Abstract

The present study examined a parachute training course intended to improve the leadership abilities of future military officers. Two research questions were examined. First, whether there were any differences between completers and non-completers in anxiety, stress, and collective identity at the beginning of the course (time 1), and second, whether there were any differences between completers and non-completers in leadership self-efficacy immediately after the course and at a five-month follow-up (time 2 and time 3). Participants were cadets from the Swedish Military Academy undergoing the course as part of their officer training curriculum. The results showed no significant differences between completers and non-completers in anxiety, stress, and collective identity at the beginning of the course (time 1). Non-completers showed a significant reduction in leader self-control efficacy compared to those who completed the training immediately after the course and at a five-month follow-up (time 2 and 3). Overall, these results indicate that non-completion of this type of demanding training could have negative effects on the individual’s leader self-control efficacy.

Keywords:

Falling short of our goals is something that happens to all of us. Whether it is in sports, in education, or in our profession we will sometimes not be able to achieve our objectives. When this happens, individuals will have to deal both with an undesired and often unexpected result as well as the individuals’ perceptions of their own abilities. Although the inability to complete something can happen in all aspects of life, doing so in a military setting can be more serious due to the fact that military training is often both physically and psychologically demanding and that failure in a real combat situation can lead to severe injury or even death for oneself or one’s subordinates (Kolditz, Citation2007).

One of the more challenging aspects of training future military leaders for extreme situations is to simulate the inherent dangers and strains of actual combat. For both ethical and practical reasons, it is impossible to expose individuals to actual combat to prepare them for that situation. Therefore, the military instead utilises training courses that create as extreme an environment as possible within ethical limits (Meichenbaum, Citation2007). The idea behind such training is to expose individuals to a high but manageable level of stress, which in turn will make them better prepared for similar future situations (Maddi, Citation2002, Citation2006, Citation2007).

One of the more common ways of preparing future military leaders for leadership in extreme contexts is parachute training (Kolditz, Citation2007). Since its introduction in the military around the time of the Second World War, parachute training has been implicitly linked to leadership abilities (Basowitz, Persky, Korchin, & Grinker, Citation1955; Gavin, Citation1947; Ursin, Baade, & Levine, Citation1978). Parachuting has been considered a good training substitute for leading in combat because the individual reactions in parachuting are similar to those in combat (McMillan & Rachman, Citation1988). In performing a parachute jump the individual must cope with an extreme situation, but must also act and perform certain actions (doing nothing is not enough) in order to successfully master that situation (Breivik, Roth, & Jørgensen, Citation1998). Thus, parachuting can be suitable for preparing future leaders for leadership in combat where self-control to maintain composure, and assertiveness to make active, split-second decisions when leading others are vital (Samuels, Foster, & Lindsay, Citation2010).

However, parachuting presents a challenging situation and not all individuals will be able to complete a course and actually perform a parachute jump. Therefore, the first aim of the present study was to investigate whether there were any differences between military cadets that completed parachute training and those who could not. Second, because parachute training is one (of many) important parts of the military leadership training, it is inherently important to understand what happens when cadets do not complete it. Thus, the second aim of the present study was to investigate if non-completion is associated with any direct and sustained negative effects on leadership self-efficacy.

Completing parachute training

Taking a parachute training course is demanding, and completing it by actually jumping out of a plane is by no means a given outcome. Although the possession of certain individual qualities can have a predictive validity on successful performance, they are not necessarily a guarantee of success in demanding military training (Bartone, Roland, Picano, & Williams, Citation2008; Hartmann, Sunde, Kristensen, & Martinussen, Citation2003).

On an individual level, the ability to handle anxiety and stress is central to handling a parachute training situation. Stress can impede the development of coping strategies necessary to become a skilful master of the situation, and individuals with excessively high levels of stress tend to want to leave the training situation (Fenz & Jones, Citation1974). Similarly, anxiety increases prior to performing a parachute jump (Endler, Crooks, & Parker, Citation1992; Fenz & Jones, Citation1972) and could reduce performance by redirecting the individual’s focus from the task to the perceived threat (Dorenkamp & Vik, Citation2018; Eysenck, Derakshan, Santos, & Calvo, Citation2007). Although studies on the subject have been inconclusive and have failed to find any significant associations between either anxiety and training performance (Gal-Or, Tenenbaum, Furst, & Shertzer, Citation1985) or between anxiety and jump performance (Idzikowski & Baddeley, Citation1987), they are consistent in that levels of anxiety have been shown to increase prior to performing a parachute jump (Hare, Wetherell, & Smith, Citation2013).

