Abstract

Human rights-based approaches to development (HRBADs) seem to be grounded in assumptions of change that remain implicit and therefore often undebated. These assumptions of change play at two levels, i.e. that of organisational change and that of social change. The main emphasis of this article is on organisational change as the logical precursor to social change. Explanatory factors for the challenges in introducing HRBADs in development organizations include the different legitimizing anchors that both use (normative versus empirical), as well as the differences in disciplinary backgrounds of staff and in role definition (confrontation versus collaboration with the state). An important finding is that result-based management and HRBADs may be more difficult to reconcile than often believed. The tension between both may be illustrative of the fundamental differences that continue to characterize development and human rights approaches, notwithstanding the rapprochement that has taken place over the past decade(s). We argue that more empirical work is needed in order to better understand organisational and social change through HRBADs.

The relationship between human rights and development has been framed in multiple ways.Footnote1 From a legal perspective, there are three major conceptualisations: the right to development; transnational human rights obligations; and human rights-based approaches to development (HRBADs). The former two represent a rather fundamental overhaul of human rights thinking, as they introduce new substantive rights and corresponding obligations and, even more importantly, new duty-bearers.Footnote2 HRBADs may be said to be more pragmatic and less ambitious, in that they do not envisage fundamental changes to the human rights framework. They are much more practice-orientated, i.e. they seek to introduce human rights principles into development thinking and practice.Footnote3 This more practical orientation does not make HRBAs easier or more simple though. In particular, their interplay with change is complex and under-researched.

HRBADs seem to be grounded in assumptions of change that remain implicit and therefore often undebated. These assumptions of change play at two levels. First of all, it is often assumed that the formal adoption of an HRBAD by an organisation implies that that organisation really applies an HRBAD. What seems to be ignored is that the introduction of any new policy requires organisational change which often provokes considerable internal resistance or is met with lethargy and bureaucratic attitude. This challenge applies all the more to the introduction of an HRBAD which can be considered a rather legal or even legalistic approach to fundamental social or economic questions despite its focus on principles. Secondly, whether and how social change takes place depends on a complex interplay of actors, institutions and policies. A straightforward causal relationship between an HRBAD and the envisaged social change is often presumed, however, in particular within result-based paradigms. Whereas organisational and social change are to be distinguished analytically, in practice they are often intrinsically linked. For a start, it is unlikely that the envisaged social change will occur if the organisation fails to adopt and implement its HRBAD policy properly in the first place.Footnote4 Secondly, the way an organisation thinks about effecting social change as part of the adoption of an HRBAD will inevitably impact on whether and how it achieves social change.

In what follows, we shall first succinctly introduce HRBADs and the role of law and legal institutions therein. We shall then look into the transformative potential of (human rights) law in society. Although much more empirical research is needed before anything meaningful can be said about the contribution of HRBADs to social change, we do not completely omit this point given its intrinsic link with organisational change in practice. However, logically, purposive social change may only be effected by an HRBAD to the extent that an organisation has really managed to introduce such an approach more or less successfully. The main emphasis of this article is therefore on organisational change as the logical precursor to social change. In section 3, we shall draw out what it took in particular for an international organisation like UNICEF to introduce an HRBAD, based on empirical case studies that have been conducted by others. By way of contextualisation, we include an exploratory investigation into the introduction of an HRBAD by the United Nations at the country level, by states (Norway and Sweden) and by non-governmental organisations (ActionAid) from the perspective of organisational change.

The nature and scope of the exercise is obviously limited due to the fact that we could only draw on existing empirical work (rather than undertake empirical work ourselves), but that methodological limitation does not pose a fundamental obstacle at this stage, where the main purpose is that of drawing more attention to the change perspective in understanding the limited headway HRBADs have made so far. To the extent that the available empirical data allow for it, we shall use a similar analytical matrix. In particular, we shall pay attention to internal reflection and planning, and leadership and true believersFootnote5 as explanatory entry points for organisational change following the introduction of an HRBAD.Footnote6 In addition to these drivers of change, we shall look into frequently mentioned spoilers of change, such as lack of capacity and staff turnover. At the interplay of organisational and societal change is the tension between result-based management and HRBADs.

By drawing attention to the (often naïve or simply wrong) assumptions of organisational and social change in HRBADs, we do not seek to dismiss them. Rather, this exercise seeks to gain a better understanding of when and why an HRBAD works. After two decades of mainly promotional literature on HRBADs stressing their added value,Footnote7 the time may have come to strengthen the knowledge base on HRBADs and to address the hard questions more explicitly.Footnote8 This piece is a modest attempt to contribute to that research agenda setting exercise. Further detailed empirical research will be needed to corroborate or dismiss the hypotheses that we advance here.

I. HRBADs and the Role of Law and Legal Institutions

There is no single or universal definition or practice of HRBAD, hence the word is used in the plural. Nevertheless, some common characteristics of HRBADs can be identified. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) correctly emphasises that HRBADs are both about process and outcomes: whereas HRBADs are operationally directed to promote and protect human rights as envisaged outcomes, their normative grounding in human rights standards also draws attention to the process through which the outcomes are achieved.Footnote9 So, HRBADs claim to change the way development work is done (process), and also put forward full human rights realisation as the goal of development work (outcomes). In both respects, change is a central notion: a change is proposed as to how development is carried out (which has inevitable implications on organisations involved in development work), and the objective of full human rights realisation will require fundamental social change.

The grounding in human rights means first and foremost that HRBADs often draw on the legal codification of human rights norms and standards in United Nations and regional treaties, as well as in municipal law, and on the work of human rights monitoring bodies and courts. A degree of commonality may be found in the fact that HRBADS share some human rights principles, which may be aptly summarised by the acronym PANEL: participation, accountability, non-discrimination, empowerment and linkage to human rights norms. The last of these (i.e., linkage to human rights norms) has been labelled “normativity” in a recent report, so an alternative acronym is PANEN.Footnote10 Whereas these principles are not necessarily new to development, nor exclusively legal principles, they do have a specific human rights and even legal meaning (except for empowerment which has no legal equivalent). Moreover, the linkage to human rights norms or normativity intrinsically has a strong legal component, although it is not necessarily reducible to (human rights) law. The legal preponderance in HRBADs is borne out by the fact that staff with a legal background “tend to quickly grasp the implications of a rights-based approach”.Footnote11 The reference to human rights norms almost inevitably brings human rights monitoring bodies into the picture, be it at universal, regional or national level. At the universal level, expert bodies (called committees) monitor the implementation of the core United Nations human rights treaties through reporting (and sometimes also complaints and inquiry) procedures. At the regional level, a judicial monitoring regime is in place for the Americas, Africa and Europe. Domestically, human rights monitoring is typically undertaken by human rights institutions and courts.

