ABSTRACT

Contemporary immigration from Pakistan to the UK often takes the form of marriage migration, as substantial numbers of British men and women of Pakistani ethnicity marry partners from Pakistan. Drawing on quantitative and qualitative evidence, this paper explores experiences of Pakistani men migrating to the UK through marriage, revealing a complex of social and economic pressures in the early months and years post-migration, here referred to as the ‘Mangetar Trap’. Migration can have contradictory implications for masculinity – presenting both opportunities and challenges for gendered aspirations. The existing research literature reveals instances of migrant men using the former to compensate for the latter. For some recently arrived Pakistani migrant husbands in Britain, however, particular combinations of socio-economic position, time poverty, social marginalisation and family relationships can constrain their available options. In the longer term, such men may find routes to improving their situations, but exploration of these early constraints is valuable in cautioning against an over-emphasis on agency in research on migrant masculinity.

Introduction

In the emerging literature on migrant masculinities, migration commonly features as presenting challenges for migrant men's gendered (and classed) aspirations. Recent research has documented ways in which migrant men draw on various resources to negotiate their new positions and enact and project a successful masculinity. The majority of such research, however, has focused on economic migrants (and to a lesser extent those arriving through processes of asylum). The experiences of men following or joining family members is much less frequently discussed, thanks to a widespread association of family migration with the movement of women as ‘dependents’. In this article, we explore the position of Pakistani men migrating to the UK as husbands of British Pakistani women. We suggest that at least initially, men in this position can face structural limitations constraining the resources on which they are able to draw in their negotiations of the gendered challenges of migration. In the longer term, such men may find routes to improving their situations, but exploration of these early constraints is valuable in cautioning against an over-emphasis on agency in research on migrant masculinities.

In the scholarship on masculinity and migration, as in masculinity studies more generally, Connell's notion of ‘hegemonic masculinity’ (Citation1987) is often a key reference point. The concept has been criticised for (among other things) creating unhelpful dualisms between ‘hegemonic’ and ‘subordinate’ forms of masculinity and so obscuring dynamism and dialogue; and paying insufficient attention to actual gendered practices (Howson, Citation2009; Lum, Citation2016). These critiques have led to attempts to reformulate the concept (e.g. Hearn, Blagojevic, & Harrison, Citation2013), and an appeal to refocus from masculinity to men (Hearn, Citation2004). Nevertheless, the notion of dominant ideals of masculinity, understood as varying between cultural settings and therefore brought into encounter in the migration context, has become a cornerstone of analysis in the field of masculinity and migration. A key question has thus become how migrant men ‘identify with and contest these idealised masculinities’ (Lum, Citation2016, p. 32).

Whilst hegemonic masculinities are always a matter of aspiration rather than material practice (Howson, Citation2009), migration involves at least some degree of dislocation from the cultural and social contexts in which such ideals and practices are generated (Pease, Citation2009). It can also dislocate migrants from the ‘hegemony of men’ (Howson, Citation2013), and is commonly associated with loss of status and power.Footnote1 Work and family appear key domains in which tensions around masculine aspirations arise. The downward mobility common in migration may mean accepting lower status employment (or indeed unemployment) in which low income can undermine ability to fulfil a breadwinner role. Migrant labour market niches often involve physically arduous work, and some (such as the care sector) may be construed as feminine and therefore emasculating (McGregor, Citation2007). Where wives have also migrated, domestic relations of power may be altered, with frequent accounts in the literature of men complaining that in (Western) countries of settlement, gendered employment opportunities, welfare arrangements and social contexts mean that women ‘wear the trousers’ (e.g. Pasura, Citation2008; Pease, Citation2009). For migrant husbands following wives on dependent visas, or joining non-migrant wives after transnational marriages, practical consequences and stigma can result from dependency on a spouse for their immigration status (Charsley, Citation2005; Charsley & Liversage, Citation2015; Gallo, Citation2006).

The available research documents migrant men's responses to such challenges. At worst, Walter, Bourgois, and Margarita Loinaz (Citation2004) for example, describe Mexican construction workers in the US unable to remit after injury who experience their situation as so shameful that they spiral into depression and substance abuse. Some may consider return or onward migration (e.g. Maroufof & Kouki, Citation2017). But in other accounts we find men drawing on various resources to navigate ways to recoup status, at least in the eyes of some audiences. Thus, George writes of the husbands of South Indian nurses in the US finding positions of authority in church hierarchies, whilst Gallo’s (Citation2006) work on migrants from the same part of India living in Italy shows men narrating their status as more favourable than that of irregular migrants from other parts of the subcontinent, and Chinese rural migrants experiencing urban low status may stress their fulfilment of the role of the ‘filial son’ supporting their parents (Lin, Citation2014). Research interviews themselves can provide opportunities for positive gendered self-narration (Charsley, Citation2013). Assessments of desirable masculinities can differ between ethnic majority and co-ethnic minority contexts (Donaldson, Hibbins, Howson, & Pease, Citation2009) providing opportunities for status at home or in the ‘community’ for men whose migrancy, ethnicity and/or race may be denigrated by others. Transnationalism, which not only connects but can enable at least partial separation of lives ‘here’ and ‘there’, can provide a further splitting of audiences. Men who scrape a living overseas may be able to remit money, or indulge in conspicuous consumption on (long saved for) visits, earning the esteem of those ‘back home’ (Singh, Citation2013) – although such displays need to be judiciously managed to avoid accusations of foolish imprudence (cf. Osella & Osella, Citation2000). Elsewhere, Charsley and Liversage (Citation2013) suggest that for some Muslim migrants to Europe transnational polygamy presents opportunity for alternative performances of valued masculinity away from the ignominies of migrant life.

In an important contribution to these debates, Batnitzky, McDowell, and Dyer (Citation2009) argue that migrant men may be ‘strategically flexible’ with their gendered identities if there is an acceptable ‘trade off’ in terms of other gains. Thus, accepting employment which challenges their (or their family's) previous aspirations, for example, may reap other benefits: cosmopolitan adventures for some middle class men, and the ability to financially support families for others. It is this territory – the ability to ‘trade off’ a desired status or identity in one arena for another – that we explore in our material on Pakistani men migrating to the UK through marriage.

