ABSTRACT

Objective

Given the potential benefits of digital mental health (DMH) interventions, especially post-COVID-19, ample research focuses on factors that prevent mental health professionals (MHPs) and consumer engagement with DMH technologies. However, questions about the robustness of research designs employed to study DMH barriers remain unanswered. This review aimed to identify methodological approaches to identifying barriers to DMH use.

Method

Using PRISMA-SCr guided scoping review methodology, the research methods and designs used to study barriers to DMH use among MHPs and consumers were investigated. Four databases were searched using broad terms to identify articles that focused on exploring barriers to DMH use by MHPs and consumers, covering screening, assessment, diagnosis, therapy, counselling, and treatment of mental health issues.

Results

One hundred and forty-seven papers met the inclusion criteria. Ninety-six studies were qualitative, 25 were quantitative, and 25 were mixed methods. There were 66 consumer studies, 62 MHP studies, and 19 studies included both. Hundred and eight studies were published between 2017 and 2021, focusing on developed nations such as the USA, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

Discussion

There is increasing interest in the barriers to DMH use, with more research employing qualitative designs to identify DMH use barriers. Consensus regarding key terms and definitions; reliable and valid tools to measure DMH use barriers; and increased efforts to test specific DMH tools in more than one setting are needed to enable a better understanding of factors that influence MHPs’ and consumers’ use of DMH.

A scoping review of methodological approaches to investigating barriers using digital mental health (DMH) interventions

The use of technology to support mental health care is becoming increasingly feasible due to the ubiquity and affordability of technological devices in society, widely available internet, and consumer comfort with technology. Technology assisted mental health service delivery is referred to as DMH (Balcombe & De Leo, Citation2021). Computers, mobile phones, and virtual reality devices to deliver psychological therapies, assessments, homework, reminders, and counselling services are some examples of DMH. These DMH services range from self-help tools to those that serve as adjuncts to traditional face-to-face mental health services and have enormous potential to deliver efficient care to consumers (Cuijpers et al., Citation2015; Hilty et al., Citation2017; Karyotaki et al., Citation2017). DMH may save time, cost (Lintvedt et al., Citation2013), and resources while overcoming stigma-related treatment concerns (Gowen, Citation2013).

The use of DMH has shown positive treatment outcomes for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Kuester et al., Citation2016; Sijbrandij et al., Citation2016; Simblett et al., Citation2017; Stefanopoulou et al., Citation2020), depression and anxiety (Andrews et al., Citation2018), eating disorders (Aardoom et al., Citation2013; Anastasiadou et al., Citation2018; Dölemeyer et al., Citation2013; Linardon et al., Citation2020), problem drinking (Riper et al., Citation2011), and smoking cessation (Graham et al., Citation2016). Reviews (Andersson et al., Citation2014; Davies et al., Citation2014; Firth et al., Citation2017; Moshe et al., Citation2021) show that effect sizes of DMH, especially those with human support, are comparable to face-to-face care for common mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety. Consequently, pre-COVID-19, considerable attention was given to implementation strategies by governments and institutions across the globe to increase the use of DMH in routine care (Ganapathy et al., Citation2021). However, many researchers noted that the actual use of DMH by consumers and MHPs was less than optimal (Anastasiadou et al., Citation2019; Breedvelt et al., Citation2019; Carper et al., Citation2013; Ebert et al., Citation2015; Jzerman et al., Citation2019; Newman et al., Citation2016), with consumer and MHP attitudes often cited as a barrier to implementation.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent changes to service delivery models provided the impetus to overcome MHP and consumers’ attitudinal barriers and myths that challenged technology use in routine mental health care (Wind et al., Citation2020; Torous et al., Citation2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, DMH aided service delivery through the provision of care from a distance, resulting in increased use of digital technologies in mental health care across the globe (Gratzer et al., Citation2021). A recent systematic review of the impact of COVID-19 on global delivery of mental health services showed that virtual methods of care delivery across Asia, Australia, Europe, Northern, Central and South America grew steadily during the beginning of the pandemic and resulted in almost complete virtualisation of care by the end of the first year of COVID-19 (Zangani et al., Citation2022). As Gratzer et al. (Citation2021) noted, perhaps psychiatry is experiencing its ‘digital moment'.

As the world emerges from the pandemic there is a growing realisation that a global mental health crisis is impending (Gavin et al., Citation2020; Kumar & Nayar, Citation2021), because of increased prevalence of mental health concerns and reduced funding and resourcing of traditional mental health services. In navigating these challenges, DMH will become integral to delivering efficient care and meeting the higher demands for mental health services. As such, there is a need to understand the barriers which may impede uptake and ongoing engagement in DMH by both consumers and practitioners.

Barriers to DMH use

One common approach to understanding the factors which may prevent help-seeking is to investigate the common barriers to care experienced by individuals. Qualitative (Krog et al., Citation2018; Titzler et al., Citation2018; Town et al., Citation2017; Williams et al., Citation2020) and quantitative (Perry et al., Citation2019; Sreejith & Menon, Citation2019; Stiles-Shields et al., Citation2017) studies have explored mental health professional (Buckman et al., Citation2021; De Witte et al., Citation2021; Feijt et al., Citation2018) and consumer (Bleyel et al., Citation2020; Carolan & De Visser, Citation2018; Choi et al., Citation2015; Clough et al., Citation2019; Lipschitz et al., Citation2019) reported barriers to DMH use with the goal of increasing uptake of DMH in routine care. Some widely reported barriers in the field for consumers and MHPs are the limited availability of technology, access to reliable internet, and costs and efforts involved for services in transitioning to DMH (Schueller & Torous, Citation2020). Issues such as lack of awareness and knowledge on the part of MHPs regarding available DMH programs and the concerns about effects of DMH on the therapeutic alliance (Ganapathy et al., Citation2021) also serve as challenges to their use.

The successful long-term implementation of DMH approaches will be dependent on designers and healthcare systems developing interventions and strategies to overcome both consumer and MHP barriers to DMH use. Inherent to this is a thorough understanding of these barriers and the capacity to accurately and validly identify both consumer and MHP reported barriers. Whilst valid tools exist for the measurement of barriers to face-to-face services such as the Perceived Barriers to Psychological Treatment (Mohr et al., Citation2010), the state and quality of barrier measurement within DMH use is unknown. A review of these strategies will assist MHPs, services, and policy makers in understanding and making informed choices about the available approaches for measuring and understanding barriers to DMH use within their desired populations.

The present paper aimed to conduct a scoping review methodology to explore the measurement and investigation of DMH barriers reported by MHPs and consumers. While several reviews provide information about barriers to DMH (Borghouts et al., Citation2021; Ganapathy et al., Citation2021; Wies et al., Citation2021), a comprehensive evaluation of the methodological status of this field is required. To examine this question, the present review examined the research designs employed, operational terms, the tools used to identify barriers, and the psychometric strength of these tools to gauge the robustness of findings from DMH barrier studies. Other characteristics, such as the countries and populations of study were also examined to highlight trends in DMH barrier research, as well as generalisability of findings. The goal of this paper was to provide clinicians and researchers with a basis for understanding issues of implementation in the field, as well as direction for improving implementation in the future. The review was guided by the question: What is the nature of research methods and designs that are used in DMH barrier studies?

Method

This review employed a PRISMA-SCR (Tricco et al., Citation2018) guided scoping review methodology. The protocol for the review was pre-registered with the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/CB6YN). This method was chosen for three reasons. First, the number of studies exploring barriers to DMH use has rapidly increased over time, and a preliminary examination of the literature suggested that the evidence in the field was diverse (varied in methodology, theoretical framework, and DMH studied). Scoping reviews are considered appropriate to map evidence when fields are rapidly developing and comprise diverse research methods (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010). Second, scoping reviews are useful when examining the range and nature of research (Daudt et al., Citation2013) which was a primary aim in this review. Further, our focus was to comprehend the state of the literature that existed in studying barriers to DMH use and scoping reviews are identified as a useful method for answering such questions (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005). Third, we aimed to understand the key concepts covered by the DMH barrier literature to date, and the scoping review provides a method for identifying such concepts.

