ABSTRACT

This study analyzes how men’s domestic cooking is represented and masculinized in cookbooks, written by men for men and published in 1975, 1992, and 2010, respectively. Departing from the concept of domestic masculinities, it uses the methods of Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis. It asks: what kind of values and ideas connected to men, food, and the home are realized in texts and images? And how are these legitimized and naturalized? As the study’s context is Sweden, a country known for its pursuit of gender equality, the study focuses on how men’s domestic cooking has been represented in cookbooks published roughly 20 years apart. The analysis shows that, while the first two books are characterized by a ‘real man’ discourse and working-class masculinity, the 2010 book represents a masculinity in line with a ‘new man image’ closely linked to consumption and materiality. However, structurally, there are few differences. Values associated with traditional middle-class masculinities, traditional gender norms, and gendered division of domestic labor are reproduced. Men’s cooking is recontextualized as a playful leisure activity. In all three books, cooking becomes another way for a man to appear successful – both in relation to other men and women, and in socioeconomic terms.

Introduction

Traditionally, men and masculinities are often constructed and represented in counterpoint to the home, for example, in relation to paid work and adventure (Szabo & Koch, Citation2018). This is also true when it comes to food and cooking. The man is often associated with professional cooking and artistry, while the woman is thought of as responsible for the daily, and less glamorous, cooking at home (Harris & Giuffre, Citation2015). The same kind of dichotomy has been found in cookbooks. Home cooking has mainly been linked to women. It has been associated with thriftiness and care for the well-being of other household members, as well as construed as a mundane chore linked to daily duties (Brownlie & Hewer, Citation2007; Inness, Citation2001; Leer, Citation2019). In contrast, men’s home cooking is represented as a leisure time activity that takes places on special occasions and is associated with artistry. It has, as Inness (Citation2001, p. 19) puts it, been treated as ‘cause for applause’.

In this paper, we examine how men’s domestic cooking is represented in three Swedish cookbooks, written by men for men and published in 1975, 1992, and 2010, respectively. The overall purpose is to discuss how these cookbooks masculinize domestic cooking, that is, how it is represented as part of a masculinized domestic culture. Previous research has taken an interest in the home as a place for men’s identity work, as well as in men’s increasing engagement with homemaking practices (e.g. Szabo & Koch, Citation2018). Studies show, as, for example, Hollows’s (Citation2002) study of representations of bachelors’ domestic cooking in 1950s Playboy magazines, that in homes where men live alone, domestic work and home creativity have long been linked to an identity where the home (and cooking) is a place for self-expression, materiality, and consumption. More recent studies of men’s actual experiences of domestic cooking display progressive expressions of masculinity (Neuman, Citation2020; Neuman, Gottzén, & Fjellström, Citation2017b); home cooking is not just about maintaining relationships with other men, but also a way for men to maintain heterosocial relationships and take on household responsibilities (Neuman, Gottzén, & Fjellström, Citation2017a). For some scholars, this increased engagement with domestic chores is associated with a particular lifestyle orientation reflecting a ‘new man image’, closely connected with consumerism (Aarseth, Citation2009) and a move towards ‘alternative masculinities’ (Szabo, Citation2014).

In line with Cappellini and Parsons (Citation2014, p. 73), we see cookbooks as important historical resources as they ‘offer insights into the axis of political, cultural and social context of their making’. In our case, the cookbooks offer a way to understand the representation of food, men, and domestic space at different times in a national context. They are cultural artefacts (Tobias, Citation1998) telling ‘cultural tales’ (Appadurai, Citation1988) and, as such, they contain ‘hidden clues and cultural assumptions about class, race, gender, and ethnicity.’ (Tobias, Citation1998, p. 3). The context of this study is Sweden, a country that has been put forward as ‘one of the most gender-equal countries in the world’ (Martinsson, Griffin, & Nygren, Citation2016, p. 3), and a place described as going through a process of de-feminization of home cooking (Jönsson, Citation2020). With this in mind, it is interesting to note that there is a lack of Scandinavian specific research concerning cookbooks and gender, although there are recent exceptions, for example, Kvaal (Citation2019). Using Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012), we analyze how domestic cooking is recontextualized in the three cookbooks. Taking the concept of domestic masculinities as a starting point (Gorman-Murray, Citation2008), the purpose is to explore how men’s domestic cooking is constructed in cookbooks published at different times in Sweden. Specifically, we seek to answer three questions: what kind of ideas, interests and values connected to men, food, and the home are realized in texts and images?; how are these legitimized and naturalized?; and what differences can be observed?

Cookbooks and gender

Most studies on cookbooks and gender have concerned cookbooks aimed at women. Through historical investigations, such as studies by Inness (Citation2001), Neuhaus (Citation2003), Tobias (Citation1998), Horner (Citation2000) and Bullock (Citation2012) of American and Victorian (British) cookbooks, we know that cookbooks from the end of the eighteenth century have functioned as a means of good housewifery and social distinction. The cookbook defined and positioned the role of the woman (and the man) in the bourgeoisie or middle-class society and offered advice about how to manage homes and families.

Studies conducted in recent periods, in other contexts and with, to a certain extent, other areas of interest, such as Appadurai’s (Citation1988) analysis of English-language cookbooks published in India (1960–1980), and Cappellini and Parsons’s (Citation2014) investigation of Italian cookbooks published in Britain (1954–2005), also emphasize the gendered, as well as the social and ethnic, character of cookbooks. These studies show that the gendered view of domestic cooking has changed over time. Cooking has been presented, as in Cappellini and Parsons’s (Citation2014) study, a way for urban middle-class women to climb socially (1954–1974), but also, as a coping strategy for working mothers (1975–1986) to, finally, in the early 2000s, no longer being considered an exclusively feminine question but instead part of a consumer lifestyle.

Studies carried out on more recently published cookbooks have mainly concerned the books of celebrity chefs. Matwick (Citation2017) demonstrates that, in cookbooks written by contemporary female celebrity chefs, a discourse that reproduces a traditional domestic femininity is still prevalent. Johnston, Rodney, and Chong (Citation2014) have also found celebrity chef cookbooks to be highly gendered, and that these can contribute to naturalizing inequalities.