Pakistani migrant husbands in the UK

In policy spheres in many Northern European countries, (particularly Muslim) women migrating for marriage have received considerable attention in recent years, perceived as vulnerable, but also as a source of integration problems including lack of local language fluency and low participation in the job market, together contributing to segregation of ethnic minority communities (Casey, Citation2016). At root lies the perception of Muslim minority populations as problematically patriarchal, part of a wider redefinition of multiculturalism as in tension with gender equality (Okin, Citation1999). This problem, as Roggeband and Verloo (Citation2007) suggest, ‘is principally located in men and a negative masculine culture’ (p. 272). And yet as ‘migrant men surface as a new target group … no concrete measures at all are formulated to stimulate their emancipation’, with migrant grooms in particular absent from policy discourses (Roggeband & Verloo, Citation2007, pp. 282–283). Instead, the problematically patriarchal Muslim man has become what Helma Lutz terms ‘a cherished dominant discursive figure which obscures a much more complicated portrayal of masculinity’ (Citation2010, p. 1653). Just as vulnerability may be challenging to the performance of hegemonic masculinity (Charsley & Liverage, Citation2015; Holland, Ramazanoglu, Sharpe, & Thomson, Citation1994), the creation of the caricature of the powerful Muslim patriarch rests on the concealment or at least neglect of vulnerabilities experienced by some Muslim men.

In this paper, we contribute both to the challenging of this dominant gendered discourse, and to the growing literature on masculinity and migration, through an exploration of the position of Pakistani Muslim men migrating to the UK as spouses of British Pakistani women. Whilst the majority of spouses migrating from Pakistan to Britain are women, since the late 1990s men have constituted a substantial proportion of Pakistani spousal settlement in the UK (in some years nearly half of grants of spousal settlement to Pakistani nationals). Building on Charsley's previous work in this area (e.g. Charsley, Citation2005; Charsley & Bolognani, Citation2017; Charsley & Wray, Citation2015), two recent research projects provide new quantitative and qualitative data with which to explore the position of Pakistani migrant husbands in the UK.

In particular, in order to further understandings of the challenges to gendered aspirations faced by migrant men, and their capacity to negotiate these dislocations, the paper examines the tensions between gendered aspirations or expectations and reported experiences of migration, focussing on issues of employment and extended families, including remittances and transnationalism. We concentrate on common areas of tension emerging in this research, without wishing to suggest that these are experienced universally or to the same degree by all migrant husbands entering the UK from Pakistan (which would be to replace one homogenising stereotype with another).

After a description of the data sources and methods, we present quantitative evidence from the Labour Force Survey, before discussing the qualitative data. In this latter section, we take a loosely chronological approach, beginning with pre-migration expectations, before exploring experiences in the first few years after arrival, and then turning to interview and focus group material from earlier migrants for indications of how positions may change over time. Whilst most of the discussion is focussed on migrant husbands’ experiences in the UK, the transnational context provides an important element in the form of flows of information shaping men's expectations of their migration, remittance aspirations, and the options facing those who find themselves at least initially subject to the pressures and constraints of what we refer to below as ‘the Mangetar Trap’.

Data and methods

This article draws together several rather diverse bodies of data. The Marriage Migration and Integration project,Footnote2 a collaboration between the Universities of Bristol and Oxford, is a mixed methods study focussed on two of largest ethnic groups involved in spousal immigration to the UK: British Pakistani Muslims (≈ ½ married to partner from overseas) and British Indian Sikhs (≈ ¼ married to partner from overseas) (Dale, Citation2008). It combines data from the UK Labour Force Survey (household files 2004–2014) and a set of nearly 80 semi-structured interviews. Supplementary interviews and focus groups were carried out to provide more information on underrepresented categories of participants.Footnote3 Both the qualitative and quantitative data allows comparison between intra-national couples (both UK born/raised), migrant wife couples, and migrant husband couples. For the purposes of this paper, the focus will be on Pakistani ethnicity migrant husband couples.Footnote4 From this research, we have interview data from ten couples involving migrant husbands from Pakistan and British Pakistani wives, and two focus groups with migrant Pakistani men.

The Pakistani-Muslim sample from the Labour Force Survey (hereafter LFS) contains 1,815 couples, of which 710 involve a migrant husband. It is limited to heterosexual partnerships in which both report Pakistani identity and Islam as religion. We included only couples in which at least one partner was either born in or migrated to the United Kingdom before the age of 18. As labour market participation falls sharply after the age of 50, the sample was restricted to couples in which both partners were below 50 at the time of the survey. Within this sample, the migrant husbands’ length of residence in the UK range from 0 to 31 years with an average of a little over 10 years. Respondents were 20–49 years old at the time of survey (35 on average) and arrived in the UK between 1974 and 2014 at an average age of 25.

Further work on the experiences of Pakistani migrant husbands was conducted in collaboration with QED-uk.org, a UK-based charity, aimed at assisting QED to develop new services for such men (as voluntary sector and policy initiatives focus on support for migrant wives). This small project involved structured interviews with twenty men in Pakistan applying for spouse visas to join British Pakistani wives. Participants were recruited and interviewed by QED staff in Gujerkhan and Mirpur, two common areas of origin for Pakistani migrant spouses.Footnote5 We then conducted two further focus groupsFootnote6 with migrant husbands in the Bradford area: one in which participants had arrived on spouse visas in the last 1–4 years, the other in which they had been in the country for at least 10 years. The rationale was to hear both about recent experiences and the early months and years after marriage and migration, but also how earlier migrants’ lives had developed in the longer term.

This paper draws primarily on these sets of recent data, but also on Charsley's ethnographic research since 1999 on Pakistan-UK transnational marriages. The discussion starts by summarising the key findings from the LFS as background information, before moving on to explore the qualitative material.Footnote7

Labour Force Survey data: employment and extended family living

The Labour Force Survey is the largest UK household survey. Although it lacks data on many issues of interests to migration scholars (remittances, visits to country of origin, social networksFootnote8), its substantial sample size and household format enable analysis of groups such as migrant Pakistani spouses who are either not identifiable or in insufficient numbers in other UK sources.Footnote9 As the title of the survey suggests, the focus is on employment, but the demographic information collected means it is also a source of information for educational characteristics and household living arrangements.

