C. M., Jorm, A. F., & Kitchener, B. A. (2010). Development of mental health first aid guidelines on how a member of the public can support a person affected by a traumatic event: A Delphi study. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 10, 49. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-49

- Kelly, C. M., Jorm, A. F., Kitchener, B. A., & Langlands, R. L. (2008). Development of mental health first aid guidelines for suicidal ideation and behaviour: A Delphi study. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 8(17). doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-17

- King, M., McKeown, E., Warner, J., Ramsay, A., Johnson, K., Cort, C., … Davidson, O. (2003). Mental health and quality of life of gay men and lesbians in England and Wales. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(6), 552–558. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.6.552

- King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., & Nazareth, I. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 8(70), doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-70.

- Kingston, A. H., Jorm, A. F., Kitchener, B. A., Hides, L., Kelly, C. M., Morgan, A. J., … Lubman, D. I. (2009). Helping someone with problem drinking: Mental health first aid guidelines – a Delphi expert consensus study. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 9, 79. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-79

- Kingston, A. H., Morgan, A. J., Jorm, A. F., Hall, K., Hart, L. M., Kelly, C. M., & Lubman, D. I. (2011). Helping someone with problem drug use: A Delphi consensus study of consumers, carers, and clinicians. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 11(3). doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-3.

- Kitchener, B., Jorm, A., & Kelly, C. (2013). Mental Health First Aid Manual (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Mental Health First Aid Australia.

- Kitchener, B., Jorm, A., & Kelly, C. (2015). Mental Health First Aid International Manual. Melbourne: Mental Health First Aid Australia.

- Langlands, R. L., Jorm, A. F., Kelly, C. M., & Kitchener, B. A. (2008a). First aid for depression: A Delphi consensus study with consumers, carers and clinicians. Journal of Affective Disorders, 105(1–3), 157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.004

- Langlands, R. L., Jorm, A. F., Kelly, C. M., & Kitchener, B. A. (2008b). First aid recommendations for psychosis: Using the Delphi method to gain consensus between mental health consumers, carers, and clinicians. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(3), 435–443. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm099

- Leonard, W., Pitts, M., Mitchell, A., Lyons, A., Smith, A., Patel, S., & Couch, M. (2012). Private lives 2: The second national survey on the health and wellbeing of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender (GLBT) Australians. Melbourne: The Australian Research Centre in Sex Health and Society, La Trobe University.

- Mental Health First Aid Australia. (2016). Considerations when providing mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person: A Delphi study. Melbourne: Author.

- Pitts, M., Mitchell, A., Smith, A., & Patel, S. (2006). Private lives: A report on the health and wellbeing of GLBTI Australians. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe Univerity.

- Ross, A., Kelly, C., & Jorm, A. (2014a). Re-development of mental health first aid guidelines for non-suicidal self-injury: A Delphi study. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 14(241). doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0241-8.

- Ross, A., Kelly, C., & Jorm, A. (2014b). Re-development of mental health first aid guidelines for suicidal ideation and behaviour: A Delphi study. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 14(236). doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0236-5

- Skerrett, D. M., Kõlves, K., & De Leo, D. (2015). Are LGBT populations at a higher risk for suicidal behaviors in Australia? Research findings and implications. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(7), 883–901. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2014.1003009

- Suicide Prevention Australia. (2009). Position statement – suicide and self-harm among gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender communities. Leichhardt: Author.

- Wisniewski, A. B., & Mazur, T. (2009). 46, xy DSD with female or ambiguous external genitalia at birth due to androgen insensitivity syndrome, 5-reductase-2 deficiency, or 17-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency: A review of quality of life outcomes. International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology, article no. 567430. doi:10.1155/2009/567430.