ABSTRACT

Using photo sessions in combination with three in-depth interviews at a Japanese party called Ankokai in Berlin, we explore how the method of photography along with the participant’s choice of personal objects in the photographs positively influences narrative interviews. Literally meaning “red bean paste meeting”, the Ankokai was originally used as a way for the Japanese gay community to meet in Berlin but nowadays attracts people from all kinds of backgrounds. Keeping the ethnographic research method in mind, our underlying research question asks how translocal categories of migration are reflected in the participants’ choices of personal objects in the photographs. Although larger studies are required to verify this claim, we found that photography can be a strong tool for enacting reciprocity and building rapport in ethnographic research. Furthermore, the participants’ choices of personal objects for these pictures support powerful personal narratives as the research participants’ active participation in the photo session enabled them to reflect on their experiences of migration.

Introduction

If you went to an Ankokai for the first time, you might think you stumbled into an underground club in Tokyo. The “Ankokai,” literally meaning red bean paste party or meeting, was originally founded for the gay Japanese community to meet in Berlin. Predominantly Japanese individuals, as well as people from other ethnic and cultural backgrounds, mingle once a month at this event at the “Club of Polish Losers” (der Club der polnischen Verlierer), a small bar located in the heart of Berlin. Regardless of gender, some attendees wear traditional Japanese clothes such as a kimono or a yukata, while others wear colourful costumes and glittery makeup like costumes from a fantasy production. Immediately upon entering the Ankokai, we were welcomed by various organizers and art performers.

About 3.6 million people live in Berlin, 33.4 percent of which are from a migrant background, meaning that either they or their parents arrived from another country (Rundfunk Berlin Brandenburg [RBB], Citation2018; Statistical Office Berlin-Brandenburg, Citation2018). Among these residents, only 4,169 people have a Japanese background (Statistical Office Berlin-Brandenburg, Citation2018). This small number may influence the marginal attention Japanese migrants in Berlin receive (Reiher, Citation2016, Citation2018) as opposed to Düsseldorf, which is known as “Japan in Germany” (Glebe, Citation2003; Glebe & Montag, Citation2004; Jäger, Citation2017; Kottmann, Citation2017; Montag, Citation2001; Reiher, Citation2016, Citation2018; Tagsold, Citation2011; Tkotzyk, Citation2017). As a result of this low number in combination with a declining interest to live abroad (McCrostie, Citation2017) as exchange students or expats sent by Japanese companies, the discovery of this small Japanese party in Berlin is somewhat surprising. Inspired by the atmosphere of the Ankokai, we sought to uncover details on the backgrounds of some of the participants who identified as part of a marginal community within migrants and Japanese emigrants. In this way, we hope that this small-scale study will contribute to visualizing the diversity of Japanese migration (Befu & Guichard-Anguis, Citation2001; Kojima, Citation2014; McLelland, Citation2018).

Our project began as a way to practice ethnographic research methods in a seminar on translocality instructed by Dr. Philipp Schröder at the Humboldt University of Berlin. Unlike transnationalism, translocality stresses the importance of local aspects in migration. This course targeted Master and Ph.D. students from various disciplines and was aimed at exploring ethnographic methods in translocal spheres. As a result, Natalia Morokhova, a photographer, and I, a Japanologist, worked together to investigate how photography and having participants choose personal objects for these photographs can be used in interview situations during ethnographic field research. It has been previously stressed that photography can be used to empower minority groups such as sexual minorities or migrants (Clover, Citation2006; Jurkowski & Paul-Ward, Citation2007; Kuntjara, Citation2009; Vium, Citation2017). Ankokai participants largely identify with these two minority groups.

As an analytical tool, we applied the concept of translocality to gain a deeper understanding of our participants’ experiences of migration and mobility. Translocality describes “the trans-gression of boundaries between spaces of very different scale and type as well as through the (re-)creation of ‘local’ distinctions between those spaces” (Freitag & Von Oppen, Citation2010, p. 6). Schröder and Stephan-Emmrich (Citation2014) emphasize this distinction by referring to multiple boundaries of transgression. “Among these, national borders are only one type, next to such rather informal separations as those between language codes, urban and rural areas, or rather ‘cultural spaces’” (p. 4). Hence, this concept recognizes that forms of belonging among migrants are not limited to nationality or place but extend to cultural spheres as well. In this paper, we aim to explore some of these spaces or categories of migration through photography and the choices of personal objects in the pictures.

This article primarily focuses on photography and object choice as a method and how this method influences interview situations and outcomes. On a secondary level, we analyse translocal boundaries of three participants in the micro-case study of the Ankokai event, namely Nobu, an artist, chef, and founder of the Ankokai event; Yuko, an artisan; and Takushi, a soprano singer and dancer. Due to the small number of participants in this study, we do not aim to make generalizations regarding experiences of migration or queer mobilities. This paper is instead intended to be seen as an exploration of place-making practices and translocal boundaries that people encounter within migration, and foremost as a study on photography and choosing objects to facilitate storytelling as research tools.

Methodology and research background: The Ankokai, the choice of objects, and photography

It is Saturday night and only a few people have already gathered at the “Club of Polish Losers” to join today’s Ankokai event. Some of the regulars stand in front of a small bar. Sisen, a Japanese DJ who gained popularity in the Japanese underground pop and goth scene, is characteristically wearing a colorful wig, lots of makeup, and a Gothic-Lolita-style short dress and high heels. He is preparing some of the music for tonight’s performance: a belly dance performed by a Japanese woman who studied in Turkey. Before the performance starts, he will mostly play Japanese pop music from the 1980s or prior, sometimes mixed with openings from anime series that are well known to fans of Japanese pop culture. Nobu, the host of these events, greets everyone warmly with hugs and kisses. As ever, he smokes his electric cigarette while waiting for more guests to arrive.

The Club of Polish Losers is located in Mitte, the central district of Berlin located in an area that has become popular for its trendy and unconventional bars and places in recent years. The Club of Polish Losers is no exception. This small, dim bar is equipped with a screen to show movies or video clips, some old furniture, and tables that are sometimes arranged so that artists can sell their products or Japanese food they prepare. The walls are decorated with pictures and paintings that change now and then, and a giant papier mâché nose is hanging in front of the staircase that leads to the smokers’ area in the basement. Shortly before tonight’s performance begins, about seventy guests will gather to watch the show.

Ankokai was originally founded in 2010 by Japanese artist Nobu, who wanted to create a place for the Japanese gay community to meet in Berlin. “There are many places for gays in Berlin, but none for the Japanese gay community,” he revealed during an interview (Interview 14 May 2016). The first events, merely providing a space to talk, took place in a Japanese café and only a few people joined. It was then when Nobu met Piotr Mordel, one of the founding fathers of the Club of Polish Losers, which was a small bar and regular meeting place for the Polish community in Berlin (Gusowski & Mordel, Citation2012). Piotr provided the space and technical equipment for free, so Nobu came up with the idea of having various themed events once a month to attract more people.

By 2016, the party that had once aimed “at the small community of gay Japanese residing in Berlin” (Interview with Nobu, 14 May 2016) had turned into a regular event attracting people from various backgrounds. At most events between March 2016 and February 2019, up to fifty people gathered. These guests include students – many of whom are doing Japanese Studies – artists, fans of Japanese pop culture, Japanese, Polish, Germans, and people from other (mostly European) countries. Although this party started as an event targeted at the gay community in Berlin, people of all sexual orientations have joined with varying reasons to attend. The highlight of each event is a performance by one or several artists, mostly from Japanese backgrounds. Among these performers are DJs, singers, belly dancers, and theatre actors. Sometimes the hosts will even randomly start a karaoke session.