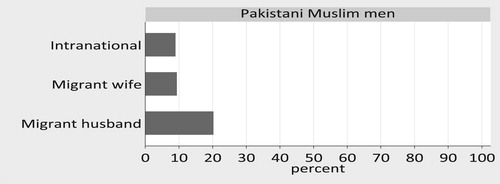

provides a comparison of levels of labour force participation by gender and couple type. Migrant husbands have high levels of employment for the ethnic group – actually higher than for British Pakistani men married to migrant wives. The other thing to notice is that British Pakistani women with migrant husbands have higher rates of employment than migrant wives – and when we looked at the ‘ever worked’ statistics, they were significantly less likely to have ‘never worked’ than British Pakistani women in intranational marriages. Financial requirements for sponsoring the immigration of a spouse encourage women to work, but our interview data also suggests that transnational marriage can fit with some British Pakistani women's desires to maintain close ties with their own family, and (for some) to pursue their own aspirations for education and employment (Charsley et al., Citation2016; cf Lievens, Citation1999).

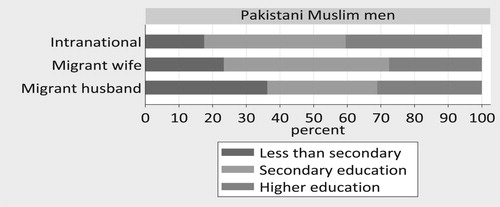

In , we see that migrant husbands are more likely than British Pakistani husbands to be in elementary or low skilled forms of employment. This is perhaps unsurprising given the lower educational profile presented in , but as education does not completely explain this effect, it is also likely to reflect labour market challenges commonly affecting migrants (lack of recognition of qualifications or experience, language issues, discrimination etc).

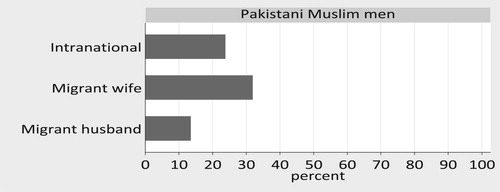

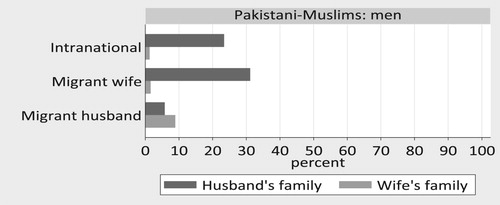

The other important piece of statistical context for the purposes of this discussion is on extended family living. In we see that migrant husbands do not have high levels of living in extended family households (according to the LFS definition). However, demonstrates that when migrant men do live in extended family households, these are more likely to be their wife's relatives than their own. Again, this may unsurprising given that their natal family is likely to remain overseas (although several men interviewed in Pakistan pre-migration had other relatives such as cousins or even brothers already resident in the UK). Levels of residence with the wife's family contrast, however, with the very low rates of uxorilocal residence among British Pakistanis in intranational marriages – the convention being that where joint living occurs, a wife will move to her husband's household rather than vice versa. Indeed the position of a son-in-law living with their wife's parents is stigmatised in many parts of South Asia, stereotyped as being under the thumb of his wife and in-laws (see Charsley, Citation2005; Kaur & Palriwala, Citation2014). Elsewhere, Charsley has explored the potentially weak position of the migrant ghar damad (house son-in-law) in domestic relations of power (Charsley, Citation2005; see also Chopra, Citation2009; Malik, Citation2010).

Extended families, employment and dual financial aspirations

The importance of family contexts and networks in understanding migration is increasingly recognised (Cooke, Citation2008), but is inescapable in the case of marriage migration. In scholarship on migration and masculinity, family and work emerge as interconnected and ambivalent domains in which migrant aspirations to hegemonic ideals of masculinity may be both supported (e.g. as breadwinner) and challenged (e.g. low income, altered domestic relations of power) (cf. Gonzalez-Allende, Citation2016). The couple has been the principle family relationship explored in this work, and with good cause – migration can lead to the nuclearisation of families geographically dislocated from wider kinship networks. Marriage migrants, however, tend to be brought into closer proximity to their spouse's family.

The LFS data shows under 15% of Pakistani migrant husbands living in extended family households, and just under 10% living with their wife's relatives. In our qualitative data, however, it is clear that many more experience forms of statistically ‘hidden’ extended family living, such as when the couple lives in a property close to the wife's family and shares activities such as cooking and shopping, as well as maintaining frequent social contact. Strikingly, even when they lived separately, all the migrant husbands in the Marriage Migration and Integration project sample were also dependent on their wife or her relatives for their accommodation (which was owned /rented by the wife/her relatives).

These affinal connections emerged as particularly significant in our qualitative data.

Expectations before migration

The interviews in Pakistan and focus groups in UK provide some insight into men's pre-migration expectations of life in the UK. Few of the participants (either those speaking before their migration, or those reflecting on their migration experiences) reported having anticipated significant challenges. Only five of the twenty interviewees in Pakistan reported having worries about migrating to the UK. Whilst the interviewees may have been downplaying their trepidation, the topics mentioned or absent in their response to this question are striking. Those who expressed concerns mentioned language issues, cultural difference, wanting their own house and challenges of living in a non-Islamic environment. None mentioned the issues of family relationships and employment that loomed large in the UK focus group and interview material. Significantly, one man explained his lack of concern as stemming from the presence of many relatives in the UK. The reassurance of family was likely a source of confidence for others in our research, as most were marrying within the extended kin-group, so that their mother- or father-in-law was usually one of their own parents’ siblings or cousins who they would have met during the British family's visits to Pakistan (very few had had the opportunity to visit the UK themselves prior to their marriage). Some also had other family members who had already migrated to the UK.Footnote10 They were therefore coming into what was likely expected to be a familiar and supportive context, rather than the dislocation from their pre-migration position in the ‘hegemony of men’ which has been suggested as a common consequence of migration.