Certainly, HRBADs are not the monopoly of the legal discipline, but law and the legal discipline can hardly be ignored or completely side-lined, which brings us to the question of what the transformative potential of human rights law is, and what can be learned more generally from social change theories. So far, these questions have seldom been explicitly addressed in HRBAD literature, notwithstanding their central importance to a good understanding of when and how HRBADs may work.Footnote12 Although this article focuses on the logical precursor to effecting social change, i.e. organisational change, the intrinsic links in practice between both make it necessary to touch upon social change for a short while. Moreover, the views held on effecting social change may have a bearing on or intersect with the way organisational change is broached.

II. The Transformative Potential of Human Rights and Social Change Theories

Gready and Ensor had already pointed out in 2005 that “[h]ow structural change might be achieved requires much greater clarification, both conceptually and practically”. As a minimum, underlying implicit assumptions of change need to be rendered explicit. Ideally, a theory rather than assumptions of change underpin HRBADs. Such a theory should be grounded as much as possible in empirical evidence, spelling out how it conceptualises change (causation, influences, directions of change) and which actors and institutions it deems instrumental in bringing about social change, and clarifying how power is understood.Footnote13

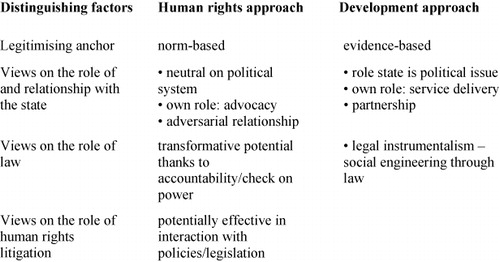

Elsewhere, Gready with Vandenhole have clarified the archetypical similarities and differences between human rights and development theories and practice through the prism of what they call five “key entry point[s] to change: 1) the state; 2) the law; 3) transnational and international collaboration; 4) localism and bottom-up approaches; and 5) multiple and complex methods”.Footnote14 In what follows, we mainly summarise the findings on the state and the law.

In development, the role of the state (should it be an interventionist, managerial, or “small” state) is seen as a pre-eminently political question. In human rights, formally, a politically neutral stance on the role of the state is often taken,Footnote15 although the tripartite typology of state obligations (respect, protect, fulfil) clearly reveals that the state is to respect human rights (which excludes authoritarianism) and is expected to take positive action (which excludes a minimalist, non-interventionist state). For international organisations like UNICEF, the adoption of an HRBA has meant that it moved beyond service delivery to also “shifting great responsibility on to governments”,Footnote16 which seems to confirm that human rights require more than a minimalist state. As to the relationship of the state with human rights actors and development actors, a reverse tendency is noticeable; human rights actors have or are perceived to have a mainly adversarial relationship with the state as they seek to expose violations, whereas development actors tend to be seen more as partners of the state.Footnote17 This ties in with a third aspect, how actors define their own role (service delivery, capacity-building, advocacy), and what impact that role definition has, in particular on relationships with the state (cooperation versus confrontation).Footnote18 Later in this article, we shall add some nuance to this binary thinking in terms of confrontation versus cooperation, by making an analytical distinction between political work and confrontation.

The role of law is often entirely ignored in development. Whenever development actors following the adoption of an HRBAD do pay some attention to legal reform and litigation, it represents a major shift in their work.Footnote19 There are two basic positions on the role of law in change: those who argue that the law follows change, and those who believe that law may lead change. In the latter category, there is a strong tendency towards legal instrumentalism and social engineering through law. An inherent risk of approaching the law as a mere instrument for social change is the instrumentalisation of law by political power. There is also little empirical evidence that law “works”, that is to say that it brings about the intended effects.Footnote20 Using the law in development thus raises questions of instrumentalisation and effectiveness.

Emphasis on the inherent normativity of law, as reflected for example in human rights law, may shield the law to some extent from outright political instrumentalisation, but exposes it to more radical critique on the inherently ideological (i.e. liberal) nature of the law. The liberal nature of the law is reflected in the understanding of empowerment as putting citizens in a position to “make political demands that lead to better service provision and to the sort of situation where citizens can provide services for themselves”.Footnote21 Nonetheless, human rights law is generally believed to have transformative potential because of its check on power and its focus on accountability. Likewise, human rights litigation has been assigned transformative potential under certain preconditions and in close interaction with policy and legislation.Footnote22

Another entry point to change is the role of participation and empowerment in bottom-up and localised approaches.Footnote23 Of key importance in these approaches is the way in which human rights are primarily seen as a struggle rather than as pre-conceived legal rules, which makes it clear that human rights are not the privileged nor the exclusive domain of the law. Whereas this does not exclude the use of human rights legal tools and norms, it does introduce a different starting point (local struggles, not international norms), a different prioritisation (processes rather than outcomes) and a different end-goal (change in power relations rather than the implementation of international standards).Footnote24 In turn, these differences cast a light on the fundamentally opposite ways in which external actors can attempt to bring about social change, i.e. by drawing on pre-conceived norms or on local struggles.

A fundamental difference between human rights and development actors and their approach to change is that they use different “legitimizing anchors”Footnote25 : whereas human rights actors tend to use (legal) norms as their legitimising anchor, development actors seek it more in empirical observations. In other words, human rights approaches tend to be norm-based whereas development approaches take an evidence-based approach.Footnote26 summarises these differences.

