ABSTRACT

This article explores the psychological impact of growing up with a parent with a mental illness. A life course Model of Acquiescence is developed to show how coping strategies developed by children go on to have impact into adulthood.

Undertaking biographical narrative interviews with 20 adults who had grown up with a parent with a mental illness produced accounts from childhood to the current day. Thematic narrative analysis was used to gain insight into how the participants made sense of their parent’s mental illness and their own role within it.

Participants recalled experiences and family circumstances that were traumatic, unsafe and overwhelming. They dealt with these by attributing adversities to the mental illness and focusing solely on the vulnerabilities of their parents, thus adopting a caring role and ignoring their own needs. Most presented themselves as resilient, adaptable and resourceful, in employment and with intact relationships. However, despite this apparent success, all expressed a profound sense of lost opportunity and low self-esteem.

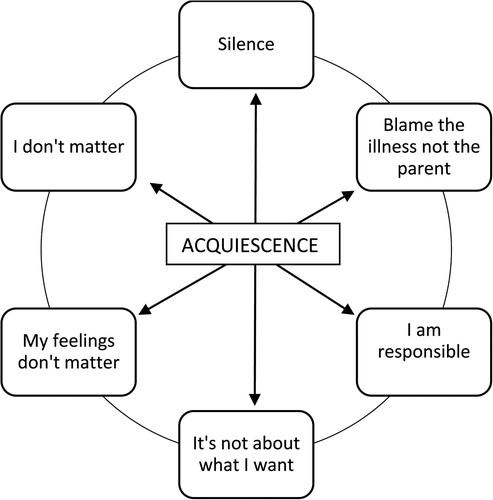

In the Model of Acquiescence, we illustrate how and why children adapt to challenging and complex family experiences and explain how the personal and interpersonal process of parentification develops. An individual positions themselves as insignificant, powerless and silenced, only able to affect change or maintain relationships by anticipating, identifying and meeting other people’s needs. This model underlines the need to support such children’s psychological wellbeing using a whole family approach to understand the impact of parental mental illness and centre the child’s needs.

Introduction

The mental health and wellbeing of children are intimately interlinked with that of their parents. For some children of parents who live with severe and enduring mental illness this can result in negative outcomes which are well established within the literature (Reupert & Maybery, Citation2016). These outcomes can manifest in multiple areas of their lives: from their own psychological health (Reupert & Maybery, Citation2009), educational achievement (Becker & Sempik, Citation2019), increased behavioural and developmental difficulties, isolation (Reupert & Maybery, Citation2016), increased substance misuse as adults (Mowbray & Oyserman, Citation2003) and bounded agency in adulthood (Blake-Holmes, Citation2019; Hamilton & Adamson, Citation2013).

However, it is important to be mindful that each situation and its impact is highly individual. Children of parents with a mental illness are not a homogenous group, their experiences and the impact of those experiences are unique to the individual and cannot be generalised.

Parental mental illness (PMI) is not linked with any specific outcomes for a child. Rather, it is part of a complex dynamic between the security of the parent–child relationship and the social context of the parent’s individual experience, their family, community and society. Equally, not all children will be adversely affected by PMI, nor will all children in the same family be affected in the same way (Reupert & Maybery, Citation2016). There are complex factors which influence the vulnerability and resilience of every child. There are also clear interactions between the needs of complex families and the socio-economic adversities that they face which make the impact of mental illness in isolation harder to discern. Moreover, it has been shown that given the right circumstances, positive outcomes can be derived from providing care to loved ones. Young carers acquire a range of practical and emotional skills, take pride in expressing their love through care and demonstrate empathy, resilience and self-efficacy (Gough & Gulliford, Citation2020; Rutter, Citation2013). It is the recognition of these factors which expands our understanding of the wide-ranging impact of PMI, from identifying adverse outcomes, to understanding how they happen and how we can mitigate them.

This paper presents an innovative Model of Acquiescence drawn from the findings of this study. The model offers a better understanding of how the complex needs of PMI can affect the care dynamics within the family, lead to parentification for the child and impede their differentiation of self.

Relationships and care within the family

The impact of PMI on children is often understood to result in part from the care and responsibility they take on within the family. This can range from practical chores to more emotional tasks such as monitoring mental state, looking for signs of relapse, lifting their parent’s mood and giving them a reason to stay alive (Blake-Holmes, Citation2019). These emotional tasks can feel overwhelming and exhausting for a child and can be difficult to quantify or articulate to individuals outside of the family.

A further impact of PMI links to the psychological impact rooted in the child’s understanding of their parent’s illness, their family relationships and the way they position themselves within what can be a complex and fragile dynamic.

