ABSTRACT

Joining the research that emphasises the importance of the social and cultural context for reading and masculinities, this article focuses on the significance of book collection for a rural working-class man’s relationship to reading. The data consists of a series of life story interviews, conducted as go-along interviews, with a Swedish rural working-class man in his 60s who collects books. Using theories of class, masculinity and place, and drawing on (Sara Ahmed’s [2010]. The promise of happiness. Duke University Press.) theory of emotions and affect, this study illuminates the intersection of reading practices, identity and masculinity while showing how a working-class man’s reading practices align with and deviate from normative conceptions of being a man within the studied context. Highlighting the practices of interacting with books on a physical level – collecting, holding, sorting, viewing covers, and so on – the article also shows how these tactile practices contribute to a rural working-class man’s development of a reader identity.

Introduction

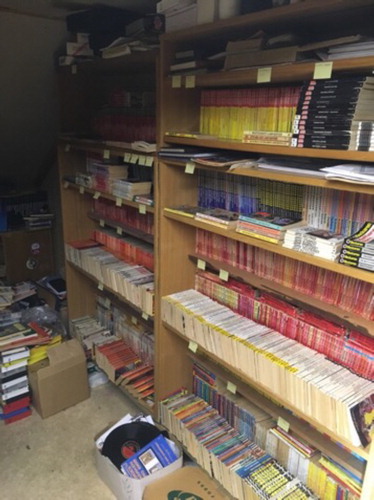

A few years ago, I conducted some life story interviews with Noel, a young working-class man living in the Swedish countryside, regarding his relationship to reading. One of these interviews took place at Noel’s father’s home. Robert, Noel’s father, was present throughout the interview, which developed into a conversation in which Robert, among other things, showed me a large collection of books he had on the farm. When Robert showed me his book collection, I was struck by the large number of books. They were scattered all over his residence and in the large storehouse on his yard. They were to be found in cartons and plastic bags, and they were stacked in piles on the floor. Most of them, however, were placed in homemade bookshelves. In the midst of this plethora of books, one could also discern a certain order. There was a system. After Robert had shown me around the huge book collection, it was clear that there were over 10,000 books there. Moreover, the owner of these books was Robert, a man in his 60s who said he never reads.

Given the extensive amount of research that describes males’ relation to reading as problematic (Brozo, Citation2019; Hammet & Sanford, Citation2008) my meeting with Robert generated several questions. Why, for example, does a rural working-class man who describes himself as a non-reader collect so many books? There and then I decided to return to Robert to let him tell his life story with the overall aim of trying to understand his relationship to reading, and in what ways his book collecting intersected with this relationship. Through a series of life story interviews a more nuanced picture of Robert’s relation to reading and books emerged. Leaning on Ahmed’s (Citation2010) notion of ‘happy objects’ (objects and ideas that are perceived as containing a promise of future happiness, and that circulate as social goods), and paying close attention to the intersection of gender, class, and place when constructing Robert’s life history, I realised that such an approach would make it possible to deconstruct homogeneous representations of rural working-class men and their relation to reading. Against this backdrop, this thematic, biographical case study aims to explore book collecting and its importance to a rural working-class man’s relationship to reading. As such, this article contributes to our knowledge of ways to construct and reconstruct masculinity in the working classes in relation to the cultural practices of reading and collecting books.

Previous research

Research on boys’ and men’s relationship to literacy is extensive, and in a majority of the studies, the relationship continues to be articulated as problematic. One strand of scholars align themselves with an essentialist view, that is, the belief that there are largely biological reasons that determine and explain male literacy underachievement (e.g. Newkirk, Citation2002). Another strand of scholars have opened up a discussion about masculinity as an important construct in the field of literacy research, especially regarding aspects of literacy linked to reading practices, suggesting that some males reject reading as it is associated with femininity (Bausch, Citation2014; Frank et al., Citation2003; Millard, Citation1997).

While this body of research has been useful to many scholars, others have questioned approaches that may inadvertently reify gender-based reading differences rather than open up possibilities for multiple orientations in relation to reading (e.g. Asplund & Pérez Prieto, Citation2018; Hammett & Sanford, Citation2008; Kirkland, Citation2011). Scholars such as Dutro (Citation2003, Citation2008) and Scholes (Citation2018) argue that discourses focusing on ‘failing boys’ often depend upon the assumption that boys are one homogeneous group, thus missing how social categories such as class, ethnicity and place interplay with the construction of male reader identities. This growing body of studies recognises that there are multiple masculinities constructed by different groups of males, and emphasises the importance of considering how other critical contributing factors, besides gender, interact with and influence males’ engagement in reading, and experiences of education.

Working-class males are constantly involved in negotiations between their senses of embodiment and desire, along with the constructions of class, gender and normative ways of being within their specific locality. Here, scholars such as Ingram (Citation2018) and Roberts (Citation2018) present strong arguments for paying close attention to local context when analysing working-class males’ identity constructing processes, thus highlighting a current focus in sociological and educational research concerned with exploring the relationship between masculinity, class and place. In this paper the local context is a rural community in Sweden, and as such, this study also addresses the growing number of studies that explore the interrelationship between masculinities and rural space. A considerable literature has shown how stereotypical notions of rurality and masculinity tend to conceive of males in non-metropolitan sites as passive, as unmodern, and as people who continue to reproduce traditional (hegemonic) masculine identities and gender relations (e.g. Areschoug, Citation2019; Campbell, Bell, & Finney, Citation2006). However, recent studies also identify additional, more flexible rural masculinities, thus acknowledging rural men who expand the convention for how to be a rural man (e.g. Bull, Citation2009; Hoven & Horschelmann, Citation2005). In a Scandinavian context, Bye (Citation2009) identifies new and alternative masculinities among young rural Norwegian men. However, in order for those men to keep their masculine identity, they have to accentuate certain aspects of the hegemonic rural masculine discourse, such as handyman skills and nature mastery. Bye’s study shows that it is easier for men in rural societies to perform new and alternative masculinities, than it is to abandon more traditional masculinities and gender relations.

