ABSTRACT

Over a period of eight years, in order to apply for asylum on mainland Greece most applicants had to first pre-register by calling the Greek Asylum Service on Skype. Due to issues of capacity and political will, the Skype calls were most frequently ignored, and applicants often continued calling without response every week for months to years in the hopes of receiving international protection, documentation, and social benefits. This paper explores the experiences of a handful of men who called on Skype with no response and decided to exit the system. In particular, it theorizes these exits as political acts of refusal that generate new possibilities of masculine self. Building upon doctoral fieldwork conducted in Athens, Greece, the paper discusses the challenges posed to masculinity by a technologized border regime that forced individuals to face digitalized alienation and erasure, considering the strategies that men employed to contest the system and safeguard their masculinities. The article contributes to refugee studies, critical studies of men and masculinities, and studies of digital bordering.

Introduction

In recent years, scholarship has increasingly focused on refusal as a distinct but related act to resistance. Following Audra Simpson’s, Citation2014 monograph conceptualizing the assertions of sovereignty by Mohawk peoples as political acts of refusal to acknowledge the authority of settler-colonial states, several scholars have employed refusal as a key analytic. Though different scholars give varying meanings to the term, they all differentiate refusal from resistance, with resistance accepting a hierarchical power dynamic between the resisting oppressed and the resisted oppressor, and refusal asserting a relationship of equals (McGranahan, Citation2016). Bhungalia (Citation2020, p. 389) articulates this difference as ‘I oppose you’ (resistance) vs. ‘your power has no authority over me’ (refusal). In synthesizing refusal literatures, Prasse-Freeman (Citation2022, p. 1) distills the distinction to: ‘Resistance describes opposition to direct domination (sovereign modes of power, following Foucault’s schema), refusal describes the disavowals, rejections and manoeuvrings with and away from diffuse and mediated forms of power (governmentality).’

The literature largely focuses on settler-colonial contexts, often with respect to indigeneity. However, theorization has rarely been extended to forced migration (for an exception, see Newhouse, Citation2021). This article applies refusal to the study of migrant masculinities, focusing on the experience of racialized men who chose to exit an emasculating system of asylum pre-registration used in Greece between 2014 and 2022. With this system, asylum seekers who were not considered particularly vulnerable had to pre-register by calling the Greek Asylum Service on Skype. Due to issues of capacity and political will, the calls were most frequently ignored, and applicants regularly continued calling without response for months to years in the hopes of receiving international protection, documentation, and social benefits. This article interrogates individual decisions to exit this system, framing them as agentic strategies that illuminate refusal as an act of masculine fortification.

Building upon literature that establishes refusal as an agentic exercise generative of new possibilities and realities, the following analysis recasts the actions of individuals who seemingly gave up on the Skype system not as erosions of personal will or strength, but instead as a politics of refusal in which men refused to submit to digital bordering whose violence manifested through erasure and emasculation. I argue that in the case of exiting the Skype system, refusal generated new personal and geographic possibilities, allowing men to safeguard their desired senses of masculine self. Refusal constituted a strategy employed by migrants and asylum seekers to shield themselves from the border regime’s violence, and I find that their embrace of non-recognition kindled meaningful processes of self-recognition. However, I also find their refusals to be incomplete, complex, and at times contradictory, stabilizing masculinities while simultaneously destabilizing them by sustaining binding resignation to ‘illegality’ (De Genova, Citation2002).

By centering the interaction of bordered men and border technologies, this paper contributes to the study of agency and masculinity: the lens of refusal allows understanding of how racialized men experience, make meaning of, internalize, and ultimately contest bordering practices at an intimate level, with gendered refusals illuminative of migrant masculinities.

Methods

This article draws primarily upon three months of fieldwork conducted in Athens, Greece, during 2021. The research was based at FORGE for humanity, an NGO that supports migrant and asylum seeking men traveling solo. I previously volunteered at FORGE in 2018, and stayed involved with the staff and community in the years since, returning in September 2021 to engage in participant observation around all aspects of the NGO but specifically their Skype service. FORGE provided laptops and WiFi for individuals attempting to register for asylum, and I organized daily Skype sessions, setting up laptops, explaining the system, and calling alongside applicants.

