Abstract

A landmark citizen’s lawsuit against Formosa Plastics Corporation in Seadrift, Texas resulted in funds for environmental monitoring, clean-up, research, and education. $20 million is set aside for “creating a cooperative that will revitalize depleted marine ecosystems and develop sustainable fishing, shrimping, and oyster harvesting.” It is an exciting project for many reasons, exemplifying what the work of “just transition” looks like on the ground. Work toward just transition in Seadrift will be multifaceted and extensive in both space and time. In what follows, we describe the contexts and contours of this work, highlighting developments before, within and after the Waterkeeper’s historic legal win, and the different kinds of work required at each stage. These sequential labors of law, we argue, are usefully conceptualized as a far-from-straightforward relay, with many runners, and many detours. Our goal is to convey the especially complex challenge of environmental advocacy and just transition in late industrial contexts.

1 Just Transition on the Ground

Once a month, more than 60 men in Seadrift, Texas meet to envision and plan a new harbor, docks, a fish processing house and other infrastructure to support the local fishing industry—an industry once a mainstay of their small community, but no longer. The men work with an organizer from the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, an organization known for innovative work supporting Black farmers, landowners, credit unions, and agricultural cooperatives across the US South. Funds to support the fishermen’s plans were garnered from a landmark citizen’s lawsuit against Formosa Plastics Corporation under the US Clean Water Act, settled in 2019. None of the settlement funds will go to the plaintiffs, who filed the suit as “Waterkeepers.” Instead, the funds have been deposited in a trust that will support environmental monitoring, clean-up, research, and education. $20 million is set aside for “creating a cooperative that will revitalize depleted marine ecosystems and develop sustainable fishing, shrimping, and oyster harvesting.”Footnote1 It is an exciting project for many reasons, exemplifying what the work of “just transition” looks like on the ground.

Articulations of just transition first emerged in the industrial labor movement in the 1980s to counter claims that high-paying industrial jobs were at odds with workplace and environmental protections (Stevis Citation2023; Stevis et al. Citation2020). After decades of detours, a growing concert of voices today is calling for and trying to figure out just transitions in diverse settings around the world. Environmental protection and inclusive prosperity is the goal. Lingering specters of fossil-fuel capitalism don’t fully undercut alternatives, but they do continue to shape them (Adams Citation2023; Adams and Fortun Citation2021). Seadrift—literally and figuratively—is at the center of the storm.

The Waterkeeper’s win is the largest legal settlement in the history of cases rooted in the U.S. Clean Water Act, including money that can be used to build alternative economies in Seadrift’s Calhoun County. The legal win also mandates that the law itself becomes protective and productive, countering law’s illiberal capture by what it needs to govern (here, industrial corporations) (Salcido Citation2022: 325). Because of the settlement’s zero-discharge mandate, Formosa will be fined $10,000 a day—and up to $30,000 a day after 2023—if caught discharging plastics. Formosa has thus become subject to law through law. Legal action (a citizen law suit) has forced the state to act lawfully (fining Formosa for violating the US Clean Water Act and the settlement’s zero discharge mandate). This, in turn, generates still more funds for the region’s transition, creating a unique opportunity for grassroots innovation (Ariztia et al. Citation2023).

The afterlife of the 2019 Waterkeeper’s settlement will be far from straightforward. A vast net of issues, people, and places will need to be connected and coordinated to realize its promise. In Calhoun County, plastic pellet hunting and collection will continue (), as will ecological restoration and work to run a new, locally owned dock. Local activist Diane Wilson, long known for her “wild cat” approach, will be an important figure, in a new way. After years of dramatic civil disobedience—because that was the only way she could draw attention to the problems she was concerned with—Wilson is now in a leading role as steward of the Waterkeeper’s settlement.

Figure 1 A billboard in Port Lavaca, Texas, set up by the citizen science group NurdlePatrol with funds generated from the Waterkeeper settlement. Photo by Tim Schütz, October 2022.

Extra-local dynamics will continue to be important. Formosa Plastics is a vertically integrated, Taiwanese multinational corporation with a long record of malfeasance and what commentators have called “mafia-like” behavior toward environmental activists and other critics (Democracy Now! Citation2020; Patton et al. Citation2021). In recent years, activists in Formosa plant communities in Taiwan, Vietnam and the United States have extended the ways they work together for corporate accountability (Tubilewicz Citation2021). Nearly 8,000 fisher people affected by a toxic-release disaster caused by a Formosa-owned steel mill in Vietnam have taken legal action in Taiwan, for example (Fan, Chiu, and Mabon Citation2022). The legal action is supported by a vast network of diasporic Vietnamese who work closely with lawyers and activists in Taiwan, academics, and activists in the United States, and a prominent human rights lawyer in Montreal. The legal win against Formosa in Calhoun County is an important inspiration and referent. Diane Wilson is a key link between the sites and cases.

Work toward just transition in Seadrift and other Formosa communities has been and will be multifaceted and extensive in both space and time. In what follows, we describe the contexts and contours of this work, and the constantly shifting terrain that environmental advocates must navigate. Our goal is to convey the especially complex challenge of environmental advocacy and just transition in late industrial contexts.

First, we situate our analysis in wide-ranging scholarship on advocacy, governance, law, and social change, then explain our focus on advocacy for just transition, understood in late industrial context. The next section draws out the history and late industrial dynamics of Calhoun County, intensified by the shale oil and gas boom. We then describe developments before, within and after the Waterkeeper’s historic legal win, highlighting the different kinds of work required at each stage. These sequential labors of law, we argue, are usefully conceptualized as a far-from-straightforward relay, with many runners, and many detours. In concluding, we return to considerations of ways late industrialism sets the stage for just transition advocacy, law, and research.

1.1 Backstories and Methods

Our engagement with Seadrift is long-running, coming from different angles. Kim Fortun met Seadrift activist Diane Wilson in the early 1990s, through work in an organization called “Communities Concerned about Carbide,” formed to link Carbide communities around the world as a way to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the 1984 Union Carbide Disaster in Bhopal, India. Union Carbide’s Seadrift plant was an active focus. In 1991, the plant exploded, killing one worker, injuring 26 others and rattling windows up to 50 miles away (UPI Citation1991). People living nearby thought the Persian Gulf War had come home. Wilson, working with the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union, documented the disaster and helped expose the corporate negligence behind it. She also became a leading figure in transnational efforts to hold Union Carbide accountable for the Bhopal disaster, which gained new momentum after the 1991 settlement of the Bhopal case by the Indian Supreme Court—for an amount widely perceived as “shamefully inadequate.” Kim Fortun’s book, Advocacy After Bhopal, rotates around the legal settlement of the Bhopal case (Fortun Citation2001). Importantly, litigation of the Bhopal case continues today, on various fronts. In June 2022, for example, a court in Bhopal, after years of delay, finally found seven employees of Union Carbide’s subsidiary in India criminally guilty of death caused by rash or negligent acts leading to the Bhopal disaster—with implications for both legislation and other legal cases in India (Krishna Citation2022). Litigating Bhopal has been a long game.

Tim Schütz began collaborating with Wilson in 2020 through shared concern about Formosa Plastics Corporation, which also has a plant near Seadrift. Schütz first learned about Formosa Plastics during an experimental, collaborative field study held in step with the 2019 annual meeting of the Society for Social Studies of Science (4S) in New Orleans. The field study—organized around the concept of “Quotidian Anthropocenes”—linked local and visiting researchers and activists in work to understand the local-particularities of the regions’ environmental stress, mobilizing local, global and planetary frames (Fortun et al. Citation2021). A proposal to build a new, $9 billion Formosa plant in the area was an important focus, drawing in “No Formosa Plastics” activists (and 4S conference participants) from Taiwan, linking out to Wilson. The meeting extended the transnational activists network focused on Formosa, at work since 2018 (Dermansky Citation2018). The Formosa Plastics Global Archive, designed and built by Schütz, in conversation with many collaborators, is one result (Schütz and Su Citation2021).

James Adams’s early research focused on just transition in Austin, Texas, accounting for what he calls “petro-ghosts” (historical legacies that condition the present and future, even when they are explicitly disclaimed) (Adams Citation2023; Adams and Fortun Citation2021). More recently, Adams has done collaborative ethnographic work in multiple places in the United States—Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Adams et al. Citation2022) and Santa Ana, California, as well as Calhoun County—to examine how just transitions, and environmental justice more broadly, have been undermined by dispersions of state power. His interest is in the forms of domination and resistance that are taking shape in and through this dispersion, looking for ways to “regroup” the state as a mode of resistance.