This study adds to the critical studies of men and masculinities literature that seek to broaden and nuance our understanding of men’s identity construction practices that intersect with social and cultural change, and highlights different spatial (Hopkins & Noble, Citation2009) and temporal dimensions of social life (Stahl, Citation2020) by examining book collecting and its importance to a rural working-class man’s relationship to reading.

In the literature, book collecting is described as a practice that in a historical perspective has largely been practiced by the middle and upper classes. Book collecting has also been described as a strongly pronounced masculine practice (Egginton, Citation2014; Taylor, Citation2000). Despite this awareness in previous research, there is an evident lack of studies that problematise the practice of collecting books in relation to male reader identities, and this article also aims to fill this specific gap.

Theoretical and methodological perspectives

The question of what significance books have in relation to Robert and his relationship to reading will be examined from a narrative perspective (Andrews, Squire, & Tamboukou, Citation2013; Kohler Reissman, Citation2008), and on a view of literacy as a social practice. While literacy as a concept is used in a broad sense, as described within the field of New Literacy Studies, based on questions of how, why and with whom people interact, using a wide repertoire of sign systems and different communication technologies (Barton & Hamilton, Citation1998; Gee, Citation2010), this article focuses on reading literacy. Reading is from this standpoint viewed as a dimension of literacy. It is seen as an intellectual, emotional and socio-cultural process that includes meaning-making and identity construction activities, and as embedded in educational, social and cultural practices (Barton & Hamilton, Citation1998; Scholes, Citation2018).

Robert’s story about his relationship to books and reading constitutes a unique case, but his story also forms part of a dominant view of reading as a solitary, silent perusal of printed text, where books are seen as something good and important for fostering democratic citizens, and reading is thought of as a powerful and essential prerequisite for learning and self-development (Bloom, Citation2000; Persson, Citation2012). These are values that have surrounded, and still surround, Robert, and are also the values and attitudes that he, more or less explicitly, construct and reconstruct in his storytelling.

The approach can be described as a life story approach that puts the narrator, Robert, and his story at the centre as the basis for understanding the experiences of books and reading that Robert chooses to talk about in the interview conversations. Robert’s storytelling is thus regarded as a socially situated act through which he constructs himself, expresses attitudes about books and reading, and positions himself in relation to others. His narrative about books and reading is thus seen as both a performative act and a meaningful process in which Robert tries to understand himself and the surrounding context (Mishler, Citation1999).

Place, gender and class

Robert’s book collecting takes shape in a specific geographic site, with its specific social, cultural, economic and physical history. According to Massey (Citation2005), place can be thought of as an ever-shifting constellation of a plurality of trajectories and social processes, including stories. It is constructed and co-constructed by people based on their actions and social relations, and always under construction. Through this interaction, people also develop a sense of space; an awareness of living in a distinct place with its specific cultural and social practices and the emotional bonds that people establish with that place over time (Massey, Citation2005). This view of place and space as negotiated, social constructions and the reciprocal relationship between place, space and identity are central aspects in the life history approach (Goodson, Citation2013), and in my work analysing the interviews. Drawing on Massey’s theorisation of place and space, I am interested in the dynamic, situated and historical relationship between Robert and the specific place in which his storytelling about his book collecting takes shape, and how gendered subjectivities interact with his reader identity in that specific place.

Equally central to the approach is my understanding that there are multiple constructions of masculinity (Hearn, Citation2015) which are constantly constructed and reconstructed in relation to other positions, and that these intersect with reading engagement (Scholes, Citation2018). Emerging critical studies of men and masculinities have reported a shift in positions whereby a hegemonic or orthodox archetype of masculinity, characterised by heteronormativity, physical strength, misogynistic attitudes and emotional restraint, is challenged by softer and more inclusive masculinities (Anderson, Citation2009; Citation2014; Ward et al., Citation2017). This shift may also have implications for the gendered subjectivities of some working-class males’ incorporation of traditionally feminine coded pursuits such as reading in their identity construction processes (Scholes, Citation2018).

