ABSTRACT

In 2011, the 3.11 triple disaster of The Great East Japan Earthquake, the ensuing tsunami and the nuclear accident shook both the built and social environments of local communities in Tōhoku, Japan. To support successful community recovery, local participation has been implemented in many localities in the form of machizukuri, or bottom-up resident participation in place governance and community building. However, massive building projects have delayed reconstruction and social recovery is still ongoing. This research argues that community recovery may be further delayed because of renegotiation of spatial and social safety triggered by reconstruction policies. Based on ethnographic data collected during eight months of fieldwork in the tsunami-stricken town of Yamamoto, this research analyzes machizukuri groups as collective actors who are constructing place-frames characterized by insecurity and the redefinition of the social and geographical borders of a post-disaster community.

Introduction

On the 11th of March in 2011, the town of Yamamoto and the rest of the Tōhoku (northeastern Japan) coast were abruptly shaken from everyday life and thrown into post-disaster mayhem by the 3.11 triple disaster of The Great East Japan Earthquake, the ensuing tsunami and the nuclear accident. The local landscape was changed for good and, even now over seven years after the disaster, massive recovery and development projects still shape the locals’ living environments. As a result, the pre-disaster everyday neighborhood and village communities were scattered and forced to spend a prolonged period in temporary housing; individuals were later re-dispersed to permanent housing. Having learned from the experiences of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995, the national Reconstruction Design Council outlined in its report basic guidelines for reconstruction that recognized local residents as the experts of their communities, thus having a central role in the reconstruction:

The fundamental principle for reconstruction is that the main actors should be the municipalities themselves, as it is the residents who are closest to their communities and understand local characteristics best (Reconstruction Design Council, Citation2011, p. 18, emphasis by the author).

The council highly encouraged the establishment of “town and village community development associations” (machizukuri kyōgikai) as a practical means to incorporate the local perspective into reconstruction (Reconstruction Design Council, Citation2011, p. 18). However, the task of these groups is far from easy not only because of their limited power in the actual planning processes (Cho, Citation2014; Mochizuki, Citation2014), but also because the disaster drastically altered the social and physical living environments, forcing the residents to redefine those very ‘communities and local characteristics’ in the crossfire of multiple political interests and discourses of, for example, nostalgic hometown (furusato), social bonds and relationships (kizuna and tsunagari), and ‘building back better.’ Although disasters are seen as an opportunity for development (Shaw, Citation2014) and the 3.11 disaster as a chance to build a ‘New Tōhoku’ (Reconstruction Agency, Citationn.d.), the large-scale reconstruction projects implemented in the name of ‘building back better’ have in fact delayed reconstruction and community recovery (Akimoto, Citation2018; Edgington, Citation2017; Nagamatsu, Citation2018). And while the infrastructure projects are proceeding, social recovery is still a challenge in a region characterized by accelerated population decline and aging (Matanle, Citation2013; Yan & Roggema, Citation2017).

The present research argues that a factor that may further delay the long-term community recovery on the local level is the struggle to collectively redefine social and spatial safety as a response to reconstruction policies. This finding is based on eight months of fieldwork in the tsunami-stricken town of Yamamoto, and the analysis of local machizukuri groups as collective actors seeking to reconstitute a sense of community through place-framing, characterized by insecurity and a redefinition of the social and geographical borders of community.

This article first introduces the ‘machizukuri practice’ that refers to various forms of bottom-up citizen-initiated participation in local place governance (Evans, Citation2002; Hein, Citation2001, Citation2008; Sorensen & Funck, Citation2007; Watanabe, Citation2007). After 3.11, reconstruction machizukuri (fukkō machizukuri) groups were established in many localities to facilitate community building. Research on machizukuri has approached the topic mainly from the perspective of citizen participation as well as urban planning and place governance (e.g. Edgington, Citation2011b; Evans, Citation2002; Hein, Citation2001; Kobayashi, Citation2007; Kusakabe, Citation2013; Matsuno, Citation1997; Sorensen & Funck, Citation2007). However, research on machizukuri has seldom studied the relation between spatiality and local community processes in detail (cf. research by Hein, Citation2008; Ishii, Citation2014; Ito, Citation2007; Murakami et al., Citation2014; Watanabe, Citation2007). Although machizukuri, by definition, includes the collective local construction of a sense of place and community that are important and intertwined aspects of community adaptation after a crisis (Lyon, Citation2014; Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche, & Pfefferbaum, Citation2008; Perkins & Long, Citation2002), post-3.11 research has focused mainly on institutionalized machizukuri (e.g. Hirota, Citation2014; Nii, Citation2017; Sakurai & Ito, Citation2013; Vaughan, Citation2014).

Machizukuri groups can also be seen as forums for residents to establish a voice in a post-disaster setting, in which various social actors often seek to claim ‘ownership’ of the disasters: what happened, who the victims are, what the responsibilities are, and what ought to be the ideal post-disaster future. This framing not only concerns the disaster event and its immediate outcomes but also reconstruction and its anticipated long-term results (Gotham & Greenberg, Citation2014; Oliver-Smith & Hoffman, Citation2002. The media framing of the 3.11 disaster has been studied (e.g. Chattopadhyay, Citation2012; Rausch, Citation2012), but to grasp the collective, long-term efforts of place-making and community building in relation to the reconstruction policies, this article discusses machizukuri groups from the perspective of place-framing (Martin, Citation2003b). The place-framing approach perceives place-based community groups as actors constructing and enacting territorial and social community often as a response to place contestation (Pierce, Martin, & Murphy, Citation2011).

Analyzing these collective processes and politics reshaping the local post-disaster communities is integral to understanding community resilience and the effects of the disaster and reconstruction (Barrios, Citation2014), especially in the long-term recovery that often is neglected in disaster research (Gomez & Hart, Citation2013). Aftermaths of historical disasters and their interpretations have been of use in the construction of the imaginary community of the Japanese nation (Borland, Citation2006; Clancey, Citation2006; Schencking, Citation2008). This research touches upon similar dynamics at the micro-scale in Yamamoto and illustrates how post-disaster realities are renegotiated and used to construct and contest spatially and socially safe communities.

Reconstruction machizukuri through the lens of place-framing

The concept of machizukuri—literally meaning ‘town making,’ but often translated as ‘community development’—is an umbrella term generally understood as citizen participation in the planning and management of a living environment. It comprises a wide variety of activities, from urban planning initiatives to community welfare projects. The term is often contrasted with toshikeikaku, or top-down urban planning. The institutionalized form of machizukuri, to which the reconstruction guidelines mainly refer, originates from 1970s Kōbe, where locals started to cooperate with experts and local authorities to reduce air pollution. Since then, local governments have adopted machizukuri in their formal proceedings to varying degrees (Evans, Citation2002; Hein, Citation2001; Sorensen & Funck, Citation2007; Watanabe, Citation2007).

In contrast to everyday machizukuri that aim at gradual change (Evans, Citation2002, p. 449), the 3.11 disaster forced a rapid response with little expertise. Even today, the local authorities attempt to balance different interests within complicated governing and financial reconstruction structures (Mochizuki, Citation2014). Having learned from the criticism arising from excessive top-down reconstruction policies after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in Kōbe in 1995 (Edgington, Citation2011b), the authorities in Tōhoku embraced rhetoric that focused on resident participation. However, in practice, the planning process was kept mostly under the control of the authorities and justified by the discourse of speed, expertise, and efficiency, which would have been lost if public consensus and participation were prioritized (Cho, Citation2014; Mochizuki, Citation2014; Watanabe, Citation2007; interview with Yamamoto reconstruction consultation company representative). This complicated the practical involvement of locals in the decision-making process as well as shaped the sociopolitical framework within which the machizukuri groups framed their activities.

