Abstract

This article focuses on data workers in Shenzhen, who, since 2013, have been recruited to fill positions in the city’s Weaving the Net program (zhiwang gongcheng, 織網工程). The program, furthering both the expansion of city gridding management techniques and local experiments with China’s Social Credit system, is designed to generate a daily set of data to inform the city’s “Smart Brain”, and is a core way of managing the city’s “floating population”. In this article, we approach the grid management of Shenzhen and its connection with histories of Chinese social control through data workers themselves. We argue that data workers expand our understanding both the integration of human-technological assemblages into smart city initiatives and the labor of data generation for programs of state social control. Extending STS approaches to smart city infrastructure, we use the figure of the data worker to the present both familiar and distinctive characteristics of Chinese Smart City initiatives.

1 Introduction

In November 2020, a question appeared on Zhihu.com, China’s largest question and answer platform. “What is it like to be a data worker?” This post got 106,000 reads, and the answer with the most “likes” was posted by an anonymous data worker from Shenzhen. In their answer, this data worker described his daily routine like this:

Most of the work is to register population and housing information, also [I am] required to do many other community jobs. Grid data workers are asked to keep constant contacts with all the landlords, tenants, business owners, shop keepers, by WeChat. During COVID, we are also wearing PPEs, helping community tracing and recording, checking people’s temperatures, and even delivering food and medicines … Every morning, we would firstly arrive at the community office, take on uniforms (90% like police uniforms, except that we have a “grid data worker” badge on the uniform). Then there would be a group meeting with other team members. After that everyone goes to their own grid with the working mobile device, walking along buildings and stores, knockings doors and asking people questions.

The question and answer exchange reveal an emerging profession in China: the grid data worker (wangge xinxiyuan, 網格信息員). Unlike the phrase “data worker” used colloquially across emerging studies of data entry and administration (Holten Møller et al. Citation2020), the data worker here is enrolled in social and city management. Operating in a city divided, assigned to their own smaller grids (the size of which is based on calculations of geographic and demographic data) she or he works collecting data and inputting it into a mobile device. The grid data worker is a new profession in China, having grown and consolidated over the past few years. Marking this, in June 2020, the Chinese Central Government’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (renli ziyuan he shehui baozhang bu, 人力資源和社會保障部) formally listed the job of “city management grid data worker” as a new profession in China. A data worker’s official job description is as follows:

Use modern digital management technology to inspect, verify, report, and deal with public facilities, city environments, and social management issues. Collect, analyze, and dispose of relevant information.Footnote1

This Zhihu post and Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security’s new job definition together give us an initial picture of the data worker, a figure we argue provides analytical insight both into changing governance mechanisms in urban China, and the growing role of digital technologies within them. In this article, we aim to provide both the context for the introduction of the new job of data worker, and perspectives on specific everyday experiences of the role. We follow the anonymous Zhihu reply back to the city of Shenzhen, where, since 2013, data workers have been recruited under the city’s Weaving the Net project, in order to explore the imaginaries of data and sociotechnical labor that make up its composition. Drawing on policy documents, job advertisements, official communication channels and forum posts, we arrive at an analysis that places their emerging role at the intersection of three spheres of sociotechnical policy: experimental social management in the Chinese state, social credit policies and smart city initiatives. We view the figure of the data worker, the work they do and the data they generate, as a lens through which we can understand shifts in knowledge produced for the Chinese state by data workers.

To develop this argument, we provide first some background to the scheme the data workers are employed under: Shenzhen’s Weaving the Net Project. We focus particularly on the way the policy articulates the need for data to manage both migrant workers and housing. We then offer a theoretical synthesis that illuminates the context in which data workers emerge as a bridge between initiatives to manage “floating populations”, the generation of data for social credit systems, and Chinese smart city imaginaries and practices. As Hu (Citation2019) notes, Shenzhen has a “unique status” in the Chinese urban system, not only for its rapid growth but also the presence of technology companies: “[p]artly because of its status as a new planned city, the Shenzhen Government is proactive in embracing the smart city concept and branding it as a leading smart city in China” (Hu Citation2019: 6). Building on these intersections, we seek to show how the data workers in Shenzhen’s Weaving the Net scheme are both in continuity with China’s developing grid-based social managementFootnote2 policies (Lin Citation2013; Mittelstaedt Citation2021; Tang Citation2020) and integrated as part of smart city logics, encompassing in Shenzhen’s case, the management of people through housing. Following descriptions of the everyday life of data workers and the systems to which they connect, we take the reader into the project of Weaving the Net, following both data worker accounts and corporate narratives to provide a new perspective both on the management of migrant populations and the generation of Chinese smart cities.

2 Methods

We have built our analysis on four main kinds of material: official discourse, state public communications, tech company reports and websites, and informal social media used by grid workers themselves. This combination of methods allows us to explore the role, position and politics of data workers during the current global circumstances of COVID-19, when field research itself is neither feasible nor responsible. Our first source, official accounts, required the thorough review of national and local policy pertaining to Weaving the Net, legal documents describing the status of migrant workers and housing, as well as state media reports of grid data workers in Shenzhen. We reviewed the relevant policy documents of the social credit system and grid management issued by both the municipal and district level governments of Shenzhen in the past few years, analyzing the context into which data workers have been introduced to better understand the intersections of these various initiatives as envisioned in policy. Second, we also paid attention to Shenzhen government’ new methods of public communications during the pandemic: the channels in Chinese social media platforms including WeChat, the most widespread social media platform in China. Given the frequent interactions between grid data workers and community residents during the pandemic, it has been relevant to our study to review the Shenzhen government’s public account, created to specifically explain and promote what data workers are doing every day to the general public. Any WeChat users subscribed to that public account would receive daily updates, what Jiang and Fu have called a “continuation and extension of E.gov and Gov Weibo with more mobile and personalized interactions with government entities” (Jiang and Fu Citation2018: 383, see also Neagli Citation2021). These digital mediums provide us with a generative approach for data collection under pandemic conditions.

Third, given that Shenzhen is one of the biggest high-tech hubs in China, the construction of Weaving the Net Project has involved many local high-tech companies. Reports of their involvement can be found in local news reports and government papers. Therefore, part of our data is also from the companies themselves. By gathering and analyzing different companies’ websites and reports, we have explored the stories and languages they use to describe their participation in the Smart City in Shenzhen. This allows us insight into the ways that they have collaborated with the municipal and district government, and in particular, how they think of the grid data workers within the broader system. We maintain a critical position on this “corporate story-telling” (Söderström, Paasche, and Klauser Citation2014) done by companies, attending as much to the imaginaries in play as the reported practices.

Finally, in order to obtain a view of grid data workers in Shenzhen that comes neither from state sources nor company narratives, we have sought ways of listening to the voices from the data workers themselves. As Shenzhen is one of the first cities to recruit such a big number of “professional” data workers in the country, there have been many online discussions of people sharing their personal experiences data work. China’s biggest search engine, Baidu.com, hosts discussion forums for grid data workers, each accruing thousands of posts. The majority describe data work in Shenzhen. We have used these discussions among data workers themselves to produce a composite understanding of personal experiences. Whether presented positively or otherwise, these snapshots offer insight into the way that data workers’ family backgrounds, hopes for career development in a rapidly changing society shape experiences of and perspectives on the role. Some users share very specific personal and job information (e.g. the district or community they were working at) online, and following the Association of Internet Researchers guidelines (AOIR Citation2019), we have chosen to anonymize all the information that may reveal their real-personal identities, especially the information about their work stations and hometowns.Footnote3 Though the discussions we found are posted on public Chinese forums, with no log-in required to read them, we still consider the context specificity of this informal, user-generated content (AOIR Citation2012, Citation2019) building on Nissenbaum’s contextual integrity (2010). Treating social media as ethnographic sites in China means considering a range of issues, from computational and state censorship (Yang and Wu Citation2018) to self-censorship (Huang Citation2015), and the production a “China” on the internet that is “only a title slide of its multilayered, complex reality” (Wang and Liu Citation2021: 3). As a result, these data are presented in conversation with the other three types, as one part of understanding the figure of the data worker in Shenzhen.