In order to offer a more complete picture of the intersection of reading and identity, I will turn to Bourdieusian theory (Citation1977, Citation1984, Citation1992, Citation2002). According to Bourdieu, class affiliation cannot be limited to economic assets; social class is also about different forms of capital and the tastes and chosen lifestyles of individuals and groups. Together, these are important aspects of an individual’s position within a social hierarchy or social space. A central concept in Bourdieu’s toolbox is habitus, which can be understood as the habits, lifestyles and patterns of action that individuals express in interaction with the surrounding society and that have been shaped by internalised structures. For Bourdieu, the habitus is ‘a system of dispositions, that is of permanent manners of being, seeing, acting and thinking, or a system of long-lasting (rather than permanent) schemes or schemata or structures of perception, conception and action’ (Bourdieu, Citation2002, p. 27, emphasis in original). Habitus is one of Bourdieu’s most contested concepts, as it has often been perceived to restrict people’s scope for action (cf. Archer, Citation2007; Jenkins, Citation2002). However, I align with those recent Bourdieusian scholars who have acknowledged a more dialectical stance in Bourdieu’s theory of social practice highlighting the mutual relationship between agency and social structure. This approach opens up for interpretations where individuals are given room and agency to make their own choices and act accordingly, while they will also simultaneously be influenced by social structures (Ingram, Citation2018; Roberts, Citation2018; Stahl, Citation2015). Thus, in this study, Robert’s choices and attitudes will not be understood as static and pre-given, but as performative, contextual and embodied actions that are expressed in his social interaction with others. Although habitus is a subjective concept, Bourdieu also stresses that each individual system of dispositions may be seen as a structural variant of a certain group or class habitus that a person belongs to (Bourdieu, Citation1977). The habitus that is expressed in Robert’s story about his experiences of, and relation to reading, texts and books, therefore becomes an important element in my analysis of the relationship between reading and identity, as my starting point is that class, as well as other social categories such as gender and place, is important for how people handle their everyday lives and how they interact with other people (Asplund & Pérez Prieto, Citation2013; Ingram, Citation2018; Roberts, Citation2018; Stahl, Citation2015).

Happy objects

Apart from place and habitus, another important aspect to take into consideration in the analysis will be the nostalgic and emotional character that is clearly evident in Robert’s story, and here I will turn to Sara Ahmed’s theory of emotions and affect (Citation2010). According to Ahmed, emotions are formed culturally, and a central idea in her theory is that the origin of an emotion does not originate from a subject or an object, but in the connection between them. Emotions are relational in character; they involve relationships of proximity and distance to objects, and as soon as this relationship between an emotion and an object is established, it is given its individual and social significance. Ahmed emphasises the affective state of happiness, and she believes that the reason why we experience positive feelings in encounters with certain objects is that we, through repeated encounters with these objects (through our own experiences or through a social history where other people made similar judgements about the object) have experienced feelings of satisfaction and happiness. This results in situations in which we attribute positive properties to these objects, because happiness, according to Ahmed (Citation2010, p. 69), has ‘stuck’ to them. We then orient ourselves towards these objects as ‘happy objects’ to seek happiness and satisfaction. Social ‘things’ and phenomena such as values, practices, lifestyles and aspirations can also function as happy objects. For Ahmed, objects are not empty of content, but invested with stories and historical patterns that can be activated when a relationship is created between the subject’s emotions and the emotions that are invested in a material or mental object.

The expectation of pleasure from an object is not merely a question of an individual orientation; the cohesion of a social group is determined by its ability to align itself with the same happy object. When the group faces the same way, the object incites further pleasure and increases its affective significance. The social dimension also means that those who do not experience pleasure from objects that are already considered as a social good by others, become alienated or differentiated. Leaning on Bourdieu’s Distinction (Citation1984), Ahmed (Citation2010) suggests that this creates situations in which social groups express aversion to different tastes and lifestyles, thus making the distinction of happy objects an issue of class affiliation. Accordingly, suggesting that certain objects take shape as happy objects through the habitual actions of bodies means that happy objects can be inherited, and therefore habitually (non-reflexively) reproduced. Hence, the orientation of social actors and groups towards certain objects carries the marks of history. Thus, in the context of the present study, the way male working-class readers act and orient themselves in space and to objects is closely related to the historical formation of masculine identities and the way in which those identities intersect with class and place (cf. Åberg & Hedlin, Citation2015).

Data collection and analysis

Four interviews have been conducted with Robert (including the interview in which his son Noel participated). On the second occasion, a life story interview was conducted in which Robert told me his life story, and about his relationship to and experiences of reading. To achieve structure in this interview, an interview guide was prepared ahead of time as a support. The last two interviews, of which the latter was video-recorded, focused on Robert’s book collecting. Before these interviews, the former interview was transcribed and, based on the listening and transcriptions of each interview, Robert was asked to tell more about some areas/themes in his narrative that I found undeveloped, and sometimes he elaborated further on what he had narrated in the previous interviews without prompting. All interviews have been audio-recorded and they have been conducted as go-along interviews, an approach that can be used to obtain contextualised perspectives by conducting mobile interviews with the participant as a navigational guide of the immediate space within which he or she lives (Garcia, Eisenberg, Frerich, Lechner, & Lust, Citation2012). The method also encourages and involves relations and ‘connections between objects, bodies and places’ (Flint, Citation2019, p. 123).

In total, Robert was interviewed for seven hours and all interviews have been transcribed verbatim. The analytic approach is inspired by Kohler Riessman’s (Citation2008) dialogic/performative approach. In dialogic/performative analysis, the communicative and cultural resources used, as well as the audiences one relates to and the positionings taken in storytelling, are brought into interpretation. In this approach, the local context and ethnographic encounter are also essential parts of the analysis as well as attention to broader contexts, including dominant discourses and values circulating in a particular culture.