On an organisational level, better social support and unit cohesion can increase performance, especially in military settings (Britt & Oliver, Citation2013; King, Citation2013; Stewart, Citation1991). Experienced cohesion within the military reduces avoidant coping in dangerous situations, meaning that the tighter the group is, the more likely individuals are to help each other face difficult challenges instead of avoiding them (McAndrew et al., Citation2017). At the intersection between the individual and organisational level, the individual’s desired identity and preferred self-conceptions have been found to affect whether future parachutists were willing to commit to the discipline and endurance required to endure parachute training (Thornborrow & Brown, Citation2009). In effect, individuals’ level of identification with the organisation could affect performance in parachute training.

Effects of not completing parachute training

Successful training has been shown to increase coping skills, defined as a positive response outcome expectancy (Ursin & Eriksen, Citation2004, Citation2010). This means that the individual has established that he or she will be able to master a stressful situation with a positive outcome, which in turn will reduce stress (Ursin & Eriksen, Citation2010). Coping, in turn, can affect self-efficacy perceptions, which are the individuals’ beliefs in their own abilities and what they can do with those abilities (Bandura, Citation1986, Citation1997). Self-efficacy has also been argued to be a context-specific construct, meaning that for example the belief in one’s ability to drive a car in rush hour traffic does not necessarily mean a similarly high belief in the ability to speak publicly in front of a large audience (Bandura, Citation1997). The specific effects of parachuting on leadership have been discussed in terms of self-efficacy transfer between domains. Successfully mastering of parachute jumping can increase the individual’s belief that tasks like leadership in combat can be overcome the same way (Samuels et al., Citation2010). Samuels et al. (Citation2010) showed that increased self-efficacy from completing a parachute training course can transfer especially into leadership self-efficacy, the individual’s efficacy associated with the level of confidence in the knowledge, skills, and abilities associated with leading others (Hannah, Avolio, Luthans, & Harms, Citation2008). Specifically, parachuting has been shown to affect the domains of leader self-control (to maintain cognitive and emotional control) and leader assertiveness (the ability to make immediate and technically correct decisions in leading others) (Bergman, Gustafsson-Sendén & Berntson, Citation2019; Samuels et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, in the framework of developmental leadership, an extension of transformational leadership, it is suggested that coping with stress is an important characteristic that leaders should possess in order to become transformational (or developing) leaders (Larsson, Citation2006; Larsson et al., Citation2003).

Leadership self-efficacy is not a specific form of leadership like transformational leadership (Bass & Riggio, Citation2006) or developmental leadership (Larsson, Citation2006) but has been argued to affect leadership in several ways. McCormick (Citation2001) argued that self-efficacy beliefs affect the dynamic between leader and follower by two mechanisms. First by individual motivation and the direction, effort and persistence required for a transformational leader. Second, the individual’s selection of strategies to carry out their leadership for specific situations, which subsequently then determine how the individual’s leadership behaviours affect the environment (McCormick, Citation2001; Wood & Bandura, 1989). Self-efficacy has also been shown to be related to increasing leadership performance as evaluated by both objective observers as well as ratings from peers and subordinates (Chemers, Watson, & May, Citation2000; Gilson, Dix, & Lochbaum, Citation2017). Successful performance then reinforces self-efficacy beliefs and the cycle begins again (McCormick, Citation2001).

