ABSTRACT

Japan today faces several demographic-related challenges: population decline, an aging population, and a declining workforce. One of the proposed solutions to these challenges is to allow more foreign workers into Japan. However, this move is being organized without the implementation of blanket immigration and integration policies. Despite ongoing resistance in political and societal fields toward the creation of an explicit immigration policy, there is currently a prototype of an integration policy introduced by the Japanese government in 2006 – tabunka kyōsei (multicultural community building) – aimed at the social integration of foreign residents into Japanese communities. This article focuses on issues related to immigration and integration policies in Japan and how a lack of both challenges integration initiatives on the local level through centers for international exchange (kokusai kōryū sentā). We examine the issues behind immigration and integration in Japan and the role of these centers. Our analysis includes a review of immigration and integration programs in Japan to identify the gap between those and actual needs, with a focus on the role of the centers for international exchange. We then analyze the centers themselves, discussing how they apply government policy and resources; the current state of the centers; and foreign residents’ participation in the activities of such centers. In sum, we review the current state of foreigners’ integration in Japan and analyze the role the centers for international exchange play in incorporating them into the society and economy.

On 8 December 2018, the Japanese Diet gave final approval to a revision of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act that will loosen restrictions on labor migration into Japan by creating two new visa categories for foreign workers. The bill is designed to help alleviate the labor shortage in Japan caused by its aging society and low birth rate, which the business community has demanded action on for years, but still the legislation has opponents within the Diet and the public (Sieg & Miyazaki, Citation2018).

One reason for apprehension is the question of how to accommodate and integrate a possible influx of tens of thousands of foreigners due to the law. After conducting a wide-ranging survey of 334 municipalities across Japan in November-December 2018, Nikkei Research provides evidence that Japanese municipalities are not prepared for the influx. Roughly 60% of municipalities lack “comprehensive support offices to help foreign residents adjust to life in Japan” (Yamamoto, Citation2019).

Twelve years earlier, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) requested in 2006 that municipalities set up special sections to accommodate the rising number of foreign residents. Many municipalities turned to their pre-existing centers/associations for international exchange (kokusai kōryū sentā/kyōkai),Footnote1 whose official purpose up until that point had largely been devoted to internationalization programs. These comprise most of the government efforts at the municipal (and prefectural) level to accommodate foreign residents into Japanese society, and are the focus of our study.

Immigration and integration policies are complex topics that have been extensively discussed by a number of scholars through various perspectives. In the review of major Japanese sociological studies focusing on different groups of foreigners in Japan, Komai (Citation2015) concludes that, even in the absence of a comprehensive national migrant integration policy, there still exist immigration regimes. His general criticism towards this area of research focuses on an imbalance in the groups studied, with large ethnic groups and local stakeholders overlooked, as well as an overemphasis on the general state of those groups, rather than a focus on the necessary steps to improve their lives. We observe similar trends in other scholarship that addresses migrants and their activities in multicultural spaces in Kawamura (Citation2012) and Satake and Kim (Citation2017). However, some edited volumes (Kagami, Citation2017; Menju, Citation2017) take an action research approach. The authors in Kagami (Citation2017) explore issues faced by different groups of minorities and provide possible ways of addressing those, while the authors in Menju (Citation2017) focus on local governments and their role in the enhancement of so-called “multicultural power” from the grassroots perspective.

Since around the 2000s, spurred by declining birthrates, labor shortages and an increasing number of foreign residents settling in Japan, there has been a growth in studies focusing on the political and social aspects that eventually influence the migration outlook. In terms of political environment, some authors point to the political deadlock and fragmentation surrounding migration policy (Chiavacci, Citation2014; Takaya, Citation2018; Vogt, Citation2014). Vogt (Citation2014, p. 62) identifies that “the immigration control discourse frames the issue of migration to Japan as one of national security, whereas the integration efforts discourse frames it as one of economic and human security”, thus leading to a deadlock in Japan’s migration debate. Further analyzing the discourse of foreign workers as a perceived threat to public security, Chiavacci (Chiavacci, Citation2014, p. 130) points to the moral panic around the possibility of “a complete breakdown of public order” as a result of a more open immigration policy.

When it comes to the discussion of tabunka kyōsei (multicultural community building) and its meaning, Bradley (Citation2014) reviews studies of the topic since 2000. He concludes that “there are both positive and negative evaluations of the sustained commitment to multiculturalism by the national government and down to local levels. […] [E]ducation, political participation, and anti-discrimination legislation – show the most dynamism at the local level” (Bradley, Citation2014, p. 36). Kibe (Citation2014) compares tabunka kyōsei to multiculturalism and analyzes it from the philosophical point of view. He concludes that an unclear vision of tabunka kyōsei (as it was in the case of multiculturalism as well) and weak positioning of the MIC are the sources of its inability to solve the structural inequalities of foreign residents, especially in the low-skilled labor market. Furthermore, Liu-Farrer (Liu-Farrer, Citation2020, p. 6) points to the idea that “instead of creating scheme after scheme to import temporary labor, Japan needs to ponder how to create a social environment where immigrants can more easily fit in and feel at home.” When addressing integration at the local level in a survey of municipal governments regarding policies and attitudes towards foreign residents in 2006, Abe’s (Citation2007) respondents commented on the difficulties of complete multicultural co-existence due to strong expectations of assimilation in Japanese society and simultaneous growth of ethnic networks. Additionally, there were different types of foreign residents depending on the municipality, which led to a varied set of tasks and challenges in different areas. Building from these studies, we agree with Kibe and Liu-Farrer on the need to further analyze the role of tabunka kyōsei in the integration of foreign residents, and we aim to further discuss the challenges of local governments introduced by Abe (Citation2007) by questioning the process of implementation of tabunka kyōsei.

This article analyzes the role of centers for international exchange as resources for migrant integration. In the next section, our analysis includes a review of immigration and integration initiatives in Japan to identify the gap between those initiatives and actual needs with a focus on the centers. The empirical part of the study focuses on centers in various areas of Japan and discusses their current state to see how they apply government policy and resources. We visited 11 centers for this purpose. By analyzing the role that the centers play in incorporating foreign residents into society and the economy, we aim to show how differently the centers’ activities are organized, which leads to varying levels of preparedness at the municipal level to accept large numbers of foreign workers. We conclude with a discussion of current programs’ achievements and points that need further attention and consideration.

“Not a country of immigration”?

There are several questions and underlying issues that should be addressed before analyzing the implementation of immigration and integration initiatives in Japan.

Is Japan a country of immigration? Kondo (Citation2015) introduces six chronological periods identifying the development of migration law in Japan: 1) No immigration due to national seclusion (1639–1853); 2) opening of the country to large-scale emigration and colonial immigration (1853–1945); 3) strictly controlled migration under the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (1945–1951); 4) the 1952 Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (ICRRA), known as the “52 Regime” (1952–1981), which established restrictive immigration stipulations characterized by discriminative and assimilationist practices; 5) the “82 Regime” of the ICRRA (1982–1990), which saw some improvements in foreign citizens’ rights and acceptance of a number of refugees; and 6) the amended ICRRA, the “90 Regime,” in enforcement since 1990. The newly passed revision of ICRRA may form a new seventh period.

The “90 Regime” was characterized by relatively strict control, but it had three loopholes to bring low-skilled workers to the country. These allowed ethnic Japanese from Latin America (nikkei) to work without restrictions, implementation of the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) in 1993, and acceptance of irregular labor migrants (including entertainers) and foreign students with limited work permits.

The current initiative to attract more foreign workers to Japan follows the tradition of the “90 Regime” in its attempts to create various immigration loopholes to attract a low-skilled labor force. Thus, from the policy perspective, we see ongoing reliance on legal loopholes to solve labor shortage issues. Takaya (Citation2018, p. 59) points out that issues surrounding “migrants” are mostly not considered political tasks by the Japanese government; she explains the absence of immigration policy as a “liberal trilemma.” This liberal trilemma involves initial low interest towards foreign workers from big businesses; Japan’s ethnocultural nationalism, public concerns about security due to the influx of migrants and a passive attitude from the Japanese Trade Union Confederation on the political side; and lastly, a lack of protection of foreign workers’ rights from an international human rights perspective. Chiavacci (Citation2014) also points to the non-committal attitudes of Nikkeiren and Keidanren (Japan Business Federation, currently Nippon Keidanren) in the late 1980s. Furthermore, Mabuchi (Citation2018) points to the government’s reluctance to use the word “migrant.” Thus, the current absence of an immigration policy can be explained by loopholes in the 1990s ICRRA, pointing to the idea that Japan is not a country of immigration. This leads to a lack of urgency in accommodating and integrating “migrants” among politicians, since foreigners are considered a temporary workforce not expected to settle in the country.

Where does Japan stand in terms of integration policy? In his study, Burgess (Citation2007) raises the question of whether Japan is homogeneous or multicultural, and analyzes this question by utilizing three components: (academic) discourse, policy and people. He provides evidence that ideologies, such as nihonjinron and multicultural Japan, have been socially constructed and do not necessarily reflect the reality; that Japan’s policies aimed at various types of its minorities and foreign population are not sufficient; and finally, that the statistics of foreign citizens living in the country “suggest that, at the present time, Japan is a relatively homogenous country in terms of migration and ethnicity” (Burgess, Citation2007, p. 10). However, Japan has implemented the Plan for the Promotion of Tabunka Kyōsei (tabunka kyōsei suishin puran, hereafter Tabunka Kyōsei Plan), which is a prototype of an integration policy that is aimed not only at its long-existing ethnic and cultural minorities, but also foreign residents and their settlement in Japan. Thus, we can see a migrant integration initiative without immigration policy being implemented.

How did Japan manage to deal with its increased foreign population without having a blanket integration policy? The answer is in Tegtmeyer Pak’s (Citation2000) study, which demonstrates how local governments autonomously create programs aiming to incorporate long-existing minorities and foreign residents. There are three main forces that contributed to the creation of local incorporation policies: 1) the close proximity of foreign residents to local officials, who encounter them on a daily basis compared to the more depersonalized relations between foreigners and the national government; 2) local governments being more responsive to various challenges compared to the national government and becoming legitimate policy innovators; and, 3) “the redefinition of local internationalization to include incorporation programs allows the bureaucrats-in-charge to expand the scope and importance of their programs” and provide outreach to foreign residents (Tegtmeyer Pak, Citation2000, pp. 247–48). Although in some instances, the push for incorporation programs have come from foreigners and long-existing minorities, in general it was coming from bureaucrats driven by the worries of social and cultural stability in the area. The autonomous activities of local governments and their further push for the national government to react eventually led to the implementation of the Tabunka Kyōsei Plan.

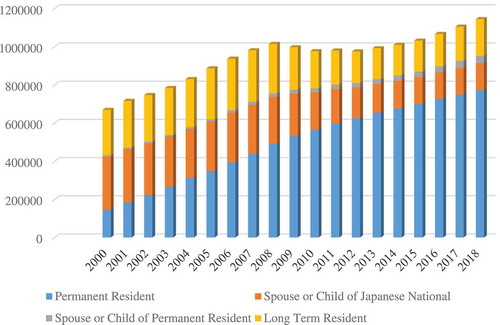

This leads to the question of who the foreign residents are that are the target of the Tabunka Kyōsei Plan. There are various debates on how to calculate the number of “migrants” and where Japan stands among developed nations (see Burgess, Citation2007). However, the number of foreign residents () who acquire permanent residence, their spouses and dependents, long-term residents, and spouses of Japanese nationals – groups that are most likely to settle in Japan long-term – has been growing steadily. The number stood at 1,143,961 in 2018 compared to 669,253 in 2000 (Ministry of Justice, Citation2005, Citation2019). If we also include special permanent residents (zainichi Koreans and Taiwanese), these numbers stood at 1,465,377 in 2018 compared to 1,181,522 in the year 2000 (). Though there is no major growth in numbers, the distribution of the residence statuses and countries of origin provides a different picture (see also ). Thus, there are fewer zainichi, due to their continuous naturalization, but more residents with a variety of backgrounds. We agree with Burgess’s critique that these numbers are not large enough to call Japan a “multicultural” state, but based on , we claim that there is more diversity among Japan’s foreign population and that this population needs more basic support in their daily life.

Table 1. Registered foreign residents in Japan by Status of Residence.

Table 2. Registered foreign residents in Japan by Country of Origin.

Figure 1. Number of registered foreign residents (not including Special Permanent Residents). Source: Ministry of Justice (Citation2005, Citation2011, Citation2013, Citation2016b, Citation2018b, Citation2019).

From a broader definition of foreign residents that includes all residence types, according to the Ministry of Justice (Citation2019) there were 2,731,093 foreign nationals residing in Japan in 2019 (). With regard to integration of these foreigners, however, “Japan has no official integration programs at the national level” (Chung, Citation2010, p. 35). To this day, migrant integration has been based on ad hoc measures, with most situations depending on the discretion and initiatives of local governments and communities.

Though there is no one unified way to measure the integration of migrants, there is a recently created measurement of integration policies, the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX). The index consists of 167 policy indicators, and “identifies and measures integration outcomes, integration policies, and other contextual factors that can impact policy effectiveness; describes the real and potential beneficiaries of policies; and collects and analyses high-quality evaluations of integration policy effects” (MIPEX, Citation2015b). In 2014, Japan’s MIPEX was 44 out of 100, with foreign residents enjoying relatively favorable access to the labor market and the health system, but facing less favorable conditions for permanent residence, paths to citizenship, political participation, and targeted support for children’s education (MIPEX, Citation2015a).

This is the current context in which immigration and integration programs have been implemented. Due to different political, economic and social pressure it was possible for the national government to avoid the implementation of immigration policy so far. Furthermore, the current prototype of integration policy was implemented due to the push from local governments to integrate their foreign residents.

The development of integration initiatives

Integration is a complex topic, one that can be fraught with controversy. Integration can often be taken to mean the assimilation of migrants into the national culture of their new society. We support the idea that the process of integration is a two-way social interaction between the majority community and immigrants, where the site of institutions (employers, civil society and the government) of the established society must take the lead (Modood, Citation2007).

The central government’s initial attempt at internationalization in response to globalization came in the 1980s. An early prototype for immigrant integration is the “international exchange (kokusai kōryū) program, implemented in 1987 and aiming at foreigners serving ‘as a medium for internationalizing Japanese citizens’” (Kashiwazaki, Citation2011, p. 47). This so-called “local-level internationalization (chiikino kokusaika)” program aimed to encourage international exchange activities at the prefectural and municipal levels such as sister-city exchanges and intercultural understanding for local residents (Ministry of Home Affairs, Citation1987).

In the beginning of the 1990s, with a rising number of foreign residents, the need to tackle the social and cultural issues they face became obvious. This led to the establishment of the Council of Municipalities with Large Migrant Populations initiated by Hamamatsu City, and the joint statement of the “Hamamatsu Declaration” of 2001. The “Hamamatsu Declaration” was joined by 29 Japanese cities as of 2013, and “continues to present suggestions to the national and prefectural governments as well as organizations concerned, relating to the many issues experienced by foreign residents, which arise from laws and systems” (Hamamatsu City, Citation2013, p. 13).

It took five years for the government to respond, and then in March 2006 it established the “Study Group of Promotion of Multicultural Coexistence” under the MIC. Further, based on the Group’s report, municipalities were requested “to create guidelines and plans related to the promotion of intercultural integration” (Hamamatsu City, Citation2013, p.13), which became a base for the Tabunka Kyōsei Plan. Based on this Plan, “international exchange” programs were expanded to provide information and consultation services to foreign residents, and were conducted by centers for international exchange, which “eventually came to play a major role in implementing integration programs” (Kashiwazaki, Citation2011, p. 47). Later, starting from 2009 a set of measures were taken by the government that led to the creation of a “Basic Guideline of Measures for Japanese-Descended Residents” and an “Action Plan” in 2010, along with a plan for “Aiming for the Realization of a Society in which Japanese and Non-Japanese can Live in Comfort (Intermediate Arrangement)” in 2012.

The current prototype for integration policy in Japan, the Tabunka Kyōsei Plan, has public and social areas of integration. On the public level of integration, Japan’s foreign residents have similar welfare rights as Japanese residents, including health insurance, childcare allowances, admission to public housing, and worker pensions. Additionally, a workforce-oriented plan drafted in 2008 based on “human resource development” accepted not only high-skilled workers, but also young workers with specific skills and qualifications with the prospect of future naturalization (Kibe, Citation2011). At the social level of integration, which is culturally oriented, the aims are to “remove cultural barriers and promote intercultural understanding” (Kibe, Citation2011, pp. 60–61), as formulated by the MIC in 2006. However, these are mostly frameworks for action and there is no clear vision in these two initiatives or particular programs on how to achieve their goals. It is also not clear what categories of foreign residents are their main target. Finally, there is no clear plan of implementation of these two initiatives and how they will complement each other.

The Tabunka Kyōsei paradigm and its implementation

The 2006 MIC report states that in addition to the two main pillars of “local-level internationalization” – “international exchange” and “international cooperation (kokusai kyōryoku)” – that were implemented in the second half of the 1980s, local governments need to promote tabunka kyōsei (MIC, 2006, p. 2). There are three main points in the government’s Tabunka Kyōsei Plan: 1) Support of communication (komyūnikēshon shien) – multilingual or “easy Japanese” support and support of adults’ Japanese language studies; 2) Support of daily life (seikatsu shien) – housing, education, working conditions, healthcare/insurance/welfare, and disaster prevention; and 3) Tabunka kyōsei at the local level (tabunka kyōseino chiiki zukuri) – awareness of tabunka kyōsei in the local community, supporting independent living for foreign residents and participation in the social planning and organization of the promotion of the tabunka kyōsei policy. Finally, there is an additional concept that was formulated as a necessary point in the promotion of tabunka kyōsei by local governments (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication, Citation2006): 4) Maintenance of the organization of tabunka kyōsei policy promotion (tabunka kyōsei shisakuno suishin taiseino seibi). However, in the MIC 2017 report the fourth concept was changed to the “contribution to regional revitalization and globalization” (chiiki kasseika ya gurōbarukaheno kōken) (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication, Citation2017).

This plan is implemented by local governments, which act as intermediaries between the central government and residents for social welfare services and needs (Shipper, Citation2008, p. 129). One type of organization relied upon to support foreign residents are the centers for international exchange, which were originally created to promote internationalization, but have transitioned toward serving local foreign residents. In the last two decades these centers have proved to be useful for the integration programs because they offer crucial services for foreign residents to adapt to their life in Japan.

In sum, this review of government initiatives in the field of immigration and integration outlines the political, economic and social factors that influenced perceptions of Japan as a latecomer in the (labor) migration market. Despite the ongoing influx of various groups of foreigners into the country starting from the 1980s, the government still has not been able to implement a blanket migration policy, and has used more reactive tactics instead of proactive strategies to address labor shortages in the country. Furthermore, despite the continuous settlement of foreign residents, there were mostly attempts to internationalize Japanese citizens rather than integrate foreign residents. In the case of integration programs, these were primarily spearheaded by local governments’ and activists’ initiatives to tackle the issue of foreign residents’ settlement and rights. Thus, we can see not only the gap between immigration and integration initiatives in terms of their lack of coordination, but we also raise the question of who will be in charge of newly arriving foreign workers. What is expected of local governments and what can they do? To address these questions, we turn to the centers for international exchange.

Empirical research

In this section we focus on the functions, roles and challenges of the centers for international exchange. By discussing the current state of these organizations, we aim to evaluate and analyze the general preparedness of different regions to accept large numbers of foreign workers. We visited 11 centers to gather information in February and March 2017. We keep the identity of the centers anonymous.

Centers for international exchange

Centers for international exchange started appearing around Japan in the 1970s and 1980s. At first, these served to promote trade and tourism for their cities and prefectures with other countries. This role started to change at many centers in the 1990s and 2000s, as greater numbers of foreigners were settling across the country. Most of the centers that we visited started to turn to a foreign resident-oriented approach to help with their increasing numbers.

There are three basic types of centers for international exchange: municipal, prefectural, and non-profit.Footnote2 Municipal centers are the focus of our study. Center facilities differ greatly in terms of resources and sizes. For instance, one center located in a wealthy metropolitan district covered about half of a floor in a building connected to the main district office. The district has pricier real estate, but it is better funded. A rural center in the Chūbu area, on the other hand, had merely a small, old office available for its services. Space is plenty and real estate is inexpensive in this area, but the center was very poorly funded so it had to rent space for events and classes (with inadequate funds). Furthermore, it had only one paid staff member – all other staff were volunteers. All of the centers that we visited had their information pamphlets and newsletters translated into the languages used by their largest foreign communities. Many centers charged an inexpensive annual membership fee for regular users of services. The fees were typically around JPY1000-2000.

Services for foreign residents. Among the 11 centers we researched, we noted a number of services for foreign residents. First and foremost are Japanese language/conversation classes, the most heavily used services. Japanese classes occur 1–3 times a week and generally are very inexpensive or free. The level of the Japanese classes varies, with some centers offering only basic Japanese and others offering classes in advanced conversation and Japanese characters. This mostly depends on the volunteers available to teach the classes. Some rural centers may not have the resources (space, funding, volunteers) to offer Japanese classes and so instead advertised where those interested can find free or inexpensive lessons locally (for more on this, see Uchida, Citation2018).

Another type of service is the provision of consultation or information windows/hotlines (sōdan madoguchi). These are the first stop for many foreigners (and Japanese citizens) who have questions about the center and its services. For example, at one large metropolitan center, in 2014 there were 3,254 instances of contact with the information service – foreigners comprised 57% (1,862 peopleFootnote3 ) and Japanese citizens the remaining 43% (1,392). Most foreigners asked about the center’s services for legal and immigration advice (229 people), information about the healthcare system (295), and general information about living in Japan (522). By comparison, at a rural center in the Kansai region that has a large permanent resident community, visits to the information window grew slowly from 152 visits in 1993 to a peak of 1,576 visits in 2008.Footnote4 That number then took a precipitous drop down to 860 visits by 2011, but was slowly growing again by 2017. The users largely asked about the legal and healthcare advice services, with work advice consultations increasing over the years.

The centers’ free legal advice services are frequently used as well. At some centers, legal advice is proffered by legal professionals volunteering their services on a weekly basis. The legal advice is offered with a disclaimer that the legal advisor is offering their best opinion and that neither the advisor nor the center is liable for what the advice seeker does with it. Many centers also offer “legal counseling,” which should not be confused with legal advice from a legal professional, but rather entails a staff helping foreign residents with documents and answering basic legal questions that are common knowledge or can be found on the internet. Through legal counseling, centers provide help in filling out a variety of bureaucratic documents in Japanese for use in different areas of life (healthcare, city registration and other legal matters). Many centers additionally provide translation and interpretation help, support and consultations to those married to Japanese nationals, and information on shelters for the victims of domestic violence.

On the cultural side, many centers hold classes to teach about aspects of Japanese culture, such as ikebana or calligraphy classes. Many centers help with local festivals as co-organizers and by organizing get-togethers for foreign residents to enjoy the festivities with local Japanese. In this sense, centers become alternative community centers (kōminkan), bringing foreign residents closer to their Japanese neighbors. At many centers, provision of some or most of these services relies on volunteers from the local Japanese community. This is helpful for integration as well, as volunteers may be more likely to strike up and continue friendships with foreign residents than paid employees.

On top of the usual services, many larger, well-funded centers provide a combination of activities and services each day of the week. As an example, one center located in a Kantō metropolitan district had the schedule seen in when we visited in March 2017. Most of the activities lasted from 90 minutes to two hours.

Activities aimed at Japanese citizens. There are activities that are geared toward bringing Japanese citizens into centers. At the large metropolitan area center which had 1,392 Japanese citizens contacting their information center, the citizens primarily wanted information about presentations and the general use of the facilities (the international cafe, the library, etc.). International cafe/kitchen classes serve to bring foreign residents and local Japanese together. They either employ or invite foreign residents to voluntarily serve as the cook of the week to introduce their country’s cuisine to local residents. Classes in foreign languages, often taught by foreign resident volunteers, also help to bring in Japanese citizens. A strong benefit of this outreach to Japanese locals, on top of their help with foreigner integration, is that this provides revenue by way of fees charged to citizens, as well as a type of investment of social capital by locals in the centers. This supports the perspective of the centers as alternative community centers. Both of these benefits can help make the centers more sustainable against the looming threat of government cutbacks.

Patterns among centers for international exchange

To gain better knowledge about the centers’ activities, in February and March 2017 we visited and conducted interviews with center staff at 11 centers situated in areas accepting a (relatively) high proportion of foreign residents in Tokyo, Osaka, Kanagawa, Aichi, Niigata, Nagano, Ishikawa, and Shiga prefectures. We interviewed 13 staff members, one former foreign staff, four volunteers and four foreign residents who were visiting the centers. The interview questions included personal background of each participant, how they came to work for the organization, what roles they had, and how their work had changed through the years. We also asked general questions about the organization of the center, how it functioned, its relations and connections with local government, the number of Japanese and foreign national staff, daily issues the organization faced, the organization’s attempts to attract foreign and local residents, programs that involved the participation of local and foreign residents that enhance their communication, and programs aimed at empowering foreign residents.

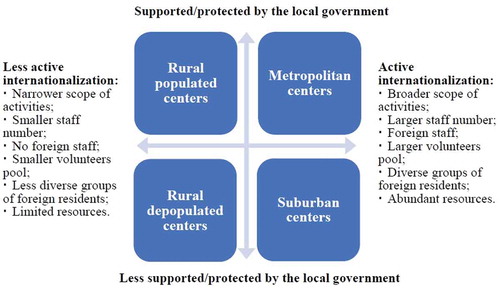

We further develop Tegtmeyer Pak’s (Citation2000) proposed scales of broader/narrower scope of incorporation programs and the intensity (passive/active) of internationalization, which she created to evaluate the availability of foreign language publications, counseling, Japanese language classes, contact with local administration/exchange activities within the community, and training for Japanese residents or officials, etc. We identified four patterns in that the centers more or less fit into from the interviews and allocated them based on the level of support/protection they receive from the local governments, usually by employing former or current civil servants (the y axis), and to what extent they are active in their internationalization programs (the x axis). We considered centers’ number of activities; the certainty of the budget at each center (judged to be protected or not); presence of (former) civil servants (supported vs. less supported); access to resources; number of staff members (Japanese nationals, foreign residents, second generation foreign residents, mixed-heritage Japanese citizens, and volunteers); as well as the diversity of foreign residents using the center’s services.

Our four center patterns correspond with the four regional models of tabunka kyōsei introduced by Tamura (Citation2012), the Representative Director of the Institute for Human Diversity, Japan (). In his model, he differentiates between urban and rural areas, as well as concentrated versus scattered populated areas, and proposes characteristics of the foreign residents and respective necessary policies.

Table 3. Four regional models of tabunka kyōsei.

Metropolitan Centers: A center fitting this pattern is located in an area with a large number of foreign residents (such as the Tokyo or Osaka areas). The center has a strong connection with local government, a large number of visitors (local Japanese and foreign residents), and foreign residents have diverse visa statuses and purposes for staying in Japan. There is large number of staff, likely more than ten, with several foreign residents who are permanent or temporary staff. There are former or current civil servants among the Japanese staff in some cases. The center provides various types of activities, starting from Japanese language courses and counseling, to various cultural activities and foreign language courses.

For instance, center “A” was established in 1987 in an area that has a large population of foreign residents. It had 14 employees (including five foreign residents) and strong relations with its city hall. There have been budget cuts and the contracting of certain tasks, but it still enjoyed stable financial support. Foreign residents visiting the center had a variety of visa statuses and, therefore diverse needs in terms of their life in Japan (spouses of Japanese nationals, foreigners working in Japanese corporations, low-skilled laborers, university students, etc.). At the time of the fieldwork, the center had a project on “Linking with Foreigners” (gaikokujin renkei jigyō) that had 13–14 constant foreign resident membersFootnote5 including mixed-heritage Japanese nationals, and their activities were also monitored by the staff of the center.Footnote6 Various age groups of local Japanese residents participated in the activities. Starting from 2007, the center switched its focus to integration issues of foreign residents; however, later there had been a change in focus to temporary visitors. The effect that this had on the older foreign residents’ services is currently unknown. There were problems with reaching foreign residents and local residents in the area (challenges which all centers stated they had). There was no good way of promoting or advertising the existence of the center and its services given their limited budget.

Suburban Centers: Centers following this pattern are mostly situated in suburban residential areas, with a smaller local population and a smaller number of foreign residents. The center is usually situated away from the city hall. Most of the users are long-term foreign residents in the area, who have long-lasting connection with the centers. However, there is less support from the local government, constant fear of further budget cuts and anxiety related to future support. There are no former or current civil servants among the staff, so it is more difficult for these places to create networks between the centers and local governments. Similar to the Metropolitan centers, the Suburban center provides various types of activities, starting from Japanese language courses and support (legal issues, domestic issues, proceedings, etc.), to various cultural activities and foreign language courses.

As an example, center “B” was established in 1992 and had 15 employees, of which seven were foreign residents, mixed-heritage Japanese or nikkei. There have been deep budget cuts, and some services were contracted out. All programs were initiated by Japanese volunteers with no foreign residents joining in the planning. As with the first pattern, there was difficulty in getting the word out about the center and its services. In this case, the center had difficulties in reaching younger generations of local Japanese residents and foreign residents (many centers with this pattern had an increasing number of contract foreign laborers and changing needs to meet).Footnote7 The center was situated in a building separated from the local city hall, therefore there was no immediate link between the two, even though most of the foreign residents were provided with brochures about the center’s services by the city hall staff.

Rural Populated Area Centers: The third pattern is completely different from the previous two. Centers falling into this pattern are mostly located in remote areas with specific types of foreign residents. Therefore, the types of services are more specified as well: centers cater to permanent foreign residents married to Japanese nationals, or to temporary foreign workers (staying up to three years). They have stronger bonds with local governments, with former/current civil servants on the staff. These places are run by a smaller number of staff, with maybe one who is a foreign resident, however there are stronger bonds between permanent foreign residents and the staff of the centers, due to the small size of the local community. The main activities are Japanese language courses and some cultural programs.

For example, several centers in Aichi, Nagano and Ishikawa prefectures mostly catered to low-paid foreign workers in the local factories.Footnote8 Most of the time these workers did not plan to stay or could not stay in Japan permanently and the only services they used were Japanese language support and occasional cultural activities. In centers in Nagano and Niigata prefectures, users were mostly spouses of Japanese nationals.Footnote9 Again, their main purposes in using the centers were Japanese language support, cultural activities, child support and help with daily (health, education, marital) issues. Centers catering to Japanese nationals’ spouses claimed a higher level of social integration, due to the close proximity of foreign residents and their Japanese families; in addition, since these centers were situated in the countryside, there was a higher chance of a feeling of belonging with the local community. The staff in the centers consisted mostly of Japanese nationals interested in international exchange. Sometimes staff from the JET program were involved, however they did not deal with local foreign residents, but rather with local Japanese citizens.

Rural Depopulated Area Centers: The fourth pattern resembles pattern three, however there are some differences. Centers in this pattern are situated in the countryside, where there is a small number of Japanese and foreign residents, and less developed infrastructure (fewer options for public transportation and shopping and entertainment). There are also specific types of foreign residents: mostly they are temporary (staying up to three years) foreign workers,Footnote10 and permanent foreign residents married to Japanese nationals are rare. There is a very weak connection between local government and this type of center. The centers are run by one or two staff members and/or volunteers. These centers own only their office areas and do not own classrooms, and therefore must rent classrooms used by various local government organizations. The main activities are Japanese language courses and occasional cultural programs. Foreign residents mostly work for local factories/plants and they cannot attend many cultural activities.

It is clear from our descriptions that there are still a lot of needs that different patterns of centers have depending on the models of tabunka kyōsei in the corresponding areas. Obviously, Metropolitan and Suburban centers are more equipped to help new foreign residents to adapt to social and cultural life in Japan due to the abundance of the activities and resources. However, the diversity of the residents and needs, as well as the influx of a large number of users to these centers might lead to excessive pressure on the staff, volunteers, and facilities. On the other hand, we assume that the Rural Populated and Rural Depopulated Areas’ centers will have the largest influx of foreign workers due to workforce demands in such areas, and these are obviously less prepared and less equipped for the increase in the number of users. In addition, a lack of the social and cultural programs as well as poorer resources due to weaker connections with local authorities might lead to the isolation of large groups of workers and their segregation from the local Japanese community. Thus, though all centers face similar challenges of budgetary constraints, it is clear that the Metropolitan, Suburban and Rural Populated/Depopulated centers vastly differ in their abilities to cope with these demographic changes. Generally, the resilience of a center will follow a trend of proportionality towards the number of people serviced. Centers that have a large population will more easily be able to pivot their services, both through access to more volunteers and through paying customers. Centers that service areas with significantly lower population densities have limited ability in dealing with funding issues, and it is these areas that could be under the greatest demand for the complex services needed for foreign workers who may be lured by the recent changes in visa categories.

Reflections on the patterns and voices from the centers

There were of course similarities between the four patterns. Most centers faced budget cuts and they all had trouble promoting their services and bringing in new users. It was difficult for such centers to attract business investment, since they could not predict the attendance of particular activities and guarantee revenues.

One of the biggest questions of our study was about the organization of the centers and their relationship with the local and national governments. Therefore, we asked our participants to describe their budget situations. Initially, most of the centers we studied were foundations with funds allocated for their activities. These were not enough, so local governments provided additional subsidies for their activities and events. However, as a result of the “Lehman Shock,” starting from 2008 local governments had to cut subsidies for many of their projects, including centers for international exchange.

In their interviews, Mr. Suzuki (Metropolitan center in Kantō) and Mr. Uchiyama (Suburban center in Kansai)Footnote11 mentioned the reform of the Public Interest Corporations System (kōeki hōjin seido kaikaku) and the New Public Interest Corporations System (shinkōeki hōjin seido) that was implemented in 2008 and led to many changes in the centers’ operations from 2013. As a result of this reform, many general incorporated associations (ippan zaidan hōjin), such as many of the centers we visited, had to apply to become public interest incorporated associations (kōeki shadan hōjin). At the time of the interviews, these centers were in charge of operation consignment of the local government-owned facilities, receiving trust money, which was basically work outsourced by the local governments. The operation fees were paid by local governments and the money received covered only personnel and utility costs. The rest of the funds came from centers’ basic funds investment profits, annual fees from centers’ visitors, and other activities. As public interest incorporated associations, centers’ tax payments were reduced, but in exchange they had to organize public events. Should they have profits, half of those should be spent on public events. Both the Kantō Metropolitan center and the Kansai Suburban center functioned based on 5-year plans, and the decisions regarding their future activities were in the hands of local city councils. While Mr. Suzuki mentioned that their local government was devoted to the Tabunka Kyōsei Promotion Vision (tabunka kyōsei suishin bijon), Mr. Uchiyama was less optimistic, pointing out “they can cut the budget of language classes for instance, and ask us just to operate the facilities. Therefore, our position is very weak.” As Mr. Uchiyama noted, even though there was a program to help foreign workers, there was no policy and no budget to implement the program. Therefore, it was up to local governments to decide how to implement integration/incorporation programs.

Moreover, several of the interview participants mentioned 2013 as a year when large changes started to occur due to budget cuts. In her interview, a former foreign national staff member, Ms. Jones, who moved from the JET program to a contract worker position in a Metropolitan center, reflected on the changes. Her main responsibilities were English language interpretation and other tasks that she performed together with other employees. Ms. Jones described the job as being “like a three-way service – between the civil servant, the foreign resident and me.” Part of the workload focused on Japanese citizens: “Another project would be helping [local Japanese residents] with English … to help them become more familiar with English and with the global situation.” In the interview, Ms. Jones reflected on general issues that most of the centers we visited faced. In relation to budget cuts after 2013, the center geared its new projects toward Japanese citizens:

When it was a project that invited foreign residents and Japanese residents together to meet each other, then that was a project I was proud to be a part of. You know, they could get acquainted together … Due to budget cuts, we had to become a bit more independent and [not as] public anymore … So they would get professionals to teach Japanese residents these things [like sake making, tea ceremonies], and they would then teach foreigners. That’s not a bad thing, but those projects for foreign residents had to be cut … So my co-workers had to focus on projects for Japanese residents. But that’s not what most of the foreign residents were coming in for. The foreign residents that were coming had real-life issues.

The budget cuts had the effect of forcing the center to focus less on services for foreign residents and more on those for local Japanese residents, since most of their activities were fee-based.

As was shown in , the centers with the bigger budget cuts were rural, they were relying more on Japanese elderly and housewife volunteers (for whom time was a big constraint), and they were in areas that were seeing increases in contract migrant labor which would have greater needs, particularly in Japanese language services. When talking about current issues, Mr. Yamada, the head of a Rural Depopulated center, pointed out that:

foreign residents constitute 4% of the whole city’s population. We see increasing needs for our services. We feel that we need more volunteers, and more improvements with teaching Japanese language courses. Currently we have four rooms for 120 students with about 40 volunteers. (Mr. Yamada)

Thus, there was a lot of pressure on centers to find volunteers from a limited pool of human resources in less populated areas, in addition to the difficulties in securing enough space for providing their services. Mr. Yamada’s center had to rent out classrooms in the city-owned facilities, since the only space they owned was a small room inside the city hall. Moreover, Mr. Uchiyama and Ms. Jones pointed out that there was not enough support for foreign resident public school children, who needed support with their Japanese language and other studies as well.

We also witnessed that many tabunka kyōsei activities focused on introducing Japanese culture, which might be useful for foreign residents in the initial stages of settling in Japan. However, in the long run, foreign residents face more complex daily issues, for which they need individual help and which introductory cultural activities cannot address.

Most of the services provided were not organized systematically but were based on ad hoc needs of foreign residents or the availability of particular persons, which meant that there was no constant organized support. Instead, it fluctuated depending on the flow of foreign and local visitors. This, on the other hand, gave centers more flexibility in organizing their short-term support plans.

Another issue is promotion of the services overall. Staff at all of the centers complained that a major challenge was promoting their services and even getting residents to know that the center existed. Budget cuts made the promotion of services more pressing yet harder to achieve. In addition, there was lack of feedback at the centers from foreign residents. On the other hand, those foreign residents with very serious problems in their life could receive consultations related to their questions, but not any particular support; most of the time it was suggested they go to local NGOs/NPOs dealing with their particular issue (see more on these debates in Asahi Shimbun, Citation2018). As a former staff in a Metropolitan center, Ms. Jones shared the various frustrations she had faced during the work. It was mostly the result of difficulties in meeting expectations of foreign residents due to language and cultural differences. Being responsible for giving consultations over the phone, Ms. Jones was getting from five to ten calls during the consultation hours. It was not only the large number of calls that she had to handle, but also the complaints from foreign residents regarding the interpretation quality, phone services in general, and lack of details during the consultations. Many of the people needed support in such areas as health care/insurance, tax payments, legal procedures, leases, and so forth. However, they could not get information by themselves, due to their inability to communicate with Japanese officials and various specialists in the respected fields. In addition, in many cases specialists were not quite aware of the difficulties foreigners faced in understanding professional jargon used in their field. Ms. Jones also pointed out that many legal consultations were provided based on the Japanese law and cultural features:

sometimes you can’t find the ideal answer, that’s why sometimes people were not satisfied. One example is with legal consultations. Very sensitive matters, they’re very frustrated … The lawyer would say it’s not all your spouse’s fault – you share some of the blame too. And then the foreign resident would be offended. And then I would tell them the lawyer’s not picking sides, not showing favoritism, just trying to explain the general situation in Japan.

Moreover, there are differences between staff in most of the organizations. On the one hand, those organizations that had former or current civil servants had a better position due to the ability of their staff members to navigate through the bureaucratic proceedings necessary to operate. However, most of these civil servants did not have much experience working with foreign residents and had less understanding of their needs, therefore they had to depend on the regular staff (if there were any) who were more familiar with daily issues.

Every person we met at the centers had unique stories. Some of them left other jobs to work in the area of internationalization, as happened with Mr. Suzuki, vice-president of a Metropolitan center in the Kantō area, or Mr. Katō, who used to work as a Japanese representative in an international aid organization and was the head of a Rural Populated center in Chūbu at the time. However, as Ms. Jones pointed out in the interview:

Obviously some of them are retired employees of the city and then under their guidance they’ll figure out what the projects are. So obviously, we have to follow them because they are the supervisors … Some of them are more flexible, some are more on the conservative side. They were not open to suggestions. That was a bit of reality I had to face. On the other hand, those centers which do not have civil servants on staff have to go through the various difficulties of the bureaucratic system, which makes it difficult to conduct many of their activities.

Even though the presence of civil servants helped the centers in navigating the bureaucratic jungle of the local government, as was clear from Ms. Jones’s interview, there was a varied level of flexibility and progressive thinking among such staff members. In the case of Mr. Katō, who had a lot of progressive ideas about the activities of the center, there was a civil servant staff working under his supervision and bridging the center’s activities with the municipal government. From our observations, it was obvious that the presence of the civil servant staff was a big advantage for the center. On the other hand, a Chūbu area Rural Populated center staff, Mr. Yoshida, mentioned that it was getting less exciting to work in the center and he expected to transfer to a department of the local government in the coming years. Thus, it was not only about the inner personnel politics, but also individual involvement and passion that affected centers’ activities.

Finally, a concern that Ms. Jones voiced in the interview was, who was the target for the centers’ activities? As we mentioned earlier, according to the Tabunka Kyōsei Plan, there are different tasks that centers address, and one of them is local revitalization. The interpretation of this task depends on the particular government and area, but Ms. Jones pointed out that in order to survive, Metropolitan centers reoriented their activities towards Japanese residents and temporary visitors (mainly tourists). This can potentially sway tabunka kyōsei activities away from the more important long-term perspective, which is to help accommodate foreign residents.

Discussion and conclusion

This study aimed to review current immigration initiatives, the government’s Tabunka Kyōsei Plan, and the implementation of tabunka kyōsei at centers for international exchange. We focused our study on these centers because they represent intermediaries between the policy makers, local municipalities, and foreign residents.

First, we can see from the historical overview that the government has continually relied on loopholes in its own laws to attract a low-skilled labor force. Furthermore, while there are officially no immigration and integration policies, local governments took the lead in pioneering local incorporation policies and eventually pushed for tabunka kyōsei, a prototype of an integration policy that is intended for Japan’s ethnic minorities as well as foreign residents.

Currently, there is no clear vision in government policy on how foreign workers will be hired and settled in Japan or whether they will concentrate in some particular areas and be hired by certain employers. The government is bringing in foreign labor and implementing patchwork integration programs in certain municipalities without introducing blanket immigration and integration policies nationally. If the government were to create a blanket policy, then it could be monitored and changes made as necessary. However, if policies are implemented patchwork at the local level, then there will be local interpretations, local implementations and more limitations that can lead to a higher possibility of program failures.

In terms of integration programs and tabunka kyōsei in particular, there is still no clear vision of the targets for these programs. The Tabunka Kyōsei Plan promoted by the government provides mostly frameworks for the program’s implementation – it gives flexibility to local municipalities and centers to implement it according to the needs of foreign and local residents depending on the region. However, as we observed during our interviews, current budget cuts constrained the viability of the centers’ programs. The introduction of more programs for Japanese citizens might lead to the return of the centers to a version of their initial function in the 1980s – the internationalization of Japanese residents.

In relation to centers, the most popular type of activities provided are Japanese language classes. The selling point of these classes is that compared to regular language schools, these are more oriented to individuals’ needs, cheap, and aimed to create networks with local Japanese citizens. However, the centers struggled with budget cuts, the difficulties of reaching larger numbers of foreign residents and involving them and local citizens in joint activities, and eventually creating a multicultural community. Also, structural and bureaucratic constraints related to the organization of the centers and their connection with local municipalities put heavier pressure on the staff. This will lead to future problems for integration in rural and less populated areas, as these areas will likely accept a large influx of foreign workers in the coming years.

Moreover, there might be differing expectations from foreign and local residents toward centers and their actual role. The centers are supposed to be an initial entry point for foreign residents that face some particular issues – their main role is mediation and not actual help. While we recognize that there are limitations to the resources that local governments can provide, it might appear misleading to foreign residents about what can and cannot be done in their situations. In addition, the increase in foreign residents will also result in larger numbers of their issues pushed to local bureaucratic organizations and NPOs/NGOs to deal with and resolve.

We provide a typology of centers to show the preparedness of different geographic locations to accommodate an influx of foreign workers. It was clear from our data that there was a low level of preparedness for these organizations to accommodate a large number of foreign workers with diverse backgrounds, particularly with the more rural centers. Overall, even though the national government created a general framework, tabunka kyōsei, to integrate foreign residents, and local governments provide financial support to these organizations, there is no professional coordination of activities among these centers that would make them more functional and useful for foreign residents.

For future research, we believe it is important to compare various settlement/integration programs in other countries to create clear definitions of tabunka kyōsei’s goals and how they can be achieved. Perhaps more importantly, it is necessary to create a multilateral dialogue between the national government, local governments and centers, NGOs/NPOs, and academia. This dialogue can bring various voices together and provide both theoretical and practical solutions to issues that are presently only addressed separately by these various actors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Viktoriya Kim

Viktoriya Kim is Associate Professor of Sociology in the Human Sciences International Undergraduate Degree Program at Osaka University, Japan. She holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the Osaka University Graduate School of Human Sciences. Before joining the faculty there, she was a Research Assistant in the Afrasian Research Centre at Ryukoku University. Viktoriya’s research interests are in international marriage, mainly of women from the Former Soviet Union countries married to Japanese men, the integration of foreign residents into Japanese society, global migration, and mixed-heritage children and their education.

Philip Streich

Philip Streichis currently serving as Associate Professor at Osaka University, where he teaches and conducts research on East Asian politics and international relations. Dr. Streich has authored The Ever-Changing Sino-Japanese Rivalry (2019) and has co-authored a collection of unusual episodes from international relations entitled Weird IR: Deviant Cases in International Relations (Mislan & Streich 2019). He has been teaching in the School of Human Sciences at Osaka University since 2015. Dr. Streich has also taught at Haverford College, Pomona College, and Rutgers University. He earned his PhD in political science from Rutgers University in 2010.

Notes

1 Hereafter, we use “centers for international exchange” or simply “centers” to refer to these institutions.

2 Prefectural-level centers, associated with the Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR), serve the foreign residents of the prefectural capital, but many also set up exchange programs with other countries’ cities and promote prefectural trade and tourism. Additionally, there is a tentative proposal to add “One Stop Centers” in approximately 100 locations across the country. These would provide advice, interpretation, and consultation services to foreign residents, similar to centers for international exchange (Ministry of Justice, Citation2018a).

3 The center does not collect or disclose information on the ethnicity of foreign visitors at the information window, but the most used languages were English, Chinese, and Japanese. There was also a small number of those who used Korean, Tagalog and other languages.

4 While there was no information available on the nationalities of foreign users of the center, official data for the whole prefecture indicated that about half of non-Japanese residents were from South America (mainly Brazil) and one-third were comprised from Chinese and Koreans (including zainichi Koreans).

5 There were fluctuations in the number of constant project members, since not all of them were permanent or long-term residents in Japan.

6 The core members of the project were mainly local foreign residents, since it was aimed at foreign nationals. However, local Japanese citizens were involved, depending on the type of activity.

7 While there was no information available on the nationalities of foreign users of the center, official data for the area indicated the majority of non-Japanese residents were of East Asian, South-East Asian, North American and South Asian descent.

8 Most of the low-skilled workers were from South-East Asian countries; however, some areas represented by this type of center also had South American (mainly nikkei) and East Asian foreign residents.

9 Foreign spouses were mostly women from East and South-East Asian countries.

10 These were mostly workers from South-East Asia. However, some centers situated in the Chūbu and Kansai areas also had a significant number of nikkei users.

11 We use pseudonyms to refer to all participants of the study to protect their privacy.

References

- Abe, A. (2007). Japanese local governments facing the reality of immigration. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 5 (9). https://apjjf.org/-Atsuko-ABE/2522/article.html

- Asahi Shimbun. (2018, December 26). (Shasetsu) Gaikokujin Kyōseisaku raretsude owaraseruna [(Editorial) plan to live with foreigners, don’t finish on statements]. Asahi Shimbun (Morning Edition), p. 12.

- Bradley, W. S. (2014). Multicultural coexistence in Japan: Follower, innovator, or reluctant late adopter? In K. Shimizu & W. S. Bradley (Eds.), Multiculturalism and conflict reconciliation in the Asia Pacific: Migration, language and politics (pp. 21–43). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burgess, C. (2007). Multicultural Japan? Discourse and the ‘Myth’ of homogeneity. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 5(3), 1–25. https://apjjf.org/-Chris-Burgess/2389/article.html

- Chiavacci, D. (2014). Indispensable future workforce or internal security threat? Securing Japan’s future and immigration. In W. Vosse, R. Drifte, & V. Blechinger-Talcott (Eds.), Governing insecurity in Japan: The domestic discourse and policy response (pp. 115–140). Routledge.

- Chung, E. A. (2010). Immigration and citizenship in Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- Hamamatsu City. (2013). Hamamatsu intercultural city vision. Hamamatsu City. https://www.city.hamamatsu.shizuoka.jp/kokusai/kokusai/documents/iccvision_en.pdf

- Kagami, T. (Ed.). (2017). Tabunka kyōseiron - tayōsei rikaino tameno hinto to ressun [Multicultural coexistence - Hints and lessons to understand diversity]. Akashi Shoten.

- Kashiwazaki, C. (2011). Internationalism and transnationalism: Responses to immigration in Japan. In G. Vogt & G. S. Roberts (Eds.), Migration and Integration - Japan in comparative perspective (pp. 41–57). Iudicium.

- Kawamura, C. (Ed.). (2012). 3.11 gono tabunka kazoku - miraiwo hiraku hitobito [Multicultural family after March 11th - People leading future]. Akashi Shoten.

- Kibe, T. (2011). Immigration and integration policies in Japan: At the crossroads of the welfare state and the labour market. In G. Vogt & G. S. Roberts (Eds.), Migration and Integration - Japan in Comparative Perspective (pp. 58–71). Iudicium.

- Kibe, T. (2014). Can Tabunkakyōsei be a public philosophy of integration? Immigration, citizenship and multiculturalism in Japan. In W. Vosse, R. Drifte, & V. Blechinger-Talcott (Eds.), Governing Insecurity in Japan: The domestic discourse and policy response (pp. 71–91). Routledge.

- Komai, H. (2015). Nihonni okeru ‘imin shakaigaku’no iminseisakuni taisuru kōkendo [How sociological migration researches contribute migration policies in Japan]. Japanese Sociological Review, 66(2), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.4057/jsr.66.188

- Kondo, A. (2015). Migration and law in Japan. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 2(1), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.67

- Liu-Farrer, G. (2020). Japan and immigration: Looking beyond the Tokyo Olympics. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 18(4,5), 1–8. https://apjjf.org/2020/4/Liu-Farrer.html

- Mabuchi, H. (2018, November). A country with no immigration policies: Its realities and challenges. Paper presented at the International Metropolis Conference 2018, Sydney.

- Menju, T. (Ed.). (2017). Jichitaiga hiraku nihonno imin seisaku - jinkō genshō jidaino tabunka kyōseiheno chōsen [Japanese migration policy led by local governments - Attempt to implement Tabunka Kyōsei in the era of declining population]. Akashi Shoten.

- Ministry of Home Affairs. (1987). Chihō kokyō dantai ni okeru kokusai kōryū no arikata ni kansuru shishin [Guidelines for local authority’s international exchange programs]. http://www.soumu.go.jp/kokusai/pdf/sonota_b8.pdf

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication. (2006). Chiiki ni okeru tabunka kyōsei suishin puran [Plan for the promotion of tabunka kyōsei in local communities]. http://www.soumu.go.jp/menu_news/s-news/01gyosei05_02000032.html

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication. (2017). Tabunka kyōsei jireishū: Tabunka kyōsei suishin puran kara 10 nen tomoni hiraku chiiki no mirai [Examples of tabunka kyōsei: 10 years from the implementation of plan for the promotion of tabunka kyōsei: Opening together the future of local community]. http://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000476646.pdf

- Ministry of Justice. (2005). Part I. Immigration control in recent years. http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyukan_nyukan46.html

- Ministry of Justice. (2011). Part I. Immigration control in recent years. http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyuukokukanri01_00015.html

- Ministry of Justice. (2013). Part II. Immigration control in recent years. http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyuukokukanri06_00042.html

- Ministry of Justice. (2016a). H.26.12 getsu matsu (kakuteichi) kōhyō shiryō [Heisei year 26, end of December (final value) public information]. http://www.moj.go.jp/content/001234011.pdf

- Ministry of Justice. (2016b). Part I. Immigration control in recent years. http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyuukokukanri06_00068.html

- Ministry of Justice. (2018a). Comprehensive measures for acceptance and coexistence of foreign nationals. Retrieved from http://www.moj.go.jp/content/001301382.pdf

- Ministry of Justice. (2018b). Part I. Immigration control in recent years. http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyuukokukanri06_01126.html

- Ministry of Justice. (2019). [Heisei 30 nenmatsu] kōhyō shiryō [End of Heisei year 30. Public information]. http://www.moj.go.jp/content/001289225.pdf

- MIPEX (Migrant Integration Policy Index). (2015a). Japan. http://www.mipex.eu/japan

- MIPEX (Migrant Integration Policy Index). (2015b). What is MIPEX? http://www.mipex.eu/what-is-mipex

- Modood, T. (2007). Multiculturalism. Polity.

- Satake, M., & Kim, A. (Eds.). (2017). Kokusai kekkon to tabunka kyōsei - tabunka kazoku no shien ni mukete [Intermarriages and multicultural co-existence: In support of cross-cultural families in Japan]. Akashi Shoten.

- Shipper, A. W. (2008). Fighting for foreigners: Immigration and its impact on Japanese Democracy. Cornell University Press.

- Sieg, L., & Miyazaki, A. (2018, December 8). Japan opens door wider to foreign blue-collar workers despite criticism. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-japan-immigration/japan-opens-door-wider-to-foreign-blue-collar-workers-despite-criticism-idUSKBN1O700W

- Takaya, S. (2018). Naze imin seisakuga kakuritsu sarenainoka - nihonni okeru iminwo meguru seiji to riberaru torirenma (Why hasn’t established the official migration policy?: Migration politics and liberal Trilemma in Japan). Shakai Riron to Dotai (Social Theory and Dynamics), 10, 58–77.

- Tamura, T. (2012). Gaikokujinga seikatsu suru ‘genba’deno kadai, torikumi nitsuite –NPO, tōjisha komyunitino torikumiwo chūshinni [About tasks and efforts from ‘on-site’ of foreigners’ lives – Efforts of NPOs and interested parties]. “Gaikokujintono kyōsei shakai” jitsugen kentō kaigi dai 3kai [The 3rd Realization Review Meeting of “Inclusive Society with Foreigners”]. Cabinet Secretariat, Tokyo. https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kyousei/dai3/sidai.html

- Tegtmeyer Pak, K. (2000). Foreigners are local citizens, too: Local governments respond to international migration in Japan. In M. Douglass & G. S. Roberts (Eds.), Japan and global migration: foreign workers and the advent of a multicultural society (pp. 246–275). Routledge.

- Uchida, H. (2018, December 19). (Heiseiwa ima) gaikokujin ukeire Osaka [(Heisei now) acceptance of foreigners, Osaka]. Asahi Shimbun (Evening Edition), Front Page.

- Vogt, G. (2014). Friend of foe: Juxtaposing Japan’s migration discourses. In W. Vosse, R. Drifte, & V. Blechinger-Talcott (Eds.), Governing insecurity in Japan: The domestic discourse and policy response (pp. 50–70). Routledge.

- Yamamoto, K. (2019, February 8). Japanese Cities lack support for foreign residents, poll shows. Nikkei Asian Review. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Japan-immigration/Japanese-cities-lack-support-for-foreign-residents-poll-shows