ABSTRACT

Objective

Gambling is increasingly identified as a public health concern as it carries a risk of harm for the person who gambles, friends and family, and the broader community. Mental Health First Aid® (MHFA) Australia’s Conversations About Gambling course is an early intervention program that teaches members of the public how to support someone experiencing harm from their gambling. Although the course improves participants mental health literacy and reduces stigma, its uptake has wavered compared to other similar MHFA courses, prompting the present study to investigate enablers and barriers to its implementation.

Methods

Online interviews and one focus group were conducted with 12 participants (six licenced MHFA instructors and six individuals from key partner organisations). Course implementation and uptake were explored.

Results

Thematic analysis identified a positive regard for the course among participants. Key themes related to implementation included: course-specific, implementation and process, and structural factors.

Discussion

This qualitative study identified the critical role of strong collaborative relationships with established industry providers for successful program uptake. It also pointed to the need for additional subject-specific consultation to identify a format and delivery method suited for the unique societal factors that impact course implementation.

1. Introduction

Almost two thirds of Australian adults participate in gambling (Dowling et al., Citation2016) with net losses totalling more than AUD25 billion in 2018–2019 (Queensland Government Statistician’s Office, Citation2021). A nationally representative survey conducted in 2015 estimated that 7.9% of adults who gamble were at risk of some level of harm, with just over 1% being classified as ‘problem gamblers’ (A. Armstrong & Carroll, Citation2017). Problem gambling is defined as difficulties limiting time and/or money spent on gambling, with subsequent negative impacts on the person who gambles, their family or friends, or the community (Neal et al., Citation2005). While gambling behaviour has traditionally been conceptualised based on the presence or absence of clinical markers for gambling pathology, with little emphasis on ‘low-risk’ behaviour (Davies et al., Citation2022), newer perspectives acknowledge levels of risk and harm at any degree of gambling participation (John et al., Citation2020; Langham et al., Citation2016).

A prominent taxonomy of gambling harm proposes three categories; harm to the person who gambles, harm to affected others, and harm to the community (Neal et al., Citation2005). It is important to note that although the person who gambles is likely to experience the greatest risk and amount of harm, they are not intrinsically the cause of gambling harm to others (Langham et al., Citation2016). Social and environmental factors contribute to the risk and type of gambling harm that may occur within any of the identified categories (John et al., Citation2020). Harms to the person who gambles include negative self-perception, increased risk of mental health problems and suicide, financial difficulties, social isolation or relationship breakdown, and negative impacts to work or study performance (Hing et al., Citation2021). Affected others, including family and friends, experience increased risk of mental health problems or distress, financial difficulties, family or intimate partner violence, and social isolation (Browne et al., Citation2016). Harms to the community may include greater levels of debt and reliance on welfare, damage to social cohesion, increased criminal activity, and increased burden of disease (Langham et al., Citation2016). Emanating from these definitions of associated harms from gambling, the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) is a commonly used validated scale to measure gambling behaviours over the past three months in the general population. Scores categorise gamblers into four levels of severity: (1) non-problem gambling, (2) low-risk gambling, (3) moderate-risk gambling, and (4) problem gambling (Miller et al., Citation2013). Problem gambling is also considered a psychiatric condition and is listed in the DSM-5 as a gambling disorder (Grant et al., Citation2017). While the diagnostic criteria for a gambling disorder and the PGSI have similar themes, the PGSI is not used to measure problem gambling severity in a clinical setting.

Prevalence of help-seeking is greater among people with higher severity of problem gambling behaviours, with a recent meta-analysis finding that around 1 in 25 people with moderate-risk gambling seek help, compared to 1 in 5 with problem gambling (Bijker et al., Citation2022). Rates of professional help-seeking for problem gambling are low, and most people who experience problem gambling tend to delay getting help until they experience severe harms or a crisis point (especially financial or emotional) (Hing et al., Citation2012). Common barriers to help-seeking include lack of awareness or inability to admit they have a problem, wanting to solve the problem on their own, feeling embarrassment or shame, or only wanting help for financial problems associated with their gambling. Conversely, factors that may promote help-seeking include improved public understanding around the impacts of gambling on the person, broader recognition that gambling problems are a public health concern, and more accurate awareness of what gambling behaviour and harm entail (Browne et al., Citation2020; Hing et al., Citation2021). Adults who have sought help for their gambling were most likely to do so by talking to family members or friends in the first instance (66%) (Browne et al., Citation2020), which places members of the person’s immediate network in a unique position to encourage professional help. These findings underscore the important role of community members in early intervention for problem gambling and denote both a need for more accurate public awareness of gambling harm and a reduction of stigmatising attitudes towards problem gambling to facilitate early help-seeking (Hing et al., Citation2012).