The term machi (‘a town’) itself refers to a small place (such as a neighborhood) and includes not only the physical aspects of the place but also the non-physical features of the community; the focus is on the individuality and identity of a particular small place-based everyday social community as well as on welfare and involvement (Evans, Citation2002; Hein, Citation2008; Kusakabe, Citation2013; Watanabe, Citation2007). Zukuri (from the verb tsukuru, ‘to do’) is translated as ‘making,’ and it does not refer to only a one-time action, but also to a continuous process. Watanabe (Citation2007) remarks that machizukuri is as much about the planning result as it is about the process itself: the importance of doing things in/for localities with other locals (Watanabe, Citation2007). Therefore, this research perceives machizukuri activities as ‘spatial practices…that [do] not just presuppose its [community’s] existence,’ but also ‘perform and in some senses create it’ (Cornwall, Citation2002, p. iii). As machizukuri relates to how the residents engage in the planning and management of their living environments at the neighborhood level, it also can be perceived to play a role in the reconstruction of a shared sense of place and community. In addition to citizen participation, sense of place and community are regarded as highly relevant factors in disaster recovery affecting community disaster resilience and adaptation to change (e.g. Norris et al., Citation2008).

To understand the local machizukuri activities as collective efforts to promote a vision of place-based community, this article analyzes the groups on the basis of a place-framing approach (Martin, Citation2003b). By using place-framing as an analytical tool, machizukuri groups are seen as collective actors participating in place-making, while simultaneously enacting and constructing their territorial communities. Frames in general function as the schema for interpretation (Goffman, Citation1974) and collective action frames are negotiated collectively to interpret problems and define solutions while motivating, empowering, and offering rationale for the action (Benford & Snow, Citation2000; Snow & Benford, Citation1988; Snow, Rochford, Worden, & Benford, Citation1986). Place-framing constructs ‘place-based collective action frames’ that add the dimension of place to the analysis of collective action frames, which directs attention toward how activism is discursively situated: Collective action is the enactment of place-based collective identity through the process of defining territorial community and constructing a shared conception of an ideal neighborhood (Larsen, Citation2008; Martin, Citation2003a, Citation2003b, Citation2013). Arguably, place-frames specify ‘who and where we are’ also in the post-disaster setting, in which the existing communities are reshaped and new ones are constructed (Barrios, Citation2014).

As place-frames draw from the material experience of the place, they are also influenced by the physical environment (Martin, Citation2013, Citation2003b), which in the post-disaster situation is altered drastically from the original. Furthermore, framing is affected by the actors positioned within the place-based community, but as place-based action rises often as a response to place-contestation, the networks of those who have for example political power shape the available frames (Pierce et al., Citation2011). In the Japanese case, the state has traditionally molded the agendas and activities of civil society (Avenell, Citation2010; Ogawa, Citation2009; Pekkanen, Citation2006). Although machizukuri is often promoted as a bottom-up activity, it also includes a great proportion of groups initiated and sponsored by local authorities and does not necessarily lead to a significant shift in power relations (Evans, Citation2002; Sorensen, Citation2012; Sorensen & Funck, Citation2007). The authorities shape machizukuri through institutionalized practices and, in addition, their scope of interests in reconstruction may differ as often ‘people want to rebuild lives and businesses while politicians, engineers and planners will want to rebuild their city’ (Edgington, Citation2011a, p. vii). Local political actors can promote specific place-frames such as a town-level unified identity to support their policy goals (Delaney, Citation2015), as in the case of Yamamoto’s reconstruction slogan, ‘Team Yamamoto with one heart.’ Hence, the post-disaster domains have been described as ‘contested spaces in which opposing groups and interests battle to control the framing of a crisis as a social reality, and so [they] prescribe and justify particular political interventions and visions of an ideal, post-crisis future’ (Gotham & Greenberg, Citation2014, p. 9).

Despite their limited power in actual reconstruction planning, machizukuri relates to how the residents perceive their post-disaster living environments and how they communicate this within the larger context of contested reconstruction framing. Therefore, to proceed from the discussion of whether the machizukuri groups actually have power, this article analyzes in particular how local machizukuri groups’ framing efforts in the town of Yamamoto construct place-based community, legitimate place-based action and how this framing is shaped by sociopolitical and physical context.

Research method and area

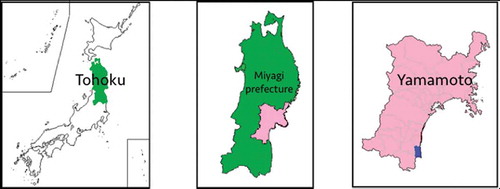

The town of Yamamoto is on the southern border of Miyagi prefecture, approximately 42km from Sendai (). It is a 64.48 km2 coastal rural town dependent on agriculture and fisheries. The town was established in 1955 through the merger of two villages, Yamashita in the north and Sakamoto in the south. In the 3.11 disaster, 635 residents of Yamamoto lost their lives; the tsunami inundated 37.2% of the town, totally destroying 2217 houses and severely damaging 2223 more. Through loss of housing or livelihood, the disaster affected 8990 residents (approximately 54% of the population). Six coastal administrative districts—Iso, Nakahama, Shinhama, Kasano, Hanagama, and Ushibashi—suffered the most significant damage.

Yamamoto already suffered from depopulation and an aging population before 3.11, and these trends were further accelerated by the disaster. By 2018, the population decline was approximately 26.4%, from a population of 16,704 in 2011 at the time of disaster to 12,290 in 2018 (Yamamoto, Citation2018, Citation2011). The population of Yamamoto is also aging rapidly: 35.7% of the town’s population is older than 65 years, ranking it as the fourth-oldest population in Miyagi (Miyagi Prefecture, Citation2015). Hence, Yamamoto offers a case in point of a small rural town in which, despite its seemingly beneficial features of cheaper land, abundant nature, and proximity to Sendai, depopulation and aging still continue rapidly.

The limited academic research about the post-disaster Yamamoto community recovery consists of works mainly in Japanese concentrating on, for example, mental health care and volunteering, but also on local citizen activities and reported changes in the local environment (e.g. Kikuchi & Numano, Citation2014; Masaki, Hashimoto, Higuchi, & Yamauchi, Citation2014; Teuchi, Citation2014; Xue et al., Citation2014). Lately, the prioritization of the new mountainside relocation areas has been taken up in the literature on housing reconstruction (Kondo, Citation2018).

Drawing from eight months of ethnographic fieldwork in Yamamoto between October 2014 to May 2015 during a period when the fukkyū (recovery) period was turning into a more development-oriented fukkō (reconstruction) phase according to the town reconstruction plan, this article analyzes the long-term resident activity that emerged after the 3.11 disaster: the formal town-initiated machizukuri councils in the new relocation areas and a resident-initiated group called Yamamotochō Fukkō wo Kangaeru Jūmin no Kai (Residents’ association for thinking about Yamamoto town reconstruction, hereinafter Doyōbinokai; see Xue et al., Citation2014). Due to the overlapping schedules of formal machizukuri council meetings, this article focuses on two of the three new areas, Shinyamashita and Shinsakamoto. These were the only place-based community groups committed to machizukuri activities in Yamamoto at the time of the fieldwork.