Search strategy

An information specialist was consulted in developing the key terms and identifying the best databases for the review. Broad terms and minimum limits were used to identify all relevant publications. The first author conducted a search of PubMed using key terms for (1) internet and technology, which were combined with (2) mental health, and (3) barriers (see additional file 1) to identify relevant papers. The search was conducted in September 2021 and no start date was specified in the search field. A similar search was conducted across EMBASE, CINHAL, and Scopus using the necessary modifications for each database. These databases were selected as they are prominent sources of biomedical, healthcare, and nursing research, and were deemed appropriate for the present topic. By including Scopus, any potential papers published in technology-related journals were also included in the search. Lastly, citations from relevant reviews were examined and references lists of included articles were hand searched to identify any relevant papers.

Selection of sources of evidence

Inclusion criteria for the review were (1) the article was an empirical study, (2) published in English, (3) explored barriers or challenges, (4) focussed on the use of digital technology, and (5) focussed on technology use in mental health fields such as assessment, diagnosis, therapy, counselling, and treatment. Articles were excluded if they reported on barriers as lessons learned by researchers in the context of efficacy studies; non-empirical papers, such as research protocols, letters to editors, and opinion pieces; were primarily focussed on physical illness, and literature reviews.

This review placed no limits on the population studied or any mental disorder for two reasons. First, the focus was on understanding the range of evidence in DMH barrier studies and placing such limits would not result in comprehensive findings. Second, guidelines for conducting scoping reviews suggest that both the breadth and depth of the evidence in the field should be addressed (Peters et al., Citation2015). Thus, placing restrictions on population and type of mental disorder would limit the scope of the review.

To ensure the quality and relevance of the articles included in the study, a comprehensive screening process was conducted. AG deleted all duplicates and reviewed the titles and abstracts to exclude those that were not related to mental health and technology. EndNote 20 (Version EndNote Citation20) reference management software was utilised to facilitate this process, with keywords that were clearly unrelated to the topic (e.g. economics, epidemiology, physiotherapy, mammogram, rheumatic, genotyping) being excluded using its advanced search functions. Any excluded titles were logged in a Microsoft Excel worksheet, and author DR performed random checks (n = 252) to verify the reliability of the screening. There were no discrepancies between authors.

AG then screened all full-text articles and DR screened 53.97% of the full-text articles against the inclusion criteria. The rate of agreement between authors was 83.91% for study inclusions. All disagreements were first discussed between AG and DR and, for when differences between reviewers remained unresolved, authors LC and BC independently reviewed the articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with a consensus then reached between the team.

Data extraction and charting

Data extraction and charting are best approached as an iterative process in a scoping review (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005). Discussions about data extraction and charting were conducted during the three stages of the review. First, during the planning stage, AG, LC, and BC discussed the variables necessary for the research question and the relevant data to be extracted. The discussion resulted in the authors creating a standardised data charting form. Data from five studies were then extracted by AG and DR to test the charting form, with inter-rater agreement at this step being 85.71%. This was followed by a second round of discussions between AG, DR, LC, and BC to review the form, with revisions made to increase clarity and specificity regarding extracted data. The key data extracted in the final charting form included:

publication information (authors, year of publication, study location)

key terms used for DMH

DMH characteristics (technology used, DMH modality, particular name of DMH, targeted mental disorder)

population and sample characteristics (population studied, sample size, gender, age, mental health issue, experience using DMH)

research design (e.g. quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods)

data collection method (face-to-face, online, telephone, postal or videoconferencing)

theoretical frameworks used

tool characteristics (name of the tool, reliability, validity).

Overall, AG extracted data from 88 studies, ABG extracted data from 30 studies, and KVS extracted data from 30 studies. Levac et al. (Citation2010) recommend that a second reviewer independently perform the extraction and charting of data on 10 studies to increase the objectivity of this step. Since 10 studies accounted for a very small proportion of total included studies, a total of 20% of all included studies were checked for objectivity. The agreement rate between the authors ranged between 87.62% and 93.25%.

After the extraction stage, another discussion was conducted between the authors to resolve disagreements and to check for any needed data charting revisions. This step resulted in consensus regarding disagreements in the extracted data, with no further changes deemed necessary for the data charting form.

Synthesis of results

Synthesis of results included a descriptive and narrative approach. The charted data were first analysed using frequencies followed by a narrative synthesis by AG. As is typical with scoping reviews (Abd-Alrazaq et al., Citation2019; Balcombe & Diego, Citation2022; Shatte et al., Citation2019), the extracted data guided the main points of the synthesis. The results were then discussed between AG, LC, and BC until a comprehensive understanding of the field was attained.

Results

Search results

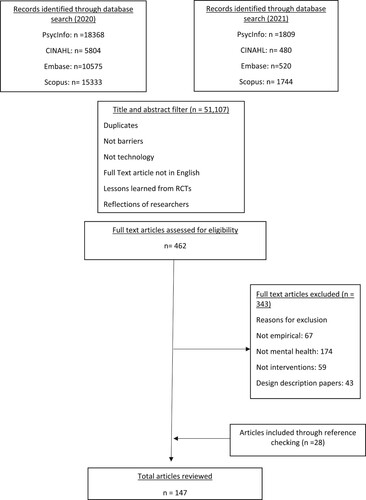

Initial database searches were performed in June 2020 and were updated in September 2021. The search resulted in 54,633 unique publications. Title and abstract screening by AG resulted in 462 studies for full-text screening. After full-text screening, 119 publications were identified as suitable for review, and 28 articles were added via the reference lists of identified articles (see ). Overall, the review included 147 unique publications.

Publication characteristics

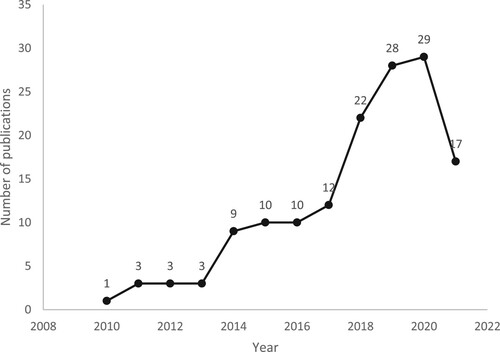

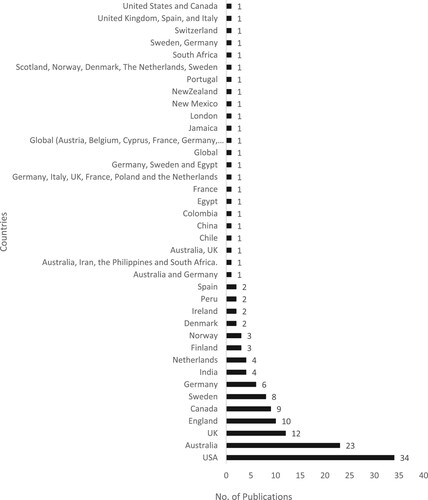

The included studies were published between 2010 and 2021, with more DMH barrier studies published in the last five years. One hundred and eight studies (73.5%) were published between 2017 and 2021 and 39 studies (26.5%) were published between 2010 and 2016. In 2019 alone, 32 studies (21.76%) were published in this area (refer to ). Studies were primarily conducted in Western countries, with the highest number of publications originating from the USA (n = 34; 23.12%), followed by Australia (n = 23; 15.64%), the UK (n = 12; 8.16%), England (n = 10; 6.80%), and Canada (n = 9; 6.12%). Ten studies included samples from more than one nation (refer to ).

Key terms

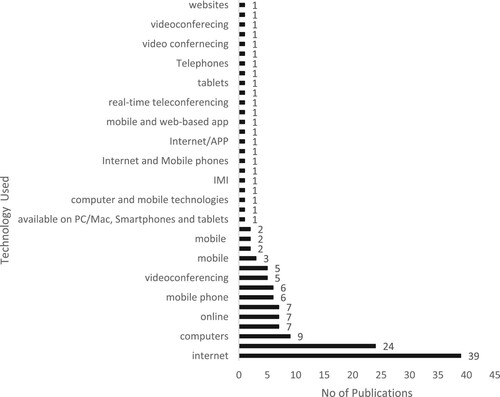

A range of terms were used to refer to DMH (see ). Eighty-six unique terms falling into eleven categories (internet, online, web, mobile, tele, technology, computer, video, guided, digital, blended) were used. There were also eight terms that did not fit any of the mentioned categories. A comparison year-wise and location-wise yielded no specific trends in where and when these terms were used. However, more authors used ‘internet' (n = 27; 18.36%) -related key terms to refer to DMH. Other key terms that were popular included ‘digital’ (n = 20; 13.60%) and ‘mobile' (n = 19; 12.92%)-related terms.