My data stem from 32 hours of observing Skype calls, months of informal conversation, and 19 unstructured interviews with applicants in which I invited the men to reflect upon their experiences calling on Skype and navigating the asylum system in Greece. The interviews were with men from Sierra Leone (6), Afghanistan (4), Congo (3), Pakistan (2), Syria (1), Russia (1), Gambia (1), and Guinea (1), while sessions included individuals also from Mali, Togo, Cameroon, and Iran. The majority of my participants were in their twenties, though some were in their thirties and forties. Sessions and interviews were conducted in English and, with the paid support of interpreters from the community, French, Farsi, Pashto, Arabic, Urdu, and Punjabi. Interviews were self-transcribed and coded thematically and dramaturgically (with a focus on affect, tension, and strategy) using NVivo software, after which I analyzed emergent themes and revisited them in subsequent interviews. The men quoted in this piece chose their own pseudonyms.

The Skype system

Digital technologies proliferate within border enforcement and migration governance, with digital tools increasingly central to efforts of detection, identification, confinement, exclusion, and expulsion (Scheel, Citation2019; Van Houtum, Citation2021). Drone and satellite surveillance of migratory routes, biometric databases of registration and identification, bone and iris scanning, unmanned aerial and maritime vehicles, and the data mining and social media monitoring of online identities are just some of the many ways digital infrastructures govern both movement and those on the move (Latonero & Kift, Citation2018; Nedelcu & Soysüren, Citation2022). Border control can be considered a ‘fully fledged policing activity’ (Marin, Citation2011, p. 132), enacted through internal regulation, externalization, and a bricolage of digital bordering techniques.

Greece in particular has embraced digital bordering. As a frontline state, Greece holds immense practical and geographic importance to European Union border control, and the small country has innovated and improvised with technology in novel and untested ways, exhibiting an approach of ‘experimentality’ (Aradau, Citation2022) that shapes what Tazzioli (Citation2019) calls the ‘Greek migration laboratory.’ A key experiment in this laboratory involves Skype video calls. In 2014, the Greek Asylum Service piloted a new system for the registration of asylum seekers on mainland Greece and islands not considered ‘hotspots.’ Previously, applicants would queue outside the Asylum Service office to lodge their claims, but with the new system, most applicants were made to pre-register on Skype before actually lodging their claim in person (with exceptions applying to those whose mother tongue was not listed on the Skype timetable and those who could prove severe vulnerability).

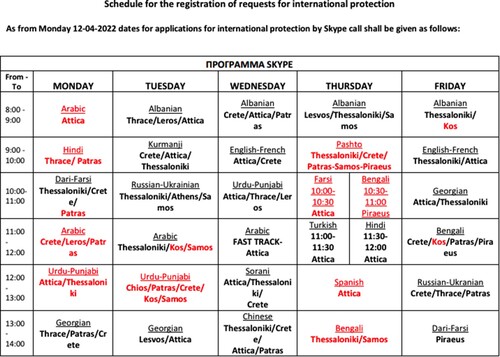

This system continued until August 2022, when it was abruptly discontinued and replaced with an appointment booking website.Footnote1 In theory, applicants could video call the Asylum Service on Skype to receive an appointment for their application lodging: at that appointment, they could pick up their asylum seeker card (colloquially called the white card), which grants temporary protection from arrest and detention and affords access to public hospitals and other social benefits. In practice, however, the system was wildly inaccessible and deficient. As laid out in a schedule published by the Migration Ministry, applicants could only call during limited hours, according to their mother tongue and location of residence ().

Whether due to capacity issues, an intentionally restrictive design, or both, the vast majority of calls went unanswered. Over the course of my fieldwork, I observed migrants and asylum seekers make 8,835 Skype calls, of which nine were answered (0.1% response rate). Without reply, would-be applicants were left in limbo: unable to get through on Skype, they could not initiate (or reinitiate) their asylum process, nor could they obtain a white card, AMKA (social security number), or AFM (a tax identification number), which blocked their access to hospitals and legal employment while leaving them liable to arrest and detention.

Joining others in conceptualizing migrant and asylum seekers’ quotidian encounters with structurally violent bureaucratic processes as illuminative of governance and subjectivity (Cabot, Citation2014; Tuckett, Citation2020), I am interested not only in how the Skype system erected ‘intangible internal borders’ (Artero & Fontanari, Citation2021, p. 636), but how men internalized and made sense of digital bordering whose violence manifested as absence, nonattending, and nonrecognition. Almost all of my participants referred to the Skype system as a form of psychological torture, citing its inscription of forced dependency, powerlessness, and humiliation as particularly harmful. Overwhelmingly, the men experienced unanswered calls as painful personal rejection.