In terms of employment, whilst some respondents in Pakistan mentioned the likelihood of (taxi) driving, those already working or pursuing professional or vocational training often expected to be able to continue in the same line of work after migration. Careers mentioned included graphic design, the law, and the civil service. In contrast, one recently arrived husband who had been a teacher in Pakistan and had been shocked at his restricted employment opportunities on arrival in the UK exclaimed rhetorically: ‘Here there is only one job – dishwashing’. The issue of long working hours and time poverty appeared in the pre-migration interviews in a diluted form when some men anticipated that they would have to work harder in Britain than they were used to in Pakistan.

All expected to remit to family in Pakistan on a regular or semi-regular basis. Not only is providing for parents an expected part of the role of good son (cf Malik, Citation2010; Singh, Citation2013), but the burden of remittance expectation is often high for men of this age, frequently with unmarried sisters living at home whose wedding costs could be substantial, and/or younger siblings’ education to finance. With both marriage and migration often moments in which adult responsibilities are shouldered, these expectations of providing for family in the UK and ‘back home’ come not only from the would-be recipients, but are also internalised.

The UK family connection

The interview and focus group data clearly shows the value for men of their connections to a family settled in the UK. Employment was usually provided by the wife's family or their social network, overcoming barriers such as lack of fluency in English (many had learned English at school, but were less confident in speaking and listening comprehension – particularly given the challenge of getting to grips with local accents). Wives were also key sources of both support and information about their new social context. As one focus group member said: ‘Here your wife is your best friend’.

Not all participants, however, found their wife's family supportive. One of the recently arrived focus group members stressed the kindness of his wife's parents, who had encouraged him to spend time with his wife and family, take English classes and explore his new surroundings for three months after he arrived, before finding him employment (after which they warned he would have less time for such activities). Others, however, reported being sent to work very soon after arrival. One man emphasised this point by going round the group asking whether the others had been sent out to work the day after they arrived, ending by imitating a UK in-law saying ‘That's why we brought you here’. The high costs of weddings, of setting up home (if a couple lives separately) and not least of the immigration process, where visa fees have increased dramatically in recent years, are an important context here. Nevertheless, from the husbands’ perspectives, wives and in-laws were often a source of expectations which could be in tension with their own gendered aspirations for life post-migration. Crucially, expectations of earning to support the UK family, combined with the types of employment available through family contacts, could inhibit both aspirations for training and employment, and the ability to remit to families in Pakistan.Footnote11

The ‘Mangetar Trap’

Mangetar, which literally means fiancé(e) has come to be used in a derogatory sense by some British Pakistanis to refer to migrant husbands, and is taken to connote a lack of knowledge, limited and accented English, cultural backwardness and domestic subordination (Charsley & Bolognani, Citation2017). Most of the participants in the recently-arrived men's focus group described a situation in which they felt trapped in some way by the circumstances of their life. Whilst elsewhere Charsley and Bolognani (Citation2017) have cautioned against the use of the term to refer to migrant husbands, here we use the phrase ‘Mangetar Trap’, as perceived negative attitudes towards these new arrivals, together with their domestic situations and language skills, form part of this experience of trapped-ness.

The ‘Mangetar Trap’ connotes a combination of factors. With limited English (or at least limited confidence to engage in conversation) as one focus group participant put it, outside the house: ‘we live like deaf and dumb’. If someone in the street smiles at us and says hello, another man complained, what can we do? Others described the disorientation and limitations of not being able to decode public transport information. English language classes are available, but following significant cuts to funding are often not free,Footnote12 and test fees are high. The jobs such men commonly take up (catering, dishwashing, factory, warehouse, shop work) are low paid – we had reports in Northern England of working kitchen shifts of 10 hours or more for £25-£30, well below the minimum wage. The resulting financial constraints can be a barrier to both English language tuition, and to taking up vocational training which might help secure better paid or higher status employment, but which is often expensive. Moreover, particularly when attempting to shoulder dual financial responsibilities of breadwinning & remitting (Charsley, Citation2005), such men tend to work long and/or antisocial hours, taking better paid nightshifts in factories, for example, and even restaurant work often involves a very late finish. Some participants apparently worked multiple jobs. They can be left with little time and energy for pursuing other activities. Hence, Jafar, who worked long and irregular hours for several years after he arrived initially attended English classes but abandoned the attempt after ‘the teacher told me that I could not come to class tired, I needed to recharge my batteries first’.

In these workplaces, men also tend to work alongside other migrants, providing little opportunity to practice English in conversation. Keenly aware of being ridiculed by some British Pakistanis as mangetars (or ‘freshies’) recently arrived focus group participants were often reluctant to practice their accented English with their wife's relatives, and had generally not developed friendships with British Pakistanis. The ‘Mangetar Trap’ thus appears as a vicious cycle in which the nature of employment combined with financial expectations and a certain degree of stigma limits ability to take up the kinds of training, or even improve their English through everyday practice, which might enable them to change their employment for the better. The participants in the focus group for recent arrivals saw limited prospects for ‘escape’ from this situation, not only because of the practical challenges, but also because of the blows to confidence inflicted by their situation. Men in the older focus group who had managed to make the move to what they considered better employment spoke of the value of individuals and opportunities which encouraged them to rebuild self-confidence undermined through low status work, lack of language skills and local knowledge, and sometimes conflictual relationships with in-laws.

Conflict over remittances

Echoing Charsley's earlier research (Citation2005, Citation2013), remittances emerged as a common source of tension with wives and in-laws. Men could see that money was tight, but were often upset that their wives or in-laws wanted to prevent them from remitting.Footnote13 Charsley's research with women in this context (Citation2013) gives insight into their perspectives as, in addition to the costs of transnational marriage outlined above, remittance desires may bolster suspicion that a migrant husband is more interested in the economic opportunities of migration than the marriage. British Pakistani household income is often low, and whilst those brought up in the UK may have family holiday homes in Pakistan built with remittances sent by their parents or grandparents (Erdal, Citation2012), they seldom have direct experience of obligations or desires to remit.