In social change theories, causal chain theories are arguably under the greatest doubt. This may explain the tension between a result-based approach, as is now central to much development cooperation work on the one hand, and a complex approach to (social) change on the other.Footnote27 No linear cause and effect relationship can be assumed in bringing about change, given the complex nature of change in particular in the field of human rights. There are no really quick fixes, results may be difficult to quantify and it may be even more difficult to claim credit for outcomes.Footnote28 Result-based management (RBM), which seems to assume a direct causal chain between interventions and results, may paradoxically be a spoiler rather than a driver or facilitator of change.Footnote29 A more careful account was put forward in a 2012 report on UNICEF's HRBAD, in which it was argued that HRBADs and RBM are compatible, but that “there are obstacles to their being applied concurrently”. The main reason for these obstacles was reported to be that the perceived drive for results in RBM impeded the application of HRBAD.Footnote30 One such impediment may be that the “emphasis on producing quick results [leads] to advocacy activities being disadvantaged”.Footnote31 A more fundamental tension is that the

human rights tradition finds itself in full-blown contradiction to the classical planning and programming tradition. The human rights-based approach to development denies that any prioritization of rights is possible … But if there can be no hierarchy of rights, can a human rights-based organization choose its strategic priorities? The question became acute as UNICEF professed to be a rights-based organization while at the same time embracing “results-based management”, the latest version of the classical planning and programming tradition.Footnote32

III. HRBADs and Organisational Change

Logically preceding a solid understanding of the complexity of social change is the need to better understand what it takes for an organisation to introduce an HRBAD with a view to bring about social change successfully in the first place. Both in change theory and organisations theory, it has been emphasised that views on change and on how organisations change are very often based on implicit assumptions. Both sets of theories also point out the complexity of (organisational) change, and the existence of many different and often competing approaches or “schools”, with some emphasising structural constraints (i.e. constraints based on durable social structures) and others individual agency. Both dimensions are important and often operate in tandem.Footnote33 Moreover, a distinction is to be made between formal structure and actual day-to-day activities, for the assumption that organisations function according to formal blueprints is not supported by empirical research,Footnote34 hence the emphasis again on the need for much more empirical work. In the case example of UNICEF that follows, we look in particular into internal reflection and planning, and leadership and true believers as explanatory entry points for the (lack of) organisational change accompanying the introduction of an HRBAD. In addition to these drivers of change, we shall pay attention to the spoilers of change, such as lack of capacity or staff turnover, and to the tension between HRBAD and RBM. Attempts at introducing HRBAD by the UN at the country level by states and by non-governmental organisations seem to show similar trends at first sight, though much more research is needed before firm conclusions can be reached.

III.1 UNICEF: Between adaptation and transformation

UNICEF's experience with HRBAD is considered as one of the more successful examples, and has been well documented over a longer period of time. UNICEF has evolved from a technical organisation with a focus on service provision to one that uses children's rights as codified in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in all its programming. A congruence of external and internal forces, including NGO and executive board pressure, changed UNICEF's policy towards the CRC.Footnote35 True believers and the executive director of the organisation took it further, and the “CRC became a key strategic priority”.Footnote36 Oestreich has concluded that a group of “true believers” and even more strong leadership are the variables with the highest explanatory power.Footnote37 Central to the change in attitude towards the CRC was the perception that human rights language would not place UNICEF in “confrontational, political situations vis-à-vis states parties”, but rather add legitimacy to UNICEF's work.Footnote38 This reflects a more nuanced take on the more general tension in role definition in human rights versus development work that we flagged in the previous section: the former is understood by traditional development organisations to be political and confrontational, whereas the latter is claimed to be neutral and pragmatic.

Staff remain wary of promoting new policies, or changing existing ones, in ways that appear to violate the sovereignty of states or that risk so angering states that they will curtail cooperation with UNICEF. There remains a sense of there being a fine line between those CRC aspects that will actually help UNICEF pursue its goals and those that will ultimately undermine its ability to work cooperatively with states.Footnote39

The organization, in fact, has shown considerable latitude in choosing which elements of the CRC it wishes to pursue and which it deems to fall outside its mandate. They all receive rhetorical support, but only those deemed to be both central to UNICEF and politically viable are actually incorporated into program planning.Footnote40

The 2007–2011 period has been assessed in the Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming of March 2012. This external evaluation zoomed in on the country level, examining the situation in 38 Country Offices. Spoilers of organisational change were identified: implementation staff's overall limited understanding of HRBAD;Footnote56 conceptual confusion between the focus on equityFootnote57 and HRBAD;Footnote58 the location of the focal point for gender and human rights within the Division for Policy and Practice (rather than in the Programme Division), which created some distance between policy and programming; insufficient practical guidance on the approach for sector-specific application; human resources-management practices that neither emphasised nor supported competency in HRBAD; minimal and informal accountability for HRBAD; lack of attention paid to effective implementation of HRBAD in staff performance reviews; lack of support from management; and lack of systematic reporting on HRBAD implementation.Footnote59

As to the degree of application of human rights principles, the findings were mixed, with good results on normativity, mixed application with regard to participation and accountability, and satisfactory to weak on non-discrimination and transparency. Although the degree of application of human rights principles is not entirely in the hands of the organisation, it is to a large extent determined by factors internal to the organisation.Footnote60 In a more temporal perspective, i.e. through the lens of the programming cycle stages, HRBAD application was found to be strongest in the preparation phase and weakest in the monitoring and evaluation phase.Footnote61 The strong performance on normativity and weaker on other human rights principles may be open to different interpretations. One is to consider UNICEF successful in integrating human rights language but, in fact, it mainly just pays lip service to it. Of course, integrating explicit language on human rights may be the easiest part of introducing an HRBAD.

In sum, whereas the introduction of HRBAD by UNICEF may have led to adaptation, it has not transformed the organisation. Key drivers of change have been leadership and true believers in combination with internal reflection. Obstacles and spoilers of change have been identified in considerable detail. Different disciplinary backgrounds and diverging views on role definition, competing agendas, lack of capacity and learning processes, and deficiencies in the accountability and incentive structure stand out. The tension between RBM and an HRBAD became particularly acute in the discussion on whether or not prioritisation of certain rights is permissible, but also in the short-term focus of RBM versus the long-term project of realising human rights.Footnote62

III.2 Comparative perspectives

In what follows, we briefly explore whether some of the trends that we have identified with UNICEF can also be traced with other actors that have introduced HRBADs. Again drawing on available empirical work, we shall look at the United Nations Development Group (UNDG), Norwegian and Swedish development cooperation and ActionAid. It goes without saying that drawing parallels between actors that are so different in law and practice should be done with utmost care. One may wonder, for example, whether it is not much easier for an international organisation like UNICEF to fully embrace the normativity of an HRBAD by explicitly incorporating the CRC in its work, given the potential for UNICEF to really identify itself with children's rights. For international organisations like the United Nations Development Programme or for states or non-governmental organisations, it may be less obvious to self-identify with a particular treaty or human rights of a particular group. This may in turn make organisational buy-in more challenging.