Table 1. Key terms used to refer to DMH, their categories, and number of publications using the key terms.

Capturing DMH

The flexibility of technology has resulted in a plethora of options for how and when technology can be included in care delivery, resulting in numerous kinds of DMH. Two common ways to categorise the various DMH options available relate to the technology used (mobile phones, computers, virtual reality, websites, etc.) and the modality of support (self-help, adjunct, and human supported).

Technology used

A common method of categorising DMH has been to refer to the technology (e.g. computers, mobile phones, tabs, virtual reality devices, etc.) that supports the intervention. Unique barriers may be faced in using these different technologies (e.g. accessibility of mobile phones versus accessibility of personal computer). In studying barriers to DMH use, more studies focussed on understanding barriers to the use of a particular technology (see ), such as computers, the internet, websites, or mobile phones, as opposed to barriers to the use of DMH in general (n = 24; 16.32%). Studies exploring barriers to specific technology use focussed on the internet (n = 42; 28.57%), mobile/smart phones (n = 30; 20.40%), computers (n = 9, 6.12%), video conferencing (n = 8; 5.44%), websites (n = 8; 5.44%), online (n = 7, 4.76%), tablet (n = 3; 2.04%), and other technologies used for mental health (refer to ).

Table 2. Publication, DMH, and sample characteristics.

DMH modality

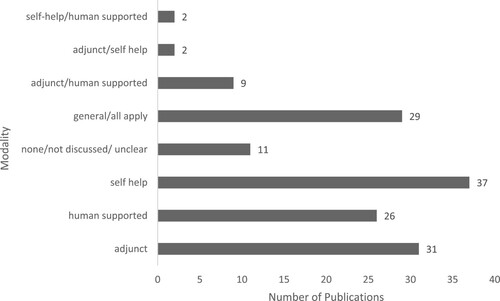

The second key method of categorising DMH has been to refer to its mode of support. DMH can be used with or without practitioner involvement. As a pure self-help tool, DMH can be used as self-directed intervention with no practitioner involvement. DMH can also be categorised as human supported DMH or adjunct DMH. While both adjunct and human supported DMH involve practitioners, they differ in the amount of practitioner and DMH involvement. In human supported DMH, the DMH tool is the chief intervention, and the practitioner plays a smaller role of support/check in, etc. In the adjunct, the usual face-to-face therapy method is used and technology is just a support. Therefore, in the adjuncts the practitioner plays the chief role. These varying degrees of practitioner and technology support may influence the barriers faced in using DMH interventions.

In many studies (n = 37; 25.17%), DMH was defined as a self-help program. DMH served as an adjunct to face-to-face therapy in 31 studies (21.08%) and in a further 26 studies (17.68%), DMH was human supported. In 29 studies, DMH was defined as generally including all three modes, that is, adjunct, human supported, and self-help.

Not all studies clearly defined the modality of the DMH. In some studies, the definition of DMH provided by the authors did not clarify whether it was an adjunct or human supported mode (n = 9; 6.12%), and in others, it was not possible to clearly categorise DMH as an adjunct or self-help (n = 2; 1.36%). In some, it was not clear if the DMH was self-help or human supported (n = 2; 1.36%) from the definition provided by authors of the study. Last, in 11 studies (7.48%) DMH could not be classified into any of the models since the authors did not clearly define the role of DMH (refer to ).

Specific DMH programs

Barriers to DMH use have been explored for specific DMH programs and for DMH in general. The majority of included studies (n = 75; 51.02%) explored barriers to the use of specific DMH tools such as WellWave, MoodGym, PE Coach, and MamaMia (refer to ). However, no DMH was noticeably more frequently examined among barrier studies. Sixty-seven (45.57%) studies did not include a specific DMH tool, instead, they examined barriers to DMH use in general. Four studies (Titzler et al., Citation2018), (Grubaugh et al., Citation2014; Lundgren et al., Citation2018; Mitchell et al., Citation2015) focused on a particular DMH program but did not provide the specific program’s name. One study (Nicholas et al., Citation2017) defined DMH as any mobile application that was commercially available in Android Play Store and Apple iStore.

Targeted mental disorder

Researchers have explored the suitability of DMH to provide care for people with varying mental health issues and some practitioners have reported concerns in using DMH interventions especially for patients with severe mental illness (Eichenberg et al., Citation2016; Stallard et al., Citation2010). Thus, the mental symptoms targeted by the DMH tool seem to influence perceived barriers to its use. The included studies explored challenges to DMH use for various mental health symptoms and disorders, ranging from sub-threshold symptoms to severe mental illness. Ten studies (6.80%) focused on depressive disorders. Another 10 studies defined DMH as focusing on a range of disorders. Eighty-eight (59.86%) studies did not focus on any mental health issue, but rather looked at barriers to the use of DMH in general (refer to ).

Population and sample characteristics

Both consumers and MHPs are critical to successful implementation of DMH, and findings suggest that there are differences between these populations in their enthusiasm to use DMH (Gun et al., Citation2011; Kay-Lambkin et al., Citation2014; Mares et al., Citation2016). Further, sample characteristics such as age (Glueckauf et al., Citation2018; Kuhn et al., Citation2015), prior experience with technology (Gun et al., Citation2011; Perry et al., Citation2019), and severity of symptoms may influence barriers and engagement with DMH. Consequently, it is imperative to understand whether barrier studies have sufficiently focussed on the two populations and examine the characteristics of the included samples.

Population studied

Overall, 66 studies (44.89%) focused on barriers reported by consumers and 62 studies (42.17%) focussed on barriers reported by MHPs (refer to ). Nineteen studies (12.92%) included both MHPs and consumers. Studies focusing on MHPs included feedback from multiple health care stakeholders, including management staff, primary health care providers, psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists, nursing staff, social workers, therapists and psychologists in training, administration staff, and other key staff. Similar variability was evident in the types of consumers who were included in the barrier studies. Adults (74.39%), older adults (4.87%), young adults (3.65%), adolescents (9.75%), veterans (6.09%), and employee feedback (4.87%) were all populations of interest.

Age

Researchers recruited a wide range of age classifications in both MHP and consumer studies, although reporting of range, central tendency, and variability was inconsistent at times. Overall, in consumer studies, six studies used mean statistics to describe age, 59 studies reported mean and standard deviation, 23 studies reported range, 19 studies reported range with a central tendency measure (mean or median), seven studies reported ages of subsamples, and 32 studies did not report age statistics. Eight studies recruited adolescents (18 years and less), 35 studies recruited adults (18 years and above), 4 studies recruited older adults (50 years and above), 23 studies recruited both adults and older adults, and 1 study recruited adolescents and adults. One study did not report the age of the consumer participants. All MHP barrier studies focussed on adult samples of working practitioners.

Gender

A majority of all studies included in the review had a predominantly female sample, with 88 studies (59.86%) reporting samples in which women represented 50% or more of the sample. Comparatively, 21 studies (14.28%) reported samples in which males represented 50% or more of the sample. Thirty-six studies (24.48%) did not provide gender demographic information, and in two studies (3.92%), the gender information was provided for sample subgroups but not the overall sample.

More specifically, in studies that included a MHP sample, 44 studies (54.32% of all MHP studies) reported samples in which women represented 50% or more of the sample while only four studies (4.93%) reported samples in which men represented 50% or more. Similarly, of all studies including a MHP sample only five studies (6.17%) reported having an equal distribution of males and females in the sample. Twenty-five studies (30.86%) of all MHP studies did not report on the gender variable.

In studies that included a consumer sample, 51 studies (60% of all consumer studies) reported samples in which women represented 50% or more of the recruited sample while only 17 studies (20.00% of all consumer studies) reported samples in which men represented 50% or more. Similarly, of all studies including a consumer sample only two studies (2.35%) reported having an equal distribution of males and females in the sample. Eleven studies (12.94%) of all consumer studies did not report on the gender variable.