This article draws primarily from the analysis of the newsletters published by the above-mentioned groups (Shinyamashita n = 15, Shinsakamoto n = 19, Doyōbinokai n = 37) and from observations made at their meetings. Analyzed newsletters cover all the publications up to August 2015, tracing the pre- and post-fieldwork developments (they are available at the Kahoku Shinbun (Citation2016) website). Other data includes 24 in-depth interviews in Japanese with local machizukuri actors, machizukuri coordinators, town officials, and also textual documents, such as the Yamamoto reconstruction plan. A thematic analysis was conducted to trace machizukuri participants’ situated rhetorical expressions about ‘activist communities, grievances, and potential actions to solve them in ways that reference socio-spatial relations, especially articulations grounding activism in specific socio-temporal events’ (Martin, Citation2013, p. 98).

The duality of reconstruction policies and machizukuri in Yamamoto

Reconstruction at the municipal level is conducted under the guidelines set by the national government in order to protect the localities from future tsunamis. These guidelines are based on tsunami simulations and estimations of future disaster risks and they include massive land use arrangements, mass relocation from the coastal areas inland (takadai iten) and sea wall building recommendations (Onoda, Tsukuda, & Suzuki, Citation2018). To respond to the lack of housing in areas the town depicts as safe, Yamamoto encouraged takadai iten and has focused its reconstruction efforts mainly on three large-scale inland building projects: the new, urban-style residential ‘compact cities’ (konpakuto shiti) of Shinyamashita, Shinsakamoto, and the Miyagi hospital area (). The idea of densely populated, environmentally sustainable and energy-efficient compact cities was promoted nationally as an urban planning scheme ideal already before the disaster. They are seen as a tool to intensify land use and focus resources in order to handle the problems of aging and depopulation (Sorensen, Citation2010; Suzuki, Citation2010). Now, these areas are portrayed as ‘the new face of the town’ (Yamamoto, Citation2011, p. 13) and ‘the center that the town did not have before the disaster’ (interview with the leader of the town reconstruction section, 2015).

Meanwhile, the town regulated rebuilding in coastal areas by designating ‘disaster danger zones’ 1–3 corresponding to tsunami-inundated areas. This policy forbids building any new residential buildings in the hardest-hit zone 1 on the coast, and elevations are required for new buildings in zones 2 and 3 (Yamamoto, Citation2012) (). Relocation to compact cities was promoted by town policies, for example through buying land from the residents of disaster danger zones 1 and 2 as well as by directing recovery subsidies for those moving to the new areas. Furthermore, resident-initiated group relocation to land outside the compact cities was set to require a minimum of 50 households compared to the minimum of 10 stated in the central government guidelines (CitationMinistry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, n.d.).

Arguably, reconstruction is not considered to end with the completion of the hard side, the actual physical shape and infrastructure of the community, but successful reconstruction also requires considering the soft side, the social community. According to the town official responsible for public housing management, the initial reconstruction in Yamamoto ‘was only hard: To build a house, get people to move in and that’s the end. One sees that in other disaster areas. But that was not wise, so community building was also included.’ In the Yamamoto reconstruction plan, machizukuri is, on the one hand, a synonym for town planning and covers the planning of the so-called hard side—the infrastructure, housing and other elements of the physical environment, which the town was in charge of: ‘Machizukuri for being strong against damages.’ On the other hand, machizukuri was used as a concept of town development to embrace the idealistic goals of the soft side of reconstruction: ‘Machizukuri for living in safety and peace of mind, for making everybody want to live in Yamamoto and for making relationships between people important’ (Yamamoto, Citation2011, p. 4). The formal machizukuri system in Yamamoto was, to a large extent, initiated as a part of this view and set up to function as a soft-side dimension of the otherwise strongly hard-side reconstruction scheme orchestrated from the top down.

The framework for formal machizukuri was established in each new compact city as a town-initiated project managed by consultants from Miyagi University and based on the model of institutionalized machizukuri from Kōbe. However, like in Kōbe after the Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake in 1995, where the top-down directed hard-side planning was started soon after the disaster, incorporating soft-side machizukuri and resident participation into planning took longer (Edgington, Citation2011b; Hein, Citation2001). Participation in the form of institutionalized machizukuri was enabled in Yamamoto only in 2013, after the reconstruction plans were fixed and the construction of the new areas had commenced. Yamamoto did not a have machizukuri system before the disaster and in the post-disaster period, these compact city machizukuri councils remained the only formal machizukuri groups.

Although the idea of ‘Team Yamamoto with one heart’ is promoted in the town’s reconstruction plan on a general level, practically the community rebuilding was to be realized in regional communities (chiiki komyuniti), referring to administrative district communities (Yamamoto, Citation2011, p. 20) and especially supported in the compact cities. The town reconstruction policies of takadai iten and disaster danger zones shaped drastically the spatial reformation of the communities when declaring the coast as unsafe in the name of protection, arguably without much consideration for the remaining residents. This polarized the mountainside and the coast (Kondo, Citation2018) and reflects the duality of the reconstruction plan that draws on one hand from a discourse of town-level unified identity and, on the other hand, the regional divisions within the town.

Compact city machizukuri and the borders of social safety

The town-initiated machizukuri councils aim at involving residents as active stakeholders in community building and in creating a dialogue between the town administration and the residents. Council members are either current or future residents of the compact cities or residents from the surrounding areas and the councils welcome everyone interested in participating. Communication between the local authorities and resident machizukuri councils in compact cities was mediated by the staff of Yamamoto Reconstruction Station (Yamamoto Fukkō Sutēshon), which consisted of a machizukuri consultant from Kōbe, members of Miyagi University, and local staff members. Each council also published its own machizukuri newsletter.

Although the compact city areas as a disaster prevention measure are generally portrayed as good for living (sumiyasui), convenient, and especially safe because of their locations outside the tsunami inundation zone, each council outlines aspects that create insecurity in the new environment, such as the management of flood waters in Shinsakamoto or insufficient transportation and welfare services for elderly residents in Shinyamashita. By pointing out these needs for improvement, the councils encourage residents to participate in public planning:

It is a great meeting to test what I can do myself. Let’s join the council, as many people as possible, with the awareness that “town planning is done by the townspeople as the main actor,” and town residents will join the council one by one and deliver our voice to the town (Shinsakamoto machizukuri council news, Citation2013, p. 1).

However, the control over reconstruction remains in the hands of local authorities. Formal machizukuri functions are restricted within the framework set by the town. They are reduced to, for example, selecting the plants for public parks, organizing community events, or commenting on the details of the shape of the station plaza. This is a potential cause of frustration among the formal machizukuri participants because ‘everything is already decided,’ as noted by a member of the Shinsakamoto machizukuri council. However, explicit criticism is limited to occasional individual complaints by the board members, not least because there seemed to be a mutual understanding about the limits of the system. This was reinforced in the way the reconstruction consultants reminded the participants about the contents of the newsletter: The town sponsors the activities, thus the consultants will check that the contents do not contain anything too controversial.

Belonging to a district

The town reconstruction policies strongly shaped the councils’ place-frames relating to their scope of activities, since the institutionalized machizukuri process was aimed at forming new administrational districts. Therefore, the machizukuri process in Yamamoto has been a tool to realize the pre-tsunami district-based citizen participation model in the form of neighborhood associations, often understood as dominant, exclusive, and a territorially clearly defined form of community organization (Pekkanen, Citation2006; Pekkanen, Yamamoto, & Tsujinaka, Citation2014).