However, if an individual cannot cope with the stressful situation of parachute jumping, it can lead to negative response outcome expectancies. Ursin and Eriksen (Citation2004, Citation2010) argue that the negative outcome of not coping with stressful situations may result in a state of hopelessness with increased levels of stress, meaning that the individual will anticipate that required actions taken in a stressful situation will not help (Ursin & Eriksen, Citation2010). Because the self-efficacy transfer is central to the positive effects of parachuting and relies on individual coping it is possible that the hopelessness associated with non-completion in the same training course can lead not only to the absence of the positive effects previously studied (Samuels et al., Citation2010), but also to negative direct and sustained effects. Put more simply, succeeding in parachute training can increase your belief in your own abilities in other situations, but not succeeding could possibly decrease them in the same way. Kolditz (Citation2007) argued that a leader who appears confident sends a tacit message to subordinates that they should rely on the leader’s competence because the leader knows it exists. In the reverse situation, it is possible that a leader lacking the same may send a tacit message to subordinates by displaying a lack of confidence in his own abilities. Parachute training has been part of the officer training curriculum for more than 60 years, heavily influencing the view of leadership within the military. For example, the “follow me” practice (Gavin, Citation1947; Nordyke, Citation2005) where the officer leads by example and inspires subordinates by being the first person to jump out of the aircraft door is highly similar to the inspirational/motivation component presented as vital to transformational leadership by Bass and Riggio (Citation2006). Such organisational beliefs could both help individuals to lead by example but also create a disbelief in their ability if they were unable to complete key training preparing them to do just that.

So far, previous research on military parachute training has focused on the positive effects of successfully coping with such a stressful situation (e.g., Basowitz et al., Citation1955; Sharma et al., Citation1994; Ursin et al., Citation1978). No known studies have addressed the possible negative effects of not completing the same training.

To sum up, the present study addresses two research questions. First, whether there were differences between completers and non-completers in anxiety, stress, and collective identity at the beginning (time 1) of the military parachute training course. Second, if non-completion was associated with any direct and sustained negative effects in leadership self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1997). Specifically, whether there were any differences between completers and non-completers in the sub-domains of leader self-control efficacy (the ability to retain composure) and leader assertiveness efficacy (the ability to make decisions in leading others) immediately after the course and at a five-month follow-up (time 2 and time 3).

Method

The study with its procedures and measures received ethical approval from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Reference number 2014/582-32/5 and 2015/1032-32). Participants were informed of the parameters, procedure and voluntariness of the study and gave their informed consent. No compensation was offered for participation.

Participants and procedure

The participants were 199 cadets from the Swedish Military Academy attending a Basic Airborne Course to learn static-line parachuting (Women = 9.6%, men = 90.4%, Mage = 25.0 years at the time each respondent started the course, SDage = 3.2). Data collection was accomplished in three different courses over three years (n1 = 63, n2 = 71 & n3 = 65). The training curriculum was identical in all three courses, conducted at the same time of the year, and at the same time in the leadership training programme for all participants.

This type of research does not allow for random assignment of participants to equal sized groups. Because non-completion is an undesired state for both the organisation and the individual, random assignment of participants to different groups was not possible. Therefore, the participants who did not complete the course (n = 18) were grouped together and compared to those who completed the course (n = 181). Demographic variables for the completers and non-completers group can be seen in .

Table 1 Demographic of the groups of completers and non-completers in regard to age, sex, years of prior service before admission to the military academy, prior knowledge of the parachuting course prior to admission to the military academy and prior international service (i.e., Kosovo, Afghanistan, Mali, Iraq).

The categorisation of non-completers was based on the following procedures. Over the three years, 13 participants were removed due to their inability to meet the required standards and complete the safety tests. These tests were either: 1) a theoretical written test, 2) a jump-tower simulation of a stable exit from an aircraft, or 3) a landing-swing simulation of a parachute landing fall. Individuals who could not successfully complete any test were given supplementary instructions and a retry. Participants who failed a second time were removed from the course. Furthermore, five participants were removed for medical reasons. The course director conducted physical health checks on all participants upon commencement and continuously during the course and referred injuries (antecedent or that occurred during training) considered severe enough to the regimental physician, who performed a more thorough medical examination. Individuals with injuries considered incompatible with the strains of performing a parachute jump were removed from training. The safety tests were conducted during the second week and all participants who failed these stayed until the course was finished. In four cases (all medical) the participants opted to leave early during day three of the first week. These conducted the questionnaires before leaving the training site.