Omid, an asylum seeker from Iran, noted that ‘Skype is like when your girlfriend breaks up with you and you call her and call her, but she doesn’t want to talk to you, so she just ignores.’ Prince Meddo, a torture survivor and asylum seeker from Sierra Leone, said: ‘If you are sitting close to a phone and seeing a phone call for the past two-three years, you have been seeing the same call, Prince Meddo, Prince Meddo, Prince Meddo, and you don’t pick it, why? Do you have any problem with that person in particular? Do you have any problem with him, or the name? The nationality? The color?’

Participants from African countries often suggested that ‘Skype’ only answered calls from white applicants (by white they meant people from the Middle East or Asia), but not for Black applicants, ignoring calls on the French-English line while answering on Arabic, Farsi, and others. ‘Skype is racist!’ proclaimed Prince Meddo and his Sierra Leonean friend Abdul Karim. My Pakistani participants, meanwhile, vehemently believed that they would not receive a reply on Skype but that people from the Middle East would. This intra-group bordering emerged between all of the men I worked with.

An emergent scholarship considers racialized migrant men and the politics of desire; migrant men are often seen as too brown, too Muslim, or too dangerous for Western partners, and in an intimate realm of their lives, they experience rejection through the digital interface of online dating (Shield, Citation2019). Here too migrants receive a technologized rejection, but instead of their desirability being rejected, their claims to suffering and personhood are rejected.Footnote2 Some experience this as a racialized process, viewing the pre-registration system as exclusionary towards certain bodies upon which borders demarcate the racialized Other. Much like those who face rejection on dating apps, these men perceive themselves as desirable until reminded on a digital platform of their undesirability.

The racial relevance of this border becomes especially visible in the wake of welcoming discourses and policies that underscore the extreme desirability of Ukrainian refugees in Europe compared to that of non-white and non-Christian refugees: within this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that after Russia invaded Ukraine, Ukrainian refugees in Greece were not to call on Skype, and could pre-register in person on an expedited pathway designed just for them. The Skype system joins other digital bordering techniques that have pointedly racializing effects (Parmar, Citation2019; Citation2020), emerging as a novel digital border employed by the Greek state to articulate race, (non)belonging, and exclusion.

The personal negation experienced on Skype was implicated not only in racial bordering but also the erosion of masculine self. One of the biggest frustrations I heard from participants was that the Skype system prevented them from working and earning livelihoods: stable employment and ‘breadwinner’ status are widely recognized as key pillars of successful manhood, yet without reply on Skype, individuals could not access formal labor. Literature on migrant masculinities highlights that whilst migration can be an act of hope, it can also engender feelings of failure and hopelessness; migrant and asylum seeking men often grapple with a disorienting loss of status, power, and control that challenges the (hegemonic) masculine standards they prize (Jaji, Citation2009; Kukreja, Citation2021).

The Skype system was highly disempowering to applicants of any gender identity: it stole time, imposed affective rhythms, and inscribed powerlessness and dependence. However, without disregarding the experiences of women and nonbinary applicants, my research suggests that men experienced the system as uniquely arduous, as they felt it insulted and posed challenges to their masculinities. The system forced men to continually de-base themselves by returning to seek validation of suffering and personhood that would unlikely come, all while inscribing borders across the city and self by foregrounding race and barring access to social services and formal employment. The Skype system can thus be considered an emasculating technology. Could refusal provide redress?

Scholars theorize refusal as a productive act that generates new political possibilities and subjectivities. McGranahan (Citation2016) outlines how the refusal of displaced Tibetans to accept refugee status in South India generates claims of future Tibetan statehood and citizenship, while Bhungalia (Citation2020) discusses how refusal to perform fear allows Palestinians to laugh in the faces of their Israeli oppressors, generating reclamations of joy and assertions that Palestinian affectivities are outside the reach of the apartheid state. In a completely different context, Sobo (Citation2016) highlights how in refusing to vaccinate their children, anti-vax parents produce new social affiliations and ethical performances. In each case, refusal is understood as abstention rather than opposition, and a means of forging political or social reinvention with an eye towards new possibilities of being.

A politics of refusal illuminates the logic of migrants and asylum seekers who decided to exit the Skype system. While in the field, I regularly observed that the individuals would gradually – or quite quickly – stop calling on Skype. Many told me that they used to have the Skype app on their phones but had since deleted it. ‘I tried a lot with Skype when I first came,’ said one of my Farsi interpreters from Afghanistan, ‘but nobody answered my calls so I deleted [it].’ Izmo, an asylum seeker from Sierra Leone, told me that he shares a room with seven undocumented men, all of whom had removed Skype from their phones: ‘They said ‘‘this app is occupying space in my phone, and I’m trying to call [but] they’re not picking my call, so it’s better to delete it.”’ Raja, an asylum seeker from Pakistan, told me it’s rare to meet someone who still has the app, because people are ‘tired.’ Sayyid, an asylum seeker from Afghanistan, certainly sounded tired as he explained that, ‘I tried once, twice, more than a hundred times, but nobody answered. Then I deleted the Skype.’