Since I had joined the Ankokai a couple of times before choosing it as a research site, I was already in contact with some of the people regularly going there. Morokhova and I visited the Club of Polish Losers several times over six months to conduct participant observation and have loosely guided interviews with a variety of guests. For this article, however, we focus on three people who were willing to have their pictures taken at home along with several hours of in-depth interviews. As mentioned by Kuntjara (Citation2009), trust is important when working with photographs. Therefore, we asked for written consent and discussed whether to anonymize the participants, location, and all the interviewees and founders at the Club of Polish Losers. We ultimately use their real names and do not anonymize the location, at our participants’ request.

Picturing oneself: Photography and the choice of personal objects as a research method

Photography has long been used in anthropological studies, but often as a way for the researchers to validate or support their analyses (Harper, Citation2004). Holm (Citation2014, p. 5) stresses, however, that the artificial aspect must be considered regarding any type of photography: “Although photographs traditionally were thought of as portraying reality – the simple truth – this is no longer the case among researchers […]. We acknowledge that photographs are constructed; they are made.” Consequently, photography is not merely used by researchers to emphasize certain arguments, but as part of the analysis and as a source of information (Brace-Govan, Citation2007; Schwartz, Citation1989). This use became especially relevant since the emergence of social media that spurred a trend of posting and sharing visual materials (Gunkel, Citation2018; Murray, Citation2015; Tifentale, Citation2015). Utekhin (Citation2017), for instance, argues that pictures on Instagram can be a valuable data source about people’s opinions and social networking practices without influence from researchers. In this study, however, we are conversely interested in the mutual influences between the photographer and interviewee, and in how the process of taking pictures itself can become a vital part of the research. Hence, interaction with the participants and their thoughts on the outcome, components which are likely to remain hidden when analysing only finished pictures, are more relevant here than the photos themselves.

Several scholars have highlighted the positive effects of using photography as an interactive tool during research. By inviting people to present themselves for the pictures or even through the act itself of taking the pictures, photography creates active participation for the interviewees in research projects. It has been found to empower research participants, especially in marginalized groups (Holm, Citation2014; Jurkowski & Paul-Ward, Citation2007; Lodge, Citation2009; Radley et al., Citation2005; Wilson et al., Citation2007; Winton, Citation2016). In these studies, photography is described as giving the participants a voice and a focus on what they consider to be important. Oh (Citation2012) used photography in this way in a study with refugee children in Thailand. The children were asked to take pictures of their everyday lives and, similar to our own study, later discussed the photographs in narrative interviews. In this way, the children were able to influence the focus of the interview and provide their own meaning to the pictures. Similarly, Ohara and Higgins (Citation2017) argue that photography can be an age-appropriate tool which enables young adults and children to participate in studies. It provides them with respect as “highly informed experts of their own lifestyles” (p. 2).

Vium (Citation2017) also referred to this sense of empowerment when he used photography in a study with undocumented migrants in West Africa and Europe. He describes how the presence of the camera helped to establish rapport with the migrants and empowered them as they saw the pictures as a means to present themselves in ways they wanted to be seen or to convey messages they wanted to be heard by a wider audience. Vium demonstrated how the camera managed to “fixate” complex life stories, or moments in time (Vium, Citation2017, p. 177), which is particularly significant when working in the context of migration which emphasises mobilities. In the case of digital photography, this method invites the participants to reflect on themselves and their self-representations as they can see their pictures almost instantaneously (Vium, Citation2017, p. 178). Vium argues that such collaborative portrait sessions are a kind of “shared anthropology” in which the participants are encouraged to actively engage in the analysis of the data provided (Vium, Citation2017, p. 178).

Barker et al. (Citation2012) further stresses that visual methods such as photography can be particularly helpful when conducting research with members of sexual and gender minority communities. This notion significantly relates to our own study with the Ankokai members since this event started as a “gay party” and many of the regular guests identify as part of the LGBTQ+ community. The authors argue that common qualitative research methods, such as interviews, tend to reproduce existing narratives that are spread by the media or the scholar conducting the interview. Relating to Plummer (Citation1995) the authors found that (Barker et al. Citation2012, p. 63) “when it comes to artistic objects, there is a dominant cultural understanding that these do not all have to be the same: that vastly diverse pictures, sculptures and so on can be regarded as equally ‘true’ as representations of the same object or concept.” Consequentially, they stressed that their research participants felt freer to express themselves and come up with their own topics within the follow-up interviews.

We connected with these findings in trying to combine the choice of personal objects and photography as a means to provoke narratives on why the participants chose to present certain objects for the pictures. Personal objects can carry profound messages about their owners. Although we are surrounded by a seemingly endless amount of objects, Miller (Citation1998) stresses that some things matter more than others. What people consume (or not), and what they choose to display to others is linked to their identity and expressions of lifestyle (Miller, Citation1998; Rausling, Citation1998). Meaning given to home and identity are not only displayed through objects but constructed through interactions between people and those objects (Lovatt, Citation2018). Clarke (Citation1998, p. 74) points out that “[w]hile practices of consumption effectively illuminate social categories such as gender, class, ethnicity and age, exploration of the specifics of appropriation and material culture reveals the means by which these externally defined roles are understood and contested.” In studies with LGBTQ+ communities, objects are often attached to symbolic meanings for sexual identities (Gorman-Murray, Citation2012). The symbolic value of objects such as rainbow flags and pictures of naked men or women increases significantly depending on where and how these objects are used.

Images of objects have long been used to convey certain messages such as those painters conveyed with still life images, and this use extends into the digital era as well. In recent years, sharing pictures of objects on social media has become a significant tool for self-expression to a wide audience (Bieling, Citation2018; Sarvas & Frohlich, Citation2011; Song et al., Citation2018). The meaning of personal objects in pictures taken during research has been highlighted in the same way. In the aforementioned study with migrants, Vium (Citation2017) described how an empty laptop case placed prominently in the picture could be a symbol for how the young man in the centre envisioned his future in Europe (Vium, Citation2017, pp. 176–177). “The bag does not contain a computer, but along with the pinstriped shirt, his wristwatch and his composure, it conveys the impression of a man who imagines Europe, his destination, in a particular way and who has prepared himself to engage with this ‘modern world’” (Vium, Citation2017, pp. 176–177). The use of objects in photography can hence emphasize certain narrative messages, either in combination with interviews or independently, depending on the aims of the participants and the researchers.

Despite the many advantages of using photography as a research tool, there are also some disadvantages. Kuntjara (Citation2009) stresses that there are important elements in research that cannot be conveyed through photographs, such as verbal exchange, actions, and behaviours. He also explains that it takes time to establish the trustworthy relationship needed to work with pictures. Moreover, anonymizing people may become more difficult, although technical options are available nowadays. Hence, discussing the purpose and possible reach of the project with the collaborators is important as pictures shared on social media may have a different reach than those published in an academic journal or printed in a magazine. Researchers should also be cognizant that, as Holm (Citation2014) stressed, pictures are constructed and can become manipulative, or made to influence viewers in a certain way. This potential influence is also relevant in our study as our study was explicitly designed to give the participants the chance to be seen as they preferred to be seen. We asked for the interviews and pictures in advance so that the interviewees knew we would visit their private space, giving them the opportunity to prepare their apartments and themselves as they wished. Again, our focus was not on the pictures themselves but on the process of taking them and the narratives that were connected to them.

Since we were visiting the participants in their private spaces, each interview began with being shown around their homes. Following a short self-introduction, we then asked the interviewees how they wanted their picture to be taken. After taking the initial pictures, we then proceeded with the interviewees’ favourite objects. From then on, a conversation evolved about their reasons for choosing these objects: if and how the objects were related to their migration experiences, and what meanings these objects had for the participants regarding home and belonging. Moreover, the participants reflected on the Ankokai event, such as how they were introduced to this event, why they went there, and what it meant to them. Each of the interviews lasted three to five hours, including the photoshoot. Since I speak Japanese and two of the three interviewees felt more comfortable switching between languages, the interviews were held in a mixture of Japanese, English, and German. They were recorded and analysed by coding. In addition to using the photographs as a starting point for our discussions, we used them as an expression of our gratitude for the interviewees’ time as they could keep their pictures afterwards. In the following sections, we will introduce our three main participants and their interviews.