3 Positioning Shenzhen’s Weaving the Net Scheme

Shenzhen, located in southern China in the Pearl River estuary in Guangdong province, appears in ethnographic accounts as a city of transformation and change. Established as one of China’s first special economic zones in 1980, its growth, its fostering of technological innovation (Lindtner Citation2020) and its experimentality (Du Citation2020) have fueled the imaginations of both academics and journalists of global urbanism (O’Donnell, Wong, and Bach Citation2017). Given this history of economic and infrastructural growth, scholarship and policy alike have focused on the management both of its growing population and the urban environment needed to house and feed them (Bach Citation2010; Ai Citation2014).

As a result of its growth and industrial success, Shenzhen is known as a city with one of China’s highest proportions of migrant workers. In 2019, of its total of 22 million, only 4.9 million had full residential registration, or a hukou (戶口) in Chinese; 13 million were classified as permanent residents (changzhu renkou, 常住人口), meaning that they were registered as staying for more than 6 months and thus able to access some of the local social benefits. Another 10–12 million were called as “floating people” (liudong renkou, 流動人口), not registered with any governmental bodies in Shenzhen.Footnote4 The category of “floating population” is a category of migrant worker, created “at a particular time in recent Chinese history and has been employed by the state as a unified social category” for the purposes of regulation and monitoring, anthropologist Li Zhang has argued (Citation2001: 46). Yet among migrants in China, the floating population remains one of the most difficult groups to define and measure (Goodkind and West Citation2002: 2237). They are frequently represented as “a monolithic and formless entity consisting of unregulated, dangerous laborers who require stringent social control and surveillance” (Zhang Citation2001: 33).

The governance of hundreds of millions of floating people has for decades been of concern to Chinese authorities in maintaining social stability. Since the 1950s, the household registration hukou (戶口) system has been a crucial institution stringently managing different groups of people including rural migrants to cities (Chan Citation1994, Citation2009; Naughton Citation2007). Because the hukou system largely constrains rural migrants’ access to urban welfare, they become urban sojourners, secondary citizens who lack urban social connections and therefore cannot claim public housing and other local welfare support (Chan Citation1994; Solinger Citation1999; Zhang Citation2001). Since the post 1978 economic and agricultural reforms, the state has been decentralizing the control of migrants through continuous hukou reform (Chan Citation2009; Fan Citation2008; Wang Citation2005).

Against this backdrop, in 2013, the central committee of the CCP passed a new document for the management of migrant workers and social management called “Decision on Some Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform” (see also He Citation2016).Footnote5 In this document, the ruling party states to “improve the methods of social governance”:

We will persist in governing from the source, dealing with both the symptoms and root causes … taking grid management and socialized service as our direction, improving grass-roots level comprehensive service platforms, reflecting and coordinating in a timely manner the interests and appeals of the people from all walks of life and at all levels.Footnote6

First, as detailed in the Introduction to Weaving the Net documentation, the local government explicitly identified that the project was an initiative to build on grid management to better implement its policy towards the floating population: managing people through housing, managing people and housing together (yifang guanren, renfang gongguan, 以房管人,人房共管).Footnote7 While the policy of “managing people through housing” had been initiated in Shenzhen in 2003, the Weaving the Net project made way for the local government to build up a digital, holistic system of locating, identifying, and managing the city’s extensive floating population in a more efficient way.Footnote8 Grids are a statistically driven geo-coordination technique for creating data-rich spatial units, increasingly studied across fields for the way they reshape census practices (Deichmann, Balk, and Yetman Citation2001; Grommé and Ruppert Citation2019), produce new spatialities (Kitchin and Dodge Citation2011; Westerveld and Knowles Citation2020), and, in China, reformulate grass-roots surveillance and service-provision governance (Gang Citation2018; Lin Citation2013; Mittelstaedt Citation2021; Tang Citation2019). While a comparison across national implementations of urban gridding is beyond our scope here, the narrative around organizing data collection into grids represents “modernization”, the increased potential for the reuse of population data (Grommé and Ruppert Citation2019: 251) and a key site through which “technological and political rationalities intersect and mutually constitute one another” (Lin Citation2013: 908; see also Ruppert and Scheel Citation2021). Through Weaving the Net, the densely populated city of Shenzhen was divided into 18,000 grids,Footnote9 with each grid assigned a community grid data worker to collect, document, and report various types of data on a daily basis. Each grid covers 300–500 apartments and/or 1000 people, with small businesses (e.g. restaurants, grocery stores) nearby. Then each building was given a unique identification number and documented in a city-wide data platform.Footnote10

Second, Weaving the Net prompted the large-scale recruitment of grid data workers. Their work, inspecting the streets and asking questions in homes on a daily basis made the merging of grid governance and floating population management possible. Through its emphasis on documentation, digital reporting, project promoting, and problem solving, almost every part of Weaving the Net project is based on a large amount of coordinating work between the human and non-human digital devices (Ruppert Citation2009), ranking and reporting each building, and dealing with the dynamics within each “grid”. Not surprisingly, in 2020 Shenzhen’s Weaving the Net project has created one of the biggest teams of grid data workers – 16,000 recruited through various government agencies – in the country.Footnote11 As we will show, in addition to producing data for Weaving the Net, data workers thus become enrolled in wider “smart city” projects of sensing and managing city life. In contrast with popular narratives of smart city instrumentation and automation (Madsen Citation2018; Shelton, Zook, and Wiig Citation2015), the data workers are here made part of the way the city is newly known. We approach their work against the backdrop of interlocking policies with longstanding priorities in Chinese population governance described above, considering first who data workers are and what they do, followed by how they are seen from the perspective of smart city initiatives. First however, we provide an overview of how we have come to understand their work and position.

4 Who are Data Workers?

“Data work” is a growing field, the term being used variously across sectors to indicate the oft overlooked labor carried out by scientific assistants who organize data sets, clean files and prepare data for analysis (Walford Citation2021). Data workers, as scholars in STS adjacent fields like Computer Supported Collaborative Work (CSCW) have found, also seek “contextualize” data as they work to make it administratively meaningful (Holten Møller et al. Citation2020). In the context of the production of data for nation states, STS researchers have been attending to how data scientists and statisticians are creating new ways of knowing, and hierarchies of expertise (Grommé, Ruppert, and Cakici Citation2018).

The data workers of Shenzhen, and the new labor category in China more generally are, at this point, integrated into city (rather than national) data production. Their role is increasingly recognized. In addition to the new official job category, they have, as seen in the opening example, risen to prominence across China COVID-19 Pandemic. As data workers donned PPEs, and, in the words of the opening poster, “assisted with community tracing and recording, checking people’s temperatures, and even delivering food and medicines”, they became portrayed in Chinese media as part of local and national strategies against the virus (Liu Citation2021). Data workers helped to manage quarantine, became key vectors of track & trace programs, even coordinated food delivery in their grid communities (Wan Citation2021). Their different roles situate them between knowledge work, social work, and surveillance work, distinctions we suggest, blurred by the nature of data’s re-usability. But what are the official demands of the job? By looking at a recent job advertisement (below) issued by the Nanshan District government, we can see one version what a data worker looks like in Shenzhen:Footnote12

Shenzhen Nanshan District is hiring 340 people 10/09/2020

Entry requirement for the post:

(1) Essential: bachelor’s degree or above, under the age of 35

(2) Desirable: China Communist Party members, relevant working experiences at the grassroots level, social work major and/or having social work qualifications; workers with extraordinary performances in COVID-19 Prevention. The requirements can be adjusted to those with a college diploma and 40 years old, but these applicants cannot take more than 10% of the whole working team.