Throughout my fieldwork, it became clear that people ‘deleted the Skype’ in more ways than one, discarding not only the software from their mobile devices but also the system from their lives. The following analysis approaches these deletions as telling examples of masculinities in transition. In repudiating digitally mediated state violence, refusal initiated personal projects of masculine reinvention.

‘I need to find another way’: Refusal as Regaining Control

Over the remaining thirty minutes I spent with Junior, he outlined a choice of refusal that was motivated by a sharp desire to take control of his life. As he swatted at flies, Junior articulated his refusal through masculine registers, framing his decision as an empowering and subjectifying act with implications on his survival, masculine self-concept, and imagined future(s). I reproduce his account at length:

S: How did you decide to stop?

J: I’ve been trying and they are not picking. Like I said, it’s discouraging. So I said ‘ok, let me just leave anything, whatever happens, happens. That’s my fate. If I have another way, I will try. I will look for a part time job, try to make something of myself, I need to find another way.’ … As a young man I decided ok, let me leave this one and try.

No one is there to help you. And I am a young man. I need to step up. I’ve been through a lot, seriously, but I still have life, I still have hope. Yeah! So I decided let me start, let me try something else, let me forget about Skype. They are not picking my calls, let me leave everything. I have to encourage myself, I have to talk to myself to be strong again. It’s not over.

How old are you?

I’m 35 now. So I’m a young man, I’m strong, and I can do work. So let me look for something, let me keep my life. Because if I continue to stay in that depression, it will just keep me down. It will go from bad to worse, and if you go to worse, it’s too bad because these people don’t care. So you don’t allow yourself to go down there, you have to stand up. That’s what I did. No support from them. Nothing nothing, my brother … from the present state I have to lift myself up. That’s what I think other young men should be doing, lift themselves up and try to do something else with our lives. By doing something else you hope you have a future.

I decided to do more than to just give up … Forgetting about them [Skype] at the moment and looking for something else to do with my life, do with my time, that really makes me a man. I feel really proud of myself. As a man you must do something, as a young man you must find a way to make it happen, you know? You cannot just sit and waste the rest of the day just like that, hoping on a response from Skype, hoping for them to pick your call and give you an appointment and go for registration so you can start life all over again. If they are not picking, then you need to look for something else to do. So for me, that really makes me a man and I’m so proud of myself for taking this step.

I recounted Junior’s testimony at such length to illustrate refusal as a potent strategy to claim control in disempowering settings. For Junior, to stop calling was not giving up, but refusing to give up on the man he wanted to be. In doing so, he inscribed himself, and not the state, with power, refusing the Skype system – and Greece by proxy – as the ultimate authority over him. In this way, Junior engaged in an ironically mirrored politics of nonrecognition: the state refused to recognize Junior, and Junior refused to recognize the state. Instead he chose to recognize himself, and to draw from that self-recognition strength, purpose, and masculine meaning.

Several of my participants similarly characterized their exits from the Skype system as strategies to help them live up to culturally-specific masculine obligations. Take for instance Raja, an affable 24-year-old from Pakistan. Following our second session together, he told me that he’d like to share his story, so we met in Victoria Square, a pen in my hand and a cigarette in his. We sat on the ground beside Afghans, Iranians, and hordes of pigeons, while Raja spoke of the pressures he experienced as a young man in Greece. Like many men who have migrated from their home countries, Raja felt culturally compelled to send remittances and provide for his family, an obligation he described as uniquely masculine:

It’s all about the stress of being a man, a Pakistani man. Anyone Pakistani you can speak with him, ‘do you support your family?,’ he will most likely say yes … When we are little children, like 12 years or 13 years, my Mom or my Dad every time speak with me, ‘you are everything for us.’ And this time I feel better.

Did they say that to your sisters too, or … ?

Just me.

So it is about being a man then?

Yeah. And when I’m child I feel really good, like I am for them, it’s my job. But now I understand it’s really hard.

It doesn’t feel good anymore.

No.