Translocal matters

Nobu

Nobu is the founder of the Ankokai and has lived in Berlin since 2006. He welcomed us into his apartment in Berlin where he lives with his German husband. When we asked him to choose a spot in his apartment for his picture, he sat at a table in his living room, smoking an e-cigarette ().

Although we hardly knew each other before the photo shoot, he seemed comfortable and relaxed, striking various poses during the shoot. We were surprised to see him in everyday jeans and a T-shirt with no make-up, as he could have presented himself in some of the colourful costumes we were used to from the Ankokai. The Ankokai was a kind of job to him, he explained, and dressing up was a part of strengthening existing as well as forming new social networks related to his art, or supporting other Japanese with their daily lives in Berlin. Home, on the other hand, was his private space where he wanted to present himself the way he would usually spend his time at home – without the time-consuming preparations he would undertake before the Ankokai, such as applying make-up or wigs. When we asked Nobu to present some personal objects, he first showed us several pieces he had brought from various places, like a picture book, souvenirs from Japan, and a box in the shape of the Berlin TV Tower. As to the origins of these objects, it turned out that Nobu had moved several times before settling in Berlin. The objects led him to talk about his experiences in the places he used to live in more detail.

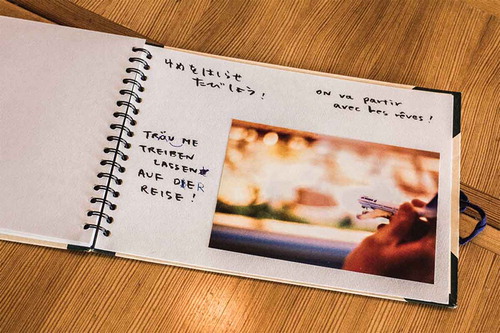

As can be seen in , he chose a book with photos he had taken of a toy plane as his favourite object. The toy plane features prominently in the pictures, with varying and occasionally blurry backgrounds. Descriptions written in three different languages, Japanese, French, and German, were added to the pictures. Some of the sentences were corrected by friends, the corrections still visible on the pages. As we would discover later, the languages were linked to the places where Nobu used to live and leaving the corrections visible could be interpreted as marking his struggle to adapt to these new “homes” while having to learn new languages. After presenting the book for the photo session, he flipped through it to talk about where and why the pictures were taken and how they were connected to his journeys.

Figure 2. Nobu´s personal object: A book with photographs from his travels. Picture taken by Natalia Morokhova.

Nobu was twenty years old when he decided to leave Japan. Two years before, he had had a stable job at a restaurant where he had even become the head chef. In Japan, it is considered ideal to stay at the same company for one’s entire life, so Nobu feared that there would not be much of an adventure ahead of him in Japan. “I became afraid of such a boring life ahead of me and decided to leave for Europe,” he explained (Interview 14 May 2016). In Paris, he worked as a photographer for various fashion magazines and earned his living through art. However, he did not like the fashion community and decided to again leave, this time for Berlin – a city that he had often heard about from his friends who described it as a place where everything was possible. “It’s not that I particularly liked Berlin. But it became famous in a way (uwasa ni natte) and before I realized it, I was here (kichatta ne),” he explained (Interview 14 May 2016).

Although Nobu was told he could easily find a job in Berlin, he experienced the contrary once he arrived. “When all that was left was only two Euros, I sat down, had a beer, and thought, that’s it. Maybe I’ll just die (mō shinde shimaō to omotte). That moment, somebody gave me fifty euros. I pulled myself together and the next day I found a part-time job.” (Interview 14 May 2016). He emphasized that this moment changed his life. He now recalls this experience as his source of confidence and optimism, eventually turning it into his will to create a place for people to come together. Just as Nobu had received support in the past, he wanted the Ankokai to become a source of support for others.

These different places that he had travelled to were embodied in Nobu’s choice for his favourite object. He explained that the plane in the photo book represented his life on the move.

The airplane is like me deep inside. I always go to different directions, other ways. It seems like we do the same every day, but sometimes there are small changes. If you go to other places, you change something. You can change your mind. I like that also for my imagination. To change something is to get new inspiration. (Interview with Nobu 14 May 2016)

He elucidated how these variations were connected to his different occupations, his sexuality, as well as his experience living in different countries. Nobu mentioned how he felt lost several times. He felt outside of the common expectations in Japan. He felt unconfident in France despite making a living with his beloved photography. He had to start all over again in Berlin. These feelings of being new to a place and not fitting in, as a stranger, foreigner, or someone with a non-heteronormative lifestyle, along with the support Nobu received in times of crises, strongly influenced the way the Ankokai was designed. Nobu’s narrative towards these conclusions was strongly influenced by his object choice as he flipped through his photo book featuring the plane, explaining the several stages in his life that corresponded with it. We then asked Nobu his thoughts about the Ankokai event directly.

The Ankokai, Nobu stated, was his way to support people who felt they could no longer continue as he did initially in Berlin. Therefore, he often invites Japanese artists he runs into to perform at his party and expand their networks. When we asked why Nobu had created the Ankokai, he replied: “Well, Japanese people (Nihonjin to iu minzoku) are bad at creating places to meet. When there is one already, they gather. When there is no one who creates this place, they don’t” (Interview 14 May 2016). Interestingly, he was convinced that unlike other Japanese migrants he was able to do this because as an artist he would be used to networking, organizing events, and bring people together. He emphasized that the foremost reason for creating the Ankokai was to bring together members of the Japanese homosexual community:

I’m gay, that’s why I wanted to create a party for gay people. There are many gay parties for Asians, but there were none for Japanese. Unfortunately, not so many gay people are joining anymore, although I wish more would come. (Interview 14 May 2016).

Several categories of Nobu’s migratory experience are reflected in the Ankokai such as sexuality, ethnicity and profession. Although he usually invites other artists and heterosexual guests himself, he ultimately created the Ankokai as a place for the Japanese gay community in Berlin. His descriptions of straying from the norm and searching for people who share his sexual orientation suggest that he wanted to create a place and atmosphere where he could freely live out his “gay identity,” as he put it. For him, Berlin became a place where he could live as an artist and as a gay person without being judged. This freedom was also reflected in his pictures of the airplane, as these symbolized his freedom to travel wherever and whenever he liked. Although he stressed that these categories were the most important changes he was seeking outside his life in Japan, he was also searching for connections to the Japanese community. He mentioned that he did not plan to go to Germany in the beginning and that he views Berlin as similar to other large cities such as Paris and London, or in some regards even Tokyo. Therefore, one could suggest that rather than the imagination of nations, a more generalized image of a city lifestyle is important to him. However, Nobu created the Ankokai to have a place for particularly Japanese people to meet in contrast to other gay Asian parties that already existed in Berlin. On the one hand, this categorization of differences regarding a “Japanese” and “Non-Japanese LGBTQ+ scene” might be linked to the way queer space is constructed in Japan, such as the establishments in Tokyo’s “gay neighbourhood” Ni-chōme, which target either foreigners or only Japanese (Baudinette, Citation2016, Citation2019). On the other hand, Nobu’s self-descriptions resemble Ikeuchi’s (Citation2017) and Noble's (2009) findings that people switch between different identities depending on the situation. Likewise, Nobu foregrounds his identity as an artist, a Japanese, a migrant, or a gay person depending on the situation and how these aspects of identity emerge as translocal categories during his daily experiences. That means that while he might feel unfamiliar as a foreigner in certain situations, he might feel “at home” when being with other artists or within the LGBTQ+ community. Foregrounding certain categories thus allows him to connect or differentiate himself with other groups.