In Shenzhen, for example, a civil servant job would grant a local hukou and includes an annual salary with at least 200 thousand yuan (30 thousand USD), extra allowances for helping house buying, better access to medical treatments, and quality public education for their children.Footnote14 But the grid data workers are just offered a fixed-term contract (normally one to three years) by an outsourcing company. While data workers are doing a government job at the community level, they are not recognized as a government worker on paper. Data workers’ tasks may give people an idea of what a junior civil servant position could be like, as the tasks are similar, but a data worker cannot be promoted into the government apparatus. Their employment rests with the outsourcing companies,Footnote15 whether private or state-owned, meaning that the local government branches have no further responsibilities towards them. To become a data worker, applicants first apply online, finish a written test, and then attend face-to-face interviews with relevant government bodies. Salaries span 4000–6000 yuan (615-923 USD) per month after tax, with very few other benefits. As Shenzhen is one of the most expensive cities in China, the average monthly salary in the city has reached 10,453 yuan in 2020 (1060 USD),Footnote16 and the data workers just earn half of this average.

As a result of these working conditions, most of the data workers actively sharing their working experiences online are young people. The prevailing narrative is of a person who has just graduated from the university and is struggling to find their first job. Most of the job applicants are not (yet) qualified to get a civil servant job but becoming a data worker provides them with quasi-governmental working experiences. On online discussion forums on Baidu and Zhihu.com, posts frequently address the question of how to change career from being a data worker to other government jobs; whether it is a good job for recent graduates; how to settle down in city with such little pay; and how to cope with complex migrant communities in the city village and heavy workload.

Being a data worker represents a range of things to those who undertake it, but a prevailing theme in posts is the challenge of the role. One Shenzhen data worker complained that doing his/her job was difficult on a number of levels:

No one in the grid would report voluntarily, so I have to walk around every day. The supervisor will check our work every month, anyone who has three people unreported or more would be fined 300 yuan (50 USD). I need to work really hard to get the pay (as signed on my contract).

While there do appear to be cases where data workers finally changed to a more successful career by passing the civil servant exam, they are rare. In fact, in a “hot post” asking, “whether there are possibilities of promoting to the street level government or even higher”, an answer from an experienced data worker received the most “likes”:

I have done this job since I finished my college diploma, it is eight years now. To be honest, I feel like I am just getting a job for food and waiting to die … I had been suggested by my families to work in companies to get a higher payment, but I did not dare to give up this stable job, with the hope that I may have chances to be a civil servant one day. But now, I have not passed the civil servant exam yet, so no chances for promotion. As I have stayed in the street for such a long time, it is really difficult to change into other sectors … this job is not suitable for any men with skills or breadwinners who need to feed the whole family, but it is a perfect job for married women between 20-30s who need to take care of their children …

4.1 Collecting Data

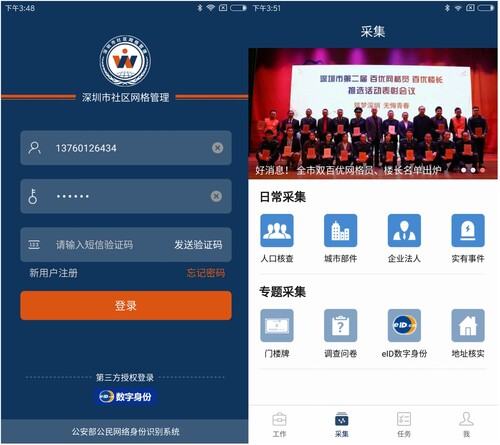

Whatever their hopes for the job, by knocking people’s doors, the data that data workers collect almost cover every aspect of people’s daily life, from the personal ID, biometrics information, household information, occupation, contacts, ethnicity, the building they live, the companies they work for, the contracts they have signed with landlords, to the vegetable stands nearby and potential security risks in the community. As we saw in the opening post from Baidu.com, while “most of the work is to register population and housing information […] Grid data workers are asked to keep constant contacts with all the landlords, tenants, business owners, shop keepers, by WeChat.” The job-issued mobile phone is a key part of the data collection work, and below show what data collection application on a mobile device looks like. Used to collect data in each worker’s grid, inputting the data becomes a daily routine. In , we see the login screen for the data worker who must use their phone number (as a form of ID) and password to access the collection screen. In , we see the “Collection” screen. It is headed with an image of the year’s best grid workers receiving their certificates, the second of a now annual competition. Below the photo are four icons in dark blue used for daily data collection: left to right these are population check, city facilities, companies and incidents. The row below concerns specific theme collection, with the light blue icons detailing collection on: buildings, survey, digital ID and confirmation of address. The Collection screen is one of four used by a data worker, as seen across the bottom of the app (Home, Collection, Tasks, Me).

Figure 1 and 2. Left: the login page for the data workers. Right: the data items they need to collect.

Figure 3. The data workers (in black) were collecting personal data (in green) with their device in Shenzhen.

What data workers are tasked with varies nationally. Studies of their role (and the degree of continuity they represent with prior forms of social management in China) are just beginning, heightened by the significance of data workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. In his recent review, China Studies scholar Jean Christopher Mittelstaedt collated comparative tables of data worker responsibilities across towns in six provinces, arguing that the variability in implementation of grid workFootnote17 is the result of a tension between policies that, over the years, have emphasized top-down management of people at some points, and service provision and mass participation at others (Mittelstaedt Citation2021: 6). This distinction between service provision and grass-roots monitoring is important, since in Weaving the Net, “managing people through housing” in Shenzhen, is both intended as a form of management, yet is framed as part of service provision through interaction with residents. In Bao’an for example, Shenzhen’s district with the most floating people, data workers ranked rental houses based on a range of issues, including how accurately the landlords and tenants had reported their contracts and personal information from both sides. Data workers entered the buildings, documented the security facilities of the house, hygiene conditions, whether there are public security concerns, how cooperative they are with the grid data workers, and so forth. We now explore the implications of this detailed, everyday work against a backdrop of shifts towards grids (wangge, 網格) ().

4.2 From Housing to Grids

In 2014, a year after Weaving the Net was set in motion, the city’s overall Office of Floating People and Rental Housing was renamed as the new Community Gridding Management Office.Footnote18 This re-naming foregrounds the importance of grid management, a concept that organizes the heterogeneity of urban space and population. Given the scale of Shenzhen’s population, the ranking and/or scoring policies from the districts vary slightly in how they articulate the connection between housing and migrants. In general, however, the rental houses visited by data workers were scored or ranked in different ways, based on their security facilities, data reporting conditions, and types of contracts signed by the landlords and tenants.

This documentation is exemplary of how governments across China are increasingly involved in rental housing management (RHM), gradually changing their focus from managing people through access to traditional hukou to RHM. Urban planning scholars have noted this shift: Gong’s (Citation2016) ethnography in the city of Dongguan, Guangdong Province reveals how grid governance targets the floating people and operates in their communities in new ways.Footnote19 Rental Housing Management turns out to be a new approach for managing floating people at the community level, a “shift of political rationality in China’s urban planning” (Lin Citation2013: 916) in which “it is not the individual enterprise that is subject to surveillance; it is the environment it operates that is to be disciplined” (Tang Citation2000: 61). In Gong’s research, we can see the changing governance of the floating population in the past few years, which, through the combination of RHM and its underlying grid governance together, has restructured migrants’ communities in many Chinese cities.

The integration of “grid governance” as both city and social management – a practice that has seen significant growth since 2004 – connects with prior social management strategies of the Chinese state (Hoffman Citation2018; Mittelstaedt Citation2021). Prior to the Weaving the Net Project, communities in Shenzhen were governed directly by different Resident Committees (juweihui, 居委會, RCs), like other Chinese cities. Resident Committees, also called “the government next door” (Lumba Citation2014), have been functioning as intermediaries between the state and residents since the Maoist era, and were closely involved in management of the SARS outbreak (Bray Citation2008). Historically, Resident Committees were given various administrative and political tasks to do in the neighborhood, from implementing one-child policy, organizing safety patrols, to launching recreational activities (ibid.). Although scholars argue that the roles that RCs play are diminishing in urban China due to the rising of middle class and their gated, modern apartments or communities (Lee Citation2007; Tang Citation2020; Tomba Citation2014), it should also be noted that these community-level organizations are becoming increasingly important and complicated in floating population management in many big Chinese cities.

