Mental health and wellbeing is essential, not only for quality of life, but also because it is a significant determinant for physical health and critical to the social and economic prosperity of society. To ensure that evidence based practice is sustainable in the longer term, strategic implementations plans are required, along with policy, across all levels of local, state and federal government. Enhancing the capacity of the workforce is a critical component of these endeavours to close the research – practice implementation gap and address current challenges, including inequalities and the social determinants of mental health.

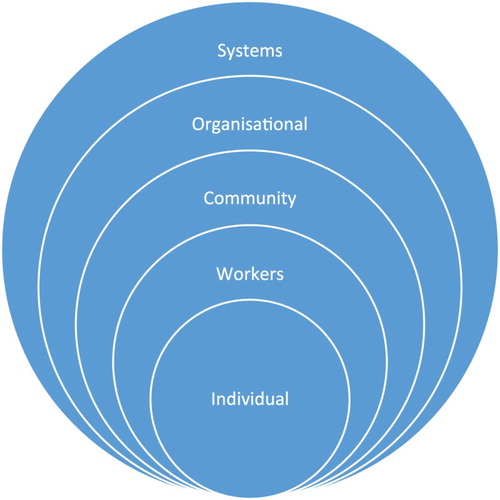

The various elements involved in enhancing workforce capacity might be conceptualised at several levels (see ). At its core, capacity building involves promoting an individual's capacity to recognise the benefits of positive mental health, seek help if required and offer assistance to those who may need it. Some of the recent issues of the journal explored these issues in some depth (Bond et al., Citation2017; Kauer, Buhagiar, & Sanci, Citation2017). The nature of help seeking assumes that services are welcoming, engaging, accessible and responsive to the needs of different population groups, as highlighted by Loughhead, Guy, Furber, and Segal (Citation2018) and Schweizer et al. (Citation2018), in the current issue.

Figure 1. Potential capacity building targets in mental health promotion, prevention and early intervention.

The next level involves workers in the field, who need to have the confidence, attitude, skills and knowledge to identify, support and intervene on the mental health needs of individuals, groups and/or communities. Targeted training needs to acknowledge that professional groups will hold various responsibilities and provide different specialisms, even if some core competences might be expected (Maybery, Goodyear, O’Hanlon, Cuff, & Reupert, Citation2014). Accessible professional development, which might range from awareness raising to specific skill development, needs to encompass the training of tertiary students as well as the current workforce (Reupert, Maybery, & Morgan, Citation2015). I like to think that this journal, in its own small way, contributes to these training efforts.

At another level, community capacity building ensures that community leaders and groups have the opportunity, means, skills and knowledge to identify their own mental health needs and develop, in collaboration with others, appropriate responses. A community's collective knowledge and mental health behaviours should inform what mental health workers do, when and how, as demonstrated in two papers from the current issue, Cutler, Reavley, and Jorm (Citation2018) and Patel, Caddy, and Tracy (Citation2018).

At the next level, organisations play a key role in promoting workforce capacity by demonstrating a commitment to, and leadership in, promotion and prevention, and by providing the necessary IT and other infrastructure systems to allow this work. The provision of training, supervision and incentives are other key elements that organisations are responsible for. Finally, systems capacity includes policy development, procedures and supports for interagency collaborations, an appropriate allocation of resources (including funding, time, and personnel), and legislature and advocacy initiatives. A strategic and goal orientated vision generated at a systems level is needed, that encapsulates, in an equitable and culturally sensitive manner, the mental health needs of the population, developed in consultation with the proceeding stakeholders. Systems initiatives and policies need to cut across physical, cultural and economic environments, which necessitates working with multiple workplaces as contexts for creating and promoting positive mental health. At the systems level it is important to invest in research that is informed by practice across all these levels, to further inform our understanding of the determinants of mental health and the determinants of mental health and appropriate evidence based strategies for promoting health environments. For example, researchers might identify the existing capacities of individuals, the workforce, community, organisation or system, that can be used for benchmarking purposes and to identify future priorities. Focusing on prevention and the promotion of positive mental health are underlying principles inherent across all levels of capacity building.

Each of these targets, ranging from an individual to a systems approach, can be used to inform how the workforce might identify, develop, prioritise, implement and evaluate various mental health promotion, prevention and early intervention initiatives and programs. Nonetheless, we know that working at one level alone is not sufficient to bring about enduring change, for example, introducing legislature but without targeted training (Tchernegovski, Maybery, & Reupert, Citation2017). Accordingly, also inherent in is the interactive involvement of consumers, family members, workers, community members, managers, policy makers, funders and researchers across all levels.