Yuko

Yuko, a fashion designer, invited us to her sharehouse where she lived with alternating roommates. The walls were full of postcards and pictures from friends and roommates, and different objects of the residents were placed throughout the kitchen. She guided us around the sharehouse, talking about the pictures on the walls before she eventually chose the table in the kitchen for her photograph (see ). Her appearance did not differ from when she was at the Ankokai and she did not express any particular reasons for her choice of clothes. Unlike Nobu, she decided not to pose during her first photoshoot. Instead, she proceeded with sewing a new piece, her head down, concentrated on her work. Later she explained that this photoshoot felt more natural for her as this activity was a procedure she would follow almost every day. Nevertheless, she later decided to arrange the setting for the pictures taken during the presentation of her personal object.

Even before presenting her favourite objects and during the photoshoot Yuko discussed her reasons for moving to Berlin. Originally from southern Japan, she studied fashion design in Osaka. Yuko explained that she wanted to come to Berlin to experience something new. Unlike Düsseldorf (Glebe, Citation2003; Glebe & Montag, Citation2004; Jäger, Citation2017; Kottmann, Citation2017; Montag, Citation2001; Tagsold, Citation2011; Tkotzyk, Citation2017) Berlin does not have a large Japanese population, which she enjoyed initially. “You don’t have to live a Japanese corporate life in Berlin and nobody judges you for that,” she explained (Interview 25 May 2016). She viewed this freedom from the Japanese corporate life as a huge difference between Düsseldorf and Berlin, as many of the Japanese residents in Düsseldorf either work for Japanese company branch offices or moved on account of partners who work for these offices. Regardless, Yuko eventually longed to meet people with a shared cultural background and therefore joined the Ankokai shortly after moving to Berlin in 2013. She became friends with a Japanese DJ who arrived around the same time: “We had to renew our visa at the same time, get the work permit, and find a job … It’s so much easier if you have somebody to consult and [rely on] for emotional support,” she explained. Similar to Nobu, Yuko was actively searching for connections to the local Japanese community.

Yuko’s second reason for joining the Ankokai was revealed in her object choice. She chose a needle set and a suitcase, which are shown in the and .

Yuko bought the set of needles in Japan and pointed out their high quality. This choice led her to talk about her profession as a designer and her thoughts on fashion. She used the needles to convert various fabrics into clothes that held a deep meaning for her. Choices of clothing, she argued, are a means to express identity and sexual orientations, especially in sexual minority and transgender communities. Therefore, Yuko was always attracted to the LGBTQ+ scene, not because of her own sexual orientation, which she did not explicitly talk about, but because she discerned that people from the transgender community often use fashion more purposefully than people living a heteronormative life.

There are many transgender clubs close to where I lived in Osaka. Also, I studied fashion design and there were, in comparison to other studies, many transgender people. I really like how they dress and how they express themselves with their clothing. In Japan, clothing is always like a uniform. Children wear school uniforms; businessmen wear suits. It’s like a second skin (wie eine zweite Haut). It’s their social skin. Transgender people are much more creative and open regarding the way they dress. (Interview 25 May 2016)

As a fashion designer, this experimental way of dressing attracted Yuko to the Ankokai. For her, clothing was a way to cross national, gender and even professional boundaries, and this sense of translocality is embodied in her object choice of sewing needles used to make clothing.

When Yuko discussed what she considered to be one of the main differences between Germany and Japan, she again referred to clothing in terms of style differences. She perceived that Germany had greater freedom in regards to clothing choice, where uniforms were the exception rather than the norm. However, she thought this perception might be influenced by the clothing culture in Berlin where many young and experimental people reside. The way Yuko describes clothing evokes the above-mentioned symbolic value of objects overall, as such choices of consumption can be used to express lifestyle, sexual orientation, and identity (Lovatt, Citation2018; Miller, Citation1998; Rausling, Citation1998).

When we asked Yuko about her reasons for choosing the needle set in detail, she distinguished herself from most of the other Ankokai participants.

I’m not an artist. I am a designer. I am not coming up with my own ideas, I try to make things according to the wishes of my clients. I am more interested in producing things rather than coming up with something new. What I do is a handcraft to me. (Interview 25 May 2016)

As an artisan, she wanted to make sure to always carry the right equipment with her. She described this equipment almost like a business card (meishi). Whenever she would show the needles to people, they could guess her profession.

In addition to the needles, Yuko chose a suitcase as a symbol of her life. At the time of her interview, it was already packed since Yuko would soon return to Japan for several years. She often carried this same suitcase around the Ankokai filled with products to sell. The way she prepared for the suitcase photograph differed a lot from the one with the needles. She opened the case on her bed so that the viewer of the picture would be able to see what was inside: other things she had handmade, a portfolio, and yarn she would need for her work. She took out her laptop and placed herself next to the suitcase, directly facing the camera. The picture conveys how she is ready for the journey, her laptop resembling connections to different places and time zones.

Sitting next to her suitcase, she explained:

I always feel like being on a journey. The city where I am is not so important to me – the journey is. That’s why the suitcase is important to me and the things that are inside. To be honest, I don’t like the finished products that much and I don’t know how to sell them, but I love the process of making them. In Japan, it’s easier to produce because people tell you what they want and I know the material. But I would love to come back to Berlin during the summer to sell these products here [in Berlin] as well. (Interview 25 May 2016)

Several boundaries and categories of migration are evident in this quotation. On a meta-level, Yuko describes the journey in contrast to the arrival and the process of creating in contrast to the finished product as being the most important component of migration and production to her. Different boundaries influence her practical daily life as well. Yuko notes that city choice is not that important to her which may be evident in her previous residence choices, all of which were urban. On the other hand, she focuses on local and national differences, which she mostly makes relevant to her possible customers. This emphasizes the significance of her profession for her identity and her experience as a migrant.

In a study on Japanese service professionals in Hong Kong, Aoyama (Citation2015) explained that migrating businesspeople may face difficulties understanding their clients’ preferences in their new places of residence. At the same time, they may profit from their own ethnic identity as “being Japanese” may evoke a certain style of artisan. In the cases described by Aoyama, this kind of exoticism helped the businesspeople to establish their services as a brand related to their ethnicity. Yuko stressed similar challenges in adjusting to a new market while profitably distinguishing herself as a Japanese artist. Further, she sees her profession in contrast to the other participants at the Ankokai. This is a common feature of identity or community formation in general as this formation is usually also done in differentiation to “others” (Morris, Citation2012, p. 45). In addition to representing journeys in several ways, such as travelling or the “journey” of making a product, Yuko’s suitcase symbolized a connection between the various spheres to which she would travel throughout her life, such as different countries and cities, art and artisanship, and various types of events and markets.

The benefits of interviewees’ active participation in photography as well as object choice were evident throughout Yuko’s interview as she was able to express her views on her profession as a productive artisan as opposed to a creative artist when describing her choice of the needle set. Further, her object choice of the needle set enabled her to reveal the importance of clothing to her as well as her sense of travelling through boundaries. She carefully thought about which objects to choose and how to narrate her experiences before we visited her. She knew that we wanted to discuss her views on the Ankokai and her experiences of migration and she therefore decided to visualize the meaning of her profession in the form of the needles and to stress her life on the move in the form of the suitcase.

Takushi

Takushi is a Japanese DJ, dancer, and soprano singer who was trained in Italy for several years and has lived in Berlin since 2013. At the time of the interview, he lived by himself in a small flat. Just like at the other interviewees’ places, the walls of his apartment were decorated with pictures he drew as well as photographs. He was the only interviewee to explain that he had thought long about what to wear and how to present himself. In the end, he chose his favourite T-shirt but did not state any particular reason for it other than its looks. It was clear during the whole photoshoot that he was used to presenting himself as he tried different poses, his eyes mostly fixed on the camera. He chose to sit casually in a chair, presenting a toy sword as his favourite object ().

Figure 6. Takushi with his favourite object – a Japanese toy sword. Picture taken by Natalia Morokhova.

From the beginning of the interview, Takushi seemed excited to present himself and his views, an excitement which is also reflected in his room as he had voluntarily spread some of his personal things around his apartment as though to tell the story of his journeys. Especially when we asked him to present his favourite objects, he was pleased to talk about their association with his identity.