Given that most of the migrant workers, both in Shenzhen and in other cities, may not live in the gated middle-class communities, for a long time RC workers and their volunteers, were considered a still active “useful” socialist legacy in floating population communities (Xiang Citation2005; Zhang Citation2001, Citation2010). In Beijing, for example, a number of retired male and female local RC volunteers were mobilized during the 2008 Beijing Olympics to help city management in terms of community security and migrant control, reporting any possible risks in the neighborhood (Chen Citation2006; Tang Citation2020). The way they were mobilized shared features with the former system – it used telephone and paper, and there was no collaboration with high tech companies. But it signified a departure in another respect: a move towards the use of so-called “grid governance” (wanggehua zhili, 網格化治理).

Emphasized by President Xi and the central government since 2013, then widely used in many contexts, the concept of the grid appears in domains as distinct as city management, environmental protection, food security, hospital management and even national security (Wu Citation2015). “Grids” (wangge, 網格) divide street offices and residential communities according to their geographical and administrative boundaries, with each grid being assigned government personnel for all three levels (district, street offices and residential communities). In her work analyzing the histories of Chinese state security, Samantha Hoffman (Citation2017) takes synthetic approach to the relationship different policies. Connecting the social credit system, gridding management and the national security policies together, Hoffman argues that these projects should be understood as the overall process of introducing further technologies into what has been called as “social management” in China in the past decade.

Hoffman’s synthesis is arguably visible in Weaving the Net, where, through a grid governance approach to floating population management, data was further incorporated into social credit records for buildings and their owners. In Shenzhen’s westerly Bao’an district, discussed above, the rank of buildings generated by data workers would also be digitally documented in the local social credit system and attached with both the landlords and tenants’ personal credit records respectively. Tying these rankings to the social credit system meant that landlords and tenants with higher ranks would be given more priorities in their next contract leasing or house hunting process in the Bao’an District. Grid management does not just allow for the management of housing and people together, however. It also, as we explore further below, generates data that is being further integrated into initiatives under the Social Credit System.

In Shenzhen, then, two features of data workers stand out. In contrast with earlier modes of social management in China, Shenzhen’s data workers are new actors: they are neither volunteers – they are in paid employment – nor local residents. In Shenzhen, data workers are often also newcomers, anxiously looking for a job to start their career in the city. Unlike the retired RC volunteers in Beijing, grid data workers seem to represent a more “professionalized” way of governing urban communities. Second, the work of data workers in grid governance is highly digitalized. Digital technologies have been integrated into the initial design, implementation, and daily operation of the Weaving the Net project. As an extension of the local government, the Shenzhen data workers contribute significantly to surveilling the large population of migrant workers in the city. Instead of conversations over the washing line, the form taken by Resident Committee members, grid data workers are employed, uniformed, given mobile devices, their daily work is routinized, and more importantly, the grid system behind the workers links them with a bigger picture: the construction of Smart City programs in China.

5 Data from Data Workers

If data workers spend long days collecting data on their official smart phones, where does the data go? Meet the data worker portrayed from the perspective of the tech companies, who harvest, organize and analyze the data coming in from Shenzhen’s grids. In a promotional video created by Huawei,Footnote20 we meet a person in uniform called “community grid data worker” patrolling a vegetable stand in the street. This person, named “Little Xiao (小肖)” by the neighborhood, proudly described his job in the video:

We proactively walk to the people, collect data constantly, and serve them when needed … Many people do the same job as me, we report everything we do to a huge data center; our everyday job is interconnected with that new digital world … Footnote21

The “Smart Brain” is a Huawei branded concept for centralized smart city platforms, referenced elsewhere in Chinese language literature as the “brain and heart of a smart city, and also the core of the construction of a smart city platform” (Xi Citation2019: 159). Smart-city pilot projects have been expanded across the country by the Chinese central government since 2010, and around 500 cities are cooperating with information technology (IT) firms to improve their data collection, transportation, public administration, population control, and health service.Footnote22 Of course, cities’ “smart” initiatives intersect with existing priorities and technologies, whether these are prior policies about sensors, energy or transportation (Tang and Ho Citation2019) or reclaiming land to build green smart cities from the ground up (Joss and Molella Citation2013). The interests are locally shaped: as early as 2006, reports Lin, Shenzhen officials expressed interest in “layering other socio-economic data (e.g. real-estate data, micro-economic data, environmental protection data, and so on)on [an] urban-grid base” (Nanfang Daily, July 28, 2006) (Lin Citation2013: 913). The computational logics upon which grid mechanisms rely are easily packaged in the international language of the “smart city”, and as the political scientist Tang has documented, the story is that “grids transform smartness into wisdom” (Citation2020: 4).

Weaving the Net arose as an urban migration policy, and while not on the surface a smart city initiative, in choosing to “manage people through housing”, required considerable amounts of data. The project necessitated the creation of a database every building in Shenzhen, documenting more than 6,600,000 buildings of all types.Footnote23 From this database of buildings, further data was required on the people who lives in the houses, trade outside them, manage them. In contrast with smart city imaginaries that depend on computational vision and sensing, this is data not easily obtainable through smart city sensors and cameras alone. Seen from this perspective, the demand for a large group of data workers was created: as the last step of data collection and reporting, the data workers, whose main job is to interact with the community residents, become a part of the whole digital program. For technology companies, data workers are part of smart city development, slotting into a longer history of the integration of IT into city management. Since Geographic Information Systems (GIS) began to be integrated into city government in Shenzhen, it has provided the means to “govern and discipline urban environments on a larger scale” (Lin Citation2013: 906).

As Little Xiao goes about his work as a data worker, he is a highly visible (public) part of this larger scale infrastructure. However, when speaking to the viewer in the Huawei video, he describes himself in the company’s terms as the “nerve ending in connecting the Smart City”. Little Xiao’s “nerve ending” analogy borrows from Huawei’s conceptualization of the smart city as an “organic lifeform, which may, through collaboration between the brain, nervous systems and various organs of the body, continuously recognize and improve the physical world” (Huawei Citation2017). This organic lifeform remains predominantly technological: when discussing the need of “neural networks of smart cities” promotional material highlights technologies: “ultra-wideband network, cloud, big data, IoT” that will achieve “perception” (Huawei Citation2017).

STS has long taken a critical position relative to the language of “smartness” (Ross Citation1993) but has maintained its close attention to the different models of participation, governance and big tech collaboration that are emerging in smart city initiatives, critical of technocratic imperatives (Hartley Citation2020; Löfgren and Webster Citation2020). Analyses from urbanism are directly critical of the favor that smart city showers on “business-led technological solutions” (Grossi and Pianezzi Citation2017; Marvin et al Citation2015) while others critique the basis of thinking a city computationally at all (Mattern Citation2017, Citation2021). Within the Asia-Pacific region, studies of specific initiatives have shown the different possibilities and divergent paths of digital urbanism under local governments, and the specificity is important: there is no single smart city. The international narrative of the Chinese smart city is technological, as Laurent et al. put it for Singapore, the “infrastructural nature of smart urbanism … render[ing] embodied human work invisible” (Citation2021: 512). Across China, cities have installed a large number of street cameras, enabling government to not only document criminal activity but also track people’s mobility on a large scale (Curran and Smart Citation2021; Yang and Xu Citation2017). Returning to Gong’s (Citation2016) research in Dongguan, he also finds that a number of digital surveillance devices have been set up in every entrance of the rental houses, as part of a smart city project to enhance the efficiency of floating population management. However, data workers – people-phone assemblages– have an equally key role: as much as IoT sensing and video surveillance fit elements of Huawei’s “neural networks,” data workers themselves are usually doing the work at the “nerve endings”, knocking on doors, walking the streets, negotiating human relationships, smartphone in hand.