I have to work because Pakistan culture is so different, really different. When my sister get married, I have to support because she also not working. [In] Pakistan only boys working, not girls working. Sisters when they get married I give them money. It’s not normal really, I have only 24 years. I want to enjoy my life but I can’t enjoy. This is not enjoying. Sometimes I drink, sometimes I go out with friends, but in here [points to head] I am so dispirited.

I’m just thinking if they [‘Skype’] pick up, they can can give us this fucking card and we can get easily this work, just we need work, so we can support the family. And one day we can finish the family responsibility, we finish soonly if we get soonly work, we can finish soonly and then we can think about us. But how if for five years you don’t have work, if for ten years you don’t have work, how you finish your responsibilities?

I want to own myself.

You want to own yourself?

Yeah.

And right now do you feel like you own yourself?

I feel I am helping me own myself. I never said to you ‘I need this,’ I never said to other people ‘I need this,’ I just found work. Sometimes I find work, sometimes not, but I’m ok. Slowly slowly I made myself. And I know one day I’ll make myself a better thing, but slowly, very slowly, just like a turtle. You know turtles run very slowly? I’m running like that.

One evening in November, I joined Raja at his apartment for dinner. I sat with a handful of his friends, and over cold whisky and a chicken biryani so spicy it made me sweat, we discussed their shared plans to focus on making enough money to leave Greece.Footnote4 Raja told me that he had officially decided to stop calling on Skype and was going to fully commit himself to finding informal work:

I will stop [calling on Skype]. I stopped before, just two or three times I will call with you in your office this time [referring to an upcoming session we had arranged]. Another time I am going to stop.

How come?

Because I’ll be leaving this country. I can pay 650 euro, I pay already one person, and 450 euro I have to pay more then he will give me some papers illegally and then I can go … What can I do? I’m calling one and a half year and no response. What you do, what you feel? You think ‘oh I am stupid.’ This is all, you think ‘I am stupid,’ and I feel I am stupid.

I felt many times I want to kill myself. Just my son stop me from that. This is why I want to go home. I think ‘how is he going to survive?’ He hasn’t seen me since he was a kid. Now if I die also, he’ll never see his daddy and he’s going to fail, so I want to go home.

It doesn’t feel responsible [to keep calling on Skype]. I feel like [a] father, I have to go home to protect my kid. What else can I do, stay here living like what? … Same way I’m living here is [the] same way I’m going there. If I end with only my kiss, it’s what I have. So I’ll start from there.

So you’ll start from being a father.

Yeah, I’ll go just like that. My son goes to school, I go to bring him. Let him concentrate on football, I’ll go there to support him. Maybe he’ll be lucky to have contract, but I have to go there and support him, not to watch him. If he cannot be around me, I have to be there. This is reality of life.

Every week I received messages from individuals saying that they had left both the Skype system and Athens: they were in Argos harvesting olives, in Manolada picking strawberries, or on the islands working in kitchens. Sometimes these announcements involved explicit rejections of the Skype system, as with Milad from Iran, who said he was going to stop calling and would instead find work to afford a fake passport and fly to Northern Europe, since ‘I cannot depend on Skype.’ Other times they involved more implicit rejections in the form of de-prioritization, as with the countless men who told me simply did not have time to call on Skype because they wanted to work.Footnote5

In both cases, individuals outlined willing choices to focus on sustaining themselves as opposed to relying on an unreliable system. Whether or not these choices were always articulated in masculine grammars, they highlight agentic choices that safeguarded masculinity in the face of an emasculating technology of digital bordering. The Skype system was one of erasure; it made men invisible to the state, and their masculinities invisible to themselves. Refusal allowed existential pursuits of meaning making and self-recognition, with investment in new configurations of masculinity and mobility.

Contradictions

My analysis has thus far explored how refusals can generate emancipatory possibilities. However, there is risk of romanticizing what in reality is a messy and uncertain act, distracting from the ways in which the refusals I observed produced freedoms while also sustaining unfreedoms. In Greece, the insertion of Skype into the quotidian lives of migrants and asylum seekers came not from their own digital communication preferences but rather from deliberate choices of governance that made Skype central to the migration landscape. In other words, asylum seekers did not choose to use Skype to access the asylum procedure, the Greek state mandated that asylum seekers use Skype to access the asylum procedure.

Constrained by length, this article cannot unravel the politics of the Skype system and the logics implicated in its design and usage, but it is crucial to recognize the system’s dominating nature and deterrent effects. By directing physical queues to a largely non-responsive digital system, the Greek Asylum Service avoided responsibility, fatigued applicants, and distanced the state from those seeking to make claims upon it, all while displacing culpability for unanswered calls onto asylum seekers themselves (‘they must insist!’ Asylum Service staffers often told me).