I bought this [toy] katana in Berlin. It’s from the anime One Piece which I love. I like this sword so much because of the design. It fits my performances and I love the otaku culture – I’m a freak! (Interview 24 May 2016)

He explained that he loved manga, anime, and video games to the extent that he was considered an otaku (fan or nerd) in Japan. This categorization in Japan added to his feelings of being an outsider. Yet in the interview, he seemed to use the expression “I’m a freak” with pride to underline that he could be celebrated for his differences. He used the sword as well as costumes during his performances and was invited as an artist because of these differences. To him, the sword symbolized being accepted as an individual and as an artist.

More important than the sword, however, was a second item he chose: a movie that described a world where homosexuality would be the norm and heterosexuality was treated abnormally. It was after showing us this choice that he started to talk about how he had decided to move to Berlin and how he had felt in Japan. He reiterated that being homosexual was a significant part of his identity, which he felt unable to express in Japan. These concerns are shared by many people identifying with the LGBTQ+ community in Japan, as discrimination against sexual minorities remains a problematic issue (Lunsing, Citation2005; McLelland, Citation2009; McLelland & Suganuma, Citation2009; Yamashita et al., Citation2017). Takushi’s father did not want to believe him when he had his coming out and he was bullied at high school to the extent that he considered suicide. For him, life in Japan would mean adapting to the majority. He therefore searched for a place where his sexuality would not be judged as “abnormal.”

A number of scholars have stressed the significance of mobilities for people identifying with LGBTQ+ communities, as the perception of “safe places” may differ tremendously depending on sexual orientations and whether these orientations are expressed or not (Gorman-Murray & Nash, Citation2016; Nash & Gorman-Murray, Citation2014; Waitt & Gorman-Murray, Citation2011). This finding may explain Takushi’s decision to move to Berlin when he found it advertised on a Japanese website as one of the best cities to live as a gay person. While we watched the short movie together, he emphasized that “it makes people understand what it means to be gay” (Interview 24 May 2016). Relating to scenes in the movie, he referred to situations he had experienced himself and expressed his relief in being able to openly show and talk about his sexual orientation, something he could not do in Japan.

I love life in Berlin. In fact, I enjoy it much more than life in Japan because I’m gay. Japan is a conservative country and the gay scene is very small. […] Before I decided where to go, I searched online ‘where is an openly gay culture?’ And I found England … Thailand … and Berlin. I went to Berlin because it was the easiest place to get a working holiday visa. (Interview 24 May 2016)

The main boundary Takushi faced in Japan was his sexual identity. Hence, overcoming this boundary became his ultimate reason to migrate to Berlin, although financial reasons also supported his decision such as the cost of living and access to work permits. Takushi mentioned, however, that he was not going to the Ankokai to mingle with the LGBTQ+ community, although he joins them during other events like Christopher Street Day. For him, the Ankokai is a place where he can present his art and meet his friends. He also mentioned not being very involved in the gay scene in Berlin. “I don’t know many gay people and I don’t want to go alone to such parties” (Interview 25 May 2016). Clearly, Takushi does not consider the Ankokai to be a gay party, although Nobu’s original aim was to create a place for the Japanese homosexual community.

Regarding the flow of the interview, the photoshoot supported the warm-up phase well. The sword showed that Takushi felt marginal in many ways, and not only regarding his sexual identity. This topic might not have emerged without having him choose different objects. Even more than the sword, the movie made him talk about his experiences in detail as he compared his past to the scenes. Nevertheless, the movie demonstrated the limits of our method as the lighting did not allow us to take pictures for presentation and the symbolism of the “object” was therefore in the narrative rather than in the visuals. Despite these limitations, the interviewees felt a level of comfort by being able to actively participate in the photo shoot.

Identity, migration, and the Ankokai as a translocal space

During the interviews, it became clear that several categories of migration were influencing the perceptions of belonging for our participants. For Nobu and Takushi, their sexual identity was an important factor. Both of them were trying to escape the conservative norms of their homeland when they decided to migrate. Neither of them particularly cared where to go as long as they could enjoy the freedom of expressing themselves. Takushi even specifically searched for a place to live comfortably (sumi yasui) as a gay person. In that sense, it did not matter whether he would have lived in London or Germany. Here, it is noteworthy that he was referring to urban regions, as the lifestyle he was searching for may have differed in rural areas. The way Takushi selected a place to live reflects findings in queer mobility studies that stress the significance of migration for people of a sexual minority (Doan, Citation2016; Gorman-Murray & Nash, Citation2016; Nash & Gorman-Murray, Citation2014). For example, migration is significant when travelling to improve quality of life, such as seeking the openness and anonymity of an urban environment regarding rural to urban migration (Doan, Citation2016; Waitt & Gorman-Murray, Citation2011; Weston, Citation1995). However, sexual minorities may have limited options as to where to settle or even how to commute in daily life due to safety concerns (Baudinette, Citation2016; Gorman-Murray, Citation2012; Waitt & Gorman-Murray, Citation2011).

Although neither Takushi nor Nobu described the Ankokai as the “gay party” that Nobu had originally intended, sexual identity is still an important aspect of the event as one of the owners of the Club of Polish Losers, Piotr Mordel, has emphasized. He described the Ankokai as “a place where people who want to be different can be different. [The people coming here] are like refugees, because in Japan they cannot live the way they want” (Interview 14 May 2016). As stressed by the above-mentioned scholars as well, Takushi’s and Nobu’s cases show how sexual orientation can be a translocal boundary that heavily influences why and where people move, and where they feel comfortable and safe.

Unlike Takushi or Nobu, Yuko did not mention her sexual orientation during the interview or state it as a reason for her migration. However, the search for openness towards their preferred lifestyles can be seen as a significant reason for moving to Berlin for all three interviewees. Yuko’s main reason to move from Japan was to live in a social environment that she perceived as more open. In that sense, she resembles lifestyle migrants described in Aoyama’s (Citation2015) study of Japanese migrants who tried to escape the strict Japanese work-life by starting new businesses in Hong Kong. None of the three interviewees found themselves accepted in Japanese society – either because of their sexual orientation or their occupations as artists or artisans which deviate from the “norm of Japanese corporate life.” Interestingly, McLelland (Citation2004) stated that for a long-time transgender people had only limited options of employment in Japan, which were, next to prostitution, mainly in the entertainment industry and that capitalized on their different appearances. As stated by Barker et al. (Citation2012), art is a realm in which people and their opinions may deviate from socially constructed norms. The topic of transgender is often featured in Japanese media and gender plays nowadays, in addition to cross-dressing being common in some Japanese music genres such as Visual Kei (Heymann, Citation2014; Mcleod, Citation2013). However, Takushi and Nobu did not express a strong link between their sexual orientations and their professions as artists. Yuko, on the other hand, stressed that her interest in transgender communities was linked to her impression of their creativity regarding clothing, which may stem from the aforementioned media focus on art and transgender.

The interviewees’ professions reveal another translocal boundary that influenced where they would settle and why they particularly chose the Ankokai event as a place to gather. All three of them referred to their life either as an artist or an artisan and the differences concerning their occupation in their country of origin. The people gathering at the Ankokai are mostly artists, and the three interviewees mentioned that even in Japan or other places they had lived prior to Germany they took part in the art scene, regularly meeting with those involved. In this way, their professions represent a translocal category as parts of their jobs may not differ too much from their home countries. The level of this difference inevitably depends on the type of profession, as some jobs require more language skills than others. The professions of the interviewees (chef, soprano singer, and artisan) allow for a greater degree of freedom that may have helped them to feel more comfortable in Germany.