In the QED focus groups, men who arrived over ten years ago had remitted regularly, although they emphasised the financial hardship this had involved. One declared that ‘mangetars are the hardest working people in this society: they sacrifice themselves’. The more recent arrivals, however, all reported that they had so far been unable to fulfil their desires to send money to family in Pakistan.

Transnationalism, masculinity, disconnections

Remittances have been seen as one way that men can achieve status in eyes of those ‘back home’, to compensate for challenges to masculine aspirations in the country of migration. Where the flow of family finances is expected to be multi-directional (Singh, Citation2013), men may experience shame or dishonour if they cannot fulfil these expectations (Walter et al., Citation2004). Expectations from those left behind are often particularly high – what Singh, Citation2013 calls the ‘Money Tree’ syndrome (see also Lindley's description of some Somali migrants’ dread of the ‘Early Morning Phonecall’, Citation2010). Impressions of the wealth to be found in the UK are reinforced by conspicuous consumption by migrants or British Pakistanis on visits ‘back home’ (Bolognani, Citation2014).

Peggy Levitt (Citation2001) has pointed to the existence, alongside financial remittances, of ‘social remittances’: the ideas, norms, behaviours and knowledge that migrants bring or send back to their countries or communities of origin. Sabates-Wheeler, Natali, and Taylor (Citation2009), however, point to the potential distortion of information flows between migrants and their family and social networks ‘back home’. Writing of Ghanaian migrants to the UK affected by discrimination, they suggest: ‘These experiences are both difficult for those in Ghana to understand and humiliating for the migrant to convey, so that they may often go unreported and contribute to a lack of understanding on the part of those at home.’ Elsewhere, Charsley has explored the role that the demands of izzat (honour) may play in silencing masculine distress (Citation2013), and some Pakistani migrant husbands may conceal the shame of their lack of economic success from those in Pakistan (Malik, Citation2010). One of the recent-arrival focus group participants suggested that ‘only one man in ten tells the truth’. All the participants in this focus group had told their families of the hardships they were facing and reported them to be sympathetic. (Many of those interviewed in Pakistan reported their families’ main expectation of them after migration was that they should be happy, so expectations of migrants should not be reduced to financial instrumentality.) The recently-arrived migrants reported, however, that they were not believed by young men they knew in Pakistan, who thought that they were trying to keep benefits to themselves and discourage others from migrating. One said that he had even videocalled his friends from work, to show them his dishwashing job first hand, but they had disbelievingly replied that his real job must be elsewhere. Whilst the transnational social field is therefore a crucial context for understanding contemporary spousal migration from Pakistan to the UK, not least as it is also a marriage field, it is one patterned by differing interests and levels of information (Carling, Citation2008) such that even when ‘social remittances’ are sent, they may not be accepted by their intended recipients.

Strategically flexible masculinities?

Batnitzky et al. (Citation2009) describe Indian migrant men employed in low-status, feminised work in a London hotel as being ‘strategically flexible’, accepting work which doesn't match their classed masculine aspirations, but allows fulfilment of other goals such as the hegemonic role of family provider. Willingness to be flexible in this way depends on the perceived ‘trade-offs’. For the recently arrived husbands discussed here, however, compromising their aspirations in a similar way does not appear to have paid off in terms of status elsewhere. Rather than gaining breadwinner status domestically, the recent arrivals were only marginal contributors to their new families in the UK, as their wives' earnings were significantly higher.Footnote14 This combines with a derided position as ‘mangetars’, and dependency on their wives and in-laws. These recent migrants were also unable to display success transnationally through remittances.

Out of the trap?

Is this subordinate status just a phase? Relationships within households, social networks, and socio-economic positions develop and change over time. The early months or years after migration may be particularly challenging. Weishaar's Polish interviewees in Scotland, for example, reported similar issues of overwork, language difficulties and stress in the initial period after migration to the UK, but many found ways to cope with these challenges, and later to adapt in ways which improved their situations (Weishaar, Citation2008, Citation2010).Footnote15

In a rejoinder to Charsley's first piece on migrant ghar damad (Citation2005), Chopra (Citation2009) suggested that the positions of migrant husbands may change later in life, as they become household heads, reaping the patriarchal dividend. Lifestage may also play a role in easing demands, with the years after migration a particular pinch point in which low earnings combine with establishing a household, the birth of children, and financial needs of relatives in Pakistan. Requirements for remittances are also likely to decrease over time as younger siblings complete their education and themselves get married, and/or with the death of the migrant's own parents.

Ali Nobil Ahmad (Citation2008), on the other hand, posits that for recent migrants from Pakistan, changes to the economic environment may mean that they never escape a subordinate status – lacking access to stable well paid manufacturing jobs or affordable property ownership, rather than become homeowners, landlords and employers, they may be condemned to rent property and seek employment from those who arrived in earlier generations.

Our research with men who have been in the UK for a longer period suggests variation in the extent to which situations change over time. The men in the older focus group had eventually changed their lives substantially, gaining what they viewed as more respectable employment. They attributed this shift to a variety of lucky encounters which included many opportunities no longer available (cheap or free further education, a particular State-funded employment scheme, and an emerging market for translation services which is now over-supplied). All the men in this group also had further education, so may be among the most advantaged of their migration cohort, and also those more likely (eventually) to fulfil their pre-migration expectations (Sabates-Wheeler et al., Citation2009). Participants in both groups reported knowing some men who they described as stuck for decades in situations of low status at work and at home – the teacher reported having to make doctors’ appointments for men still unable to use basic English years after their arrival. But, with the support of wives and in-laws, some may escape the ‘Mangetar Trap’ or avoid it altogether. Hence, the young man who was most optimistic for his future prospects reported a much better relationship with his in-laws than the others described – he was the one who spent time settling in before starting work (to be able to afford this, it should be said that it is likely this family was relatively well-off).