On a more general level, community formation is perceived as highly dependent on the decisions of the district division, because the administrative districts provide the basic geographical area that generates a sense of social belonging. The significance of one’s district community is often reflected in the speech of the displaced tsunami evacuees, who still over four years after the disaster often identified themselves with their original community by introducing themselves as ‘X-san from Y-district/temporary housing, originally from Z-district.’ Due to the official delays, the definition of the spatial scope of community varied in each group as their place-frames drew also from other denominators of spatial community.

The Shinyamashita machizukuri council framed its territorial community exclusively on the new compact city area, frequently discussing the anticipated decision regarding the administrative district that would affect the organization of the district community, the future addresses, community rules and garbage collection. For this purpose, it was considered important that the current or future residents of Shinyamashita would hold the most significant posts in the council. However, as a bigger area with more services, Shinyamashita has attracted significantly more tsunami evacuees from all areas within the town. This mix of residents originating from different districts and starting the community organization from scratch was thought to complicate community building:

[People are moving] from emergency shelters to temporary housing and living in a mass relocation area. From the coastal side, from the mountainside, and also people originally from different districts make community building in one area really difficult (Shinyamashita machizukuri council news, Citation2015, p. 2)

To bind together this heterogeneous territorial community aligning individuals’ interests to activists’ frames (Larsen, Citation2008; Snow et al., Citation1986), a need for welfare services was emphasized in Shinyamashita. This framed the new area mainly as a community for the elderly:

Regarding the town planning for easy living for the elderly [kōreisha ni kurashiyasui machizukuri], we react to the current situation that nearly half of the residents living in the new urban area are over the age of 60. Having the sense of crisis that this “must be done now,” we would like to propose to the town improvement of the living environment and welfare and medical services (Shinyamashita machizukuri council news, Citation2014, p. 1).

This framing was targeted to appeal to the majority of the new residents, but it also reflects the immediate concerns of council members who were mostly older residents themselves. This approach, however, risks excluding other generational interests.

In contrast, the Shinsakamoto machizukuri council perceived community as geographically inclusive of the surrounding areas. The building process proceeded more slowly than in Shinyamashita, and the first residents arrived in April 2015. Shinsakamoto was to merge with Machi district; organizing an independent district was regarded as too demanding a task because of the aging and sparse population of the Shinsakamoto area. The integration of the existing district is said to be eased by the fact that evacuees planning to move to the new area originated from coastal Sakamoto and have social connections to the place: There is a ‘sense of village’ in the Sakamoto area, as one machizukuri council member explained, and in the public meetings the council often defined its scope of action as ‘eight districts of Sakamoto (Sakamoto hachiku) with the new area as its center.’ However, the council members doubted that the merger would raise criticism among the residents of the Machi district. Thus, the reference to greater Sakamoto as an inclusive place-based community not only reflects the pre-tsunami place and community conceptions, but also has been utilized as a discursive tool to seek support from a wider area.

These differences in geographical area framing are partly explained by the composition of the council members. The machizukuri councils are open to everybody to participate, but the Shinyamashita council consists mostly of elderly residents from within the new area. Shinsakamoto, on the other hand, is dominated by participants from the districts surrounding the new area and includes only two tsunami evacuees who will move to the compact city. However, despite the different composition of the members, the common denominator in both councils’ grievances is the framing of the social insecurity created by the unknown. This reflects the need to guarantee peace of mind either exclusively to those within the new area or inclusively to those outside of it as well.

Social insecurity from the unknown

Both areas have public housing rentals as well as privately built houses. As the relocation was based on the individual and not the collective pre-tsunami community applications, people could not choose their neighbors. The final distribution of the slots was done by lottery in the name of fairness, despite the socially fracturing consequences of such practices observed in Kōbe (Maly & Shiozaki, Citation2012). Council members referred to the concern of ‘not knowing the face of one’s neighbors’ as the most acute issue in the area.

Thus, the borders of community are not simply framed as geographical but also social, defining the members who were in the realm of safety. At community meetings, the participants could attach their names to a big map of the new area and thus identify themselves within the socio-spatial network of the community under construction. Those who did not do this were not explicitly excluded from the community as such, but the resulting blank spaces in the map constituted the islands of the unknown and the source of insecurity within the compact city machizukuri councils’ place-frames.

In addition to the uncertainty of one’s future neighbor, councils highlighted the transformation of the living environment from the rural to the urban as another factor causing social insecurity in the form of concerns over privacy:

In addition to the main house, there were a barn and a garage and a spacious garden and fields in the pre-disaster residences. Having a good relationship with one’s neighbors, it was possible to live both mentally and physically at ease, because there was a distance to the neighboring houses. In contrast, when you move to the new urban area, the way you live changes significantly. What is one’s lifestyle in premises with an average of 100 tsubo [approximately 331m2]? What makes you feel uneasy about relocating? (Shinsakamoto machizukuri council news, Citation2014, p. 2).

Finding a balance between maintaining privacy and knowing one’s neighbor seems to reflect also the lessons learned from the reconstruction of Kōbe after the 1995 earthquake and the responsibility of the community to provide a social support network: the spatiality of the threats of social seclusion and solitary deaths posed by fragmentation of communities and the lack of social contacts. In pre-tsunami Yamamoto, for example, the fields and lively streets passing by peoples’ gardens were described as places for naturally occurring community ties. In the compact cities, farming is not possible and gardening possibilities are limited in the small, gravel-coated yards of the densely situated prefabricated houses, so the council members perceived, for example, garbage collection points and parks as potential sites for casual communication leading gradually to a sense of community. To facilitate community building and to avoid social seclusion, the Shinsakamoto council was establishing a ‘tea salon’ for the residents of the Sakamoto area at the time of the fieldwork, as a council member explained:

There is the risk of solitary death and social withdrawal. If people withdraw, we don’t know how that person is doing. In gathering places, we’ll know that, ah, this person hasn’t come for a few days. We get the information. This is why these kinds of places are important. There are no places to go out for these people moving here [to the new areas] and neighbors are people they don’t know. [The tea salon] is for preventing people shutting themselves into their houses.

Thus, when the community is located outside the residents’ private sphere, public gathering places are regarded as the main territory for strengthening the feeling of social safety that constitutes a sense of community together with a sense of belonging and concern for community issues (McMillan & Chavis, Citation1986; Perkins, Hughey, & Speer, Citation2002; Perkins & Long, Citation2002).

Doyōbinokai for the coast

The Yamamoto reconstruction plan painted a future vision for the town using its various local resources and increasing its attractiveness and prosperity. The plan stressed that reconstruction was not something that could be achieved only through administrative power, but through cooperation and a shared vision:

It is essential that each town resident will share this future vision, concentrating the power of participation in machizukuri through love for one’s hometown and through passion. For that, the town’s residents and administration jointly will contribute wisdom and strength together and promote cooperative machizukuri (Yamamoto, Citation2011, p. 4–5).

Despite the rhetoric on cooperation and participation, the reconstruction plan can be seen as subordinating local diversity, and further, critical opinions can be seen as weakening the ethos of the town-level joint reconstruction. In response, a group called Doyōbinokai was initiated in December 2011 by a group of residents from the remaining Hanagama district, particularly to criticize the perceived one-sidedness of the town-level reconstruction vision. Doyōbinokai sometimes defines itself as ‘region building’ (chiikizukuri) to differentiate itself from the town-initiated machizukuri. In January 2012, the formal organization was supported by academic consultants from the Tōhoku Institute of Technology. Later the group continued to function independently, continuing to meet every Saturday, hence the name Doyōbinokai, or ‘Saturday’s meeting.’