Life story interviews involve social interaction between the interviewer and the interviewee; thus, the interviewer becomes an active presence in the interview situation that can influence the narrator in his or her storytelling. One must also be aware of the fact that the researcher brings his or her own specific perspectives from which certain stories are given more space than others. It is therefore important that the construction of the life history is driven by data, and in this work I have adopted a ‘naïve‘ approach (Asplund & Prieto, Citation2019) that emphasises the importance of placing the narrator and his story at the centre in the interview situation and in the analysis. When it comes to my own positionality, Robert knew me (through his son) as a male literacy teacher and researcher. These positions were also something that Robert oriented towards on several occasions during the interviews (which will be shown below). I am also familiar with the local community through research I have conducted in the community over several years, for which I have been collecting ethnographic data such as interviews with local residents and documentary resources. These previously collected data have been crucial when providing Robert’s individual story within a theory of context (Goodson, Citation2013).

Robert

Robert is a man in his 60s who lives with his partner in a small village in the Swedish countryside. Robert grew up in the village where he has lived all his life, and he has two adult sons from a previous marriage. Today he works as a self-educated excavator. (In Sweden, the formal schooling for becoming an excavator operator is a three-year vocational programme at the upper secondary school level.)

The village is located in a geographically extensive rural municipality (11,000 inhabitants) dominated by more or less populated forest areas, and it has struggled with a sharp decline in population since the 1960s. Most of the working-age population is employed in service-oriented occupations, with 10% engaged in agriculture, forestry, hunting and fishing, as compared with the national average of 2%. The level of education, when compared with that of the country as a whole, is lower; 14% (ages 25–64) have completed tertiary education, as compared with 28% in the entire country.

In several respects, Robert represents the typical non-reading man highlighted in international research; working as an excavator, and living in the countryside. The desire to fit into local versions of normative discourses of masculinity that position reading as outside sanctioned ways of being a male has often, in Sweden as well as in many other countries in the Western world, confined reading experiences and achievement for some males, and especially rural, working-class men (Asplund & Pérez Prieto, Citation2018; Hammett & Sanford, Citation2008). On the other hand, Robert represents a unique case because of his genuine interest in books and his extensive book collection. This unique case, together with what is ‘typical’, makes Robert’s story particularly important to pay attention to, as it can highlight the existence of alternative stories about working-class men and reading than the ones dominating the field, and increase our understanding of this relationship.

Findings

The book collection(s)

The vast majority of Robert’s 10,000 books are stored in a large storehouse in the yard, and placed in homemade wooden bookshelves. Robert has worked out a specific way of categorising and systematising his book collection, and for him, it is a matter of first dividing the books into two larger separate departments: ‘The library’ and his ‘own collection’. In each department there are further divisions where Robert, through his specific way of sorting and organising the books, attributes them to different cultural categories.

‘The library’

‘The library’ is in the eastern wing of the storehouse. Once upon a time, Robert had plans to build a car workshop here, but now there are only books. ‘The library’ is divided into several different departments. One department is the ‘Norwegian department’ which consists of about 3,000-4,000 books written in Norwegian by Norwegian authors, or Norwegian translations of works by authors such as Gabriel García Márquez, John Steinbeck and Frederick Forsyth .

In the second department of ‘the library’, Robert keeps books written in Swedish or translated into Swedish. Robert tells me that there are about 6,000-7,000 books, and in the first part of the department, fiction is interspersed with nonfiction. Further into the room, the books are placed more systematically by publisher, author, and genre, but also by format (hardcover, carton, pocket, etc) .

Robert says that he often puts books from ‘the library’ for sale on internet-based auction sites and sometimes he gets paid quite a lot for books that prove to be desirable for other book collectors. Several times, book collectors from other parts of Sweden have visited Robert to buy and/or exchange books. The day before the fourth interview, a man from Gothenburg visited Robert, just to buy some ‘western books’ (books in the category ‘westerns’). ‘His wife’, says Robert, ‘was so happy to meet me, because now she knows there are other lunatics apart from her husband, she said’, says Roberts and laughs.

The local residents also know that Robert collects books and quite often people in the neighbourhood, young men and women as well as older people, come to Robert to borrow, buy, or exchange books. There is also a clear gender pattern in what the locals want to read. The women, says Robert, want ‘love literature’, explaining that this means Harlequin romance novels, while the men want to read detective stories and westerns, thus confirming the stereotypes of male and female readers (Dutro, Citation2003).

The private collection

The private collection is separated from the ‘the library’ in that it is located in another department in the storehouse, and in that here Robert only stores books that belong to the genres westerns, detective novels, spy novels and war books. These books were published in major editions in Sweden as part of the Americanisation of popular culture after the Second World War. Within each category there were several different series published.

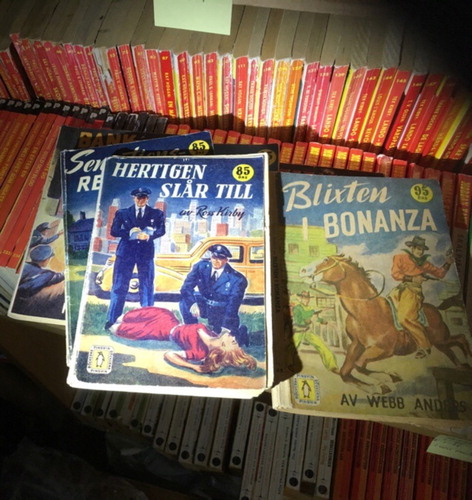

At one end of the room are westerns, or ‘cowboy books’ as Robert also calls them. Here are series such as ‘Bill and Ben’ and ‘Longhorn’ represented. In the middle of the room, the bookshelves are dominated by various detective novels, spy novels and war books. In a bookshelf opposite the war books are hundreds of books of the same colour. The spines of the books are red with yellow text. These are the ‘Manhattan books’, says Robert, and he particularly likes these and .