Attachment theory

Attachment theory employs an understanding of relationships and psychological development as it considers the role of emotions, and in its developmental guise seeks to understand the psychological strategies used by children to make sense of and adapt to their social environment (Howe, Citation2005). PMI can affect the psychological and emotional development of children (McCormack et al., Citation2017). At a fundamental level, children need to feel safe and seen, and at times of adversity they must believe that their caregivers value them and are able to provide protection (Howe, Citation2005). However, for parents to provide the necessary safe physical environment and secure emotional attachment optimum for a child’s healthy development, they need to be able to understand the emotional needs of their children, to hold them in mind and respond to them in a self-reflexive manner (Nolte, Citation2013). This child-mindedness can be challenging for a parent experiencing mental illness, as they attempt to manage the specific manifestations and consequences of their own emotional distress in addition to the expected challenges and stresses of parenting in general (Howe, Citation2005; Nolte, Citation2013).

This can be further complicated by the debilitating side effects of psychotropic medication, fear of punitive professional intervention and stigma, preventing them from accessing and building the support networks that most parents rely upon (Nolte, Citation2013). In such circumstances, the relationship between the child and the parent can become reversed in which the child begins to take on a substantial caring role for the parent. At its most extreme form, this can result in the child beginning to ‘parent’ the parent.

Parentification

Parentification is defined as a pattern of family interaction in which the child provides care and support towards their parent as opposed to receiving it from the parent themselves. This care and support require the child to perform tasks they are not emotionally or developmentally equipped for. Parentification can have negative consequences for children which endure into adulthood. These can include an increased risk of internalising problems and the development of a lack of sense of self, particularly if the level of responsibility within the parentified relationship impedes the child from engaging with their own developmental tasks. The emotional dimension of parentification carries a higher psychological risk for children as it is difficult to quantify or frame in a constructive manner (Borchet et al., Citation2018).

Parentification is a multidimensional concept that is unique to both the individual experiencing the phenomenon and the context that they are situated in and as such there are individual and contextual attributes. These include the perceived fairness of the tasks; whether they are provided because of a sense of felt obligation, and if the care that is provided is acknowledged and reciprocated. These individual attributes are inextricably influenced and impacted by external factors such as the societal perception of caregiving, the nature of illness and the support available to the family (Hendricks et al., Citation2021). When required to perform tasks beyond a child’s level of maturity without support a child may struggle to maintain a resilient sense of self amid challenging caring relationships (Hendricks et al., Citation2021).

PMI can in some circumstances detract from the cohesion, emotional responsiveness, flexibility and adaptiveness required for a well-functioning family system. If the illness is severe and/or enduring it can become overwhelming for the family and the care receivers’ needs can appear to take priority over the needs of the child. Such a shift in the need and impact on the family system can damage the relationship between the care receiver and the caregiver, thus distorting roles and expectations within the family system.

Children in family systems

It is helpful to consider the lived experience of children growing up with PMI through a lens of Bowen’s family systems theory (Haefner, Citation2014. Hooper, Citation2007), which understands that all human relationships are underpinned by the push and pull of family dynamics, orientated around two driving forces: one for togetherness, the other for separateness. This means that even decisions and behaviours which are seemingly made independently of the family are still heavily influenced by that system, with its customs, expectations and responses in constant dynamic flux over time and with little change over generations (Haefner, Citation2014; Pyecroft & Bartollas, Citation2014). Both forces of togetherness and separation are key for child and human development.

Togetherness, reflecting cohesion to the family system, acts as the bedrock of relationship patterns throughout the life course. When cohesion is strong (but not constrictive), these family bonds also give security and self-esteem, offering a platform on which to develop a secure identity (Hooper, Citation2007). Its nemesis, separation, enables individuals to develop differentiation of self, whereby children are able to mature into independent adults, and forge their own path. While Bowen’s theory advocates that differentiation of self-promotes self-efficacy and self-identity, its lack can leave individuals more vulnerable to criticism and conflict, and to seek external reinforcement from others (Haefner, Citation2014). A lack of differentiation of self is also described as emotional fusion; a difficulty in telling one’s own emotional responses apart from those of the family system, associated more so with families overwhelmed by chronic anxiety (Haefner, Citation2014; Hooper, Citation2007; Pyecroft & Bartollas, Citation2014).

There are strong associations between this and children who assume parentified roles (Hooper, Citation2007; Jankowski et al., Citation2013). Parentification itself positions the child as caregiver and the parent as care receiver. This re-prioritisation de-centralises the child from expectations which usually ensure a focus on their care and developmental needs. It can link to childhood trauma and child neglect especially in emotional parentification where the child attempts to compensate their parent for his/her emotional and psychological distress, suppressing their own needs in favour of their parent, and possibly other siblings (Jankowski et al., Citation2013).

Through this parentified role the child strives to access and maintain a relationship with the parents, which can come at the expense of their own needs (Howe, Citation2005). McCormack et al. (Citation2017) defined a sophisticated development of this as a ‘caretaker child’ in which the child demonstrates highly skilled behaviours designed to anticipate and meet the needs of their parents. These behaviours are designed to keep their home environment stable, to protect themselves and their families while nurturing an emotional link with their parents. Becoming skilled in reading and responding to unpredictable behaviour, the caretaker child can find themself in a constant heightened state of vigilance and arousal. While these caretaking behaviours might be construed as a demonstration of resilience and competency in the child, they can also be masking the child’s own needs.