Despite the variety of translocal categories influencing migration, nationality and ethnicity remain important factors. This importance emerges through legal questions such as the ability to acquire a visa or legally work in a foreign country. However, as Aoyama (Citation2015) notes, ethnicity can also be used as a cultural asset that allows people to differentiate themselves from others offering similar services. Utilizing the Ankokai as a particular Japanese space provides opportunities such as networking. As Yuko pointed out, the event enabled people of Japanese descent to meet likeminded people in similar situations as them, sell their products, or “test” their art to see what kind of performances or products were received well from the audience, before presenting their art in front of a more general audience. These networking opportunities are an especially important feature of the Ankokai as many of its Japanese guests were not fluent in German and some of them faced hardships expressing themselves in English. Labelling the event as “Japanese” further allowed the participants to distinguish their performances and expectations from other offers in multicultural Berlin. Although this kind of marketization led to an increase of visitors interested in Japanese culture or “Cool Japan” (Tamaki, Citation2019; Valaskivi, Citation2013), it may have shifted the focus of the event away from the gay party Nobu had envisioned, as he described in his interview.

The above-mentioned examples show how even a small event like the Ankokai reflects translocal categories and the categories of identity of its guests. As mentioned earlier, the three participants were chosen because at the time of this study they were core members of the Ankokai. They regularly attended as guests, performers, or were involved in the organization of the event through serving drinks or cleaning up. Nobu’s comments reveal that his original idea of the event changed due to the guests participating. He stressed that he wanted it to be a “Japanese gay party” and since many of the guests identify with the LGBTQ+ community, for them the Ankokai is just that. However, with various people joining and introducing new backgrounds, the expectations changed and the Ankokai became a simultaneous underground art event and meeting place for like-minded people. With their diverse backgrounds, the guests transform the event according to their own experiences and desires. The Ankokai can be a Japanese party, a gay party, a marketplace, a network for artists, an art event, or all of these places simultaneously, just as “categorical identities” vary and intersect with one another (Gorman-Murray & Nash, Citation2016).

Evaluation of the research method: Photography and the choice of objects

Overall, taking photographs of our interviewees and having them choose objects of importance to them yielded positive effects despite some disadvantages. As Vium (Citation2017, p. 172) noted, photography can be “a concrete means of establishing rapport” with research collaborators. Trust is significant in individual photo sessions as pictures are usually private and reveal a lot of information about the protagonists. Whereas research proposals and hypotheses in scientific journals may remain vague, taking pictures produces an immediate result and thus supports reciprocity as the researcher can use the picture as a way to thank the participant, and rapport-building as mutual trust and communication between the people involved is key when taking pictures.

All our interviewees seemed comfortable before the camera, possibly due to their involvement in the art scene and previous experience with photography. This added to the value of our photo sessions as they were looking forward to the results of the pictures, which they could eventually use for their own purposes. Although we expected our interviewees to dress up for the pictures like they would at the Ankokai, we were surprised that they welcomed us in everyday attire. Nobu commented that the pictures were taken at home and the clothes he chose would be those he wore in his private time. Conversely, the Ankokai was a networking opportunity and dressing up was entertainment for himself and the guests there.

Although the photoshoots and the pictures themselves were helpful in establishing rapport and practicing reciprocity, the interviews benefited even more from the combination of the photoshoot and the choice of personal objects. As has been noted by other scholars (Lovatt, Citation2018; Miller, Citation1998; Rausling, Citation1998), objects and interactions with them reveal a lot about the lives of their owners. Our interviewees clearly thought about what objects to present before the interview and they took the photoshoot as a chance to reflect on their life. These object presentations within the photoshoot produced powerful narratives. Takushi and Nobu wanted to discuss their sexuality during the photoshoot. Although this desire was not evident through the objects or pictures alone, it seemed easier for them to discuss their sexuality while skimming through a photobook or watching a movie. Similarly, we may not have discovered Yuko’s views on the differences between her profession and other artists at the Ankokai if she had not chosen the needle set. Her suitcase also became a powerful symbol for her life on the move.

Having the interviews at home was also advantageous as the interviewees could freely show us the objects they had considered significant for their narratives and photographs. They had switched between different objects before they chose their favourite. For instance, Yuko decided to show us her suitcase after talking about the significance of the needles and Takushi showed us his favourite movie after presenting a toy sword for the picture. Although the apartments of the interviewees could have been part of a rich analysis, we decided to concentrate only on the objects that our interviewees chose voluntarily and consciously. This concentration not only created powerful narratives as the interviewees reflected on themselves before and during the interviews, but it also supported the natural flow of the interviews as Yuko, Nobu, and Takushi used the objects to highlight several episodes from their lives or symbolize their journeys.

Many of the objects brought border-crossing experiences to the foreground as well. This quality was the most apparent in Yuko’s suitcase as it would travel everywhere she went and was full of things symbolizing her profession, her hobbies, and people important to her. She would also take it to the Ankokai to carry the products she wanted to sell there. In a sense, the suitcase connects different parts of her life and could be seen as a translocal object in itself. The needle set was originally from Japan and stood for her profession as it is particularly practiced in Japan because, according to Yuko, she could not find such needles elsewhere. Nobu’s photobook was made in Paris and travelled with him to Berlin. His different places of residence were reflected in the descriptions added to the photographs written in Japanese, English, and German. Only Takushi chose an object that he acquired in Berlin, although his katana from a Japanese anime is strongly connected to Japanese (pop) culture. Like Yuko, he took this object to the Ankokai, which demonstrates the bond between his private space and the club where he performs as an artist. The movie he chose shows the weight of sexual identity for him. As a movie that can be watched online, it transgresses the usual boundaries of nations or localities. Interestingly, despite knowing that our interviews would revolve around their connections with the Ankokai, only Takushi chose an object that obviously stood for his sexual identity in this choice of the movie. However, the interviews revealed how Yuko’s and Nobu’s objects were also connected to the LGBTQ+ community. Yuko’s way of making clothes was strongly inspired by transgender communities and Nobu’s photobook was deeply connected to his journeys that involved searching for and finding a partner in Berlin. Switching between objects during interviews at home supported the interviewees’ narratives in ways that might not have been possible in a more formal setting. However, photoshoots at home also presented challenges. Many possible interviewees declined because they did not want their pictures to be taken, and also because they refused to invite people they barely knew into their home.

These photoshoot experiences show that although we did not let our interviewees take the pictures themselves as done by Oh (Citation2012), our method encouraged them to express themselves and was helpful in establishing rapport as suggested by Vium (Citation2017). These advantages are especially true in combination with the choice of objects. Nevertheless, we assume that other narratives or aspects of their identities were muted by our methodological choice. Some aspects, such as language barrier, financial, or visa issues, may be difficult to visualize. Therefore, even if our interviewees would have liked to talk about these topics, they might have refrained from doing so as the topics did not fit into the photographs being taken. Being able to show themselves as they wanted to be seen definitely empowered the interviewees through enabling them to talk about what they considered important. However, this may also mute aspects of their experiences that they would not like to share. This result does not mean that these muted aspects are not equally important towards drawing conclusions for a more general understanding of migration.

Conclusion

In this micro-study, we explored translocal categories of migration through narrative interviews using photography and the choice of personal objects with three Japanese migrants in Berlin. The research participants named several categories that significantly determined their migration experiences. In addition to the boundaries created by nation-states and ethnicity, as visa and work-related regulations influenced where they would settle and language remained a challenge, other categories such as their professions as artists or artisans, subculture, or sexual orientation significantly influenced where Nobu, Yuko, and Takushi settled. Interestingly, despite the participants’ wishes to escape certain aspects of Japanese culture, they longed for a particularly Japanese space and foregrounded certain aspects of their ethnic identity throughout their interviews. These categories and the participants’ related roles are reflected in the Ankokai event as each participant shaped the party through their presence and practices, such as performing, networking, or selling goods. The chosen methods of investigation for this topic of translocality facilitated these findings and were overall appropriate. We found that photography and the objects chosen for self-representation supported strong, individual, and intimate narratives that might otherwise not have been mentioned. Therefore, we hope that this micro-study of a Japanese party in Berlin illuminated the diversity of Japanese migrants who have emigrated outside of the common short-term international programs such as student exchange and company training.