In addition to sorting the books according to genres, condition, and so on, numbers are also a significant feature when it comes to the categorisation of the collection. The books in Robert’s private collection were published in chronological order (in volumes), which is marked with a number on the respective book spine. For example, the Manhattan books include 475 titles. In the bookshelves therefore, these books have been placed in numerical order. This way it is also easier for Robert to keep track of which books he has and which he does not have in the collection.

As soon as there are numbers, then it is just to start collecting you know, otherwise you have no control then there is no control whatsoever you know. But as soon as there is a number, one, two, and three you know, then it is just to start collecting.

Book collecting as a social practice

During the interviews with Robert, it becomes clear that the sorting, categorisation and classification of the books form an essential and significant part of the book collecting activity itself. Robert has also involved his son Noel in the work from an early age, and together they have travelled in Sweden and Norway and bought books. For Robert and Noel, the handling of the books thus includes activities in which they have sorted books, and then Noel, sometimes together with Robert’s nephew Martin, ‘typed them down in a computer’. Names of the authors, titles, publishers, places and years of publication, and numbers of pages have been recorded. For Noel and his cousin Martin, however, the handling of Robert’s books has also created an interest in books and reading. During the process of sorting Robert’s books, the cousins began to read books themselves, and sometimes they retold stories to each other from books they had read from the collection and had enjoyed reading. Much of the work on the books has also taken place in the room in which Robert has his private book collection. Here they used to sit, all three of them, Robert, Noel and Martin, sorting books, and during the interview conversation when both Robert and Noel participated they started talking warmly about a New Year’s Eve years ago when they stayed up all night and lost themselves in handling and talking about the books. It is these social elements of the book collecting activity that Robert often returns to when telling me his life story.

Aesthetically appealing covers

As a child, Robert spent a lot of time with one of his uncles who lived nearby. Robert describes his uncle as a ‘real cowboy’ who had a great many western books. He also remembers that he thought the covers of the western books published by Penguin (Pingvinförlaget in Swedish) were particularly cool. ‘These Penguin books, they have such cool covers, you know’, he says, and after seeing his uncle’s book collection, Robert started collecting westerns. In addition, many of these books were numbered, which triggered Robert even more in his book collecting:

My uncle had some books there, cowboy books called Penguins. And then there were numbers on them. That was fascinating. Then I would try to get as many different numbers as possible and then I started to collect them. There was a number on them then. As soon as there are numbers you can collect. […] You would try to get as many numbers as possible then. […] Yeah, I started collecting then.

Robert and his relationship to reading

During the first interview, and during the start of the second interview, Robert says that he did not read at all when he was younger, and that he had difficulties reading in school. He also says that he thought it was difficult to read longer texts and that he often forgot what he had just read. Robert perceived reading in school as meaningless because he never remembered what he read and why he was supposed to read, and he never got the opportunity to read texts that interested him. In one respect, therefore, Robert reveals the type of weak reader identity that so many other male readers with a working-class background construct in other studies on masculinity and reading (cf. Asplund & Pérez Prieto, Citation2018).

However, the further into the life story interviews we come, and the more Robert guides me among all of his books, the more nuanced his story turns out to be, and the actual reading act as such, and the books and their specific content, become more prominent. The books also appear through Robert’s narrative not only as artifacts to be sorted and categorised, but also as something that is given aesthetic, economic, community building and nostalgic values. For Robert, the books also carry with them elements of a rural romance and a sense of the American fifties which Robert in many ways associates with the countryside and the community he grew up in and of which he is still a part. ‘Here in Aspdal, it is still the 1950s’, says Robert, and he thinks that is a good thing. The American popular culture that Robert encounters through the books he collects has also inspired him to read these books to a greater extent in recent years, and he also states that he has developed as a reader:

I could hardly read before, but then I started reading. So it’s actually interesting to read. […] I read one book a day. I think that is outstanding. I especially read the pocket books. Those with the big binders. I’m pleased with this then. It’s interesting.

Robert especially appreciates the western books and the detective novels because they are ‘easy-to-read literature’ that is ‘easy to hold’ in his hands, and because he can read them ‘fast’. Whereas Robert says that he still has some resistance to ‘thick’ books, it has happened in recent years that he has read several series with over ten books in each series. Above all, he has enjoyed reading books that depict the settler life in the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries, and he also says that he has learned a great deal from reading. Recently, he has also bought a great many novels about the Swedish settlers in the Swedish wilderness in the nineteenth century, and he is looking forward to reading these. Through these book choices, Robert encounters narrated experiences and wilderness settings that are directly related to his own interests such as hunting and forestry, and to the place in which he was born and raised, and in which he still lives, thus showing how typical rural place-based experiences (Bye, Citation2009; Woods, Citation2010) become internalised in his masculine reader identity. As a proud ‘man of nature’ with family roots in the village for centuries, and with ancestors that left Sweden for America during the nineteenth century, these are experiences and ancestry voices (Goodson, Citation2014) that Robert activates in his reading and selection of texts, and internalises in his rural masculine working-class identity.