Despite the importance of community-based intervention, there is a poor understanding of gambling as a public health problem in Australia, which creates challenges for community members in identifying problem gambling when it occurs (Browne et al., Citation2020). Additionally, gambling behaviour is easily concealed (e.g. online, on mobile phones, in gambling venues), and family members or friends may not be with the person while they are gambling. This limits visibility of some of the more obvious warning signs and reduces opportunities to respond. Immediate signs of problem gambling may be more visible to gambling venue staff due to their proximity to the behaviour. However, there are conflicting interests inherent in these roles, reinforced by inconsistent voluntary compliance with prevention strategies and regulations by gambling operators (Williams et al., Citation2012). These factors may prevent gambling venue staff from acting.

Moreover, gambling is normalised and promoted through marketing campaigns that, according to the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office (Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, Citation2021), are resourced to a scale that organisations addressing gambling harm and promoting help-seeking cannot match. For instance, AUD70 million was spent to promote gambling during sporting events in Victoria in 2019, while the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation allocated AUD2.62 million for media campaigns promoting awareness of gambling harm in their 2019–2020 budget (Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, Citation2021). Tactics employed in sports betting advertising are reported to be very successful by consumers, as they appeal to a sense of community and belonging, which is both engaging and effective at socialising them to accept and participate in gambling (Gordon & Chapman, Citation2014). The allure of social inclusion created by this messaging, and the pervasiveness of gambling advertising, may impact peoples’ willingness to acknowledge harm associated with their gambling, and to seek help.

There is a growing body of research assessing the effectiveness of clinical interventions for problem gambling (Thomas et al., Citation2022). In Australia, dedicated government bodies, such as the New South Wales (NSW) Office of Responsible Gambling and the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, currently provide funding for community-led interventions, education programs and campaigns to address gambling harm. In 2022, the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation produced an outcomes framework to guide program planning, monitoring, and evaluation with seven clearly defined desired outcomes (Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Citation2022). Three of these outcomes related to improved community knowledge and capacity. Indicators of success for these outcomes include increasing knowledge and confidence of members of the community to talk to their loved ones about gambling risks, decreasing stigma towards people who experience gambling harm; increasing community capability to prevent and minimise gambling harm; and increasing help-seeking. These are consistent with the NSW Office of Responsible Gambling’s 2021–2024 education and awareness objectives, which emphasise the role of community-level awareness campaigns and education initiatives that improve knowledge, prevent gambling harm and reduce stigma in the general public (NSW Office of Responsible Gambling, Citation2021). The Mental Health First Aid® (MHFATM) course Conversations About Gambling is well-positioned to support these outcomes as an early intervention program that aims to provide course attendees with knowledge and skills to support a person experiencing harms from their gambling (Kelly, Citation2018). The course was recently evaluated through an uncontrolled trial, with participants reporting increased knowledge, skills, and confidence in helping a person experiencing problem gambling, as well as reduced stigma towards problem gambling (Bond et al., Citation2022). This is one of very few interventions to address gambling harm where:

The content is evidence-informed (Bond, Jorm, Miller, et al., Citation2016);

The course is principally an early intervention (rather than prevention) program;

The target audience is members of the community who may support a person who gambles (as opposed to targeting the person who gambles); and

There is empirical evidence that the course is effective in achieving its intended outcomes (Bond et al., Citation2022).

Despite these unique advantages, this course has not had the same level of uptake as other MHFA courses. For example, enrolment data to March 2023 show that Mental Health First Aid Australia’s Conversations About Suicide specialised course has seen more than 1,269 courses run nationally since its release in 2016. Comparatively, 109 Conversations About Gambling courses have been run nationally as of November 2022, with 65 of these delivered in NSW. The stark discrepancy in uptake may point to low appetite for community-based problem gambling interventions in Australia. This may result, in part, from the normalisation of gambling in Australian culture (Gordon & Chapman, Citation2014), poor awareness of gambling as a public health concern (Browne et al., Citation2020), or inadequate resourcing and evaluation in this area (Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, Citation2021). There has, however, previously been a lack of evidence to indicate whether these considerations or other factors have impacted the uptake of this course.

The present study aimed to identify and better understand enablers and barriers related to the uptake of the Conversations About Gambling course delivered in Gamble Aware regions across NSW, Australia by seeking the perspectives of course instructors and key partner organisations (KPOs) that advocate for and provide services to people experiencing gambling harm. Using the expertise of those who are directly involved in the delivery of the course, and who have intricate knowledge of the gambling sector in Australia, we hope to understand how to improve reach and uptake of the Conversations About Gambling course to increase community capacity to support a person who may be experiencing harm from their gambling.