When people refused to ‘insist,’ they removed themselves from a form of digitally mediated state violence, but it is reductive to suggest that refusal benefitted only those who refused; the refused also benefited. Refusals to keep calling on Skype allowed the state to exert further control over migrants and asylum seekers by sustaining ties to ‘illegality’ and exploitation, while advancing restrictive migration aims. Refusal generated purpose and control, enabling individuals to exit the Skype system in favor of finding employment, but this very refusal also generated an exploitable labor force. And though some individuals stopped calling and found other avenues through which to make claims on the state (ie. fake documents), many others simply removed themselves entirely from the asylum system, like Nabiullah, an Afghan asylum seeker who, although he was eligible to lodge a subsequent application on Skype after two rejections, said: ‘No I will not apply again, I will be illegal here like other people.’ It was common to hear such a sentiment, especially from individuals who had little money and could not afford the costs associated with onward migration.

Restrictive documentation regimes strategically irregularize workforces and deepen the precarity of laborers, with non-documentation implicated in a system of global labor subordination and phenomenological disciplining (De Genova, Citation2002). In Greece, a similar dynamic emerged, as refusal to keep calling on Skype strengthened ties to illegality, detainability, and deportability. This forced people to minimize public movements, and fed an irregular labor force which, in the context of capitalist structures and their relation to legal statuses of belonging and non-belonging, could be maintained as cheap and docile. For example, Junior works for a recycling company where he is paid by an agent who arranges part-time work for undocumented laborers. The work is physical and dirty, as described by Junior, and for eight hours of work, Junior earns 20 euros (2.5 euros per hour). Prince Meddo, who complained often about his inability to demand better conditions, works for a food preparation company in one of the most expensive suburbs of Athens. He works 12–14 hour days that start at 7:00am, earning just 1.25 euros per hour.

Scholarship finds that the economic precarity and social abjection experienced by asylum seeking men may compel them to engage in behavior they otherwise would have avoided, behavior that challenges their senses of morality, masculinity, and self (Griffiths, Citation2015; Vecchio & Gerard, Citation2018). It was common for the men I worked with to say that they didn’t want to engage in illicit or criminal behavior, but worried they’d have to as a means of survival. As Prince Meddo said:

I see some other people doing drugs, doing, I don’t know, stealing, a lot of things. Sometimes I thought about that … I say ‘I don’t have a choice, let me work, I don’t want to go and do bad things just to survive,’ but sometimes I think about it and say ‘maybe I should do it.’

For some, staying away from illicit activity was key to maintaining an ideal masculine self. Junior told me that while every young man should find ways to support themselves, ‘the most important thing is legal, you know, [that] it’s not against the law of the country.’ The individuals I worked with wanted to be respectable men engaged in honest pursuits, much like the men in Ingvars & Gíslason’s, Citation2018 study of male refugees in Athens who wanted to have a ‘clean mind.’ However, illegality and precarity sometimes place aspirational standards of self in conflict with the constrained performances of self that reality demands. An in-depth analysis of survival strategies and their impact on self-concept falls outside the scope of this article, but it is worth noting that refusals can structure subjective experience in ways that can both fortify and erode migrant masculinity. Refusal can safeguard masculinity, but it can also cement men into systems that weaken individual ability to successfully enact projects of desired self. In exiting the Skype system, applicants attempted to regain a sense of masculinity and dignity, but they held those gains alongside suffering they further entrenched. Refusal is not a wholly emancipatory act: it binds as it frees.

Conclusion

This article contributes to refugee studies, critical studies of men and masculinities, and studies of digital bordering, introducing deeper understanding of the operationalizing of novel digital bordering techniques. More specifically, it adds understanding of how those borders – experienced as personal assaults ranging from racial othering to cultural castration – are internalized and contested. Research on the politics of refusal presents exit and abstention as generative of new possibilities and ways of being, and this article has argued that theorization on the politics of refusal can be fruitfully extended to the study of migrant masculinities, highlighting how acts of abstention generate fertile ground for negotiating desired standards of masculinity.

In restricting access to legality, livelihoods, successful remittance, mobility, and other hegemonic notions of masculinity, the Skype system erected not only internal borders within Greece, but internal borders within the (masculine) self; the Skype system poisoned masculine self-relation. By ‘deleting the Skype,’ individuals (re)negotiated masculine status, transitioning their waiting state and sense of self from emasculating dependency to perceived (or possible) control. They thus imagined new ways of being, and new ways of being men.