III.3 UNDG at the country level

Vandenhole has studied organisational change following the introduction of HRBADs within UNDG at the country level. Since 1997, UNDG has been the vehicle for coordination and alignment of UN development activities.Footnote63 Empirical evaluations of HRBADs at the level of United Nations Country Teams (UNCTs), on which this assessment draws, again tend to emphasise actor-centred criteria rather than structures in explaining (lack of) organisational change.

UNCTs have several instruments at their disposal. The Common Country Assessment (CCA) is the main analytical tool, though no longer mandatory. The United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) is a programming tool, i.e. the UN common response to a country's situation and priorities. For present purposes, the question is whether and how the integration of an HRBAD in CCA/UNDAF has led to organisational change. Four main issues have been identified as drivers or spoilers of organisational change within UNCTs: leadership; capacity; accountability and role definition.Footnote64 Leadership and clear direction by the Resident Coordinator have been identified as the single most important factor.Footnote65 A second element is mutual accountability among UNCT members (who represent one of the UN programmes, funds or agencies) regarding their responsibilities for applying a HRBA.Footnote66 Capacity-building within the UNCT has equally been flagged as an important factor of failure or success.Footnote67 Capacity-building requires the involvement of specialised human rights staff,Footnote68 as well as concrete methodologies of participation and monitoring, and information packages for use in everyday work.Footnote69 Capacity extends beyond a basic understanding of HRBA, to include “the advocacy and negotiating skills to raise “unpleasant news” in a constructive way that leads to change, and does not cut off dialogue”.Footnote70 Dialogue (i.e. persuasion or socialisation), rather than naming and shaming (confrontation), takes centre-stage in the role definition. For example, the Resident Coordinator is understood to have no role to play in reporting and monitoring human rights violations.Footnote71 This role definition is in line with the traditional division of labour between human rights organisations and development organisations, whereby the former are said to have a more adversarial role with governments, and the latter usually work in partnership with governments. Whether this is a driver or a spoiler of changes is a matter of debate. Some have argued that for HRBAD to be successful, UNCTs need to be willing to assume a more confrontational role.Footnote72 Others suggest that there is a natural division of labour between the human rights bodies of the UN, including the OHCHR, who have an advocacy role, and the UNCT as a problem-solver.Footnote73

At the UN agency level, lack of support and high staff turnover have been identified as two major obstacles for change.Footnote74 The spoilers within the UN system as a whole relate more to internal and institutional elements, such as the short time-frame used and the lack of ability to support risk-taking.Footnote75

All in all, the degree of organisational change brought about by the introduction of HRBAD into UN development analysis and programming within UNCTs has remained limited. Role definition is a key explanatory factor. The role definition of UNDGs and RCs has been very much in line with the development approach, i.e. partnership with governments, which in turn has reinforced rather than challenged the disconnect of the UN development players with the work of the UN human rights actors, as exemplified in the promotion-protection dichotomy at the organisational level. Key to challenging that promotion-protection dichotomy is the realisation that operational theories of change in the human rights field do not exclusively focus on naming and shaming; some place processes of persuasion or socialisation. Moreover, human rights treaty bodies typically do not adopt a confrontational approach in their monitoring of state parties’ performance, but engage in a constructive dialogue.Footnote76 The role definition reflects the way Resident Coordinators perceive of the relationship with the state, i.e. a partnership.

III.4 Donor states: Sweden and Norway

In 2011, a report was published that evaluates SIDA'sFootnote77 and NORAD'sFootnote78 aid policies in support of children's rights.Footnote79 Both development cooperation agencies have longstanding experience with children's rights-based approaches in their development cooperation. SIDA has opted for a combination of mainstreaming and child-targeted interventions; NORAD has privileged child-targeted interventions.

Whereas the report focuses mainly on outputs and outcomes, it also contains some interesting conclusions on organisational change required for the successful introduction and implementation of an HRBA. What is peculiar in this setting is that the specificity of a children's HRBA was taken into account by incorporating the four general principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (non-discrimination; best interests of the child; right to life, survival and development; and the right of the child to be heard) into the assessment.

The report flags the organisational challenges posed by the mainstreaming of children's rights as part of an HRBAD:

Mainstreaming is a very ambitious approach indeed. Its underlying rationale is that certain policy issues are of such paramount importance that they need to inform all undertakings. In principle, mainstreaming requires the entire organisation to be capable of implementing it, e.g. the requisite knowledge and practical skills to infuse every intervention with a child rights perspective. At that, the endeavour needs to be continuous to be effective, not a one-off exercise.Footnote80

Interestingly, the recommendations in the report draw on both the development and the human rights approach: they are based on empirical evidence gathered through four country studies, but also on “the normative imperatives of the Convention”.Footnote83 On the latter point, it is observed that, in particular, the participation of children needs to be better thought through and operationalised.Footnote84 In other words, the recommendations draw on the two legitimising anchors that were earlier identified: empirical evidence and human rights norms. The tension between results-based management and an HRBAD with an emphasis on advocacy was found also in SIDA's and NORAD's sponsored work on the ground.Footnote85

A fairly comprehensive study of HRBADs as adopted by donors flags broadly similar drivers and spoilers of organisational change to those we have identified in this and the previous section.Footnote86

III.5 Non-governmental organisations: ActionAid

A third actor that has introduced HRBADs are non-governmental organisations (NGOs). The introduction of an HRBAD by ActionAid has been well studied, and is therefore taken here by way of example.Footnote87

In their 2009 account, Chapman in collaboration with V Miller, A Campolina Soares and J Samuel focus mainly on social change and questions of power, but they also develop some ideas on organisational change. They argue that

development NGOs must shift, in their primary role, from being implementers and drivers of development to being allies with people's organizations and social movements in a collective struggle for change. Such a shift means a much more complex mix of roles involving sharing and negotiating power in new ways, challenging assumptions, and taking clear, often risky, political stands in favor of people marginalized by poverty and the privilege of others.Footnote88