2. Methods

2.1. Course delivery

Through a grant provided by the NSW Office of Responsible Gambling (RG/3137), Conversations About Gambling courses were delivered to the 10 Gamble Aware regions across NSW. Gamble Aware is a free, confidential service that assists anyone in NSW affected by problem gambling through information, support, and counselling services. Funding from the grant provider included the upskill of MHFA instructors to deliver the Conversations About Gambling course (so they can continue to deliver training after the grant period) and the delivery and evaluation of the course. In total, six instructors delivered 43 courses between April 2021 and October 2022 to 400 course attendees.

2.2. Participants

Due to incomplete responses to an initial demographic survey, demographic details are sparse. Of the 12 participants seven were female and five were male.

2.2.1. Participant group 1 – instructors

Six Conversations About Gambling course instructors consented to participate in the study. Participants had an average of 5.83 years of experience as licenced MHFA instructors (range: 3–12 years).

Instructors were eligible to participate if they:

Were an instructor of the Conversations About Gambling course; AND

Were part of the NSW Office of Responsible Gambling grant that assisted with the rollout of the Conversations About Gambling course; AND

Had delivered at least two courses within the aforementioned grant.

2.2.2. Participant group 2 – key partner organisations

Participants in this group were staff from key partner organisations (KPOs). Twenty-six organisations were contacted by email and six staff members from five organisations consented to participate in the study.

Staff members from KPOs were eligible to participate if they:

Were a staff member at an organisation that meets the aforementioned definition of a KPO; AND

Were based in NSW, Australia, AND

Had some experience facilitating the roll out or had knowledge of Mental Health First Aid Australia’s Conversations About Gambling course.

2.3. Procedure

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Melbourne (ID: 22698). Instructors of the Conversations About Gambling course and staff members from KPOs were contacted via email by a researcher to take part in a focus group or in one-on-one semi-structured interviews, respectively. Instructors who were unable to participate in a focus group were invited to participate in a one-on-one interview. The interviews and the focus group were conducted on the video conferencing platform Zoom in October 2022. The interviews and focus group were led by a member of the research team (SEB) using a semi-structured interview schedule (see Supplementary File 1). Participants were also asked to complete a short online survey hosted on Qualtrics to collect demographic information prior to the focus group and interviews.

Questions that guided the focus group and interviews with instructors related to five areas: (1) reasons for participation in the project, (2) experiences with the Gamble Aware regions, (3) experiences relating to course implementation, (4) strategies used to promote the course, and (5) aspects of the course and course implementation that ran well.

Questions that guided the interviews with KPOs related to five areas: (1) purpose of the organisation, (2) how the organisation supports people experiencing problem gambling, (3) knowledge of the Conversations About Gambling course, (4) their experiences of or perspectives on course implementation in their Gamble Aware region, (5) whether the organisation would consider facilitating the implementation of further Conversations About Gambling courses in their region.

The interview schedule for interviews and focus groups also included prompts that focused on difficulties or challenges with promotion, implementation and delivery, as well as potential improvements that could be made in these areas.

Participants were provided with an information sheet that confirmed that their responses would be kept confidential and that they could withdraw from the study at any time, and all participants signed a consent form. In total, one focus group and one semi-structured interview were conducted with instructors, and five interviews were conducted with six individuals from KPOs. The focus group and interviews were audio recorded and transcribed for analysis.

2.4. Data analysis

Data were analysed using the guidelines for thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). In the first stage, the interview and focus group transcripts were read several times so the researcher (SEB) became immersed in the data. In the second stage, sentences, key words, and phrases that pertained to emerging patterns in the data were highlighted. These sentences and phrases generated codes that related to the research questions included in the interview and focus group schedules. These codes were then grouped together to form overarching themes. In the fourth stage of analysis, themes were reviewed and revised against the coded data and the research questions. Lastly, themes were defined and organised into categories that answered the overall research questions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). For example, initial codes were assigned to describe enablers and barriers to course delivery as identified by instructors and by KPOs. Analysis revealed three broader factors – (1) course-specific factors relating to aspects of the Conversations About Gambling program itself, (2) factors pertaining to experiences and issues with promoting the course to communities, and (3) sociocultural factors that were related to the wider social and cultural context in which the Conversations About Gambling course delivery had taken place. Codes within these themes were similar in nature, while the themes themselves were heterogenous. Data from both participant groups were combined as analysis indicated that the themes were similar across the two groups.

Conducting a qualitative, interview-based methodology was determined to be an appropriate method for addressing the research questions for this study. This approach operates within a social constructionism framework based on the idea that data is developed and shaped by the social environments in which people interact (Gergen, Citation1985) and is therefore useful for contextualising research that explores the lived experiences of participants (Cosgrove, Citation2000; Taylor & Ussher, Citation2001). By drawing from the experiences of those directly involved in the delivery of this course, and knowledge of professionals with expertise in the gambling industry we follow the theory underpinning the framework.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Promotional strategies used for course implementation.