As this short review shows, so far, most cookbooks published in the 19th and 20th centuries represent an idealized femininity: the white, middle-class housewife nurturing her family and friends. Cookbooks have, however, also been written to pursue social change and to question society’s expectations about gender roles, ethnicity, race, and social class (Inness, Citation2006).

Cookbooks for men

As Neuhaus (Citation2003) and Inness (Citation2001) show, cookbooks written for men by men are not a new phenomenon. In the USA, the first cookbooks addressing men were published at the beginning of the twentieth century, and during the post-war era in the 1920s, cookery instructions and cooking literature for men expanded. Research shows that these cookbooks maintain and reproduce the domestic divide represented in cookbooks aimed at women. Men cook for fun and of their own choice (Inness, Citation2001). More recent studies, for example, Nolen (Citation2020), show that men’s cookbooks distance men’s home cooking from women’s everyday cooking by presenting it as a way to approach women sexually or romantically, and to gain status among other men and women. Performed with creativity and at special occasions or under special circumstances, men’s domestic cooking is put forward as an optional hobby and part of men’s leisure time. On the other hand, everyday cooking, often portrayed as uninspired, tasteless, and boring, is represented foremost as women’s responsibility (Inness, Citation2001; Neuhaus, Citation2003; Nolen, Citation2020).

The construction of men’s cooking as a fun leisure (and lifestyle) activity is also demonstrated in studies of more recent cookbooks written by male celebrity chefs such as Jamie Oliver (Brownlie & Hewer, Citation2007; Hollows, Citation2003; Tominc, Citation2017). Cooking in his cookbooks, as well as in his television shows (cf. Hollows, Citation2003; Leer, Citation2013; Tominc, Citation2017), reaffirms domestic cooking performed by men as a leisure practice and as something easily mastered. It is constructed as a masculine activity using an everyday language and a laddish tone, as well as images that represent the domestic kitchen as a masculine space, a site of play and male friendship rather than work.

Previous research shows that men’s domestic cooking is constructed in cookbooks aimed at men in a way that assures that cooking can be a masculine activity, and not a threat to the male identity (Hollows, Citation2003; Neuhaus, Citation2003). Domestic cooking is also presented as if it has always been a masculine activity, which is performed with ‘manly knowhow’ and ‘rewarded with confidence, the respect of peers, and the admiration of women’ (Kelly, Citation2015, p. 202). Outdoor cooking is put forward as a special kind of manly cooking, and meat and alcohol as manly kind of foods. Men are to perform their special cooking outside and women are assigned to perform the more unimportant daily cooking indoors (Inness, Citation2001; Neuhaus, Citation2003). These truisms have also been valid outside an Anglo-American context. Reddy’s (Citation2016) study of foodways in two contemporary South African cookbooks also displays the barbecue as a type of homogenized and hetero-sexualized masculine activity organized around meat and fire. Kvaal’s (Citation2019) study of men’s cookbooks in a Norwegian context shows that, even if the rationale for men’s active role in the kitchen has changed throughout history, that is, from necessity to duty to desire, the cookbooks depict men’s cooking as different from women’s.

Theoretical starting points

Theoretically, we start from discourse theory and literature on the representation of food, masculinities, and the home. Concerning discourse theory, we follow van Leeuwen’s ideas and see discourse as a recontextualization of social practice (van Leeuwen, Citation2008). This means that we focus on how the social practice of domestic cooking is transformed into a cookbook discourse and how the producers of the selected books choose to represent men’s cooking through texts and images, the ‘doing of discourse’, and something that forms a script about cooking, that is, certain ways of understanding it (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012).

A second key influence is the tradition in masculinity research that deals with food, masculinities, and the home. Focusing on representations (Hall, Evans, & Nixon, Citation2013), we understand masculinity as ‘socially constructed, produced and reproduced’, varying and changing over time, space and within societies (Kimmel, Hearn, & Connell, Citation2005, p. 3). The political, social, and cultural changes of recent decades have increasingly linked men to the domestic space, while research has shown an increased interest in the intersection between masculinity and domesticity. This involves analyses of the ways in which home ideals and homemaking practices shape masculine identities, and how men’s involvement in the household changes the ‘discourses of home’ (Gorman-Murray, Citation2008, p. 369). It also includes an interest in the home as a place for men’s identity work (e.g. Aarseth, Citation2009; Gorman-Murray, Citation2015) and the role played by engagement in household chores such as cooking (e.g. Meah, Citation2014; Neuman et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Szabo, Citation2013, Citation2014; Szabo & Koch, Citation2018). Here, we also include studies on the representation of food and men in relation to domestic cooking in television shows, magazines, and cookbooks (e.g. Hollows, Citation2002, Citation2003; Leer, Citation2019).

Studying cookbooks published in 1975, 1992, and 2010, respectively, allows us to examine how domestic cooking is recontextualized as a gendered practice at different times in a Swedish context. Domestic cooking, defined as an ordinary, everyday activity, is a social practice where different masculinities are constructed, and power, authority, and gender relations play out. Research has shown that cookbooks contain a variety of masculinities and their conceptualizations, like, for instance, the gastrosexual new culinary man (Kelly, Citation2015), a hegemonic masculinity (Reddy, Citation2016), or the new man/the new lad (Hollows, Citation2003). In addition to different masculinities, research has also shown that masculinities are deeply connected to ethnicity, class, and sexuality (Kimmel et al., Citation2005). The forms of masculinities appearing in cookbooks are constructions of masculinities and, thus, invented categories, but they are, nevertheless, constructions providing ideas, values, and norms linked to men, masculinity, and cooking. Cookbooks, therefore, create a certain position for their readers from which cooking can be understood, legitimized, and, perhaps, carried out. Of course, and due to historical and societal conditions, masculinities are variable and changeable, as, for instance, the extensive discussion about the new man/new lad shows (cf. Gill, Citation2003; Hollows, Citation2002). This is part of the aim of this study, which analyzes how masculinities are constructed in Swedish cookbooks published roughly 20 years apart.