Fortun, Schütz, and Adams have collaborated on many projects, coming together for this writing to address shared questions about the dynamics of environmental governance in different settings. The analysis here also extends from on-going dialogue with Diane Wilson, much of which occurred in the collaborative process of building the Formosa Plastics Global Archive, a digital archive designed to document the operations and harms of Formosa Plastics Corporations in sites around the world, helping connect places and people. We have come to think of this method as “archive ethnography,” wherein the selection and commentary on artifacts added to the archive creates especially rich, highly focused articulations of what happened, why, implications, on-going questions, and so on. Select artifacts operate like an anchor around which descriptions, interpretations, and affective responses can rotate (the settlement’s consent decree, or worker’s court depositions, for example).Footnote2 Archive ethnography is a method particularly suited to late industrialism, an era partly characterized by overwhelming amounts of data, critical data gaps, contestations over the meaning of data, and the need for what we have come to think of as kaleidoscopic perspective (being able to see the same phenomena from many angles, through many different lenses). Archive ethnography works to build the knowledge infrastructures called for by late industrialism.Footnote3

1.2 Framing Just Transition

“I am busier than I was before, because now you have this historical document for zero discharge of plastics, from a company that is notorious in the state of Texas, which is notorious. Now we got it! TCEQ, our state environmental agency, thinks they might just make all companies do zero discharge. It just keeps getting broader and broader. Also, to get a company that has been polluting for so long, and with that mindset, to get them to zero—and I do mean, zero—you have to do stuff with the engineers, you have to do stuff with the remediation, with the cleanup. And, how do you do the cleanup? Nobody's ever done clean up with this amount of plastic pellets and powder. They don't know how it's done, so we're creating it. Also, to monitor Lavaca Bay, that's a huge bay, and it goes into Matagorda Bay. How do you monitor an open system like that? Our expert is devising something that's never been done before. Before the water hits the bay, it goes through this device, and there's four different ways they can determine if Formosa is violating their permit for plastics, flakes, pellets, anything like that, and if there's a violation. That's the beauty of it too—we get to be the enforcement and the monies go to local projects of our choosing, and that's kind of unheard of. So a lot of it is just new stuff and you're, you're creative. It's very creative right now, but it's very, I don't know the word for it, it's an interesting time.”

Diane Wilson, interview by Fax Bahr, Texas, August 25, 2020. https://disaster-sts-network.org/content/interview-diane-wilson-20200825

Our focus here is on advocacy and law for just transition, in a late industrial frame. Late industrialism refers to both a historical era (since the 1980s) and an analytic framework that draws out dynamic, intensifying productions of environmental harm. The 1984 Union Carbide chemical plant disaster in Bhopal, India heuristically marks the late industrial turn, emblematic for a socio-technical world order that has far outpaced capacity to govern it. The structural inability to establish accountability for the Bhopal disaster through law is illustrative (Baxi and Dhanda Citation1990; Cassels Citation1991; Fortun Citation2001; Krishnan Citation2020).

A late industrial analysis draws out how tight coupling between different kinds of systems (ecological, economic, technological, discursive, and so on), across scale, weighted by history, laced by commercial interests, produces contemporary conditions of possibility. A late industrial analysis describes the dynamics of these tightly laced systems, and how they produce environmental hazards, injustice, and mammoth governance challenges (Ahmann Citation2020; Ahmann and Kenner Citation2020; Fortun Citation2012; Citation2014; Citation2021; Kenner Citation2020; Pandey Citation2015).

Many late industrial dynamics are recurrent across places, though always with differences. By the late 1980s, for example, industrial development had produced extensive toxic contamination—that was rendered visible and thus subject to public accountability because of new digital technologies, right-to-know laws, and resulting public release of data. At the same time, however, capital intensive anti-regulatory movements made it ever more difficult to act on this data, throwing ever more responsibility for governance onto non-state actors. Further, the atomizing conceptual and organizational forms of industrialism persisted, making it difficult to represent toxic harms in law, science, and other authoritative discourses. Major advances in the environmental health sciences—showing how toxic chemicals cross and harm body systems, accumulate and persist—had to creatively skirt this atomization. Late industrialism is thus a time of contestation, and continuing intensification. The shale energy revolution has been a notable driver, leading to dramatic increases in the production of oil and gas in the United State, allowing for unprecedented fuel exports, spurring staggering plans for increased plastics production (Gardiner Citation2019; Sicotte Citation2020; Upton Citation2013). The tangle of late industrial problems continues to tighten.

We mobilize a late industrial frame to draw Calhoun County—and the challenges of environmental advocacy and just transition there—into sharp relief. Calhoun County, in turn, powerfully conveys the force of late industrialism, and the creative forms of advocacy it has engendered.

Importantly, thinking about and working toward just transition emerged with late industrialism, in labor organizing in the US petrochemical industry in the 1980s—particularly on the US Gulf Coast. Union leader Anthony Mazzochi was a critical voice, building from his earlier work helping establish the US Occupational Health and Safety Act, while also building ties with the environmental movement (International Joint Commission Citation1995). Political scientist Dimistris Stevis explains,

“The strategy of just transition was originally developed by the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers’ Union (OCAW) during the late 1980s as a solution to the adverse impacts of environmental policies on workers and communities dependent on environmentally harmful practices, particularly those involving chemicals … . Thirty years later, the inclusion of just transition in the 2015 Paris Agreement, followed by the December 2018 Silesia Declaration on Solidarity and Just Transition, has made the concept highly visible and highly contested.” (Stevis Citation2021: 249)Footnote4

Ethnography—especially archive ethnography—allows for these many threads to be drawn together, seeing both patterns across sites, and variation; differences among social actors; where existing theory has explanatory power, and where it misses the mark; and where’ scholarship can scaffold political practice. Perhaps most importantly, ethnography allows scholars to be drawn into and directed by the worlds we study, following the lead of figures like Diane Wilson.

2 Late Industrial Calhoun County, Local and Global

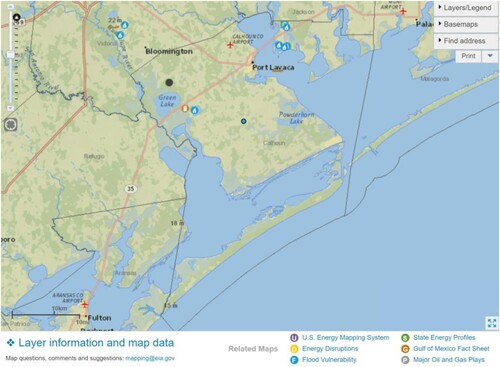

Calhoun County is a rural yet highly industrialized county on the Gulf Coast of Texas, 150 miles south of Houston, 240 miles north of the Mexican border (). Most of the land area in the county is a peninsula, with bays on three sides. These numerous bays and waterways have long been important to life in the region; Indigenous Karankawa, for example, used the shallow waterways for travel, fishing, hunting and gathering (Lipscomb and Seiter Citation2020).Footnote5 The region is hurricane intensive, and especially vulnerable to climate change.

Figure 2 Maps showing Calhoun County's bays and barrier island, petrochemical facilities and pipelines. FracTracker Website. https://ft.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?appid=0cdff7e116c0425fa55d1226e9204477, last accessed October 5, 2023.

After colonization, prior to the US Civil War, Calhoun County became a prominent cattle and slave trading center, connected by regular steamship routes to New York City (Kleiner Citation2020). With its vital ports and railways, the county soon became a prime target of the Union army. Union forces bombarded Port Lavaca, occupied the region and destroyed much of the local infrastructure (Maywald Citation2021; Kleiner Citation2020).

Calhoun County built back slowly after the war, but the expansion of the Texas railroad system in the 1880s ensured that Calhoun County’s former status as a major shipping port for cattle would never be revived (Maywald Citation2021). Port Lavaca regained some standing as a small cattle-trading town, but most of the regional economy was rebuilt around fishing, shrimping, oystering and seafood packaging.

Today, all the local fish houses are gone. Most of the fishing infrastructure is now owned by big businesses that have cut local fishers out of dock space. Extensive pollution from industry, exacerbated by climate change, has also undercut the productivity of the bays and its fishing communities.