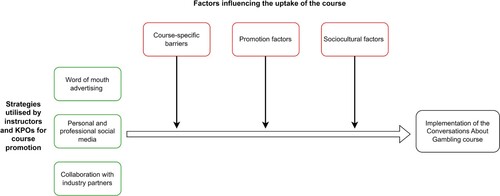

There were three promotional strategies used for implementation of the Conversations About Gambling course common to the participants. They include course promotion via word-of-mouth advertising (using existing professional contacts), advertising the Conversations About Gambling program through personal and professional social media platforms and websites, and collaborating with prominent industry providers and Gamble Aware Providers themselves. These strategies, and how they relate to factors proposed by participants as influencing the uptake of the course, are depicted in .

3.2. Factors influencing course implementation

Numerous factors influenced the uptake of the Conversations About Gambling course. These factors fell into three main themes:

Course specific factors, which are elements of the course content, structure, or curriculum that either facilitated or hindered the uptake of the program

Promotion factors, which relate to the promotional content and strategies used to advertise the course, including brand awareness and the quality and quantity of instructor networks

Sociocultural factors, which pertain to the broader context in which the Conversations About Gambling course rollout has taken place.

3.3. Course-specific factors

Consistent with a prior evaluation of this course (Bond et al., Citation2022), the Conversations About Gambling course was highly regarded by instructors and KPOs, with many commenting that they would recommend it to others within their profession. The course itself was perceived as engaging, relevant, well structured, and appropriately informative. Prominent in this feedback was the research basis of Mental Health First Aid Australia’s suite of courses, which differentiated the course from others in the industry. KPO participants specifically mentioned the evidence underpinning the course as a significant factor facilitating the rollout of Mental Health First Aid Australia’s courses more generally:

I love Mental Health First Aid courses like this one because of the degree of research that goes into it [the programs] … it's a lot more [research] than a lot of other products out there. – Participant 1 (KPO)

We are still coming out of Covid, so I think that had an impact on some of the courses we were trying to facilitate. In community organisations there's still staffing issues related to Covid, so there are still time issues related to that you know, people just don't have the time to attend a 4 to 6 hours workshop. – Participant 10 (KPO)

Pretty much everyone who attended my courses were working in some kind of mental health profession or volunteer capacity, you know like social work, or they were from Lifeline, etc. So, they found the content of the course was sometimes a bit basic and that the scenarios and examples didn't hit the mark in terms of how they would be applying the content. Like yes they might talk to their friends about gambling harm but they would mostly be looking at using the skills in a professional context. – Participant 6 (instructor)

One way to address this barrier would be to ensure the course is marketed and delivered to the intended audience, i.e. those without training in gambling related harm and gambling help.

In contrast, other participants suggested the content of the Conversations About Gambling course is too advanced for the public, especially for individuals with limited mental health literacy. Participant 5, an instructor, commented that members of the community often seemed overwhelmed by the course:

There is a lot to take in, especially for people who don’t have an awareness of [problem] gambling and this sort of thing. It’s new content for them but it’s too much; you’re talking about gambling, you’re talking about the action plan, you’re talking about suicide … I think it’s too heavy for some people.

3.4. Promotion factors

Several factors relating to course promotion strategies and/or advertising methods facilitated the delivery of the Conversations About Gambling course. One successful promotional strategy involved collaborative partnerships with prominent Gamble Aware Providers; strategies that are proven in the literature (Byrne et al., Citation2015; Golechha, Citation2016; Kloos et al., Citation2012). Most participants cited this as the most successful strategy for getting the course ‘off the ground’:

I probably had the most success getting the course off the ground when I connected with the more well-known organisations in this space; the Salvation Army and I think it was Mission Australia … The Gamble Aware [provider] in my region also did some really hard work to get people to the course too. So that was really good. – Participant 9 (Instructor)

I know that our Facebook push was hugely successful. Actually, our EDM was really good as well, because we now have big databases of contacts in our system so we could reach a lot of people you know. And people who might actually be interested [in the course] too. So that worked quite well for us. – Participant 1 (KPO)

Some of the advertising and quality of the pamphlets that were being provided to us … were not to the standard for us to be able to push out onto our Facebook or digital comms. It was a little loose, so we definitely tidied that up a little bit … we juiced it up. – Participant 1 (KPO)

There are just so many organisations and trainers like us out there now, all trying to get the same market and you know … . there's just so much competition … and with our instructors’ sort of doing their own thing with advertising and promoting [our courses] I don't think people recognise the Mental Health First Aid brand. And so I think that's a big part of why it's been so hard to roll out this course.