This is why data workers often appear in the stories created by small high-tech companies and government offices as they seek to create more standardized digital facilities, mobile devices and specific apps for “floating people management (liudong renkou guanli, 流動人口管理)”. A company named EiDlink (Jinlian Huitong, 金聯匯通) for example, has created an e-identity app as part of a Shenzhen eID + Floating Population Comprehensive Management Pilot (eID 2021). Instead of replacing contact with employees of the state, a marketing video on their company website shows how this application operates with the help of grid workers, who arrive at doors, smartphone in hand.Footnote24 A layered app, depending on the existing infrastructure of ID cards and QR codes, as well as the city’s extensive registration database and facial recognition, it is nonetheless the data worker who shows up, uniformed, at the door, to verify the identity of those inside using their smartphone.

5.1 Data Workers in the Chinese Smart City

In Shenzhen, the organic metaphor extends to the control room, the “Smart Brain” constructed by the Longgang District Government in Shenzhen. Huawei Headquarters is itself based in Longgang District, and the “Smart City Brain,” made most tangible in the huge digital screen (figure X below), embodies collaborations across the tech sector and with local government. The screen itself was created in 2017 by Absen, an LED display company, and claims to present more than 2000 types of “real-time” data collected from each street.Footnote25 What is notable about this vision of dashboard city life is that the data are collected both by data workers and digital devices ().

The public narrative of the “Smart Brain” is prominently found on Huawei’s website, where, in a short video a government official from the Longgang District Government proudly talks about its collaboration with Huawei in constructing the Smart BrainFootnote26:

With the help of Huawei, we [the Smart Brain] can get access to various information sources scattered among different government departments and control the city operation constantly. A more efficient emergency response, making the city management more visualized and intelligent.

These claims for the advantages of smart city life are familiar to scholars of smart cities, where technologies are foregrounded as the automators of efficiency. The video concludes with a short speech from the government official:

How to enhance the government's operating efficiency is a question that we have been always exploring. The arrival of digital time gives us the opportunity [to answer the question]. Now we are hand in hand with Huawei, embracing the digital time without the fear of transformation.Footnote27

5.2 Working with Data from Grids

Eden Medina’s historical analysis of Chile’s Project Cybersyn traces a computer project that was imagined as a way of managing Chile’s economy, complete with a real-time control room, wall of screens and continuous data (Medina Citation2011). As Hoffman notes, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the complex systems theory that informed Cybersyn was already in conversation with social management in China, which officials thinking about “how technology could be used to support social management … but it was only theory at this stage and not practice” (Citation2017: 71). Following the development of Weaving the Net begins to draw how grid management combines with digitalization to bring not only new kinds of information to local management but also imaginaries of the power of data.

Grid management lends itself to such projects through its provision of data: it can be re-used for a number of different ends. Some researchers, picking up Hoffman’s thread regard the use of technology in social management as part of a larger picture of strengthening state surveillance in China (Dai Citation2018). That is partly because the implementation of SCS and the changing floating population governance in many Chinese cities happen almost at the same time, using similar digital tools, and under the name of “Smart City”. This observation is shared by privacy legal scholars Yang and Xu who report that in March 2016, the vice president of Sesame Credit, Hu Tao, gave a speech claiming that “Technology plus credits are the future of the smart city” (Tech Citation2016). Scholars of SCS and grid governance have noted the significance of the vast data collection and sharing ambitions that are implied by the SCS and grid governance programs, because the Chinese government is purportedly collecting digital records on the social and financial behaviors of private citizens and organizations with the support of IT firms including Alibaba and Baidu (Chen and Anne Citation2017).

To see how data collected by data workers intersects simultaneously with the smart city and the Social Credit System (SCS), some history is necessary. The Social Credit System first appeared in official documents at the Sixteenth National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party held in 2002, within discussions on “improving the modern market system and macroeconomic adjustment”.Footnote28 Before the 2010s, SCS had been largely designed to regulate the market economy, help “reduce financial risks, improve financial stability,” and allow the government to better perform its responsibilities of “macroeconomic adjustment and market oversight”.Footnote29 The project was initially led by the National Development and Reform Commission and the People’s Bank of China at the national level.

However, since 2011, SCS has been expanded to include more social factors in response to a CPC decision to promote “socialist morality.” The “Decision on Deepening the Reform of the Cultural Regime,” issued that same year, designated four areas for improving trustworthiness and credibility: honesty in government affairs, commercial integrity, honesty in society, and judicial credibility. Currently, almost every province in China has started their own experiments with social credit system programs (Liu Citation2019). SCS in many places aims to create a joint reward and punishment mechanism through which individuals and companies with good credit records can receive benefits from the state while those with bad credit scores may receive state sanctions (Chen and Anne Citation2017).

At present, no coherent nation-wide system of social credit in China exists. Instead, there are multiple departmental and localized systems with different features and designs in different places. Thus, we can see the current SCS as a fragmented system, characterized by local experiments, contradictions and contestations (Ahmed Citation2018; Liu Citation2019; Zhang Citation2020). However, given the possibilities for sharing data across systems, and the emphasis on data collection. scholars across disciplines are examining the SCS from a broad surveillance and social management perspective. For instance, Liang (Citation2018) understand SCS as an undergoing infrastructure of social surveillance in China, comparing it with other more traditional surveillance mechanisms like hukou (household registration) and Dang’an (personal archives).

While hukou contains population registration information and is mainly used for migration control, Dang’an aims to archive personal information, including ID numbers, employment records, and education data, and is usually unavailable to individuals. Liang (Citation2018) then argues that with the development of new technologies, China’s surveillance assemblages have moved from the traditional Hukou and Dang’an to more sophisticated methods like CCTV, Internet censorship, and big data analytics (Creemers Citation2018). A series of initiatives, including SCS, have indicated that the government is rapidly upgrading digital information control mechanisms. Based on this research, some scholars have gone further to argue that the SCS is, or has the potential to be, an all-encompassing system (e.g. Chen and Anne Citation2017; Meissner and Wübbeke Citation2016). By introducing automated and real-time monitoring, the government is integrating previously separated surveillance platforms into “an internet of surveillance” and building “an all-encompassing system penetrating, controlling and shaping society” (Meissner and Wübbeke Citation2016: 52). Thus, the SCS is regarded as an extension of Dang’an. In addition to individuals, the SCS also aims to constantly monitor and rate the behavior of companies and other market actors (Meissner Citation2017).

At the same time as data workers become integrated into the project of knowing, creating the data that will serve an explicit project of efficiency, they database, online platforms, mobile devices, and street monitors are not tools any more, but they are the purposes too: by constructing the Smart Brain, they become the driving power of transforming the city. As they send their data to the Smart Brain, the data workers are imagined as part of part of the technology, making Weaving the Net a project of digitally recreating the city.

6 The Figure of the Data Worker

In a conference of January 2021, the central committee of Chinese Communist Party warmly praised the 4.5 million grid data workers’ contribution of combating the spread of COVID-19 across the country, for which they have been called as the “community gatekeepers” in doing the trace and tracking work.Footnote30 Data workers already do more than data collection in their jobs. In fact, as we have shown from the Shenzhen’s local government reports, grid data workers’ jobs have been expanded to cover a wide array of issues, given that they know the residents and businesses in their own grids better than other government workers. For instance, as we presented at the beginning of this paper, data workers have been asking to trace and track any travelers from abroad, regularly checking travelers’ self-quarantining situations at home, and delivering daily essentials for them (Wan Citation2021). At the same time, given the roll-out of COVID vaccinations in Shenzhen, data workers are mobilizing people in each grid of getting vaccinated, offering free rides for the elderly to the vaccination centers, and answering questions.