A further risk is that parentified children are less able to develop differentiation of self-due to the co-dependency created. Differentiation of self is a function which enables children to grow into independent adults, capable of self-determination and identity formation which does not simply replicate their parents’ projections. It is associated with higher self-esteem and secure identity, while accommodating long-lasting ties with families of origin (Haefner, Citation2014).

Parentification literature focuses on defining it as a concept and examining the potential outcomes for the children and young people who experience it. However, little is known about the mechanism which results in the development of a false self and the caretaker persona.

In this paper, we contend that the attributes of parentification, the relational shift in the family system and the development of a caretaking persona is not a conscious decision that is made by the child. It is, rather, a gradual psychological process in which the child not only learns how to put aside their own needs but eventually loses the ability to recognise their own needs at all, intuitively acquiescing to the needs of the person they are caring for. Using this Model of Acquiescence allows us to conclude by considering the way acquiescence may mask the needs of children to professionals working with complex families and make recommendations for professionals to recognise the development of this psychological strategy and mitigate it.

Methods

This paper is based on a study which sought to explore the biographic narratives of adults who had grown up with PMI. The aim of the study was to shed light on how these (adult) children had made sense of their parent’s illness and their own role within it. This qualitative research involved 20 biographical narrative interviews (Wengraf, Citation2001) with individuals across the United Kingdom who identified as having grown up with PMI. The research questions explored were: how do adults who grew up with a parent with mental illness make sense of their childhood and what effect does this understanding have on them as adults?

Sample

Inclusion criteria included participants whose parents had met the threshold for secondary mental health services which encompassed admission to psychiatric hospital, community-based specialist mental health care and oversight by a psychiatrist. Eligibility for the study was confirmed by participants’ verbal report of their parent’s mental health service use in early discussions before the research. Because the study was focused on the experience of the child whilst growing up it was neither ethically appropriate nor viable to ask to see official documentation pertaining to the mental health status of their parents as such the self-report and coherent accounts of the participants were trusted.

Recruitment was via a snowball strategy, beginning with a purpose-built Facebook page. This page was shared on the University of East Anglia Centre for Research on the Child and Family Twitter feed and individuals from the lead researcher’s professional and personal network. As the study progressed participants also shared the details within their own networks. The study was also discussed by the lead researcher during a Young Minds conference presentation and the information sheet was provided to interested delegates. Ten participants were recruited through social media, eight following the conference and two were recommended by another participant. Potential participants contacted the researcher and initial information, and eligibility criteria were discussed. Four individuals made contact who were not eligible and in these cases the researcher acknowledged their stories and signposted them to mental health support organisations.

Ethics

Given the sensitive nature of this study, considerable regard was given to the potential impact on participants both during the interview and after. The professional background of the lead researcher gave them skills in anticipating and responding to distress. Furthermore, during the selection process, the potential for distress associated with unresolved memories was discussed and the participants were encouraged to think of support they might need during or after the interview. Participants had the opportunity to take a break or stop the interview at any point. They were also able to withdraw from the study and rescind their data for up to a month after the interview. Debrief sheets were provided to the participants individually tailored to include the support services in their area. Two participants required a follow-up discussion the day after the interview, and one gave the researcher permission to contact local services (that they were known to) on their behalf. While it is acknowledged that such sensitive issues can carry a risk of distress for people, it is important that these stories are heard, and telling the stories can be cathartic and validating (Padgett, Citation2017; Pillow, Citation2003). The embodied nature of this research also meant at times that interviews triggered an emotional response from the researcher. A system of reflexive supervision was in place for three sessions to manage this. No identifying details were disclosed in these sessions or the final research. Ethical approval was granted by the University Ethics Committee.

Participant details

Participants ages ranged between 19 and 54 years old with a mean age of 31. Four participants came from a minority ethnic background. One participant had left school without any qualifications, eight participants had a degree (or were currently at university). With regards to employment, sixteen were in work, one was unemployed, two were stay-at-home parents and one was retired. Four participants were siblings and six still lived at home with parents. Sixteen of the sample still considered themselves as providing care and support to their parent(s). Seven of the participants were parents. Seventeen of the participants expressed concern about their own mental health. Despite actively seeking to recruit male participants, there was a gender imbalance (five male, fifteen female). This was also reflected in the parents they spoke about; 12 participants spoke about their mother’s mental illness, five spoke of their father’s and three spoke of both of their parents being unwell. However, in each of these three latter interviews their focus was predominately on their memories of their mother.