Gready puts particular emphasis on the “organisational archaeologies and alignments” that characterise ActionAid: the organisation moved from a charity, through a participatory to a rights-based approach. These approaches did not replace each other; rather, they are layers that mutually influence each other.Footnote92 As the transition to a new approach remains incomplete, two challenges for organisational alignment arise: part of the work and of the staff commitment still lies with service delivery and community development work, and HRBAD has been only operationalised fully for local programming, not, for example, for fundraising.Footnote93 Whereas it may be tempting to label these challenges of misalignment “spoilers of change”, that could be deceptive, as they may in fact be necessary to trigger organisational change.Footnote94 The analysis in terms of a cycle of misalignment and realignment brings in a dynamic perspective on organisational change; it shows how organisational change is an on-going, dynamic process, not a one-off event. It also brings to the fore the question of what degree of organisational change is needed: is organisational adaptation sufficient or even desirable or do we need transformation? Other elements of organisational change that were flagged earlier, i.e. the need to provide concrete guidance for programming and for dealing with dilemmas, and for capacity-building of staff, tend to be confirmed.Footnote95 A distinctive element is the identification of the need for an overarching “identity narrative”,Footnote96 though UNICEF's ambiguity whether to use children's rights or equity discourse instead as its legitimising anchor may reflect a similar challenge.

As to role definition, it is argued that HRBADs, given their inherently political nature, demand the taking of sides, and so conflicts may have to be dealt with within alliances and with external actors.Footnote97 This is not to say that service delivery and HRBAD are on two different planets; for Chapman, it is more a matter of “integrating service delivery and rights-based aspects of … programs”.Footnote98 Nevertheless, Gready, in his analysis, confirms ActionAid's “more confrontational relationship with the state”.Footnote99

In sum, key to organisational change within ActionAid have been the cycles of internal reflection and planning, in response to misalignment challenges. Other elements that impact on organisational change, such as leadership, were channelled through these cycles.Footnote100 ActionAid's relationship with the state seems to have become more confrontational, possibly commensurate with the degree to which the organisation has started to push for fundamental social change. The tension between RBM and HRBAD is less evident.

IV. Starting Points for Reflection

The ambition of this article was not to present a grand theory of change about HRBADs, nor to offer an encyclopaedic mapping of studies on change in HRBADs, nor even to report on own empirical research. Instead, it seeks to trigger more explicit acknowledgement of the often implicit assumptions of change in HRBADs. We have mainly focused on organisational change, for two reasons in particular. First, the implementation of an HRBAD has often been only piecemeal, due to an underestimation of the implications for an organisation to properly introduce an HRBAD, so that it may be too early to study social change through HRBAD. Secondly, and closely related to the first reason, empirical evidence on the social impact of HRBADs remains fairly limited. Nonetheless, organisational and social change are closely intertwined in practice, as has been illustrated in particular with regard to the tension between RBM and HRBAD.

Somewhat paradoxically, when it comes to assessing results, result-based management (RBM) as a fashionable tool in development approaches seems to assume quite naïvely and without much empirical support a linear cause and effect relationship between interventions and outcomes. In the field of human rights, given the complex nature of (bringing about) social change, no such linear causal relationship can be assumed. Hence, RBM and HRBADs may be more difficult to reconcile than often believed, and that tension may be illustrative of the fundamental differences that continue to characterise development and human rights approaches, notwithstanding the rapprochement that has taken place over the past decade(s).

A fundamental difference between human rights and development actors and their approaches to change is that they use different “legitimising anchors”: whereas human rights actors tend to use legal norms as their legitimising anchor, development actors seek it more in empirical observations. In other words, human rights approaches are norm-based whereas development approaches take an evidence-based approach. This should not come as a surprise, since normativity is a key feature of HRBADs. But what if the norms are in tension with empirical findings? And how can we ensure that these norms themselves are grounded in struggles on the ground? These questions clearly open up a whole field of research questions that need to be addressed (anew) in light of HRBADs.

Human rights-based change may pose particular challenges to change agents, as compared with other attempts to bring about change, since convincing development staff with a technical training to accept a normative framework may be a challenging task. Human rights-based change thus poses specific challenges to leadership, capacity-building and role definition, in that it tends to be considered by development actors as imposed from the outside, and to deviate from what they consider to be good development practice (being value rather than evidence-based and having its legitimising anchor in norms rather than in ownership or effectiveness). At the same time, HRBADs should remain sufficiently open to engage with empirical findings, in particular the more exacting ones.

With regard to capacity-building, for example, this clash of disciplines means that far more than just legal or technical training on HRBADs, what is needed is staff that are capacitated to engage in interdisciplinary reflection and work.

As to role definition, more work needs to be done on the dichotomies that are currently used. Quite often, the development-human rights dichotomy is equated with the promotion-protection dichotomy, which is in turn equated with cooperation-confrontation and political-neutral dichotomies. However, experience with human rights work shows that political work, in the sense of raising and addressing issues of power and social change, does not automatically mean outright confrontation. This is illustrated in UNICEF's experience. Through the adoption of an HRBAD, the organisation got involved in political activities, but it has looked for cooperative channels and avoided conflict and confrontation.Footnote101 Whereas political work is undoubtedly more amenable to confrontation, it is not necessarily so, though that too may come at the price of not pressing too hard for social change.

An important lesson is that organisational change never implies a clean slate. Old and new approaches represent layers of “organisational archaeologies”. This may be a comforting message for staff who are rather reluctant to embrace a new approach, but it also indicates that the introduction of a new approach takes time and effort to really sink in. Success is not guaranteed: at best, the organisation may transform, in many instances adaptation may be the more likely scenario. More empirical work is therefore needed to assess which level of organisational change (adaptation, transformation) is needed and/or desirable for successfully introducing an HRBAD in an organisation, and for the HRBAD to be successful in achieving social change.

The language of drivers and spoilers of change, while forceful, may carry normative connotations on good and bad elements for change that, at a deeper level of analysis, turn out not be as unequivocal as suggested. So-called spoilers of change may be needed to push an organisation to a point where it is willing and able to change. The perspective of cycles of misalignment and realignment brings in a dynamic perspective on organisational change. It shows how organisational change is an on-going, dynamic process, not a one-off event, and how misalignment may be a necessary precondition to bring about change. How these cycles function once again requires careful empirical work.