Some participants additionally explained that there was some confusion regarding the purpose and content of the course, with members of the community sometimes mistaking the course as an intervention targeted at people experiencing gambling harm:

I think sometimes when people see the course advertised too, they think it's about their own personal experience, they don't realise it's about learning how to help someone else. They think ‘well I don't have a gambling problem, so I don't need to come’. So that's a real barrier that is hard to break down. – Participant 11 (KPO)

As identified by previous studies (Mendenhall & Jackson, Citation2013; Terry, Citation2011) issues with brand recognition, quality of advertising and ambiguous content in course promotional materials suggests a need for a more nationally cohesive or centralised approach to the roll out of new MHFA training programs. A centralised promotion approach could see an improved uptake of the Conversation About Gambling course, as well as improved measures of quality assurance (Terry, Citation2011). Unfortunately, a lack of outcome-based evaluations of Australian community-level early intervention programs for gambling harm (Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, Citation2021) makes it difficult to appropriately contextualise this preliminary finding, and simultaneously highlights the need for more research in this area.

3.5. Sociocultural factors

Four sub-themes were found regarding sociocultural factors that may have influenced course uptake. These include: the role of gambling advertising and the gambling industry, the normalisation of gambling as a socially and culturally acceptable behaviour, a lack of public awareness and education around gambling as a mental health problem, and stigma and stereotypes associated with gambling.

The impact of gambling advertising on social attitudes towards problem gambling and related gambling harm was central to many discussions with participants. All spoke at length about the broader challenges that organisations and public health campaigns face when attempting to raise awareness about gambling harm in the context of an enormously profitable industry in which advertising is rife. One participant commented:

So, with trying to promote this course, you're already up against the gambling industry and all its advertising before you've even started to have those conversations. Look at all the money that goes into advertising gambling, it’s significantly more than the funding that programs like this one get. If even a quarter of the money that went into gambling advertising was spent on promoting courses like [Conversations About Gambling], we wouldn’t have such an issue getting them off the ground. – Participant 11 (KPO)

There's this idea that [problem gambling] is a choice. … most people don't understand the mental health part of [problem] gambling. It's such a big component of the issue but it's rarely understood. It's always just been ‘oh he's no good on the punt’, you know … so people aren’t going to participate in a course like this one you know, if they don’t see the subject as being a problem. – Participant 4 (KPO)

I think there's still a lot of stigma around gambling too. It's not something people want to talk openly about; it's seen as a private matter. So, I guess gambling is still quite a taboo subject in the community you know. – Participant 10 (KPO)

I always like to use that analogy you know, of 30 or 40 years ago. We are where the tobacco industry was back then, attitudes back then were that smoking was something everyone enjoyed and it wasn't bad for you so why would we need to be educated about it? So that's where we are with attitudes to gambling, and with the tobacco industry it took many years and persistence to raise awareness and change behaviours. And it's the same road for us in the [problem] gambling space. – Participant 10 (KPO)

4. Strengths and limitations

This study has extended the existing literature beyond quantitative investigations into the effectiveness of the Conversations About Gambling course (Bond et al., Citation2021). It also contributes to the small but growing body of qualitative research exploring MHFA courses in Australia, and globally, from the perspective of key stakeholders (Bovopoulos et al., Citation2016; Jorm et al., Citation2005; Rossetto et al., Citation2018).

A key strength of the qualitative approach used in this study was the opportunity it provided for a detailed understanding of the factors surrounding course implementation and uptake from the perspective of the people promoting and implementing the course within communities. This included insights into experiences and perceptions that may elude quantitative approaches (Crowe et al., Citation2015). It also permitted meanings to be analysed in their context (Bryman, Citation2003) and thematic analysis promoted the generation of unanticipated insights and social interpretation of the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Specifically, the in-depth understandings of stakeholder experiences allowed a more nuanced analysis into course-specific, promotional, and sociocultural factors affecting course implementation.

The identification of barriers and limitations to course implementation provide context to the previous quantitative finding of low course uptake (Bond et al., Citation2021). The qualitative findings allow some triangulation of these data with those of previous studies and provide a depth of insight that lends itself to more effectively guiding the future directions of the Conversations About Gambling course and mental health first aid course development in general.