Interviews

Participants were invited to tell their story from childhood to the present day in face-to-face interviews. They were encouraged to structure the story in whichever way they liked. Consistent with the Biographical Narrative Method (Wengraf, Citation2001) the interviewer listened with minimal interruption, questions or prompts. Participants lived within the UK, and the sole researcher travelled to them and met them in private spaces such as their own home or other venues of their choice that ensured privacy. The interviews were audio recorded and lasted an average of 2.25 hours. Each interview was then transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The data were analysed using a thematic narrative method (Riessman, Citation2008). Transcripts were coded and a coding index was created for each participant. Framing devices such as turning points, narrative strategies and identity statements were highlighted within the transcripts. Emerging themes were visually mapped for each participant. These were not selected to be representative but rather to develop theoretical exploration and argument. To retain a sense of the narrative, a biographical account was developed for each interview, isolating and ordering narrative episodes into a chronological timeline. To keep the narratives separate, each interview was analysed individually, engaging in an iterative process of expanding and collapsing thematic categories and narrative interpretation. Finally, coding and chronologies were combined to examine the way themes and narratives interacted within and across the cases.

Reporting

All the participants have been given pseudonyms and details have been removed to protect anonymity and preserve confidentially. Some aspects of the narratives cannot be reported as they are too identifiable and highly sensitive.

Findings

To fully comprehend the psychological impact that PMI can have on some people it is important to be clear about how it was experienced by the child, and how they continue to experience it into their adult lives.

Experiencing PMI as a child

The individuals who gave their stories to this study recalled becoming aware of their parent’s mental ill health in a variety of ways, either as a sudden critical incident or a gradual realisation. Their age and the way they became aware of their parent’s mental ill health were significant to how they made sense of it, and their role within it. Another significant factor was the behaviour they saw in their parents which they attributed to the mental illness.

Highly emotional, unpredictable and risky behaviour was the most difficult for the participants to manage at the time. However, it was the chronic detached or emotionally flat behaviour that appeared to have a increased long-term negative connotation for participants. In these circumstances, if their parents were unable to maintain a child-minded focus the participants need for a secure emotional attachment was neglected.

The severity of experience

Most participants spoke about traumatic experiences because of PMI, they also spoke of disproportionate levels of adversity and stress throughout their childhood. They described having to respond to significant risks of physical harm to their parents, their siblings and themselves. They recalled feeling vulnerable, frightened and alone and recounted their extraordinary efforts to hide what was going on at home from others for fear of judgement or intervention. Eight participants spoke of childhoods that held examples of physical neglect, three spoke of being physically hurt by their parents when they (parents) were acutely unwell. Three spoke of being sexually abused by individuals who they believed used their parent’s mental ill health and vulnerability to gain access to them. Participants recalled feeling an overwhelming sense of responsibility which prevented them from seeking support. One participant recalled being told by their father after a particularly traumatic event when they were nine years old, ‘you can’t tell anyone because if you do, they will take you away and then your mum will kill herself and it will be your fault’ (Jess).

Despite these extreme challenges not being counterbalanced by additional support or obvious protective factors, many of the participants appeared on the surface to negotiate their childhoods remarkably well. Only six of the participants came to the attention of health or social care services in their own right. In each of these cases, they describe their experience of services as brief and disinterested. None of the participants were raised as a concern by the mental health services supporting their parents. None of the participants spoke about coming to the attention of the police despite five of them recalling the police being required at times to respond to their parent’s behaviour. This reflects findings in the literature about child protection and safeguarding in the UK which cites failings in interagency communication about risks to children (Brandon et al., Citation2020; Munro, Citation2011).

As previously discussed, only one participant left school with no qualifications, indeed, four participants who had particularly difficult home lives described themselves as model pupils who were quiet, conscientious and keen to please. However, they still talked of the school day as difficult, where they were often exhausted or worried about what would be happening at home. They saw themselves as having few friends or being an outsider. Despite this, they viewed school as a sanctuary and were careful to not get ‘found out’. Motivation to remain hidden from stigmatising attitudes of onlookers has been well documented in both the young carers literature (Blake-Holmes & McGowan, Citation2022; Warhurst et al., Citation2022) and in the broader literature pertaining to social judgement (Tyler, Citation2020).

There was a clear sense across the narratives that the participants were skilled in keeping themselves and subsequently their parents under the radar. Some spoke with pride of how they were viewed by professionals as quietly competent and resilient while many reflected as adults that they had been let down, ignored and neglected by the professionals who could have protected them. Even with this reflection, a common theme across the narratives was of minimisation, where memories of adversity and trauma would be concluded by several participants with a phrase similar to ‘it wasn’t ideal but it’s fine’ (Roman). While the version of themselves presented to the outside world was one of resilience and successful adaptation in the face of adversity, there are examples which support Howe’s (Citation2005) assertion that many developed caretaking strategies to protect themselves from the vulnerability and emotional harm they were facing. These included limiting their opportunities and being invisible. They learnt to put their own needs aside and focus on the needs of their parent (and in some cases siblings) in order to maintain a relationship and cope psychologically (Haefner, Citation2014 cited Bowen 1966; Pyecroft & Bartollas, Citation2014).