Because data collection was accomplished in a time interval of three years a few independent variables were added during the course of the study. Independent variables were measured at time 1, dependent measures at times 1, 2 and 3. The time 1-measurement was conducted before commencement of the course (time 1, response rate = 100%). Time 2-measurement was conducted after completion of the course on the last day. If individuals who had failed chose to leave the training site, they were asked to complete the questionnaire before leaving (time 2, response rate = 99%). The time 3-measurement was performed five months later at the Military Academy (time 3, response rate = 96%).

Measures

Trait Anxiety was measured using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory – State scale (STAI-T; Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, Citation1970). The scale includes 20 items, for example “I feel tense” or “I feel calm”, assessed on a four-point response scale (1 = almost never; 4 = almost always). Cronbach’s alpha = .83. Trait anxiety was measured in the second and third years.

Stress was measured with the Stress/Energy-form (Kjellberg & Iwanowski, Citation1989). The scale includes six adjectives to answer the question “How have you felt at work for the last week?”, for example “Tense” or “Relaxed”, thereby describing the person’s state at that specific time. The adjectives were rated on a 6-point response scale (1 = not at all, 6 = very much). Cronbach’s alpha = .80. Stress was measured in the second and third years.

Collective identity was measured using the Collective Self-Esteem Scale, sub-scale Importance to identity (Crocker & Luhtanen, Citation1990) that assesses the importance of one’s social group memberships to one’s self-concept. The scale includes four items, for example “My belonging in the Swedish Armed Forces is an important reflection of who I am”, rated using a seven-point response scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha = .72. Collective identity was included in the third year.

Leadership Self-Efficacy was measured using a short version of the Leadership Self-Efficacy Scale with the subscales of Self-Control Efficacy and Assertiveness Efficacy (Bergman et al., Citation2019; Samuels et al., Citation2010). Both scales included six items, for example “I can easily shift attention away from thoughts that scare me” (self-control) or “I can easily lead others, maintain the same high standards, and not be seen as hypocritical” (assertiveness). The responses were assessed on a seven-point response scale (1 = do not agree, 7 = do fully agree). Cronbach’s alpha = .71 for Self-Control Efficacy and .61 for Assertiveness Efficacy. Leadership Self-Efficacy was collected in all years.

Results

Because participants were not randomly assigned to the course, we compared the completers and the non-completers at time 1 on gender composition (chi-square) and age (t-test), as well as self-efficacy at time 1 (t-test) to check for any pre-existing group differences. There were no differences between the groups in gender composition, χ2 (1, N = 199) = 0.28, p = ns, or age t (132) = 1.29, p = ns. There were neither any group differences at time 1 between the completers and the non-completers mean values for leader self-control efficacy t (197) = −.98, p = ns, or for leader assertiveness efficacy t (197) = .55, p = ns.

Additionally, because the parachuting courses started in three different years, we also compared the mean values at time 1 for these three different groups, by computing two one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA). The results indicated no significant difference between training year collected for leader self-control (Myear 1 = 5.14, SD = .88; Myear 2 = 5.40, SD = .84; Myear 3 = 5.49, SD = .73), F (2, 196) = 1.83, p = ns, or leader assertiveness efficacy (Myear 1 = 5.36, SD = .70; Myear 3 = 5.37, SD = .72, Myear 3 = 5.46, SD = .67), F (2, 296) = 1.37, p = ns.

Differences between completers and non-completers

To test whether completers differed from non-completers at the beginning of the course, we computed three independent sample t-tests of anxiety, stress, and collective identity. Descriptive means, standard deviations and p-values are found in . There were no significant differences in any variables between those who completed the course and those who did not.

Table 2 Differences between completers and non-completers in anxiety, stress, and collective identity at time 1.

Additional power-calculations were performed because of the different scales used and the uneven distribution between the groups. Using the mean values, sample size and the pooled standard deviation for each respective scale we performed a power/sample size calculation, estimating how many participants would have been required in each respective group in order to reach a significant result at p < .05 and effect size of .50 (Cohen, Citation1988). The results were N = 65 for anxiety, N = 282 for stress and N = 24 for identity.