The choice of personal objects for the pictures influenced the narrative interviews positively. In our small sample size of only three people, we found that stimulating and intimate topics emerged through object choice, which we could explore further. It also gave the interviewees a chance to consider the interview and their life experience beforehand as they could prepare how they wanted to be seen. As the participants were active in the art scene, they were already used to such kind of self-representations. The outcomes of this project reflect findings from Barker et al. (Citation2012) who noted that artistic methods helped members of the LGBTQ+ community to escape the reproduction of widespread narratives. Although this approach might have muted aspects of the interviewees’ migration experiences and therefore has to be treated with care, it gave them the opportunity to foreground other aspects that were important to them. The professional photographs were also useful as a reward for their participation. Thus, we found that photographs and the choice of personal objects in photographs empowers research participants, and the result supports researcher-participant reciprocity.

Overall, photoshoot methodology in research enables people to talk about personal and intimate issues and express themselves in an individual manner. This quality is especially apparent when working with marginalized people or minorities as they can influence the interviews significantly by their object and presentation choices in the photoshoot and thus stress aspects that might not be addressed in usual interview formats. In our case, we were able to extract the illuminating narratives of Japanese migrants identifying with a sexual minority group in Berlin, where Japanese migration is less visible than in other cities. Ultimately, a larger sample size, such as one including people from other professions or other cultural backgrounds, would be needed to investigate whether photography and having the participants choose personal objects to talk about could benefit other interview situations.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank my interviewees and the participants at the Ankokai in Berlin for letting us explore their worlds and for sharing their stories with us. Further, I am grateful for Dr. Schroeder from Humboldt University for letting me take part in his research class and for his valuable comments. I would also like to express my gratitude to Prof. Isaac Gagné and two anonymous reviewers for their encouraging and insightful feedback from which this article benefited tremendously.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Julia Gerster

Julia Gerster (PhD, Freie Universität Berlin) is an Assistant Professor at the International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS) at Tohoku University since 2019. Her main research interests include the dynamics of social relations after disasters, recovery processes, and the handling of negative heritage in identity and community building. She recently published articles on “Hierarchies of affectedness: Kizuna, perceptions of loss, and social dynamics in post-3.11 Japan“ (International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2019) and “The Online-Offline Nexus: Social Media and Ethnographic Fieldwork in Post 3-11 Northeast Japan“ (ASIEN, 2018).

Natalia Morokhova

Natalia Morokhova is a photographer and entrepreneur based in Berlin. After graduating from a law school in Russia, she studied at the Institute for Asian and African Studies at Humboldt University, Berlin. Entrepreneurial journeys through modern Pakistan, China, and other parts of transforming Asia together with a deep interest in people's behavior and motivation shaped her visual approach in photography. In her images, she explores how the personality interacts with the environment.

References

- Aoyama, R. (2015). Global journeymen: Re-inventing Japanese craftsman spirit in Hong Kong. Asian Anthropology, 14(3), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1683478X.2015.1115578

- Barker, M., Richards, C., & Bowes-Catton, H. (2012). Visualizing experience: Using creative research methods with members of sexual and gender communities. In P. N. Constantinos (Ed.), Researching non-heterosexual sexualities (pp. 57–80). Ashgate.

- Baudinette, T. (2016). Ethnosexual frontiers in queer Tokyo: The production of racialized desire in Japan. Japan Forum, 28(4), 465–485.https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2016.1165723

- Baudinette, T. (2019). Gay dating applications and the production/reinforcement of queer space in Tokyo. Continuum, 33(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2018.1539467

- Befu, H., & Guichard-Anguis, S. (Eds.). (2001). Globalizing Japan. Ethnography of the Japanese presence in Asia, Europe, and America. Routledge.

- Bieling, S. (2018). Konsum zeigen: Die neue Öffentlichkeit von Konsumprodukten auf Flickr, Instagram und Tumblr [Showing consumption: The new public sphere of consumable goods on Flickr, Instagram and Tumblr]. Transcript.

- Brace-Govan, J. (2007). Participant photography in visual ethnography. International Journal of Market Research, 49(6), 735–750. DOI: 10.1177/147078530704900607

- Clarke, A. (1998). Window shopping at home: Classifieds, catalogues and new consumer skills. In D. Miller (Ed.), Material cultures. Why some things matter (pp. 73–99). The University of Chicago Press.

- Clover, D. E. (2006). Out of the dark room: Participatory photography as a critical, imaginative, and public, aesthetic practice of transformative education. Journal of Transformative Education, 4(3), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344606287782

- Doan, P. (2016). You’ve come a long way, baby: Unpacking he metaphor of transgender mobility. In B. Gavin & B. Kath (Eds.), The Routledge research companion to geographies of sex and sexualities. Routledge Handbooks Online.

- Freitag, U., & von Oppen, A. (2010). Introduction: ‘Translocality’: An approach to connection and transfer in area studies. In U. Freitag & A. von Oppen (Eds.), Translocality. The study of globalising processes from a southern perspective (pp. 1–24). Brill.

- Glebe, G. (2003). Segregation and the ethnoscape. The Japanese business community in Düsseldorf. In R. Goodman, C. Peach, A. Takenaka, & P. White (Eds.), Global Japan. The experience of Japan’s new immigrant and overseas communities (pp. 98-115). Routledge.

- Glebe, G., & Montag, B. (2004). Düsseldorf. Nippons Hauptstadt am Rhein [Duesseldorf. Nippon’s capital at Rhine River]. In H. Frater, G. Glebe, C. Von Looz-Corswarem, B. Montag, H. Schneider, & D. Wiktorin (Eds.), Der Düsseldorf Atlas. Geschichte und Gegenwart der Landeshauptstadt im Kartenbild [The Dusseldorf atlas. History and presence of the provincial capital in maps]. Emons (pp. 74-77).

- Gorman-Murray, A. (2012). Queer politics at home: Gay men’s management of the public/private boundary. New Zealand Geographer, 68(2), 111–120.

- Gorman-Murray, A., & Nash, C. J. (2016). LGBT communities, identities and the politics of mobility: Moving from visibility to recognition in contemporary urban landscapes. In B. Gavin & B. Kath (Eds.), The Routledge research companion to geographies of sex and sexualities (pp. 247-253). Routledge.

- Gunkel, K. (2018). Der Instagram-Effekt: Wie ikonische Kommunikation in den social media unsere visuelle Kultur prägt [The instagram-effect: How iconic communication in social media influences our visual culture]. Transcript.

- Gusowski, A., & Mordel, P. (2012). Club der polnischen versager [Club of polish losers]. Rowohlt Verlag.

- Harper, D. (2004). Photography as social science data. In U. Flick, E. Von Kardoff, & I. Steinke (Eds.), A companion to qualitative research (pp. 231–236). Sage.

- Heymann, N. (2014). Visual Kei: Körper und Geschlecht in einer translokalen Subkultur [Visual Kei: Body and gender in a translocal subculture]. Transcript.

- Holm, G. (2014). Photography as a research method. In P. Leavy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Oxford University Press.

- Ikeuchi, S. (2017). From ethnic religion to generative selves: Pentocostalism among Nikkei Brazilian migrants in Japan. Contemporary Japan, 29 (2), 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/18692729.2017.1351046

- Interviews

- Jäger, K. (2017). Japans Hauptstadt in Deutschland –: Wie Düsseldorf sich zum wichtigsten Ziel japanischer Investitionen machte [Japan’s capital in Germany: How Dusseldorf became the most important target for Japanese investments]. Standort, 41(1), 20–26.10.1007/s00548-017-0462-4

- Jurkowski, J. M., & Paul-Ward, A. (2007). Photovoice as participatory action research tool for engaging people with intellectual disabilities in research and programme development. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 46(1), 1–11. 10.1352/0047-6765

- Kojima, D. (2014). Migrant intimacies: Mobilities-in-difference and basue tactics in queer Asian diasporas. Anthropologica, 56(1), 33–44. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24469639

- Kottmann, N. (2017). Forschungswerkstatt ‚Japanische Küche in Düsseldorf [Research workshop on Japanese cuisine in Düssseldorf]. Modernes Japan [Modern Japan]. Retrieved September 15,2018, from http://www.phil-fak.uniduesseldorf.de/oasien/blog/?p=16649

- Kuntjara, A. P. (2009). A method of documentary photography and its application in a student project of acculturation in Bali. Jurnal Desain Komunikasi Visual Nirmana, 11(2), 79–85.