Pittsburgh-based Alcoa Corporation, which pioneered the refining processes that made aluminum “an affordable and vital part of modern life” (Alcoa Citation2023), built an aluminum smelter in Port Comfort in 1947. Alcoa ceased operations in Port Comfort in 2019, leaving behind a massive waste site contaminated with mercury. The waste site—extending beyond the Alcoa plant site into surrounding waters—was designated a US Superfund site in 1994, and is still managed by the US Environmental Protection Agency. The waste management process involves “monitored natural attenuation” wherein marine contaminants are allowed to settle until they are buried by clean sediment and no longer available for uptake by marine life (Redfern Citation2021). Recently, plans to dredge the Calhoun County port to provide access to Suezmax-size tankers (spurred by the shale gas boom) threatened to unsettle Alcoa’s contamination and what EPA intervention had accomplished.

Union Carbide Corporation, another major industrial player in Calhoun County, arrived in 1952, helping usher in the “age of plastics.” Union Carbide’s Seadrift plant produces ethylene oxide, a basic chemical building block important in plastics production, and as a disinfectant. Ethylene oxide is also carcinogenic. A 2019 study published by investigative journalists again drew the Union Carbide Seadrift plant into the spotlight, reporting that the plant produces cancer risks 160 times what the US EPA deems acceptable risk (ProPublica Citation2021). In 2023, Union Carbide (represented by Dow), announced plans to build a small modular nuclear reactor at their Seadrift plant, framed as an effort to decarbonize its operations. This initiative secured $25 million in backing from the Department of Energy to facilitate the expansion of plastics and packaging materials production (Drane Citation2023) ().

Many factors work against environmental protection and justice in Calhoun County. The county has a notably low score for “youth opportunity,” for example, based on an aggregation of indicators pointing to the number of children in preschool, on-time high school graduation, and rates of post-secondary education (Opportunity Index Citationn.d.). This makes it hard for Calhoun County youth to leave the area, or stay. There is also a history of conflict between Anglo and Vietnamese fishermen who came to the region in the wake of the Vietnam War, in which many from Calhoun County served (Byman Citation2022; Wilson Citation2005). Today, there seems to be a quiet, separate peace (Cahalan Citation2019). Organizing the fishing community across these differences is challenging, to say the least, and further complicated by conflicts between Democrats and Republicans. Calhoun County votes solidly red [Republican]. Conservative churches also have a large presence. Many people—across these differences—express anti-government sentiments.

The tangle of agencies and authorities responsible for governing Calhoun County—each with its own mandate, jurisdiction, culture and expertise—also complicates and often undermines environmental governance. The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration comes to the county when plants blow up and kill workers, with rare visits otherwise. The US Environmental Protection Agency continues to manage the Alcoa Superfund site. The Army Corps of Engineers (a federal agency with responsibilities for civil works focused on navigation, flood and storm damage protection, and aquatic ecosystem restoration) is responsible for port projects. The Corps of Engineering is infamous for cost–benefit led approaches that privilege commerce over ecology. The Calhoun Port Authority, responsible for operating the port, has a banner on their webpage that describes their approach: “[With] deep expertise in petrochemicals, Our world-class port helps petrochemical companies save time and money” (Calhoun Port Authority Citation2023). Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), is also in the mix, as is Texas Parks and Wildlife (TPW). The US EPA has threatened to revoke TCEQ's right to permit because its record has so favored industry. Texas Parks and Wildlife game wardens are especially reviled by local fishermen for stewarding the bays in ways that make it impossible to earn a living.

All of these agencies have important, seemingly well-delineated roles to play in environmental governance. But they also fragment and often capitalize on the problem, undercutting understanding and stewardship of the region as a living and lived-in whole. They also work with fragmenting methods—developing environmental impact statements for a single industrial operation in a region for example, without regard for cumulative impacts.

Journalist Jessica Priest (Citation2019) says that Calhoun County has been “forged by aluminum and reshaped by plastic.” Lisa Sorg (Sorg Citation2002) says that Seadrift is quiet, but “stinks like hell.” Diane Wilson says that she thinks that “companies are drawn to rural areas … Places where there won't be a big outcry and they just slide on in” (Sorg Citation2002; see also Freemantle Citation2002).

In some ways, Calhoun County moves slowly, but the challenge of just transition is also intensifying, in ways rife with contradictions; scrambles to ride the shale gas boom, for example, are at odds with work to ready the region for the escalating effects of climate change. A just transition to a more environmentally protective, economically inclusive future will be scientifically, technically, politically, socially, and culturally complex. Contemporary environmental advocacy must deal with it all.

2.1 Global Connections: Formosa “Slides on in”

As Diane Wilson explains, Formosa Plastics “slid on in” to Calhoun County in 1989, at a time when unemployment was especially high because Alcoa had recently cut its workforce by 70% (downsizing from 2,700 to 850 employees) (Tubilewicz Citation2021). Formosa was founded in Taiwan in 1954 by the brothers Wang Yung-ching and Wang Yung-tsai with funding from the US Agency for International Development (Shah Citation2012: 12). From the beginning, Formosa has had close ties to the Taiwanese government and is considered integral to the country's economic miracle development (Wu Citation2022). During the period of the Kuomintang's (KMT) authoritarian rule, industrial development was carried out by the state without opposition (Ho Citation2014). However, with the lifting of martial law in 1987, citizens began organizing mass environmental protests, specifically targeting the expansion of the petrochemical industry (Ho Citation2014). As pressure mounted within Taiwan, Formosa began building plants in other locations (Elkind Citation1989; see ). Their first plant in the United States was in Baton Rouge, at the top of the 80-mile stretch of the Mississippi River now known as Louisiana’s Cancer Alley. Another site in Louisiana—at the lower end of Cancer Alley—competed with Calhoun County for Formosa’s new plant—which promised to provide 2,700 new jobs and $3.2 billion in investment, a sum “worth more than all of Calhoun County” (Elkind Citation1989: 78). The Executive Director of the Calhoun County Economic Development Corporation put the County’s rationale bluntly: “It’s either industry or unemployment […] once we get our economy stabilized, then we can afford to be a little bit more choosy with who and what we let in” ().

Figure 3 Map showing Formosa Plastics operations around the world, excerpted from the report “Formosa Plastics Group: A Serial Offender of Environmental and Human Rights,” published by the Center for International Environmental Law in collaboration with the Center for Biological Diversity and Earthworks. The report covers Formosa's long track record of violations, the special hazards of plastics production, the corporation's complex web of subsidiaries, and plans to expand Formosa’s operations in Louisiana (Patton et al. Citation2021). Reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Formosa has continued to expand in Calhoun County over the years. Today, there are plans for a $200 million USD expansion in plastics production to “cash in” on cheap U.S. shale gas, a result of the fracking boom since the mid 2000s (Beyond Plastics Citation2021). Ironically, the success of environmental organizing to keep Formosa from building a new facility in Louisiana may be bringing more of Formosa to Calhoun County. Most often, locals have learned about expansions (and accidents and “near upsets”) through informal exchanges rather than through official processes. Formosa, they say, has just done what it wanted, seemingly beyond the reach of law.

Global corporations like Formosa Plastics have the financial and socio-cultural capital necessary to exploit differences in the biopolitical regimes of various local and national governments, for whom their considerable economic promise makes ecological compromise seductive (especially to struggling economies like Calhoun County). As political scientist Tubilewicz argues, corporate executives are often able to undermine local environmental justice efforts by threatening disinvestment in the community (Tubilewicz Citation2021). Writing about the development of the shale gas industry in Northern Australia, Howey and Neale describe how incapacity to track flows of toxins across jurisdictions is often produced by design, through what they call “divisible governance.” Such incapacity is more than a mere effect; it’s a tactic used to undercut the public’s ability to conceive and reign in the environmental risks produced by fossil fuel industries. “Through jurisdictional and temporal fragmentation of risk,” they argue, “divisible governance both governs and sustains ignorance about the gas industry’s operations and its likely impacts while fracking gains traction with each passing approval” (Howey and Neale Citation2022: 21).