Reported mental health issues

The review included 66 consumer studies and 19 studies that included both consumers and MHPs, resulting in 85 studies that included a consumer sample. These studies reported recruiting consumer samples with a range of mental health issues (refer to ). Of all studies that recruited a consumer sample, a number of studies recruited people diagnosed with different kinds of depression (n = 15; 17.6%), anxiety (n = 3; 3.52%), bipolar disorder (n = 3; 3.52%), substance use disorders (n = 3; 3.52%), eating disorders (n = 2; 2.35%), insomnia (n = 2; 2.35%), developmental disorders (n = 1; 2.35%), and psychosis (n = 2; 2.35%). Two studies (2.35%) included samples that reported elevated levels of general distress. Eight studies (9.41%) defined their samples as being diagnosed with a wide range of mental health issues and not a specific mental health disorder. Only a small proportion of studies that included a consumer sample included people without any mental health diagnosis (n = 22; 25%).

Interestingly, some studies used self-reported questionnaires (40.38%) to inform about the mental health symptoms of the recruited participants, while others employed clinical interviews by professionals (19.23%) to confirm the diagnosis. The authors also contacted mental health professionals and health centres to recruit participants currently undergoing treatment for their mental health issues (30.76%).

Prior experience using DMH

Evidence suggests that there is a difference between the barriers reported by those who have previous experience in using DMH and those who do not have such experience (Perry et al., Citation2019). Across the DMH barrier studies, participants’ prior experience in using DMH services varied. There was also much variation in how prior experience with DMH was defined and measured. In a large number of all included studies (n = 56; 38.09%), all recruited participants had previously used DMH. Twenty-one studies (14.28%) recruited samples that included those who had previously used and those who had not previously used DMH. In these studies, which recruited users and non-users of DMH, 12 studies (8.16%) recruited a sample in which a majority were non-users, and seven studies (4.76%) recruited a sample in which a majority had used a DMH. In some studies (n = 9; 6.12%), the participants were shown a prototype or given a demonstration of the DMH, and some other studies (n = 52; 35.37%) did not record usage statistics or provide enough information to draw conclusions regarding this variable. Some other ways in which studies have recorded prior experience in using DMH includes recording general technology/device ownership (n = 2; 1.36%), being trained in DMH tools (n = 4; 2.72%) and quantifying the amount of use of DMH in previous year (n = 1; 0.68%) (refer to ).

Research design

The research methods and designs used in barrier studies need to be scrutinised to understand the generalisability and robustness of findings. The study methodology, data collection methods and sampling techniques employed provide insights on the landscape of DMH barriers research.

Methodology

DMH barrier studies primarily used a qualitative design (n = 96; 65.30%), while a smaller number of studies used quantitative methods (n = 25; 17.00%) and mixed methods (n = 25; 17.00%) designs.

Data collection methods

A large number of studies used some form of interview method (n = 60, 40.81%) to assess barriers, 59 of such studies used semi-structured interview methods, one study used the structured interview format, and one study used a combination of both. Forty-two studies (28.57%) used a survey method. Twenty-eight studies (19.04%) used a combination of data collection methods such as combining interviews with surveys, focus groups and individual interviews (refer to ).

Table 3. Research designs and methodology used in quantitative studies.

Table 4. Research designs and methodology used in Qualitative Studies.

Face-to-face data collection was the most popular (n = 58; 39.45%) method, followed by online (n = 31; 21.08%) and telephone methods (n = 13; 8.84%) of data collection. Studies utilised a combination of face-to-face with online (n = 9; 6.12%), telephone (n = 13, 8.84%), paper pencil (n = 3; 2.04%) methods and one study combined face-to-face with online and telephone methods. Seven studies (4.76%) did not provide sufficient information to determine data collection methods. A very small number of studies utilised the paper–pencil survey method (n = 6; 4.08%), a combined paper–pencil and online survey method (n = 2; 1.36%), a combination of online and telephone methods (n = 2; 1.36%), and one study used the postal method.

Theoretical orientation and models

Keeping with this review’s objectives, we explored which theories were used to guide the measurement and analysis of barriers to DMH use.

A majority of studies (80.27%; 25 qualitative studies, 18 mixed methods, 74 quantitative studies) did not use a theoretical approach to measuring or analysing barriers. Among studies that used a theoretical approach (n = 28, 19.04%), no theory was notably more popular than any other. Three studies used Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology, three studies used Consolidated Frameworks for Implementation Research, and two studies used Theoretical Domains Framework in measuring and/or in analysis of the barriers reported in the included studies (see ). Many studies (e.g. Bruno & Abbott, Citation2015; Kurki et al., Citation2011; Sinclair et al., Citation2013; Wilhelmsen et al., Citation2014) reported using theoretical frameworks to guide study objectives but did not make clear if the theory guided construction of the interview guide, survey, or the analysis of the results.

Table 5. Research designs and methodology used in mixed methods studies.

Identification of barriers

Examining how barriers to DMH use were identified or measured is of utmost importance, as it indicates the reliability and validity of findings. Additionally, it identifies the available DMH barriers scales for practitioners, consumers, and researchers.

Qualitative studies

In a large number of qualitative studies (n = 49), it is not clear what informed the interview schedules that were used to explore barriers. In studies that provided such information (n = 37), the interview schedules were developed based on: existing literature (n = 13), constructs of a theory (n = 7), experts’ input (n = 5), authors’ knowledge (n = 4), user group input (n = 2), literature and authors’ expertise (n = 1), authors’ knowledge and expert feedback (n = 1), study objectives (n = 1), and theory and experts’ feedback (n = 1). Two studies used the Theoretical Domains Framework to guide the development of the interview schedule. The other theories used to guide qualitative schedules were the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (n = 1), the Capability, Motivation and Opportunity Model (n = 1), Evidence-Based Developer Interview (n = 1), NASS Framework (n = 1), Normalisation Process Theory (n = 1), and Behavioural Model for Health Service Use (n = 1). Rather than eliciting information via a schedule, one study (Nicholas et al., Citation2017) used the consumer reviews publicly available on PlayStore and Apple iStore and another study used data from the participants’ online discussion board of the DMH tool they were using. Lastly, seven studies (Sinclair et al., Citation2013), (Andrews et al., Citation2019; Chen et al., Citation2020; Johnsson et al., Citation2019; Orlowski et al., Citation2016b; Reger et al., Citation2017; Shakespeare-Finch et al., Citation2020) did not discuss any measures or interview schedule or provide sufficient information on how the barriers were identified in the study (refer to ). In two studies identifying barriers was part of a larger study focus and hence only one or two questions in the overall interview were used to explore barriers.

Quantitative studies

Similar to qualitative studies, quantitative studies also used a wide variety of methods to construct survey tools. Constructing survey tools dependent on extant literature was a popular method (n = 9) for measuring barriers. Other frequently used methods included developing tools specifically for the studies based on; authors’ expertise and extant literature (n = 3), feedback from an advisory board (e.g. GP, academician, or DMH experts) (n = 3), literature review and feedback from advisory board (n = 2), target population feedback (n = 1), and authors’ knowledge (n = 1). Three studies used a combination of survey tools that measured constructs closely related to barriers (such as interest, attitudes, computer efficacy, technology access). Three studies provided the survey topics and survey questions but did not discuss what guided the development of these questions (refer to ).

Mixed methods studies

Mixed methods studies employed a variety of tools in measuring barriers, and no tool was more popular than another. DMH barriers were measured by tools dependent on theoretical frameworks (n = 3), literature review (n = 2), authors’ expertise and literature review (n = 1), targeted population feedback (n = 1), theoretical framework and expert feedback (n = 1). One study used one or two open-ended questions to assess barriers and two studies did not discuss how barriers were measured. Eleven studies listed the survey or interview topics but did not provide sufficient information on what guided the selection of such topics. Lastly, two studies used a combination of adhoc scales and validated measures of constructs closely related to barriers that was developed for face-to-face interventions (refer to ).

Rigour in DMH barrier studies

The scientific nature of enquiry depends on the validity and reliability of findings. Understanding what methods were employed to establish rigour in DMH barrier studies enables evaluation of the trustworthiness and dependability of conclusions drawn from them.