Others manage to save and become self-employed. Jafar for example, who was too tired for English classes, eventually entered construction work, learning English on the job. He now runs his own business, working with people from various ethnic backgrounds. Interviewed for the Marriage Migration and Integration project, he narrated the ways that his life gradually improved in a virtuous circle of work opportunities, social networks and English proficiency:

I was working very hard, but I always got the same money, regardless of the amount of the hours. My English was very poor, but I did not need much English for a packing job. I don't know if my English was too poor, but the new supervisor … started to give me problems. So I started working on building sites. I learnt all building work here - I was only a farmer in Pakistan. Slowly, slowly, I built up work. Some weeks I would work one day, some weeks four days. I learnt how to do central heating, tiles, bathrooms … I learnt my English from my friends. In Pakistan I knew a little, but from school. I have English friends from work. English people talk to me about plastering, and I understand quickly, but if they talk about different things, it is difficult for me. I have had a friend from Ghana for a long time, another Jamaican … After 2 or 3 years I started to be self-employed and I am still self-employed. I do plastering and I am taking a course on plastering and decorating. I am also doing a course to get a certificate to do central heating and then I will be paid more money … It has been easy for me to make friends and now I make new friends at college, it is easier because I speak more English

For most of the participants in the focus group of recently arrived men, taxi driving was considered one of the few probable routes out of the low-pay, long-hours employment in which they felt themselves to be trapped. Taxi driving is a key source of employment – our analysis of the LFS data reveals that just over a quarter (25.8%) of employed Pakistani migrant husbands work as taxi drivers. This prospect is not unanimously favoured, however. It may be resisted as low status or less than respectable by middle-class Pakistan men, is well known for the difficulties and sometimes racial abuse associated with the night time drinking economy, and many drivers complain that the financial rewards are not what they once were. But men like Tahir provide visible examples in local communities of migrant husbands who have transcended the constraints of shop/factory/kitchen work. Taxi driving was not, however, a career option immediately available to the new arrivals in our research, as the capital, documentation and local knowledge required was something they envisioned taking several years to acquire. Hence, in the LFS data, only 6% of those who had been in the UK for less than six years were employed as taxi drivers, but this rose to nearly a third of those 11–15 years since arrival, and 48% of those resident in the UK for 21–25 years (although the sample numbers in this latter group are small). In this context, there was excitement among the recent arrivals focus group to learn that a compatriot and former factory worker had been taken on as a trainee bus driver – an alternative route out of the low status, low wage economy.

Out of the marriage?

For Sabates-Wheeler et al.’s (Citation2009) Ghanaian participants, ‘great expectations’ of the UK were frequently met with a ‘reality check’ of life as a migrant. In response, those with few alternative options adapted to their disappointing situation, whilst more advantaged migrants could successfully return. In Lum’s (Citation2016) work with unemployed irregular Pakistani migrants in Greece, return or onward migration through Europe was something several had considered. For marriage migrants, however, return to their country of origin is complicated by their relationship with their British spouse.Footnote16 When one recently arrived focus group participant described his situation to friends in Pakistan, they apparently replied that if it was that bad, wouldn't he just come home? If they had known what they did now, the focus group members agreed, they would never have come.Footnote17 When we asked the group whether they had considered returning, however, the reply was unanimous and incredulous: ‘You can't leave your wife!’.

In addition to emotional attachments to wives, the fact that the great majority of UK-Pakistan transnational marriages are between members of extended kin groups mean that separation and divorce would be complicated by and have consequences for wider family relationships (Charsley, Citation2013). For some migrant husbands, however, the stresses and tensions of their situation lead over time to serious marital conflict, and not all such marriages last (Charsley, Citation2013; Qureshi, Charsley, & Shaw, Citation2014). On visits back home, when the derided mangetar may have the chance to perform the envied role of visiting migrant, a few men contract second marriages. Occasionally, these marriages occur before the first marriage has ended (although it may end rapidly when the first wife finds out about this second union) or at least before the civil divorce has been finalised. As Charsley and Liversage (Citation2013) suggest, these second marriages can be interpreted as an attempt, facilitated by a context of transnationalism, to construct an alternative less challenging domestic position and re-establish a position of patriarchal authority. Such second unions are often constructed as evincing a lack of commitment to the first marriage (Charsley & Liversage, Citation2013; Home Office, Citation2011), but given some men's experiences of being the migrant incomer in a British Pakistani family, it is perhaps not surprising that second time around they opt for what may seem to them to be a safer and more familiar option. It would be simplistic, however, to view such a second marriage as a solution to domestic status issues for migrant husbands – whilst they may be able to establish a different relationship in their new marriage or household, the breakdown of the initial marriage may carry heavy costs in terms of stress, finance, and relationships with children and wider family (Charsley, Citation2013; Charsley & Liversage, Citation2015).

Conclusion

Migrant men from the global South often appear in the literature as figures grappling with a loss of power and status – at work, but also in their family lives as domestic relations of power and dependency are reconfigured. Bob Pease, writing on migrant men in Australia, suggests that their suffering is product of loss of patriarchal privilege: ‘it appears that any challenge to men's privilege and any changes in patriarchal power relations are experience by many men as a reversal that positions them as oppressed’ (Citation2009, p. 90). For men low down in age, kinship or other social hierarchies in their society of origin, however, migration may represent a moment of anticipation of power. Migration may be imagined as potentiating transition to an adult or more desirable masculine status through the acquisition of wealth, worldly experience, and/or responsibilities (Charsley & Wray, Citation2015). For Pakistani men migrating through marriage, the transitions of migration are coupled with the new status of husband, itself associated with adult manhood. Their arrival in the UK can, in other words, be a point of considerable tension between aspiration and constraint.