Effects of non-completion

To investigate the direct and sustained effects of completion or non-completion on leadership self-efficacy, two mixed 2 (groups) × 3 (time) repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) were computed. Groups (completers/non-completers) were the between groups factor and time (time 1, 2 and 3) the within groups factor. Leader self-control efficacy and leader assertiveness efficacy were the dependent variables for each ANOVA.

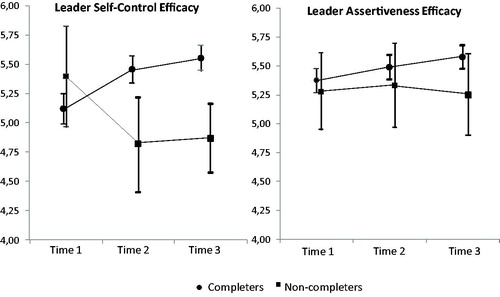

For leader self-control efficacy, there was no main effect of time, F (2, 187) = .772, p = ns, but a main effect of group, F (1, 188) = 4.427, p < .05, ŋ2p = .023. This main effect was qualified by a significant interaction effect for Time × Group, F (2, 187) = 14.458, p < .001, ŋ2p = .54. Post hoc analyses confirmed the significance of the intervention in that the scores for the completers group were significantly higher than for the non-completers group for time 2 (p < .05) and at time 3 (p < .001). Mean values and 95% confidence intervals are displayed in . The non-completers had a higher score (although not significantly) than the completers before the course, but self-control efficacy scores increased for the completers and decreased for non-completers.

Figure 1 Differences between completers and non-completers leader self-control efficacy and leader assertiveness efficacy immediately after the course (time 2) and at a five-month follow-up (time 3).

An individual-oriented approach with descriptive statistics was also used to further examine the significant differences of the non-completers in leader self-control efficacy. Within the non-completing group, 15 of 18 individuals showed lower self-control efficacy after the course (time 2) compared to the beginning (time 1), while 3 of 18 reported an increase over the same period. Five months later (time 3), 13 of 18 still showed a lower self-control efficacy than at the beginning of the course (time 1). At time 2, 6 out of the 18 non-completers, rated themselves within the 95% CI of participants who completed the course. At time 3, only one participant of the 16 non-completers did the same.

For leader assertiveness efficacy, there was no main effect of time, F (2, 187) = 1.92, p = ns, or group, F (1, 188) = 1.68, p = ns, nor any interaction effect, F (2,187) = 1.05, p = ns. Because of the absence of effects, no post hoc analyses were conducted. We performed an additional power/sample size calculation, estimating how many participants would have been required in each respective group in order to reach a significant result at p < .05 and effect size of .50. The result was N = 72.

Discussion

The present study investigated firstly, whether there were differences between completers and non-completers in anxiety, stress, and collective identity at the beginning (time 1) of the military parachute training course. Secondly, if non-completion was associated with any direct and sustained negative effects in leadership self-efficacy, specifically in the sub-domains of leader self-control efficacy and leader assertiveness efficacy immediately after the course and at the five-month follow-up (time 2 and time 3).

Regarding the first research question about differences between completers and non-completers at the beginning of the course, we found no significant differences in state anxiety, perceived stress or collective identity. Granted, the differences in mean values as well as the limited sample, specifically for collective identity, indicated that there could be differences, although not enough to represent a significant result. These results could have several explanations, including both methodological and group composition factors. First, the selection process for officer training places all participants above average in both psychological and physiological characteristics (Swedish Defence University, Citation2016), possibly making the restricted range too narrow to detect within-group differences. Second, a social desirability bias could possibly influence individuals in the non-completion group to deny traits such as stress and anxiety that are socially undesirable in that context (Heck, Hoffmann, & Moshagen, Citation2018; Poltavski, Eck, Winger, & Honts, Citation2018). On the other hand, the measurement included in the analysis was made before the start of the training course, implying that the differences between the groups should be low or non-existent.

Although increased levels of stress and anxiety could reduce the chances of successful completion of a parachute jump, the completers actually rated themselves higher (although not significantly) on both stress and anxiety scales than the non-completers. A possible explanation is that both stress and anxiety are natural in the context of parachute jumping and to some extent required for positive attention control and performance (Eysenck et al., Citation2007). Another explanation could be that non-completers did not anticipate completing the course. If this is the case, it could be argued that they did not experience as much stress and anxiety before a parachute jump they did not anticipate making. Similar results with slightly lower levels of anxiety for those who dropped out of training were also reported by Basowitz et al. (Citation1955).