Qualitative studies

To explore rigour of qualitative work in the field, we utilised the widely accepted guidelines of Lincoln and Gubba (Citation1985), which emphasises that reliable and valid qualitative work depends on rigour in interpreting results. This approach proposes Indicators of rigour include confirmability (objectivity), dependability (reliability), credibility (internal validity), and transferability (external validity).

In the present review, the majority of included qualitative studies utilised analyst/coder triangulation (n = 78) methods for some or all the data for establishing credibility. Twelve of these studies provided inter-coder agreement rates. Other methods for establishing credibility included data source triangulation (n = 1), methods triangulation (n = 1), member checks (n = 16) peer debriefing (n = 13), comparing coded data and themes to informal information sources (n = 1), and logic checks (n = 2). Nine studies did not provide sufficient information to enable conclusions about credibility checks and, in one study, the interview schedule was modified after 27% of interviews were conducted. Pilot testing of the interview schedule was only performed in seven studies (refer to ).

Transferability by a description of contextual information (e.g. description of setting of the study, sample characteristics, and DMH program/intervention) was demonstrated in 78 studies. A majority of studies (n = 87) provided direct quotes from participant interviews to illustrate themes, with nine studies not providing such information. Audit Trials, peer debriefing, reflexivity and member checks were some other methods used to establish rigour. Three studies explicitly mentioned following the COREQ guidelines.

Quantitative studies

For quantitative studies, rigour was assessed through the conventional reliability and validity of tools information. Four studies reported alpha values to describe the internal consistency of the scale. Three studies reported the validity of the scales that were used in the survey by reporting their factorial structure. Twenty quantitative studies either did not discuss the validity and reliability of the measures used or used measures that did not have reliability or validity indices.

Mixed methods studies

Mixed methods studies greatly varied in the amount of information provided about how rigour was established in qualitative and quantitative parts of the study. While some studies described rigour for quantitative parts of the study, they did not discuss the same for qualitative parts (and the reverse was also true).

In three studies authors did not discuss how rigour was established for the quantitative parts, but they discussed this issue for the qualitative parts. The three studies used coder triangulation methods to establish credibility of the qualitative findings and only Titzler et al. (Citation2020) providing inter coder agreement rates for this step. All three studies also provided illustrative quotes from participants to establish dependability of the qualitative findings, while two of the studies provided detailed information on the context, participants, and intervention to account for transferability.

Another three studies discussed reliability of the quantitative parts of the study but did not discuss validity. All three studies provided detailed information about context, intervention, and participants to establish transferability and provided illustrative quotes to account for dependability of the qualitative findings. However, two of these studies undertook measures of coder triangulation and methods triangulation to ensure credibility of the qualitative findings. One study used a reliable and valid scale for the quantitative parts of the study and also accounted for rigour of qualitative findings by using coder triangulation to establish credibility, describing the intervention and project for transferability, and using illustrative quotes to establish dependability.

Salloum et al. (Citation2015), (Knechtel & Erickson, Citation2021) used analyst triangulation and member checking to establish rigour of qualitative data and for the quantitative parts of the study, a modified version of a valid and reliable scale built to assess face-to-face treatment barriers and satisfaction (Barriers to Treatment Participation Scale and Client Satisfaction Questionnaire). Drozd et al. (Citation2018) used reliable and valid scales of attributes related to barriers [The Implementation Climate Questionnaire from the Measures of Implementation Components (Fixsen et al., Citation2008); Computer-Assisted Therapy Attitudes Scale (CATAS; Becker & Jensen-Doss, Citation2013) and e-Helath Implementation toolkit (Murray et al., Citation2010)] for the quantitative findings of their research but did not discuss how rigour was established for the qualitative parts. Last, one mixed method study did not discuss how rigour was established for both, quantitative and qualitative, parts.

Discussion

This scoping review sought to identify the research designs and methodology employed by DMH barrier studies. A total of 147 articles met the inclusion criteria of the review, with a preference for qualitative rather quantitative studies observed within the literature.

DMH characteristics

This review highlights the issues of nomenclature within the field with 85 unique terms for DMH identified that could broadly be classified into 11 categories. Authors often used the terms interchangeably, and this confusion of key terms may pose significant issues for policymakers, researchers, and practitioners. It is imperative that the field undertakes concrete efforts towards defining key terms and their usage. Until such work is available, the comprehensive list of terms provided in this review may serve as a starting point for future researchers, especially for systematic reviews.

DMH barrier studies have explored the challenges of a wide variety of DMH modalities. However, rarely has the research differentiated between the barriers that may be relevant for DMH in general, DMH as adjunct, as human supported, or DMH as a self-help tool. Interestingly, despite the advancing research and increased publications in the field, few studies have enquired whether any association appears between perceived barriers and DMH modality. Future research employing such fine-grained analysis is likely to be of particular benefit for assessing the needs of users at various stages within stepped-care models of treatment, supporting implementation of these approaches to population mental healthcare.

Replicability should also be considered within this field. Among the DMH interventions discussed in this review, only a few (Camp Cope-A- Lot, Moodgym, Online Therapy Unit, Personality and Living of University Students, PTSD Coach, and Smooth Sailing) had barriers mentioned in multiple publications. This scarcity of exploration into barriers faced by DMH users across multiple publications underscores the need for a more comprehensive examination of barriers across various settings and populations. The exploration of barriers in the literature was also more heavily weighted to populations experiencing common mental health disorders, such as anxiety or depression, than lower frequency mental health disorders, such as bipolar, PTSD, alcohol and drug use, or developmental disorders. This is an oversight, particularly considering the proliferation of and funding for DMH approaches in many of these areas (e.g. PTSD, alcohol use). More research involving implementation of interventions in various settings and among severe mental ill health is essential for understanding the modifying variables that may increase or decrease a person’s DMH use.

Population and Sample Studied: Another apparent trend in the review was that the included sample in most consumer studies was comprised predominantly of female participants, potentially limiting generalisability to male and non-binary populations. However, similar overrepresentation of females cannot necessarily be treated as a source for bias in MHP studies as the mental health field is represented by predominantly female practitioners (Gavin et al., Citation2020). In studies with a consumer focus, the majority of studies recruited samples with current or a history of mental health symptoms, indicating that sufficient efforts have been undertaken to capture feedback from the targeted end users of DMH.

The accuracy of barrier perceptions among both, consumers and MHPs should also be considered in this field. Some studies recruited samples who were provided with prototypes or examples of DMH to explore potential barriers. However, whether a prototype gives participants sufficient insight regarding potential barriers to its routine use is debatable. Further, in exploring barriers, frequency of DMH use, the purpose for which participants used the tool, and the scope of prior experience is often not adequately defined and collected, with many of the included studies failing to identify the sample’s prior experience of using DMH. Future researchers might focus on higher levels of analysis of the varying influence and scope of experience in using DMH on perceptions of barriers, as it may explain the present conflicting findings regarding the role of sample characteristics (e.g. age, gender, and experience in using DMH) on attitudes and readiness to use DMH (Adler et al., Citation2014; Glueckauf et al., Citation2018; Kuhn et al., Citation2015).

Methodology

Previous research into DMH barriers has predominantly been qualitative, with a small number of quantitative and mixed methods studies. Most included studies used either only face-to-face or only technology-based recruitment of samples and very few used a combination of the two methods. The choice of a single method of participant recruitment raises questions about sample selection bias. Online studies likely exclude participants who may experience the highest barriers to treatment (e.g. lack of access to technologies or the internet), thereby underestimating population experiences of barriers to DMH. Conversely, face-to-face studies likely recruit samples that perceive greater risk of digitally delivered therapies.

A key finding was that despite most researchers choosing a qualitative method, majority failed to use a theoretical framework to identify barriers to DMH use. This finding is of significant concern since fields in which there is considerable qualitative work, research grounded in theory provide greater clarity to findings. Lastly, a few studies did not provide sufficient information on how the barriers were investigated, impacting the ability to generalise and utilise the findings from such studies.