Re-appropriating a bourgeois written culture

Robert’s book collecting, specifically the collecting of western books, and his reading preferences, can be seen as acts and choices through which he demonstrates a masculine rural working-class habitus (Bourdieu, Citation1992) and preserves and reproduces the specific social and cultural context in which he lives (Massey, Citation2005). However, there are also several acts that together generate an opposite movement, and which makes it possible to consider Robert’s book collecting as an activity through which he operationalises other sets of dispositions. Not only can the book collection be seen as a project and as an act of preserving a (literary) cultural heritage, but it is also an activity that makes it possible for Robert to construct himself as rural working-class man who reads. The book collecting also involves physical activities such as carrying, holding and touching the books, and building shelves. It also involves physical activities in the social moment when Robert together with his son and nephew tell each other stories about books they have read while sorting the books. In this way, Robert re-appropriates a bourgeois written culture into a social and cultural practice in ways that are socially acceptable within the masculine rural working-class community (Asplund & Goodson, Citation2020). This re-appropriation can thus be seen as a strategy that makes it possible for Robert to align smoothly with another field, at the same time as he can remain loyal to his working-class habitus.

Books as happy objects

The analysis of Robert’s narratives shows an emerging discrepancy between his constructed reading identity on the one hand and his observed reading behaviours and attitudes on the other. During the interviews, Robert relates to the dominant discourse of what reading is and is not, and he also distances himself from this discourse – while also realising that there is a price to pay for standing outside it. On several occasions, Robert relates to me as a literacy teacher and a literacy researcher, saying that he has ‘never read school books’, and in the middle of the second interview, he turns to a bookshelf in ‘the library’ in which there are several books with ‘French bands’. There are people, says Robert, who have such ‘fancy’ books in their bookshelves just because they want to appear as ‘cultivated’ and ‘literate’; stances and behaviours Robert is critical of. In this way, Robert tentatively distinguishes his identity from what it is opposed to (in this case snobbery), thus defining his working-class habitus through difference (Bourdieu, Citation1984). In the same vein, he also draws attention to the western books he enjoys reading, saying: ‘You don’t get so frigging intelligent when you read Bill and Ben and Walt Slade, you know’, referring to the western books he enjoys reading himself. Robert’s downplaying of himself as a reader, and of the books included in his own private collection, can be seen as an expression of the sense of alienation and shame that Ahmed (Citation2010) claims follows those people who do not express happiness in response to proximity to objects that are considered good by others. The marginalisation and oppression of others in order to ‘restore’ the natural social good that Ahmed highlights and questions is thus made visible in Robert’s narrative. Altogether, this also displays how combining a rural working-class masculinity with literate bourgeois middle-class values creates a divided habitus, something that could affect Robert emotionally in a way that could make it difficult for him to operate successfully in both fields (Ingram, Citation2011, Citation2018; Reay, Citation2002). Although Robert at first may emerge as an omnivore in terms of his book collection, what makes him happy is not embracing the ‘right’ books and aligning with the dominant discourse of what reading is. Rather, his habitus opposes the ‘snobbery literary arbiters’, and instead contributes to him focusing more on the type of popular literature which makes him feel nostalgic, emotional and happy, and that he keeps in his private collection. An example of this focus is the aesthetic experience that Robert relives when he retells the memories of when he first saw the ‘cool’ covers of the western books at his uncle’s house. Another example is the social activities that Robert has enjoyed over the years together with his son Noel. Through the different dimensions of the book collecting, of which Robert and Noel have fond memories, a common history around the books and the book collecting has been established.

There are also connections between Robert and the books through the countryside and the community that once was and the people who once lived there. Robert talks with empathy about how the countryside was once full of life and people; there was a school and a gas station next to his house, and the western and Manhattan books Robert now collects were once available in the local store, which no longer exists. Together with his male classmates he read smaller western books that he also collects today, and which he exchanged with his classmates during school breaks as they had read them. But here was also Robert’s uncle who collected western books, and whose collection Robert later inherited. These are events, acts, and people that Robert fondly remembers, and the nostalgic flashbacks from the standpoint of the present testify to a bygone and happy era, when the countryside was alive, and the social ties to friends, relatives and neighbours were highly vital. These nostalgic flashbacks are also embodied through the books Robert now surrounds himself with. With Ahmed (Citation2010) it therefore becomes possible to interpret Robert’s book collecting activity as a movement towards establishing the books as something good, and as something that makes him happy (they are simply filled with positive stories, memories and experiences of a happy era in a double sense). Moreover, here are also texts that give Robert specific meaning and content in relation to his own identity; the western and detective books with their mediation of classic rural masculine working-class ideals (Woods, Citation2010), and the American 50s with its ideals and cultural expressions. This also shows how the construction of a male reader identity at the intersection of the Swedish countryside, masculinity and working-class, is mediated by globalised patterns from popular culture, for instance representations of the American cowboy figure, associated with a classical rural masculine stereotype (Campbell et al., Citation2006; Gibson, Citation2016). Thus, when Robert approaches the western books associated with these rural masculine ideals and lets them gather around him, he not only constructs a reader identity and internalises a rural masculine working-class habitus, but also creates his own sphere of ‘good things’ (Ahmed, Citation2010, p. 39), building up an expectation of happiness by orienting towards the books as happy objects.