Methodology and data

Seeing discourse as a recontextualization of social practice implies that we look at the cookbook representations as a result of ‘processes of transformation’ (van Leeuwen, Citation2008; van Leeuwen & Wodak, Citation1999). Such transformations are essential in all forms of communication; the communicator must choose how to communicate and, thus, select the semiotic resources available for what is to be expressed. van Leeuwen (Citation2008) defines eight categories often involved in these processes: substitutions (some semiotic elements are replaced by others); deletions (some elements are deleted); rearrangements (the order of elements is changed); additions (new elements are added); reactions (participants’ subjective reactions to activities are represented); and purposes (which are added to activities). van Leeuwen (Citation2008) also points out that recontextualizations involve legitimations and evaluations of social practices. In addition to representing social practices, texts explain and legitimate (or de-legitimate and critique) these practices. They can also involve evaluations of these practices. In our analysis, we are primarily interested in legitimations as these are commonly used to justify, legitimize, or transform an existing practice (van Leeuwen & Wodak, Citation1999).

Our interpretive framework is based on the principles of Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012). Strategies used in the production of texts and images are known to be ideological and are used to shape representations of events, actions, participants, and attitudes for specific purposes (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012). MCDA offers a way to understand and analyze different communication modes to find hidden values, ideas, and interests (Machin, Citation2013). Using MCDA’s conceptual tools involves focusing on linguistic and visual elements as semiotic resources (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006; van Leeuwen, Citation2005) and identifying how the semiotic choices, and their combination, create meaning. In texts and images, this includes lexical choices and choices of visual elements that represent participants, settings, actions, and objects (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006). In this study, we analyze these choices to expose underlying ideas, values, and discourses linked to men, masculinities, and men’s cooking.

The data includes three Swedish cookbooks. Focusing on cookbooks written by men and aimed at men makes it possible to study, albeit in this genre, how men justify and legitimize cooking in interaction with other men. With the help of a local librarian, we searched the cookbook archive at the School of Hospitality, Culinary Arts, and Meal Science Library at Örebro University. We found a total of five cookbooks, all published between 1930 and 2010. Looking closer at these books, we found three books of a similar nature – they were written by men, aimed exclusively at men, and dealt with domestic cooking in general. Of the other two, one book addressed bachelors of both sexes (En ungkarls kokbok), and one focused on domestic cooking in relation to health and weight loss (Kokbok för män), and they were, therefore, excluded from the data.

The three cookbooks included in this investigation are:

Grabbarnas Stora kokbok: Vickningar, drinkar och vinberedning (The Guys’ Big Cookbook: Shakes, Drinks, and Wine Preparation), published in 1975 and written by Bobby Andström, an author and photographer who has primarily written fact books about Sweden and royalty.

Grabbarnas kokbok: precis som prinsessornas kokbok fast tvärtom (The Guys’ Cookbook; Just Like the Princesses’ Cookbook But Reversed), published in 1992 and written by three well-known men, a chef (Leif Mannerström), a journalist/author (Jan Guillou), and a professor of Criminology who is also a famous author (Leif G.W. Persson). All three often appear in the Swedish media.

Kung i köket: Imponera i köket med Svenska Kocklandslaget (King of the Kitchen: Impress in the Kitchen with the Swedish Culinary Team), published in 2010. The book is written by former members of the Sweden national culinary team, that is, Swedish chefs competing in international culinary championships.

These cookbooks contain different kinds of texts related to cooking. We analyze the texts addressing the reader with instructions and descriptions. These texts not only include advice about cooking, but also about grocery shopping, how to lay the table, how to serve the food, and how to make the meal a socially successful event.

Analysis

In what follows, we show how the texts recontextualize cooking to legitimate it as a masculine practice. We concentrate on the strategies of masculinization, that is, strategies aimed at constructing domestic cooking as a ‘manly activity’. It is through these strategies that the reader is positioned in relation to (domestic) cooking. This is a position based on a discourse that represents men’s cooking as playful, creative, and almost professional, which, at the same time, distinguishes it from women’s ordinary and everyday cooking.

Home cooking but still one of the ‘guys’

All three books explicitly link cooking to men in their titles through the lexical choices of guys/blokes [SW: grabbar] or king [SW: kung], demonstrating who they are targeting. However, this is also part of the main representation strategy used in the books, to create a ‘guyish’ atmosphere.