Regarding our second research question and the consequences on leadership self-efficacy of not completing the parachute training course, there was an interaction between time and group for leader self-control efficacy, implying that non-completion of the parachute training course had a significant negative effect. The non-overlapping confidence intervals indicated that the non-completion group decreased in self-control efficacy between times 1 and 2, and that the level was sustained in the follow-up measurement of time 3.

In leader assertiveness efficacy the non-completers rated themselves lower than the completers at all measurement times. This indicated the absence of positive effects more than any sustained negative effects. The differences between completers and non-completers were not large enough to be significant. The Cronbach’s alpha for leader assertiveness efficacy with the present sample was also low (.61) which could have contributed to a non-significant result (DeVellis, Citation2012).

Overall, these results indicate that non-completion of the training course can not only lead to the absence of the desired positive effects but can have sustained negative effects on leader self-control efficacy. Hence, the non-completion of parachute training can decrease the individual’s belief that he or she can retain composure in other tasks such as leading in combat. However, self-efficacy is a multifaceted phenomenon that is also dependent on task demands within a given activity and under different circumstances, limiting the possibility of generalisation (Bandura, Citation1997). It is also reasonable to assume that self-efficacy will change over longer periods of time than were included in the present study, especially in the environment of the Military Academy where an emphasis is placed on personal development.

There are a few limitations in the present study that need to be addressed. The first is the small sample size of the non-completion group and their uneven distribution when compared to the completers. However, this limitation is a factual one and not determined by design. Because non-completion is an unwanted state for the participants it would be impossible to raise the number of respondents by design. Although we were able to attain a high response rate of 96% over three measurement times and the groups were large enough to detect the interaction effect in leader self-control efficacy, the results should be interpreted with some caution.

The non-completion group was diverse and consisted of individuals dismissed for medical reasons (n = 5) or the inability to meet the prescribed standards (n = 13). Previous research has shown that it is difficult to differentiate between the two because the training situation is both physically and psychologically demanding (Ursin et al., Citation1978). In fact, Ursin et al. (Citation1978) points out that discharge for medical reasons (being out of the individual’s control) is a more socially acceptable cause for dismissal than the inability to meet the required standards (being entirely under the individual’s control). In military cultures that put a premium on success and winning, inability to perform according to prescribed standards has sometimes been regarded with contempt, even in peacetime training (Soeters & Boer, Citation2000). This might lead individuals to deny shortcomings because of shame and fear of missing opportunities or loss of social status (Flam, Citation1993). In effect, medical dismissals could be desired, at least to some degree, to allow participants the opportunity to save face with their peers.

From a wider perspective, the restricted range and limited sample size are generic to this type of research and a real-life training situation. For example, it would be highly unethical to withhold training from individuals whose life might depend on that training just to attain randomisation or equally sized groups. On the contrary, the strength of this type of research is that the research questions and applications relate directly to a real, life-and-death activity. Statistically, limited sample sizes often result in problems such as low statistical power or low reproducibility. When means are evaluated in unevenly distributed groups, confidence intervals as chosen in the present study are more informative and may reduce the risk of misinterpretation (Cumming, Citation2012; Wiens & Nilsson, Citation2017).

Military cadets who participate in this type of training but cannot for some reason complete it represent an investment in both time and money, and will probably continue their military career, regardless of the outcome of a specific course. Recommendations for further studies are therefore to more closely examine the negative consequences associated with non-completion and to consider what can be done to prevent or mitigate the negative effects.

This study examined a parachute training course and its effects on leadership self-efficacy. The main finding was that non-completion resulted in a more significant reduction in leader self-control efficacy compared to completion. This indicates that failing in this type of training designed to teach individuals to lead in combat, might not only lead to the absence of the positive effects intended, but the presence of negative effects as well.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought & action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman & Co.