I’m not ambitious. I could have been but going through all that turmoil does something to you. You’re always waiting for something to go wrong; you just can’t dedicate yourself to something else 100%. – Terry

When was looking after mum. I was invisible, I needed to just do whatever she wanted to do and it didn’t matter about me … it took me a long time to understand what I like doing and to be visible again. – Jess

Long-term outcomes

As the participants reflected about the impact of their experiences of growing up with PMI, many stated that their caring responsibilities and concern continued still and that their experiences were key to their adult identity, with childhood experiences and relationship with their parents as being ‘written through’ them.

Several participants felt that PMI had been a significant factor in the decisions they made regarding their education and careers. Some described not feeling able to engage with further education because of the care needs of their parents, while others specifically chose universities that were close to home and were perceived as less demanding. This was also mirrored in the careers that participants chose, three of the participants had to choose jobs that would fit into their parents’ care routines, for example, part-time shift work. Five participants spoke about not pursuing ambitions because they did not feel entitled to do so, or because they were concerned how their life choices would affect their parent’s mental health, or their ability to respond to periods of ill health.

A significant proportion of the participants (12) were working in a caring role. Within these interviews, participants claimed the skills they had developed in response to their childhood experience, were an advantage to them within their adult lives, either in terms of bestowing them with an extra level of maturity and independence or equipping them to support others in need. Jess described herself as developing a ‘Swiss Army Knife’ of care skills whereas Lucy, a Mental Health Nurse, recalled ‘I’ve been training to work with people with mental health problems my whole life’.

Some participants also discussed the difficulties in forming and maintaining romantic relationships, both in terms of having the physical time to dedicate to these relationships and to whether they felt comfortable with their role within them. At times some felt that they would be drawn into adopting a caretaking identity which mirrored that which they experienced with their parents.

The implications and impact of becoming a parent was also a powerful theme, which emerged from 17 of the interviews. Its presence in each participant’s narrative was not just related to their experience of becoming a parent, but also their hopes and fears, the preparation they felt they had to do or the reasons they felt that the option of parenthood had been removed for them. Whatever the focal point, this theme was a significant part of their narratives and was deeply interwoven with their personal sense of identity.

Six of the female participants spoke about not feeling able to have children of their own due to a belief that there would not be space in their lives as they continued to care for their parents.

She’s never going to get better, I think that more than likely she’s going to get worse, she is always going to be a burden. I’m always going to feel responsible, it’s like having grown up children you never gave birth to. – Sophia

For the seven who had children, there was a need to consider and plan how they would manage the care they had previously given their parents against their new responsibilities to their own children. In the extract below Freya illustrates how forming her own family has finally enabled her to achieve differentiation of self, when a child is able to grow independently of their birth parents yet still retain their bonds (Haefner, Citation2014 ):

I think having a baby and having a child has helped to disconnect me from her … from the point that you’re pregnant you’re responsible for them and I knew that I couldn’t allow myself to get too stressed by the situation because it wouldn’t just impact me it would impact somebody else. So I think that helped me to be removed from her. – Freya

This strength of conviction about what is acceptable for their own children and the steps taken to protect them from potential harm is particularly interesting and poignant when juxtaposed with what they not only experienced throughout their own childhood, but accepted, internalised and acquiesced to, minimising it as ‘not ideal but it’s fine’ (Roman).

Psychological strategies to cope and barriers to accessing support

A key theme emerged across the narratives of the participants being unable to articulate their experiences and associated feelings. As they strove to make sense of the illness and their role within it (often without adult guidance and support) psychological schemas and strategies were developed. These schemas became enmeshed with their own sense of identity and carried forward into their adult lives.

Being unable to articulate their experience (silence)

The most consistent theme within the narratives represented the inability of the child to express or communicate what was happening. Initially, this would be because they did not realise there was anything different about their experiences at home or in their relationship with their parents. As they began to notice differences between themselves and their friends, they faced the double bind of not having sufficient understanding or language with which to express themselves whilst also being at an age when ‘fitting in’ with peers was a priority.

Seb said that he had felt that he would have been singled out and potentially bullied if he had spoken about his father’s behaviour:

I didn’t want to kind of be singled out in any way or because I wouldn’t have known how to express it maybe. So it’s kind of like, well my dad just cries all the time, which I knew wasn’t sort of normal. So I didn’t really have anyone that I could talk to. – Seb

I wasn’t allowed to tell anyone at school because my dad was the headmaster of our school it was like it was this dirty secret and my mum whenever she had a suicide attempt, I wasn’t allowed to tell anybody. – Emily

The taboo untouchable illness (Blame the illness not the parent)

Several participants spoke about PMI as if it was a separate entity to their parents, with some trying to differentiate between what was behaviour driven by the illness and what was their parent’s personality. Many viewed their parent’s illness not only as unpredictable but also beyond their parent’s control:

There’s not a lot of control in a mental illness there’s only so much blame and stuff that can be thrown around. – Roman

Always taking on responsibility (I am responsible)

Participants recalled feeling extremely high levels of responsibility for their parents. Some of this was directly asked of them, however a great deal was precipitated by a felt obligation, learnt over time and experience. As with the reversal in expectations, these extreme levels of responsibility deviate widely from what we would generally expect for a child. Rather than being concerned with school, friends and aspirations, these children were focused on protecting their parents and keeping their family safe.