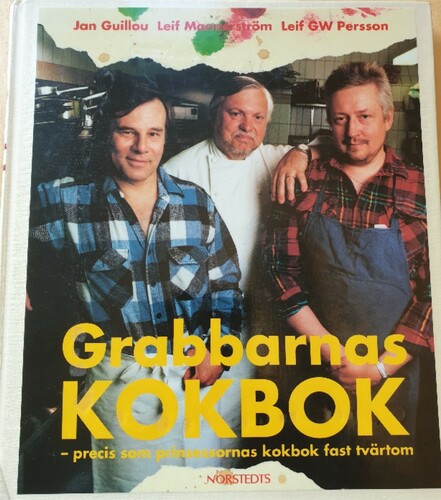

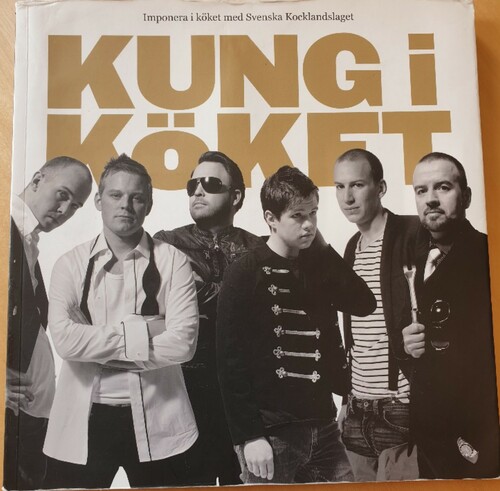

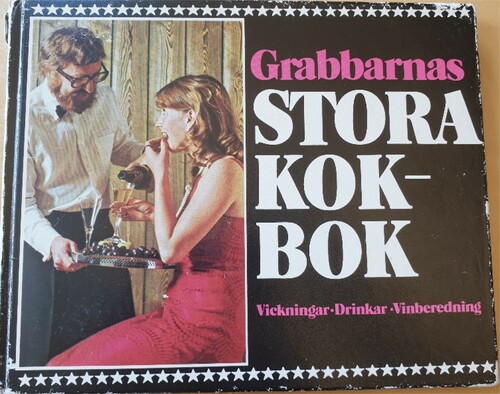

This is visually signified with men appearing on all covers. On the covers of the books from 1992 and 2010, the authors of the book, shown in and , are represented as a group facing the camera. On the cover from 1975, shown in , there is a man serving a woman a drink, a scene and setting indicating the book’s main aim of men’s home cooking (that is, to seduce women, see more below). The male cook is identified as a guy/bloke (SW: grabb) in the books of 1975 and 1992, and as a guy [SW: kille] and part of a gang (SW: gäng) in the 2010 book. The reader is addressed by a single personal pronoun you and an inclusive we, including the reader or men as a group, thereby constructing a relationship that Fairclough (Citation2015) describes with the term ‘synthetic personalization’.

In addition to the visual representations and the choice of words, such as men and guys, the books also use a communicative style or jargon that further constructs the ‘guyish’ atmosphere, for example, slang words of the time, a humorous tone, and certain metaphors. In the 1975 book, the author uses exclamations, rhetorical questions, and literary references to express a conversational, catchy tone. In addition, slang words of the time, such as booze (SW: kröka) and babe (SW: brud), occur alongside swearing. The 1992 book, in turn, uses a contrast between a formal, almost academic tone, created by the combination of word choice and the use of passive voice, to express everyday content for humorous effect, for example: ‘The little schnapps, whether acting alone or together with its comrades, must not be regarded as a single physiological phenomenon’ [SW: ‘Den lilla nubben, oavsett om han uppträder ensam eller i lag med sina kamrater, får icke betraktas som ett enskilt fysiologiskt fenomen’. p. 33].

In the 2010 book, metaphors derived from sports, war, and games are common, for example, when describing a dinner with the mother-in-law as: ‘Now you are in enemy land’ [SW: ‘Nu är du i fiendeland’, p. 32], encouraging the male cook to ‘love bomb’ [SW: ‘plusbomba’, p.32] the mother-in-law with flattering comments, and serve home cooked food since it is ‘a strong card to play’ [SW: ‘ett starkt kort att spela fram’, p. 32]. The metaphors combined with rhetorical questions, Swedish versions of English (urban) words, such as nörda (to nerd), katching! (ka-ching) and preppa (to prep), connote informality and hipness, creating a playful tone.

These types of discursive strategies create a distance from domestic cooking, while at the same time offering a cooking approach that legitimizes it as a male practice. This is particularly evident in the 1992 book, where humor is used to make the instructions appear less serious. The reader is, for instance, instructed to ‘never try to pour water from the pasta using a tennis racket even if you have seen it done in the cinema’ [ SW: ‘Försök aldrig att hälla av vattnet från pastan med hjälp av en tennisracket även om du sett det göras på bio’ p. 19].

The reader is, in all three books, addressed as a middle-class man. In the 1975 book, the reader is addressed through lexical choices as having sophisticated food habits, and being interested in travelling, beer brewing, fine wines, soul music, and parties. The assumed middle-class position becomes even more obvious when the reader is encouraged to visit other social settings to get certain food experiences. The reader is, for example, suggested to visit a typical working-class environment, such as the docks to eat simple, ordinary food (traditional Swedish pea soup). At the restaurant, the reader is encouraged to eat their meal with ‘the lads at the docks and surrounding coal and oil reserves [SW: ‘grabbarna från hamnen och omgivande kol- och oljelager’ p. 50] and listen to their stories. He is told that: ‘If you are lucky, you can get one or two good stories to bring home with you.’ [SW: ‘Har du tur kan du få en god historia eller två med dig hem.’ p. 50].

In the 1992 book, the reader is linked to a middle-class, or rather, a bourgeois setting. For instance, in the section suggesting drinks to have before the meal, the color of the proposed whisky is said to match ‘the gentlemen’s room’s oak-based walls, dark leather furniture, and crackling fire’ [SW: ‘herrummets ekboaserade väggar, mörka lädermöbler och sprakande brasa’ p. 9]. The reader is expected to be familiar with words like plebeian, with artists such as Monet and Courbet, and authors like Dumas (fils). However, the reader is also, as in the 1975 book, supposed to move beyond class boundaries and adapt to a working-class culture. This is the case when he is provided with cocktail recipes. One of those drinks is decorated with a slice of Falukorv, which is a well-known and cheap Swedish sausage, generally seen as a typical working-class food, and is supposed to be served to friends ‘who have both hair on the chest and tattoos’ [SW: ‘som har både hår på bröstet och tatueringar’ p.15].

However, in both the 1975 and 1992 books, working-class masculinity is put forward as a fundamental form of masculinity. This link is apparent in the introduction of the former book when a well-known poem by Dan Andersson, one of Sweden's proletarian writers, is quoted. The poem depicts how charcoal burners spend a weekend night. The quote goes: ‘We have fire, we have meat, we have spirits for comfort, here is weekend, deep in the tranquility of the forests!’ [SW: ‘Vi ha eld, vi ha kött, vi ha brännvin till tröst, här är helg, djupt i skogarnas ro!’ p. 5]. The quote is followed by a claim in which the author highlights the similarities between Dan Andersson’s ‘harsh forest people’ [SW: ‘kärva skogsfolk’] and ‘today's heroes who enjoy their whisky on the rocks in a bar dressed in leather and with music in stereo’ [SW: ‘dagens hjältar som dricker sin whisky on the rocks i en skinnklädd bar med stereomusik’ p5]. He states that: ‘Fire, meat and spirits, pale virgins … keywords in each man's life’ [SW: ‘Eld, kött och brännvin, bleka mör … Nyckelord i var mans liv’ p. 5].