- Bartone, P. T., Roland, R. R., Picano, J. J., & Williams, T. J. (2008). Psychological hardiness predicts success in US Army Special Forces candidates. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 16(1), 78–81. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2389.2008.00412.x

- Basowitz, H., Persky, H., Korchin, S. J., & Grinker, R. R. (1955). Anxiety and stress. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Bass, B., & Riggio, R. (2006). Transformational leadership. (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bergman, D., Gustafsson-Sendén, M., & Berntson, E. (2019). Preparing to lead in combat: Development of leadership self-efficacy by static-line parachuting. Military Psychology. doi:10.1080/08995605.2019.1670583.

- Breivik, G., Roth, W. T., & Jørgensen, P. E. (1998). Personality, psychological states and heart rate in novice and expert parachutists. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(2), 365–380. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00058-0

- Britt, T. W., & Oliver, K. K. (2013). Morale and cohesion as contributors to resilience. In R. R. Sinclair, & T. W. Britt (Eds.), Building psychological resilience in military personnel: Theory and practice (pp. 47–65). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Chemers, M., Watson, C., & May, S. (2000). Dispositional affect and leadership effectiveness: A comparison of self-esteem, optimism, and efficacy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(3), 267–277.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Crocker, J., & Luhtanen, R. (1990). Collective self-esteem and ingroup bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(1), 60–67. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.60

- Cumming, G. (2012). Understanding the new statistics: Effect sizes, confidence intervals, and meta-analysis. New York, NY: Routledge.

- DeVellis, R. F. (2012). Scale development: Theory and applications (pp. 109–110). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Dorenkamp, M. A., & Vik, P. (2018). Neuropsychological assessment anxiety: A systematic review. Practice Innovations, 3(3), 192–211. doi:10.1037/pri0000073

- Endler, N. S., Crooks, D. S., & Parker, J. D. (1992). The interaction model of anxiety: An empirical test in a parachute training situation. Anxiety, Stress & Coping. An International Journal, 5(4), 301–311. doi:10.1080/10615809208248367

- Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336–353. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336

- Fenz, W. D., & Jones, G. B. (1972). The effect of uncertainty on mastery of stress: A case study. Psychophysiology, 9(6), 615–619. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1972.tb00771.x

- Fenz, W. D., & Jones, G. B. (1974). Cardiac conditioning in a reaction time task and heart rate control during real life stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 18(3), 199–203. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(74)90022-1

- Flam, H. (1993). Fear, loyalty and greedy organizations. In S. Fineman (Ed.), Emotion in organizations (pp. 58–75). London: Sage.

- Gal-Or, Y., Tenenbaum, G., Furst, D., & Shertzer, M. (1985). Effect of self-control and anxiety on training performance in young and novice parachuters. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 60(3), 743–746. doi:10.2466/pms.1985.60.3.743

- Gavin, J. (1947). Airborne Warfare. Washington: Infantry Journal Press.

- Gilson, T. A., Dix, M. A., & Lochbaum, M. (2016). Drive On”: The relationship between psychological variables and effective squad leadership. Military Psychology, 29(1), 58–67. doi:10.1037/mil0000136.

- Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., & Harms, P. D. (2008). Leadership efficacy: Review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(6), 669–692.

- Hare, O. A., Wetherell, M. A., & Smith, M. A. (2013). State anxiety and cortisol reactivity to skydiving in novice versus experienced skydivers. Physiology & Behavior, 118, 40–44. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.05.011

- Hartmann, E., Sunde, T., Kristensen, W., & Martinussen, M. (2003). Psychological measures as predictors of military training performance. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80(1), 87–98. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_17

- Heck, D. W., Hoffmann, A., & Moshagen, M. (2018). Detecting nonadherence without loss in efficiency: A simple extension of the crosswise model. Behavior Research Methods, 50(5), 1895–1905. doi:10.3758/s13428-017-0957-8

- Idzikowski, C., & Baddeley, A. (1987). Fear and performance in novice parachutists. Ergonomics, 30(10), 1463–1474. doi:10.1080/00140138708966039

- King, A. (2013). The combat soldier - Infantry tactics and cohesion in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kjellberg, A., & Iwanowski, A. (1989). Stress/energi formuläret: Utveckling av en metod för skattning av sinnesstämning i arbetet. Solna: Arbetslivsinstitutet.