Failures of environmental governance in Calhoun County are thus difficult to see; they operate through divisions that separate people, places and the many factors that undermine inclusive prosperity. This challenges environmental advocates (and their knowledge infrastructures) in many ways, and makes defragmentation an important political strategy and goal. In this, environmental advocates must resist a fundamental late industrial contradiction: continuing reliance on atomizing, essentialist approaches (deeply institutionalized in government and easily exploitable by private interests) that undermine recognition of places, people and issues as tightly entangled—tied together such that action anywhere in the net loosens, wholly undermines or at least tugs on possibilities elsewhere. As a result, environmental advocates are challenged not to focus, taking on everything at once, working also against deeply entrenched idealizations of “focus” as the mark of maturity and capacity. Late industrialism calls for this, too—cultural as well as institutional and political change—before, during and after “the law” per se. Environmental advocates again take the lead.

3 Before the Law: Calling the State out

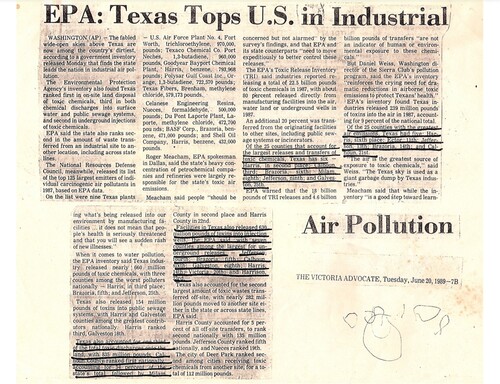

Diane Wilson is an important voice in and for Calhoun County. Her trajectory as an activist also exemplifies what has motivated, shaped and undermined environmental advocacy since the 1980s. A mother of five and fourth-generation shrimp boat captain, Wilson became an environmental activist following the 1989 publication of the first US Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) data, which ranked Calhoun County worst in the nation for volume of toxic discharges to land (Fortun Citation2009; Wilson Citation2005: 36). Calhoun County also ranked high for air emissions (). TRI data were available because of US legislation passed in the wake of Union Carbide’s 1984 pesticide plant disaster in Bhopal, India, which many describe as a “wake-up call” about the dangers of the petrochemical industry. Creation of the TRI was part of a broad commitment to “environmental right-to-know,” which quickly multiplied the types and quantity of data available to characterize environmental risks and harms. For many, like Wilson, this was transformative. Wilson’s sense of the Calhoun County landscape and waterways she thought she knew so well changed forever ().

Figure 4 An excerpt of the 1989 news article in the Victoria Advocate through which Diane Wilson first learned about Calhoun County's toxic load.Footnote6 Her preservation of the article was the start of what has become a major amateur archiving initiative. Like in the human rights, migrant, and HIV/AIDS movements, amateur archivists have become critical to the environmental justice movement (Deutch and Habal Citation2018; Faulkner Citation2019; Caswell Citation2021; Cifor Citation2022; Tansey Citation2023). Image by Diane Wilson, used with permission.

Wilson began collecting everything she could get her hands on, from leaked company reports, photos taken by workers inside the plant, and recorded interviews with workers. At first, she would bring this information to mainstream newspapers, often to point out their errors, sure they would be corrected. It wasn’t long before she realized that the disinformation was often by intent (Wilson Citation2005). This is what prompted her to start her now decades-spanning news article collection to keep up with it all—the truth and the lies, as she puts it. Her collection now overwhelms her home and an adjacent barn.

In her early days as an environmental advocate (), Wilson organized meetings and filed petitions, but her calls to protect the bays fell on deaf ears. This, in turn, prompted an array of dramatic acts of civil disobedience. Wilson sank her own boat where the Formosa plant discharged into the ocean. She chained herself to the tower of the Union Carbide factory to drop a banner saying “Remember Bhopal” (and was arrested on terrorist charges). She’s gone on many hunger fasts, many up to 40 days long. The hunger strikes called for diverse actions: environmental impact statements, zero-discharge mandates, and unionization of Formosa employees, for example. One positive result was Wilson’s visibility to whistleblowers from within Calhoun County’s plants.

Figure 5 Cover for the children’s book “Nobody Particular” by Molly Bang (Citation2000) about Diane Wilson’s emergence as an environmental activist. Artwork by Molly Bang, reproduced with permission.

In the 1990s, a shift supervisor and wastewater manager at Formosa Plastics, Dale Jurasek, found himself suffering from sores that no doctor in Calhoun County could explain. Only months later, after several visits to a regional medical center associated with the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration, did Jurasek learn that chemicals he was exposed to at Formosa had caused irreparable damage to his nervous system. He also learned about Diane Wilson, and in 2008, reached out for a meeting—at a meeting place out of town so neighbors wouldn’t recognize them. The result was a coalition that has had staying power.

Coalitions between labor and environmental activists have always been difficult, depending on skilled organizers capable of moving between and within very different conceptual frames, and—often (not in this case because Formosa wasn’t unionized) between loosely structured grassroots organizations and highly structured unions. This capacity to shift frame, organizational styles, and modes of articulation are ever more important today as understanding of environmental problems becomes ever more multidimensional, implicating different stakeholders, including many different government agencies, at many scales, all speaking different bureaucratic languages. The challenge of course intensifies when working across national lines.

Wilson explains the challenge well: When interacting with Texas Parks and Wildlife, “it's all about the turtles.” When contesting air pollution, working the difference between what federal and Texas law requires is critical. When backing Latinx oystermen fined by game wardens, the language and law of civil rights is at the fore. When calling out the Taiwanese state to govern its multinational corporations, the emphasis is on corporate accountability and Taiwan’s standing on the world stage.

When Wilson and other anti-toxics activists first mobilized in the 1980s, the deregulatory spiral set in motion by Reaganomics was just picking up speed. Ironically, the public release of environmental hazard data during this same period was part of this, with “voluntary disclosure” (of environmental data) replacing “command and control” approaches. This meant that much work that followed was in calling the state out, with communities bearing the burden of proof, which had to be continually reformatted for different audiences and ends. Many kinds of data and science needed to be mobilized, interweaving community, academic, and government work.

3.1 Mobilizing Different Sciences

Wilson knew about Formosa’s release of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) powder from early on—it blew into people’s yards, swimming pools and cars, leaving a white residue. But she only learned about plastic pellets in 2016—when Dale Jurasek, then a wastewater manager at Formosa Plastics, told her about the routine release of huge amounts of plastic pellets into Formosa’s wastewater, which he had been instructed to cover up. Together with another shift manager, Ronnie Hamrick, Wilson and Jurasek started going down to Lacava Bay to look around. Soon it became clear that the pellets were coming from Formosa’s ten stormwater outfalls, which Wilson began to explore by kayak. At the time, Formosa was applying for a renewal of their wastewater permit, so there seemed to be a window of opportunity to hold Formosa to account. But the group was told by state and federal agencies that the plastic pollution was harmless. A Formosa spokesperson was more direct, insisting that the company had “not spilled a single pellet” (Diane Wilson, interview by Fax Bahr, Texas, August 25, 2020).

Between January 2016 and March 2019, Wilson, Jurasek, Hamrick and others who joined the work collected over 2,500 samples (). They also took thousands of photos and videos. Jace Tunnel, a contracted expert for marine plastics later estimated that in the two and half year span of data collection, Formosa had released over 67 billion pellets (Diane Wilson, interview by Fax Bahr, Texas, August 25, 2020).

Figure 6 Approximately 2500 samples collected as evidence for the Waterkeeper's suit, spread out on land around Diane Wilson's house. March 2019. Figure by San Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeeper, reproduced with permission.Footnote7

There is much more to the backstory of the Waterkeeper suit, however. Turning pellets into evidence became possible through years of work to turn plastics into a problem (). Reports documenting plastic pellet pollution and their ingestion by fish and birds were first published in the 1970s (Baltz and Morejohn Citation1977; Carpenter et al. Citation1972; Carpenter and Smith Jr Citation1972; Colton Jr et al. Citation1974; Gregory Citation1977). Since then, plastic pellets have been found in water and along shorelines around the world. Growing bodies of research show that microplastics can be passed up the food chain, acting as “vectors” for other pollutants. Levels of persistent organic pollutants, for example, can be more than a hundred times higher in plastic pellets than in surrounding seawater (Rochman et al. Citation2013; UN Environmental Programme Citation2015). Today, plastic—and pellets especially—are recognized as a complex, global problem associated with plastics production, transport, use, recycling and waste. While there is currently no plastic-related legislation in the United States (Morath et al. Citation2021), important steps have been taken to advance a global plastics treaty with high promise.Footnote8

Figure 7 Waterkeeper Ronnie Hamrick collecting plastic pellets (left), sample of pellets (middle), and handwritten report (right) in 2019. Photographs by Diane Wilson, reproduced with permission.