Though the basic job contents of data workers remain the same as data collection as well as “feeding” the smart city brain, what a data worker would do every day could vary according to the different local government agendas. In doing these jobs, the data workers are expected to be present and known in local communities, to be seen and to communicate about reporting information and work in the name of efficiency. The usefulness of data workers during the COVID-19 has been shown in doing “social management”, therefore we can confidently assume that there will be more and more grid data workers in different Chinese communities. Meanwhile, it remains to be seen how data workers as a new job description will develop in other cities beyond Shenzhen, particularly in cities of different scales, and with different technological actors. In this sense, Weaving the Net is a particularly local project.

As our analysis of the job adverts and online posts above highlighted, the large scale of recruitment of data workers in Shenzhen is also changing the politics of the local job market. When the data workers complained online, they noted the trivial, tedious jobs they do for data collection and community inspection. Here, in their work, we also have a contradiction about the smart city: the smart city construction involves a big number of “non-smart” manpower; and the large number of efforts in population control reveals that the floating people may be too fluid to be controlled. What is more striking from the job adverts and discussions is that, as a new profession working in the communities, the requirements of becoming a data worker may have nothing to do with relevant working experiences or knowledge about local communities or residents.

Rather, the job applicants are much evaluated by how efficiently they can be the “nerve end” of a grand digitization project: the Smart City. This means that only the young, well educated people (to handle the digital devices), and those who can accept a poorly paid job (mostly women) can join this new profession. In fact, data workers are not the only group in Shenzhen that are recruited to do the government job but ended up with an outsourcing company and unfair payments. Anthropologist Mun Young Cho’s ethnographic research on the social work practices in Shenzhen’s Foxconn industrial zone reveals how neoliberal-style outsourcing has created precarious labor conditions for frontline social workers. Her research finds that most of the government-commissioned social work positions in the factories were filled up with migrant youth from the countryside, reproducing and perpetuating China’s rural–urban divide (Citation2017). These social workers, mostly young female graduates and normally seen as part of the “white collar class” in sharing the state responsibilities for providing social welfare, may just find themselves ending up like factory workers they were working for. Our research on data workers echoes with Cho’s findings of social inequalities and outsourcing jobs in Shenzhen. Although Weaving the Net project has involved a lot of high technologies, it may end up with creating numerous poorly paid, gendered jobs, which has strengthened the existing social inequalities rather than reduced them in the city. As part of the floating people themselves in the city of Shenzhen, data workers as a new profession reveals the other side of the “Smart City” in China’s context: it is not that smart, intelligent, or digital as we might have imagined. Smart urbanism should be viewed through an infrastructural lens, making the human work of smartness visible (Willems and Graham Citation2019).

Finally, Shenzhen’s new policies that use grids as the basis for both social credit, and smart city initiatives are also happening in other Chinese cities. In Guangzhou, a city which is two hours’ drive from Shenzhen, the municipal government has also divided the city into grids and registered all the rental houses. Like Shenzhen, data workers rank the buildings with different stars. In districts with a high proportion of floating population, these ranking stars are directly calculated as social credit scores. These scores then largely decide the social benefits and/or punishments that both the tenants and landlords can enjoy in the city. In one Guangzhou’s eleven districts, Baiyun District,Footnote31 the rental houses are marked with four hierarchical colors: Red (prohibited for renting), Orange (strictly regulated), Yellow (main focus), Blue (general focus). These different colors also mean different work instructions for the grid data workers. Those who break the rules would be reported and punished by the data workers. In Panyu District,Footnote32 the policy goes further: those (including the tenants and the landlords) with a higher rank in their rental houses would be quantified up to 20 credits, which can be directly used as part of their children’s public school enrollment application. Given that Shenzhen’s Weaving the Net project has been building a more comprehensive data platform, it would not be surprising if the city also sought a more standardized, quantifiable scoring system solidifying the connection between the data produced by data workers and the creation, registration and implications of social credit.

7 Conclusion

In this article, we have presented the new role of data workers in China, positioning them within a context of data hungry policies and technologies, and within a context of policies of people management and control. Focusing on the Weaving the Net program, we have illustrated how data workers can be a lens that bridges the ordinarily separate literatures on the SCS, floating population and smart city. Data workers’ work knits them together, showing that the study of data workers offers an approach to smart cities that begins with narratives and practices of data collection beyond connected technologies. Ethnographically, much work remains to be done, from tracing the organizational structure of the data workers’ team and its specific relations with the local government bureaucratic system to the question of how data workers deal with data (in)consistencies in their daily work. This work is especially important as trenchant critiques of thinking the city computationally emerge (Mattern Citation2021) and technologies continue to attract critical attention in commentaries on Chinese urbanism. We see data workers as a generative community of engagement, both ethnographically and theoretically, for comprehending both the past and futures of Chinese urban governance, and a key route to understanding how new webs are woven for people on the move.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hailing Zhao

Hailing Zhao is a Postdoc Fellow at the Department of Politics and Society, Aalborg University, Denmark. Her research interests centre on civil society, gender, social trust, and Chinese politics.

Rachel Douglas-Jones

Rachel Douglas-Jones is Associate Professor of Anthropological Approaches to Data and Infrastructure at the IT University of Copenhagen.

Notes

1 The official website of the Chinese Central Government’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security: http://www.mohrss.gov.cn/gkml/zcfg/gfxwj/202007/t20200706_378490.html.

2 The shift from social management to social governance is a larger discussion than we can unfold here, however, see He 2016 for a discussion.

3 In the case that the descriptions offered by data workers of their daily work were linked to specific data workers, harm is not a likely result (AOIR Citation2016) We consider the translation and publication of their anonymized stories.

4 Given the huge numbers of migrant workers in the city, there have been debates about the floating population data in Shenzhen for a very long time. The data source we use here for the people with Hukou and permanent residency is from the official website of Shenzhen Municipal Government in 2019: http://tjj.sz.gov.cn/ztzl/zt/sjfb/.

6 ibid., emphases added.

7 Guangdong Provincial Government website http://www.gdzf.org.cn/wzsjb/sjbsh/202012/t20201218_1063288.htm.

8 ibid.

9 In 2007, this figure was 8,764 (Lin Citation2013).

10 Nanfang Daily, https://new.qq.com/omn/20210415/20210415A01IZF00.html.

11 Shenzhen Evening Post, http://www.szszfw.gov.cn/jczl/202003/t20200306_19041785.htm.

13 It should be noted that being a civil servant is not always a good choice in China in the past few decades. In the early 1990s, when Shenzhen was just established as a special economic zone to start the open up policy, it became the most attractive place in China with people giving up their “iron rice bowls” and launching their own private businesses for wealth (Coase and Wang Citation2016). As Hoffman (Citation2006) also argues, the administrative reform within the Chinese state apparatus in the 1990s pushed many university graduates to look for higher paid jobs themselves and become “patriotic professionals” outside the government bodies. However, around the 2010s, more and more research finds that the younger generations in China are returning to the state for jobs again (e.g. Ko and Han Citation2013; Ko and Jun Citation2015; Jiang and Yu 2012). Although the motivations vary, the rising payment and stability of civil servant jobs may have contributed to the rapidly increasing applicant numbers, while the growth of private businesses in China is slowing down (ibid). In Shenzhen, the qualification exams for civil servant jobs have become one of the most competitive exams in China.

15 Government outsourcing has changed the landscape for nonprofits as well as contractors. See Shihua and Gong Citation2020.

17 For full-time “grid members” (the equivalent of Shenzhen’s data workers) across the country Jianyang City, Sichuan Province includes four different categories from those above: “discovering hidden dangers and collecting reports, collecting basic information, investigation and persuasion work in disputes, propaganda and mass mobilization” (2021: 11). These four categories are further broken down into 31 categories, totalling 135 separate tasks.