To quote a proletarian poem may be typical of the time and the Swedish context, but these references also suggest that men, and their needs and desires, are the same and independent of socioeconomic context. This in turn implies that masculinity is something essential and that the male identity will not be threatened by cooking. This ‘real man’ discourse is even more prominent in the 1992 book through statements such as the one describing sharpening knives as a ‘very masculine occupation that one can advantageously devote to wearing checkered cotton shirt and rolled up sleeves’ [SW: ‘mycket manlig sysselsättning som man med fördel kan ägna sig åt iförd rutig bomullskjorta och uppkavlade ärmar’ p.22]. On the front cover from 1992, shown in , two of the authors are dressed in aprons and plaid flannel shirts, one of them with rolled up sleeves, one with his thumb inside the apron, and the third in his whites. They lean towards each other, which suggests a close, friendly bond between them, and they all face the camera, looking confident. Together these elements connote a traditional working-class masculinity, which is further stressed on the back of the book when the authors are described as ‘Sweden's roughest guys/blokes’ [SW: ‘Sveriges grövsta grabbar’]. Signs such as the ‘checkered flannel shirt’, ‘the rolled-up sleeves,’ and a ‘hairy chest’ are included, both visually and textually, to communicate that men can cook and enjoy food without sacrificing their masculinity. These connotations of working-class masculinity work to legitimize cooking; they suggest that, even if a man cooks, he does not lose his masculinity.

Although the reader is also addressed as a middle-class man in the 2010 book, it differs from the previous books. In this book, there are no connections to working-class culture, and it lacks explicit additions as to why cooking can be done by men without losing their masculinity. Instead, cooking is closely connected to consumption, linking to the readers’ socioeconomic status and purchasing power. This is mainly done through imperatives that encourage the reader to make purchases of new kitchen utensils. It is through consumption and materiality, by purchasing and using a professional steam oven, chic plastic boxes, and good-looking bowls, clearly associated with a middle-class lifestyle (Hollows, Citation2002; Shugart, Citation2014), domestic cooking becomes part of the (bachelor) homemaker’s self-expression (Gorman-Murray, Citation2008; Hollows, Citation2002). Here, we see instead a type of ‘new man’ (Gill, Citation2003); it is not about hairy chests and muscles, but about succeeding in socioeconomic terms and, thus, having the economic power and being able to afford the ‘right’ kitchen equipment.

This stylish and modern masculinity is also communicated visually. On the cover, shown in , the authors, who are all chefs, appear in a black and white group photo. The text on the back cover identifies them as the national team of chefs. The six men are wearing different outfits suitable for different social occasions, ranging from more ordinary, daily occasions to more festive events. They stand next to each other, looking in different directions; some of them are facing the camera, others not. None of them is smiling, as they try to look cool. There is no physical contact between them. Rather, the chefs stand in fashion-like postures. Even though they are all successful chefs, each of them appears as a guy among other guys. These choices construct a discourse that is clearly different from the ‘real man discourse’ that was expressed in the 1992 book. Instead, it is a representation that is in line with the contemporary representation of Swedish male celebrity chefs as progressive and ‘laid-back guys’ (Neuman, Citation2018).

Cooking as a means to impress men and seduce women

The main goal of men’s cooking put forward in all three books is either to impress friends and/or seduce women; cooking, thus, becomes a question of obtaining social recognition (Inness, Citation2001; Neuhaus, Citation2003; Nolen, Citation2020). Even if the cooking is located in a domestic setting, men’s cooking is not associated with everyday life, with hungry children, long queues at the supermarket, and monotonous cooking. Instead, the reader is assumed to cook for social purposes, for fine dining, or special social occasions.

In the 1975 book, cooking is primarily recontextualized, and legitimized, as a way to seduce women. The main reason for cooking at home is that a home-cooked meal is the best way to succeed with the aim of seduction: ‘A carefully thought-out LOVE MEAL rarely misses the intended effect – The Beauty ending up in the bed you thought her in!’ [SW: ‘En omsorgsfullt uttänkt KÄRLEKSMÅLTID missar sällan åsyftad verkan – Den Sköna hamnar i den bädd du tänkt henne i!’ p. 17]. The text also states that if the reader follows the instructions, he could start ‘planning the morning tray’ [SW: ‘tänka på hur morgonbrickan skall se ut’ p. 19]. This is because ‘the woman is probably not born who leaves a lover after such exercises at the table’ [SW: ‘För den kvinna är väl inte född som ger sig av från en älskare efter sådana övningar vid bordet’ p. 19]. Women appear as objects for male desire and cooking is constructed as more or less equated with sexual foreplay. The main purpose of the book, as it says on the cover, is to serve as a handbook for ‘guys of all ages, who want to surprise their soul beloved with an unforgettable meal’ [SW: ‘killar i alla åldrar, som vill överraska sin själs älskade med en oförglömlig måltid’]. Through lexical choices such heroine [SW: hjältinna], the Beauty [SW: den Sköna], chick/babe [SW: brud], and being described as ‘blood filled and warm’ [SW: ‘blodfylld och varm’ p. 5], women are an obvious target for male desire. In this context, the male cook is functionalized as a magnificent seducer [SW: storartad förförare], and lover [SW: älskare], and, thus, represented as sexually liberated and active.

This heterosexual masculinity is further stressed through the visuals included in the book, which emphasize women’s physical appearances seen through the male gaze. On the front of the book, shown in , we see a woman in a red dress who is being served champagne by a man. Her gaze is directed at the man and her mouth half-open as she puts a grape inside. The red color of the dress, and the half-open mouth connote sexuality and sensuality. The direction of her gaze in combination with the pose, the woman looking up at the man without tilting her head, creates the impression that the woman is enthralled by and appreciates the man’s efforts, also demonstrating that cooking is a successful path when men seek to attract women.