Migration can thus simultaneously be a masculine identity project, and challenge or undermine hegemonic expectations of gendered roles and status (Charsley & Wray, Citation2015). Compensatory status may be sought in other arenas in locations of settlement (Gallo, Citation2006; George, Citation2005) or in relation to audiences ‘back home’ (Charsley & Liversage, Citation2013). This compensatory logic has been interpreted by Batnizky et al as a strategic flexibility with class and gender identities. They suggest that a ‘migrant's willingness and/or desire to enact “flexible and strategic masculinities” is tied to the perceived trade-offs of his/her employment in the UK.’ (Citation2009, p. 1275). For the recent migrant husbands described in this paper, however, the combination of factors we have described as the ‘Mangetar Trap’, including their marital commitment to a UK spouse, constrain the element of choice implied in Batnizky's et al.'s formulation. With access to employment initially mediated through the wife's family, lack of skills and knowledge to access alternatives, and opportunities for skills acquisition constrained by low income, time poverty and social divisions, many are at least initially confined to low status employment, whilst failing to benefit from a ‘trade off’ in status gained elsewhere. The inability to remit to family in Pakistan reported by recent migrant focus group participants presents a notable contrast both to earlier studies and to the experience of the earlier migrants who participated in this research, and may be indicative of wider structural changes disadvantaging contemporary Pakistani husbands migrating to the UK. What we have called the ‘Mangetar Trap’ may not be universal, nor inevitably long-lasting. But to dismiss these tensions on these grounds would be to miss a key lesson arising from this case, which is to caution against an over-emphasis on agency in accounts of men's gendered experience of migration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Katharine Charsley is Reader in Sociology at the School for Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol. Her main areas of interest are gender, the family and migration, and particularly in transnational marriage. Her edited collection Transnational Marriage (2012), and ethnographic monograph Transnational Pakistani Connections: Marrying ‘Back Home’ (2013) are published by Routledge. She was Principal Investigator on the ESRC research project ‘Marriage Migration and Integration’.

Evelyn Ersanilli is Assistant Professor in Sociology at the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam. She conducts international comparative studies on the integration of immigrants and their descendants in Europe. Her focus mainly lies on identity, citizenship and migrant family life. She also conducts research on the development of migration policies.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For elite men, transnational mobility may reinforce rather than undermine relations of power.

2 Full project report available to download at: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/ethnicity/projects/mmi/

3 Interviews were carried out primarily in English by a researcher with familiarity with relevant South Asian languages, with additional translation where necessary. Most interviews were recorded and transcribed, but where this was not possible, detailed notes were written up by the interviewer. Thematic analysis of the interview and focus group material was carried out using NVivo.

4 Both because of the additional sources of data available on this group, and reflecting recruitment difficulties for Sikh migrant husbands.

5 Participants aged 18–42, the majority between 24 and 28. Most had secondary school qualifications or higher, and 6 were university graduates. Only 2 had less than secondary education.

6 Primarily in English but with some translation by QED staff.

7 The use of quotations in the article reflects the mixed composition of the data: where note taking (rather than recording and transcription) was employed, for example in the QED project, quotations have only been provided where the researcher was able to record exact phrasing while note taking, and these are generally short.

8 And only since 2011 on language proficiency.

9 Other datasets provide insufficient samples for relevant groups: British Household Panel Survey <50 couples of each group, Understanding Society: approx. 100 Indian Sikh and 300 Pakistani Muslim couples.

10 One earlier migrant stressed that such contacts outside the wife's family turned out to be particularly important in creating a wider range of opportunities and support.

11 Many of the recently arrived men also described themselves as having been spoilt by their own parents, not always expected to work (levels of employment were also low among the Pakistani survey participants, and one of the older focus group men spoke of a life of luxury in Pakistan provided by his elder brother). This situation in which parents cosset their own child, but have more instrumental expectation the role of a child's spouse, strongly parallels that of the contrasting treatment of Indian daughters and daughters-in-law (Kaur & Palriwala, Citation2014).

12 A recent partial reversal in funding cuts has been presented as aimed at Muslim women.

13 cf. Charsley and Liversage (Citation2015) on a divorced migrant Turkish husband in Denmark facilitating secret remittances by his still-married friends.

14 Although LFS data shows that many wives may not work.

15 Also see Safi (Citation2010) for quantitative evidence from a European survey suggesting that life satisfaction of migrants does not significantly increase over time.

16 In Charsley's ethnographic research, she has encountered a small number of couples who have migrated to live in Pakistan either temporarily or longer term, with mixed success, but this option was often unappealing to wives born and raised in Britain.

17 In contrast, all but one of the older focus group said that their migration had been worth it in the long run, although as noted above, they may not be typical of their cohort in class/educational profile.

References

- Ahmad, A. N. (2008). Gender and generation in Pakistani migration. In L. Ryan & W. Webster (Eds.), Gendering migration (pp. 155–170). Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Batnitzky, A., McDowell, L., & Dyer, S. (2009). Flexible and strategic masculinities: The working lives and gendered identities of male migrants in London. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35(8), 1275–1293. doi: 10.1080/13691830903123088

- Bolognani, M. (2014). Visits to the country of origin: How second-generation British Pakistanis shape transnational identity and maintain power asymmetries. Global Networks, 14(1), 103–120. doi: 10.1111/glob.12015

- Carling, J. (2008). The human dynamics of migrant transnationalism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(8), 1452–1477. doi: 10.1080/01419870701719097

- Casey, L. (2016). The Casey review: A review into opportunity and integration. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-casey-review-a-review-into-opportunity-and-integration

- Charsley, K. (2005). Unhappy husbands: Masculinity and migration in transnational Pakistani marriages. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 11(1), 85–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9655.2005.00227.x

- Charsley, K. (2013). Transnational Pakistani connections: Marrying ‘back home’. London: Routledge.

- Charsley, K., & Bolognani, M. (2017). Being a freshie is (not) cool: Stigma, capital and disgust in British Pakistani stereotypes of new subcontinental migrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(1), 43–62. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2016.1145713

- Charsley, K., & Liversage, A. (2013). Transforming polygamy: Migration, transnationalism and multiple marriages among Muslim minorities. Global Networks, 13(1), 60–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2012.00369.x

- Charsley, K., & Liversage, A. (2015). Silenced husbands: Muslim marriage migration and masculinity. Men and Masculinities, 18(4), 489–508. doi: 10.1177/1097184X15575112

- Charsley, K., Bolognani, M., Spencer, S., Jayaweera, H., & Ersanilli E. (2016). Marriage Migration and integration. University of Bristol research report available at: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/ethnicity/projects/mmi/

- Charsley, K., & Wray, H. (2015). The invisible (migrant) man. Men and Masculinities, 18(4), 403–423. doi: 10.1177/1097184X15575109

- Chopra, R. (2009). Ghar Jawai (Househusband): A note on mis-translation. Culture, Society and Masculinities, 1(1), 96–105. doi: 10.3149/csm.0101.96

- Connell, R. W. (1987). Gender and power. Cambridge: Polity.