The making of the Waterkeeper’s lawsuit thus depended on the extraordinary labor and creativity of the Waterkeeper themselves. It also depended on work of other kinds, in other places, with sometimes hard to see connections. Plastics science was key, as was work to make citizens suits an option in the US legal system, and work to build capacity in public interest law. Legal action is thus a juncture in a relay—a long game with many turns, before, during and after the law.

4 Labors of law: Reconvening the State

In 2017, Diane Wilson, Dale Jurasek, and Ronnie Hamrick—organized as the San Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeepers—filed a landmark citizens lawsuit against Formosa, bringing literally buckets of evidence forward, supporting allegations of rampant and illegal discharge of plastic pellets and other pollutants into Lavaca Bay from Formosa’s Calhoun County plant. Internal company emailsFootnote9 revealed that Formosa had known about the nurdle discharge since at least 2016, and that state and regulatory agencies gave advance notice before visiting the plant for inspections (Morath et al. Citation2021: 42; Sullivan Citation2020). The case was led by Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, who was not, at the outset, experienced in environmental law. They were Immigration lawyers. Diane convinced them to take the case nonetheless. As a result, they won the largest settlement of a Clean Water Act suit filed by private individuals in history (Suman and Schade Citation2021).

Legal scholars Suman and Schade (Citation2021) argue that the case is unique due to the voluntary collection and presentation of a large quantity of evidence collected over an extended period of time that was accepted by both the judge and defendants without objections since neither the defendant nor “competent authorities” could provide competing evidence. The Waterkeepers collection and presentation of pollution data thus filled an “enforcement gap” (Suman and Schade Citation2021: 3). While noting the peculiarities of the US legal system that enables citizen lawsuits, Suman and Schade also argue that the Waterkeeper’s case could inspire monitoring activities in environmental justice communities around the world, helping shift how citizen science can be used as evidence.

We concur that the Waterkeeper’s legal win demonstrates the potential of law, and particularly citizens suits, in environmental governance, countering long-running cynicism about the role of the law and state writ large in redressing problems largely of their own making. But there is even more at stake than the expansion of evidence that can be used in law. The Waterkeepers filed their suit to counter Formosa’s pollution. They also filed the suit to counter failures of “the state” (operating at many scales) to stop Formosa and other polluters in the region from causing environmental harm. For decades, the state (in its many manifestations) has been largely absent from Calhoun County as a protector of the environment and environmental health—despite the many state agencies in the mix.

In such a context, citizen suits have special power because they are both in and slightly beyond the bounds of law, both of and beyond the state. That is, through citizen suits, non-state actors can use state mechanisms to hold the state to account for failing to do its job, compelling the state to reconvene itself as such, reorganized from below. This depends on sustained data collection, curation and presentation, and the infrastructure needed to support this. There are long backstories that need to be built—bodies of evidence, analysis and interpretation—that must be brought to bear in work to turn “the state” around. There is also much work ahead to realize the law’s promise.

The law can thus be seen as a means to reorganize the social field, a juncture where things can turn rather than an end in itself. Such junctures create great opportunities for change, even though—even because—they are underdetermined: they must be worked out. Just transition—in Calhoun County and elsewhere—will depend on many such junctures and on the many kinds of labor needed to read and respond to resulting shifts. Environmental advocates need to be ready, looking both back and ahead.

4.1 Law’s Under-Articulation

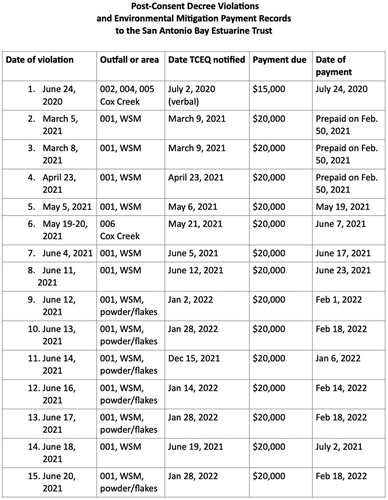

The Waterkeeper’s lawsuit was settled quickly, with clear benefits to Calhoun County’s people and environment. The “political action” that enabled this legal win, however, was and will be much more extensive in time. Years of work laid ground for the lawsuit. Much remains to be worked out in the years ahead. The judge’s ruling in the Waterkeeper’s case was thus definitive, but also not. The consent decree mandates zero discharge of plastic pellets from the Formosa plant, funds for on-going monitoring and significant fines for any breaches, for example. And the Waterkeepers are watching, organized as a “Nurdle Patrol” associated with the University of Texas’s Mission-Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve, which coordinates Nurdle Patrols around the world (Venable Citation2020). By the spring of 2022, three years after the ruling, over 200 infractions had been reported, with more than $5 million in fines ().

Figure 8 The San Antonio Bay Waterkeepers continue to track Formosa’s violations of the zero-discharge agreement through water monitoring at the Texas facility's different outfalls. As of spring 2022, the group has recorded over 230 violations. Matagorda Bay Mitigation Trust, “Post Decree Violations (Chronological)”, contributed by Tim Schütz, Project: Formosa Plastics Global Archive, Disaster STS Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, last modified 2 September 2023, accessed 2 September 2023. https://disaster-sts-network.org/content/post-decree-violations-chronological.

The consent decree also designates funds for the following, in addition to the $20 million for creating a fishing cooperative: $10 million for environmental development of Green Lake, a tidal lake on the Guadalupe River to be turned into an “environmentally sound public park”; $2 million to control erosion and restore beaches at Magnolia Beach in Calhoun County; $5 million for environmental research focused on San Antonio and Matagorda bay systems and the river deltas that feed into them; $750,000 to the YMCA in Calhoun County “for camps for children to study and learn how to be good stewards of the local marine environment” (Gibbons Citation2019).

These important, open-ended programs are barely spelled out, however, serving less as guarantees than as openings to new terrains of political struggle. The directive to rebuild the local fishing industry is a short paragraph in length and competing interests (commercial vs sport fishing) are still vying for territory; the work of figuring out what a sustainable fishing industry actually looks like still lies ahead. And there are many confounding factors—legacy pollution at risk of being reactivated (from the Alcoa Superfund site), ongoing (largely legal) daily pollution in huge quantities from many industrial operations in the region, extreme weather and warming seas. The quick and definitive legal decision in the Waterkeeper case is thus less and endpoint than a flashpoint, a definitive moment in a relay, with much work ahead and behind.

5 After the Law

Calhoun County is no stranger to the vagaries and violences of major shifts in its political economy, and to the need to completely reconfigure itself in response. The region endured extensive infrastructural devastation during the US Civil War, peripheralization during the railroad era, and proletarianization with mid-twentieth century industrialization. In short, the county has “built back” many times before. Each time, there was an underdetermined horizon of opportunity, a chance to radically reconfigure. Unfortunately—due to dynamics largely beyond local control—this history has been one of increasing harm to local environments, economies and health. As a result, it builds back today on contaminated, unstable ground, like much of the US Gulf Coast, like many other coastal regions of the world. Many environmental advocates argue that more regional approaches are needed, working against decision making processes that evaluate one hazard or problem at a time, discounting their interrelation. Environmental advocates are also rebuilding transnational solidarities, recognizing that action in one place has boomerang effects on others. Diane Wilson’s work is again exemplary.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, Wilson learned the language and how to work alongside organized labor, working especially closely with Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers (OCAW). OCAW dissolved in 1999, in the wake of a 50% membership loss resulting both from refinery closures and concerted union busting. In 2012, Wilson became a Waterkeeper, joining over 300 waterkeepers in almost 50 countries, many also struggling against rural isolation.Footnote10 More recently (around 2019), Wilson learned the language and joined the work of the anti-plastics movement. Referring to plastics as “the new coal” (Beyond Plastics Citation2021), cross-generational alliances of environmental activists are now working together on issues that were dealt with quite separately just a few years ago (ocean garbage and production of basic petrochemicals, for example). Working with a wide array of data types (company financial records and community air monitoring data, for example), knowledge infrastructures (government datasets and community archives, for example), and organizations (museums and schools, for example), plastics activists are developing new ways of understanding, visualizing, and collectively representing next-generation environmental problems. The anti-plastics movement has given Wilson both a new language and new connections—beyond those she built over the years working against the “the petrochemical industry.” In Seadrift, it helps draw out connections between Formosa and Union Carbide It also situates Seadrift globally, alongside other Formosa communities, in the path of the massive surge in plastics production expected in coming years, fueled by shale gas.