Notes

1 SP Marks, “The Human Rights Framework for Development: Seven Approaches”, in Basu Mushumi, Archna Negi and Arjun K. Sengupta (eds), Reflections on the Right to Development (Sage Publications, 2005), 23–60; L-H Piron with T O'Neil, “Integrating Human Rights into Development. A synthesis of donor approaches and experiences” (2005), available at storage.globalcitizen.net/data/topic/knowledge/uploads/201209121610859063_%E6%96%B01%20Integrating%20Human%20Rights%20into%20 Development.pdf (accessed 22 April 2014); D D'Hollander, A Marx and J Wouters, “Integrating Human Rights in Development Policy: Mapping Donor Strategies and Practices”, Working Paper 108, June 2013, available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2286204 (accessed 18 April 2014), 9–42.

2 For more details, see W Vandenhole, “The Human Right to Development as a Paradox” (2003) Verfassung und Recht in Übersee. Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America 377–404; W Vandenhole, GE Türkelli and R Hammonds, “New Human Rights Duty-Bearers: Towards a Re-conceptualisation of the Human Rights Duty-Bearer Dimension” in Anja Mihr and Mark Gibney (eds), The SAGE Handbook of Human Rights (Sage, forthcoming).

3 They are nonetheless considered to be the most sophisticated way of linking human rights to development. The other categories are implicit human rights work; human rights projects; human rights dialogue; and human rights mainstreaming. See L-H Piron with T O'Neil, “Integrating Human Rights into Development. A synthesis of donor approaches and experiences” (2005), available at storage.globalcitizen.net/data/topic/knowledge/uploads/201209121610859063_%E6%96%B01%20Integrating%20Human%20Rights%20into%20Development.pdf (accessed 22 April 2014).

4 Certainly, successful organisational change will not automatically translate into the envisaged social change.

5 The expression is borrowed from Oestreich. True believers are persons within an organisation, not necessarily within the leadership, who make the case “that pursuing a principled idea … [is] worthwhile from an ethical as well as a practical point of view”. See JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 8

6 The external environment and new issues or approaches, the two other factors that are often mentioned in explaining organisational change, seem more relevant in explaining whether and why an HRBAD was introduced as a matter of policy.

7 See, e.g., J Kirkemann Boesen and T Martin, “Applying a Rights-Based Approach. An Inspirational Guide for Civil Society” (Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2007), available at www.crin.org/docs/dihr_rba.pdf (accessed 22 April 2014).

8 See, e.g., S Hickney and D Mitlin (eds) Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009); P Gready and J Ensor (eds), Reinventing Development? Translating Rights-Based Approaches from Theory to Practice (Zed Books, 2005).

9 OHCHR, Frequently Asked Questions on a Human-Rights Based Approach to Development Cooperation (New York and Geneva, OHCHR, 2006), 15, available at www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FAQen.pdf (accessed 22 April 2014). Compare LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 193–94.

10 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 13 and 15–16. Moreover, in this report, empowerment is not mentioned as a human rights principle, but conceptualised as the goal for HRBAD. Instead, transparency is upgraded from an element of accountability to a separate principle (13–19). Another acronym used, for example, is PANTHER (FAO).

11 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 40.

12 BA Andreassen and G Crawford (eds), Human Rights, Power and Civic Action. Comparative Analyses of Struggles for Rights in Developing Societies (Routledge, 2013).

13 BA Andreassen and G Crawford (eds), Human Rights, Power and Civic Action. Comparative Analyses of Struggles for Rights in Developing Societies (Routledge, 2013).

14 P Gready with W Vandenhole “What are we Trying to Change? Theories of Change in Development and Human Rights”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (Routledge, 2014), 3. For another account of the two, often contrasting, approaches to development, see LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 182–93.

15 LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 3–5.

16 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 43.

17 P Gready with W Vandenhole “What are we Trying to Change? Theories of Change in Development and Human Rights”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (Routledge, 2014), 5–6.

18 P Gready with W Vandenhole “What are we Trying to Change? Theories of Change in Development and Human Rights”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (Routledge, 2014), 6–7.

19 See e.g. JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 54–55, who reports on the paradigm shift for UNICEF in working on legal reform

20 P Gready with W Vandenhole “What are we Trying to Change? Theories of Change in Development and Human Rights”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (Routledge, 2014), 7–8.

21 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 58.

22 P Gready with W Vandenhole “What are we Trying to Change? Theories of Change in Development and Human Rights”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (Routledge, 2014), 8–9.

23 P Gready with W Vandenhole “What are we Trying to Change? Theories of Change in Development and Human Rights”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (Routledge, 2014), 12–15.

24 P Gready with W Vandenhole “What are we Trying to Change? Theories of Change in Development and Human Rights”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (Routledge, 2014), 14.

25 BE Simmons, Mobilizing for Human Rights. International Law in Domestic Politics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009), 8.

26 This is not to say that evidence-based approaches are value-free or neutral.

27 R Eyben, T Kidder, J Rowlands and A Bronstein, “Thinking about Change for Development Practice: a Case Study from Oxfam GB”, (2008) 18/2 Development in Practice, 201–212, 210.

28 WG O'Neill, “The Current Status of Human Rights Mainstreaming Review of Selected CCA/UNDAFs and RC Annual Reports” (2003), available at www.undg.org/archive_docs/3070-Human_rights_review_of_selected_CCA_UNDAF_and_RC_reports.doc (accessed on 22 April 2014), 6.

29 Compare M Darrow and L Arbour, “The Pillar of Glass: Human Rights in the Development Operations of the United Nations” (2009) 103 AJIL 446–501, 457.

30 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), iv and 47–48.

31 A Tostensen and others, “Supporting Child Rights. Synthesis of Lessons Learned in Four Countries” (2011), available at www.cmi.no/publications/file/3947-supporting-child-rights.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 103; compare LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 200.

32 LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 198.

33 For a proposal to rather focus on their interaction, through the concept of structuration, see WR Scott, Institutions and Organizations. Ideas and Interests (Sage Publications, 2008), 48 and 76–79.

34 JW Meyer and B Rowan, “Institutionalized Organisations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony” (1977) 83/2 Am J of Soc, 340–363, 341–42.

35 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 31–32.

36 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 33.

37 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 6–10.

38 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 33.

39 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 42.

40 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 43.