Given this framework, it is with much pleasure that I welcome the first issue of 2018, which, as a whole, epitomises the points presented above and highlights possible deficits in the various capacity building levels. For example, Loughhead et al. (Citation2018) found that while young people acknowledged the role of teachers, school counsellors, parents, and friends when responding to crisis, young people also described their fear and uncertainty when engaging with services. These findings have implications for how services and workers might engage with and support young people. Emphasising the need for interagency collaborations between vocational and mental health services, Holloway et al. (Citation2018) found that of young people presenting to mental health services, those who were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, male, homeless, diagnosed with a substance use disorder, or diagnosed with a substance use disorder or a neuro-developmental disorder, were most vulnerable to non-participation in employment, education or training. Further highlighting implications for the way in which mental health services are designed, and how workers might engage with consumers, Schweizer et al. (Citation2018) identified, from the perspectives of consumers, key elements of the consumer-provider relationship within a case coordination model, while Tribe, Bielawska and Tracy (Citation2018) evaluated a day treatment service, again from the perspective of consumers. Another service evaluation paper, from Rasmussen, Donoghue, and Sheehan (Citation2018) investigated the impact of Aboriginal art activities on the suicide/self-harm risk behaviours of Aboriginal prisoners and showed that suicide/self-harm history and number of days attending Aboriginal art was associated with the incidence rate of suicide/self-harm risk assessments.

At the community level, Cutler et al. (Citation2018) investigated public perspectives about mental health, while Patel et al. (Citation2018) sought the views of a group of individuals about psychiatrists and psychologists. Knowledge about depression was highest and knowledge about anxiety and psychosis were lowest (Cutler et al., Citation2018) while Patel et al. (Citation2018) found that psychiatrists were seen as more authoritarian, in comparison to psychologists, who were perceived as friendlier. Both speak to the need for raising community awareness about specific types of mental illness and increasing mental health literacy. Demonstrating a timely responsiveness to community need, Girdler, Dhu, and Isaacs (Citation2018) describe how a Diploma of Community Services (Alcohol and other Drugs and Mental Health) was modified and delivered in the remote region of Katherine in the Northern Territory.

Capacity building is often discussed in various government and research papers but continues to provide a challenge for many of us, perhaps because of its multifaceted and complex nature. Capacity building aims to foster involvement, empowerment, and ownership of issues and accordingly needs to extend beyond traditional health sector boundaries. The commitment of this journal to capacity building is evident in these papers. We hope that the articles in this issue will be of practical relevance to readers with the same commitment.

References

- Bond, K. S., Jorm, A. F., Kelly, C. M., Kitchener, B. A., Morris, S. L., & Mason, R. J. (2017). Considerations when providing mental health first aid to an LGBTIQ person: A Delphi study. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention, 15(2), 183–197. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2017.1279017

- Cutler, T. L., Reavley, N. J., & Jorm, A. F. (2018). How ‘mental health smart’ are you? Analysis of responses to an Australian broadcasting corporation news website quiz. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention, 16(1), 5–18.

- Girdler, X., Dhu, J., & Isaacs, A. (2018). Delivering a diploma of community services (alcohol and other drugs and mental health) in the remote town of Katherine (NT): A case study. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention, 16(1), 77–87.

- Holloway, E. M., Rickwood, D., Rehm, I. C., Meyer, D., Griffiths, S., & Telford, N. (2018). Non-participation in education, employment and training among young people accessing youth mental health services: Demographic and clinical correlates. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention, 16(1), 19–32.

- Kauer, S., Buhagiar, K., & Sanci, L. (2017). Facilitating mental health help seeking in young adults: The underlying theory and development of an online navigation tool. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention, 15(1), 71–87. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2016.1237856

- Loughhead, M., Guy, S., Furber, G., & Segal, L. (2018). Consumer views on youth-friendly mental health services in south Australia. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention, 16(1), 33–47.

- Maybery, D. J., Goodyear, M. J., O’Hanlon, B., Cuff, R., & Reupert, A. E. (2014). Profession differences in family focused practice in the adult mental health system. Family Process, 53(4), 608–617.

- Patel, K., Caddy, C., & Tracy, D. K. (2018). Who do they think we are? Public perceptions of psychiatrists and psychologists. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention, 16(1), 65–76.

- Rasmussen, M. K., Donoghue, D. A., & Sheehan, N. W. (2018). Suicide/self-harm-risk reducing effects of an Aboriginal Art program for Aboriginal prisoners. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention. doi:10.1080/18387357.2017.1413950

- Reupert, A. E., Maybery, D. J., & Morgan, B. (2015). E-learning professional development resources for families where a parent has a mental illness. In A. Reupert, D. Maybery, J. Nicholson, M. Gopfert, & M. Seeman (Eds.), Parental psychiatric disorder: Distressed parents and their families (pp. 288–300). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schweizer, R., Honey, A., Hancock, N., Berry, B., Waks, S., & Newton Scanlan, J. (2018). Consumer-provider relationships in a care coordination model of service: Consumer perspectives. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention, 16(1), 88–100.

- Tchernegovski, P., Maybery, D., & Reupert, A. (2017). Legislative policy to support children of parents with a mental illness: Revolution or evolution? International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 19(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1080/14623730.2016.1270847

- Tribe, R. H., Bielawska, M., & Tracy, D. K. (2018). Experiences of a day treatment service using phenomenological analysis: “Six weeks of little steps in the right direction”. Advances in Mental Health: Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention, 16(1), 48–64.