Today, in the lead role she plays as steward of the Formosa settlement, Wilson is shape-shifting again, learning how economic cooperatives work by building alliances with Black farmer collectives in the US South, working closely with coastal scientists, continuing her work with lawyers. She’s learning what coastal economies can become, and what challenges they face. The pushback against just transition and environmental justice is constant.

It was only a few months after the Formosa settlement that Diane Wilson learned that the Port of Calhoun was poised for expansion to support oil exports stemming from the shale boom. Expanding the Port of Calhoun could have had terrible boomerang effects. Retrofitting the port to receive large oil tankers would require dredging of the bay in which the port is nestled, which could reactivate extensive mercury contamination from the now-closed Alcoa aluminum refinery, left to settle over the last two decades. Just as the bay is recovering and funds are available to rebuild infrastructure for local fishers, the health of the bay was threatened anew.Footnote11 Changes in law opened the way for this.Footnote12

In 2015, lobbied by organizations like the Independent Petroleum Association of America, the Obama-Biden administration lifted a limit on American petroleum exports in place since the 1970s. That same year, plans to expand the Port of Calhoun County intensified through a partnership with Max Midstream, a newly incorporated pipeline and shipping company (owned by a real estate developer in Houston and a financier in London). Planned expansion would link the port to pipelines connected to the Permian Basin and Eagle Ford shale fields in west Texas, increase oil storage capacity, and deepen the port enough to accommodate Suezmax oil tankers, enabling oil exports to Europe and East Asia.

Wilson fought back in multiple directions. She went on a 40-day hunger strike at the bay outside the Alcoa and Formosa plants. She laid in a coffin outside the offices of the US Army Corps of Engineers in Galveston, and was arrested for “obstructing a highway or passageway” (Rogers Citation2021). Working with the Texas Campaign for the Environment and Earthworks, Wilson also filed a lawsuit against the Army Corps of Engineers, leading the agency to withdraw their environmental impact statement of the port extension. Studies funded by the Formosa settlement supported the lawsuit, which led to a withdrawal of the Army Corps in December, agreeing that more studies are needed (Montagna et al. Citation2021). At a celebration event in January 2023, spokespeople of the Calhoun Port Authority criticized the outcome of the lawsuit as a missed opportunity for economic development (Bertucci Citation2023a; Weisbrod Citation2022). By June 2023, the decision had been overturned, as the Army Corps announced a $2.8 million effort to test the seabed and remove contamination so that the project can proceed (Baddour Citation2023). In parallel, the Waterkeepers continued to challenge an air permit issued by TCEQ (Bertucci Citation2023b) and highlight the dredging project’s impact on endangered turtles (Bayrak Citation2022) ( and ).

Figure 9 Diane Wilson on the tenth day of her hunger strike in April 2021. Photo by Diane Wilson, reproduced with permission.

Figure 10 Diane Wilson in the coffin she set up at the Galveston, Texas office of the US Army Corps of Engineers (Rogers Citation2021). Photo by Diane Wilson, reproduced with permission.

5.1 Law in Relay

“Moreover, from the moment a theory moves into its proper domain, it begins to encounter obstacles, walls, and blockages which require its relay by another type of discourse (it is through this other discourse that it eventually passes to a different domain). Practice is a set of relays from one theoretical point to another, and theory is a relay from one practice to another. No theory can develop without eventually encountering a wall, and practice is necessary for piercing this wall” (Deleuze and Foucault Citation1977: 205).

In the years since, critiques of law have continued to gain coherence, dimensionality and force. Activists often point to ways involvement in lawsuits can fracture and stall social movements. Others argue that law, too often, takes too long, stretching the capacities of plaintiffs beyond reason.Footnote14 Leading environmental justice theorist David Pellow builds from analyses of racial capitalism to argue that “meaningful environmental justice will rarely be achieved through state-sanctioned means” (Pellow Citation2020: 298).

But such totalizing statements paint the state and the law as more stable and self-contained than they are revealed to be in practice. The state achieves its reality through a dispersed set of techniques, practices, agents, and procedures of governance (Ferguson and Gupta Citation2002), which must be coordinated in space and time in order to engender its “structural effects” (Mitchell Citation1991). The law, then, can be seen as an important means—one among many—through which this coordination is negotiated and enacted (Benda-Beckmann et al. Citation2009).Footnote15 As such the law and the state are neither inherently prone to domination nor capable, in themselves, of engendering or ensuring just transitions, or social justice more generally. Instead, just-transition advocates must be able to adapt their strategies of engagement with the state—whether through the law or otherwise—in response to the particularities of the state’s current configuration. Resisting Formosa within an authoritarian state like Vietnam, for example, must work against the overbearing coherence of the state (Ortmann Citation2023). Resistance in more neoliberal settings like Calhoun County, Texas, by contrast, calls for regrouping of state authority to force its hand.

In the United States, citizen suits are one way the state can be forced to reconvene itself, but realizing this potential will require especially extensive strategizing and coordination. Akbar et al. (Citation2021) point to this in contrasting traditional approaches to law and social movements with “movement law,” which includes deeply collaborative engagements with grassroots organizations. A keen if implicit insight here is that law’s instability and indeterminacy can become a strategic advantage, opening it to redesign and repurposing. Far from standing over society and nature, the law is seen as an open and embedded/re-embeddable system among other (socio-technical-ecological) systems. Further, these scholars also note that it’s not so much what happens within the domain of law itself that makes the law powerful. Rather, the law can only take its effect based on if, when, how, and what kind of connections are brought into and made throughout the legal process, in addition to those enabled by legal outcomes. Or, to put this differently, it’s not what “the law” does so much as what is done with it or through it, in addition to what is done before and after. As such, a legal victory is by no means a shelter; it is, rather, a point of passage in a law-politics relay. Any legal outcome is an anti-structural moment of division and rearticulation, the political outcomes of which are as determined by the conditions that brought the relay about as much as the labors of law that follow from it. The Waterkeepers case demonstrates this well.

In our view, then, the Waterkeeper’s historic legal win in 2019 is best seen as a “flashpoint” between decades of civic science and activism, and the many lines of ensuing work that the settlement funds will support. As Gilles Deleuze describes in the quote above, law is best understood in the movement from “theory” (law’s pronouncement) to practice, hitting walls, becoming something new as it plays out in the world. While none of the ecological restoration work would be possible without the court’s decision, lived outcomes for the people of Calhoun County are well beyond the court’s domain of control. This can be understood through speech act theory’s distinction between “illocutionary” acts that necessarily happen with their pronouncement (i.e. the reveal of winners and losers) and “perlocutionary” acts that only have a potential to take effect (i.e. transformation/recovery of the local economy/ecology) (Austin Citation1962). With this distinction, law has to be recognized as under-determined and “up for grabs.” Investing in law—and the state writ large—is thus not an investment in the state and law as we know it. It is an investment in the remaking of law and the state from below.

6 Law, Environmental Advocacy and Late Industrialism

The Waterkeeper’s win was remarkably quick. It was filed and settled within two years. It was also years in the making and will involve much work ahead. And it was successful for a tangle of reasons beyond the lawsuit, narrowly conceived. Further, the end isn’t simple monetary payouts but complex environmental monitoring, restoration, and educational programming, the details of which are specified in the legal consent decree with not much more than a paragraph.

The Waterkeeper’s win illustrates the extensive work required before and after the fact of a legal decision, and that the modes of organizing that served as the citizen suit’s conditions of possibility are different from the as-yet underdeveloped modes of organizing that will be necessary to carry the lawsuit’s promise. The Waterkeeper’s suit, like legal victories more generally, is but a moment of passage, akin to that precarious moment of any relay in passing of the baton, a time of dis-and-rearticulation. This way of thinking about law is especially relevant in work toward just transitions, recognizing that just transition shouldn’t be thought of as achieved by reaching a specific endpoint (decarbonizing a region’s grid while protecting jobs, for example) (Adams Citation2023). Instead, just transition can be thought of as requiring changes in many types of systems (technical, atmospheric, social, political, legal, discursive, etc.), working at many different scales, through the coordination of diversely positioned people. Environmental advocates, and the knowledge infrastructures they rely on, need to be ready for this.