At the same time, the refusals produced contradictory effects. Refusal supported masculine attainment, but risked strangling it as well. Though refusal can be considered a site of masculine identity construction, that site may be a space of struggle, as global structures of capital accumulation and exploitation make standards of masculinity difficult to attain. Regardless, theorizing exit as refusal holds analytical purchase. The discussed refusals comprised trade-offs whereby men forfeited that which was desired (legal status) so as to (re)claim that which they deemed of higher value: self-respect, control, masculinity. Within this context, a politics of refusal reveals the ability to take ethical positions of measured concession, to give up the chance of something material in exchange for the immaterial value of masculine self-recognition. The observed refusals comprised low-level acts of political behavior cast as projects of personal reclamation and reinvention rather than political reimagination.

The intimacy of each refusal and the target of its action (the self rather than systems of oppression) suggest a different form of political action through which subjugated individuals can assert and articulate their humanity, recapturing aspects of self within a digital space marked by non-recognition and the structural production of negative subjectivities. The logics underpinning these refusals allow scholars of borders, technology, and masculinities to interrogate the ability of marginalized men to engage in self-preservation and self-creation in spite of digitized forces that dominate and emasculate. This encourages a broader study of borders and masculinities, one that shines light onto what it means for men to exercise agency under severe structural constraints without necessarily imagining new polities or configurations of power. Such an approach affords careful consideration of masculine agency in spaces of limbo and subordination, revealing how bordered men can shield themselves in small but meaningful ways from the erosion and erasure of digital bordering regimes.

Acknowledgements

With gratitude I recognize the support of the Rhodes Trust. I am also grateful to Jess Webster and Ale Cábez for their collaboration and friendship, and to Professor Reena Kukreja for her mentorship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stephen Damianos

Stephen Damianos completed his doctorate at the University of Oxford’s Refugee Studies Centre. He previously completed his MPhil in Development Studies at the University of Cambridge, and a BA in Political Science and Journalism at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on digital bordering, technology, and human rights.

Notes

1 This occurred while this article was under review, and as such, this paper does not explore the new online system.

2 The digital alienation shaped by the Skype system highlights a divergence from literature that explores how technology allows immobile migrants to maintain connection with social and familial networks through 'digital kin work' (Baldassar, Citation2022, p. 5; Eide, Citation2019). In this case, technology did not facilitate connectivity. It further entrenched isolation.

3 See Belloni Citation2020 for another example of people stepping away from digitalized communication systems

to protect masculinity. Note, however, that her focus is on withdrawal from emasculating communications that happen to be facilitated by technology, not withdrawal from an inherently emasculating technology.

4 The observed refusals were most clearly enacted through individual decision making; for example, it was common for individuals to exit the Skype system while their friends continued calling, and vice versa. Yet I also observed groups of friends leave the system together, or at the suggestion of others. Future research would benefit from exploring the extent to which refusal results from group strategizing, shared aspirations, and collective decision making, particularly with regard to masculine sociality.

5 Refusal can also be read in temporal terms. States exert power through forced waiting and temporal control (Bhatia & Canning, Citation2021; Biner & Biner, Citation2021; Hage, Citation2009), which is exemplified by the Skype system’s power to make people wait indefinitely, adhere to a specific temporal architecture, and remain temporally dependent on something that might not even occur. When people decide to prioritize other temporal obligations, or to reject the system altogether, their refusals constitute a partial withdrawal from the politics of waiting.

References

- Affleck, W., Thamotharampillai, U., Jeyakumar, J., & Whitley, R. (2018). “If one does not fulfil his duties, he must not be a man”: Masculinity, mental health and resilience amongst Sri Lankan Tamil refugee Men in Canada. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 42(4), 840–861.

- Allan, J. A. (2018). Masculinity as cruel optimism. Norma, 13(3-4), 175–190.

- Aradau, C. (2022). Experimentality, surplus data and the politics of debilitation in borderzones. Geopolitics, 27(1), 26–46.

- Artero, M., & Fontanari, E. (2021). Obstructing lives: local borders and their structural violence in the asylum field of post-2015 Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(3), 631–648.

- Baldassar, L. (2022). Migrant visits over time: Ethnographic returning and the technological turn. Global Networks.

- Belloni, M. (2020). When the phone stops ringing: On the meanings and causes of disruptions in communication between Eritrean refugees and their families back home. Global Networks, 20(2), 256–273.

- Bhatia, M., & Canning, V.2021). Stealing time: Migration, temporalities and state violence. Springer Nature.