41 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 44. There seem to be similarities between the notion of adaptation and the language of layers and organisational archaeologies used by Gready in his analysis of ActionAid's introduction of HRBA, see below

42 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 45.

43 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 47.

44 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 50.

45 E Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 46, compare 48.

46 LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 200.

47 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 48; compare LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 200, who argues that the organisational structure, i.e. the fact that the Medium-Term Strategic Plan was developed at headquarters, but that the country offices were supervised by the Regional Directors, was one of the reasons why the MTSP did not “stick in any meaningful way”

48 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 50.

49 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 48.

50 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 49.

51 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 49.

52 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 50 et seq. For a more sceptical account, LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 197–200.

53 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 58–59.

54 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 60.

55 LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 201.

56 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 39 et seq.

57 For a succinct introduction to the notion of equity in UNICEF's work, see UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 4–5.

58 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 46–47.

59 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 110–36.

60 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 60–72.

61 UNICEF, “Global Evaluation of the Application of the Human Rights-Based Approach to UNICEF Programming. Final Report – Volume I” (UNICEF, 2012), available at www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/UNICEF_HRBAP_Final_Report_Vol_I_11June_copy-edited_translated.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 72–81.

62 LT Munro, “The ‘Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming’: A Contradiction in Terms?”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 198–200.

63 UNDG unites the 32 UN funds, programmes, offices and specialised agencies that play a role in development, such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO), the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and many others.

64 In addition, there is disagreement whether UNCTs have managed to understand and apply an HRBA. While O'Neill believes that “core human rights concepts have percolated into the CCA/UNDAF process” (WG O'Neill, “The Current Status of Human Rights Mainstreaming Review of Selected CCA/UNDAFs and RC Annual Reports” (2003), available at www.undg.org/archive_docs/3070-Human_rights_review_of_selected_CCA_UNDAF_and_RC_reports.doc (accessed on 22 April 2014), 1), Haugen is more in doubt (HM Haugen, “UN Development Framework and Human Rights: Lip Service or Improved Accountability” (2014) Forum for Development Studies, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2014.901244 (accessed 23 April 2014).

65 “Third Interagency Meeting on Implementing a Human Rights-Based Approach 1–3 October 2008, Tarrytown, New York, Overview of a Human Rights Based Approach in Selected 2007/2008 Common Country Assessment/UN Development Assistance Frameworks”, available at www.undg.org/docs/9405/HRBA_in_CCA-UNDAF-26Sept[1].doc, 22 April 2014, 6; “Report Second Interagency Workshop on Implementing a Human Rights-based Approach in the Context of UN Reform, Stamford, USA, 5–7 May, 2003”, www.undg.org/archive_docs/2568-2nd_Workshop_on_Human_Rights__Final_Report_-_Main_report.doc (accessed 22 April 2014), 10; WG O'Neill, “The Current Status of Human Rights Mainstreaming Review of Selected CCA/UNDAFs and RC Annual Reports” (2003), available at www.undg.org/archive_docs/3070-Human_rights_review_of_selected_CCA_UNDAF_and_RC_reports.doc (accessed on 22 April 2014), 5; “Report of the UN Inter-Agency Workshop on Implementing a Human Rights-based Approach in the Context of UN Reform, January 24-26, 2001, Princeton”, 6.

66 “Report Second Interagency Workshop on Implementing a Human Rights-based Approach in the Context of UN Reform, Stamford, USA, 5–7 May, 2003”, www.undg.org/archive_docs/2568-2nd_Workshop_on_Human_Rights__Final_Report_-_Main_report.doc (accessed 22 April 2014), 2 and 9–10.

67 “Report Second Interagency Workshop on Implementing a Human Rights-based Approach in the Context of UN Reform, Stamford, USA, 5–7 May, 2003”, www.undg.org/archive_docs/2568-2nd_Workshop_on_Human_Rights_Final_Report_-_Main_report.doc (accessed 22 April 2014), 11; “Report of the UN Inter-Agency Workshop on Implementing a Human Rights-based Approach in the Context of UN Reform, 24–26 January 2001, Princeton” 6.

68 “Third Interagency Meeting on Implementing a Human Rights-Based Approach 1–3 October 2008, Tarrytown, New York, Overview of a Human Rights Based Approach in Selected 2007/2008 Common Country Assessment/UN Development Assistance Frameworks”, available at www.undg.org/docs/9405/HRBA_in_CCA-UNDAF-26Sept[1].doc, 22 April 2014, 6–8; HM Haugen, “UN Development Framework and Human Rights: Lip Service or Improved Accountability” (2014) Forum for Development Studies, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2014.901244 (accessed 23 April 2014), 20.

69 “Third Interagency Meeting on Implementing a Human Rights-Based Approach 1–3 October 2008, Tarrytown, New York, Overview of a Human Rights Based Approach in Selected 2007/2008 Common Country Assessment/UN Development Assistance Frameworks”, available at www.undg.org/docs/9405/HRBA_in_CCA-UNDAF-26Sept[1].doc, 22 April 2014, 8.

70 WG O'Neill, “The Current Status of Human Rights Mainstreaming Review of Selected CCA/UNDAFs and RC Annual Reports” (2003), available at www.undg.org/archive_docs/3070-Human_rights_review_of_selected_CCA_UNDAF_and_RC_reports.doc (accessed on 22 April 2014), 7.

71 UNDP, Human Rights for Development news brief, vol. 1, available at www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/democratic-governance/human_rights.html, 2009, 11 (accessed on 15 September 2014).

72 WG O'Neill, “The Current Status of Human Rights Mainstreaming Review of Selected CCA/UNDAFs and RC Annual Reports” (2003), available at www.undg.org/archive_docs/3070-Human_rights_review_of_selected_CCA_UNDAF_and_RC_reports.doc (accessed on 22 April 2014), 15.

73 WG O'Neill, “The Current Status of Human Rights Mainstreaming Review of Selected CCA/UNDAFs and RC Annual Reports” (2003), available at www.undg.org/archive_docs/3070-Human_rights_review_of_selected_CCA_UNDAF_and_RC_reports.doc (accessed on 22 April 2014), 24; for a critique, see M Darrow and L Arbour, “The Pillar of Glass: Human Rights in the Development Operations of the United Nations” (2009) 103 AJIL 446–501, 447–50.