Georgina recalls feeling ‘100% responsible’ for her mother’s emotional stability and this being reinforced by the professionals involved, who would ask what she had done if her mother was distressed. This displacement of typical childhood priorities left her feeling overwhelmed and isolated. She described being unable to ask the mental health workers for help, as she worried they would blame her for upsetting her mother. Equally, her mother would portray herself as feeling bullied and manipulated by services which would mean that Georgina felt that she had to protect her mother from intervention, keeping them at arm’s length. Natalie spoke about her father’s fear of services and her own subsequent mistrust. Natalie’s sense of responsibility was deepened further by her father’s sole trust in her:

When my dad’s manic or psychotic he’s very trusting of me and I don’t know why, like no one else in my family, like he’s convinced they’re all against him. But with me he will listen to me. I’m all he’s got. – Natalie

Because I never thought that I would escape that unit, I thought this is my life and I used to get quite frightened about that, my future would be just looking after her … I’m stuck, whether I like it or not. – Terry

I do get angry inside, but I can’t do anything about it, it’s not going to solve anything, I just have to get on with it and deal with it. I’ve dealt with it for 19 years like I can deal with it for the rest. – Jenny

You don’t really look at the impact it has on you unless you’re asked to. It put me behind and obviously it’s not mum’s fault, I always hate to say things like that as I feel like I’m bitching about her, I guess you go onto auto you just carry on. – Holly

Because a lot of it was about being there for her, and not my feelings. My feelings didn’t really matter because I suppose in those situations, if you tap into ‘hang on a minute how do I feel about this’ I wouldn’t have had enough strength to keep going to look after her really. – Jess

It’s my fault (it’s not about what I want)

Most of the participants felt a strong sense of responsibility towards their parents, this was combined with the acceptance that their parent’s needs had to come before their own. Fourteen of them spoke of regularly feeling that they had to put their own needs aside to be able to respond to and maintain their parent’s emotional stability and physical safety. This sense of relinquishing their own needs was further reinforced for seven participants who felt that they were part of the cause of their parent’s illness. Jess saw part of the trigger of her mother’s illness being her own experiences of sexual abuse, and Monica held herself entirely responsible for ‘infecting’ her mother with the illness. The other five, Vivienne, Ethan, Jenny, Terry, Sophia and Lucy described their mother’s illness as originating from the time of their birth or through the pressures of motherhood. During her interview, Jenny became extremely tearful while she spoke of her role in her mother’s mental illness:

She had post-natal depression with me. I know it’s stupid, but I feel like I caused it like it’s my fault. Cause I’m alive it’s my fault that’s she’s like this. Like I shouldn’t be here because it’s causing her, her I don’t know her to be the way she is, so I should change. – Jenny

My needs are not as important (my feelings don’t matter)

The tendency to put aside their own needs was at times a conscious act keenly felt by participants, for example when Jenny missed her own birthday celebration with friends to go home to support her mother who was distressed and suicidal:

I was the one picking her up on my birthday, like it’s my birthday can I not enjoy this day you know, no I can’t. Probably that sounds selfish on my behalf, but could I just have one day? – Jenny

We’re able to sit down as a family and talk about everything. Like you know from having an unwell dad to death to suicide to whatever came up, there’s no taboo subject in our family, we talked all the time about dad’s illness and his feelings but we never really talked about our feelings. Certainly, I think from my point of view I didn’t want to ever show that I’m kind of upset or struggling or whatever because I didn’t want to make things worse for them – To be honest with you I think like me crying a bit wouldn’t have sent him further down into a spiral of depression, but I guess as like a seven, eight, nine-year-old you don’t really know that. – Seb

I’d rather deal with it than have somebody else deal with this, if I can maintain as much of a normal childhood for them and they enjoy it, that’s important to me you know. I’d love to be in that situation but I’m not so if I can maintain someone else’s, so they don’t have to be in a situation then you know. – Jess

Denial of self-worth (I don’t matter)

The relinquishment of their own needs and feelings could be associated with a child’s motivation to protect those around them, friends, siblings or their parent as they saw their illness as central and untouchable. This, combined with the lack of opportunities to discuss their own feelings, their role in meeting others’ emotional and physical needs without reflecting upon their own, and the lack of awareness or recognition from others, contributes to a sense that they do not matter.