The majority of the members are men aged 50–70 from the coastal Yamashita districts of Hanagama and Kasano, some of whom were acquainted before the tsunami and some of whom were united through mutual concerns about the post-tsunami situation. In addition, some women, young locals and residents from Ushibashi district and Sakamoto area also participated. Doyōbinokai organized its own machizukuri workshops and resident survey, which prompted the suggestion to draft a machizukuri plan and submit it to the town administration. The group aims at voicing the opinions of the coastal residents through their monthly newsletter Ichigoshimbun, distributed widely in Yamamoto (see also Xue et al., Citation2014).

Doyōbinokai’s main grievances, motivation, proposed solutions, and mobilizing discourse revolves around spatially-grounded issues related to onsite rebuilding (genchi saiken) of the tsunami-inundated coast. On one hand, it seeks to contest the town’s definition of the coast as an unsafe area. On the other hand, it constructs a newly defined, experience-based community to justify these claims and to build a sense of community in this area.

The abandoned coast

Doyōbinokai’s main concern is that the coast has been abandoned and ignored in the reconstruction process. The group states that this neglect is visible in the overall reconstruction plan, in the slow progress of infrastructural recovery of the coast, in delays with disaster prevention measures such as evacuation roads, and in the prioritization of the compact cities, symbolized especially by the relocation of railway stations inland. Even the town’s inability to clear snowy roads on the coastal side of the old railway in disaster zone 1 is argued to reflect the administration’s ignorance and lack of awareness, as the chairman of Doyōbinokai from Kasano describes:

“The route was decided based on the information from 2011” was the reply from the town hall when I went to ask why the snowplows did not come. In other words, is there a perception in this town that immediately after the disaster up to the present that there would not be residents on the eastern side of the old railway? …This [eastern side] is the Yamamoto I like very much. I would like to somehow return to the town that was easy to live in. That feeling that all residents were thought to be equal. For that, I will continue doing the things that I can. Still, I will continue to think about what is needed for the revival and reconstruction of this town (Ichigoshimbun, Citation2014a, p. 2).

This argument is reinforced by the perceived inequalities in regional reconstruction policies and by a continuous ignorance of the residents’ participation efforts. A core member of Doyōbinokai described how, despite their efforts, their ‘voice is not registered’ and how, if the cooperation had worked, there would not be the need for such frequent meetings and intense activism. The group identifies itself as the mouthpiece of the remaining coastal residents, many of whom voice their discontent and claim that the reconstruction is directed top-down and shaped by the mayor’s personal visions favoring the compact cities. This criticism is strongly embedded in the Doyōbinokai’s framing: at a meeting, four years after the disaster, a reporter from a local newspaper came to interview the group. When asked about the problems of the reconstruction, all members quoted in unison the mayor’s disapproved speech in the immediate aftermath of 3.11 which stated that ‘disaster is a great opportunity for Yamamoto.’

Doyōbinokai repeatedly contests these arguments about the necessity of relocation and its benefits for the revival of the town, as the members see them ignoring the disaster victims. Another core member of Doyōbinokai argued that the massive relocation project accelerated depopulation, prolonged the reconstruction period and turned ‘the natural disaster into an administrative disaster’:

Making the town compact and ignoring the surrounding area based on the mayor’s arbitrary decision has accelerated the decline of Yamamoto by causing population outflow (Ichigoshimbun, Citation2014c, p. 1).

Specifically, the town policies of the three disaster danger zones give a tangible definition of the specific territory of Doyōbinokai’s activities. The zones were regarded as discriminatory, because there is insufficient onsite financial reconstruction support. Furthermore, reconstruction in the zones is supported and regulated at different scales. This means that a neighbor on the other side of the street may face different financial and legislative difficulties to rebuild than the opposite, causing inequality within the community. In addition, zone 3 is argued to be unnecessary, because it is claimed to only cause a negative image for the area without any practical benefits. By questioning the legitimacy and the local authorities’ motives behind the zonal designation, Doyōbinokai sought to align its place-frames to appeal to the residents of all three zones through the construction of abandonment by the town authorities:

Indeed, this is the idea of Yamamoto town. However, if you really think about it, the building restrictions in zones 1 and 2 are applied, but I guess restriction of residence was not the idea of the state. Did the town of Yamamoto have authority over the state? (Ichigoshimbun, Citation2014b, p. 2).

Thus, the tsunami-inundated area is the focus of Doyōbinokai’s activities, which simultaneously construct a post-disaster coastal community.

Experience-based coastal community

During the last few months of fieldwork, Doyōbinokai’s members were preoccupied with preparations for the coastal disaster prevention (bōsai) survey conducted under a slogan of ‘machizukuri for safety and peace of mind’ (anzen, anshinna machizukuri) for ‘the reconstruction of the coastal road (Hamadōri)’ (Ichigoshimbun, Citation2015, p. 2). As the Sakamoto coast remains uninhabited, the survey was distributed to the remaining 596 households in Ushibashi, Hanagama, and Kasano districts. Inefficient measures taken by the town to construct, for example, evacuation roads were criticized and this neglect intensified the insecurity of living in the disaster danger zone. Doyōbinokai argues that an improvement of disaster and evacuation awareness would guarantee fast recovery for the town and prevent population outflow.

When asked in an interview about the motivation to conduct these community activities on the coast, an otherwise always cheery and humorous member of Doyōbinokai suddenly turned serious and recounted his experience on the way back to his house after the tsunami:

I saw many people coming back from the shore. They were physically and emotionally crushed. They were crying. Some said “my mother was gone.” Or others, even if they didn’t say anything, their eyes had changed. I was really surprised that such people got over, climbed the debris to walk towards the mountains. That scene, I really, really don’t want to see again. Remembering that scene makes me really down, even now.

To prevent this from happening, Doyōbinokai arranged practical disaster prevention methods such as disaster evacuation drills to compensate for the inefficient support provided by the town. In addition, intensification of community bonds for mutual help within the community was regarded as important for disaster prevention.

However, this community does not refer only to a pre-tsunami community that was often said to be limited to the immediate neighborhoods or administrative districts. New, shared social identities based on the experience of disaster can emerge (Drury, Cocking, & Reicher, Citation2009; Ntontis, Drury, Amlôt, Rubin, & Williams, Citation2017; Vaughan, Citation2014). Through their framing and activities, Doyōbinokai constructs newly defined borders of a community that are based on ‘the geography of the tsunami,’ seeking to unify the area affected by the tsunami and officially framed as unsafe. The chief monk of the Fumonji temple, who hosts a monthly community café and the weekly Doyōbinokai meetings, told in an interview that after the 3.11 tsunami, ‘the walls of the district communities have been disappearing’ at the coast. Drawing from the widely-acknowledged pre-disaster distinctions between the coast (hama) and the mountain (yama) areas and departing from the district-based sense of community, Doyōbinokai portrays the coastal districts as connected through the tsunami experience:

There is only a graveyard in Shinhama and we heard that no one will return and rebuild their lives there. But anyway, it is important to gather and share information and create dense horizontal ties between the residents of the same town, from Ushibashi in the north to Nakahama and Iso (Ichigoshimbun, Citation2012a, p. 1).

This community is often symbolized by the coastal road Hamadōri, which traverses all tsunami-hit districts, and the activities of Doyōbinokai also aimed at ‘Hamadōri on-site rebuilding’ (Hamadōri genchi saiken) in their machizukuri workshops:

After thinking about the future of Yamamoto and the overall image, Hamadōri’s rebirth becomes a big theme. This workshop will make as its goal an investigation of participatory Hamadōri reconstruction machizukuri (Ichigoshimbun, Citation2012b, p. 1).