In the 1992 book, cooking is primarily about enjoying food together with other men, so-called real guys/blokes [SW: riktiga grabbar], brothers [SW: bröder], friends/guys/blokes ‘with hairy chests’ [SW: vänner/grabbar ‘med hår på bröstet’]; lexical choices that express a ‘real man’ discourse. The recipes are calculated for four people and emerge as being for the closest male friends. Words like comrades [SW: kamrater] or mates [SW: polare] indicate which people the reader should cook for.

While cooking aims to maintain a male community, it is also presented as an act of inspiration and creativity. The 1992 book starts by describing a scene in which the artist Gustave Courbet and the author Alexandre Dumas (fils) become friends due to their joy of food and cooking. The text depicts how the two stand in front of the stove ‘their sensitive noses sniffing over the iron pot’ [SW: ‘de välutvecklade näsorna sniffande över den stora järngrytan’ p. 7] with a glass of fine Bourgogne within reach. The creativity needed for cooking enjoyable food emerges as typical male ability; it is through men’s cooking and, as it says on the back cover, ‘the male creative joy in the kitchen’ [SW: ‘den manliga skaparglädjen i köket’] the best food is made.

Also in the 2010 book, cooking is a way to obtain social recognition, mainly from male friends. The kitchen has become a social space where the home chef can cook with his friends, enjoy the aromas, and drink something good. By achieving cooking skills, the reader can become ‘the gang's gastronomic centerpiece and oracle’ [SW: ‘gängets gastronomiska mittpunkt och orakel’ p. 21]. This happens either when friends gather on the couch to watch football or when barbecues take place. Notably, when women occur in the texts, they are identified as mother-in-law, girlfriend, little heart, and darling, thus appearing in female roles based on traditional relationships with men. Regardless, cooking is presented to achieve success, either it is about convincing the expectant mother-in-law of your suitability as a spouse or your dinner guest about a future relationship.

Although the reader is addressed to be cooking for fun and cooking appears as a leisure time activity, the books, nevertheless, stress the importance of being skilled and to make a good impression with food; men’s cooking is about being able to cook food that will be consumed with pleasure. This is indicated by phrases such as ‘king in the kitchen’ [SW: ‘kung i köket’], or ‘king at the grill’ [SW: ‘kung vid grillen’], and verbs such as impress [SW: imponera], shine [SW: glänsa], succeed [SW: lyckas], and show off [SW: briljera]. The connection to professional cooking and gastronomy plays a key role in the three books, and it is through such associations that a man can cook and still be a ‘real man’. It, thus, stands in stark contrast to thriftiness and cooking for the family’s wellbeing.

In the 1975 book, the reader is referred to as someone wanting to be a skilled cook and it is through gaining these skills that the reader can be successful in seducing women. In the latter two books, cooking is more associated with craftsmanship. It is through gaining cooking skills associated with professional cooking and gastronomy that the reader will be able to perform and impress his (mainly) male friends. In these books, the male cook is encouraged to practice, learn, and train to gain the needed skills.

In the 1992 book, the reader is addressed as someone who wants to appear a better cook than he is; although he can never become a fine chef, with the help of the book, he can become a decent amateur cook. Visual and textual instructions showing how to chop an onion in a ‘professional way’ [SW: ‘på ett professionellt sätt’ p. 34] or how to filet a fish ‘by a nice standard’ [SW: ‘hygglig standard’ p. 86] are included. Domestic cooking is legitimized by referring to the gender (and the authority) of world-famous chefs, as well as the gender and the ‘real man’-attribute of the authors themselves. As it says on the back cover, ‘The world's most famous chefs of all time were men! Now Sweden’s roughest guys/blokes continue that tradition and share their male knowledge with their brothers.’ [SW: ‘Världens genom tiderna mest berömda kockar var män! Nu fortsätter Sveriges grövsta grabbar den traditionen och delar med sig av sin manliga kunskap till sina bröder.’].

In the 2010 book, home cooking is equated with professional cooking, and professional cooking is recontextualized as primarily performed by men. The reader is functionalized and addressed as someone who, with practice, can become a chef. On the cover of the book, it says: ‘This is not a cookbook. This is a chef's book.’ [SW: ‘Det här är ingen kokbok. Det är en kockbok.’]. This is also reflected in the representation of the kitchen. In addition to a social space, the 2010 kitchen is represented as a place where the reader should display control, and a place that can be equipped so that it reaches a professional level. The book, thus, also accentuates kitchen equipment as crucial for a successful performance. Overall, stylishness is more prominent in this book than in the other two. It concerns both how the food is visually presented in the book and how the reader is asked to present the food to his guests. Emphasis is placed on making the food served look good. The word nice [SW: snygg] often comes back, for example, nice piles, a nice cutting board, and a nice table. It is clarified that pleasant arrangements of the food served will impress or surprise the guests.

The link between professional cooking and masculinity is obvious on the book cover shown in , in which the authors, all members of the national team of chefs, appear. Women are evidently not included in this successful group of chefs. In connection with the book’s various sections, the current chef presents himself, dressed and posing in a way that suits the social occasion for which the cooking is intended. In the section entitled ‘in the middle of the match’, shown in , the chef Fredrik Björlin appears in a plaid shirt in a boxing pose. The choice of clothes and position indicates that a man can undoubtedly cook and still be a man.

Food and drink for men

The foods and drinks that the home chef and his guests are expected to prepare and consume also reflect a masculine ideal. This is especially apparent in the two older books. So-called Swedish homemade food, ‘old honest domestic dishes’, described as ‘Food for men’ in the 1975 book, has a special position; the cook is not supposed to prepare fat-reduced vegetable dishes. Men ‘who wander between life’s set tables in search of crossed radishes on a mirror of green sauce’ [SW: ‘som irrar mellan livets dukade bord på jakt efter korslagda rädisor på en spegel av grön sås’ p. 8], as stated in the 1992 book, are not included in the group of ‘real men’ who together will enjoy the food. In this book, dishes are also named in a way that signals that they are suitable for men, for example ‘The guys’ anchovy toast’ [SW: ‘Grabbarnas ansjovistoast’ p. 14].