Conclusion

Duckworth, Husband, and Smith (Citation2018, p. 502) stress that educational systems across nations have a strong utilitarian function which risks marginalising and neglecting ‘humanistic, transformative and holistic visions of lifelong learning for all.’ Within this context of formal schooling, there has been a strong focus on the performative function of education, whereas broader values of individuals have been neglected. Robert’s story highlights the dominant discourse in formal schooling and society of what reading is and is not, what texts are valued higher than others, and what texts are marginalised and why (Janks, Citation2010). Through his narrative and the downplaying of himself as a reader, Robert also contributes to the maintenance of this discourse. This maintenance of the dominant view on reading and books is also made physically visible through the systematisation and storage of the book collection where the books in ‘the library’ are made publicly visible in the storehouse, whereas Robert’s ‘own’ book collection is placed in a more hidden and inaccessible room. However, the analysis also shows the complexity of Robert’s relationship to reading and texts, where the book collecting enables the construction of a reader identity, and where Robert’s book collecting is not only associated with nostalgia and happiness (Ahmed, Citation2010), but also constructed as an activity through which he builds a sense of control and competence, which also gives him a mandate to see through and question the people who seek out ‘fancy’ books, just to mark cultural status.

The analysis shows that Robert engages in texts that are largely considered as hyper-masculine books (Dutro, Citation2008), which idealise certain aspects of the hegemonic rural masculine discourse, and which embody Robert’s visions of the cowboy figure (Gibson, Citation2016) and the American 50s. While not wanting to essentialise masculine reading preferences and risk limiting the construction of multiple male identities (Hearn, Citation2015), Robert’s book collecting highlights the relationship between choice and schooling. What the analysis also shows is that it is precisely through these books that Robert can nurture his interest, deepen existing areas of expertise, and expand his reading experiences. Through these books, he can engage in the present, develop a sense of competence, and provide himself with the appropriate reading challenges. These are vital conditions that scholars like Wilhelm and Smith (Citation2014) have emphasised as the linchpin of what encourages males to read and these are conditions that are important in Robert’s development of a reader identity.

Whether or not incorporating these types of books into the school’s reading instruction would have changed Robert’s relation to reading through his life span, is not possible to say based on this study. However, given the existing research in the field, it is reasonable to assume that a conscious inclusion of these texts with a clear connection to the local place and its specific social and cultural history would have created good conditions for Robert and his (male) classmates to be able to, and to even dare, consider themselves as readers of printed fiction (Asplund & Pérez Prieto, Citation2013, Citation2018; Comber, Citation2015) and join a reading community. As such, Robert’s story about his book collecting emphasises the importance of teachers’ interest in creating opportunities for all students to draw on interpersonal relationships that inform their literacy trajectories, and expand their repertoires as readers (Dutro, Citation2008).

In conclusion, the methodological and theoretical approach taken in this study highlights the practices of interacting with books on a physical level, and how these practices can set into play processes through which a rural working-class man can develop a reader identity, engage himself in an act of preserving a literary cultural heritage, and express nuanced versions of being a working-class male within the context of a small village in the Swedish countryside. Positioning himself as a reader, and as a man who engages in books, Robert does set into play identity construction processes that collide with the normative way of being a man in this specific context. Through a close look at this particular case of positioning and identity formation, this study illuminates the intersection of reading, identity and masculinity, while showing how a rural working-class man’s relation to reading aligns with and deviates from normative conceptions within the studied context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stig-Börje Asplund

Stig-Börje Asplund is Associate Professor at the Department of Educational Studies at Karlstad University in Sweden. His research interests include classroom interaction, processes of identity construction, and literacy practices, with a special focus on vocational education and on boy’s and men’s relationship to reading.

References

- Åberg, M., & Hedlin, M. (2015). Happy objects, happy men? Affect and materiality in vocational training. Gender and Education, 27(5), 523–538.

- Ahmed, S. (2010). The promise of happiness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Anderson, E. (2009). Inclusive masculinity: The changing nature of masculinities. New York: Routledge.

- Anderson, E. (2014). 21st century jocks: Sporting men and contemporary heterosexuality. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Andrews, M., Squire, S., & Tamboukou, M. (Eds.). (2013). Doing narrative research. London: Sage.

- Archer, M. S. (2007). Making your way through the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Areschoug, S. (2019). Rural failures: Representations of (Im) mobile young masculinities and place in the Swedish countryside. Boyhood Studies, 12(1), 76–96.

- Asplund, S-B., & Goodson, I. (2020). Between oral and written culture: An exploration of a Swedish working-class man's learning trajectory. 13:e konferensen om berättelseforskning, Karlstad University, 19-20 November, 2020.

- Asplund, S.-B., & Pérez Prieto, H. (2013). ‘Ellie is the coolest’: Class, masculinity and place in vehicle engineering students’ talk about literature in a Swedish rural town school. Children’s Geographies, 11(1), 59–73.

- Asplund, S.-B., & Pérez Prieto, H. (2018). Young working-class men don’t read. Or do they? Challenging the dominating discourse of reading. Gender and Education, 30(8), 1048–1064.

- Asplund, S. B., & Prieto, H. P. (2019). Approaching life story interviews as sites of interaction. Qualitative Research Journal, 20(2), 175–187.

- Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (1998). Local literacies. New York: Routledge.