A limitation to this study is the small number of participants which, according to data saturation principles, may have limited the number of themes identified in the analysis (Guest et al., Citation2006). The sample size reflects challenges recruiting participants due to the eligibility criteria, whereby KPOs who were contacted were either ineligible to participate, time-poor or only had minimal exposure to facilitating the roll out of the course. This may have additionally impacted participants’ feelings of readiness to speak about their experiences with the Conversations About Gambling course. Though a larger sample size may have generated further themes for analysis in this study, or additional depth to the findings, it is difficult to prescribe a specific sample size at which saturation is achieved, and other considerations beyond sample size and saturation are important when assessing for data adequacy and the generation of rich and meaningful analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). This study used a rigorous thematic approach to produce insightful analysis that answers the research questions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Another limitation of this study was the use of convenience sampling from the pool of MHFA instructors and KPOs who had experience with, or knowledge of, facilitating the delivery of the course in NSW communities. While this was necessary to address the research questions, participants’ views may not be representative of the wider industry, or of all stakeholder groups. Furthermore, instructors and KPOs with strong opinions or highly positive or negative experiences delivering the Conversations About Gambling course may have been more motivated to participate (Liamputtong, Citation2009). A final limitation, especially in the context of a focus group discussion, is the tendency for participants to respond in a manner that is socially desirable (Litosseliti, Citation2003), which may have impacted participants’ responses out of a desire to preserve their relationship with Mental Health First Aid Australia or the grant provider, or not voice views that differed from other focus group participants. However, significant effort has been made to de-identify the data at all stages of this evaluation, and that these efforts were explained to participants in the Plain Language Statement and at the beginning of each interview. It is our belief that most instructors and KPOs in this study were quite open and candid about their experiences and perspectives delivering the Conversations About Gambling course.

A final limitation relates to the lack of feedback from members of the public who may have been reached by advertising materials for this course and chosen not to undertake the training. Future implementation evaluations may benefit from sampling within this group.

5. Summary, conclusion and recommendations

This qualitative study aimed to identify and better understand enablers and barriers related to the uptake of the Conversations About Gambling course delivered in Gamble Aware regions across NSW by seeking the perspectives of course instructors and key partner organisations (KPOs) that advocate for and provide services. Overall, the Conversations About Gambling course is perceived as engaging, well-structured, and appropriately informative as an early intervention strategy, consistent with feedback for other MHFA courses (G. Armstrong et al., Citation2020; Bond et al., Citation2022; Bond, Jorm, Kitchener, et al., Citation2016). Course implementation was primarily facilitated by strong collaborative partnerships with key industry providers with significant outreach into local communities, which allowed them to extensively publicise the course. Consistent with the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation’s approach to partnership programs in the gambling harm prevention space, these experiences highlight the critical role of collaboration with prominent industry providers that are ‘already established within targeted communities’ (Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, Citation2021) for successful program delivery.

Factors identified to have potentially hindered course uptake encompassed course-specific elements such as the time commitment required by participants and relevance of the curriculum to the intended audience; the suitability and quality of course promotional materials; and sociocultural factors pertaining to the normalisation of gambling and knowledge of gambling harms within Australia. Additional subject-specific consultation could help identify a format and delivery method suited for the unique societal factors that impact the implementation of the Conversations About Gambling course. Such an approach could lead to successful program delivery based on effective curriculum content and an appropriate fit to the context in which it will be delivered. Successful implementation requires continuous community collaboration to assess needs, resources, and the capacity for program application (Kloos et al., Citation2012). Thus, while the Conversations About Gambling curriculum was developed in consultation with experts, gambling support services and academic experts, further work should aim to explore how to strengthen community capacity to take up early intervention mental health programs about gambling harm.

This study highlights the need for further research that aims to explore how to strengthen community capacity for early intervention programs about gambling harm and whether shifting public attitudes to accept problem gambling as a mental health problem is a necessary precursor or an outcome of successful implementation.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation, J.N.L, A.R. K.S.B., and N.J.R.; Data curation, S.E.B. and J.N.L.; Formal analysis, S.E.B.; Investigation, J.N.L. and S.E.B.; Methodology, J.N.L, A.R. K.S.B., and N.J.R.; Project administration, J.N.L. S.E.B. and K.S.B.; Resources, K.S.B.; Supervision, N.J.R.; Writing – original draft, S.E.B., J.N.L., A.V.S., K.J.C. and K.S.B.; Writing – review and editing, S.E.B., J.N.L., K.S.B., A.V.S., K.J.C. A.R., and N.J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset analysed in the current study is not publicly available, or available on reasonable request from the corresponding author because participants explicitly consented to only have their data shared with the immediate research team.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. P., Faulkner, G. E., Paglia-Boak, A., & Irving, H. M. (2010). Adolescents’ attitudes toward wheelchair users: A provincial survey. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 33(3), 261–263. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e328333de97

- Armstrong, A., & Carroll, M. (2017). Gambling activity in Australia. Australian Institute of Family Studies. https://aifs.gov.au/research/research-reports/gambling-activity-australia

- Armstrong, G., Sutherland, G., Pross, E., Mackinnon, A., Reavley, N., & Jorm, A. F. (2020). Talking about suicide: An uncontrolled trial of the effects of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health First Aid program on knowledge, attitudes and intended and actual assisting actions. PLoS One, 15(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244091