However, the 2010 book reflects a different perspective. Now it is not so much about what food the home cook should cook as raising the degree of difficulty in the dishes he cooks. The reader is suggested to cook a variety of foods, such as chicken, beef, fish, vegetables, and sweet desserts, that do not clearly indicate a male identity. However, serving ‘beef, béarnaise sauce, and salad’ at the grill is considered too simple; instead, the reader is encouraged to ‘increase the difficulty’ in his cooking. When a more traditional domestic dish is put forward, it is presented as something that suits the mother-in-law, not the modern man and his group of friends, since traditional homemade food makes the domestic chef appear as ‘good marriage material’ [SW: ‘dugligt giftasmaterial’ p. 32].

Alcohol has a prominent position in the two older books. Of the 1975 book’s 61 pages, just over half is about alcohol, for example, how to flavor liquors and vodka, how to make your own wine, and how to brew beer. Even the meaning of cooking in the title, ‘cookbook’, is dual as it also relates to making vodka.

The amount of text dedicated to alcohol and alcohol consumption indicates that alcohol in the 1970s, as well as in the 1990s, constituted a large part of social life and, thus, constituted a central part of men’s cooking as well. Drinking is put forward as part of man’s cooking and important for a man’s identity, for example, the 1995 book encourages the reader to avoid ‘sweet pastel colored junk’ if he is not a ‘woman’ or a ‘Colombian drug dealer’ and, instead, choose wine, beer, and schnapps, the latter referred to as ‘a little rascal’ [SW: ‘en liten rackare’]. But in addition to this type of tip, there are also sections in both books that encourage the reader to curb alcohol consumption. In the book from 1975, this is justified, for example, by the fact that consumption is linked to both the risk of drunk driving and poor sexual performance.

Alcohol is also included in the 2010 book but not as prominently as in the other books, nor is it so clearly associated with a masculine identity. Instead, the suggestions concern which alcohol is suitable for which food. The fact that all dishes are combined with suggestions for alcoholic beverages makes it, however, clear that men cook for special occasions or circumstances.

Conclusion

Our results are in line with previous research in this area. The three cookbooks represent domestic cooking as a highly gendered and heterosexual practice and they tend to reproduce values associated with a traditional form of middle-class masculinity, traditional gender norms, and division of domestic labor. Men's cooking is generally recontextualized as a playful, creative leisure activity; men, thus, enter the home kitchen with the aim of entertaining male friends or seducing and/or impressing women, which legitimates it as a masculine practice (Inness, Citation2001; Neuhaus, Citation2003; Nolen, Citation2020). Such representations are based on implicit norms dictating that the everyday domestic cooking and care for the family is a female practice (Inness, Citation2001; Leer, Citation2019); men's domestic cooking is, thus, detached from any household responsibilities. Instead, it is put forward as part of a successful middle-class lifestyle (Kvaal, Citation2019) and part of the modern (male) homemaker’s self-expression (Gorman-Murray, Citation2008; Hollows, Citation2002). In this way, and through the ‘guyish’ tone in the books, domestic cooking does not come across as a threat to male identity (Hollows, Citation2003; Neuhaus, Citation2003).

The analysis, however, displays some differences between the books. In contrast to the two oldest books, the 2010 book lacks explicit additions legitimating why cooking can be done by men without losing their masculinity. Furthermore, while the older books are characterized by a ‘real man’ discourse, nurtured by its link to working-class masculinity as a fundamental form of masculinity and connecting men’s cooking to traditional kinds of food and a high-level alcohol intake, the 2010 book constructs an alternative form of masculinity which is not about physical attributes such as a hairy chest and muscles. This man appears as more inclusive, more in line with a ‘new man image’ (Aarseth, Citation2009; Gill, Citation2003). It is a masculinity that is constructed as closely linked to stylish consumption and consumption culture (Aarseth, Citation2009), rather than associated with working-class culture.

However, despite these differences in how men’s cooking is recontextualized in the books, the analysis shows an unchanged need to legitimize men’s domestic cooking as a masculine practice, although this could be achieved in more subtle ways as in the 2010 book. Even though a more inclusive form of masculinity emerges in this book, we find that, despite decades of gender equality work, a discourse reproducing traditional gender norms and division of domestic labor prevails in these kinds of cookbooks.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers’ valuable comments and recommendations on this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Helen Andersson

Helen Andersson is a Senior Lecturer in Media and Communication Studies at Örebro University, Sweden. Her research interests include food communication, nature, place and space, multimodality, and critical discourse analysis.

Göran Eriksson

Göran Eriksson is a professor of Media and Communication studies at Örebro University, Sweden. He works in the field of discourse analysis and his current research is linked to the sociology of health and is concerned with multimodal representations of healthy food and healthy eating in different settings. Ongoing studies look at marketing and are especially interested in how science and scientific expertise is communicated.

References

- Aarseth, H. (2009). From modernized masculinity to degendered lifestyle projects. Men and Masculinities, 11(4), 424–440. doi:10.1177/1097184X06298779

- Appadurai, A. (1988). How to make a national cuisine: Cookbooks in contemporary India. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 30(1), 3–24. doi:10.1017/S0010417500015024

- Brownlie, D., & Hewer, P. (2007). Prime beef cuts: Culinary images for thinking ‘men’. Consumption Markets & Culture, 10(3), 229–250. doi:10.1080/10253860701365371

- Bullock, A. (2012). The cosmopolitan cookbook. Food, Culture & Society, 15(3), 437–454. doi:10.2752/175174412X13276629245966

- Cappellini, B., & Parsons, E. (2014). Constructing the culinary consumer: Transformative and reflective processes in Italian cookbooks. Consumption Markets & Culture, 17(1), 71–99. doi:10.1080/10253866.2012.701893

- Fairclough, N. (2015). Language and power (third edition ed.). London and New York: Routledge.