74 “Third Interagency Meeting on Implementing a Human Rights-Based Approach 1–3 October 2008, Tarrytown, New York, Overview of a Human Rights Based Approach in Selected 2007/2008 Common Country Assessment/UN Development Assistance Frameworks”, available at www.undg.org/docs/9405/HRBA_in_CCA-UNDAF-26Sept[1].doc, 22 April 2014, 8; “Report Second Interagency Workshop on Implementing a Human Rights-based Approach in the Context of UN Reform, Stamford, USA, 5–7 May, 2003”, www.undg.org/archive_docs/2568-2nd_Workshop_on_Human_Rights__Final_Report_-_Main_report.doc (accessed 22 April 2014), 9; WG O'Neill, “The Current Status of Human Rights Mainstreaming Review of Selected CCA/UNDAFs and RC Annual Reports” (2003), available at www.undg.org/archive_docs/3070-Human_rights_review_of_selected_CCA_UNDAF_and_RC_reports.doc (accessed on 22 April 2014), 5.

75 “Report Second Interagency Workshop on Implementing a Human Rights-based Approach in the Context of UN Reform, Stamford, USA, 5–7 May, 2003”, www.undg.org/archive_docs/2568-2nd_Workshop_on_Human_Rights__Final_Report_-_Main_report.doc (accessed 22 April 2014), 10.

76 W Vandenhole, “Overcoming the Protection Promotion Dichotomy. Human Rights Based Approaches to Development and Organisational Change within the UN at Country Level” in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (Routledge, 2014), 109–30.

77 Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

78 Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

79 A Tostensen, H Stokke, S Trygged and K Halvorsen, “Supporting Child Rights. Synthesis of Lessons Learned in Four Countries” (2011), available at www.cmi.no/publications/file/3947-supporting-child-rights.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014).

80 A Tostensen, H Stokke, S Trygged and K Halvorsen, “Supporting Child Rights. Synthesis of Lessons Learned in Four Countries” (2011), available at www.cmi.no/publications/file/3947-supporting-child-rights.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 96.

81 A Tostensen, H Stokke, S Trygged and K Halvorsen, “Supporting Child Rights. Synthesis of Lessons Learned in Four Countries” (2011), available at www.cmi.no/publications/file/3947-supporting-child-rights.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 96.

82 A Tostensen, H Stokke, S Trygged and K Halvorsen, “Supporting Child Rights. Synthesis of Lessons Learned in Four Countries” (2011), available at www.cmi.no/publications/file/3947-supporting-child-rights.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 96.

83 A Tostensen, H Stokke, S Trygged and K Halvorsen, “Supporting Child Rights. Synthesis of Lessons Learned in Four Countries” (2011), available at www.cmi.no/publications/file/3947-supporting-child-rights.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 100.

84 A Tostensen, H Stokke, S Trygged and K Halvorsen, “Supporting Child Rights. Synthesis of Lessons Learned in Four Countries” (2011), available at www.cmi.no/publications/file/3947-supporting-child-rights.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 92 and 101.

85 A Tostensen, H Stokke, S Trygged and K Halvorsen, “Supporting Child Rights. Synthesis of Lessons Learned in Four Countries” (2011), available at www.cmi.no/publications/file/3947-supporting-child-rights.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014), 103.

86 D D'Hollander, A Marx and J Wouters, “Integrating Human Rights in Development Policy: Mapping Donor Strategies and Practices”, Working Paper 108, June 2013, available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2286204 (accessed 18 April 2014), 48–49.

87 Some empirical work has also been undertaken with regard to Plan's HRBAD in the field, see K Arts, “Countering Violence against Children in the Philippines: Positive RBA Practice Examples from Plan”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (Routledge, 2014) 149–76.

88 J Chapman, in collaboration with V Miller, A Campolina Soares and J Samuel, “Rights-Based Development: The Challenge of Change and Power for Development NGOs”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 167.

89 J Chapman, in collaboration with V Miller, A Campolina Soares and J Samuel, “Rights-Based Development: The Challenge of Change and Power for Development NGOs”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 169 and 174.

90 J Chapman in collaboration with V Miller, A Campolina Soares and J Samuel, “Rights-Based Development: The Challenge of Change and Power for Development NGOs”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 170 and 175.

91 J Chapman in collaboration with V Miller, A Campolina Soares and J Samuel, “Rights-Based Development: The Challenge of Change and Power for Development NGOs”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 177.

92 P Gready, “ActionAid's Human Rights-Based Approach and its Impact on Organisational and Operational Change”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (2014, Routledge), 177, 180.

93 P Gready, “ActionAid's Human Rights-Based Approach and its Impact on Organisational and Operational Change”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (2014, Routledge), 181.

94 P Gready, “ActionAid's Human Rights-Based Approach and its Impact on Organisational and Operational Change”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (2014, Routledge), 181.

95 P Gready, “ActionAid's Human Rights-Based Approach and its Impact on Organisational and Operational Change”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (2014, Routledge), 183–86 and 188.

96 P Gready, “ActionAid's Human Rights-Based Approach and its Impact on Organisational and Operational Change”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (2014, Routledge), 182 and 187, citing L David Brown and others, “ActionAid International Taking Stock Review 3. Synthesis Report” (2010) www.actionaid.org/sites/files/actionaid/tsr3_synthesis_report_final.pdf (accessed 23 April 2014).

97 J Chapman in collaboration with V Miller, A Campolina Soares and J Samuel, “Rights-Based Development: The Challenge of Change and Power for Development NGOs”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 165, 179.

98 J Chapman in collaboration with V Miller, A Campolina Soares and J Samuel, “Rights-Based Development: The Challenge of Change and Power for Development NGOs”, in Sam Hickey and Diana Mitlin (eds), Rights-Based Approaches to Development. Exploring the Potential and Pitfalls (Kumarian Press, 2009), 181.

99 P Gready, “ActionAid's Human Rights-Based Approach and its Impact on Organisational and Operational Change”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (2014, Routledge), 177, 179.

100 P Gready, “ActionAid's Human Rights-Based Approach and its Impact on Organisational and Operational Change”, in Paul Gready and Wouter Vandenhole (eds), Human Rights and Development in the New Millennium. Towards a Theory of Change (2014, Routledge), 189.

101 JE Oestreich, Power and Principle. Human Rights Programming in International Organizations (Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, 2007), 56–57.