- Kolditz, T. A. (2007). In extremis leadership: Leading as if your life depended on it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Larsson, G. (2006). Implementation of developmental leadership in the Swedish armed forces. Military Psychology, 18(sup1), S103–S109. doi:10.1207/s15327876mp1803s_8

- Larsson, G., Carlstedt, L., Andersson, J., Andersson, L., Danielsson, E., Johansson, A., … Michel, P. (2003). A comprehensive system for leader evaluation and development. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 24(1), 16–25.

- Maddi, S. R. (2002). The story of hardiness: Twenty years of theorizing, research, and practice. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 54(3), 173–185. doi:10.1037/1061-4087.54.3.173

- Maddi, S. R. (2006). Hardiness: The courage to grow from stresses. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(3), 160–169. doi:10.1080/17439760600619609

- Maddi, S. R. (2007). Relevance of hardiness assessment and training to the military context. Military Psychology, 19(1), 61–70. doi:10.1080/08995600701323301

- McAndrew, L. M., Markowitz, S., Lu, S.-E., Borders, A., Rothman, D., & Quigley, K. S. (2017). Resilience during war: Better unit cohesion and reductions in avoidant coping are associated with better mental health function after combat deployment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(1), 52–61. doi:10.1037/tra0000152

- Mccormick, M. J. (2001). Self-efficacy and leadership effectiveness: Applying social cognitive theory to leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 8(1), 22–33. doi:10.1177/107179190100800102.

- McMillan, T. M., & Rachman, S. J. (1988). Fearlessness and courage in paratroopers undergoing training. Personality and Individual Differences, 9(2), 373–378. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(88)90100-6

- Meichenbaum, D. (2007). In P. M. Lehrer, R. L. Woolfolk & W. E. Sime (Eds.), Principles and practice of stress management (3rd ed., pp. 497–516, chapter xvii, 734 pages), New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Nordyke, P. (2005). All American, all the way: The combat history of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press.

- Poltavski, D., Eck, R., Winger, A. T., & Honts, C. (2018). Using a polygraph system for evaluation of the social desirability response bias in self-report measures of aggression. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 43(4), 309.

- Samuels, S. M., Foster, C. A., & Lindsay, D. R. (2010). Freefall, self-efficacy, and leading in dangerous contexts. Military Psychology, 22(sup1), S117–S136. doi:10.1080/08995601003644379

- Sharma, V. M., Sridharan, K., Selvamurthy, W., Mukherjee, A. K., Kumaria, M. M. L., Upadhyay, T. N., … Dimri, G. P. (1994). Personality traits and performance of military parachutist trainees. Ergonomics, 37(7), 1145–1155. doi:10.1080/00140139408964894

- Soeters, J. L., & Boer, P. C. (2000). Culture and flight safety in military aviation. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 10(2), 111–133. doi:10.1207/S15327108IJAP1002_1

- Spielberger, C., Gorsuch, R., & Lushene, R. (1970). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologist Press.

- Stewart, N. K. (1991). Mates and muchachos: Unit cohesion in the Falklands-Malvinas war. McLean, Virgina: Brassey's.

- Swedish Defence University. (2016). Beskrivning av lämplighetsbedömning inför antagning till Officersprogrammet (Description of aptitude assessment for selection to the officer training program). Stockholm: Försvarshögskolan.

- Thornborrow, T., & Brown, A. D. (2009). ‘Being regimented’: Aspiration, discipline and identity work in the British parachute regiment. Organization Studies, 30(4), 355–376. doi:10.1177/0170840608101140

- Ursin, H., Baade, E., & Levine, S. (1978). Psychobiology of stress: A study of coping men. New York: Academic Press.

- Ursin, H., & Eriksen, H. R. (2004). The cognitive activation theory of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(5), 567–592. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00091-X

- Ursin, H., & Eriksen, H. R. (2010). Cognitive activation theory of stress (CATS). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(6), 877–881. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.03.001

- Wiens, S., & Nilsson, M. E. (2017). Performing contrast analysis in factorial designs: From NHST to confidence intervals and beyond. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 77(4), 690–715. doi:10.1177/0013164416668950