- Gill, R. (2003). Power and the production of subjects: A genealogy of the New Man and the New Lad. The Sociological Review, 51(1_suppl), 34–56. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2003.tb03602.x

- Gorman-Murray, A. (2008). Masculinity and the home: A critical review and conceptual framework. Australian Geographer, 39(3), 367–379. doi:10.1080/00049180802270556

- Gorman-Murray, A. (2015). Twentysomethings and twentagers: Subjectivities, spaces and young men at home. Gender, Place & Culture, 22(3), 422–439. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2013.879100

- Hall, S., Evans, J., & Nixon, S. (2013). Representation (2. Ed. ed.). London: SAGE.

- Harris, D. A., & Giuffre, P. (2015). Taking the heat: Women chefs and gender inequality in the professional kitchen. New Brunswick, New Jersey: New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Hollows, J. (2002). The bachelor dinner: Masculinity, class and cooking in playboy , 1953-1961. Continuum, 16(2), 143–155. doi:10.1080/10304310220138732

- Hollows, J. (2003). Oliver's twist. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 6(2), 229–248. doi:10.1177/13678779030062005

- Horner, J. R. (2000). Betty Crocker's picture cookbook:. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 24(3), 332–345. doi:10.1177/0196859900024003006

- Inness, S. A. (2001). Dinner roles: American women and culinary culture. Iowa: Iowa: University of Iowa Press.

- Inness, S. A. (2006). Secret ingredients: Race, gender, and class at the dinner table. New York: New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Johnston, J., Rodney, A., & Chong, P. (2014). Making change in the kitchen? A study of celebrity cookbooks, culinary personas, and inequality. Poetics, 47, 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2014.10.001

- Jönsson, H. (2020). Svensk måltidskultur. Carlsson.

- Kelly, C. R. (2015). Cooking without women: The rhetoric of the New culinary male. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 12(2), 200–204. doi:10.1080/14791420.2015.1014152

- Kimmel, M. S., Hearn, J., & Connell, R. (2005). Handbook of studies on men & masculinities. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE.

- Kress, G. R., & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (2nd. ed.). London: Routledge.

- Kvaal, S. (2019). Om mat og menn. Tidsskrift for Kjønnsforskning, 43, 288–305. doi:10.18261/issn.1891-1781-2019-04-04

- Leer, J. (2013). Madlavning som maskulin eskapisme: Maskulin identitet i The naked chef og spise med price. NORMA, 8(1), 43–57.

- Leer, J. (2019). New nordic men: Cooking, masculinity and nordicness in rené redzepi’snomaand claus meyer’salmanak. Food, Culture & Society, 22(3), 316–333. doi:10.1080/15528014.2019.1582250

- Machin, D. (2013). What is multimodal critical discourse studies? Critical Discourse Studies, 10(4), 347–355. doi:10.1080/17405904.2013.813770

- Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis: A multimodal introduction. London: Sage.

- Martinsson, L., Griffin, G., & Nygren, K. G. (2016). Challenging the myth of gender equality in Sweden (1 ed. Vol. 57544). Bristol: Policy Press.

- Matwick, K. (2017). Language and gender in female celebrity chef cookbooks: Cooking to show care for the family and for the self. Critical Discourse Studies, 14(5), 532–547. doi:10.1080/17405904.2017.1309326

- Meah, A. (2014). Reconceptualising ‘masculinity’ through men's contributions to domestic foodwork. In A. a. H. Gorman-Murray, P. (Ed.), Masculinities and place. Gender, space and society. (pp. 191-208). Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd..

- Neuhaus, J. (2003). Manly meals and mom's home cooking: Cookbooks and gender in modern America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Neuman, N. (2018). An imagined culinary community: Stories of morality and masculinity in “Sweden - the new culinary nation”. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(2), 149–162. doi:10.1080/15022250.2017.1338616

- Neuman, N. (2020). Foodwork as the New fathering?. Culture Unbound, 12(3), 527–549. doi:10.3384/cu.v12i3.3249

- Neuman, N., Gottzén, L., & Fjellström, C. (2017a). Masculinity and the sociality of cooking in men’s everyday lives. The Sociological Review, 65(4), 816–831. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12420

- Neuman, N., Gottzén, L., & Fjellström, C. (2017b). Narratives of progress: Cooking and gender equality among Swedish men. Journal of Gender Studies, 26(2), 151–163. doi:10.1080/09589236.2015.1090306

- Nolen, J. A. (2020). Recipes for change? Patriarchal and progressive masculinities in cookbooks for Men. Men and Masculinities, 23(2), 326–347. doi:10.1177/1097184X17739068

- Reddy, V. (2016). Masculine foodways in two South African cookbooks:springbok kitchen(2012) andbraai(2013). Agenda (durban, South Africa), 30(4), 46–52. doi:10.1080/10130950.2017.1304624

- Shugart, H. A. (2014). Food fixations. Food, Culture & Society, 17(2), 261–281. doi:10.2752/175174414X13871910531665

- Szabo, M. (2013). Foodwork or foodplay? Men’s domestic cooking, privilege and leisure. Sociology, 47(4), 623–638. doi:10.1177/0038038512448562

- Szabo, M. (2014). ““I'm a real catch”: The blurring of alternative and hegemonic masculinities in men's talk about home cooking. Women's Studies International Forum, 44, 228–235. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2013.08.003

- Szabo, M., & Koch, S. L. (2018). Food, masculinities, and home: Interdisciplinary perspectives. London, New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Tobias, S. M. (1998). Early American cookbooks as cultural artifacts. Papers on Language & Literature, 34(1), 3.

- Tominc, A. (2017). The discursive construction of class and lifestyle: Celebrity chef cookbooks in post-socialist Slovenia. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.

- van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and practice: New tools for critical discourse analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- van Leeuwen, T., & Wodak, R. (1999). Legitimizing immigration control: A discourse-historical analysis. Discourse Studies, 1(1), 83–118. doi:10.1177/1461445699001001005