19 Four techniques are applied: partitioning (dividing people and buildings into grids), monitoring and digital entrance guarding (introducing digital tools for surveillance), and local registration (with the help of community workers) (Gong Citation2016).

20 Huawei’s company website, https://e.huawei.com/cn/videolist/enterprise/e-branding/91871b5f643c40ddae29468485e828c6.

21 Ibid.

22 National Information Centre, see: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/wsdwhfz/202005/t20200515_1228150.html.

25 Huawei’s company website.

26 Huawei’s company website, https://e.huawei.com/cn/videolist/enterprise/e-branding/91871b5f643c40ddae29468485e828c6.

27 ibid.

28 Jiang, Zemin (2002) Address to the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, November 8. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/ziliao_674904/zyjh_674906/t10855.shtml.

29 The Office of the State Council (2007) http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2007-04/02/content_569314.htm.

30 Ministry of Justice of PRC, see http://www.moj.gov.cn/subject/content/2021-01/11/1698_3264372.html.

32 Source: https://www.sohu.com/a/240832588_119778.

References

- Ahmed, Shazeda. 2018. “Credit Cities and the Limits of the Social Credit System.” In AI, Chin, Russia and the Global Order: Technological, Political, Global and Creative Perspectives. Whitepaper.

- Ai, Stefan. 2014. Villages in the City: A Guide to South China’s Informal Settlements. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i.

- Association of Internet Researchers. 2012. Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research: Recommendations from the AoIR Ethics Working Committee (Version 2.0). Accessed May 10, 2021. https://aoir.org/ethics.

- Association of Internet Researchers. 2016. Ethics Graphic.

- Association of Internet Researchers. 2019. Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://aoir.org/ethics/.

- Bach, Jonathan. 2010. “‘They Come in Peasants and Leave Citizens’: Urban Villages and the Making of Shenzhen, China.” Cultural Anthropology 25 (3): 421–458.

- Bray, David. 2008. “Designing to Govern: Space and Power in Two Wuhan Communities.” Built Environment 34 (4): 392–407.

- Chan, K. W. 1994. Cities with Invisible Walls: Reinterpreting Urbanization in Post-1949 China. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chan, K. W. 2009. “The Chinese Hukou System at 50.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 50 (2): 197–221.

- Chen, P. 2006. “Investigating Digital City Management Model.” Journal of Peking University 43 (1): 142–148.

- Chen, Yongxin, and Cheung SY Anne. 2017. “The Transparent Self Under big Data Profiling: Privacy and Chinese Legislation on the Social Credit System.” J. Comp. Law 12 (2): 356–378.

- Cho, M. Young. 2017. “Unveiling Neoliberal Dynamics: Government Purchase (Goumai) of Social Work Services in Shenzhen's Urban Periphery.” The China Quarterly 230: 269–288.

- Coase, R., and N. Wang. 2016. How China Became Capitalist. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cole, Tim. 2018. Interview with Kevin Ashton – inventor of IoT: Is driven by the users. Smart Industry: The IoT Business Magazine. February 11th, 2018. Accessed June 14, 2021. https://www.smart-industry.net/interview-with-iot-inventor-kevin-ashton-iot-is-driven-by-the-users/.

- Creemers, Rogier. 2018. China’s Social Credit System: An Evolving Practice of Control. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3175792.

- Curran, Dean, and Alan Smart. 2021. “Data-driven Governance, Smart Urbanism and Risk-Class Inequalities: Security and Social Credit in China.” Urban Studies. In Special issue: Smart cities between worlding and provincializing. 58 (3): 487–506.

- Dai, Xin. 2018. Toward a Reputation State: The Social Credit System Project of China. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3193577.

- Deichmann, Uwe, Deborah Balk, and Greg Yetman. 2001. Transforming Population Data for Interdisciplinary Usages: From Census to Grid. NASA Socioeconmic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC). New York: Columbia University.

- Du, Juan. 2020. The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univesrity Press.

- Fan, C. C. 2008. “Migration, Hukou, and the Chinese City.” In China Urbanizes: Consequences, Strategies, and Policies, edited by S. Yusuf and T. Saich, 65–90. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Gang, Qian. 2018. China Under The Grid. China Media Project https://chinamediaproject.org/2018/12/07/china-under-the-grid/.

- Gong, R. Yue. 2016. “Rental Housing Management as Surveillance of Chinese Rural Migrants: The Case of Hillside Compound in Dongguan.” Housing Studies 31 (8): 998–1018.

- Goodkind, Daniel, and Loraine A. West. 2002. “China’s Floating Population: Definitions, Data and Recent Findings.” Urban Studies 39 (12): 2237–2250.

- Grommé, Francisca, Evelyn Ruppert, and Baki Cakici. 2018. “Data Scientists: A new Faction of the Transnational Field of Statistics.” In Ethnography for a Data Saturated World, edited by Hannah Knox, and Dawn Nafus, 33–61. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Grommé, Francisca and Evelyn Ruppert. 2019. Population Geometries of Europe: The Topologies of Data Cubes and Grids. Science, Technology and Human Values 45 (2): 235–261.

- Grossi, Giuseppe, and Daniela Pianezzi. 2017. “Smart Cities: Utopia or Neoliberal Ideology?” Cities 69: 79–85.

- Hartley, Kris. 2020. “Public Trust and Political Legitimacy in the Smart City: A Reckoning for Technocracy.” Science, Technology and Human Values. doi:10.1177/0162243921992864.

- He, Zengke. 2016. “From Social Management to Social Governance: Discourse Change and Policy Adjustment.” Journal of Chinese Governance 1 (1): 99–118.

- Hoffman, Lisa. 2006. “Autonomous Choices and Patriotic Professionalism: On Governmentality in Late-Socialist China.” Economy and Society 35 (4): 550–570.

- Hoffman, Samantha R. 2017. “Programming China: The Communist Party’s Autonomic Approach to Managing State Security.” PhD thesis. University of Nottingham.

- Hoffman, Samantha R. 2018. “Managing the State: Credit, Surveillance and the CCP’s Plan for China.” In AI, China, Russia and the Global Order: Technological, Political, Global and Creative Perspectives. Whitepaper, United States Government.

- Holten Møller, Naja, Claus Bossen, Kathleen H. Pine, Trine Rask Nielsen, and Gina Neff. 2020. Who Does the Work of Data? ACM Interactions 27 (3): 52–55. doi:10.1145/3386389

- Hu, Richard. 2019. “The State of Smart Cities in China: The Case of Shenzhen.” Energies 12: 4375. doi:10.3390/en12224375.

- Huang, H. 2015. “Propaganda as Signaling.” Comparative Politics 47 (4): 419–444.

- Huawei. 2017. “Huawei Solutions Help Transform Longgang into a Smart Digital City” Wednesday September 13th, 2017. Advertisement in the Wall Street Journal. https://partners.wsj.com/huawei/news/huawei-solutions-help-transform-longgang-smart-digital-city/.

- Jiang, Min, and King-Wa Fu. 2018. “Chinese Social Media and Big Data: Big Data, Big Brother, Big Profit?” Policy & Internet 10 (4): 372–392.

- Joss, Simon, and Arthur P. Molella. 2013. “The Eco-City as Urban Technology: Perspectives on Caofeidian International Eco-City (China).” Journal of Urban Technology 20 (13): 115–137. doi:10.1080/10630732.2012.735411.

- Kitchin, Rob, and Martin Dodge. 2011. Code/Space: Software and Everyday Life. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Ko, Kilkon, and Lulu Han. 2013. “An Empirical Study on Public Service Motivation of the Next Generation Civil Servants in China.” Public Personnel Management 42 (2): 191–222.

- Ko, Kilkon and Jun, Kyu-Nahm 2015. A comparative analysis of job motivation and career preference of Asian undergraduate students. Public Personnel Management, 44 (2): 192–213. doi:10.1177/0091026014559430

- Laurent, Brice, Liliana Doganova, Clément Gasull, and Fabian Muniesa. 2021. “The Test bed Island: Tech Business Experimentalism and Exception in Singapore.” Science as Culture. doi:10.1080/09505431.2021.1888909.