DMH barrier measures: One aim of this paper was to identify reliable and valid tools for measuring DMH barriers. A clear limitation in this field was identified, with no reliable or valid scale for measuring DMH barriers existing. Most quantitative studies in the field developed scales (typically single use) for measuring barriers, but the reliability and validity of these scales were not always established. Qualitative studies mostly depended on interview schedules for exploring barriers. However, most qualitative studies failed to report what informed the development of these schedules. While such studies have taken measures to increase credibility of their findings by using methods such as triangulations of coders, audit checks, and member checking, a lack of clear reporting, such as the absence of agreement rates for inter-coder reliability, reduces transparency. Additionally, other less validated methods, such as including one open-ended question in a larger survey, interpreting barriers through related constructs, or adapting of scales without investigation of psychometric properties, have been used to measure barriers. Adaptation of measures of face-to-face barriers may fail to assess important DMH-specific barriers, such as comfort with technology or concerns regarding data privacy or security. These limitations in design and measurement severely hamper the strength of findings from the field.

Implications for researchers and service users

The present findings demonstrate the impact of research designs on understanding barriers to DMH use by MHPs and consumers. Researchers focused on reviews and meta-analysis would benefit from including diverse key terms for comprehensive findings. Additionally, developing a reliable and valid measure that can be used across the field can save time and prevent the repetitive designing of measures of barriers for each study. Qualitative work, grounded in theory, can provide deeper insights into the underlying reasons why DMH interventions have become routine care for some, but not for others. Practitioners can utilise the findings from this review to identify the populations that could benefit the most from DMH interventions and the unique barriers faced by specific groups. Policy makers would benefit from understanding the limitations of generalisability of findings from barrier studies when designing digital practice norms.

Limitations and future directions

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first review to explore the methods and designs used by DMH barrier studies to identify the challenges faced in using DMH interventions. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. Although the paper discussed the qualitative methods used for identifying DMH barriers and the validity and reliability of the quantitative measures used, it does not account for the content (such as focus areas of the interview guides, questions asked in surveys, items in rating scales) of the barrier measures. It is worth noting that since only papers in English were included, important findings from studies in other languages may have been missed. Additionally, the search ended in 2021, so there may be more recent updates in the field that could enhance our understanding on the topic. Future studies would benefit from analysing the overall quality of included studies. Such work would provide greater understanding regarding the trustworthiness of the present findings from the DMH barrier studies. Future studies that systematically analyse the quality, content, and applicability of barrier measures in the field would expand present knowledge of challenges to using DMH interventions and accelerate its use in routine care. It is hoped that this review will not only guide researchers, MHPs and policymaker in this area, but will also encourage increased high-quality research in this field.

Conclusion

This scoping review found that research into barriers to DMH have garnered increasing interest in recent years. Consumer and MHP studies have employed quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods to assess barriers. However, suboptimal reporting and use of unreliable tools has left major gaps in the field. Future researchers would benefit from developing consensus guidelines to agree on terminology and reporting standards.

Present knowledge of barriers is largely a consequence of the use of ad-hoc scales, modified versions of face-to-face intervention barrier measures, and measure of variables associated with barriers. While such measurement contributes to our understanding of DMH barriers, a valid and reliable measure to comprehensively assess barriers to DMH interventions is needed. Such efforts would also save repetitive efforts of researchers involved in DMH implementation studies by eliminating the need to design a new barrier tool for each DMH project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- References marked with “*” are articles reviewed.

- Aardoom, J. J., Dingemans, A. E., Spinhoven, P., & Van Furth, E. F. (2013). Treating eating disorders over the internet: A systematic review and future research directions. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(6), 539–552. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22135

- Abd-Alrazaq, A. A., Alajlani, M., Alalwan, A. A., Bewick, B. M., Gardner, P., & Househ, M. (2019). An overview of the features of chatbots in mental health: A scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 132, 103978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.103978

- *Adkins, E. C., Zalta, A. K., Boley, R. A., Glover, A., Karnik, N. S., & Schueller, S. M. (2017). Exploring the potential of technology-based mental health services for homeless youth: A qualitative study. Psychological Services, 14(2), 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000120

- *Adler, G., Pritchett, L. R., Kauth, M. R., & Nadorff, D. (2014). A pilot project to improve access to Telepsychotherapy at rural clinics. Telemedicine and e-Health, 20(1), 83–85. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2013.0085

- *Adrian, M., Coifman, J., Pullmann, M. D., Blossom, J. B., Chandler, C, Coppersmith, G., Thompson, P., & Lyon, A. R. (2020). Implementation determinants and outcomes of a technology-enabled service targeting suicide risk in high schools: Mixed methods study. JMIR Mental Health, 7(7), e16338. https://doi.org/10.2196/16338

- Allan, S., Bradstreet, S., Mcleod, H., Farhall, J., Lambrou, M., Gleeson, J., & Gumley, A. (2019). Developing a hypothetical implementation framework of expectations for monitoring early signs of psychosis relapse using a mobile app: Qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(10), e14366.

- *Anastasiadou, D., Folkvord, F., & Lupiañez-Villanueva, F. (2018). A systematic review of mHealth interventions for the support of eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(5), 394–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2609

- Anastasiadou, D., Folkvord, F., Serrano-Troncoso, E., & Lupiañez-Villanueva, F. (2019). Mobile health adoption in mental health: User experience of a mobile health app for patients with an eating disorder. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 7(6), e12920.

- Andersson, G., Cuijpers, P., Carlbring, P., Riper, H., & Hedman, E. (2014). Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 13(3), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20151

- Andrews, G., Basu, A., Cuijpers, P., Craske, M. G., McEvoy, P., English, C. L., & Newby, J. M. (2018). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 55, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001

- *Andrews, J. A., Brown, L. J. E., Hawley, M. S., & Astell, A. J. (2019). Older adults’ perspectives on using digital technology to maintain good mental health: Interactive group study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(2). https://doi.org/10.2196/11694

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- *Armstrong, C. C., Odukoya, E. J., Sundaramurthy, K., & Darrow, S. M. (2021). Youth and provider perspectives on behavior-tracking mobile apps: Qualitative analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.2196/24482

- *Arnold, C., Williams, A., & Thomas, N. (2020). Engaging with a web-based psychosocial intervention for psychosis: Qualitative study of user experiences. JMIR Mental Health, 7(6). https://doi.org/10.2196/16730

- *Ashford, M. T., Olander, E. K., Rowe, H., Fisher, J. R. W., & Ayers, S. (2018). Feasibility and acceptability of a web-based treatment with telephone support for postpartum women with anxiety: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(4),e9106.

- Balcombe, L., & De Leo, D. (2021). Digital mental health amid COVID-19. Encyclopedia, 1(4), 1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia1040080

- Balcombe, L., & Diego, D. L. (2022). Evaluation of the use of digital mental health platforms and interventions: Scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010362

- *Barnett, M. L., Sigal, M., Green Rosas, Y., Corcoran, F., Rastogi, M., & Jent, J. F. (2021). Therapist experiences and attitudes about implementing internet-delivered parent-child interaction therapy during COVID-19. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 28(4), 630–641.

- *Becker, E. M., & Jensen-Doss, A. (2013). Computer-assisted therapies: Examination of therapist-level barriers to their use. Behavior Therapy, 44(4), 614–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.05.002

- *Bengtsson, J., Nordin, S., & Carlbring, P. (2015). Therapists’ experiences of conducting cognitive behavioural therapy online vis-a-vis face-to-face. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(6), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1053408

- *Berry, N., Bucci, S., & Lobban, F. (2017). Use of the internet and mobile phones for self-management of severe mental health problems: Qualitative study of staff views. JMIR Mental Health, 4(4), e52. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.8311

- *Berry, N., Lobban, F., & Bucci, S. (2019). A qualitative exploration of service user views about using digital health interventions for self-management in severe mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1979-1

- *Bleyel, C., Hoffmann, M., Wensing, M., Hartmann, M., Friederich, H.-C., & Haun, M. W. (2020). Patients’ perspective on mental health specialist video consultations in primary care: Qualitative preimplementation study of anticipated benefits and barriers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2196/17330

- *Boggs, J. M., Beck, A., Felder, J. N., Dimidjian, S., Metcalf, C. A., & Segal, Z. V. (2014). Web-based intervention in mindfulness meditation for reducing residual depressive symptoms and relapse prophylaxis: A qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(3), e87. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3129