- Cooke, T. J. (2008). Migration in a family way. Population, Space and Place, 14(4), 255–265. doi: 10.1002/psp.500

- Dale, A. (2008). Migration, marriage and employment amongst Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi residents in the UK. University of Manchester: CCSR Working Paper 2008-02.

- Donaldson, M., Hibbins, R., Howson, R., & Pease, B. (Eds.). (2009). Migrant men. London: Routledge.

- Erdal, M. B. (2012). ‘A place to stay in Pakistan’: Why migrants build houses in their country of origin. Population, Space and Place, 18(5), 629–641. doi: 10.1002/psp.1694

- Gallo, E. (2006). Italy is not a good place for men: Narratives of places, marriage and masculinity among Malyali migrants. Global Networks, 6(4), 357–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2006.00149.x

- George, S. (2005). When women come first: Gender and class in transnational migration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Gonzalez-Allende, I. (2016). The migrant family man: Masculinity, work, and migration in Victor Canicio’s Vida de un emigrante espanol. Iberoamericana, 16(62), 131–147.

- Hearn, J. (2004). From hegemonic masculinity to the hegemony of men. Feminist Theory, 5(1), 49–72. doi: 10.1177/1464700104040813

- Hearn, J., Blagojevic, M., & Harrison, K. (Eds.). (2013). Rethinking transnational men. New York: Routledge.

- Holland, J., Ramazanoglu, C., Sharpe, S., & Thomson, R. (1994). Achieving masculine sexuality: Young men’s strategies for managing vulnerability. In L. Doyal, J. Naidoo, & T. Wilton (Eds.), AIDS: Setting a feminist agenda (pp. 122–150). London: Taylor & Francis.

- Home Office. (2011). Family migration: A consultation. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/269011/family-consultation.pdf.

- Howson, R. (2009). Theorising hegemonic masculinity. In M. Donaldson, R. Hibbins, R. Howson, & B. Pease (Eds.), Migrant men (pp. 23–40). London: Routledge.

- Howson, R. (2013). Why masculinity is still an important category: (Trans)Migrant men and the migration experience. In J. Hearn, M. Blagojevic, & K. Harrison (Eds.), Rethinking transnational men (pp. 134–147). New York: Routledge.

- Kaur, R., & Palriwala, R. (2014). Marrying in South Asia. New Delhi: Orient Longman.

- Levitt, P. (2001). The transnational villagers. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lievens, J. (1999). Family-forming migration from Turkey and Morocco to Belgium: The demand for marriage partners from the countries of origin. International Migration Review, 33(3), 717–744. doi: 10.1177/019791839903300307

- Lin, X. (2014). ‘Filial son’, the family and identity formation among male migrant workers in urban China. Gender, Place and Culture, 21(6), 717–732. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2013.802672

- Lindley, A. (2010). The early morning phonecall: Somali refugee’s remittances. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Lum, K. D. (2016). Casted masculinities in the Punjabi Diaspora in Spain. South Asian Diaspora, 8(1), 31–48. doi: 10.1080/19438192.2015.1092301

- Lutz, H. (2010). Gender in the migratory process. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(10), 1647–1663. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2010.489373

- Malik, A. A. (2010). Strategies of British-Pakistani Muslim Women. University of Cambridge: Unpublished PhD Thesis.

- Maroufof, M., & Kouki, H. (2017). Migrating from Pakistan to Greece: Re-visiting agency in times of crisis. European Journal of Migration and Law, 19, 77–100. doi: 10.1163/15718166-12342116

- McGregor, J. (2007). ‘Joining the BBC (British Bottom Cleaners)’: Zimbabwean migrants and the UK care industry. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(5), 801–824. doi: 10.1080/13691830701359249

- Okin, S. M. (1999). Is multiculturalism bad for women? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Osella, F., & Osella, C. (2000). Migration, money and masculinity in Kerala. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 6, 117–133. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.t01-1-00007

- Pasura, D. (2008). Gendering the diaspora: Zimbabwean migrants in Britain. African Diaspora, 1, 86–109. doi: 10.1163/187254608X346060

- Pease, B. (2009). Immigrant men and domestic life: Renegotiating the patriarchal bargain? In M. Donaldson, R. Hibbins, R. Howson, & B. Pease (Eds.), Migrant men (pp. 79–95). London: Routledge.

- Qureshi, K., Charsley, K., & Shaw, A. (2014). Marital instability among British Pakistanis: Transnationality, conjugalities and Islam. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 37(2), 261–279. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2012.720691

- Roggeband, C., & Verloo, M. (2007). Dutch women are liberated, migrant women are a problem: The evolution of policy frames on gender and migration in the Netherlands, 1995–2005. Social Policy & Administration, 41(3), 271–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00552.x

- Sabates-Wheeler, R., Natali, C., & Taylor, L. (2009). Great expectations and reality checks: The role of information in mediating migrants’ experiences of return. European Journal of Development Research, 21(5), 752–771. doi: 10.1057/ejdr.2009.39

- Safi, M. (2010). Immigrants’ life satisfaction in Europe: Between assimilation and discrimination. European Sociological Review, 26(2), 159–176. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcp013

- Singh, S. (2013). Globalisation and money. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Walter, N., Bourgois, P., & Margarita Loinaz, H. (2004). Masculinity and undocumented labor migration: Injured Latino day laborers in San Francisco. Social Science and Medicine, 59(6), 1159–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.013

- Weishaar, H. B. (2008). Consequences of international migration: A qualitative study on stress among Polish migrant workers in Scotland. Public Health, 122(11), 1250–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.03.016

- Weishaar, H. B. (2010). “You have to be flexible”—Coping among polish migrant workers in Scotland. Health & Place, 16(5), 820–827. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.007