Importantly, the goal is not corrective or restorative—building things back to where they were before injury.Footnote16 The goal is economic and social transformation—which cannot be fully articulated in advance. Just transition, as is often said in the labor movement, is a long game—a very long game, deeply weighted by both the past and wickedly complex contemporary contexts—calling for modes of advocacy ready to shift shape and direction, recognizing the tangle of systems, scales and contradiction it is caught within. Law can be a powerful even if indeterminate tool.

The cross-issue, cross-scale coordination challenges of just transition are immense, as are the ever-shifting terrains that advocates must move through. Legal action is one tactic among many, especially powerful in its potential capacity—in this case, through a citizen science supported citizen suit—to reconvene the State, countering its neoliberal dispersion.

A late industrial frame—especially if developed ethnographically, can help characterize the contexts and challenges of just transitions—and the many different ways just transition is envisioned and pursued. Calhoun County illustrates this well.

Calhoun County is replete with both legacy and on-going pollution, which is hard to measure but formative; commercial interests overdetermine governance; the frames and techniques of government actors (Environmental Impact Statements, for example) splinter the problem space, deflect concern about the public good and practically enable inertia and irresponsibility; what the state has accomplished (settling the mercury pollution in Matagorda Bay, for example) is itself at risk, undermined by the continuing force of petro-capital (refueled by the shale gas boom); for different reasons, many people in Calhoun County share deep cynicism about “the state” and other forms of collective action; possibilities for governance from below are hard to envision much less strategize; youth have no place to go, at home or elsewhere.

Plans to expand and dredge the Calhoun County Port demonstrate an important late industrial dynamic: As state-led environmental programs passed in the 1960s and 1970s age, their successes are both resoundingly clear, and doubling back, exposing contradictions and incapacity. To some extent this can be explained as quintessentially neoliberal, with the state excusing itself from governance while quietly protecting private and corporate interests. But, contrary to the neoliberal dictum refusing to “pick winners and losers,” the state is not protecting all industries equally: the petrochemical facilities have taken precedence, undermining others (like the fishing industry).

Calhoun County also points to ways neoliberalism mutates in different times and places, continually reconstituting itself in order to survive (Callison and Manfredi Citation2020).Footnote17 This means that environmental advocates don’t just need to understand and counter neoliberalism as a static phenomena; they must constantly re-read neoliberalism as it changes. The dynamics of late industrialism furthers the volatility, keeping environmental advocates on the run, tuned to tangles of issues at the same time.

In Calhoun County, as in many other regions of the world, the intersections that produce environmental injustice have multiplied and tightened, asking for much more of governance than presently conceptualized, much less practiced. Like the fishing docks in Seadrift, Calhoun County will have to be rebuilt, with fundamentally new organizing principles. Environmental advocates like Diane Wilson will lead the way. Researchers like us need to provide scaffolding.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (https://doi.org/10.1080/18752160.2023.2291964)

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

James Adams

James Adams earned his PhD from the Department of Anthropology at the University of California Irvine (UCI) and is also a member of UCI’s EcoGovLab. His research and teaching focus on current debates in energy and environmental ethics, experimental ethnography, and the politics of knowledge production. Adams’s research examines the multi-scalar dynamics of sociotechnical change and considers their implications for developing more just and effective modes of environmental and energy governance. His publications include “Knowledge infrastructure and research agendas for quotidian Anthropocenes” (2021), “Petroghosts and Just Transitions” (2021), and “What is Energy Literacy?” (2022). Adams’s current book project, The Transition is Out of Joint: On Petro-Racial Capitalism and Renewable Energy Transition in Austin, Texas, shows how sedimented histories of racial exclusion and petro-capitalist development continue to haunt Austin’s renewable energy transition.

Tim Schütz

Tim Schütz is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology and a member of EcoGovLab at the University of California, Irvine. His research and teaching focus on ways data is mobilized for different purposes in different settings—across scientific fields, as evidence in legal cases, and as shared points of references in social movements. Schütz both studies and helps build public knowledge infrastructure, working with advocacy organizations, museums, public libraries, and other creative data practitioners. Recent publications include “Archiving for the Anthropocene: Notes from the Field Campus” (2019), Visualizing Taiwan’s Formosa Plastics, and “Knowledge Infrastructure and Research Agendas for Quotidian Anthropocenes: Critical localism with Planetary Scope” (2021).

Kim Fortun

Kim Fortun is a professor in the Department of Anthropology and director of EcoGovLab at the University of California Irvine. Her research and teaching focus on environmental injustice and governance, experimental ethnography, and the poetics and politics of knowledge infrastructure. Fortun’s publications include Advocacy After Bhopal Environmentalism, Disaster, New Global Orders (2001), “Ethnography in Late Industrialism” (2012) and “Cultural Analysis in/of the Anthropocene” (2021). Fortun’s current research includes a study of environmental injustice in Santa Ana, California; a study and archive focused on the operations of Formosa Plastics Corporation (collaborating with a global network of environmental researchers and activists); and a collaboration with environmental justice educators to build teaching and learning capacity across borders, linking K-12 schools, universities, community-based organizations, and government agencies. Fortun is the lead instructor for UCI Anthro 25A, “Environmental Injustice,” a large, general education course that extends from EcoGovLab research.

Notes

1 See the Matagorda Bay Mitigation Trust’s (2020) summary of the fishing cooperative contract.

2 United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas Victoria Division, "Final Consent Decree 2019.11.27", contributed by Tim Schütz, Project: Formosa Plastics Global Archive, Disaster STS Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, last modified 4 September 2023, accessed 4 September 2023. https://disaster-sts-network.org/content/final-consent-decree-20191127

3 See “Analyzing Formosa Plastics”, contributed by Tim Schütz, Disaster STS Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, accessed 30 August 2023. https://disaster-sts-network.org/structured-analytics-questions-set/analyzing-formosa-plastics

4 Stevis (Citation2021) goes on to explain that “[a] number of analysts have sought to separate out different types of just transitions. (Sweeney and Treat 2018) differentiate between social dialogue and social power approaches. Paul Hampton (2015) distinguishes between neoliberal, ecological modernization and Marxist/socialist approaches. The Just Transition Research Collaborative (2018) employed similar end points but sought to discriminate between reforms whose aim is to manage and stabilize the existing order—in this case, neoliberalism—and structural reforms, or revolutionary reforms in Luxemburg’s language (O’Brien 2021), and non-reformist reforms in Andre Gorz’s language (Gorz 1967; Bond 2008), which are part of a ‘war of position’ towards more profound change? (Stevis Citation2021: 252).

5 Currently, Karankawa further down the coast (in Ingleside, near Corpus Christi) are suing the US Army Corps of Engineers for granting a dredging permit to Enbridge, Inc., a multinational pipeline company also at the center of high-profile Indigenous-led pipeline protests – known as the Stop Line 3 protests – in Minnesota, on the US-Canadian border (Karankawas 2022). The dredging permit on Karankawa territory would allow Enbridge to build an oil export terminal, tapping the new abundance of oil available from West Texas. Diane Wilson’s activism has also become an important referent in Karankawa organizing.

6 See: Victoria Advocate, “News Article: Texas Tops U.S. in Industrial Air Pollution 06.20.1989”, contributed by Tim Schütz, Project: Formosa Plastics Global Archive, Disaster STS Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, last modified 26 June 2023, accessed 2 September 2023. https://disaster-sts-network.org/content/news-article-texas-tops-us-industrial-air-pollution-06201989

7 See Diane Wilson, "Clean Water Suit Samples, 2019", contributed by Tim Schütz, Project: Formosa Plastics Global Archive, Disaster STS Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, last modified 2 September 2023, accessed 2 September 2023. https://disaster-sts-network.org/content/clean-water-suit-samples-2019

8 In March 2022, representatives from 175 countries endorsed a resolution at the United Nations Environment Assembly (“UNEA-5”) in Nairobi to negotiate an international legally binding agreement to “end plastic pollution” by the end of 2024. The UNEA Resolution itself is the result of years of work across geographic and issue boundaries. There’s also much work ahead to work out the details, push through to a binding agreement, then figure out what a binding agreement looks like in practice, across very diverse settings (Farrelly et al. Citation2021).