- *Bohleber, L., Crameri, A., Eich-Stierli, B., Telesko, R., & von Wyl, A. (2016). Can we foster a culture of peer support and promote mental health in adolescence using a web-based app? A control group study. JMIR Mental Health, 3(3), e45. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5597

- Borghouts, J., Eikey, E., Mark, G., De Leon, C, Schueller, S.M., Schneider, M, Stadnick, N., Zheng, K., Mukamel, D., & Sorkin, D. H. (2021). Barriers to and facilitators of user engagement with digital mental health interventions: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(3), e24387. https://doi.org/10.2196/24387

- *Brandt, L. R., Hidalgo, L., Diez-Canseco, F., Araya, R., Mohr, D. C., Menzes, P. R, & Miranda, J. J. (2019). Addressing depression comorbid With diabetes or hypertension in resource-poor settings: A qualitative study about user perception of a nurse-supported smartphone App in Peru. JMIR Mental Health, 6(6), e11701. https://doi.org/10.2196/11701

- *Brantnell, A., Woodford, J., Baraldi, E., van Achterberg, T., & von Essen, L. (2020). Views of implementers and nonimplementers of internet-administered cognitive behavioral therapy for depression and anxiety: Survey of primary care decision makers in Sweden. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8). https://doi.org/10.2196/18033

- *Breedvelt, J. J. F., Zamperoni, V., Kessler, D., Riper, H., Kleiboer, A.M., Elliott, I., & Bockting, C. L. (2019). GPS’ attitudes towards digital technologies for depression: An online survey in primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 69(680), e164–e170. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X700721

- *Bruno, R., & Abbott, J. A. M. (2015). Australian health professionals’ attitudes toward and frequency of use of internet supported psychological interventions. International Journal of Mental Health, 44(1), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2015.1009784

- *Bucci, S., Berry, N., Morris, R., Berry, K., Haddock, G., Lewis, S., & Edge, D. (2019). They are not hard-to-reach clients. We have just got hard-to-reach services. Staff views of digital health tools in specialist mental health services. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 344.

- *Buckman, J. E. J., Saunders, R., Leibowitz, J., & Minton, R. (2021). The barriers, benefits and training needs of clinicians delivering psychological therapy via video. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 49(6), 696–720.

- *Burchert, S., Alkneme, M. S., Bird, M., Carswell, K., Cuijpers, P., Hansen, P., Heim, E., Harper Shehadeh, M., Sijbrandij, M., Van't Hof, E., & Knaevelsrud, C. (2018). User-centered app adaptation of a low-intensity E-mental health intervention for Syrian refugees. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 663. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00663

- *Cardenas, P., Bartels, S. M., Cruz, V., Gáfaro, L., Uribe-Restrepo, J. M., Torrey, W. C., Castro, S. M., Cubillos, L., Williams, M. J., Marsch, L. A., Oviedo-Manrique, D. G., & Gómez-Restrepo, C. (2020). Perspectives, experiences, and practices in the use of digital information technologies in the management of depression and alcohol use disorder in health care systems in Colombia. Qualitative Health Research, 30(6), 906–916. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320902460

- *Carolan, S., & De Visser, R. O. (2018). Employees’ perspectives on the facilitators and barriers to engaging with digital mental health interventions in the workplace: Qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(1), e9146.

- Carper, M. M., McHugh, R. K., & Barlow, D. H. (2013). The dissemination of computer-based psychological treatment: A preliminary analysis of patient and clinician perceptions. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 40(2), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-011-0377-5

- *Chan, C., West, S., & Glozier, N. (2017). Commencing and persisting with a web-based cognitive behavioral intervention for insomnia: A qualitative study of treatment completers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(2), e37. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5639

- *Chen, A. T., Slattery, K., Tomasino, K. N., Rubanovich, C. K., Bardsley, L. R., & Mohr, D. C. (2020). Challenges and benefits of an internet-based intervention with a peer support component for older adults with depression: Qualitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e17586.

- *Choi, I., Sharpe, L., Li, S., & Hunt, C. (2015). Acceptability of psychological treatment to Chinese- and Caucasian-Australians: Internet treatment reduces barriers but face-to-face care is preferred. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology: The International Journal for Research in Social and Genetic Epidemiology and Mental Health Services, 50(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0921-1

- *Clough, B. A., Zarean, M., Ruane, I., Mateo, N. J., Aliyeva, T. A., & Casey, L. M. (2019). Going global: Do consumer preferences, attitudes, and barriers to using e-mental health services differ across countries? Journal of Mental Health, 28(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1370639

- Cochrane, L. J., Olson, C. A., Murray, S., Dupuis, M., Tooman, T., & Hayes, S. (2007). Gaps between knowing and doing: Understanding and assessing the barriers to optimal health care. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 27(2), 94–102.

- *Connolly, S. L., Miller, C. J., Koenig, C. J., Zamora, K. A., Wright, P. B., Stanley, R. L., & Pyne, J. M. (2018). Veterans’ attitudes toward smartphone app use for mental health care: Qualitative study of rurality and age differences. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(8), e10748.

- *Cowie, M. E., Huguet, A., Moore, C., McGrath, P. J., Rao, S., Wozney, L., Kits, O., & Stewart, S. H. (2019). Internet-based behavioral activation program for depression and problem gambling: Lessons learned from stakeholder interviews. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 579–594.

- *Crane, M. E., Phillips, K. E., Maxwell, C. A., Norris, L. A., Rifkin, L. S., Blank, J. M., Sorid, S. D., Read, K. L., Kendall, P. C., & Frank, H. E. (2021). A qualitative examination of a school-based implementation of computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy for child anxiety. School Mental Health, 13(2), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09424-y

- Cuijpers, P., Riper, H., & Andersson, G. (2015). Internet-based treatment of depression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 4, 131–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.026

- Daudt, H., van Mossel, C., & Scott, J. S. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Davies, E. B., Morriss, R., & Glazebrook, C. (2014). Computer-delivered and web-based interventions to improve depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being of university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(5), e130. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3142

- *Dederichs, M., Weber, J., Pischke, C. R., Angerer, P., & Apolinário-Hagen, J. (2021). Exploring medical students’ views on digital mental health interventions: A qualitative study. Internet Interventions, 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100398

- *De Witte, N. A. J., Carlbring, P., Etzelmueller, A., Nordgreen, T., Karekla, M., Haddouk, L., Belmont, A., Øverland, S., Abi-Habib, R., Bernaerts, S., Brugnera, A., Compare, A., Duque, A., Ebert, D. D., Eimontas, J., Kassianos, P. K., Salgado, J., Schwedtfeger, A., Tohme, P., … Van Daele, T. (2021). Online consultations in mental healthcare during the COVID-19 outbreak: An international survey study on professionals’ motivations and perceived barriers. Internet Interventions, 25, 100405.

- *Diez-Canseco, F., Toyama, M., Ipince, A., Perez-Leon, S., Cavero, V., Araya, R., & Miranda, J. J. (2018). Integration of a technology-based mental health screening program into routine practices of primary health care services in Peru (The Allillanchu project): Development and implementation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(3), e100. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9208

- *Dodd, A. L., Mallinson, S., Griffiths, M., Morriss, R., Jones, S. H., & Lobban, F. (2017). Users’ experiences of an online intervention for bipolar disorder: Important lessons for design and evaluation. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 20(4), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102754

- Dölemeyer, R., Tietjen, A., Kersting, A., & Wagner, B. (2013). Internet-based interventions for eating disorders in adults: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-207

- *Donkin, L., & Glozier, N. (2012). Motivators and motivations to persist with online psychological interventions: A qualitative study of treatment completers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(3), e91. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2100

- *Drozd, F., Haga, S. M., Lisoy, C., & Slinning, K. (2018). Evaluation of the implementation of an internet intervention in well-baby clinics: A pilot study. Internet Interventions, 13, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.04.003

- Ebert, D. D., Berking, M., Cuijpers, P., Lehr, D., Pörtner, M., & Baumeister, H. (2015). Increasing the acceptance of internet-based mental health interventions in primary care patients with depressive symptoms. A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 176, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.056

- Eichenberg, C., Grabmayer, G., & Green, N. (2016). Acceptance of serious games in psychotherapy: An inquiry into the stance of therapists and patients. Telemedicine and e-Health, 22(11), 945–951. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2016.0001

- *Eisner, E., Drake, R. J., Berry, N., Barrowclough, C., Emsley, R., Machin, M., & Bucci, S. (2019). Development and long-term acceptability of ExPRESS, a mobile phone app to monitor basic symptoms and early signs of psychosis relapse. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(3), e11568.