- Bausch, L. S. (2014). Boys will be boys? Bridging the great gendered literacy divide. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Bloom, H. (2000). How to read and why. New York: Scribner.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction. A social critique of the judgment of taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1992). The logic of practice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2002). Habitus. In J. Hillier & E. Rooksby (Eds.), Habitus: A sense of place (pp. 27–34). Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Brozo, W. G. (2019). Engaging boys in active literacy: Evidence and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bull, J. (2009). Watery masculinities: Fly-fishing and the angling male in the south west of england. Gender, Place and Culture, 16(4), 445–465.

- Bye, L. M. (2009). ‘How to be a rural man’: Young men's performances and negotiations of rural masculinities. Journal of Rural Studies, 25(3), 278–288.

- Campbell, H., Bell, M. M., & Finney, M. (2006). Country boys: Masculinity and rural life. University Park, PA: Penn State Press.

- Comber, B. (2015). Literacy, place, and pedagogies of possibility. New York: Routledge.

- Duckworth, V., Husband, G., & Smith, R. (2018). Adult education, transformation and social justice. Education+ Training, 60(6), 502–504.

- Dutro, E. (2003). ‘Us boys like to read football and boy stuff’: Reading masculinities, performing boyhood. Journal of Literacy Research, 34(4), 465–500.

- Dutro, E. (2008). Boys reading American girls: What’s at stake in debates about what boys won’t read. In I. R. F. Hammet & K. Sanford (Eds.), Boys, girls & the myths of literacies & learning (pp. 69–90). Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Egginton, H. (2014). Book-hunters and Book-huntresses: Gender and Cultures of Antiquarian Book Collecting in Britain, c. 1880–1900. Journal of Victorian Culture, 19(3), 346–364.

- Flint, M. A. (2019). Hawks, robots, and chalkings: Unexpected object encounters during walking interviews on a college campus. Educational Research for Social Change, 8(1), 120–137.

- Frank, B, Kehler, M, Lovell, T, & Davidson, K. (2003). A tangle of trouble: Boys, masculinity and schooling-future directions. Educational Review, 55(2), 120–133.

- Garcia, C. M., Eisenberg, M. E., Frerich, E. A., Lechner, K. E., & Lust, K. (2012). Conducting go-along interviews to understand context and promote health. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1395–1403.

- Gee, J. P. (2010). A situated-sociocultural approach to literacy and technology. In E. A. Baker (Ed.), The new literacies: Multiple perspectives on research and practice (pp. 165–193). New York: Guilford.

- Gibson, C. (2016). How clothing design and cultural industries refashioned frontier masculinities: A historical geography of western wear. Gender, Place & Culture, 23(5), 733–752.

- Goodson, I. (2013). Developing narrative theory: Life histories and personal representation. London: Routledge.

- Goodson, I. (2014). Ancestral voices. In I. Goodson and S. Gill, Critical narrative as pedagogy (pp. 103–121). New York: Bloomsbury.

- Hammet, R. F., & Sanford, K. (2008). Boys, girls & the myths of literacies & learning. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Hearn, J. (2015). Men of the world. Genders, globalisations, transnational times. London: Sage.

- Hopkins, P., & Noble, G. (2009). Masculinities in place: Situated identities, relations and intersectionality. Social & Cultural Geography, 10(8), 811–819.

- Hoven, B. V., & Horschelmann, K. (2005). Spaces of masculinities. New York: Routledge.

- Ingram, N. (2011). Within school and beyond the gate: The complexities of being educationally successful and working class. Sociology, 45(2), 287–302.

- Ingram, N. (2018). Working-class boys and educational success. London: Palgrave.

- Janks, H. (2010). Literacy and power. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jenkins, R. (2002). Pierre Bourdieu. London: Routledge.

- Kirkland, D. E. (2011). Books like clothes: Engaging young black men withreading. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 55(3), 199–208.

- Kohler Reissman, C. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. London: Sage Publications.

- Massey, D. (2005). For space. London: Sage.

- Millard, E. (1997). Differently literate: Gender identity and the construction of the developing reader. Gender and Education, 9, 31–48.

- Mishler, E. G. (1999). Storylines: Craftartists’ narratives of identity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Newkirk, T. (2002). Misreading masculinity: Boys, literacy, and popular culture. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

- Persson, M. (2012). Den goda boken [The good book.]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Reay, D. (2002). Shaun’s story: Troubling discourses of white working-class masculinities. Gender and Education, 14(3), 221–234.

- Roberts, S. (2018). Young working-class Men in transition. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Scholes, L. (2018). Boys, masculinities and reading: Gender identity and literacy as social practice. New York: Routledge.

- Stahl, G. (2015). Identity, neoliberalism and aspiration: Educating white working-class boys. London: Routledge.

- Stahl, G. (2020). ‘My little beautiful mess’: A longitudinal study of working-class masculinity in transition. NORMA, 15(2), 145–161.

- Taylor, M.J. (2000). The anatomy of bibliography: book collecting, bibliography and male homosocial discourse. Textual Practice, 14(3), 457–477.

- Ward, M., Tarrant, A., Terry, G., Featherstone, B., Robb, M., & Ruxton, S. (2017). Doing gender locally: The importance of ‘place’ in understanding young men’s masculinities in the male role model debate. Sociological Review, 65(4), 797–815.

- Wilhelm, J. D., & Smith, M. W. (2014). Reading don’t fix no chevys (yet!) motivating boys in the age of the common core. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58(4), 273–276.

- Woods, M. (2010). Rural. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.