- Bhungalia, L. (2020). Laughing at power: Humor, transgression, and the politics of refusal in Palestine. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38(3), 387–404.

- Biner, ZÖ, & Biner, Ö. (2021). Introduction: On the politics of waiting. Social Anthropology, 29(3), 787–799.

- Boccagni, P. (2017). Aspirations and the subjective future of migration: Comparing views and desires of the “time ahead” through the narratives of immigrant domestic workers. Comparative Migration Studies, 5(1), 1–18.

- Cabot, H. (2014). On the doorstep of Europe: Asylum and citizenship in Greece. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- De Genova, N. (2002). Migrant “illegality” and deportability in everyday life. Annual Review of Anthropology, 419–447.

- Eide, E. (2019). The cell phone as a co-traveller: Refugees and the multi-functions of cell phones. Inclusive consumption: Immigrants’ access to and use of public and private goods and services. Oslo: Oslo Universitetsforlaget.

- Griffiths, M. (2015). “Here, Man Is nothing!”. Men and Masculinities, 18(4), 468–488.

- Hage, G. (2009). Waiting out the crisis: On stuckedness and governmentality. Anthropological Theory, 5(1), 463–475.

- Ingvars, ÁK, & Gíslason, I. V. (2018). Moral mobility. Men and Masculinities, 21(3), 383–402.

- Jaji, R. (2009). Masculinity on unstable ground: Young refugee men in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Refugee Studies, 22(2), 177–194.

- Kilkey, M., Plomien, A., & Perrons, D. (2014). Migrant men's fathering narratives, practices and projects in national and transnational spaces: Recent Polish male migrants to London. International Migration, 52(1), 178–191.

- Kukreja, R. (2021). Migration has stripped US of our manhood: Contradictions of failed masculinity among South Asian male migrants in Greece. Men and Masculinities, 24(2), 307–325.

- Latonero, M., & Kift, P. (2018). On digital passages and borders: Refugees and the new infrastructure for movement and control. Social Media+ Society, 4(1), 2056305118764432.

- Marin, L. (2011). Is Europe turning into a ‘technological fortress’? Innovation and technology for the management of EU’s external borders: Reflections on FRONTEX and EUROSUR. In Regulating technological innovation (pp. 131–151). London.: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McGranahan, C. (2016). Refusal and the gift of citizenship. Cultural Anthropology, 31(3), 334–341.

- Nedelcu, M., & Soysüren, I. (2022). Precarious migrants, migration regimes and digital technologies: the empowerment-control nexus. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(8), 1821–1837.

- Newhouse, L. S. (2021). On not seeking asylum: Migrant masculinities and the politics of refusal. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 120, 176–185.

- Parmar, A. (2019). Policing migration and racial technologies. The British Journal of Criminology, 59(4), 938–957.

- Parmar, A. (2020). Borders as mirrors: Racial hierarchies and policing migration. Critical Criminology, 28(2), 175–192.

- Prasse-Freeman, E. (2022). Resistance/refusal: Politics of manoeuvre under diffuse regimes of governmentality. Anthropological Theory, 22(1), 102–127.

- Prothmann, S. (2018). Migration, masculinity and social class: Insights from Pikine, Senegal. International Migration, 56(4), 96–108.

- Pustułka, P., Struzik, J., & Ślusarczyk, M. (2015). Caught between breadwinning and emotional provisions - the case of Polish migrant fathers in Norway. Studia Humanistyczne AGH, 14(2).

- Scheel, S. (2019). Autonomy of migration?: Appropriating mobility within biometric border regimes. Routledge.

- Shield, A. D. (2019). Immigrants on Grindr: Race, sexuality and belonging online. Springer Nature.

- Simpson, A. (2014). Mohawk interruptus: Political life across the borders of settler states. Duke University Press.

- Sobo, E. J. (2016). Theorizing (vaccine) refusal: through the looking glass. Cultural Anthropology, 31(3), 342–350.

- Tazzioli, M. (2019). Refugees’ debit cards, subjectivities, and data circuits: Financial-humanitarianism in the Greek migration laboratory. International Political Sociology, 13(4), 392–408.

- Tuckett, A. (2020). Rules, paper, status: Migrants and precarious bureaucracy in contemporary Italy. Stanford University Press.

- Van Houtum, H. (2021). Beyond ‘borderism’: Overcoming discriminative B/ordering and othering. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 112(1), 34–43.

- Vecchio, F., & Gerard, A.2018). Entrapping asylum seekers: Social, legal and economic precariousness. Springer.