This was particularly pertinent for four participants who spoke of experiencing sexual abuse and being unprotected. This contributed to their perception of the world being an unsafe place, and that to assert themselves within it might render them even more insecure. Jess’s abuse from multiple perpetrators compounded her sense of not being wanted or of little worth. The role she had in caring for her mother, while in itself abusive, gave her a sense of belonging and purpose:

I know that from a very young age I wasn’t wanted, I think because I knew I wasn’t wanted it was kind of just keep myself to myself and if I wasn’t any trouble then at least I’m not in the way kind of thing, then when mum got really ill or went really downhill it was ah okay well just do this then and focus on her and try and make her feel better. – Jess

Discussion

In considering the needs of children that grow up with PMI, the impact of the experience is complex. There are contributory factors to the child’s needs, such as, attachment relationships, socio-economic resources and the network around the family. The timing and manifestation of the illness is key as is the developmental ability of the child to understand it and position themselves as involved but not enmeshed. However, it was clear through this study that many children are not able to access support in talking about and understanding their experiences with others and, in their isolation and their need to cope, they develop their own psychological framework and schema to help them cope. While this might protect them at the time and enable them to build a veneer of competence, in the long term it can be maladaptive and undermine their relationships with themselves and the world around them.

The model of acquiescence

Our definition of acquiescence is the reluctant and passive acceptance of (or submission to) something without protest. This sense of acquiescence was deeply embedded in the majority of the narratives and appears to be founded in the participants’ understanding of their parent’s mental illness and their role within it.

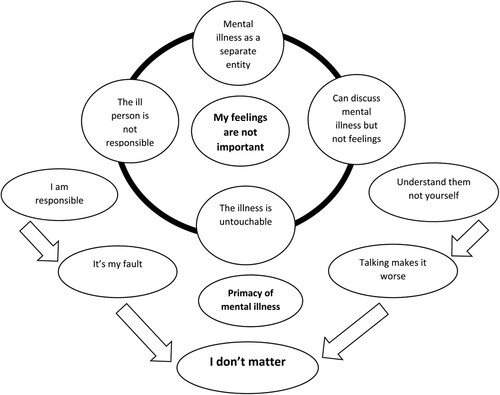

As illustrated in the findings this can be categorised into six domains that form a Model of Acquiescence. This model is presented in a cycle wherein each domain relates to, overlaps with and reinforces each other ().

The Model of Acquiescence was developed inductively from the research and can be interpreted through both the lenses of family systems and attachment theory.

From a family systems perspective the primary concern is PMI and the management of the associated behaviours. In response to this, the child sees themself as being responsible for and secondary to the mental illness, it is about what the parents need not about what the child might need or want. They do not have an expectation that their needs would or should be met, and do not feel justified to express anger about this as it is not the parent’s fault but rather a consequence of the mental illness which is beyond anyone’s control or reproach. This lack of regard for self can be exacerbated by the sense of personal blame the child takes for the mental illness and the parent’s subsequent distress ().

By acquiescing, putting their needs aside and focusing on the needs of their parents (and siblings) children of PMI can become skilled experts. Intuitively they can anticipate their parents needs and respond to their emotional states, managing crises with apparent ease. What might appear chaotic if they allowed it to be seen by the outside world only feels that way to them if they let their own needs, wants and aspirations be added to the mix. By accepting their role within their parent’s mental illness and subsequent family life, the chaos becomes a complex system of rules, prompts and expectations which if met by the child ensures a sense of relative stability and predictability. This adaptation of attachment behaviours can function to draw them closer to both their attachment figure and family system making them feel more safe and secure. This intersection between the family system and attachment theory gives new insight into how complex patterns, observations and responses are rehearsed and subsequently developed into psychologically embedded coping strategies.

Participants spoke about the high levels of perceived responsibility and sophisticated strategies that they had to develop to keep both their parents and them safe and connected, exemplifying Bowen’s Family System Theory in their determination to maintain family bonds (Haefner, Citation2014).

The tenacity with which children maintained their parent–child relationships appeared to supersede the trauma they may have experienced as a result of their parent’s actions, reflecting Bowen’s Family System (Haefner, Citation2014). As Pyecroft and Bartollas (Citation2014) observe, families negotiate complex experience for the survival of their family unit as a priority. Maladaptive behaviours are accommodated and worked around as a priority to maintain their functionality. However, as children, the participants would also have had far fewer resources to draw on if they had wished to break away, being dependent on family for their basic needs. Their strategies served to both minimise the distress and/or potential triggers for the parent and to protect the family from the intervention from services which they feared as being negative and stigmatising.

Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate powerfully the influence that such a coping mechanism has into adulthood. Such implicit coping strategies continue throughout the life course, impacting on the participants’ own identities as adults and parents, thus transferring the impact of their childhood experiences across generations.

The Model of Acquiescence incorporates attachment and family systems theory, bringing a new insight into how the phenomenon starts for some children, is sustained over time and continues to impact on their adult lives. With this understanding health and social care services can seek to engage in a proactive manner to identify circumstances where the child is developing a strategy of acquiescence and seek to disrupt the cycle.

Therefore, it is crucial that supportive services take a whole family approach when considering the needs, outcomes and potential risks faced by individual family members. Whole family approaches enable often separate services such as adult mental health and children services, to work together to consider the holistic needs of the family and to acknowledge the fact that the health, wellbeing and behaviour of children and parents are interconnected (Woodman et al., Citation2020).

Using the Model of Acquiescence children who may have otherwise been seen as quietly competent can be identified. The model also enables professionals to carefully challenge children’s thought processes regarding responsibility, a process that needs to be revisited at key points throughout their development and transition into adulthood.