By framing the coast as the ‘heart’s hometown’ (kokoro no furusato), Doyōbinokai sought support by appealing to pre-tsunami place attachment of both remaining and relocated residents. Doyōbinokai promoted itself as an advocate of ‘countryside machizukuri’ (inaka machizukuri) that would also consider the connection to history, nature and local lifestyle, represented by the coast. These specific characteristics of the coastal community were contrasted with the new, town-like compact city areas: the chairman of Doyōbinokai expressed his frustration about the spoiled rural landscape and noted that the compact city areas are ‘the general face of Japan, but not the face of Yamamoto,’ in the fashion of furusato discourse about one’s nostalgic, rural country home (Robertson, Citation1988). Through this rhetoric, Doyōbinokai sought support for its claims in general and constructed socio-spatial safety based on the feeling of belonging to the coastal area in particular.

Acting outside the town-sanctioned formal machizukuri councils, Doyōbinokai has built the identity of a geographical and political reconstruction periphery united by the tsunami experience and the feeling of the remaining coastal districts being discriminated against based on their safety. Thus, Doyōbinokai can be seen as an example of a citizen-initiated critical machizukuri group that acts beyond the district boarders based on a shared agenda (Sorensen, Citation2012) and uses the coast and its shared fate as a motivating and legitimizing discursive tool. The main grievances and activities of Doyōbinokai nevertheless are often specified to focus on the limited areas of coastal Yamashita districts of Hanagama, Kasano, and Ushibashi. However, by criticizing the Yamamoto reconstruction plan and its ideals promoted in the reconstruction, Doyōbinokai also constructed town-level identity based on the coastal areas. Doyōbinokai has responded to the official idea of ‘Team Yamamoto with one heart’ by stating that the newly defined shared identity of the coastal community is essential for the town’s recovery and without reconstructing the coast, there is no reconstruction of Yamamoto:

Without rebuilding the tsunami-affected area, there is no disaster recovery of Yamamoto town. The formation of a new urban area called a compact city has accelerated the decline of the population, the falling birthrate and the aging of the population. Ignoring the tsunami-affected area causes turmoil in the eastern districts, compromising the survival of Yamamoto town (Ichigoshimbun, Citation2015, p. 1).

Hence, Doyōbinokai simultaneously embraces the discourses of a place-based community exclusively for coastal tsunami victims and the town-level inclusive community. The group thus argues that current reconstruction policy does not only compromise the lives of the remaining coastal communities, but also that ignoring the recovery of the coast has endangered the secure future of the whole town. These can be seen as spatially grounded claims to redefine the safety status of particular areas within the reconstruction policies. As shown in the discussion above, the spatial and social components in the sense of safety are inherently interconnected, constituting essential building blocks for redefined post-disaster communities.

Conclusions

By analyzing reconstruction machizukuri in the town of Yamamoto through the lens of place-framing, this article shows how machizukuri groups engage in renegotiation and contestation of post-disaster definitions of social and spatial safety. Machizukuri groups as collective actors negotiate the borders of safe community through their place frames characterized by the thematic of socio-spatial insecurity caused by transformations in the living environment. Another prevalent issue is the definition of those included in and excluded from the reconstruction and post-disaster community, either socially or geographically.

In the context of 3.11 disaster, safety and the legitimacy to define it have been discussed in relation to the Fukushima nuclear disaster (Etsuko, Kagemoto, & Akutsu, Citation2016; Vaughan, Citation2015). The complex claims of both spatial and social safety in Yamamoto illustrate how the concept is as acute also in the reconstruction of the tsunami-stricken communities, reflecting the multiple definitions of safety and peace of mind (anzen-anshin) (Walravens, Citation2017). Thus, this article has argued that the long-term community recovery at the local level may be further delayed not only because of the duration of large-scale rebuilding projects, but also due to this re-establishment of safety.

This negotiation of safety is not free from political implications. In Tōhoku, the demand for fast infrastructural recovery, the power relations of the planning process, multiple levels of place-frames promoted by various actors, and the locals’ reorientation in the altered living environment have created controversies and perceived disparities relating to the social or spatial prioritizations within the reconstruction process. Local aspirations to quickly return to pre-disaster lives and locations sometimes are in conflict with grandiose rebuilding plans presented by the government, experts and other ‘outsiders’ (Edgington, Citation2017). This article illustrates that this contention over the reconstruction plans and policies is characterized by the collective struggle to define safety that cannot be measured or defined merely with tsunami simulations or other calculations in a one-size-fits-all manner.

Thus, this article follows in the footsteps of the critical discussions about the massive interventions and ‘building back better’ campaigns after the disaster (Akimoto, Citation2018; Edgington, Citation2017; Nagamatsu, Citation2018), highlighting that they sometimes disregard local communities. In addition to financial reasons, contextual factors such as pre-tsunami place identification or forms of social organization seem to affect the locals' estimations about the perceived risks and constitutes of safety. Furthermore, redefined post-disaster communities negotiate safety in different terms based on shared experience or transformed living environments.

This research is, however, limited to machizukuri groups that involve active residents. As collective actors they seek to promote their specific frame and definition of safety. As Shinyamashita’s place-frame focusing heavily on the welfare of elderly people shows, the frames do not resonate with everybody, such as younger families in this case. The spatial and social sides of safety are also intertwined, yet some of the relocated residents, for example, may consider the new place of residence safe, but feel social insecurity. However, despite their rather limited power in policy-making, machizukuri groups represent the main organized input by the residents into the framing of post-disaster realities. In the research of long-term community recovery, more attention should be paid not only to risk protection, but to local processes of constructing shared conceptualizations of safety.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pilvi Posio

Pilvi Posio is a doctoral candidate at the Centre for East Asian Studies at the University of Turku, Finland. Her dissertation focuses on long-term community recovery after the 3.11 disaster in the town of Yamamoto. Her research interests include anthropology of place, community resilience, disaster recovery and collective action.

References

- Akimoto, F. (2018). The problems of plan-making: Reconstruction plans after the Great East Japan Earthquake. In V. Santiago-Fandiño, S. Sato, N. Maki, & K. Iuchi (Eds.), The 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami: Reconstruction and restoration (pp. 21–36). Cham: Springer.

- Avenell, S. A. (2010). Facilitating spontaneity: The state and independent volunteering in contemporary Japan. Social Science Japan Journal, 13(1), 69–93.

- Barrios, R. E. (2014). ‘Here, I’m not at ease’: Anthropological perspectives on community resilience. Disasters, 38(2), 329–350.

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 611–639.

- Borland, J. (2006). Capitalising on catastrophe: Reinvigorating the Japanese state with moral values through education following the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake. Modern Asian Studies, 40(4), 875–907.

- Chattopadhyay, S. (2012). Framing 3/11 online: A comparative analysis of the news coverage of the 2012 Japan disaster by CNN.com and asahi.com. China Media Research, 8(4), 50–62.

- Cho, A. (2014). Post-tsunami recovery and reconstruction: Governance issues and implications of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Disasters, 38, 157–178.

- Clancey, G. (2006). The Meiji earthquake: Nature, nation, and the ambiguities of catastrophe. Modern Asian Studies, 40(4), 909–951.

- Cornwall, A. (2002). Locating citizen participation. IDS Bulletin, 33(2), i–x.

- Delaney, A. E. (2015). Taking the high ground: Impact of public policy on rebuilding neighborhoods in coastal Japan after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami. In M. Companion (Ed.), Disaster’s impact on livelihood and cultural survival: Losses, opportunities, and mitigation (pp. 63–75). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Drury, J., Cocking, C., & Reicher, S. (2009). The nature of collective resilience: Survivor reactions to the 2005 London bombings. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 27(1), 66–95.