- Lodge, C. (2009). About face: Visual research involving children. Education, 37(4), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270903099926

- Lovatt, M. (2018). Becoming at home in residential care for older people: A material culture perspective. Sociology of Health & Illness, 40(2), 366–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12568

- Lunsing, W. (2005). LGBT rights in Japan peace review. A Journal of Social Justice, 17(2-3), 43–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631370500332858

- McCrostie, J. (2017, August 9). More Japanese may study abroad, but not for long. Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2017/08/09/issues/japanese-may-studying-abroad-not-long/#.XYsMdn_gpmM

- McLelland, M. (2004). From the stage to the clinic: Changing transgender identities in post-war Japan. Japan Forum, 16(1), 1–20. DOI: 10.1080/0955580032000189302

- McLelland, M. (2009). The role of the ‘tōjisha’ in current debates about sexual minority rights in Japan. Japanese Studies, 29(2), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371390903026933

- McLelland, M. (2018). From queer studies on Asia to Asian queer studies. Sexualities, 21(8), 1271–1275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460718770448

- McLelland, M., & Suganuma, K. (2009). Sexual minorities and human rights in Japan: An historical perspective. The International Journal of Human Rights, 13(2–3), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642980902758176.

- Mcleod, K. (2013). Visual kei: Hybridity and gender in Japanese popular culture. Young, 21(4), 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308813506145

- Miller, D. (1998). Introduction. In D. Miller (Ed.), Consumption. Critical concepts in the social sciences I (pp. 1–14). Routledge

- Miller, D. (1998). Why some things matter. In D. Miller (Ed.), Material cultures. Why some things matter (pp. 3–21). The University of Chicago Press.

- Montag, B. (2001). Angepasster Raum. Japanische Migranten in Düsseldorf [Adjusted space. Japanese migrants in Dusseldorf]. Praxis Geographie, 31(2), 9–13.

- Morris, M. (2012). Concise dictionary of social and cultural anthropology. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Murray, D. C. (2015). Notes to self: The visual culture of selfies in the age of social media. Consumption Markets & Culture, 18(6), 490–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2015.1052967

- Nash, C. J., & Gorman-Murray, A. (2014). LGBT neighbourhoods and ‘New Mobilities’: Towards understanding transformations in sexual and gendered urban landscapes. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(3), 756–772. DOI: 10.1111/1468-2427.12104

- Noble, G. (2009). Countless acts of recognition: Young men, ethnicity and the messiness of identities in everyday life. Social & Cultural Geography, 10(8), 875–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360903305767

- Nobu. 14.5.2016, at his apartment, Berlin.

- Oh, S. (2012). Photofriend: Creating visual ethnography with refugee children. Area, 44(3), 282–288. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23251549

- Ohara, L., & Higgins, K. (2017). Participant photography as a research tool: Ethical issues and practical implementation. Sociological Methods & Research 48(2), 1–31.https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124117701480

- Pictures taken by Natalia Morokhova.

- Piotr. 14.5.2016, Club der polnischen Versager, Berlin.

- Plummer, K. (1995). Telling sexual stories: Power, change and social worlds. Routledge.

- Radley, A., Hodgetts, D., & Cullen, A. (2005). Visualising homelessness: A study in photography and estrangement. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 15(4), 15, 273–295.

- Rausling, S. (1998). Signs of the new nation: Gift exchange, consumption and aid on a former collective farm in north-west Estonia. In D. Miller (Ed.), Material cultures. Why some things matter (pp. 189–214). The University of Chicago Press.

- Reiher, C. (2016). Forschungswerkstatt Japanologie. Praxisnahe Vermittlungsozialwissenschaftlicher Methoden in der Japanforschung [Research workshop on Japanese foodscapes in Berlin. A practical approach to social science methods for research on Japan]. Retrieved February 24, 2019, from https://userblogs.fu-berlin.de/forschungswerkstatt-japan/

- Reiher, C. (2018). Japanese foodscapes in Berlin: Teaching research methods through food. ASIEN – the German Journal of Contemporary Asian Studies, 149, 111–124.

- Rundfunk Berlin Brandenburg [RBB]. (2018). Neue Einwohnerzahlen. Mehr als 3,7 Millionen Menschen leben in Berlin [New resident numbers. More than 3.7 million people live in Berlin]. https://www.rbb24.de/panorama/beitrag/2018/10/berlin-einwohner-bevoelkerung-zuwachs.html

- Sarvas, R., & Frohlich, D. M. (2011). From snapshots to social media: The changing picture of domestic photography. Springer.

- Schröder, P., & Stephan-Emmrich, M. (2014). The institutionalization of mobility: Well-being and social hierarchies in central Asian translocal livelihoods. Mobilities, 11(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2014.984939

- Schwartz, D. (1989). Visual ethnography: Using photography in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology, 12(2), 119–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988995

- Song, J., Han, K., Lee, D., & Kim, S. (2018). Is a picture really worth a thousand words?”: A case study on classifying user attributes on Instagram. PLoS One, 13(10), e0204938. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204938

- Statistical Office Berlin-Brandenburg. (2018). Statistischer Bericht. Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner im land Berlin am 30. Juni 2018 [Statistical report. Residents in Berlin at the time of June 30, 2018]. https://www.statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de/publikationen/stat_berichte/2018/SB_A01-05-00_2018h01_BE.pdf

- Tagsold, C. (2011). Establishing the ideal foreigner representations of Japanese community in Dusseldorf, Germany. Encounters, 3(1), 143–168.

- Takushi. 24.5.2016, at his apartment, Berlin.

- Tamaki, T. (2019). Repackaging national identity: Cool Japan and the resilience of Japanese identity narratives. Asian Journal of Political Science, 27(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185377.2019.1594323

- Tifentale, A. (2015). Making sense of the selfie: Digital image-making and image-sharing in social media. Scriptus Manet, 1(1), 47–59. ISSN: 2256-0564.

- Tkotzyk, V. (2017, December 2). The integration of Japanese migrants into German society: The example of Dusseldorf, Japan association for migration policy studies. Nanzan University. Abstract. http://iminseisaku.org/top/conference/conf2017.html#conf2017annual

- Utekhin, I. (2017). Small data first: Pictures from Instagram as an ethnographic source. Russian Journal of Communication, 9(2), 185–200. 10.1080/19409419.2017.1327328

- Valaskivi, K. (2013). A brand new future? Cool Japan and the social imaginary of the branded nation. Japan Forum, 25(4), 485–504. DOI: 10.1080/09555803.2012.756538

- Vium, C. (2017). Fixating a fluid field: Photography as anthropology in migration research. In E. Elliot, R. Norum, & N. B. Salazar (Eds.), Methodologies of mobility. Ethnography and experiment (pp. 172–194). Berghahn Books.

- Waitt, G., & Gorman-Murray, A. (2011). Journeys and returns: Home, life narratives and remapping sexuality in a regional city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(6), 1239–1255.DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01006.x

- Weston, K. (1995). Get thee to a big city: Sexual imaginary and the great gay migration. Gay and Lesbian Quarterly. A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 2(3), 253–277.

- Wilson, N., Dasho, S., Martin, A. C., Wallerstein, N., Wang, C. C., & Minkler, M. (2007). Engaging young adolescents in social action through photovoice: The youth employment strategies (YES!) project. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 37(2), 241–261. DOI: 10.1177/0272431606294834

- Winton, A. (2016). Using photography as a creative, collaborative research tool. The Qualitative Report, 21(2), 428–449.Retrieved from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol21/iss2/15