- Bijker, R., Booth, N., Merkouris, S. S., Dowling, N. A., & Rodda, S. N. (2022). Global prevalence of help-seeking for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 117(12), 2972–2985. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15952

- Bond, K. S., Cottrill, F. A., Morgan, A. J., Chalmers, K. J., Lyons, J. N., Rossetto, A., Kelly, C. M., Kelly, L., Reavley, N. J., & Jorm, A. F. (2022). Evaluation of the conversations about gambling Mental Health First Aid course: Effects on knowledge, stigmatising attitudes, confidence and helping behaviour. BMC Psychology, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00785-w

- Bond, K. S., Jorm, A. F., Kitchener, B. A., & Reavley, N. J. (2016). Mental Health First Aid training for Australian financial counsellors: An evaluation study. Advances in Mental Health, 14(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2015.1122704

- Bond, K. S., Jorm, A. F., Miller, H. E., Rodda, S. N., Reavley, N. J., Kelly, C. M., & Kitchener, B. A. (2016). How a concerned family member, friend or member of the public can help someone with gambling problems: A Delphi consensus study. BMC Psychology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0110-y

- Bond, K. S., Reavley, N. J., Kitchener, B. A., Kelly, C. M., Oakes, J., & Jorm, A. F. (2021). Evaluation of the effectiveness of online Mental Health First Aid guidelines for helping someone experiencing gambling problems. Advances in Mental Health, 19(3), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2020.1763815

- Bovopoulos, N., LaMontagne, A., Martin, A., & Jorm, A. (2016). Delivering Mental Health First Aid training in Australian workplaces: Exploring instructors’ experiences. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 18(2), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2015.1122658

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Browne, M., Langham, E., Rawat, V., Greer, N., Li, E., Rose, J., Rockloff, M., Donaldson, P., Thorne, H., Goodwin, B., Bryden, G., & Best, T. (2016). Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: A public health perspective. https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/assessing-gambling-related-harm-in-victoria-a-public-health-perspective-69/

- Browne, M., Rockloff, M., Hing, N., Russell, A., Murray-Boyle, C., Rawat, V., Tran, K., Brook, K., & Sproston, K. (2020). NSW Gambling survey 2019. https://www.gambleaware.nsw.gov.au/resources-and-education/check-out-our-research/published-research/nsw-gambling-survey-2019

- Bryman, A. (2003). Quantity and quality in social research. Routledge.

- Byrne, K., McGowan, I., & Cousins, W. (2015). Delivering Mental Health First Aid: An exploration of instructors’ views. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 17(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2014.995422

- Cosgrove, L. (2000). Crying out loud: Understanding women's emotional distress as both lived experience and social construction. Feminism & Psychology, 10(2), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353500010002004

- Crowe, M., Inder, M., & Porter, R. (2015). Conducting qualitative research in mental health: Thematic and content analyses. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(7), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415582053

- Davies, N. H., Roderique-Davies, G., Drummond, L. C., Torrance, J., Sabolova, K., Thomas, S., & John, B. (2022). Accessing the invisible population of low-risk gamblers, issues with screening, testing and theory: A systematic review. Journal of Public Health (Germany). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01678-9

- Delfabbro, P., Hundric, D. D., Ricijas, N., Derevensky, J. L., & Gavriel-Fried, B. (2022). What contributes to public stigma towards problem gambling?: A comparative analysis of university students in Australia, Canada, Croatia and israel. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(4), 1127–1141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10086-3

- Dowling, N. A., Youssef, G. J., Jackson, A. C., Pennay, D. W., Francis, K. L., Pennay, A., & Lubman, D. I. (2016). National estimates of Australian gambling prevalence: Findings from a dual-frame omnibus survey. Addiction, 111(3), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13176

- Gergen, K. J. (1985). The social constructionist movement in modern psychology. American Psychologist, 40(3), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.40.3.266

- Golechha, M. (2016). Health promotion methods for smoking prevention and cessation: A comprehensive review of effectiveness and the way forward. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, https://doi.org/10.4103/2008-7802.173797

- Gordon, R., & Chapman, M. (2014). Brand community and sports betting in Australia. https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/documents/75/Research-report-brand-community-and-sports-betting-in-Australia.pdf

- Grant, J. E., Odlaug, B. L., & Chamberlain, S. R. (2017). Gambling disorder, DSM-5 criteria and symptom severity. Comprehensive Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.02.006

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Henderson, C., Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 777–780. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056

- Hing, N., Nuske, E., & Gainsbury, S. (2012). Gamblers at-risk and their help-seeking behaviour (Issue September). Gambling Research Australia. https://www.gamblingresearch.org.au/publications/gamblers-risk-and-their-help-seeking-behaviour