- *Elison, S., Ward, J., Davies, G., Lidbetter, N., Hulme, D., & Dagley, M. (2014). An outcomes study of eTherapy for dual diagnosis using breaking free online. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 7(2), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/ADD-11-2013-0025

- *Espinosa, H. D., Carrasco, Á., Moessner, M., Cáceres, C., Gloger, S., Rojas, G., Perez, J.C., Vanegas, J., Bauer, S., & Krause, M. (2016). Acceptability study of “Ascenso": An online program for monitoring and supporting patients with depression in Chile. Telemedicine and e-Health, 22(7), 577–583. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2015.0124

- *Feijt, M., De Kort, Y., Bongers, I., Bierbooms, J., Westerink, J., & Ijsselsteijn, W. (2020). Mental health care goes online: Practitioners’ experiences of providing mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(12), 860–864. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0370

- *Feijt, M. A., De Kort, Y. A. W., Bongers, I. M. B., & Ijsselsteijn, W. A. (2018). Perceived drivers and barriers to the adoption of eMental health by psychologists: The construction of the levels of adoption of eMental health model. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(4). https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9485

- *Ferrari, M., Ahmad, F., Shakya, Y., Ledwos, C., & McKenzie, K. (2016). Computer-assisted client assessment survey for mental health: Patient and health provider perspectives. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1756-0.

- *Ferreira-Correia, A., Barberis, T., & Msimanga, L. (2018). Barriers to the implementation of a computer-based rehabilitation programme in two public psychiatric settings. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 24(1), 1–8.

- Firth, J., Torous, J., Nicholas, J., Carney, R., Rosenbaum, S., & Sarris, J. (2017). Can smartphone mental health interventions reduce symptoms of anxiety? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 218, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.046

- Fixsen, D., Panzano, P., Naoom, S., & Blasé, K. (2008). Measures of implementation components of the national implementation research network frameworks. Authors.

- *Fleming, T. M., Dixon, R. S., & Merry, S. N. (2012). ‘It's mean!’ the views of young people alienated from mainstream education on depression, help seeking and computerised therapy. Advances in Mental Health, 10(2), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.2011.10.2.195

- *Folker, A. P., Mathiasen, K., Lauridsen, S. M., Stenderup, E., Dozeman, E., & Folker, M. P. (2018). Implementing internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for common mental health disorders: A comparative case study of implementation challenges perceived by therapists and managers in five European internet services. Internet Interventions, 11, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.02.001

- *Forchuk, C., Reiss, J. P., O'Regan, T., Ethridge, P., Donelle, L., & Rudnick, A. (2015). Client perceptions of the mental health engagement network: A qualitative analysis of an electronic personal health record. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0614-7

- Forman, S. G., Olin, S. S., Hoagwood, K. E., Crowe, M., & Saka, N. (2009). Evidence-based interventions in schools: Developers’ views of implementation barriers and facilitators. School Mental Health, 1, 26–36.

- *Friesen, L. N., Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., & Pugh, N. E. (2014). A qualitative examination of psychology graduate students’ experiences with guided internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy. Internet Interventions, 1(2), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2014.04.001

- Gagnon, M. P., Ngangue, P., Payne-Gagnon, J., & Desmartis, M. (2016). m-Health adoption by healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 23(1), 212–220.

- Ganapathy, A., Clough, B. A., & Casey, L. M. (2021). Organizational and policy barriers to the use of digital mental health by mental health professionals. Telemedicine and e-Health, 27(12), 1332–1343. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0455

- Gavin, B., Lyne, J., & McNicholas, F. (2020). Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37(3), 156–158. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.72

- *Gibson, K., O’Donnell, S., Coulson, H., & Kakepetum-Schultz, T. (2011). Mental health professionals’ perspectives of telemental health with remote and rural first nations communities. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 17(5), 263–267. https://doi.org/10.1258/jtt.2011.101011

- Gilgun, J. F. (2019). Deductive qualitative analysis and grounded theory: Sensitizing concepts and hypothesis-testing. In The SAGE handbook of current developments in grounded theory (pp. 107–122).

- *Giroux, D., Bacon, S., King, D. K., Dulin, P., & Gonzalez, V. (2014). Examining perceptions of a smartphone-based intervention system for alcohol use disorders. Telemedicine and e-Health, 20(10), 923–929. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2013.0222

- *Glueckauf, R. L., Maheu, M. M., Drude, K. P., Wells, B. A., Wang, Y., Gustafson, D. J., & Nelson, E. L. (2018). Survey of psychologists’ telebehavioral health practices: Technology use, ethical issues, and training needs. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(3), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000188

- *Gould, C. E., Zapata, A. M. L., Bruce, J., Merrell, S. B., Wetherell, J. L., O'Hara, R., Kuhn, E., Goldstein, M.K., & Beaudreau, S. A. (2017). Development of a video-delivered relaxation treatment of late-life anxiety for veterans. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(10), 1633–1645. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217000928

- Gowen, L. K. (2013). Online mental health information seeking in young adults with mental health challenges. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 31(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2013.765533

- Graham, A. L., Carpenter, K. M., Cha, S., Cole, S., Jacobs, M. A., Raskob, M., & Cole-Lewis, H. (2016). Systematic review and meta-analysis of internet interventions for smoking cessation among adults. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 7, 55–69. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S101660

- Gratzer, D., Torous, J., Lam, R. W., Patten, S. B., Kutcher, S., Chan, S., Vigo, D., Pajer, K., & Yatham, L. N. (2021). Our digital moment: Innovations and opportunities in digital mental health care. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 66(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720937833

- Grubaugh, A. L., Gros, K. S., Davidson, T. M., Frueh, B. C., & Ruggiero, K. J. (2014). Providers’ perspectives regarding the feasibility and utility of an internet-based mental health intervention for veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(6), 624–631. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035772

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 1–9.

- Gun, S. Y., Titov, N., & Andrews, G. (2011). Acceptability of internet treatment of anxiety and depression. Australasian Psychiatry, 19(3), 259–264. https://doi.org/10.3109/10398562.2011.562295

- *Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Gullickson, K. M., Adrian-Taylor, S., Wilhelms, A., Sundström, C., & Nugent, M. (2020). Stakeholder perceptions of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy as a treatment option for alcohol misuse: Qualitative analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(3).

- *Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Nugent, M. M., Dirkse, D., & Pugh, N. (2017). Implementation of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy within community mental health clinics: A process evaluation using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1496-7

- *Hatch, A., Hoffman, J. E., Ross, R., & Docherty, J. P. (2018). Expert consensus survey on digital health tools for patients with serious mental illness: Optimizing for user characteristics and user support. JMIR Health, 5(6), e9777.

- *Hermes, E., Burrone, L., Perez, E., Martino, S., & Rowe, M. (2018). Implementing internet-based self-care programs in primary care: Qualitative analysis of determinants of practice for patients and providers. JMIR mental health, 5(2), e9600.

- *Hermes, E. D. A., Merrel, J., Clayton, A., Morris, C., & Rowe, M. (2019). Computer-based self-help therapy: A qualitative analysis of attrition. Health Informatics Journal, 25(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458216683536

- Hilty, D. M., Chan, S., Hwang, T., Wong, A., & Bauer, A. M. (2017). Advances in mobile mental health: Opportunities and implications for the spectrum of e-mental health services. mHealth, 3, 34. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2017.06.02

- *Holland, J., Hatcher, W., & Meares, W. L. (2018). Understanding the implementation of telemental health in rural Mississippi: An exploratory study of using technology to improve health outcomes in impoverished communities. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 41(1), 52–86.

- Ijzerman, R. V., van der Vaart, R., & Evers, A. W. (2019). Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy among psychologists in a medical setting: A survey on implementation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(8), e13432.