- Lee, C. Kwan. 2007. Against the Law: Labor Protests in China’s Rustbelt and Sunbelt. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Liang, Fan, et al. 2018. “Constructing a Data-Driven Society: China’s Social Credit System as a State Surveillance Infrastructure.” Policy & Internet 10 (4): 415–453.

- Lin, Wen. 2013. “Digitizing the Dragon Head, geo-Coding the Urban Landscape: Gis and the Transformation of China’s Urban Governance.” Urban Geography 34 (7): 901–922.

- Lindtner, Silvia. 2020. Prototype Nation: China and the Contested Promise of Innovation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Liu, Chuncheng. 2019. “Multiple Social Credit Systems in China.” Economic Sociology 21 (1): 22–32.

- Liu, Chuncheng. 2021. “Seeing Like a State, Enacting Like an Algorithm: (re)Assembling Contact Tracing and Risk Assessment During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Science, Technology and Human Values 47 (4): 698–725.

- Löfgren, K., and C. W. R. Webster. 2020. “The Value of Big Data in Government: The Case of ‘Smart Cities’.” Big Data & Society. January 2020. doi:10.1177/2053951720912775.

- Lumba, Luigi. 2014. The Government Next Door: Neighborhood Politics in Urban China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Madsen, Anders Koed. 2018. “Data in the Smart City: How Incongruent Frames Challenge the Transition from Ideal to Practice.” Big Data & Society 5 (2). doi:10.1177/2053951718802321.

- Marvin, S., A. Luque-Ayala, and C. McFarlane, eds. 2015. Smart Urbanism: Utopian Vision or False Dawn? Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mattern, Shannon. 2017. “A City is Not a Computer” Places Journal. https://placesjournal.org/article/a-city-is-not-a-computer/

- Mattern, Shannon. 2021. The City is not a Computer: Other Urban Intelligences. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Medina, Eden. 2011. Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Meissner, M. 2017. “China’s Social Credit System: A big Data-Enabled Approach to Market Regulation with Broad Implications for Doing Business in China.” Merics China Monitor 39: 1–13.

- Meissner, M., and J. Wübbeke. 2016. “IT-Backed Authoritarianism: Information Technology Enhances Central Authority and Control Capacity Under Xi Jinpin. MERICS Papers on China, pp. 52–56.

- Mittelstaedt, Jean Christopher. 2021. “The Grid Management System in Contemporary China: Grass-Roots Governance in Social Surveiallance and Service Provision.” China Information. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203C211011565.

- Naughton, B. 2007. The Chinese Economy: Transitions and Growth. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Neagli, Jackson Paul. 2021. “Grassroots, Astroturf, or Something in Between? Semi-Official WeChat Accounts as Covert Vectors of Party-State Influence in Contemporary China.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 50 (2): 180–208.

- O’Donnell, Mary Ann, Winnie Wong, and Jonathan Bach. 2017. Learning from Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao City from Special Zone to Model City. Chicago: University of Chicaog Press.

- Ross, Andrew. 1993. “The new Smartness.” Science as Culture 4 (1): 94–109.

- Ruppert, Evelyn. 2009. “Becoming Peoples: Counting Heads in Northern Wilds.” Journal of Cultura Economy 2 (1–2): 11–31.

- Ruppert, Evelyn, and Stephan Scheel, eds. 2021. Data Practices: Making Up a European People. London: Goldsmiths Press.

- Shelton, T., Matthew Zook, and Alan Wiig. 2015. “The ‘Actually Existing Smart City’.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 8: 13–25.

- Shihua, Ye, and Xiaochen Gong. 2020. “Nonprofits' Receipt of Government Revenue in China: Institutionalization, Accountability and Political Embeddedness.” Chinese Public Administration Review 12 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/153967542101200101

- Söderström, Ola, Till Paasche, and Francisco Klauser. 2014. “Smart Cities as Corporate Storytelling.” City 18 (3): 307–320.

- Solinger, D. 1999. Contesting Citizenship in Urban China: Peasant Migrants, the State, and the Logic of the Market. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Tang, W. S. 2000. “Chinese Urban Planning at Fifty: An Assessment of the Planning Theory Literature.” Journal of Planning Literature 14 (3): 347–366.

- Tang, Beibei. 2020. “Grid Governance in China’s Urban Middle-Class Neighbourhoods.” The China Quarterly 241: 43–61.

- Tang, T., and A. T. Ho. 2019. “A Path-Dependence Perspective on the Adoption of Internet of Things: Evidence from Early Adopters of Smart and Connected Sensors in the United States.” Government Information Quarterly 36: 321–332.

- Tech. 2016. Sesame Credits Hu Tao: Technology+Credits, The Future of Smart City (芝麻信用 胡涛:科技+信用,智 慧城市的未来 zhīma xìnyòng Hú Tāo: kējì+xìnyòng, zhìhuìchéngshì de wèilái), viewed 11th March 2018, https://kknews.cc/tech/ljj949.html.

- Tomba, Luigi. 2014. The Government Next Door: Neighbourhood Politics in Urban China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Walford, Antonia. 2021. “Data- Gene-Ova- Data.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 27: 127–141.

- Wan, Tingting. 2021. “Emotion Governance and Practice Resilience in the Reflexive Modernity: How Community Social Workers in a low-Risk Chinese City Work with People from Wuhan.” Qualitative Social Work 20 (1–2): 323–330.

- Wang, F.-L. 2005. Organizing Through Division and Exclusion: China’s Hukou System. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Wang, Di, and Sida Liu. 2021. “Doing Ethnography on Social Media A Methological Reflection on the Study of Online Groups in China.” Qualitative Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004211014610.

- Westerveld, L., and A. K. Knowles. 2020. “Loosening the Grid: Topology as the Basis for a More Inclusive GIS.” International Journal of Geographical Information Science. doi:10.1080/13658816.2020.1856854.

- Willems, Thijs, and Connor Graham. 2019. “The Imagination of Singapore’s Smart Nation as Digital Infrastructure: Rendering (Digital) Work Invisible.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal 13 (4): 511–536. doi:10.1215/18752160-8005194.

- Wu, Qiang. 2015. “Gridding, Mass Line and Social Management Innovation: A Comparative Study of Gridding Management in China from an Anthropological-Political Perspective.” The China Nonprofit Review 7 (1): 110–138.

- Xi, Q. 2019. “年智慧城市研究与实践热点回眸.” 科技导报 2020 38 (3): 157–163.

- Xiang, Biao. 2005. Transcending Boundaries: Zhejiangcun: The Story of A Migrant Village in Beijing. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Yang, G., and S. Wu. 2018. “Remembering Disappeared Websites in China: Passion, Community and Youth.” New Media & Society 20 (6): 2107–2124.

- Yang, Fan, and Jian Xu. 2017. “Privacy Concerns in China’s Smart City Campaign: The Deficit of China’s Cybersecurity Law.” Asia & The Pacific Policy Studies. doi:10.1002/app5.236.

- Zhang, Li. 2001. Strangers in the City: Reconfigurations of Space, Power and Social Networks within China’s Floating Population.

- Zhang, Li. 2010. In Search of Paradise: Middle Class Living in a Chinese Metropolis. Stanford University Press, Stanford CA: Cornell University Press.

- Zhang, Chenchen. 2020. “Governing (though) Trustworthiness: Technologies of Power and Subjectification in China's Social Credit Syste.” Critical Asian Studies 52 (4): 565–588.

- “Zhonggong zhongyang guanyu quanmian shenhua gaige ruogan zhongda wenti de jueding” (Decisions taken by the Central Committee of the CCP on important issues regarding the overall deepening of reforms.” Dongfangwang, 18 November 2013, http://www.china.org.cn/china/third_plenary_session/2013-11/16/content_30620736.htm