- Hing, N., Russell, A. M. T., Browne, M., Rockloff, M., Greer, N., Rawat, V., Stevens, M., Dowling, N., Merkouris, S., King, D., Breen, H., Salonen, A., & Woo, L. (2021). The second national study of interactive gambling in Australia (2019–20). https://www.gamblingresearch.org.au/publications/second-national-study-interactive-gambling-australia-2019-20

- John, B., Holloway, K., Davies, N., May, T., Buhociu, M., Cousins, A. L., Thomas, S., & Roderique-Davies, G. (2020). Gambling harm as a global public health concern: A mixed method investigation of trends in Wales. Frontiers in Public Health, 8). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00320

- Jorm, A. F., Christensen, H., & Griffiths, K. M. (2006). Changes in depression awareness and attitudes in Australia: The impact of beyondblue: the national depression initiative. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01739.x

- Jorm, A. F., Kitchener, B. A., & Mugford, S. K. (2005). Experiences in applying skills learned in a Mental Health First Aid training course: A qualitative study of participants’ stories. BMC Psychiatry, 5(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-5-43

- Kelly, L. (2018). Conversations about gambling: Course handbook. Mental Health First Aid.

- Kloos, B., Hill, J., Thomas, E., Elias, M. J., & Dalton, J. H. (2012). Community psychology (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Langham, E., Thorne, H., Browne, M., Donaldson, P., Rose, J., & Rockloff, M. (2016). Understanding gambling related harm: A proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2747-0

- Liamputtong, P. (2009). Qualitative research methods (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press Australia and New Zealand.

- Litosseliti, L. (2003). Benefits and Limitations of Focus Group Methodology. Using Focus Groups in Research (1st ed.). Cornwall, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Mendenhall, A. N., & Jackson, S. C. (2013). Instructor insights into delivery of Mental Health First Aid USA: A case study of mental health promotion across one state. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 15(5), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2013.853420

- Miller, N. V., Currie, S. R., Hodgins, D. C., & Casey, D. (2013). Validation of the problem gambling severity index using confirmatory factor analysis and rasch modelling. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 22(3), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1392

- Neal, P., Delfabbro, P., & O’Neil, M. (2005). Problem gambling and harm: Towards a national definition. Melbourne: Office of Gaming and Racing, Victorian Government Department of Justice. http://www.gamblingresearch.org.au/home/research/gra+research+reports/problem+gambling+and+harm+-+towards+a+national+definition

- NSW Office of Responsible Gambling. (2021). Education and awareness agenda 2021–2024. https://www.gambleaware.nsw.gov.au/-/media/files/education-and-awareness-agenda-2021-2024.ashx?rev=821c6269e9dc47d78ec03206b8d0bbad

- Queensland Government Statistician’s Office. (2021). Australian gambling statistics, Explanatory notes. www.qgso.qld.gov.au

- Reed, J., Quinlan, K., Labre, M., Brummett, S., & Caine, E. D. (2021). The Colorado National Collaborative: A public health approach to suicide prevention. Preventive Medicine, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106501

- Rossetto, A., Jorm, A. F., & Reavley, N. J. (2018). Developing a model of help giving towards people with a mental health problem: A qualitative study of Mental Health First Aid participants. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 12(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-018-0228-9

- Svensson, B., Hansson, L., & Stjernswärd, S. (2015). Experiences of a Mental Health First Aid training program in Sweden: A descriptive qualitative study. Community Mental Health Journal, 51(4), 497–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9840-1

- Taylor, G. W., & Ussher, J. M. (2001). Making sense of S&M: A discourse analytic account. Sexualities, 4(3), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346001004003002

- Terry, J. (2011). Delivering a basic mental health training programme: Views and experiences of Mental Health First Aid instructors in Wales. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 18(8), 677–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01719.x

- Thomas, A., Merkouris, S. S., Rodda, S. N., & Dowling, N. A. (2022). Gambling research summary 2020–21. https://www.gambleaware.nsw.gov.au/-/media/files/published-research-pdfs/short-gambling-research-summary-2020-21—final.ashx?rev=7e31d94b275f474384c417234b5f7c8d&hash=BDA71B5C88953CFD6A3081109B6F15D5

- Victorian Auditor-General’s Office. (2021). Reducing the harm caused by gambling. https://www.audit.vic.gov.au/report/reducing-harm-caused-gambling?section=33780–appendix-b-acronyms-and-abbreviations

- Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. (2022). Reducing gambling harm in Victoria: Outcomes framework. Reducing gambling harm in Victoria: outcomes framework.

- Williams, R. J., West, B. L., & Simpson, R. I. (2012). Prevention of problem gambling: A comprehensive review of the evidence and identified best practices. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265942706

- World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564779