Limitations and future suggestions

As adults recall the past, factors such as age, memory and any experience of therapy would have influenced the way that they told these stories. However, such a biographical lens across the whole life course is extremely valuable. These interviews lasted on average 2.25 hours, and the recollections were detailed and, in most cases, still very visceral for the participants. Four participants had experienced sexual abuse in childhood. Although this experience inevitably shaped their experience and memories, the abuse was not perpetrated by a parent, and during the interviews they focused their recollection on the vulnerability of their parent and their lack of protective oversight. Insights from this study can be used to support future research and intervention with children living in these circumstances now.

Author contributions

Kate Blake-Holmes was the primary investigator and devised the Model of Acquiescence. Emma Maynard and Marian Brandon contributed their expertise and specific theoretical perspectives. The paper was written 80% by Kate Blake-Holmes, 20% by Emma Maynard. Marian Brandon advised and edited the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2019). Young adult carers: The impact of caring on health and education. Children & Society, 33(4), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12310

- Blake-Holmes, K. (2019). Young adult carers: Making choices and managing relationships with a parent with a mental illness. Advances in Mental Health, 18(3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2019.1636691

- Blake-Holmes, K., & McGowan, A. (2022). ‘It’s making his bad day into my bad days’: The impact of coronavirus social distancing measures on young carers and young adult carers in the United Kingdom. Child & Family Social Work, 27(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12877

- Borchet, J., Lewandowska-Walter, A., & Rostowska, T. (2018). Performing developmental tasks in emerging adults with childhood parentification – Insights from literature. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 6(3), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.5114/cipp.2018.75750

- Brandon, M., Belderson, P., Sorenson, P., & Dickens, J. (2020). Complexity and challenge: A triennial analysis of SCRs 2014-2017. Department for Education.

- Gough, G., & Gulliford, A. (2020). Resilience amongst young carers: Investigating protective factors and benefit-finding as perceived by young carers. Educational Psychology in Practice, 36(2), 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2019.1710469

- Haefner, J. (2014). An application of Bowen family systems theory. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(11), 835–841. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.921257

- Hamilton, M., & Adamson, E. (2013). Bounded agency in young carers’ lifecourse-stage domains and transitions. Journal of Youth Studies, 16(1), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.710743

- Hendricks, B., Vo, B., Nicholas Dionne-Odom, J., & Bakitas, M. (2021). Parentification among young carers: A concept analysis. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 38(5), 519–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00784-7

- Hooper, L. (2007). The application of attachment theory and family systems theory to the phenomenon of parentification. The Family Journal: Counselling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 15(3), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480707301290

- Howe, D. (2005). Child abuse and neglect. Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire.

- Jankowski, P., Hooper, L., Sandage, S., & Hannah, N. (2013). Parentification and mental health symptoms, mediator effects of perceived unfairness and differentiation of self. Journal of Family Therapy, 35(1), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2011.00574.x

- McCormack, L., White, S., & Cuenca, J. (2017). A fractured journey of growth: Making meaning of a ‘broken’ childhood and parental mental ill-health. Community, Work & Family, 20(3), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2015.1117418

- Mowbray, C. T., & Oyserman, D. (2003). Substance abuse in children with mental illness: Risks, resiliency, and best prevention practices. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 23(4), 451–482. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022224527466

- Munro, E. (2011). The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final report. (Cm 8062) The Stationery Office.

- Nolte, L. (2013). Becoming visible: The impact of parental mental health difficulties on children. In R. Loshak (Ed.), Out of the mainstream. Helping children of parents with a mental illness (pp. 31–44). Routledge.

- Padgett, D. (2017). Qualitative methods in social work research (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Pillow, W. (2003). Confession, catharsis or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as a methodological power in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 16(2), 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839032000060635

- Pyecroft, A., & Bartollas, C. (2014). Applying complexity theory: Whole systems approaches to criminal justice and social work. Policy Press.

- Reupert, A., & Maybery, D. (2009). Guest editorial: Practice, policy and research: Families where a parent has a mental illness. Advances in Mental Health, 8(3), 210–214. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.8.3.210

- Reupert, A., & Maybery, D. (2016). What do we know about families where parents have a mental illness? A systematic review. Child & Youth Services, 37(2), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2016.1104037

- Riessman, C. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- Rutter, M. (2013). Annual research review: Resilience – clinical implications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02615.x

- Tyler, I. (2020). Stigma: The machinery of inequality. Zed Books.

- Warhurst, A., Bayless, S., & Maynard, E. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of supporting young carers in schools: Identifying support needs and the importance of home-school relationships. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710755

- Wengraf, T. (2001). Qualitative research interviewing: Biographical narrative and semi structured methods. Sage.

- Woodman, J., Simon, A., Hauari, H., & Gilbert, R. (2020). A scoping review of ‘think-family’ approaches in healthcare settings. Journal of Public Health, 42(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdy210