ABSTRACT

With the proliferation of several dozen new exhibits and museums dedicated to this specific disaster, the 3.11 Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster, can be considered a turning point in the preservation of disaster memory in Japan. Although there is limited research on disaster museums, they play a significant role in shaping cultural memory of 3.11, as they are regarded as reliable, objective institutions of memory. Through analysis of 17 government-established 3.11 museums, this research explores the following questions: How do public disaster museums frame their representations of 3.11, and what official narrative is created within the cultural memory of the triple disaster in Japan? Drawing from analysis of the museums’ mission statements and exhibitions, and interviews with curators and museum staff, we argue that most disaster museums support narratives of overcoming hardships to contribute to a better future, showing continuity with narratives typical of other memorial museums such as WWII, or pre-3.11 disaster museums. In contrast to the commemoration of war and its influence on cultural memory, disaster museums have received relatively little scholarly attention. Yet, these forward-looking messages, combined with tendencies of museums to focus on local disaster experiences and emphasize disaster risk reduction with an artificial separation between man-made disasters vs. natural hazards, contributes to an othering of the Fukushima nuclear disaster in cultural memory, as an outlier in Japan’s long history of disasters. Without full representation of the compound disaster, understanding of 3.11 and the effective transmission of the intended lessons is severely limited.

Introduction

More than eleven years have passed since the devastating Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster on 11 March 2011, known as “3.11.” As recovery of disaster-affected communities continues, remaining challenges include declining and aging populations, radioactive decontamination and nuclear power plant decommissioning that will continue for decades. Government housing reconstruction projects were completed in December 2020 (Reconstruction Agency 2021), although more than 40,000 survivors were still displaced eleven years after 3.11. Through massive investments in infrastructure, recovery projects have drastically altered the landscape; mountains have been cut, land elevated, and giant seawalls built along much of the Tohoku coastline.

As reconstruction replaces scenes of devastation from March 2011 and former townscapes, it becomes increasingly difficult for anyone coming from outside to imagine the impact of the disaster, or Tohoku’s pre-3.11 coastal scenery. To counteract the fading of memory, soon after 3.11, survivors, academia, and government agreed on the importance of documenting experiences and passing on lessons to prevent similar tragedies from happening again (Reconstruction Design Council Citation2011).

As it would impede recovery progress, not all disaster-affected objects can be preserved. Therefore, the question arises: what will be remembered, forgotten, and/or included in narratives informing cultural memory (Assmann Citation1995) of 3.11? This narrative began to take shape three months after March 2011, when the Reconstruction Design Council (Citation2011) stated as the first of its seven principles for the reconstruction framework:

For us, the surviving, there is no other starting point for the path to recovery than to remember and honor the many lives that have been lost. Accordingly, we shall record the disaster for eternity, including through the creation of memorial forests and monuments, and we shall have the disaster scientifically analyzed by a broad range of scholars to draw lessonsFootnote1 that will be shared with the world and passed down to posterity.

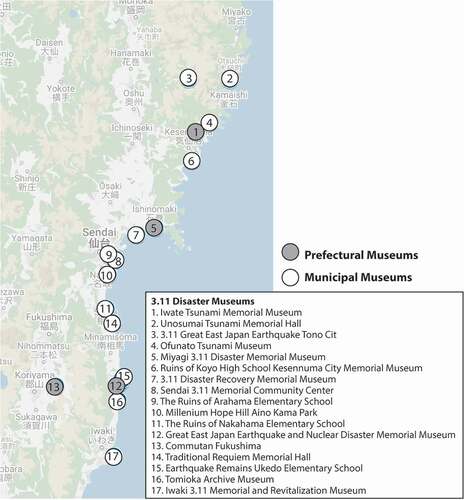

This statement set the trajectory of strong official and financial support for disaster heritage preservation and defined a framing that prioritizes certain kinds of memories over others, highly valuing memories representing lessons for future disaster risk reduction (bōsai). With strong commitments from national and local governments and enthusiasm from local people and organizations, there was a rapid emergence of new disaster memorial museums and exhibits in 3.11-affected areas (; ) greatly outnumbering pre-3.11 disaster memorial museums (Maly and Yamazaki Citation2021, Mirai Support Citation2020, Asahi Shimbun Citation2020; Densho Road Promotion Organization Citation2021). Pre-3.11 modern Japanese disaster memorial museums tended to tell the story of a single disaster in one place, with the main narrative of each disaster represented primarily by a single museum. In contrast, as a result of various factors, including the vast scale and extent of damage of 3.11, along with the validation (and funding) provided by the national government for implementation at local and regional government levels, narratives and experiences related to 3.11 are decentralized across the disaster area, presented by multiple museums and exhibits in their respective locales. Along with standardized funding for memory-transfer facilities, recovery planning resulted in vast areas of tsunami-damaged land where residential use is now prohibited. Many new museum facilities are located within these areas, which include the sites for each of the large museums created by the governments of the three most severely damaged prefectures. In addition to the use of tsunami-inundated land acquired by the government, local municipalities were also able to preserve tsunami-damaged buildings in these areas and convert their uses to museum facilities. For instance, multiple former school buildings have been converted into facilities to teach visitors about the experiences and lessons of 3.11 (Gerster and Fulco Citationforthcoming).

Table 1. Government-run 3.11 disaster memorial museums analyzed in this paper.

Shaped by official and local expectations for their purpose, these numerous newly-emerging disaster memorial museums (saigai denshōkan) share strong commonalities – approaches, methods, and themes – influencing the memory of 3.11.

Scholars have explored the processes of memory transmission after the Great East Japan Earthquake such as meanings of disaster heritage sites (shinsai ikō) for local communities (Sakaguchi Citation2019, Citation2021), kataribe activities (Fulco Citation2017, Citation2021; Gerster Citation2021; Nagamatsu, Fukasawa, and Kobayashi Citation2021), post-disaster tourism (Martini and Minca Citation2018; Martini and Buda Citation2019; Kato Citation2018), and disaster memorials (Boret and Shibayama Citation2017). Some literature deals with 3.11 museums in connection to dark tourism (Gerster, Boret, and Shibayama Citation2021), or in relation to geo-tourism (Mignon and Pijet-Migoń Citation2019). Yet surprisingly, there is still little scholarship that focuses directly on Japanese natural hazard disaster museums (Hayashi Citation2016; Littlejohn Citation2020; Maly and Yamazaki Citation2021; Ono et al. Citation2021). However, analysis of their exhibitions is vital for understanding cultural memory in Japan, as they demonstrate continuity of narratives of overcoming hardships – while omitting questions of responsibility – introduced by war or peace museums and pre-3.11 disaster museums reflecting a shared moral duty to remember (Landsberg Citation2007) and reframe traumatic events for didactic purposes (Meskell Citation2002).

Following the funded mandate from the national government to “pass on the lessons” from 3.11, with few exceptions, post-3.11 disaster memorial museums were created by local or regional governments. Towards the formation of the cultural memory and making meaning of the events of 3.11 and after, These museums play a key role in the formation of the cultural memory and making meaning of the events of 3.11 and after, representing “official” (government) narratives. As public museums, they transmit a story of 3.11 in the way national and local governments want it to be seen (Dubin Citation1999). While there are other less formalized ways of remembering and passing on the stories of 3.11, such as those mentioned above, these museums play a primary role, especially for visitors with no experience of the disasters. Museums represent greater long-term stability as physical sites holding and disseminating information, compared to activities that rely on individuals/volunteers, which may struggle for financial and human resources and may easily change over time. Museums can also reach a larger number of visitors, including as part of tourism and educational programs supported by local and national governments as well as the private sector. This is especially the case for 3.11 disaster memorial museums, widely promoted as part of tourism programs, and for whom the majority of visitors are students on school excursions (Gerster, Boret, and Shibayama Citation2021; Asahi Shimbun Citation2020). In addition, narratives presented in the official memorial museums may also be connected to and in turn affect other aspects of visitors’ experiences, such as in combination with a kataribe (disaster storytelling) tour, or experience organized through or in the museums.

This paper asks: how do government-run disaster memorial museums frame representations of 3.11, and what official narrative do they create? To explore these questions, we analyzed information, including mission statements, pamphlets, and exhibition contents of 17 government-established museumsFootnote2 (, ), drawing from notes and photo documentation from field visits between 2017–2021, and interviews with museum planning and implementation committee members, curators and (vice)directors of each of these museums, conducted primarily in 2020 and 2021.

Trauma, narratives, and the museum’s role in shaping cultural memory

The traumatic events of the massive 3.11 triple disaster significantly impacted Japanese society. “Only” eleven years since 3.11, most people remember where they were on that fateful Friday afternoon in 2011. However, as time passes, the way these events are recalled and told to generations who did not experience the disaster will increasingly be shaped by how this memory is passed on within institutions of cultural memory, such as media or museums.

An embodiment of institutional forms of memory, museums are vital in the formation of cultural memory (Assmann Citation1995), as they help create a “common pool of stories and figures of memory to which reference can be made” (Rigney Citation2016, 65), for instance by offering material and symbolic support through their exhibitions (Taylor Citation2010), needed to turn individual memory into collective or cultural memory spanning communities, nations, or even the globe. Unlike collective memory (Halbwachs Citation1980), which relies on communicative interactions between individuals to reconfirm, shape, or evoke certain memories, cultural memory refers to “fateful events of the past, whose memory is maintained through cultural formation (texts, rites, monuments) and institutional communication (recitation, practice, observance)” (Assmann Citation1995, 129). However, the borders between the mutually influencing concepts of collective memory and culture are permeable, as “culture mediates collective memory and gives it substance, form, and social reach” (Rigney Citation2016, 67).

Like other forms of cultural memory, museum exhibitions are products of negotiations embedded in politically and culturally specific environments (Rigney Citation2016, 70). How museums (are expected to) present certain memories may change over time, yet museums occupy an especially delicate role within cultural memory transmission. As museums hold the status of objective knowledge, “to control a museum means precisely to control the representation of a community and its highest values and truths” (Duncan Citation1995, 8). Yet as Dubin (Citation1999, 3) notes in Displays of Power, museums are also places where “society can define itself and present itself publicly. Museums solidify culture, endow it with tangibility, in a way few other things do.” Conversely, Takakura (Citation2015) stresses that as means of communication with the public, museums and exhibitions should be analyzed as rhetoric. With power over narratives (Benavides Citation2009) and as rhetoric, exhibitions can aim to influence public opinion. For instance, Taylor (Citation2010, 57) states that post-cold war nuclear museums in the U.S “serve as sites of struggle for the control of rhetoric that mediates public understanding of nuclear weapons development” (Taylor Citation2010, 57). Similarly, the 1956 Atoms for Peace exhibition that started in Hiroshima and toured Japan promoted the “safe usage of nuclear energy” to a Japanese public still suffering the effects of atomic bombs (Zwigenberg Citation2012).

The role of museums in representing cultural memory becomes especially important in relation to traumatic events that many would prefer to forget. Winter (Citation2006, 54) states, “[s]tarting in 1918, practices of remembrance have been first and foremost acts of mourning.” Practices of remembering being seen as increasingly important for society as a whole led to a “memory boom” – a global increase of museums (Arnold-de Simine Citation2013, 14; Winter Citation2006). With more than 90% of museums built after World War II (Boylan, Citation1995), one explanation for their still-growing numbers is a moral duty to remember (Landsberg Citation2007). As places where memories are stored in material form, museums and memorials become manifestations of how memories of a specific event are integrated in a broader (national) narrative, as well as sites of official public acts of commemoration underscoring the “collective nature of the activity of remembering” (Arnold-de Simine Citation2013, 11). The museum is a container for memory, remembering for society (Abt Citation2011, Citation2011), while simultaneously shaping how society remembers a certain event.

The overt connection between the construction of national narratives and memorial museums has been extensively analyzed in relation to wars and especially the Holocaust. Scholars have stressed how Japanese World War II museums and memorials tend to reframe dark history in forward-looking ways; avoiding questions of responsibility reinforces a national narrative of Japan as a victimized peaceful country (Gerster, Boret, and Shibayama Citation2021; Naono Citation2005; Sharpley and Kato Citation2021; Wu, Funck, and Hayashi Citation2013; Yoneyama Citation1999; Zwigenberg Citation2014). Crane (Citation2011, 105) explains how powerful narratives of never using atomic weapons presented at the Hiroshima Peace Museum and Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, serves a strong moral and didactic purpose – aspects needed for the preservation of negative heritage (Meskell Citation2002) and incentives for framing the commemoration of blameless victims rather than wartime actions of Japan as an aggressor. Crane (Citation2011, 105–106) emphasizes that as war museums, they lacked important messages: “Japan’s role in the war was marginalized, even though attention to its recent past and acceptance of its memory could have contributed to the message of peace. Local experiences, so horribly and uniquely traumatic, dominated the institutions created in their memory.” Zwigenberg (Citation2014) also highlighted the strong foregrounding of positive messages using Japan’s war-related heritage while simultaneously avoiding questions of responsibility, pointing out that the Hiroshima Peace Museum’s exhibit narrated “history in a passive voice” (Gluck Citation1990), “like the scene from a natural disaster, separated from any chain of historical events” (Zwigenberg Citation2014, 2). Similar observations on the role of war museums within so-called “peace tourism”, such as the Chiran Peace Museum in Kagoshima Prefecture, point out how the loss of young Kamikaze pilots is detached from any discussion of their role in the war and presented under a general message of the importance of peace (Sharpley and Kato Citation2021).

There is a well-established body of literature on the implications of war museums for cultural memory. Yet perhaps because of a common (mis)understanding that unlike man-made disasters or war, natural hazard disasters strike without bias and without someone to blame, disaster memorial museums have received less attention.

Disaster memorial museums in Japan pre-3.11

“What is a disaster” is a question discussed at length by many scholars with varying responses across disciplines (Dombrowsky Citation1998; Hood Citation2012; Perry (Citation2018 (2007)); Quarantelli Citation1998; Sato and Imamura Citation2018; Tierney Citation2019). As we cannot do justice to the scope of this discussion in this paper, instead we follow the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR, Citation2022) who defines disasters as “serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society,” of any scale due to the interaction of hazardous events with “exposure, vulnerability and capacity” resulting in “human, material, economic and environmental losses and impacts” (UNDRR, Citation2022). Disaster scholars have long emphasized that “there is no such thing as a natural disaster” (Landsberg Citation2007), as disasters are actually the impact of a hazard event on society. Experiences and representations of disasters are directly shaped by social, economic, political, and historical factors. Just as with museums about war and conflict, disaster museums face similar questions of responsibility.

In Japan, the strong separation between so-called “natural” disasters occurring after natural hazard events, and other disastrous events leads to parallel museum traditions. For instance, neither the above mentioned war museums (Yoshida Citation2007; Fallows Citation2014) nor those passing down the heritage of the Minamata diseaseFootnote3 are considered “disaster” museums in Japan. The Japanese distinction between so-called “natural” disasters (shizen saigai) and “manmade” disasters (jinsai) separates those “natural” events out of our control and human-caused events for which blame can be assigned (Asahi Shimbun Citation2021). Within the complex 3.11 disasters, the nuclear meltdown and disaster irreversibly muddies this artificial distinction between a blameless disaster caused by nature versus an event for which someone could be held responsible.

This paper considers disaster memorial museums as facilities whose primary function is telling the story of a specific or multiple disaster. Before 3.11, disaster memorial museums in Japan (saigai denshōkan) focused on commemoration of natural hazard event disasters (). As impacts were limited to local government jurisdictions, pre-3.11 disaster memorial museums focused on telling the stories of a disaster within a single municipality or prefecture.

The oldest modern disaster memorial museum in Japan, the Earthquake Reconstruction Memorial Museum in Tokyo, was established in 1931 to commemorate the reconstruction of the city after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake and has several unique aspects. With a strong memorial function, it was established not only as a museum, but as a mausoleum to hold the remains of people who perished in the fires after the earthquake. After Tokyo was again destroyed by U.S. bombing during World War II, the museum was renamed the Tokyo Reconstruction Memorial Museum in 1951; memorial (mausoleum) and museum functions were expanded to encompass both tragedies.

Several new disaster memorial museums were established after the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake struck Kobe City and Hyogo Prefecture. Established in 1998 on Awaji Island, the Nojima Fault Preservation Museum includes a section of the actual earthquake fault. In 2002, a large museum, the Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution (DRI), was established in Kobe City by Hyogo Prefecture, with funding from the national government, including many donated objects whose display residents considered important.

Around the same time, several museums commemorating earlier disasters were established. The Okushiri Tsunami Memorial Museum was established in 2001 to memorialize the 1993 Hokkaido Southwest Offshore Earthquake and tsunami on Okushiri Island. In 2002 the Mt. Unzen Disaster Memorial Hall was built within the Unzen Geopark in Nagasaki Prefecture, as a museum of the 1991 Unzen Fugen volcanic eruption, and 1792 Shibamara Disaster – a tsunami caused by a volcanic eruption. In 2007, the Inamura no Hi no Yakata opened in Hirokawa Town in Wakayama Prefecture, commemorating the historic 1854 Ansei Tōkai Earthquake and Tsunami disaster and its famous story of disaster prevention.

The newest pre-3.11 museum, the Chuetsu Memorial Corridor was established in 2011 to commemorate the 2004 Chuetsu Earthquake in Niigata Prefecture. Its network of facilities in multiple towns includes four facilities (Nagaoka Earthquake Disaster Archive Center Kiokumirai in Nagaoka City; Ojiya Earthquake Disaster Museum Sonaekan in Ojiya Village; the Bonds/Ties Kizuna Center community space in Kawaguchi Village, and Yamakoshi Restoration Exchange Center Orataru in Yamakoshi Village) and three parks (“Park for Prayer” in Myoken, “Park for Remembering” in Kogomo, and “Park for Beginnings” at the earthquake epicenter) in different communities. The unique decentralized design of the Chuetsu Memorial Corridor and close connections to local communities allow visitors to experience the connection of local culture as well as disaster information (Hayashi Citation2016).

With the exception of the Earthquake Reconstruction Memorial Museum, the pre-3.11 museums were established after the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in Kobe. As the first urban disaster since World War II, the earthquake in Kobe can be seen as a turning point in Japan for disaster mitigation and recovery policy. As risks had not been widely understood, this unexpected earthquake motivated local people and officials to convey their experiences as lessons toward improved future preparedness. This focus on bōsai shaped the mission and function of DRI’s exhibits, and became a model for other disaster memorial museums. Commonalities among missions and exhibits with the message of bōsai shared among multiple museums is not only the result of being inspired by precedents, but also due to the fact that the majority of museums and exhibits are outsourced to the same several companies.

The path and experience of visitors to DRI represent typical parts (and pedagogical goals) of pre-3.11 disaster museum exhibits: a simulation of the (frightening) reality of the time of disaster; a detailed explanation of what occurred afterward, including data, records and peoples’ stories; scientific explanations of natural hazard mechanisms (earthquakes, liquefaction, etc.) and predictions (hazard maps, etc.); and finally, instructive messages for personal actions that can be taken to prepare for future disasters. Visitors have options to hear (pre-recorded or in person) stories of disaster storytellers (kataribe) or participate in other disaster mitigation events for the public.

The six modern pre-3.11 disaster memorial museums (excluding Tokyo) commemorate contemporary and historic natural hazards disasters – earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions – with a shared focus on conveying what happened at the time of the disaster in order to raise awareness and encourage people to take action to prepare for future disasters. With a focus on natural hazard-induced disasters, or shizen saigai, the pedagogical mission of bōsai that is also shared by pre-3.11 disaster memorial museums, specifically learning from disaster experience to “avoid repeating the same tragic events,” was already well established before 3.11 Yet, this understanding of disasters and disaster memorial museums is challenged by the complex reality of 3.11.

The “disaster risk reduction” (bōsai) narrative and the shaping of the new disaster memorial museum

The long history of recurring tsunamis in the Tohoku region and tremendous destruction caused by the 2011 tsunami led to the government’s promotion of relocation away from tsunami-damaged areas as a main approach of recovery planning. Many resulting large open spaces, voids left in former residential areas, have been converted into sites for disaster memorial facilities (shinsai denshō shisetsu) and disaster memorial parks. Pre- and post- 3.11, disaster museums were typically sited at places (or in buildings) with local significance connected to disaster impact/experience.

The Disaster Memorial Network Council and the 3.11 Densho Road Promotion Organization (Citation2021) define disaster memorial facilities as having the purposes of understanding: 1) lessons from the disaster; 2) disaster prevention and preparedness; 3) the horror of disasters and the fearsomeness of nature; 4) facilities with historic or academic value related to disasters; and 5) other facilities that communicate the facts of the disaster and the lessons learned from it.

This shows the integration of disaster risk reduction within the definition of memorial facilities. As of June 2021, the more than 164 plates and descriptions included markers showing tsunami run-up heights and stone memorials (ireihi). With their numbers still growing, 111 facilities or places that preserve the memory of 3.11 and teach lessons learned, such as museums, exhibits, memorial parks or disaster heritage sites, are registered in the Densho Road Network (Densho Road Promotion Organization Citation2021). Due to the large number of preserved objects and newly built museums in Northeast Japan, Littlejohn (Citation2020, 3) even speaks of a “museumification” of the Tohoku region. Among these memorial facilities is the newly introduced category of disaster heritageFootnote4 (shinsai ikō), buildings that show traces of the earthquake or tsunami, often repurposed as museums or facilities containing exhibitions on the impact of the disaster at that place. As Sakaguchi Citation2019, 15; Citation2021, 182) points out, disaster heritage sites existed before 2011, but their numbers were limited to a few buildings, such as a school building that was damaged by the 1990 Mt. Unzen eruption, or objects that show the damage of the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake at the Meriken Park in Kobe. Reflecting what is known as a “memory boom”, in which, “over the last few decades, the prominence and significance of memory has risen within both the academy and society” (Arnold-de Simine Citation2013, 14), the increasing scale of preservation efforts has produced Tohoku’s own memory boom.

Among the manifold disaster memorial facilities, this research focuses on government-sponsored disaster memorial museums due to their dominance and significance for the collective and cultural memory of the 3.11 disasters as explained above. To provide an overview of how these institutions shape narratives on 3.11, lists the 17 prefectural and municipal 3.11 museums and their mission statements, with their locations shown on . In addition to 16 disaster memorial museums, whose primary focus is on telling the story of a specific or several disasters,Footnote5 analysis also included the Commutan which is defined as a science communication museum, as the first prefectural permanent exhibition on the nuclear disaster.Footnote6

Prefectural museums, highlighted in in grey (1, 5, 12 and 13), tell the story of the prefecture, attempting to include a balanced selection of cases from different towns within the prefecture (Shibayama, Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum planning committee member, Tohoku University; Interview 2020).Municipal museums (2–4; 6–11; 14–17) focus on the damage and experiences of the entire town and/or more localized experiences of smaller communities.Footnote7 In museums created using disaster-damaged buildings (shinsai ikō; 6, 7, 9, 11, 15), exhibits focus on events that occurred in that place, often including recovery processes.

Exhibitions tend to focus on either the tsunami and earthquake (1–11 and 14–16) or the nuclear disaster (12, 13). Only two of the 17 museums focus on the nuclear disaster, whereas three others include it as part of their exhibitions (15–17), all of which are located in Fukushima Prefecture. Although areas outside of Fukushima Prefecture, including Tochigi, Saitama, Miyagi and Iwate Prefectures, also suffered from radioactive contamination, the nuclear disaster is only marginally addressed in exhibitions outside of Fukushima. As a result, with few exceptions, such as the Tomioka Archive Museum (16), almost no museum aims to cover the compound aspects of the triple disaster. Furthermore, even within Fukushima Prefecture, which experienced both the tsunami and nuclear radiation, most museums focus on the tsunami. Most mission statements include a purpose of disaster education and risk reduction, connecting to the goal promoted by the Reconstruction Design Council (Citation2011). Almost all statements emphasize the need to pass on lessons (kyōkun), and phrases like “to never happen again” (ni do to okoranai yō ni) are common in both mission statements and exhibitions.

Most exhibitions directly represent the museums’ mission statements. The prefectural memorial museums (1, 5, 12 and 13) are all newly built facilities located in recovery parks, created by large-scale national government projects. Prefectural as well as municipal museums (2–4; 6–11; 14–17) that focus on the earthquake and tsunami share a tendency to highlight educational aspects; both the Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum and the Miyagi 3.11 Disaster Memorial Museum welcome visitors with displays about the science and history of earthquakes and tsunamis in the Tohoku region and worldwide. They further introduce examples of successful and unsuccessful evacuation procedures and clearly state what kind of lessons should be drawn from the 3.11 experience through statements in documentary films and display text: to immediately evacuate to higher ground; to always be prepared; and to be ready for a tsunami that could surpass all expectations.

Likewise, museums established in preserved and converted ruins of school buildings (6, 7, 9, 11, 15)Footnote8 feature exhibits with pictures of the tsunami’s impact on the school and videos of school staff sharing their memories of evacuation procedures and/or the long road of recovery. Kesennuma City Memorial Museum in Koyo High School displays debris and a car that was swept inside the third floor of the building. Nakahama Elementary School in Yamamoto Town was preserved as it was after the tsunami, with a bent ceiling laying open pipes and cables, and flooring tiles scattered around the rooms to convey the threat of the tsunami. Sendai City’s Arahama Elementary School even displays various emergency goods, such as emergency food, blankets, or an emergency toilet, to educate visitors on what they should prepare in case of another disaster. In most museums, tsunami survivors play a significant role in guiding visitors through the exhibitions as museum guides and kataribe sharing additional information about how the disaster unfolded, personal survival stories, and what everybody should do to protect themselves. Ukedo Elementary School in Namie Town, Fukushima Prefecture, added scenes from a picture book about the happenings on March 11 at the school to the empty school rooms that allow visitors to imagine the evacuation procedure of the children.

In general, museums outside of Fukushima Prefecture clearly tell “lessons learned” and display a master narrative of preventing future disasters. Objects damaged by the earthquake or tsunami convey the threat of these hazards, while videos and/ or kataribe guides formulate specific messages of disaster preparation, fulfilling the “moral duty” of remembering traumatic events (Landsberg Citation2007). Moreover, their narratives continue established patterns of framing disaster memories: natural hazards are unavoidable, but by passing on the experiences of the survivors, we can be better prepared in the future.

The focus and mission statements of disaster memorial museums in Fukushima Prefecture are more diverse. Interestingly, almost no museum focuses on all three aspects of the disaster, and only three of six mention the nuclear disaster in their mission statements (12,13 and16). Passing on lessons learned is a goal of the Iwaki 3.11 Memorial and Revitalization Museum and the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum, whereas only the latter focuses on the nuclear disaster.

Like museums in Iwate and Miyagi Prefectures, the museum in Iwaki’s tsunami inundation zone tells how the tsunami devastated the area and offers interactive games for children to learn about disaster prevention. Videos teach about improvements in disaster mitigation made due to lessons learned from 3.11, while emphasizing that natural hazard events will strike again. In contrast, the Traditional Requiem Memorial Hall in Soma does not foreground lessons learned to the same extent, but displays photographs that convey tsunami impacts and a video informing visitors about the tsunami and recovery efforts. Whereas the museum in Iwaki presents itself as a place for learning, the hall in Soma defines its mission as being a gathering place for the bereaved and passing on the memories of that neighbourhood, aims given more weight by the memorial monument placed in front of the museum.

The two prefectural museums in Fukushima focusing on the nuclear disaster take very different approaches to the topic. While Commutan (13) is not a disaster museum per se, it was included in this analysis as the first prefectural facility that featured a permanent exhibition on the nuclear disaster. As a part of the Fukushima Prefectural Centre for Environmental Creation established in 2016, which aims at providing “radiation and environment education through exhibits” (Centre for Environmental Creation Citation2019, 2), exhibitions are based on the cooperation of local and national organizations – Fukushima Prefecture, the Japan Atomic Energy Agency, and the National Institute for Environmental Studies. As in many of the disaster memorial museums, the first room provides general information about what happened on March 11, using selected newspaper articles, interactive touch panels with additional information and a diorama of the destroyed nuclear power plant which serves as the basis for explaining the nuclear accident. The center of the main room features a digital clock that shows the time that has passed since 11 March 2011, introduced as the time that Fukushima Prefecture has been striving towards recovery. The rest of the museum is divided into an exhibition on renewable energy, explanations of radioactivity, and a theater that shows movies on Fukushima’s natural environment, recovery from the nuclear disaster, and scientific information on radiation.

The focus of Commutan’s exhibition is explaining the science of radiation. Plates and screens give information on background radiation in different parts of the world and how radiation levels changed in Fukushima Prefecture from soon after the accident until today. Unlike other public museums, a leading message in line with Fukushima Prefecture’s energy goal is strongly expressed: to work towards a future that does not rely on nuclear energy. In an interview, local staff revealed that positive feedback from their visitors has increased in recent years. However, Commutan has also been criticized for the lack of substantial information on harmful effects of radiation and lessons drawn from negative experiences, such as failures in using SPEEDIFootnote9 for the evacuation process (Goto Citation2019, Citation2021).

The Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum is part of the Fukushima Innovation Coast and the special recovery and revitalization zone in Futaba Town, of which 95% was still in the designated evacuation zone as of 2021. Although the museum’s mission statement highlights the need to pass on lessons learned, the exhibition does not clearly explain what these lessons are. As of January 2022, visitors are first invited to watch a movie that contextualizes the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant construction as part of Japan’s high economic growth phase, providing energy used for the economic development of Tokyo. This is a delicate topic, as although the host municipalities economically benefited from the nuclear power plant, many nuclear evacuees and returnees see the nuclear accident as the outcome of a long history of dependency rooted in the exploitation of Fukushima Prefecture by Tokyo (Gerster-Damerow Citation2019; Yokemoto and Watanabe Citation2015). Yet, the narrator quickly continues, “where there is light, there is shadow,” and stresses that it will take a long time for Fukushima Prefecture to recover from the accident. On the walkway leading to the second floor, headlines on the wall introduce a series of industrial development projects in Fukushima Prefecture, large-scale events negatively impacting society ranging from world wars and other large-scale nuclear disasters such as Three Mile Island, Chornobyl (Chernobyl), and Tokai nuclear power plant accidents, and finally Fukushima Prefecture’s steps towards recovery. Displays on the second floor include pictures representing Fukushima’s local culture and objects showing residents’ connection with the nuclear power plant before the accident, such as children’s school reports about visiting the plant. Other rooms focus on evacuation procedures, national and international support, video interviews with evacuees, the decontamination process, measures against bullying of nuclear evacuees, and “harmful rumours” about safety of products from the prefecture. Information on the recovery and decommissioning process is presented in the last room. There is also a room connected to the exhibit space where kataribe share personal stories several times a day.

Continuity and change in framing traumatic events: Disaster memorial museums and the othering of nuclear disaster in cultural memory.

As demonstrated by mission statements and exhibit descriptions, 3.11 disaster memorial museums select and frame memories in ways that are consistent with pre-3.11 disaster memorial museums in Japan and other museums presenting traumatic or negative events around the world. Phrases such as “to never repeat similar tragedies” can be found in almost all disaster memorial museums in Japan, directly overlapping messaging common at peace museums. Disaster memorial museums in Japan before and after 3.11 share didactic purposes for passing on lessons learned for disaster education. DRI in Kobe has played a fundamental role in setting the focus of disaster memorial museums in Japan to promote bōsai, with exhibits combining survivors’ narratives with the presentation of specific lessons learned and advice on how to prepare for future hazardous events. Similar elements and the involvement of survivors as kataribe guides at the facilities were introduced in almost all disaster museums built after the 1995 earthquake.

Although municipal disaster memorial museums focused on local aspects of disasters before 3.11, this trend intensified after 3.11. One reason for the increase of this local emphasis is that 3.11 is the first modern disaster that affected such a large number of communities and municipalities, across multiple prefectures and the first large-scale disaster in which the need to preserve and pass on lessons learned to posterity was emphasized almost immediately and combined with a budget for each municipality for precisely this purpose (Miyagi Prefecture Board of Education 2018; Reconstruction Design Council Citation2011). There has been debate about how much residents want to be reminded of their traumatic experiences through these preservation projects (Littlejohn Citation2020; Sakaguchi Citation2019, Citation2021; Shibayama Citation2021). However, many local residents and organizations are passionate that neither the disaster nor the life and local culture in the now-vanished neighborhoods should be forgotten. This is reflected by the way that most museums also feature photographs of how life was before March 11. Municipal museums especially tend to have gathering spaces, which also serve as community spaces, designed so that survivors are not automatically confronted with images of the disasters.

The sharp increase in 3.11 disaster memorial museums can be understood as a result of multiple social, political, and geographic factors. At the same time, as local governments and organizations were each striving to create their own facilities, the tendency of their exhibits to focus on local experiences can be further explained by the need to differentiate museums, not only to secure funding but to distinguish themselves within the growing number of 3.11-related exhibitions with ultimately the same target group of visitors who may only visit a limited number of memorial facilities. The Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum and the Miyagi Tsunami Memorial Museum, both which are considered “gateways to other museums,” deliberately do not aim to cover all aspects of the catastrophe to raise the incentive to visit other locations as well (Kumagai, deputy chief, Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum; Shibayama, Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum planning committee member, Tohoku University; Interviews 2020; Sato, Miyagi Tsunami Memorial Museum; Interview 2021). Exhibit contents from these and other museums also reflect similar attempts to distinguish each museum from others. For instance, whereas Commutan in Fukushima Prefecture focuses on the science of radiation, such explanations are not included in the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial. Although smaller memorial facilities are concerned about tendencies of bigger prefectural facilities to pull visitors, such strategies may contribute to encouraging people to visit multiple facilities, thereby gaining a better understanding of the disaster (Kumagai, deputy chief, Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum, Interview 2020; Seto, deputy chief, Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum Planning Division, Interview 2021). As a result, the expanded field of post-3.11 disaster museums across the Tohoku region represents a proliferation of museum narratives reflecting the complexity and vastness of the disaster, and at the same time an increased localization of disaster narratives conveying impacts and experiences that vary by place.

However, this local emphasis contributed to another trend of 3.11-related exhibitions: isolation of the nuclear disaster from the tsunami and earthquake. The regional focus allows even museums within Fukushima Prefecture to avoid addressing aspects of the nuclear accident. Here it is important to note that “Fukushima” represents not only a political problem, but it also affects relationships among disaster survivors. Residents in less contaminated areas find it hard to openly address issues related to radiation when other areas are affected more severely (Gerster Citation2019; interviews with kataribe 2020–2021). This might be especially the case for the museums in Iwaki and Soma that, despite being affected by the nuclear disaster, were never part of official evacuation zones. Further, nuclear evacuees faced discrimination because of their image as being polluted or spreading radiation, or for receiving compensation payments (Kawasaki Citation2021). This means that highlighting radioactive pollution may not be in the municipality’s interest, especially outside of Fukushima Prefecture.

These are only some of the difficulties these institutions face in regard to the interpretation of contemporary memory. The main challenge for public museums may be how to address the political aspects of “Fukushima.” Interviews with directors and curators revealed that prefectural museums in particular consider it their duty to deliver facts and information objectively. Political aspects or controversies seem to be avoided at these museums: citizen protests, controversial sea wall regulations, or gender issues are nowhere to be found. Because the nuclear disaster was politically charged from the very beginning, the exhibition of the prefectural museum in Futaba received even more critical attention than other disaster memorial museums. Shortly after its opening, the museum was criticized by visitors and journalists for not displaying the original plate of Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant’s host town Futaba with the inscription: nuclear power – the energy of a bright future (Asahi Shimbun Citation2021). Many consider this plate to be a symbol of the safety myth (anzen shinwa) regarding nuclear power and wanted it to be displayed as a constant reminder of the threats of this energy source. Other critiques were raised regarding the relatively small information plates on disaster-related deaths or about how SPEEDI was not used in the evacuation process. The museum responded to these critical voices by displaying the plate as well as adding and expanding the amount of related information, which is a slowly changing but still uncommon practice in Japanese public museums (FIPO Citation2021). Still, the strong emphasis on recovery, for instance, by focusing on decontamination rather than contamination, remained.

The most considerable controversy, however, revolved around an article published by the newspaper Asahi Shimbun (Citation2020) that reported about guidelines that discouraged kataribe guides to criticize “specific groups” (tokutei no dantai). According to Asahi Shimbun, this could mean that kataribe contracted by the museum were not allowed to speak their mind about the government and TEPCO, the operator of the destroyed nuclear power plant. In an interview, the deputy chief of the planning division clarified that such restrictions do not exist but that as a public museum, they still strive not to take sides in a political discussion as they needed to stay objective (Seto, deputy chief, Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum Planning Division, Interview 2021).Footnote10 The aim for objectivity and neutrality can become a hurdle for passing on lessons learned, because in case of the nuclear disaster, this is impossible without addressing matters of responsibility, such as the mistakes made by TEPCO and the government. As a museum strongly connected to the national government, it is also very difficult for the museum in Futaba to present clear messages of a nuclear-free future since this would be in opposition to the Japanese government’s plan to continue the use of nuclear energy. This approach presents a stark contrast to the Commutan, which mostly reflects the stance of Fukushima Prefecture that aims to meet the prefecture’s energy needs through renewable energy by 2040 (field notes, guided tour Commutan, 2021; Fukushima Prefecture 2018). These examples show how sometimes the messages of 3.11 memorial museums, although located in the same prefecture, can be very different depending on their operator.

In that sense, the framing of adverse history for didactic and moral purposes represents continuity with not only disaster mitigation narratives presented at disaster memorial museums before 3.11, but also with framing of war-related heritage sites. The shared narrative is one of overcoming hardships and learning for a better future while avoiding questions of responsibilities. The Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum additionally has to navigate its representations within the premise of community recovery that one day all evacuees will be given the option to return home – a process that Kawasaki (Citation2021) calls the erasure of evacuees (hinansha no zetsumetsu) – in favor of an image of successful recovery. Therefore, unlike museums on Chornobyl (Chernobyl) (Goto Citation2021), the overall exhibition emphasizes hope and recovery. It is important to note that this is not only the case for the nuclear disaster but that this tendency of focusing on positive, forward-looking lessons can also be seen in preservation processes related to the earthquake and tsunami. The vast majority of preserved buildings represent places of successful evacuation practices, whereas buildings that are directly connected to the loss of life are only rarely preserved – also because they may raise questions regarding why certain mistakes were made (Gerster and Fulco Citationforthcoming; Sakaguchi Citation2021).

Conclusion

3.11 disaster memorial museums’ representations of memory share a continuity with narratives of overcoming hardships and learning from traumatic experiences to contribute to a better future typical for World War II museums as well as pre-2011 disaster memorial museums in Japan. An exceptional influence can be attributed to DRI in Kobe, which established several features that became models for subsequent disaster meorial museums: the history behind the disaster, including data, records and peoples’ stories; scientific explanations of natural hazard mechanisms and predictions; personal actions that can be taken to prepare for disasters; and the option to talk to survivors at the facility.

A sharp difference regarding the framing of memories of 3.11 compared to previous disasters is related to the scale and variety of damage and experiences of 3.11 – a compound disaster including an M9 mega-earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster, multiple affected municipalities across several prefectures, and long-term impacts. Unlike after previous disasters, there was strong commitment supported by a large available budget, leveraged at multiple levels of government for the preservation and passing on of disaster memories. Memorialized to a greater extent than any previous natural hazard in Japan, more than a hundred tsunami marker plates, exhibitions and museums have been built, with a focus on disaster risk reduction (bōsai) following the statement of the Reconstruction Design Council (Citation2011). The large number of new disaster memorial facilities and the vast area affected by the disaster led to several new challenges for the exhibitions in the 17 museums analyzed in this research. Although almost all disaster memorial museums framed their presentations in terms of disaster mitigation, they did so with a local focus: Prefectural museums present an overview on what happened in their prefecture; municipal museums on their city; and disaster heritage sites focus on their specific building, adding information about the recovery process of their city and region.

Yet, we argue that this localized framing, compounded by a traditional disaster mitigation approach that rigidly separates “man-made” (jinsai) from “natural” disasters (shizen saigai), reinforces the idea of the nuclear disaster being an outlier event in Japan’s long history of disasters. This is compounded by the fact that issues of responsibility are mostly unaddressed in 3.11 disaster memorial museums, leading to the nuclear disaster not being addressed in most of the public 3.11 disaster memorial museums; despite their mission statements, lessons learned are not clearly told in the museums that focus on the nuclear power plant accident. A possible solution would be a memorial museum on a national level. However, with political and social implications connected to the nuclear disaster and the national government holding on to nuclear power, it is unlikely that lessons learned from the Fukushima nuclear disaster will be addressed in a similar way as it has occurred with the tsunami and earthquake, perpetuating the artificial division between man-made disasters and natural hazards aspects of 3.11 in cultural memory.

Compared to other museums and exhibitions on traumatic events and negative heritage, disaster memorial museums may receive less attention because of the assumption that – in contrast to natural hazards – “man-made” disasters are connected to responsibilities and therefore their representations reflect political statements. Yet as we argued in this paper, representations, especially at public disaster memorial museums, have social and political meaning as well, especially when the foremost goal of these facilities is disaster risk reduction. Future research is still needed to address questions such as by and for whom are what kind of lessons told at these museums? To fully understand the actual impact of these museums on collective and cultural memory it will be necessary to investigate how visitors perceive these exhibits and what they learn from the “lessons” presented. We therefore hope that this research may lead to future explorations on cultural and collective memory of 3.11 and contribute to the development of more diverse narratives on 3.11 that may go beyond simple “lessons learned.”

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Julia Gerster

Julia Gerster is an Assistant Professor at the Disaster Digital Archive at the International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS) at Tohoku University. She received her PhD in Japanese studies with a disciplinary focus in social anthropology at Freie Universität Berlin in 2019. Her main research interests include the dynamics of social relations after disasters, community building, cultural and collective memory of disasters, and the handling of negative heritage.

Elizabeth Maly

Elizabeth Maly is an Associate Professor at the International Research Institute of Disaster Science, Tohoku University, in Sendai Japan. With the theme of people-centered housing recovery, her research interests are community-based housing recovery and provision methods of transitional and permanent housing within the reconstruction processes–including policy, process and housing form–that support successful life recovery for disaster-affected people. Past and current research focuses on the experiences of people affected by disaster, and the roles of government and NGOs in the processes of housing reconstruction and resettlement after disasters in the U.S.A, Indonesia, Philippines, and Japan.

Notes

1 Highlighted by the authors.

2 The 16 public disaster museums that existed at the time of writing and the Commutan, which is a public science museum featuring the first permanent exhibition on the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster.

3 Minamata disease is caused by mercury poisoning and was first discovered in 1956 in Minamata city after a factory owned by the Chisso Corporation released wastewater containing mercury sulfate into the sea.

4 The translations of shinsai ikō range from disaster remains, tsunami ruins to earthquake heritage. The literal translation means “earthquake disaster remains. We translate the term as “disaster heritage”, as most shinsai ikō show traces of the tsunami rather than earthquake damage, and buildings from within the exclusion zone in Fukushima Prefecture might be included in the future.

5 Therefore, this list neither includes disaster heritage sites without an exhibition at the time of writing, such as the Taro Kanko Hotel or the Okawa Elementary School, nor facilities that feature exhibits on 3.11 within larger, different types of museums (i.e. the Rias Arc Art Museum)

6 Commutan is part of the Fukushima Prefectural Centre for Environmental Creation Communication building. As such, it aims to discuss energy and environmental issues and does not solely focus on the nuclear disaster.

7 One characteristic of this region is the history of municipal mergers, which combined smaller towns. Current municipal boundaries often include multiple areas with their own strong community identity.

8 More school buildings will be opened to the public as disaster heritage sites, for instance in Ishinomaki City (Miyagi Prefecture).

9 System for prediction of environmental emergency dose information.

10 In fact, the only museum that addresses questions of responsibility is the Decommissioning Archive Center operated by TEPCO. However, responsibilities and lessons learned are expressed in terms of becoming a better and safer company to continue their mission of delivering energy.

References

- Abt, Jeffrey. 2011. “The Origins of the Public Museum.” In A Companion to Museum Studies, edited by Sharon Macdonald, 115–134. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Asahi Shimbun. 2020. “Denshō-kan Goribu No Tokutei Dantai No Hihan Kinshi, Minamata Nagasaki Wa. [Prohibition of Criticism of Specific Groups in the Disaster Memorial Museum, What about Minamata and Nagasaki?].“

- Asahi Shimbun. 2021. “Fukushima Genpatsu PR Kanban, Hissori Jitsubutsu Repurika Ni Denshō-kan `rekka No Osore’ [Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant PR Signboard, Real.“ replica to the disaster memorial museum “fear of deterioration”]

- Assmann, Jan, and John Czaplicka. 1995. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique 65 (65): 125–133. doi:10.2307/488538.

- Benavides, Hugo O. 2009. “Narratives of Power, the Power of Narratives. The Failing Foundational Narrative of the Ecuadorian Nation”. In Contested Histories in Public Space: Memory, Race, and Nation, edited by Daniel Walkowitz and Lisa Maya Knauer, 178–196. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- Boret, Sébastien Penmellen and Akihiro Shibayama. 2017. “The Roles of Monuments for the Dead during the Aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 29, 1–8.

- Centre for Environmental Creation. 2019. Centre for Environmental Creation - Aiming for Environmental Recovery and Creation in Fukushima. Brochure.

- Crane, Susan A. 2011. “The Conundrum of Memory: Time, Memory, and Museums.” In A Companion to Museum Studies, edited by Sharon Macdonald, 98–109. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Densho Road Promotion Organization. 11 March 2021. “Densho Road.” https://www.311densho.or.jp/denshoroad/index.html?no=2

- Dombrowsky, Wolf R. 1998. “Again and Again: Is a Disaster What We Call a ‘Disaster’?” In What Is a Disaster? Perspectives on the Question, edited by Enrico L. Quarantelli, 3–12. London: Routledge.

- Dubin, Steven C. 1999. Displays of Power. Controversy in the American Museum from the Enola Gay to Sensation. New York: New York University Press.

- Duncan, Carol. 1995. Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums. London: Routledge.

- Fallows, James. 2014. “Stop Talking about Yasukuni; the Real Problem Is Yūshūkan’: Why a Museum Matters More than a Shrine.” The Atlantic, 2 January 2014.

- FIPO, The Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum. 2021. “Genshiryoku Kōhō No Hyōgo Moji Paneru No Tenji Ni Tsuite.” [ About the exhibition of the slogan panel of nuclear power public relations] https://www.fipo.or.jp/lore/archives/2430.22.10.201

- Fulco, Flavia. 2017. “Kataribe: A Keyword to Recovery.” Practice of Storytelling in Post-Disaster Japan. Japan Insights 1–28.

- Fulco, Flavia. 2021. “Kataribe-Storytelling: Building Community Resilience Through Personal Narratives And Local Knowledge.” Presentation at the 17th World Conference of Earthquake Engineering, 28 September 2021; Sendai, Japan.

- Gerster, Julia. 2019. “Hierarchies of Affectedness: Kizuna, Perceptions of Loss, and Social Dynamics in Post-3.11 Japan.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 41 (6): 101304. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101304.

- Gerster, Julia. 2021. “Post-disaster Tourism and the Recovery of the Tohoku Region.” In Reiher, Cornelia. Urban-rural migration and rural revitalization in Japan. Blog. Available at: https://userblogs.fu-berlin.de/urban-rural-migration-japan/2021/11/26/guest-contribution-post-disaster-tourism-and-the-recovery-of-the-tohoku-region/

- Gerster-Damerow, Julia. 2019. The Ambiguity of Kizuna: The Dynamics of Social Ties and the Role of Local Culture in Community Building in Post-3.11 Japan. Dissertation. Freie Universität Berlin.

- Gerster, Julia, Sebastien Boret, and Akihiro Shibayama. 2021. “Out of the Dark: The Challenges of Branding Post-Disaster Tourism Ten Years after the Great East Japan Earthquake.” EATSJ -Euro-Asia Tourism Studies Journal 2: 1–25.

- Gerster, Julia, and Flavia Fulco. forthcoming. “Framing Negative Heritage in Disaster Risk Education: School Memorials after 3.11.” In Heritage, Contested Sites, and Bordered Memories, edited by Ted Boyle. East and West: Culture, Diplomacy and Interactions Series. London: Brill.

- Gluck, Carol. 1990. “The Idea of Showa.” Daedalus 119 (3): 1–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20025314

- Goto, Shinobu. 2019. “Fukushima Dai’ichi Genpatsu Jiko No Kyōkun Wo Tsutaeru Shisetsu Naiyō to Kyōiku Kōka No Bunseki [Analysis of Exhibits and Educatioal Effects of the Memorial Museums on Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident].” JSPS Report.

- Goto, Shinobu. 2021. Genpatsu Jiko Wo Do Tsutaeruka. Cherunobiri to Fukushima. [How to Narrate Nuclear Accidents? Chernobyl and Fukushima]. Presentation. Online.

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1980. The Collective Memory. New York: Harper & Row.

- Hayashi, Isao. 2016. “Museums as Hubs for Disaster Recovery and Rebuilding Communities.” In New Horizons for Asian Museums and Museology, edited by N. Sonoda, 165–176. Singapore: Springer.

- Hood, Christopher P. 2012. Dealing with Disaster in Japan. Responses to the Flight JL123 Crash. London and New York: Routledge.

- Kato, Kumi. 2018. “Debating Sustainability in Tourism Development: Resilience, Traditional Knowledge and Community: A Post-disaster Perspective.” Tourism Planning &Development 15 (1): 55–67. doi:10.1080/21568316.2017.1312508.

- Kawasaki, Kota. 2021. “Fukushima Genpatsu Jiko Kara 10 Nen Go No Fukushima Fukkō No Jittai to Kadai [The Status and Problems in Fukushima Prefecture ten Years after the Fukushima Nuclear Accident.” Nihon Keikaku Gyōsei Gakkai 44 (3): 27–32.

- Landsberg, Allison. 2007. “‘Response’, Rethinking History.” The Journal of Theory and Practice 11 (4): 627–629.

- Littlejohn, Andrew. 2020. “Museums of Themselves: Disaster, Heritage, and Disaster Heritage in Tohoku.” Japan Forum 33 (4): 1–21.

- Maly, Elizabeth, and Mariko Yamazaki. 2021. “Disaster Museums in Japan: Telling the Stories of Disasters before and after 3.11.” Journal of Disaster Research 16 (2): 146–161. doi:10.20965/jdr.2021.p0146.

- Martini, Anna, and Dorina Maria Buda. 2019. “Analysing Affects and Emotions in Tourist e-mail Interviews: A Case in post-disaster Tohoku, Japan.” Current Issues in Tourism 22 (19): 19. doi:10.1080/13683500.2018.1511693.

- Martini, Anna, and Minca Claudio. 2018. “Constructing Affective (Dark) Tourism Encounters; Rikuzentakata after the 2011 Great Eastern Japan Disaster.” Social and Cultural Geographies 22 (1): 1–17.

- Arnold-de Simine, Silke. 2013. Mediating Memory in the Museum: Trauma, Empathy, Nostalgia. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Meskell, Lynn. 2002. “Negative Heritage and past Mastering in Archaeology.” Anthropological Quarterly 75 (3): 557–574. doi:10.1353/anq.2002.0050.

- Mignon, Piotr, and Edyta Pijet-Migoń. 2019. “Natural Disasters, Geotourism, and Geo-interpretation.” Geoheritage 11 (2): 629–640. doi:10.1007/s12371-018-0316-x.

- Mirai Support. 2020. The 2019 Report on Disaster Memorial Activities. 3.11 Mirai Support. 3.11 Future Support Association. (In Japanese).

- Nagamatsu, Shingo, Yoshinobu Fukasawa, and Ikuo Kobayashi. 2021. “Why Does Disaster Storytelling Matter for a Resilient Society?” Journal of Disaster Research 16 (2): 127–134. doi:10.20965/jdr.2021.p0127.

- Naono, Aikiko. 2005. ““Hiroshima” as a Contested Memorial Site: Analysis of the Making of a New Exhibit at the Hiroshima Peace Museum.” Hiroshima Journal of International Studies 11: 228–244.

- Ono, Yuichi, Marlene Murray, Makoto Sakamoto, Hiroshi Sato, Pornthum Thumwimol, Vipakorn Thumwimol, and Ratchaneekorn Thongthip. 2021. “The Role of Museums in Telling Live Lessons.” Journal of Disaster Research 16 (2): 135–140. doi:10.20965/jdr.2021.p0135.

- Perry, Rondald. 2018 (2007). “Defining Disaster: An Evolving Concept.” In Handbook of Disaster Research, edited by Havidan Rodriguez, William Donner, and Joseph E. Trainor, 3–22. Second ed. Madison: Springer.

- Quarantelli, Enrico L. ed. 1998. “Introduction. The Basic Question, Its Importance, and How It Is Addressed in This Volume.” What Is a Disaster? Perspectives on the Question,XII–XVIII. London: Routledge.

- Reconstruction Design Council. 2011. “The Seven Principles for the Reconstruction Framework.” https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/fukkou/#08

- Rigney, Ann. 2016. “Cultural Memory Studies. Mediation, Narrative, and the Aesthetic.” In Routledge International Handbook of Memory Studies, edited by Lisa Tota and Trever Hagen, 65–76. New York: Routledge.

- Sakaguchi, Nao. 2019. Sanriku kaigan gyogyō shūraku no seikatsu keiken to shinsai iko - Iwate-ken Otsuchi-chō no jirei” [Experiences and Disaster Remains in fishing villages in coastal Sanriku areas. The case of Otsuchi in Iwate Prefecture]. Dissertation, Tohoku University.

- Sakaguchi, Nao. 2021. “Memories and Conflicts of Disaster Victims: Why They Wish to Dismantle Disaster Remains.” Journal of Disaster Research 16 (2): 182–193. doi:10.20965/jdr.2021.p0182.

- Sato, Shosuke, and Fumihiko Imamura. 2018. “Kako No Saigai Taiō No Keiken Ha Keishō Sareteiru No Ka – Ikasareta No Ka? Higashi Nihon Daishinsai de Taiō Shita Miyagiken Shokuin Wo Taishō Shita Shitsuteki Chōsa Kekka to Teian [Were the Experiences of past Disasters Passed on – Were They Used? Results and Implications from a Qualitative Survey with Miyagi Prefecture Staff Who Were Involved in the Disaster Response].” Chiiki Anzen Gakkai Ronbunshū 33: 105–114.

- Sharpley, Richard, and Kumi Kato, eds. 2021. “Confronting Difficult Pasts: The Case of ‘Kamikaze’ Tourism.” In Tourism Development in Japan. Themes, Issues and Challenges,179–199. New York: Routledge.

- Takakura, Hiroki. 2015. “Tenji Wo Suru Jinruigaku [Anthropology on Display].” In Tenji Suru Jinruigaku - Nihon to Ibunka Wo Tsunagu Taiwa [Anthropology on display - discussions connecting Japan and diverse cultures], edited by Hiroki Takakura, 1–20. Tokyo: Showa.

- Taylor, Bryan C. 2010. “Radioactive History. Rhetoric, Memory, and Place in the Post-Cold War Nuclear Museum.” In Places of Public Memory. The Rhetoric of Museums and Memorials, edited by Gregg Dickinson, Carole Blair, and Brian L. Ott, 57–86. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Tierney, Kathleen. 2019. Disasters. A Sociological Approach. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction. (UNDRR). 2022. “Disaster.” https://www.undrr.org/terminology/disaster

- Winter, Jay. 2006. “Notes on the Memory Boom: War, Remembrance and the Uses of the Past.” In Memory, Trauma and World Politics: Reflections on the Relationship between past and Present, edited by Bell Duncan, 54–73. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wu, Chuntao, Carolin Funck, and Yoshitsugu Hayashi. 2013. “The Impact of Host Community and Destination (Re)branding: A Case Study of Hiroshima.” International Journal of Tourism Research 16 (6). doi:10.1002/jtr.1946.

- Yokemoto, Masafumi, and Toshihiko Watanabe, eds. 2015. Genpatsu Saigai Wa Naze Fukintō Na Fukkō Wo Motarasu No Ka: Fukushima Jiko Kara ‘Ningen No Fukkō, Chiiki Saisei’ E [Why Do Nuclear Disasters Result in Unequal Reconstruction? from the Fukushima Accident to ‘Human Reconstruction and Regional Revitalization’]. Kyoto: Minerva Shobo.

- Yoneyama, Lisa. 1999. Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space, and the Dialectics of Memory (Twentieth-century Japan): Time, Space, and the Dialectics of Memory. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Yoshida, Takashi. 2007. “Revising the Past, Complicating the Future: The Yushukan War Museum in Modern Japanese History.” The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus 5 (12).

- Zwigenberg, Ran. 2012. “The Coming of a Second Sun”: The 1956 Atoms for Peace Exhibit in Hiroshima and Japan’s Embrace of Nuclear Power.” The Asia-Pacific Journal |Japan Focus 10 (6): 1–15.

- Zwigenberg, Ran. 2014. The Bright Flash of Peace: Hiroshima and the Rise of Global Memory Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.