9 See for example Formosa Plastics Corporation Texas, "Traffic Pellet/Powder and Misc. Observations, February 26, 2016", contributed by Tim Schütz, Project: Formosa Plastics Global Archive, Disaster STS Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, last modified 30 August 2023, accessed 30 August 2023. https://disaster-sts-network.org/content/traffic-pelletpowder-and-misc-observations-februrary-26-2016.

10 See https://waterkeeper.org/

11 As described earlier, Seadrift’s Lavaca Bay is one of the nation’s largest and most toxic Superfund sites, created by the operations of a now-closed Alcoa aluminum refinery, which released an estimated 1.2 million pounds of mercury into the Bay in the late 1960s and 1970s.

12 Plans to expand and dredge the Calhoun County Port demonstrate an important late industrial dynamic: As state-led environmental programs passed in the 1960s and 1970s age, their successes are both resoundingly clear, and doubling back, exposing contradictions and incapacity. The intersectionalities of environmental injustice have multiplied and tightened, producing tangles of issues to contend with all at once, asking for much more of governance than presently conceptualized, much less practiced.

13 In a related vein, at the same time, legal scholar and critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw articulated the concept of “intersectionality” – which has proven central to environmental justice scholarship in recent years (while also prompting shrill criticism from US conservatives). Journalist Jane Coaston (2019) explains that “when Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term 30 years ago, it was a relatively obscure legal concept. Then it went viral”.

14 In much of environmental law, time is further implicated and complicated because of the slow processes through which toxic exposures take their deleterious effects, troubling the singular time-stamp of “consent” (Ottinger 2013).

15 “Law is a powerful tool that is constantly in the making and that is used in a variety of ways by different social actors to create frameworks for the exercise of power and control over people and resources on varying scales” (Benda-Beckmann et al. Citation2009: 4).

16 Tort law has long been critiqued by critical (especially by Marxist) analysts for its restorative logic – which assumes that previous conditions were just (Abel Citation1981).

17 Slobodian and Plehwe examine how “[n]eoliberal thought—like all genres of political thought— is subject to processes of constant bifurcation and recombination. … If we understand neoliberalism as embodying less a credo than an injunction—to defend capitalism against democracy—then mutations should be expected. Prescriptions change with the threat. Following the form they take at any given time requires scholarly vigilance and attention to detail” (Slobodian and Plehwe 2020: 105)

References

- Abel, Richard L. 1981. “A Critique of American Tort Law.” British Journal of Law and Society 8 (2): 199–231. https://doi.org/10.2307/1409721.

- Adams, James Robert. 2023. “The Transition Is Out of Joint: On Petro-Racial Capitalism and Renewable Energy Transition in Austin, Texas.” UC Irvine. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6j44(1bg).

- Adams, James, and Kim Fortun. 2021. “Petro-Ghosts and Just Transitions.” Public Books (blog). June 8, 2021. https://www.publicbooks.org/petro-ghosts-and-just-transitions.

- Adams, James, Alison Kenner, Briana Leone, Andrew Rosenthal, Morgan Sarao, and Taeya Boi-Doku. 2022. “What Is Energy Literacy? Responding to Vulnerability in Philadelphia’s Energy Ecologies.” Energy Research & Social Science 91 (September): 102718. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2022.102718

- Ahmann, Chloe. 2020. “Atmospheric Coalitions: Shifting the Middle in Late Industrial Baltimore.” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 6 (November): 462–485. doi:10.17351/ests2020.421

- Ahmann, Chloe, and Alison Kenner. 2020. “Breathing Late Industrialism.” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 6 (November): 416–438. doi:10.17351/ests2020.673

- Akbar, Amna A., Sameer M. Ashar, and Jocelyn Simonson. 2021. “Movement Law.” Stanford Law Review 73 (4), https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3735538.

- Alcoa. 2023. “Our History.” 2023. https://www.alcoa.com/global/en/who-we-are/history.

- Ariztia, Tomas, Aline Bravo, and Ignacio Nuñez. 2023. “Baroque Tools for Climate Action. What Do We Learn from a Catalogue of Local Technologies?” Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society 6 (1): 2141015. doi:10.1080/25729861.2022.2141015

- Austin, J. L. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. The William James Lectures 1955. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Baddour, Dylan. 2023. “Determined to Forge Ahead With Canal Expansion, Army Corps Unveils Testing Plan for Contaminants in Matagorda Bay in Texas.” Inside Climate News (blog). June 8, 2023. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/08062023/texas-matagorda-bay-testing/.

- Baltz, Donald M., and G. Victor Morejohn. 1977. “Food Habits and Niche Overlap of Seabirds Wintering on Monterey Bay, California.” The Auk 94 (3): 526–543.

- Bang, Molly. 2000. Nobody Particular: One Woman’s Fight to Save the Bays. 1st ed. New York: Henry Holt and Co.

- Baxi, Upendra, and Amita Dhanda. 1990. Valiant Victims and Lethal Litigation: The Bhopal Case. Bombay: N.M. Tripathi.

- Bayrak, Saliha. 2022. “The Little Turtles That Could: 45 Endangered Sea Turtles Hatch in Texas.” Texas Monthly. June 28, 2022. https://www.texasmonthly.com/travel/45-kemps-ridley-turtles-hatch-in-texas.

- Benda-Beckmann, Franz von, Keebet von Benda-Beckmann, and Anne M. O. Griffiths, eds. 2009. Spatializing Law: An Anthropological Geography of Law in Society. Law, Justice, and Power. Farnham, Surrey, England . Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Bertucci, Leo. 2023a. “Environmentalists Celebrate Legal Victory in Point Comfort, Expansion Supporters Frustrated.” The Victoria Advocate. January 25, 2023. https://www.victoriaadvocate.com/news/environment/environmentalists-celebrate-legal-victory-in-point-comfort-expansion-supporters-frustrated/article_ac307ee6-9b65-11ed-bfc5-43161549b337.html.

- Bertucci, Leo. 2023b. “Plaintiffs in TCEQ Air Permit Lawsuit File Initial Brief.” The Victoria Advocate. July 21, 2023. https://www.victoriaadvocate.com/news/plaintiffs-in-tceq-air-permit-lawsuit-file-initial-brief/article_e4c2c932-25b5-11ee-ba0c-137c8cc41397.html.

- Beyond Plastics. 2021. “REPORT: The New Coal: Plastics & Climate Change — Beyond Plastics - Working To End Single-Use Plastic Pollution.” 2021. https://www.beyondplastics.org/plastics-and-climate.

- Boudia, Soraya, Angela N. H. Creager, Scott Frickel, Emmanuel Henry, Nathalie Jas, Carsten Reinhardt, and Jody A. Roberts. 2021. Residues: Thinking Through Chemical Environments. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Branco, Luciana Landgraf Castelo. 2023. “Rethinking Governance Through Samarco’s Dam Collapse in Brazil: A Critique from the STS Perspective.” Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society 6 (1): 2162708. doi:10.1080/25729861.2022.2162708

- Bruggers, James. 2023. “EPA Proposes New Emissions Rules at Chemical and Plastics Plants.” Undark Magazine. April 11, 2023. https://undark.org/2023/04/11/epa-proposes-new-emissions-rules-at-chemical-and-plastics-plants/.

- Byman, Daniel. 2022. Spreading Hate: The Global Rise of White Supremacist Terrorism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Cahalan, Rose. 2019. “‘Seadrift’ Dredges Up a Little-Known—and Deeply Disturbing—Texas Story.” “Seadrift” Dredges Up a Little-Known—and Deeply Disturbing—Texas Story - The Texas Observer. August 5, 2019. https://www.texasobserver.org/seadrift-dredges-up-a-little-known-and-deeply-disturbing-texas-story.

- Calhoun Port Authority. 2023. “Calhoun Port Authority.” 2023. http://www.calhounport.com/.

- Callison, William, and Zachary Manfredi. 2020. Mutant Neoliberalism Market Rule and Political Rupture. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Carpenter, Edward J., Susan J. Anderson, George R. Harvey, Helen P. Miklas, and Bradford B. Peck. 1972. “Polystyrene Spherules in Coastal Waters.” Science 178 (4062): 749–750. doi:10.1126/science.178.4062.749