- Edgington, D. (2011a). Reconstruction after natural disasters: The opportunities and constraints facing our cities. Town Planning Review, 82(6), v–xii.

- Edgington, D. (2011b). Reconstructing Kōbe: The geography of crisis and opportunity. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Edgington, D. W. (2017). ‘Building back better’ along the Sanriku coast of Tohoku, Japan: Five years after the ‘3/11’ disaster. Town Planning Review, 88(6), 615–638.

- Etsuko, Y., Kagemoto, H., & Akutsu, Y. (2016). Consensus building in safety and security: A case study of Fukushima evacuees returning home. Journal of Risk Research, 19(7), 983–1003.

- Evans, N. (2002). Machi-zukuri as a new paradigm in Japanese urban planning: Reality or myth? Japan Forum, 14(3), 443–464.

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gomez, C., & Hart, D. E. (2013). Disaster gold rushes, sophisms and academic neocolonialism: Comments on ‘earthquake disasters and resilience in the Global North’. The Geographical Journal, 179(3), 272–277.

- Gotham, K. F., & Greenberg, M. (2014). Crisis cities: Disaster and redevelopment in New York and New Orleans. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hein, C. (2001). Toshikeikaku and machizukuri in Japanese urban planning – the reconstruction of inner city neighborhoods in Kōbe. Jahrbuch Des DIJ (Deutsches Institut Für Japanstudien), 31, 221–252.

- Hein, C. (2008). Machi: Neighborhood and small town—The foundation for urban transformation in Japan. Journal of Urban History, 35(1), 75–107.

- Hirota, J. (2014). Shinsai 4-nen-me o mukaeru tsunami hisaichi no fukkō machizukuri no kadai. [Issues on reconstruction of tsunami affected areas for 3 years since Great East Japan Earthquake]. Noson Keikaku Gakkaishi (Journal of Rural Planning), 32(4), 440–442.

- Ichigoshimbun. (2012a). No. 2. Retrieved December 23,2017, from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/ichigo_02.pdf

- Ichigoshimbun. (2012b). No. 7. Retrieved December23, 2017, from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/ichigo_07.pdf

- Ichigoshimbun. (2014a). No. 21. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/ichigo_21.pdf

- Ichigoshimbun. (2014b). No. 25. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/ichigo_25.pdf

- Ichigoshimbun. (2014c). No. 23. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/ichigo_23.pdf

- Ichigoshimbun. (2015). No. 34. Retrieved December 23, 2017 from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/ichigo_34.pdf

- Ishii, K. (2014). Chiiki shakaigaku ni okeru jūminundō: Machizukuri no jirei kenkyū no bunseki shikaku “komyuniti keiseiron” to “kōzōron” no kouten kara. [Analytical perspectives of regional sociology for case studies of resident’s movement and “machizukuri” in light of an intersection of community formation theory and structural theory]. Chiiki Seisaku Kenkyu, 16(4), 99–119.

- Ito, A. (2007). Earthquake reconstruction machizukuri and citizen participation. In A. Sorensen & C. Funck (Eds.), Living cities in Japan: Citizens’ movements, machizukuri and local environments (pp. 157–171). London: Routledge.

- Kahoku Shinbun. (2016). Fukkō kawaraban. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/#21

- Kikuchi, Y., & Numano, N. (2014). Shinsai ni yoru seikatsu kōdō e no eikyō to jūmin shutai no seikatsuken saihensei: Miyagiken yamamotomachi o taishō to shite. [The influence and community-based rearrangement to the living sphere caused by the earthquake disaster: Yamamoto town in Miyagi prefecture as a subject]. Noson Keikaku Gakkaishi, 32(4), 464–466.

- Kobayashi, I. (2007). Machizukuri (community development) for recovery whose leading role citizens play. Journal of Disaster Research, 2(5), 359–371.

- Kondo, T. (2018). Planning challenges for housing and built environment recovery after the Great East Japan Earthquake: Collaborative planning and management go beyond government-driven redevelopment projects. In V. Santiago-Fandiño, S. Sato, N. Maki, & K. Iuchi (Eds.), The 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami: Reconstruction and restoration (pp. 155–169). Cham: Springer.

- Kusakabe, E. (2013). Advancing sustainable development at the local level: The case of machizukuri in Japanese cities. Progress in Planning, 80, 1–65.

- Larsen, S. C. (2008). Place making, grassroots organizing, and rural protest: A case study of Anahim Lake, British Columbia. Journal of Rural Studies, 24(2), 172–181.

- Lyon, C. (2014). Place systems and social resilience: A framework for understanding place in social adaptation, resilience, and transformation. Society & Natural Resources, 27(10), 1009–1023.

- Maly, E., & Shiozaki, Y. (2012). Towards a policy that supports people-centered housing recovery—Learning from housing reconstruction after the hanshin-awaji earthquake in Kobe, Japan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 3(1), 56–65.

- Martin, D. (2003a). Enacting neighborhood. Urban Geography, 24(5), 361–385.

- Martin, D. (2003b). “Place-framing” as place-making: Constituting a neighborhood for organizing and activism. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(3), 730–750.

- Martin, D. (2013). Place frames: Analysing practice and production of place in contentious politics. In W. Nicholls, J. Beaumont, & B. A. Byron (Eds.), Spaces of contention: Spatialities and social movements (pp. 85–99). Farnham, Surrey: Routledge.

- Masaki, Y., Hashimoto, S., Higuchi, N., & Yamauchi, K. (2014). Miyagiken watarigun yamamotomachi ni okeru hisaisha e kokoro no shien katsudō: Higashinihon daishinsai kara no ayumi to kadai. [Psychological care for the residents of Post-Tsunami Yamamoto-cho in Watari-gun, Miyagi prefecture: The progress and assignments since Great Eastern Japan Earthquake Disaster]. Nihon Hoken Iryo Kodo Kagakukai Zasshi, 29(1), 48–55.

- Matanle, P. (2013). Post-disaster recovery in ageing and declining communities: The Great East Japan disaster of 11 March 2011. Geography (Sheffield, England), 98(2), 68–76.

- Matsuno, H. (1997). Gendai chiiki-shakai-ron no tenkai: Atarashii chiiki-shakai keisei to machi- zukuri no yakuwari [Development of contemporary community theory: Formation a new community and the role of machizukuri]. Tokyo: Gyosei.

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6–23.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. n.d. Bōsai shūdan iten sokushin jigyō [Disaster prevention mass-relocation promotion project]. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.mlit.go.jp/crd/chisei/boushuu/p1.pdf

- Mochizuki, J. (2014). Decision-making, policy choices and community rebuilding after the Tōhoku disaster. Journal of Integrated Disaster Risk Management, 4(2), 103–118.

- Murakami, K., Wood, D. M., Tomita, H., Miyake, S., Shiraki, R., Murakami, K., … Dimmer, C. (2014). Planning innovation and post-disaster reconstruction. Planning Theory & Practice, 15(2), 237–242.

- Nagamatsu, S. (2018). Building back a better Tohoku after the March 2011 tsunami: Contradicting evidence. In V. Santiago-Fandiño, S. Sato, N. Maki, & K. Iuchi (Eds.), The 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami: Reconstruction and restoration (pp. 37–54). Cham: Springer.

- Nii, A. (2017). Process and challenges of the town reconstruction planning and spatial design using the local residents’ collaboration style - base of the experience at Kirikiri district, Otsuchi town, Iwate prefecture. Journal of JSCE, 5(1), 256–268.

- Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1), 127–150.

- Ntontis, E., Drury, J., Amlôt, R., Rubin, G. J., & Williams, R. (2017). Emergent social identities in a flood: Implications for community psychosocial resilience. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 28, 3–14.

- Ogawa, A. (2009). Failure of civil society?: The third sector and the state in contemporary Japan. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Oliver-Smith, A., & Hoffman, S. M. (2002). Introduction: Why anthropologists should study disasters. In S. M. Hoffman & A. Oliver-Smith (Eds.), Catastrophe and culture: The anthropology of disaster (pp. 3–22). Oxford: School of American Research Press Santa Fe.

- Onoda, Y., Tsukuda, H., & Suzuki, S. (2018). Complexities and difficulties behind the implementation of reconstruction plans after the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami of March 2011. In V. Santiago-Fandiño, S. Sato, N. Maki, & K. Iuchi (Eds.), The 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami: Reconstruction and restoration (pp. 3–20). Cham: Springer.

- Pekkanen, R. (2006). Japan’s dual civil society: Members without advocates. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

- Pekkanen, R. J., Yamamoto, H., & Tsujinaka, Y. (2014). Neighborhood associations and local governance in Japan. Hoboken: Routledge.

- Perkins, D. D., Hughey, J., & Speer, P. W. (2002). Community psychology perspectives on social capital theory and community development practice. Journal of the Community Development Society, 33(1), 33–52.

- Perkins, D. D., & Long, D. A. (2002). Neighborhood sense of community and social capital. In A. T. Fisher, C. C. Sonn, & B. J. Bishop (Eds.), Psychological sense of community: Research, applications, and implications (pp. 291–318). New York: Plenum.

- Pierce, J., Martin, D. G., & Murphy, J. T. (2011). Relational place-making: The networked politics of place. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(1), 54–70.

- Prefecture, M. (2015). Kōreika juni [Population aging ranking]. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.pref.miyagi.jp/uploaded/attachment/308945.pdf

- Rausch, A. (2012). Framing a catastrophe: Portrayal of the 3.11 disaster by a local Japanese newspaper. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 12(1). Retrieved May 20, 2018, http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/ejcjs/vol12/iss1/rausch.html

- Reconstruction Agency. (n.d.). New Tōhoku. Retrieved May 24, 2018, from http://www.reconstruction.go.jp/english/topics/20151027125455.html

- Reconstruction Design Council. (2011). Towards reconstruction: “Hope beyond the disaster”. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.cas.go.jp/jp/fukkou/english/pdf/report20110625.pdf

- Robertson, J. (1988). Furusato Japan: The culture and politics of nostalgia. International Journal of Politics, Culture & Society, 1(4), 494–518.

- Sakurai, T., & Ito, A. (2013). Shinsai fukkō o meguru komyuniti keisei to sono katei. [Community development and its problems of disaster reconstruction]. Chiiki Seisaku Kenkyu, 15(3), 41–65.

- Schencking, J. C. (2008). The Great Kantō Earthquake and the culture of catastrophe and reconstruction in 1920s Japan. The Journal of Japanese Studies, 34(2), 295–331.

- Shaw, R. (2014). Post disaster recovery: Issues and challenges. In R. Shaw (Ed.), Disaster recovery: Used or misused development opportunity (pp. 1–13). Cham: Springer.

- Shinsakamoto machizukuri council news. (2013). No. 1. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/shinsakamoto_news_01.pdf

- Shinsakamoto machizukuri council news. (2014). No. 3. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/shinsakamoto_news_03.pdf

- Shinyamashita machizukuri council news. (2014). No. 6. Retrieved December 23, 2017 from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/shinyamashita_news_06.pdf

- Shinyamashita machizukuri council news. (2015). No. 13. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.kahoku.co.jp/special/kawara/pdf/shinyamashita_news_13.pdf

- Snow, D. A., & Benford, R. D. (1988). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research, 1(1), 197–217.

- Snow, D. A., Rochford, E. B., Jr, Worden, S. K., & Benford, R. D. (1986). Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. American Sociological Review, 51(4), 464–481.

- Sorensen, A. (2010). Urban sustainability and compact cities ideas in Japan: The diffusion, transformation and deployment of planning concepts. In P. Healey & R. Upton (Eds.), Crossing borders: International exchange and planning practices (pp. 117–140). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sorensen, A. (2012). The state and social capital in Japan: (Re)scripting the standard operating practices of neighborhood civic engagement. In A. Daniere & H. V. Luong (Eds.), The dynamics of social capital and civic engagement in Asia (pp. 163–181). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sorensen, A., & Funck, C. (2007). Living cities in Japan. In A. Sorensen & C. Funck (Eds.), Living cities in Japan: Citizen’s movements, machizukuri and local environments (pp. 1–36). London: Routledge.

- Suzuki, H. (2010). Tōhoku-hatsu konpakutoshiti” no tenbō [The compact-city concept based on Tōhoku region]. Nihon fudosan gakkaishi, 24(1), 29–33.

- Teuchi, A. (2014). Higashinihon daishinsai to kōminkan: ‘Shinsai-go shakai’ ni okeru chiiki to kōminkan no yakuwari. [The Great East Japan Earthquake and Kōminkan: The Role of Kōminkan in the Society after the Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE)]. Nihon Kōminkan Gakkai Nenpō, 11, 6–11.

- Vaughan, E. T. (2014). Reconstructing communities: Participatory recovery planning in post-disaster japan (Unpublished Ph.D). Cornell University.

- Vaughan, E. T. (2015). Moving beyond social and epistemological ‘Bundan’ in Fukushima. Designing Media Ecology, 3, 052–058.

- Walravens, T. (2017). Food safety and regulatory change since the ‘mad cow’in Japan: Science, self-responsibility, and trust. Contemporary Japan, 29(1), 67–88.

- Watanabe, S. J. (2007). Toshi keikaku vs. machizukuri: Emerging paradigm of civil society in Japan, 1950–1980. In A. Sorensen & C. Funck (Eds.), Living cities in Japan: Citizens’ movements, machizukuri and local environments (pp. 39–55). London: Routledge.

- Xue, S., Kikuchi, Y., Watanabe, H., Numano, N., Yatsu, K., Arikawa, S., & Fukuya, S. (2014). Yamamotomachi de no jūmin sanka ni yoru fukkō machizukuri shien. [Support for resident participation in Yamamoto town restoration planning]. Tohokukogyodaigaku Shingijutsu Sozo Kenkyu Senta Kiyo EOS, 26(1), 1–7.

- Yamamoto. (2011). Yamamoto-chō shinsai fukkō keikaku ~ fukkō to saranaru hatten e ‘chīmu yamamoto’ kokoro o hitotsu ni ~ [Yamamoto town reconstruction plan: Towards reconstruction and further development as “Team Yamamoto” with one heart]. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.town.yamamoto.miyagi.jp/uploaded/attachment/1198.pdf

- Yamamoto. (2012). Saigai kiken kuiki ni kansuru jōrei shikō no oshirase. [Announcement of ordinance on disaster danger zones]. Retrieved December 23, 2017, from http://www.town.yamamoto.miyagi.jp/site/fukkou/318.html

- Yamamoto. (2018). Yamamoto town homepage. Retrieved October 9, 2018, from http://www.town.yamamoto.miyagi.jp

- Yan, W., & Roggema, R. (2017). Post-3.11 reconstruction, an uneasy mission. In R. Roggema & W. Yan (Eds.), Tsunami and Fukushima disaster: Design for reconstruction (pp. 7–18). Cham: Springer.